Authentication Methods From Digital Signatures to Hashes Lecture

- Slides: 33

Authentication Methods: From Digital Signatures to Hashes

Lecture Motivation l We have looked at confidentiality services, and also examined the information theoretic framework for security. l Confidentiality between Alice and Bob only guarantees that Eve cannot read the message, it does not address: – Is Alice really talking to Bob? – Is Bob really talking to Alice? l In this lecture, we will look at the following problems: – Entity Authentication: Proof of the identity of an individual – Message Authentication: (Data origin authentication) Proof that the source of information really is what it claims to be – Message Signing: Binding information to a particular entity – Data Integrity: Ensuring that information has not been altered by unknown entities

Lecture Outline l Discrete Logarithms and El. Gamal – Primitive elements and some more number theory (quickly) – DLOG – El. Gamal, another Public Key Algorithm… l Digital Signatures: – The basic idea – RSA Signatures and El. Gamal Signatures – Inefficiencies: Hashing and Signing l Hash Functions: – Definitions and terminology – CHP Hash – SHA-1 l Message Authentication Codes Note: Some attacks will be discussed. More attacks and cryptanalysis will come later in the semester

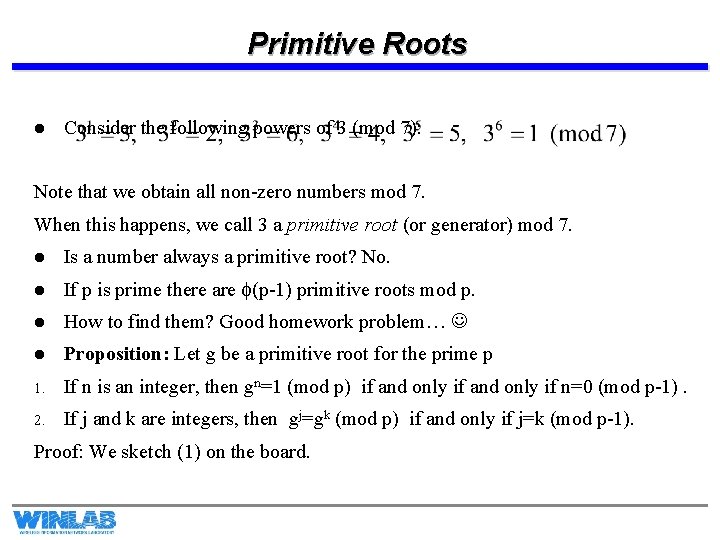

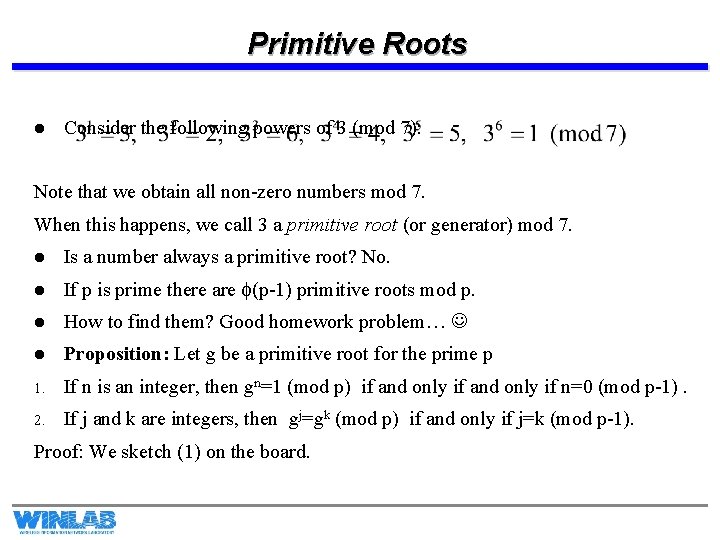

Primitive Roots l Consider the following powers of 3 (mod 7): Note that we obtain all non-zero numbers mod 7. When this happens, we call 3 a primitive root (or generator) mod 7. l Is a number always a primitive root? No. l If p is prime there are f(p-1) primitive roots mod p. l How to find them? Good homework problem… l Proposition: Let g be a primitive root for the prime p 1. If n is an integer, then gn=1 (mod p) if and only if n=0 (mod p-1). 2. If j and k are integers, then gj=gk (mod p) if and only if j=k (mod p-1). Proof: We sketch (1) on the board.

l Let p be a prime, Discrete and a and b. Logarithms nonzero integers (mod p) with l The problem of finding x is called the discrete logarithm problem, l Often a will be a primitive root mod p. l The discrete log behaves like the normal log in many ways: l Generally, finding the discrete log is a hard problem. l f(x) = ax (mod p) is an example of a one-way function.

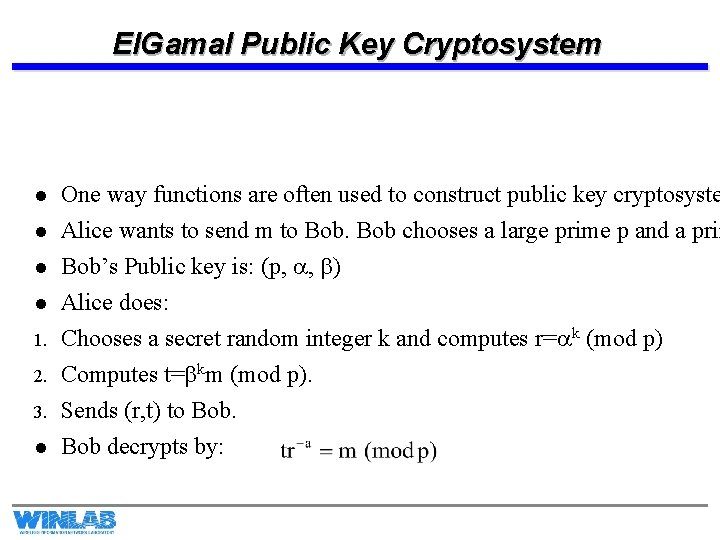

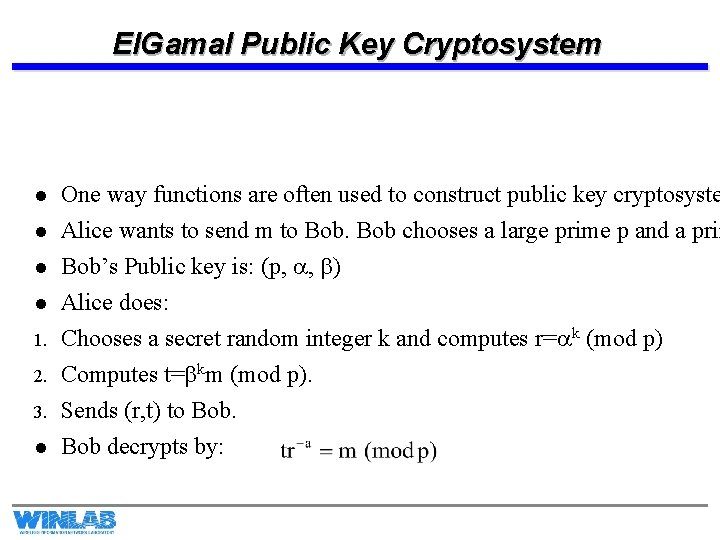

El. Gamal Public Key Cryptosystem l One way functions are often used to construct public key cryptosyste l Alice wants to send m to Bob chooses a large prime p and a prim l Bob’s Public key is: (p, a, b) Alice does: Chooses a secret random integer k and computes r=ak (mod p) Computes t=bkm (mod p). Sends (r, t) to Bob decrypts by: l 1. 2. 3. l

