Atomic Force Microscopy AFM Operating principle Cantilever response

- Slides: 74

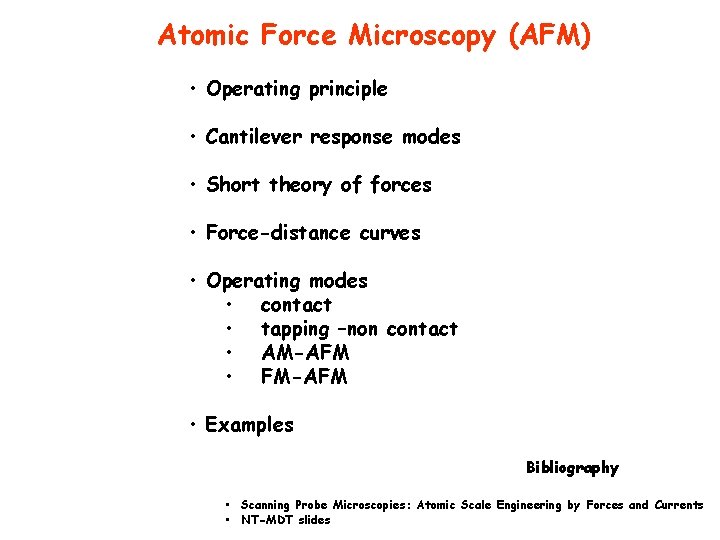

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) • Operating principle • Cantilever response modes • Short theory of forces • Force-distance curves • Operating modes • contact • tapping –non contact • AM-AFM • FM-AFM • Examples Bibliography • Scanning Probe Microscopies: Atomic Scale Engineering by Forces and Currents • NT-MDT slides

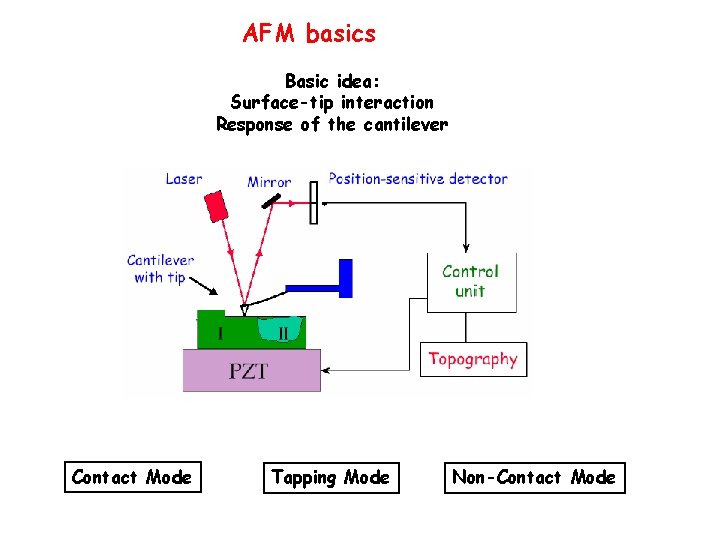

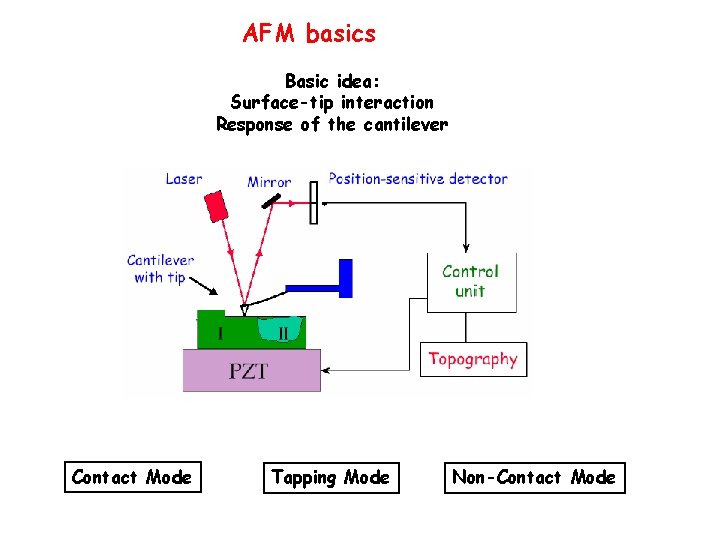

AFM basics Basic idea: Surface-tip interaction Response of the cantilever Contact Mode Tapping Mode Non-Contact Mode

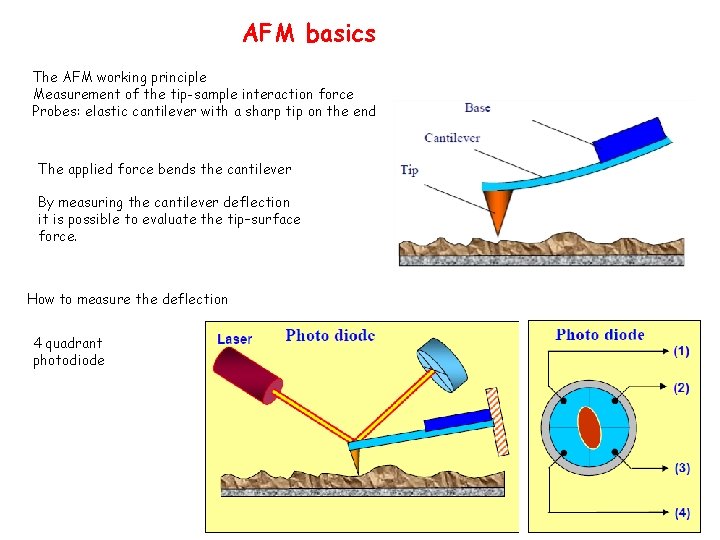

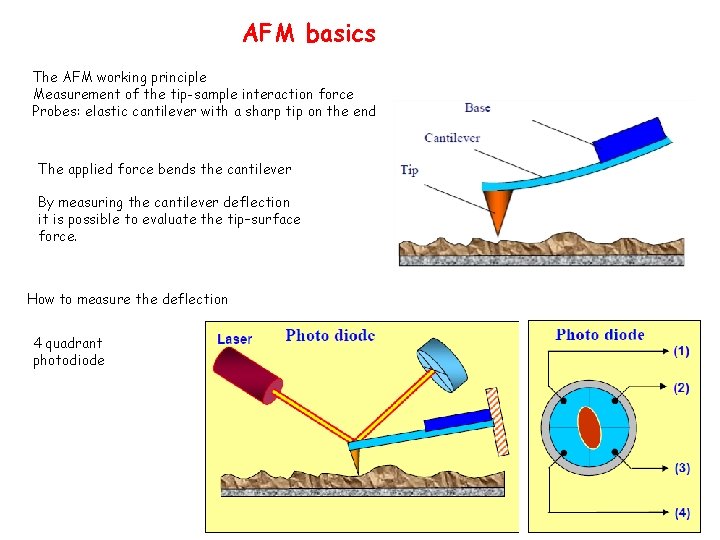

AFM basics The AFM working principle Measurement of the tip-sample interaction force Probes: elastic cantilever with a sharp tip on the end The applied force bends the cantilever By measuring the cantilever deflection it is possible to evaluate the tip–surface force. How to measure the deflection 4 quadrant photodiode

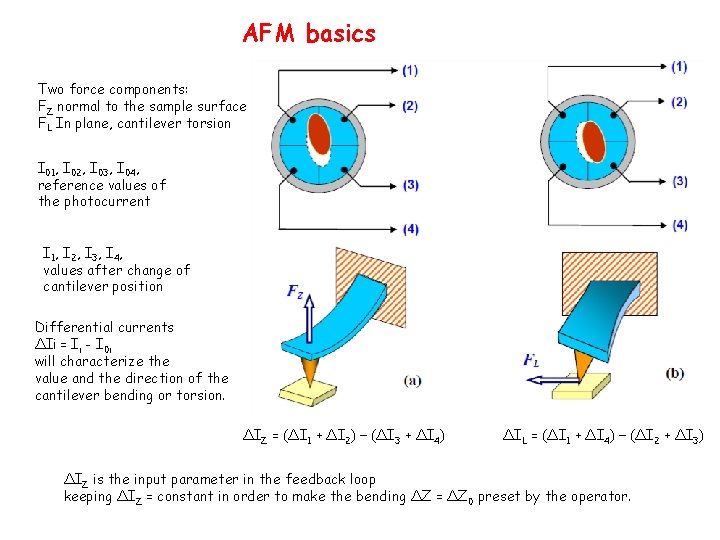

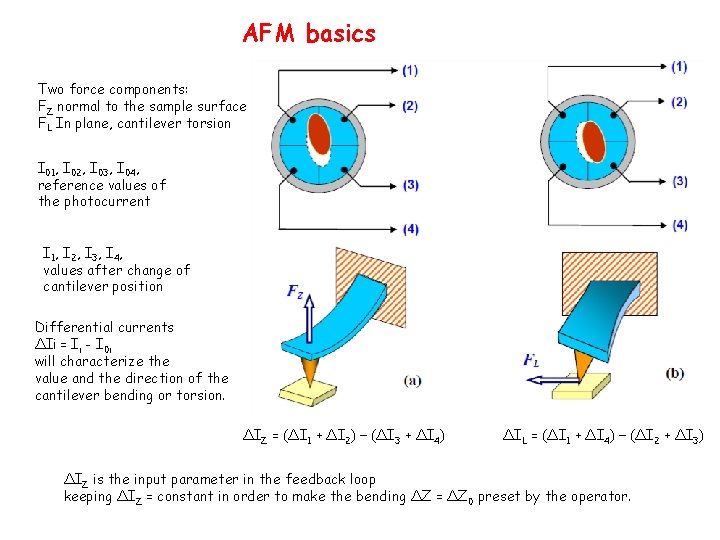

AFM basics Two force components: FZ normal to the sample surface FL In plane, cantilever torsion I 01, I 02, I 03, I 04, reference values of the photocurrent I 1, I 2, I 3, I 4, values after change of cantilever position Differential currents ΔIi = Ii - I 0 i will characterize the value and the direction of the cantilever bending or torsion. ΔIZ = (ΔI 1 + ΔI 2) − (ΔI 3 + ΔI 4) ΔIL = (ΔI 1 + ΔI 4) − (ΔI 2 + ΔI 3) ΔIZ is the input parameter in the feedback loop keeping ΔIZ = constant in order to make the bending ΔZ = ΔZ 0 preset by the operator.

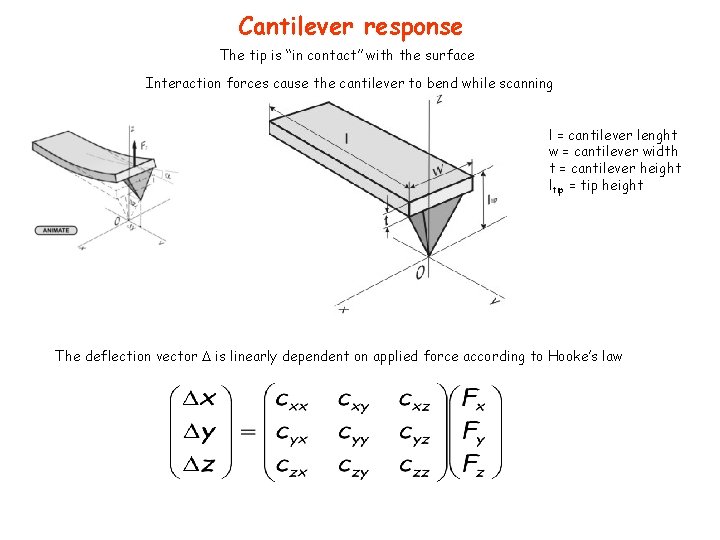

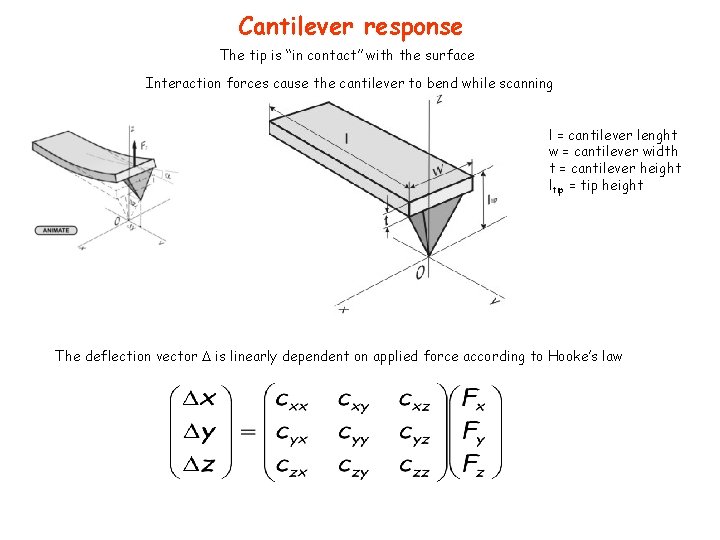

Cantilever response The tip is “in contact” with the surface Interaction forces cause the cantilever to bend while scanning l = cantilever lenght w = cantilever width t = cantilever height ltip = tip height The deflection vector is linearly dependent on applied force according to Hooke’s law

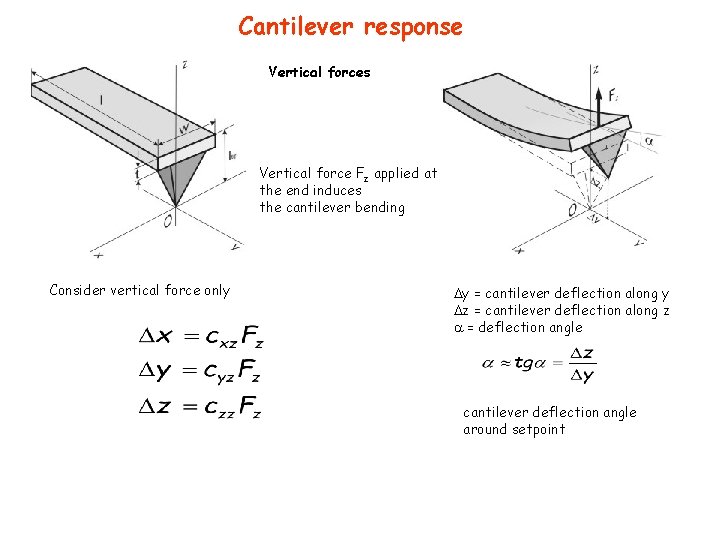

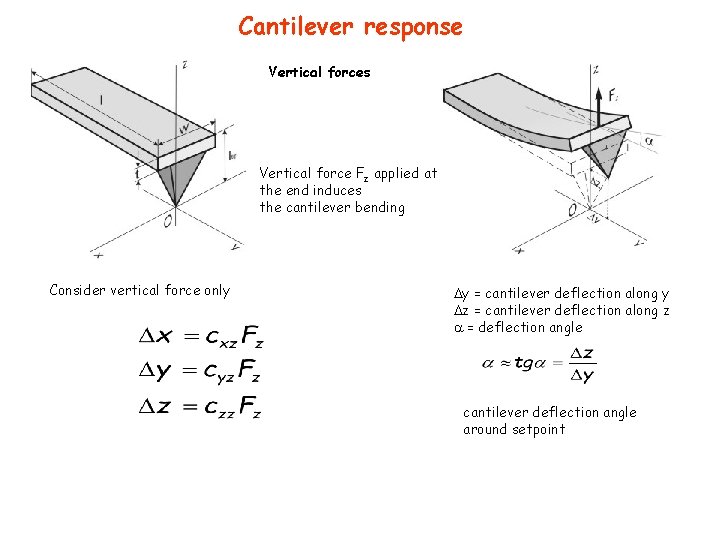

Cantilever response Vertical forces Vertical force Fz applied at the end induces the cantilever bending Consider vertical force only y = cantilever deflection along y z = cantilever deflection along z = deflection angle cantilever deflection angle around setpoint

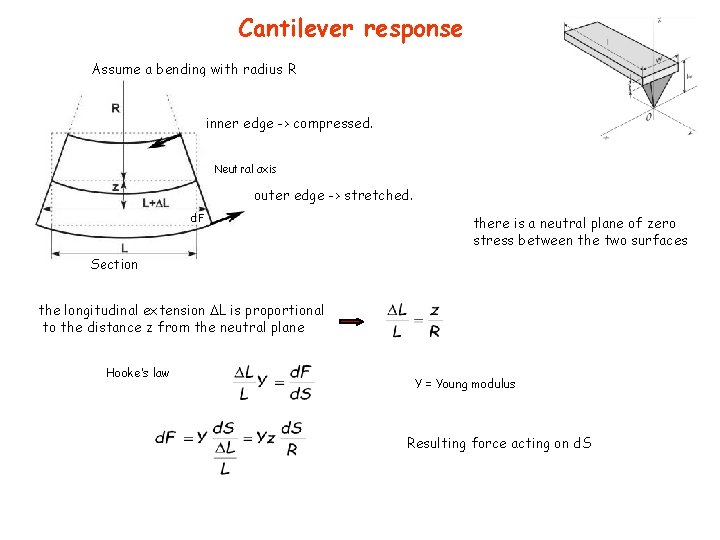

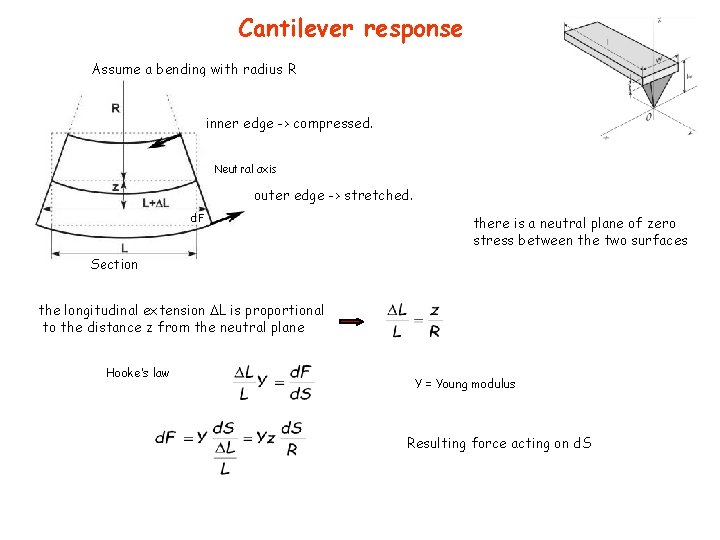

Cantilever response Assume a bending with radius R inner edge -> compressed. Neutral axis outer edge -> stretched. d. F there is a neutral plane of zero stress between the two surfaces Section the longitudinal extension L is proportional to the distance z from the neutral plane Hooke’s law Y = Young modulus Resulting force acting on d. S

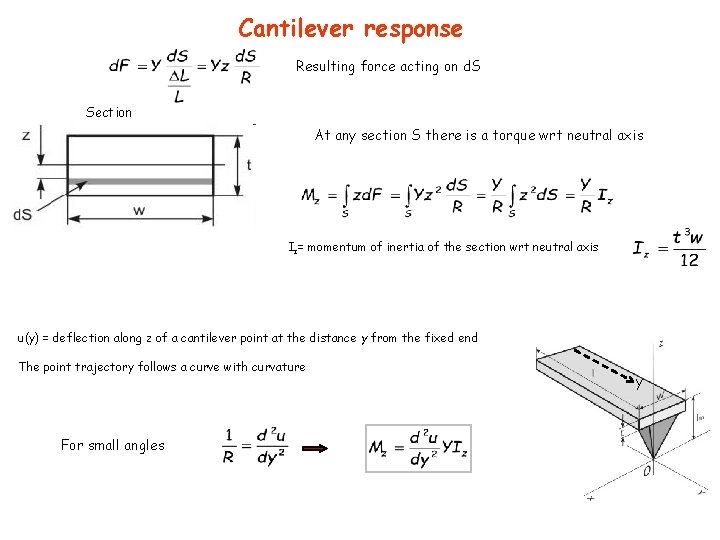

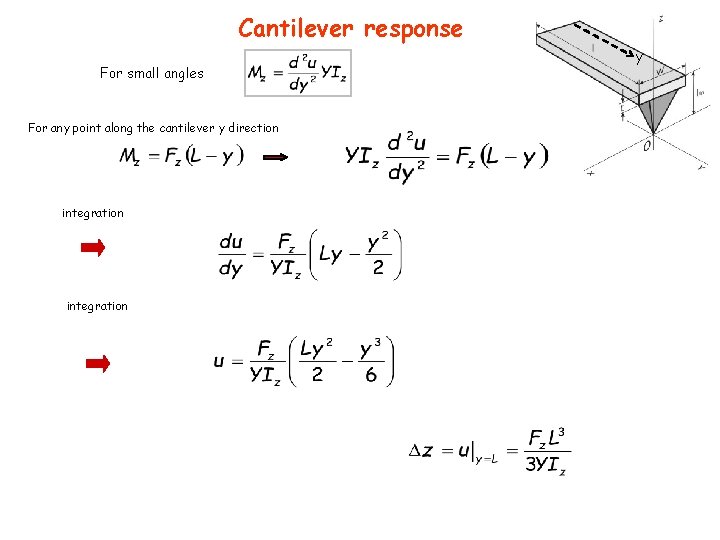

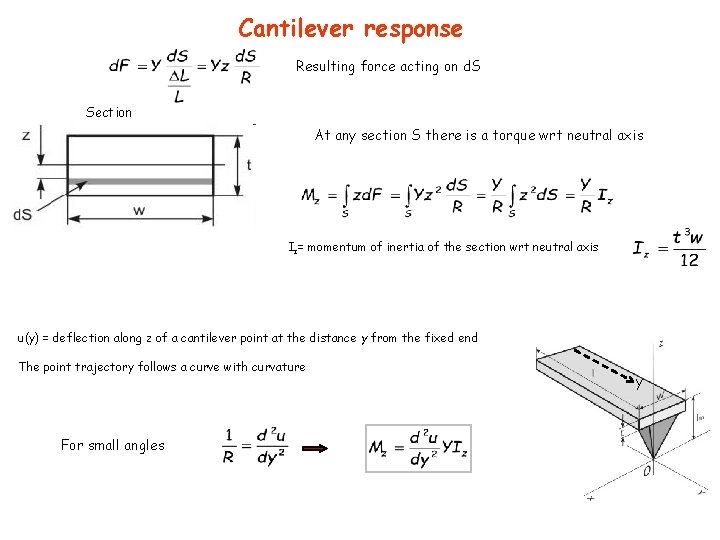

Cantilever response Resulting force acting on d. S Section At any section S there is a torque wrt neutral axis Iz= momentum of inertia of the section wrt neutral axis u(y) = deflection along z of a cantilever point at the distance y from the fixed end The point trajectory follows a curve with curvature For small angles y

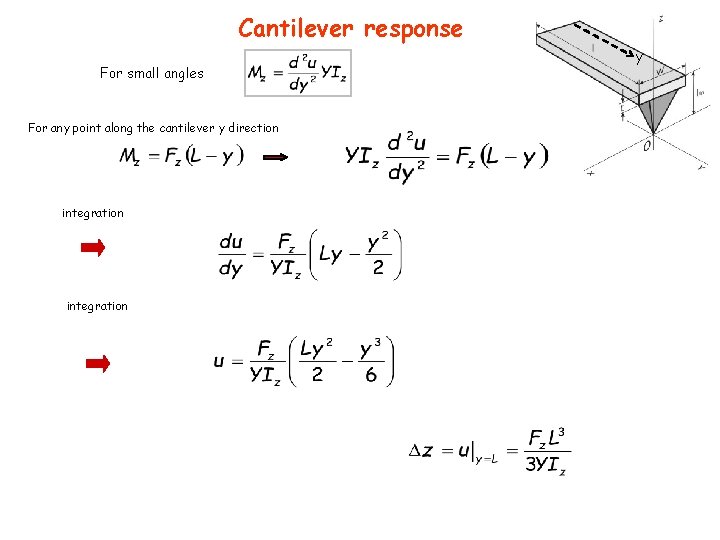

Cantilever response For small angles For any point along the cantilever y direction integration y

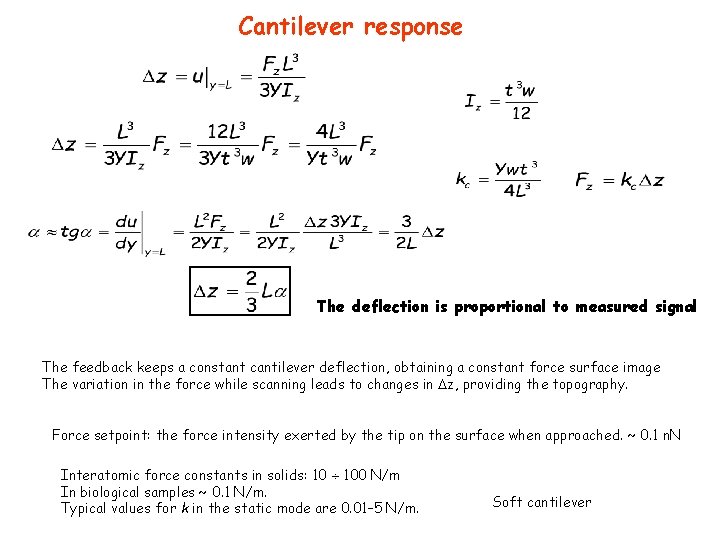

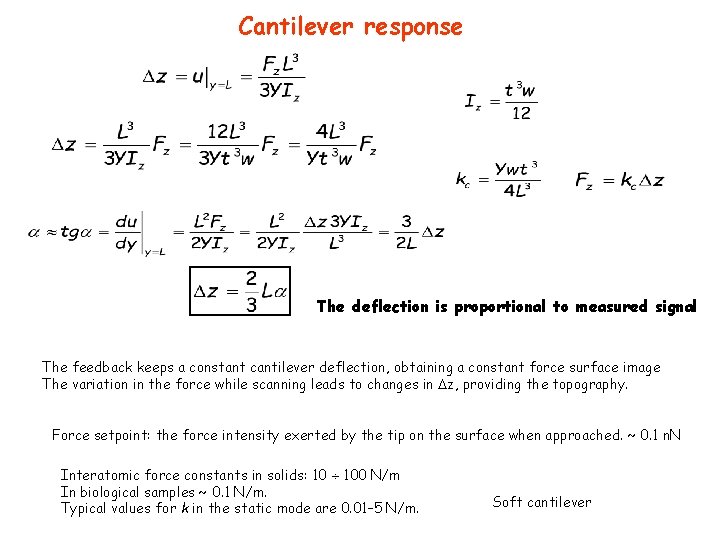

Cantilever response The deflection is proportional to measured signal The feedback keeps a constant cantilever deflection, obtaining a constant force surface image The variation in the force while scanning leads to changes in z, providing the topography. Force setpoint: the force intensity exerted by the tip on the surface when approached. ~ 0. 1 n. N Interatomic force constants in solids: 10 100 N/m In biological samples ~ 0. 1 N/m. Typical values for k in the static mode are 0. 01– 5 N/m. Soft cantilever

