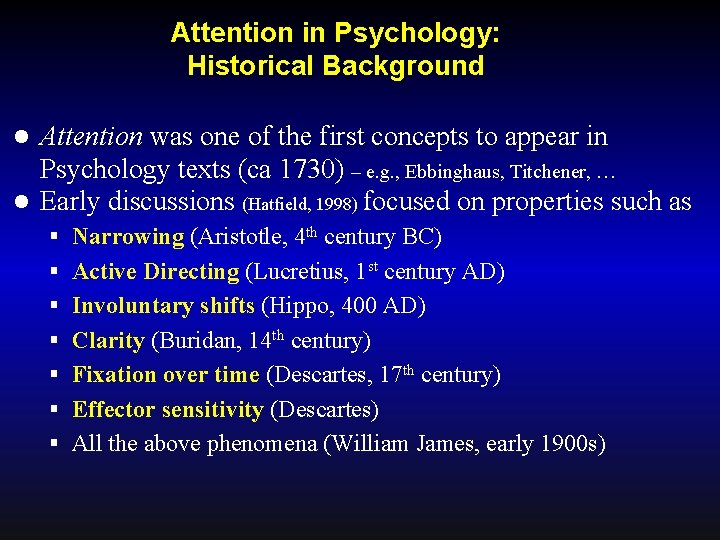

Attention in Psychology Historical Background Attention was one

Attention in Psychology: Historical Background Attention was one of the first concepts to appear in Psychology texts (ca 1730) – e. g. , Ebbinghaus, Titchener, … l Early discussions (Hatfield, 1998) focused on properties such as l § Narrowing (Aristotle, 4 th century BC) § Active Directing (Lucretius, 1 st century AD) § Involuntary shifts (Hippo, 400 AD) § Clarity (Buridan, 14 th century) § Fixation over time (Descartes, 17 th century) § Effector sensitivity (Descartes) § All the above phenomena (William James, early 1900 s)

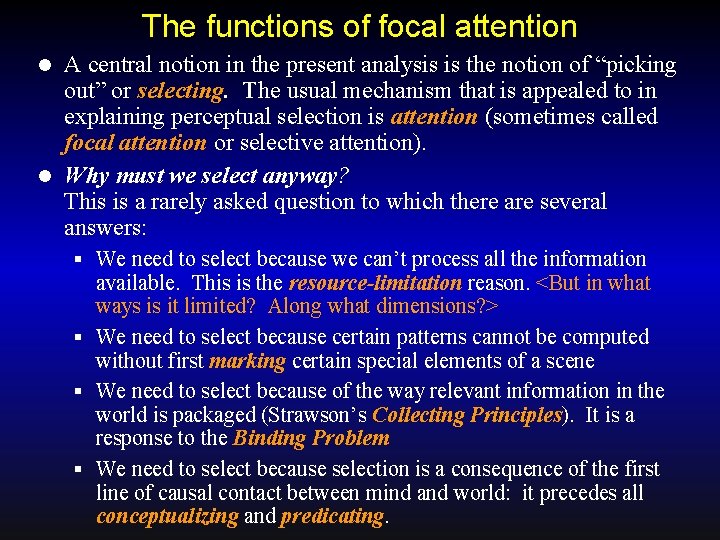

The functions of focal attention A central notion in the present analysis is the notion of “picking out” or selecting. The usual mechanism that is appealed to in explaining perceptual selection is attention (sometimes called focal attention or selective attention). l Why must we select anyway? This is a rarely asked question to which there are several answers: l § We need to select because we can’t process all the information available. This is the resource-limitation reason. <But in what ways is it limited? Along what dimensions? > § We need to select because certain patterns cannot be computed without first marking certain special elements of a scene § We need to select because of the way relevant information in the world is packaged (Strawson’s Collecting Principles). It is a response to the Binding Problem § We need to select because selection is a consequence of the first line of causal contact between mind and world: it precedes all conceptualizing and predicating.

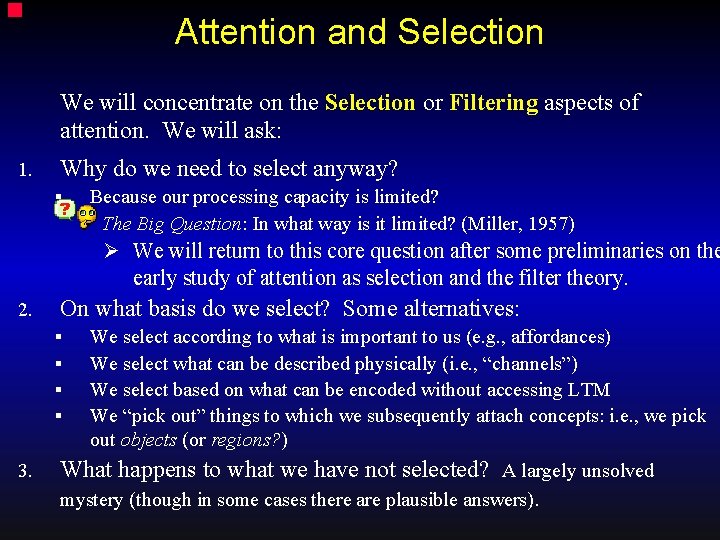

Attention and Selection We will concentrate on the Selection or Filtering aspects of attention. We will ask: 1. Why do we need to select anyway? § Because our processing capacity is limited? The Big Question: In what way is it limited? (Miller, 1957) Ø We will return to this core question after some preliminaries on the early study of attention as selection and the filter theory. 2. On what basis do we select? Some alternatives: § § 3. We select according to what is important to us (e. g. , affordances) We select what can be described physically (i. e. , “channels”) We select based on what can be encoded without accessing LTM We “pick out” things to which we subsequently attach concepts: i. e. , we pick out objects (or regions? ) What happens to what we have not selected? A largely unsolved mystery (though in some cases there are plausible answers).

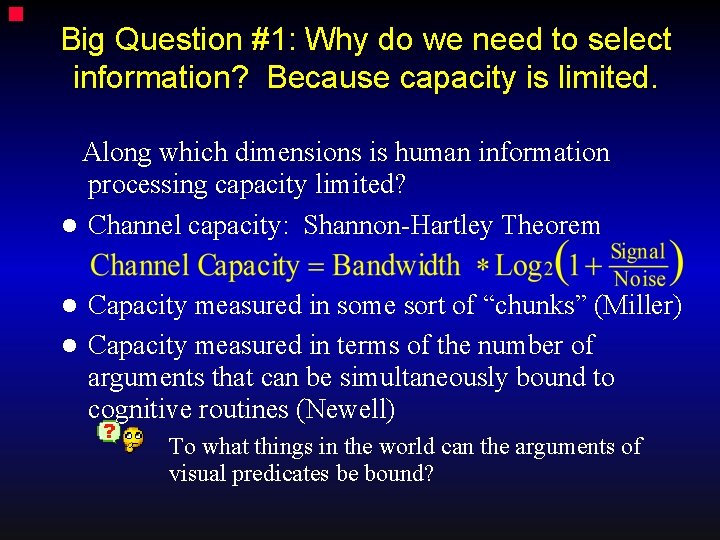

Big Question #1: Why do we need to select information? Because capacity is limited. Along which dimensions is human information processing capacity limited? l Channel capacity: Shannon-Hartley Theorem Capacity measured in some sort of “chunks” (Miller) l Capacity measured in terms of the number of arguments that can be simultaneously bound to cognitive routines (Newell) l To what things in the world can the arguments of visual predicates be bound?

Amount of information in terms of the Information-theoretic measure (entropy) Amount of information in a signal depends on how much one’s estimate of the probability of events is changed by the signal. H = - pi Log 2 (pi) … information in bits l “One of by land, two if by sea” contains one bit of information if the two possibilities were equally likely, less if they were not (e. g. , if one was twice as likely as the other the information in the message would be ⅓ Log ⅓ + ⅔ Log ⅔ = 0. 92 bits <using Excel>) l The amount of information transmitted depends on the potential amount of information in the message and the amount of correlation between message sent and message received. So information transmitted is a type of I-O correlation measure. l The information measure is an “ideal receiver” or competence measure. It is the maximum information that could be transmitted, given the statistical properties of messages, assuming that the sender and receiver know the code. l

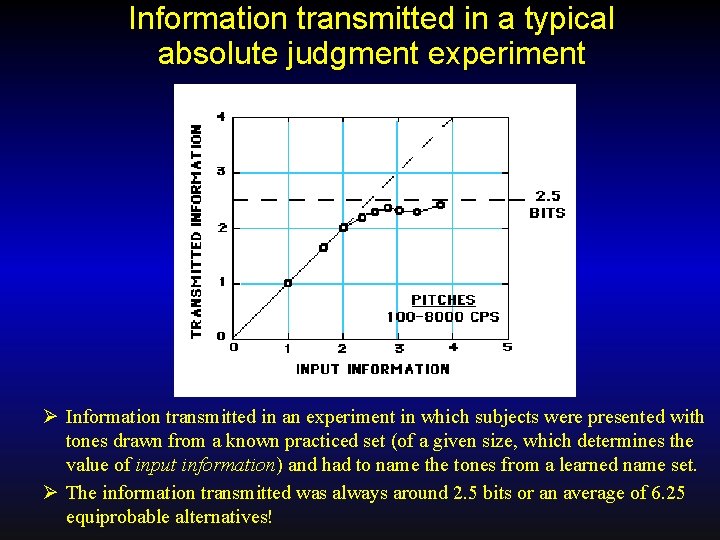

Information transmitted in a typical absolute judgment experiment Ø Information transmitted in an experiment in which subjects were presented with tones drawn from a known practiced set (of a given size, which determines the value of input information) and had to name the tones from a learned name set. Ø The information transmitted was always around 2. 5 bits or an average of 6. 25 equiprobable alternatives!

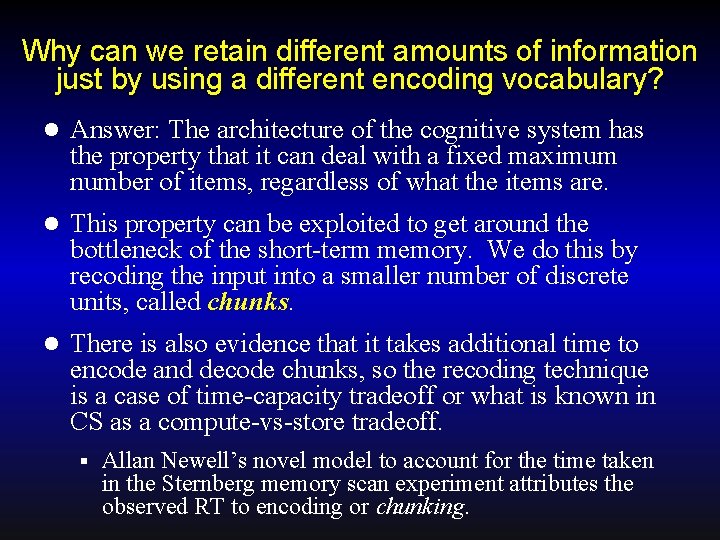

Why can we retain different amounts of information just by using a different encoding vocabulary? l Answer: The architecture of the cognitive system has the property that it can deal with a fixed maximum number of items, regardless of what the items are. l This property can be exploited to get around the bottleneck of the short-term memory. We do this by recoding the input into a smaller number of discrete units, called chunks. l There is also evidence that it takes additional time to encode and decode chunks, so the recoding technique is a case of time-capacity tradeoff or what is known in CS as a compute-vs-store tradeoff. § Allan Newell’s novel model to account for the time taken in the Sternberg memory scan experiment attributes the observed RT to encoding or chunking.

Example of the use of chunking • To recall a string of binary bits – e. g. , 00101110110101001 • People can recall a string of about 8 binary integers. If they learn a binary encoding rule (00 0, 01 1, 10 2, 11 3) they can recall about 8 such chunks or 18 binary bits. If they learn a 3: 1 chunking rule (called the Octal number system) they can recall a 24 bit string, etc

Early studies: Colin Cherry’s “Cocktail Party Problem” l What determines how well you can select one conversation among several? Why are we so good at it? l The more controlled version of this study used dichotic presentations – one “channel” per ear. l Cherry found that when attention is fully occupied in selecting information from one ear (through use of the “shadowing” task), almost nothing is noticed in the “rejected” ear (only if it was not speech). l More careful observations shows this was not quite true § Change in spectral properties (pitch) is noticed § You are likely to notice your name spoken § Even meaning is extracted, as shown by involuntary ear switching and disambiguating effect of rejected channel content

Broadbent’s Filter Theory Effectors Motor planner Filter Very Short Term Store Senses Rehearsal loop Limited Capacity Channel Store of conditional probabilities of past events (in LTM) Broadbent, D. E. (1958). Perception and Communication. London: Pergamon Press.

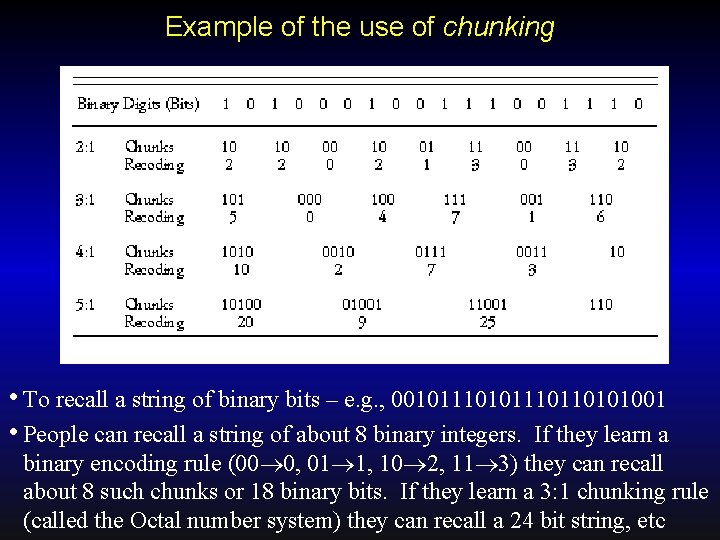

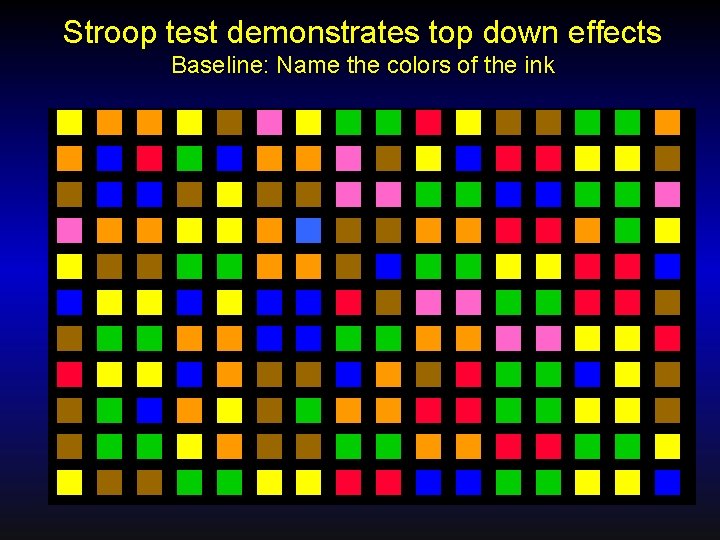

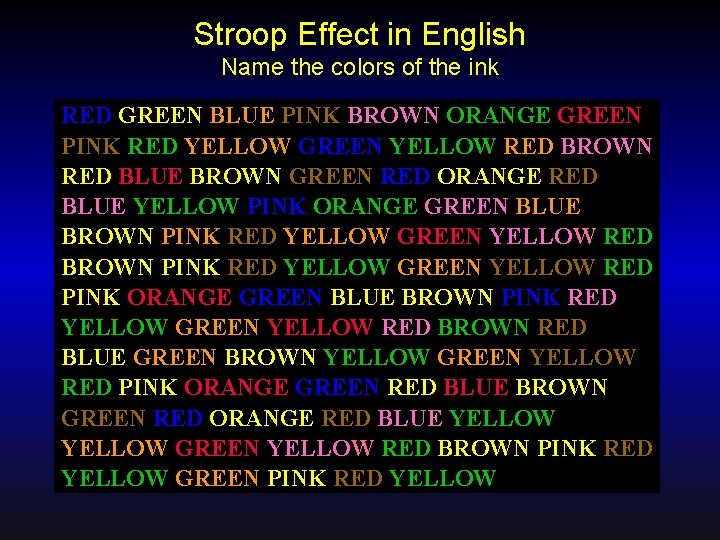

Stroop test demonstrates top down effects Baseline: Name the colors of the ink

Stroop Effect in English Name the colors of the ink RED GREEN BLUE PINK BROWN ORANGE GREEN PINK RED YELLOW GREEN YELLOW RED BROWN RED BLUE BROWN GREEN RED ORANGE RED BLUE YELLOW PINK ORANGE GREEN BLUE BROWN PINK RED YELLOW GREEN YELLOW RED BROWN RED BLUE GREEN BROWN YELLOW GREEN YELLOW RED PINK ORANGE GREEN RED BLUE BROWN GREEN RED ORANGE RED BLUE YELLOW GREEN YELLOW RED BROWN PINK RED YELLOW GREEN PINK RED YELLOW

Stroop Effect in Spanish Name the colors of the ink TINTO VERDE AZUL MARROM ROSA NARANJA VERDE ROSA TINTO AMARELO VERDE AMARELO TINTO MARROM TINTO AZUL MARROM VERDE TINTO NARANJA TINTO AZUL AMARELO ROSA NARANJA VERDE AZUL MARROM ROSA TINTO AMARELO VERDE AMARELO TINTO MARROM TINTO AZUL MARROM VERDE AMARELO TINTO ROSA NARANJA VERDE TINTO AZUL MARROM VERDE TINTO NARANJA TINTO AZUL TINTO NARANJA AMARELO VERDE ROSA AMARELO VERDE AMARELO TINTO AZUL NARANJA

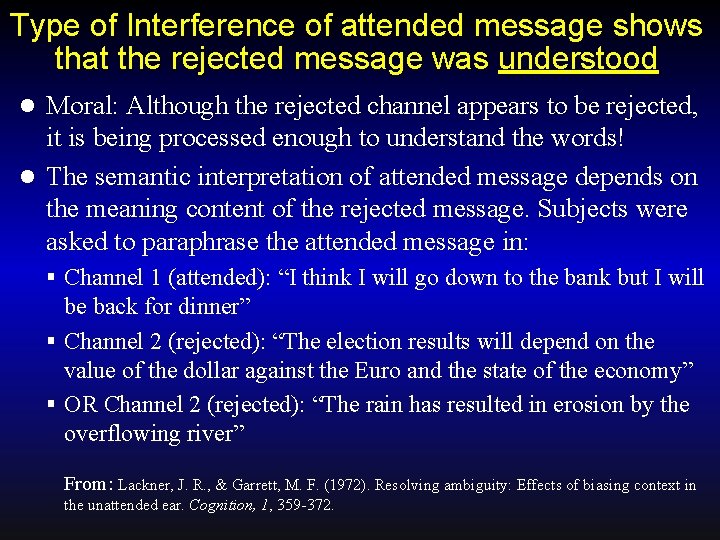

Type of Interference of attended message shows that the rejected message was understood Moral: Although the rejected channel appears to be rejected, it is being processed enough to understand the words! l The semantic interpretation of attended message depends on the meaning content of the rejected message. Subjects were asked to paraphrase the attended message in: l § Channel 1 (attended): “I think I will go down to the bank but I will be back for dinner” § Channel 2 (rejected): “The election results will depend on the value of the dollar against the Euro and the state of the economy” § OR Channel 2 (rejected): “The rain has resulted in erosion by the overflowing river” From: Lackner, J. R. , & Garrett, M. F. (1972). Resolving ambiguity: Effects of biasing context in the unattended ear. Cognition, 1, 359 -372.

