Atoms Molecules and Ions Classification and Compositions of

- Slides: 70

Atoms, Molecules, and Ions • Classification and Compositions of Matter • Atomic Structures – Ancient Philosophy – Dalton’s Atomic Theory • • • Isotopes Periodic Table Molecules and Ions Types of Compounds Naming Compounds

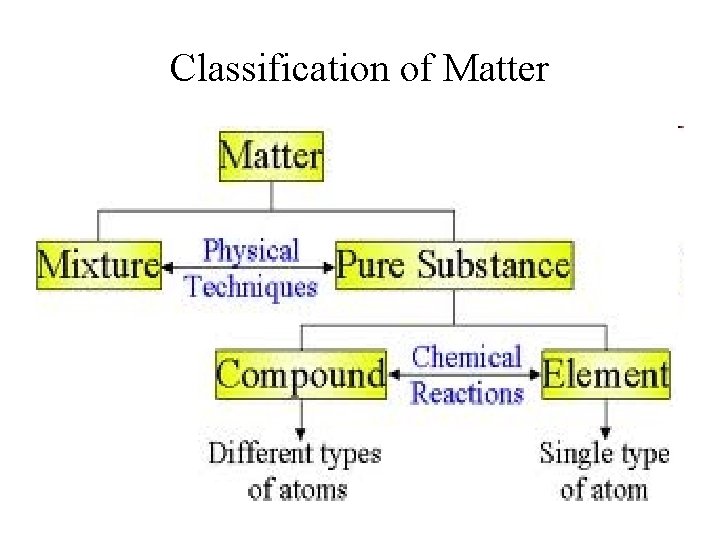

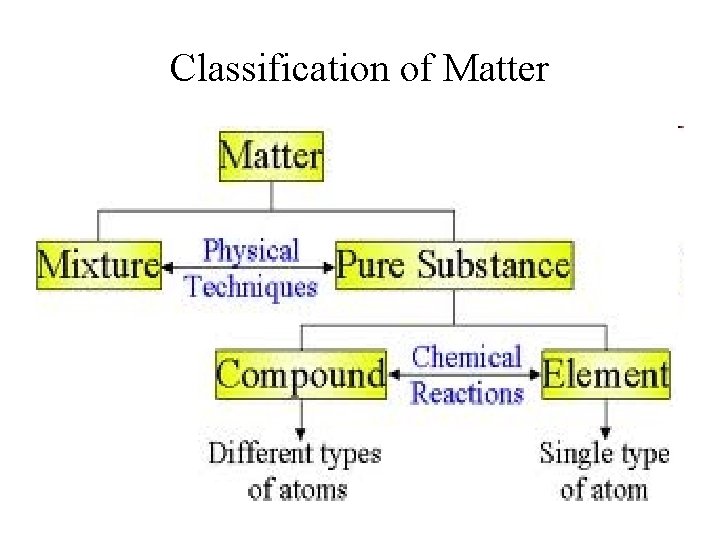

Classification of Matter

Matter According to Ancient Philosophy • Matter is composed of four basic elements: Earth, water, wind, and fire • Two schools of thought emerged during Greek Civilization: 1. Aristotle and his followers believed that matter to be infinite – not composed of discrete unit. 2. Democritus and Leucippus believed that matter is made of discrete units called “atomos” that is indivisible.

The “Development” of Theory • Many early 18 th Century chemists the combustion process; They “observed” that when a piece of wood burn, the mass of the ash formed is apparently less than that of the original wood. So, what happen to the rest of the mass of the wood?

The Phlogiston Theory • This is their theory to explain combustion: 1. Materials burn because they contains a substance called phlogiston; 2. During combustion the phlogiston is lost; 3. Thus, the mass of ash is less than the wood. Really? What did they forget to do before coming to that conclusion?

Experimental Science versus Philosophy • Antoine Lavoisier (1743 -1794) performed quantitative experiments to study combustion processes. The results showed that in all combustion reactions the masses of products to be greater than those of the material being burned. He concluded that: 1. The Phlogiston theory was incorrect; 2. Combustion involves oxygen gas – the gain in mass during combustion is due combination with oxygen; 3. Mass is conserved during chemical reactions.

Experimental Science versus Philosophy • Joseph Proust (1754 -1826) performed numerous experiments to analyze the compositions of compounds, and found that: a given compound has a constant composition (in mass %) regardless of its origin or sample size.

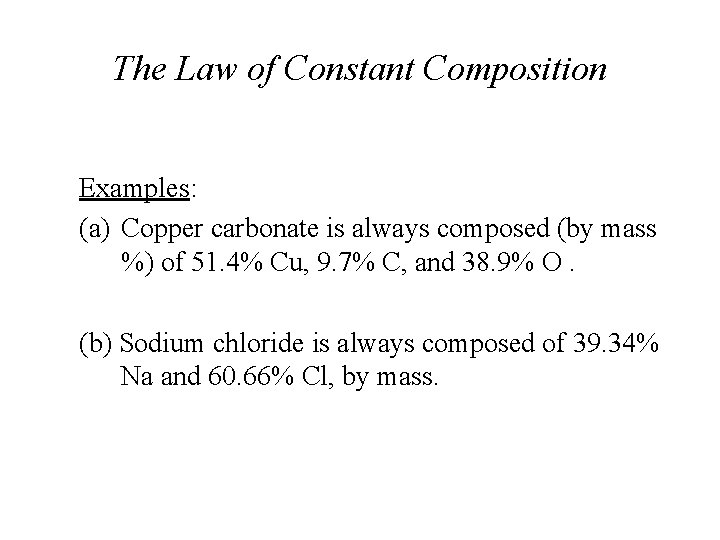

The Law of Constant Composition Examples: (a) Copper carbonate is always composed (by mass %) of 51. 4% Cu, 9. 7% C, and 38. 9% O. (b) Sodium chloride is always composed of 39. 34% Na and 60. 66% Cl, by mass.

Two Fundamental Laws of Matter • The Law of Conservation of Mass: During chemical reactions, the total mass of substances is conserved. (Mass is neither created or destroyed during chemical reaction. ) • The Law of Definite Proportions: A given compound always contains the same types of elements chemically combined in a fixed proportion by mass, regardless of its origin.

Dalton’s Atomic Theory (1805) 1. Elements are made up of discrete, indivisible particles, called atoms; 2. Atoms of the same element are identical, but are different for different elements; 3. A compounds is formed when atoms of different elements combined in simple whole number ratios; 4. The smallest unit of a given compound always contains the same number and type of atoms; 5. Atoms are not created or destroyed during chemical reactions.

Principle of Chemical Combination • Law of Multiple Proportion: When two elements react to form two or more compounds, a simple ratio exists in the masses of one of the elements that combine with a fixed mass of the second element in those compounds; Example: Carbon reacts with oxygen to form two compounds, X and Y. In X 1. 00 g of carbon combines with 1. 33 g of oxygen, and in Y 1. 00 g of carbon combines with 2. 66 g of oxygen. The mass ratio of oxygen in compounds X and Y is 1: 2. If X = CO, then Y = CO 2

Exercise #1: Law of Multiple Proportions • Sulfur reacts with fluorine to form three different compounds, A, B and C. In compound A, 1. 000 g of sulfur combines with 1. 185 g of fluorine; in B, 1. 000 g of sulfur combines with 2. 370 g of fluorine, and in C, 1. 000 g of sulfur combines with 3. 556 g of fluorine. Show that these data illustrate the law of multiple proportions. If the formula of compound A is SF 2, derive the formula of B and C.

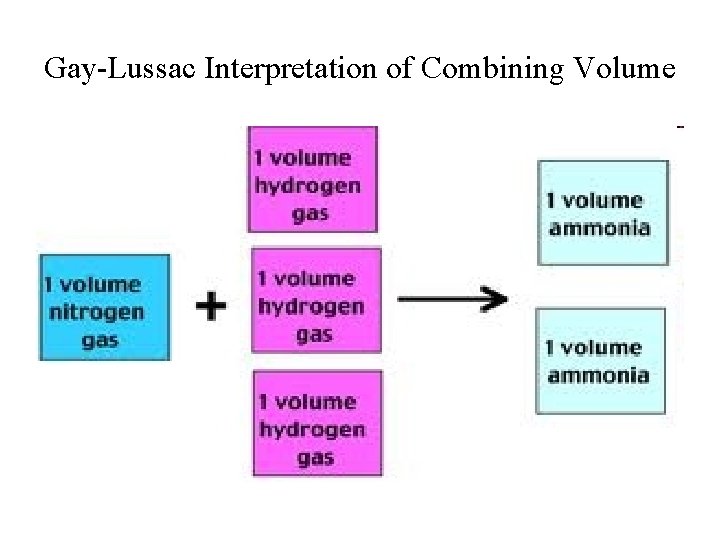

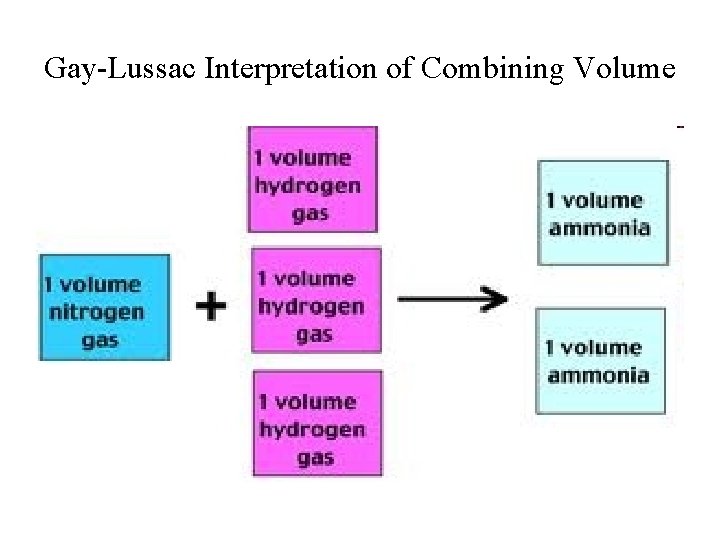

Gay-Lussac Interpretation of Combining Volume

Principle of Chemical Combination • Gay-Lussac’s Law of Combining Volumes: In reactions that involve gaseous reactants and products, there exist “simple ratios” of their volumes measured under the same temperature and pressure. Examples: 1. 1 volume of hydrogen reacts with 1 volume of chlorine to form 2 volumes of hydrogen chloride; 2. 2 volumes of hydrogen reacts with 1 volume of oxygen to form 2 volumes of water vapor.

Interpretation of Gay-Lussac’s Experiments • According to Avogadro’s law: “under same temperature and pressure, equal volumes of gases contain the same number of molecules” • 1 L of hydrogen + 1 L of chlorine 2 L of hydrogen chloride • This implies: 1 H-molecule + 1 Cl-molecule 2 HCl molecules. Hydrogen and chlorine molecules must be diatomic (2 atoms per molecule), and the reaction may be written as follows: H 2(g) + Cl 2(g) 2 HCl(g)

Interpretation of Gay-Lussac’s Experiments • 2 L of hydrogen + 1 L of oxygen 2 L of water vapor implies: 2 H-molecules + 1 O-molecule 2 water molecules. a) Hydrogen and oxygen gases contains diatomic molecules (H 2 and O 2), and water has the formula H 2 O. b) The above reaction can be represented by the equation: 2 H 2(g) + O 2(g) 2 H 2 O(g)

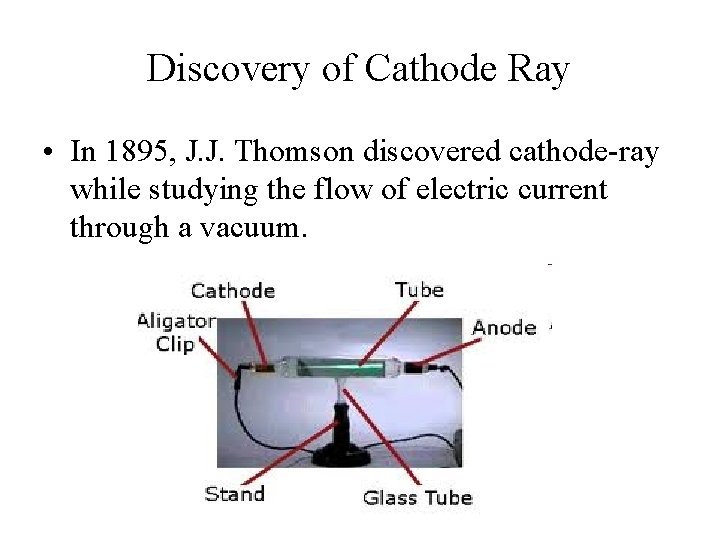

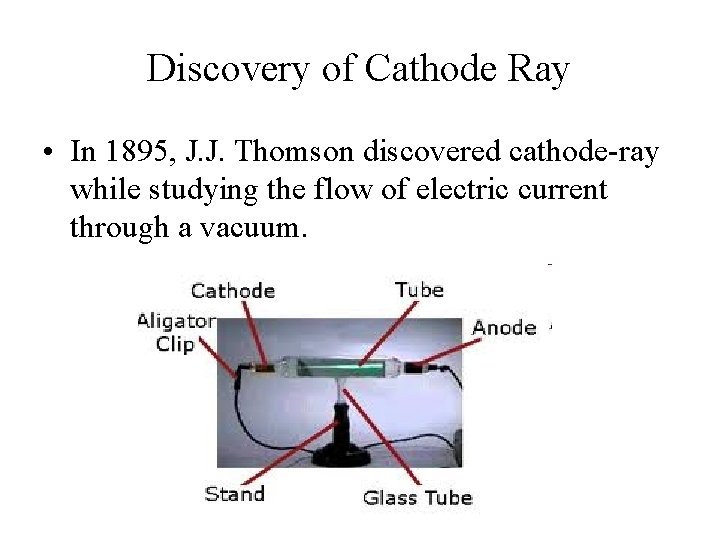

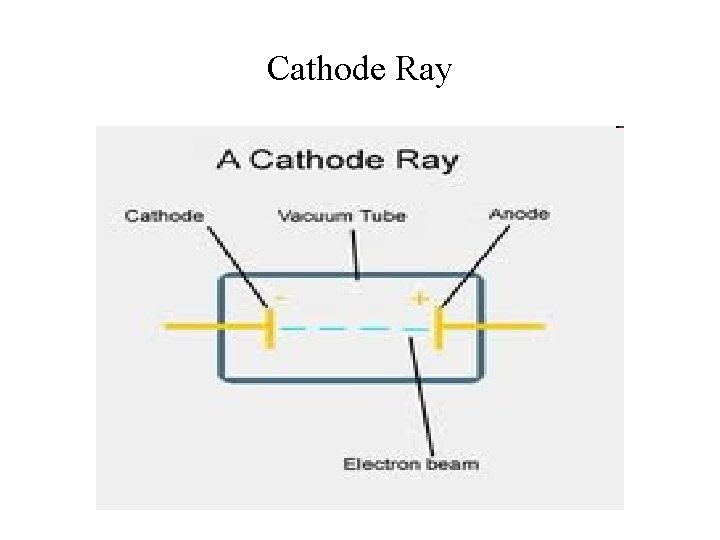

Discovery of Cathode Ray • In 1895, J. J. Thomson discovered cathode-ray while studying the flow of electric current through a vacuum.