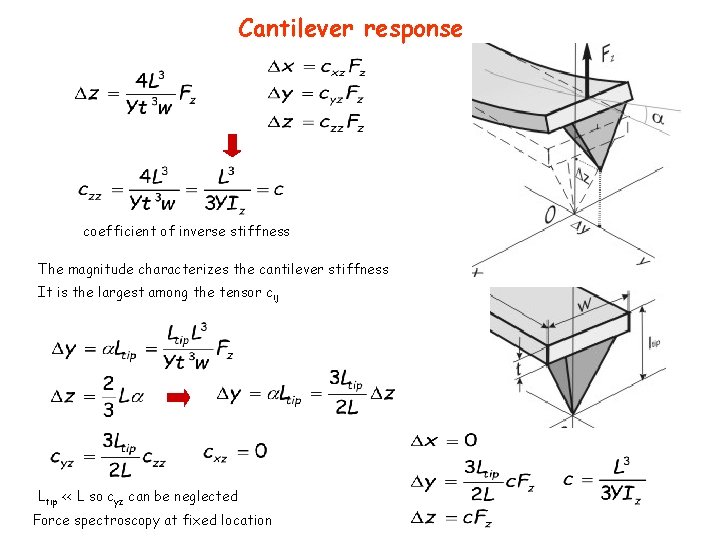

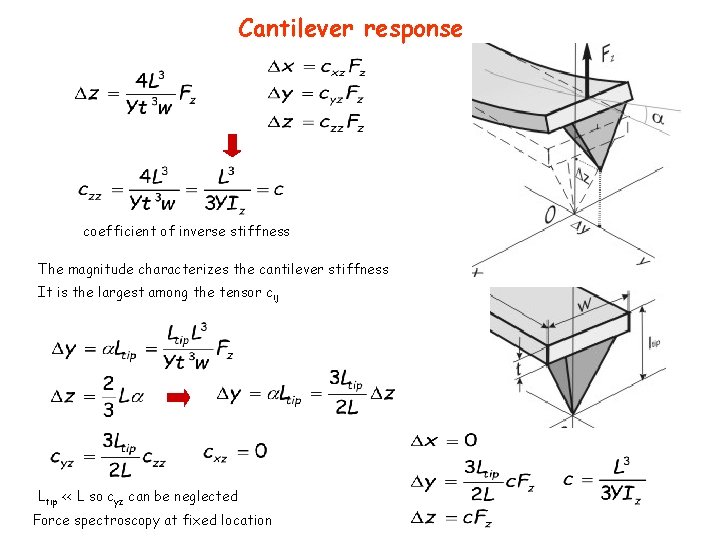

Cantilever response coefficient of inverse stiffness The magnitude characterizes the cantilever stiffness It is the largest among the tensor cij Ltip << L so cyz can be neglected Force spectroscopy at fixed location

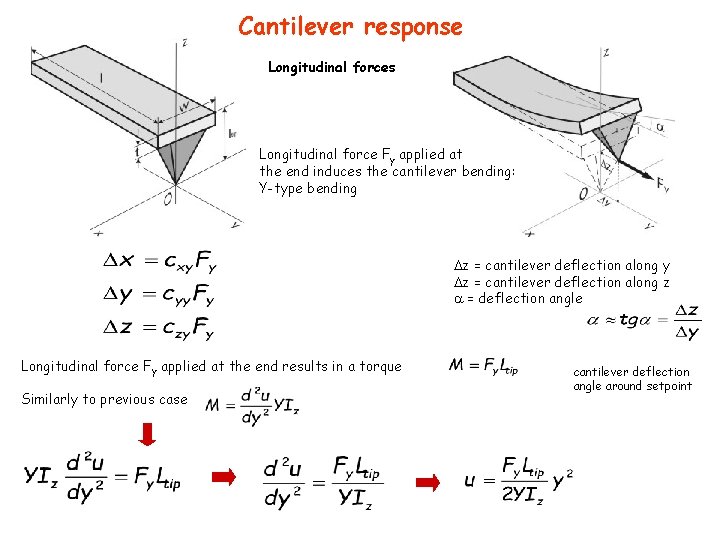

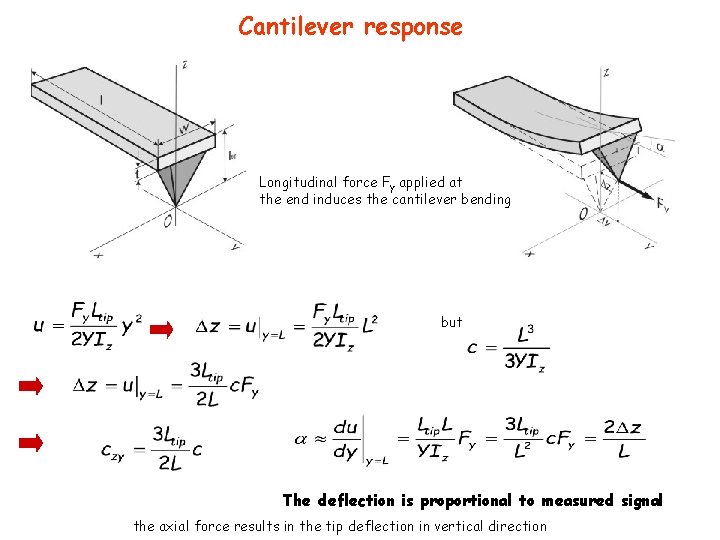

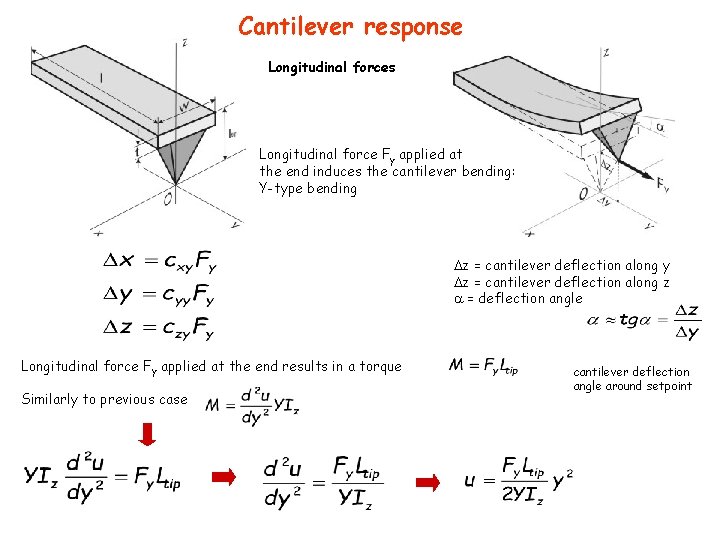

Cantilever response Longitudinal forces Longitudinal force Fy applied at the end induces the cantilever bending: Y-type bending z = cantilever deflection along y z = cantilever deflection along z = deflection angle Longitudinal force Fy applied at the end results in a torque Similarly to previous case cantilever deflection angle around setpoint

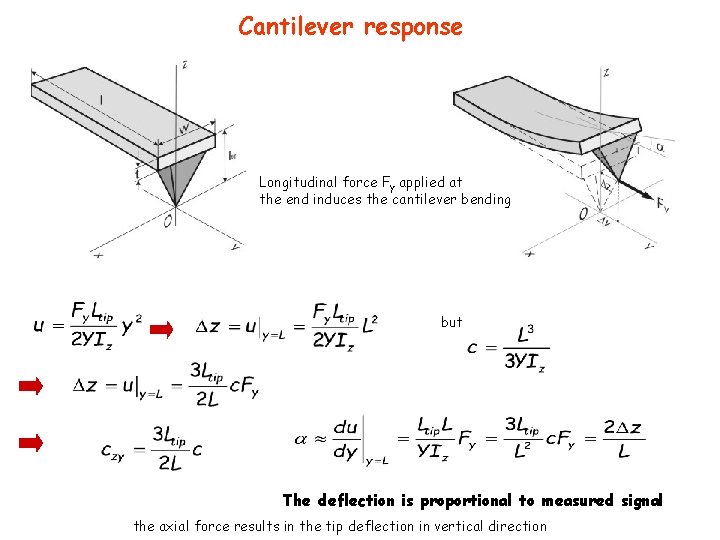

Cantilever response Longitudinal force Fy applied at the end induces the cantilever bending but The deflection is proportional to measured signal the axial force results in the tip deflection in vertical direction

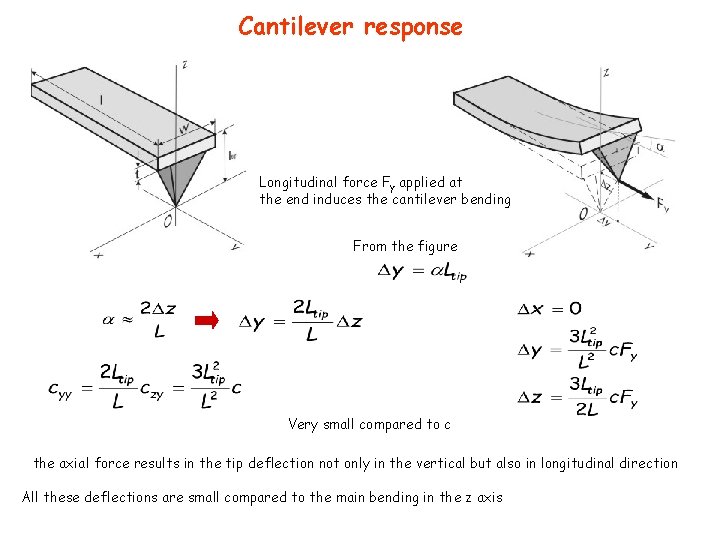

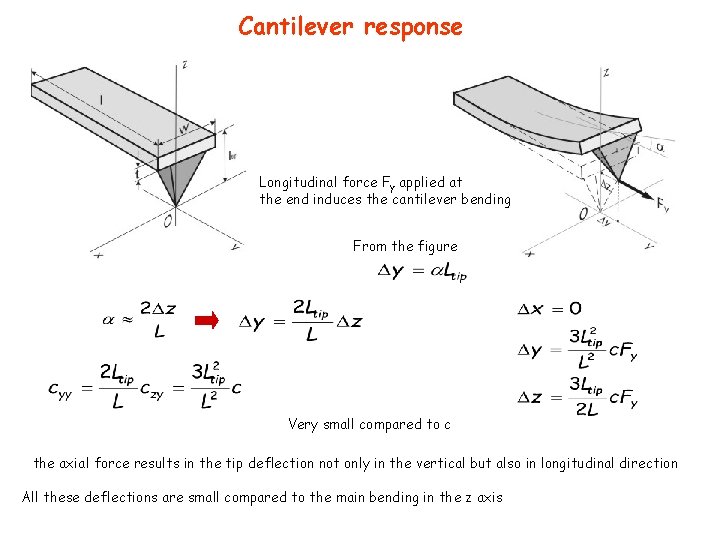

Cantilever response Longitudinal force Fy applied at the end induces the cantilever bending From the figure Very small compared to c the axial force results in the tip deflection not only in the vertical but also in longitudinal direction All these deflections are small compared to the main bending in the z axis

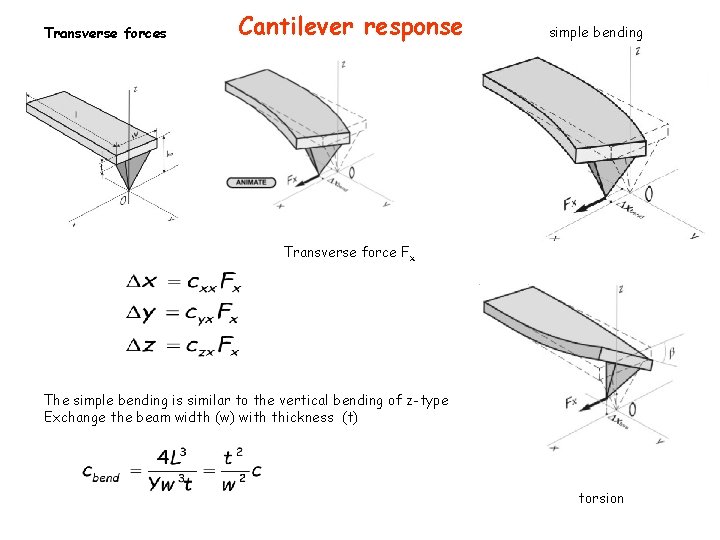

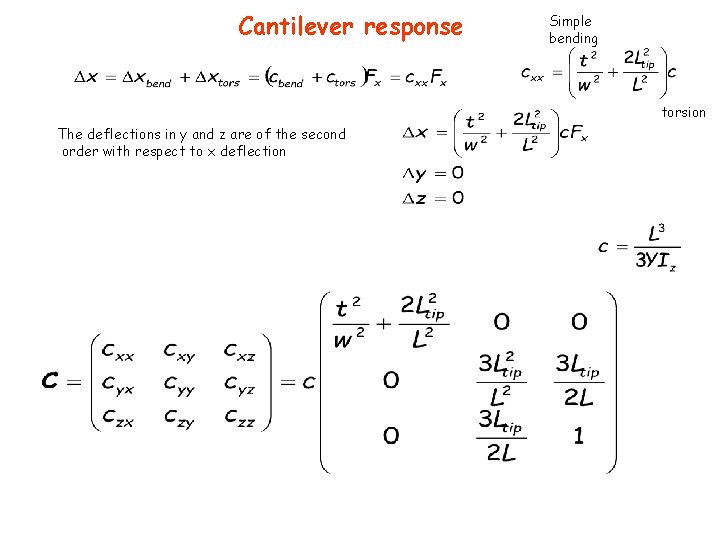

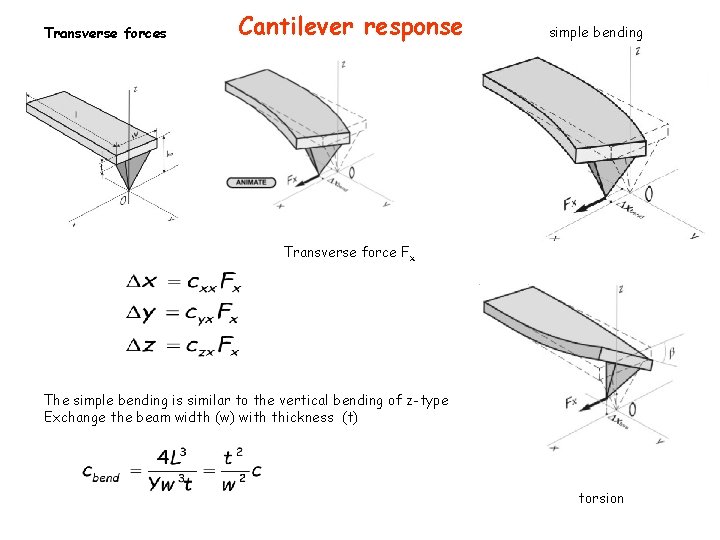

Transverse forces Cantilever response simple bending Transverse force Fx The simple bending is similar to the vertical bending of z-type Exchange the beam width (w) with thickness (t) torsion

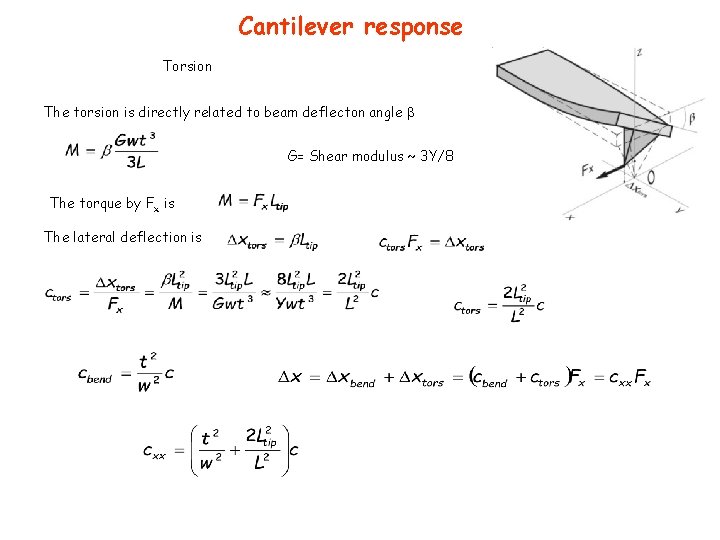

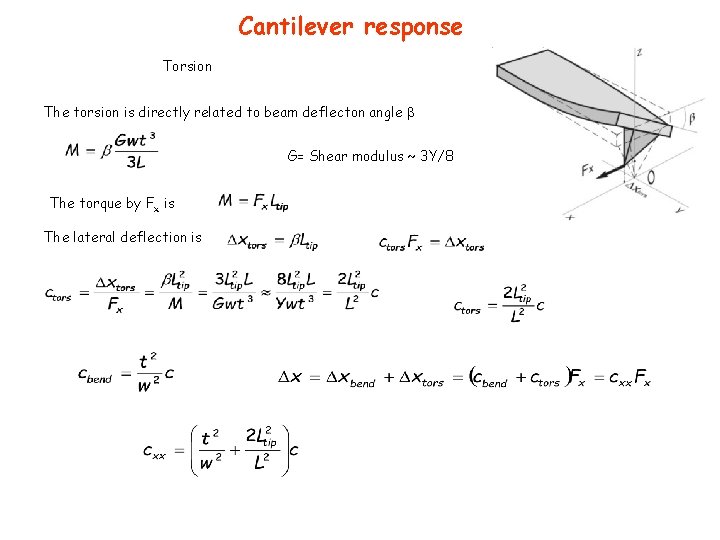

Cantilever response Torsion The torsion is directly related to beam deflecton angle G= Shear modulus ~ 3 Y/8 The torque by Fx is The lateral deflection is

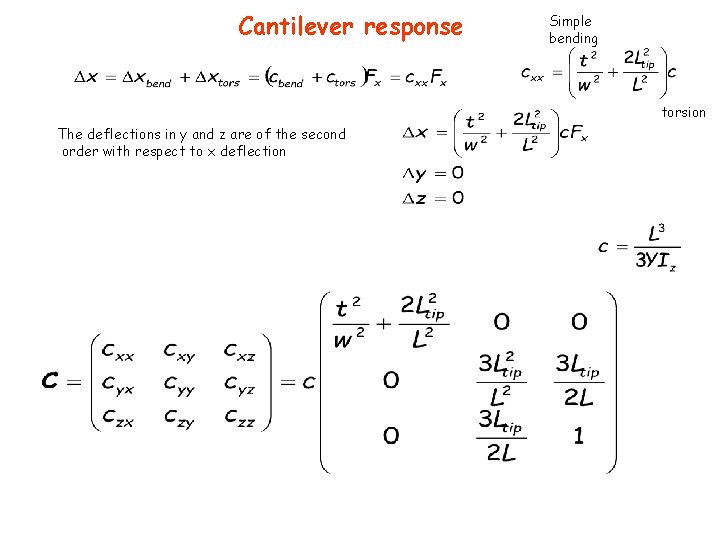

Cantilever response Simple bending torsion The deflections in y and z are of the second order with respect to x deflection

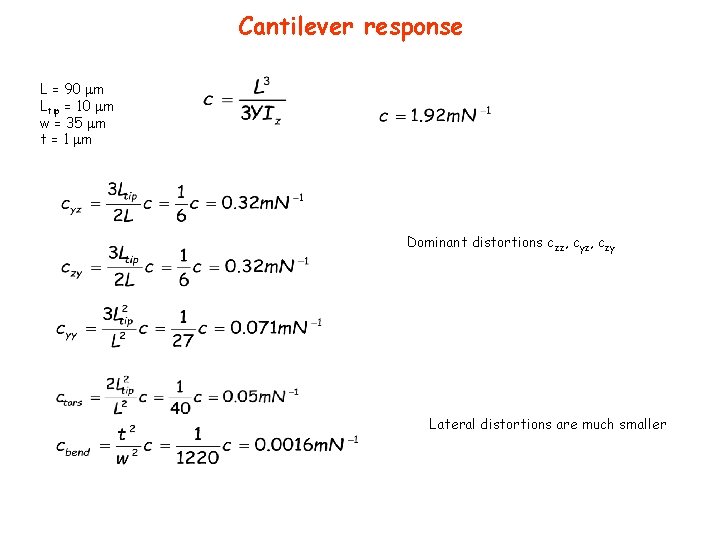

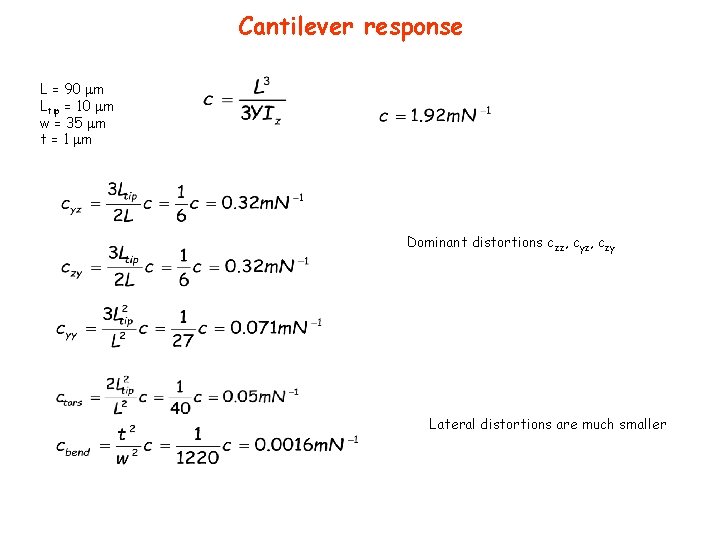

Cantilever response L = 90 m Ltip = 10 m w = 35 m t = 1 m Dominant distortions czz, cyz, czy Lateral distortions are much smaller

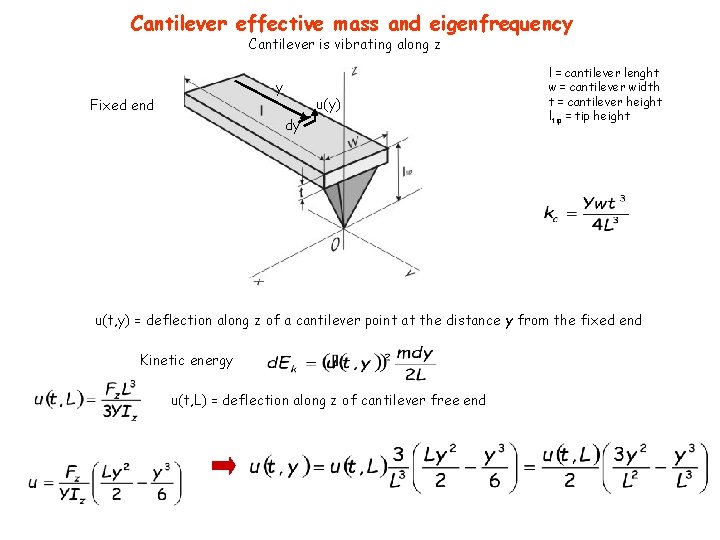

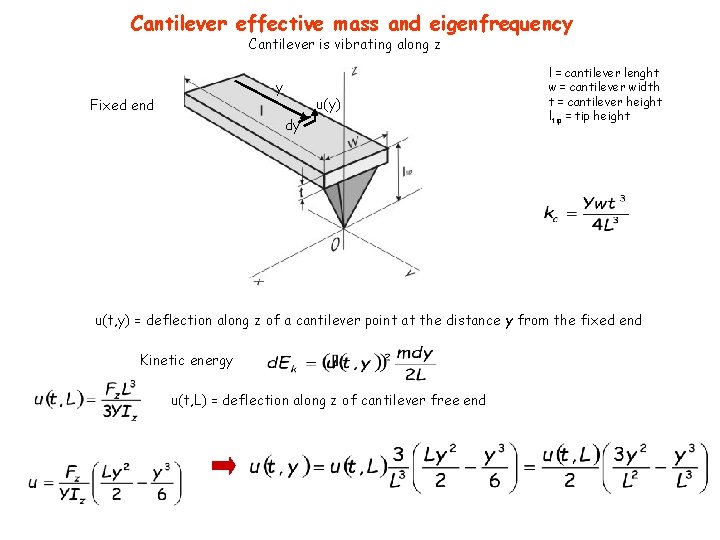

Cantilever effective mass and eigenfrequency Cantilever is vibrating along z y Fixed end u(y) dy l = cantilever lenght w = cantilever width t = cantilever height ltip = tip height u(t, y) = deflection along z of a cantilever point at the distance y from the fixed end Kinetic energy u(t, L) = deflection along z of cantilever free end

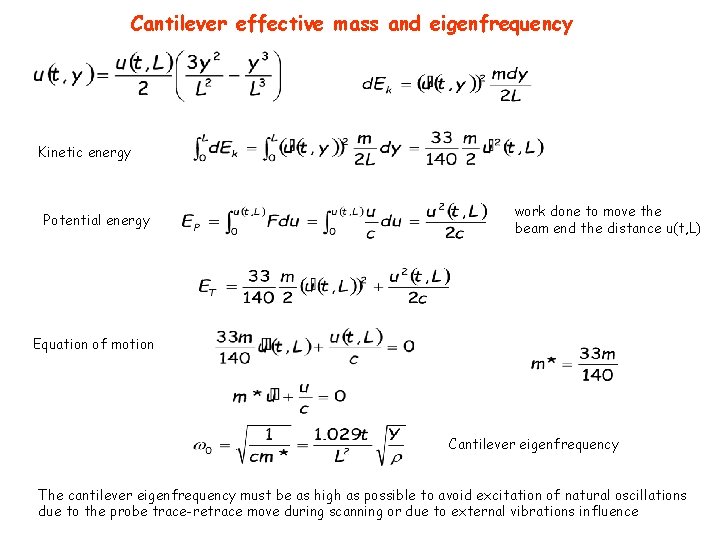

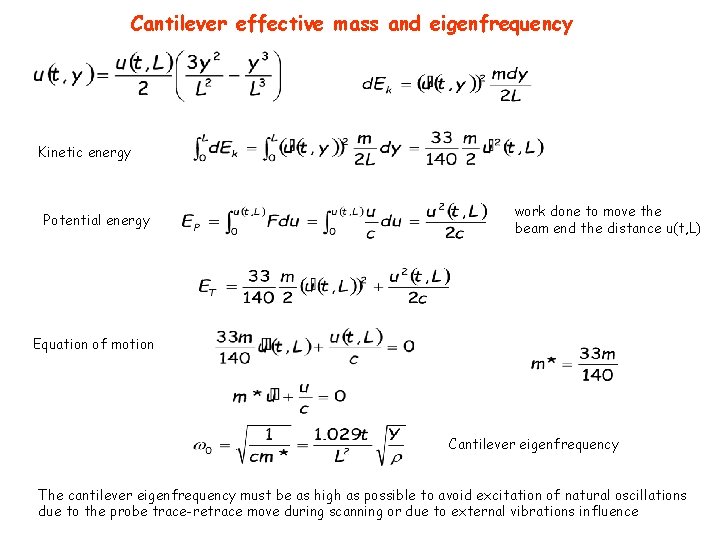

Cantilever effective mass and eigenfrequency Kinetic energy Potential energy work done to move the beam end the distance u(t, L) Equation of motion Cantilever eigenfrequency The cantilever eigenfrequency must be as high as possible to avoid excitation of natural oscillations due to the probe trace-retrace move during scanning or due to external vibrations influence

