BIOCHEMISTRY OF THE MUSCLE The muscle is an

BIOCHEMISTRY OF THE MUSCLE • The muscle is an aggregate of proteins involved in contraction. • The musculature is therefore what makes movement possible • Muscle is a major biochemical transducer • Converts potential energy into kinetic energy • Largest single tissue in the human body

CLASSIFICATION OF MUSCLES There are 3 basic types of muscle • Skeletal muscle • Cardiac muscle • Smooth muscle • They are also divided into 2 based on electron microscopic appearance • Striated eg cardiac and skeletal • Non striated eg smooth muscles

Classification continued • Divided based on control from the CNS • Voluntary muscles eg skeletal muscles • Involuntary muscles eg cardiac and smooth muscles

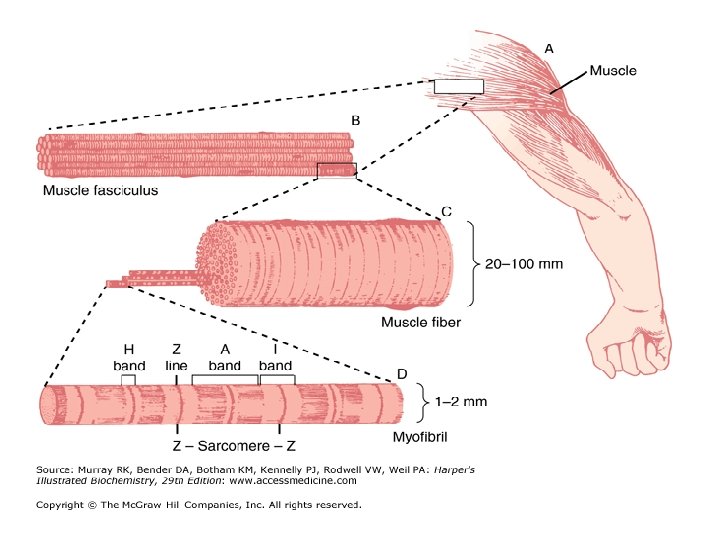

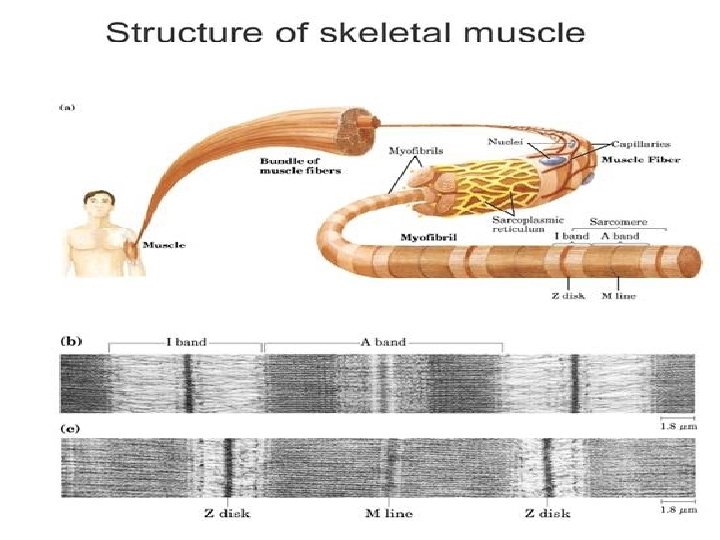

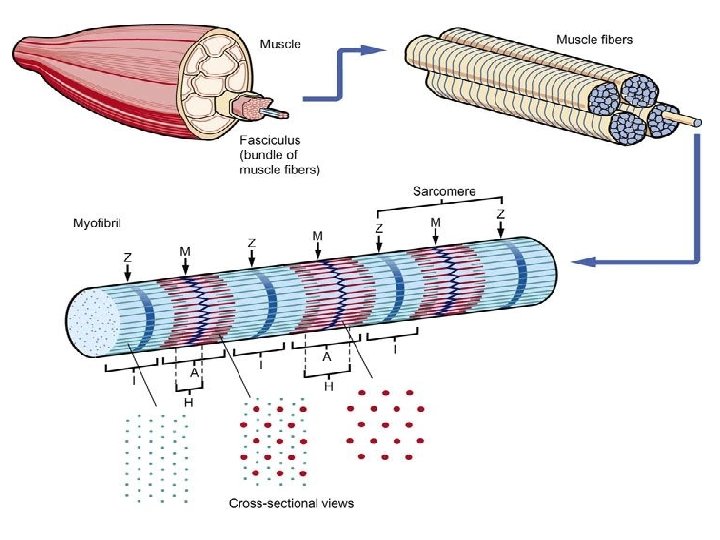

• ORGANISATION OF THE SKELETAL MUSCLE • The skeletal muscle is striated and consists of parallel bundles of muscle fibers connected to tendons at both ends.