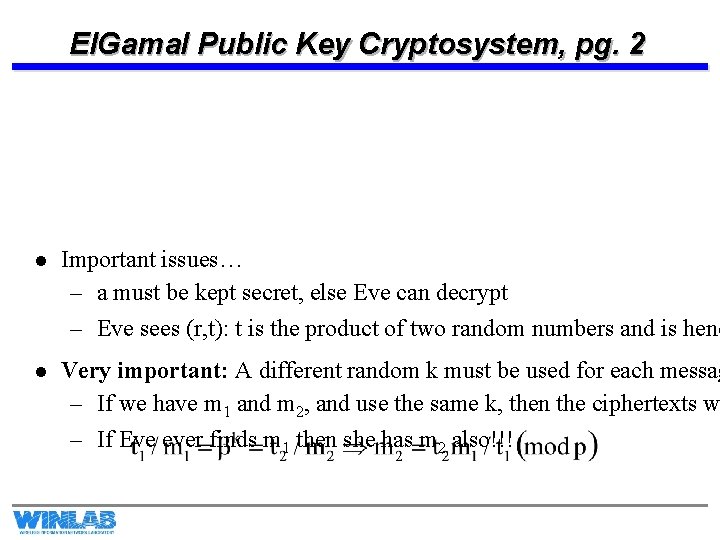

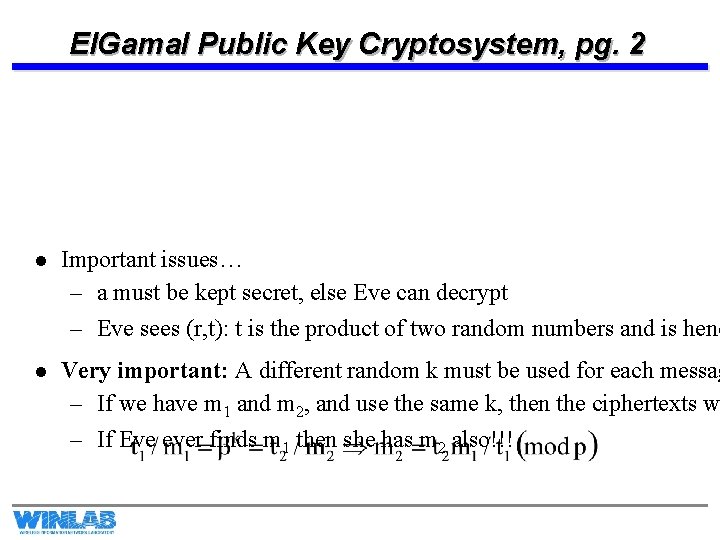

El. Gamal Public Key Cryptosystem, pg. 2 l Important issues… – a must be kept secret, else Eve can decrypt – Eve sees (r, t): t is the product of two random numbers and is henc l Very important: A different random k must be used for each messag – If we have m 1 and m 2, and use the same k, then the ciphertexts w – If Eve ever finds m 1 then she has m 2 also!!!

Overview of Digital Signatures l Suppose you have an electronic document (e. g. a Word file). How do you sign the document to prove to someone that it belongs to you? l You can’t use a scanned signature at the end– this is easy to forge and use elsewhere. l Conventional signing can’t work in the digital world. l We require a digital signature to satisfy: 1. Digital signatures can’t be separated from the message and attached to another message. 2. Signature needs to be verified by others.

An Application for Digital Signatures l Suppose we have two countries, A and B, that have agreed not to test any nuclear bombs (which produce seismic waves when detonated). How can A monitor B by using seismic sensors? 1. The sensors need to be in country B, but A needs to access them. There is a conflict here. 2. Country B wants to make sure that the message sent by the seismic sensor does not contain “other” data (espionage). 3. Country A, however, wants to make sure that the data has not been altered by country B. (Assumption: the sensor itself is tamper proof). How can we solve this problem?

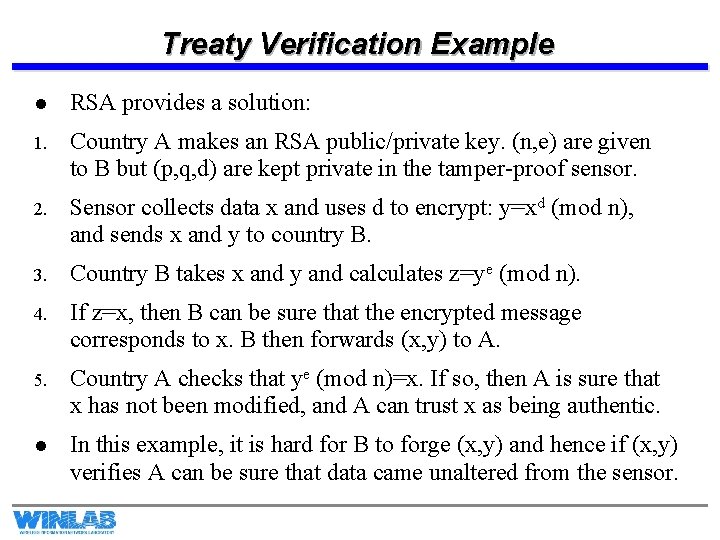

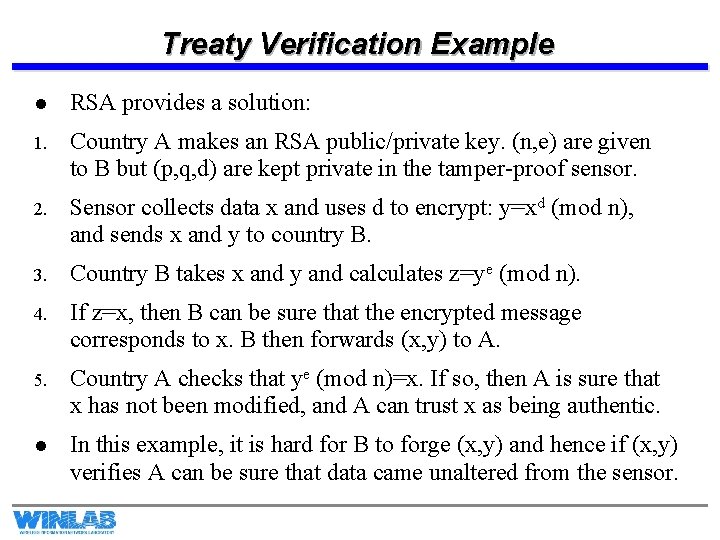

Treaty Verification Example l RSA provides a solution: 1. Country A makes an RSA public/private key. (n, e) are given to B but (p, q, d) are kept private in the tamper-proof sensor. 2. Sensor collects data x and uses d to encrypt: y=xd (mod n), and sends x and y to country B. 3. Country B takes x and y and calculates z=ye (mod n). 4. If z=x, then B can be sure that the encrypted message corresponds to x. B then forwards (x, y) to A. 5. Country A checks that ye (mod n)=x. If so, then A is sure that x has not been modified, and A can trust x as being authentic. l In this example, it is hard for B to forge (x, y) and hence if (x, y) verifies A can be sure that data came unaltered from the sensor.

