Binary Decision Diagrams Sungho Kang Yonsei University Outline

Binary Decision Diagrams Sungho Kang Yonsei University

Outline l l l Representing Logic Function Design Considerations for a BDD package Algorithms CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 2

Why BDDs l l l Representing Logic Function BDDs are Canonical (each Boolean function has its own unique BDD, modulo ordering of variables) So two functions are identical if and only if their BDDs are identical BDDs are compact in many cases, compared to SOP § Parity trees, adders, control logic (linear vs exponential) § However multipliers are bad, and a few others CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 3

Why not SOP and POS l l Representing Logic Function The two-level representations of some functions are too large to be practical (e. g. XOR) Passing from SOP to POS and vice versa is difficult § Taking the complement is difficult § Taking the AND/OR of two sums of products is difficult Since SOP and POS are not canonical forms, answering the equivalence question for two functions is difficult Furthermore, deciding whether a product of sums is satisfiable is NP-complete CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 4

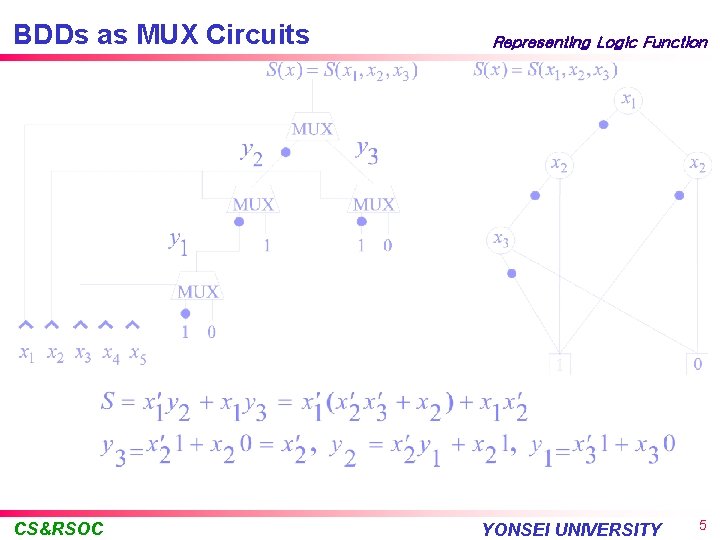

BDDs as MUX Circuits CS&RSOC Representing Logic Function YONSEI UNIVERSITY 5

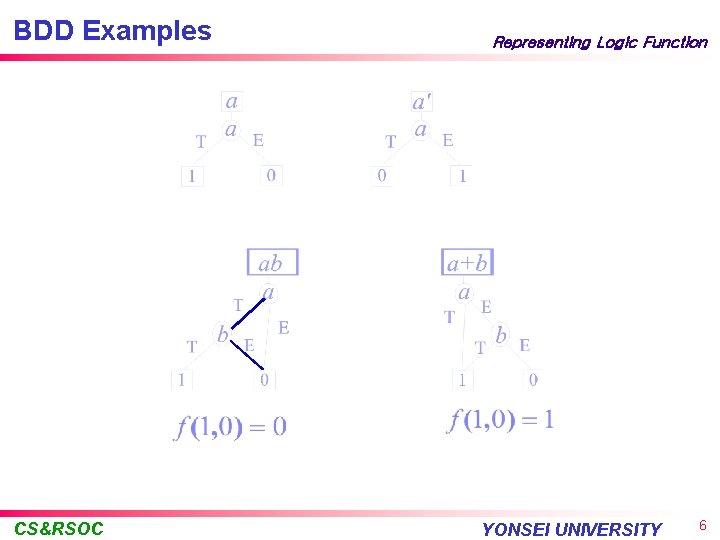

BDD Examples CS&RSOC Representing Logic Function YONSEI UNIVERSITY 6

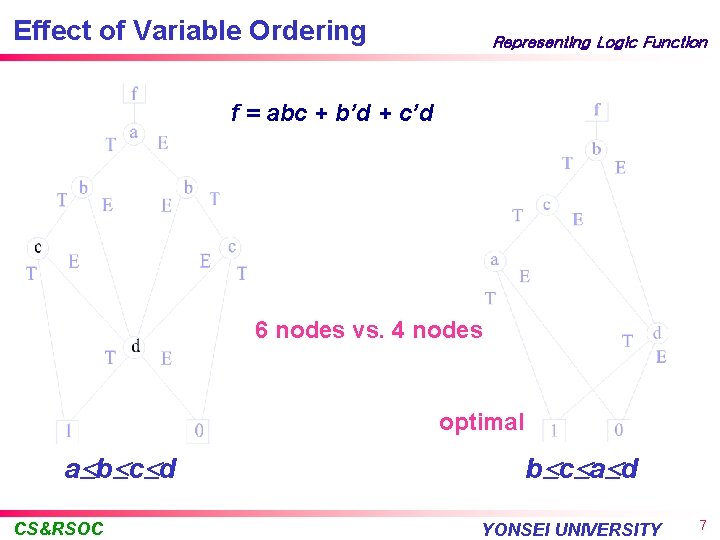

Effect of Variable Ordering Representing Logic Function f = abc + b’d + c’d 6 nodes vs. 4 nodes optimal a b c d CS&RSOC b c a d YONSEI UNIVERSITY 7

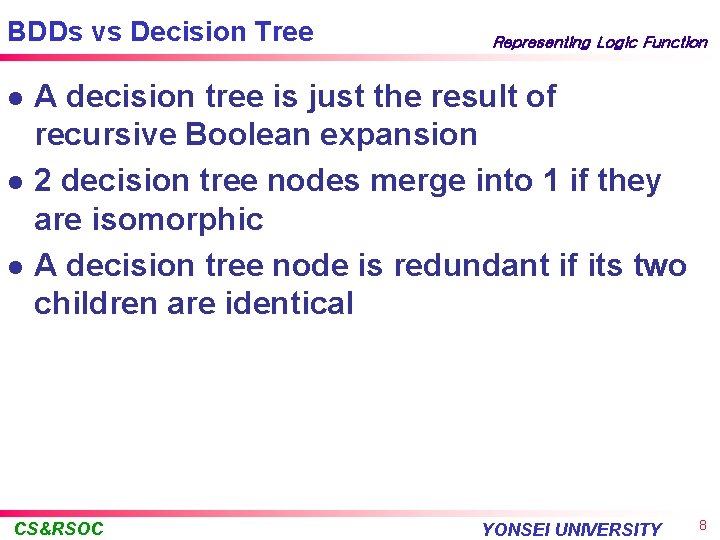

BDDs vs Decision Tree l l l Representing Logic Function A decision tree is just the result of recursive Boolean expansion 2 decision tree nodes merge into 1 if they are isomorphic A decision tree node is redundant if its two children are identical CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 8

