Bandwidth estimation in computer networks measurement techniques applications

Bandwidth estimation in computer networks: measurement techniques & applications Constantine Dovrolis College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology

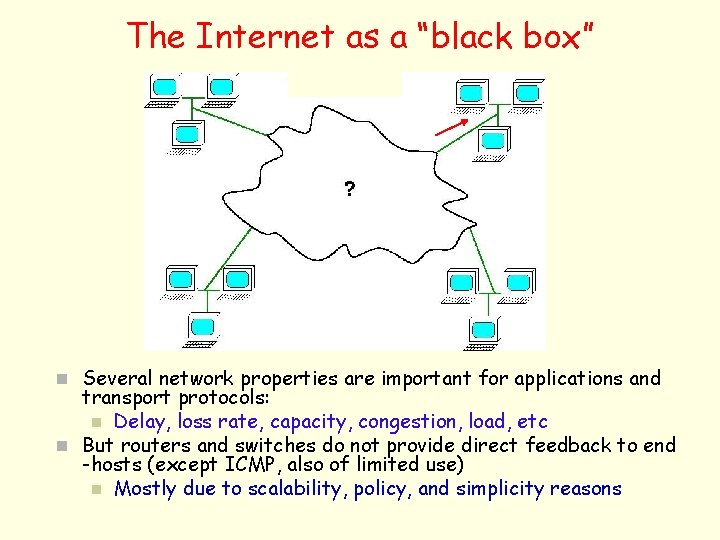

The Internet as a “black box” n Several network properties are important for applications and transport protocols: n Delay, loss rate, capacity, congestion, load, etc n But routers and switches do not provide direct feedback to end -hosts (except ICMP, also of limited use) n Mostly due to scalability, policy, and simplicity reasons

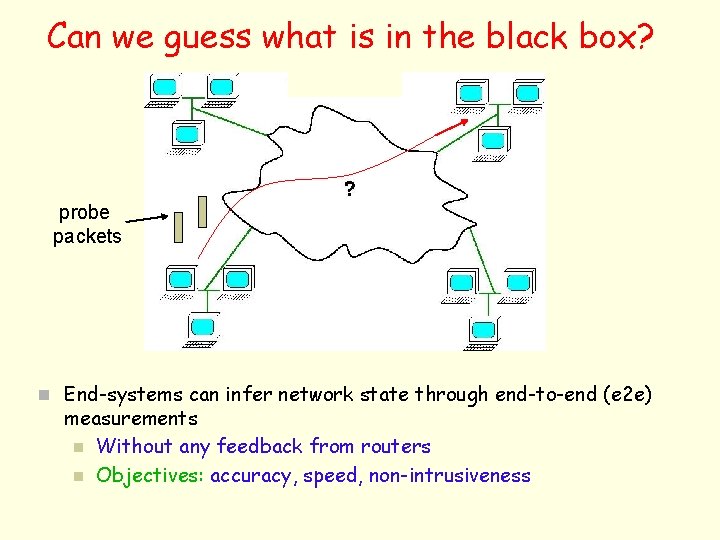

Can we guess what is in the black box? probe packets n End-systems can infer network state through end-to-end (e 2 e) measurements n Without any feedback from routers n Objectives: accuracy, speed, non-intrusiveness

Bandwidth estimation in packet networks n Bandwidth estimation (bwest) area: n Inference of various throughput-related metrics with end-to-end network measurements n Early works: n Keshav’s packet pair method for congestion control (‘ 89) n Bolot’s capacity measurements (’ 93) n Carter-Crovella’s bprobe and cprobe tools (’ 96) n Jacobson’s pathchar - per-hop capacity estimation (‘ 97) n Melander’s TOPP method for avail-bw estimation (’ 00) n In last 3 -5 years: n n n Several fundamentally new estimation techniques Many research papers at prestigious conferences More than a dozen of new measurement tools Several applications of bwest methods Significant commercial interest in bwest technology

Overview n This talk is an overview of the most important developments in bwest area over the last 10 years n A personal bias could not be avoided. . n Overview n Bandwidth-related metrics n Capacity estimation n n Available bandwidth estimation n Packet pairs and Cap. Probe technique Iterative probing: Pathload, Pathvar and Path. Chirp Comparison of tools Applications n SOcket Buffer Auto-Sizing (SOBAS)

Network bandwidth metrics Ravi S. Prasad, Marg Murray, K. C. Claffy, Constantine Dovrolis, “Bandwidth Estimation: Metrics, Measurement Techniques, and Tools, ” IEEE Network, November/December 2003.

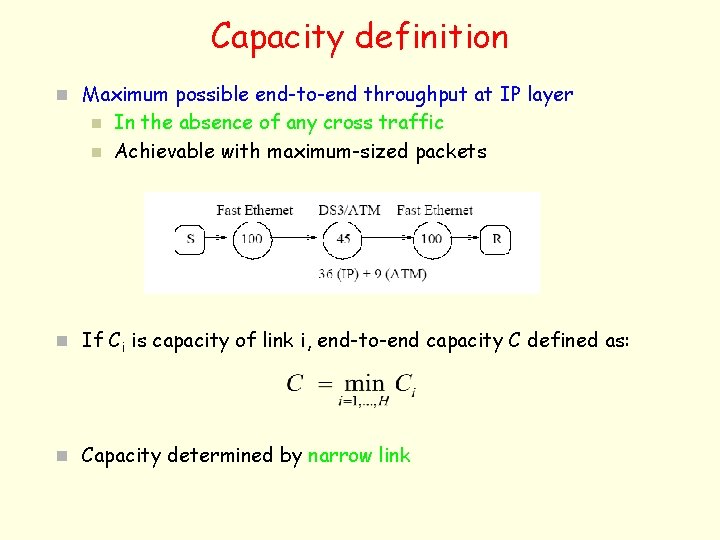

Capacity definition n Maximum possible end-to-end throughput at IP layer n n In the absence of any cross traffic Achievable with maximum-sized packets n If Ci is capacity of link i, end-to-end capacity C defined as: n Capacity determined by narrow link

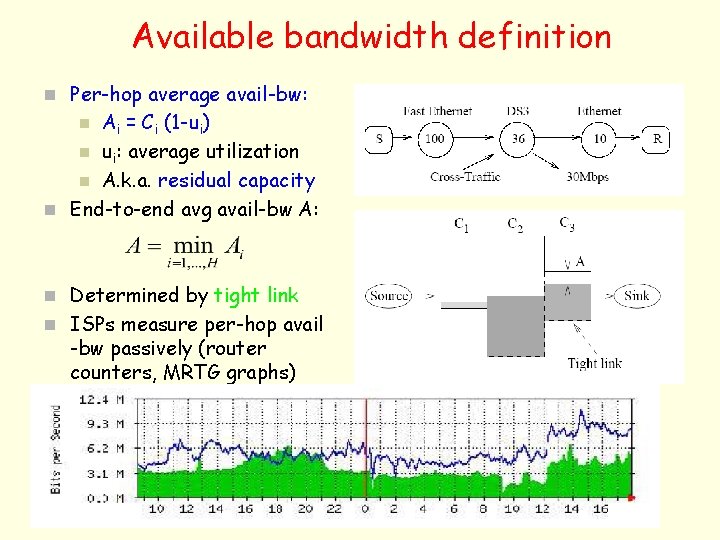

Available bandwidth definition n Per-hop average avail-bw: Ai = Ci (1 -ui) n ui: average utilization n A. k. a. residual capacity n End-to-end avg avail-bw A: n n Determined by tight link n ISPs measure per-hop avail -bw passively (router counters, MRTG graphs)