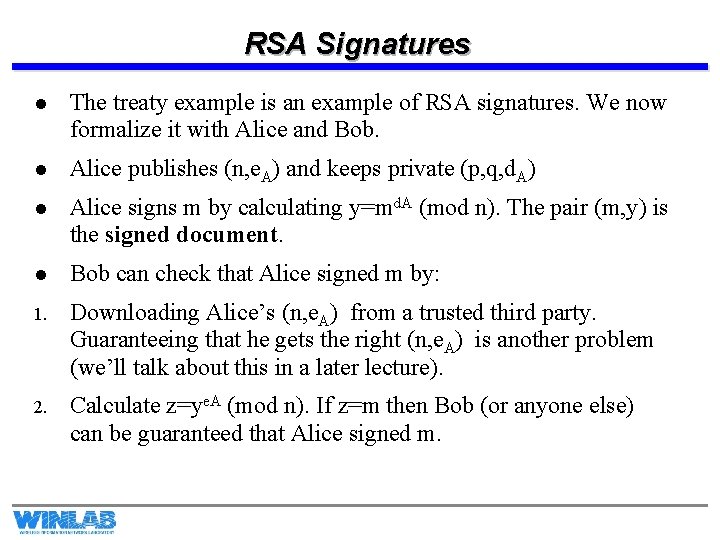

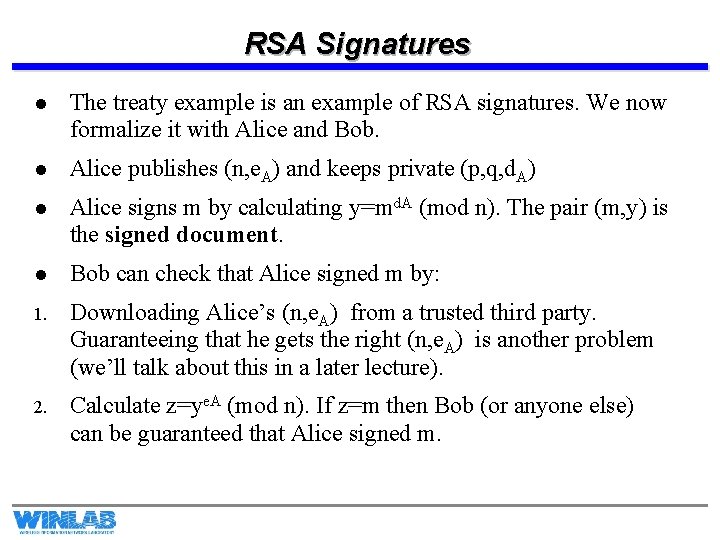

RSA Signatures l The treaty example is an example of RSA signatures. We now formalize it with Alice and Bob. l Alice publishes (n, e. A) and keeps private (p, q, d. A) l Alice signs m by calculating y=md. A (mod n). The pair (m, y) is the signed document. l Bob can check that Alice signed m by: 1. Downloading Alice’s (n, e. A) from a trusted third party. Guaranteeing that he gets the right (n, e. A) is another problem (we’ll talk about this in a later lecture). 2. Calculate z=ye. A (mod n). If z=m then Bob (or anyone else) can be guaranteed that Alice signed m.

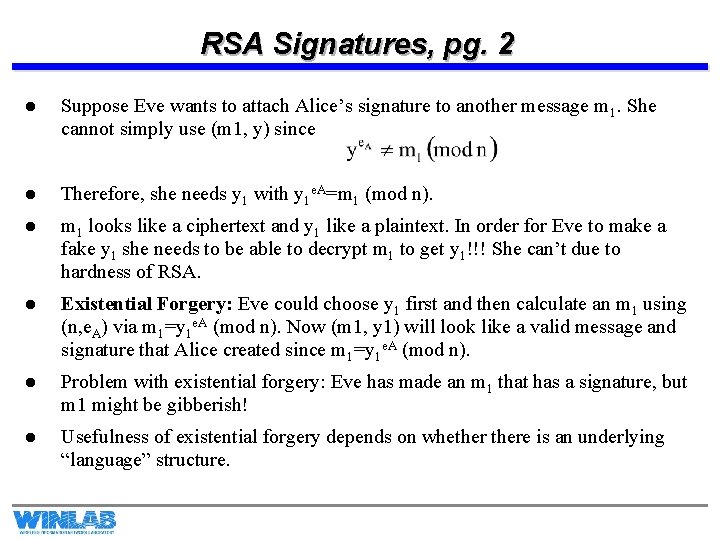

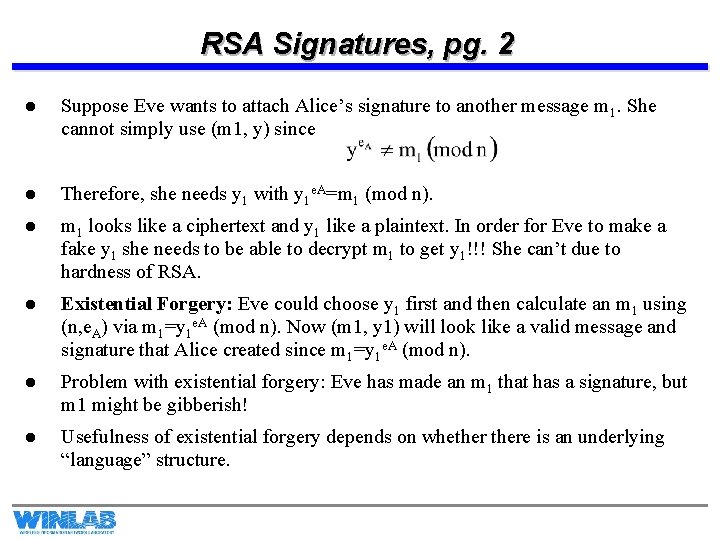

RSA Signatures, pg. 2 l Suppose Eve wants to attach Alice’s signature to another message m 1. She cannot simply use (m 1, y) since l Therefore, she needs y 1 with y 1 e. A=m 1 (mod n). l m 1 looks like a ciphertext and y 1 like a plaintext. In order for Eve to make a fake y 1 she needs to be able to decrypt m 1 to get y 1!!! She can’t due to hardness of RSA. l Existential Forgery: Eve could choose y 1 first and then calculate an m 1 using (n, e. A) via m 1=y 1 e. A (mod n). Now (m 1, y 1) will look like a valid message and signature that Alice created since m 1=y 1 e. A (mod n). l Problem with existential forgery: Eve has made an m 1 that has a signature, but m 1 might be gibberish! l Usefulness of existential forgery depends on whethere is an underlying “language” structure.

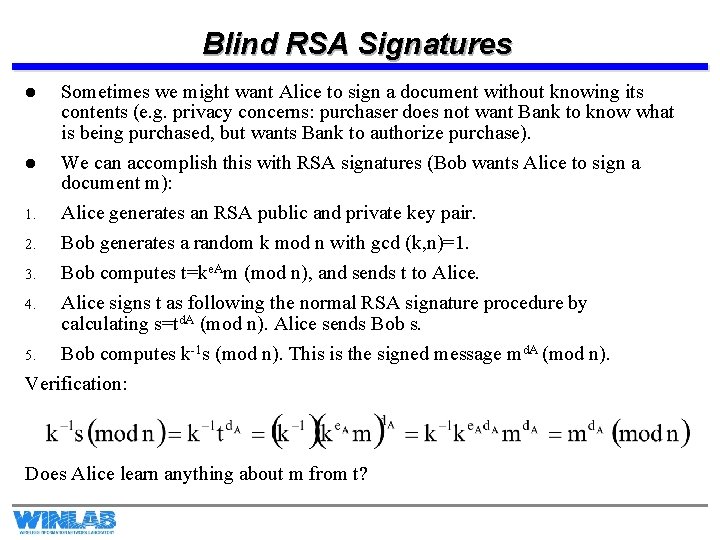

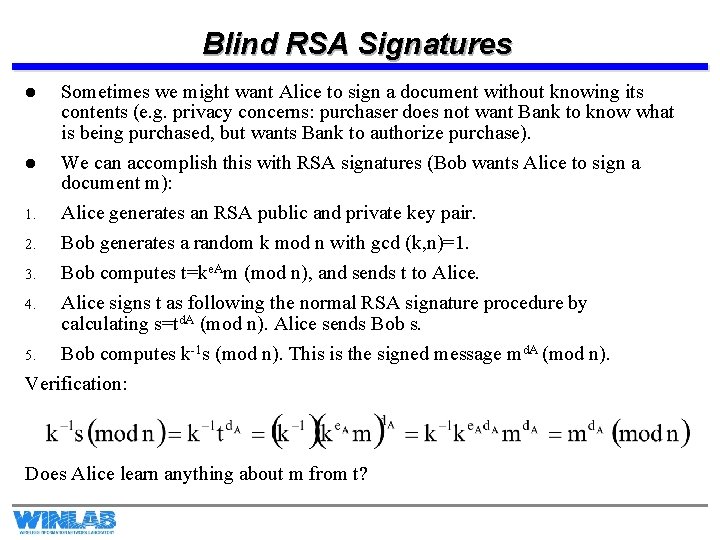

Blind RSA Signatures l l Sometimes we might want Alice to sign a document without knowing its contents (e. g. privacy concerns: purchaser does not want Bank to know what is being purchased, but wants Bank to authorize purchase). We can accomplish this with RSA signatures (Bob wants Alice to sign a document m): Alice generates an RSA public and private key pair. 2. Bob generates a random k mod n with gcd (k, n)=1. 3. Bob computes t=ke. Am (mod n), and sends t to Alice. 4. Alice signs t as following the normal RSA signature procedure by calculating s=td. A (mod n). Alice sends Bob s. 5. Bob computes k-1 s (mod n). This is the signed message md. A (mod n). Verification: 1. Does Alice learn anything about m from t?

