Bacteria Morphology Classification II MBBS Dr Sathya Anandam

Bacteria – Morphology & Classification II MBBS Dr Sathya Anandam Assistant prof, Microbiology

Introduction: Based on the organization of their cellular structures, all living cells can be divided into two groups: eukaryotic and prokaryotic q q Eukaryotic cell types - Animals, plants, fungi, protozoans, and algae Prokaryotic cell types - bacteria & blue green algae

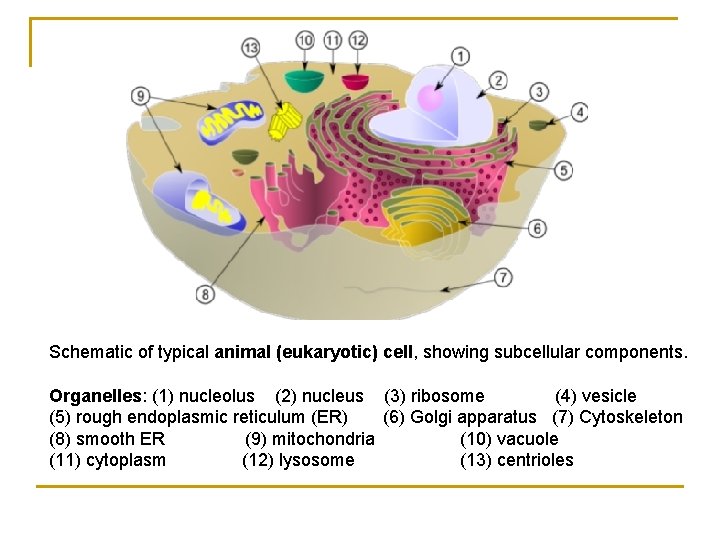

Schematic of typical animal (eukaryotic) cell, showing subcellular components. Organelles: (1) nucleolus (2) nucleus (3) ribosome (4) vesicle (5) rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (6) Golgi apparatus (7) Cytoskeleton (8) smooth ER (9) mitochondria (10) vacuole (11) cytoplasm (12) lysosome (13) centrioles

Prokaryotic Cells much smaller (microns) and more simple than eukaryotes prokaryotes are molecules surrounded by a membrane and cell wall. they lack a true nucleus and don’t have membrane bound organelles like mitochondria, etc. large surface-to-volume ratio : nutrients can easily and rapidly reach any part of the cells interior

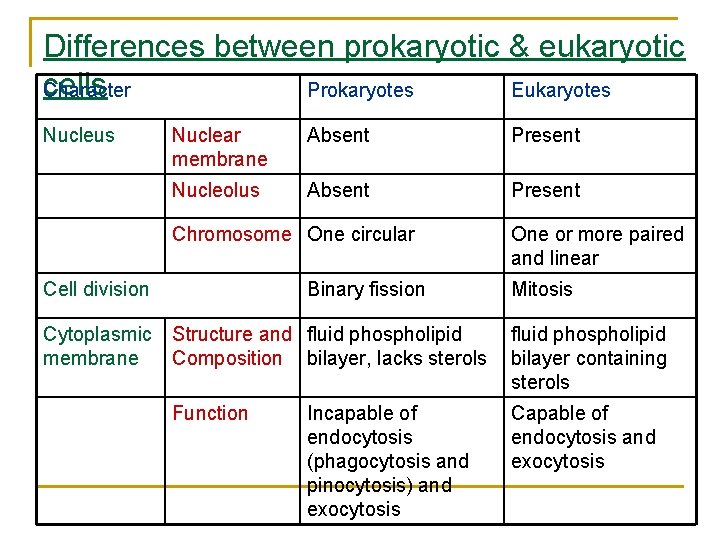

Differences between prokaryotic & eukaryotic cells Character Prokaryotes Eukaryotes Nucleus Nuclear membrane Absent Present Nucleolus Absent Present Chromosome One circular Cell division Cytoplasmic membrane Binary fission One or more paired and linear Mitosis Structure and fluid phospholipid Composition bilayer, lacks sterols fluid phospholipid bilayer containing sterols Function Capable of endocytosis and exocytosis Incapable of endocytosis (phagocytosis and pinocytosis) and exocytosis

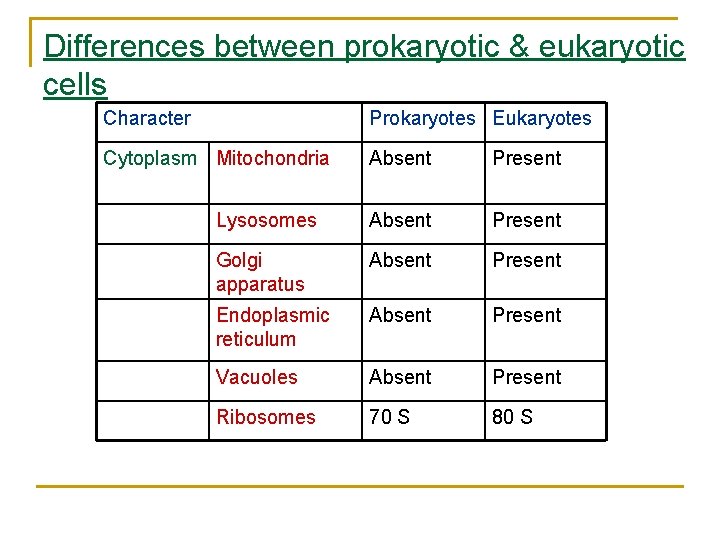

Differences between prokaryotic & eukaryotic cells Character Prokaryotes Eukaryotes Cytoplasm Mitochondria Absent Present Lysosomes Absent Present Golgi apparatus Absent Present Endoplasmic reticulum Absent Present Vacuoles Absent Present Ribosomes 70 S 80 S

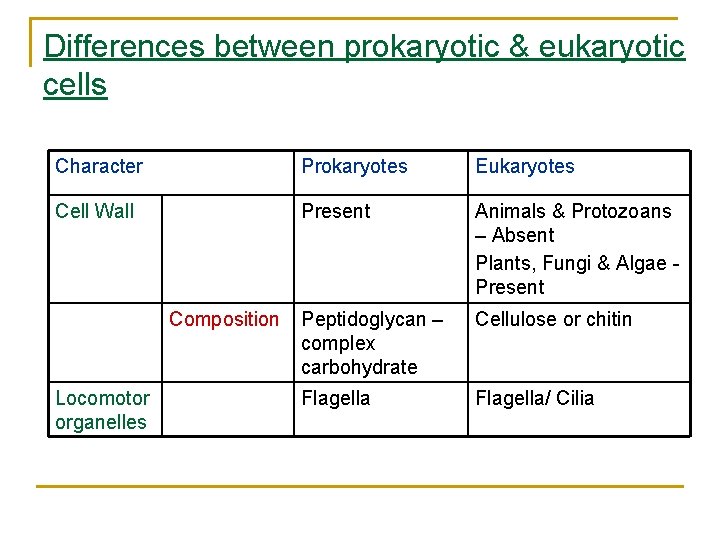

Differences between prokaryotic & eukaryotic cells Character Prokaryotes Eukaryotes Cell Wall Present Animals & Protozoans – Absent Plants, Fungi & Algae Present Peptidoglycan – complex carbohydrate Cellulose or chitin Flagella/ Cilia Composition Locomotor organelles