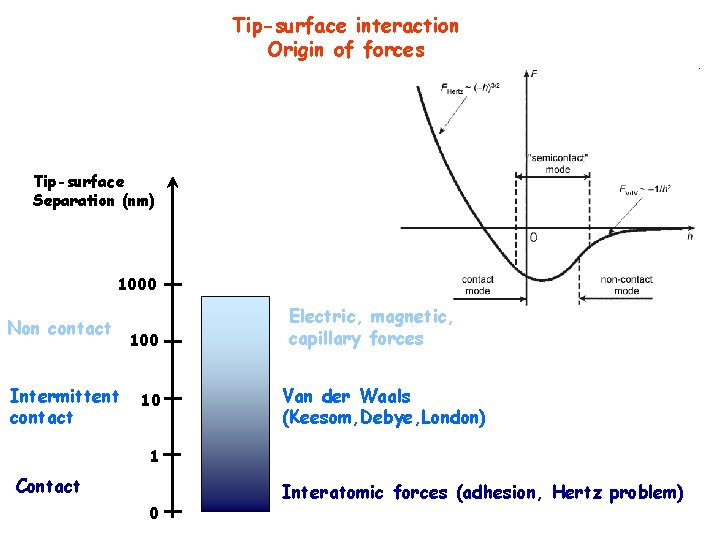

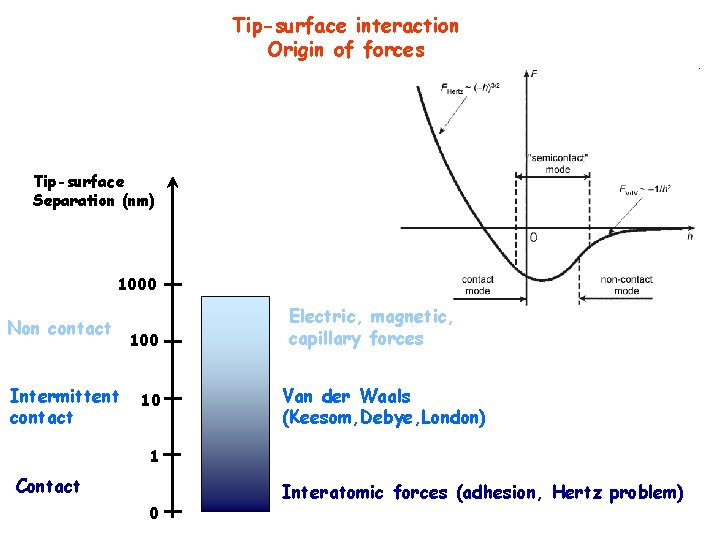

Tip-surface interaction Origin of forces Tip-surface Separation (nm) 1000 Non contact Intermittent contact 100 10 Electric, magnetic, capillary forces Van der Waals (Keesom, Debye, London) 1 Contact 0 Interatomic forces (adhesion, Hertz problem)

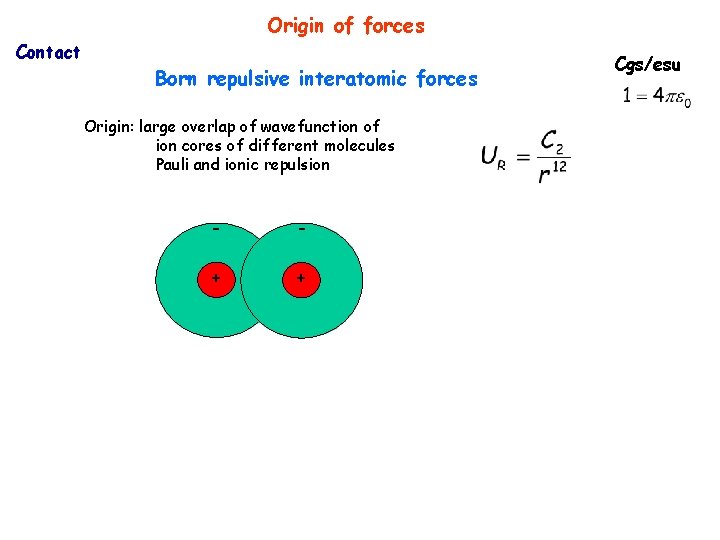

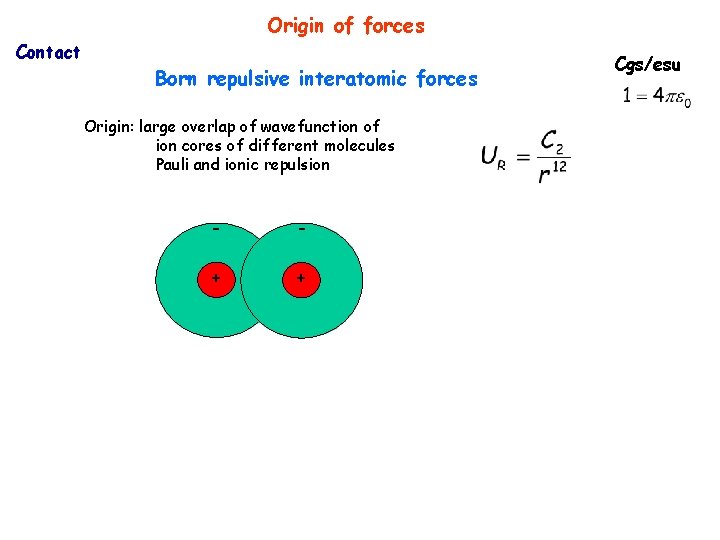

Origin of forces Contact Born repulsive interatomic forces Origin: large overlap of wavefunction of ion cores of different molecules Pauli and ionic repulsion - - + + Cgs/esu

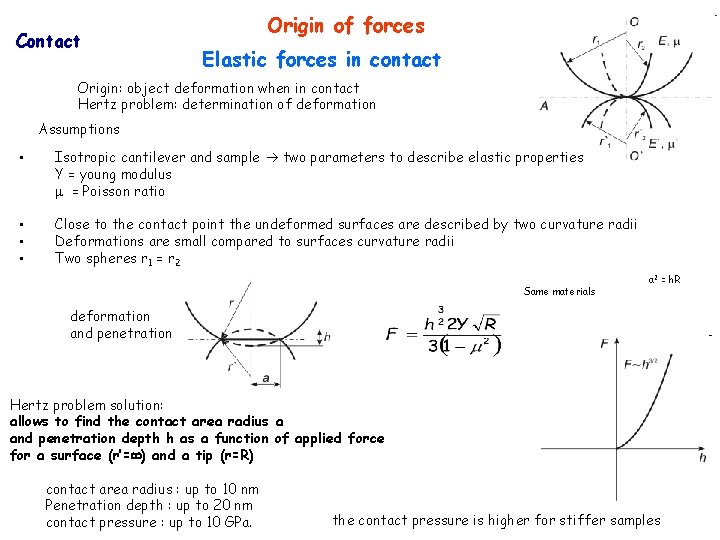

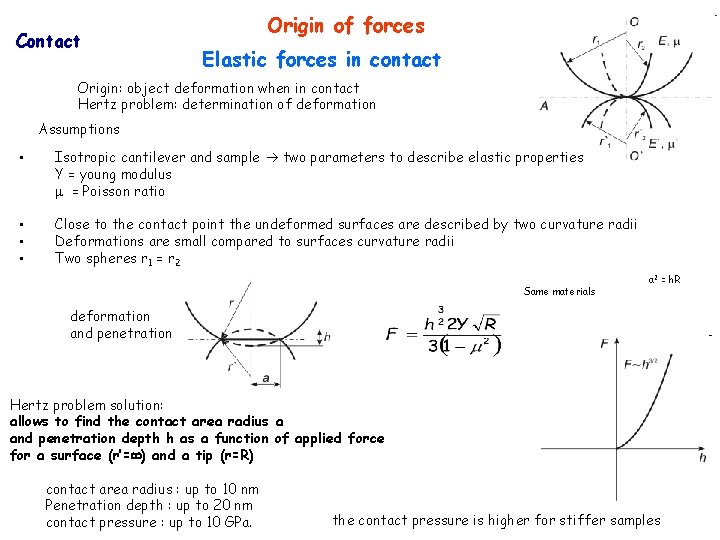

Contact Origin of forces Elastic forces in contact Origin: object deformation when in contact Hertz problem: determination of deformation Assumptions • Isotropic cantilever and sample two parameters to describe elastic properties Y = young modulus = Poisson ratio • • • Close to the contact point the undeformed surfaces are described by two curvature radii Deformations are small compared to surfaces curvature radii Two spheres r 1 = r 2 Same materials a 2 = h. R deformation and penetration Hertz problem solution: allows to find the contact area radius a and penetration depth h as a function of applied force for a surface (r’= ) and a tip (r=R) contact area radius : up to 10 nm Penetration depth : up to 20 nm contact pressure : up to 10 GPa. the contact pressure is higher for stiffer samples

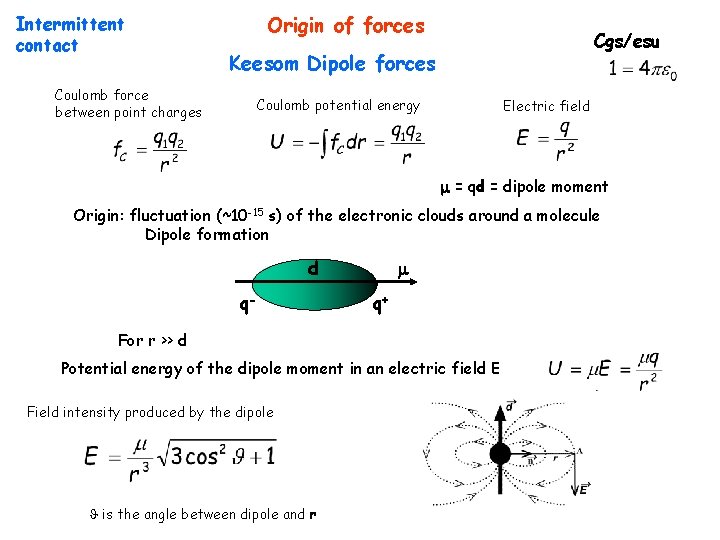

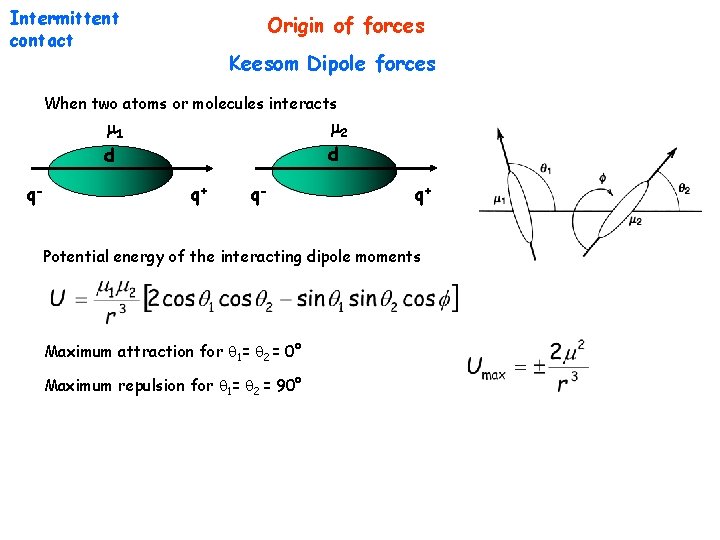

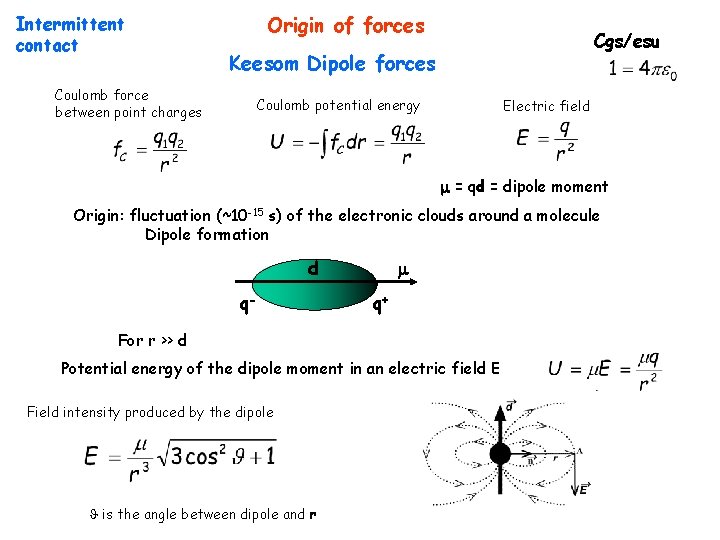

Intermittent contact Origin of forces Cgs/esu Keesom Dipole forces Coulomb force between point charges Coulomb potential energy Electric field = qd = dipole moment Origin: fluctuation (~10 -15 s) of the electronic clouds around a molecule Dipole formation d q- q+ For r >> d Potential energy of the dipole moment in an electric field E Field intensity produced by the dipole is the angle between dipole and r

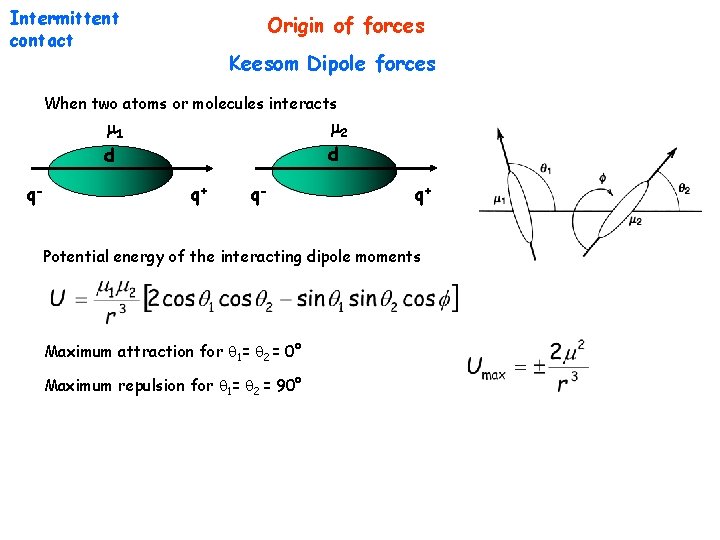

Intermittent contact Origin of forces Keesom Dipole forces When two atoms or molecules interacts 2 1 d d q- q+ Potential energy of the interacting dipole moments Maximum attraction for 1= 2 = 0° Maximum repulsion for 1= 2 = 90°

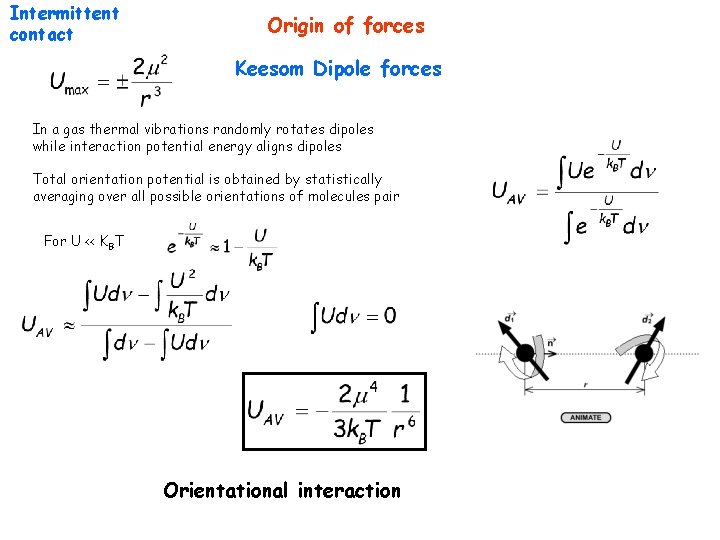

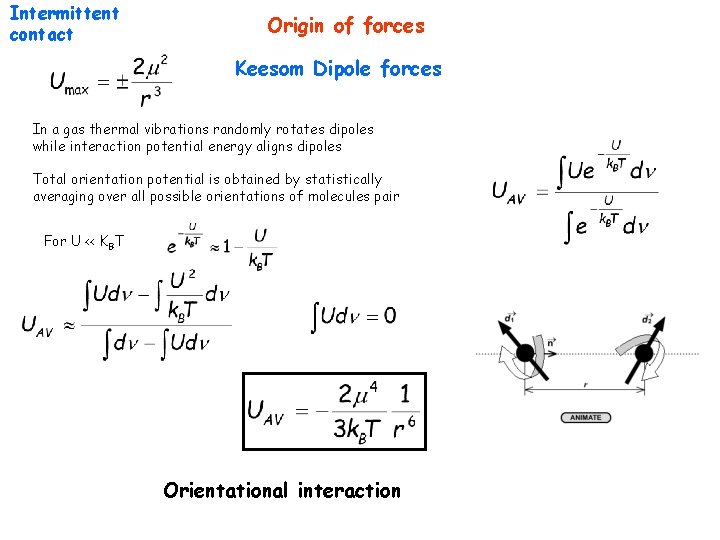

Intermittent contact Origin of forces Keesom Dipole forces In a gas thermal vibrations randomly rotates dipoles while interaction potential energy aligns dipoles Total orientation potential is obtained by statistically averaging over all possible orientations of molecules pair For U << KBT Orientational interaction

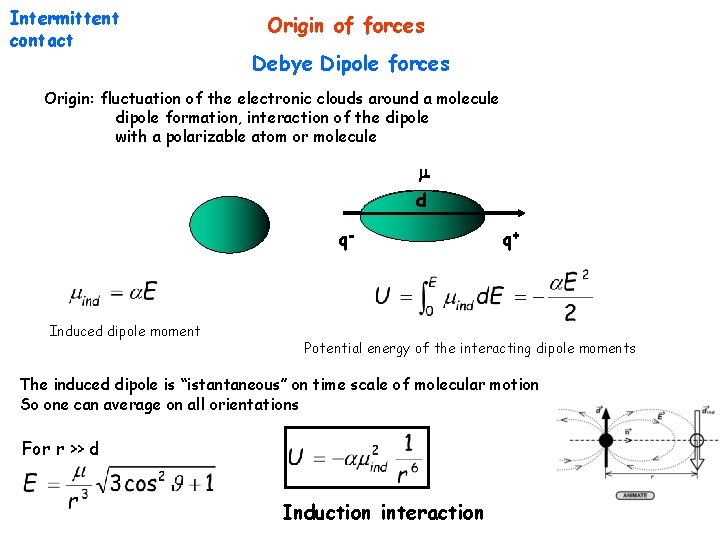

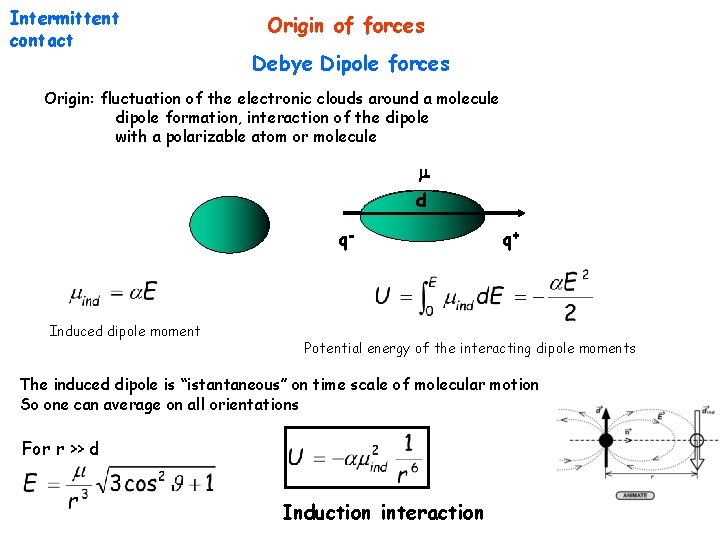

Intermittent contact Origin of forces Debye Dipole forces Origin: fluctuation of the electronic clouds around a molecule dipole formation, interaction of the dipole with a polarizable atom or molecule d q- Induced dipole moment q+ Potential energy of the interacting dipole moments The induced dipole is “istantaneous” on time scale of molecular motion So one can average on all orientations For r >> d Induction interaction

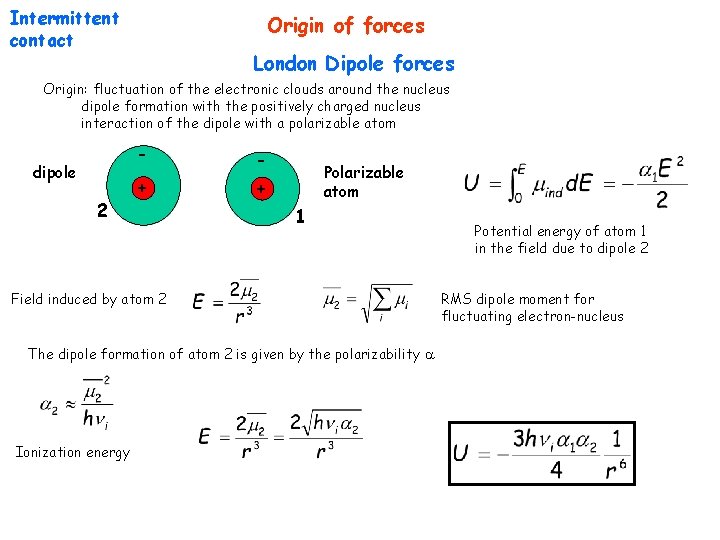

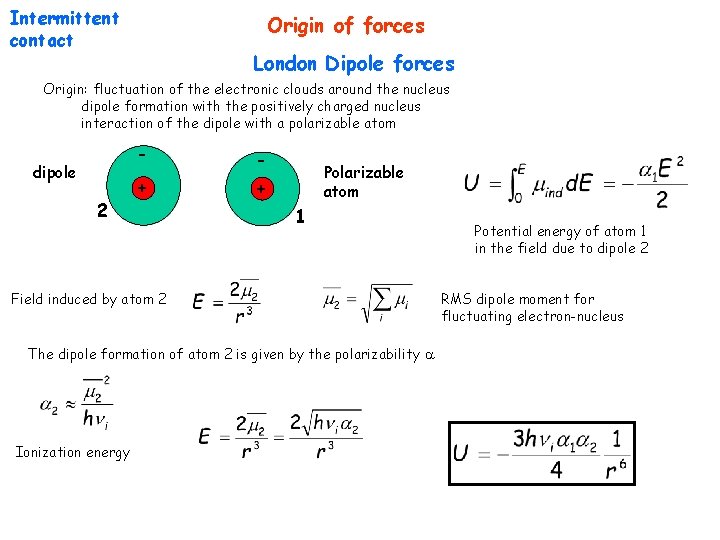

Intermittent contact Origin of forces London Dipole forces Origin: fluctuation of the electronic clouds around the nucleus dipole formation with the positively charged nucleus interaction of the dipole with a polarizable atom dipole 2 - - + + Polarizable atom 1 Field induced by atom 2 The dipole formation of atom 2 is given by the polarizability Ionization energy Potential energy of atom 1 in the field due to dipole 2 RMS dipole moment for fluctuating electron-nucleus

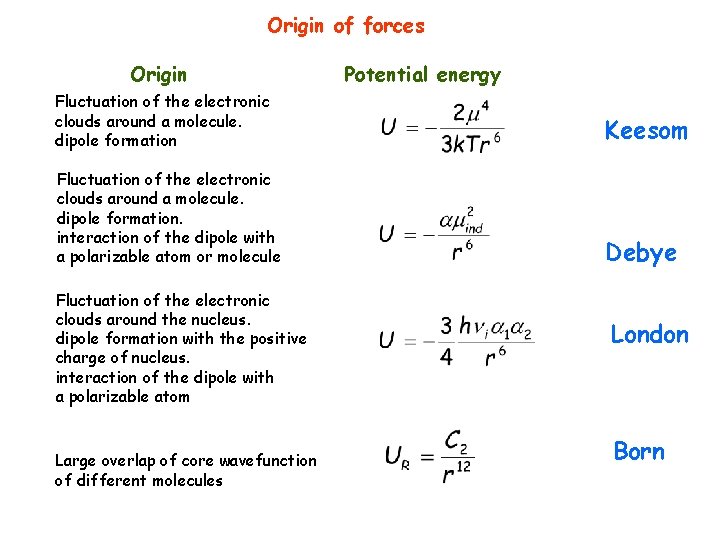

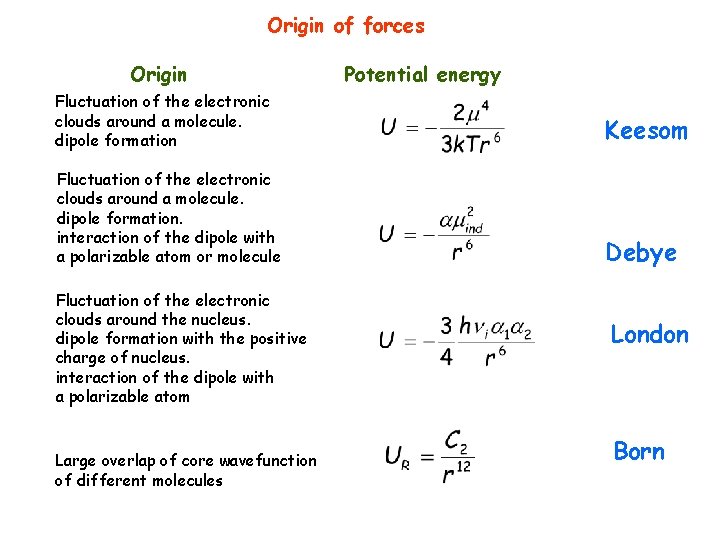

Origin of forces Origin Potential energy Fluctuation of the electronic clouds around a molecule. dipole formation Keesom Fluctuation of the electronic clouds around a molecule. dipole formation. interaction of the dipole with a polarizable atom or molecule Debye Fluctuation of the electronic clouds around the nucleus. dipole formation with the positive charge of nucleus. interaction of the dipole with a polarizable atom Large overlap of core wavefunction of different molecules London Born

