Assessing Coordination of the Limbs For distribution n

Assessing Coordination of the Limbs For distribution

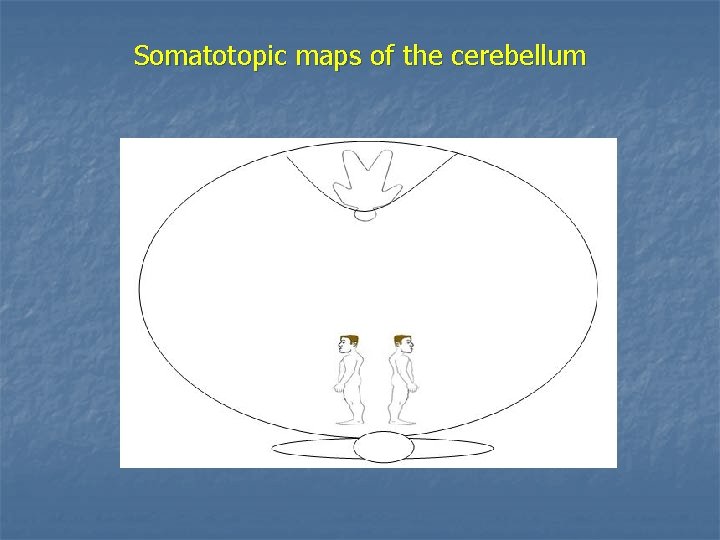

n n The medial portion of the cerebellum is concerned with motor control of the medial musculature (trunk & spine), and the more lateral portions of the cerebellum are concerned with motor control of the limb. Of course, the ability to provide truncal stability, as changing forces act upon the trunk during limb movement, would be necessary for limb coordination to be normal when non-recumbent.

