ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS ANALYSIS Basics on blood chemistry

ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS ANALYSIS Basics on blood chemistry and ABG/VBG interpretation. Luke Heath

The basics � � � Always remove any air gap and cap the syringe after taking the blood. Invert the syringe to mix the blood with the heparin. Process the sample within 10 minutes and invert regularly while waiting. Add all requested information including Fi. O 2, as many values are calculated. Venous gasses have differing respiratory readings from arterial.

Cellular Respiration C 6 H 12 O 6 (Glucose) + 6 O 2 (Oxygen) = 6 CO 2 (Carbon Dioxide) + 6 H 20 (Water) + Energy (ADP to ATP) Every living cell is performing the above process, and will die very quickly without oxygen. Blood must transport oxygen and glucose to all cells and remove the carbon dioxide from them. Blood is the lifeline for every cell in the body.

The Fundamentals of blood chemistry. 1. 2. 3. 4. Acidity is related to free hydrogen ions in solution. Carbon dioxide in solution is acidic. Haemoglobins (Hb) affinity for oxygen is related to acidity. The body must try to maintain homeostasis.

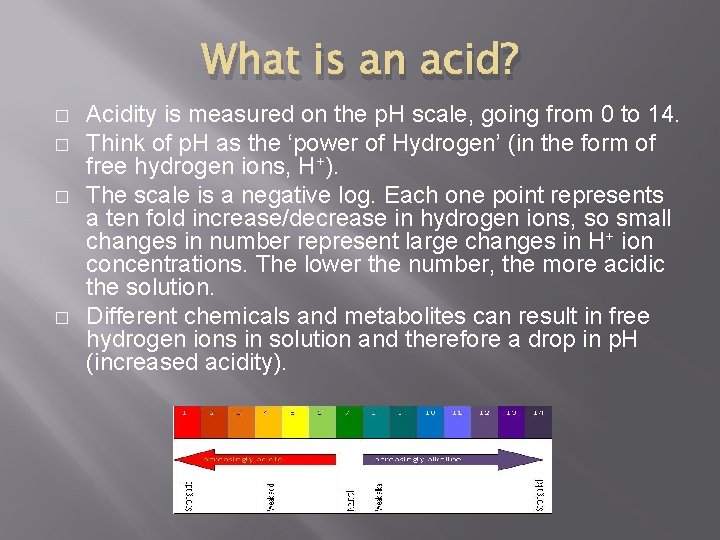

What is an acid? � � Acidity is measured on the p. H scale, going from 0 to 14. Think of p. H as the ‘power of Hydrogen’ (in the form of free hydrogen ions, H+). The scale is a negative log. Each one point represents a ten fold increase/decrease in hydrogen ions, so small changes in number represent large changes in H+ ion concentrations. The lower the number, the more acidic the solution. Different chemicals and metabolites can result in free hydrogen ions in solution and therefore a drop in p. H (increased acidity).

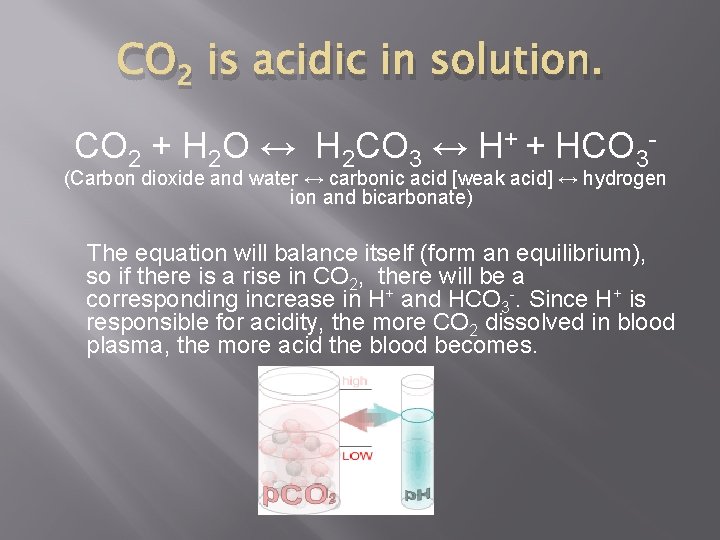

CO 2 is acidic in solution. CO 2 + H 2 O ↔ H 2 CO 3 ↔ H+ + HCO 3 - (Carbon dioxide and water ↔ carbonic acid [weak acid] ↔ hydrogen ion and bicarbonate) The equation will balance itself (form an equilibrium), so if there is a rise in CO 2, there will be a corresponding increase in H+ and HCO 3 -. Since H+ is responsible for acidity, the more CO 2 dissolved in blood plasma, the more acid the blood becomes.