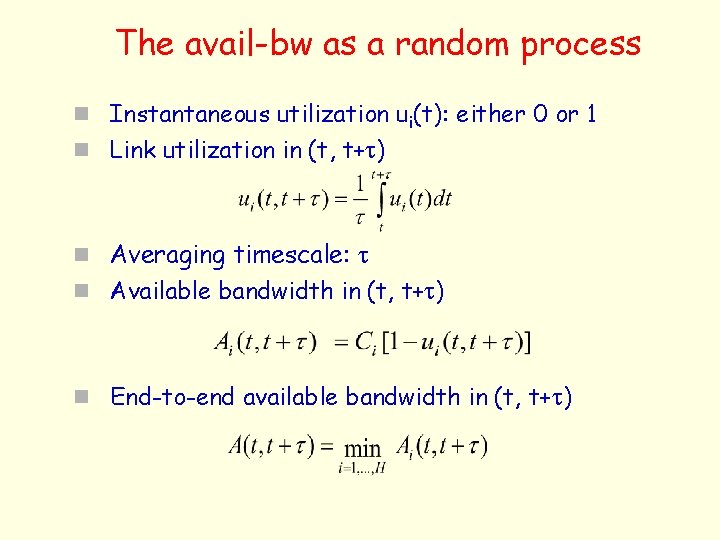

The avail-bw as a random process n Instantaneous utilization ui(t): either 0 or 1 n Link utilization in (t, t+t) n Averaging timescale: t n Available bandwidth in (t, t+t) n End-to-end available bandwidth in (t, t+t)

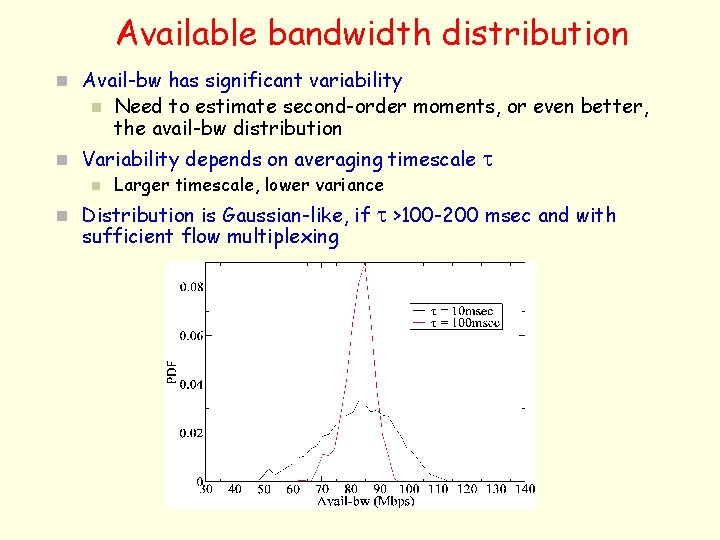

Available bandwidth distribution n Avail-bw has significant variability n Need to estimate second-order moments, or even better, the avail-bw distribution n Variability depends on averaging timescale n Larger timescale, lower variance n Distribution is Gaussian-like, if sufficient flow multiplexing t t >100 -200 msec and with

E 2 E Capacity estimation (a’): Packet pair technique Constantine Dovrolis, Parmesh Ramanathan, David Moore, “Packet Dispersion Techniques and Capacity Estimation, ” In IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, Dec 2004.

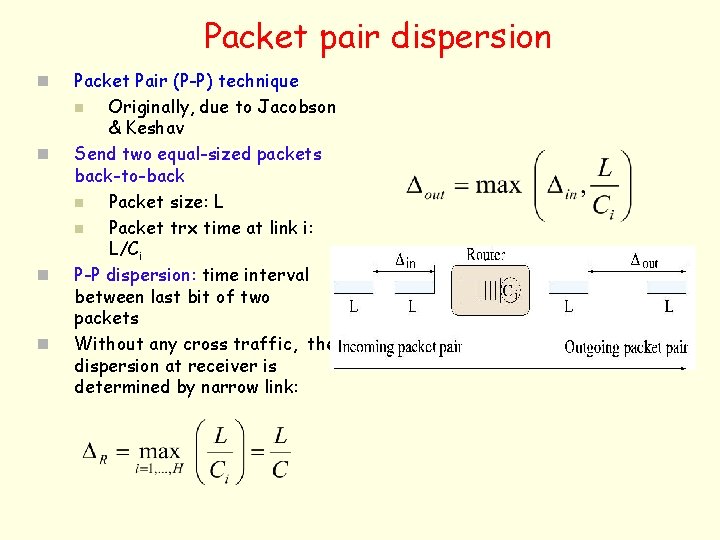

Packet pair dispersion n n Packet Pair (P-P) technique n Originally, due to Jacobson & Keshav Send two equal-sized packets back-to-back n Packet size: L n Packet trx time at link i: L/Ci P-P dispersion: time interval between last bit of two packets Without any cross traffic, the dispersion at receiver is determined by narrow link:

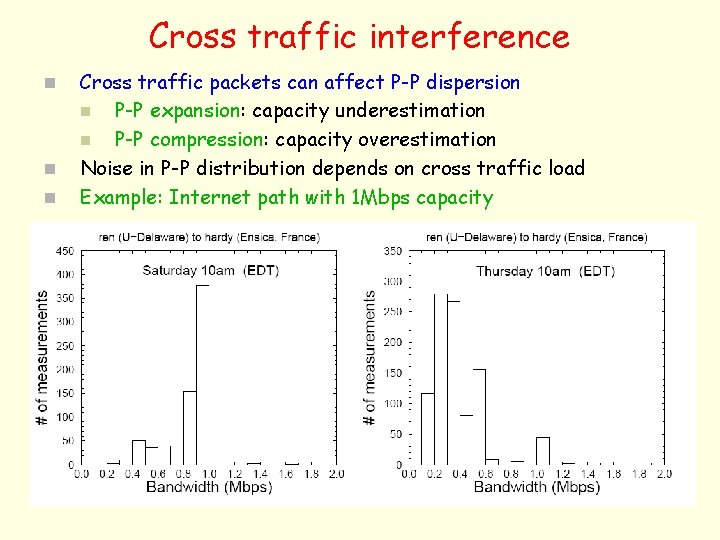

Cross traffic interference n n n Cross traffic packets can affect P-P dispersion n P-P expansion: capacity underestimation n P-P compression: capacity overestimation Noise in P-P distribution depends on cross traffic load Example: Internet path with 1 Mbps capacity

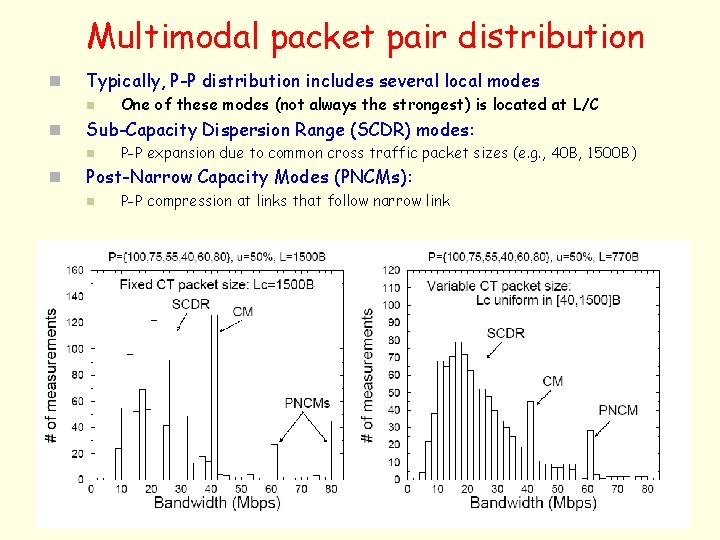

Multimodal packet pair distribution n Typically, P-P distribution includes several local modes n n Sub-Capacity Dispersion Range (SCDR) modes: n n One of these modes (not always the strongest) is located at L/C P-P expansion due to common cross traffic packet sizes (e. g. , 40 B, 1500 B) Post-Narrow Capacity Modes (PNCMs): n P-P compression at links that follow narrow link

E 2 E Capacity estimation (b’): Cap. Probe Rohit Kapoor, Ling-Jyh Chen, Li Lao, Mario Gerla, M. Y. Sanadidi, "Cap. Probe: A Simple and Accurate Capacity Estimation Technique, " ACM SIGCOMM 2004