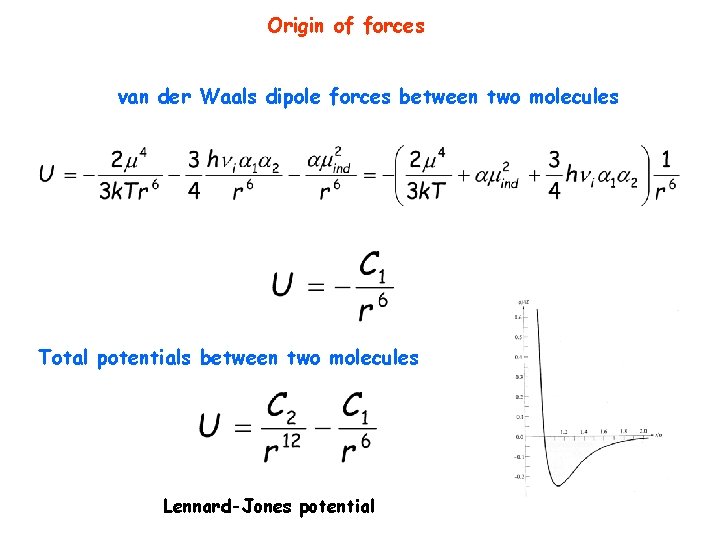

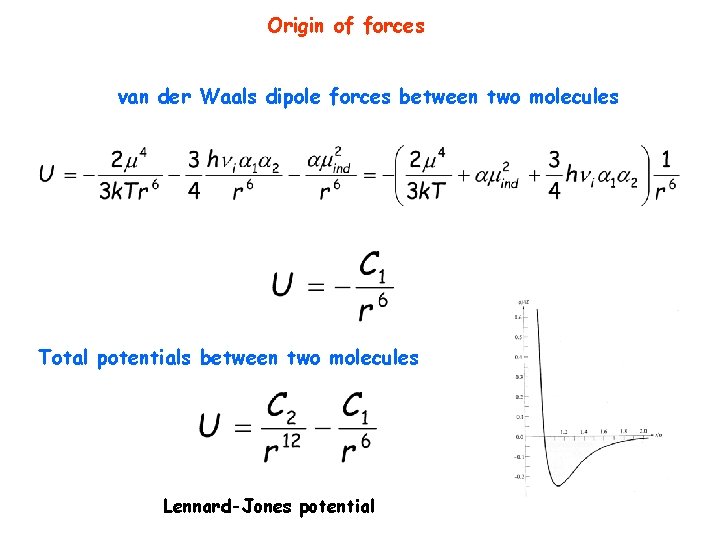

Origin of forces van der Waals dipole forces between two molecules Total potentials between two molecules Lennard-Jones potential

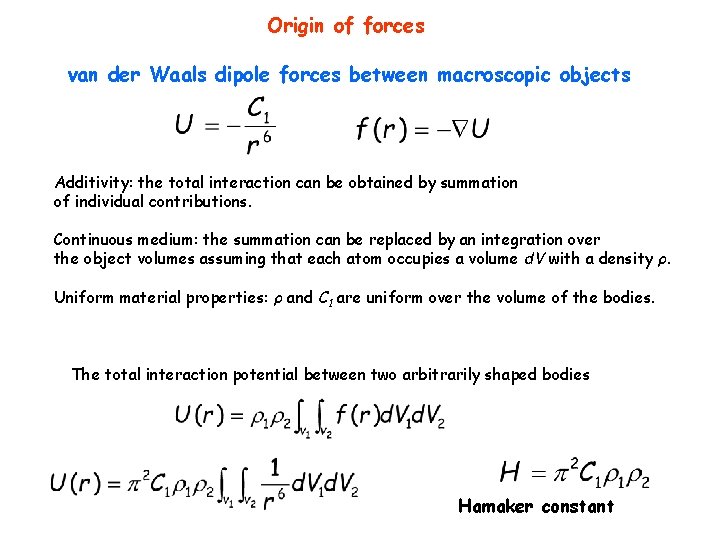

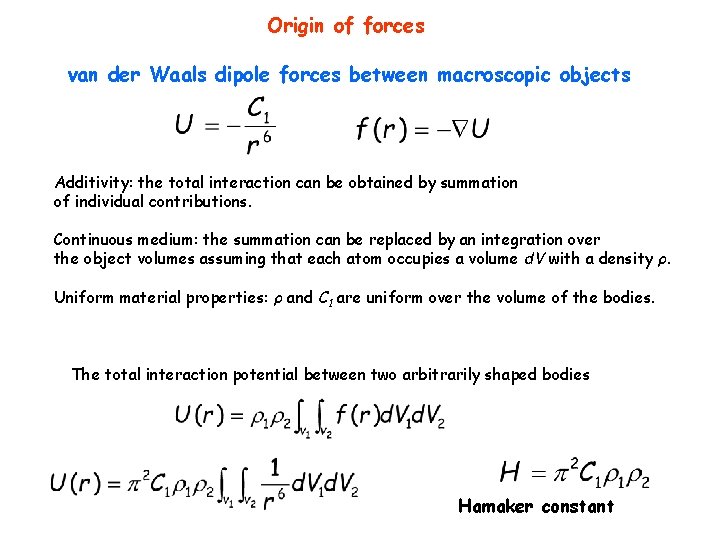

Origin of forces van der Waals dipole forces between macroscopic objects Additivity: the total interaction can be obtained by summation of individual contributions. Continuous medium: the summation can be replaced by an integration over the object volumes assuming that each atom occupies a volume d. V with a density ρ. Uniform material properties: ρ and C 1 are uniform over the volume of the bodies. The total interaction potential between two arbitrarily shaped bodies Hamaker constant

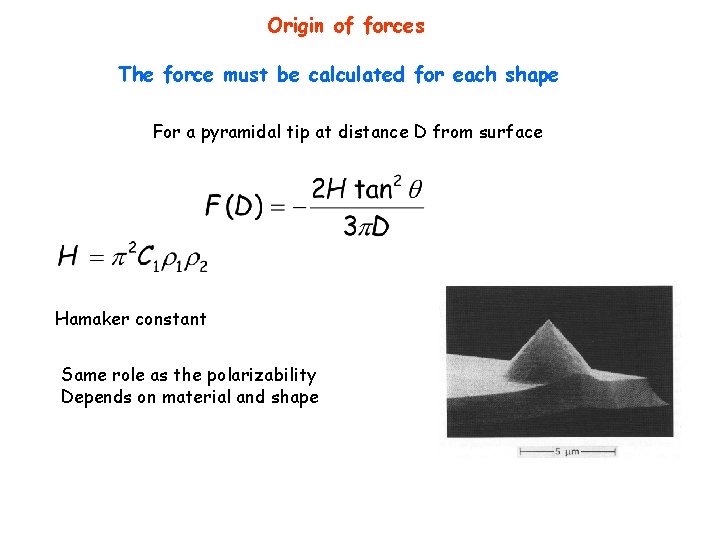

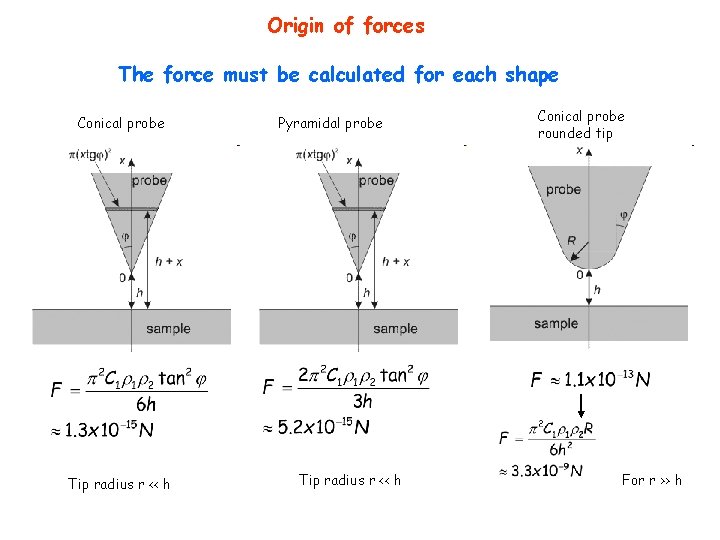

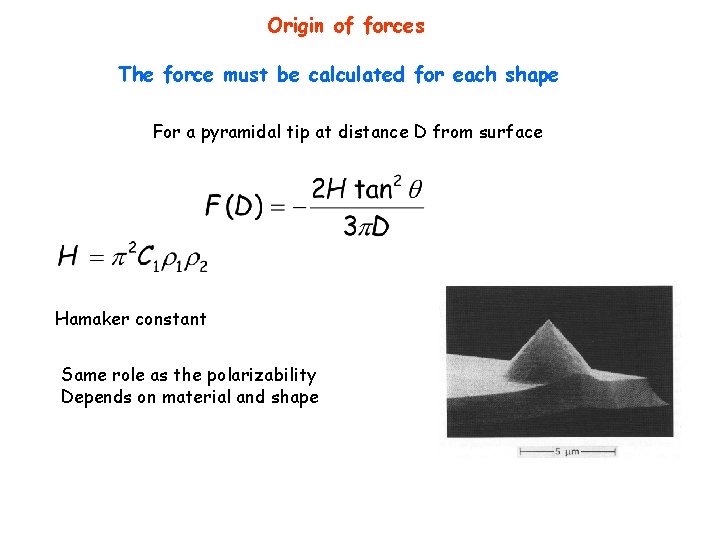

Origin of forces The force must be calculated for each shape For a pyramidal tip at distance D from surface Hamaker constant Same role as the polarizability Depends on material and shape

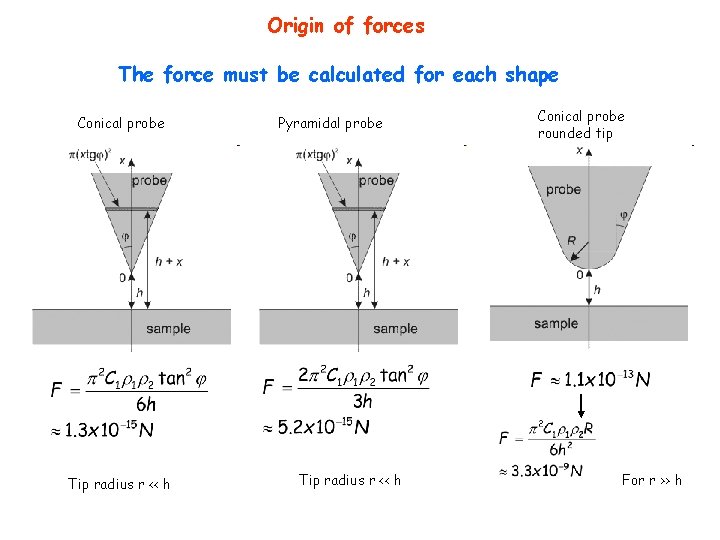

Origin of forces The force must be calculated for each shape Conical probe Tip radius r << h Pyramidal probe Tip radius r << h Conical probe rounded tip For r >> h

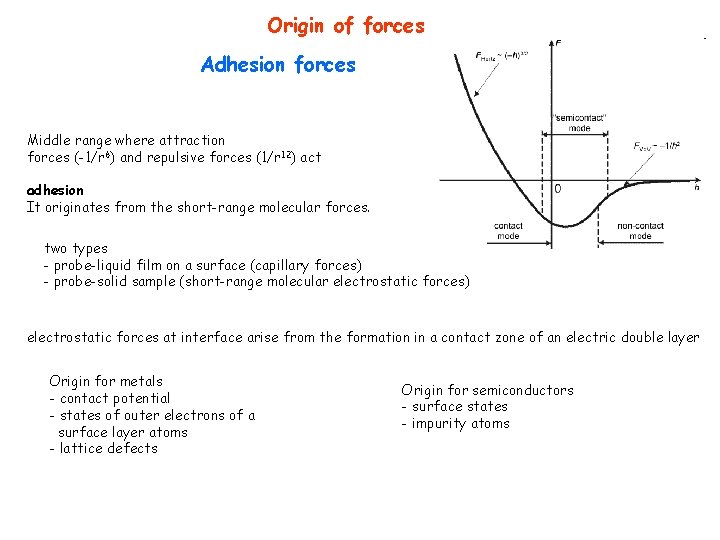

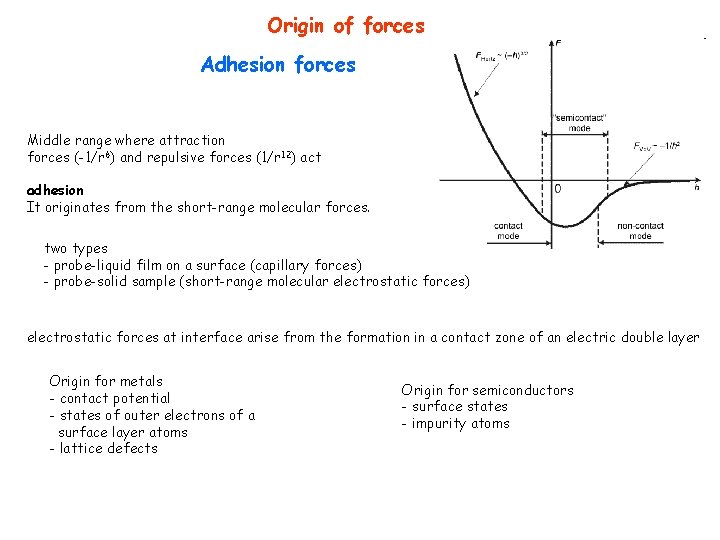

Origin of forces Adhesion forces Middle range where attraction forces (-1/r 6) and repulsive forces (1/r 12) act adhesion It originates from the short-range molecular forces. two types - probe-liquid film on a surface (capillary forces) - probe-solid sample (short-range molecular electrostatic forces) electrostatic forces at interface arise from the formation in a contact zone of an electric double layer Origin for metals - contact potential - states of outer electrons of a surface layer atoms - lattice defects Origin for semiconductors - surface states - impurity atoms

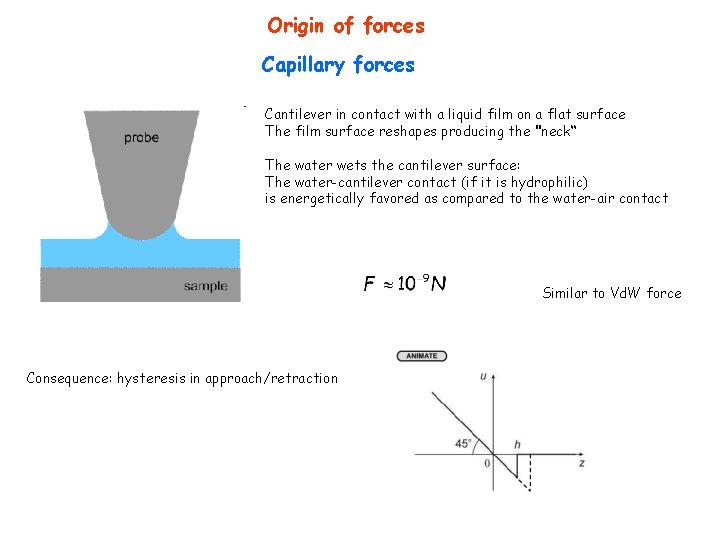

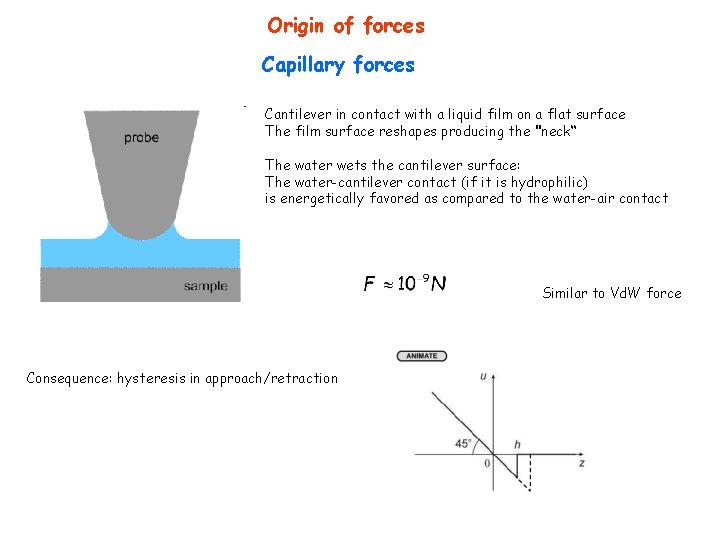

Origin of forces Capillary forces Cantilever in contact with a liquid film on a flat surface The film surface reshapes producing the "neck“ The water wets the cantilever surface: The water-cantilever contact (if it is hydrophilic) is energetically favored as compared to the water-air contact Similar to Vd. W force Consequence: hysteresis in approach/retraction

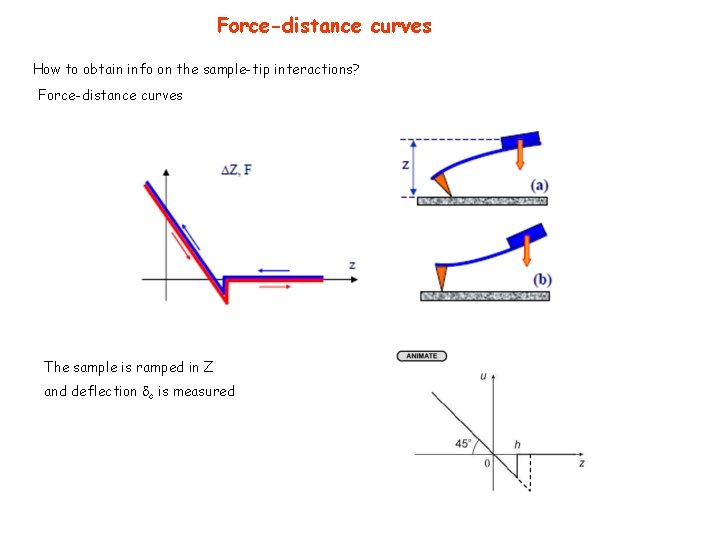

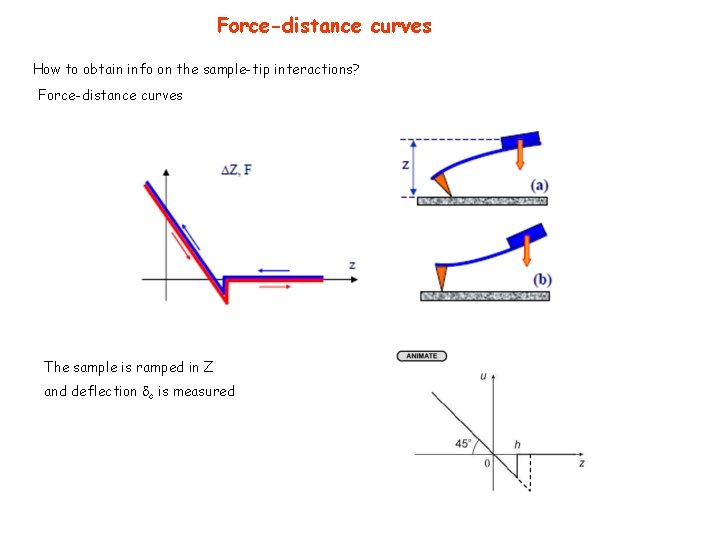

Force-distance curves How to obtain info on the sample-tip interactions? Force-distance curves The sample is ramped in Z and deflection c is measured

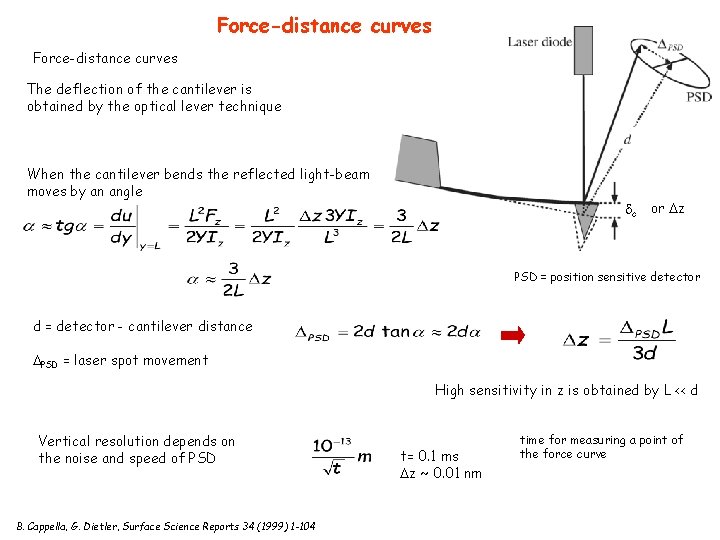

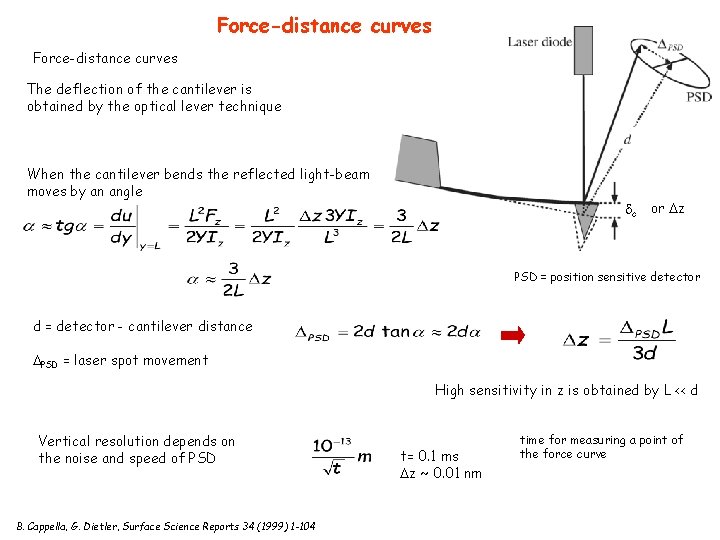

Force-distance curves The deflection of the cantilever is obtained by the optical lever technique When the cantilever bends the reflected light-beam moves by an angle c or z PSD = position sensitive detector d = detector - cantilever distance PSD = laser spot movement High sensitivity in z is obtained by L << d Vertical resolution depends on the noise and speed of PSD B. Cappella, G. Dietler, Surface Science Reports 34 (1999) 1 -104 t= 0. 1 ms z ~ 0. 01 nm time for measuring a point of the force curve

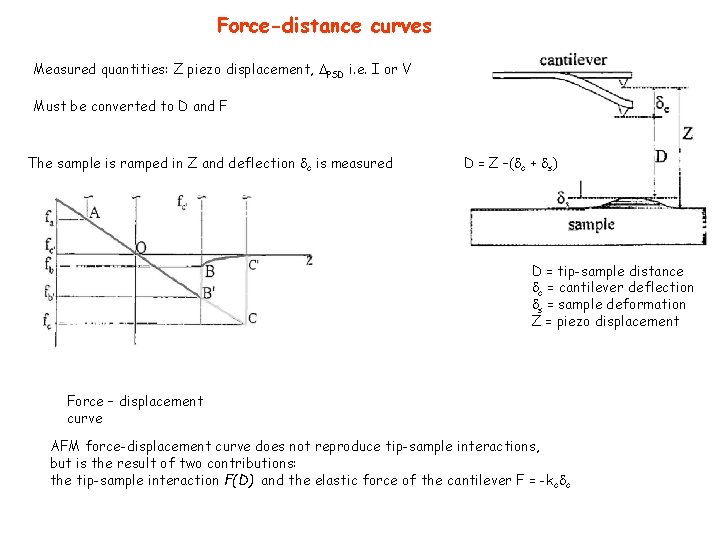

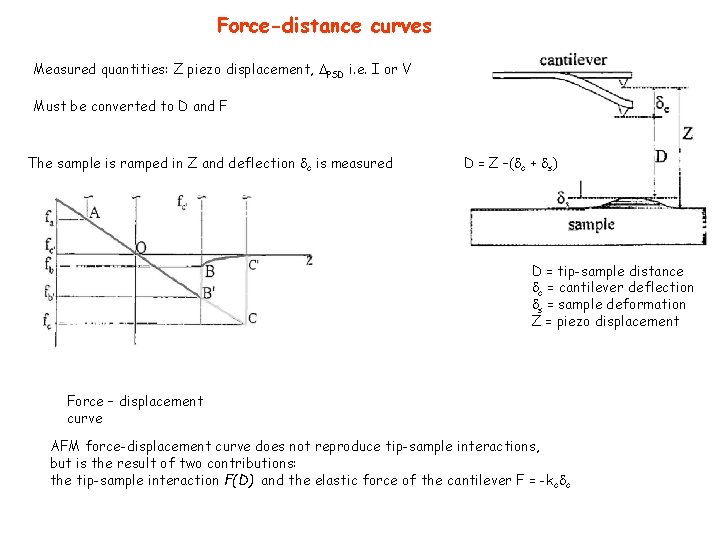

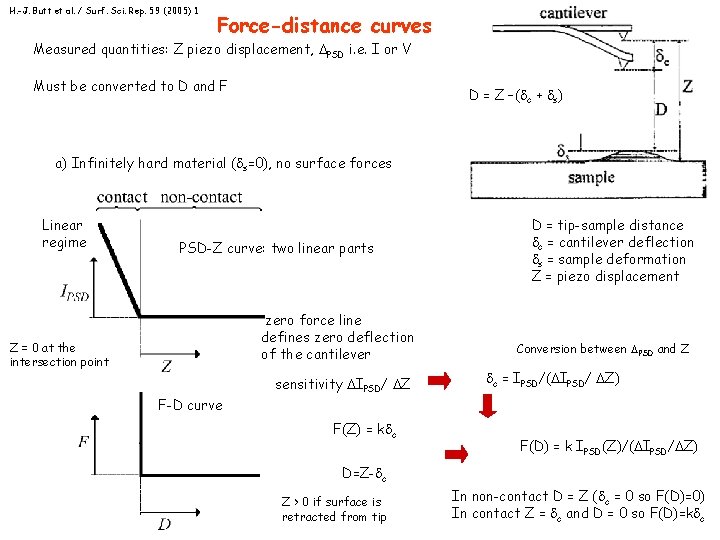

Force-distance curves Measured quantities: Z piezo displacement, PSD i. e. I or V Must be converted to D and F The sample is ramped in Z and deflection c is measured D = Z –( c + s) D = tip-sample distance c = cantilever deflection s = sample deformation Z = piezo displacement Force – displacement curve AFM force-displacement curve does not reproduce tip-sample interactions, but is the result of two contributions: the tip-sample interaction F(D) and the elastic force of the cantilever F = -kc c