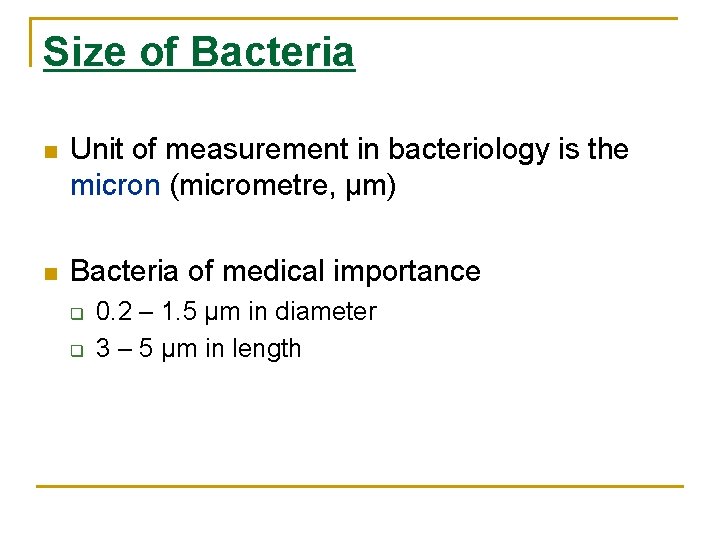

Size of Bacteria Unit of measurement in bacteriology is the micron (micrometre, µm) Bacteria of medical importance q q 0. 2 – 1. 5 µm in diameter 3 – 5 µm in length

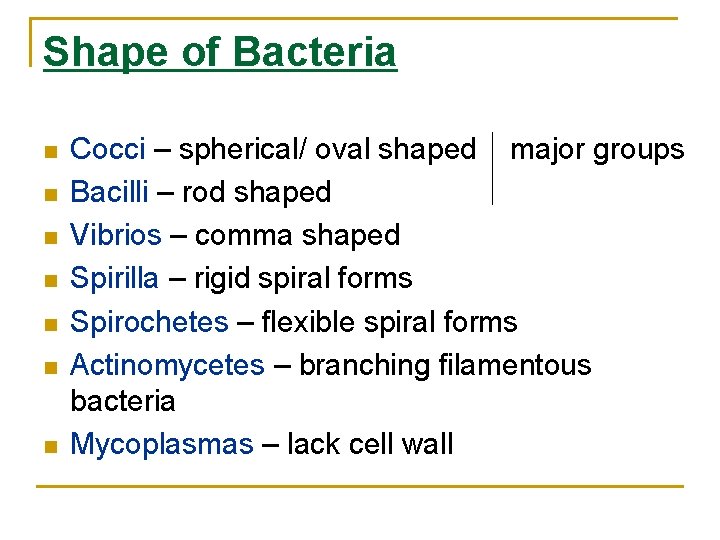

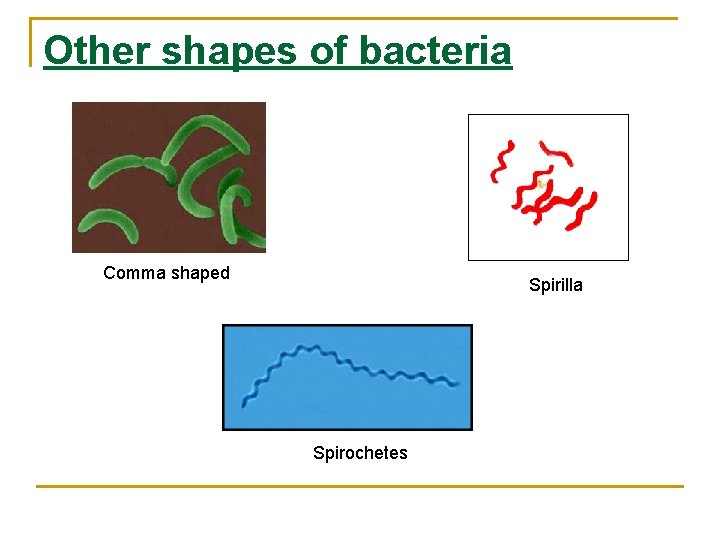

Shape of Bacteria Cocci – spherical/ oval shaped major groups Bacilli – rod shaped Vibrios – comma shaped Spirilla – rigid spiral forms Spirochetes – flexible spiral forms Actinomycetes – branching filamentous bacteria Mycoplasmas – lack cell wall

Other shapes of bacteria Comma shaped Spirilla Spirochetes

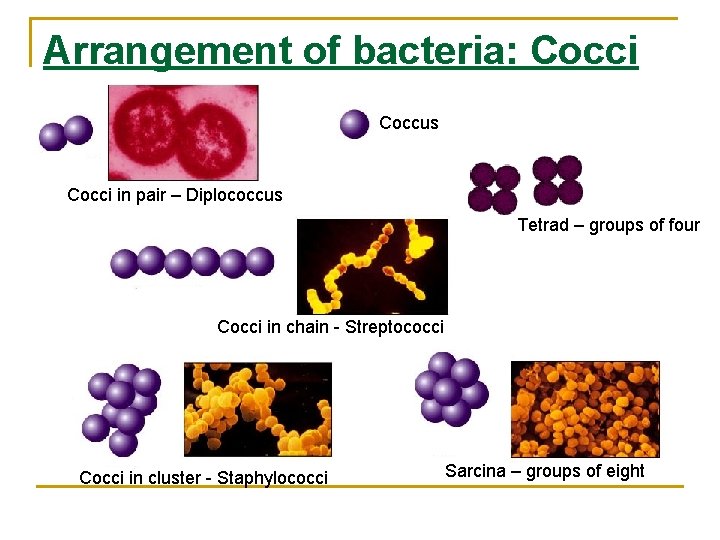

Arrangement of bacteria: Cocci Coccus Cocci in pair – Diplococcus Tetrad – groups of four Cocci in chain - Streptococci Cocci in cluster - Staphylococci Sarcina – groups of eight

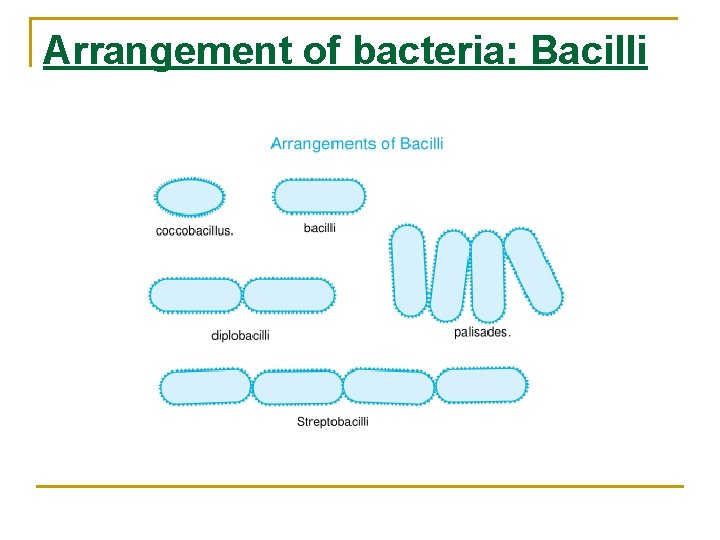

Arrangement of bacteria: Bacilli

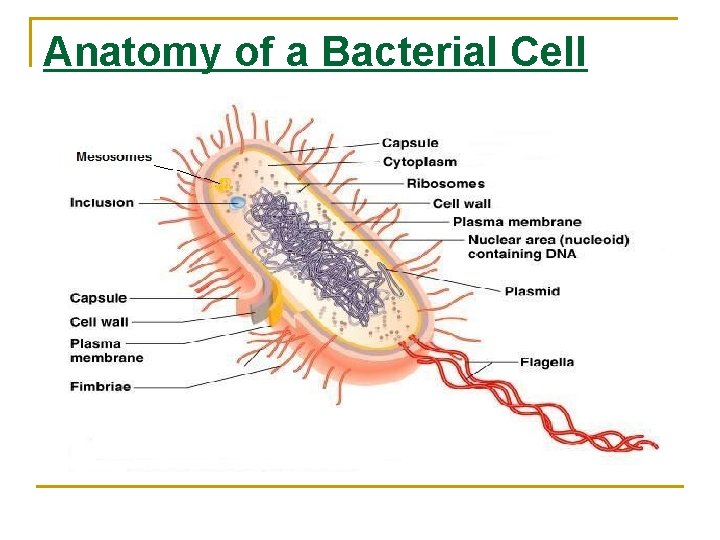

Anatomy of a Bacterial Cell

Anatomy of A Bacterial Cell Outer layer – two components: 1. 2. Rigid cell wall Cytoplasmic (Cell/ Plasma) membrane – present beneath cell wall Cytoplasm – cytoplasmic inclusions, ribosomes, mesosomes and nucleus Additional structures – plasmid, slime layer, capsule, flagella, fimbriae (pili), spores