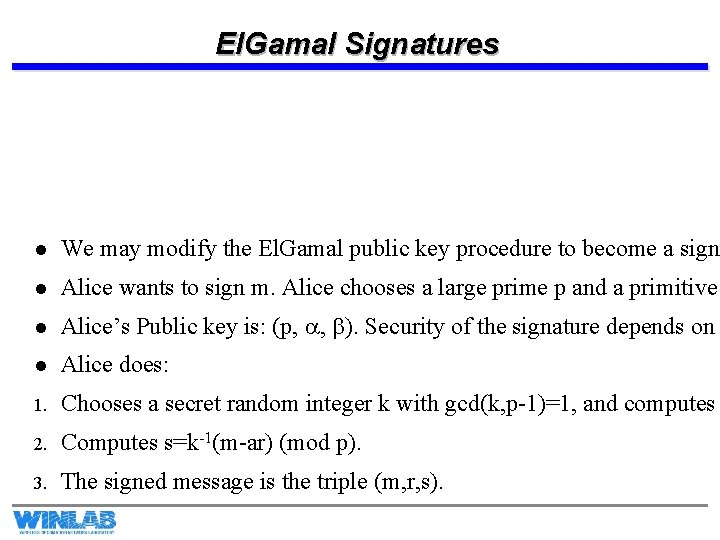

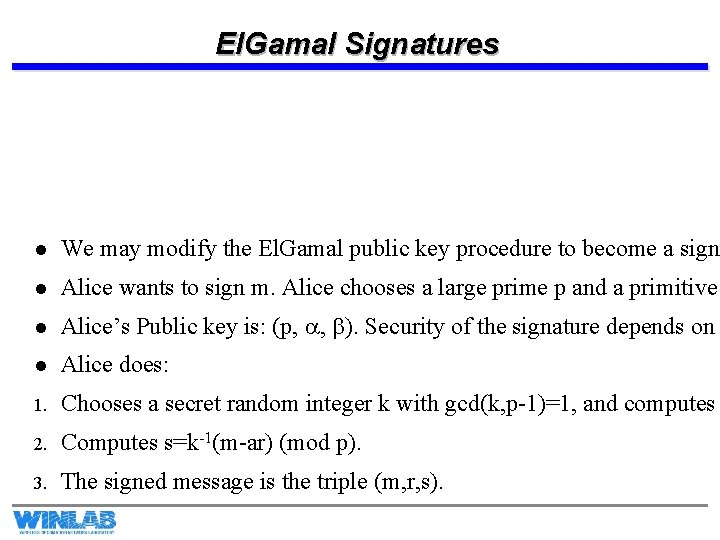

El. Gamal Signatures l We may modify the El. Gamal public key procedure to become a signa l Alice wants to sign m. Alice chooses a large prime p and a primitive l Alice’s Public key is: (p, a, b). Security of the signature depends on l Alice does: 1. Chooses a secret random integer k with gcd(k, p-1)=1, and computes 2. Computes s=k-1(m-ar) (mod p). 3. The signed message is the triple (m, r, s).

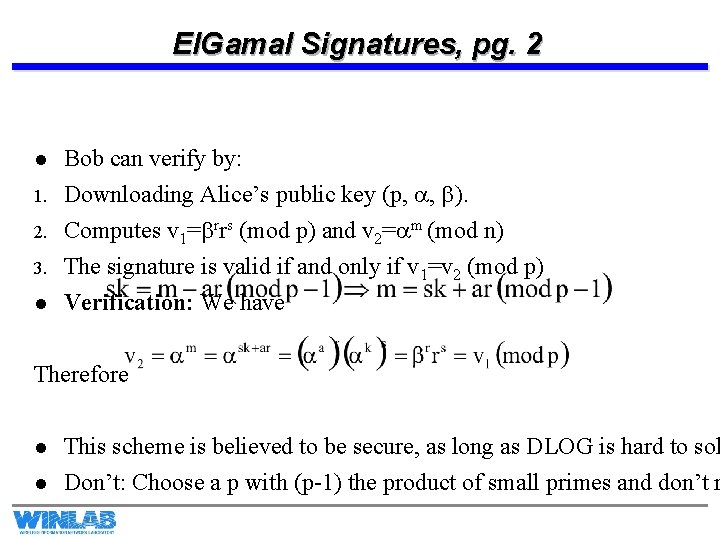

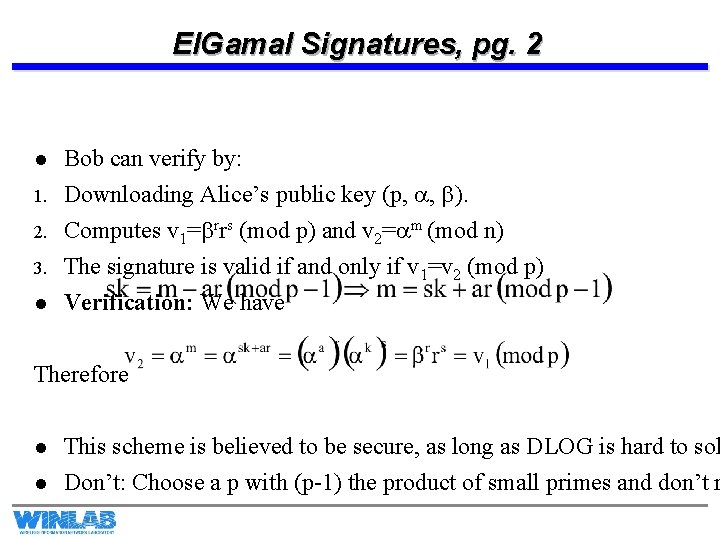

El. Gamal Signatures, pg. 2 l 1. 2. 3. l Bob can verify by: Downloading Alice’s public key (p, a, b). Computes v 1=brrs (mod p) and v 2=am (mod n) The signature is valid if and only if v 1=v 2 (mod p) Verification: We have Therefore l l This scheme is believed to be secure, as long as DLOG is hard to sol Don’t: Choose a p with (p-1) the product of small primes and don’t r

Wastefulness of plain signatures l In signature schemes with appendix, where we attach the signature to the end of the document, we increase the communication overhead. l If we have a long message m=[m 1, m 2, …, m. N], then our signed document is {[m 1, m 2, …, m. N], [sig. A(m 1), …, sig. A(m. N)]}. l This doubles the overhead! l We don’t want to do this when communication resources are precious (which is always!). l Solution: We need to shrink the message into a smaller representation and sign that. l Enter: Hash functions

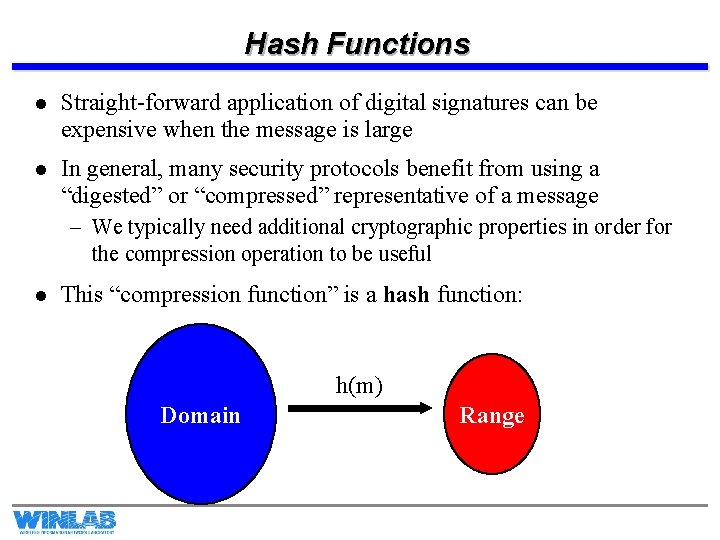

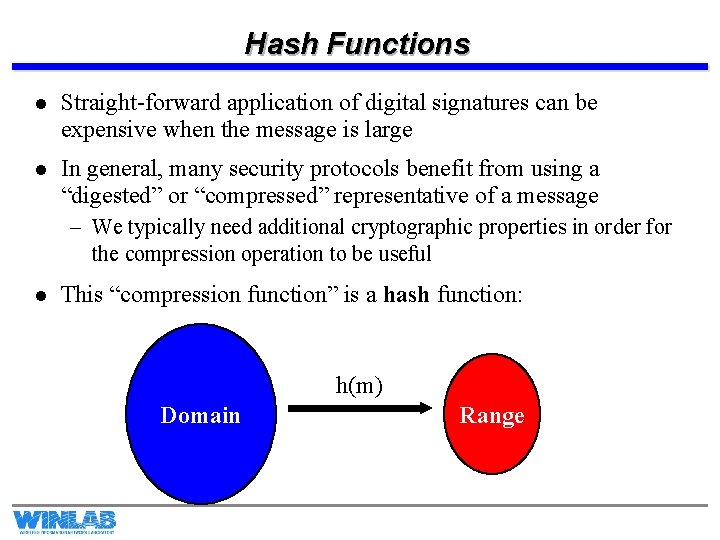

Hash Functions l Straight-forward application of digital signatures can be expensive when the message is large l In general, many security protocols benefit from using a “digested” or “compressed” representative of a message – We typically need additional cryptographic properties in order for the compression operation to be useful l This “compression function” is a hash function: h(m) Domain Range