From here on I will focus on the special case of visual attention Visual working memory and visual selection l What is the nature of the input, storage and information processing limits in vision? l

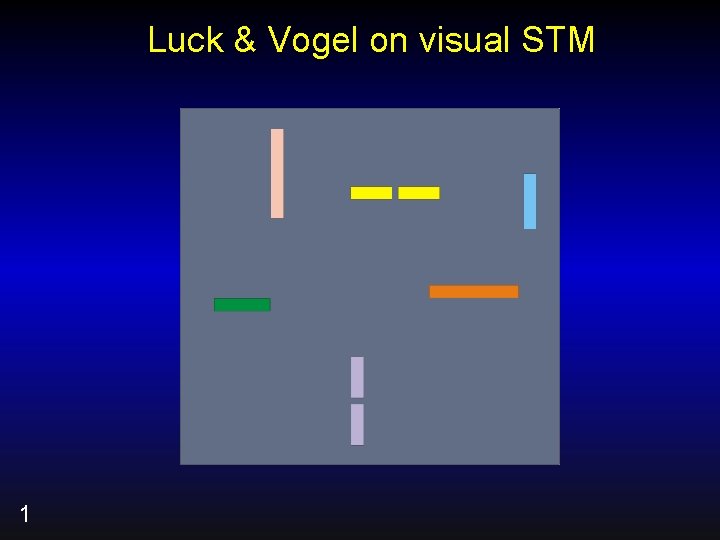

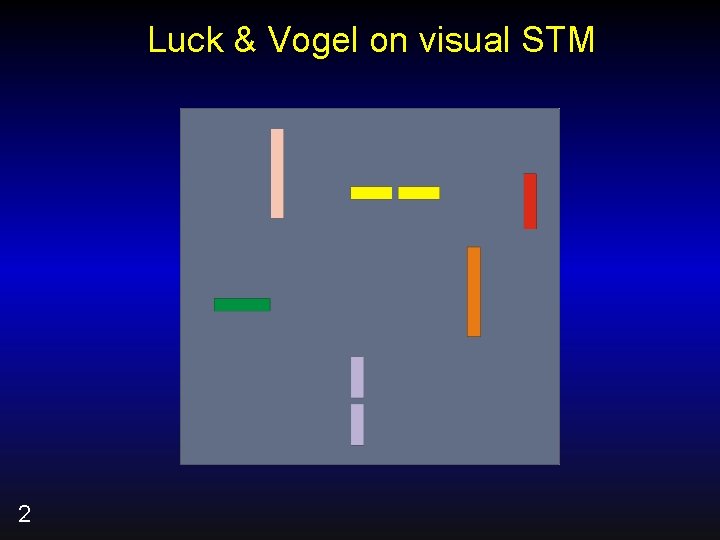

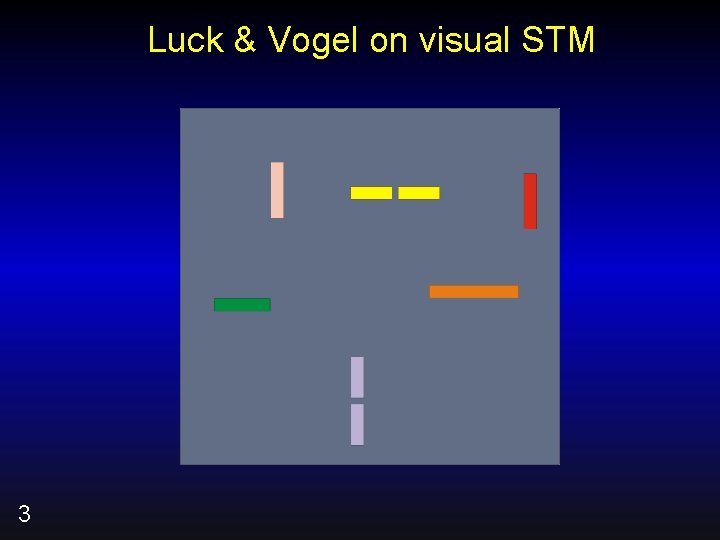

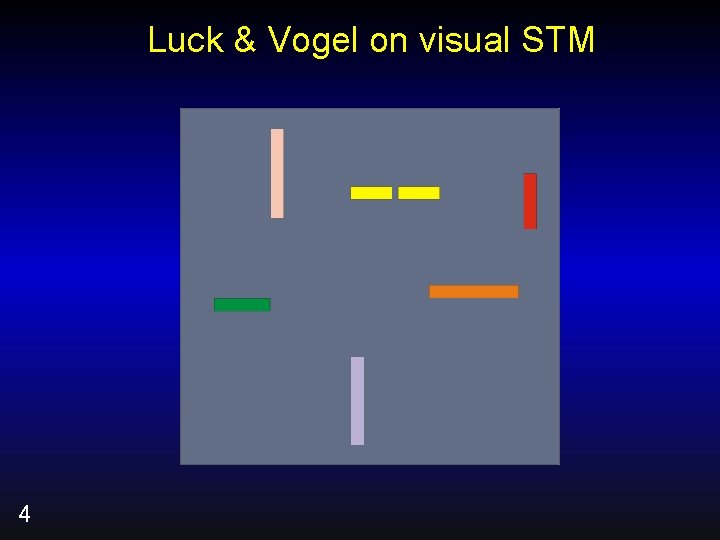

Studies of the capacity of Visual Working Memory (Luck & Vogel, 1997) l People appear to be able to retain about 4 properties of an object (4 colors, 4 shapes, 4 orientations, etc) over a short time l People can also retain the identity of 4 objects for a short time. l Luck and Vogel (1997) found that as long as there are not more than 4 properties per object, people can retain large numbers of properties when the properties are on different objects (a phenomenon that is reminiscent of Miller’s “chunking hypothesis” except the chunks are visual objects). * Luck, S. , & Vogel, E. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390, 279 -281.

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 1

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 1

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 2

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 2

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 3

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 3

Luck & Vogel on visual STM 4

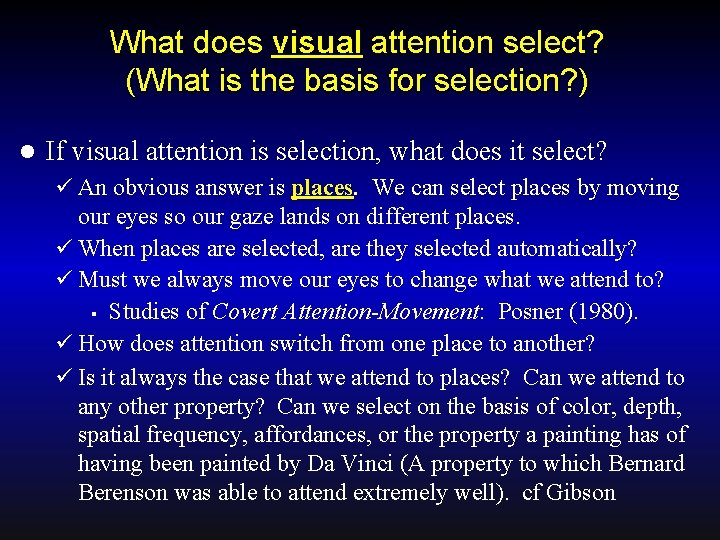

What does visual attention select? (What is the basis for selection? ) l If visual attention is selection, what does it select? ü An obvious answer is places. We can select places by moving our eyes so our gaze lands on different places. ü When places are selected, are they selected automatically? ü Must we always move our eyes to change what we attend to? § Studies of Covert Attention-Movement: Posner (1980). ü How does attention switch from one place to another? ü Is it always the case that we attend to places? Can we attend to any other property? Can we select on the basis of color, depth, spatial frequency, affordances, or the property a painting has of having been painted by Da Vinci (A property to which Bernard Berenson was able to attend extremely well). cf Gibson

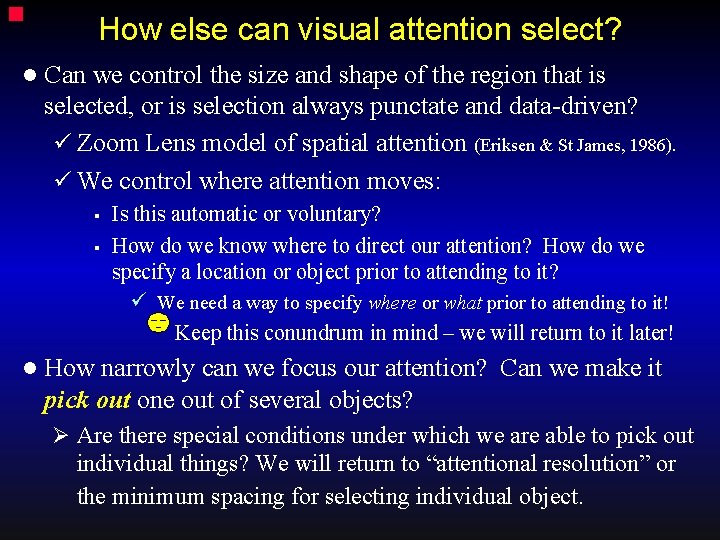

How else can visual attention select? l Can we control the size and shape of the region that is selected, or is selection always punctate and data-driven? ü Zoom Lens model of spatial attention (Eriksen & St James, 1986). ü We control where attention moves: § § Is this automatic or voluntary? How do we know where to direct our attention? How do we specify a location or object prior to attending to it? ü We need a way to specify where or what prior to attending to it! Keep this conundrum in mind – we will return to it later! l How narrowly can we focus our attention? Can we make it pick out one out of several objects? Ø Are there special conditions under which we are able to pick out individual things? We will return to “attentional resolution” or the minimum spacing for selecting individual object.

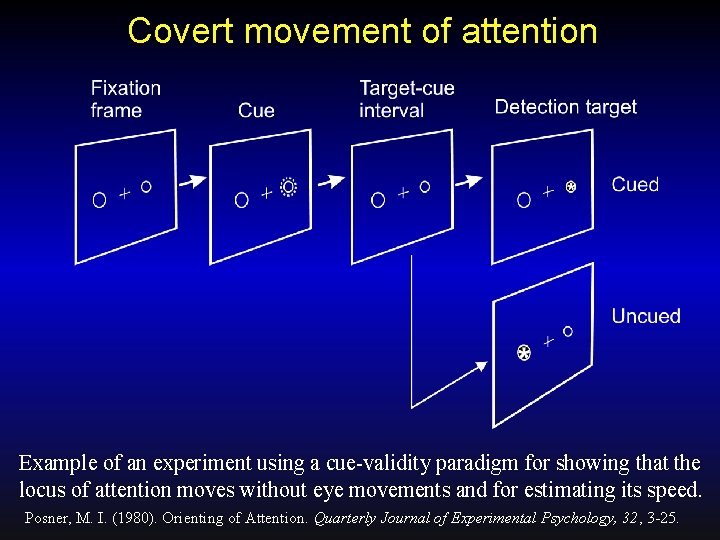

Covert movement of attention Example of an experiment using a cue-validity paradigm for showing that the locus of attention moves without eye movements and for estimating its speed. Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of Attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3 -25.

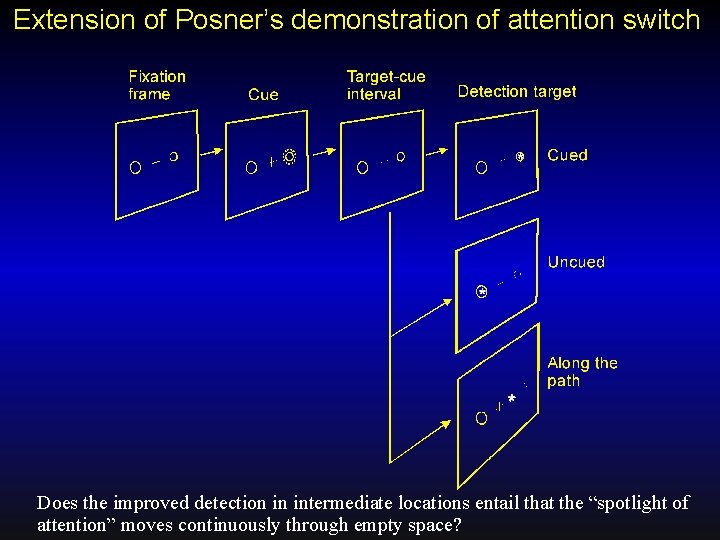

Extension of Posner’s demonstration of attention switch Does the improved detection in intermediate locations entail that the “spotlight of attention” moves continuously through empty space?

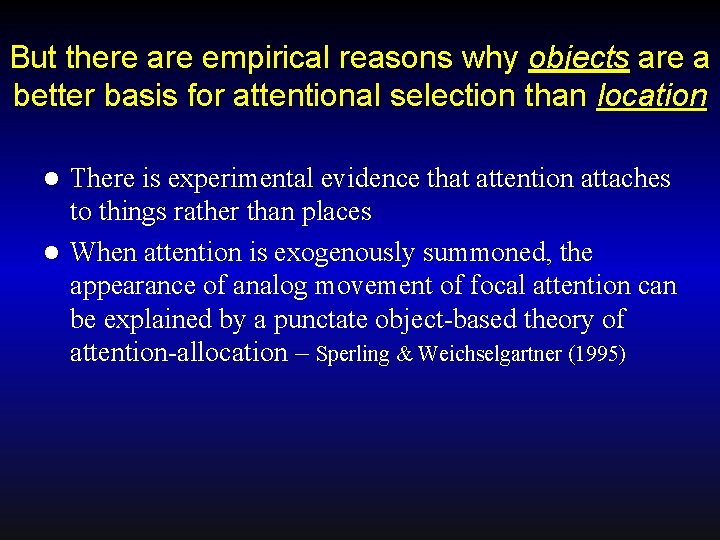

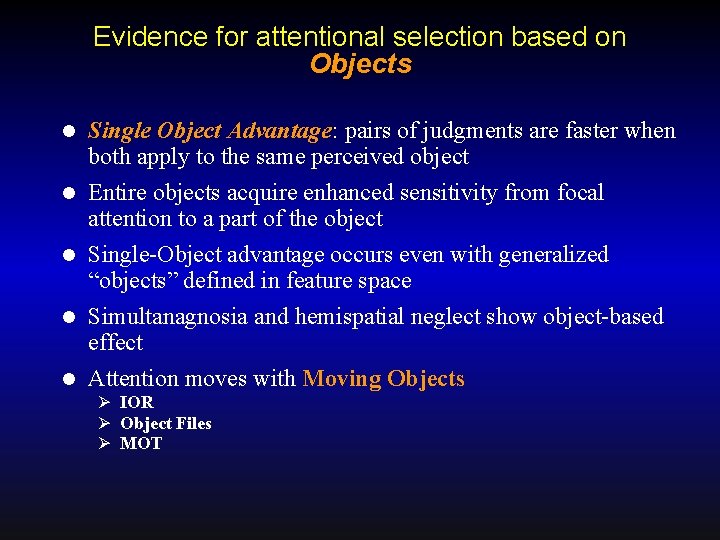

But there are empirical reasons why objects are a better basis for attentional selection than location There is experimental evidence that attention attaches to things rather than places l When attention is exogenously summoned, the appearance of analog movement of focal attention can be explained by a punctate object-based theory of attention-allocation – Sperling & Weichselgartner (1995) l

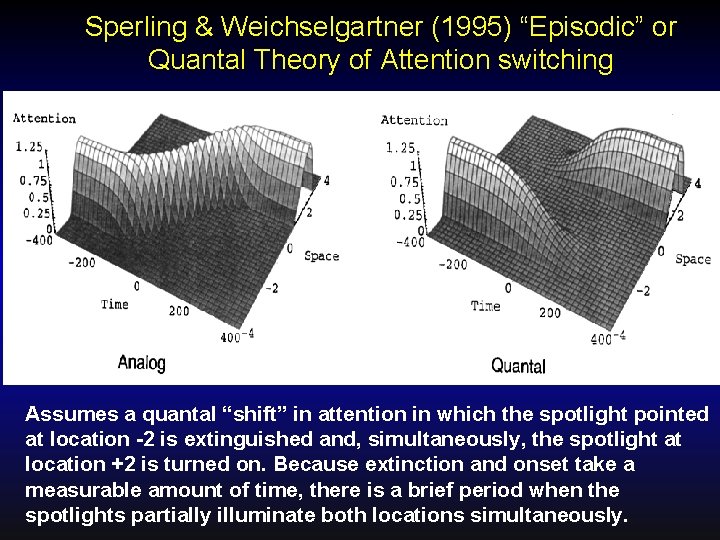

Sperling & Weichselgartner (1995) “Episodic” or Quantal Theory of Attention switching Assumes a quantal “shift” in attention in which the spotlight pointed at location -2 is extinguished and, simultaneously, the spotlight at location +2 is turned on. Because extinction and onset take a measurable amount of time, there is a brief period when the spotlights partially illuminate both locations simultaneously.