Structure & Function of Cell Components

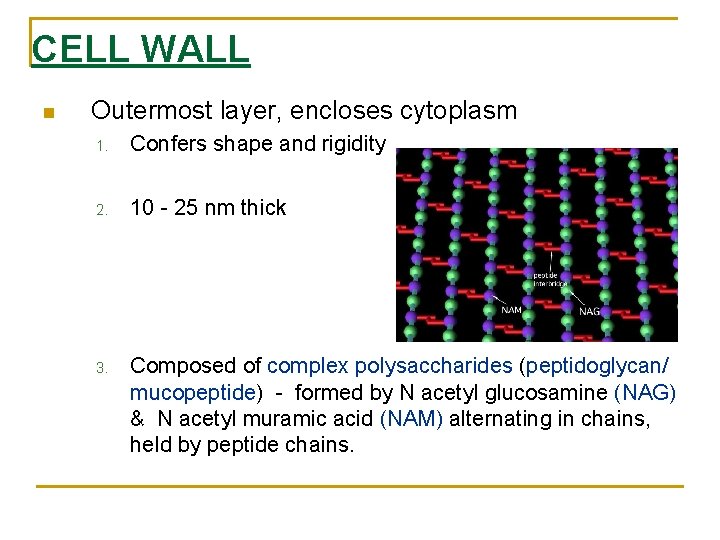

CELL WALL Outermost layer, encloses cytoplasm 1. Confers shape and rigidity 2. 10 - 25 nm thick 3. Composed of complex polysaccharides (peptidoglycan/ mucopeptide) - formed by N acetyl glucosamine (NAG) & N acetyl muramic acid (NAM) alternating in chains, held by peptide chains.

Cell Wall Cell wall – 4. Carries bacterial antigens – important in virulence & immunity 5. Chemical nature of the cell wall helps to divide bacteria into two broad groups – Gram positive & Gram negative 6. Gram positive bacteria have simpler chemical nature than Gram negative bacteria. 7. Several antibiotics may interfere with cell wall synthesis e. g. Penicillin, Cephalosporins

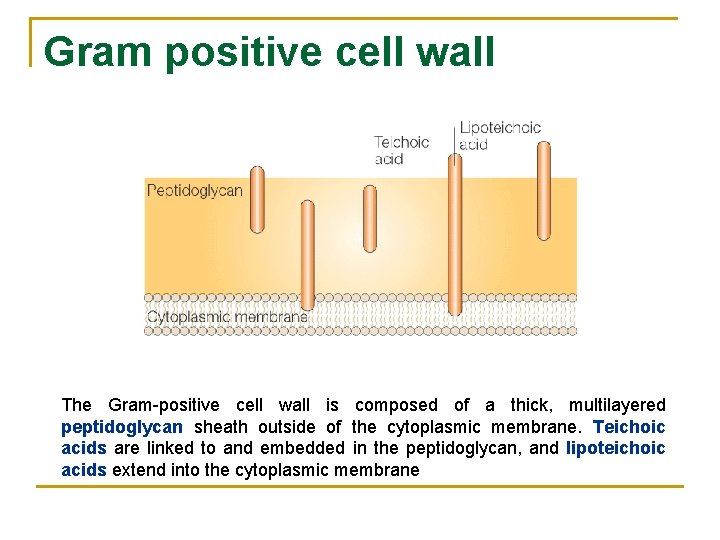

Gram positive cell wall The Gram-positive cell wall is composed of a thick, multilayered peptidoglycan sheath outside of the cytoplasmic membrane. Teichoic acids are linked to and embedded in the peptidoglycan, and lipoteichoic acids extend into the cytoplasmic membrane

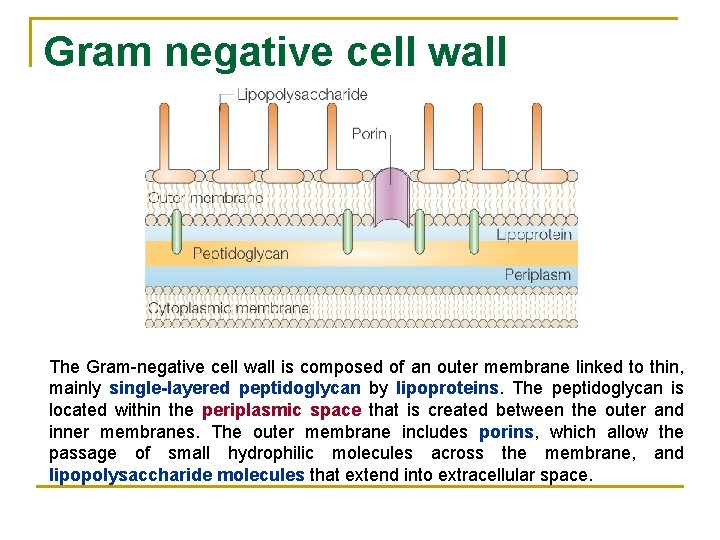

Gram negative cell wall The Gram-negative cell wall is composed of an outer membrane linked to thin, mainly single-layered peptidoglycan by lipoproteins. The peptidoglycan is located within the periplasmic space that is created between the outer and inner membranes. The outer membrane includes porins, which allow the passage of small hydrophilic molecules across the membrane, and lipopolysaccharide molecules that extend into extracellular space.

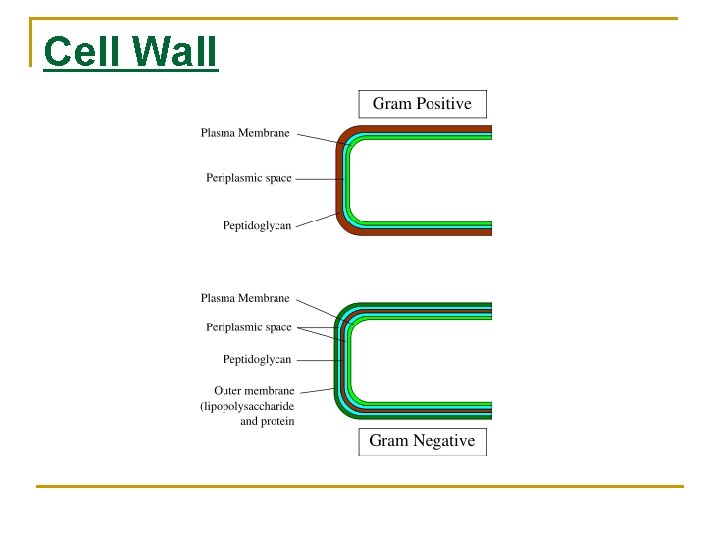

Cell Wall

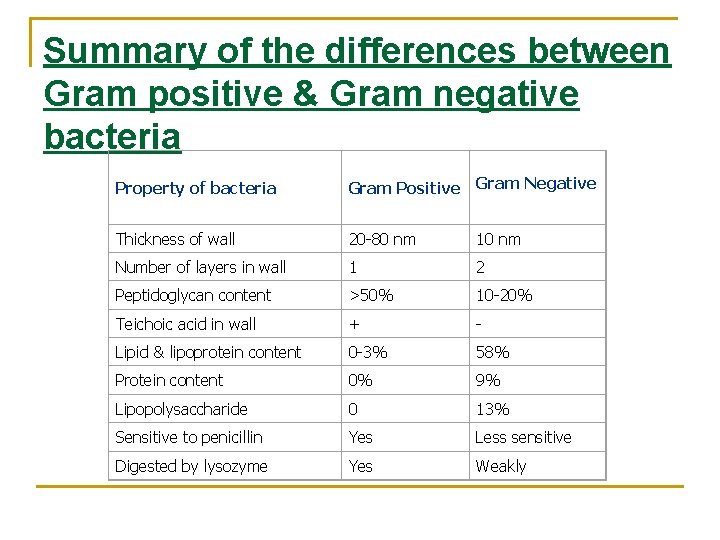

Summary of the differences between Gram positive & Gram negative bacteria Property of bacteria Gram Positive Gram Negative Thickness of wall 20 -80 nm 10 nm Number of layers in wall 1 2 Peptidoglycan content >50% 10 -20% Teichoic acid in wall + - Lipid & lipoprotein content 0 -3% 58% Protein content 0% 9% Lipopolysaccharide 0 13% Sensitive to penicillin Yes Less sensitive Digested by lysozyme Yes Weakly

Demonstration of cell wall. Plasmolysis: In hypertonic environment the water diffuses from the bacterial cell and the cytoplasm shrivels up and pulls away from the cell wall. Microdissection Reaction with specific antibodies Mechanical rupture of the cell: ultrasonic waves. Differential staining procedures Electron microscopy

CELL WALL –DEFICIENT ORGANISMS They are bound by soft trilaminar unit membrane containing sterols. Lack cell wall they are highly plastic and they can pass through bacterial filters. Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma They lack the cell wall precursors like muramic acids or diaminopimelic acid.