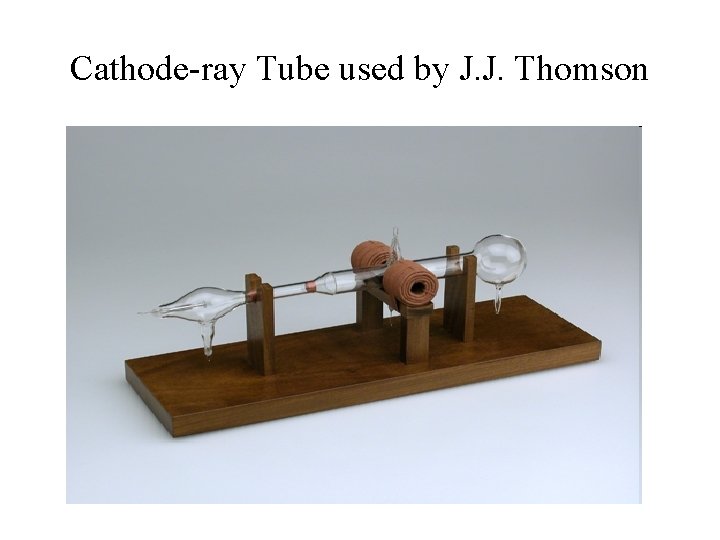

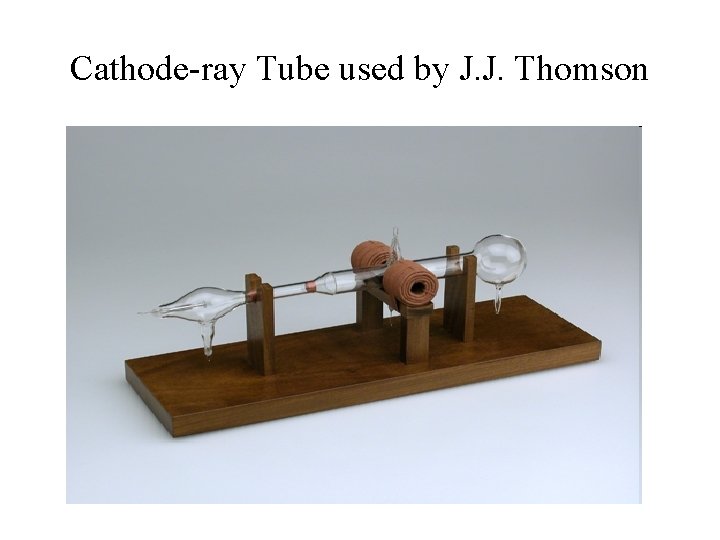

Cathode-ray Tube used by J. J. Thomson

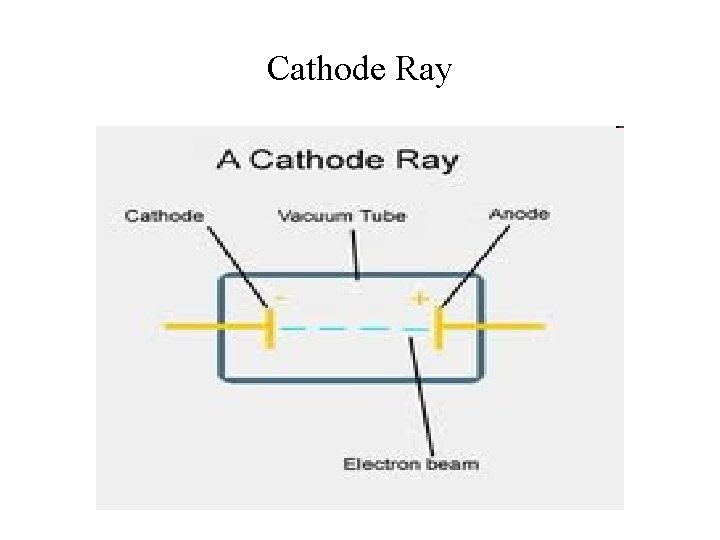

Cathode Ray

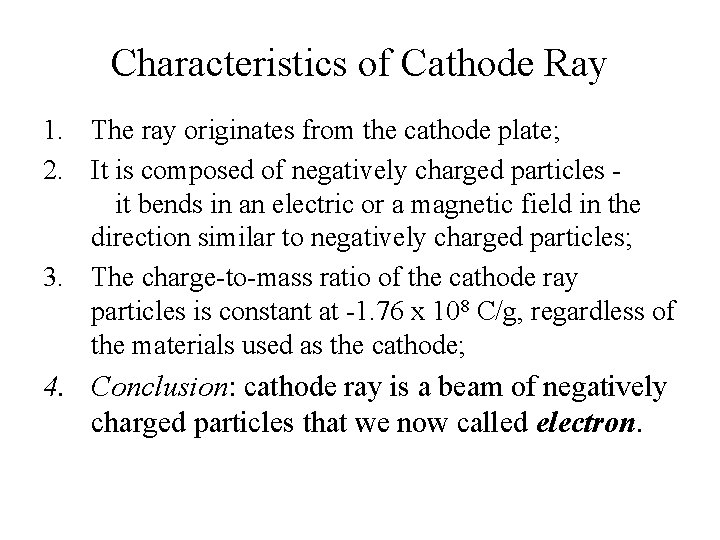

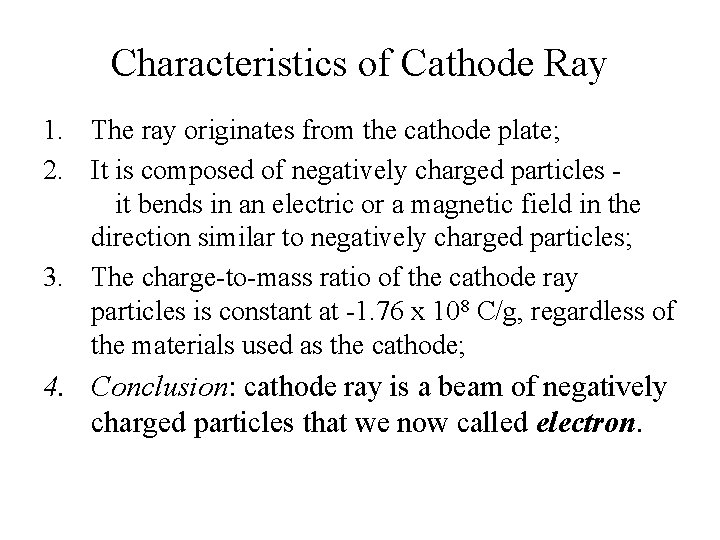

Characteristics of Cathode Ray 1. The ray originates from the cathode plate; 2. It is composed of negatively charged particles it bends in an electric or a magnetic field in the direction similar to negatively charged particles; 3. The charge-to-mass ratio of the cathode ray particles is constant at -1. 76 x 108 C/g, regardless of the materials used as the cathode; 4. Conclusion: cathode ray is a beam of negatively charged particles that we now called electron.

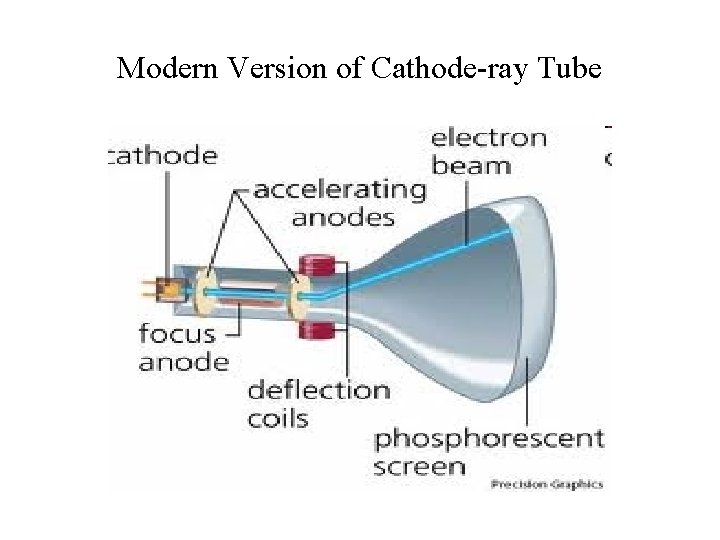

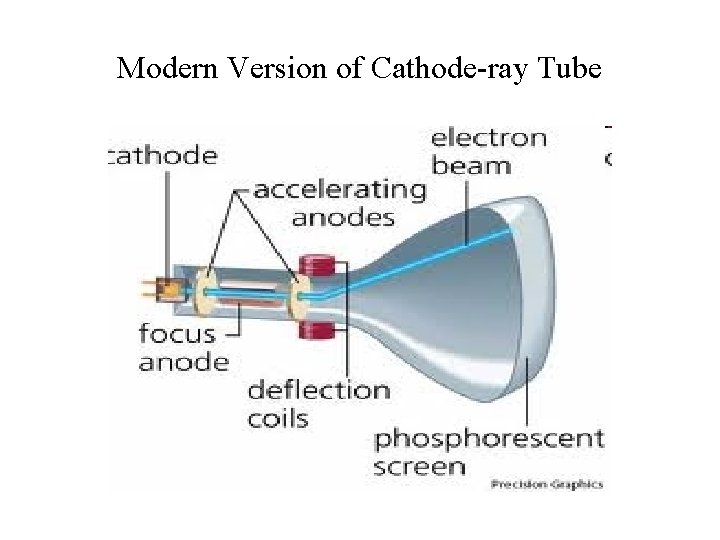

Modern Version of Cathode-ray Tube

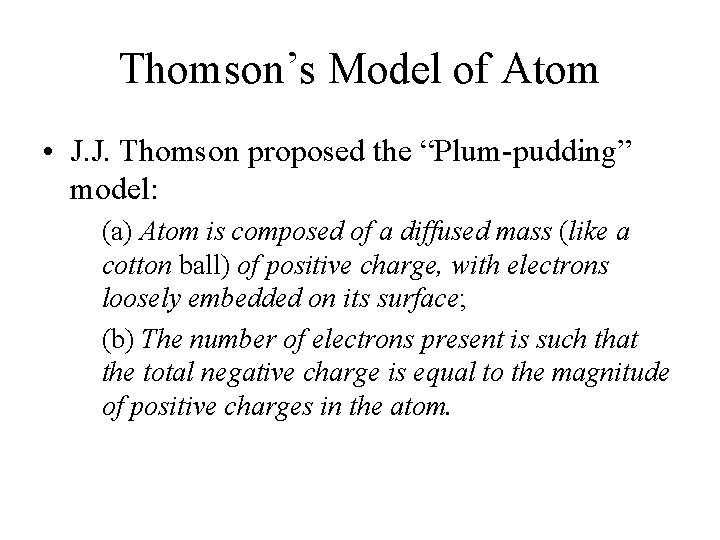

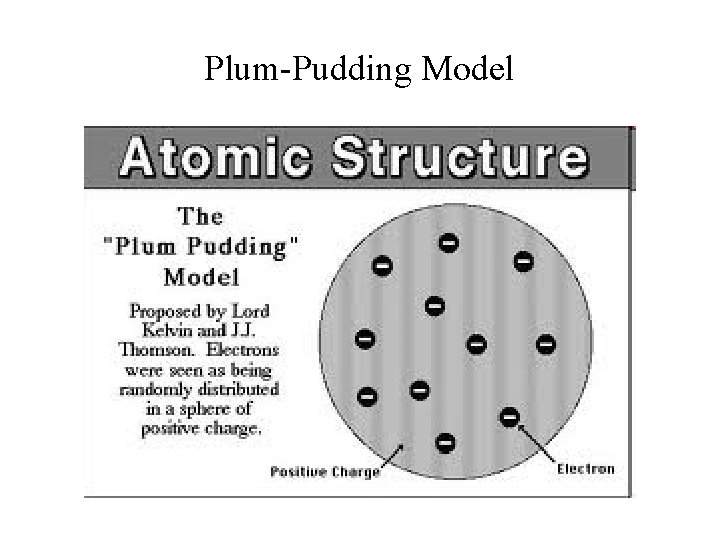

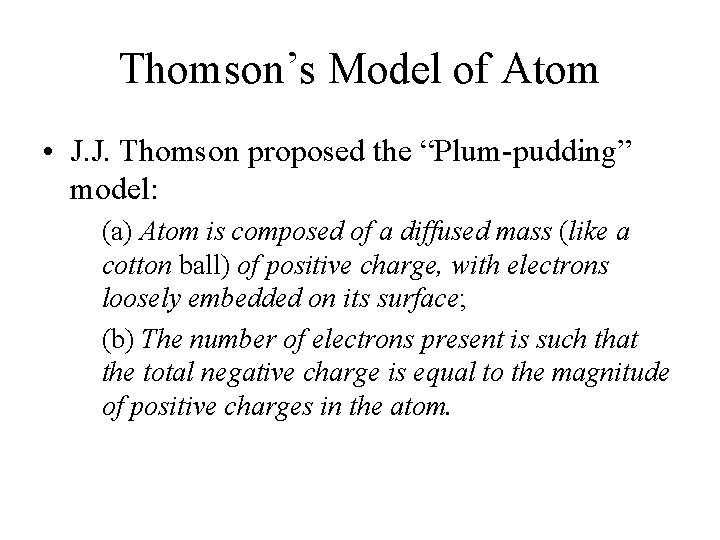

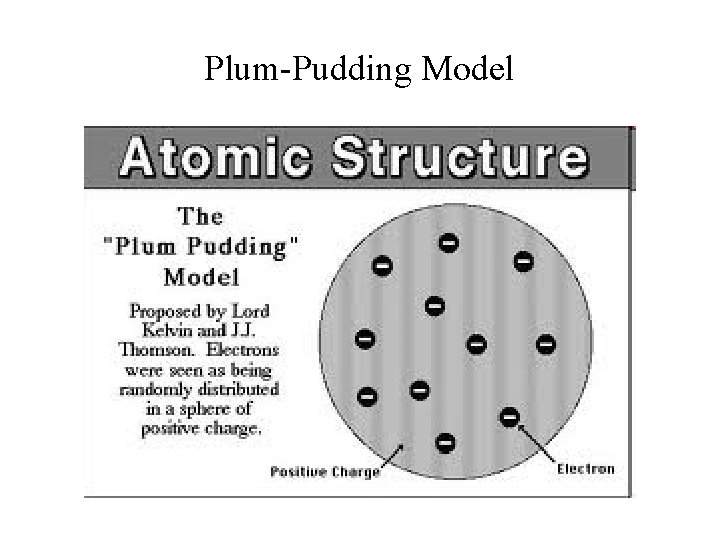

Thomson’s Model of Atom • J. J. Thomson proposed the “Plum-pudding” model: (a) Atom is composed of a diffused mass (like a cotton ball) of positive charge, with electrons loosely embedded on its surface; (b) The number of electrons present is such that the total negative charge is equal to the magnitude of positive charges in the atom.