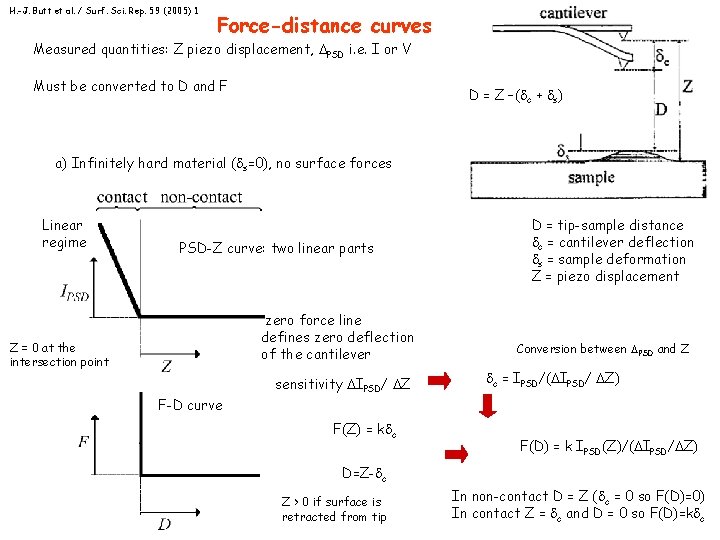

H. -J. Butt et al. / Surf. Sci. Rep. 59 (2005) 1 Force-distance curves Measured quantities: Z piezo displacement, PSD i. e. I or V Must be converted to D and F D = Z –( c + s) a) Infinitely hard material ( s=0), no surface forces Linear regime PSD-Z curve: two linear parts zero force line defines zero deflection of the cantilever Z = 0 at the intersection point F-D curve sensitivity IPSD/ Z F(Z) = k c D = tip-sample distance c = cantilever deflection s = sample deformation Z = piezo displacement Conversion between PSD and Z c = IPSD/( IPSD/ Z) F(D) = k IPSD(Z)/( IPSD/ Z) D=Z- c Z > 0 if surface is retracted from tip In non-contact D = Z ( c = 0 so F(D)=0) In contact Z = c and D = 0 so F(D)=k c

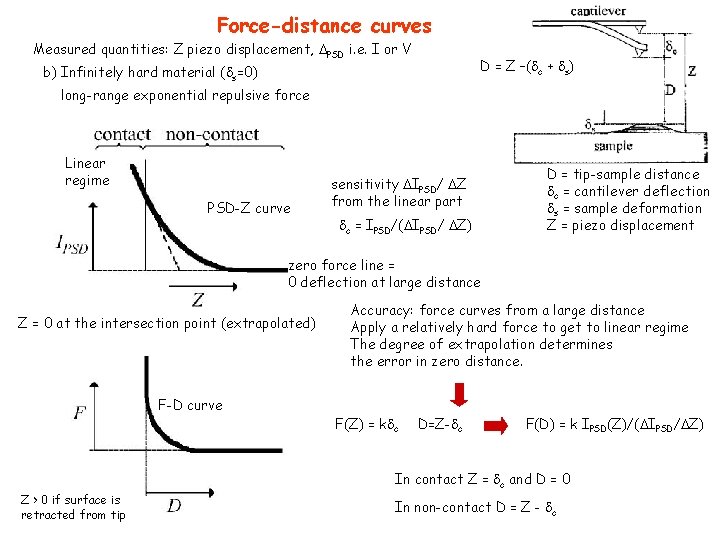

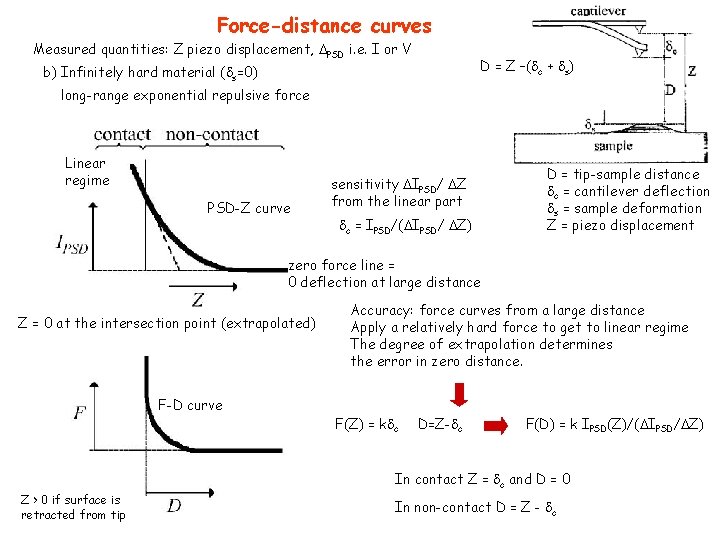

Force-distance curves Measured quantities: Z piezo displacement, PSD i. e. I or V D = Z –( c + s) b) Infinitely hard material ( s=0) long-range exponential repulsive force Linear regime PSD-Z curve sensitivity IPSD/ Z from the linear part c = IPSD/( IPSD/ Z) D = tip-sample distance c = cantilever deflection s = sample deformation Z = piezo displacement zero force line = 0 deflection at large distance Z = 0 at the intersection point (extrapolated) F-D curve Accuracy: force curves from a large distance Apply a relatively hard force to get to linear regime The degree of extrapolation determines the error in zero distance. F(Z) = k c D=Z- c F(D) = k IPSD(Z)/( IPSD/ Z) In contact Z = c and D = 0 Z > 0 if surface is retracted from tip In non-contact D = Z - c

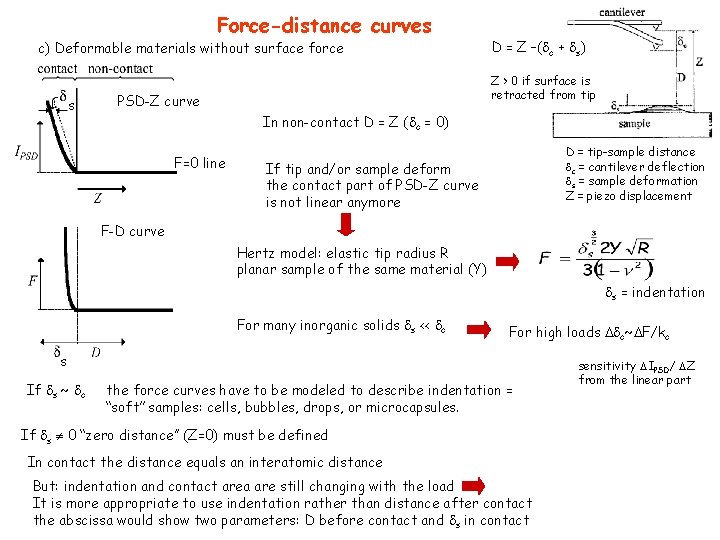

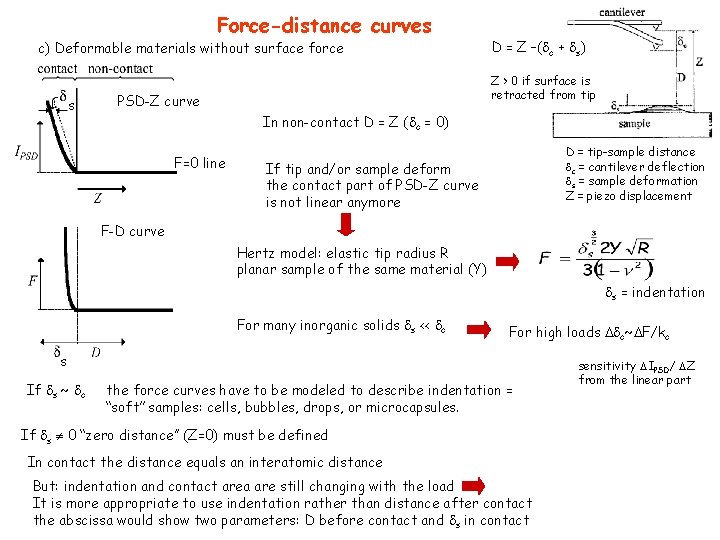

Force-distance curves c) Deformable materials without surface force s D = Z –( c + s) Z > 0 if surface is retracted from tip PSD-Z curve In non-contact D = Z ( c = 0) F=0 line D = tip-sample distance c = cantilever deflection s = sample deformation Z = piezo displacement If tip and/or sample deform the contact part of PSD-Z curve is not linear anymore F-D curve Hertz model: elastic tip radius R planar sample of the same material (Y) s = indentation For many inorganic solids s << c For high loads c~ F/kc s If s ~ c the force curves have to be modeled to describe indentation = ‘‘soft’’ samples: cells, bubbles, drops, or microcapsules. If s 0 ‘‘zero distance’’ (Z=0) must be defined In contact the distance equals an interatomic distance But: indentation and contact area are still changing with the load It is more appropriate to use indentation rather than distance after contact the abscissa would show two parameters: D before contact and s in contact sensitivity IPSD/ Z from the linear part

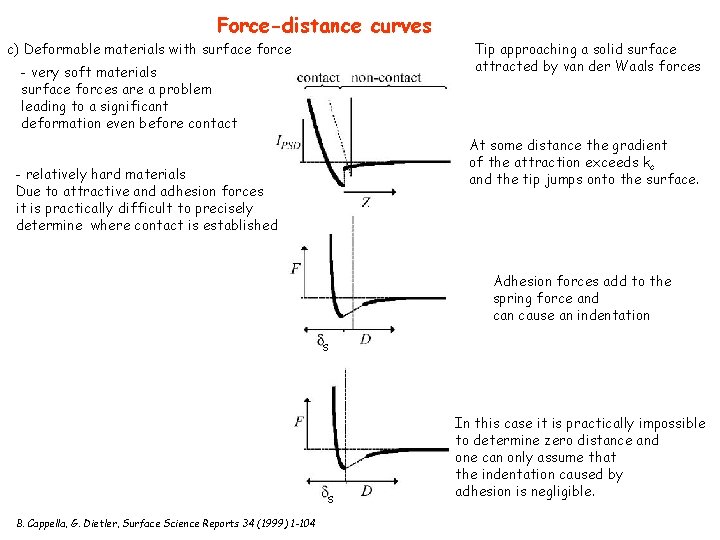

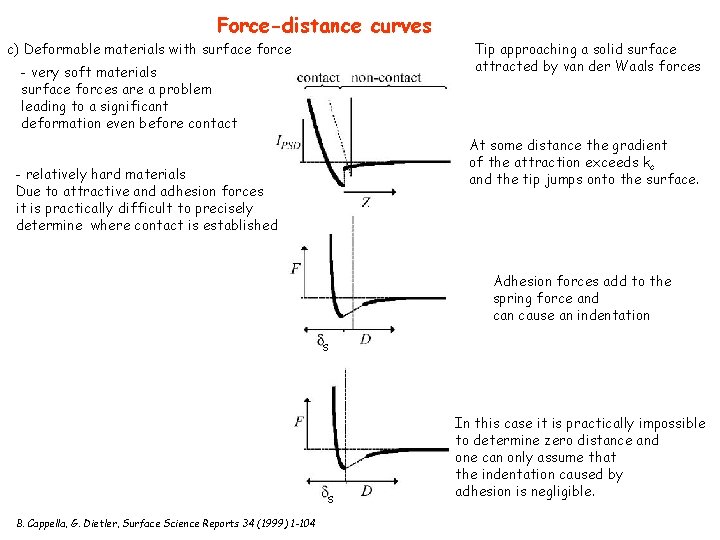

Force-distance curves c) Deformable materials with surface force Tip approaching a solid surface attracted by van der Waals forces - very soft materials surface forces are a problem leading to a significant deformation even before contact At some distance the gradient of the attraction exceeds kc and the tip jumps onto the surface. - relatively hard materials Due to attractive and adhesion forces it is practically difficult to precisely determine where contact is established Adhesion forces add to the spring force and can cause an indentation s s B. Cappella, G. Dietler, Surface Science Reports 34 (1999) 1 -104 In this case it is practically impossible to determine zero distance and one can only assume that the indentation caused by adhesion is negligible.

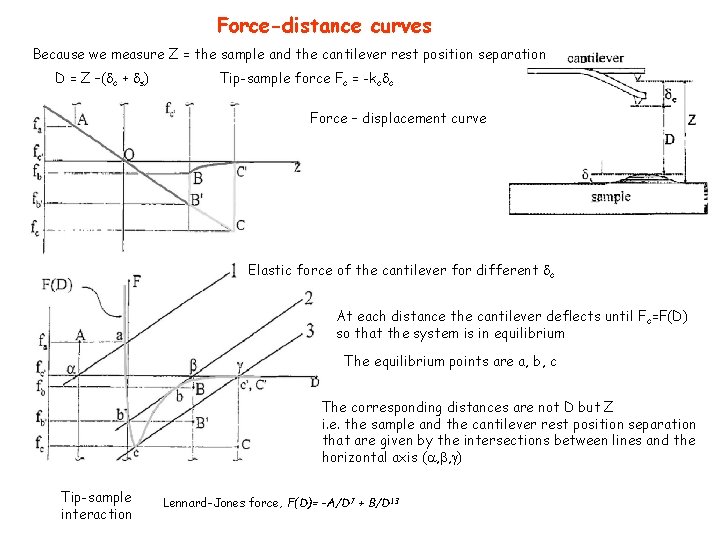

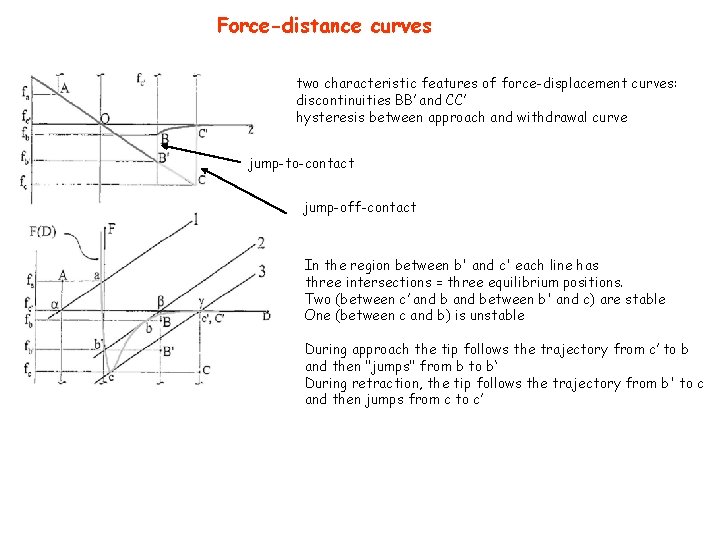

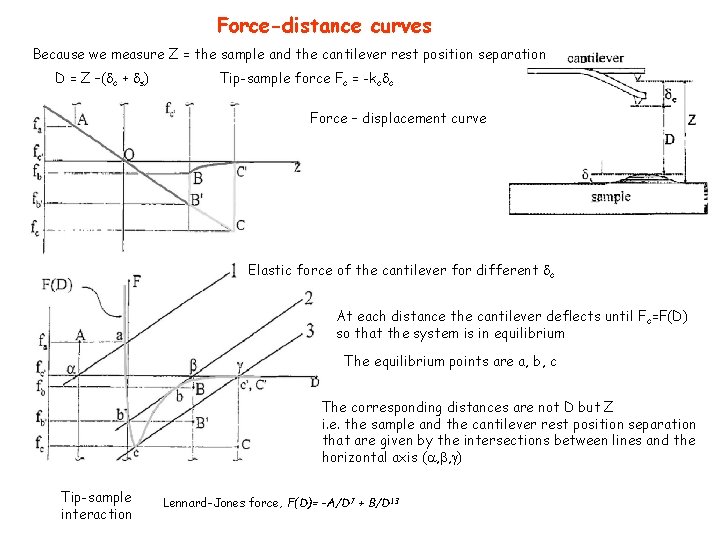

Force-distance curves Because we measure Z = the sample and the cantilever rest position separation D = Z –( c + s) Tip-sample force Fc = -kc c Force – displacement curve Elastic force of the cantilever for different c At each distance the cantilever deflects until Fc=F(D) so that the system is in equilibrium The equilibrium points are a, b, c The corresponding distances are not D but Z i. e. the sample and the cantilever rest position separation that are given by the intersections between lines and the horizontal axis ( , , ) Tip-sample interaction Lennard-Jones force, F(D)= -A/D 7 + B/D 13

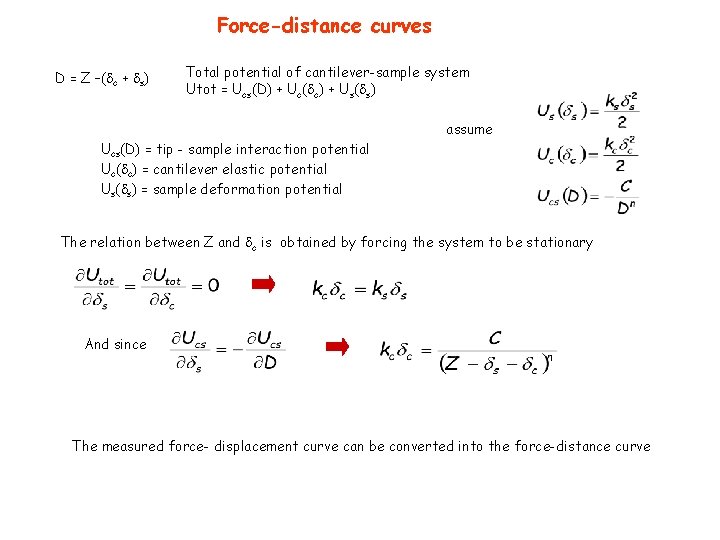

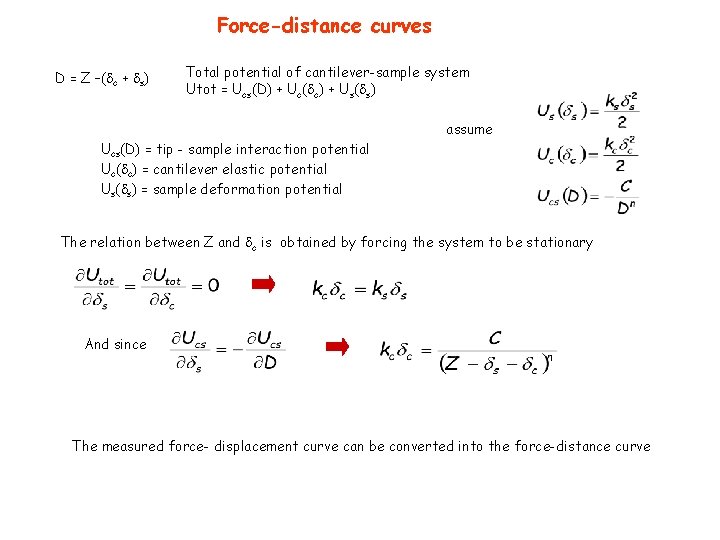

Force-distance curves D = Z –( c + s) Total potential of cantilever-sample system Utot = Ucs(D) + Uc( c) + Us( s) assume Ucs(D) = tip - sample interaction potential Uc( c) = cantilever elastic potential Us( s) = sample deformation potential The relation between Z and c is obtained by forcing the system to be stationary And since The measured force- displacement curve can be converted into the force-distance curve

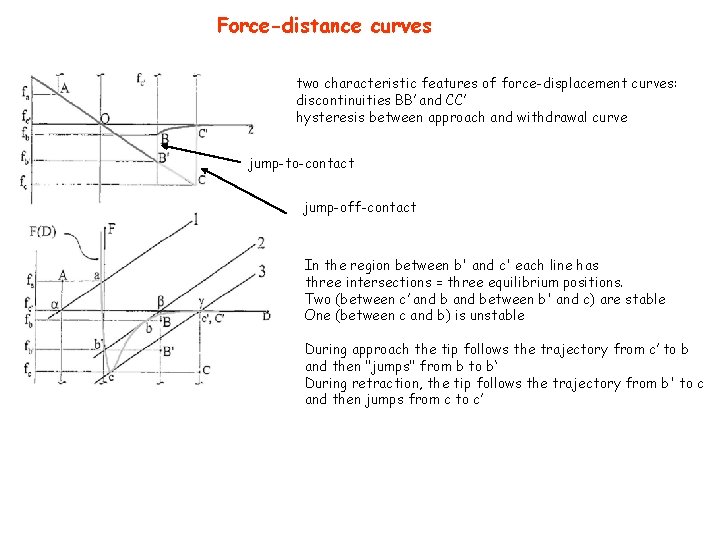

Force-distance curves two characteristic features of force-displacement curves: discontinuities BB’ and CC’ hysteresis between approach and withdrawal curve jump-to-contact jump-off-contact In the region between b' and c' each line has three intersections = three equilibrium positions. Two (between c’ and between b' and c) are stable One (between c and b) is unstable During approach the tip follows the trajectory from c’ to b and then "jumps" from b to b‘ During retraction, the tip follows the trajectory from b' to c and then jumps from c to c’

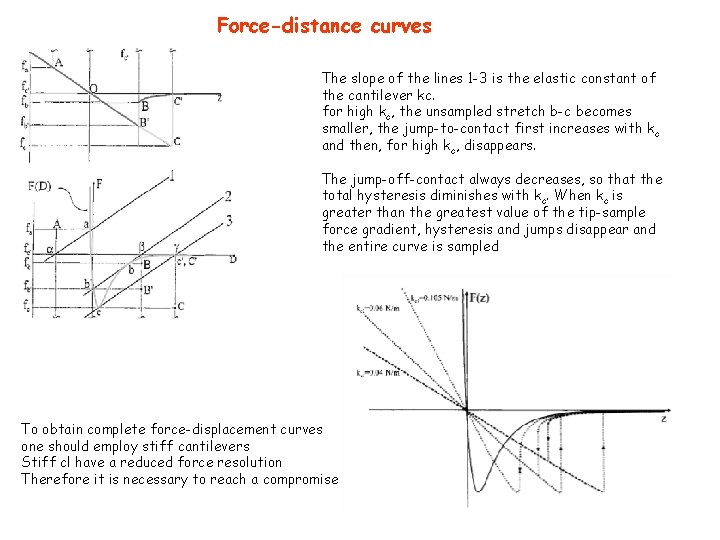

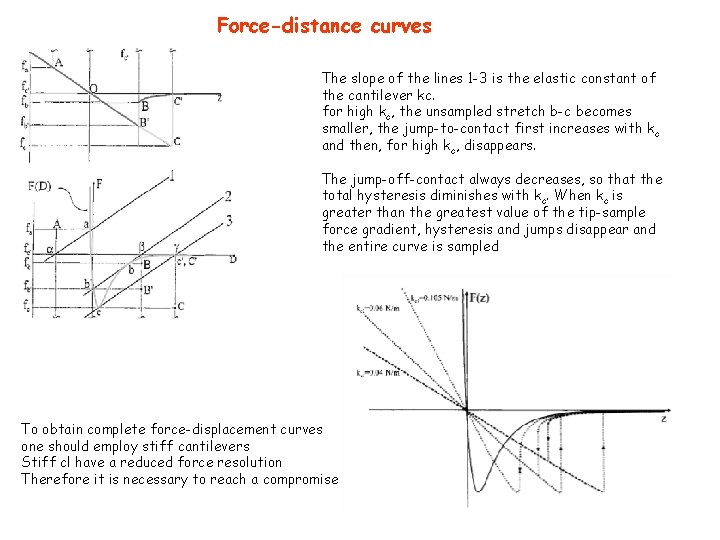

Force-distance curves The slope of the lines 1 -3 is the elastic constant of the cantilever kc. for high kc, the unsampled stretch b-c becomes smaller, the jump-to-contact first increases with kc and then, for high kc, disappears. The jump-off-contact always decreases, so that the total hysteresis diminishes with kc. When kc is greater than the greatest value of the tip-sample force gradient, hysteresis and jumps disappear and the entire curve is sampled To obtain complete force-displacement curves one should employ stiff cantilevers Stiff cl have a reduced force resolution Therefore it is necessary to reach a compromise

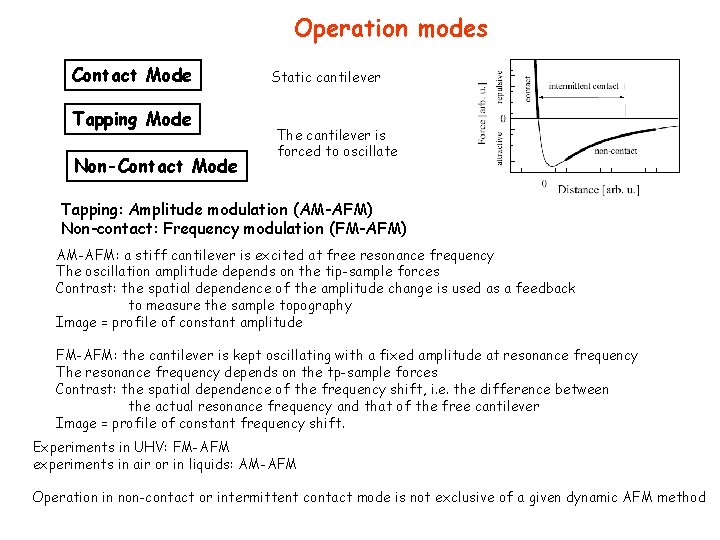

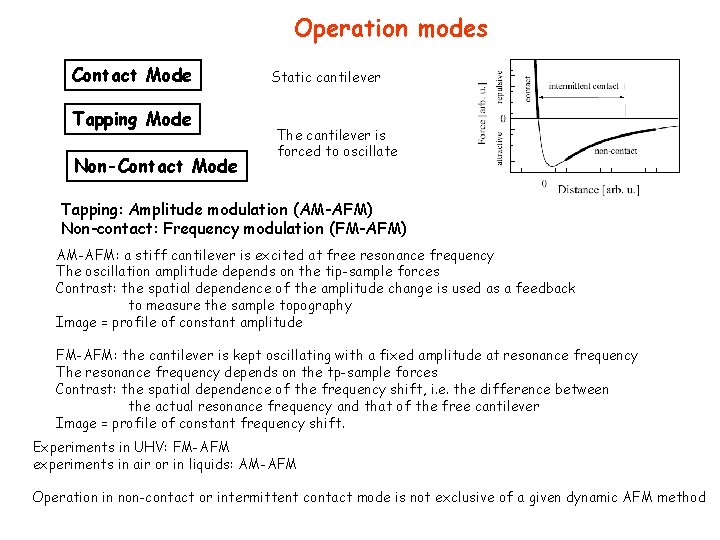

Operation modes Contact Mode Tapping Mode Non-Contact Mode Static cantilever The cantilever is forced to oscillate Tapping: Amplitude modulation (AM-AFM) Non-contact: Frequency modulation (FM-AFM) AM-AFM: a stiff cantilever is excited at free resonance frequency The oscillation amplitude depends on the tip-sample forces Contrast: the spatial dependence of the amplitude change is used as a feedback to measure the sample topography Image = profile of constant amplitude FM-AFM: the cantilever is kept oscillating with a fixed amplitude at resonance frequency The resonance frequency depends on the tp-sample forces Contrast: the spatial dependence of the frequency shift, i. e. the difference between the actual resonance frequency and that of the free cantilever Image = profile of constant frequency shift. Experiments in UHV: FM-AFM experiments in air or in liquids: AM-AFM Operation in non-contact or intermittent contact mode is not exclusive of a given dynamic AFM method