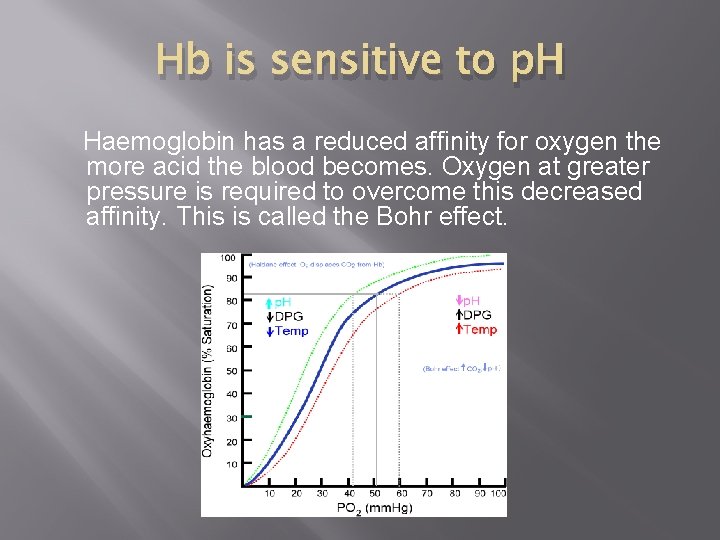

Hb is sensitive to p. H Haemoglobin has a reduced affinity for oxygen the more acid the blood becomes. Oxygen at greater pressure is required to overcome this decreased affinity. This is called the Bohr effect.

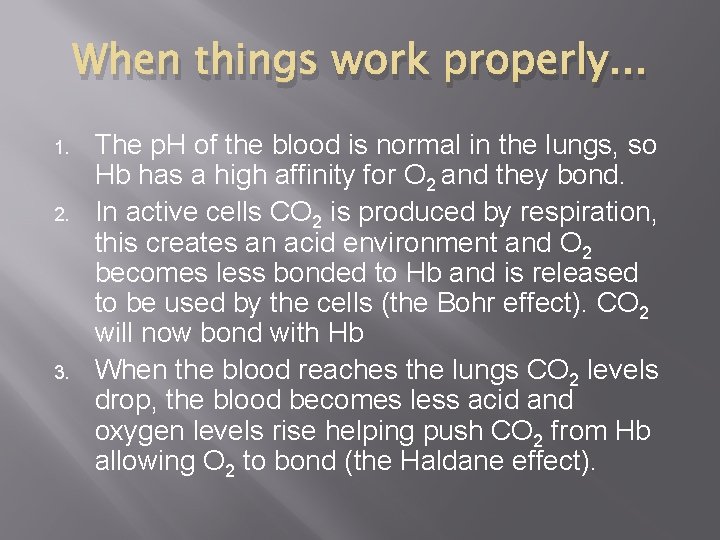

When things work properly. . . 1. 2. 3. The p. H of the blood is normal in the lungs, so Hb has a high affinity for O 2 and they bond. In active cells CO 2 is produced by respiration, this creates an acid environment and O 2 becomes less bonded to Hb and is released to be used by the cells (the Bohr effect). CO 2 will now bond with Hb When the blood reaches the lungs CO 2 levels drop, the blood becomes less acid and oxygen levels rise helping push CO 2 from Hb allowing O 2 to bond (the Haldane effect).

Blood p. H control - Ventilation � � The body has two methods of controlling blood p. H. Firstly, by controlling ventilation which will in turn control the level of CO 2 in the blood. Respiratory rate is the primary control, but tidal volumes can also increase to help change p. H rapidly. Bicarbonate (HCO 3 -) is called a ‘buffer’, because excess hydrogen ions can combine with it to reduce their effect on p. H. Non-respiratory hydrogen ions can be removed as CO 2 because of it, which is why there is always a store of bicarbonate in the blood.

Blood p. H control – The kidneys � � The second method is via the kidneys, which are able to excrete H+ or HCO 3 - in the urine to adjust p. H. This renal (or metabolic) control takes many hours or days to effect change It will be seen in COPD patients, who will increase their bicarbonate levels to prevent an acid blood despite their raised CO 2 levels. However, ventilation is the primary p. H control, which is why respiratory rate is such an important clinical observation.