L-FORMS Kleineberger-Nobel, named them L-forms after LISTER INSTITUTE London. These are abnormal growth forms developed either spontaneously or in the presence of penicillin that interfere with cell wall synthesis. They differ from parent bacteria in lacking rigid cell wall. They are capable of growing and multiplying.

PROTOPLASTS AND SPHEROPLASTS: When a cell is subjected to hydrolysis with lysozyme results in the removal of cell wall. If the media is osmotically protective it results in the liberation of protoplasts from Gram positive cells. Spheroplasts are produced by gram negative cells which retain their outer membrane.

Cytoplasmic (Plasma) membrane Thin layer 5 -10 nm, separates cell wall from cytoplasm Acts as a semipermeable membrane: controls the inflow and outflow of metabolites Composed of lipoproteins with small amounts of carbohydrates

Functions: 1. 2. 3. Permeability and transport: active, passive and group translocation Electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation : cell respiration Excretion of hydrolytic exoenzymes & pathogenicity proteins : breaks polymers in to units.

Cytoplasmic Matrix Colloidal system of a variety of organic and inorganic solutes between the plasma membrane and the nucleiod. Viscous watery solution Packed with ribosomes Highly organised

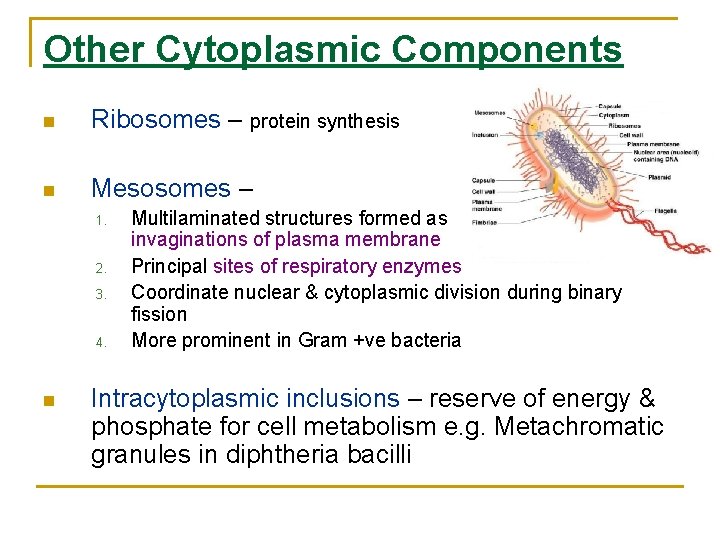

Other Cytoplasmic Components Ribosomes – protein synthesis Mesosomes – 1. 2. 3. 4. Multilaminated structures formed as invaginations of plasma membrane Principal sites of respiratory enzymes Coordinate nuclear & cytoplasmic division during binary fission More prominent in Gram +ve bacteria Intracytoplasmic inclusions – reserve of energy & phosphate for cell metabolism e. g. Metachromatic granules in diphtheria bacilli

1. 2. 3. Demonstration: Special stains: Volutin granules: Alberts, Neissers, Ponders, Puchs Polysacharide granules: Iodine Lipid inclusions: Sudan Black

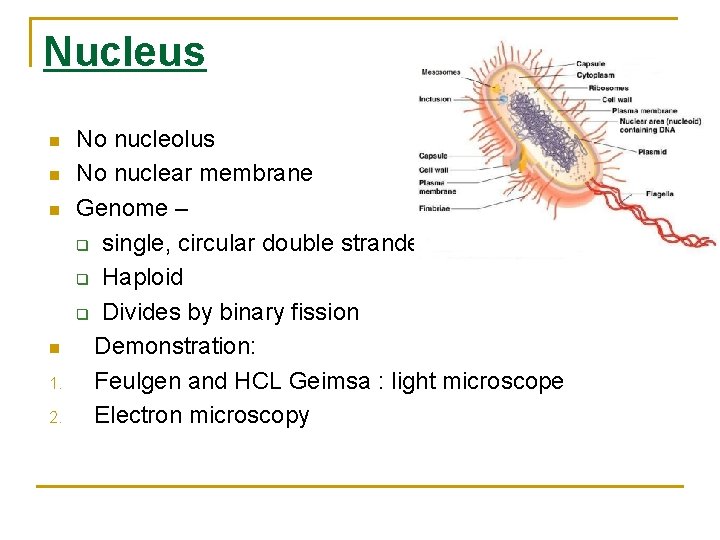

Nucleus 1. 2. No nucleolus No nuclear membrane Genome – q single, circular double stranded DNA. q Haploid q Divides by binary fission Demonstration: Feulgen and HCL Geimsa : light microscope Electron microscopy

Additional Organelles Plasmid – 1. q Extranuclear genetic elements consisting of DNA q Transmitted to daughter cells during binary fission q May be transferred from one bacterium to another q Not essential for life of the cell q Confer certain properties e. g. drug resistance, toxicity

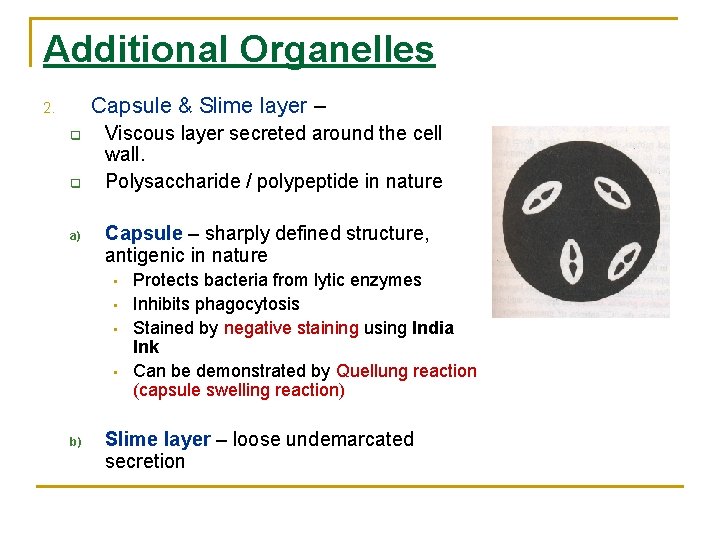

Additional Organelles Capsule & Slime layer – 2. q q a) Viscous layer secreted around the cell wall. Polysaccharide / polypeptide in nature Capsule – sharply defined structure, antigenic in nature • • b) Protects bacteria from lytic enzymes Inhibits phagocytosis Stained by negative staining using India Ink Can be demonstrated by Quellung reaction (capsule swelling reaction) Slime layer – loose undemarcated secretion

1. 2. 3. 4. Functions of capsule: Antiphagocytic Adherence Resistance to dessication. Excludes viruses and hydrophobic molecules

Capsule Demonstration Staining Positive: crystal violet, Hiss, Muir s Negative : India ink Electron microscopy Serology- capsular antigens q Quellung reaction