Formal Definition l l l Representing Logic Function A BDD is a directed acyclic graph representing a multiple output switching function F The function of the terminal node is the constant function 1 The function of an edge is the function of the head node, unless the edge has the complement attribute, in which case the function of the edge is the complement of the function of the node The function of a node v in V is given by l(v)f. T+l(v)’f. E where l(v) is label of v and f. T(f. E) is the function of the T(E) edge The function of is the function of its outgoing edge CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 9

Formal Definition l l Representing Logic Function An edge with (without) the attribute is called a complement (regular) edge BDDs are canonical if § All internal nodes are descendents of some node in § There are no isomorphic subgraphs § For every node, f. T FE CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 10

ROBDD l l Representing Logic Function Reduced Ordered BDD Iteration of applying identification of isomorphic subgraphs and removal of redundant nodes Two functions are equivalent if they have the same BDD The size of the BDD is exponential in the number of variables in the worst case(e. g. multiplier) § However BDDs are well-behaved for many functions that are not amenable to two-level representations l The logical AND and OR of BDDs have the same complexity (polynomial in the size of the operands) § Complementation is inexpensive l Both satisfiability and tautology can be solved in constant time § Indeed f is a tautology iff its BDD consists of the terminal node 1 CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 11

ROBDD l l Representing Logic Function Covering problems can be solved in time linear in the size of BDD representing the constraints BDD sizes depend on the ordering § Finding a good ordering is not always simple l There are functions for which SOP or POS representations are mode compact than BDDs § Unfortunately, many constraint functions of covering problems fall into this category l In some cases SOP/POS forms are closer to the final implementation of a circuit § For instance, if we want to implement a PLA, we need to generate at some point a SOP or POS form CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 12

