Behavioral niche partitioning reexamined Do behavioral differences predict

Behavioral niche partitioning reexamined Do behavioral differences predict dietary differences? Cody M. Kent and Thomas W. Sherry @cm_kent

Outline §Theory §Behavioral differences §Available prey differences §Dietary differences §Bringing it together §Synthesis and implications @cm_kent

Niche partitioning - theory Popular mechanism to explain coexistence Available prey Mac. Arthur (1958) and others ◦ Morse 1967, 1968, 1974, Pigot et al. 2016 Behavioral filter Realized diet Species that would appear to be competing can coexist by using different resources Applied to a wide range of taxa ◦ Lizards, arthropods, bats, plants Studies often based on proxies of resource use ◦ Behavior, morphology, time, etc. @cm_kent

Niche partitioning - problems Prey can move between microhabitats ◦ Charnov et al. 1976, Holomuzki and Hoyle 1990, Mazia et al. 2006 Different foraging maneuvers can target same prey Different capture rate per foraging attempt ◦ Drenner et al. 1978 @cm_kent

Hypothesis and predictions H: Species differences in foraging behavior correspond with differences in prey types ◦ P 1: Bird species differ in foraging behavior ◦ P 2: Microhabitats differ in available prey ◦ P 3: Bird species differ in prey consumed ◦ P 4: Species differences in expected diets predict differences in observed diets ◦ I. e. , behavioral differences lead to dietary differences @cm_kent

Study system Five species of coexisting Parulid warblers Wintering in two replicate Jamaican wet-limestone forest sites ◦ Structurally complex, native, widespread habitat We know: 1. Species are food-limited in winter dry season ◦ Sherry and Holmes 1996, Sillett et al. 2000, Sherry et al. 2005, Cooper et al. 2015 2. Species compete intraspecifically for food ◦ Holmes et al. 1989, Marra et al. 1993, 2000, 2015 All sampling at peak of dry season (late Feb-March, 2017) @cm_kent

Foraging behavior Searched different part of study site each day Recorded: 1. Maneuver ◦ Sally, sally strike, glean, hover glean, flutter chase 2. Microhabitat ◦ Air space, branch tips, bark, dead leaves 3. Height in canopy ◦ Relative height quartiles (1 -4) Tested for species differences with Bayesian categorical mixed models ◦ Fixed effects: species, age, sex, time, study site, and interactions ◦ Random effects: individual bird @cm_kent

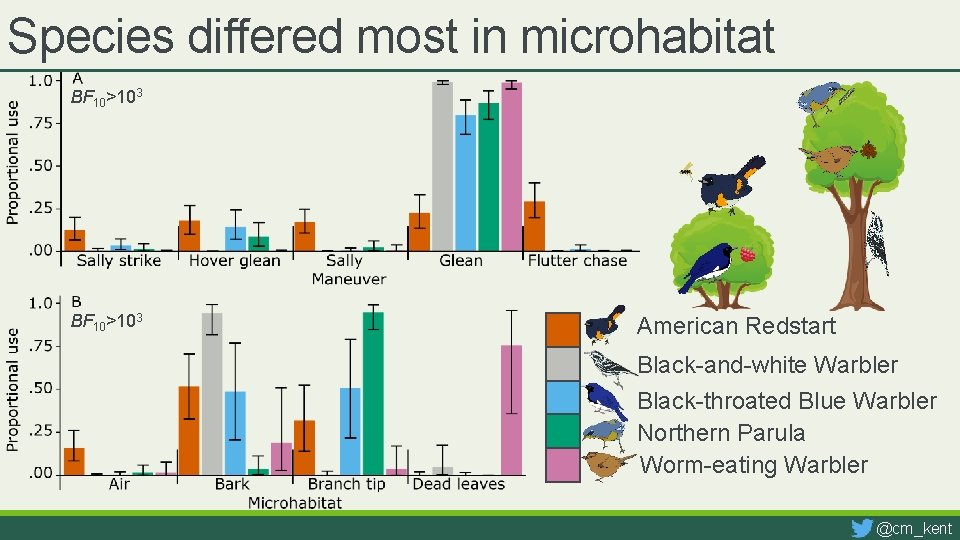

Species differed most in microhabitat BF 10>103 American Redstart Black-and-white Warbler Black-throated Blue Warbler Northern Parula Worm-eating Warbler @cm_kent