Additional Organelles- Flagella q Long (3 to 12 µm), filamentous surface appendages q Organs of locomotion q Chemically, composed of proteins called flagellins q The number and distribution of flagella on the bacterial surface are characteristic for a given species - hence are useful in identifying and classifying bacteria q Flagella may serve as antigenic determinants (e. g. the H antigens of Gram-negative enteric bacteria) q Presence shown by motility e. g. hanging drop preparation

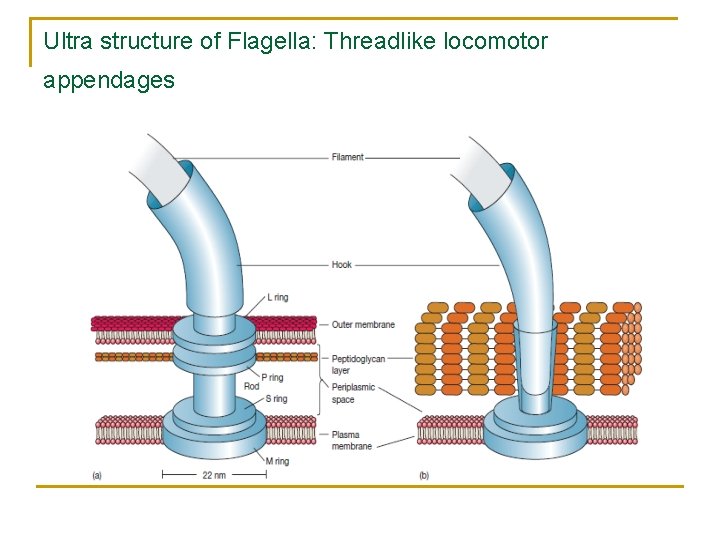

Ultra structure of Flagella: Threadlike locomotor appendages

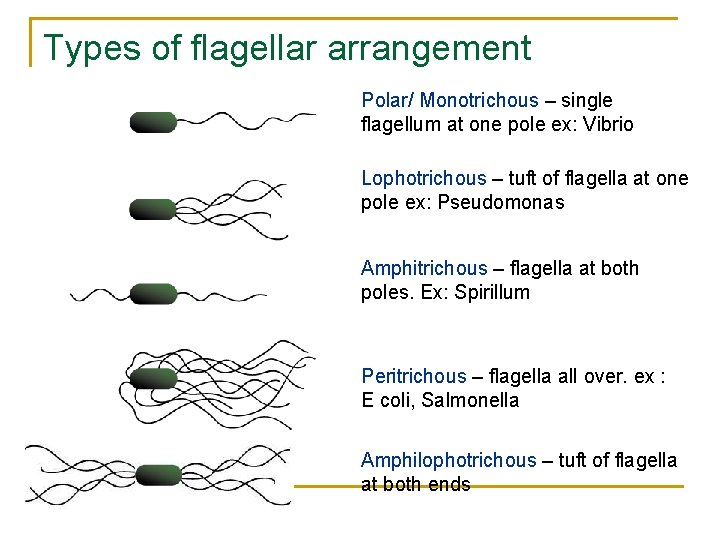

Types of flagellar arrangement Polar/ Monotrichous – single flagellum at one pole ex: Vibrio Lophotrichous – tuft of flagella at one pole ex: Pseudomonas Amphitrichous – flagella at both poles. Ex: Spirillum Peritrichous – flagella all over. ex : E coli, Salmonella Amphilophotrichous – tuft of flagella at both ends

Demonstration: Staining : wet mount method, Kirkpatrick, Leifsons , Loefflers etc. Electron microscopy

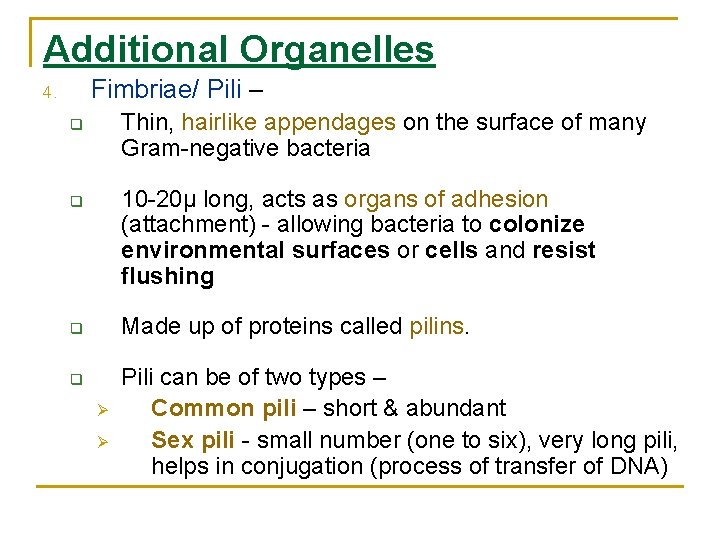

Additional Organelles Fimbriae/ Pili – 4. Thin, hairlike appendages on the surface of many Gram-negative bacteria q 10 -20µ long, acts as organs of adhesion (attachment) - allowing bacteria to colonize environmental surfaces or cells and resist flushing q Made up of proteins called pilins. q q Ø Ø Pili can be of two types – Common pili – short & abundant Sex pili - small number (one to six), very long pili, helps in conjugation (process of transfer of DNA)

Demonstration: Electron microscopy. Function: Attachment to solid surfaces Antigenic Agglutination to RBCs

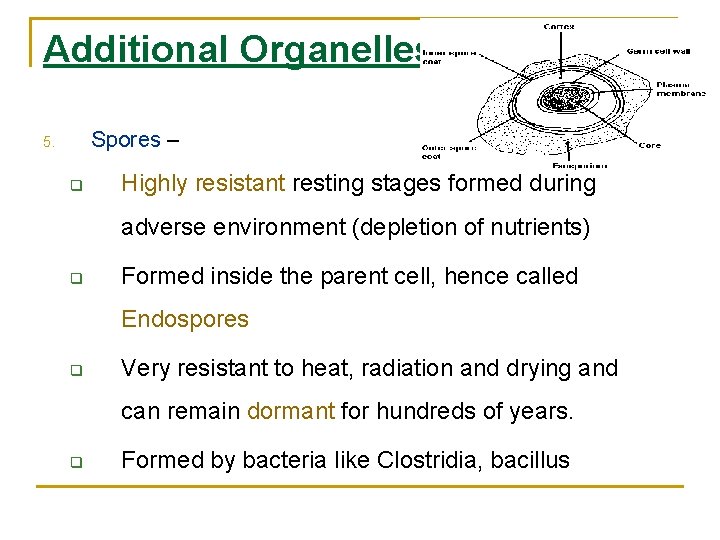

Additional Organelles Spores – 5. q Highly resistant resting stages formed during adverse environment (depletion of nutrients) q Formed inside the parent cell, hence called Endospores q Very resistant to heat, radiation and drying and can remain dormant for hundreds of years. q Formed by bacteria like Clostridia, bacillus

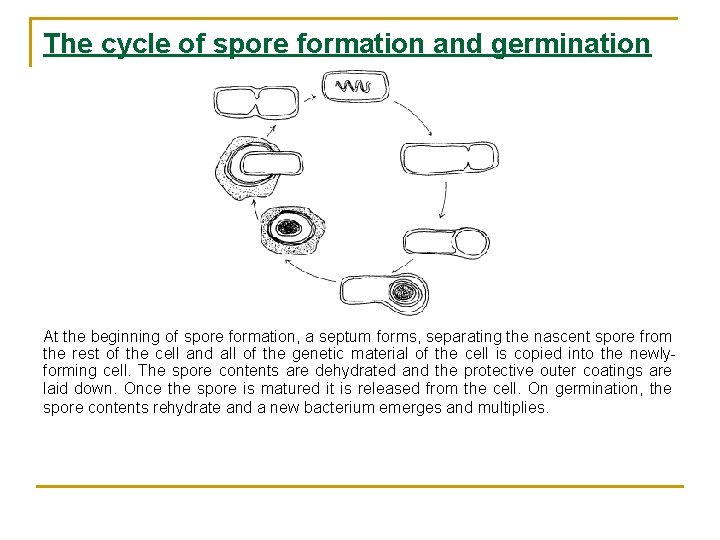

The cycle of spore formation and germination At the beginning of spore formation, a septum forms, separating the nascent spore from the rest of the cell and all of the genetic material of the cell is copied into the newlyforming cell. The spore contents are dehydrated and the protective outer coatings are laid down. Once the spore is matured it is released from the cell. On germination, the spore contents rehydrate and a new bacterium emerges and multiplies.