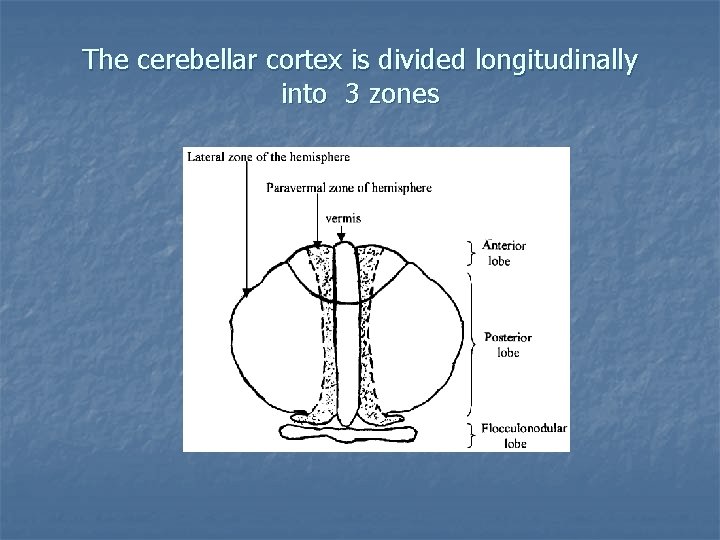

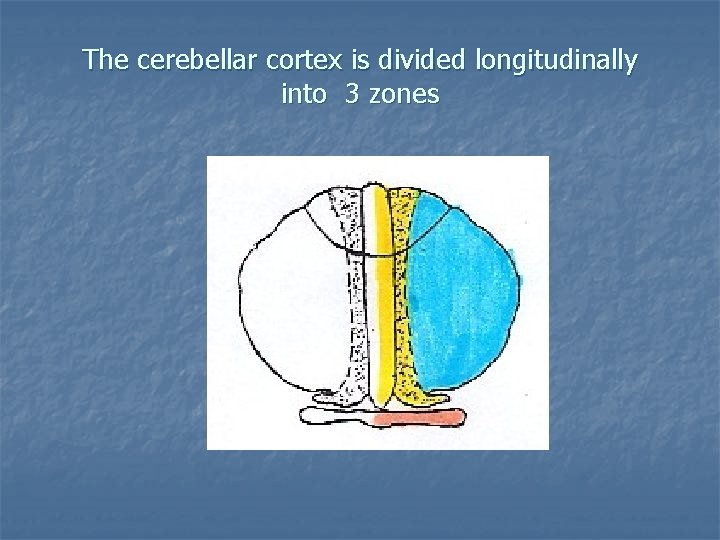

The cerebellar cortex is divided longitudinally into 3 zones

The cerebellar cortex is divided longitudinally into 3 zones

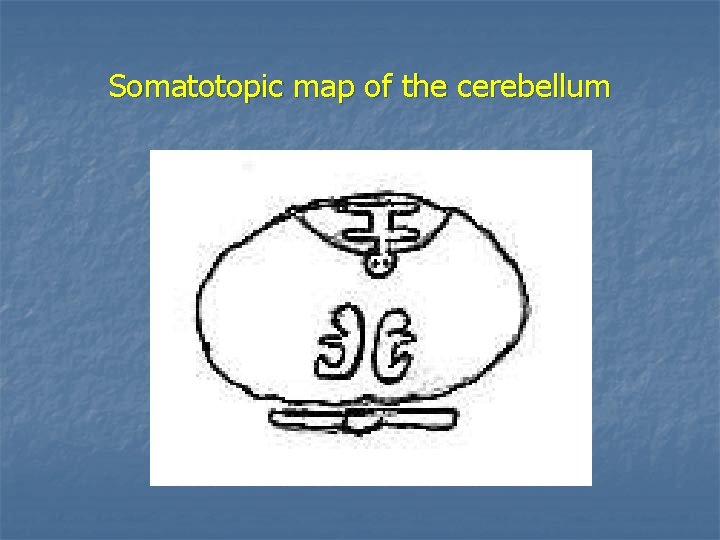

Somatotopic map of the cerebellum

Somatotopic maps of the cerebellum

Assessing Coordination of the Limbs (limb ataxia) When assessing cerebellar function, in addition to assessing station and gait, coordination of the limbs must be assessed. Coordination of the limbs is related to the intermediate (paravermal) zone of the spinocerebellum. (The lateral zone will also be involved, as it relates to the “planning” of movement. )

When limb coordination tests are performed in the standing position, the medial (vermal) zone will be challenged as truncal stability will need to constantly be adjusted to compensate for the limb movement. Increased swaying, or truncal ataxia (“titubation”), may indicate dysfunction of the medial (vermal) zone of the spinocerebellum.

“ataxia” Loss of smoothness or accuracy of the movement is called “ataxia” (Gk. , lack of order). More specific names may be used depending upon the type of test that is abnormal.

Types of limb coordination tests Limb coordination testing consists of: • Point-to-point tests • Rapid alternating movement tests.

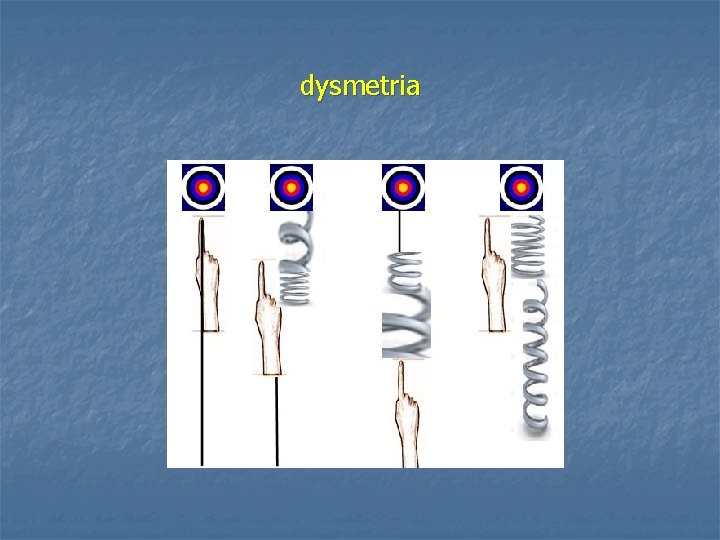

Point-to-point tests These tests involve observing movement of a limb from one point to another point ( ex. patient touches their finger to their nose), and noting the smoothness and accuracy of the movement. Alteration of the smoothness &/or accuracy of the movement is called “dysmetria” (Gk. , dys + metron measure). A tremor may be noted as the target is neared (“intention” tremor or “terminal” tremor).

“dysmetria” (Gk dys + metron measure) The moving body part may overshoot the target, or hit the target too hard (“over-shooting”, “past-pointing”, or “hypermetria”. ) The moving body part may stop prior to reaching the target, and hesitate before continuing on to the target (“under-shooting” or “hypometria”).

Commonly performed point-to-point tests 1. Finger-to-nose test Ask the patient to alternately touch the index finger of each hand to the tip of their nose. Observe the smoothness and accuracy of the movement. Note any “dysmetria”, or “intention” tremor.

