BEST PRACTICES IN ANTIMICROBIAL STEWARDSHIP Pneumonia Duration of

BEST PRACTICES IN ANTIMICROBIAL STEWARDSHIP: Pneumonia Duration of Therapy and Cdiff Testing Drew Adams, Pharm. D Candidate 2020, Cedarville University Matthew Bauer, DO Zach Jenkins, Pharm. D, BCPS

Compare and Contrast new evidence to the 2007 IDSA CAP guidelines’ recommended on duration of therapy Describe the literature behind the duration of therapy recommendations in the 2016 HAP/VAP guidelines Understand the risks associated with excess therapy Describe the limitations of C Diff testing Understand the HAC reduction program and how frequent C Diff testing can affect reimbursement Implement long-term strategies to aid in appropriate C Diff testing OBJECTIVES

Adequately treat infection Avoid unnecessary adverse drug events (ADEs) Mitigate the emergence of MDROs STEWARDSHIP GOALS

WHY NOW? According to the CDC, pneumonia is the most common reason for inpatient antibiotic use and overuse 1. 7 million ER visits for pneumonia in 2016 Flu season is around the corner Pneumonia National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2016 emergency department summary tables. CDC. 2016.

The 2007 IDSA Guidelines recommend 5 days of antibiotic therapy for CAP… What does more recent literature recommend? COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA (CAP) Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44 Suppl 2: 27.

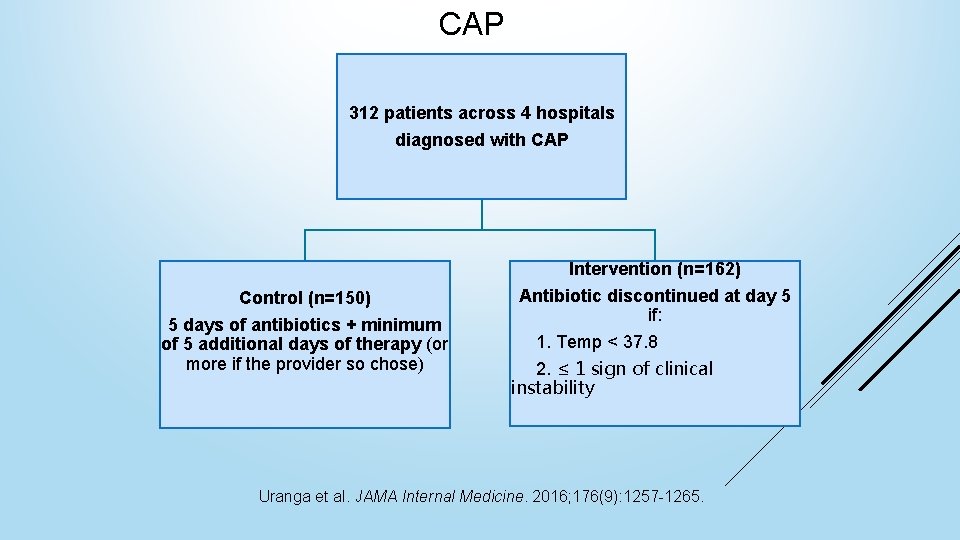

CAP 312 patients across 4 hospitals diagnosed with CAP Intervention (n=162) Control (n=150) 5 days of antibiotics + minimum of 5 additional days of therapy (or more if the provider so chose) Antibiotic discontinued at day 5 if: 1. Temp < 37. 8 2. ≤ 1 sign of clinical instability Uranga et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(9): 1257 -1265.

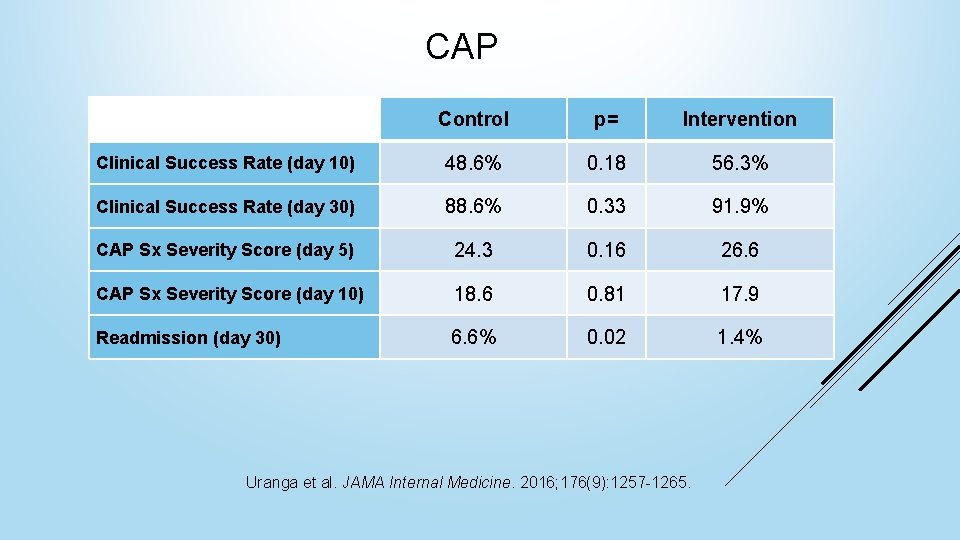

CAP Control p= Intervention Clinical Success Rate (day 10) 48. 6% 0. 18 56. 3% Clinical Success Rate (day 30) 88. 6% 0. 33 91. 9% CAP Sx Severity Score (day 5) 24. 3 0. 16 26. 6 CAP Sx Severity Score (day 10) 18. 6 0. 81 17. 9 Readmission (day 30) 6. 6% 0. 02 1. 4% Uranga et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(9): 1257 -1265.