Plum-Pudding Model

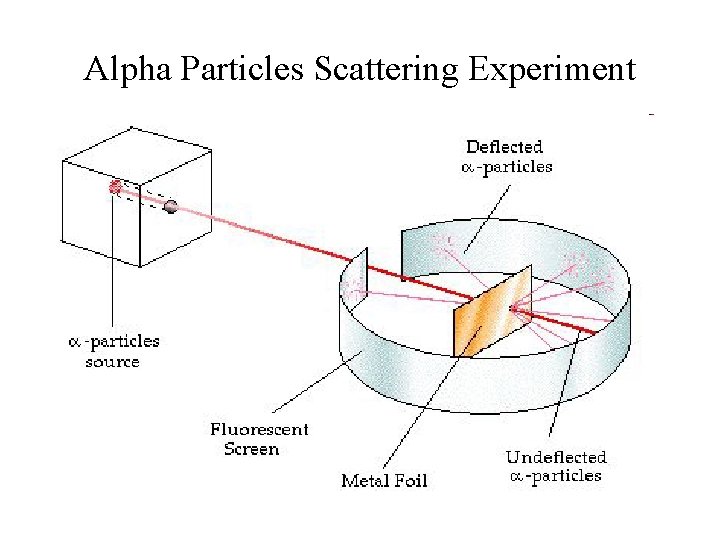

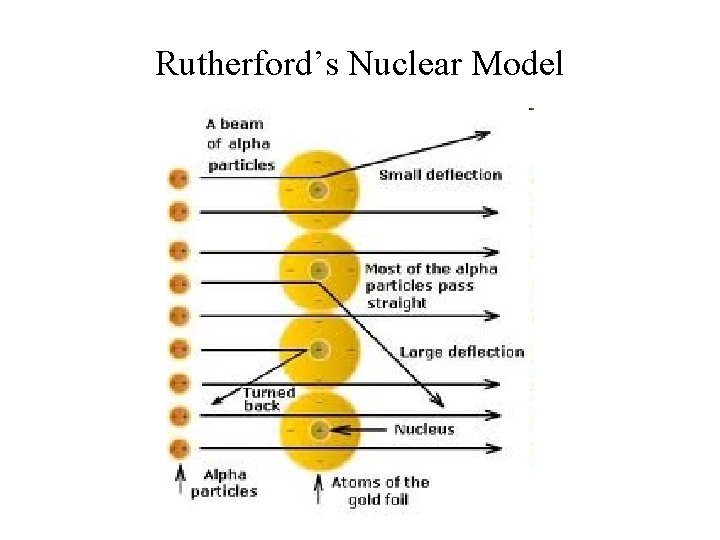

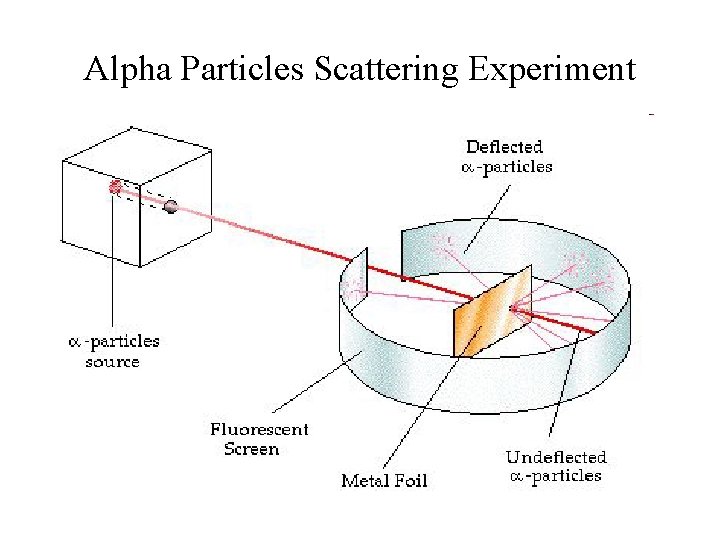

Alpha Particles Scattering Experiment

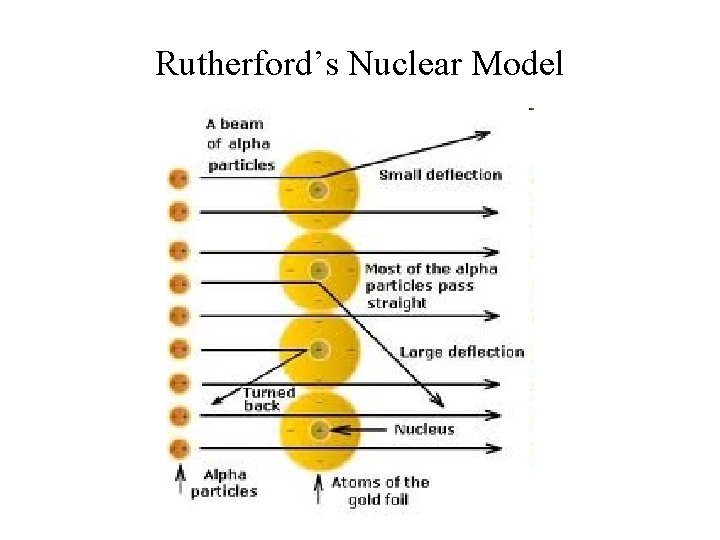

Rutherford’s Nuclear Model

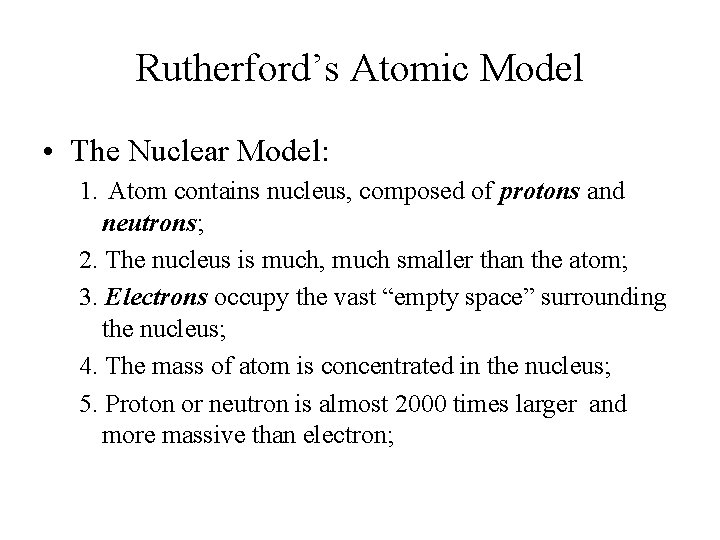

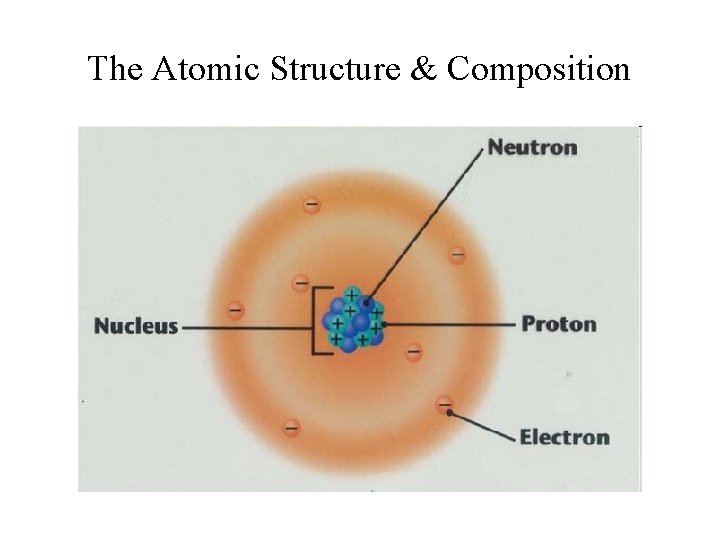

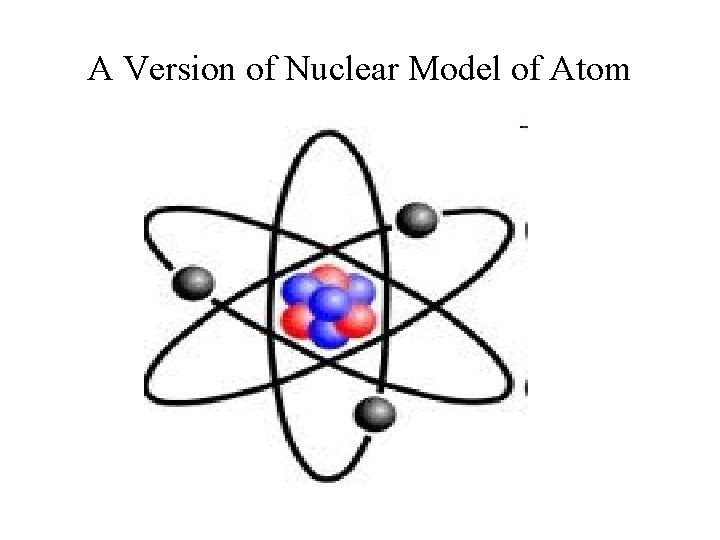

Rutherford’s Atomic Model • The Nuclear Model: 1. Atom contains nucleus, composed of protons and neutrons; 2. The nucleus is much, much smaller than the atom; 3. Electrons occupy the vast “empty space” surrounding the nucleus; 4. The mass of atom is concentrated in the nucleus; 5. Proton or neutron is almost 2000 times larger and more massive than electron;

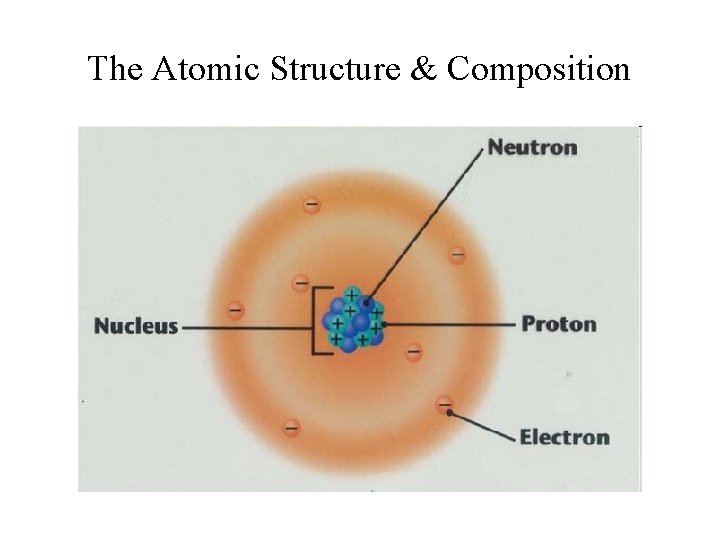

The Atomic Structure & Composition

A Version of Nuclear Model of Atom

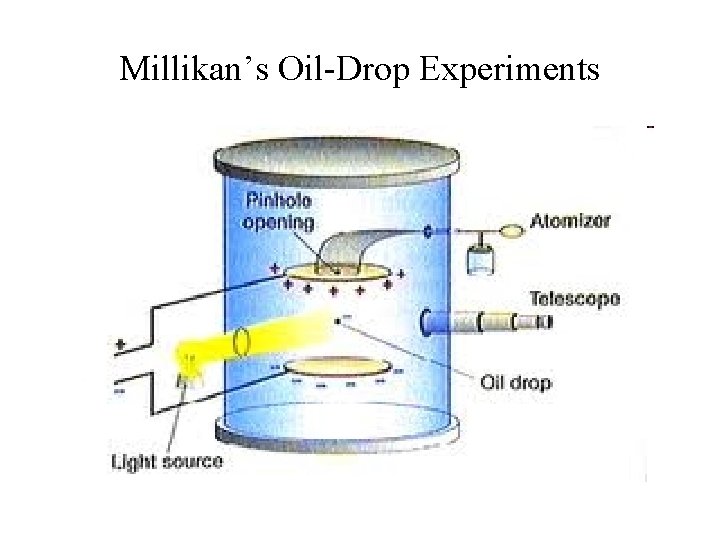

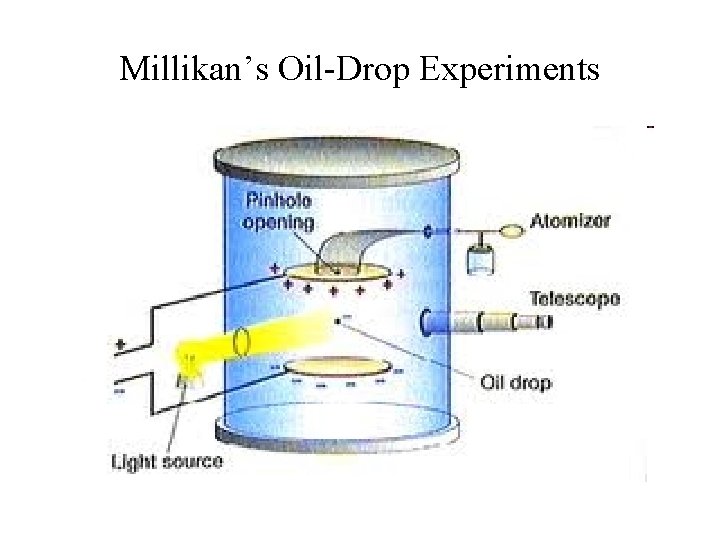

Millikan’s Oil-Drop Experiments

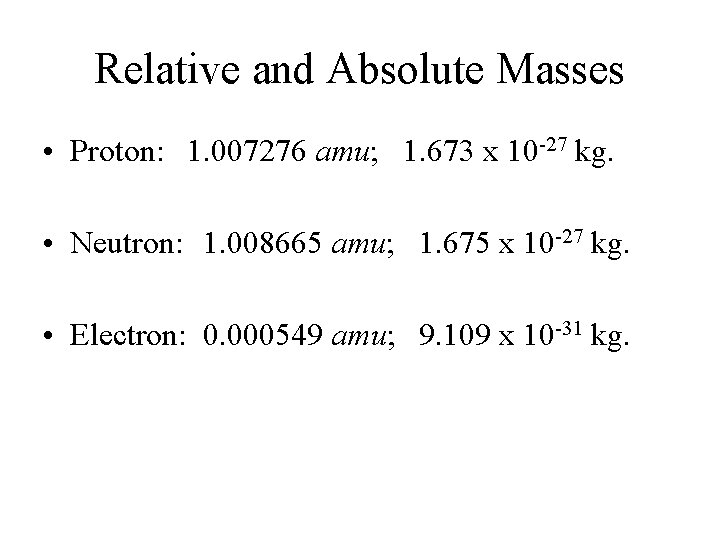

Relative and Absolute Masses • Proton: 1. 007276 amu; 1. 673 x 10 -27 kg. • Neutron: 1. 008665 amu; 1. 675 x 10 -27 kg. • Electron: 0. 000549 amu; 9. 109 x 10 -31 kg.

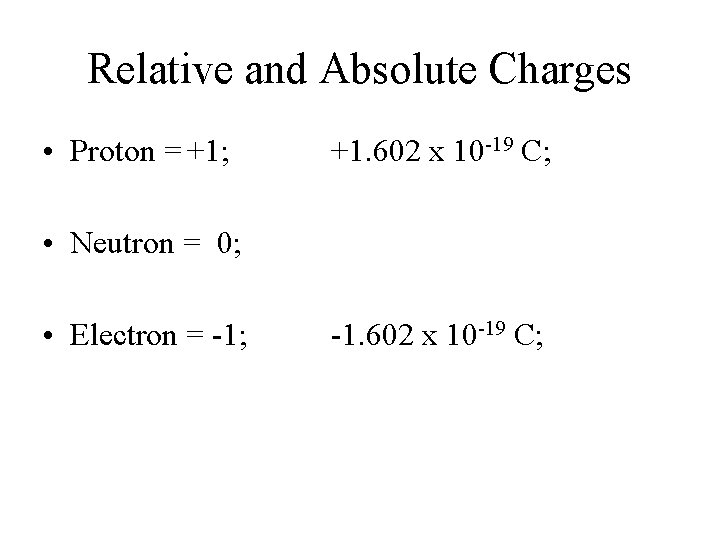

Relative and Absolute Charges • Proton = +1; +1. 602 x 10 -19 C; • Neutron = 0; • Electron = -1; -1. 602 x 10 -19 C;

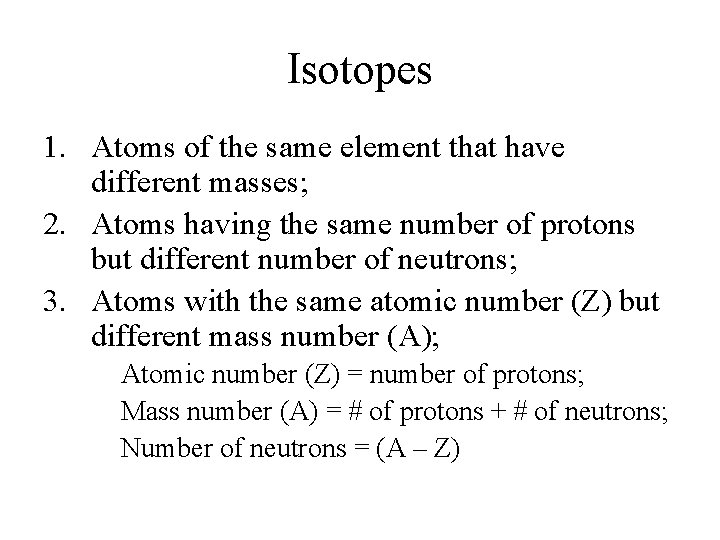

Isotopes 1. Atoms of the same element that have different masses; 2. Atoms having the same number of protons but different number of neutrons; 3. Atoms with the same atomic number (Z) but different mass number (A); Atomic number (Z) = number of protons; Mass number (A) = # of protons + # of neutrons; Number of neutrons = (A – Z)

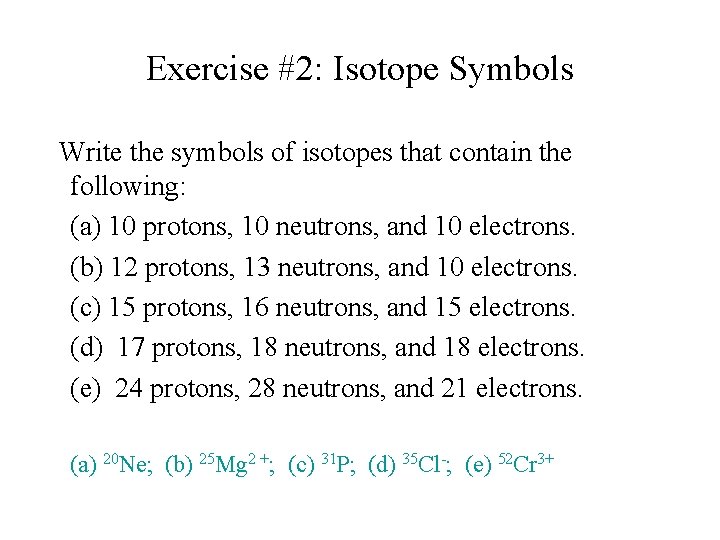

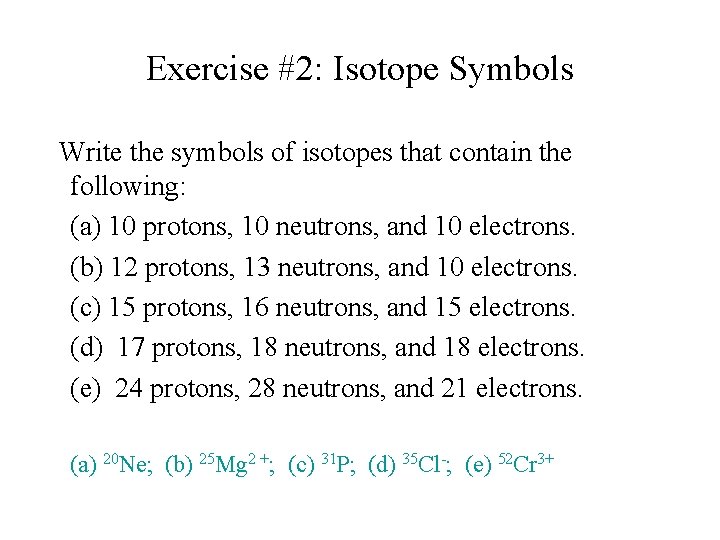

Exercise #2: Isotope Symbols Write the symbols of isotopes that contain the following: (a) 10 protons, 10 neutrons, and 10 electrons. (b) 12 protons, 13 neutrons, and 10 electrons. (c) 15 protons, 16 neutrons, and 15 electrons. (d) 17 protons, 18 neutrons, and 18 electrons. (e) 24 protons, 28 neutrons, and 21 electrons. (a) 20 Ne; (b) 25 Mg 2 +; (c) 31 P; (d) 35 Cl-; (e) 52 Cr 3+