Building (RO)BDDs Representing Logic Function 1 Order variables 2 Recursively cofactor the given SOP, in the specified order, until the cofactors become constants or single variables; 3 Merge any pair of equivalent nodes; 4 Delete any node which has identical child nodes; 5 Repeat the merge and delete steps, until neither applies to any node CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 13

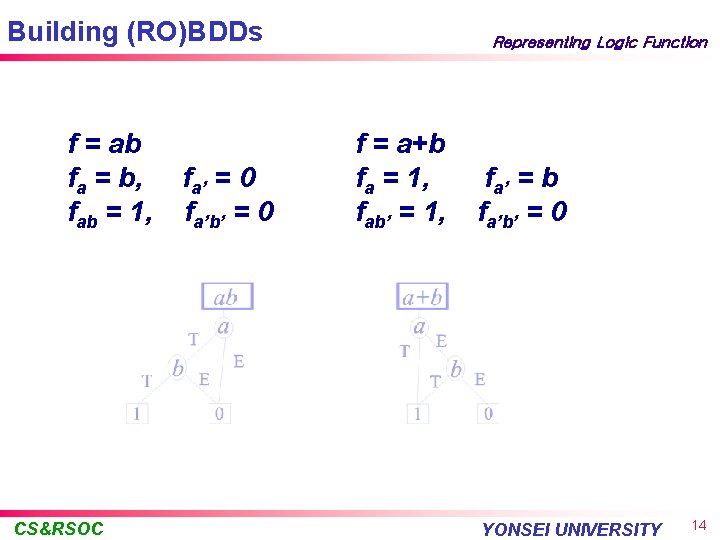

Building (RO)BDDs f = ab fa = b, fab = 1, CS&RSOC fa’ = 0 fa’b’ = 0 Representing Logic Function f = a+b fa = 1, fab’ = 1, fa’ = b fa’b’ = 0 YONSEI UNIVERSITY 14

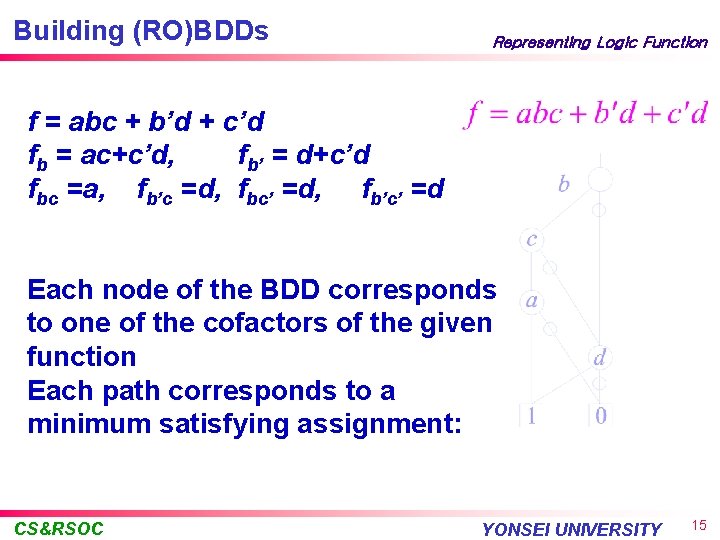

Building (RO)BDDs Representing Logic Function f = abc + b’d + c’d fb = ac+c’d, fb’ = d+c’d fbc =a, fb’c =d, fbc’ =d, fb’c’ =d Each node of the BDD corresponds to one of the cofactors of the given function Each path corresponds to a minimum satisfying assignment: CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 15

BDDs are Efficient Representing Logic Function If the BDDs of functions f and g are available, then the following may be checked in constant time: • f=0? • f=1? • f=g’? CS&RSOC (hard with SOP) (hard with SOP or POS) YONSEI UNIVERSITY 16