Measuring dissolved gasses. � � Oxygen and carbon dioxide are measured in the blood by their partial pressure (sometimes called ‘tension’). The symbol is p. The unit of measurement of this pressure is kilopascal, abbreviated to k. Pa. In normal arterial blood the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is 4. 6 – 6. 4 k. Pa, and for oxygen it is 11 – 14 k. Pa. A venous sample will have a lower oxygen and slightly raised carbon dioxide.

Respiratory Acidosis � � � Blood p. H should be between 7. 35 -7. 45. When ventilation or lung function are compromised, CO 2 levels rise in the blood resulting in a raised p. CO 2 (> 6. 4 k. Pa) and acidic blood (< 7. 35). Small changes in p. H represent substantial changes in hydrogen ion concentrations, so a p. H < 7 is sever acidosis. It indicates that the blood cannot function properly because Hb will have lost its affinity to carry oxygen.

Respiratory Failure Type 1 Hypoxia (low O 2) without hypercapnia (raised CO 2 ). p. O 2 < 8 k. Pa but p. CO 2 normal Type 2 Hypoxia with hypercapnia. p. O 2 < 8 k. Pa with p. CO 2 >7

Bicarbonate � � Bicarbonate (HCO 3 -) is measured in mmol/L (millimole per litre). The normal range is 22 -26 mmol/L. It helps ‘buffer’ hydrogen ions by promoting their transfer into carbonic acid (which is less acidic than hydrogen ions) and then CO 2. Excess bicarbonate can lead to metabolic alkalosis, too little to metabolic acidosis. The base deficit is a calculation of how much bicarbonate would be required to normalise a deficiency, the base excess how much extra has been produced.

Metabolic Acidosis When the p. H is < 7. 35 and the p. CO 2 is not raised the cause of the acidosis will probably be metabolic. Bicarbonate will be reduced (base deficit) as it bonds with H+ to push the equation to the left. This can be from: 1. 2. 3. Lactic acid from non-oxygen respiration due to high metabolic requirements (infection) or hypoxia. Ketoacidosis from fat metabolism in DKA. Kidney failure.

Respiratory Acidosis When the p. H is < 7. 35 and the p. CO 2 is raised the cause of the acidosis will probably be respiratory. PO 2 may be reduced or have been partially corrected with increased Fi. O 2. Bicarbonate will be reduced (base deficit) as it bonds with H+ to push the equation to the left. This can be from: 1. Hypoventilation (CVE, opiate, obstruction) 2. Pulmonary embolism. 3. Chest trauma (mechanical failure)

Metabolic Alkalosis When the p. H is > 7. 45 and the p. CO 2 is not low, then the alkalosis will probably be metabolic in nature. Bicarbonate may be raised (base excess). It can be caused by: 1. 2. 3. Loss of hydrogen ions (vomiting – look at the chloride levels) Excess bicarbonate (chronic hypoventilation) Potassium ion exchange (hypokaleamia response)

Respiratory Alkalosis When a person hyperventilates CO 2 is ‘blown off’ causing blood p. H to rise (become alkaline) resulting in a p. H > 7. 45 and a p. CO 2 < 4. 7 k. Pa. The p. CO 2 is a good indicator of ventilatory effectiveness.

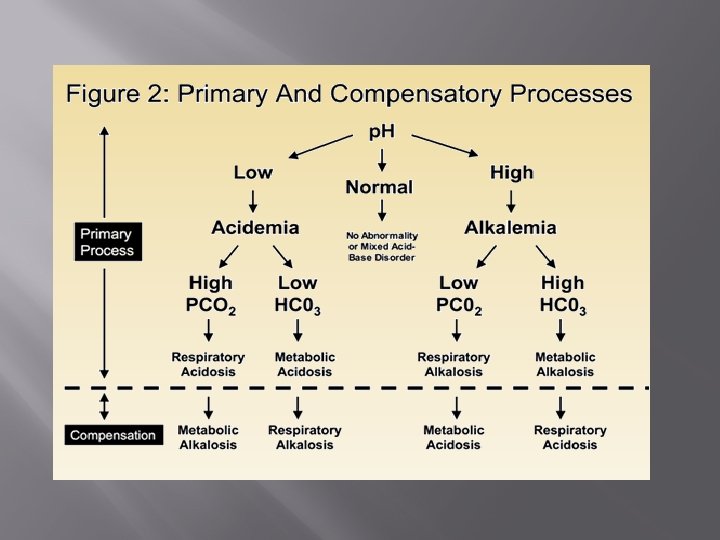

Compensation responses Since there can be controlled and uncontrolled metabolic or respiratory acidosis or alkalosis, it follows that when an uncontrolled system creates an acidosis a controlled system can try and correct it. In chronic conditions the compensation will be marked, in acute ones less so, but some compensation will occur. However, your body never over-compensates.