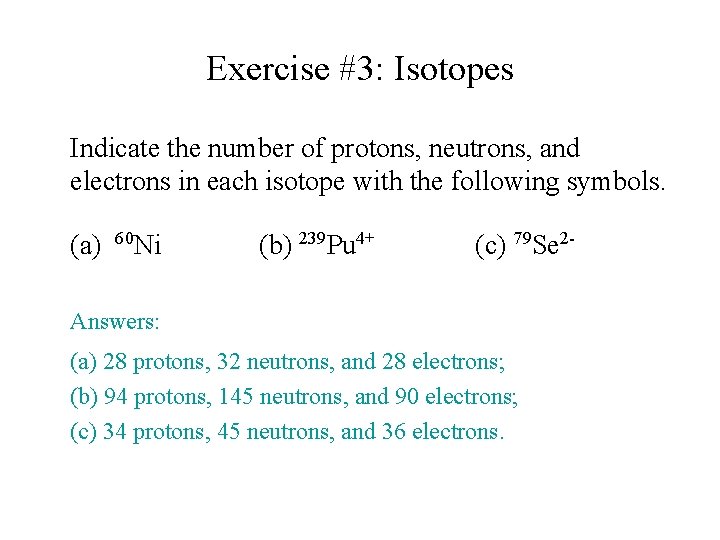

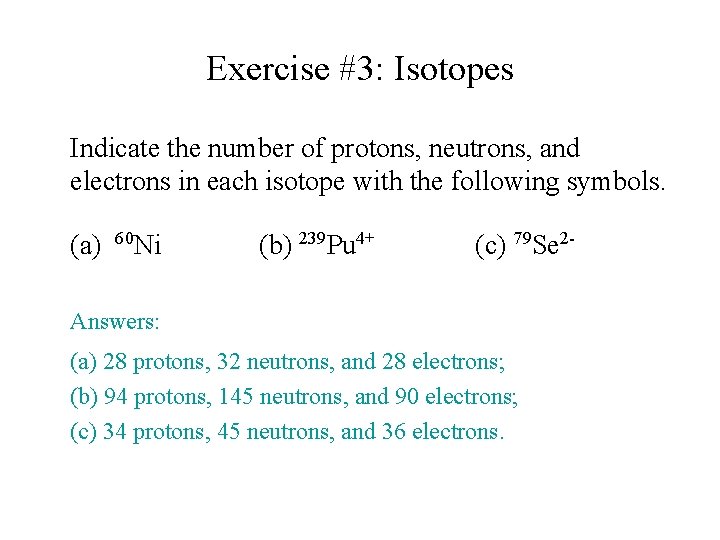

Exercise #3: Isotopes Indicate the number of protons, neutrons, and electrons in each isotope with the following symbols. (a) 60 Ni (b) 239 Pu 4+ (c) 79 Se 2 - Answers: (a) 28 protons, 32 neutrons, and 28 electrons; (b) 94 protons, 145 neutrons, and 90 electrons; (c) 34 protons, 45 neutrons, and 36 electrons.

Molecules and Ions • Molecule: A neutral particle that contains two or more atoms bound together (chemically) by covalent bonds. • Ion: Electrically charged particle, either positive (called cation) or negative (called anion) An atom may lose one or more electrons to form a cation, or may gain electrons to form anions.

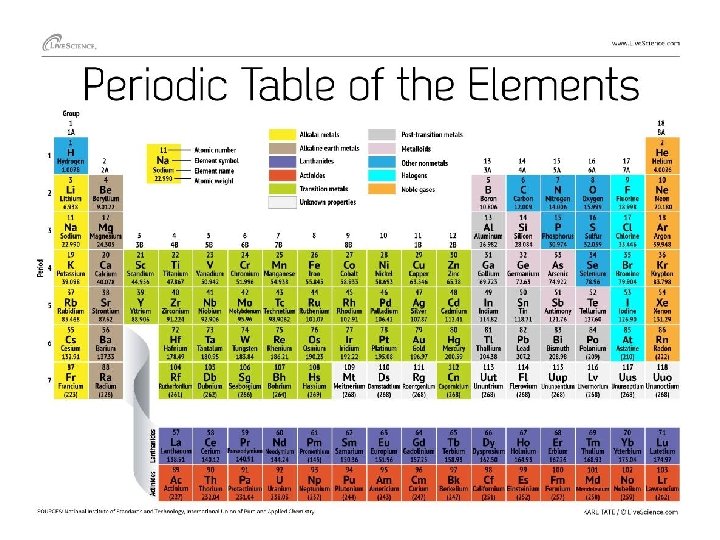

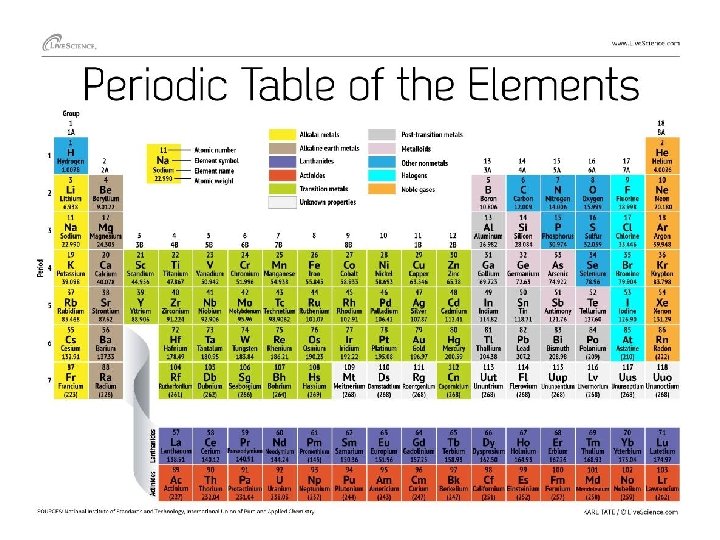

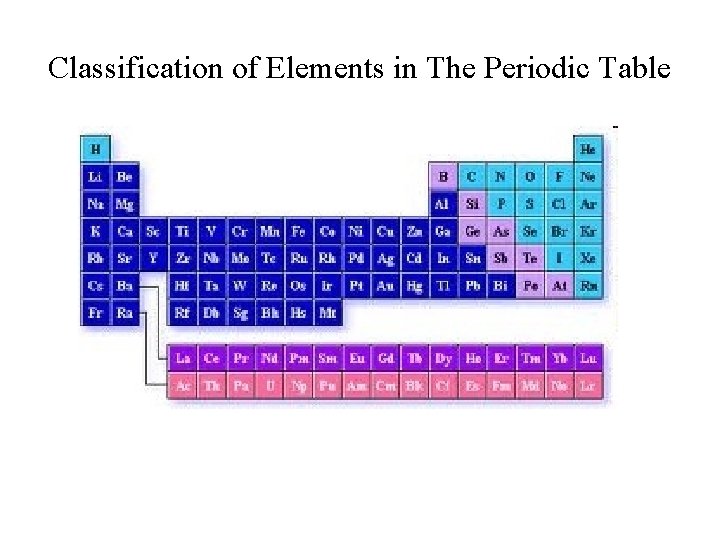

Periodic Table • The modern Periodic Table is divided into 18 columns (groups) and 7 rows (periods). • Groups are numbered 1 – 18 in the IUPAC configuration, or 1 A – 8 A and 1 B – 8 B in the ACS configuration. • In each period, elements are arranged left-toright in increasing atomic number; • Within each group, elements share similar chemical and physical characteristics.

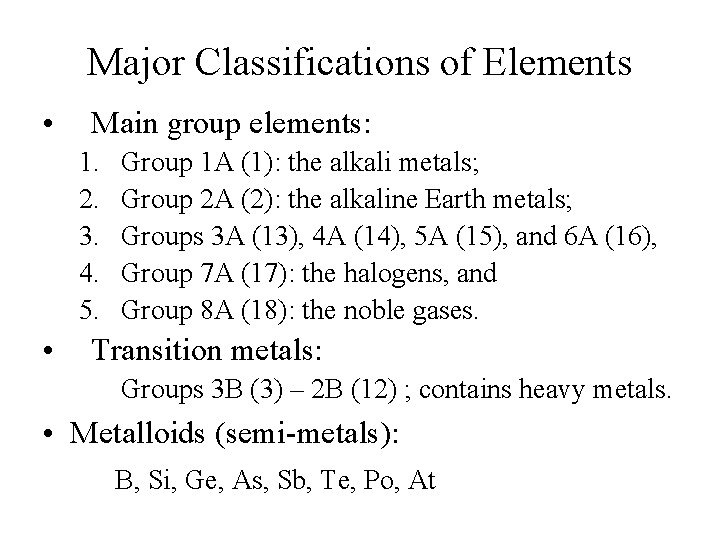

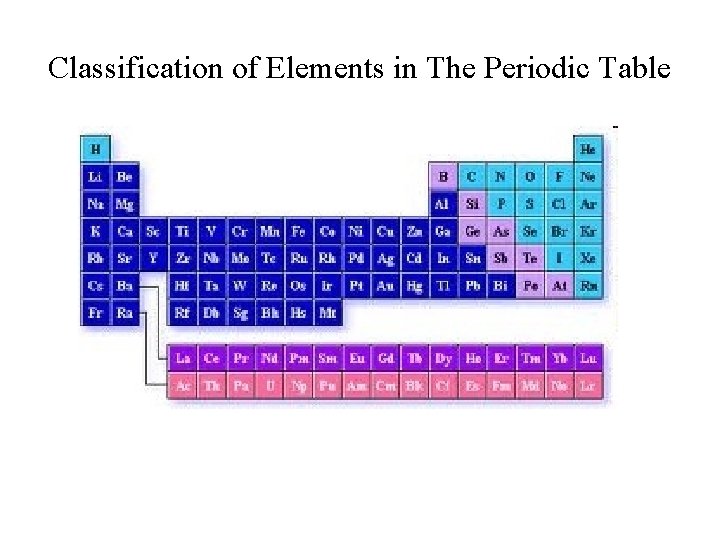

Major Classifications of Elements • Main group elements: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. • Group 1 A (1): the alkali metals; Group 2 A (2): the alkaline Earth metals; Groups 3 A (13), 4 A (14), 5 A (15), and 6 A (16), Group 7 A (17): the halogens, and Group 8 A (18): the noble gases. Transition metals: Groups 3 B (3) – 2 B (12) ; contains heavy metals. • Metalloids (semi-metals): B, Si, Ge, As, Sb, Te, Po, At

Classification of Elements in The Periodic Table

Characteristics of Metals, Nonmetals & Metalloids • Metals: 1. Mainly solid, except for mercury; have shiny appearance; 2. Good conductors of heat and electricity; 3. Malleable and ductile; 4. Metals only react with nonmetals; 5. The metals lose electrons and become cations; 6. The reaction products are ionic compounds; 7. Metals cannot react with one another.

Characteristics of Metals, Nonmetals & Metalloids • Nonmetals: 1. Mainly gases, one (bromine) is liquid, and few are solids; 2. Generally poor conductors of electricity; 3. Solids are generally brittle and not lustrous. 4. In reactions with metals, nonmetals gain electrons to become anions; 5. Nonmetals also react with one another or with metalloids to form molecular compounds.

Characteristics of Metals, Nonmetals & Metalloids • Metalloids (semi-metals): 1. Very hard (covalent network) solids; 2. physically look like metals, but chemically behave like nonmetals; 3. Metalloids only react with nonmetals to form molecular compounds.

More on Classifications of Elements • Lanthanide series: Elements after lanthanum (La): Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu; • Actinide series: 1. Elements after actinium (Ac): Th, Pa, U, Pu, Am, Cm, Bk, Cf, Es, Fm, Md, No, and Lr; 2. Mostly synthesized in particle accelerators and all are radioactive;

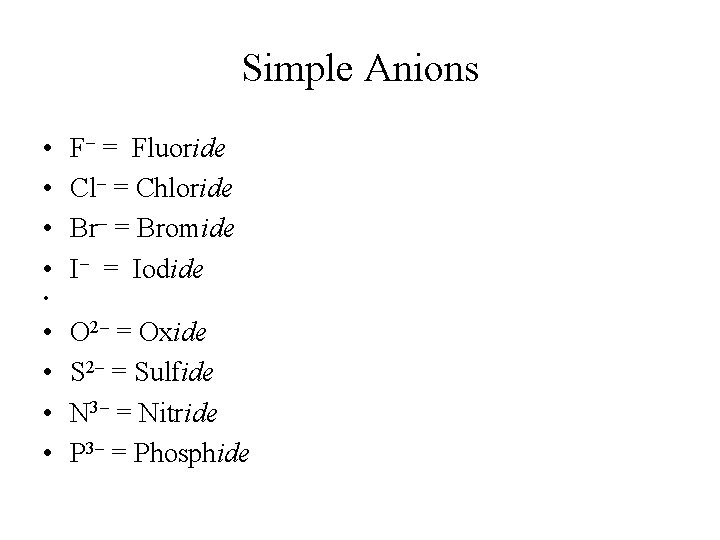

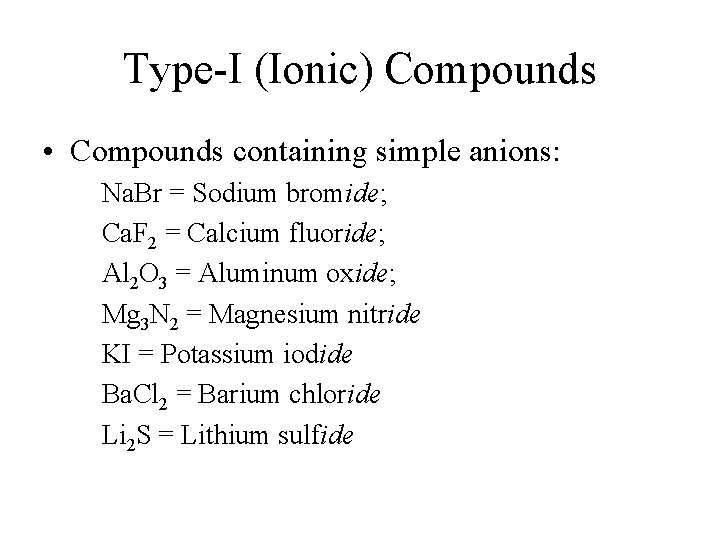

Formula & Naming System • Ionic Compounds: 1. 2. 3. 4. Formula: cation (metal) first, followed by anion; Naming: name cation first, followed by anion Name of cations: same as name of elements; Name of anions: take first syllable of element’s name and add ide; Examples: oxygen becomes oxide; chlorine becomes chloride; sulfur becomes sulfide, etc…

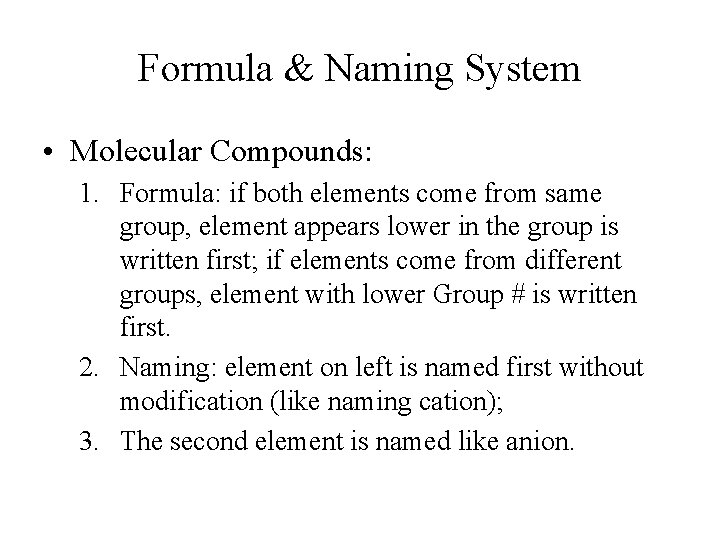

Formula & Naming System • Molecular Compounds: 1. Formula: if both elements come from same group, element appears lower in the group is written first; if elements come from different groups, element with lower Group # is written first. 2. Naming: element on left is named first without modification (like naming cation); 3. The second element is named like anion.