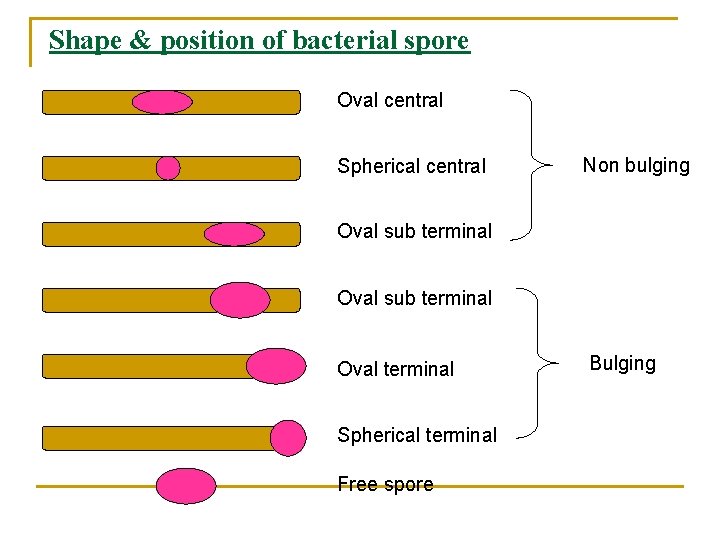

Shape & position of bacterial spore Oval central Spherical central Non bulging Oval sub terminal Oval terminal Spherical terminal Free spore Bulging

Uses: Bacillus stearothermophilus -spores q Used for quality control of heat sterilization equipment Bacillus anthracis - spores q Used in biological warfare

Demonstration: Unstained in Grams stain Modified Zeihl Neelson, Malachite green, Fuschin Nigrosin Unstained wet preparation in phase contrast microscopy

Pleomorphism & Involution forms Pleomorphism – great variation in shape & size of individual cells e. g. Proteus species Involution forms – swollen & aberrant forms in ageing cultures, especially in the presence of high salt concentration e. g. plague bacillus Cause – defective cell wall synthesis

Microbial Growth refers to the increase in number of cells, not the size of the cells Bacteria divide by binary fission

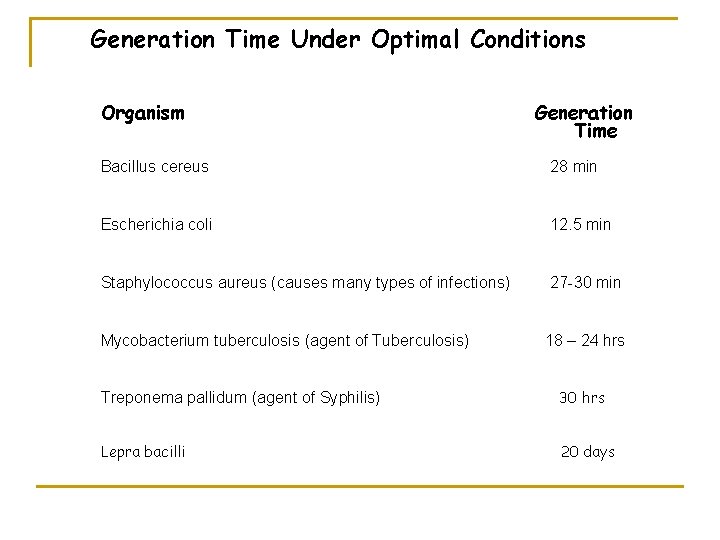

The interval of time between two cell divisions or the time required by the bacterium to give rise to two daughter cells under optimum conditions, is known as the generation time or population doubling time.

Generation Time Under Optimal Conditions Organism Generation Time Bacillus cereus 28 min Escherichia coli 12. 5 min Staphylococcus aureus (causes many types of infections) 27 -30 min Mycobacterium tuberculosis (agent of Tuberculosis) 18 – 24 hrs Treponema pallidum (agent of Syphilis) 30 hrs Lepra bacilli 20 days

• When pathogenic bacteria multiply in host tissues, the situation maybe intermediate between a batch culture and a continuous culture; the source of nutrients maybe inexhaustible but the parasite has to face the defence mechanisms of the body. • Bacteria growing on solid media form colonies. • Each colony represents a clone of cells derived from a single parent cell. • In liquid media, growth is diffuse.

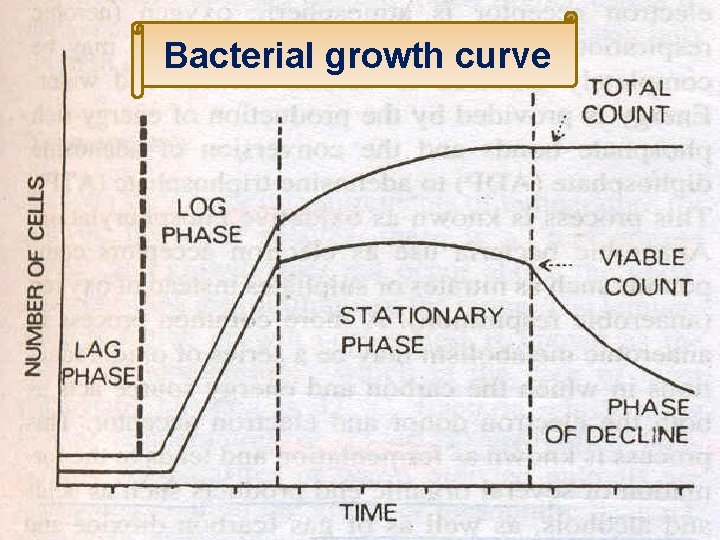

• When a bacterium is seeded into a suitable liquid medium and incubated, its growth follows a definite course. • If bacterial counts are made at intervals after inoculation and plotted in relation to time, a growth curve is obtained. It shows 4 phases : Lag, Log Exponential, Stationary & phase of Decline.

Bacterial growth curve

1) Lag phase: q No cell division. q The bacteria form the enzymes and molecules needed for replication. q Clinical significance: this phase = incubation period of a disease. 2) Logarithmic phase: q Rapid cell division occurs. q The number of living bacteria increases by time. q Clinical significance: this phase = symptoms and signs of the disease.

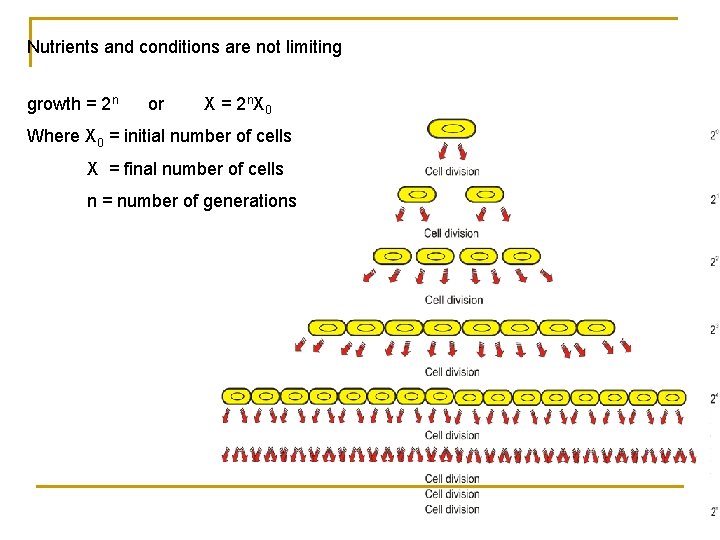

Nutrients and conditions are not limiting growth = 2 n or X = 2 n. X 0 Where X 0 = initial number of cells X = final number of cells n = number of generations

3) Stationary phase: q Nutrients are exhausted. q Waste products are accumulated. q The number of dying cells = number of new cells. q The number of living bacteria remains constant.