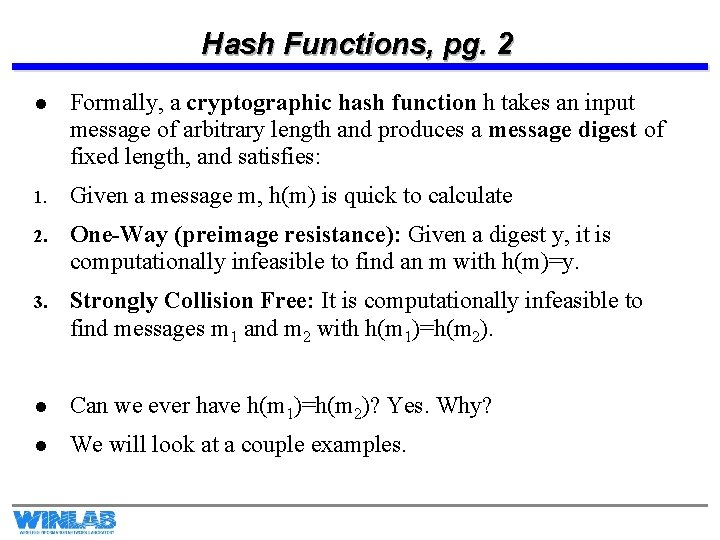

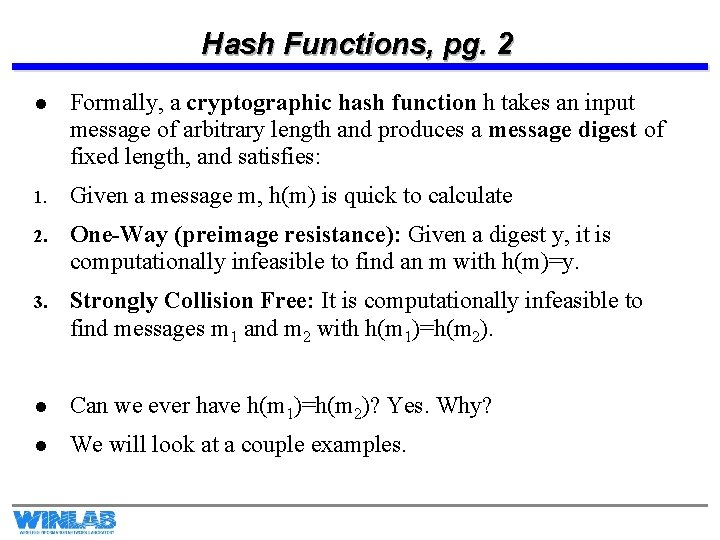

Hash Functions, pg. 2 l Formally, a cryptographic hash function h takes an input message of arbitrary length and produces a message digest of fixed length, and satisfies: 1. Given a message m, h(m) is quick to calculate 2. One-Way (preimage resistance): Given a digest y, it is computationally infeasible to find an m with h(m)=y. 3. Strongly Collision Free: It is computationally infeasible to find messages m 1 and m 2 with h(m 1)=h(m 2). l Can we ever have h(m 1)=h(m 2)? Yes. Why? l We will look at a couple examples.

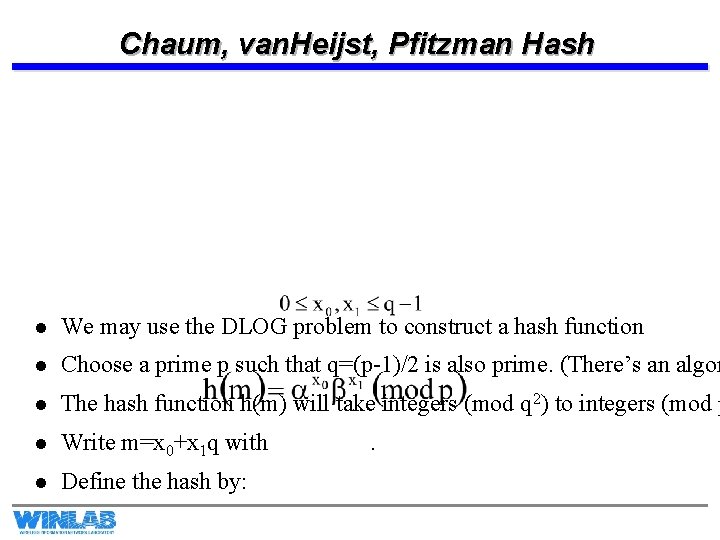

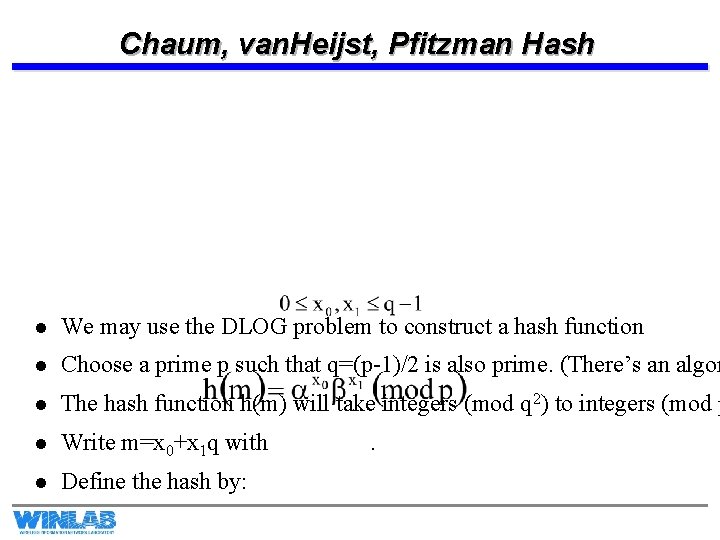

Chaum, van. Heijst, Pfitzman Hash l We may use the DLOG problem to construct a hash function l Choose a prime p such that q=(p-1)/2 is also prime. (There’s an algor l The hash function h(m) will take integers (mod q 2) to integers (mod p l Write m=x 0+x 1 q with l Define the hash by: .

CHP Hash is strongly collision-free l Proposition: If we know with , then we ca l Proof: Will be given on the board after we cover all of the slides.