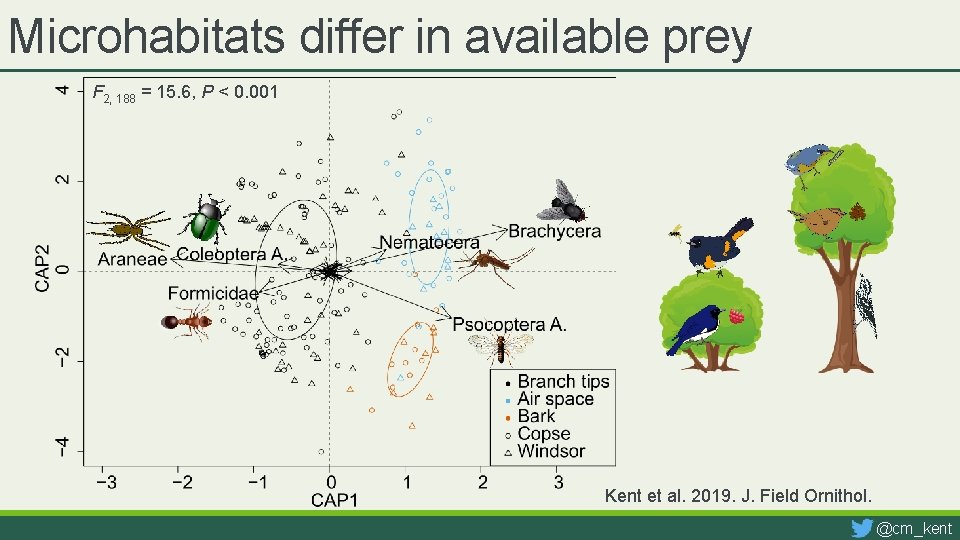

Available prey Sampled from three microhabitats 1. Branch tips- branch clips 2. Bark- collar sticky traps 3. Air space- hanging sticky traps Tested for differences in prey community with db-rda with Bray. Curtis dissimilarity on relative abundance @cm_kent

Microhabitats differ in available prey F 2, 188 = 15. 6, P < 0. 001 Kent et al. 2019. J. Field Ornithol. @cm_kent

Observed diet Birds were captured with mist-nets using playback Used emetic to induce regurgitation Inspected visually for diagnostic insect parts Diets compared using non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMDS) and Pianka’s index @cm_kent