This object-based view of attentional selection is at the heart of FINST theory l When we discuss some of the reasons for attention and the mechanisms involved I will propose that there are good reasons on both grounds for supposing that attention attaches itself to objects rather than locations

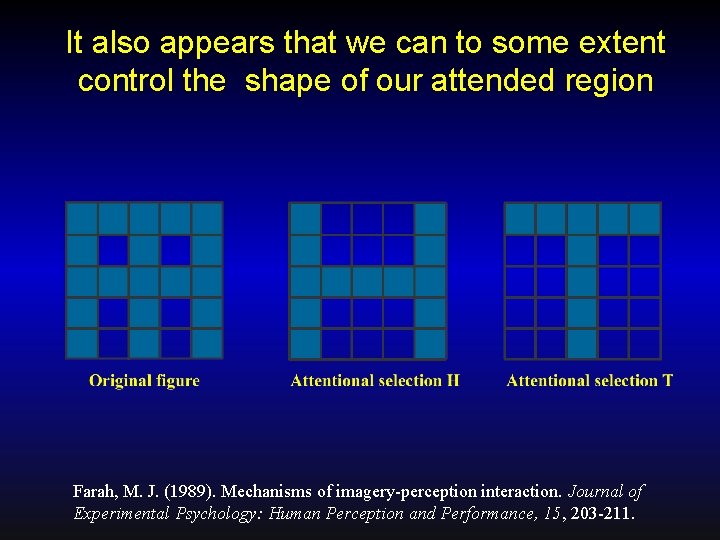

It also appears that we can to some extent control the shape of our attended region Farah, M. J. (1989). Mechanisms of imagery-perception interaction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 15, 203 -211.

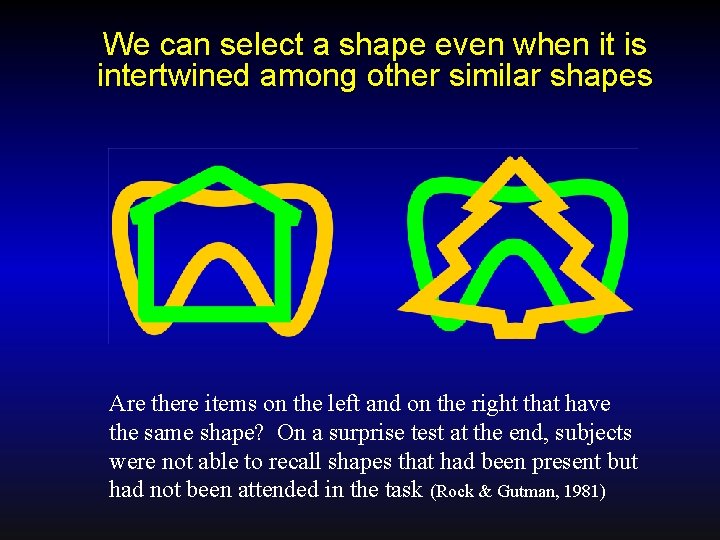

We can select a shape even when it is intertwined among other similar shapes Are there items on the left and on the right that have the same shape? On a surprise test at the end, subjects were not able to recall shapes that had been present but had not been attended in the task (Rock & Gutman, 1981)

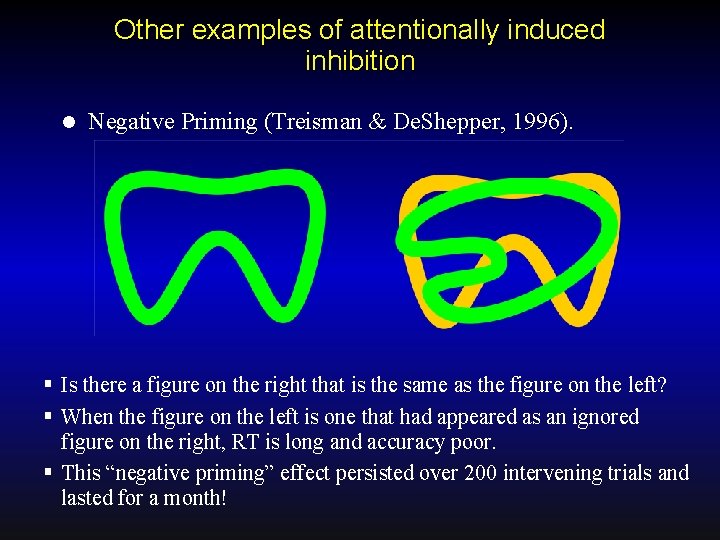

Other examples of attentionally induced inhibition l Negative Priming (Treisman & De. Shepper, 1996). § Is there a figure on the right that is the same as the figure on the left? § When the figure on the left is one that had appeared as an ignored figure on the right, RT is long and accuracy poor. § This “negative priming” effect persisted over 200 intervening trials and lasted for a month!

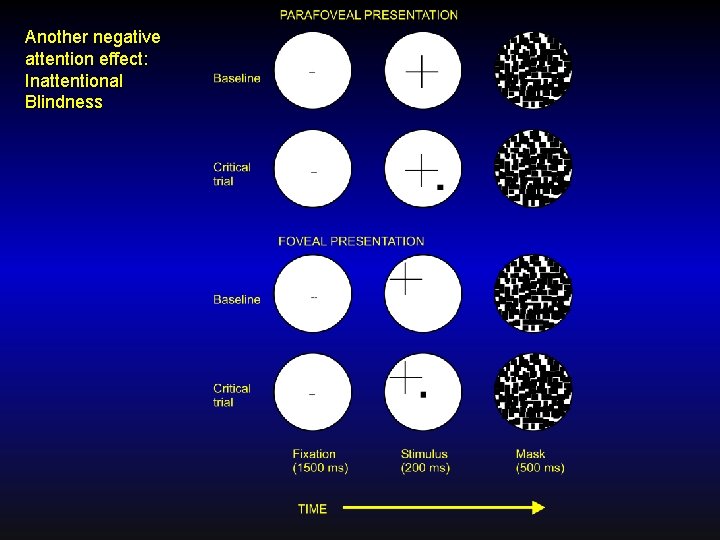

Another negative attention effect: Inattentional Blindness

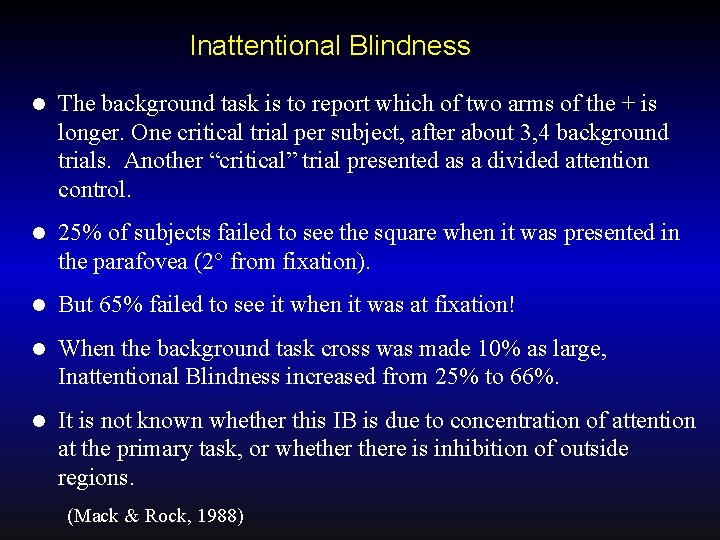

Inattentional Blindness l The background task is to report which of two arms of the + is longer. One critical trial per subject, after about 3, 4 background trials. Another “critical” trial presented as a divided attention control. l 25% of subjects failed to see the square when it was presented in the parafovea (2° from fixation). l But 65% failed to see it when it was at fixation! l When the background task cross was made 10% as large, Inattentional Blindness increased from 25% to 66%. l It is not known whether this IB is due to concentration of attention at the primary task, or whethere is inhibition of outside regions. (Mack & Rock, 1988)

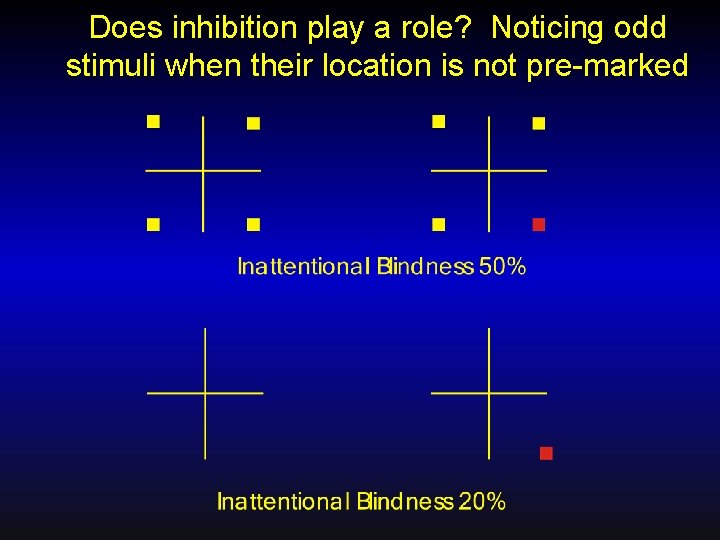

Does inhibition play a role? Noticing odd stimuli when their location is not pre-marked

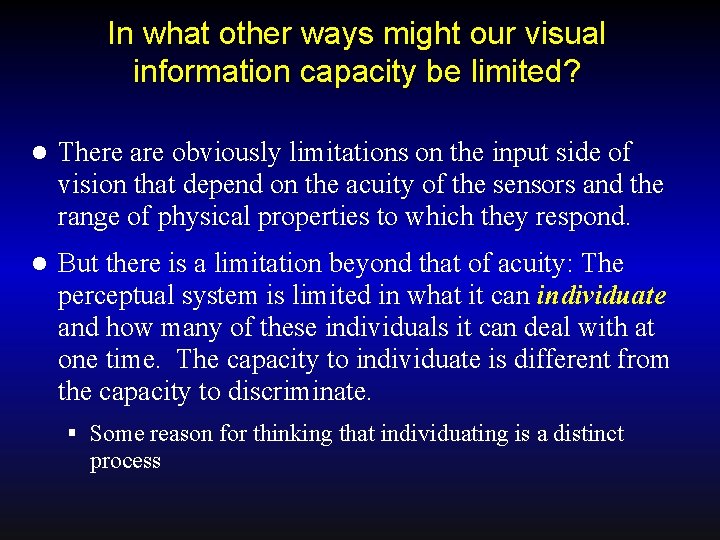

In what other ways might our visual information capacity be limited? l There are obviously limitations on the input side of vision that depend on the acuity of the sensors and the range of physical properties to which they respond. l But there is a limitation beyond that of acuity: The perceptual system is limited in what it can individuate and how many of these individuals it can deal with at one time. The capacity to individuate is different from the capacity to discriminate. § Some reason for thinking that individuating is a distinct process

Exploring the limits of attention and the units over which selection operates It appears that the human information-processing bottleneck cannot be expressed perspicuously in terms of information-theoretic measures, nor can it be specified in physical parameters (e. g. , in terms of locations or spatiotemporal regions), although such measures often do capture important aspects of attention (e. g. , visual attention often moves continuously through space). l But there are other possible ways one might consider expressing the limits of attention. l § Over the past 25 years evidence has been accumulating that the human attention system is, at least in part, tuned to individual objects in the world. This would certainly make sense from an evolutionary perspective. But what does this mean?

Summary of what we have so far l We saw that visual representations must be conceptual for empirical and logical reasons The empirical reasons derive in part from the nature of generalizations and errors of recall § The logical reason is that vision must interact with thoughts and lead to new beliefs and plans of action § We saw that a large part of vision is cognitively impenetrable and encapsulated and that cognition can only be brought to bear prior to or after its automatic operation: As attention or interpretation. l We saw that there are good design reasons for vision to be selective and we considered several bases for selection. But selection is not only for filtering information to a more manageable amount, but it is also required for other reasons. These other reasons make it plausible that selection should operate over objects rather than bits of information in the Shannon sense. l

The increasingly important role played by ‘Objects’ in studies of visual attention l Miller’s ‘Magic Number 7’ has continued to haunt us even beyond studies of short-term memory (STM). l There is a limitation in visual information processing that is beyond the limitation of acuity and of channel capacity: The perceptual system is limited in what it can individuate and how many of these individuals it can deal with at one time. l The capacity to individuate is different from memory capacity and discrimination capacity. § This notion of individuating and of individuals may be related to Miller’s “chunks”, but it has a special role in vision which we will explore in the next lecture § First some reasons why individuating is a distinct process

End of Attention segment Next we will deal with a mechanism that is very closely related to focal attention but yet which (according to some people) is quite different l This mechanism is what enables us to select several objects at once and to keep that selection even of the properties of the object change and the object moves around. It is a sticky pointer or perceptual demonstrative reference l This is about picking out individuals qua individuals l

Segment on Visual Indexing l To be continued later…

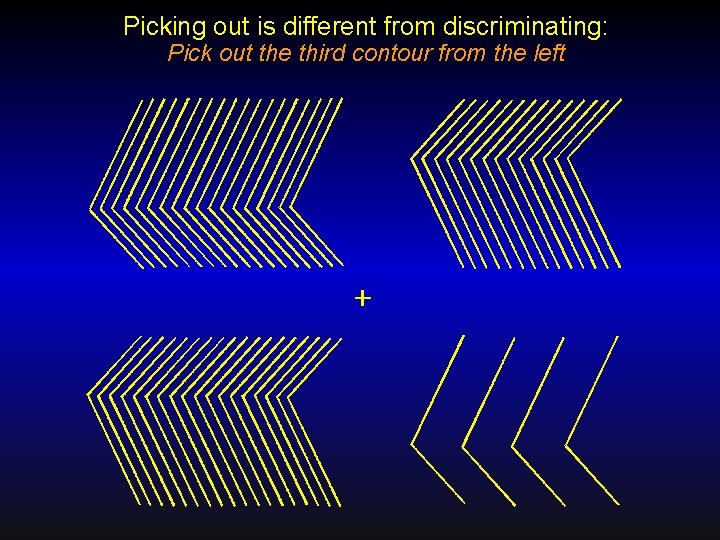

Picking out is different from discriminating: Pick out the third contour from the left

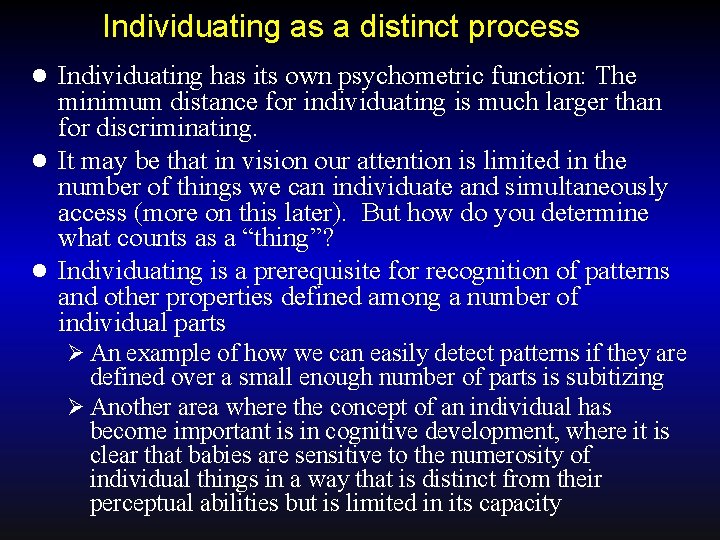

Individuating as a distinct process Individuating has its own psychometric function: The minimum distance for individuating is much larger than for discriminating. l It may be that in vision our attention is limited in the number of things we can individuate and simultaneously access (more on this later). But how do you determine what counts as a “thing”? l Individuating is a prerequisite for recognition of patterns and other properties defined among a number of individual parts l Ø An example of how we can easily detect patterns if they are defined over a small enough number of parts is subitizing Ø Another area where the concept of an individual has become important is in cognitive development, where it is clear that babies are sensitive to the numerosity of individual things in a way that is distinct from their perceptual abilities but is limited in its capacity

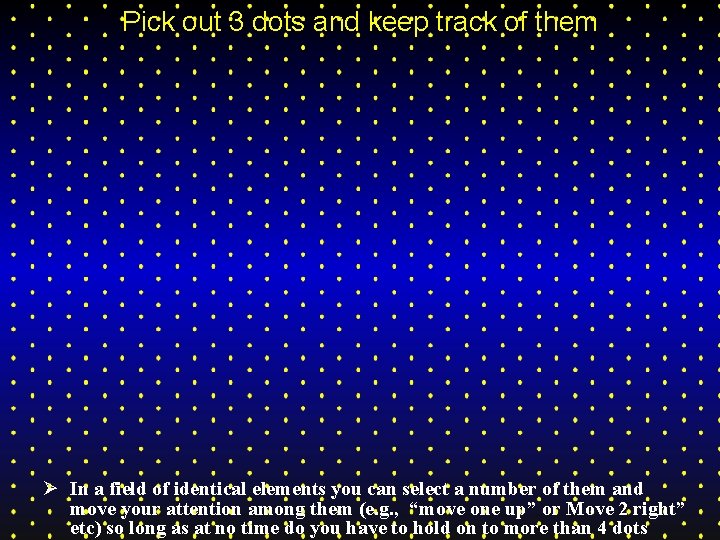

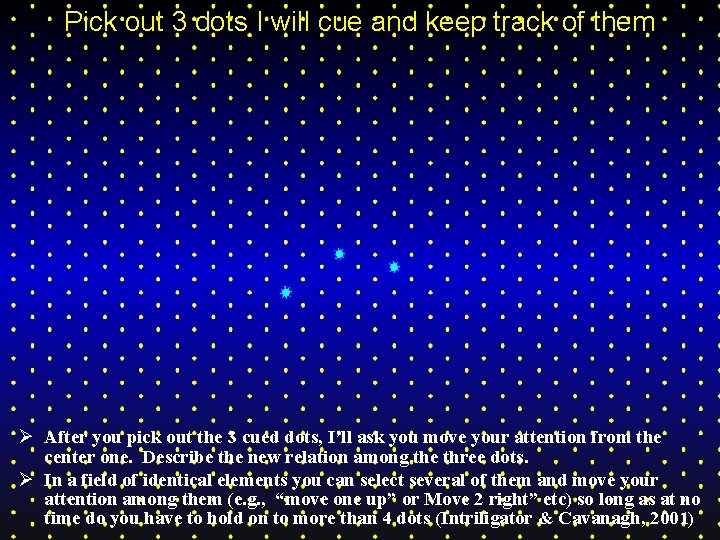

Pick out 3 dots and keep track of them Ø In a field of identical elements you can select a number of them and move your attention among them (e. g. , “move one up” or Move 2 right” etc) so long as at no time do you have to hold on to more than 4 dots