CAP Takeaways Recent literature supports the 2007 IDSA guideline recommendation of 5 -days of antibiotic therapy for CAP 10+ day duration of therapy for CAP is associated with increased rates of hospital readmission Uranga et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(9): 1257 -1265.

In practice, how often do patients fall into the control group of Uranga et al? And what are the consequences?

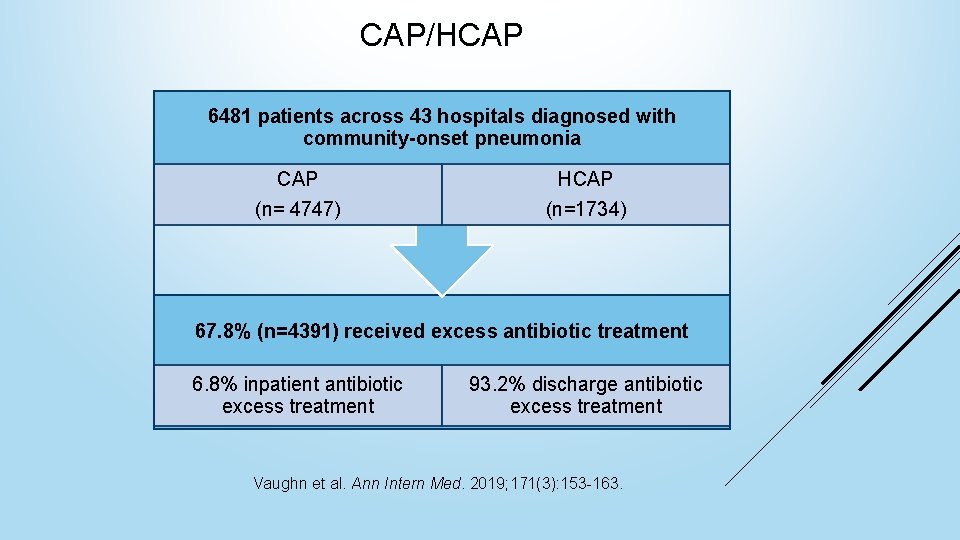

CAP/HCAP 6481 patients across 43 hospitals diagnosed with community-onset pneumonia CAP (n= 4747) HCAP (n=1734) 67. 8% (n=4391) received excess antibiotic treatment 6. 8% inpatient antibiotic excess treatment 93. 2% discharge antibiotic excess treatment Vaughn et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 171(3): 153 -163.

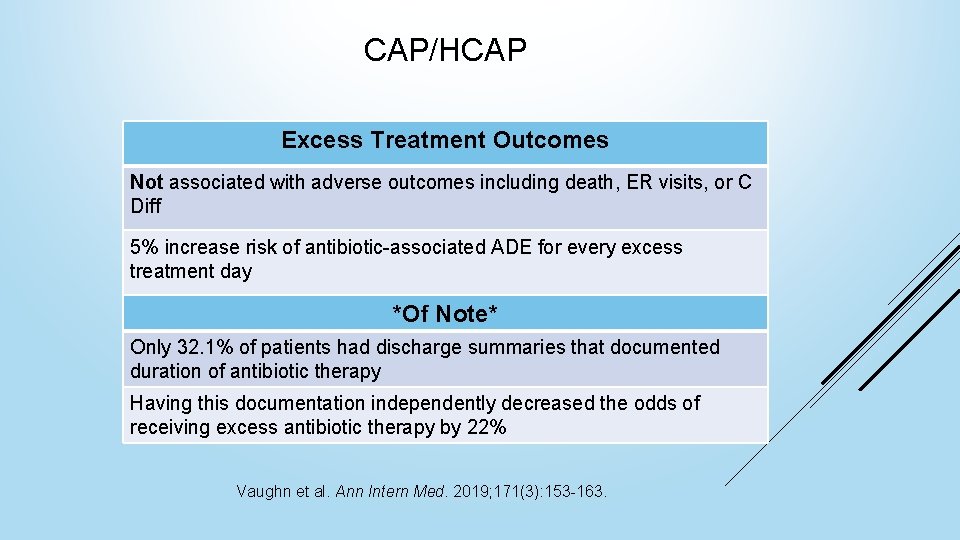

CAP/HCAP Excess Treatment Outcomes Not associated with adverse outcomes including death, ER visits, or C Diff 5% increase risk of antibiotic-associated ADE for every excess treatment day *Of Note* Only 32. 1% of patients had discharge summaries that documented duration of antibiotic therapy Having this documentation independently decreased the odds of receiving excess antibiotic therapy by 22% Vaughn et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 171(3): 153 -163.

CAP/HCAP Takeaways Excess antibiotic days are associated with a linear increase in ADEs Documenting inpatient duration of therapy on discharge summary notes can help reduce excess discharge antibiotics Vaughn et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 171(3): 153 -163.

The 2016 IDSA guidelines recommend 7 days antibiotic therapy for patients with HAP/VAP HOSPITAL/ VENTILATOR-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA (HAP/VAP) Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(5): e 61 -e 111.