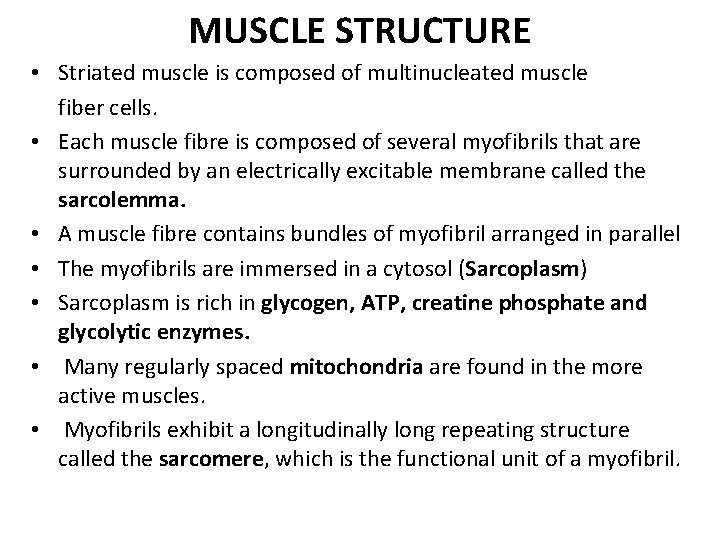

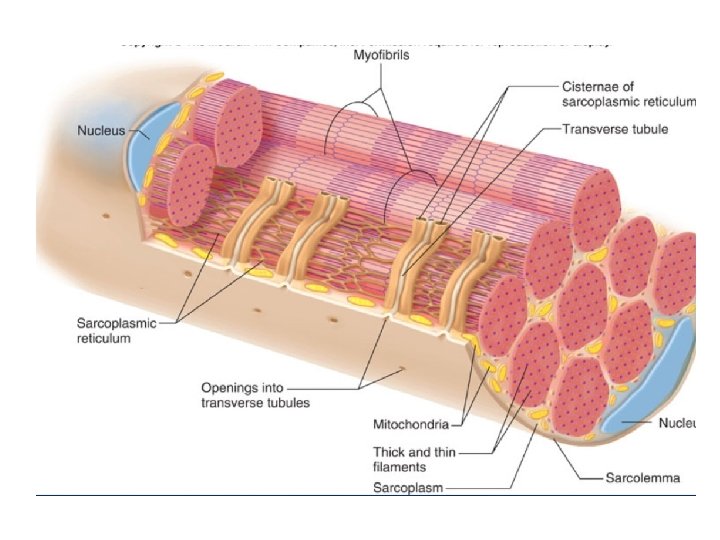

MUSCLE STRUCTURE • Striated muscle is composed of multinucleated muscle fiber cells. • Each muscle fibre is composed of several myofibrils that are surrounded by an electrically excitable membrane called the sarcolemma. • A muscle fibre contains bundles of myofibril arranged in parallel • The myofibrils are immersed in a cytosol (Sarcoplasm) • Sarcoplasm is rich in glycogen, ATP, creatine phosphate and glycolytic enzymes. • Many regularly spaced mitochondria are found in the more active muscles. • Myofibrils exhibit a longitudinally long repeating structure called the sarcomere, which is the functional unit of a myofibril.

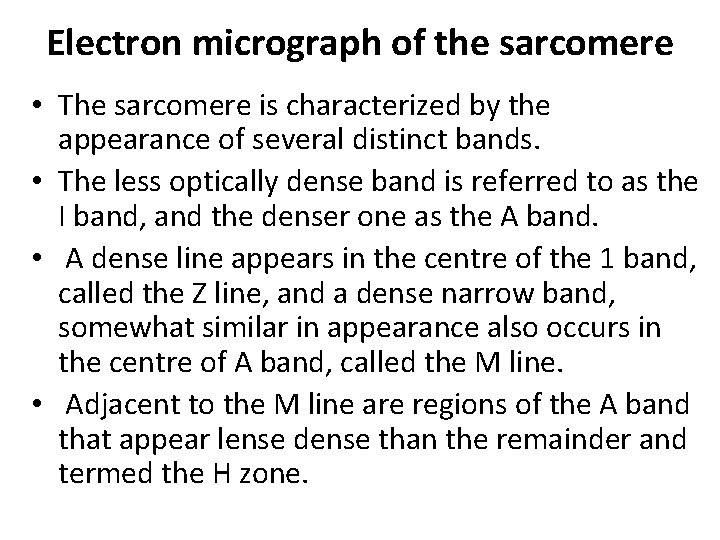

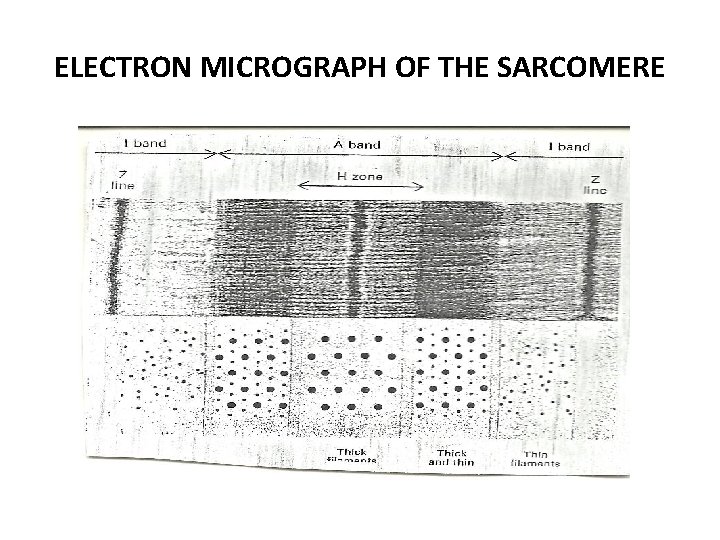

Electron micrograph of the sarcomere • The sarcomere is characterized by the appearance of several distinct bands. • The less optically dense band is referred to as the I band, and the denser one as the A band. • A dense line appears in the centre of the 1 band, called the Z line, and a dense narrow band, somewhat similar in appearance also occurs in the centre of A band, called the M line. • Adjacent to the M line are regions of the A band that appear lense dense than the remainder and termed the H zone.

ELECTRON MICROGRAPH OF THE SARCOMERE

• Transverse sections of the sarcomere reveal that the above pattern result from the interdigitation of the two sets of protein filament- the thin (ACTIN) and the thick (MYOSIN) filaments. • The thin filament contains ACTIN, TROPOMYOSIN and TROPONIN • The 1 band consists of the thin filaments, while the H zone consists of thick filament but the A band shows a regularly packed array of interdigitating thick and thin filaments.

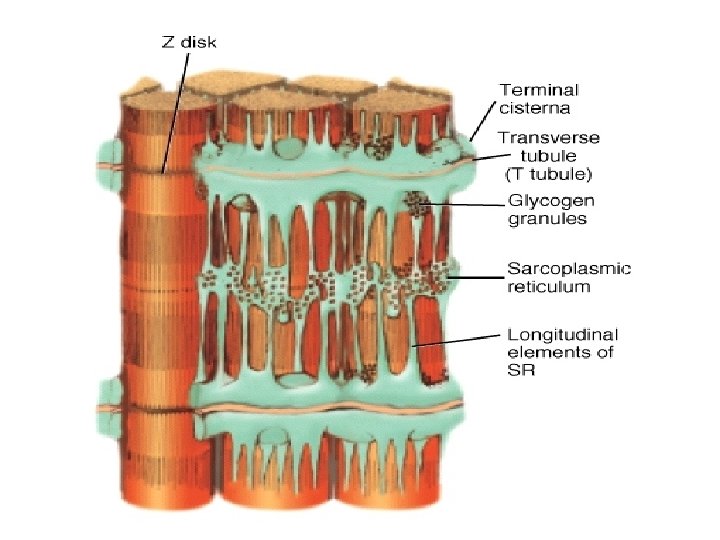

• Sarcolemmal invagination gives rise to small membranous folds, known as the transverse tubules (T-tubules) which extend from the sarcolemma and surround each myofibril at the Z line. • The sarcoplasmic reticulum is a sheath of flattened vessicles that surround the myofibrils like a net and stores large quantities of calcium at its terminal cisternae.