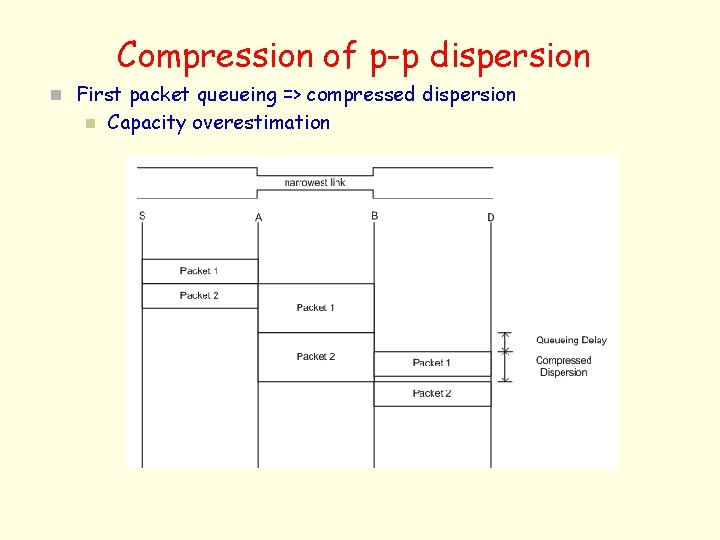

Compression of p-p dispersion n First packet queueing => compressed dispersion n Capacity overestimation

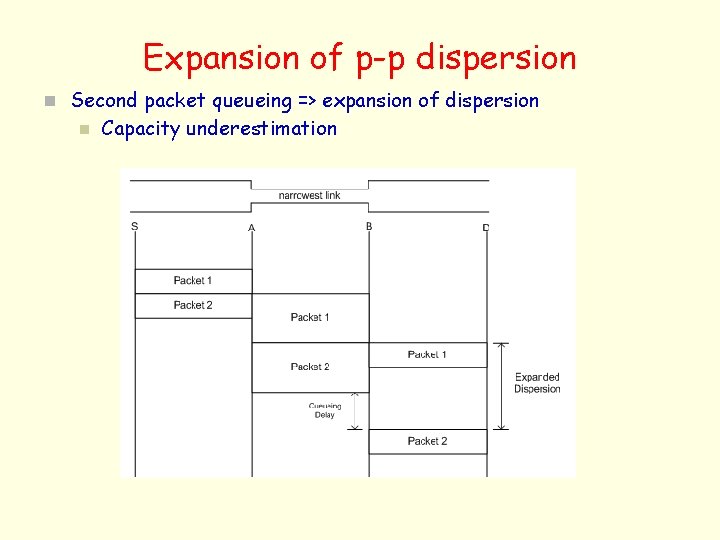

Expansion of p-p dispersion n Second packet queueing => expansion of dispersion n Capacity underestimation

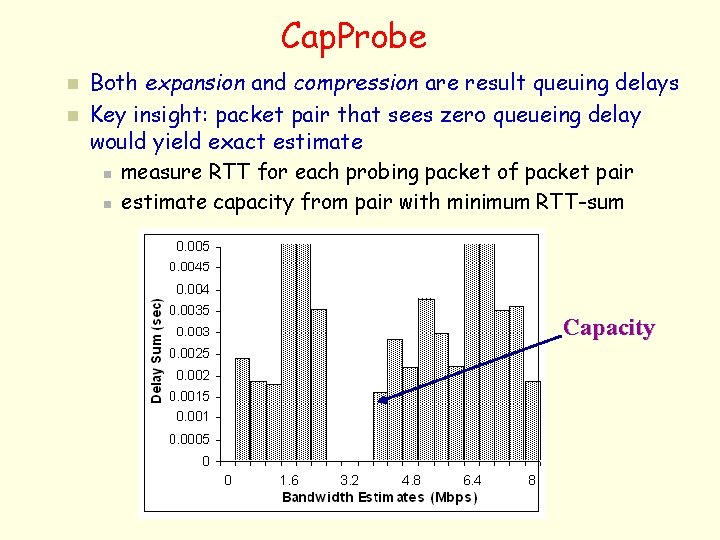

Cap. Probe n n Both expansion and compression are result queuing delays Key insight: packet pair that sees zero queueing delay would yield exact estimate n measure RTT for each probing packet of packet pair n estimate capacity from pair with minimum RTT-sum Capacity

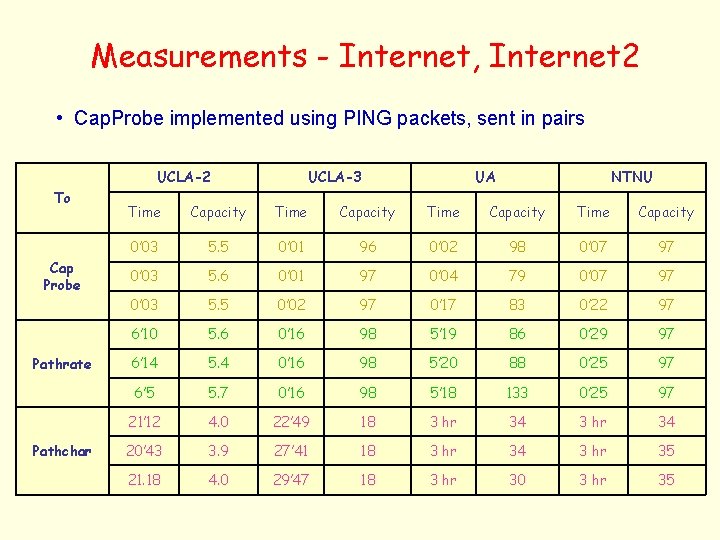

Measurements - Internet, Internet 2 • Cap. Probe implemented using PING packets, sent in pairs UCLA-2 To Cap Probe Pathrate Pathchar UCLA-3 UA NTNU Time Capacity 0’ 03 5. 5 0’ 01 96 0’ 02 98 0’ 07 97 0’ 03 5. 6 0’ 01 97 0’ 04 79 0’ 07 97 0’ 03 5. 5 0’ 02 97 0’ 17 83 0’ 22 97 6’ 10 5. 6 0’ 16 98 5’ 19 86 0’ 29 97 6’ 14 5. 4 0’ 16 98 5’ 20 88 0’ 25 97 6’ 5 5. 7 0’ 16 98 5’ 18 133 0’ 25 97 21’ 12 4. 0 22’ 49 18 3 hr 34 20’ 43 3. 9 27’ 41 18 3 hr 34 3 hr 35 21. 18 4. 0 29’ 47 18 3 hr 30 3 hr 35

Avail-bw estimation (a’): Pathload Manish Jain, Constantine Dovrolis, “End-to-End Available Bandwidth: Measurement Methodology, Dynamics, and Relation with TCP Throughput, ” IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, Aug 2003.

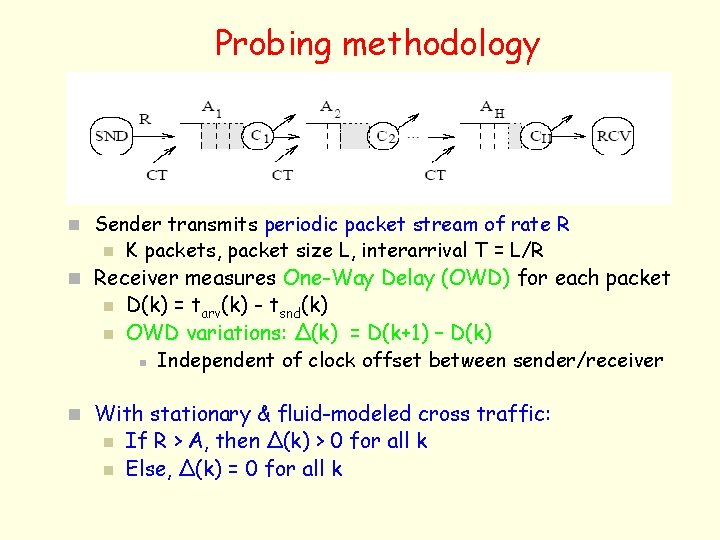

Probing methodology n Sender transmits periodic packet stream of rate R n K packets, packet size L, interarrival T = L/R n Receiver measures One-Way Delay (OWD) for each packet n n D(k) = tarv(k) - tsnd(k) OWD variations: Δ(k) = D(k+1) – D(k) n Independent of clock offset between sender/receiver n With stationary & fluid-modeled cross traffic: n n If R > A, then Δ(k) > 0 for all k Else, Δ(k) = 0 for all k

