AQA A Level Psychology Paper 1 Attachment Specification

- Slides: 38

AQA A Level Psychology Paper 1: Attachment

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • Stages of attachment as identified by Schaffer. • Multiple Attachments

What is Attachment? Attachment can be described as a strong emotional bond that develops over time between an infant and their primary caregiver. It is reciprocal and characterised by mutual affection and a desire to maintain proximity.

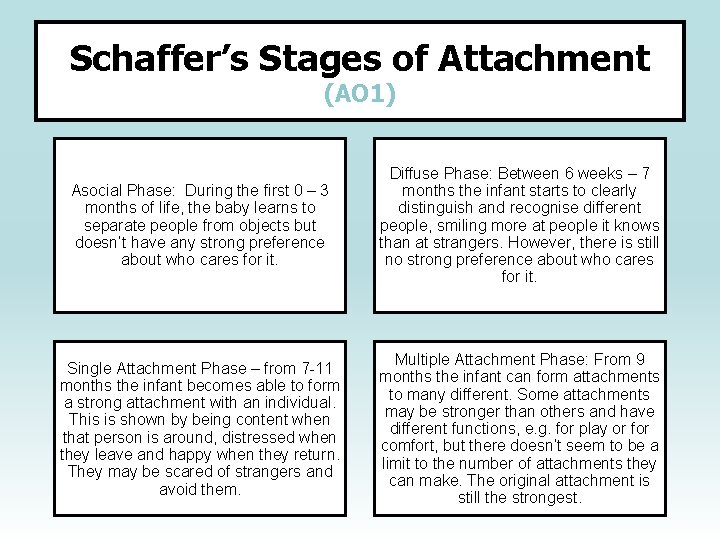

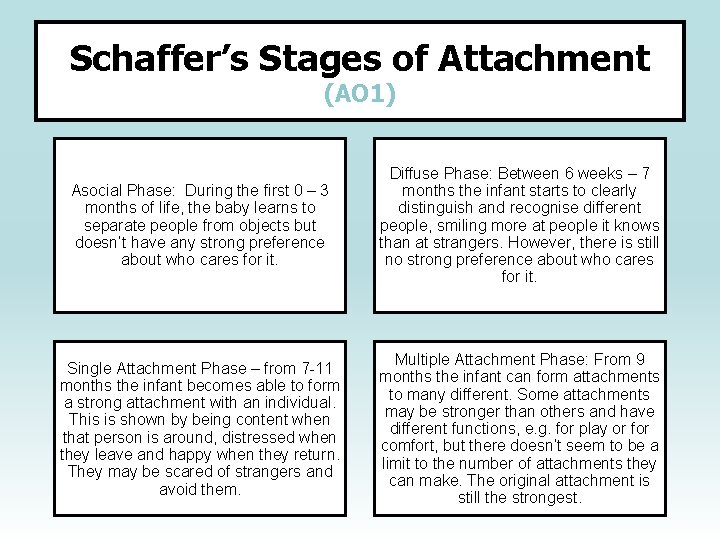

Schaffer’s Stages of Attachment (AO 1) Asocial Phase: During the first 0 – 3 months of life, the baby learns to separate people from objects but doesn’t have any strong preference about who cares for it. Diffuse Phase: Between 6 weeks – 7 months the infant starts to clearly distinguish and recognise different people, smiling more at people it knows than at strangers. However, there is still no strong preference about who cares for it. Single Attachment Phase – from 7 -11 months the infant becomes able to form a strong attachment with an individual. This is shown by being content when that person is around, distressed when they leave and happy when they return. They may be scared of strangers and avoid them. Multiple Attachment Phase: From 9 months the infant can form attachments to many different. Some attachments may be stronger than others and have different functions, e. g. for play or for comfort, but there doesn’t seem to be a limit to the number of attachments they can make. The original attachment is still the strongest.