4) Decline phase: q Nutrients are more exhausted. q Waste products are more accumulated. q The number of dying cells > number of new cells. q The number of living bacteria decreases by time. q Clinical significance: this phase = recovery and convalescence.

morphological and physiological alterations of the cells in various stages of the growth curve • Bacteria have the maximum cell size towards the end of the lag phase. • In the log phase, cells are smaller and stain uniformly. • In the stationary phase, cells frequently are gram variable and show irregular staining due to the presence of intracellular storage granules. • Sporulation occurs at this stage. production of exotoxins & antibiotics • Phase of Decline –involution forms(with ageing).

Nutritional Requirements Growth of prokaryotes depends on nutritional factors as well as physical environment Main factors to be considered are: Required elements Growth factors Energy sources

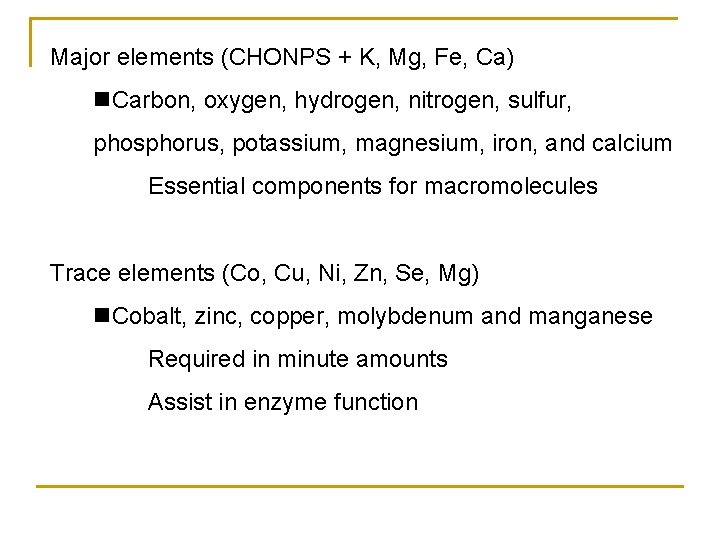

Major elements (CHONPS + K, Mg, Fe, Ca) Carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, iron, and calcium Essential components for macromolecules Trace elements (Co, Cu, Ni, Zn, Se, Mg) Cobalt, zinc, copper, molybdenum and manganese Required in minute amounts Assist in enzyme function

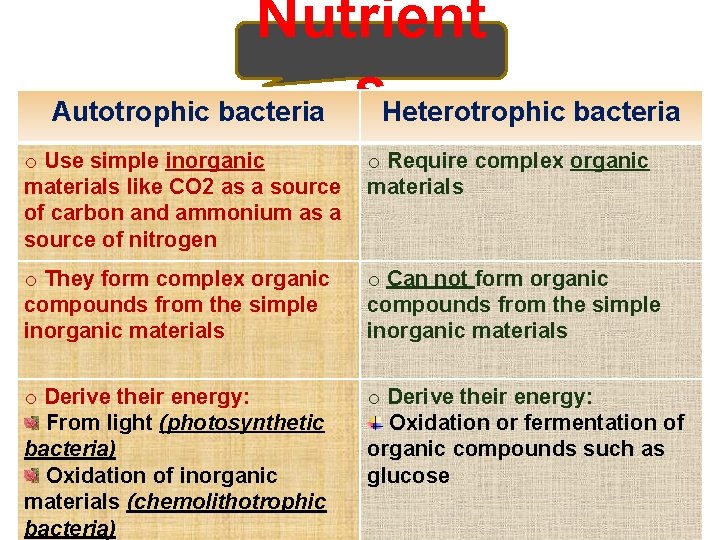

Nutrient Autotrophic bacteria s. Heterotrophic bacteria o Use simple inorganic materials like CO 2 as a source of carbon and ammonium as a source of nitrogen o Require complex organic materials o They form complex organic compounds from the simple inorganic materials o Can not form organic compounds from the simple inorganic materials o Derive their energy: From light (photosynthetic bacteria) Oxidation of inorganic materials (chemolithotrophic bacteria) o Derive their energy: Oxidation or fermentation of organic compounds such as glucose

Most bacteria of medical importance are heterotrophic bacteria

Growth factors v These are organic compounds which bacteria must contain to grow. v But, they are unable to synthesize them v So, they must be added ready formed to the culture medium v Examples: amino acids, vitamins, purines and pyrimidines

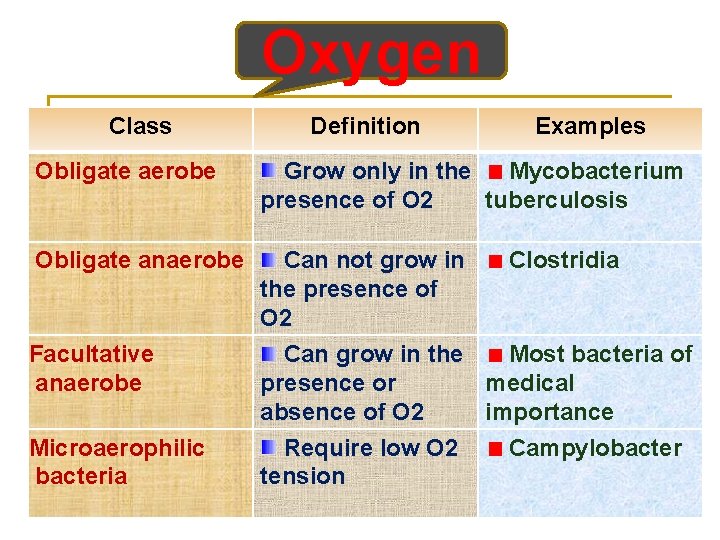

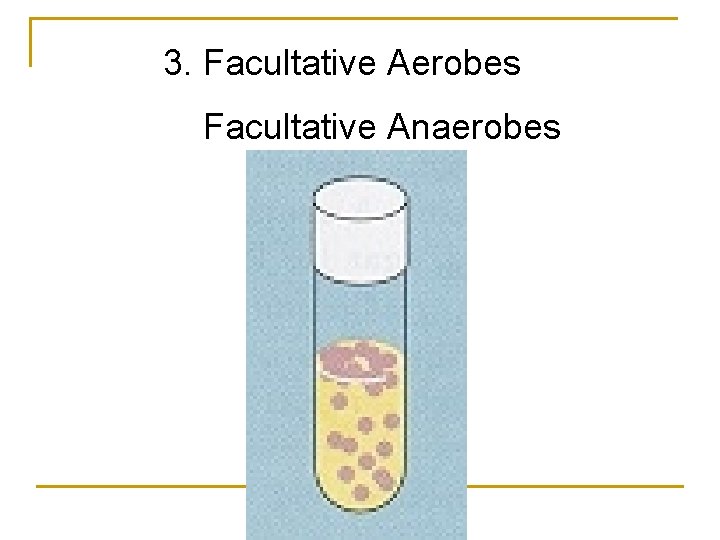

Oxygen Class Definition Examples Obligate aerobe Grow only in the Mycobacterium presence of O 2 tuberculosis Obligate anaerobe Can not grow in Clostridia the presence of O 2 Can grow in the Most bacteria of presence or medical absence of O 2 importance Require low O 2 Campylobacter tension Facultative anaerobe Microaerophilic bacteria