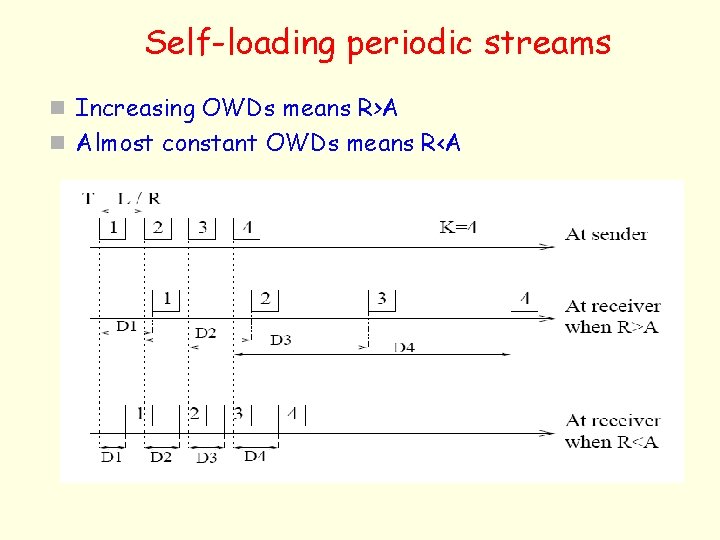

Self-loading periodic streams n Increasing OWDs means R>A n Almost constant OWDs means R<A

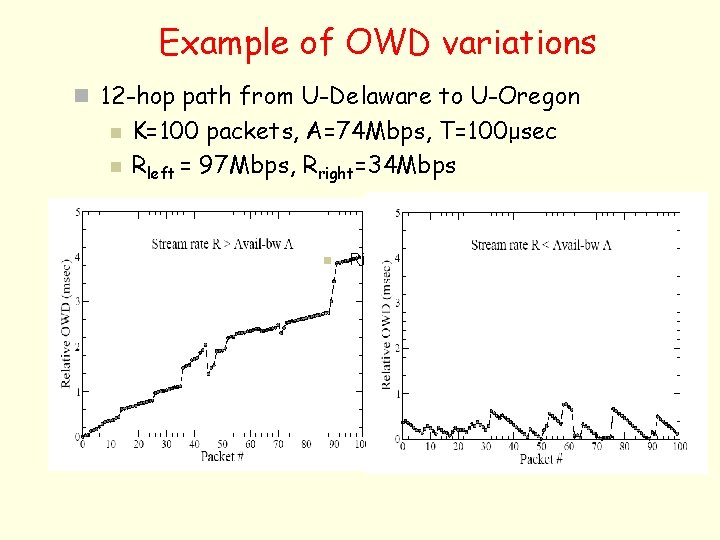

Example of OWD variations n 12 -hop path from U-Delaware to U-Oregon n n K=100 packets, A=74 Mbps, T=100μsec Rleft = 97 Mbps, Rright=34 Mbps n Ri

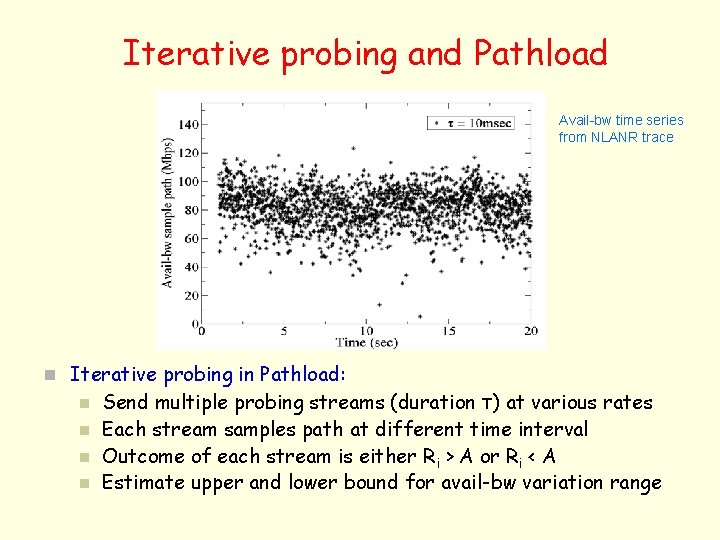

Iterative probing and Pathload Avail-bw time series from NLANR trace n Iterative probing in Pathload: n n Send multiple probing streams (duration τ) at various rates Each stream samples path at different time interval Outcome of each stream is either Ri > A or Ri < A Estimate upper and lower bound for avail-bw variation range

Avail-bw estimation (b’): percentile estimation Manish Jain, Constantine Dovrolis, “End-to-End Estimation of the Available Bandwidth Variation Range, ” ACM SIGMETRICS 2005

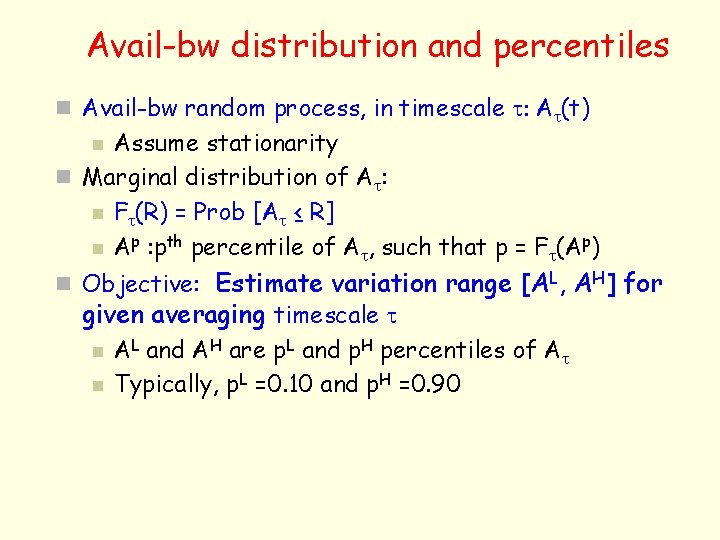

Avail-bw distribution and percentiles n Avail-bw random process, in timescale t: At(t) Assume stationarity n Marginal distribution of At: n Ft(R) = Prob [At ≤ R] n Ap : pth percentile of At, such that p = Ft(Ap) n n Objective: Estimate variation range [AL, AH] for given averaging timescale t n n AL and AH are p. L and p. H percentiles of At Typically, p. L =0. 10 and p. H =0. 90

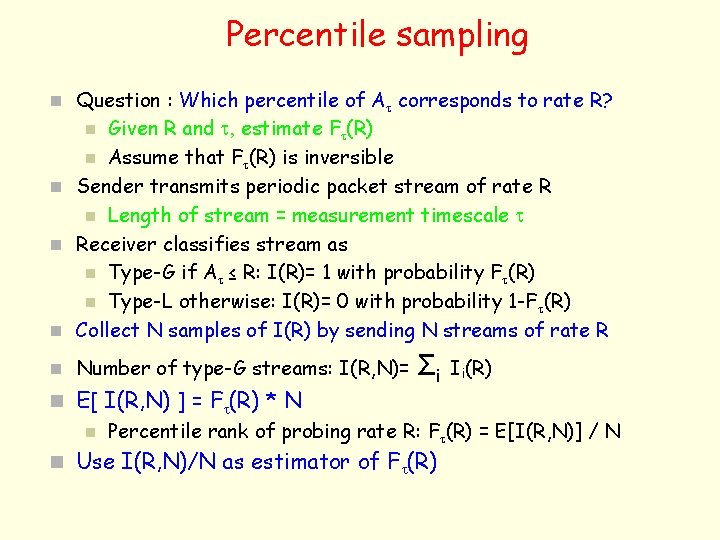

Percentile sampling n Question : Which percentile of At corresponds to rate R? Given R and t, estimate Ft(R) n Assume that Ft(R) is inversible n Sender transmits periodic packet stream of rate R n Length of stream = measurement timescale t n Receiver classifies stream as n Type-G if At ≤ R: I(R)= 1 with probability Ft(R) n Type-L otherwise: I(R)= 0 with probability 1 -F t(R) n Collect N samples of I(R) by sending N streams of rate R n n Number of type-G streams: I(R, N)= Σi Ii(R) n E[ I(R, N) ] = Ft(R) * N n Percentile rank of probing rate R: Ft(R) = E[I(R, N)] / N n Use I(R, N)/N as estimator of Ft(R)

