AQA A Level Psychology Paper 1 Memory AQA

- Slides: 33

AQA A Level Psychology Paper 1: Memory AQA A Level Revision Pack

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • The multi-store model of memory: sensory register, STM & LTM. • Features of each store: coding, capacity, duration & encoding.

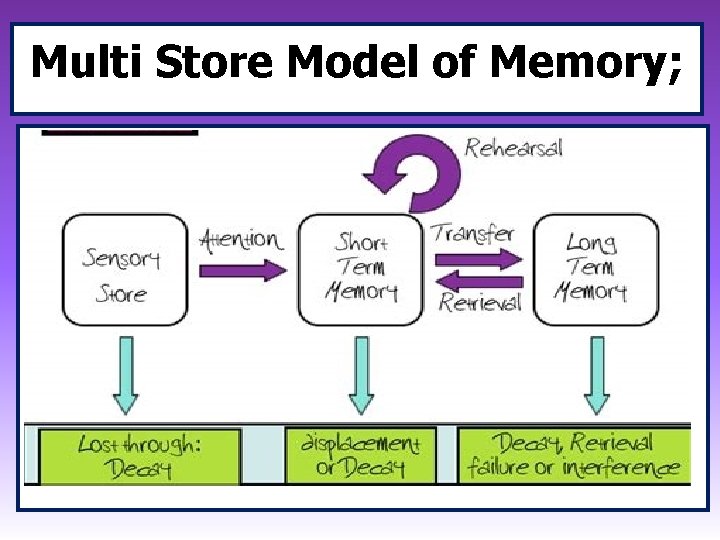

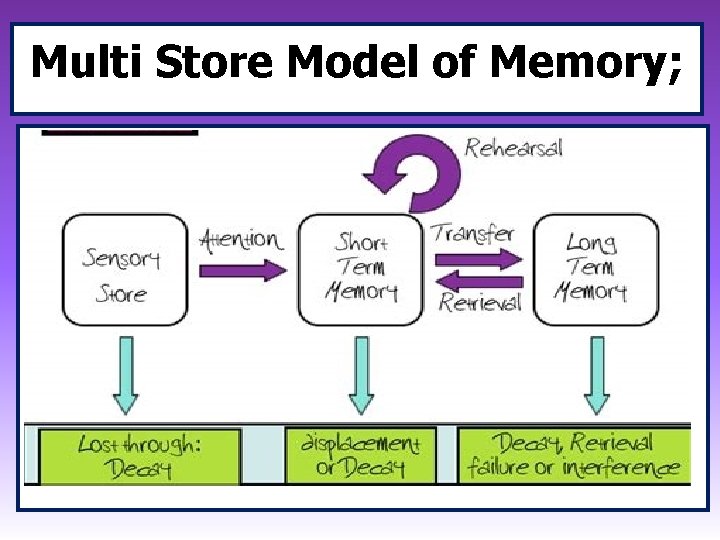

Multi Store Model of Memory;

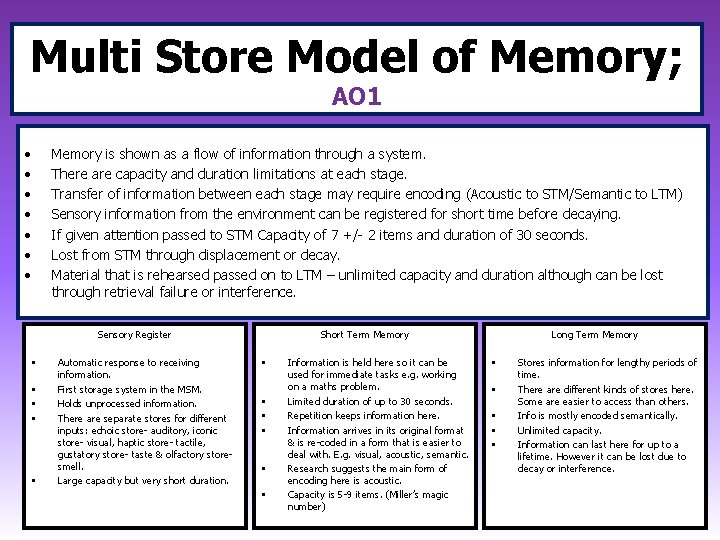

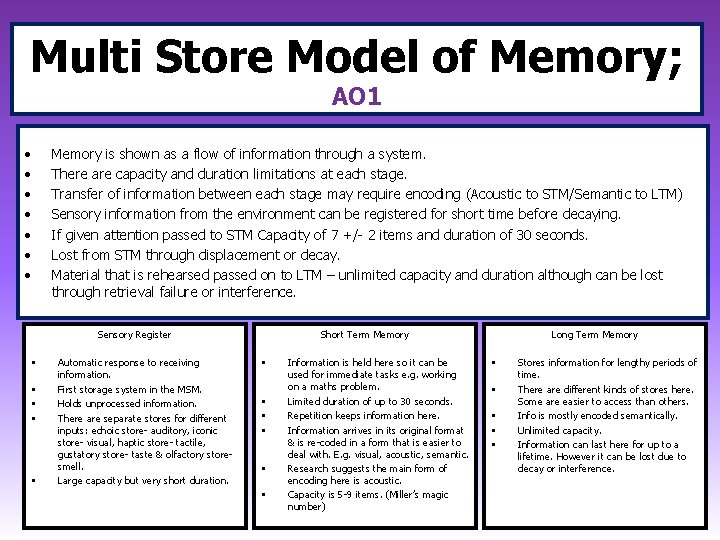

Multi Store Model of Memory; AO 1 • • Memory is shown as a flow of information through a system. There are capacity and duration limitations at each stage. Transfer of information between each stage may require encoding (Acoustic to STM/Semantic to LTM) Sensory information from the environment can be registered for short time before decaying. If given attention passed to STM Capacity of 7 +/- 2 items and duration of 30 seconds. Lost from STM through displacement or decay. Material that is rehearsed passed on to LTM – unlimited capacity and duration although can be lost through retrieval failure or interference. Sensory Register • • • Automatic response to receiving information. First storage system in the MSM. Holds unprocessed information. There are separate stores for different inputs: echoic store- auditory, iconic store- visual, haptic store- tactile, gustatory store- taste & olfactory storesmell. Large capacity but very short duration. Short Term Memory • • • Information is held here so it can be used for immediate tasks e. g. working on a maths problem. Limited duration of up to 30 seconds. Repetition keeps information here. Information arrives in its original format & is re-coded in a form that is easier to deal with. E. g. visual, acoustic, semantic. Research suggests the main form of encoding here is acoustic. Capacity is 5 -9 items. (Miller’s magic number) Long Term Memory • • • Stores information for lengthy periods of time. There are different kinds of stores here. Some are easier to access than others. Info is mostly encoded semantically. Unlimited capacity. Information can last here for up to a lifetime. However it can be lost due to decay or interference.

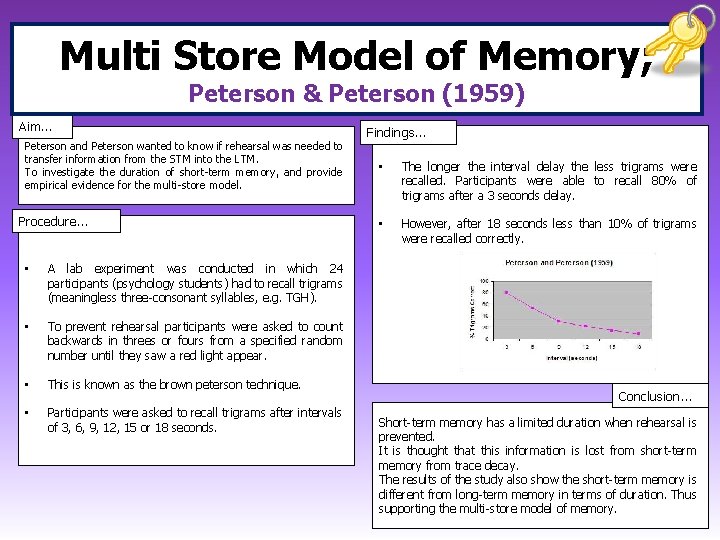

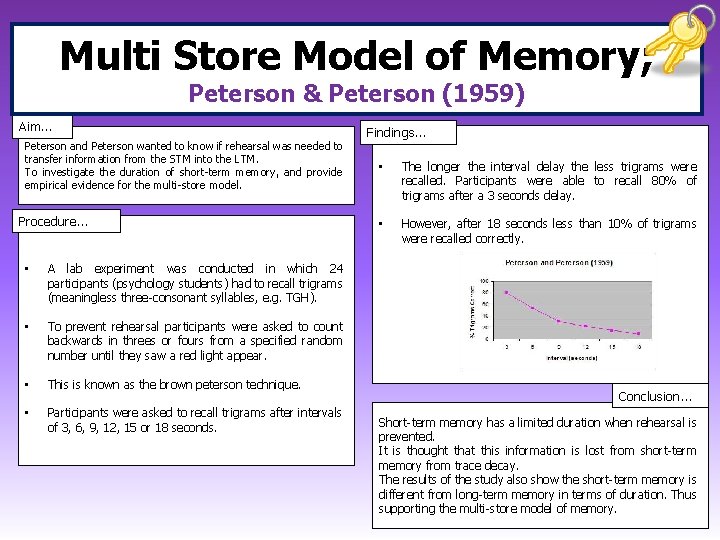

Multi Store Model of Memory; Peterson & Peterson (1959) Aim… Peterson and Peterson wanted to know if rehearsal was needed to transfer information from the STM into the LTM. To investigate the duration of short-term memory, and provide empirical evidence for the multi-store model. Procedure… • A lab experiment was conducted in which 24 participants (psychology students) had to recall trigrams (meaningless three-consonant syllables, e. g. TGH). • To prevent rehearsal participants were asked to count backwards in threes or fours from a specified random number until they saw a red light appear. • This is known as the brown peterson technique. • Participants were asked to recall trigrams after intervals of 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 or 18 seconds. Findings… • The longer the interval delay the less trigrams were recalled. Participants were able to recall 80% of trigrams after a 3 seconds delay. • However, after 18 seconds less than 10% of trigrams were recalled correctly. Conclusion… Short-term memory has a limited duration when rehearsal is prevented. It is thought that this information is lost from short-term memory from trace decay. The results of the study also show the short-term memory is different from long-term memory in terms of duration. Thus supporting the multi-store model of memory.