Point-to-point tests 2. Finger-to-finger-to-nose test Ask the patient to touch their nose and then reach out to touch the examiner’s finger (positioned such that the patient must almost fully extend). Repeat several times with your finger in different locations. Note any “dysmetria” or “intention” tremor.

dysmetria

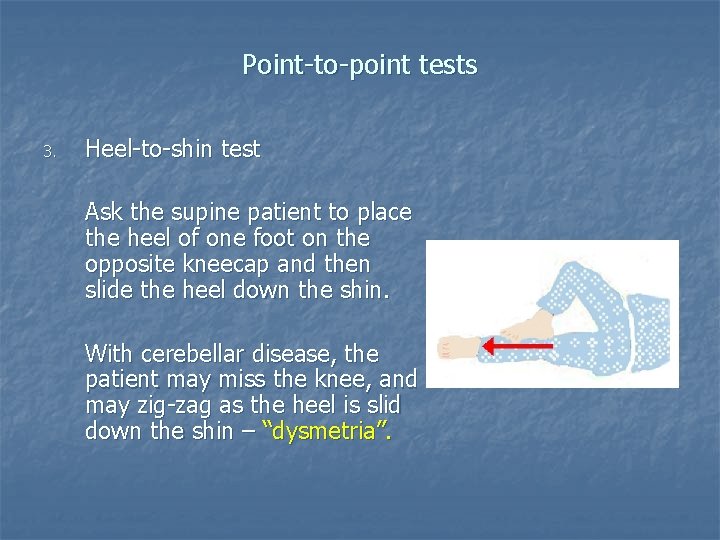

Point-to-point tests 3. Heel-to-shin test Ask the supine patient to place the heel of one foot on the opposite kneecap and then slide the heel down the shin. With cerebellar disease, the patient may miss the knee, and may zig-zag as the heel is slid down the shin – “dysmetria”.

Point-to-point tests 4. Toe-to-finger test The supine patient is asked to reach and touch the examiner’s finger with their big toe. Repeat several times with your finger in different locations. Note any “dysmetria” or “intention” tremor.

Point-to-point tests with eyes closed When point-to-point tests are performed with the eyes closed, the patient will need to rely more on their joint position sense or conscious proprioception. If performance is significantly worse with the eyes closed compared to with the eyes open, a deficit related to joint position sense may be present.

classic vs. contemporary interpretation overshooting/hypermetria vs. undershooting/hypometria Classically, any type of dysmetria is interpreted as indicative of cerebellar dysfunction ipsilateral to the side of the involved limbs. Contemporary interpretation suggests that overshooting or hypermetria may be more characteristically associated with cerebellar dysfunction, while hypometria may be associated with dysfunction of the parietal lobe contralaterally (impaired proprioception/joint position sense).

Rapid alternating movement tests (dysdiadochokinesis) Observe the smoothness, rhythm, and speed of rapid alternating movements. With cerebellar dysfunction, the patient can not perform alternating movements smoothly and/or quickly. The movements are clumsy, irregular, and slow. This abnormality is called “dysdiadochokinesis” (dys + diadochos, succeeding + kinesis , movement).

Rapid alternating movement tests In the upper extremity, you can check: 1. Tapping index finger to thumb (IP joint) 2. Patting the thigh 3. Pronation-supination (alternately pat the thigh with the palm and dorsum or the hand)

Rapid alternating movement tests In the lower extremity: 1. Ask the patient to tap your hand as quickly as possible with the ball of their foot. 2. Ask the patient to tap the knee several times with the alternate heel. This can be combined with the heel-toshin test.

Holmes’ rebound test Essentially a test of rapid alternating contractions. Ask the patient to flex their forearm against the examiner’s resistance (turn patient’s face away and shield with your other hand. ) Suddenly remove your pressure. Normally, the patient can quickly check the movement of the forearm. With CB dysfunction, however, there is failure of the antagonists to contract and agonists to relax, and the forearm continues to swing upward.

Other abnormalities associated with cerebellar dysfunction 5. Gait ataxia Truncal ataxia (“titubation”) Hypotonia Pendular DTRs (excessive swinging) Speech dysarthria 6. Cognitive-affective syndrome 7. Ocular dysmetria (flocculonodular lobe & vermis) 8. Autonomic dysfunction (connections to the HT have been identified). 1. 2. 3. 4.

Causes of cerebellar dysfunction 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. subluxation-mediated (dysafferentation) cerebellar diaschisis Trauma Alcohol intoxication Chronic alcohol abuse (anterior lobe syndrome) Multiple sclerosis (demyelination) CVA (vertebrobasilar circulation) Tumors (CB most common site of 10 brain tumors in children)

Cerebellar diseases: anterior lobe syndrome § § Associated with long-term alcohol abuse Primarily affects gait and lower extremity coordination

Eye movements & cerebellar function The flocculonodular lobe and vermis are phylogenetically older and less well developed, they are often compromised before the newer more lateral regions. Since the flocculonodular lobe and parts of the vermis are very involved in eye movements, assessment of these regions requires detailed assessment of eye movement. Performance of the standard tests of balance and limb coordination may not reveal these deficits.

- Slides: 27