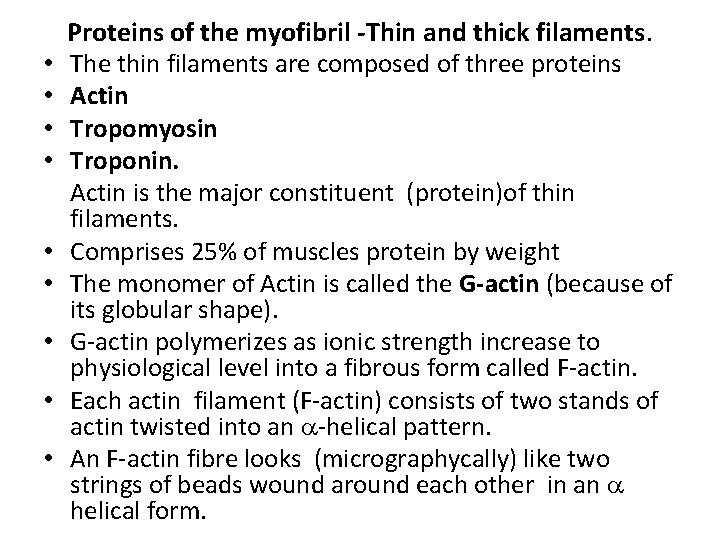

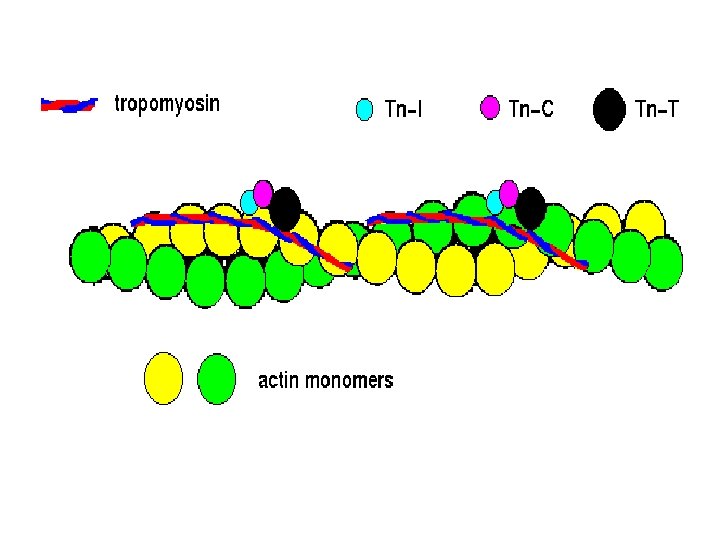

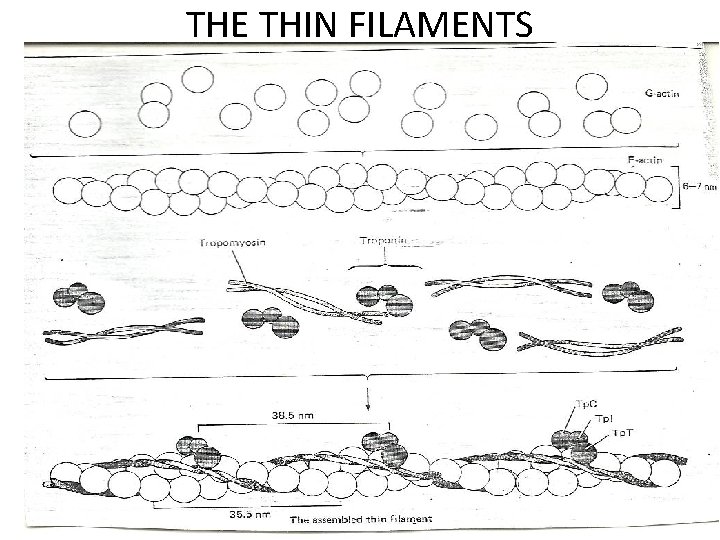

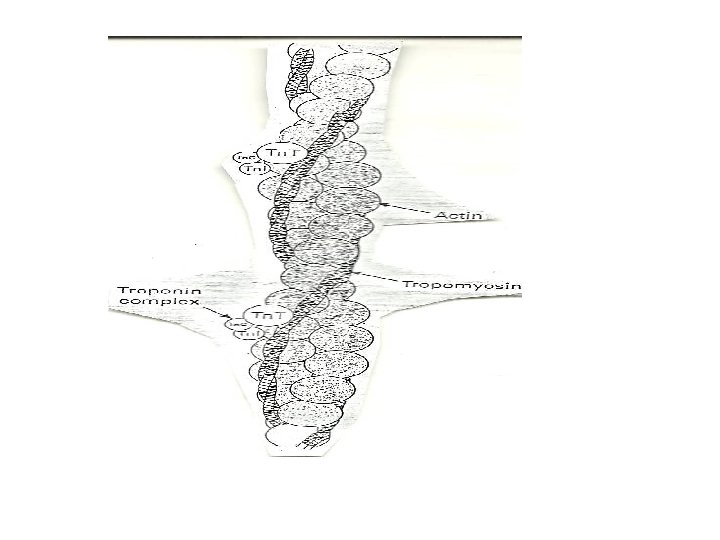

• • • Proteins of the myofibril -Thin and thick filaments. The thin filaments are composed of three proteins Actin Tropomyosin Troponin. Actin is the major constituent (protein)of thin filaments. Comprises 25% of muscles protein by weight The monomer of Actin is called the G-actin (because of its globular shape). G-actin polymerizes as ionic strength increase to physiological level into a fibrous form called F-actin. Each actin filament (F-actin) consists of two stands of actin twisted into an -helical pattern. An F-actin fibre looks (micrographycally) like two strings of beads wound around each other in an helical form.

THE THIN FILAMENTS

• Tropomyosin (TM) is a filamentous protein containing two subunits in an -helical form. • It lies in the groove on either side of the Factin filament • mediates access to the site on actin monomers that bind to the myosin head. § Present in cells and muscle like structures

• Troponin is a complex of three non identical subunits: TN-C (a calcium binding subunit), TN-T (a TM- binding subunit) and TN-1 (an “inhibitory” subunit). • Two molecules of troponin (TN) bind to the actin filament at each helical repeat. • Troponin T binds to tropomyosin and together with troponin I, inhibits the interaction of actin and myosin. • Troponin I binds actin and inhibits the binding of actin to myosin ie Has a strong affinity for actin Inhibits F-actin –myosin interactions • Binds to other troponin molecules

Troponin C has a binding site for Ca 2+ Binds 4 molecules of calcium when calcium is bound, actin and myosin interaction is promoted. • a calcium binding protein similar to calmodulin in function • • • Troponin is found only in striated muscle cells. • The thick and thin filaments interact via cross bridges • Interaction between this cross bridges and actin filament cause contraction • The filaments slide pass one another during contraction.