Respiratory acidosis with metabolic compensation. An example would be someone with COPD. An ABG might indicate: p. H 7. 35 p. CO 2 8. 5 k. Pa p. O 2 9. 3 k. Pa HCO 3 34 mmol/L The p. H is normal, but it shouldn't be because the CO 2 is high. The reason is the raised bicarbonate produced by the kidneys, which promotes carbonic acid formation which is less acidic than free hydrogen ions.

Metabolic acidosis with respiratory compensation. An example would be a septic patient. An ABG might indicate: p. H 7. 30 p. CO 2 2. 4 k. Pa p. O 2 10. 2 k. Pa HCO 3 14. 2 mmol/L The p. H is low, but it shouldn't be because the CO 2 is low (the p. H should be high). The low CO 2 indicates hyperventilation. The reduced bicarbonate shows it has been used to ‘mop up’ excess hydrogen ions to remove them as CO 2.

Respiratory acidosis to compensate for metabolic alkalosis or the other way round? Look at your patient! You will know if they are chronic COPD or have been acutely vomiting. Your body never over-compensates, whatever the direction of the p. H, the process that corresponds with that will be the primary cause, all else will be compensation. Compensation can be partial or fully achieved (ie. p. H will be normal with abnormal numbers)

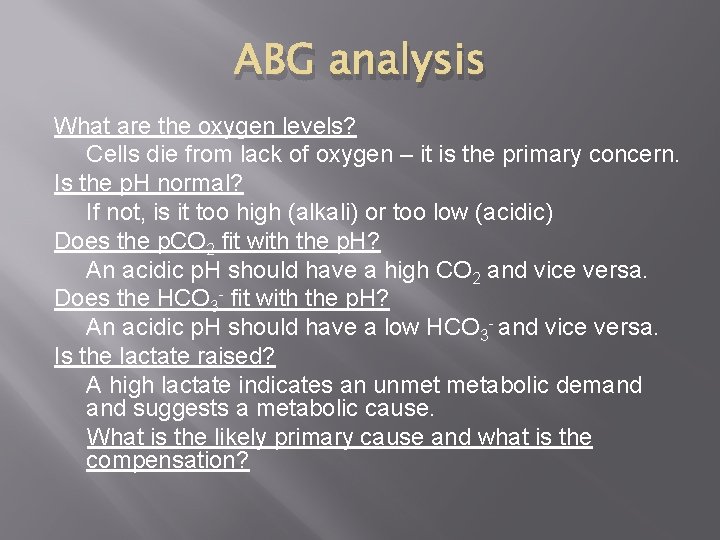

ABG analysis What are the oxygen levels? Cells die from lack of oxygen – it is the primary concern. Is the p. H normal? If not, is it too high (alkali) or too low (acidic) Does the p. CO 2 fit with the p. H? An acidic p. H should have a high CO 2 and vice versa. Does the HCO 3 - fit with the p. H? An acidic p. H should have a low HCO 3 - and vice versa. Is the lactate raised? A high lactate indicates an unmet metabolic demand suggests a metabolic cause. What is the likely primary cause and what is the compensation?

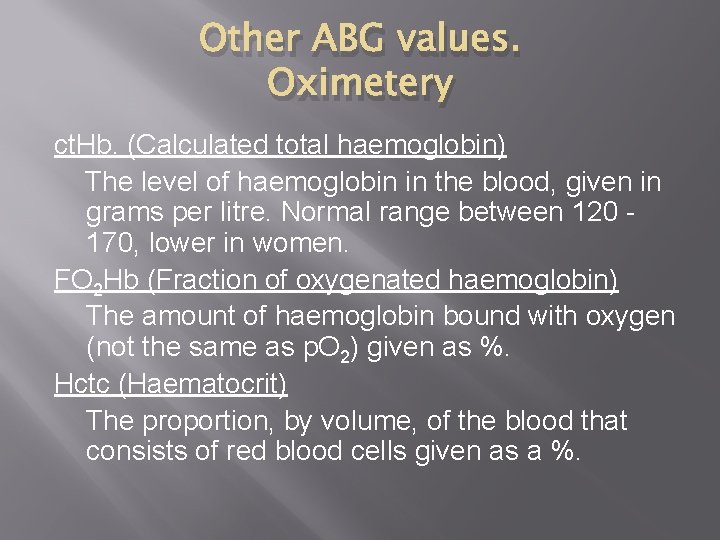

Other ABG values. Oximetery ct. Hb. (Calculated total haemoglobin) The level of haemoglobin in the blood, given in grams per litre. Normal range between 120 170, lower in women. FO 2 Hb (Fraction of oxygenated haemoglobin) The amount of haemoglobin bound with oxygen (not the same as p. O 2) given as %. Hctc (Haematocrit) The proportion, by volume, of the blood that consists of red blood cells given as a %.