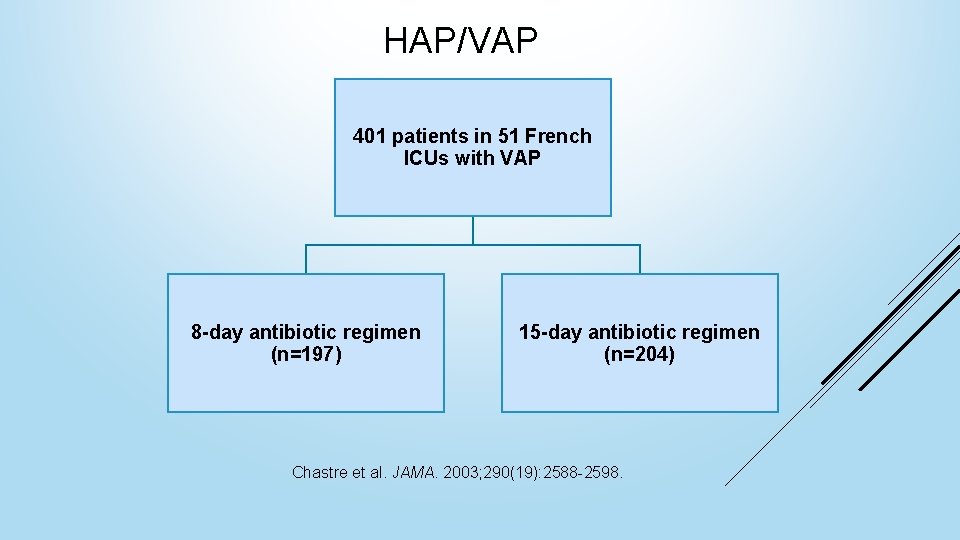

HAP/VAP 401 patients in 51 French ICUs with VAP 8 -day antibiotic regimen (n=197) 15 -day antibiotic regimen (n=204) Chastre et al. JAMA. 2003; 290(19): 2588 -2598.

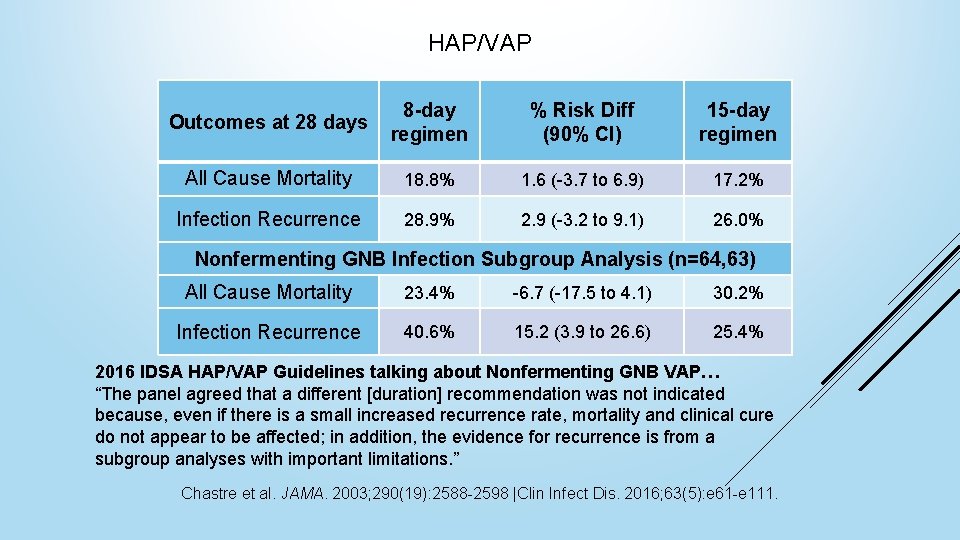

HAP/VAP Outcomes at 28 days 8 -day regimen % Risk Diff (90% CI) 15 -day regimen All Cause Mortality 18. 8% 1. 6 (-3. 7 to 6. 9) 17. 2% Infection Recurrence 28. 9% 2. 9 (-3. 2 to 9. 1) 26. 0% Nonfermenting GNB Infection Subgroup Analysis (n=64, 63) All Cause Mortality 23. 4% -6. 7 (-17. 5 to 4. 1) 30. 2% Infection Recurrence 40. 6% 15. 2 (3. 9 to 26. 6) 25. 4% 2016 IDSA HAP/VAP Guidelines talking about Nonfermenting GNB VAP… “The panel agreed that a different [duration] recommendation was not indicated because, even if there is a small increased recurrence rate, mortality and clinical cure do not appear to be affected; in addition, the evidence for recurrence is from a subgroup analyses with important limitations. ” Chastre et al. JAMA. 2003; 290(19): 2588 -2598 |Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(5): e 61 -e 111.

HAP/VAP Takeaway 7 days of appropriate antibiotic therapy is an adequate duration in patients that respond clinically, even in MDR gram negative VAP Chastre et al. JAMA. 2003; 290(19): 2588 -2598. |Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(5): e 61 -e 11.