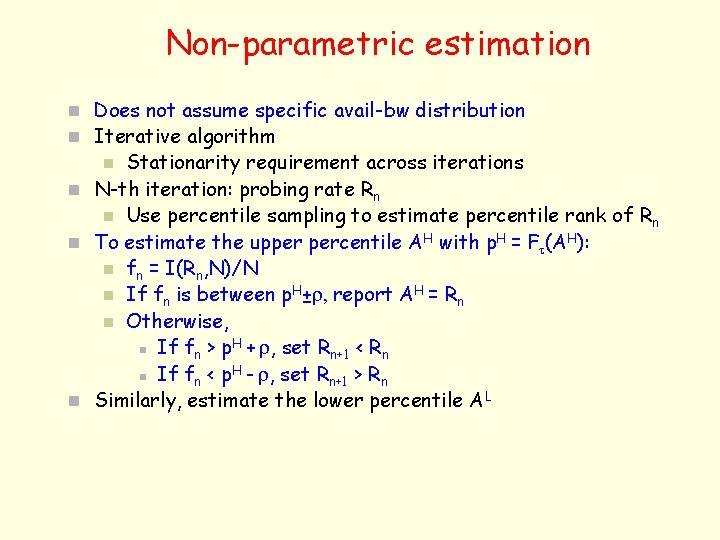

Non-parametric estimation n Does not assume specific avail-bw distribution n Iterative algorithm Stationarity requirement across iterations n N-th iteration: probing rate Rn n Use percentile sampling to estimate percentile rank of Rn n To estimate the upper percentile AH with p. H = Ft(AH): n fn = I(Rn, N)/N n If fn is between p. H±r, report AH = Rn n Otherwise, H n If fn > p + r, set Rn+1 < Rn H n If fn < p - r, set Rn+1 > Rn n Similarly, estimate the lower percentile AL n

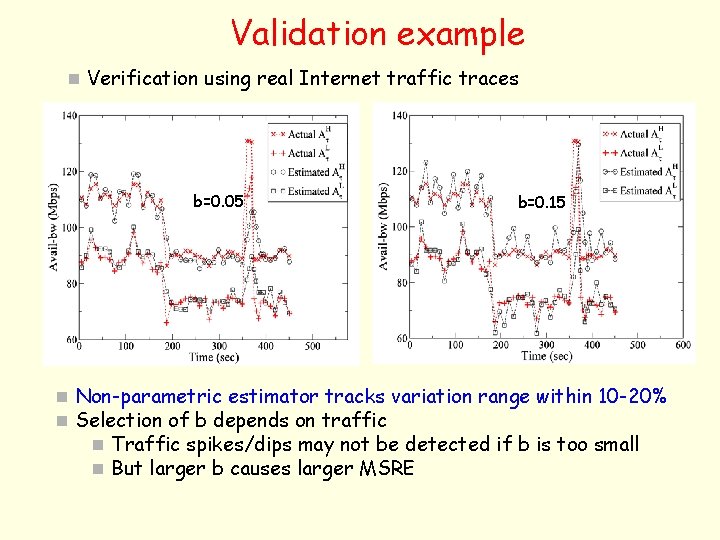

Validation example n Verification using real Internet traffic traces b=0. 05 b=0. 15 n Non-parametric estimator tracks variation range within 10 -20% n Selection of b depends on traffic n Traffic spikes/dips may not be detected if b is too small n But larger b causes larger MSRE

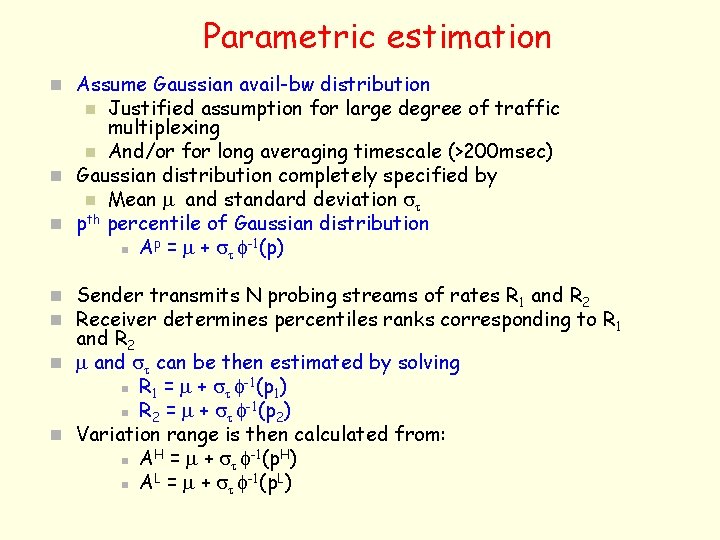

Parametric estimation n Assume Gaussian avail-bw distribution Justified assumption for large degree of traffic multiplexing n And/or for long averaging timescale (>200 msec) n Gaussian distribution completely specified by n Mean m and standard deviation st n pth percentile of Gaussian distribution p -1 n A = m + st f (p) n n Sender transmits N probing streams of rates R 1 and R 2 n Receiver determines percentiles ranks corresponding to R 1 and R 2 n m and st can be then estimated by solving -1 n R 1 = m + st f (p 1) -1 n R 2 = m + st f (p 2) n Variation range is then calculated from: H -1 H n A = m + st f (p ) L -1 L n A = m + st f (p )

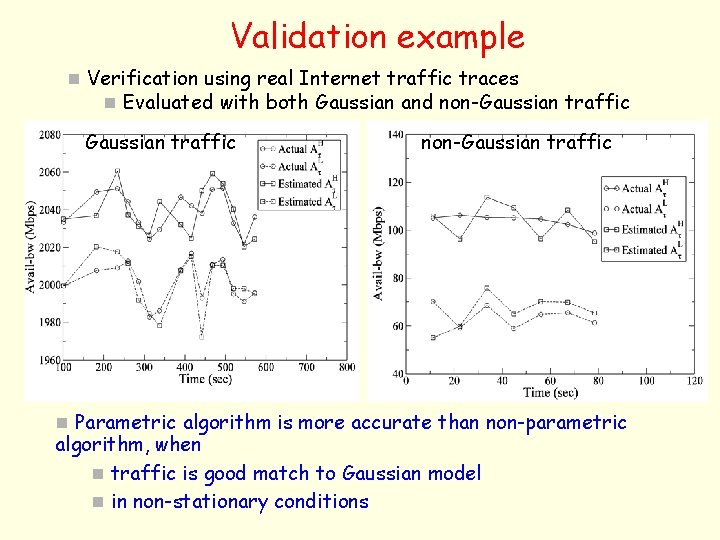

Validation example n Verification using real Internet traffic traces n Evaluated with both Gaussian and non-Gaussian traffic n Parametric algorithm is more accurate than non-parametric algorithm, when n traffic is good match to Gaussian model n in non-stationary conditions

Avail-bw estimation (c’): Path. Chirp Vinay Ribeiro, Rolf Riedi, Jiri Navratil, Rich Baraniuk, Les Cottrell, “Path. Chirp: Efficient Available Bandwidth Estimation, ” PAM 2003

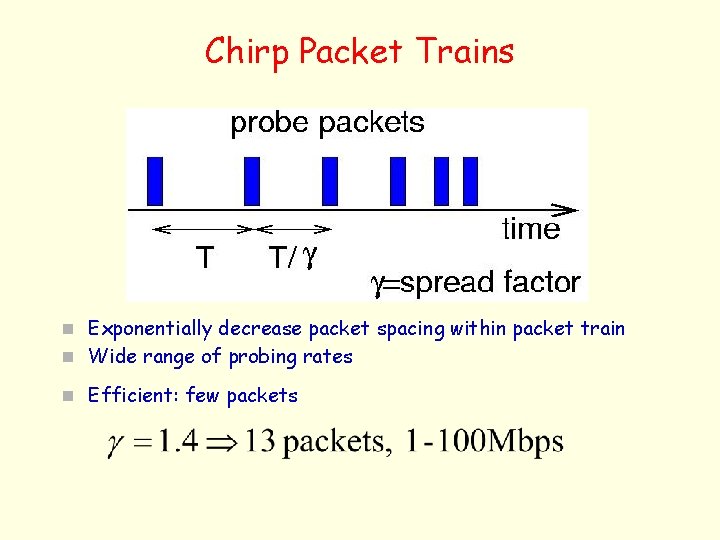

Chirp Packet Trains n Exponentially decrease packet spacing within packet train n Wide range of probing rates n Efficient: few packets