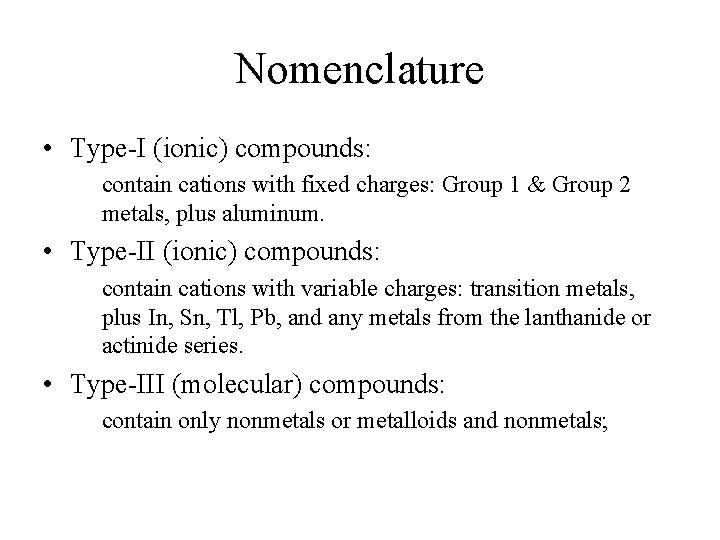

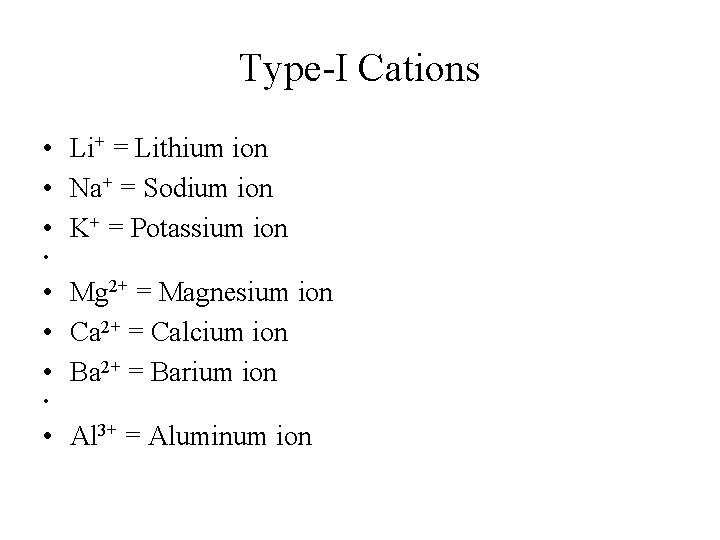

Nomenclature • Type-I (ionic) compounds: contain cations with fixed charges: Group 1 & Group 2 metals, plus aluminum. • Type-II (ionic) compounds: contain cations with variable charges: transition metals, plus In, Sn, Tl, Pb, and any metals from the lanthanide or actinide series. • Type-III (molecular) compounds: contain only nonmetals or metalloids and nonmetals;

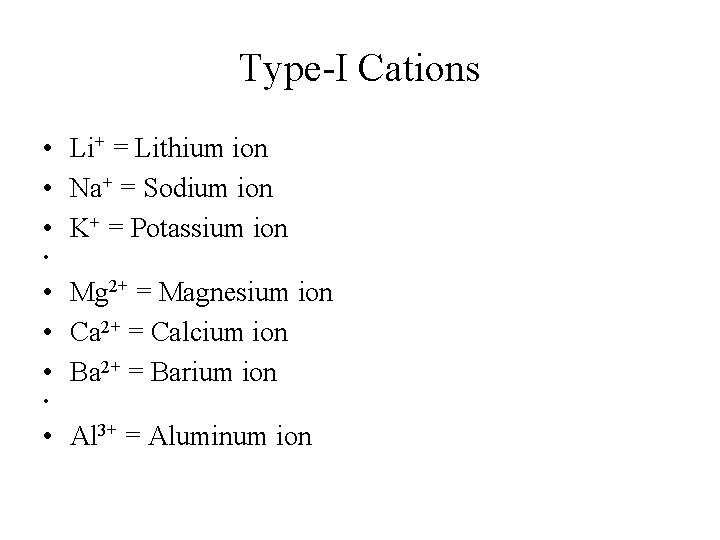

Type-I Cations • Li+ = Lithium ion • Na+ = Sodium ion • K+ = Potassium ion • • Mg 2+ = Magnesium ion • Ca 2+ = Calcium ion • Ba 2+ = Barium ion • • Al 3+ = Aluminum ion

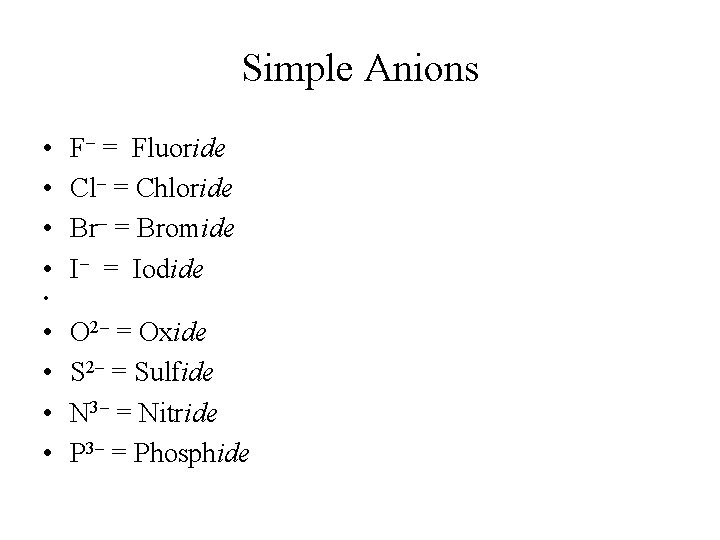

Simple Anions • • F– = Fluoride Cl– = Chloride Br– = Bromide I– = Iodide • • • O 2– = Oxide S 2– = Sulfide N 3– = Nitride P 3– = Phosphide

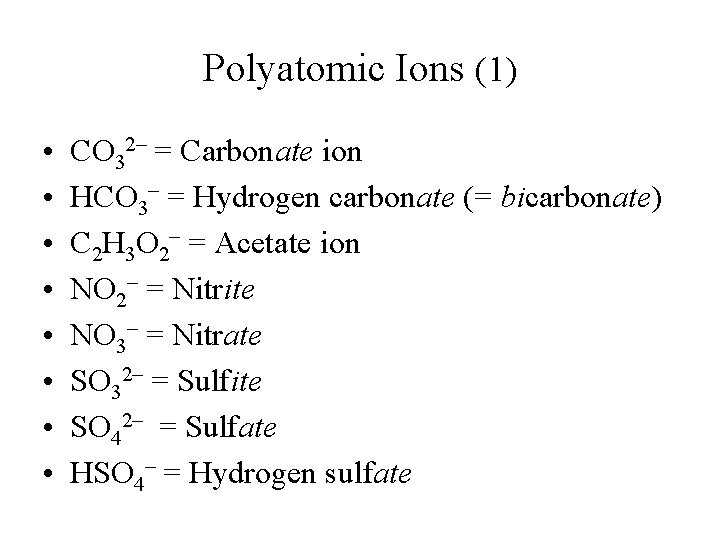

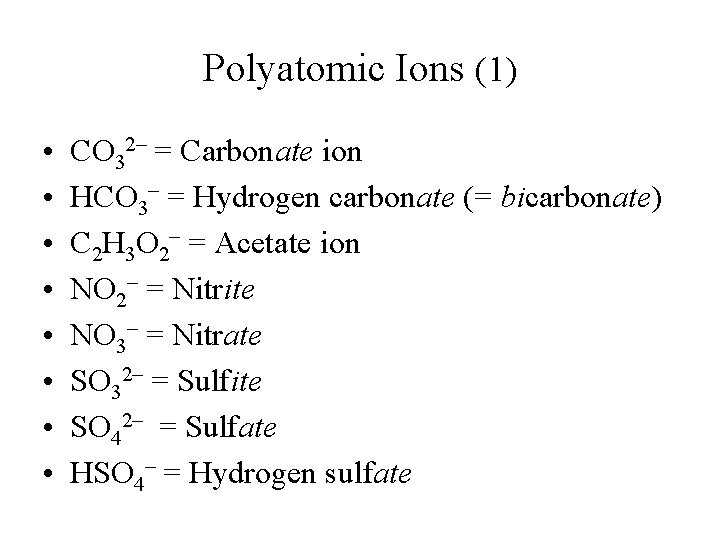

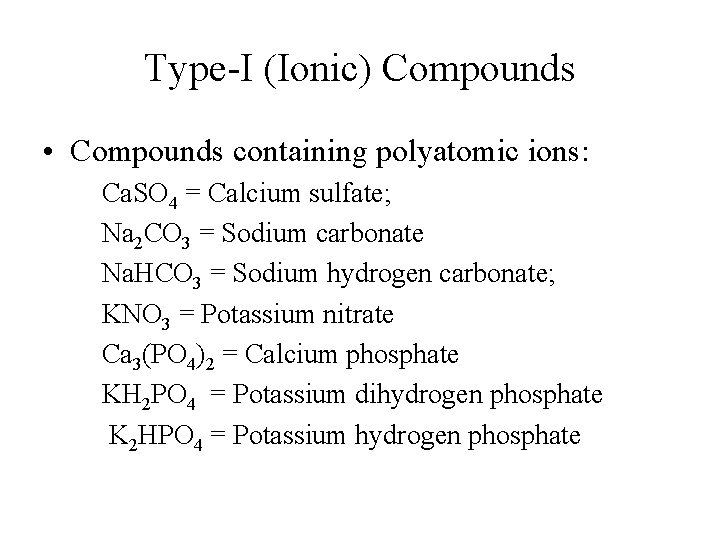

Polyatomic Ions (1) • • CO 32– = Carbonate ion HCO 3– = Hydrogen carbonate (= bicarbonate) C 2 H 3 O 2– = Acetate ion NO 2– = Nitrite NO 3– = Nitrate SO 32– = Sulfite SO 42– = Sulfate HSO 4– = Hydrogen sulfate

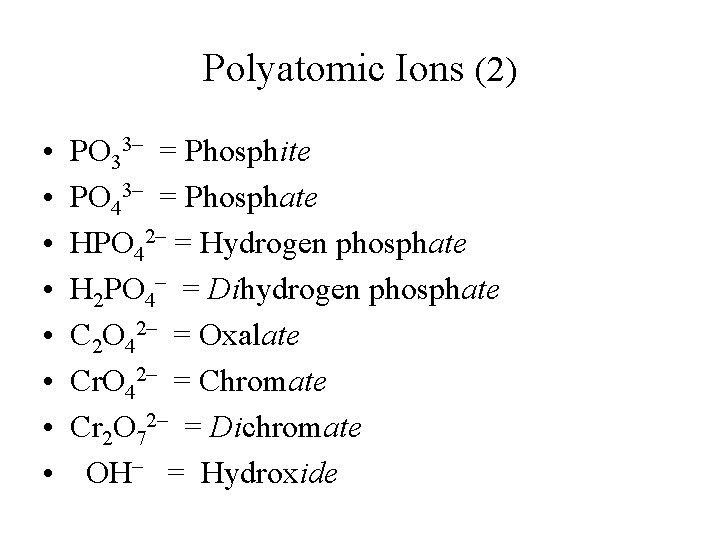

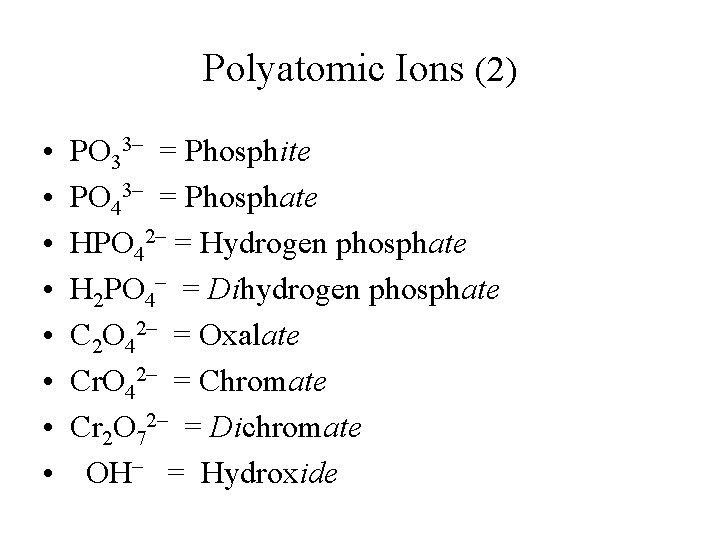

Polyatomic Ions (2) • • PO 33– = Phosphite PO 43– = Phosphate HPO 42– = Hydrogen phosphate H 2 PO 4– = Dihydrogen phosphate C 2 O 42– = Oxalate Cr. O 42– = Chromate Cr 2 O 72– = Dichromate OH– = Hydroxide

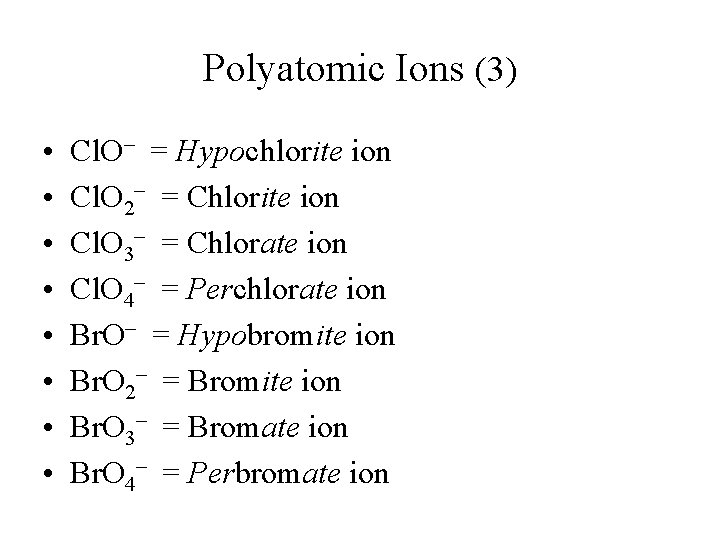

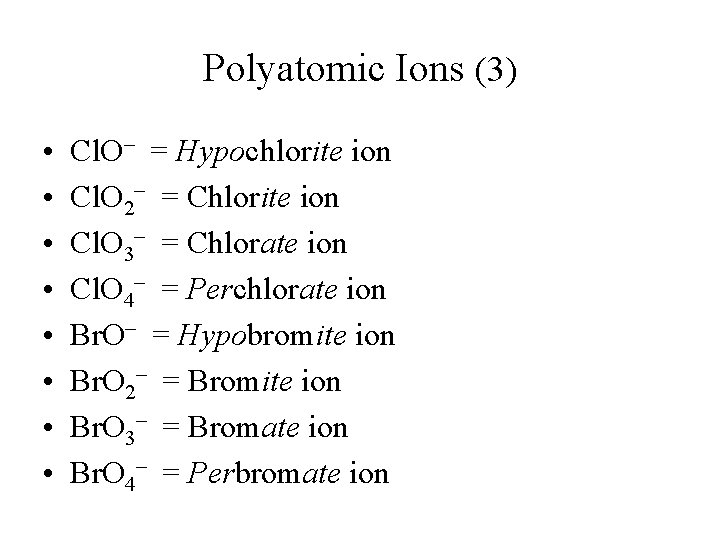

Polyatomic Ions (3) • • Cl. O– = Hypochlorite ion Cl. O 2– = Chlorite ion Cl. O 3– = Chlorate ion Cl. O 4– = Perchlorate ion Br. O– = Hypobromite ion Br. O 2– = Bromite ion Br. O 3– = Bromate ion Br. O 4– = Perbromate ion