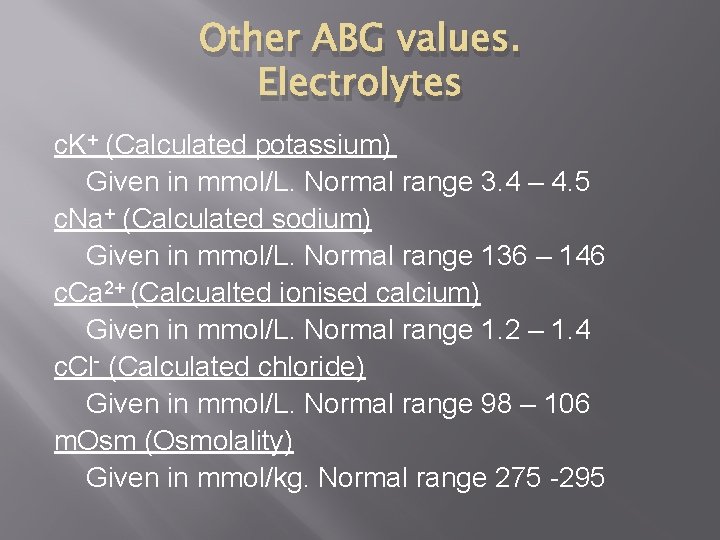

Other ABG values. Electrolytes c. K+ (Calculated potassium) Given in mmol/L. Normal range 3. 4 – 4. 5 c. Na+ (Calculated sodium) Given in mmol/L. Normal range 136 – 146 c. Ca 2+ (Calcualted ionised calcium) Given in mmol/L. Normal range 1. 2 – 1. 4 c. Cl- (Calculated chloride) Given in mmol/L. Normal range 98 – 106 m. Osm (Osmolality) Given in mmol/kg. Normal range 275 -295

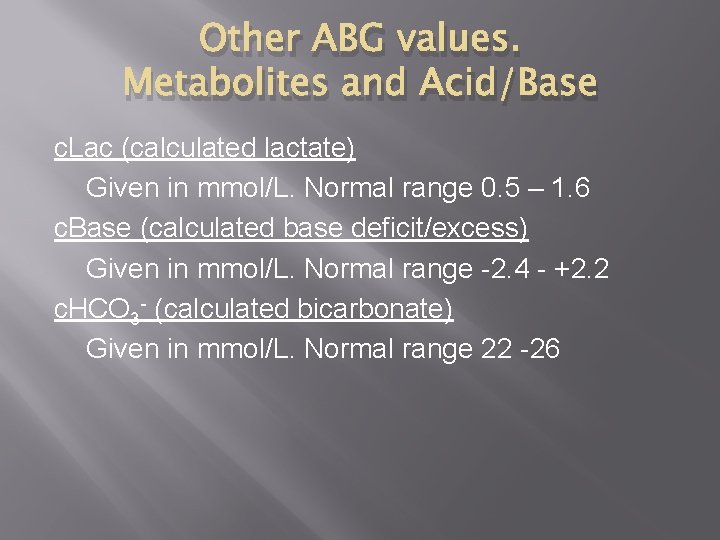

Other ABG values. Metabolites and Acid/Base c. Lac (calculated lactate) Given in mmol/L. Normal range 0. 5 – 1. 6 c. Base (calculated base deficit/excess) Given in mmol/L. Normal range -2. 4 - +2. 2 c. HCO 3 - (calculated bicarbonate) Given in mmol/L. Normal range 22 -26

Don’t panic! But be cautious. . . Blood gasses contain a large amount of information, that is what makes them so useful. Learning the values takes time, however, always check the basics such as p. H, p. O 2, p. CO 2 Hb, electrolytes and base excess when you have performed a test, or get the patients doctor to sign that they have checked the results slip. It would be pointless, and possibly negligent, to perform a test that monitors the life chemistry of a person who is unwell, and not have those results reviewed by a competent person.

- Slides: 28