Pick out 3 dots I will cue and keep track of them Ø After you pick out the 3 cued dots, I’ll ask you move your attention from the center one. Describe the new relation among the three dots. Ø In a field of identical elements you can select several of them and move your attention among them (e. g. , “move one up” or Move 2 right” etc) so long as at no time do you have to hold on to more than 4 dots (Intriligator & Cavanagh, 2001)

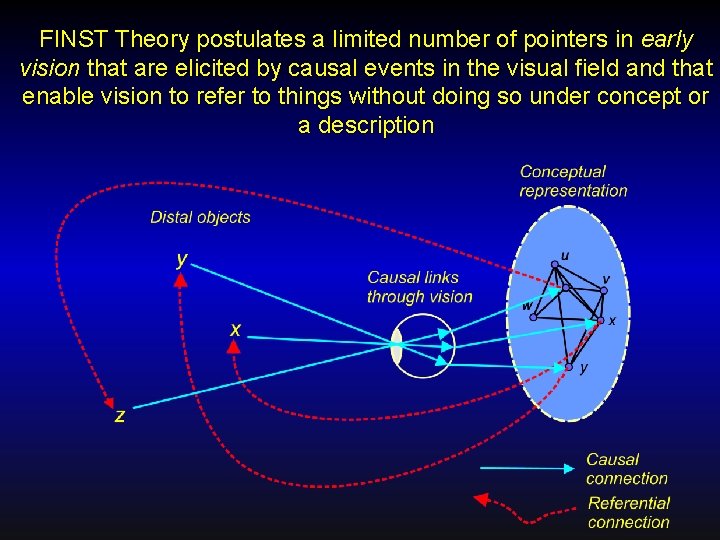

Visual Indexes (aka FINSTs) The hypothesis is that in vision there is a limit to how many objects (individuals) can be selected and bound to the arguments of cognitive functions at one time. l There is evidence that we can hold on to 4 objects in visual short term memory (Luck & Vogel, 1997). l There is evidence that Objects (i. e. , individual things) may be the basic units of visual attention l FINST Theory claims that there is a mechanism for picking out and referring to (pointing to) primitive visual elements (which are generally referred to as Objects) l

The requirements for picking out individual things and keeping track of them reminded me of an early comic book character called “Plastic Man”

Imagine being able to place several of your fingers on things in the world without being able to detect their properties in this way, but being able to refer to those things so you could move your gaze or attention to them. If you could you would possess FINgers of INSTantiation = FINSTs!

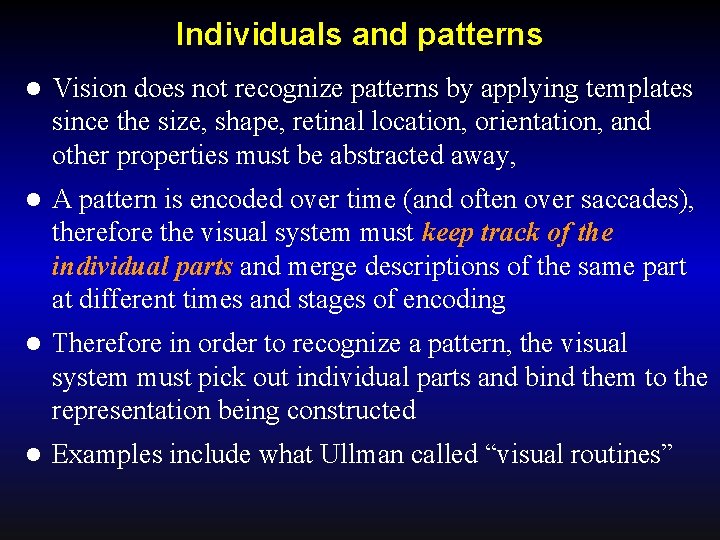

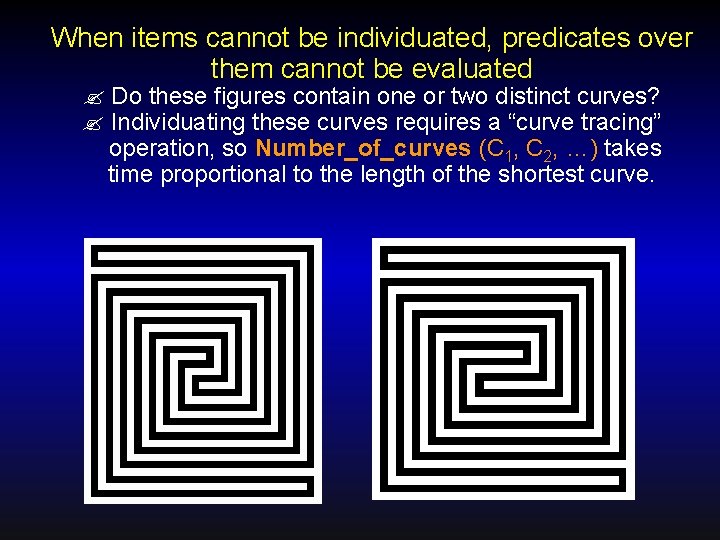

Individuals and patterns l Vision does not recognize patterns by applying templates since the size, shape, retinal location, orientation, and other properties must be abstracted away, l A pattern is encoded over time (and often over saccades), therefore the visual system must keep track of the individual parts and merge descriptions of the same part at different times and stages of encoding l Therefore in order to recognize a pattern, the visual system must pick out individual parts and bind them to the representation being constructed l Examples include what Ullman called “visual routines”

Are there collinear items (n>3)?

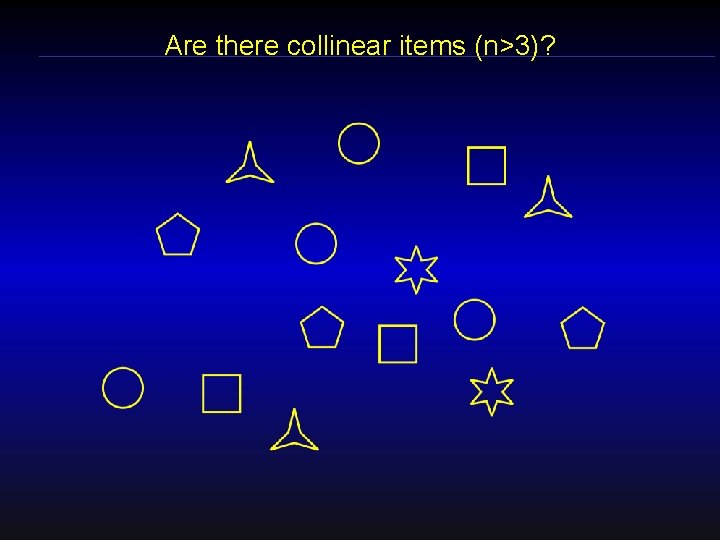

Several objects must be picked out at once in making relational judgments l The same is true for other relational judgments like inside or on-the-samecontour… etc. We must pick out the relevant individual objects first. Respond: Inside-same contour? On-same contour?

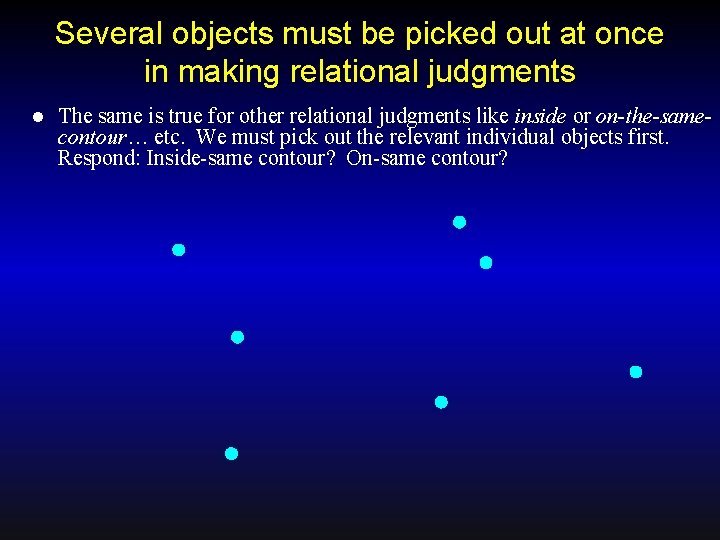

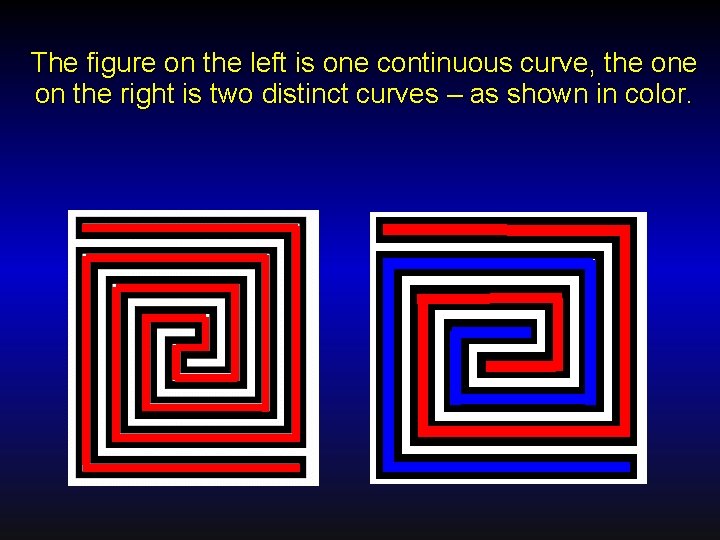

When items cannot be individuated, predicates over them cannot be evaluated Do these figures contain one or two distinct curves? Individuating these curves requires a “curve tracing” operation, so Number_of_curves (C 1, C 2, …) takes time proportional to the length of the shortest curve.

The figure on the left is one continuous curve, the on the right is two distinct curves – as shown in color.

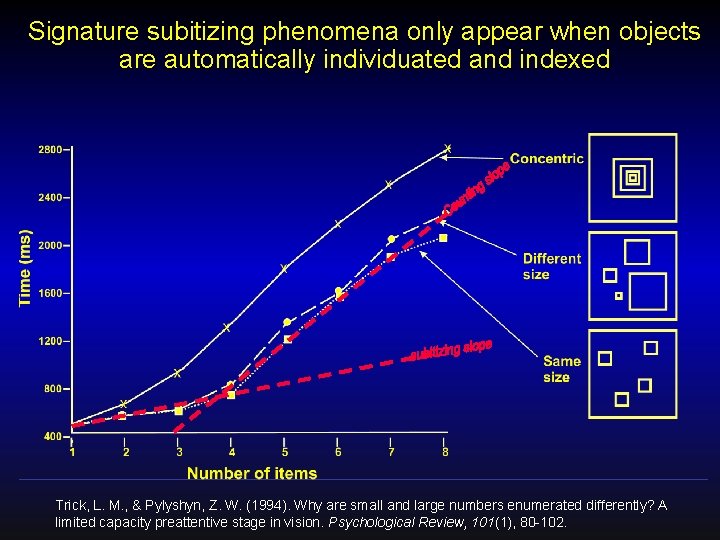

Signature subitizing phenomena only appear when objects are automatically individuated and indexed Trick, L. M. , & Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1994). Why are small and large numbers enumerated differently? A limited capacity preattentive stage in vision. Psychological Review, 101(1), 80 -102.

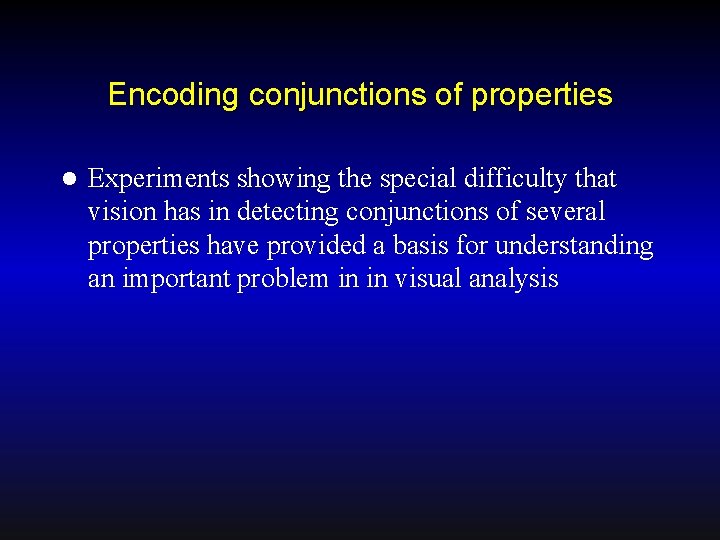

Encoding conjunctions of properties l Experiments showing the special difficulty that vision has in detecting conjunctions of several properties have provided a basis for understanding an important problem in in visual analysis

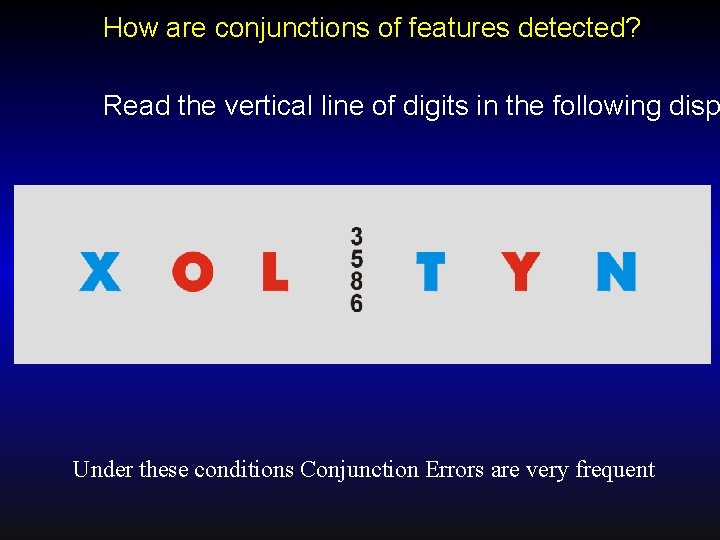

How are conjunctions of features detected? Read the vertical line of digits in the following disp Under these conditions Conjunction Errors are very frequent

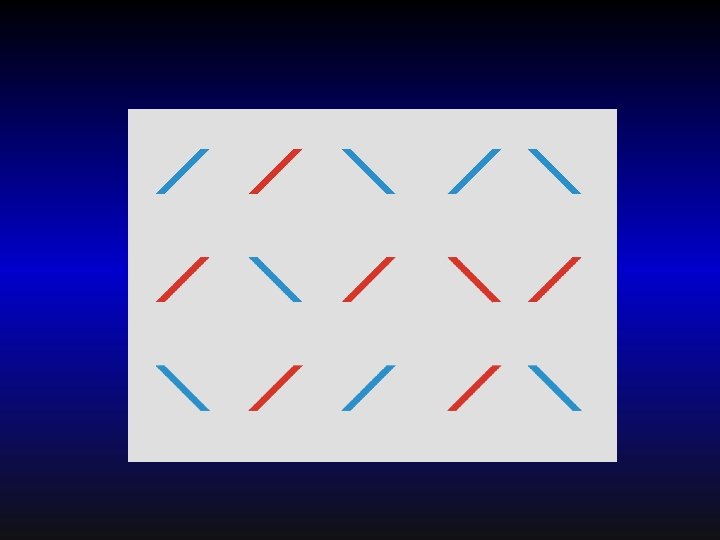

Rapid visual search (Treisman) Find the following simple figure in the next slide:

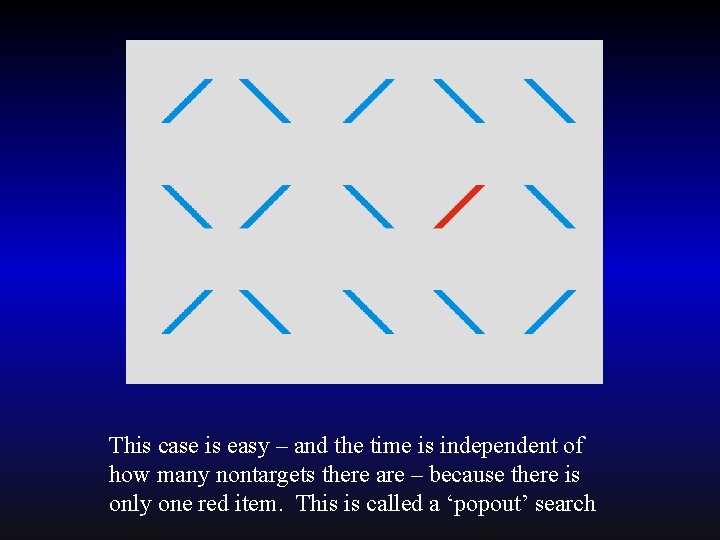

This case is easy – and the time is independent of how many nontargets there are – because there is only one red item. This is called a ‘popout’ search

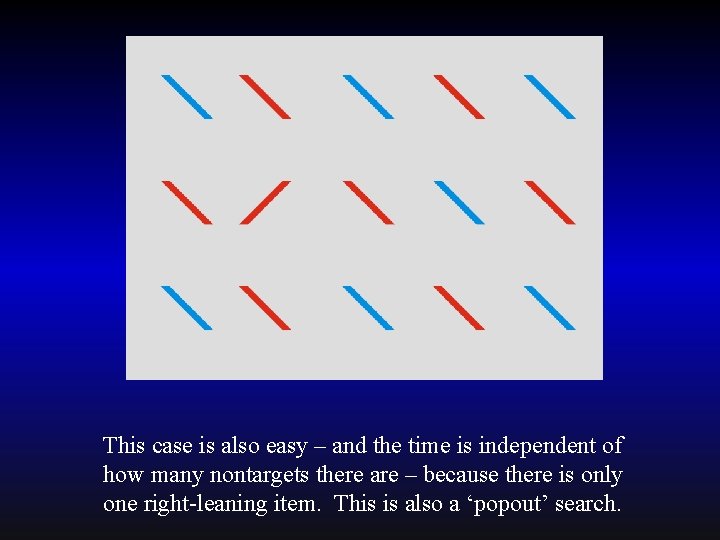

This case is also easy – and the time is independent of how many nontargets there are – because there is only one right-leaning item. This is also a ‘popout’ search.