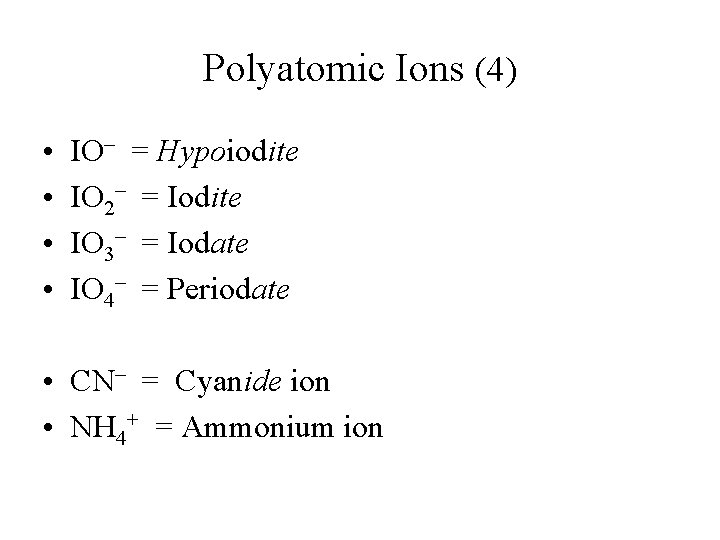

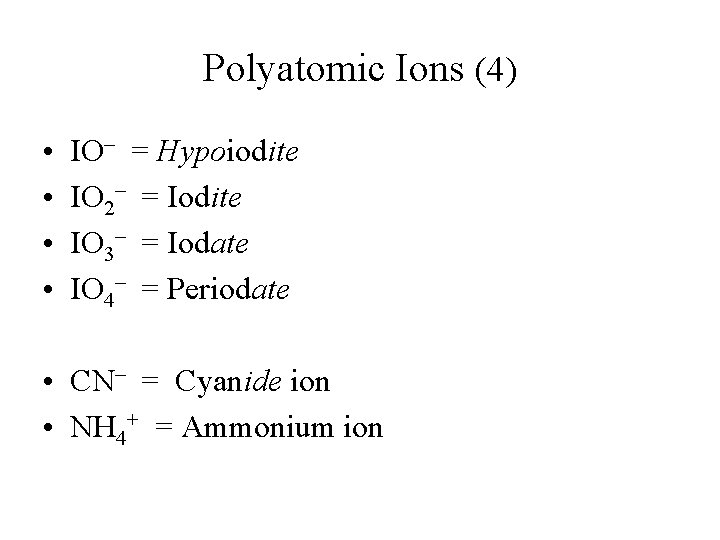

Polyatomic Ions (4) • • IO– = Hypoiodite IO 2– = Iodite IO 3– = Iodate IO 4– = Periodate • CN– = Cyanide ion • NH 4+ = Ammonium ion

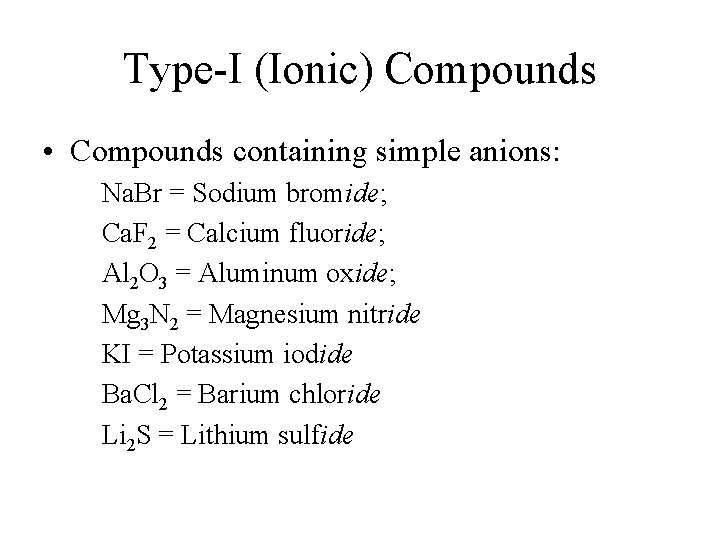

Type-I (Ionic) Compounds • Compounds containing simple anions: Na. Br = Sodium bromide; Ca. F 2 = Calcium fluoride; Al 2 O 3 = Aluminum oxide; Mg 3 N 2 = Magnesium nitride KI = Potassium iodide Ba. Cl 2 = Barium chloride Li 2 S = Lithium sulfide

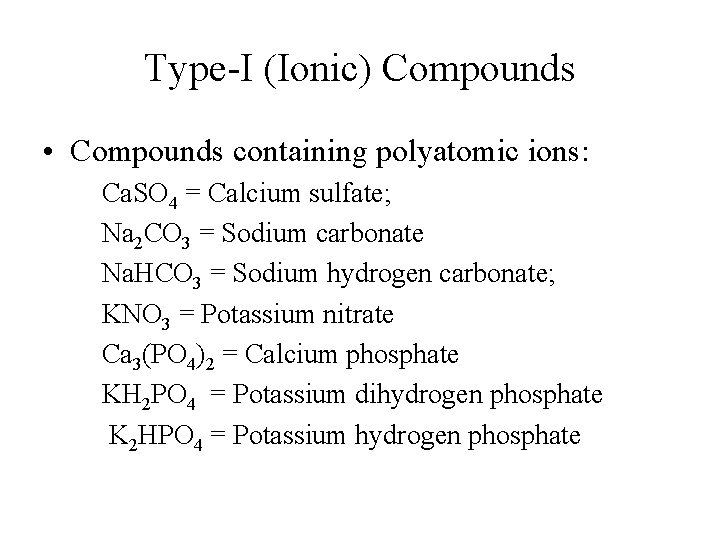

Type-I (Ionic) Compounds • Compounds containing polyatomic ions: Ca. SO 4 = Calcium sulfate; Na 2 CO 3 = Sodium carbonate Na. HCO 3 = Sodium hydrogen carbonate; KNO 3 = Potassium nitrate Ca 3(PO 4)2 = Calcium phosphate KH 2 PO 4 = Potassium dihydrogen phosphate K 2 HPO 4 = Potassium hydrogen phosphate

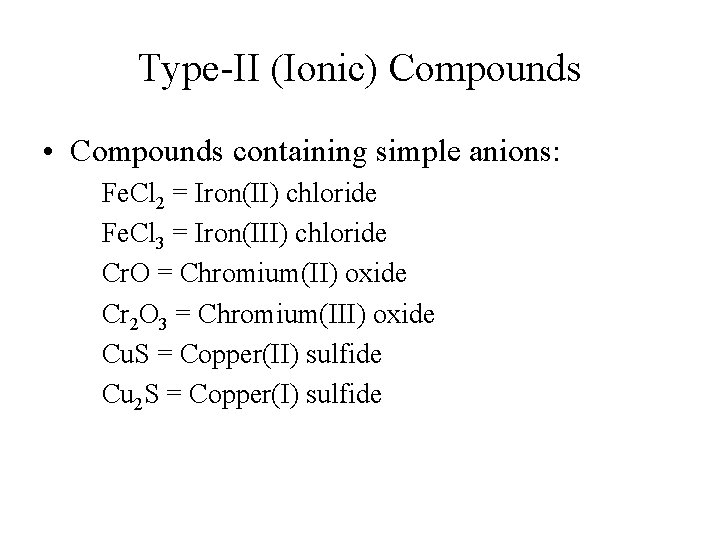

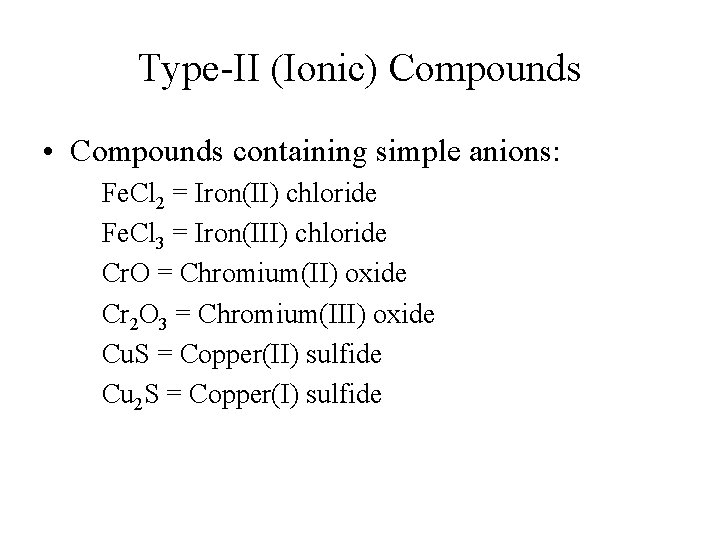

Type-II (Ionic) Compounds • Compounds containing simple anions: Fe. Cl 2 = Iron(II) chloride Fe. Cl 3 = Iron(III) chloride Cr. O = Chromium(II) oxide Cr 2 O 3 = Chromium(III) oxide Cu. S = Copper(II) sulfide Cu 2 S = Copper(I) sulfide

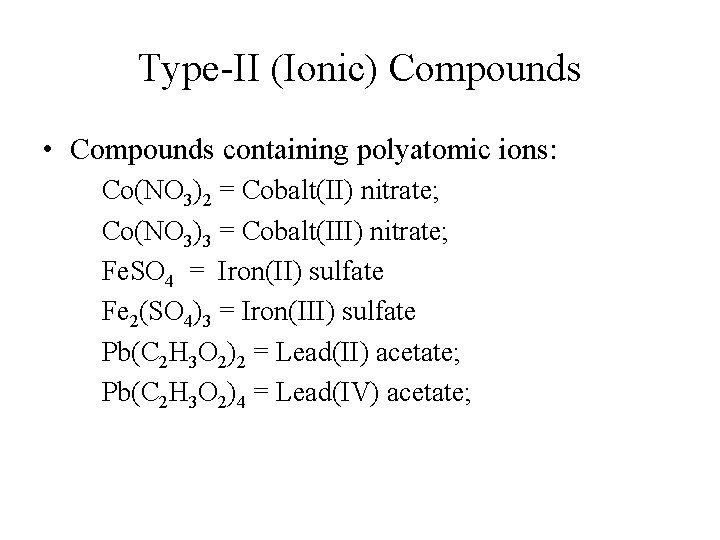

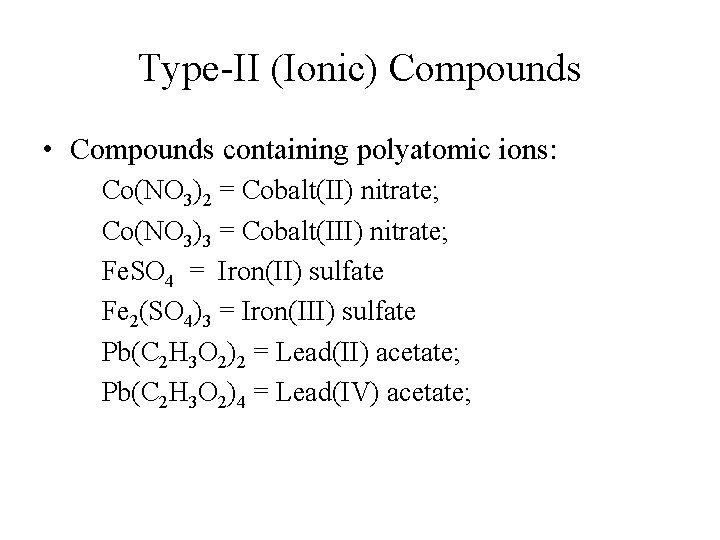

Type-II (Ionic) Compounds • Compounds containing polyatomic ions: Co(NO 3)2 = Cobalt(II) nitrate; Co(NO 3)3 = Cobalt(III) nitrate; Fe. SO 4 = Iron(II) sulfate Fe 2(SO 4)3 = Iron(III) sulfate Pb(C 2 H 3 O 2)2 = Lead(II) acetate; Pb(C 2 H 3 O 2)4 = Lead(IV) acetate;

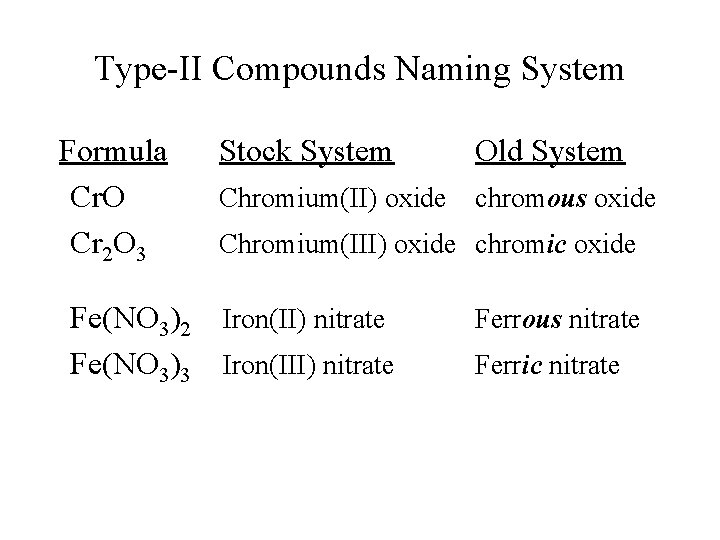

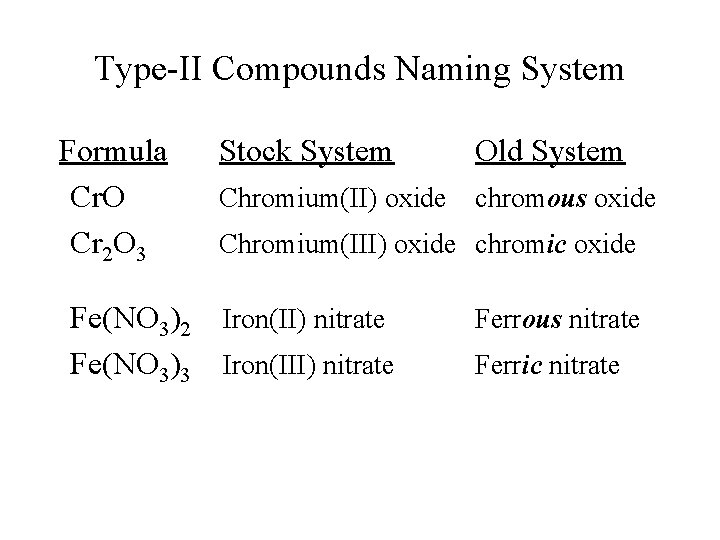

Type-II Compounds Naming System Formula Cr. O Cr 2 O 3 Stock System Old System Chromium(II) oxide chromous oxide Chromium(III) oxide chromic oxide Fe(NO 3)2 Iron(II) nitrate Fe(NO 3)3 Iron(III) nitrate Ferrous nitrate Ferric nitrate