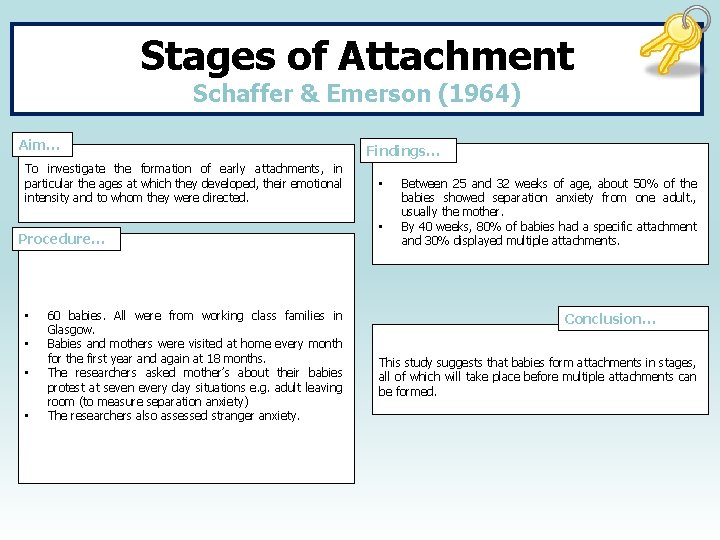

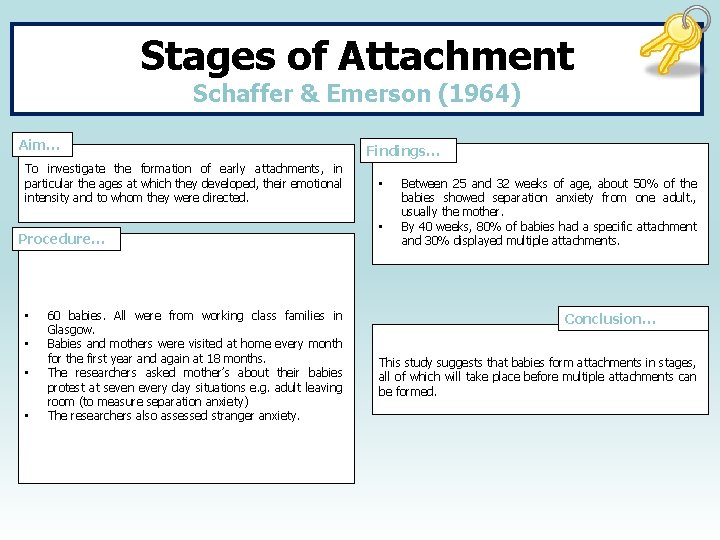

Stages of Attachment Schaffer & Emerson (1964) Aim… To investigate the formation of early attachments, in particular the ages at which they developed, their emotional intensity and to whom they were directed. Procedure… • • 60 babies. All were from working class families in Glasgow. Babies and mothers were visited at home every month for the first year and again at 18 months. The researchers asked mother’s about their babies protest at seven every day situations e. g. adult leaving room (to measure separation anxiety) The researchers also assessed stranger anxiety. Findings… • • Between 25 and 32 weeks of age, about 50% of the babies showed separation anxiety from one adult. , usually the mother. By 40 weeks, 80% of babies had a specific attachment and 30% displayed multiple attachments. Conclusion… This study suggests that babies form attachments in stages, all of which will take place before multiple attachments can be formed.