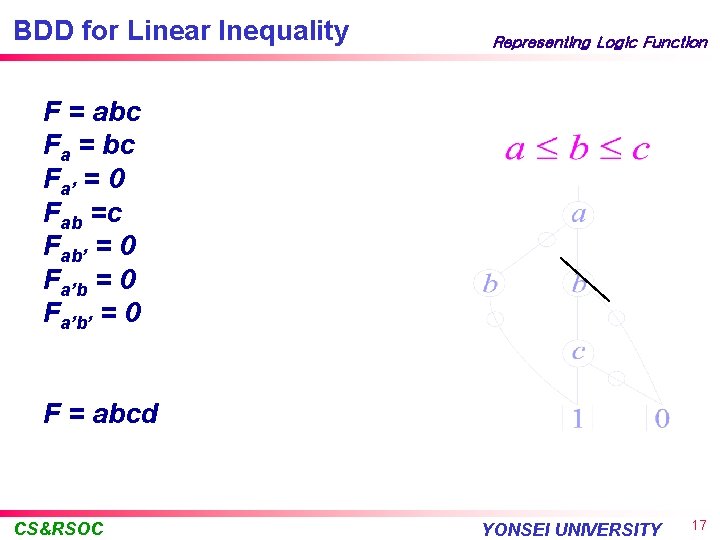

BDD for Linear Inequality Representing Logic Function F = abc Fa = bc Fa’ = 0 Fab =c Fab’ = 0 Fa’b’ = 0 F = abcd CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 17

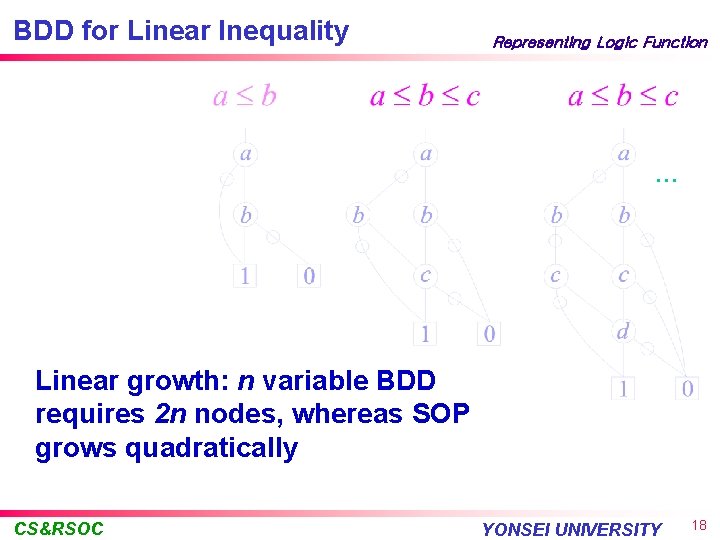

BDD for Linear Inequality Representing Logic Function . . . Linear growth: n variable BDD requires 2 n nodes, whereas SOP grows quadratically CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 18

BDDs for FSMs l l l Representing Logic Function BDDs can compactly represent huge sets Widely used to represent the set of reachable states of a Finite State Machine Used in every phase of synthesis and verification of sequential circuits CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 19