Chirps vs. CBR Trains n Multiple rates in each chirping train n Allows one estimate per-chirp n Potentially more efficient estimation

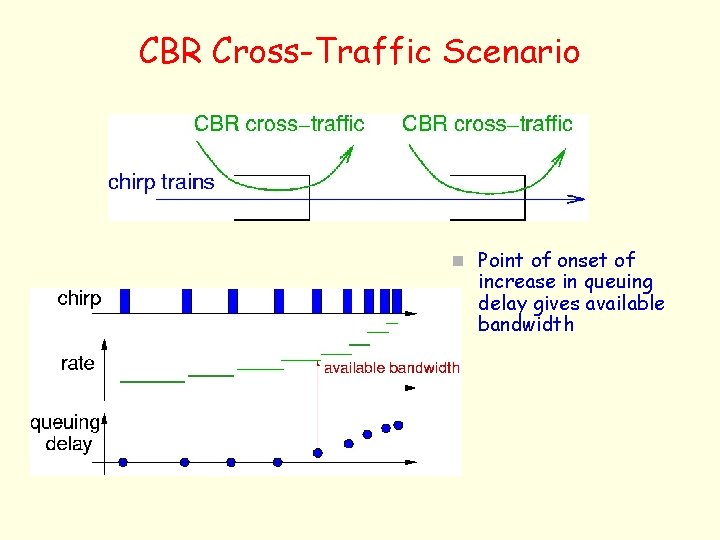

CBR Cross-Traffic Scenario n Point of onset of increase in queuing delay gives available bandwidth

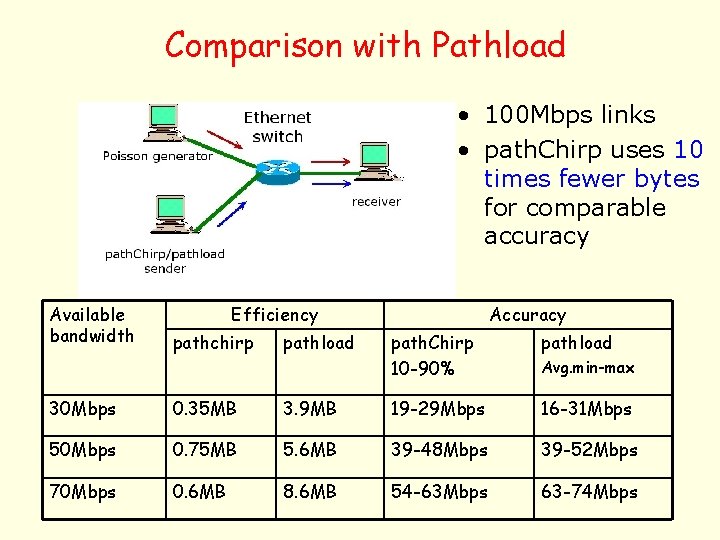

Comparison with Pathload • 100 Mbps links • path. Chirp uses 10 times fewer bytes for comparable accuracy Available bandwidth Efficiency pathchirp pathload Accuracy path. Chirp 10 -90% pathload Avg. min-max 30 Mbps 0. 35 MB 3. 9 MB 19 -29 Mbps 16 -31 Mbps 50 Mbps 0. 75 MB 5. 6 MB 39 -48 Mbps 39 -52 Mbps 70 Mbps 0. 6 MB 8. 6 MB 54 -63 Mbps 63 -74 Mbps

Experimental comparison of avail-bw estimation tools Alok Shriram, Marg Murray, Young Hyun, Nevil Brownlee, Andre Broido, k claffy, ”Comparison of Public End-to-End Bandwidth Estimation Tools on High-Speed Links, ” PAM 2005

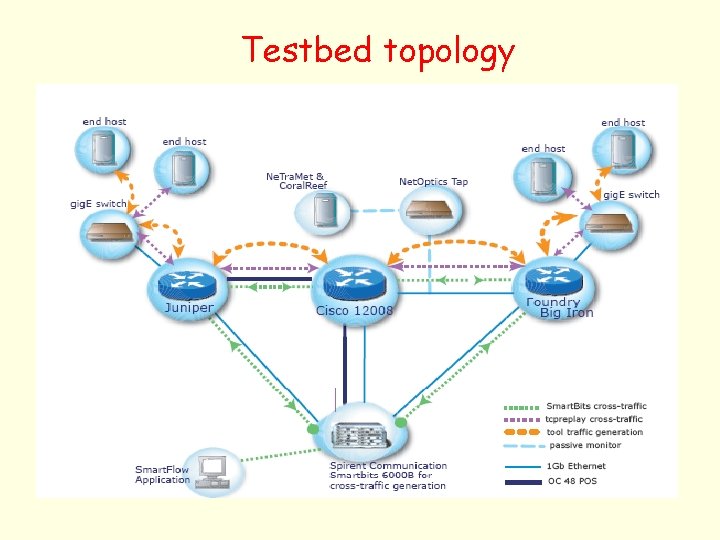

Testbed topology

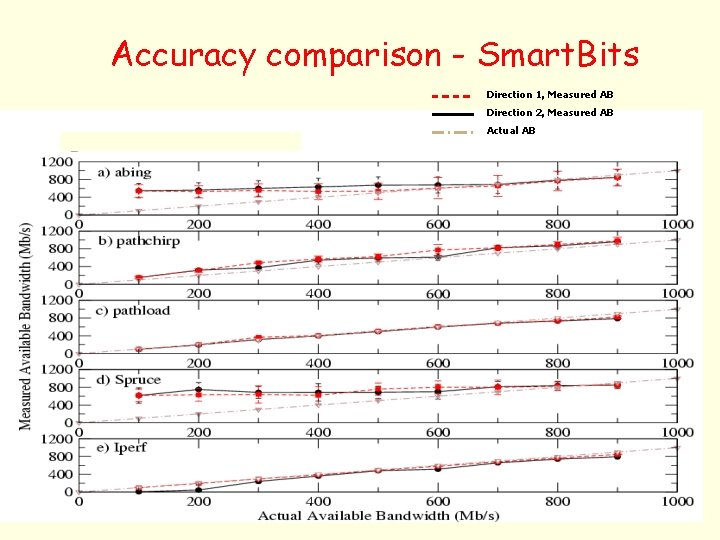

Accuracy comparison - Smart. Bits Direction 1, Measured AB Direction 2, Measured AB Actual AB

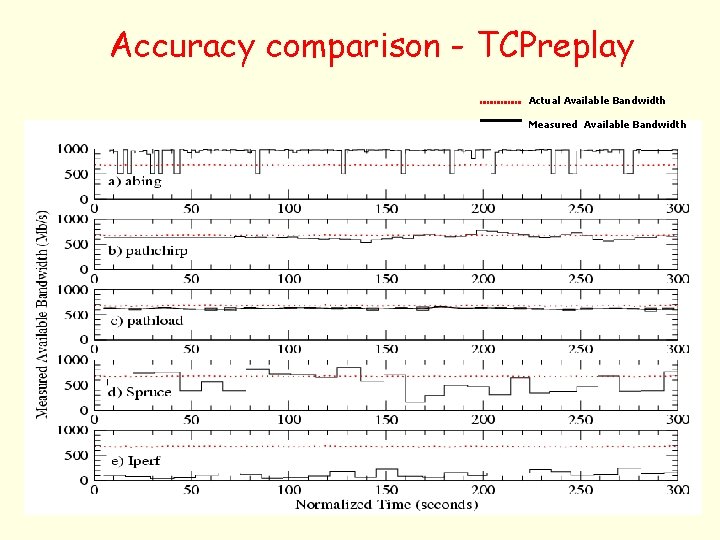

Accuracy comparison - TCPreplay Actual Available Bandwidth Measured Available Bandwidth