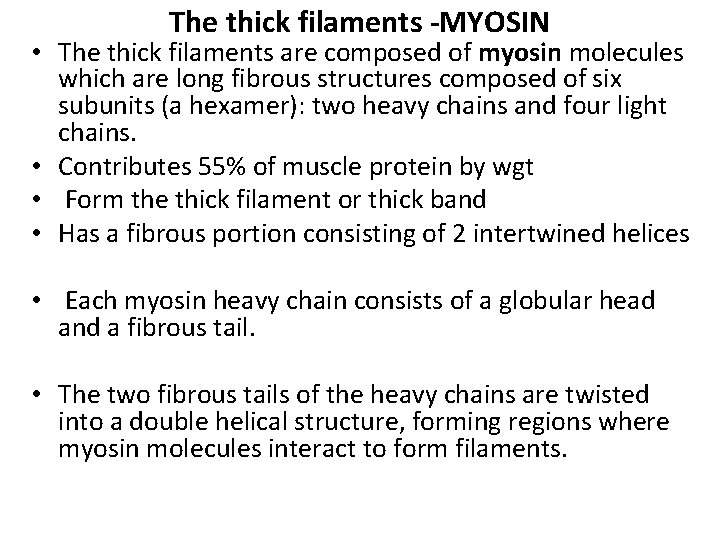

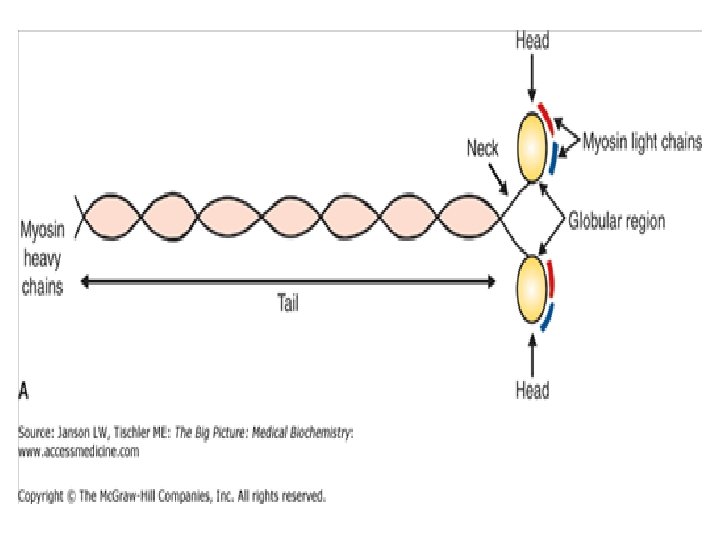

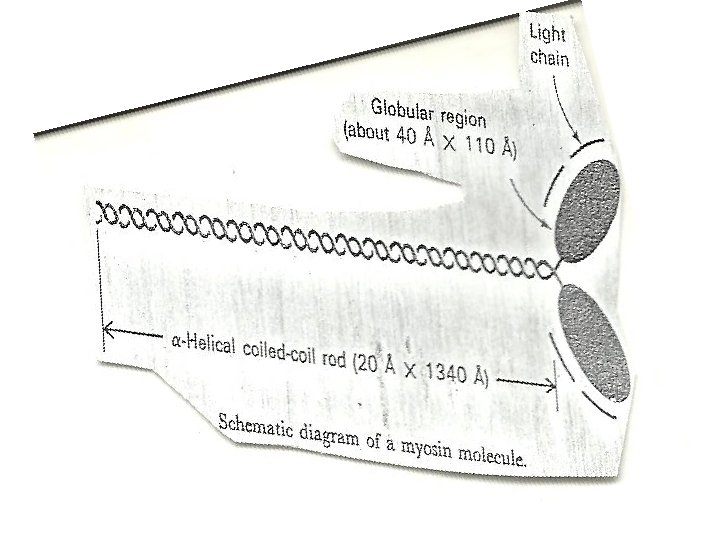

The thick filaments -MYOSIN • The thick filaments are composed of myosin molecules which are long fibrous structures composed of six subunits (a hexamer): two heavy chains and four light chains. • Contributes 55% of muscle protein by wgt • Form the thick filament or thick band • Has a fibrous portion consisting of 2 intertwined helices • Each myosin heavy chain consists of a globular head and a fibrous tail. • The two fibrous tails of the heavy chains are twisted into a double helical structure, forming regions where myosin molecules interact to form filaments.

• The globular heads of the myosin molecules contain ATpase activity as well as sites for binding to actin filaments. • The helical coils therefore form the backbone of the thick filaments. • They also form an arm that can provide a flexible extension or hinge connecting the globular head to the body of the thick filament.

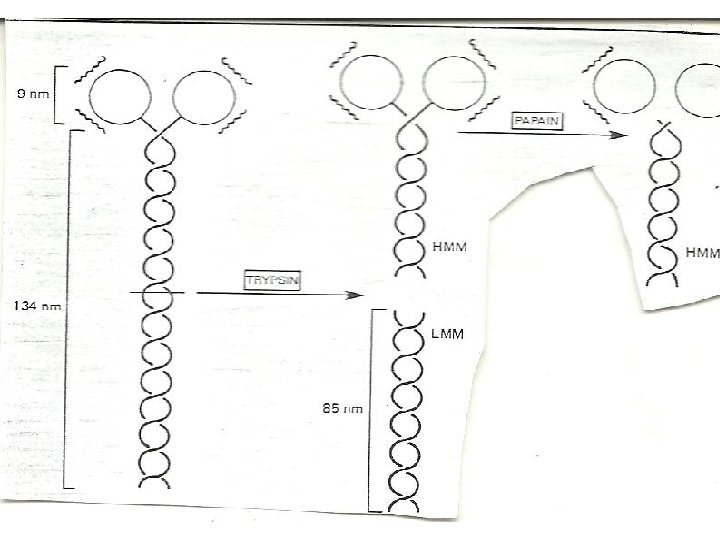

ENZYMATIC HYDROLYSIS OF MYOSIN • Myosin can be cleaved enzymatically into fragments that retain some of the activities of the intact molecule. • myosin is split by trypsin into two fragments called light meromyosin (LMM) and heavy meromyosin (HMM). • LMM like myosin tail forms filament but lack ATpase activity and does not combine with actin. • HMM catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATP and binds to actin, but does not form filaments.

• The LMM is a two stranded helical rod • LMM are insoluble alpha- helical fibres • HMM consists of a rod attached to a double headed globular region • can be split by papain into two globular fragments (called S 1) and one rod-shaped subfragment (called S 2). • S 2 fragment is fibrous • Each S 1 fragment contain an ATpase active site and a binding site for actin. • The light chains of myosin are bound to the S 1 fragments.