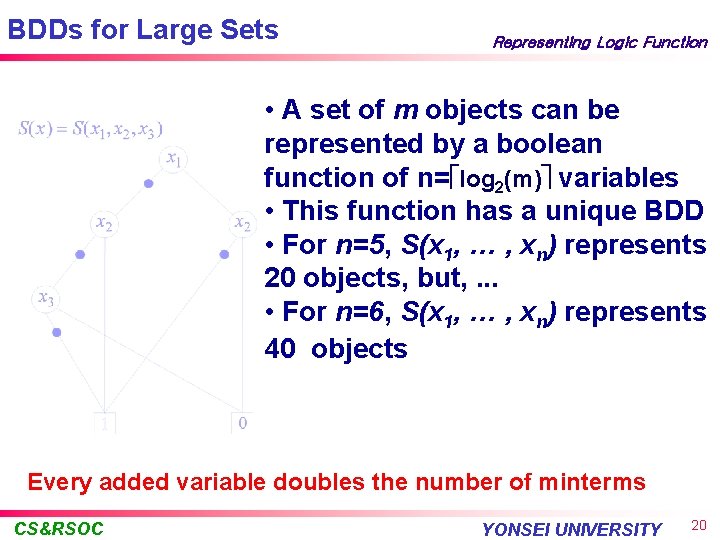

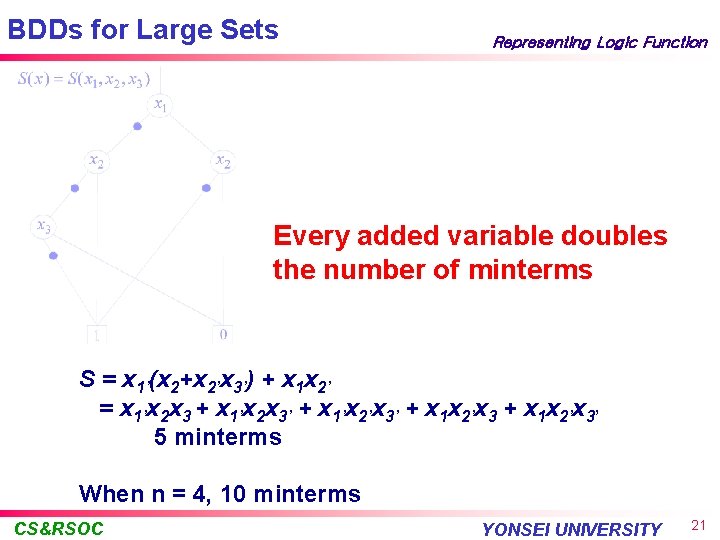

BDDs for Large Sets Representing Logic Function • A set of m objects can be represented by a boolean function of n= log 2(m) variables • This function has a unique BDD • For n=5, S(x 1, … , xn) represents 20 objects, but, . . . • For n=6, S(x 1, … , xn) represents 40 objects Every added variable doubles the number of minterms CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 20

BDDs for Large Sets Representing Logic Function Every added variable doubles the number of minterms S = x 1’(x 2+x 2’x 3’) + x 1 x 2’ = x 1’x 2 x 3 + x 1’x 2 x 3’ + x 1’x 2’x 3’ + x 1 x 2’x 3’ 5 minterms When n = 4, 10 minterms CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 21

Design Consideration of BDD Package l BDD Package Shared BDD § Two equivalent functions can be represented by the same BDD l Unique Table § Dictionary of functions represented in the DAG § Best implemented as a hash table l Strong Canonicity § Checking for equivalence just requires checking that the pointers in the DAG associated with the functions are identical l Attributed Edges § Regular edge and complement edge l Computed Table § As a speed improvement, keep a table of recently computed functions l Memory Management and Dynamic Re-Ordering § Garbage collection CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 22

BDD Graph Data Structure l l BDD Package BDD data structures are compact: § ~22 bytes/node § 106 nodes gives about 22 MB However storage is still the main issue § Spaceout on 1 GB machines common § Dynamic reordering necessary CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 23