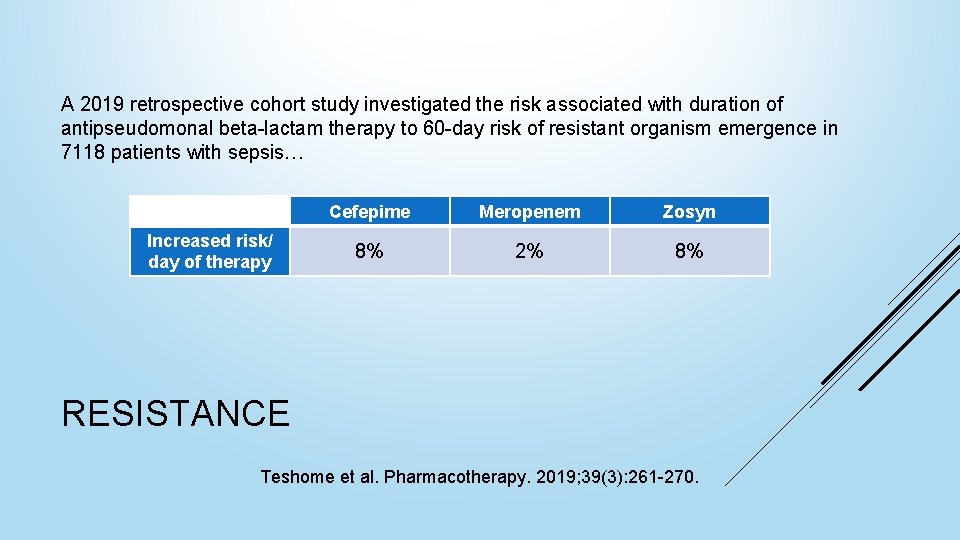

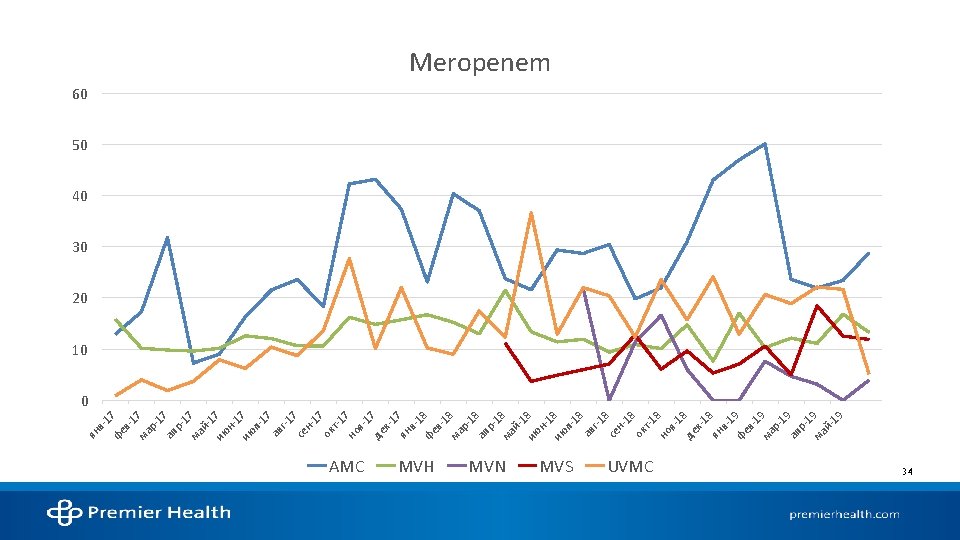

A 2019 retrospective cohort study investigated the risk associated with duration of antipseudomonal beta-lactam therapy to 60 -day risk of resistant organism emergence in 7118 patients with sepsis… Increased risk/ day of therapy Cefepime Meropenem Zosyn 8% 2% 8% RESISTANCE Teshome et al. Pharmacotherapy. 2019; 39(3): 261 -270.

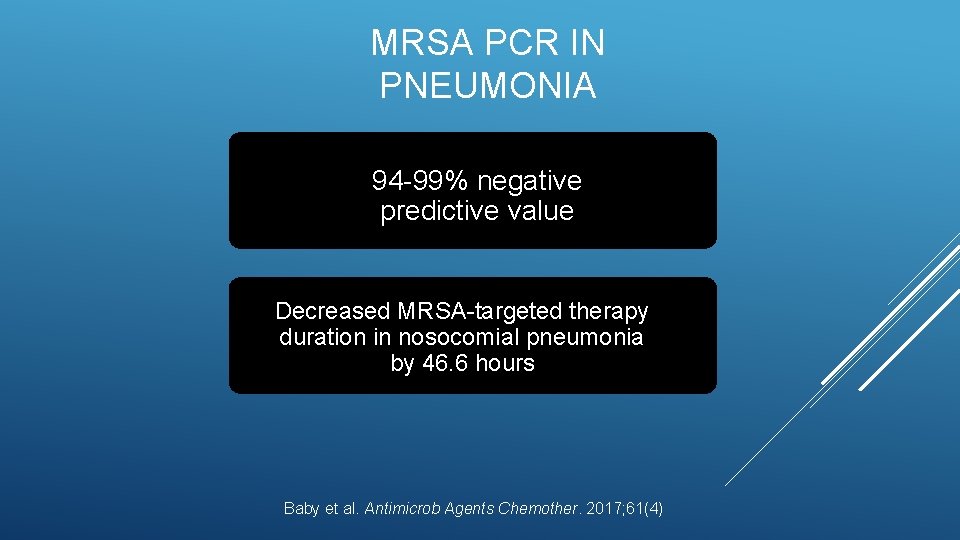

MRSA PCR IN PNEUMONIA 94 -99% negative predictive value Decreased MRSA-targeted therapy duration in nosocomial pneumonia by 46. 6 hours Baby et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017; 61(4)