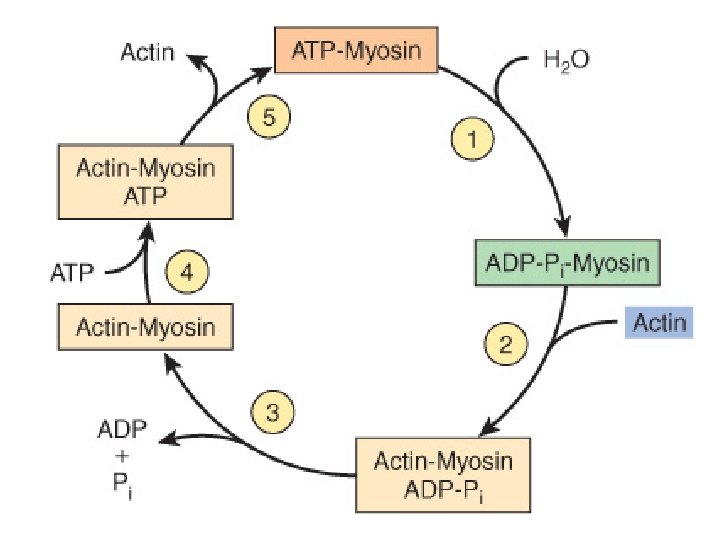

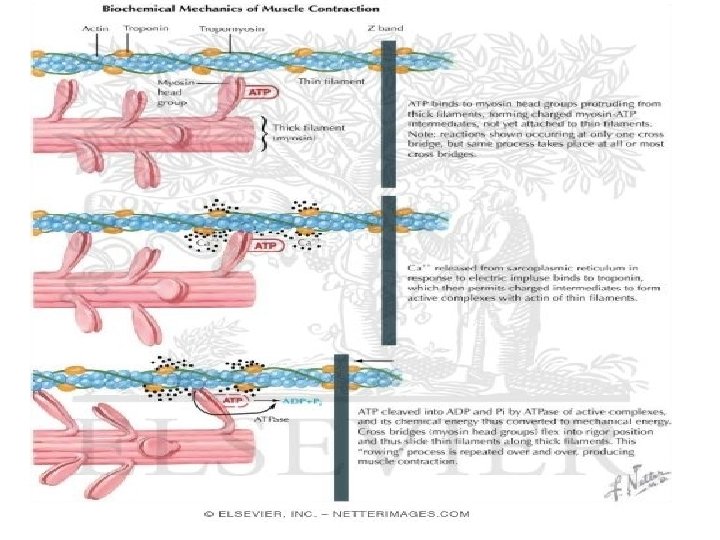

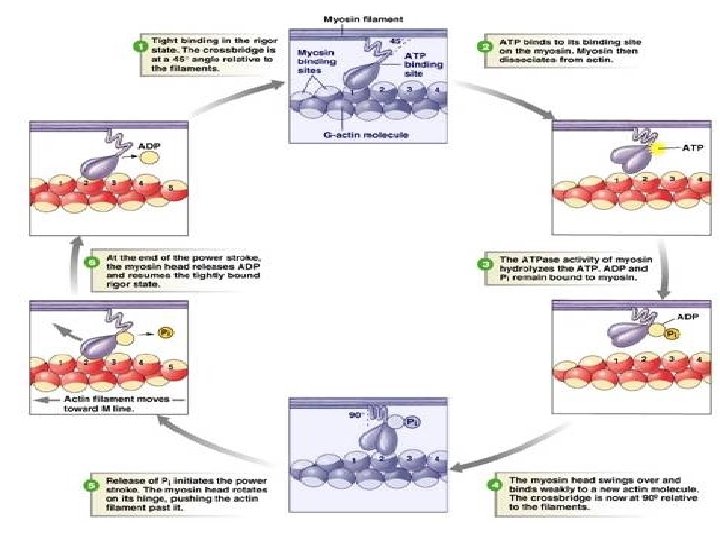

GENERAL MECHANISM OF MUSCLE CONTRACTION • The major biochemical events occurring during one cycle of muscle contraction and relaxation can be represented in the five steps shown below: • (1) In the relaxation phase of muscle contraction, the S-1 head of myosin hydrolyzes ATP to ADP and Pi but these products remain bound. • The resultant ADP-Pi-myosin complex has been energized and is in high-energy conformation.

• (2) When contraction of muscle is stimulated (via events involving Ca 2+, troponin, tropomyosin, and actin, which are described below later), actin becomes accessible. • The S-1 head of myosin finds it, binds it • forms the actin-myosin-ADP-Pi complex – so called actinomyosin-ADP-Pi complex.

• (3) Formation of this complex promotes the release of Pi, which initiates the power stroke. • This step which is followed by release of ADP is accompanied by a large conformational change in the head of myosin in relation to its tail , pulling actin about 10 nm toward the center of the sarcomere. • This is the power stroke. • The myosin is now in a low-energy state, indicated as actin-myosin.

• (4) Another molecule of ATP binds to the S-1 head, forming an actin-myosin-ATP complex. • (5) Myosin-ATP has a low affinity for actin, and actin is thus released. This last step is a key component of relaxation and is dependent upon the binding of ATP to the actin-myosin complex.

DETAILS • STEPS IN MUSCLE CONTRACTION • 1. The process of muscular contraction entails a sliding of the thick and thin filaments past each other. • The movement of myosin (thick filaments) along the actin ( thin filament) is ATP dependent. • This contraction is a cyclical process. • 2. The myosin head binds ATP, which is hydrolyzed to ADP and Pi by myosin ATpase. • ADP and Pi remain bound to the ATpase site.

• 3. The myosin head moves to an adjacent thin (actin) filament (the binding site) and as it makes contact with the actin binding site, Pi is released. • The release of pi is the rate-limiting step in muscular contraction. • 4. Strong cross-bridges form between actin and myosin which is followed by a structural alteration (conformational change) in the myosin molecules and an effective translocation of the thick filament relative to the thin filament • ie large conformational change in the head of myosin in relation to its tail , pulling actin about 10 nm toward the center of the sarcomere. • During this process, the ADP is released.

• 5. After the translocation step, the bridge structure is broken by the binding of ATP, which is hydrolysed to ADP and pi. • Hydrolysis of ATP result in the myosin head resuming its original conformation and is then ready for another cycle further along. • The contraction process therefore involves the breakage and reformation of bridges between the actin and myosin molecules in a reaction that requires the expenditure of ATP. • Each thick filament has about 500 myosin heads and each head cycles about five times per second in the course of a rapid contraction.

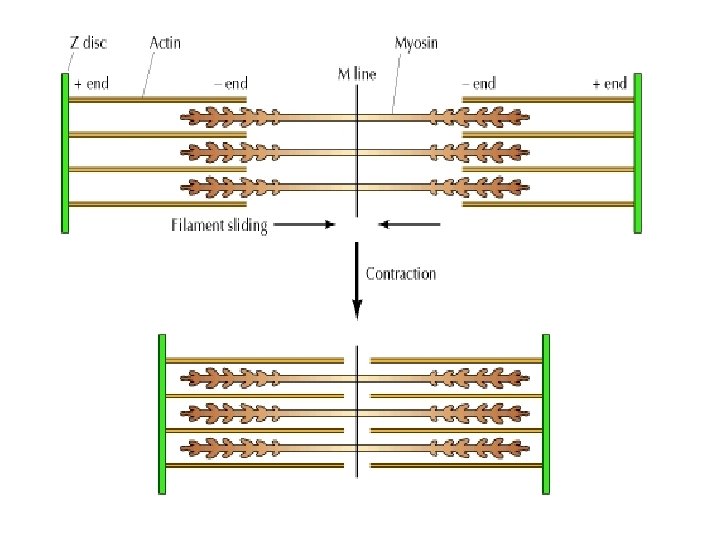

• In a fully contracted myofibril, the actin and myosin filament show a maximum overlap with each. • However there is no change in the length of either types of filament (see diagrams below). In other words during contraction • 1. The Z lines approach one another • 2. The sarcomere get smaller and • 3. The A band, does not change size.