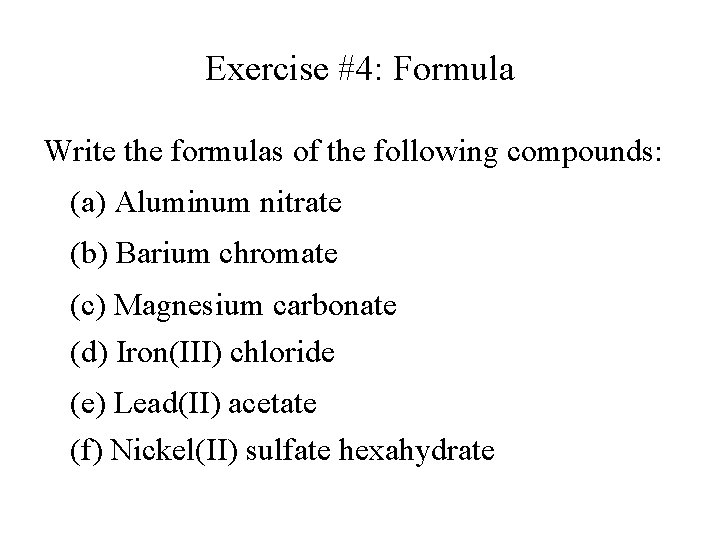

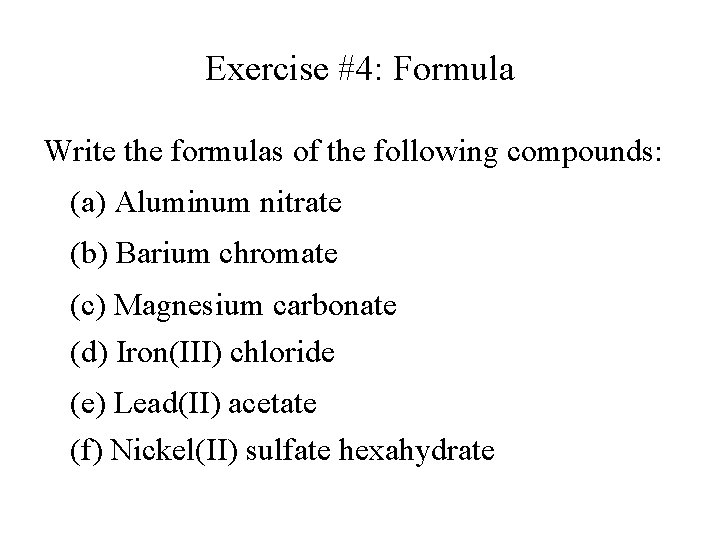

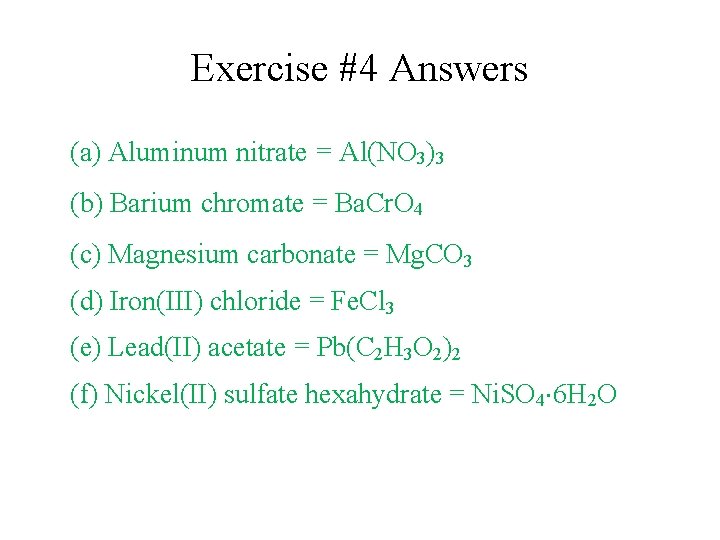

Exercise #4: Formula Write the formulas of the following compounds: (a) Aluminum nitrate (b) Barium chromate (c) Magnesium carbonate (d) Iron(III) chloride (e) Lead(II) acetate (f) Nickel(II) sulfate hexahydrate

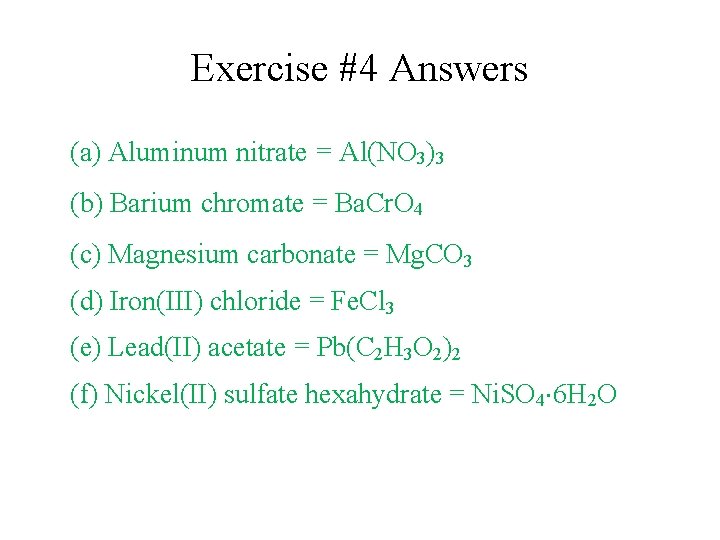

Exercise #4 Answers (a) Aluminum nitrate = Al(NO 3)3 (b) Barium chromate = Ba. Cr. O 4 (c) Magnesium carbonate = Mg. CO 3 (d) Iron(III) chloride = Fe. Cl 3 (e) Lead(II) acetate = Pb(C 2 H 3 O 2)2 (f) Nickel(II) sulfate hexahydrate = Ni. SO 4 6 H 2 O

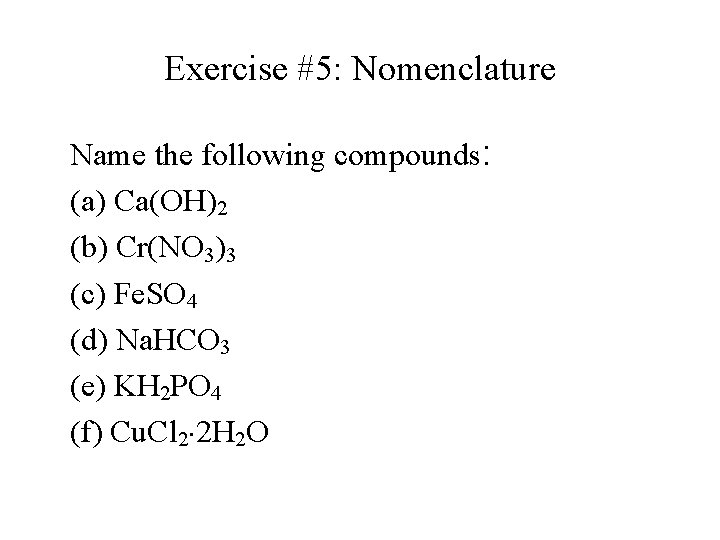

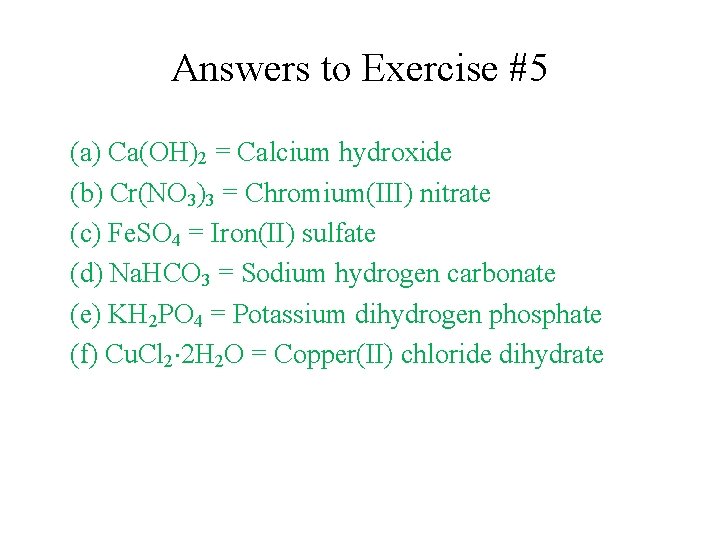

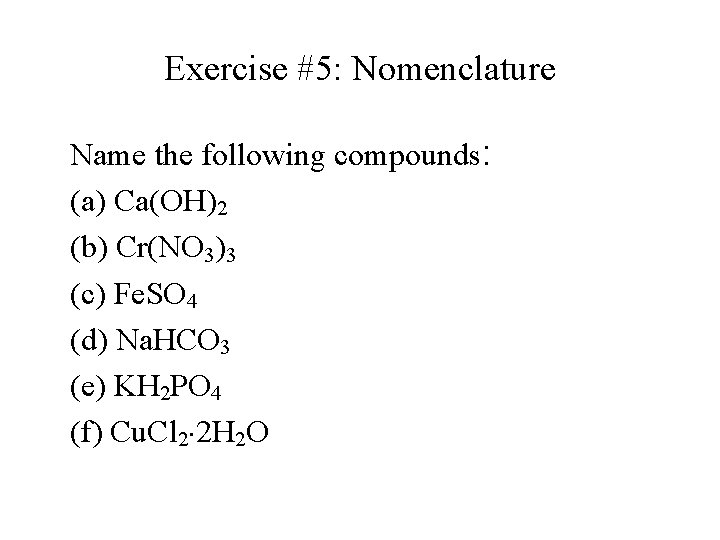

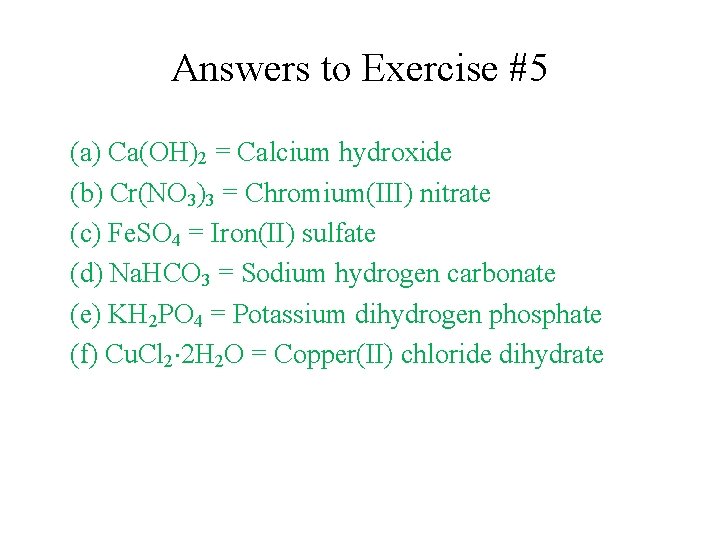

Exercise #5: Nomenclature Name the following compounds: (a) Ca(OH)2 (b) Cr(NO 3)3 (c) Fe. SO 4 (d) Na. HCO 3 (e) KH 2 PO 4 (f) Cu. Cl 2 2 H 2 O

Answers to Exercise #5 (a) Ca(OH)2 = Calcium hydroxide (b) Cr(NO 3)3 = Chromium(III) nitrate (c) Fe. SO 4 = Iron(II) sulfate (d) Na. HCO 3 = Sodium hydrogen carbonate (e) KH 2 PO 4 = Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (f) Cu. Cl 2 2 H 2 O = Copper(II) chloride dihydrate

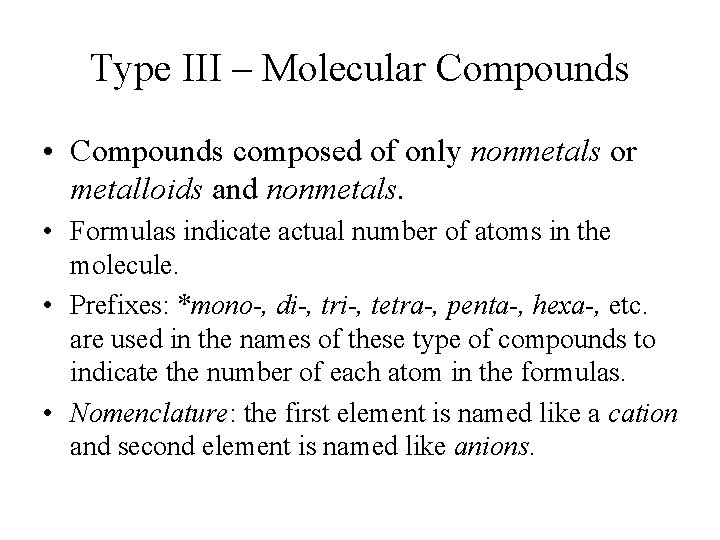

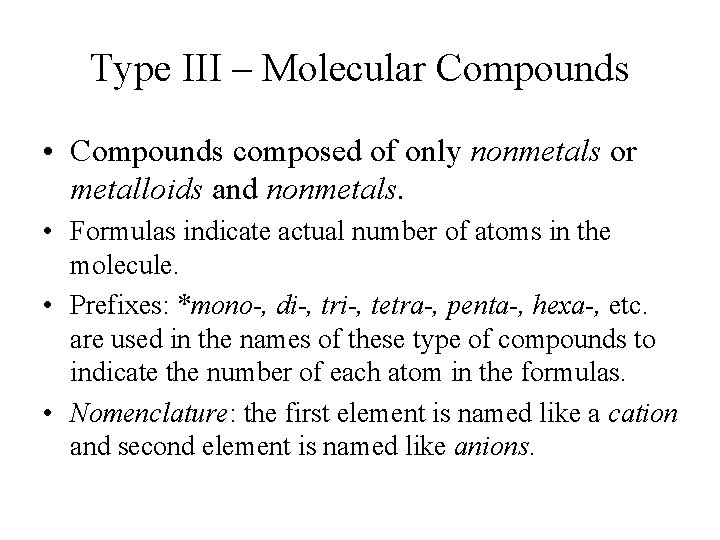

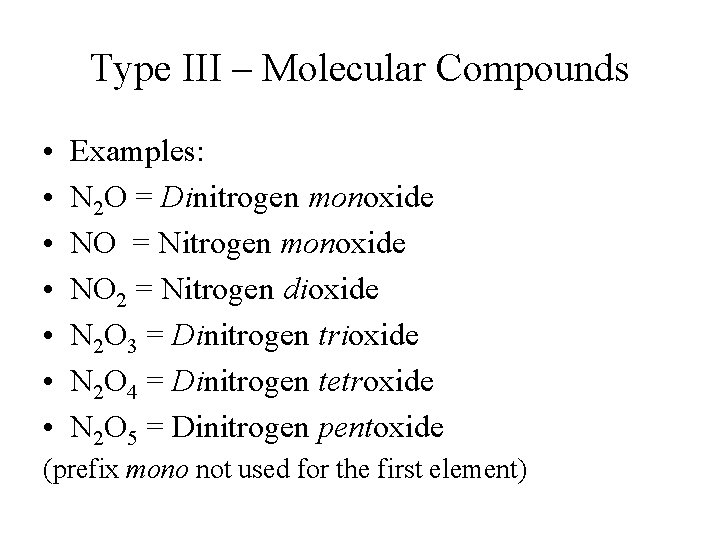

Type III – Molecular Compounds • Compounds composed of only nonmetals or metalloids and nonmetals. • Formulas indicate actual number of atoms in the molecule. • Prefixes: *mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, hexa-, etc. are used in the names of these type of compounds to indicate the number of each atom in the formulas. • Nomenclature: the first element is named like a cation and second element is named like anions.

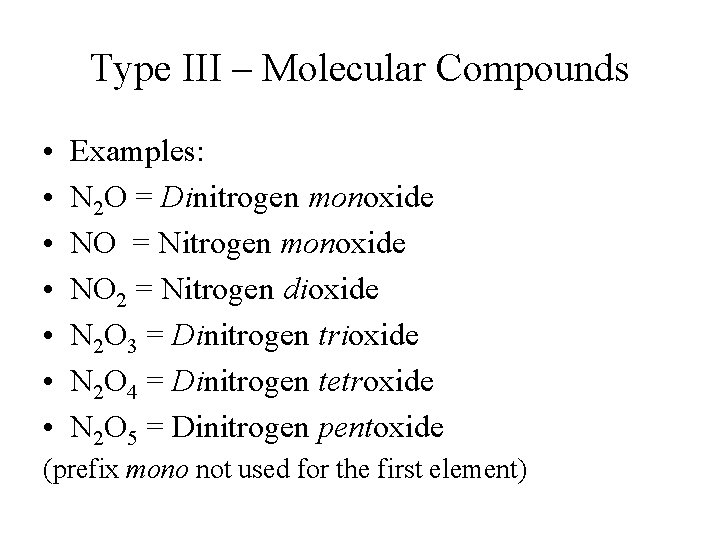

Type III – Molecular Compounds • • Examples: N 2 O = Dinitrogen monoxide NO = Nitrogen monoxide NO 2 = Nitrogen dioxide N 2 O 3 = Dinitrogen trioxide N 2 O 4 = Dinitrogen tetroxide N 2 O 5 = Dinitrogen pentoxide (prefix mono not used for the first element)