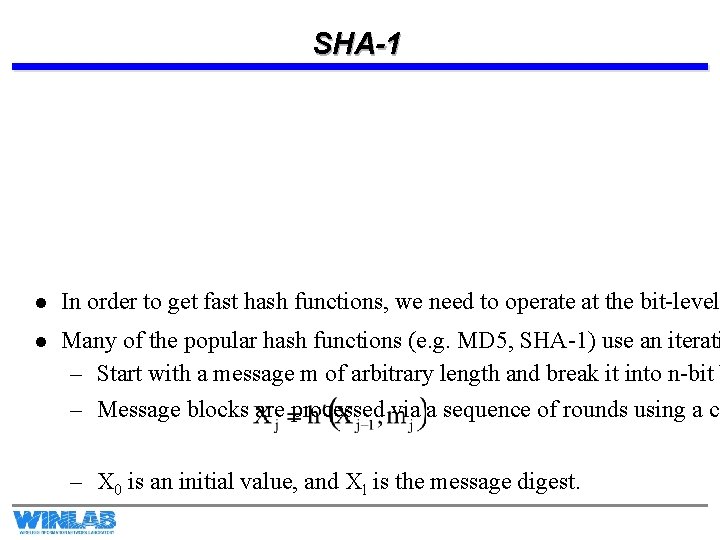

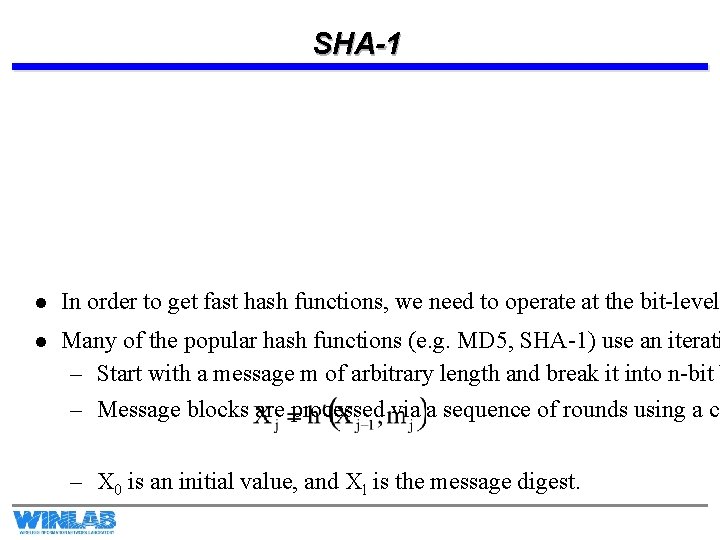

SHA-1 l In order to get fast hash functions, we need to operate at the bit-level. l Many of the popular hash functions (e. g. MD 5, SHA-1) use an iterati – Start with a message m of arbitrary length and break it into n-bit b – Message blocks are processed via a sequence of rounds using a co – X 0 is an initial value, and Xl is the message digest.

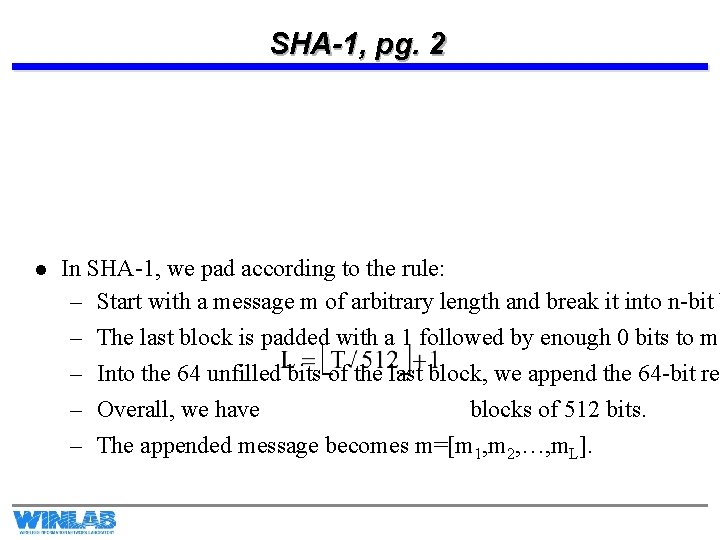

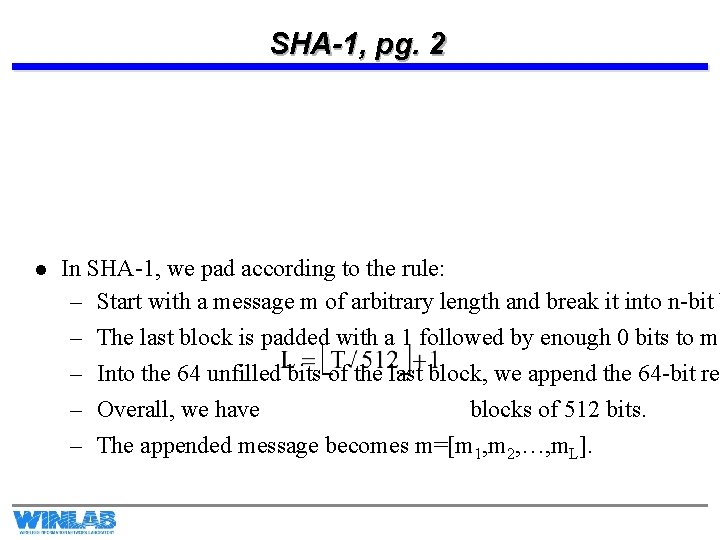

SHA-1, pg. 2 l In SHA-1, we pad according to the rule: – Start with a message m of arbitrary length and break it into n-bit b – – The last block is padded with a 1 followed by enough 0 bits to ma Into the 64 unfilled bits of the last block, we append the 64 -bit re Overall, we have blocks of 512 bits. The appended message becomes m=[m 1, m 2, …, m. L].

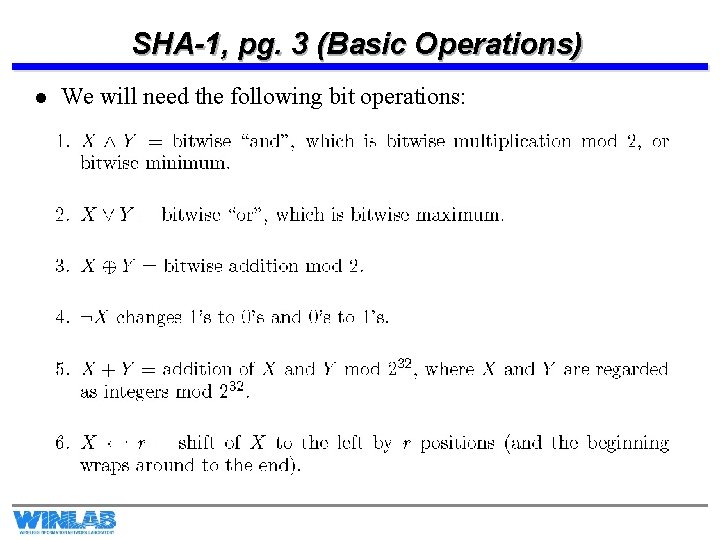

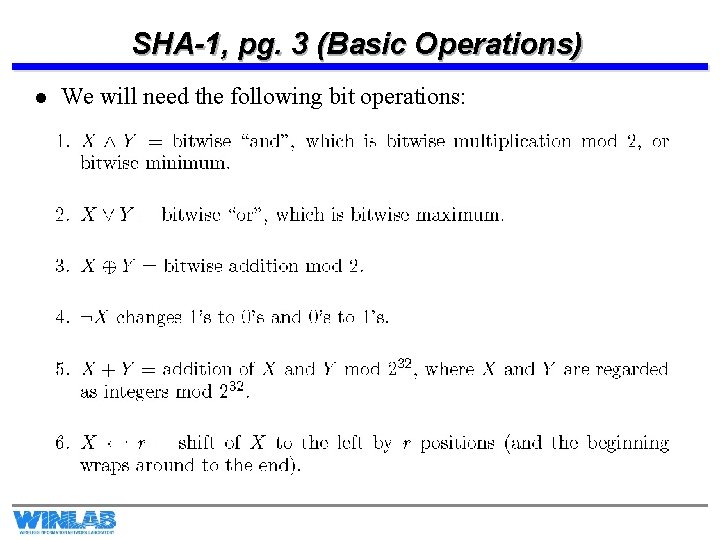

SHA-1, pg. 3 (Basic Operations) l We will need the following bit operations:

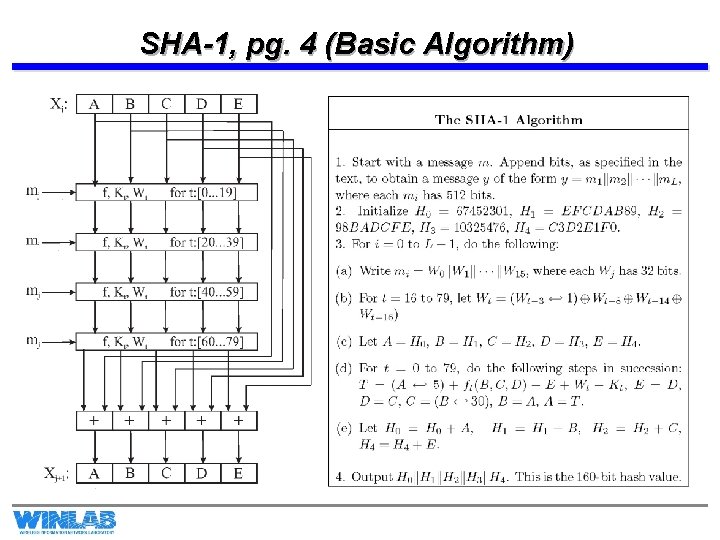

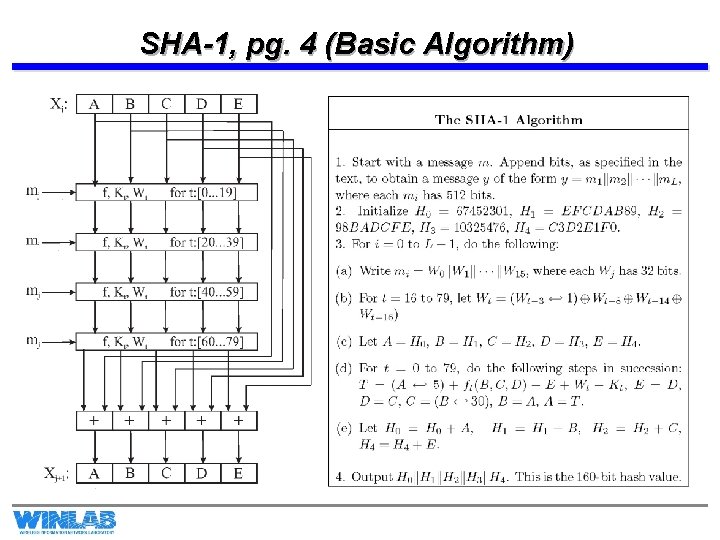

SHA-1, pg. 4 (Basic Algorithm)

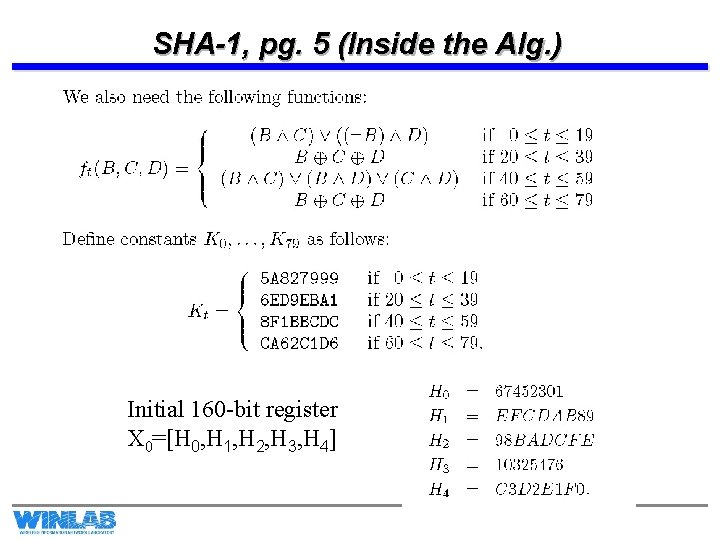

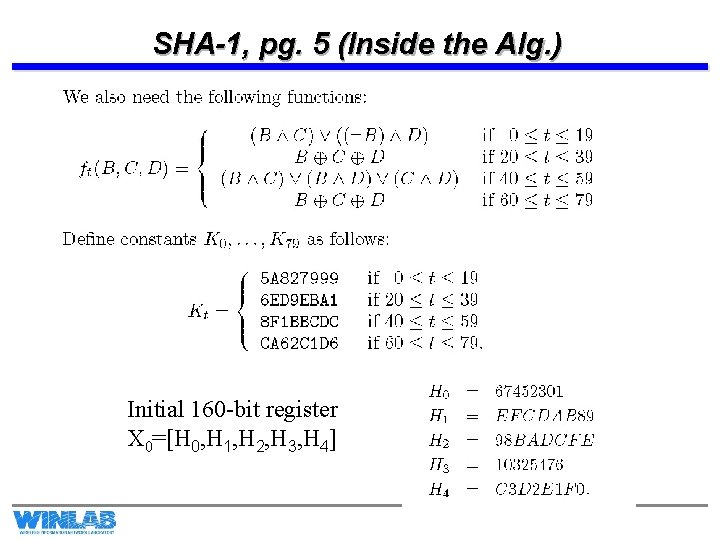

SHA-1, pg. 5 (Inside the Alg. ) Initial 160 -bit register X 0=[H 0, H 1, H 2, H 3, H 4]

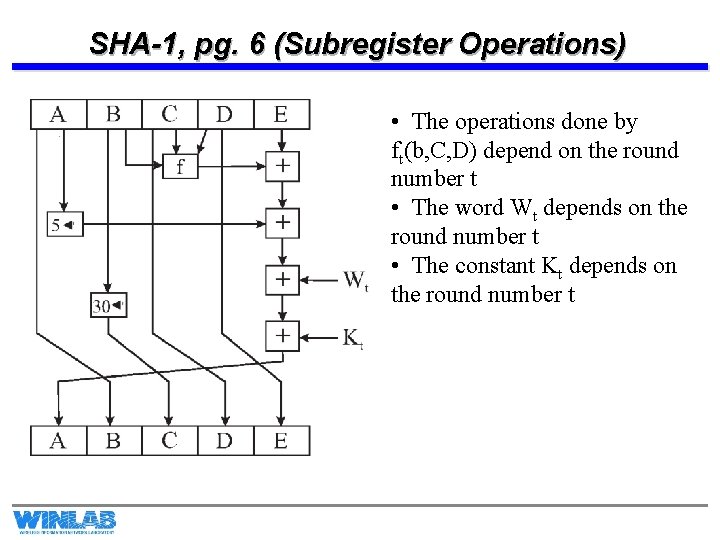

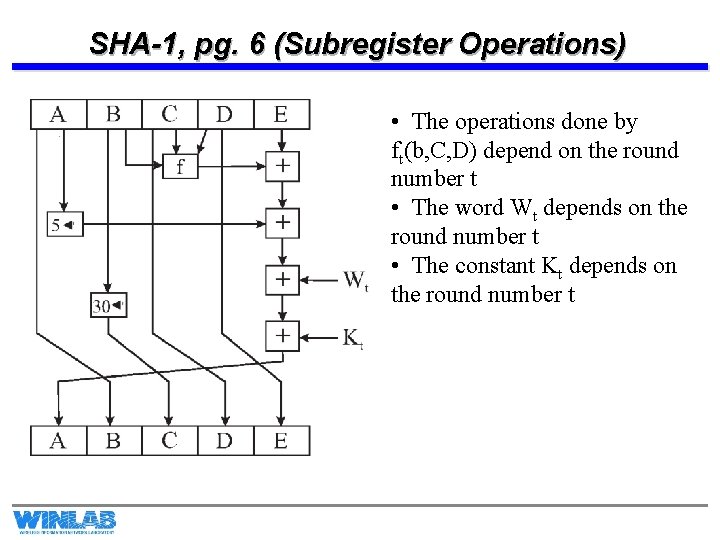

SHA-1, pg. 6 (Subregister Operations) • The operations done by ft(b, C, D) depend on the round number t • The word Wt depends on the round number t • The constant Kt depends on the round number t

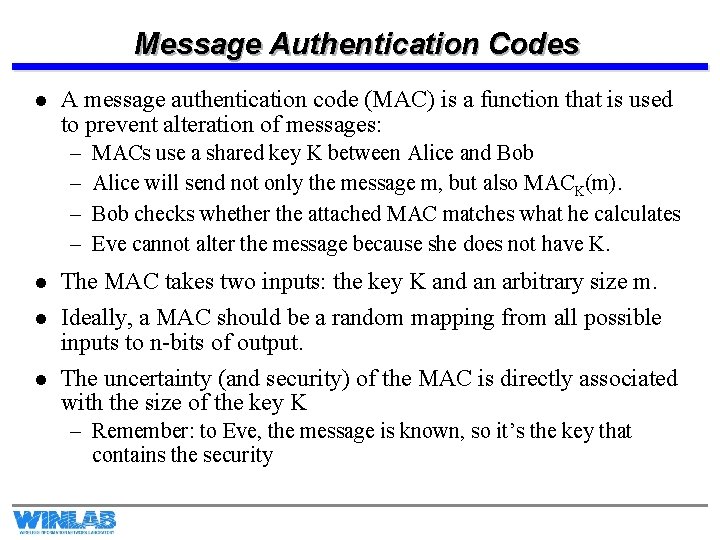

Message Authentication Codes l A message authentication code (MAC) is a function that is used to prevent alteration of messages: – – l l l MACs use a shared key K between Alice and Bob Alice will send not only the message m, but also MACK(m). Bob checks whether the attached MAC matches what he calculates Eve cannot alter the message because she does not have K. The MAC takes two inputs: the key K and an arbitrary size m. Ideally, a MAC should be a random mapping from all possible inputs to n-bits of output. The uncertainty (and security) of the MAC is directly associated with the size of the key K – Remember: to Eve, the message is known, so it’s the key that contains the security