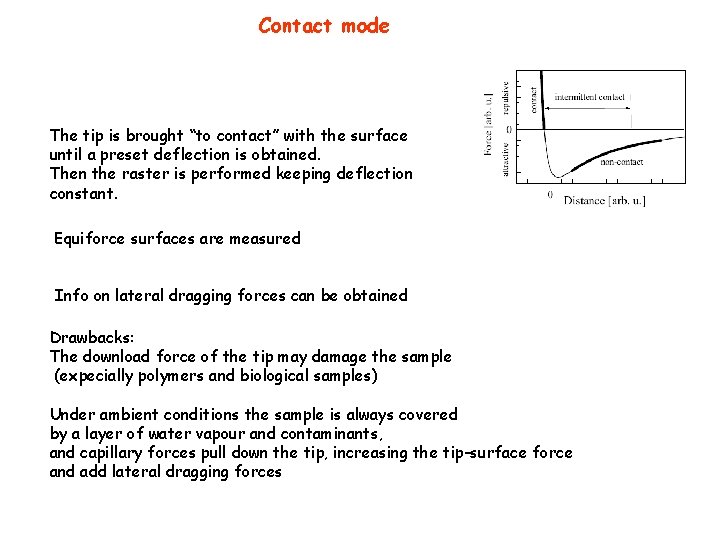

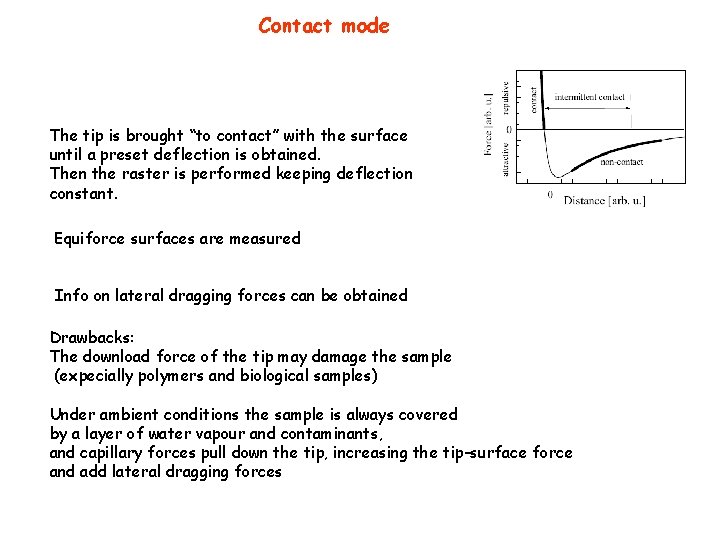

Contact mode The tip is brought “to contact” with the surface until a preset deflection is obtained. Then the raster is performed keeping deflection constant. Equiforce surfaces are measured Info on lateral dragging forces can be obtained Drawbacks: The download force of the tip may damage the sample (expecially polymers and biological samples) Under ambient conditions the sample is always covered by a layer of water vapour and contaminants, and capillary forces pull down the tip, increasing the tip-surface force and add lateral dragging forces

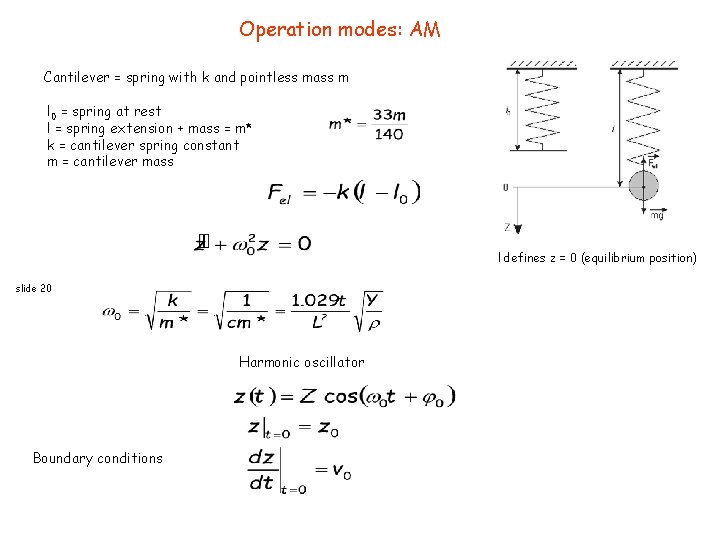

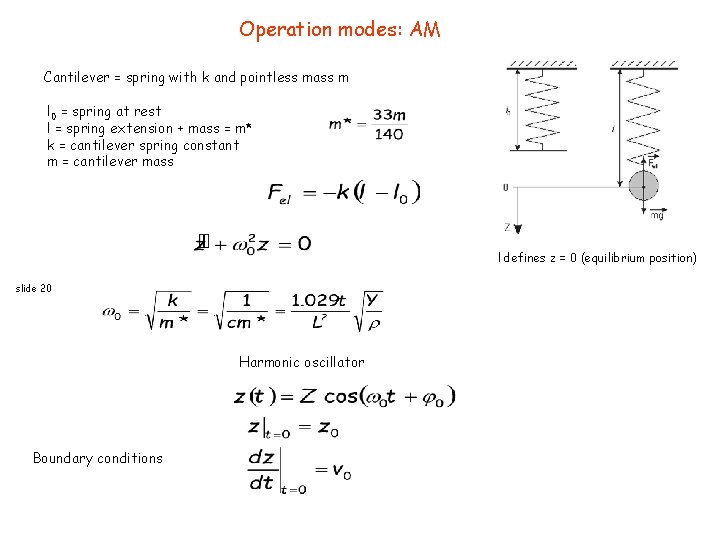

Operation modes: AM Cantilever = spring with k and pointless mass m l 0 = spring at rest l = spring extension + mass = m* k = cantilever spring constant m = cantilever mass l defines z = 0 (equilibrium position) slide 20 Harmonic oscillator Boundary conditions

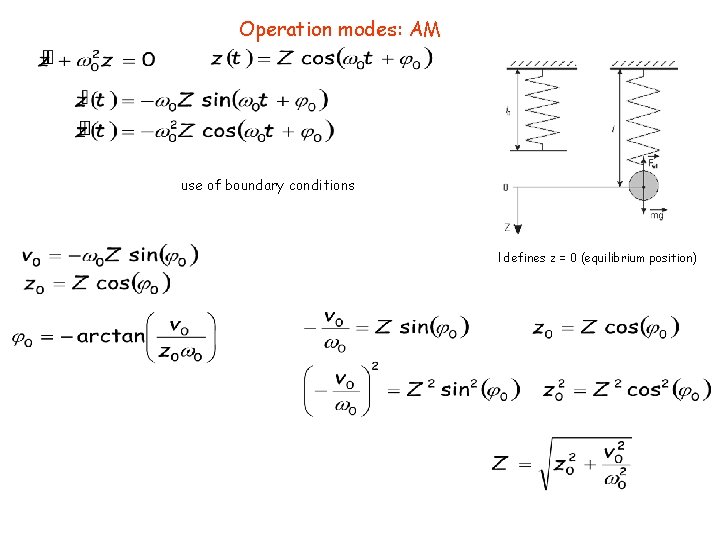

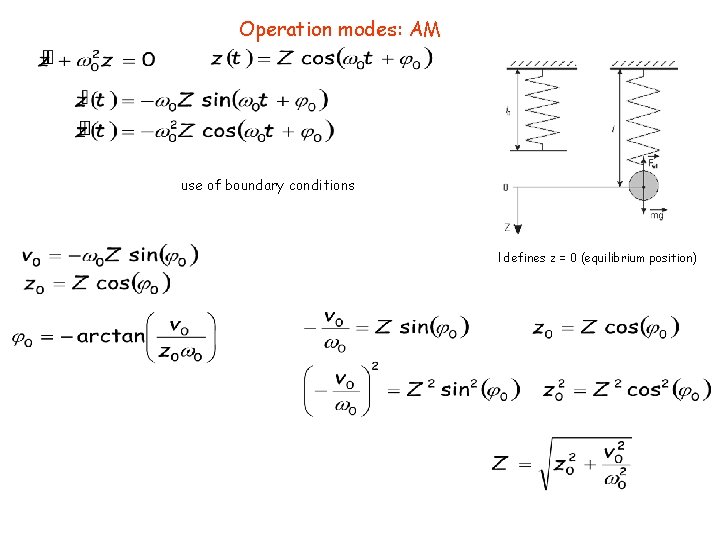

Operation modes: AM use of boundary conditions l defines z = 0 (equilibrium position)

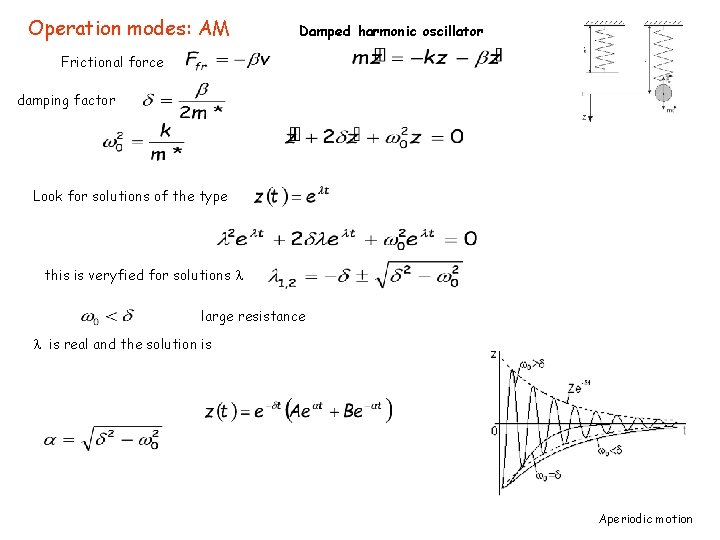

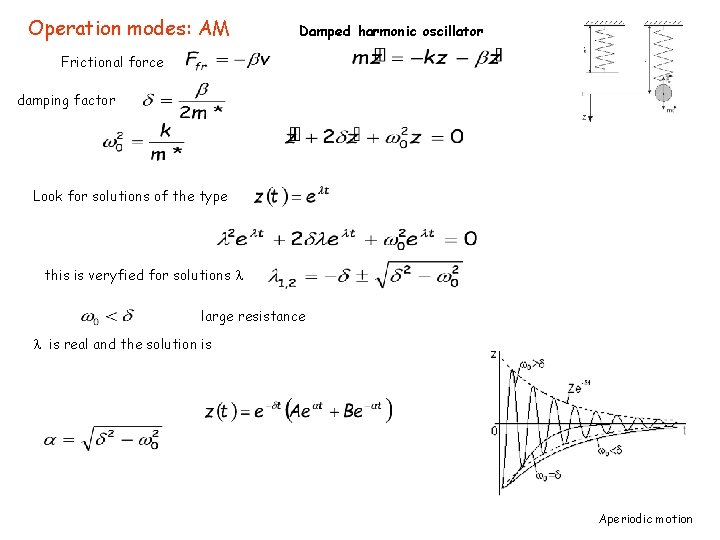

Operation modes: AM Damped harmonic oscillator Frictional force damping factor Look for solutions of the type this is veryfied for solutions large resistance is real and the solution is Aperiodic motion

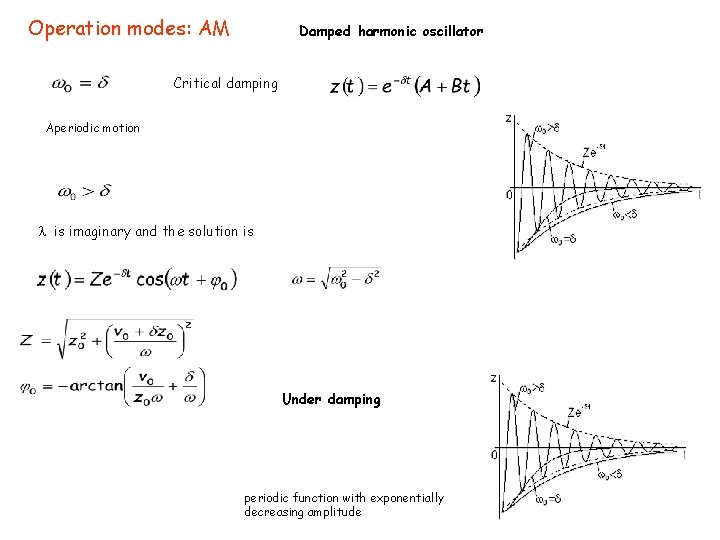

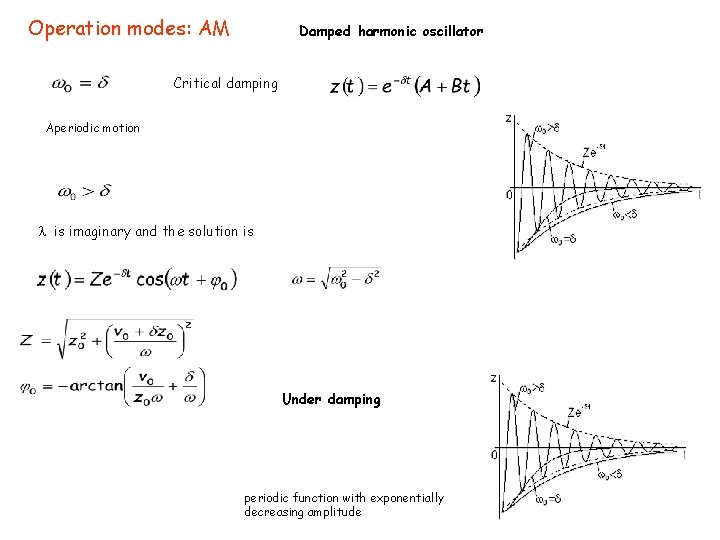

Operation modes: AM Damped harmonic oscillator Critical damping Aperiodic motion is imaginary and the solution is Under damping periodic function with exponentially decreasing amplitude

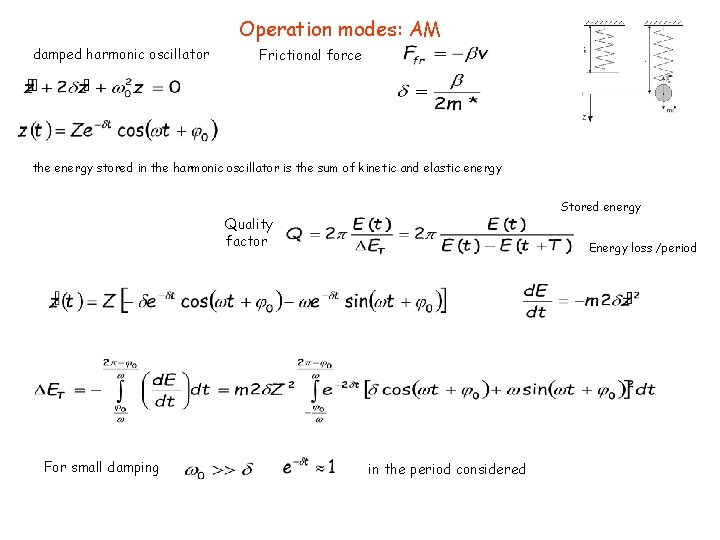

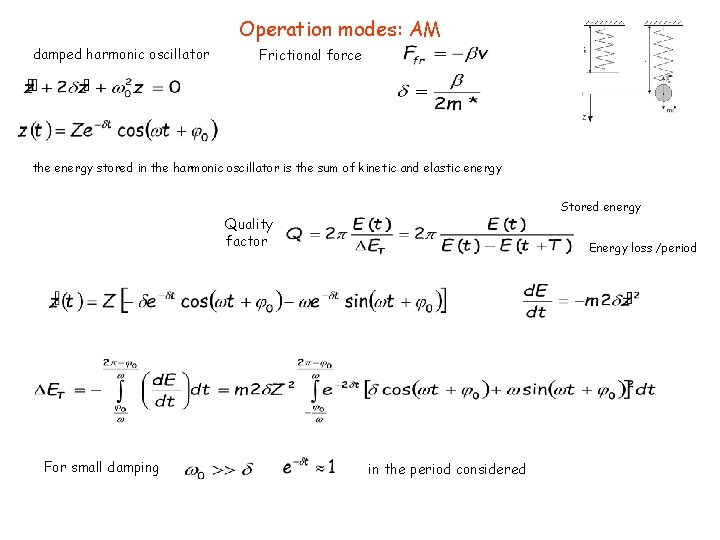

Operation modes: AM damped harmonic oscillator Frictional force the energy stored in the harmonic oscillator is the sum of kinetic and elastic energy Stored energy Quality factor For small damping Energy loss /period in the period considered

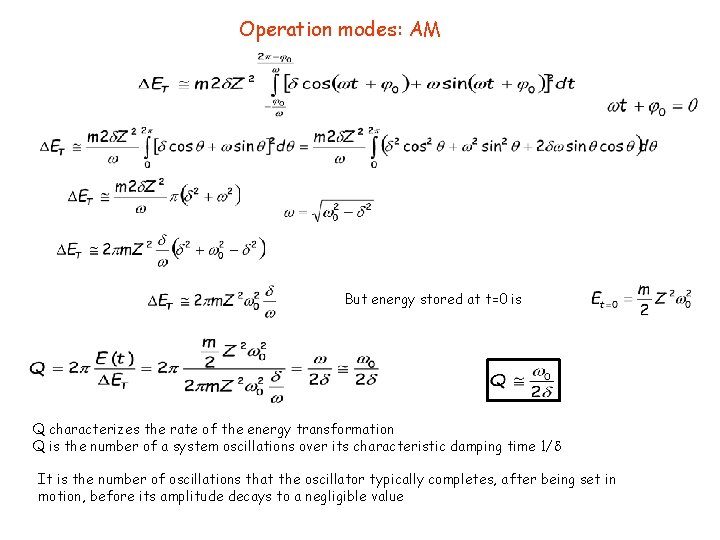

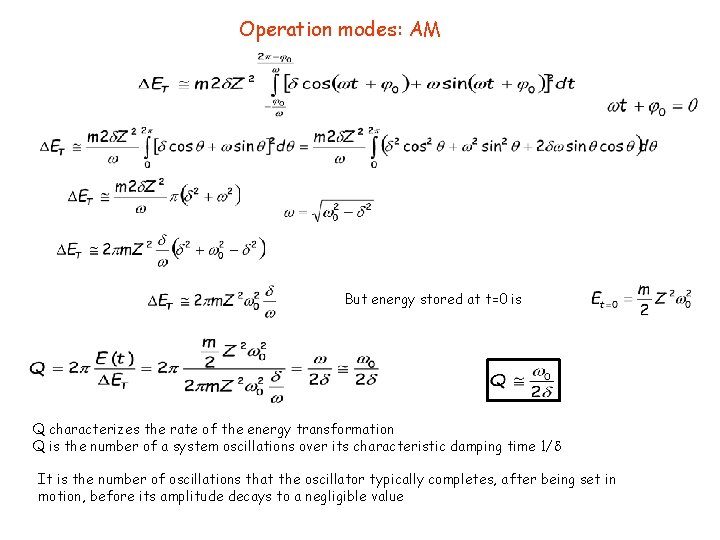

Operation modes: AM But energy stored at t=0 is Q characterizes the rate of the energy transformation Q is the number of a system oscillations over its characteristic damping time 1/ It is the number of oscillations that the oscillator typically completes, after being set in motion, before its amplitude decays to a negligible value

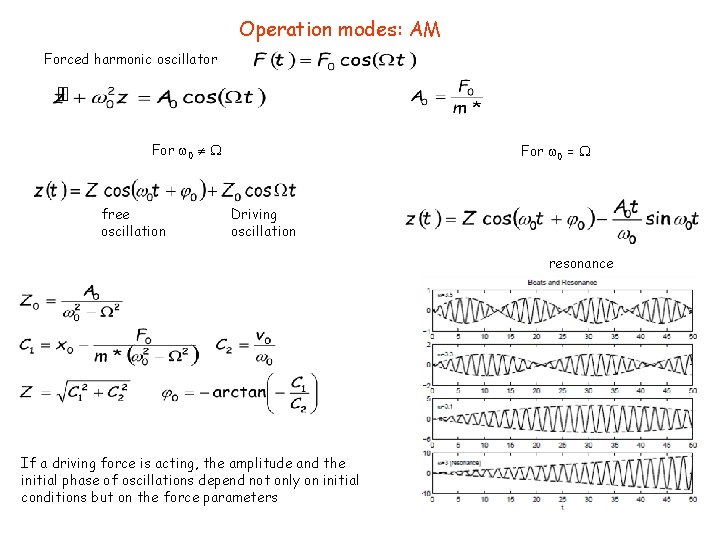

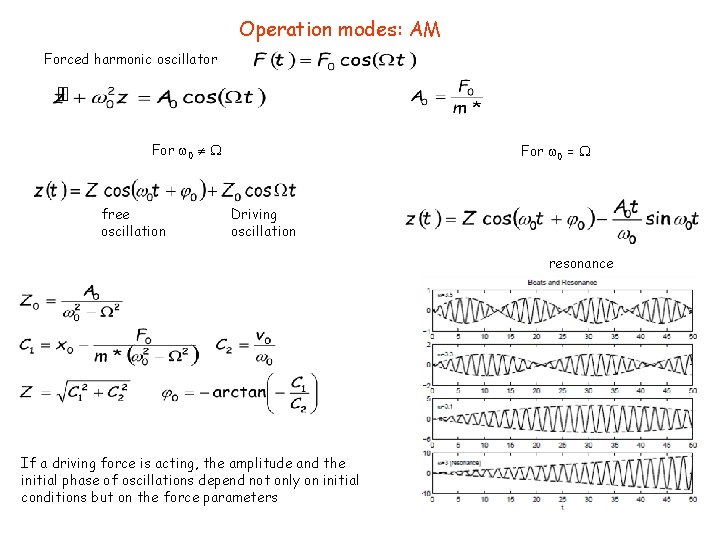

Operation modes: AM Forced harmonic oscillator For 0 free oscillation For 0 = Driving oscillation resonance If a driving force is acting, the amplitude and the initial phase of oscillations depend not only on initial conditions but on the force parameters

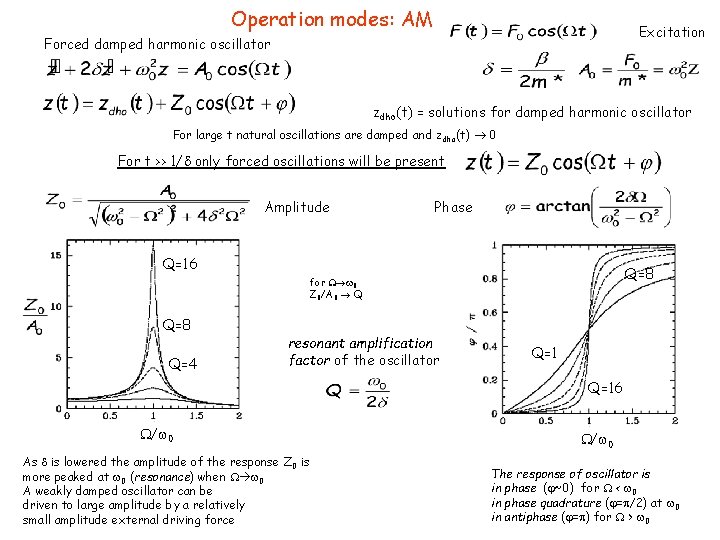

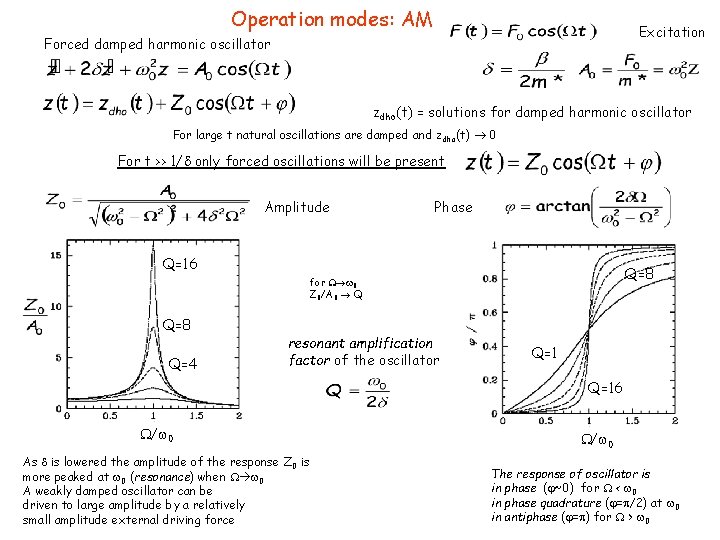

Operation modes: AM Excitation Forced damped harmonic oscillator zdho(t) = solutions for damped harmonic oscillator For large t natural oscillations are damped and zdho(t) 0 For t >> 1/ only forced oscillations will be present Amplitude Phase Q=16 Q=8 for 0 Z 0/A 0 Q Q=8 Q=4 resonant amplification factor of the oscillator Q=16 / 0 As is lowered the amplitude of the response Z 0 is more peaked at 0 (resonance) when 0 A weakly damped oscillator can be driven to large amplitude by a relatively small amplitude external driving force / 0 The response of oscillator is in phase ( ~0) for < 0 in phase quadrature ( = /2) at 0 in antiphase ( = ) for > 0