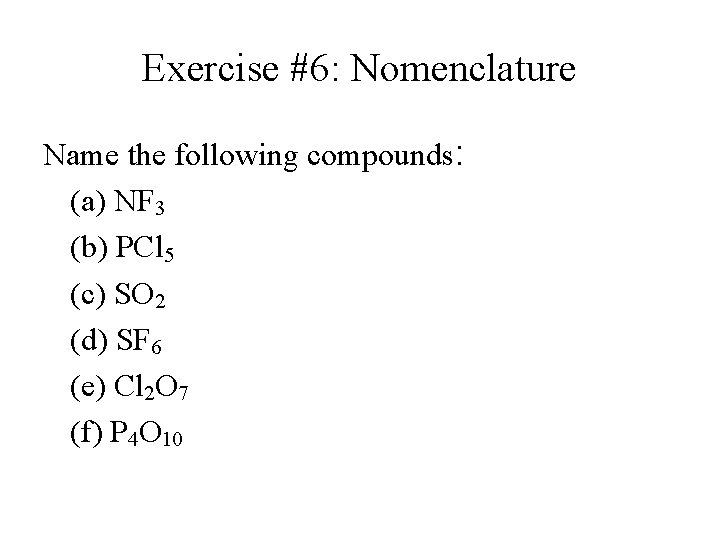

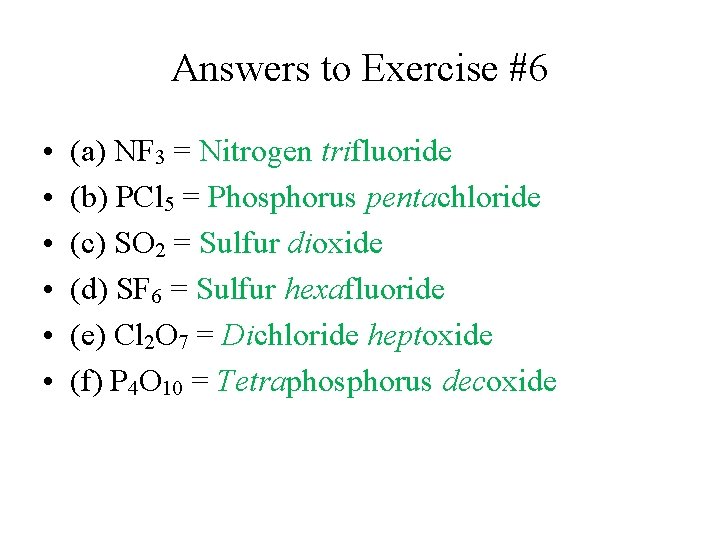

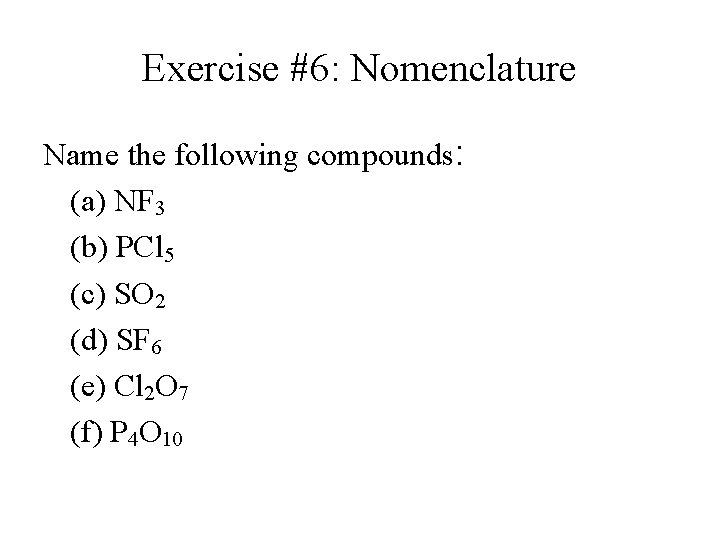

Exercise #6: Nomenclature Name the following compounds: (a) NF 3 (b) PCl 5 (c) SO 2 (d) SF 6 (e) Cl 2 O 7 (f) P 4 O 10

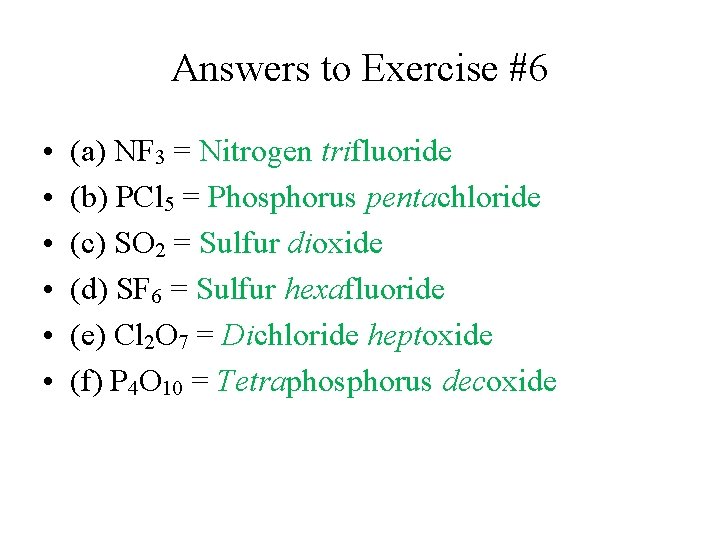

Answers to Exercise #6 • • • (a) NF 3 = Nitrogen trifluoride (b) PCl 5 = Phosphorus pentachloride (c) SO 2 = Sulfur dioxide (d) SF 6 = Sulfur hexafluoride (e) Cl 2 O 7 = Dichloride heptoxide (f) P 4 O 10 = Tetraphosphorus decoxide

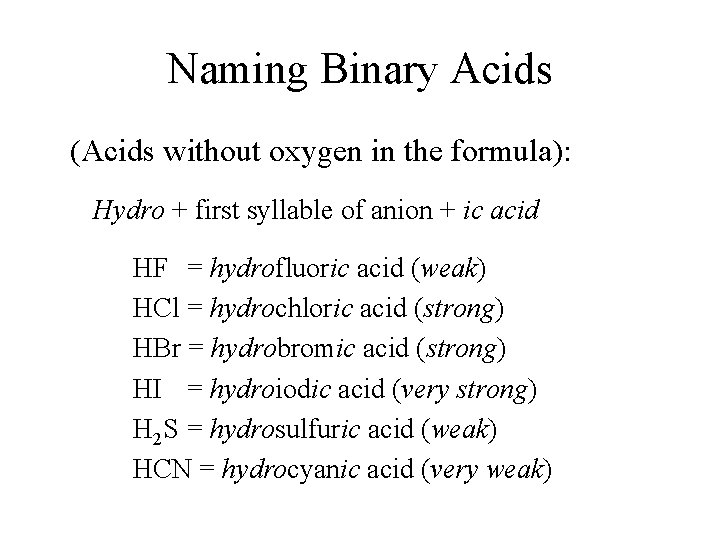

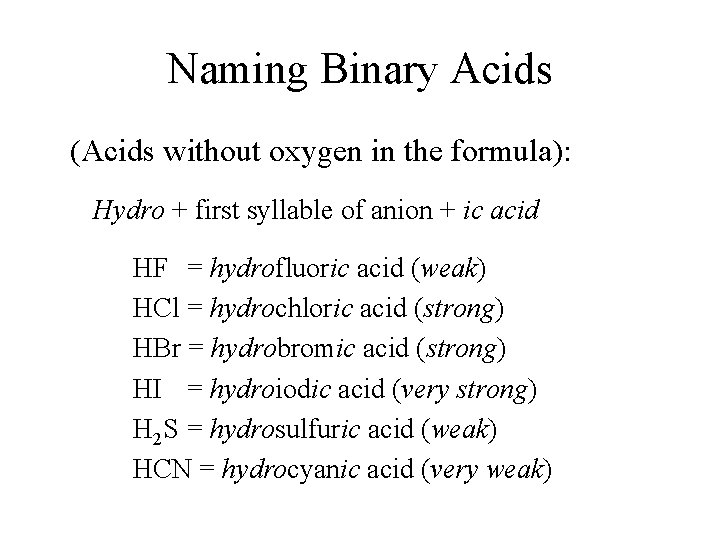

Naming Binary Acids (Acids without oxygen in the formula): Hydro + first syllable of anion + ic acid HF = hydrofluoric acid (weak) HCl = hydrochloric acid (strong) HBr = hydrobromic acid (strong) HI = hydroiodic acid (very strong) H 2 S = hydrosulfuric acid (weak) HCN = hydrocyanic acid (very weak)

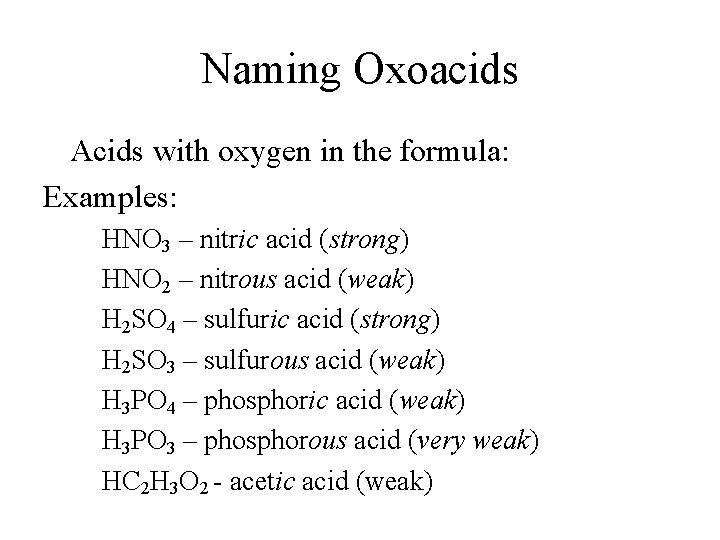

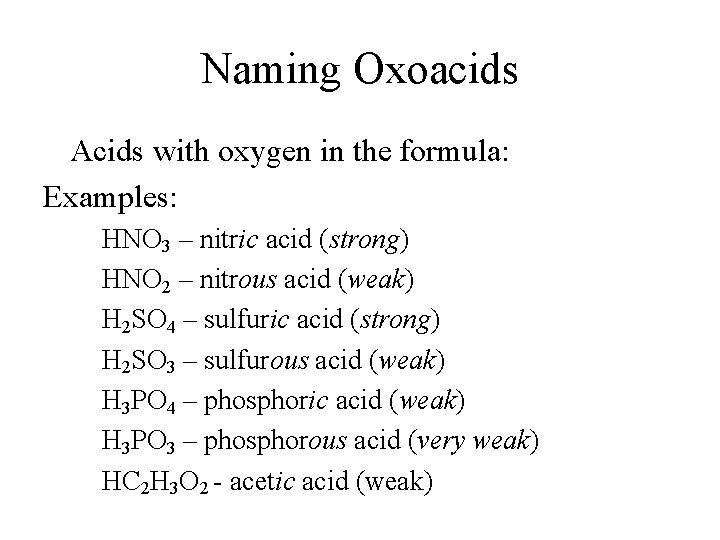

Naming Oxoacids Acids with oxygen in the formula: Examples: HNO 3 – nitric acid (strong) HNO 2 – nitrous acid (weak) H 2 SO 4 – sulfuric acid (strong) H 2 SO 3 – sulfurous acid (weak) H 3 PO 4 – phosphoric acid (weak) H 3 PO 3 – phosphorous acid (very weak) HC 2 H 3 O 2 - acetic acid (weak)

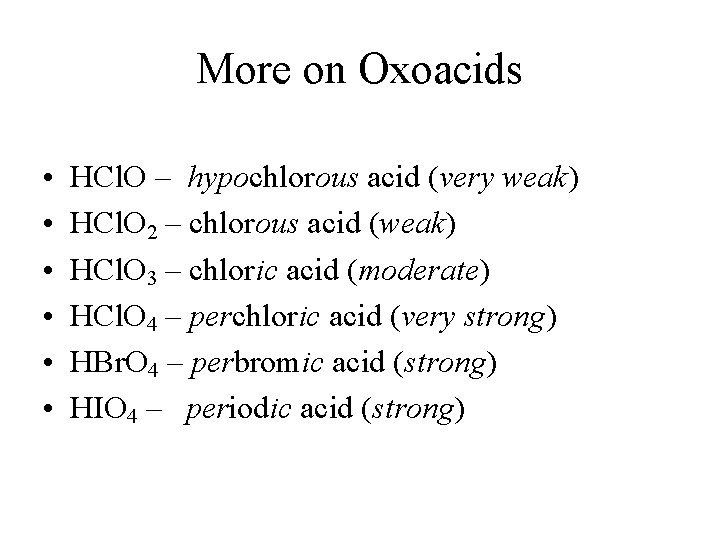

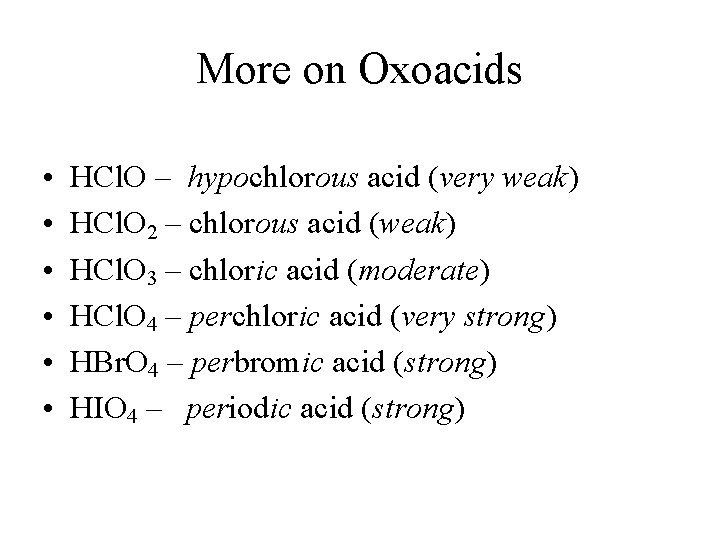

More on Oxoacids • • • HCl. O – hypochlorous acid (very weak) HCl. O 2 – chlorous acid (weak) HCl. O 3 – chloric acid (moderate) HCl. O 4 – perchloric acid (very strong) HBr. O 4 – perbromic acid (strong) HIO 4 – periodic acid (strong)

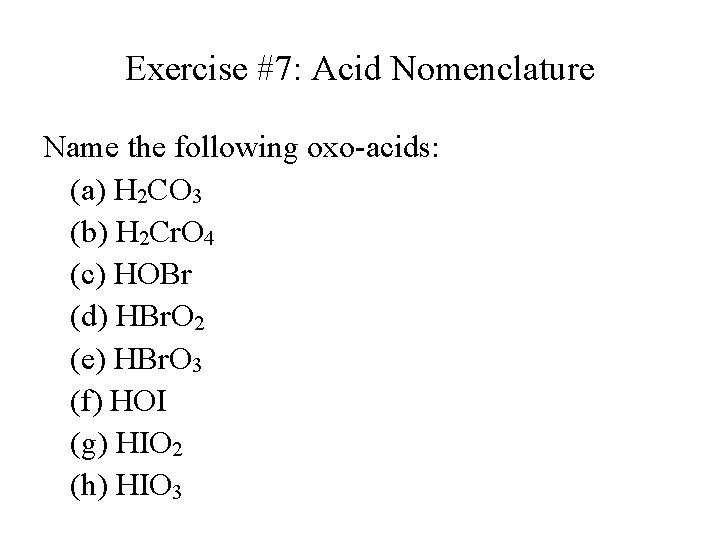

Exercise #7: Acid Nomenclature Name the following oxo-acids: (a) H 2 CO 3 (b) H 2 Cr. O 4 (c) HOBr (d) HBr. O 2 (e) HBr. O 3 (f) HOI (g) HIO 2 (h) HIO 3

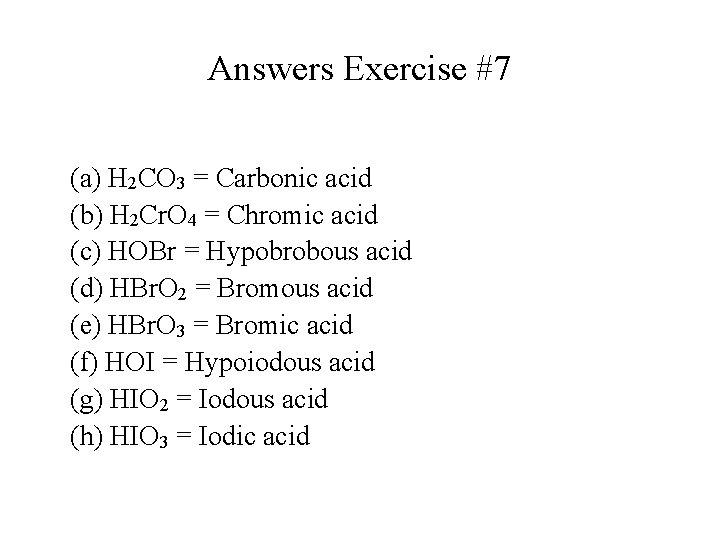

Answers Exercise #7 (a) H 2 CO 3 = Carbonic acid (b) H 2 Cr. O 4 = Chromic acid (c) HOBr = Hypobrobous acid (d) HBr. O 2 = Bromous acid (e) HBr. O 3 = Bromic acid (f) HOI = Hypoiodous acid (g) HIO 2 = Iodous acid (h) HIO 3 = Iodic acid