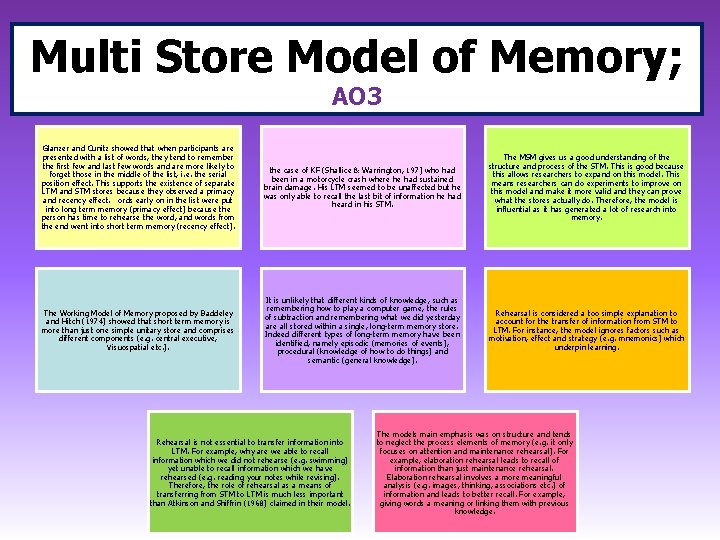

Multi Store Model of Memory; AO 3 Glanzer and Cunitz showed that when participants are presented with a list of words, they tend to remember the first few and last few words and are more likely to forget those in the middle of the list, i. e. the serial position effect. This supports the existence of separate LTM and STM stores because they observed a primacy and recency effect. ords early on in the list were put into long term memory (primacy effect) because the person has time to rehearse the word, and words from the end went into short term memory (recency effect). the case of KF (Shallice & Warrington, 197) who had been in a motorcycle crash where he had sustained brain damage. His LTM seemed to be unaffected but he was only able to recall the last bit of information he had heard in his STM. The MSM gives us a good understanding of the structure and process of the STM. This is good because this allows researchers to expand on this model. This means researchers can do experiments to improve on this model and make it more valid and they can prove what the stores actually do. Therefore, the model is influential as it has generated a lot of research into memory. The Working Model of Memory proposed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) showed that short term memory is more than just one simple unitary store and comprises different components (e. g. central executive, Visuospatial etc. ). It is unlikely that different kinds of knowledge, such as remembering how to play a computer game, the rules of subtraction and remembering what we did yesterday are all stored within a single, long-term memory store. Indeed different types of long-term memory have been identified, namely episodic (memories of events), procedural (knowledge of how to do things) and semantic (general knowledge). Rehearsal is considered a too simple explanation to account for the transfer of information from STM to LTM. For instance, the model ignores factors such as motivation, effect and strategy (e. g. mnemonics) which underpin learning. Rehearsal is not essential to transfer information into LTM. For example, why are we able to recall information which we did not rehearse (e. g. swimming) yet unable to recall information which we have rehearsed (e. g. reading your notes while revising). Therefore, the role of rehearsal as a means of transferring from STM to LTM is much less important than Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) claimed in their model. The models main emphasis was on structure and tends to neglect the process elements of memory (e. g. it only focuses on attention and maintenance rehearsal). For example, elaboration rehearsal leads to recall of information than just maintenance rehearsal. Elaboration rehearsal involves a more meaningful analysis (e. g. images, thinking, associations etc. ) of information and leads to better recall. For example, giving words a meaning or linking them with previous knowledge.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • The working memory model: central executive, phonological loop, visuo-spatial sketchpad & episodic buffer. • Features of the model: coding and capacity.

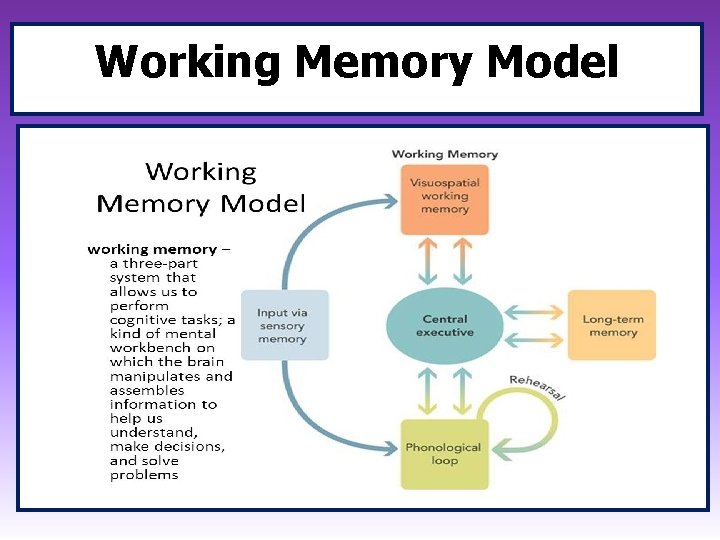

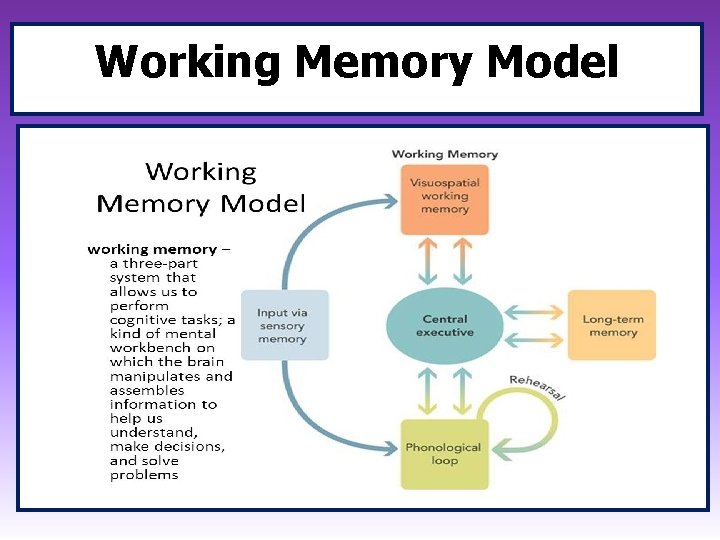

Working Memory Model

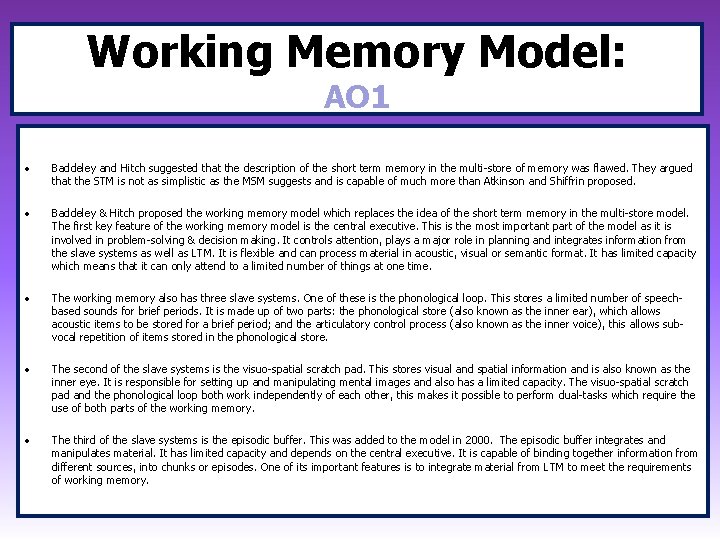

Working Memory Model: AO 1 • Baddeley and Hitch suggested that the description of the short term memory in the multi-store of memory was flawed. They argued that the STM is not as simplistic as the MSM suggests and is capable of much more than Atkinson and Shiffrin proposed. • Baddeley & Hitch proposed the working memory model which replaces the idea of the short term memory in the multi-store model. The first key feature of the working memory model is the central executive. This is the most important part of the model as it is involved in problem-solving & decision making. It controls attention, plays a major role in planning and integrates information from the slave systems as well as LTM. It is flexible and can process material in acoustic, visual or semantic format. It has limited capacity which means that it can only attend to a limited number of things at one time. • The working memory also has three slave systems. One of these is the phonological loop. This stores a limited number of speechbased sounds for brief periods. It is made up of two parts: the phonological store (also known as the inner ear), which allows acoustic items to be stored for a brief period; and the articulatory control process (also known as the inner voice), this allows subvocal repetition of items stored in the phonological store. • The second of the slave systems is the visuo-spatial scratch pad. This stores visual and spatial information and is also known as the inner eye. It is responsible for setting up and manipulating mental images and also has a limited capacity. The visuo-spatial scratch pad and the phonological loop both work independently of each other, this makes it possible to perform dual-tasks which require the use of both parts of the working memory. • The third of the slave systems is the episodic buffer. This was added to the model in 2000. The episodic buffer integrates and manipulates material. It has limited capacity and depends on the central executive. It is capable of binding together information from different sources, into chunks or episodes. One of its important features is to integrate material from LTM to meet the requirements of working memory.

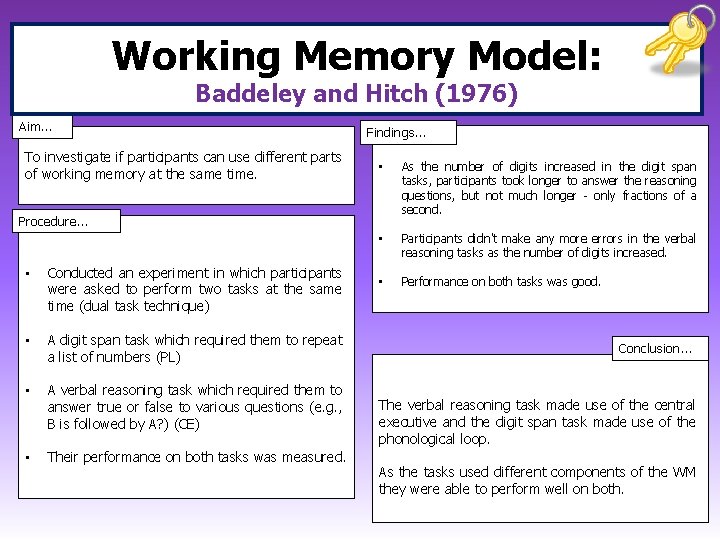

Working Memory Model: Baddeley and Hitch (1976) Aim… To investigate if participants can use different parts of working memory at the same time. Findings… • As the number of digits increased in the digit span tasks, participants took longer to answer the reasoning questions, but not much longer - only fractions of a second. • Participants didn't make any more errors in the verbal reasoning tasks as the number of digits increased. • Performance on both tasks was good. Procedure… • Conducted an experiment in which participants were asked to perform two tasks at the same time (dual task technique) • A digit span task which required them to repeat a list of numbers (PL) • A verbal reasoning task which required them to answer true or false to various questions (e. g. , B is followed by A? ) (CE) • Their performance on both tasks was measured. Conclusion… The verbal reasoning task made use of the central executive and the digit span task made use of the phonological loop. As the tasks used different components of the WM they were able to perform well on both.