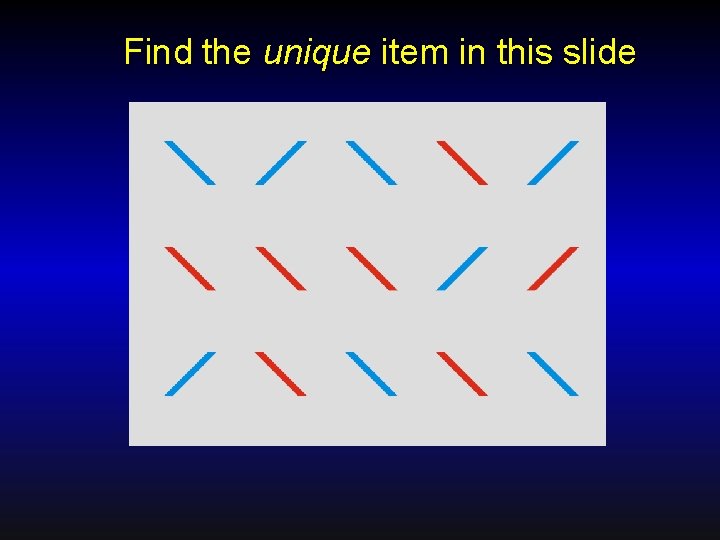

Rapid visual search (conjunction) Find the following simple figure in the next slide:

Find the unique item in this slide

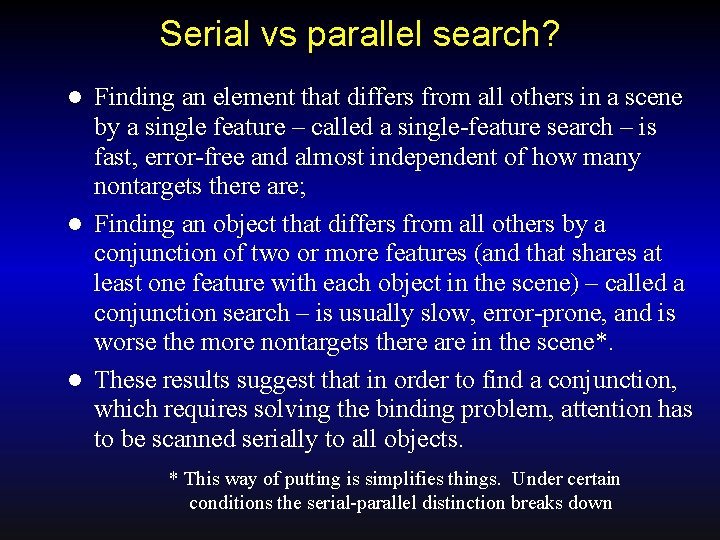

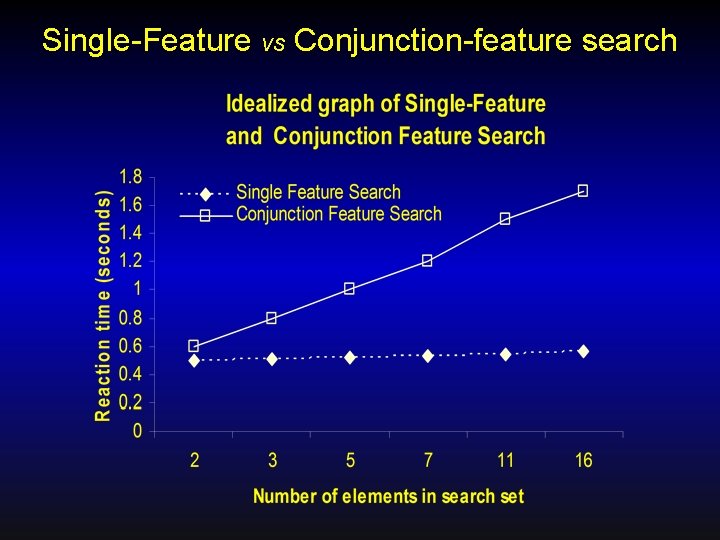

Serial vs parallel search? Finding an element that differs from all others in a scene by a single feature – called a single-feature search – is fast, error-free and almost independent of how many nontargets there are; l Finding an object that differs from all others by a conjunction of two or more features (and that shares at least one feature with each object in the scene) – called a conjunction search – is usually slow, error-prone, and is worse the more nontargets there are in the scene*. l These results suggest that in order to find a conjunction, which requires solving the binding problem, attention has to be scanned serially to all objects. l * This way of putting is simplifies things. Under certain conditions the serial-parallel distinction breaks down

Single-Feature vs Conjunction-feature search

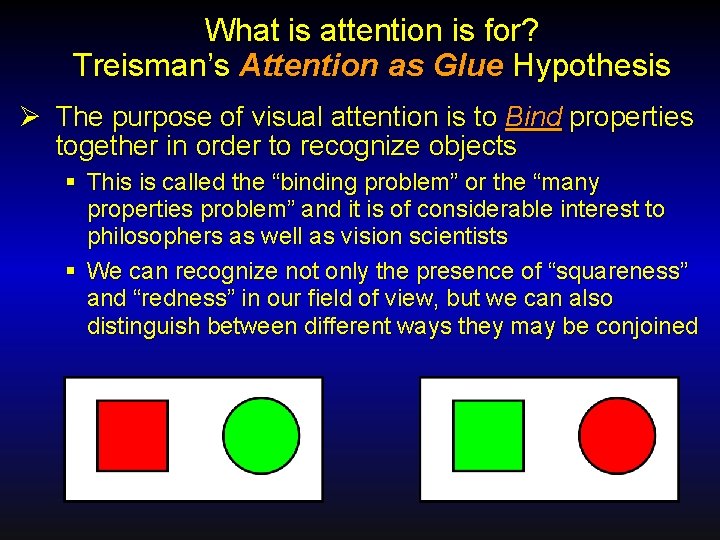

What is attention is for? Treisman’s Attention as Glue Hypothesis Ø The purpose of visual attention is to Bind properties together in order to recognize objects § This is called the “binding problem” or the “many properties problem” and it is of considerable interest to philosophers as well as vision scientists § We can recognize not only the presence of “squareness” and “redness” in our field of view, but we can also distinguish between different ways they may be conjoined

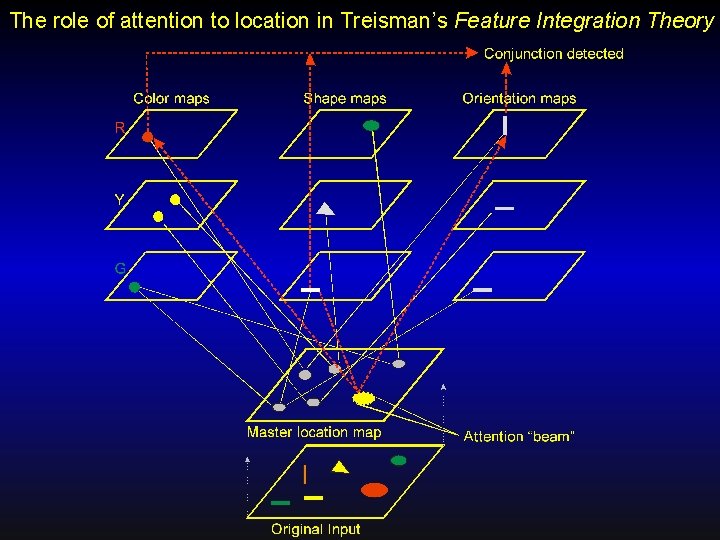

The role of attention to location in Treisman’s Feature Integration Theory

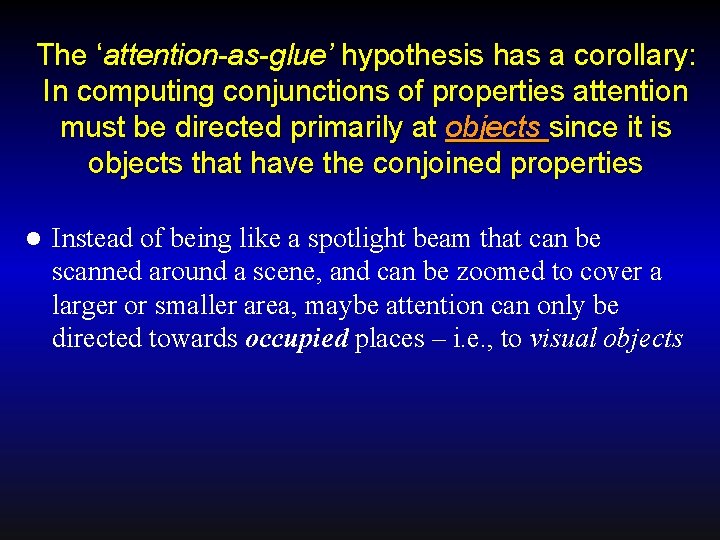

The ‘attention-as-glue’ hypothesis has a corollary: In computing conjunctions of properties attention must be directed primarily at objects since it is objects that have the conjoined properties l Instead of being like a spotlight beam that can be scanned around a scene, and can be zoomed to cover a larger or smaller area, maybe attention can only be directed towards occupied places – i. e. , to visual objects

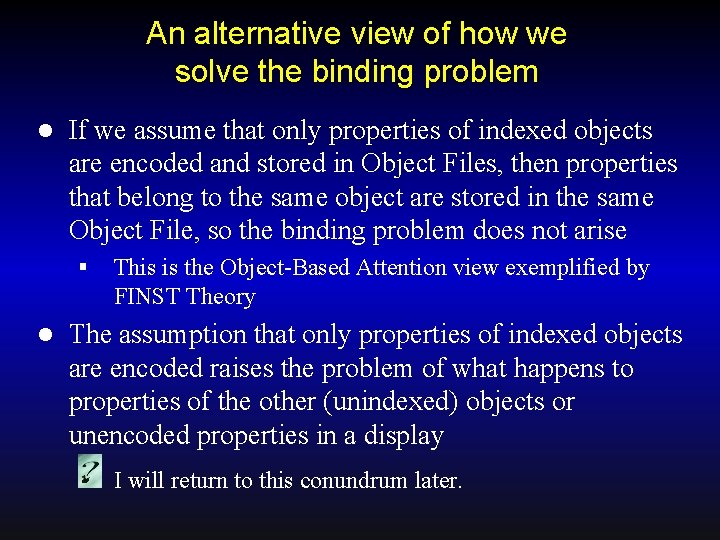

An alternative view of how we solve the binding problem l If we assume that only properties of indexed objects are encoded and stored in Object Files, then properties that belong to the same object are stored in the same Object File, so the binding problem does not arise § l This is the Object-Based Attention view exemplified by FINST Theory The assumption that only properties of indexed objects are encoded raises the problem of what happens to properties of the other (unindexed) objects or unencoded properties in a display I will return to this conundrum later.

FINST Theory postulates a limited number of pointers in early vision that are elicited by causal events in the visual field and that enable vision to refer to things without doing so under concept or a description

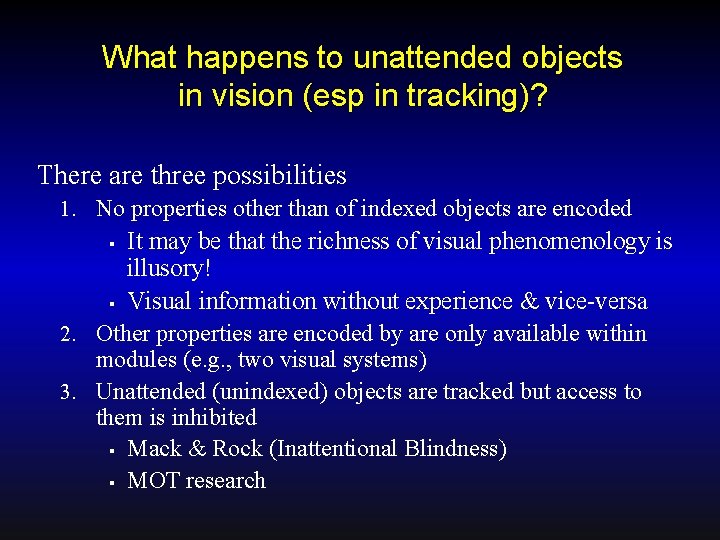

What happens to unattended objects in vision (esp in tracking)? There are three possibilities 1. No properties other than of indexed objects are encoded It may be that the richness of visual phenomenology is illusory! § Visual information without experience & vice-versa 2. Other properties are encoded by are only available within modules (e. g. , two visual systems) 3. Unattended (unindexed) objects are tracked but access to them is inhibited § Mack & Rock (Inattentional Blindness) § MOT research §

Evidence for attentional selection based on Objects l l l Single Object Advantage: pairs of judgments are faster when both apply to the same perceived object Entire objects acquire enhanced sensitivity from focal attention to a part of the object Single-Object advantage occurs even with generalized “objects” defined in feature space Simultanagnosia and hemispatial neglect show object-based effect Attention moves with Moving Objects Ø IOR Ø Object Files Ø MOT

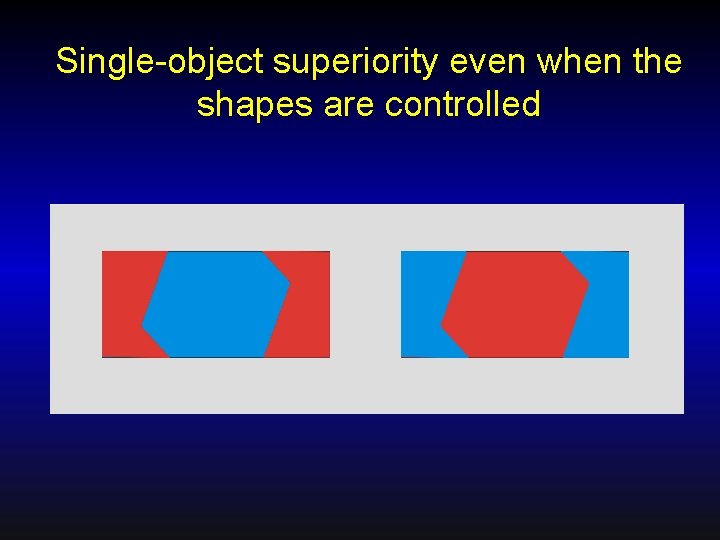

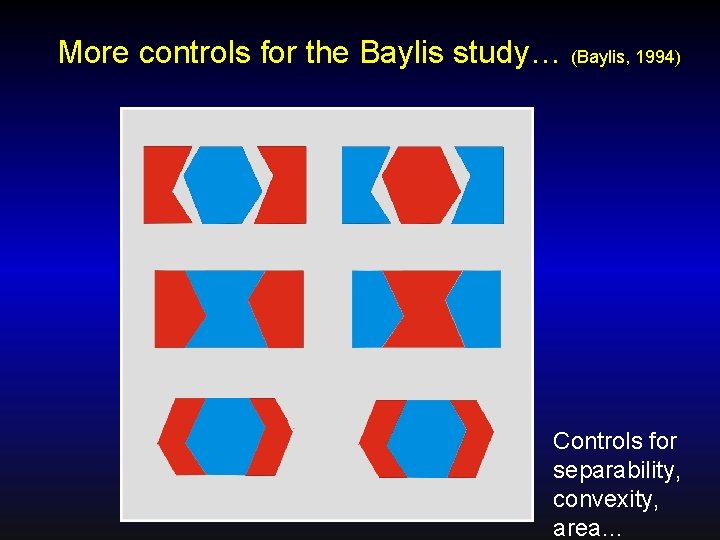

Single-object superiority even when the shapes are controlled

More controls for the Baylis study… (Baylis, 1994) Controls for separability, convexity, area…

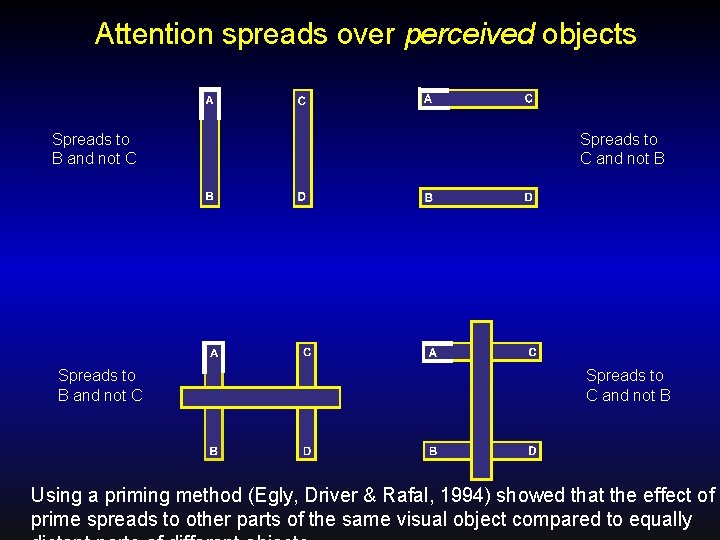

Attention spreads over perceived objects Spreads to B and not C Spreads to C and not B Using a priming method (Egly, Driver & Rafal, 1994) showed that the effect of a prime spreads to other parts of the same visual object compared to equally

Objecthood endures over time l Several studies have shown that what counts as an object (as the same object) endures over time and over changes in location; Ø Certain forms of disappearances in time and changes in location preserve objecthood. l This gives what we have been calling a “visual object” a real physical-object character and partly justifies our calling it an “object”.