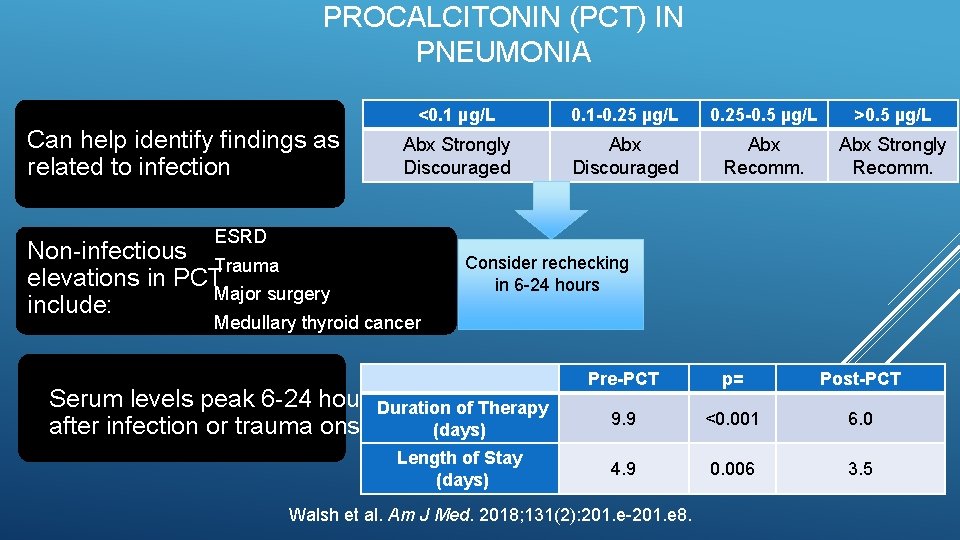

PROCALCITONIN (PCT) IN PNEUMONIA Can help identify findings as related to infection <0. 1 µg/L 0. 1 -0. 25 µg/L 0. 25 -0. 5 µg/L >0. 5 µg/L Abx Strongly Discouraged Abx Recomm. Abx Strongly Recomm. ESRD Non-infectious Trauma elevations in PCT Major surgery include: Consider rechecking in 6 -24 hours Medullary thyroid cancer Serum levels peak 6 -24 hours. Duration of Therapy after infection or trauma onset (days) Length of Stay (days) Pre-PCT p= Post-PCT 9. 9 <0. 001 6. 0 4. 9 0. 006 3. 5 Walsh et al. Am J Med. 2018; 131(2): 201. e-201. e 8.

C DIFF TESTING

WHY NOW? C Diff Testing Hospital-onset C Diff infection (HO-CDI) rates affect reimbursement from CMS AMC’s goal is < 0. 54 hospital-onset MDRO infections per 1, 000 patient-days This past quarter’s increasing HO-CDI rates have brought the YTD score to 0. 74

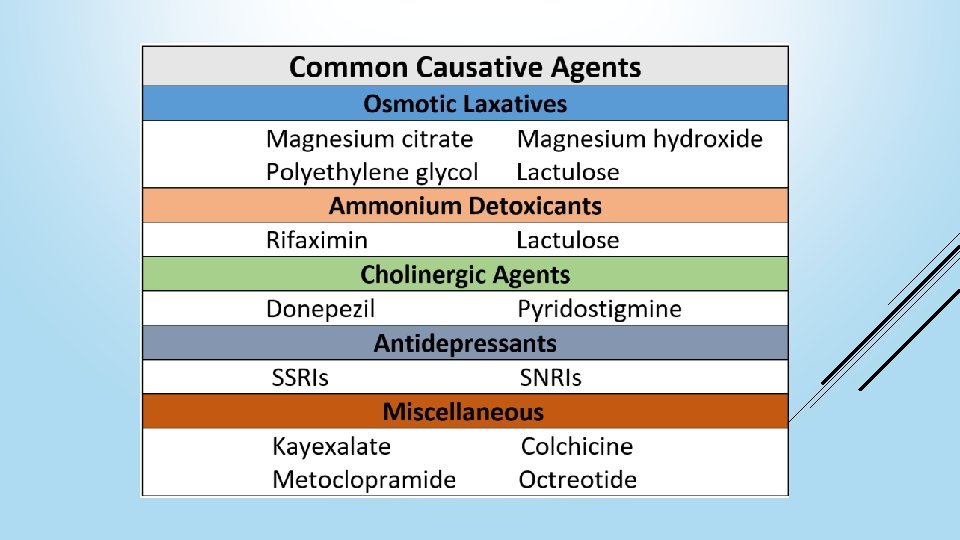

>700 drugs can cause diarrhea and up to 40% of patients on enteral feeding will experience diarrhea 2017 study found that 16. 5% of C Diff tests came back positive when random hospitalroom items were sampled Some studies indicate the positive predictive value (PPV) of C Diff tests are <50% C DIFF TESTING LIMITATIONS 12, 13, 14, 16, 17