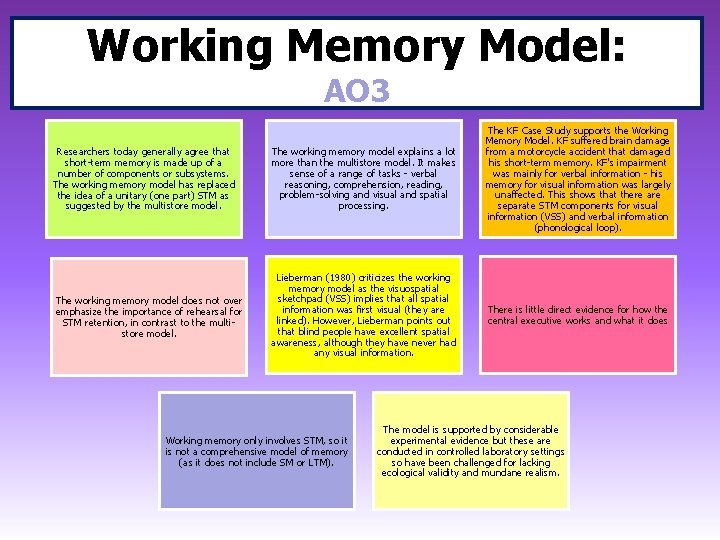

Working Memory Model: AO 3 Researchers today generally agree that short-term memory is made up of a number of components or subsystems. The working memory model has replaced the idea of a unitary (one part) STM as suggested by the multistore model. The working memory model explains a lot more than the multistore model. It makes sense of a range of tasks - verbal reasoning, comprehension, reading, problem-solving and visual and spatial processing. The KF Case Study supports the Working Memory Model. KF suffered brain damage from a motorcycle accident that damaged his short-term memory. KF's impairment was mainly for verbal information - his memory for visual information was largely unaffected. This shows that there are separate STM components for visual information (VSS) and verbal information (phonological loop). The working memory model does not over emphasize the importance of rehearsal for STM retention, in contrast to the multistore model. Lieberman (1980) criticizes the working memory model as the visuospatial sketchpad (VSS) implies that all spatial information was first visual (they are linked). However, Lieberman points out that blind people have excellent spatial awareness, although they have never had any visual information. There is little direct evidence for how the central executive works and what it does Working memory only involves STM, so it is not a comprehensive model of memory (as it does not include SM or LTM). The model is supported by considerable experimental evidence but these are conducted in controlled laboratory settings so have been challenged for lacking ecological validity and mundane realism.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • Types of long-term memory: – Episodic – Semantic – Procedural.

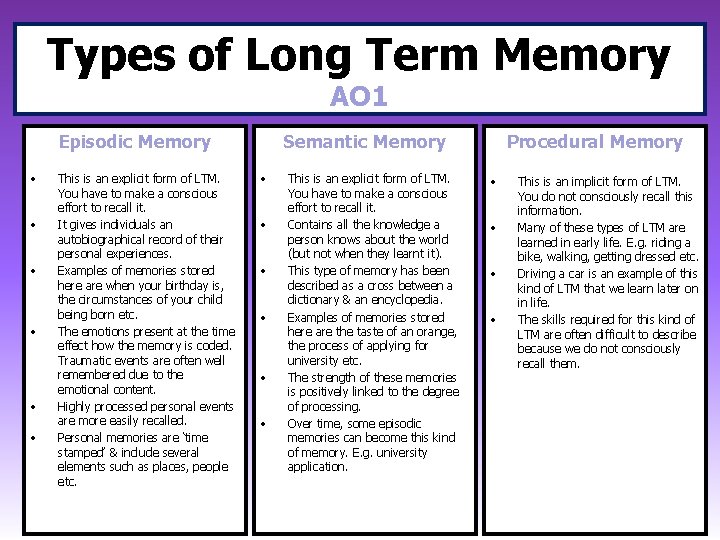

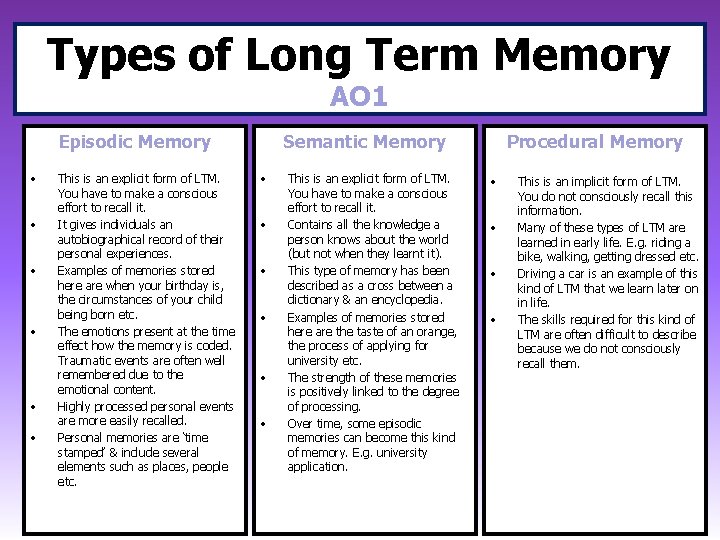

Types of Long Term Memory AO 1 Episodic Memory • • • This is an explicit form of LTM. You have to make a conscious effort to recall it. It gives individuals an autobiographical record of their personal experiences. Examples of memories stored here are when your birthday is, the circumstances of your child being born etc. The emotions present at the time effect how the memory is coded. Traumatic events are often well remembered due to the emotional content. Highly processed personal events are more easily recalled. Personal memories are ‘time stamped’ & include several elements such as places, people etc. Semantic Memory • • • This is an explicit form of LTM. You have to make a conscious effort to recall it. Contains all the knowledge a person knows about the world (but not when they learnt it). This type of memory has been described as a cross between a dictionary & an encyclopedia. Examples of memories stored here are the taste of an orange, the process of applying for university etc. The strength of these memories is positively linked to the degree of processing. Over time, some episodic memories can become this kind of memory. E. g. university application. Procedural Memory • • This is an implicit form of LTM. You do not consciously recall this information. Many of these types of LTM are learned in early life. E. g. riding a bike, walking, getting dressed etc. Driving a car is an example of this kind of LTM that we learn later on in life. The skills required for this kind of LTM are often difficult to describe because we do not consciously recall them.

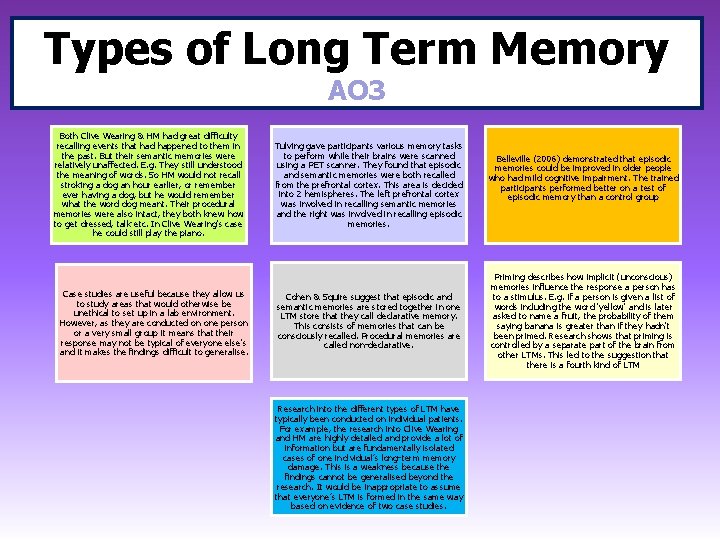

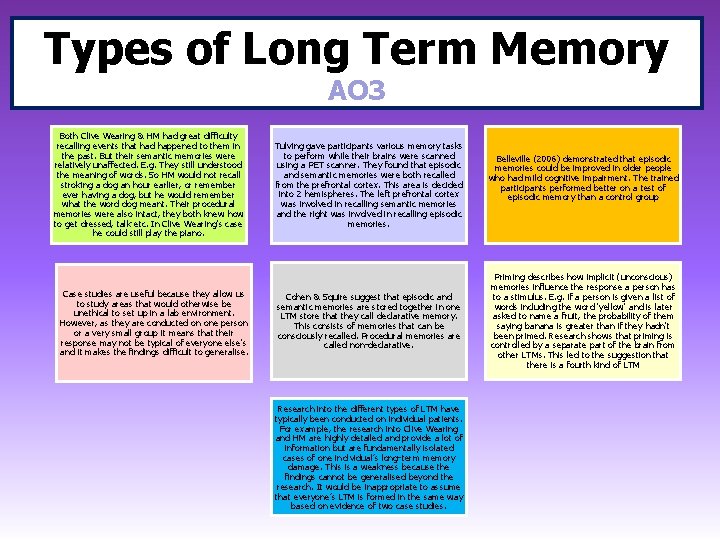

Types of Long Term Memory AO 3 Both Clive Wearing & HM had great difficulty recalling events that had happened to them in the past. But their semantic memories were relatively unaffected. E. g. They still understood the meaning of words. So HM would not recall stroking a dog an hour earlier, or remember ever having a dog, but he would remember what the word dog meant. Their procedural memories were also intact, they both knew how to get dressed, talk etc. In Clive Wearing's case he could still play the piano. Case studies are useful because they allow us to study areas that would otherwise be unethical to set up in a lab environment. However, as they are conducted on one person or a very small group it means that their response may not be typical of everyone else's and it makes the findings difficult to generalise. Tulving gave participants various memory tasks to perform while their brains were scanned using a PET scanner. They found that episodic and semantic memories were both recalled from the prefrontal cortex. This area is decided into 2 hemispheres. The left prefrontal cortex was involved in recalling semantic memories and the right was involved in recalling episodic memories. Cohen & Squire suggest that episodic and semantic memories are stored together in one LTM store that they call declarative memory. This consists of memories that can be consciously recalled. Procedural memories are called non-declarative. Research into the different types of LTM have typically been conducted on individual patients. For example, the research into Clive Wearing and HM are highly detailed and provide a lot of information but are fundamentally isolated cases of one individual’s long-term memory damage. This is a weakness because the findings cannot be generalised beyond the research. It would be inappropriate to assume that everyone’s LTM is formed in the same way based on evidence of two case studies. Belleville (2006) demonstrated that episodic memories could be improved in older people who had mild cognitive impairment. The trained participants performed better on a test of episodic memory than a control group Priming describes how implicit (unconscious) memories influence the response a person has to a stimulus. E. g. if a person is given a list of words including the word 'yellow' and is later asked to name a fruit, the probability of them saying banana is greater than if they hadn't been primed. Research shows that priming is controlled by a separate part of the brain from other LTMs. This led to the suggestion that there is a fourth kind of LTM

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… Explanations forgetting: • Proactive and Retroactive Interference • Retrieval failure due to absence of cues.