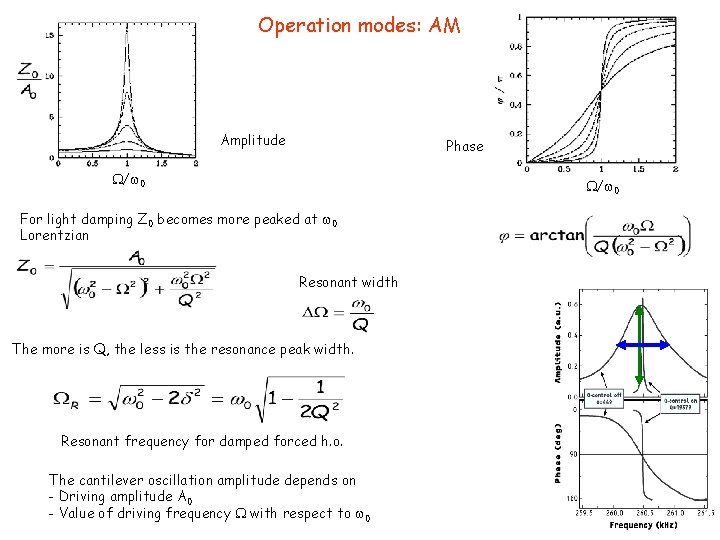

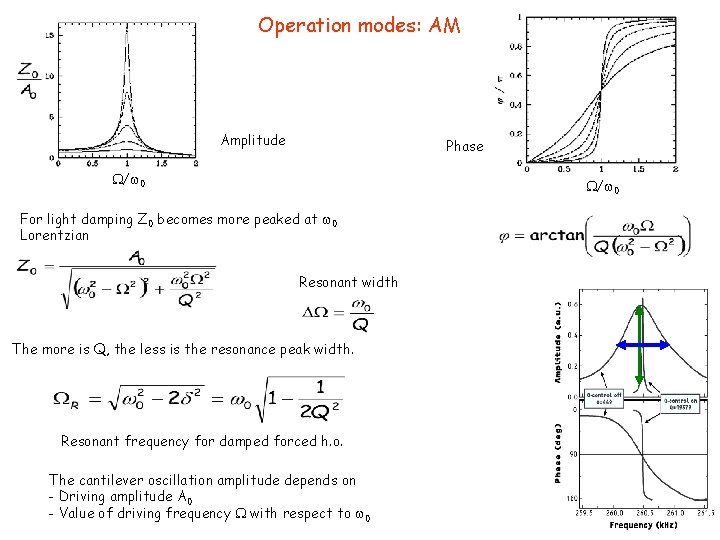

Operation modes: AM Amplitude Phase / 0 For light damping Z 0 becomes more peaked at 0 Lorentzian Resonant width The more is Q, the less is the resonance peak width. Resonant frequency for damped forced h. o. The cantilever oscillation amplitude depends on - Driving amplitude A 0 - Value of driving frequency with respect to 0

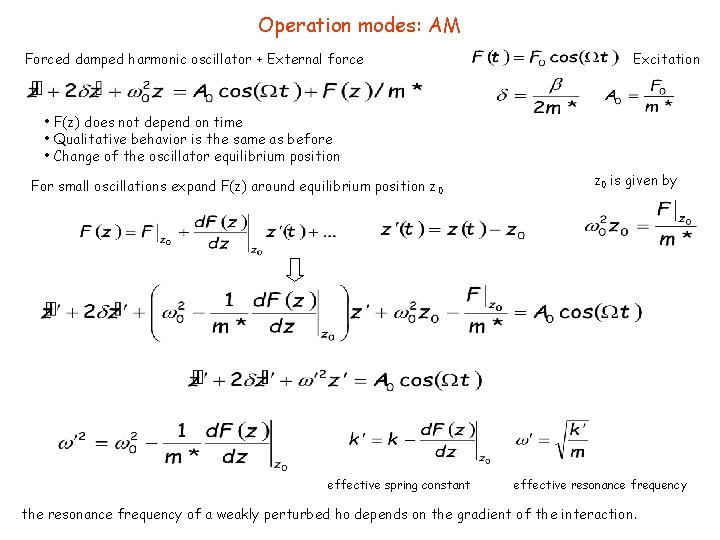

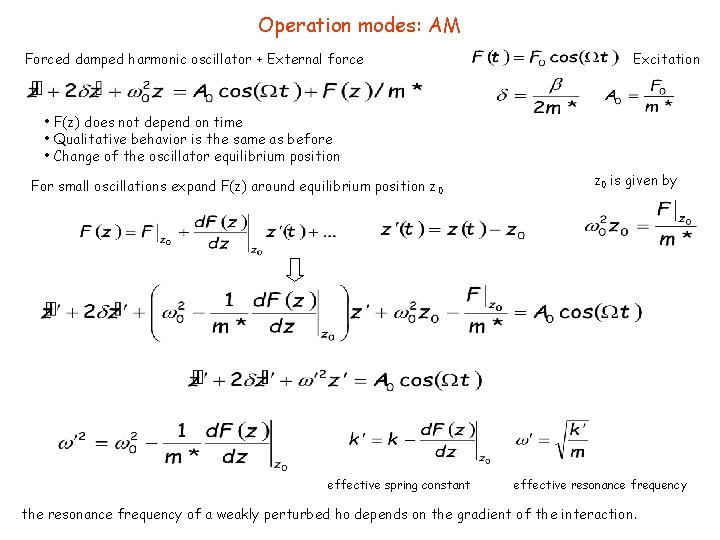

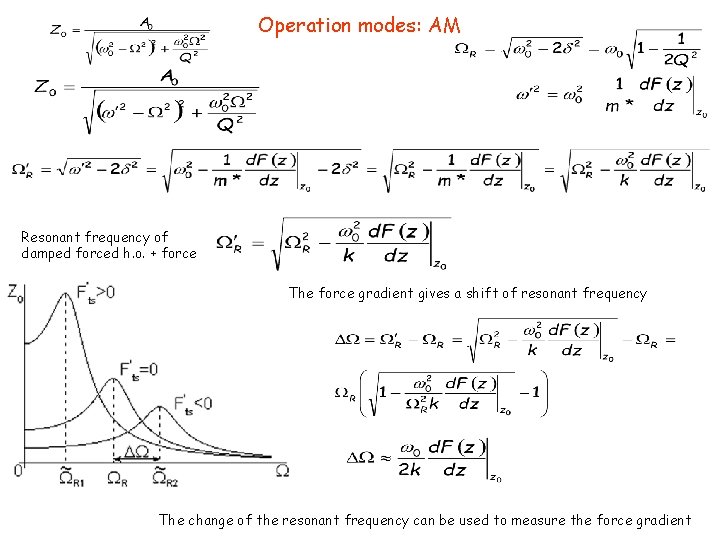

Operation modes: AM Forced damped harmonic oscillator + External force Excitation • F(z) does not depend on time • Qualitative behavior is the same as before • Change of the oscillator equilibrium position For small oscillations expand F(z) around equilibrium position z 0 effective spring constant z 0 is given by effective resonance frequency the resonance frequency of a weakly perturbed ho depends on the gradient of the interaction.

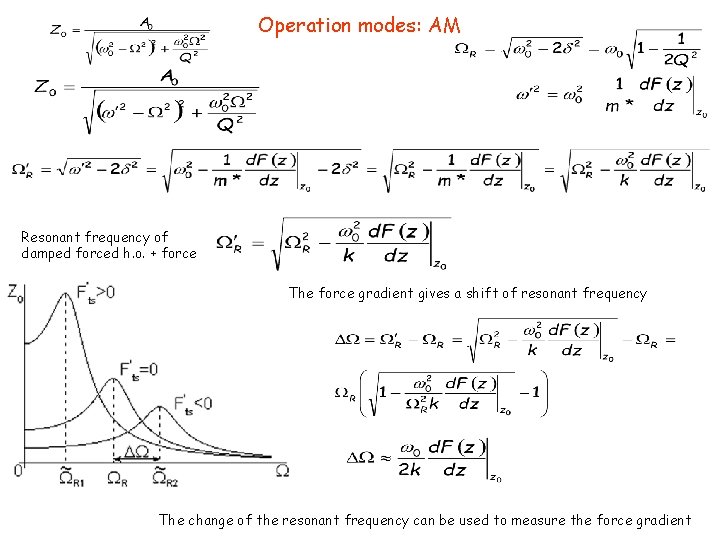

Operation modes: AM Resonant frequency of damped forced h. o. + force The force gradient gives a shift of resonant frequency The change of the resonant frequency can be used to measure the force gradient

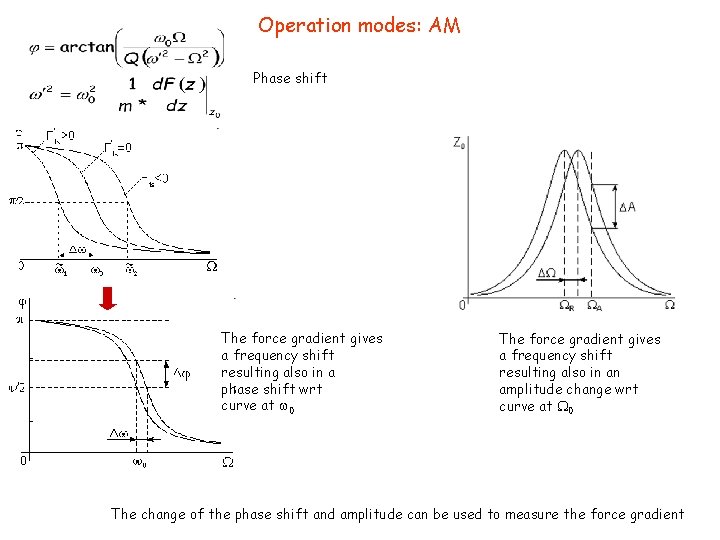

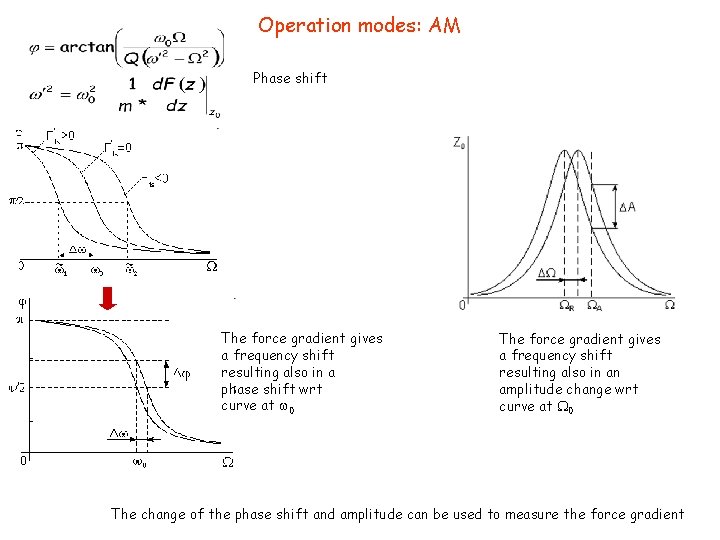

Operation modes: AM Phase shift The force gradient gives a frequency shift resulting also in a phase shift wrt curve at 0 The force gradient gives a frequency shift resulting also in an amplitude change wrt curve at 0 The change of the phase shift and amplitude can be used to measure the force gradient

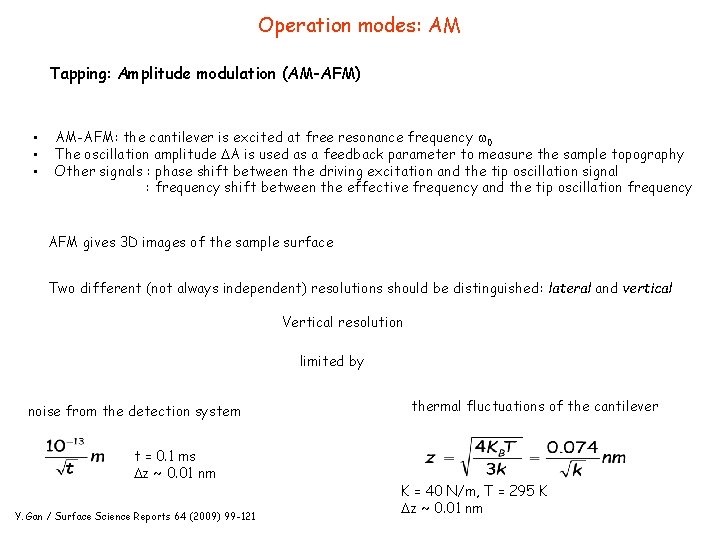

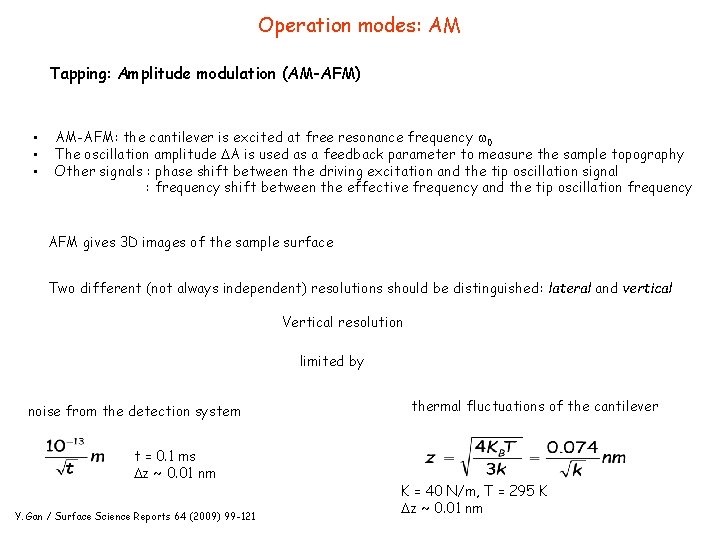

Operation modes: AM Tapping: Amplitude modulation (AM-AFM) • • • AM-AFM: the cantilever is excited at free resonance frequency 0 The oscillation amplitude A is used as a feedback parameter to measure the sample topography Other signals : phase shift between the driving excitation and the tip oscillation signal : frequency shift between the effective frequency and the tip oscillation frequency AFM gives 3 D images of the sample surface Two different (not always independent) resolutions should be distinguished: lateral and vertical Vertical resolution limited by noise from the detection system t = 0. 1 ms z ~ 0. 01 nm Y. Gan / Surface Science Reports 64 (2009) 99 -121 thermal fluctuations of the cantilever K = 40 N/m, T = 295 K z ~ 0. 01 nm

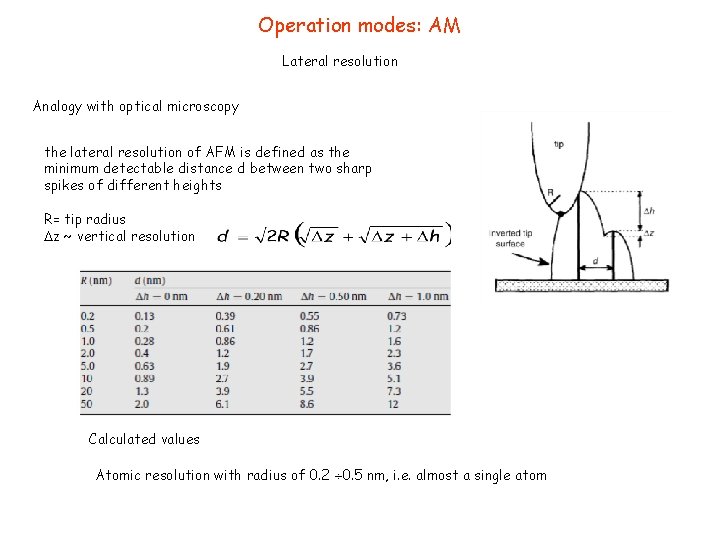

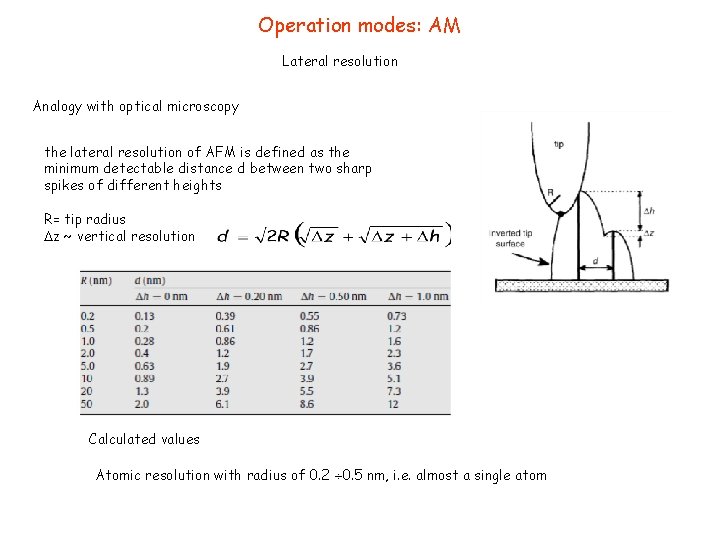

Operation modes: AM Lateral resolution Analogy with optical microscopy the lateral resolution of AFM is defined as the minimum detectable distance d between two sharp spikes of different heights R= tip radius z ~ vertical resolution Calculated values Atomic resolution with radius of 0. 2 0. 5 nm, i. e. almost a single atom

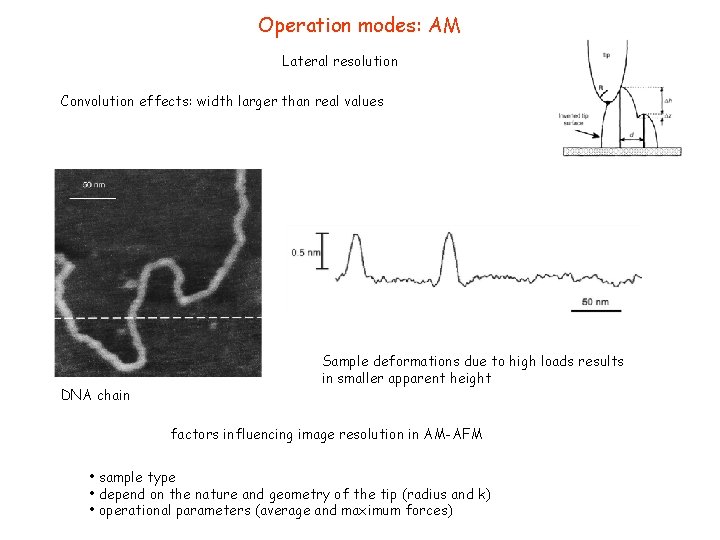

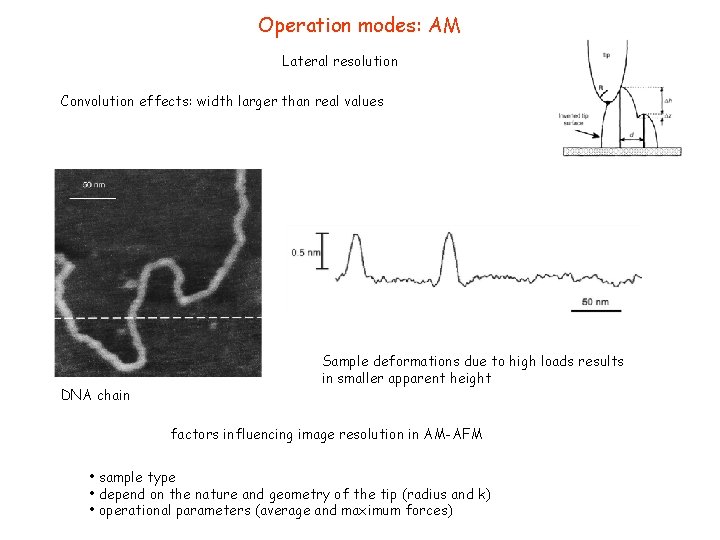

Operation modes: AM Lateral resolution Convolution effects: width larger than real values DNA chain Sample deformations due to high loads results in smaller apparent height factors influencing image resolution in AM-AFM • sample type • depend on the nature and geometry of the tip (radius and k) • operational parameters (average and maximum forces)

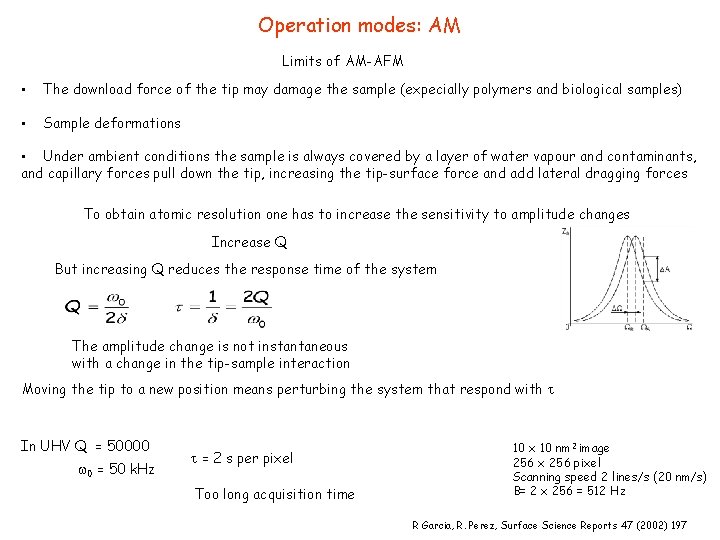

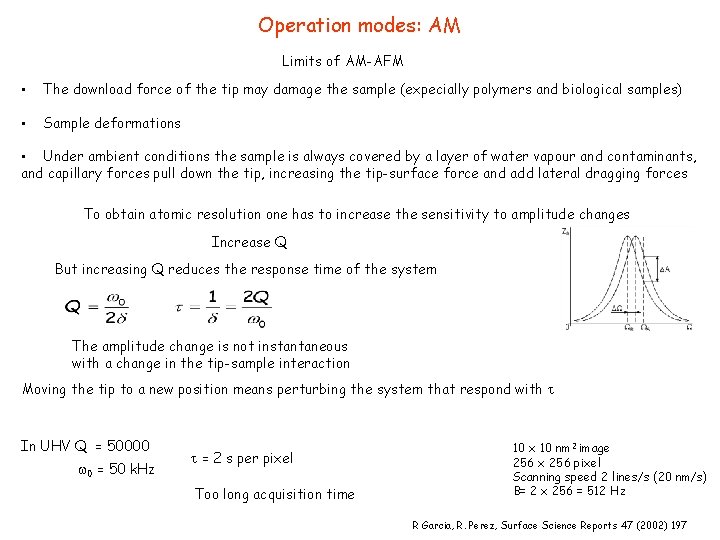

Operation modes: AM Limits of AM-AFM • The download force of the tip may damage the sample (expecially polymers and biological samples) • Sample deformations • Under ambient conditions the sample is always covered by a layer of water vapour and contaminants, and capillary forces pull down the tip, increasing the tip-surface force and add lateral dragging forces To obtain atomic resolution one has to increase the sensitivity to amplitude changes Increase Q But increasing Q reduces the response time of the system The amplitude change is not instantaneous with a change in the tip-sample interaction Moving the tip to a new position means perturbing the system that respond with In UHV Q = 50000 0 = 50 k. Hz = 2 s per pixel Too long acquisition time 10 x 10 nm 2 image 256 x 256 pixel Scanning speed 2 lines/s (20 nm/s) B= 2 x 256 = 512 Hz R Garcia, R. Perez, Surface Science Reports 47 (2002) 197

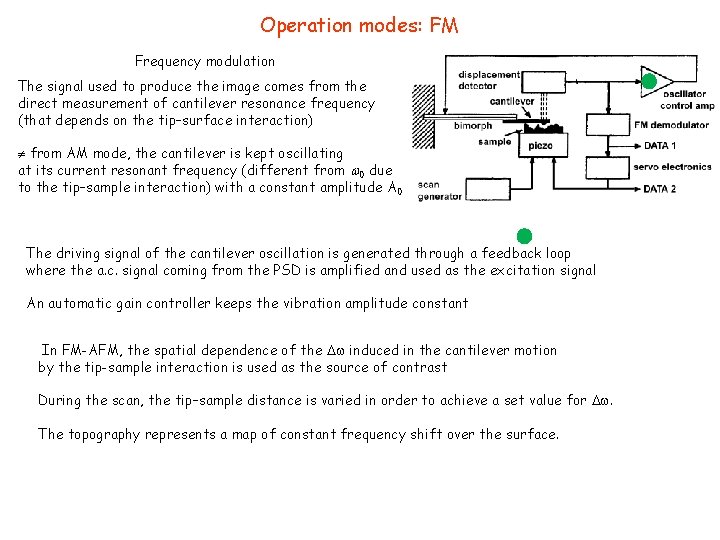

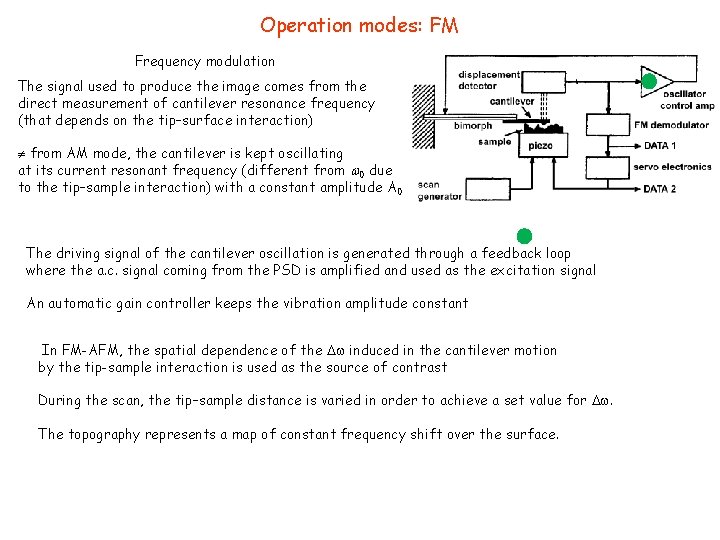

Operation modes: FM Frequency modulation The signal used to produce the image comes from the direct measurement of cantilever resonance frequency (that depends on the tip–surface interaction) from AM mode, the cantilever is kept oscillating at its current resonant frequency (different from 0 due to the tip–sample interaction) with a constant amplitude A 0 The driving signal of the cantilever oscillation is generated through a feedback loop where the a. c. signal coming from the PSD is amplified and used as the excitation signal An automatic gain controller keeps the vibration amplitude constant In FM-AFM, the spatial dependence of the induced in the cantilever motion by the tip-sample interaction is used as the source of contrast During the scan, the tip–sample distance is varied in order to achieve a set value for . The topography represents a map of constant frequency shift over the surface.