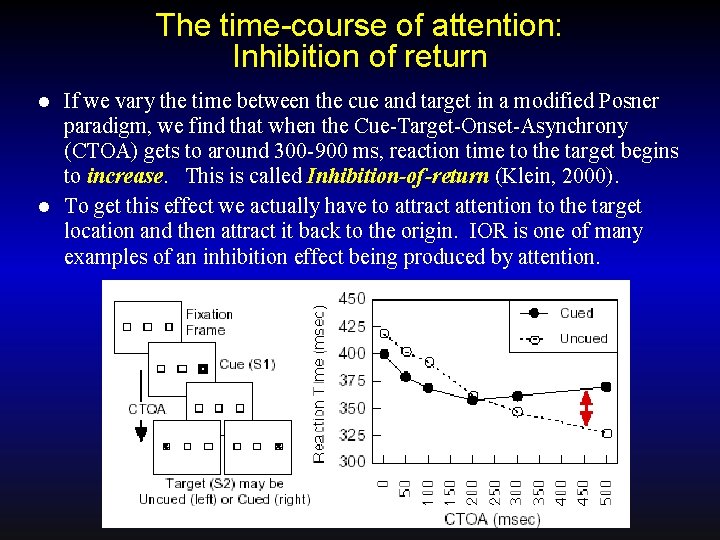

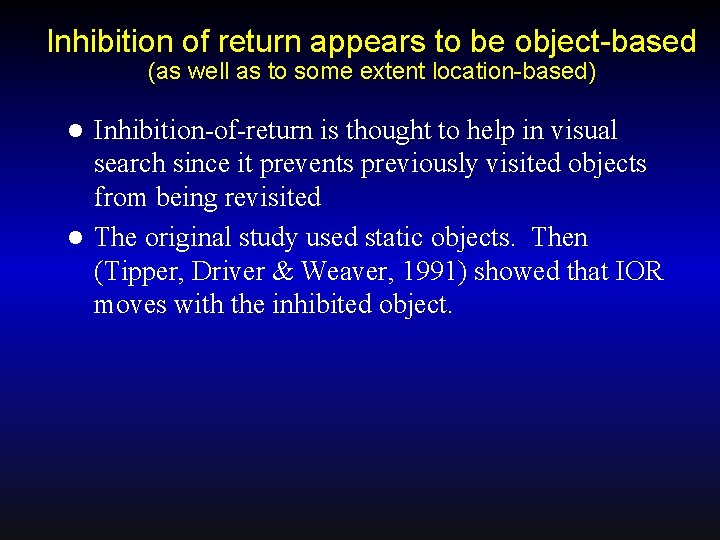

The time-course of attention: Inhibition of return If we vary the time between the cue and target in a modified Posner paradigm, we find that when the Cue-Target-Onset-Asynchrony (CTOA) gets to around 300 -900 ms, reaction time to the target begins to increase. This is called Inhibition-of-return (Klein, 2000). l To get this effect we actually have to attract attention to the target location and then attract it back to the origin. IOR is one of many examples of an inhibition effect being produced by attention. l

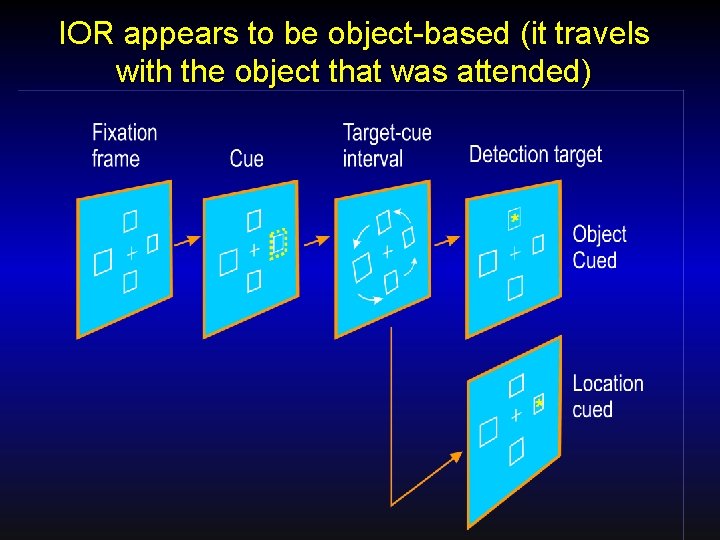

Inhibition of return appears to be object-based (as well as to some extent location-based) Inhibition-of-return is thought to help in visual search since it prevents previously visited objects from being revisited l The original study used static objects. Then (Tipper, Driver & Weaver, 1991) showed that IOR moves with the inhibited object. l

IOR appears to be object-based (it travels with the object that was attended)

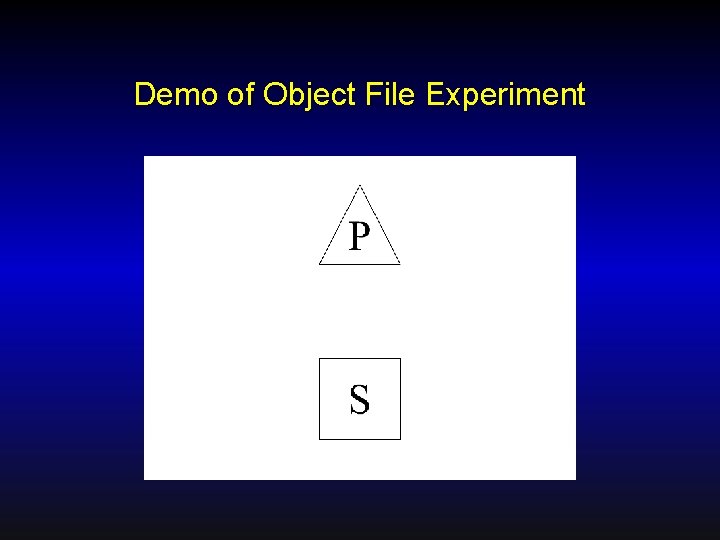

Demo of Object File Experiment

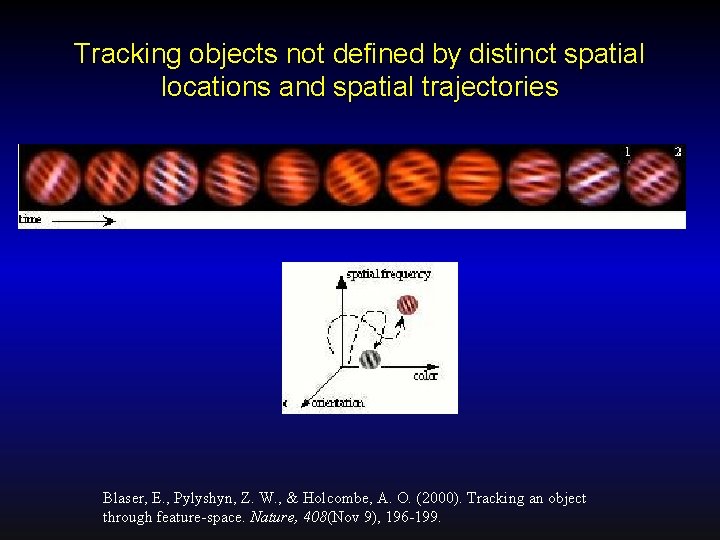

Tracking objects not defined by distinct spatial locations and spatial trajectories Blaser, E. , Pylyshyn, Z. W. , & Holcombe, A. O. (2000). Tracking an object through feature-space. Nature, 408(Nov 9), 196 -199.

There is also evidence from neuropsychology that is consistent with the object-based view Neglect l Balint and simultanagnosic patients l

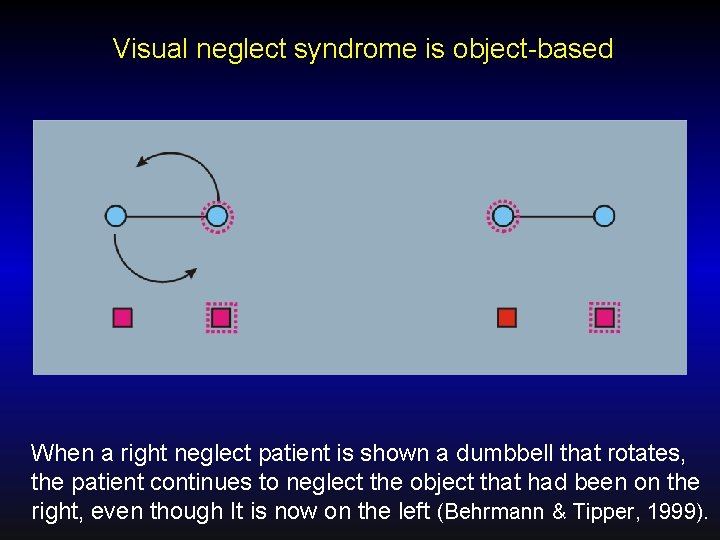

Visual neglect syndrome is object-based When a right neglect patient is shown a dumbbell that rotates, the patient continues to neglect the object that had been on the right, even though It is now on the left (Behrmann & Tipper, 1999).

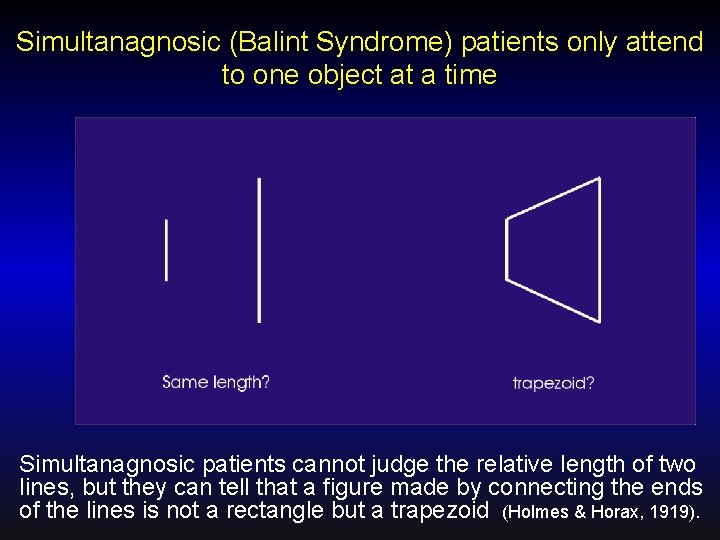

Simultanagnosic (Balint Syndrome) patients only attend to one object at a time Simultanagnosic patients cannot judge the relative length of two lines, but they can tell that a figure made by connecting the ends of the lines is not a rectangle but a trapezoid (Holmes & Horax, 1919).

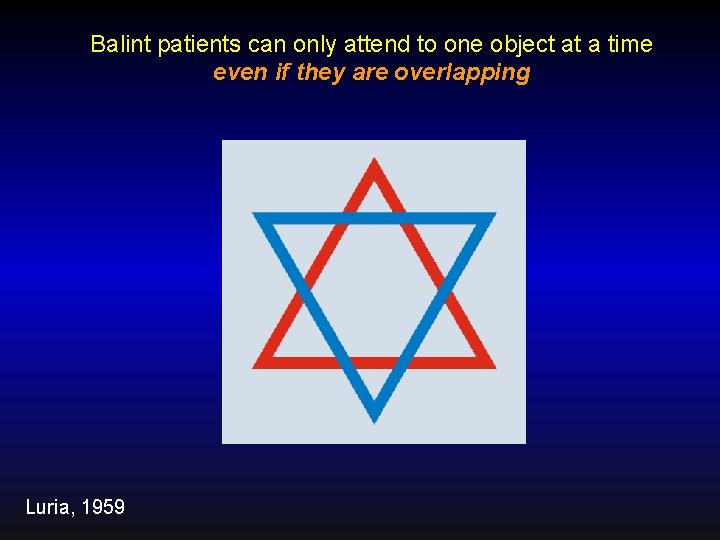

Balint patients can only attend to one object at a time even if they are overlapping Luria, 1959

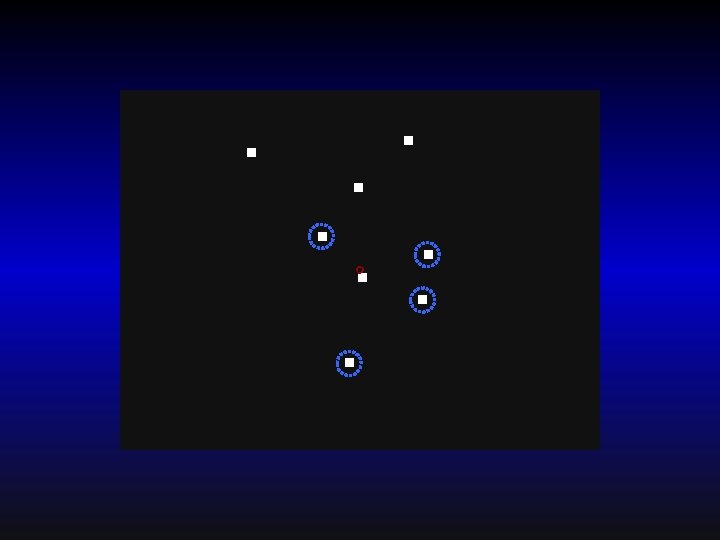

Multiple Object Tracking l One of the clearest cases illustrating object-based attention is Multiple Object Tracking l Keeping track of individual objects in a scene requires a mechanism for individuating, selecting, accessing and tracking the identity of individuals over time § These are the functions we have proposed are carried out by the mechanism of visual indexes (FINSTs) § We have been using a variety of methods for studying visual indexing, including subitizing, subset selection for search, and Multiple Object Tracking (MOT).

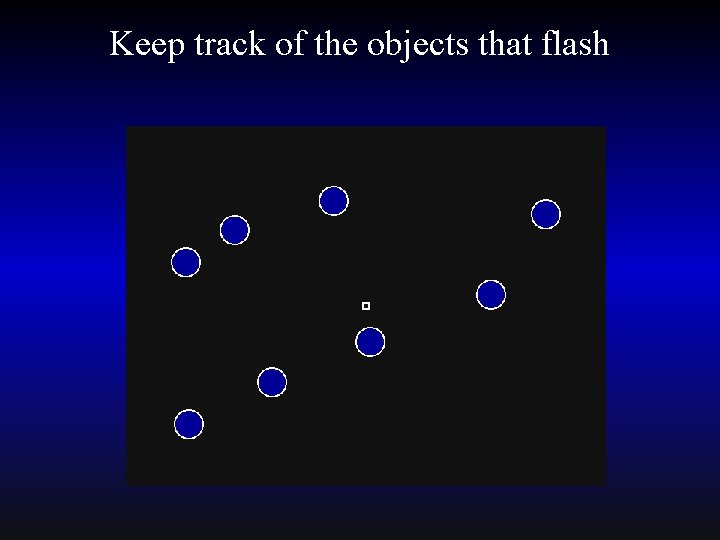

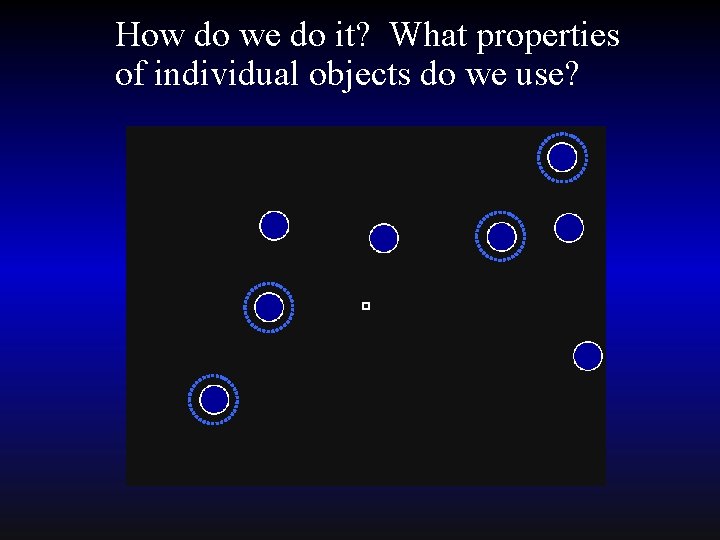

Multiple Object Tracking l In a typical experiment, 8 simple identical objects are presented on a screen and 4 of them are briefly distinguished in some visual manner – usually by flashing them on and off. l After these 4 “targets” have been briefly identified, all objects resume their identical appearance and move randomly. The subjects’ task is to keep track of which ones had earlier been designated as targets. l After a period of 5 -10 seconds the motion stops and subjects must indicate, using a mouse, which objects were the targets. l People are very good at this task (80%-98% correct). The question is: How do they do it?

Keep track of the objects that flash

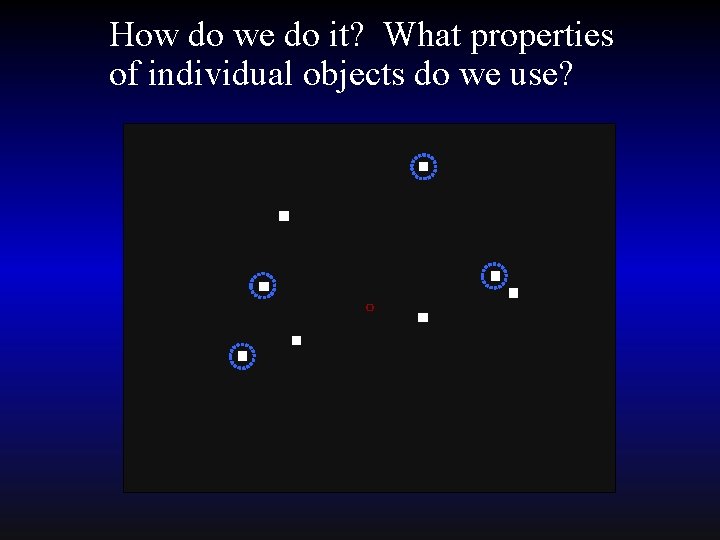

How do we do it? What properties of individual objects do we use?

Keep track of the objects that flash

How do we do it? What properties of individual objects do we use?