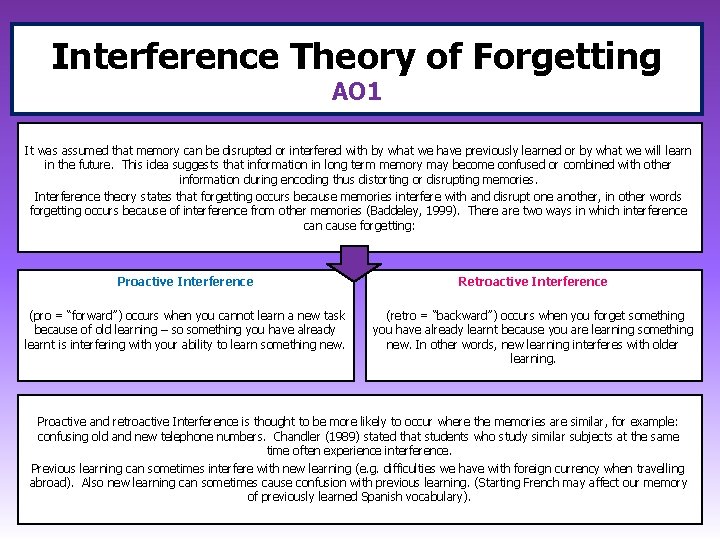

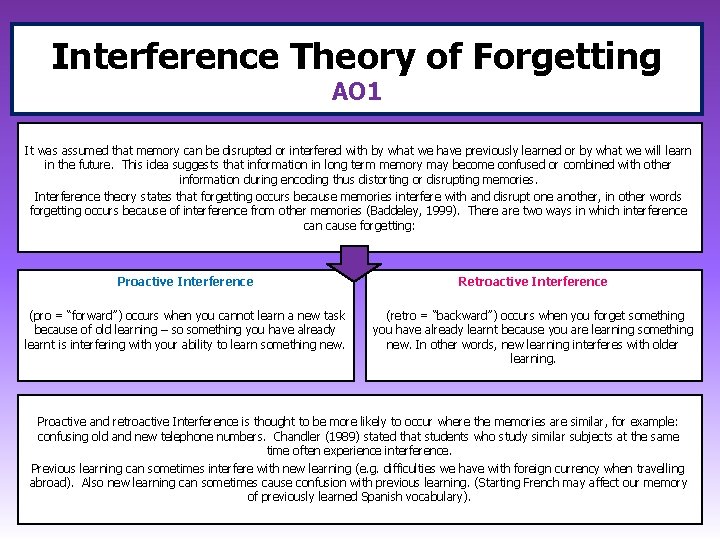

Interference Theory of Forgetting AO 1 It was assumed that memory can be disrupted or interfered with by what we have previously learned or by what we will learn in the future. This idea suggests that information in long term memory may become confused or combined with other information during encoding thus distorting or disrupting memories. Interference theory states that forgetting occurs because memories interfere with and disrupt one another, in other words forgetting occurs because of interference from other memories (Baddeley, 1999). There are two ways in which interference can cause forgetting: Proactive Interference Retroactive Interference (pro = “forward”) occurs when you cannot learn a new task because of old learning – so something you have already learnt is interfering with your ability to learn something new. (retro = “backward”) occurs when you forget something you have already learnt because you are learning something new. In other words, new learning interferes with older learning. Proactive and retroactive Interference is thought to be more likely to occur where the memories are similar, for example: confusing old and new telephone numbers. Chandler (1989) stated that students who study similar subjects at the same time often experience interference. Previous learning can sometimes interfere with new learning (e. g. difficulties we have with foreign currency when travelling abroad). Also new learning can sometimes cause confusion with previous learning. (Starting French may affect our memory of previously learned Spanish vocabulary).

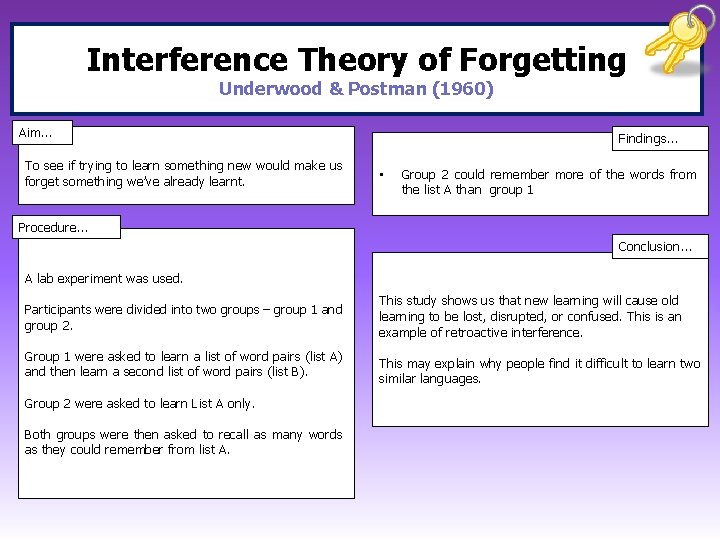

Interference Theory of Forgetting Underwood & Postman (1960) Aim… To see if trying to learn something new would make us forget something we’ve already learnt. Findings… • Group 2 could remember more of the words from the list A than group 1 Procedure… Conclusion… A lab experiment was used. Participants were divided into two groups – group 1 and group 2. Group 1 were asked to learn a list of word pairs (list A) and then learn a second list of word pairs (list B). Group 2 were asked to learn List A only. Both groups were then asked to recall as many words as they could remember from list A. This study shows us that new learning will cause old learning to be lost, disrupted, or confused. This is an example of retroactive interference. This may explain why people find it difficult to learn two similar languages.

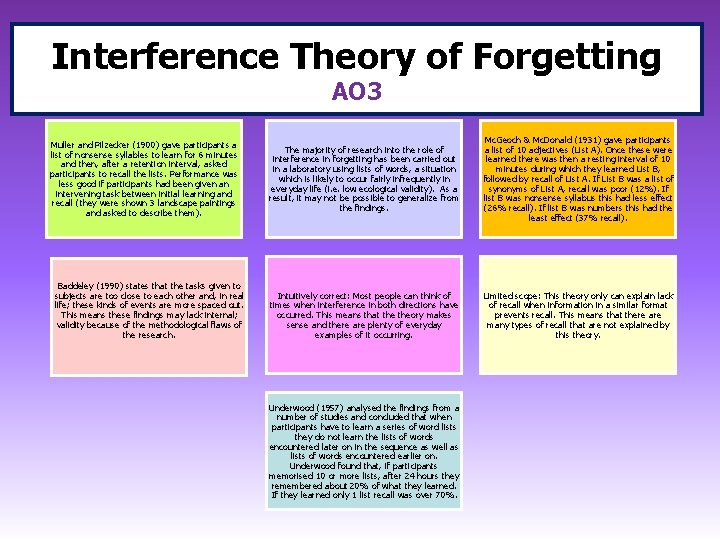

Interference Theory of Forgetting AO 3 Muller and Pilzecker (1900) gave participants a list of nonsense syllables to learn for 6 minutes and then, after a retention interval, asked participants to recall the lists. Performance was less good if participants had been given an intervening task between initial learning and recall (they were shown 3 landscape paintings and asked to describe them). Baddeley (1990) states that the tasks given to subjects are too close to each other and, in real life; these kinds of events are more spaced out. This means these findings may lack internal; validity because of the methodological flaws of the research. The majority of research into the role of interference in forgetting has been carried out in a laboratory using lists of words, a situation which is likely to occur fairly infrequently in everyday life (i. e. low ecological validity). As a result, it may not be possible to generalize from the findings. Mc. Geoch & Mc. Donald (1931) gave participants a list of 10 adjectives (List A). Once these were learned there was then a resting interval of 10 minutes during which they learned List B, followed by recall of List A. If List B was a list of synonyms of List A, recall was poor (12%). If list B was nonsense syllabus this had less effect (26% recall). If list B was numbers this had the least effect (37% recall). Intuitively correct: Most people can think of times when interference in both directions have occurred. This means that theory makes sense and there are plenty of everyday examples of it occurring. Limited scope: This theory only can explain lack of recall when information in a similar format prevents recall. This means that there are many types of recall that are not explained by this theory. Underwood (1957) analysed the findings from a number of studies and concluded that when participants have to learn a series of word lists they do not learn the lists of words encountered later on in the sequence as well as lists of words encountered earlier on. Underwood found that, if participants memorised 10 or more lists, after 24 hours they remembered about 20% of what they learned. If they learned only 1 list recall was over 70%.