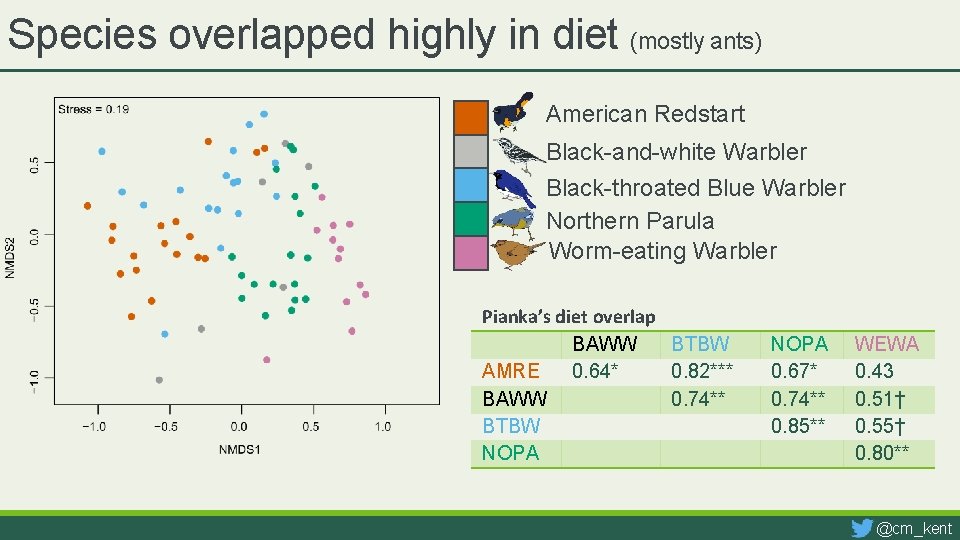

Species overlapped highly in diet (mostly ants) American Redstart Black-and-white Warbler Black-throated Blue Warbler Northern Parula Worm-eating Warbler Pianka’s diet overlap BAWW BTBW AMRE 0. 64* 0. 82*** BAWW 0. 74** BTBW NOPA 0. 67* 0. 74** 0. 85** WEWA 0. 43 0. 51† 0. 55† 0. 80** @cm_kent

@cm_kent

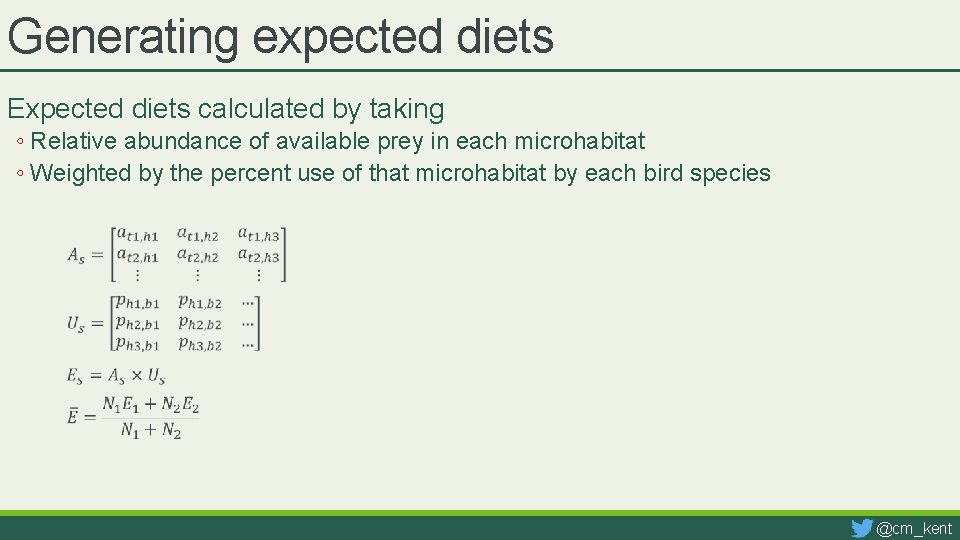

Generating expected diets Expected diets calculated by taking ◦ Relative abundance of available prey in each microhabitat ◦ Weighted by the percent use of that microhabitat by each bird species @cm_kent

