Basic principles of advanced hemodynamic monitoring in anesthesia

Basic principles of advanced hemodynamic monitoring in anesthesia and ICU Marta Zawadzka

Why we monitor the cardiovascular system? 1. effects of anesthetics on the cardiovascular system 2. hemodynamic disorders 3. cardiovascular diseases our patients 4. using drugs influencing the cardiovascular system

Monitoring critically ill patients: ●What are we really worried about? “Tissue Hypoperfusion” ●What do we really want to monitor? “Adequate Oxygen Delivery”

Methods of Hemodynamic Monitoring ECG ●Pulse ●Arterial Blood Pressure ● ● ● Non-invasive Direct arterial pressure measurement Central Venous Pressure The Pulmonary Artery Catheter Cardiac Output Measurement Tissue Oxygenation

Clinical monitoring!! Despite the advance in technology, clinical monitoring plays a vital role because the machines used to provide information can fail at some stage. Information provided from the machines should be confirmed by clinical means. It includes extensive monitoring of the anaesthetic machine and equipment, close observation of the patient and the events in the operating theatre. Depth of anaesthesia may be monitored by clinical parameters such as movements, lacrimation, sweating, increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Cardiovascular parameters may be monitored by feeling peripheral pulses, capillary refill and auscultating the heart sounds. Respiratory parameters are monitored by observing chest movements, movement and feel of reservoir bag, auscultating lung fields and by observing the colour of lips and nail beds for cyanosis

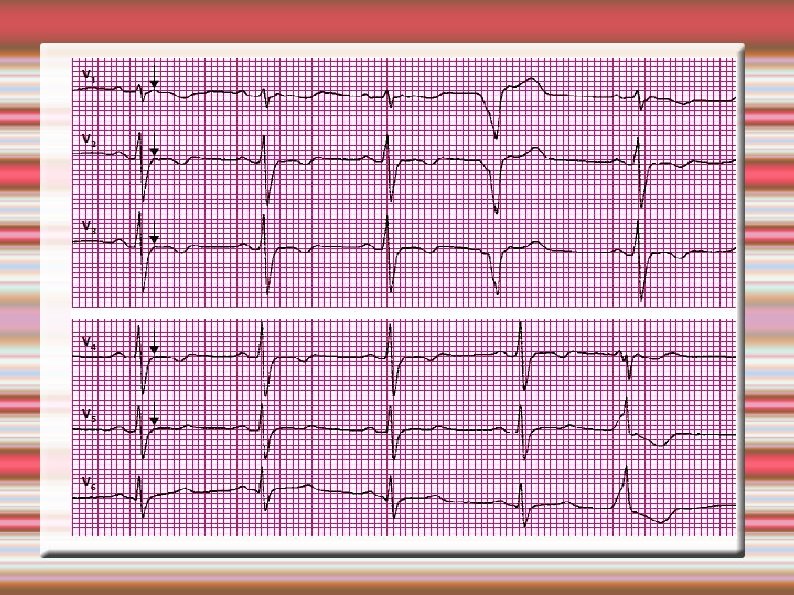

Electrocardiography (ECG) is the process of recording the electrical activity of the heart over a period of time using electrodes placed on a patient's body. These electrodes detect the tiny electrical changes on the skin that arise from the heart muscle depolarizing during each heartbeat.

Noninvasive Hemodynamic Monitoring • Noninvasive BP • Heart Rate, pulses • Mental Status • Mottling (absent) • Skin Temperature • Capillary Refill • Urine Output

Proper Fit of a Blood Pressure Cuff • Width of bladder = 2/3 of upper arm • Length of bladder encircles 80% arm • Lower edge of cuff approximately 2. 5 cm above the antecubital space

Why A Properly Fitting Cuff? • Too small causes false-high reading • Too LARGE causes false-low reading

Automated devices are increasingly used in current clinical practice. The cuff is inflated to a pressure above the expected systolic pressure and then slowly deflated at a rate of 2 -3 mm. Hg per beat. At systolic pressure peripheral pulse appears which can be detected by palpation of radial or brachial artery.

Non-invasive Blood Pressure Measurement ● Manual or automated devices Method of measurement ● ● ● -Oscillometric (most common) MAP most accurate, DP least accurate -Auscultatory (Korotkoff sounds) MAP is calculated -Combination

Disadvantages of non-invasive technique 1. Inaccurate in the presence of arrhythmias. 2. Not possible to have continuous measurement. 3. Not reliable in extremes of BP (underestimates when too high and vice versa). 4. Pressure effects when used for prolonged time and frequent reading resulting in petechiae, nerve palsy.

Arterial monitoring An invasive technique for monitoring arterial blood pressure. Preferred in unstable patients because it is accurate and continuous

The technique of invasive pressure measurement involves placing a cannula in the peripheral artery. Radial, dorsalis pedis, brachial and femoral arteries are commonly used. The system includes a cannula placed in the artery connected to a transducer. In the transducer mechanical energy of movement of diaphragm due to arterial pulsations is converted in to an electrical energy and displayed as blood pressure reading on the monitor. The cannula is continuously flushed with heparinised normal saline to prevent clotting.

Allen's test A test for integrity of the radial and ulnar arteries at the wrist. The examiner compresses the patient's radial and ulnar arteries at the wrist. The patient is then asked to open and close the hand rapidly until the palm appears white. The examiner then releases either the radial or the ulnar artery and looks for return of pink color and circulation to the hand. The test is then repeated releasing the other artery. The hand should return to its pink color within 6 seconds if circulation through that artery is adequate.