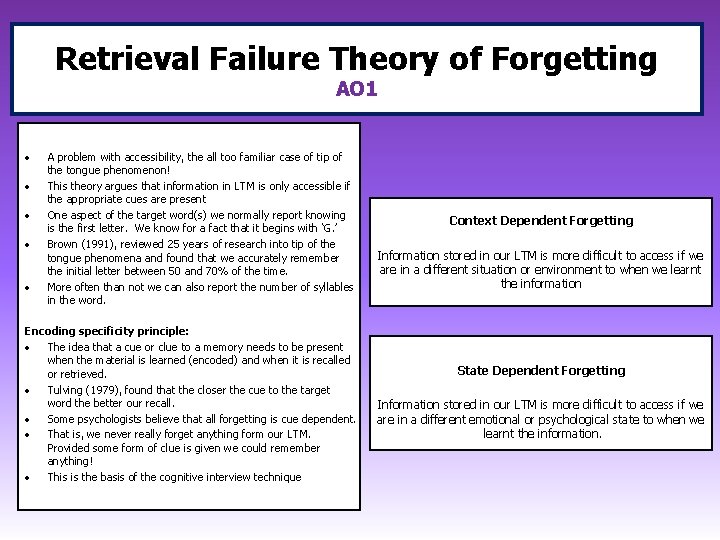

Retrieval Failure Theory of Forgetting AO 1 • • • A problem with accessibility, the all too familiar case of tip of the tongue phenomenon! This theory argues that information in LTM is only accessible if the appropriate cues are present One aspect of the target word(s) we normally report knowing is the first letter. We know for a fact that it begins with ‘G. ’ Brown (1991), reviewed 25 years of research into tip of the tongue phenomena and found that we accurately remember the initial letter between 50 and 70% of the time. More often than not we can also report the number of syllables in the word. Encoding specificity principle: • The idea that a cue or clue to a memory needs to be present when the material is learned (encoded) and when it is recalled or retrieved. • Tulving (1979), found that the closer the cue to the target word the better our recall. • Some psychologists believe that all forgetting is cue dependent. • That is, we never really forget anything form our LTM. Provided some form of clue is given we could remember anything! • This is the basis of the cognitive interview technique Context Dependent Forgetting Information stored in our LTM is more difficult to access if we are in a different situation or environment to when we learnt the information State Dependent Forgetting Information stored in our LTM is more difficult to access if we are in a different emotional or psychological state to when we learnt the information.

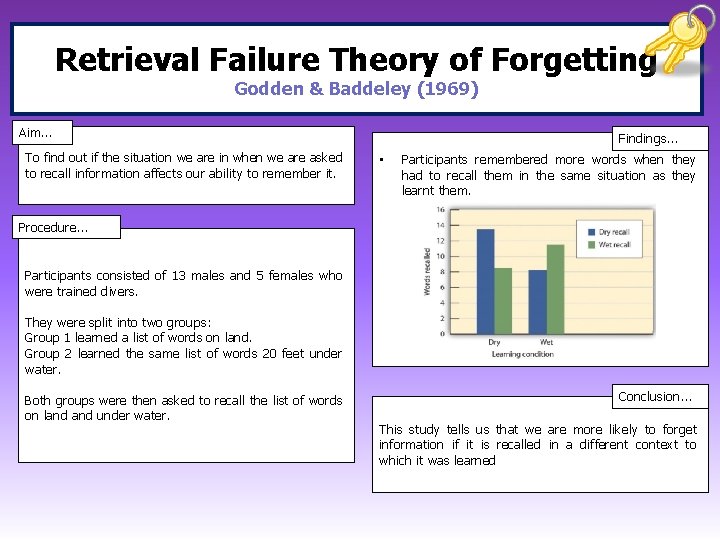

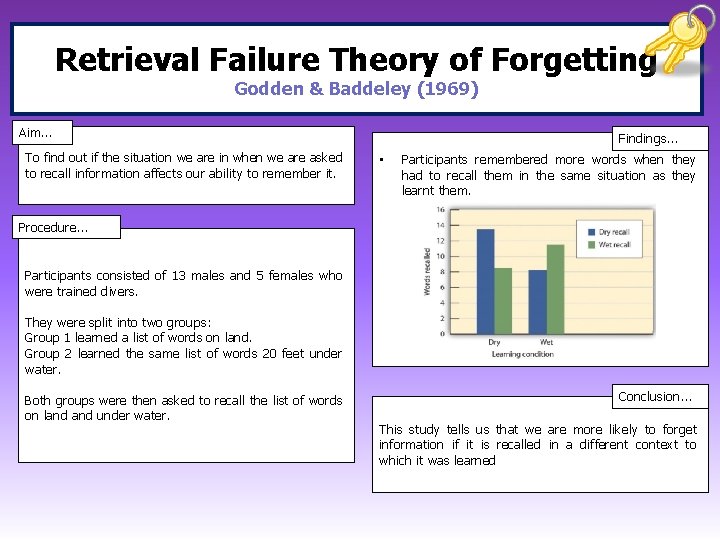

Retrieval Failure Theory of Forgetting Godden & Baddeley (1969) Aim… To find out if the situation we are in when we are asked to recall information affects our ability to remember it. Findings… • Participants remembered more words when they had to recall them in the same situation as they learnt them. Procedure… Participants consisted of 13 males and 5 females who were trained divers. They were split into two groups: Group 1 learned a list of words on land. Group 2 learned the same list of words 20 feet under water. Both groups were then asked to recall the list of words on land under water. Conclusion… This study tells us that we are more likely to forget information if it is recalled in a different context to which it was learned

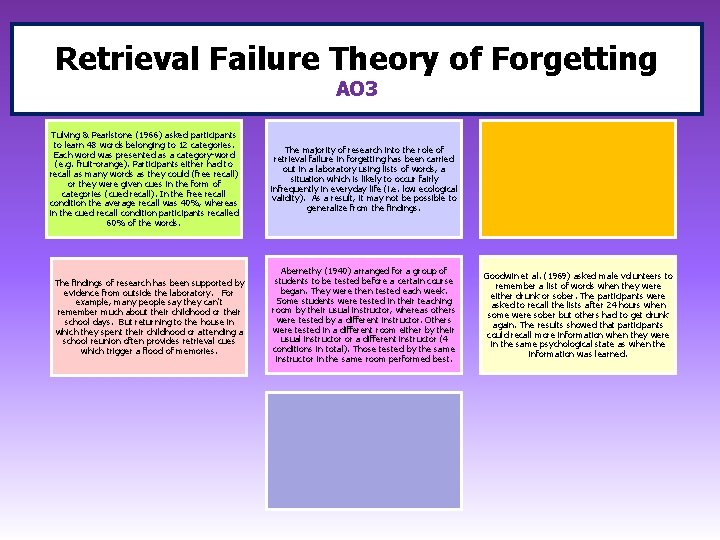

Retrieval Failure Theory of Forgetting AO 3 Tulving & Pearlstone (1966) asked participants to learn 48 words belonging to 12 categories. Each word was presented as a category-word (e. g. fruit-orange). Participants either had to recall as many words as they could (free recall) or they were given cues in the form of categories (cued recall). In the free recall condition the average recall was 40%, whereas in the cued recall condition participants recalled 60% of the words. The findings of research has been supported by evidence from outside the laboratory. For example, many people say they can't remember much about their childhood or their school days. But returning to the house in which they spent their childhood or attending a school reunion often provides retrieval cues which trigger a flood of memories. The majority of research into the role of retrieval failure in forgetting has been carried out in a laboratory using lists of words, a situation which is likely to occur fairly infrequently in everyday life (i. e. low ecological validity). As a result, it may not be possible to generalize from the findings. Abernethy (1940) arranged for a group of students to be tested before a certain course began. They were then tested each week. Some students were tested in their teaching room by their usual instructor, whereas others were tested by a different instructor. Others were tested in a different room either by their usual instructor or a different instructor (4 conditions in total). Those tested by the same instructor in the same room performed best. Goodwin et al. (1969) asked male volunteers to remember a list of words when they were either drunk or sober. The participants were asked to recall the lists after 24 hours when some were sober but others had to get drunk again. The results showed that participants could recall more information when they were in the same psychological state as when the information was learned.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… Factors effecting eyewitness testimony including: • Anxiety • Leading Questions • Post-Event Discussion.

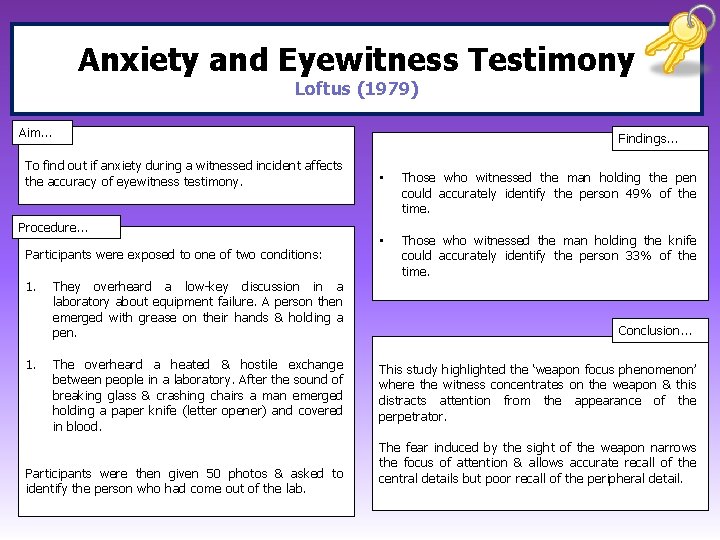

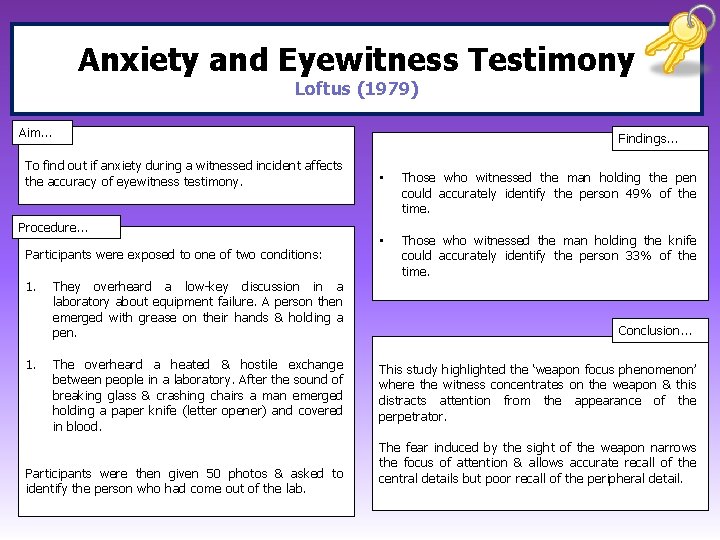

Anxiety and Eyewitness Testimony Loftus (1979) Aim… Findings… To find out if anxiety during a witnessed incident affects the accuracy of eyewitness testimony. Procedure… Participants were exposed to one of two conditions: 1. They overheard a low-key discussion in a laboratory about equipment failure. A person then emerged with grease on their hands & holding a pen. The overheard a heated & hostile exchange between people in a laboratory. After the sound of breaking glass & crashing chairs a man emerged holding a paper knife (letter opener) and covered in blood. Participants were then given 50 photos & asked to identify the person who had come out of the lab. • Those who witnessed the man holding the pen could accurately identify the person 49% of the time. • Those who witnessed the man holding the knife could accurately identify the person 33% of the time. Conclusion… This study highlighted the ‘weapon focus phenomenon’ where the witness concentrates on the weapon & this distracts attention from the appearance of the perpetrator. The fear induced by the sight of the weapon narrows the focus of attention & allows accurate recall of the central details but poor recall of the peripheral detail.