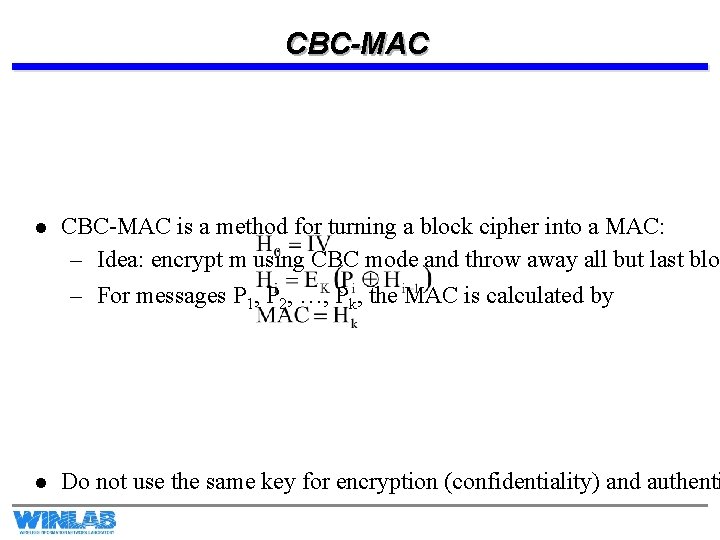

CBC-MAC l CBC-MAC is a method for turning a block cipher into a MAC: – Idea: encrypt m using CBC mode and throw away all but last blo – For messages P 1, P 2, …, Pk, the MAC is calculated by l Do not use the same key for encryption (confidentiality) and authenti

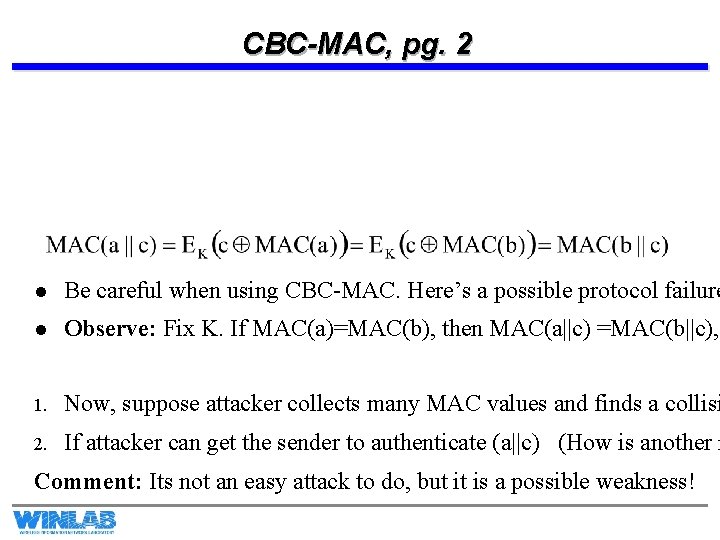

CBC-MAC, pg. 2 l Be careful when using CBC-MAC. Here’s a possible protocol failure l Observe: Fix K. If MAC(a)=MAC(b), then MAC(a||c) =MAC(b||c), 1. Now, suppose attacker collects many MAC values and finds a collisi 2. If attacker can get the sender to authenticate (a||c) (How is another m Comment: Its not an easy attack to do, but it is a possible weakness!

CBC-MAC, pg. 3 l Practical Implementation Details: 1. Generally, if your message is m, do not just calculate MAC(m), rather you should make an intermediate message s=(l||m), where l is the length of m in a fixed-length format. 2. Pad s to be a multiple of block size 3. Apply CBC-MAC to the padded string s 4. Output the last ciphertext block. Do not output any intermediate block values! l CBC-MAC can reuse same code as confidentiality (encryption) functions l CBC-MAC is generally tough to use correctly, though.

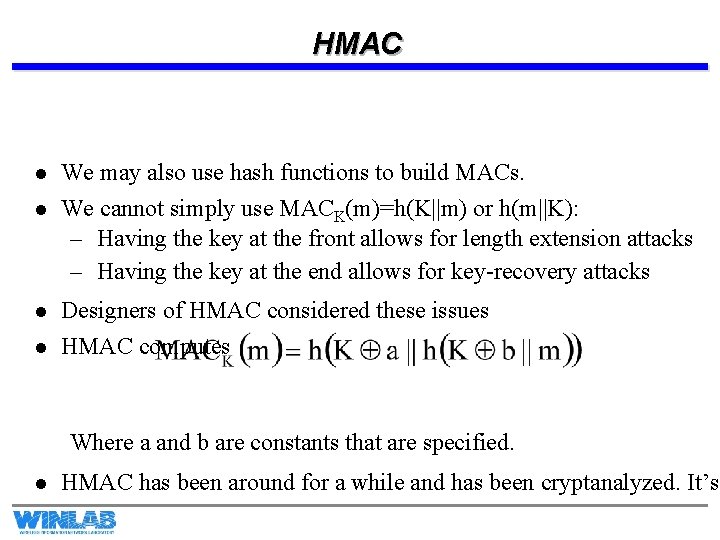

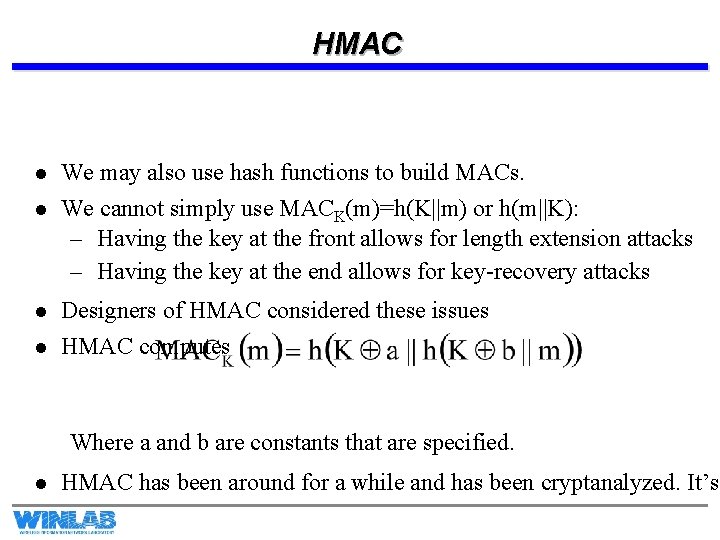

HMAC l We may also use hash functions to build MACs. l We cannot simply use MACK(m)=h(K||m) or h(m||K): – Having the key at the front allows for length extension attacks – Having the key at the end allows for key-recovery attacks l Designers of HMAC considered these issues HMAC computes l Where a and b are constants that are specified. l HMAC has been around for a while and has been cryptanalyzed. It’s

Using MACs l We must be careful using MACs. l If Alice sends Bob [m||MACK(m)] and Eve records this, she may send it again at a later time (the replay attack!) l Generally, you want to authenticate not just the message, but the context. That is, you want to authenticate m and additional data d (such as message number, source, destination, protocol identifier, sizes for different fields, etc. ) l Why all these possibilities? If you tie the message to the specific context, then it is harder for an adversary to manipulate context fields to forge. l Make certain, though, that you have clear rules on how to split concatenations (d||m) back into d and m.

Problems with Hashes l We must be careful when using hash functions, they are subject to some “attacks” l Length Extension Attack: Consider a block-based hash like SHA-1, with input bl A new message m’ =(m 1, m 2, …, mk+1), will have hash h(m’)=h’(h(m), mk+1), wher In systems, such as authentication applications, where we calculate h(X||m), Eve can a l Partial Message Collision Attack: Suppose we are able to find m and m’ such tha An adversary can replace m with m’ during authentication. l In general hashing practice, we really use f(m)= h(h(m)||m) or f(m)=h(h(m)) as the