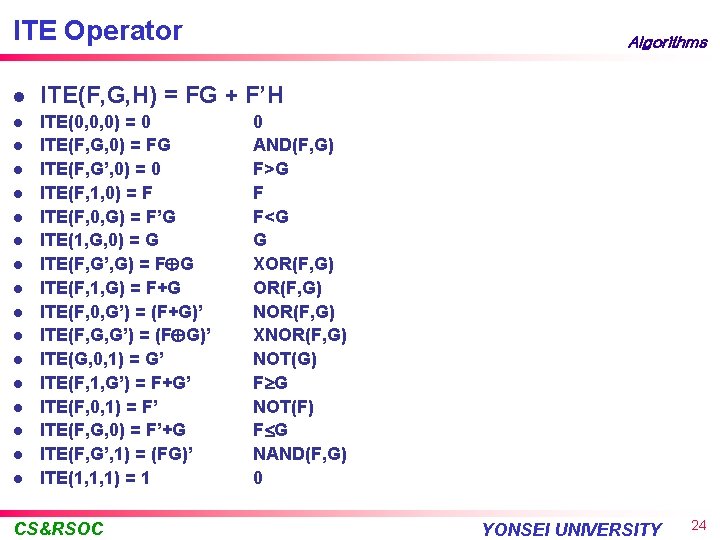

ITE Operator Algorithms l ITE(F, G, H) = FG + F’H l ITE(0, 0, 0) = 0 ITE(F, G, 0) = FG ITE(F, G’, 0) = 0 ITE(F, 1, 0) = F ITE(F, 0, G) = F’G ITE(1, G, 0) = G ITE(F, G’, G) = F G ITE(F, 1, G) = F+G ITE(F, 0, G’) = (F+G)’ ITE(F, G, G’) = (F G)’ ITE(G, 0, 1) = G’ ITE(F, 1, G’) = F+G’ ITE(F, 0, 1) = F’ ITE(F, G, 0) = F’+G ITE(F, G’, 1) = (FG)’ ITE(1, 1, 1) = 1 l l l l CS&RSOC 0 AND(F, G) F>G F F<G G XOR(F, G) NOR(F, G) XNOR(F, G) NOT(G) F G NOT(F) F G NAND(F, G) 0 YONSEI UNIVERSITY 24

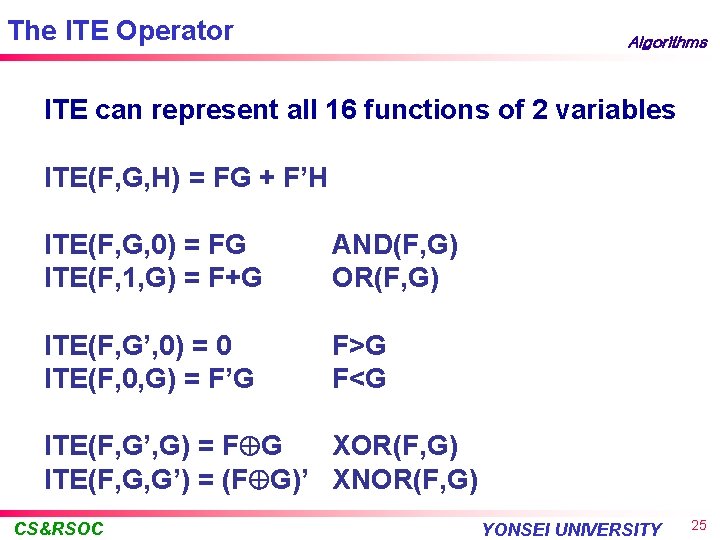

The ITE Operator Algorithms ITE can represent all 16 functions of 2 variables ITE(F, G, H) = FG + F’H ITE(F, G, 0) = FG ITE(F, 1, G) = F+G AND(F, G) OR(F, G) ITE(F, G’, 0) = 0 ITE(F, 0, G) = F’G F>G F<G ITE(F, G’, G) = F G XOR(F, G) ITE(F, G, G’) = (F G)’ XNOR(F, G) CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 25

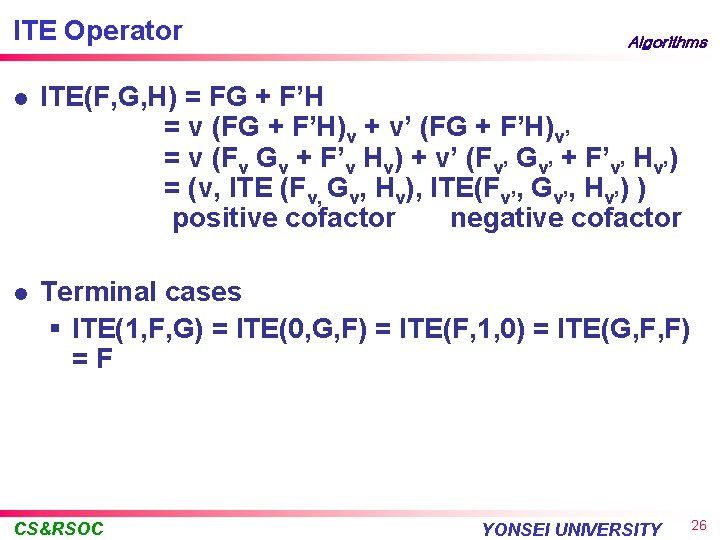

ITE Operator Algorithms l ITE(F, G, H) = FG + F’H = v (FG + F’H)v + v’ (FG + F’H)v’ = v (Fv Gv + F’v Hv) + v’ (Fv’ Gv’ + F’v’ Hv’) = (v, ITE (Fv, Gv, Hv), ITE(Fv’, Gv’, Hv’) ) positive cofactor negative cofactor l Terminal cases § ITE(1, F, G) = ITE(0, G, F) = ITE(F, 1, 0) = ITE(G, F, F) =F CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 26