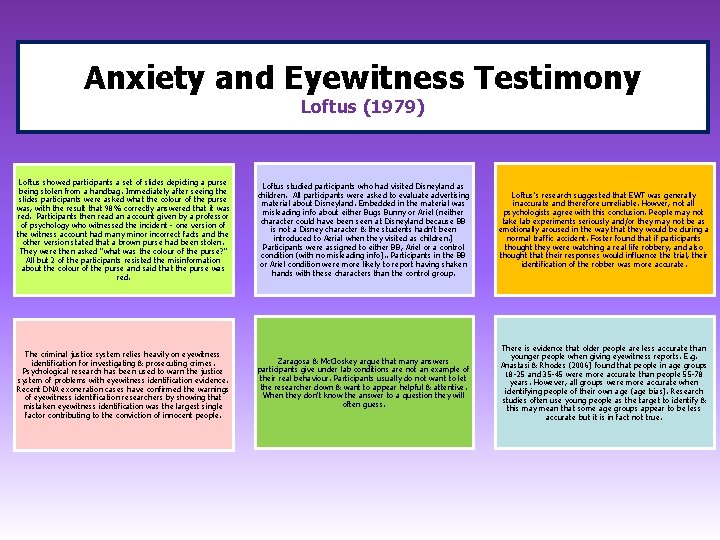

Anxiety and Eyewitness Testimony Loftus (1979) Loftus showed participants a set of slides depicting a purse being stolen from a handbag. Immediately after seeing the slides participants were asked what the colour of the purse was, with the result that 98% correctly answered that it was red. Participants then read an account given by a professor of psychology who witnessed the incident - one version of the witness account had many minor incorrect facts and the other version stated that a brown purse had been stolen. They were then asked “what was the colour of the purse? ” All but 2 of the participants resisted the misinformation about the colour of the purse and said that the purse was red. Loftus studied participants who had visited Disneyland as children. All participants were asked to evaluate advertising material about Disneyland. Embedded in the material was misleading info about either Bugs Bunny or Ariel (neither character could have been seen at Disneyland because BB is not a Disney character & the students hadn't been introduced to Aerial when they visited as children. ) Participants were assigned to either BB, Ariel or a control condition (with no misleading info). . Participants in the BB or Ariel condition were more likely to report having shaken hands with these characters than the control group. Loftus's research suggested that EWT was generally inaccurate and therefore unreliable. Howver, not all psychologists agree with this conclusion. People may not take lab experiments seriously and/or they may not be as emotionally aroused in the way that they would be during a normal traffic accident. Foster found that if participants thought they were watching a real life robbery, and also thought that their responses would influence the trial, their identification of the robber was more accurate. The criminal justice system relies heavily on eyewitness identification for investigating & prosecuting crimes. Psychological research has been used to warn the justice system of problems with eyewitness identification evidence. Recent DNA exoneration cases have confirmed the warnings of eyewitness identification researchers by showing that mistaken eyewitness identification was the largest single factor contributing to the conviction of innocent people. Zaragosa & Mc. Closkey argue that many answers participants give under lab conditions are not an example of their real behaviour. Participants usually do not want to let the researcher down & want to appear helpful & attentive. When they don’t know the answer to a question they will often guess. There is evidence that older people are less accurate than younger people when giving eyewitness reports. E. g. Anastasi & Rhodes (2006) found that people in age groups 18 -25 and 35 -45 were more accurate than people 55 -78 years. However, all groups were more accurate when identifying people of their own age (age bias). Research studies often use young people as the target to identify & this may mean that some age groups appear to be less accurate but it is in fact not true.

Misleading Information and EWT AO 1 Misleading Information Incorrect info given to an eyewitness usually after the event. It can take many forms such as leading questions & post event discussion between cowitnesses and/or other people. Leading Questions A question which, because of the way that it is phrased, suggests a certain answer. E. g. How old was the young man? Post-Event Discussion PED occurs when there is more than one witness to an event. Witnesses may discuss what they have seen with co-witnesses or other people. This may influence the accuracy of each witness’s recall of the event.

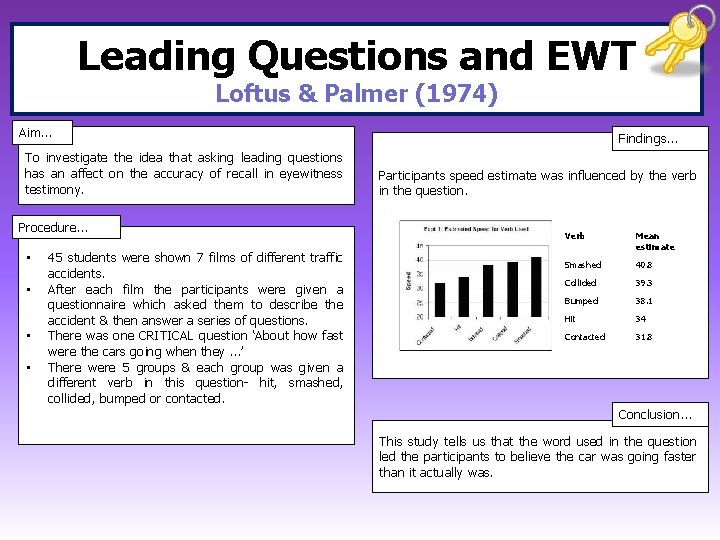

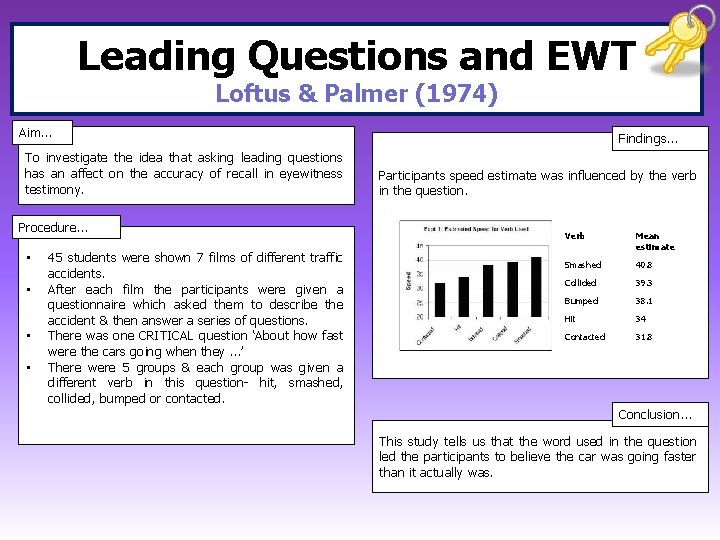

Leading Questions and EWT Loftus & Palmer (1974) Aim… To investigate the idea that asking leading questions has an affect on the accuracy of recall in eyewitness testimony. Procedure… • • 45 students were shown 7 films of different traffic accidents. After each film the participants were given a questionnaire which asked them to describe the accident & then answer a series of questions. There was one CRITICAL question ‘About how fast were the cars going when they …’ There were 5 groups & each group was given a different verb in this question- hit, smashed, collided, bumped or contacted. Findings… Participants speed estimate was influenced by the verb in the question. Verb Mean estimate Smashed 40. 8 Collided 39. 3 Bumped 38. 1 Hit 34 Contacted 31. 8 Conclusion… This study tells us that the word used in the question led the participants to believe the car was going faster than it actually was.

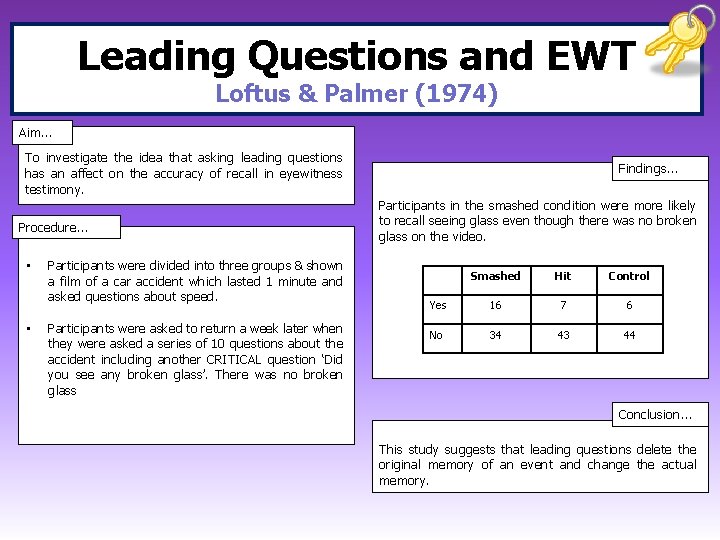

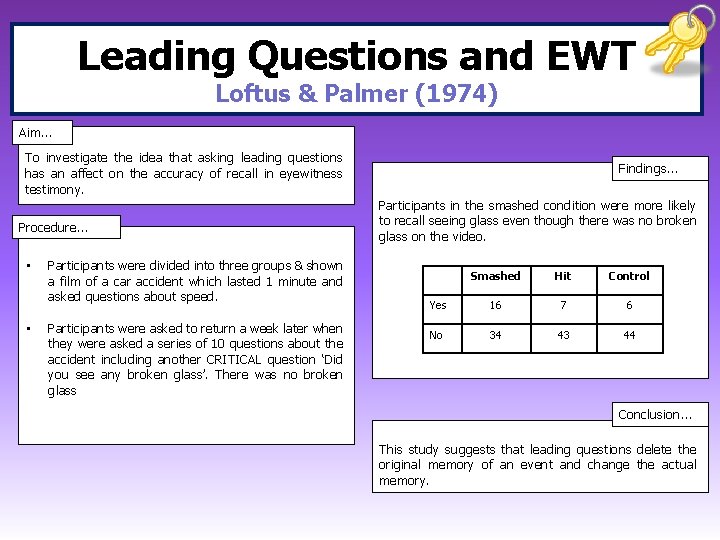

Leading Questions and EWT Loftus & Palmer (1974) Aim… To investigate the idea that asking leading questions has an affect on the accuracy of recall in eyewitness testimony. Procedure… • • Participants were divided into three groups & shown a film of a car accident which lasted 1 minute and asked questions about speed. Participants were asked to return a week later when they were asked a series of 10 questions about the accident including another CRITICAL question ‘Did you see any broken glass’. There was no broken glass Findings… Participants in the smashed condition were more likely to recall seeing glass even though there was no broken glass on the video. Smashed Hit Control Yes 16 7 6 No 34 43 44 Conclusion… This study suggests that leading questions delete the original memory of an event and change the actual memory.