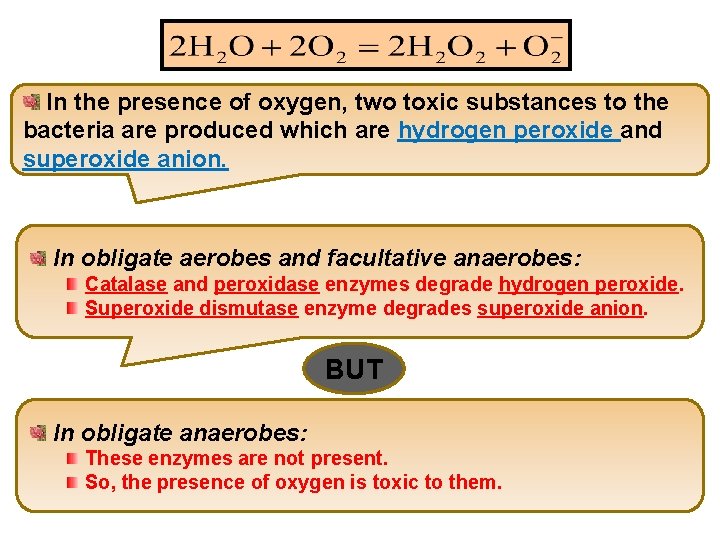

In the presence of oxygen, two toxic substances to the bacteria are produced which are hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion. In obligate aerobes and facultative anaerobes: Catalase and peroxidase enzymes degrade hydrogen peroxide. Superoxide dismutase enzyme degrades superoxide anion. BUT In obligate anaerobes: These enzymes are not present. So, the presence of oxygen is toxic to them.

1. Obligate Aerobes

2. Obligate Anaerobes

3. Facultative Aerobes Facultative Anaerobes

Carbon dioxide q Most bacteria require CO 2 in small concentration as that in the air. q However, some bacteria require higher concentrations of CO 2. q These bacteria are called capnophilic bacteria. q Example: v Neisseria requires 5 -10% CO 2

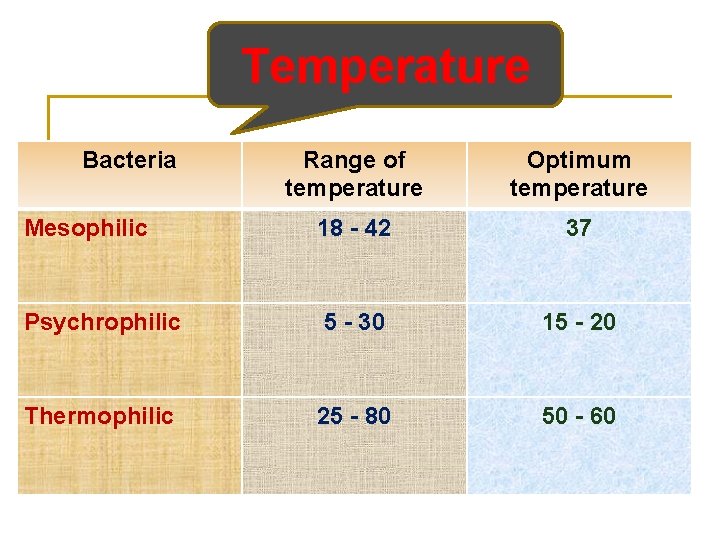

Temperature Bacteria Range of temperature Optimum temperature Mesophilic 18 - 42 37 Psychrophilic 5 - 30 15 - 20 Thermophilic 25 - 80 50 - 60

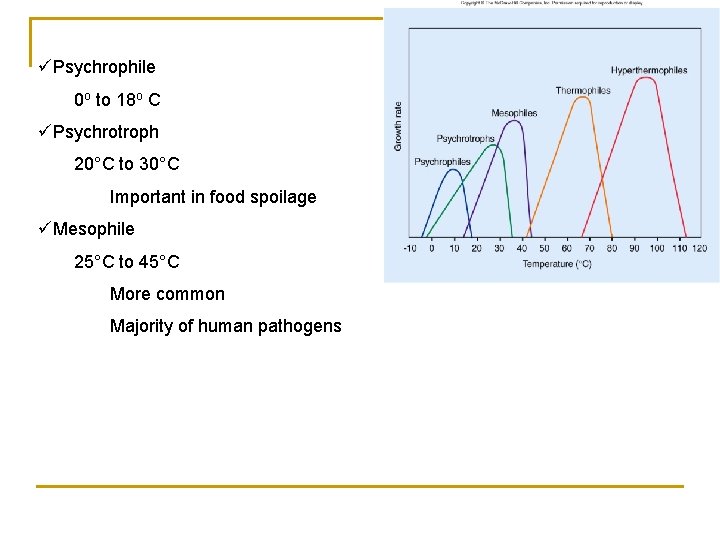

üPsychrophile 0 o to 18 o C üPsychrotroph 20°C to 30°C Important in food spoilage üMesophile 25°C to 45°C More common Majority of human pathogens

üThermophiles 45°C to 70°C Common in hot springs and hot water heaters. Lipids in PM more saturated than mesophiles (higher melting points) üHyperthermophiles 70°C to 110°C Live at very high temperatures, high enough where water threatens to become a gas Usually members of Archaea Found in hydrothermal vents

Most bacteria of medical importance are mesophilic bacteria

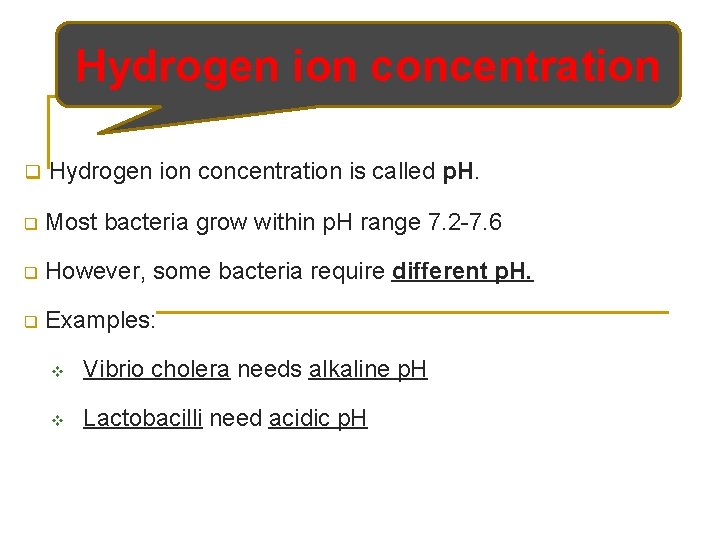

Hydrogen ion concentration q Hydrogen ion concentration is called p. H. q Most bacteria grow within p. H range 7. 2 -7. 6 q However, some bacteria require different p. H. q Examples: v Vibrio cholera needs alkaline p. H v Lactobacilli need acidic p. H

p. H is the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion concentration Acidophiles grow best between p. H 0 and 5. 5 Neutrophiles grow best between p. H 5. 5 and 8. 0 Alkalophiles grow best between p. H 8. 5 and 11. 5

• Alkalophiles grow best at p. H 10. 0 or higher • Despite wide variations in habitat p. H, the internal p. H of most microorganisms is maintained near neutrality either by proton/ion exchange or by internal buffering • Sudden p. H changes can inactivate enzymes and damage PMs

Microbes that require a high water activity (near or at 1) are termed nonhalophiles. (Halophile = salt-loving) Some bacteria require salt to grow and are called halophiles. If a very high concentration of salt is required (around saturation), the organisms are termed extreme halophiles. A nonhalophile that can grows best with almost no salt but can still grow with low levels of salt (~ 7%) is called halotolerant.

Pressure: Barotolerant organisms are adversely affected by increased pressure, but not as severely as are nontolerant organisms Barophilic organisms require, or grow more rapidly in the presence of, increased pressure

Radiation Ultraviolet radiation damages cells by causing the formation of thymine dimers in DNA Photoreactivation repairs thymine dimers by direct splitting when the cells are exposed to blue light Dark reactivation repairs thymine dimers by excision and replacement in the absence of light

Ionizing radiation such as X rays or gamma rays are even more harmful to microorganisms than ultraviolet radiation Low levels produce mutations and may indirectly result in death High levels are directly lethal by direct damage to cellular macromolecules or through the production of oxygen free radicals

- Slides: 81