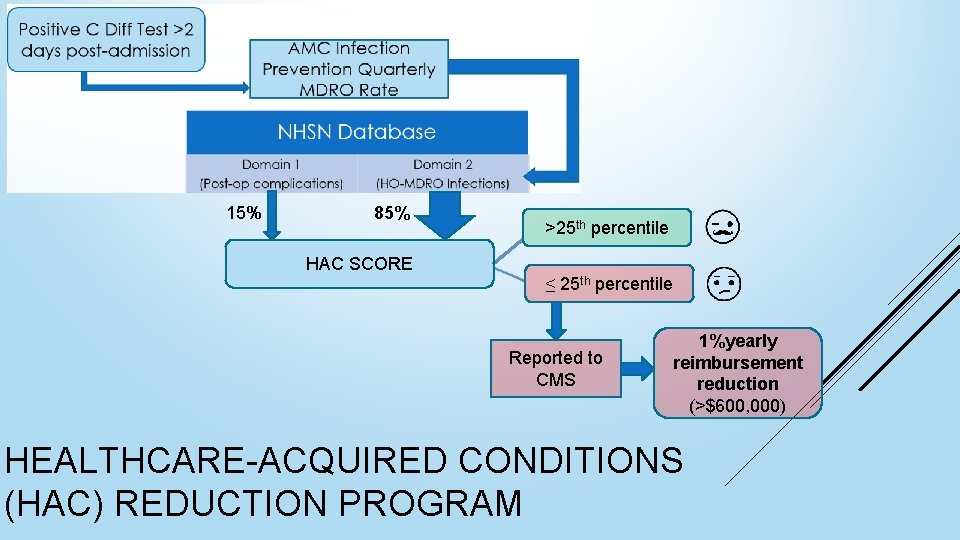

15% 85% HAC SCORE >25 th percentile ≤ 25 th percentile Reported to CMS 1%yearly reimbursement reduction (>$600, 000) HEALTHCARE-ACQUIRED CONDITIONS (HAC) REDUCTION PROGRAM

1. Avoid testing all patients with loose stools for CDI 2. Hold potential diarrhea-causing agents for 24 hours and reassess 3. Test patients who meet the following clinical criteria for CDI Significant diarrhea (>3 watery, loose stools in <24 hours) and any of the following Temp ≥ 38⁰ C WBC > 12, 000/µL New onset abdominal pain or distention Severe diarrhea (>7 bowel movements <24 hours) Persistent diarrhea (significant diarrhea for >24 hours which has not resolved with conservative treatment and does not have another explanation) C DIFF TESTING RECOMMENDATIONS

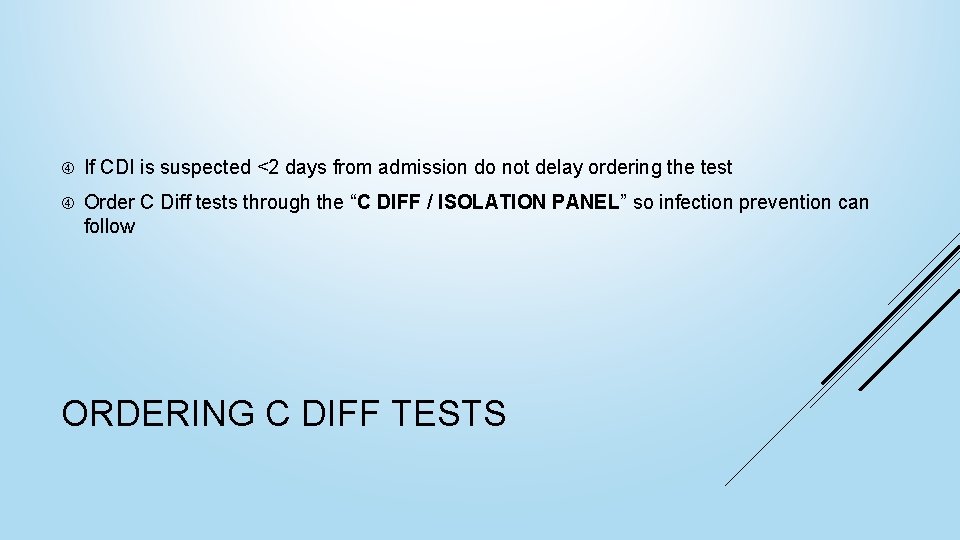

If CDI is suspected <2 days from admission do not delay ordering the test Order C Diff tests through the “C DIFF / ISOLATION PANEL” so infection prevention can follow ORDERING C DIFF TESTS