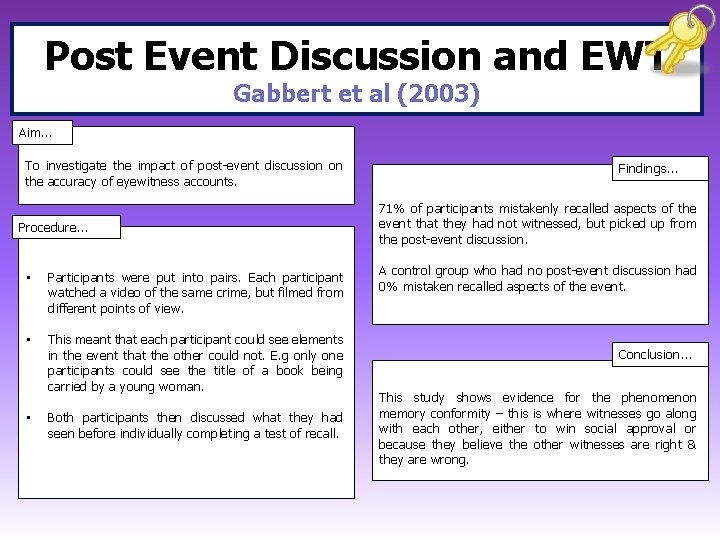

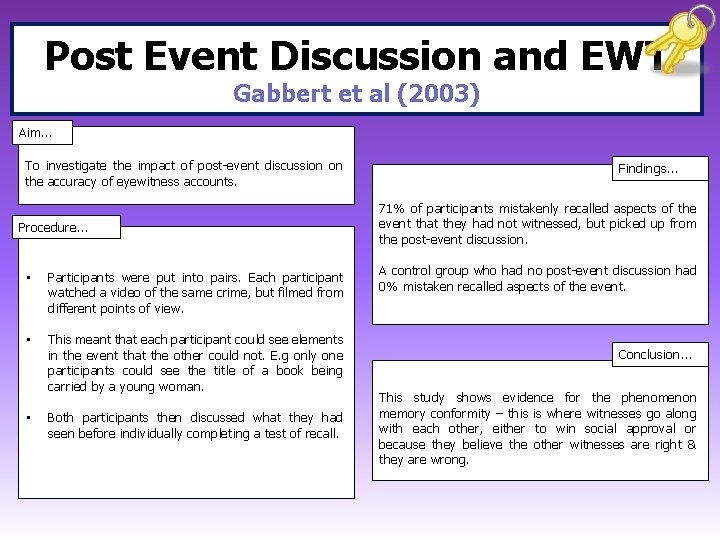

Post Event Discussion and EWT Gabbert et al (2003) Aim… To investigate the impact of post-event discussion on the accuracy of eyewitness accounts. Procedure… • Participants were put into pairs. Each participant watched a video of the same crime, but filmed from different points of view. • This meant that each participant could see elements in the event that the other could not. E. g only one participants could see the title of a book being carried by a young woman. • Both participants then discussed what they had seen before individually completing a test of recall. Findings… 71% of participants mistakenly recalled aspects of the event that they had not witnessed, but picked up from the post-event discussion. A control group who had no post-event discussion had 0% mistaken recalled aspects of the event. Conclusion… This study shows evidence for the phenomenon memory conformity – this is where witnesses go along with each other, either to win social approval or because they believe the other witnesses are right & they are wrong.

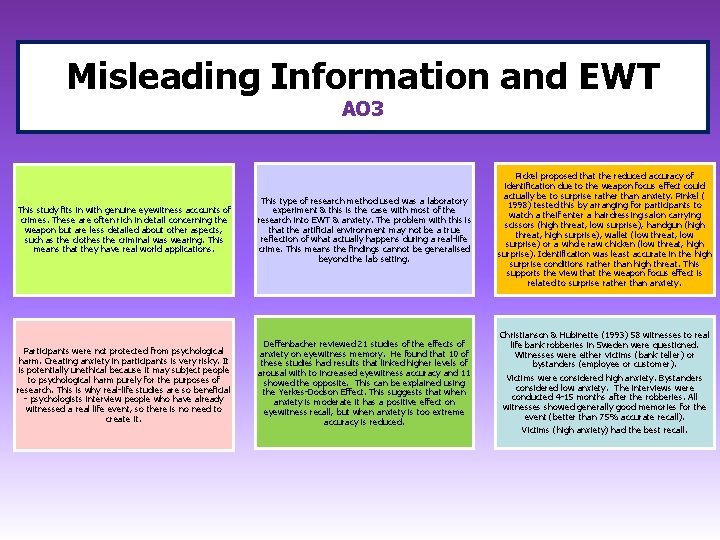

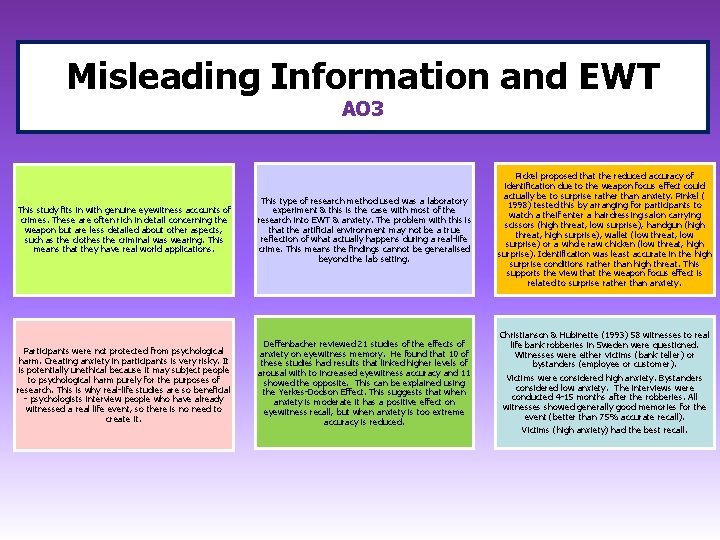

Misleading Information and EWT AO 3 This study fits in with genuine eyewitness accounts of crimes. These are often rich in detail concerning the weapon but are less detailed about other aspects, such as the clothes the criminal was wearing. This means that they have real world applications. This type of research method used was a laboratory experiment & this is the case with most of the research into EWT & anxiety. The problem with this is that the artificial environment may not be a true reflection of what actually happens during a real-life crime. This means the findings cannot be generalised beyond the lab setting. Pickel proposed that the reduced accuracy of identification due to the weapon focus effect could actually be to surprise rather than anxiety. Pinkel ( 1998) tested this by arranging for participants to watch a theif enter a hairdressing salon carrying scissors (high threat, low surprise), handgun (high threat, high surprise), wallet (low threat, low surprise) or a whole raw chicken (low threat, high surprise). Identification was least accurate in the high surprise conditions rather than high threat. This supports the view that the weapon focus effect is related to surprise rather than anxiety. Participants were not protected from psychological harm. Creating anxiety in participants is very risky. It is potentially unethical because it may subject people to psychological harm purely for the purposes of research. This is why real-life studies are so beneficial - psychologists interview people who have already witnessed a real life event, so there is no need to create it. Deffenbacher reviewed 21 studies of the effects of anxiety on eyewitness memory. He found that 10 of these studies had results that linked higher levels of arousal with to increased eyewitness accuracy and 11 showed the opposite. This can be explained using the Yerkes-Dodson Effect. This suggests that when anxiety is moderate it has a positive effect on eyewitness recall, but when anxiety is too extreme accuracy is reduced. Christianson & Hubinette (1993) 58 witnesses to real life bank robberies in Sweden were questioned. Witnesses were either victims (bank teller) or bystanders (employee or customer). Victims were considered high anxiety. Bystanders considered low anxiety. The interviews were conducted 4 -15 months after the robberies. All witnesses showed generally good memories for the event (better than 75% accurate recall). Victims (high anxiety) had the best recall.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… Improving the accuracy of eyewitness testimony, including the use of the cognitive interview.