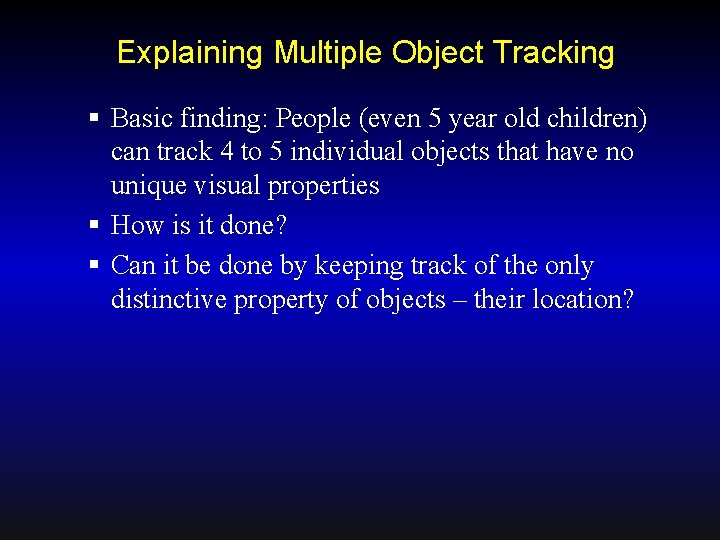

Explaining Multiple Object Tracking § Basic finding: People (even 5 year old children) can track 4 to 5 individual objects that have no unique visual properties § How is it done? § Can it be done by keeping track of the only distinctive property of objects – their location?

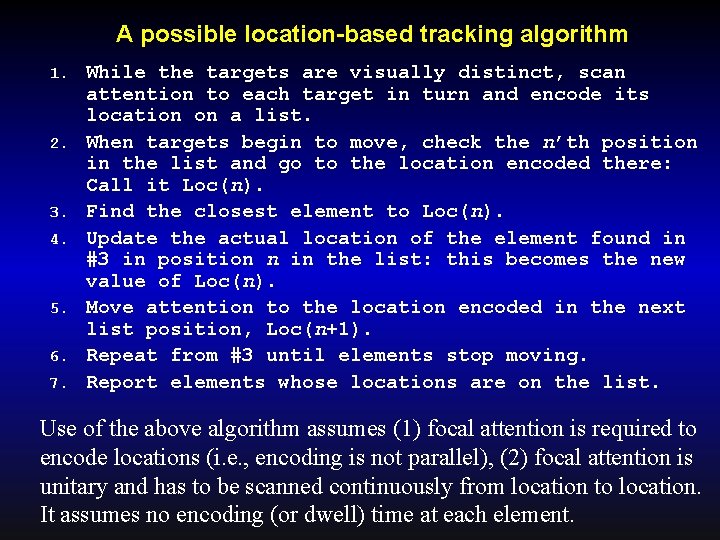

A possible location-based tracking algorithm 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. While the targets are visually distinct, scan attention to each target in turn and encode its location on a list. When targets begin to move, check the n’th position in the list and go to the location encoded there: Call it Loc(n). Find the closest element to Loc(n). Update the actual location of the element found in #3 in position n in the list: this becomes the new value of Loc(n). Move attention to the location encoded in the next list position, Loc(n+1). Repeat from #3 until elements stop moving. Report elements whose locations are on the list. Use of the above algorithm assumes (1) focal attention is required to encode locations (i. e. , encoding is not parallel), (2) focal attention is unitary and has to be scanned continuously from location to location. It assumes no encoding (or dwell) time at each element.

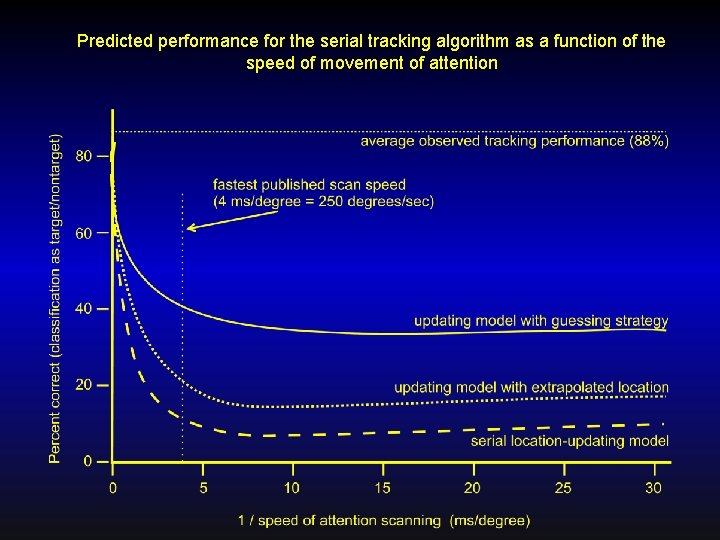

Predicted performance for the serial tracking algorithm as a function of the speed of movement of attention

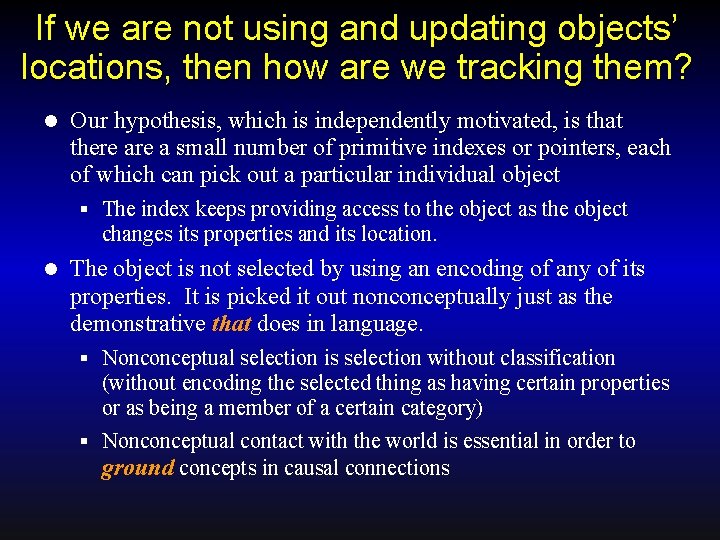

If we are not using and updating objects’ locations, then how are we tracking them? l Our hypothesis, which is independently motivated, is that there a small number of primitive indexes or pointers, each of which can pick out a particular individual object § The index keeps providing access to the object as the object changes its properties and its location. l The object is not selected by using an encoding of any of its properties. It is picked it out nonconceptually just as the demonstrative that does in language. § Nonconceptual selection is selection without classification (without encoding the selected thing as having certain properties or as being a member of a certain category) § Nonconceptual contact with the world is essential in order to ground concepts in causal connections

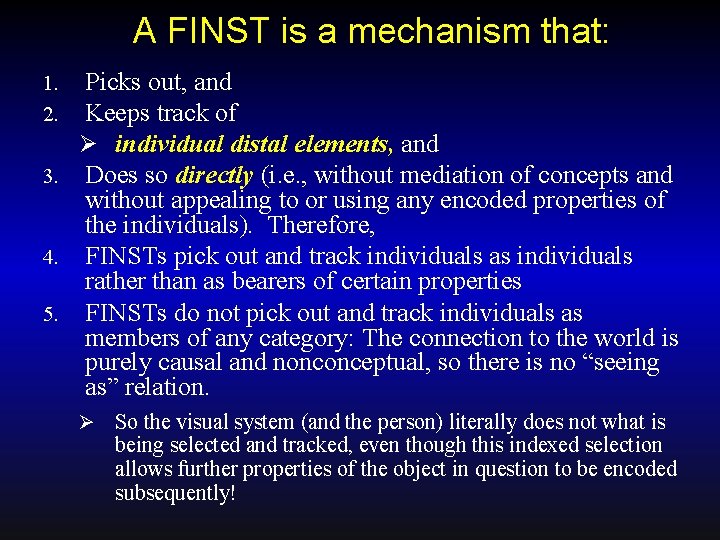

A FINST is a mechanism that: Picks out, and Keeps track of Ø individual distal elements, and 3. Does so directly (i. e. , without mediation of concepts and without appealing to or using any encoded properties of the individuals). Therefore, 4. FINSTs pick out and track individuals as individuals rather than as bearers of certain properties 5. FINSTs do not pick out and track individuals as members of any category: The connection to the world is purely causal and nonconceptual, so there is no “seeing as” relation. 1. 2. Ø So the visual system (and the person) literally does not what is being selected and tracked, even though this indexed selection allows further properties of the object in question to be encoded subsequently!

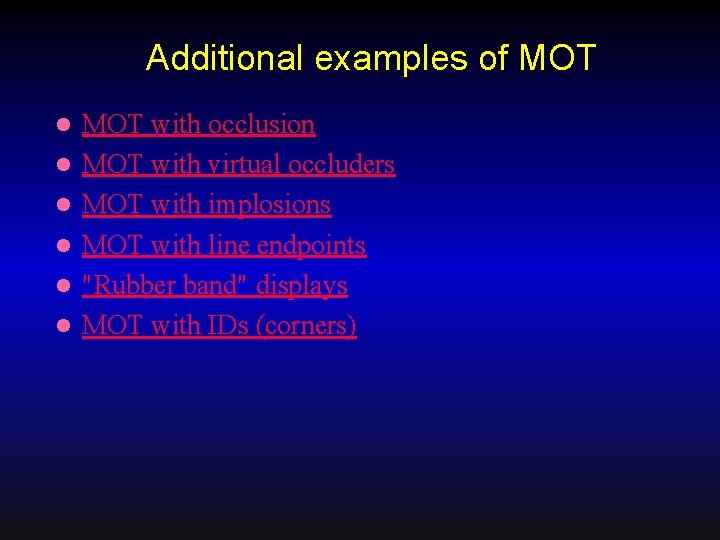

Additional examples of MOT l l l MOT with occlusion MOT with virtual occluders MOT with implosions MOT with line endpoints "Rubber band" displays MOT with IDs (corners)

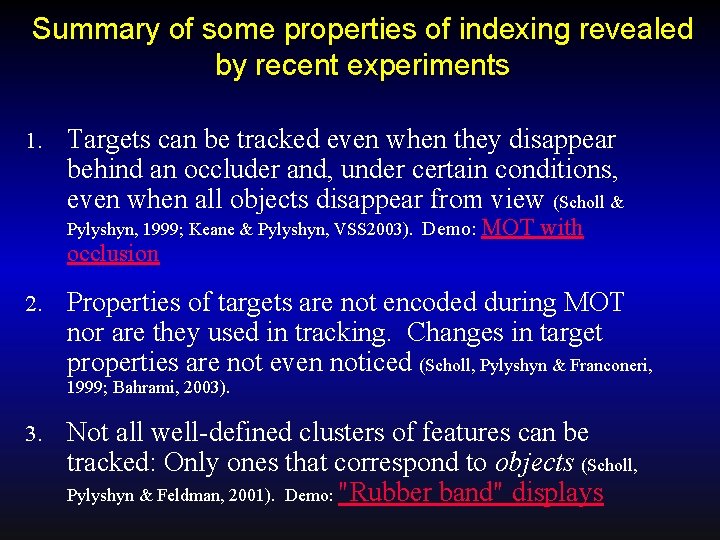

Summary of some properties of indexing revealed by recent experiments 1. Targets can be tracked even when they disappear behind an occluder and, under certain conditions, even when all objects disappear from view (Scholl & Pylyshyn, 1999; Keane & Pylyshyn, VSS 2003). Demo: MOT occlusion 2. with Properties of targets are not encoded during MOT nor are they used in tracking. Changes in target properties are not even noticed (Scholl, Pylyshyn & Franconeri, 1999; Bahrami, 2003). 3. Not all well-defined clusters of features can be tracked: Only ones that correspond to objects (Scholl, Pylyshyn & Feldman, 2001). Demo: "Rubber band" displays

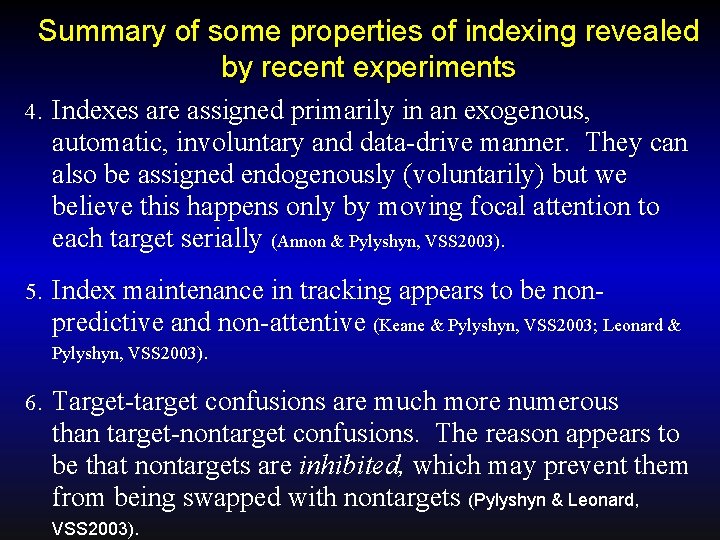

Summary of some properties of indexing revealed by recent experiments 4. Indexes are assigned primarily in an exogenous, automatic, involuntary and data-drive manner. They can also be assigned endogenously (voluntarily) but we believe this happens only by moving focal attention to each target serially (Annon & Pylyshyn, VSS 2003). 5. Index maintenance in tracking appears to be nonpredictive and non-attentive (Keane & Pylyshyn, VSS 2003; Leonard & Pylyshyn, VSS 2003). 6. Target-target confusions are much more numerous than target-nontarget confusions. The reason appears to be that nontargets are inhibited, which may prevent them from being swapped with nontargets (Pylyshyn & Leonard, VSS 2003).

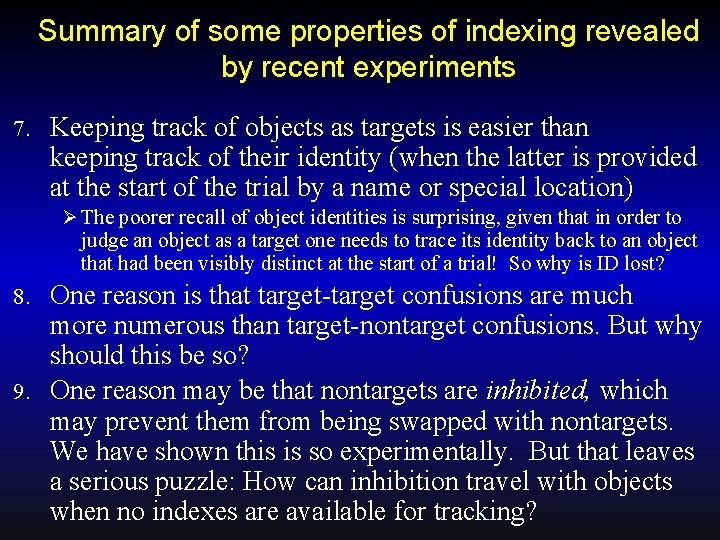

Summary of some properties of indexing revealed by recent experiments 7. Keeping track of objects as targets is easier than keeping track of their identity (when the latter is provided at the start of the trial by a name or special location) Ø The poorer recall of object identities is surprising, given that in order to judge an object as a target one needs to trace its identity back to an object that had been visibly distinct at the start of a trial! So why is ID lost? One reason is that target-target confusions are much more numerous than target-nontarget confusions. But why should this be so? 9. One reason may be that nontargets are inhibited, which may prevent them from being swapped with nontargets. We have shown this is so experimentally. But that leaves a serious puzzle: How can inhibition travel with objects when no indexes are available for tracking? 8.

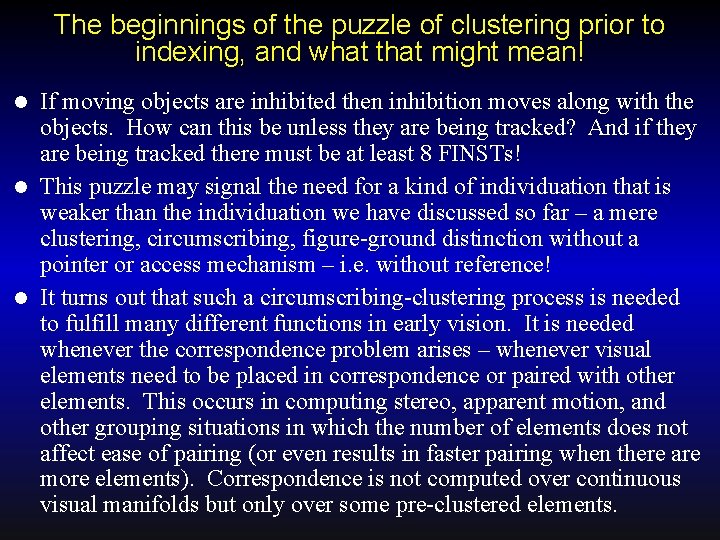

The beginnings of the puzzle of clustering prior to indexing, and what that might mean! If moving objects are inhibited then inhibition moves along with the objects. How can this be unless they are being tracked? And if they are being tracked there must be at least 8 FINSTs! l This puzzle may signal the need for a kind of individuation that is weaker than the individuation we have discussed so far – a mere clustering, circumscribing, figure-ground distinction without a pointer or access mechanism – i. e. without reference! l It turns out that such a circumscribing-clustering process is needed to fulfill many different functions in early vision. It is needed whenever the correspondence problem arises – whenever visual elements need to be placed in correspondence or paired with other elements. This occurs in computing stereo, apparent motion, and other grouping situations in which the number of elements does not affect ease of pairing (or even results in faster pairing when there are more elements). Correspondence is not computed over continuous visual manifolds but only over some pre-clustered elements. l