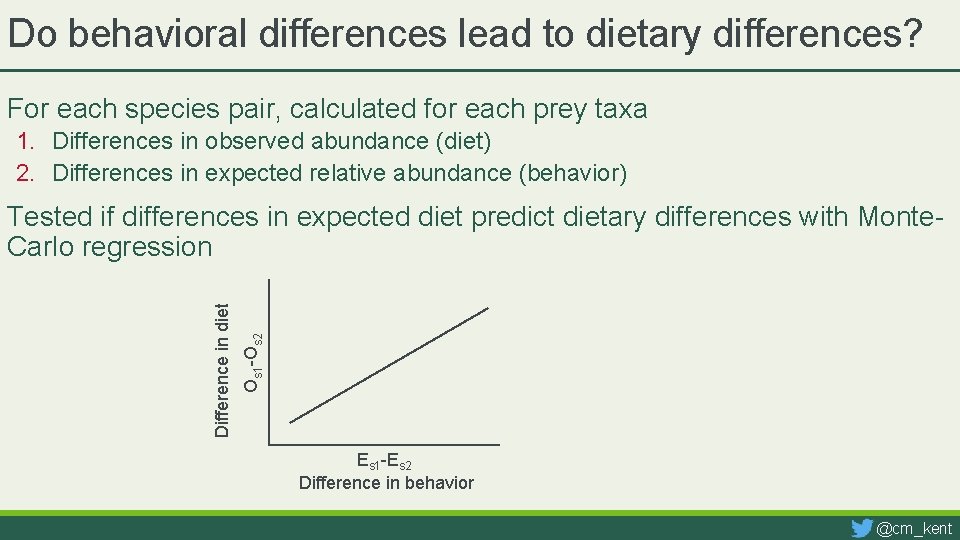

Do behavioral differences lead to dietary differences? For each species pair, calculated for each prey taxa 1. Differences in observed abundance (diet) 2. Differences in expected relative abundance (behavior) Os 1 -Os 2 Difference in diet Tested if differences in expected diet predict dietary differences with Monte. Carlo regression Es 1 -Es 2 Difference in behavior @cm_kent

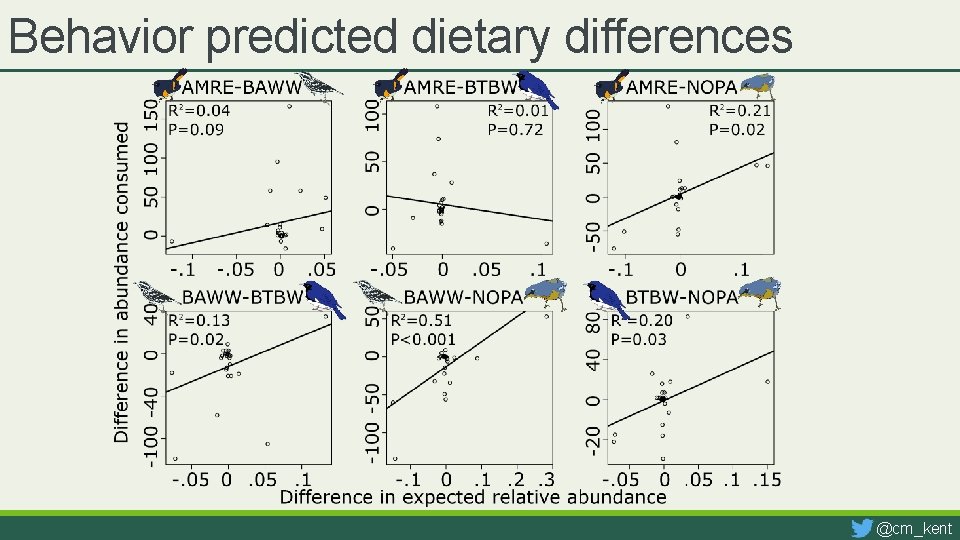

Behavior predicted dietary differences @cm_kent

Conclusions Behavioral differences generally led to dietary differences. However, large differences in behavior led to modest differences in diet. Meaning: 1. Studies based only on foraging behavior potentially underestimate dietary overlap severely 2. In one case, would have generated erroneous results 3. Reconciling incongruity of foraging and diet (resource) differences critical! @cm_kent

Further thoughts How do we reconcile behavioral and dietary differences? Why and how did these behavioral differences evolve? What is the role of these behavioral differences in coexistence? @cm_kent

Acknowledgements Funding Field and lab assistants Jayson Brunner Allen Moss Logistics Molly Fava Kristen Rosamond Artwork Kelli Mc. Kee @cm_kent

Questions? @cm_kent ckent 3@tulane. edu tsherry@tulane. edu @cm_kent

- Slides: 20