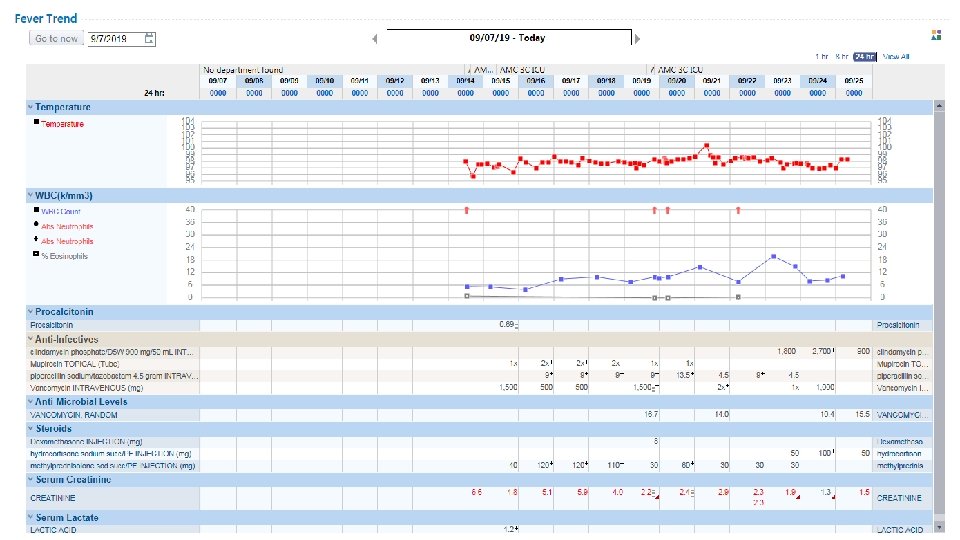

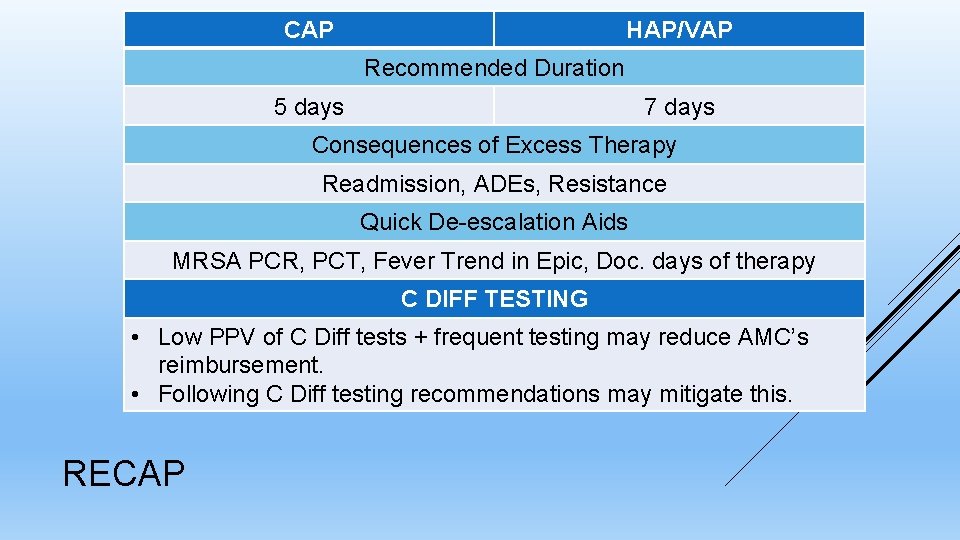

CAP HAP/VAP Recommended Duration 5 days 7 days Consequences of Excess Therapy Readmission, ADEs, Resistance Quick De-escalation Aids MRSA PCR, PCT, Fever Trend in Epic, Doc. days of therapy C DIFF TESTING • Low PPV of C Diff tests + frequent testing may reduce AMC’s reimbursement. • Following C Diff testing recommendations may mitigate this. RECAP