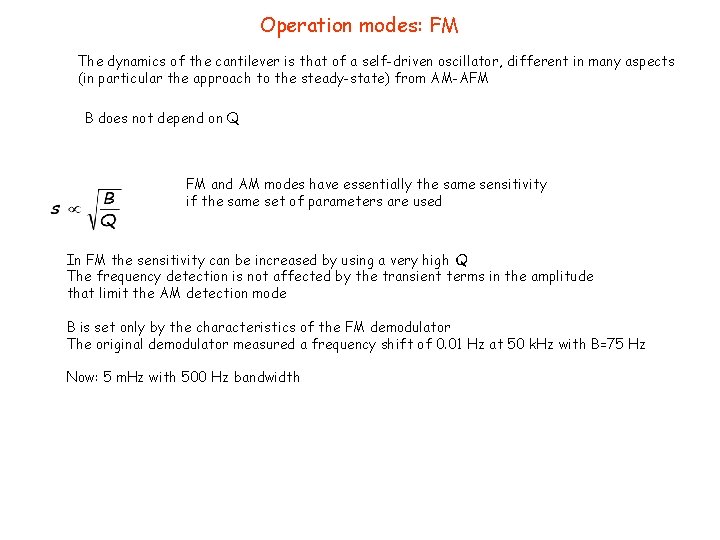

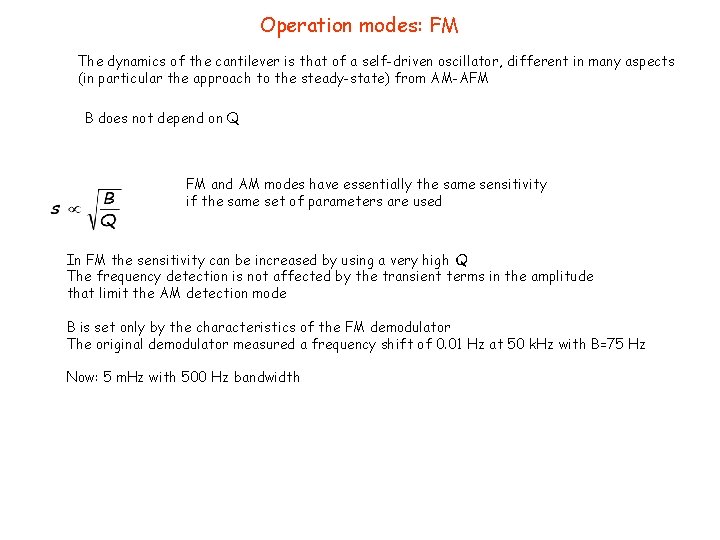

Operation modes: FM The dynamics of the cantilever is that of a self-driven oscillator, different in many aspects (in particular the approach to the steady-state) from AM-AFM B does not depend on Q FM and AM modes have essentially the same sensitivity if the same set of parameters are used In FM the sensitivity can be increased by using a very high Q The frequency detection is not affected by the transient terms in the amplitude that limit the AM detection mode B is set only by the characteristics of the FM demodulator The original demodulator measured a frequency shift of 0. 01 Hz at 50 k. Hz with B=75 Hz Now: 5 m. Hz with 500 Hz bandwidth

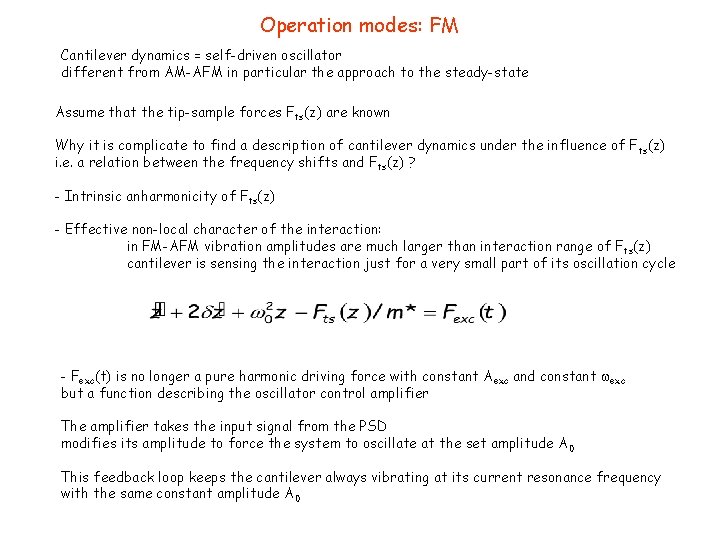

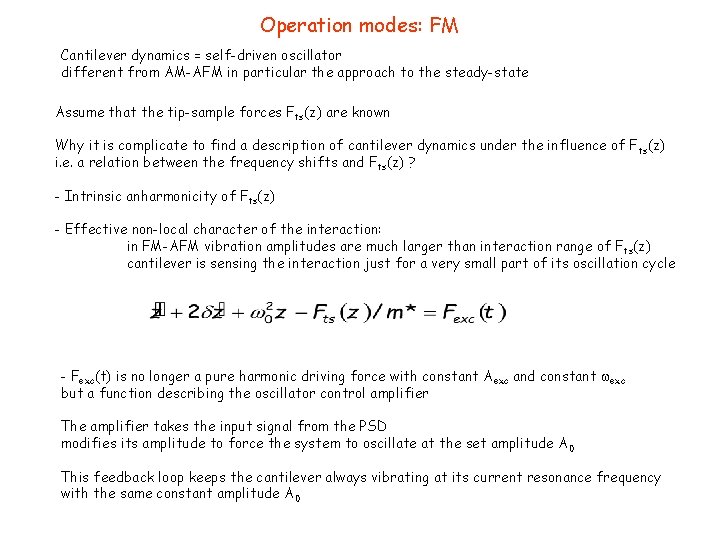

Operation modes: FM Cantilever dynamics = self-driven oscillator different from AM-AFM in particular the approach to the steady-state Assume that the tip-sample forces Fts(z) are known Why it is complicate to find a description of cantilever dynamics under the influence of F ts(z) i. e. a relation between the frequency shifts and Fts(z) ? - Intrinsic anharmonicity of Fts(z) - Effective non-local character of the interaction: in FM-AFM vibration amplitudes are much larger than interaction range of F ts(z) cantilever is sensing the interaction just for a very small part of its oscillation cycle - Fexc(t) is no longer a pure harmonic driving force with constant A exc and constant exc but a function describing the oscillator control amplifier The amplifier takes the input signal from the PSD modifies its amplitude to force the system to oscillate at the set amplitude A 0 This feedback loop keeps the cantilever always vibrating at its current resonance frequency with the same constant amplitude A 0

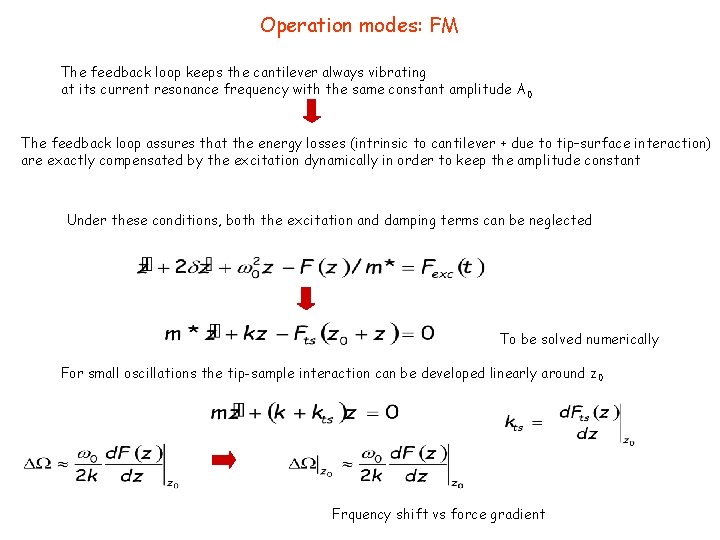

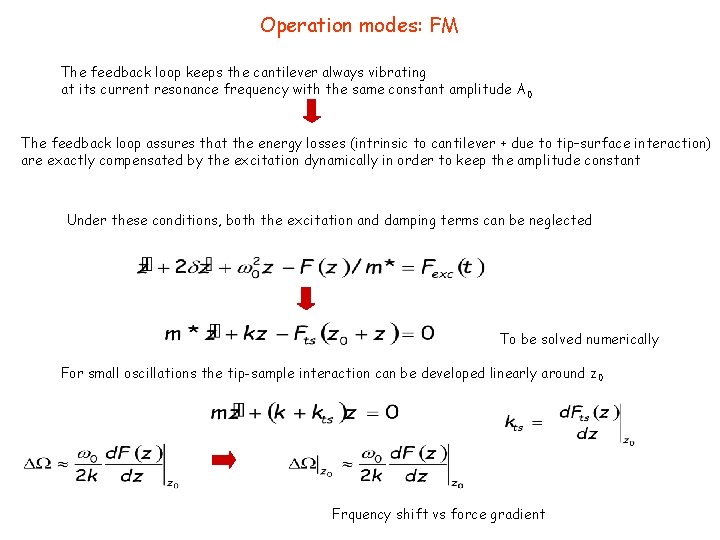

Operation modes: FM The feedback loop keeps the cantilever always vibrating at its current resonance frequency with the same constant amplitude A 0 The feedback loop assures that the energy losses (intrinsic to cantilever + due to tip–surface interaction) are exactly compensated by the excitation dynamically in order to keep the amplitude constant Under these conditions, both the excitation and damping terms can be neglected To be solved numerically For small oscillations the tip-sample interaction can be developed linearly around z 0 Frquency shift vs force gradient

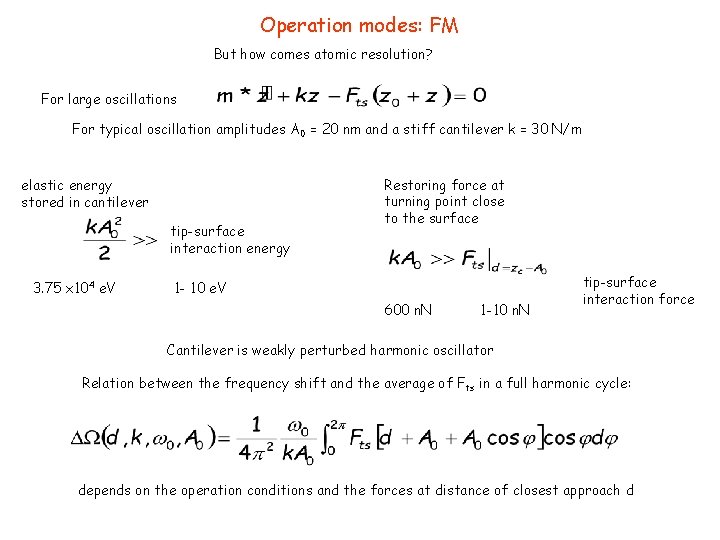

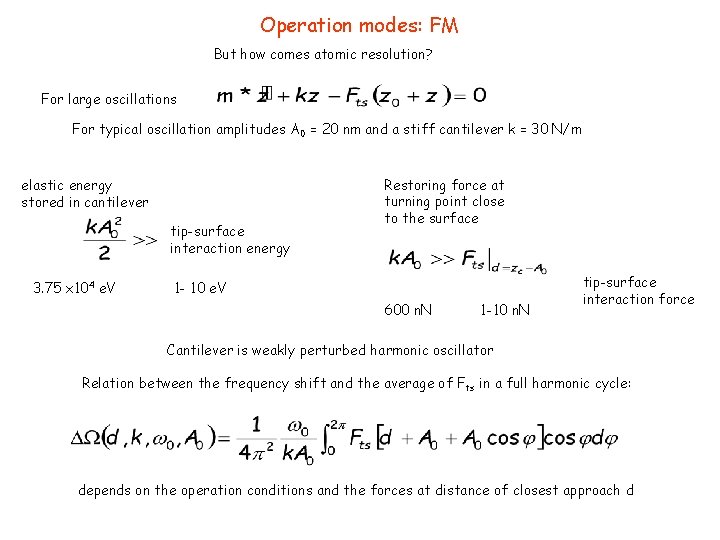

Operation modes: FM But how comes atomic resolution? For large oscillations For typical oscillation amplitudes A 0 = 20 nm and a stiff cantilever k = 30 N/m elastic energy stored in cantilever tip-surface interaction energy 3. 75 x 104 e. V Restoring force at turning point close to the surface 1 - 10 e. V 600 n. N 1 -10 n. N tip-surface interaction force Cantilever is weakly perturbed harmonic oscillator Relation between the frequency shift and the average of F ts in a full harmonic cycle: depends on the operation conditions and the forces at distance of closest approach d

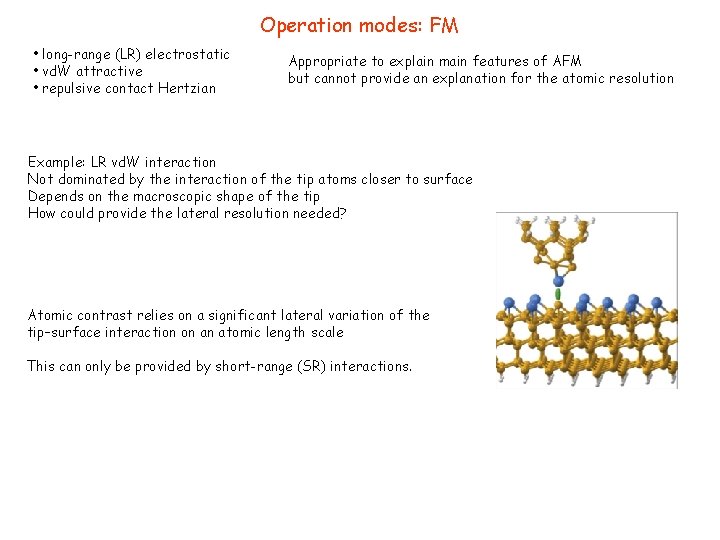

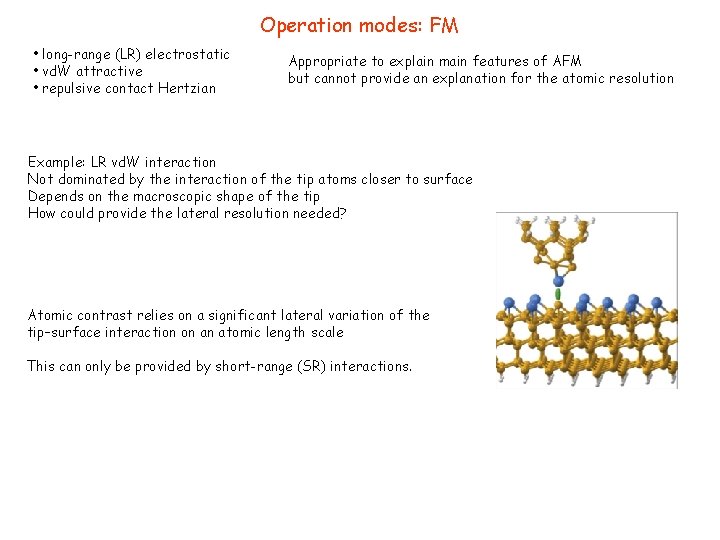

Operation modes: FM • long-range (LR) electrostatic • vd. W attractive • repulsive contact Hertzian Appropriate to explain main features of AFM but cannot provide an explanation for the atomic resolution Example: LR vd. W interaction Not dominated by the interaction of the tip atoms closer to surface Depends on the macroscopic shape of the tip How could provide the lateral resolution needed? Atomic contrast relies on a significant lateral variation of the tip–surface interaction on an atomic length scale This can only be provided by short-range (SR) interactions.

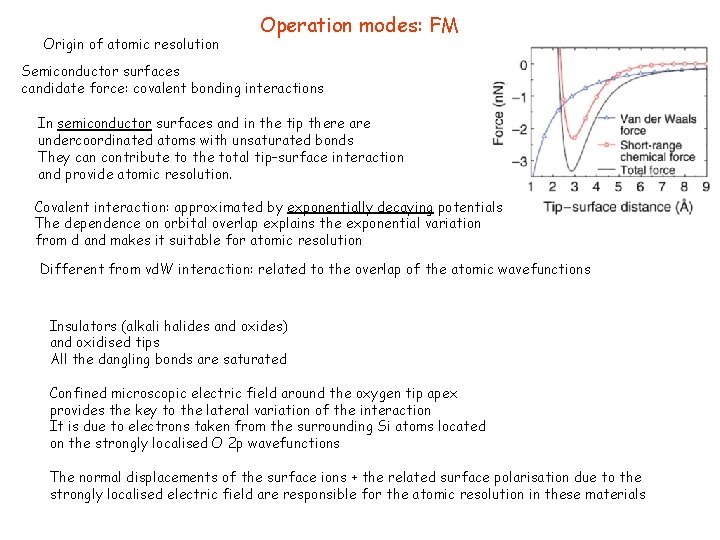

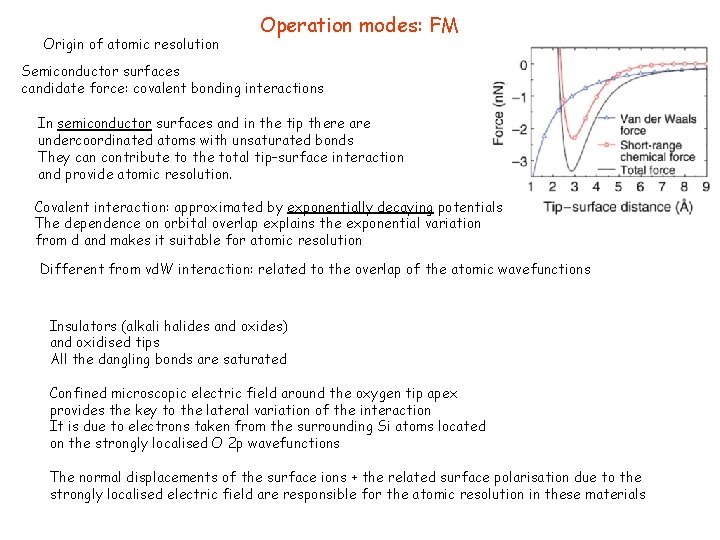

Origin of atomic resolution Operation modes: FM Semiconductor surfaces candidate force: covalent bonding interactions In semiconductor surfaces and in the tip there are undercoordinated atoms with unsaturated bonds They can contribute to the total tip–surface interaction and provide atomic resolution. Covalent interaction: approximated by exponentially decaying potentials The dependence on orbital overlap explains the exponential variation from d and makes it suitable for atomic resolution Different from vd. W interaction: related to the overlap of the atomic wavefunctions Insulators (alkali halides and oxides) and oxidised tips All the dangling bonds are saturated Confined microscopic electric field around the oxygen tip apex provides the key to the lateral variation of the interaction It is due to electrons taken from the surrounding Si atoms located on the strongly localised O 2 p wavefunctions The normal displacements of the surface ions + the related surface polarisation due to the strongly localised electric field are responsible for the atomic resolution in these materials

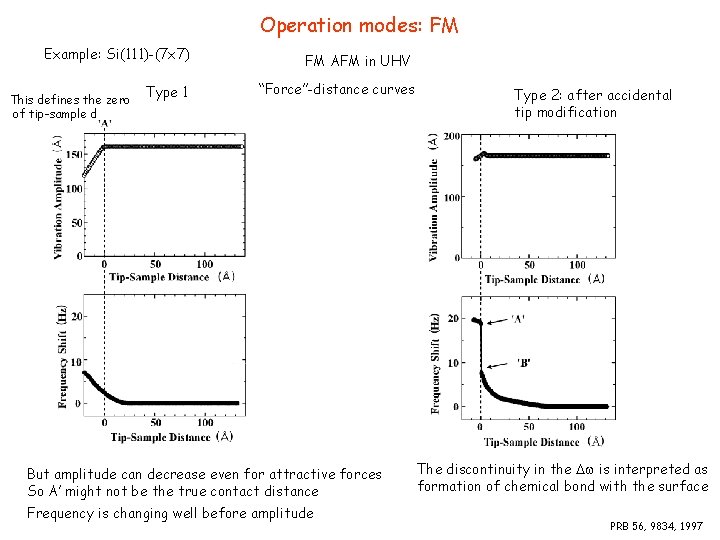

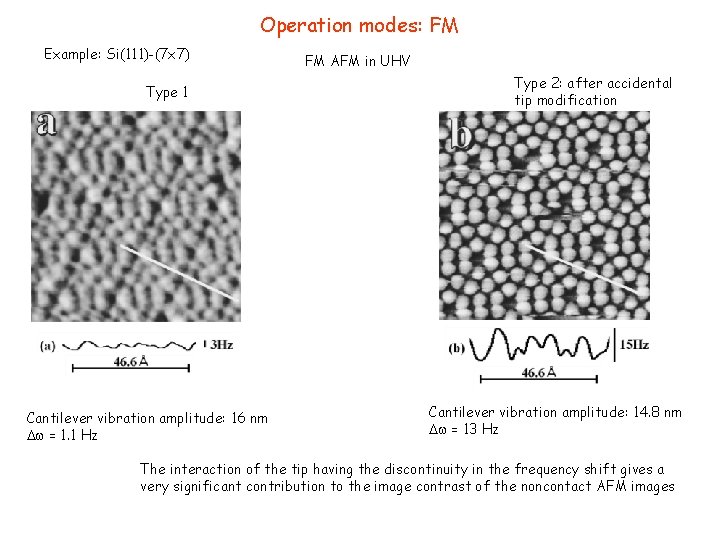

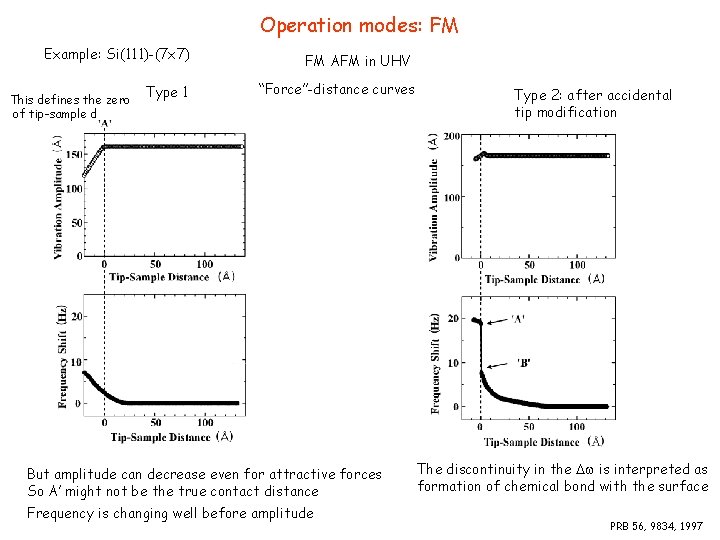

Operation modes: FM Example: Si(111)-(7 x 7) This defines the zero of tip-sample d Type 1 FM AFM in UHV “Force”-distance curves But amplitude can decrease even for attractive forces So A’ might not be the true contact distance Frequency is changing well before amplitude Type 2: after accidental tip modification The discontinuity in the is interpreted as formation of chemical bond with the surface PRB 56, 9834, 1997

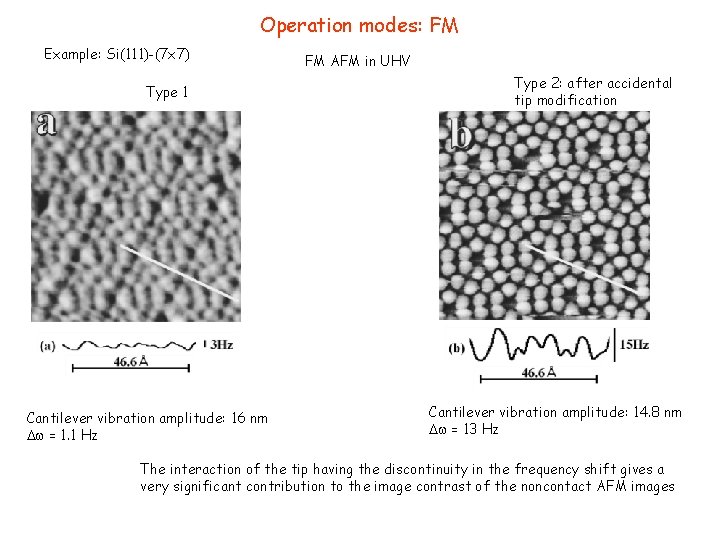

Operation modes: FM Example: Si(111)-(7 x 7) Type 1 Cantilever vibration amplitude: 16 nm = 1. 1 Hz FM AFM in UHV Type 2: after accidental tip modification Cantilever vibration amplitude: 14. 8 nm = 13 Hz The interaction of the tip having the discontinuity in the frequency shift gives a very significant contribution to the image contrast of the noncontact AFM images

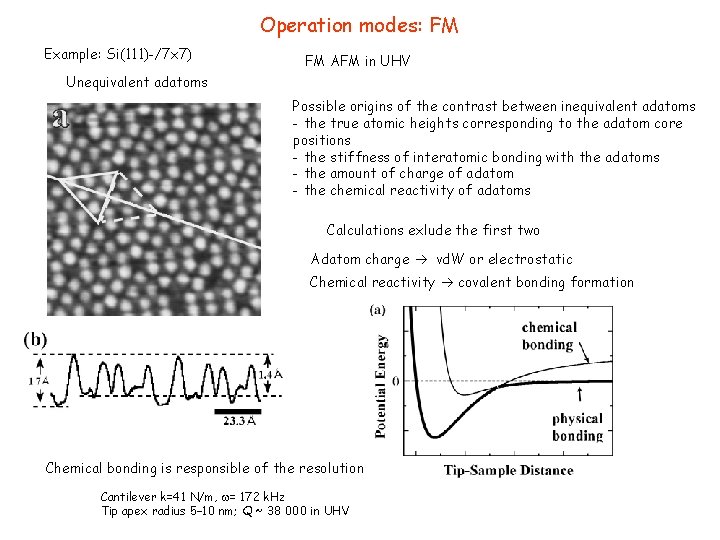

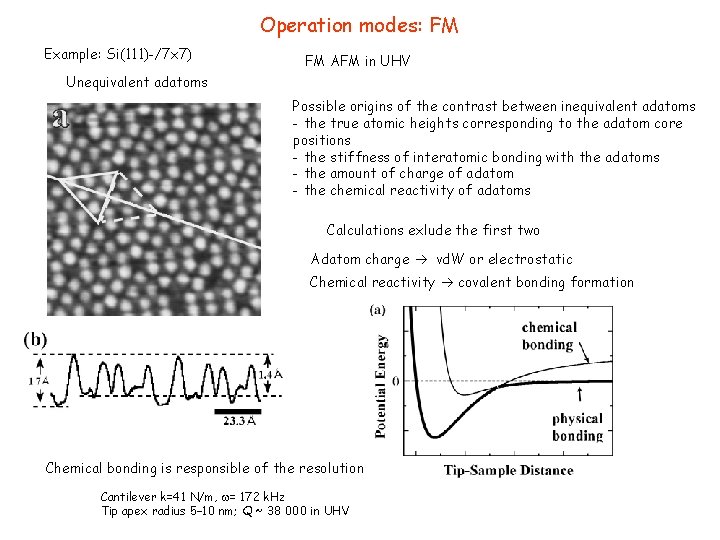

Operation modes: FM Example: Si(111)-/7 x 7) FM AFM in UHV Unequivalent adatoms Possible origins of the contrast between inequivalent adatoms - the true atomic heights corresponding to the adatom core positions - the stiffness of interatomic bonding with the adatoms - the amount of charge of adatom - the chemical reactivity of adatoms Calculations exlude the first two Adatom charge vd. W or electrostatic Chemical reactivity covalent bonding formation Chemical bonding is responsible of the resolution Cantilever k=41 N/m, = 172 k. Hz Tip apex radius 5– 10 nm; Q ~ 38 000 in UHV