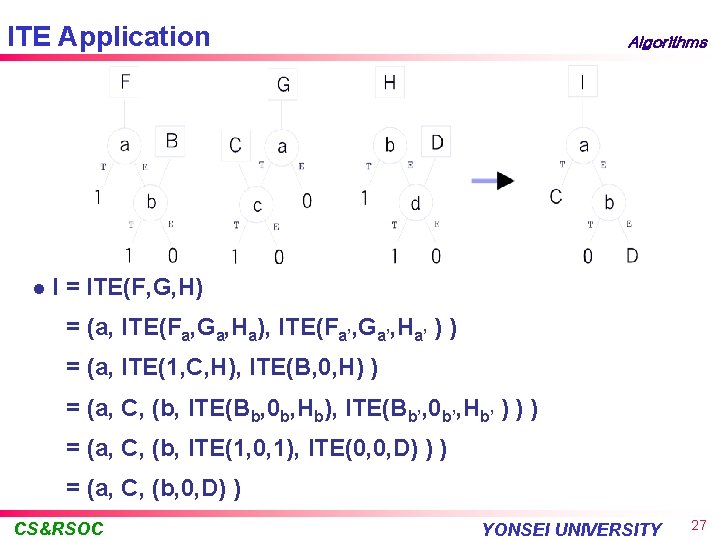

ITE Application l Algorithms I = ITE(F, G, H) = (a, ITE(Fa, Ga, Ha), ITE(Fa’, Ga’, Ha’ ) ) = (a, ITE(1, C, H), ITE(B, 0, H) ) = (a, C, (b, ITE(Bb, 0 b, Hb), ITE(Bb’, 0 b’, Hb’ ) ) ) = (a, C, (b, ITE(1, 0, 1), ITE(0, 0, D) ) ) = (a, C, (b, 0, D) ) CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 27