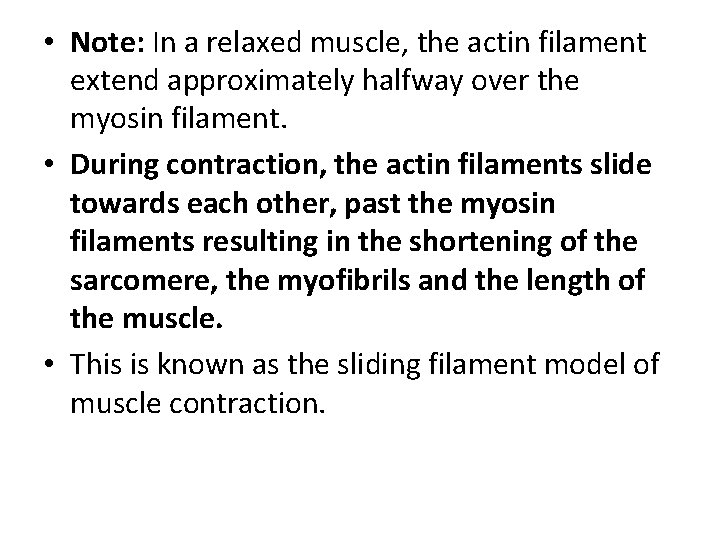

• Note: In a relaxed muscle, the actin filament extend approximately halfway over the myosin filament. • During contraction, the actin filaments slide towards each other, past the myosin filaments resulting in the shortening of the sarcomere, the myofibrils and the length of the muscle. • This is known as the sliding filament model of muscle contraction.

• The sliding filament cross-bridge model is the foundation of current thinking about muscle contraction. • The basis of this model is that the interdigitating filaments slide past one another during contraction and cross-bridges between myosin and actin generate and sustain the tension. • The hydrolysis of ATP is therefore used to drive movement of the filaments.

• REGULATION OF MUSCLE CONTRACTION: ROLE OF TROPONIN AND TROPOMYOSIN IN MUSCULAR CONTRACTION. • Control of muscle contraction is provided by troponin, tropomyosin, and a change in intracellular calcium concentration. • When the calcium ion concentration is low (10 -7 M), troponin I and troponin T are strongly bound to tropomyosin, holding it in the actin groove so that it blocks the myosin binding site on the actin monomers. • Troponin C is either loosely associated with tropomyosin or is bound to troponin I and troponin T.

• When calcium concentration increase above 10 -7 M in the cell, troponin C binds calcium and undergoes change in conformation, forcing troponin I and troponin T to move. • The movement exposes the myosin binding site on the actin by the removal of tropomyosin, permitting interaction between the two filaments to occur. • This however does not necessarily result in contraction; contraction can result only if ATP is present.

• CONTROL OF INTRACELLULAR CALCIUM CONCENTRATIONS. • Small membranous folds, known as T-tubules extend from the sarcolemma and surround each myofibril at the Z line-see earlier. • The T-tubules act as a communication system for the depolarization of the plasma membrane that occurs when a nervous stimulation signals the muscle to contract. • Depolarization of the sarcolemma is relayed to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), a sheath of flattened vesicles that surround the myofibrils and store large quantities of calcium. • Normally, extracellular calcium concentrations are high (10 -3 M) whereas those in the cytosol are low (10 -7 M). Upon depolarization, the calcium level rise from 10 -7 to greater than 10 -5 m during contraction.

• The increase is due primarily to the movement of calcium ions through ca 2+ release channels in the membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. • The change in calcium concentration occurs rapidly and relieves the inhibition of myosin binding to actin. • Once the stimulation of the nerves cease, calcium is pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum by the action of a SR- specific ATpase. • The calcium is bound in the SR calsequesterin, an acidic protein with a high density of aspartate and glutamate residues.

• ACTIN-BINDING DRUGS • Can interfere with the polymerizeationdepolymerization cycle of microfilaments. • Cytochalasin B inhibits the assembly of actin filaments by binding to one end of the filament and preventing the addition of actin molecules to the filament. • Processes such as endocytosis, cytokinesis, cytoplasmic and amoeboid movements are all inhibited by cytochalasin B. • Phallodin binds along the length of actin filament, preventing depolymerization.

• ACCESSORY PROTEINS OF THE MYOFIBRIL. • Several other proteins are associated with the sarcomere. Their location and functions are as follows: • Titin • is a large fibrous protein that extends over half of the sarcomere (reaches from the Z line to the M line) • It has elastic properties and keep the myosin thick filaments centred in the sarcomere. • Largest protein in the body. • It plays a role in relaxation of muscle. • May regulate assembly and lenght of filaments • Nebulin • is a large fibrous protein attached to the Z-line and extends the length of the thin filament. • It stabilizes the highly ordered structure of the myofibril by regulating the assembly of the actin filaments.

• • • α-Actinin Anchors actin to Z lines. Stabilizes actin filaments. Desmin is found in Z line, where it holds myofibril in place. It gives the muscle its “Striated” appearance. Attaches to plasma membrane (plasmalemma). Dystrophin Attached to plasmalemma Deficient in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mutations of its gene can also cause dilated cardiomyopathy.

• • • Calcineurin Present in the Cytosol A calmodulin-regulated protein phosphatase. May play important roles in cardiac hypertrophy and in regulating amounts of slow and fast twitch muscles. Myosin- binding protein C Arranged transversely in sarcomere A-bands Binds myosin and titin Plays a role in maintaining the structural integrity of the sarcomere. Myomesin- cross-links adjacent filaments at the M-line (the centre of the sarcomere).