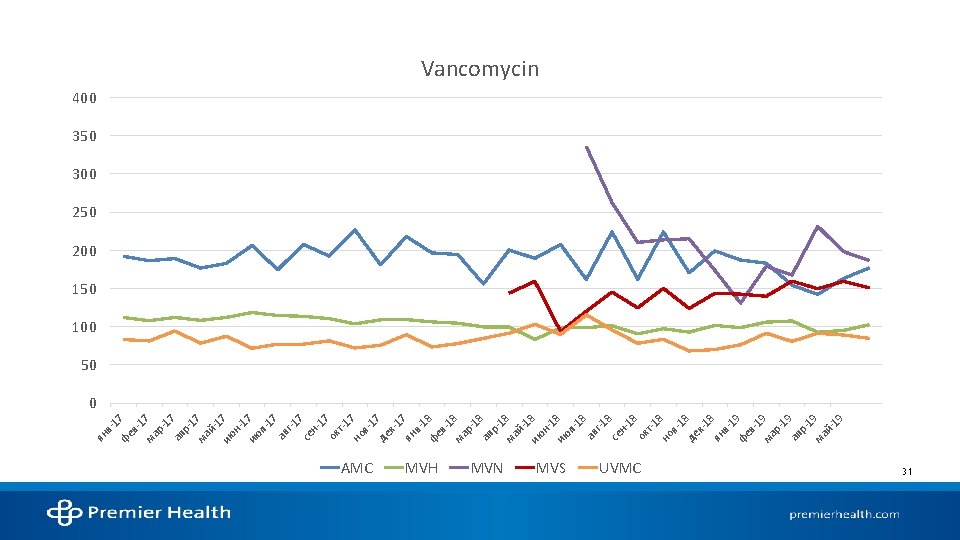

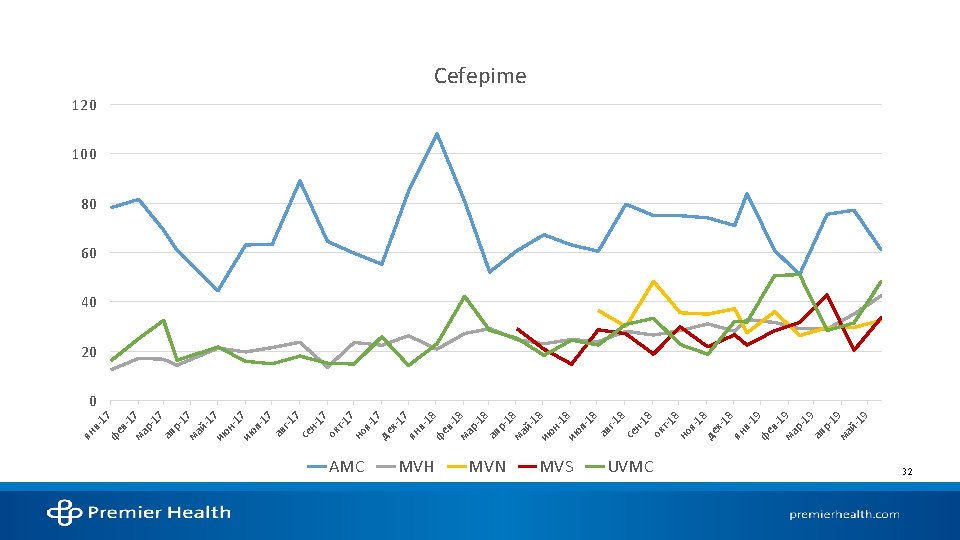

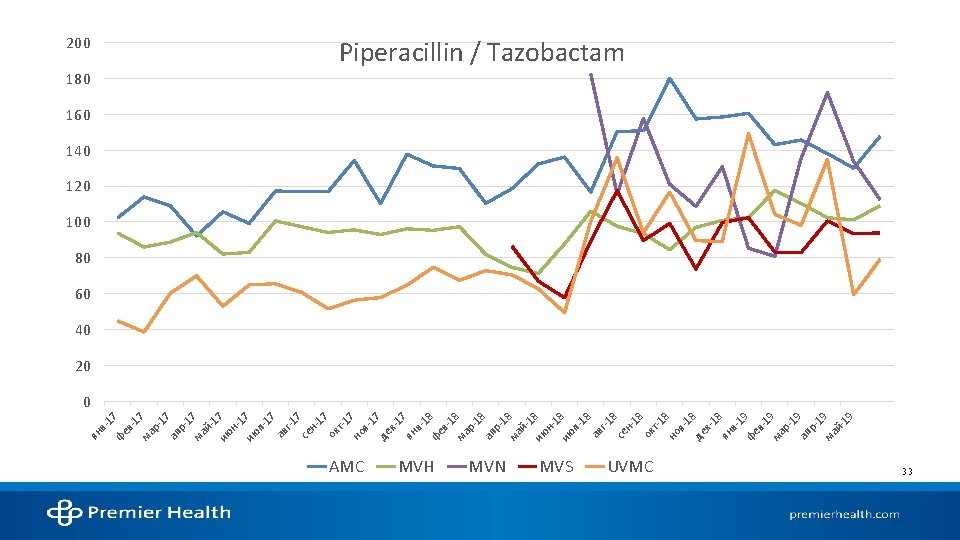

STATE OF ANTIMICROBIAL USE AT AMC

References 1. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america and the american thoracic society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(5): e 61 -e 111. 2. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious diseases society of america/american thoracic society consensus guidelines on the management of communityacquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44 Suppl 2: 27. 3. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2016 emergency department summary tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. 4. Walsh TL, Di. Silvio BE, Hammer C, et al. Impact of procalcitonin guidance with an educational program on management of adults hospitalized with pneumonia. Am J Med. 2018; 131(2): 201. e-201. e 8. 5. Pugh R, Grant C, Cooke RPD, Dempsey G. Short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy for hospital-acquired pneumonia in critically ill adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015(8): CD 007577. 6. Dimopoulos G, Poulakou G, Pneumatikos IA, Armaganidis A, Kollef MH, Matthaiou DK. Short- vs long-duration antibiotic regimens for ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013; 144(6): 1759 -1767. 7. Klompas M. Set a short course but follow the patient's course for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2013; 144(6): 1745 -1747. 8. Chastre J, Wolff M, Fagon J, et al. Comparison of 8 vs 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003; 290(19): 2588 -2598. 9. Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, Snyder A, et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia: A multihospital cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 171(3): 153 -163. 10. Uranga A, España PP, Bilbao A, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment in community-acquired pneumonia: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(9): 1257 -1265. 11. Spellberg B. The new antibiotic Mantra—“Shorter is better”. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(9): 1254 -1255. 12. Mohan SS, Mc. Dermott BP, Parchuri S, Cunha BA. Lack of value of repeat stool testing for clostridium difficile toxin. Am J Med. 2006; 119(4): 356. e-8. 13. Terveer EM, Crobach MJT, Sanders, Ingrid M J G, Vos MC, Verduin CM, Kuijper EJ. Detection of clostridium difficile in feces of asymptomatic patients admitted to the hospital. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2017; 55(2): 403 -411. 14. Mc. Donald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the infectious diseases society of america (IDSA) and society for healthcare epidemiology of america (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 66(7): 987 -994. Accessed Sep 11, 2019. doi: 10. 1093/cid/ciy 149. 15. Napolitano LM, Edmiston CE. Clostridium difficile disease: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment update. Surgery. 2017; 162(2): 325 -348. 16. Christopher R. Polage, Jay V. Solnick, Stuart H. Cohen. Nosocomial diarrhea: Evaluation and treatment of causes other than clostridium difficile. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012; 55(7): 982 -989. 17. Carey-Ann D. Burnham, Karen C. Carroll. Diagnosis of clostridium difficile infection: An ongoing conundrum for clinicians and for clinical laboratories. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2013; 26(3): 604 -630. 18. Alam MJ, Walk ST, Endres BT, et al. Community environmental contamination of toxigenic clostridium difficile. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017; 4(1). 19. Pérez-Topete SE, Miranda-Aquino T, Hernández-Portales JA. Positive predictive value of the immunoassay for clostridium difficile toxin A and B detection at a private hospital. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2016; 81(4): 190 -194.

- Slides: 35