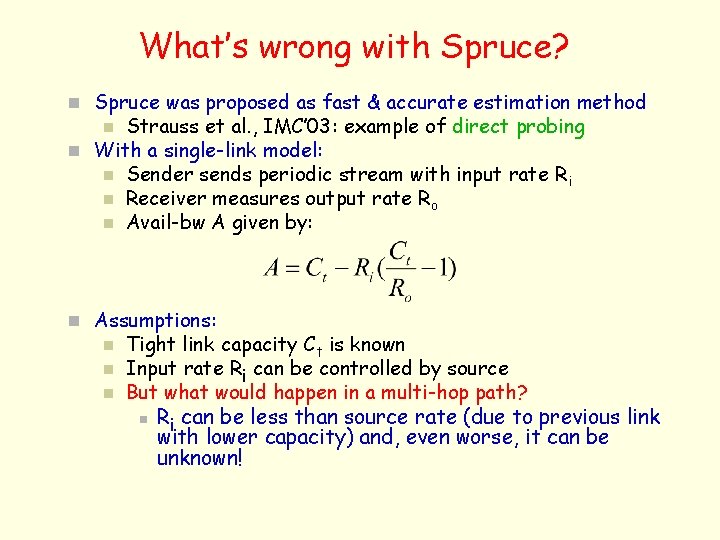

What’s wrong with Spruce? n Spruce was proposed as fast & accurate estimation method Strauss et al. , IMC’ 03: example of direct probing n With a single-link model: n Sender sends periodic stream with input rate Ri n Receiver measures output rate Ro n Avail-bw A given by: n n Assumptions: n n n Tight link capacity Ct is known Input rate Ri can be controlled by source But what would happen in a multi-hop path? n Ri can be less than source rate (due to previous link with lower capacity) and, even worse, it can be unknown!

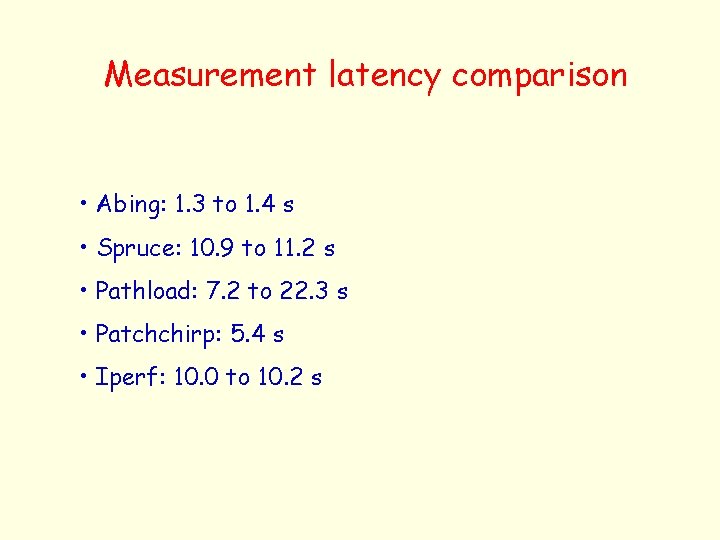

Measurement latency comparison • Abing: 1. 3 to 1. 4 s • Spruce: 10. 9 to 11. 2 s • Pathload: 7. 2 to 22. 3 s • Patchchirp: 5. 4 s • Iperf: 10. 0 to 10. 2 s

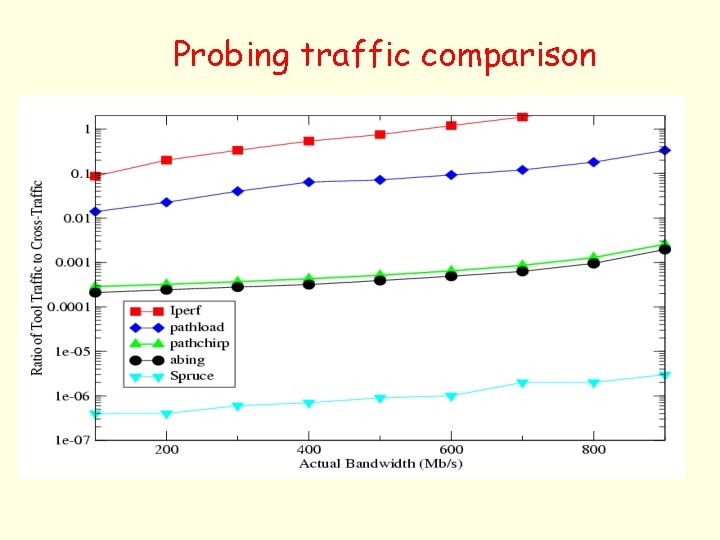

Probing traffic comparison

Applications of bandwidth estimation

Applications of bandwidth estimation n Large TCP transfers and congestion control n n Bandwidth-delay product estimation Socket buffer sizing n Streaming multimedia Adjust encoding rate based on avail-bw Intelligent routing systems n Overlay networks and multihoming n Select best path based on capacity or avail-bw Content Distribution Networks (CDNs) n Choose server based on least-loaded path SLA and Qo. S verification n Monitor path load and allocated capacity End-to-end admission control Network “spectroscopy” Several more. . n n n n

Application-1: Improved TCP Throughput with Bw. Est Ravi S. Prasad, Manish Jain, Constantine Dovrolis, “Socket Buffer Auto-Sizing for High-Performance Data Transfers, ” Journal of Grid Computing, 2003

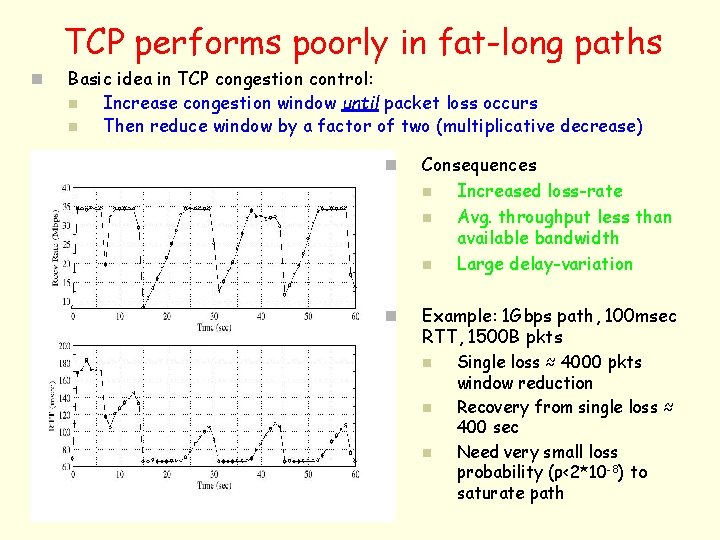

TCP performs poorly in fat-long paths n Basic idea in TCP congestion control: n Increase congestion window until packet loss occurs n Then reduce window by a factor of two (multiplicative decrease) n Consequences n Increased loss-rate n Avg. throughput less than available bandwidth n Large delay-variation n Example: 1 Gbps path, 100 msec RTT, 1500 B pkts n n n Single loss ≈ 4000 pkts window reduction Recovery from single loss ≈ 400 sec Need very small loss probability (ρ<2*10 -8) to saturate path

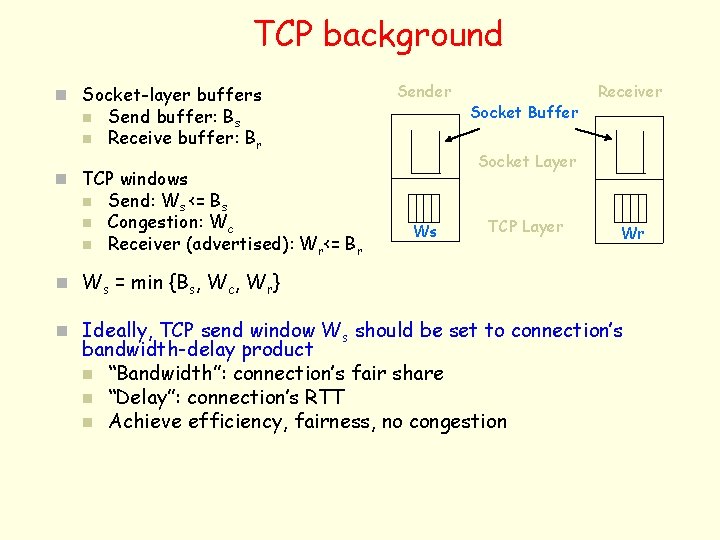

TCP background n Socket-layer buffers n n Sender Send buffer: Bs Receive buffer: Br Socket Layer n TCP windows n n n Send: Ws <= Bs Congestion: Wc Receiver (advertised): Wr<= Br Socket Buffer Receiver Ws TCP Layer Wr n Ws = min {Bs, Wc, Wr} n Ideally, TCP send window Ws should be set to connection’s bandwidth-delay product n “Bandwidth”: connection’s fair share n “Delay”: connection’s RTT n Achieve efficiency, fairness, no congestion