• Sequence of events in contraction and relaxation of skeletal muscle. • Steps in contraction • (1) Discharge of motor neuron • (2) Release of transmitter (acetylcholine) at motor endplate • (3) Binding of acetylcholine to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors • (4) Increased Na+ and K+ conductance in endplate membrane • (5) Generation of endplate potential • (6) Generation of action potential in muscle fibers

• (7) Inward spread of depolarization along T tubules • (8) Release of Ca 2+ from terminal cisterns of sarcoplasmic reticulum and diffusion to thick and thin filaments • (9) Binding of Ca 2+ to troponin C, uncovering myosin binding sites of actin • (10) Formation of cross-linkages between actin and myosin and sliding of thin on thick filaments, producing shortening

• Steps in relaxation • (1) Ca 2+ pumped back into sarcoplasmic reticulum • (2) Release of Ca 2+ from troponin • (3) Cessation of interaction between actin and myosin

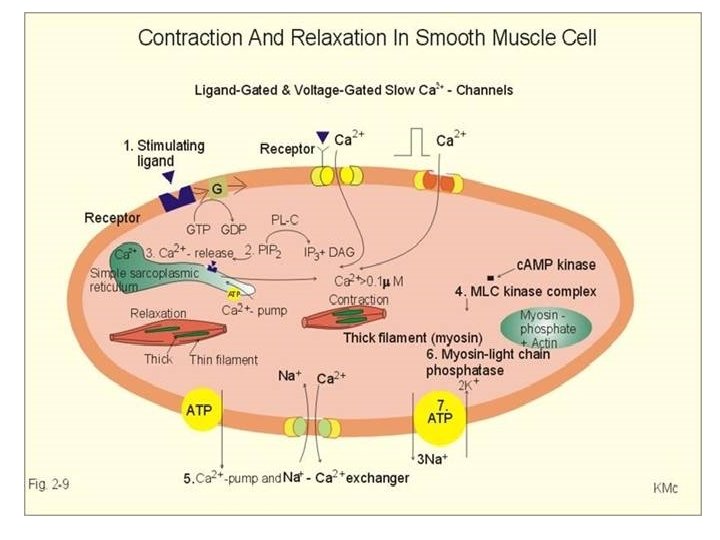

• Smooth muscle: differs from skeletal muscle in various ways. • Smooth muscles-which are found, for example, in blood vessel walls and in the walls of the intestines-do not contain any muscle fibers. • In smooth-muscle cells, which are usually spindle-shaped, the contractile proteins are arranged in a less regular pattern than in striated muscle.

• The smooth muscle contain actin filament attached to the plasma membrane as well as myosin filaments, but the fibrils are not aligned, thus when myosin slides along the filament, the cell contracts in all direction.

• Contraction in this type of muscle is usually not stimulated by nerve impulses, but occurs in a largely spontaneous way. • Ca 2+ (in the form of Ca 2+-calmodulin); also activates contraction in smooth muscle; • in this case, however, it does not affect troponin, but activates a protein kinase that phosphorylates the light chains in myosin and thereby increase myosin’s ATPase activity. • All the Ca 2+ are from the ECF and there is no troponin.

• MUSCLE METABOLISM 1 • The metabolic profile of the muscle • The major fuels for muscle are glucose, fatty acids and Ketone bodies. • Muscle has a large store of glycogen (1, 200 Kcal). • About 3/4 of all the glycogen in the body is stored in muscle. • Muscle contraction is associated with a high level of ATP consumption. • Without constant resynthesis, the amount of ATP available in the resting state would be used up in less than I second of contraction.

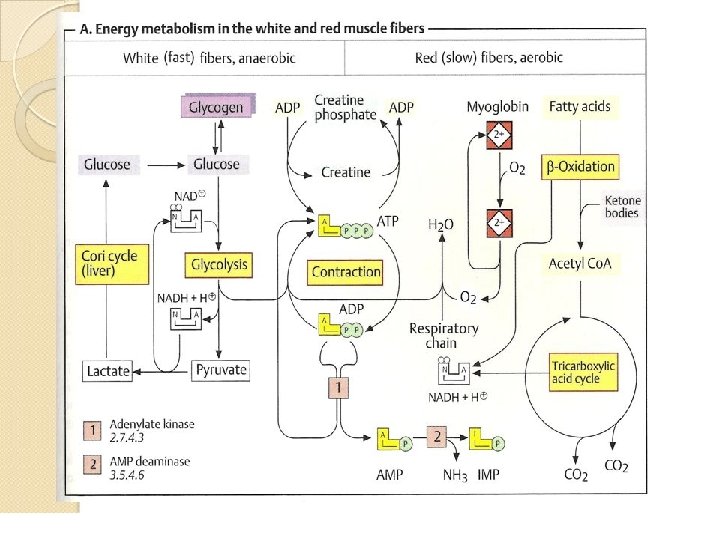

• A. Energy metabolism in the white and red muscle fibers • Muscles contain two types of fibers, the proportions of which vary from one type of muscle to another. • Red fibers (type I or slow fibers) are suitable for prolonged effort. • Their metabolism is mainly aerobic and therefore depends on an adequate supply of O 2. • White fibers (types 11 or fast fibers) are better suited for fast, strong contractions. • These fibers are able to form sufficient ATP even when there is little O 2 available

• With appropriate training, athletes and sports participants are able to change the proportions of the two fiber types in the musculature • This prepare themselves for the physiological demands of their disciplines in a targeted fashion. • The expression of functional muscle proteins can also change during the course of the training.

• Red fibers provide for their ATP requirements mainly (but not exclusively) from fatty acids, which are broken down via β-oxidation, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and the respiratory chain. • The red color in these fibers is due to the monomeric heme protein myogobin which they use as an O 2 reserve. • Myoglobin has a much higher affinity for 02 than hemoglobin and therefore only releases its O 2 when there is a severe drop in O 2 partial pressure.

• At a high level of muscular effort-e. g, during weightlifting or in very fast contractions such as those carried out by the eye muscles-the 02 supply from the blood quickly becomes inadequate to maintain the aerobic metabolism. • White fibers therefore mainly obtain ATP from anaerobic glycolysis. They have supplies of glycogen from which they can quickly release glucose-1 -phosphate when needed.

• By isomerization, this gives rise to glucose-6 phosphate, the substrate for glycolysis. • The NADH+H+ formed during glycolysis has to be reoxidized into NAD+ in order to maintain glucose degradation and thus ATP formation. • If there is a lack of O 2, this is achieved by the formation of lactate, which is released into the blood and is resynthesized into glucose in the liver (cori cycle).

• Muscle-specific auxiliary reactions for ATP synthesis exist in order to provide additional ATP in case of emergency. • Creatine phosphate acts as a buffer for the ATP level. • Another ATP-supplying reaction is catalysed by adenylate kinase [1]. • This disproportionates two molecules of ADP into ATP and AMP. • The AMP is deaminated into IMP in a subsequent reaction [2] in order to shift the balance of the reversible reaction [1] in the direction of ATP formation.