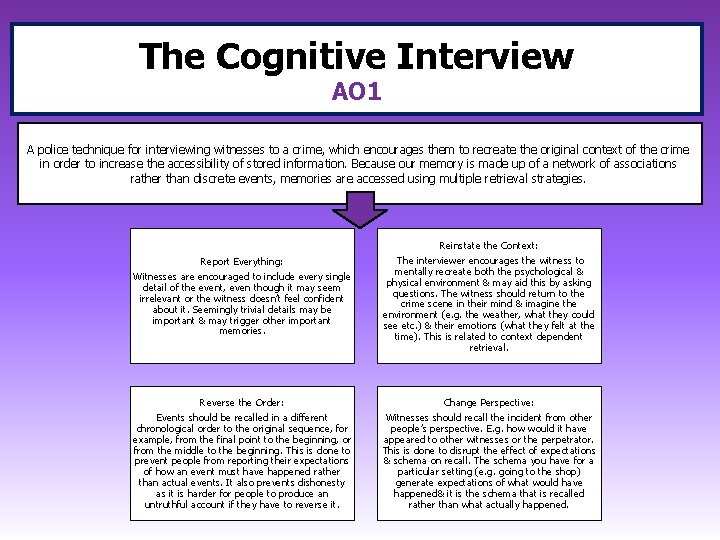

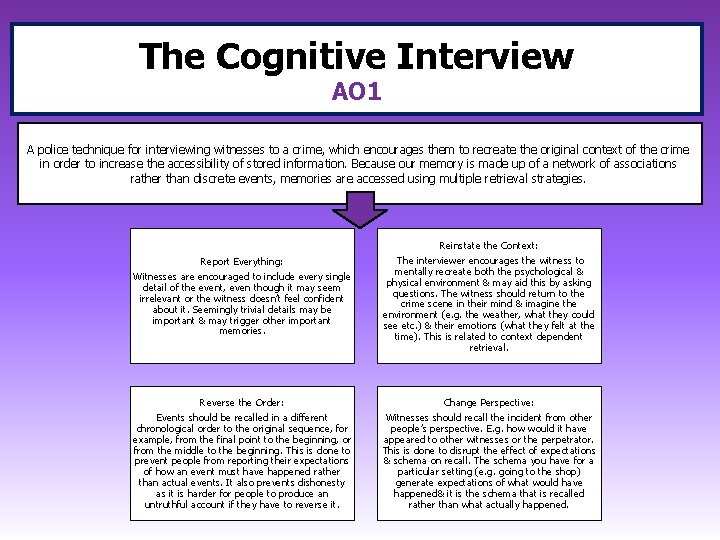

The Cognitive Interview AO 1 A police technique for interviewing witnesses to a crime, which encourages them to recreate the original context of the crime in order to increase the accessibility of stored information. Because our memory is made up of a network of associations rather than discrete events, memories are accessed using multiple retrieval strategies. Report Everything: Witnesses are encouraged to include every single detail of the event, even though it may seem irrelevant or the witness doesn’t feel confident about it. Seemingly trivial details may be important & may trigger other important memories. Reinstate the Context: The interviewer encourages the witness to mentally recreate both the psychological & physical environment & may aid this by asking questions. The witness should return to the crime scene in their mind & imagine the environment (e. g. the weather, what they could see etc. ) & their emotions (what they felt at the time). This is related to context dependent retrieval. Reverse the Order: Events should be recalled in a different chronological order to the original sequence, for example, from the final point to the beginning, or from the middle to the beginning. This is done to prevent people from reporting their expectations of how an event must have happened rather than actual events. It also prevents dishonesty as it is harder for people to produce an untruthful account if they have to reverse it. Change Perspective: Witnesses should recall the incident from other people’s perspective. E. g. how would it have appeared to other witnesses or the perpetrator. This is done to disrupt the effect of expectations & schema on recall. The schema you have for a particular setting (e. g. going to the shop) generate expectations of what would have happened& it is the schema that is recalled rather than what actually happened.

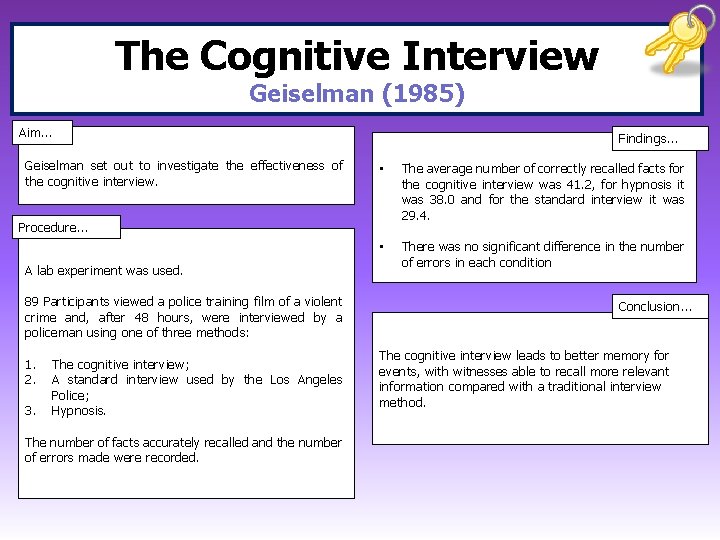

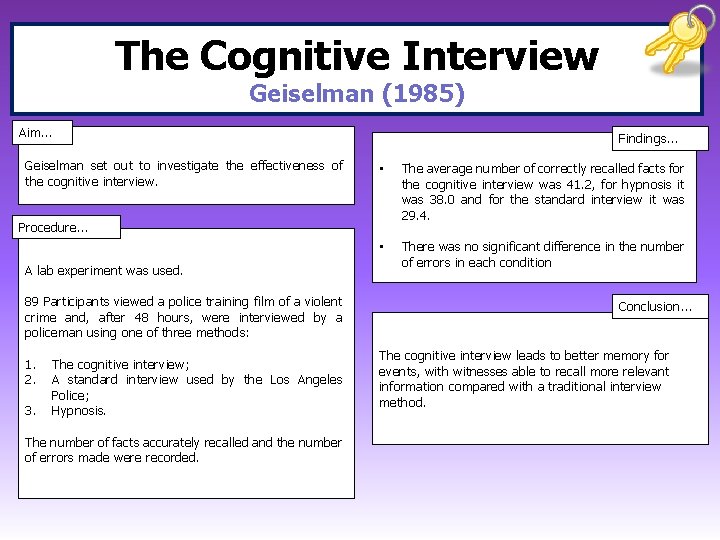

The Cognitive Interview Geiselman (1985) Aim… Findings… Geiselman set out to investigate the effectiveness of the cognitive interview. • The average number of correctly recalled facts for the cognitive interview was 41. 2, for hypnosis it was 38. 0 and for the standard interview it was 29. 4. • There was no significant difference in the number of errors in each condition Procedure… A lab experiment was used. 89 Participants viewed a police training film of a violent crime and, after 48 hours, were interviewed by a policeman using one of three methods: 1. 2. 3. The cognitive interview; A standard interview used by the Los Angeles Police; Hypnosis. The number of facts accurately recalled and the number of errors made were recorded. Conclusion… The cognitive interview leads to better memory for events, with witnesses able to recall more relevant information compared with a traditional interview method.

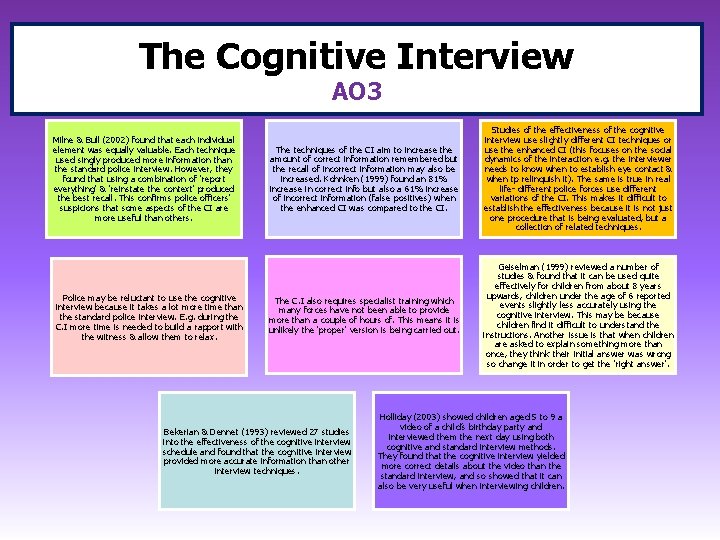

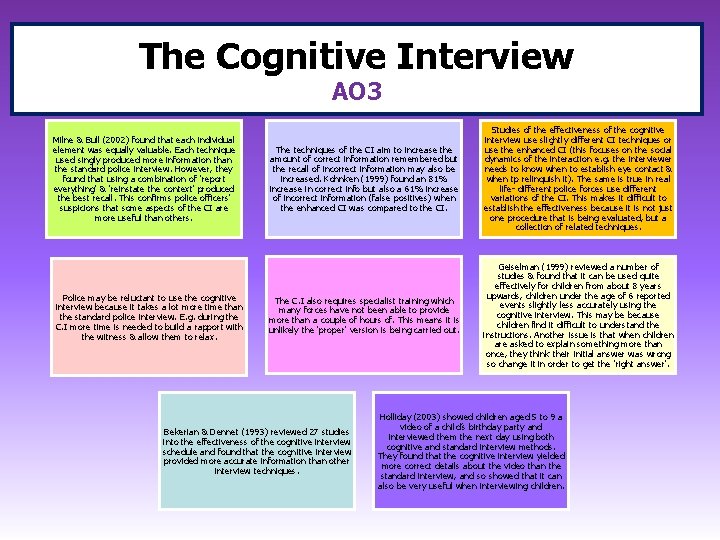

The Cognitive Interview AO 3 Milne & Bull (2002) found that each individual element was equally valuable. Each technique used singly produced more information than the standard police interview. However, they found that using a combination of 'report everything' & 'reinstate the context' produced the best recall. This confirms police officers' suspicions that some aspects of the CI are more useful than others. Police may be reluctant to use the cognitive interview because it takes a lot more time than the standard police interview. E. g. during the C. I more time is needed to build a rapport with the witness & allow them to relax. The techniques of the CI aim to increase the amount of correct information remembered but the recall of incorrect information may also be increased. Kohnken (1999) found an 81% increase in correct info but also a 61% increase of incorrect information (false positives) when the enhanced CI was compared to the CI. Studies of the effectiveness of the cognitive interview use slightly different CI techniques or use the enhanced CI (this focuses on the social dynamics of the interaction e. g. the interviewer needs to know when to establish eye contact & when tp relinquish it). The same is true in real life- different police forces use different variations of the CI. This makes it difficult to establish the effectiveness because it is not just one procedure that is being evaluated, but a collection of related techniques. The C. I also requires specialist training which many forces have not been able to provide more than a couple of hours of. This means it is unlikely the 'proper' version is being carried out. Geiselman (1999) reviewed a number of studies & found that it can be used quite effectively for children from about 8 years upwards, children under the age of 6 reported events slightly less accurately using the cognitive interview. This may be because children find it difficult to understand the instructions. Another issue is that when children are asked to explain something more than once, they think their initial answer was wrong so change it in order to get the 'right answer'. Bekerian & Dennet (1993) reviewed 27 studies into the effectiveness of the cognitive interview schedule and found that the cognitive interview provided more accurate information than other interview techniques. Holliday (2003) showed children aged 5 to 9 a video of a child’s birthday party and interviewed them the next day using both cognitive and standard interview methods. They found that the cognitive interview yielded more correct details about the video than the standard interview, and so showed that it can also be very useful when interviewing children.