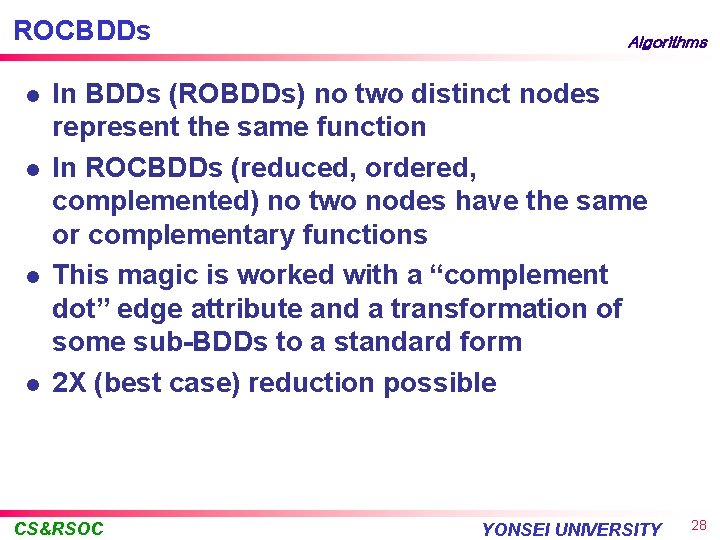

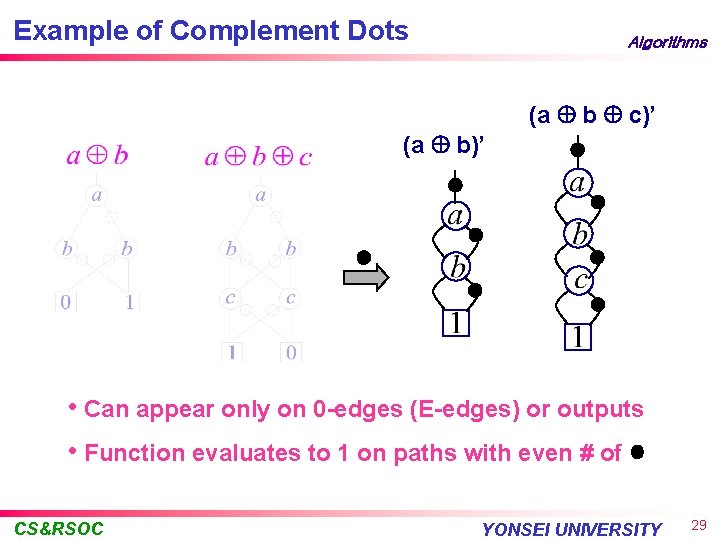

ROCBDDs l l Algorithms In BDDs (ROBDDs) no two distinct nodes represent the same function In ROCBDDs (reduced, ordered, complemented) no two nodes have the same or complementary functions This magic is worked with a “complement dot” edge attribute and a transformation of some sub-BDDs to a standard form 2 X (best case) reduction possible CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 28

Example of Complement Dots Algorithms (a b c)’ (a b)’ • Can appear only on 0 -edges (E-edges) or outputs • Function evaluates to 1 on paths with even # of CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 29

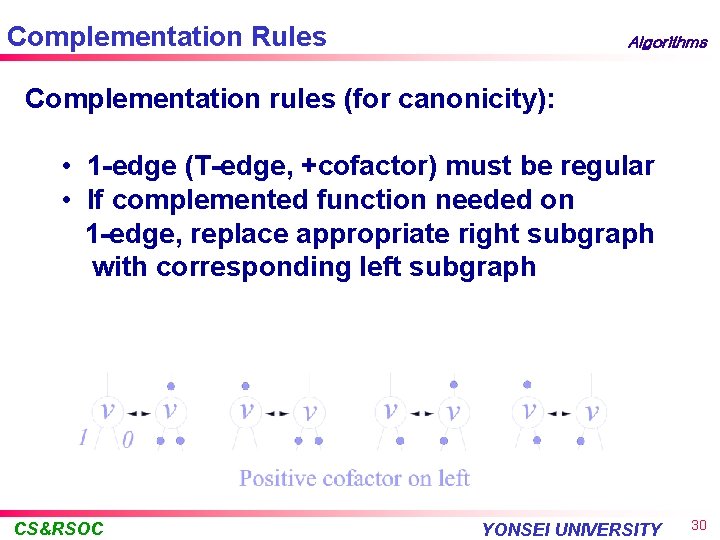

Complementation Rules Algorithms Complementation rules (for canonicity): • 1 -edge (T-edge, +cofactor) must be regular • If complemented function needed on 1 -edge, replace appropriate right subgraph with corresponding left subgraph CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 30

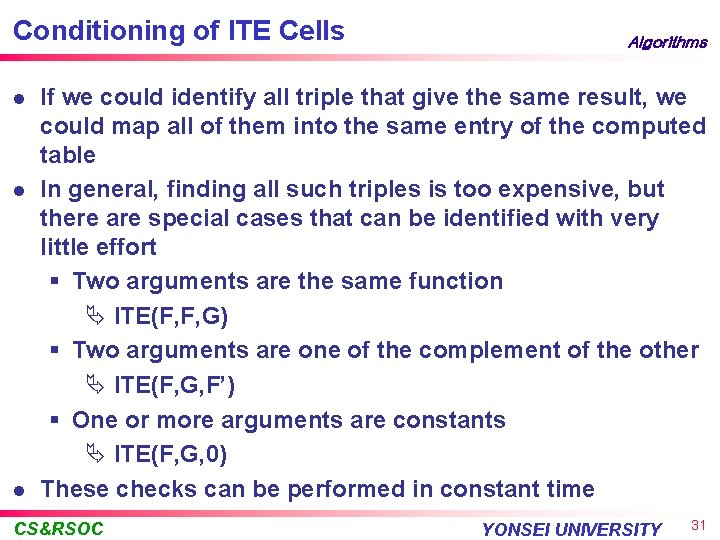

Conditioning of ITE Cells l l l Algorithms If we could identify all triple that give the same result, we could map all of them into the same entry of the computed table In general, finding all such triples is too expensive, but there are special cases that can be identified with very little effort § Two arguments are the same function Ä ITE(F, F, G) § Two arguments are one of the complement of the other Ä ITE(F, G, F’) § One or more arguments are constants Ä ITE(F, G, 0) These checks can be performed in constant time CS&RSOC YONSEI UNIVERSITY 31

- Slides: 31