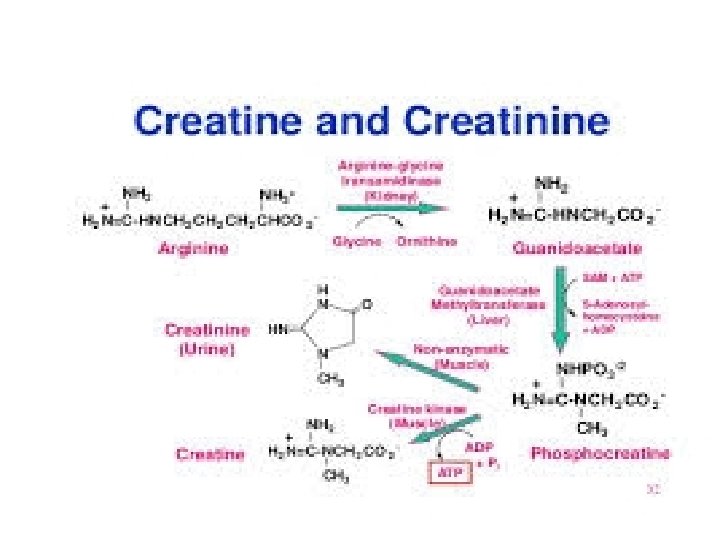

• B. creatine metabolism • Creatine (N-methylguanidoacetic acid) and its phosphorylated form creatine phosphate (a guanidophosphate) serve as an ATP buffer in muscle metabolism. • In creatine phosphate, the phosphate residue is at a similarly high chemical potential as in ATP and is therefore easily transferred to ADP. • Conversely when there is an excess of ATP, creatine phosphate can arise from ATP and creatine. • Both processes are catalyzed by creatine kinase [5].

• In resting muscle, creatine phosphate forms due to the high level of ATP. • If there is a risk of a severe drop in the ATP level during contraction, the level can be maintained for a short time by synthesis of ATP from creatine phosphate and ADP. • In a nonenzymatic reaction [6] , small amounts of creatine and creatine phosphate cyclizes constantly to form creatinine which can no longer be phosphorylated and is therefore excreted with the urine.

• Creatine does not derive from the muscles themselves, but is synthesized in two steps in the kidneys and liver. • Initially, the guanidino group of arginine is transferred to glycine in the kidneys, yielding guanidino acetate [3]. • In the liver, N-methylation of guanidino acetate leads to the formation of creatine from this [4]. • The coenzyme in this reaction is S-adenosyl methionine (SAM).

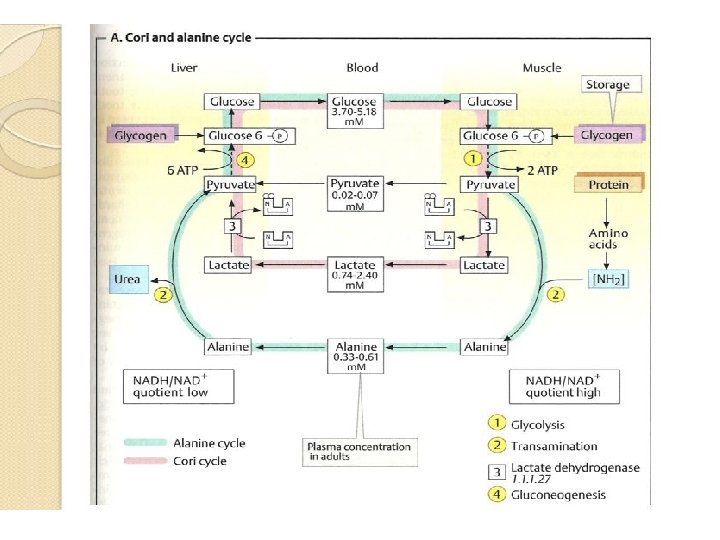

• MUSCLE METABOLISM 11 • A. cori and alanine cycle • White muscle fibers mainly obtain ATP from anaerobic glycolysis-i. e, they convert glucose into lactate. • The lactate arising in muscle and, in smaller quantities, its precursor pyruvate are released into the blood and transported to the liver, where lactate and pyruvate are resynthesize into glucose again via gluconeogenesis, with ATP being consumed in the process.

• The glucose newly formed by the liver returns via the blood to the muscles, where it can be used as an energy source again. • This circulation system is called the cori cycle. • There is also a very similar cycle for erythrocytes, which do not have mitochondria and therefore produce ATP by anaerobic glycolysis.

• The muscle themselves are not capable of gluconeogenesis nor would this be useful, as gluconeogenesis requires much more ATP than is supplied by glycolysis. • As 02 deficiencies do to not arise in the liver even during intensive muscle work, there is always sufficient energy there available for gluconeogenesis. • There is also a corresponding cycle for the amino acid alanine. • The alanine cycle in the liver not only provides alanine as a precursor for gluconeogenesis, but also transports to the liver the amino nitrogen arising in muscles during protein degradation. • In the liver, it is incorporated into urea for excretion.

• Most of the amino acids that arise in muscle during proteolysis are converted into glutamate and -keto acids by transamination. • Again by transamination, glutamate and pyruvate give rise to -ketoglutarate and alanine, which after glutamate, is the second important form of transport for amino nitrogen in the blood. • In the liver, alanine and keto-glutarate are resynthesized into pyruvate and glutamate. • Glutamate supplies the urea cycle, while pyruvate is available for gluconeogensis.

• B. protein and amino acid metabolism • The skeletal muscle is the most important site for degradation of the branched-chain amino acids (val, leu, lle), but other amino acids are also broken down in the muscles. • Alanine and glutamine are resynthesiszed from the components and released into the blood. • They transport the nitrogen that arises during amino acid breakdown to the liver (alanine cycle) and to the kidneys.

• During periods of hunger, muscle proteins serve as an energy reserve for the body. • They are broken down into amino acids, which are transported to the liver. • In the liver, carbon skeletons of the amino acids are converted into intermediates in the tricarboxylic acid cycle or into acetoacetyl-COA. • These amphibolic metabolites are then available to the energy metabolism and for gluconeogenesis. • After prolonged starvation, the brain switches to using ketone bodies in order to save muscle protein.

• The synthesis and degradation of muscle proteins are regulated by hormones. • Cortisol leads to muscle degradation, while testosterone stimulates protein formation. • Synthetic anabolics with a testosterone-like effect have repeatedly been used for doping purposes or for intensive muscle-building. • . Note-In general for energy provision, red muscles use fatty acids, ketone bodies also serve as fuel especially for the heart muscles; • white muscles use mainly glucose and in resting muscle, fatty acids are the major fuel.

• OXYGEN DEBT • In actively contracting skeletal muscle, the rate of glycolysis far exceeds that of TCA cycle. • Much of the pyrurate formed under these conditions is reduced to lactate, which flows to the liver, where it is converted into glucose (via gluconeogenesis). • These interchanges, known as the cori cycle shifts the metabolic burden of the muscle to the liver.

• After a period of maximal muscular exertion, such as a sprint, during which lactate appears in the blood in large amount, an animal will continue to breath in excess of the normal resting state and consumes considerable extra oxygen. • The extra oxygen so consumed during the recovery period is called the oxygen debt and correspond to the oxidation of some or all the excess lactate formed during maximal muscular contraction.

- Slides: 79