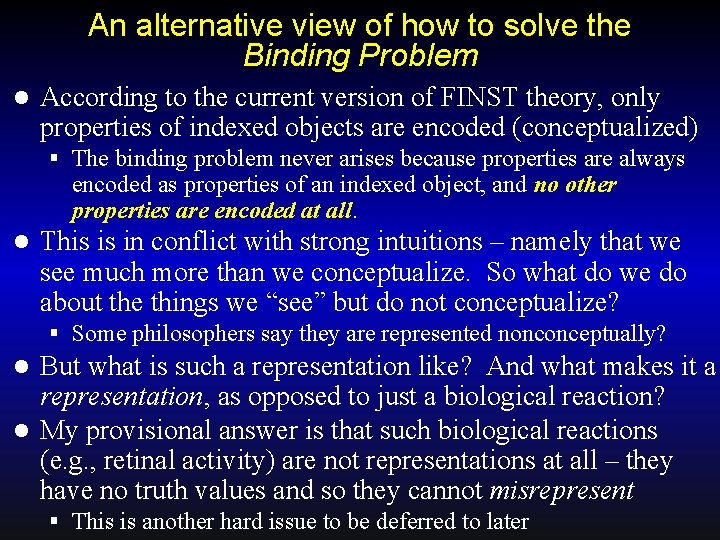

An alternative view of how to solve the Binding Problem l According to the current version of FINST theory, only properties of indexed objects are encoded (conceptualized) § The binding problem never arises because properties are always encoded as properties of an indexed object, and no other properties are encoded at all. l This is in conflict with strong intuitions – namely that we see much more than we conceptualize. So what do we do about the things we “see” but do not conceptualize? § Some philosophers say they are represented nonconceptually? But what is such a representation like? And what makes it a representation, as opposed to just a biological reaction? l My provisional answer is that such biological reactions (e. g. , retinal activity) are not representations at all – they have no truth values and so they cannot misrepresent l § This is another hard issue to be deferred to later

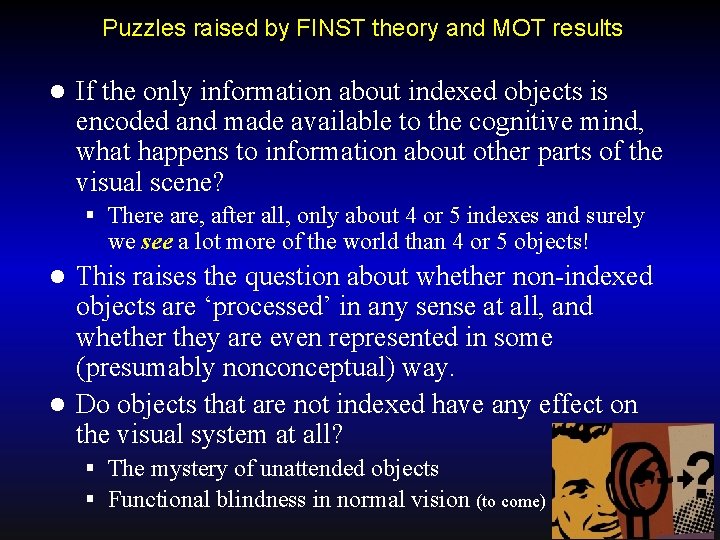

Puzzles raised by FINST theory and MOT results l If the only information about indexed objects is encoded and made available to the cognitive mind, what happens to information about other parts of the visual scene? § There are, after all, only about 4 or 5 indexes and surely we see a lot more of the world than 4 or 5 objects! This raises the question about whether non-indexed objects are ‘processed’ in any sense at all, and whether they are even represented in some (presumably nonconceptual) way. l Do objects that are not indexed have any effect on the visual system at all? l § The mystery of unattended objects § Functional blindness in normal vision (to come)

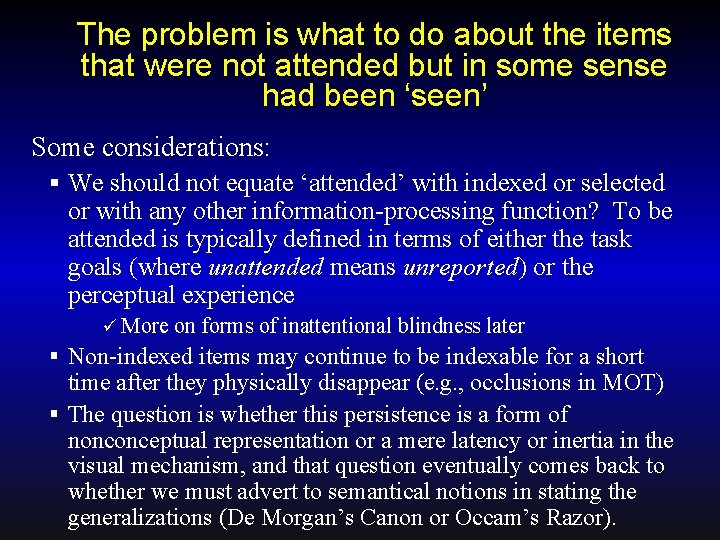

The problem is what to do about the items that were not attended but in some sense had been ‘seen’ Some considerations: § We should not equate ‘attended’ with indexed or selected or with any other information-processing function? To be attended is typically defined in terms of either the task goals (where unattended means unreported) or the perceptual experience ü More on forms of inattentional blindness later § Non-indexed items may continue to be indexable for a short time after they physically disappear (e. g. , occlusions in MOT) § The question is whether this persistence is a form of nonconceptual representation or a mere latency or inertia in the visual mechanism, and that question eventually comes back to whether we must advert to semantical notions in stating the generalizations (De Morgan’s Canon or Occam’s Razor).

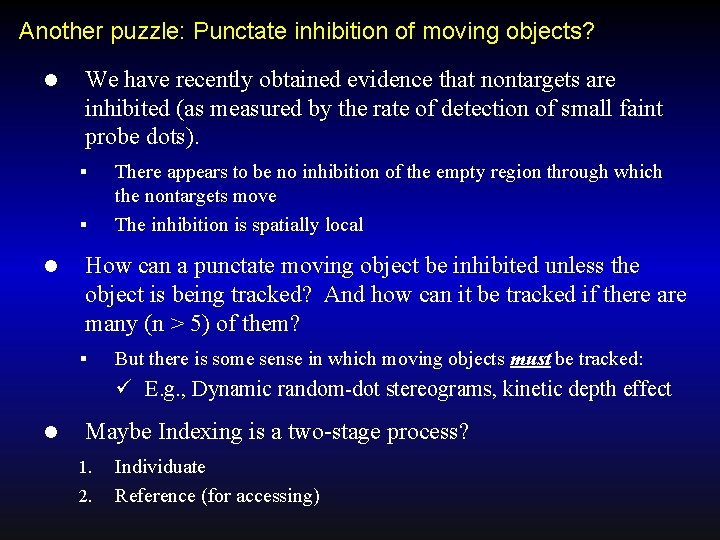

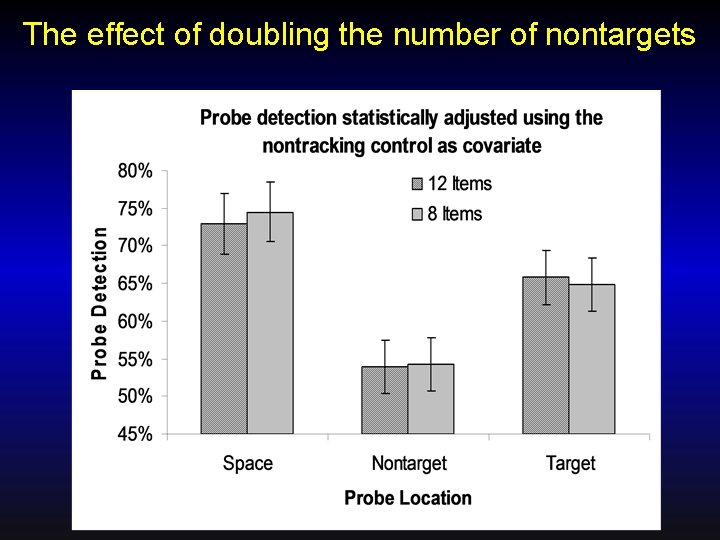

Another puzzle: Punctate inhibition of moving objects? l We have recently obtained evidence that nontargets are inhibited (as measured by the rate of detection of small faint probe dots). § § l There appears to be no inhibition of the empty region through which the nontargets move The inhibition is spatially local How can a punctate moving object be inhibited unless the object is being tracked? And how can it be tracked if there are many (n > 5) of them? § But there is some sense in which moving objects must be tracked: ü E. g. , Dynamic random-dot stereograms, kinetic depth effect l Maybe Indexing is a two-stage process? 1. 2. Individuate Reference (for accessing)

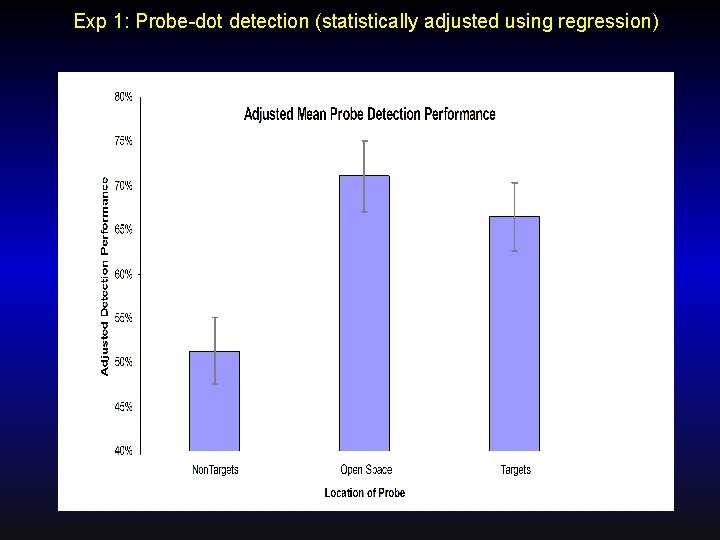

Exp 1: Probe-dot detection (statistically adjusted using regression)

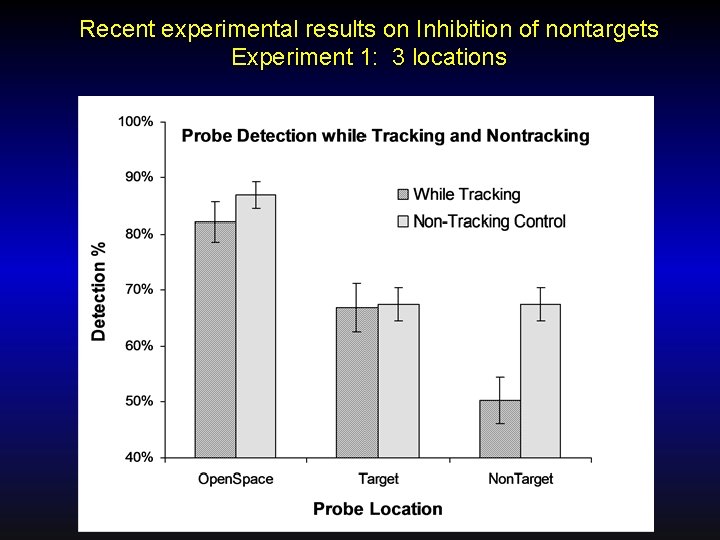

Recent experimental results on Inhibition of nontargets Experiment 1: 3 locations

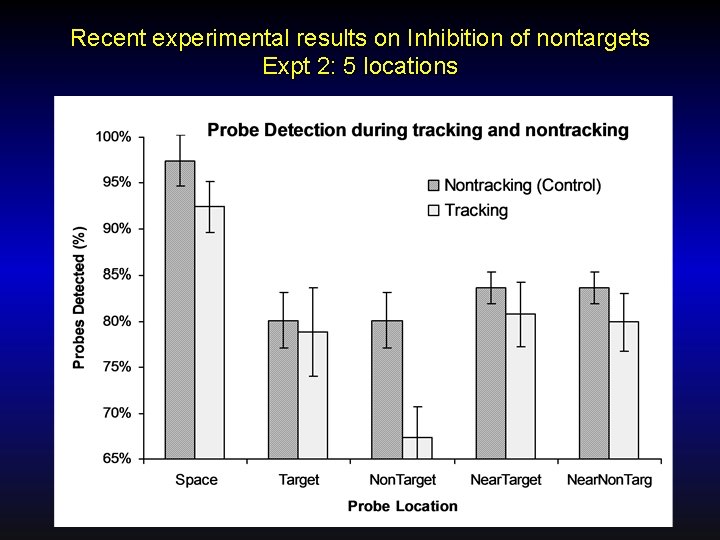

Recent experimental results on Inhibition of nontargets Expt 2: 5 locations

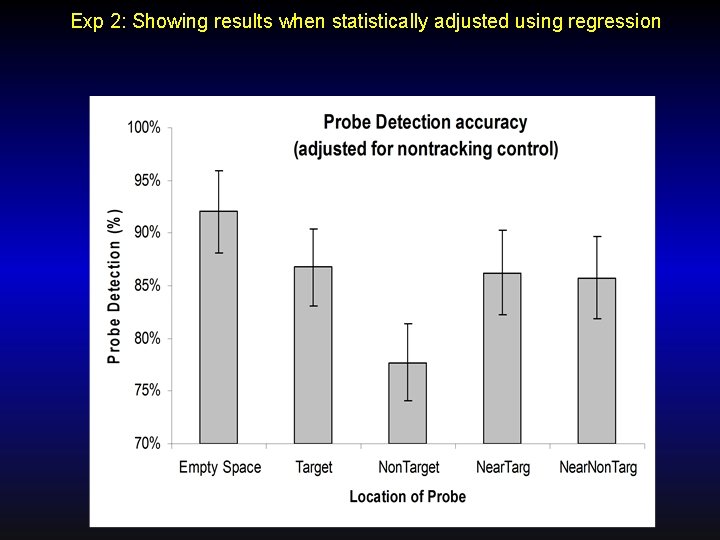

Exp 2: Showing results when statistically adjusted using regression

The effect of doubling the number of nontargets

The beginnings of the puzzle of individuating prior to indexing, and what that might mean! If moving objects are inhibited then inhibition moves along with the objects. How can this be unless they are being tracked? And if they are being tracked there must be at least 8 FINSTs! l This puzzle may signal the need for a kind of individuation that is weaker than the individuation we have discussed so far – a mere clustering, circumscribing, figure-ground distinction without a pointer or access mechanism – i. e. without reference! l It turns out that such a circumscribing-clustering process is needed to fulfill many different functions in early vision. It is needed whenever the correspondence problem arises – whenever visual elements need to be placed in correspondence or paired with other elements. This occurs in stereo, apparent motion, and other situations in which increasing the number of elements does not increase the difficulty of computing correspondences. l § Correspondence is not computed over continuous visual manifolds but only over some pre-clustered elements.

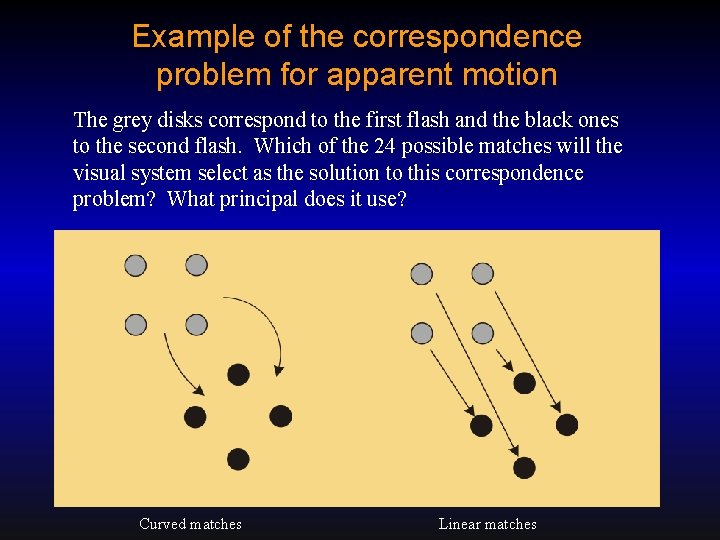

Example of the correspondence problem for apparent motion The grey disks correspond to the first flash and the black ones to the second flash. Which of the 24 possible matches will the visual system select as the solution to this correspondence problem? What principal does it use? Curved matches Linear matches

Here is how it actually looks

Why does the apparent motion take the form it does? The principle appears to be one of minimizing the vector difference between each possible correspondence pair and that of its nearest neighbors (Dawson & Pylyshyn, 1988) l This principle arises from (is justified by) the natural constraints of rigidity and opacity: l § In our kind of world most image features arise from distal elements on the surface of opaque rigid objects, i. e. , the vast majority of perceived distal elements are on the visible surface of opaque rigid objects § Therefore each distal element is likely to move the same amount and in the same direction as elements near to it (since they are likely to be on the same surface)

Views of a dome

Structure from Motion Demo Cylinder Kinetic Depth Effect

The correspondence problem for biological motion

Reprise … what are FINSTs? l l l They are a primitive reference mechanism that refer to individual objects in the world (FINGs? ) Objects are picked out and referred to without using any encoding of their properties, including their location. Picking out objects is prior to encoding their locations! Indexing is nonconceptual because it does not represent an individuals as a member of some conceptual category – not even as being in the category individual or object! FINSTs serve as visual demonstratives, much like the terms this or that do in language, by picking out and referring to individuals without using their properties. The central function of FINST indexes is to bind arguments of visual predicates or of motor commands to things in the world to which they must refer. Only predicates with bound arguments can be evaluated.

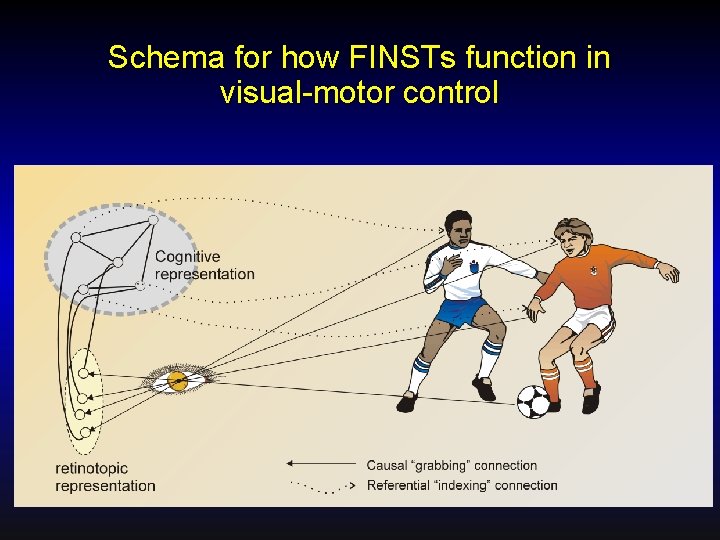

Schema for how FINSTs function in visual-motor control

- Slides: 120