Potential Complications Associated With Arterial Lines Hemorrhage Air Emboli Infection Altered Skin Integrity Impaired Circulation

CVP Central venous pressure (CVP), also known as mean venous pressure (MVP) is the pressure of blood in the thoracic vena cava, near the right atrium of the heart. CVP reflects the amount of blood returning to the heart and the ability of the heart to pump the blood into the arterial system.

The factors which affect the CVP are: 1. Systemic vasodilatation and hypovolaemia, which leads to reduced venous return in the vena cava and reduced RAP 2. Right ventricular failure 3. Tricuspid and Pulmonary valve disease 4. Pulmonary hypertension. Right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension leads to raised right atrial pressure, as does tricuspid and pulmonary stenosis.

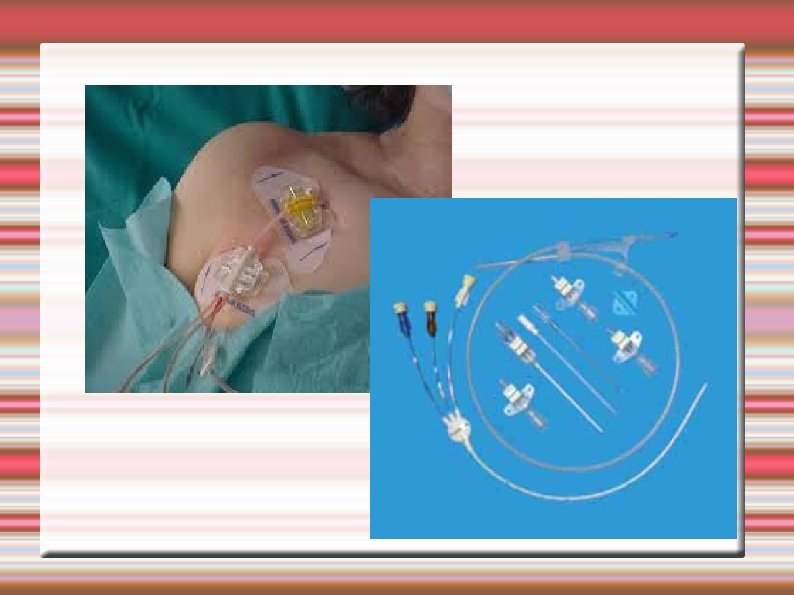

Central venosus line: Indications for CVL: • Severe hypovolaemia requiring rapid infusion (although initial resuscitation may be peripheral through wide bore cannulae) • Infusion of drugs which may cause peripheral problems e. g. vasoconstriction, phlebitis • Measurement of central venous pressure (CVP) • Confirmation of diagnosis e. g. Right heart failure • Insertion of a pacing wire.

Sites for insertion: Internal jugular, subclavian and femoral vein; ‘Long lines’ are also inserted in the brachial vein.

Normal CVP measurements: The normal CVP is between 5 – 10 cm of H 2 O (it increases 3 – 5 cm H 2 O when patient is being ventilated) • In high dependency areas an electronic transducer is connected instead of the manometer system. This gives a continuous readout of CVP along with a display of the waveform. This may be measured in mm. Hg. (Note: 10 cm. H 20 = 7. 5 mm. Hg =1 k. Pa)

Many factors can affect CVP, including vessel tone, medications, heart disease and medical treatments. A CVP measurement should be viewed in conjunction with other observations such as pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate and the patients response to treatment.

Potential complications Haemorrhage from the catheter site - if it becomes disconnected from the infusion. Patients who have coagulation problems such as those on warfarin or those will clotting disorders are at risk. Catheter occlusion, by a blood clot or kinked tube - regular flushing of the CVC line and a well secured dressing should help to avoid this. Infection - redness, pain, swelling around the catheter insertion site may all indicate infection. Air embolus - if the infusion or monitoring lines become disconnected there is a risk that air can enter the venous system. All lines and connections should be checked at the start of every shift to minimise the risk of this occurring. Catheter displacement - if the CVC moves into the chambers of the heart then cardiac arrhythmias may be noted, and should be reported. If the CVC is no longer in the correct position, CVP readings and medication administration will be affected.

Pulmonary Artery Catheter In medicine pulmonary artery catheterization (PAC) is the insertion of a catheter into a pulmonary artery. Its purpose is diagnostic; it is used to detect heart failure or sepsis, monitor therapy, and evaluate the effects of drugs. The pulmonary artery catheter allows direct, simultaneous measurement of pressures in the right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery, and the filling pressure ("wedge" pressure) of the left atrium. The pulmonary artery catheter is frequently referred to as a Swan-Ganz catheter, in honor of its inventors Jeremy Swan and William Ganz

Indications: Management of complicated myocardial infarction Hypovolemia vs cardiogenic shock Ventricular septal rupture (VSR) vs acute mitral regurgitation Severe left ventricular failure Right ventricular infarction Unstable angina Refractory ventricular tachycardia Assessment of respiratory distress Cardiogenic vs non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema Assessment of type of shock Intra-aortic balloon counter-pulsation Assessment of fluid requirement in critically ill patients Hemorrhage Sepsis Management of postoperative open heart surgical patients Assessment of valvular heart disease Assessment of cardiac tamponade/constriction

Complications of Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Complications of central Venous access: Hematoma Bleeding Arterial puncture or cannulation Infection Pneumothorax Hemothorax Arrhythmias: Atrial tachyarrhythmia’s Ventricular tachyarrhythmias Right bundle branch block Complete heart block Catheter-induced injury: Myocardial perforation Valvular injury Pulmonary artery rupture Pulmonary infarction Catheter entrapment on intravascular devices Catheter knotting Thrombosis and embolism Air embolism

Thank you : )

- Slides: 43