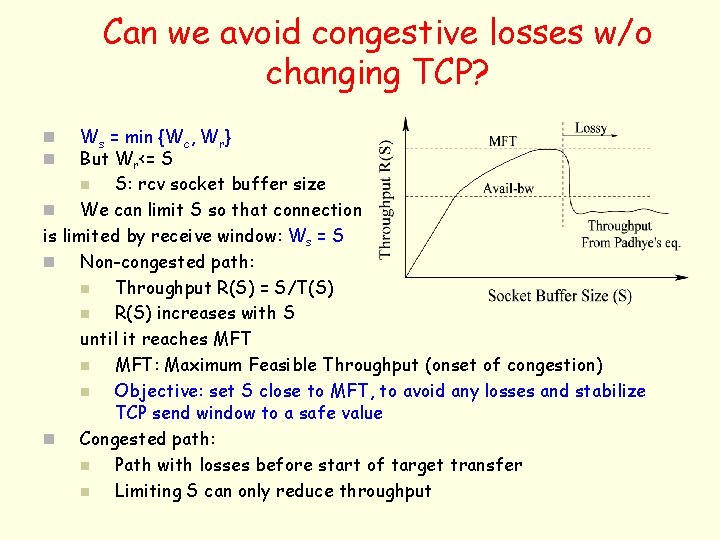

Can we avoid congestive losses w/o changing TCP? Ws = min {Wc, Wr} But Wr<= S n S: rcv socket buffer size n We can limit S so that connection is limited by receive window: Ws = S n Non-congested path: n Throughput R(S) = S/T(S) n R(S) increases with S until it reaches MFT n MFT: Maximum Feasible Throughput (onset of congestion) n Objective: set S close to MFT, to avoid any losses and stabilize TCP send window to a safe value n Congested path: n Path with losses before start of target transfer n Limiting S can only reduce throughput n n

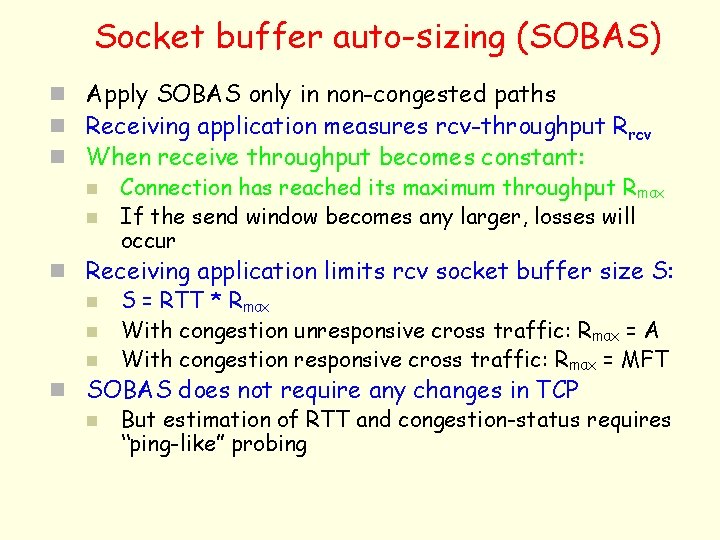

Socket buffer auto-sizing (SOBAS) n Apply SOBAS only in non-congested paths n Receiving application measures rcv-throughput Rrcv n When receive throughput becomes constant: n Connection has reached its maximum throughput Rmax n If the send window becomes any larger, losses will occur n Receiving application limits rcv socket buffer size S: n S = RTT * Rmax n With congestion unresponsive cross traffic: Rmax = A n With congestion responsive cross traffic: Rmax = MFT n SOBAS does not require any changes in TCP n But estimation of RTT and congestion-status requires “ping-like” probing

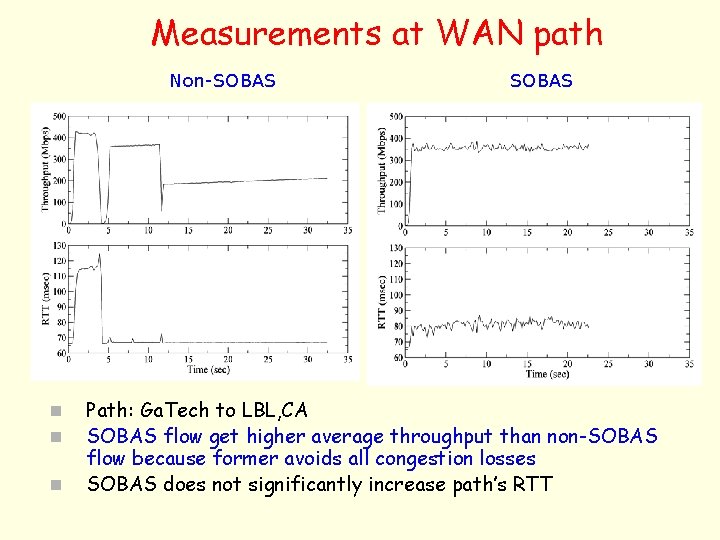

Measurements at WAN path Non-SOBAS n n n SOBAS Path: Ga. Tech to LBL, CA SOBAS flow get higher average throughput than non-SOBAS flow because former avoids all congestion losses SOBAS does not significantly increase path’s RTT

To conclude. .

Things I have not talked about n Other estimation tools & techniques Abing, netest, pipechar, STAB, pathneck, IGI/PTR, … n Per-hop capacity estimation (pathchar, clink, pchar) n Other applications n Bwest in new TCPs (e. g. , TCP Westwood, TCP FAST) n Bwest in wireless nets n Bwest in overlay routing n Bwest in multihoming n Bwest in bottleneck detection n Scalable bandwidth measurements in networks with many monitoring nodes n Practical issues n Interrupt coalescence n Traffic shapers n Non-FIFO queues n

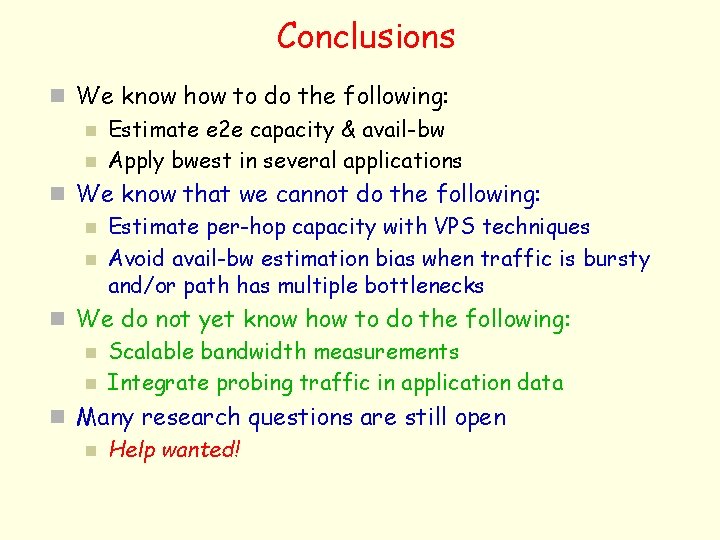

Conclusions n We know how to do the following: n Estimate e 2 e capacity & avail-bw n Apply bwest in several applications n We know that we cannot do the following: n Estimate per-hop capacity with VPS techniques n Avoid avail-bw estimation bias when traffic is bursty and/or path has multiple bottlenecks n We do not yet know how to do the following: n Scalable bandwidth measurements n Integrate probing traffic in application data n Many research questions are still open n Help wanted!

- Slides: 54