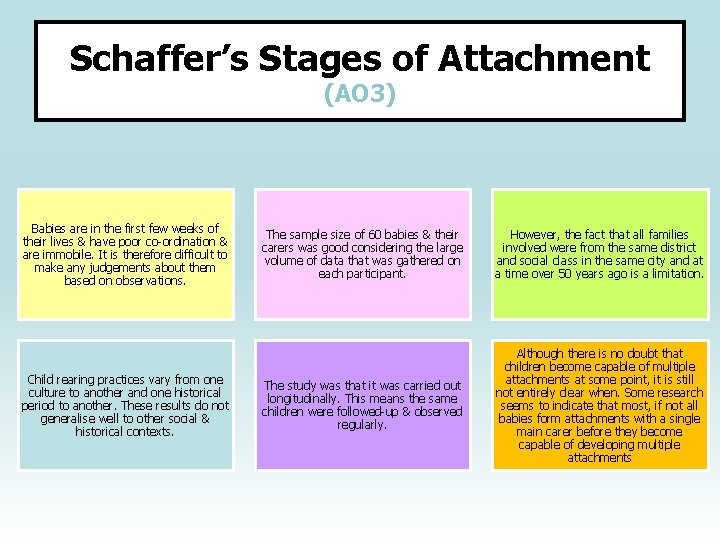

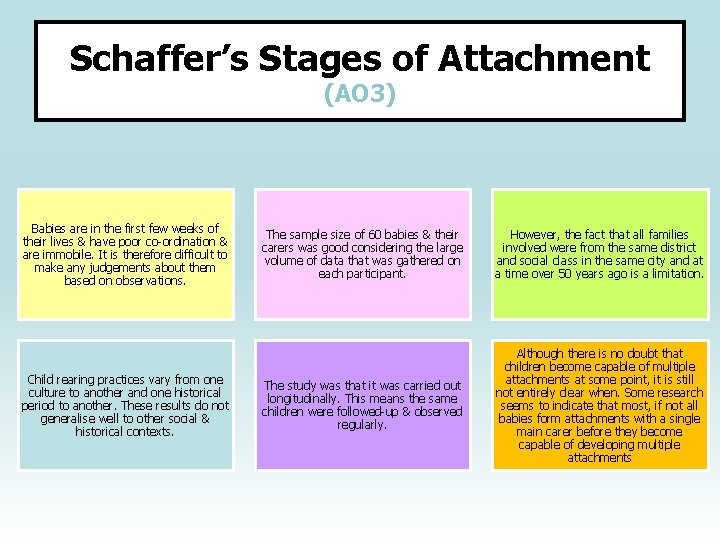

Schaffer’s Stages of Attachment (AO 3) Babies are in the first few weeks of their lives & have poor co-ordination & are immobile. It is therefore difficult to make any judgements about them based on observations. Child rearing practices vary from one culture to another and one historical period to another. These results do not generalise well to other social & historical contexts. The sample size of 60 babies & their carers was good considering the large volume of data that was gathered on each participant. However, the fact that all families involved were from the same district and social class in the same city and at a time over 50 years ago is a limitation. The study was that it was carried out longitudinally. This means the same children were followed-up & observed regularly. Although there is no doubt that children become capable of multiple attachments at some point, it is still not entirely clear when. Some research seems to indicate that most, if not all babies form attachments with a single main carer before they become capable of developing multiple attachments

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • Ainsworth’s ‘Strange Situation’ • Types of attachment: secure, insecureavoidant and insecure resistant.

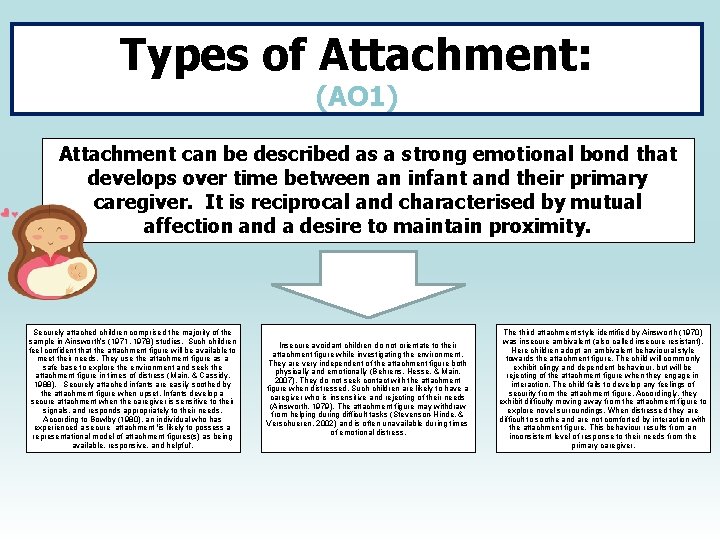

Types of Attachment: (AO 1) Attachment can be described as a strong emotional bond that develops over time between an infant and their primary caregiver. It is reciprocal and characterised by mutual affection and a desire to maintain proximity. Securely attached children comprised the majority of the sample in Ainsworth’s (1971, 1978) studies. Such children feel confident that the attachment figure will be available to meet their needs. They use the attachment figure as a safe base to explore the environment and seek the attachment figure in times of distress (Main, & Cassidy, 1988). Securely attached infants are easily soothed by the attachment figure when upset. Infants develop a secure attachment when the caregiver is sensitive to their signals, and responds appropriately to their needs. According to Bowlby (1980), an individual who has experienced a secure attachment 'is likely to possess a representational model of attachment figures(s) as being available, responsive, and helpful‘. Insecure avoidant children do not orientate to their attachment figure while investigating the environment. They are very independent of the attachment figure both physically and emotionally (Behrens, Hesse, & Main, 2007). They do not seek contact with the attachment figure when distressed. Such children are likely to have a caregiver who is insensitive and rejecting of their needs (Ainsworth, 1979). The attachment figure may withdraw from helping during difficult tasks (Stevenson-Hinde, & Verschueren, 2002) and is often unavailable during times of emotional distress. The third attachment style identified by Ainsworth (1970) was insecure ambivalent (also called insecure resistant). Here children adopt an ambivalent behavioural style towards the attachment figure. The child will commonly exhibit clingy and dependent behaviour, but will be rejecting of the attachment figure when they engage in interaction. The child fails to develop any feelings of security from the attachment figure. Accordingly, they exhibit difficulty moving away from the attachment figure to explore novel surroundings. When distressed they are difficult to soothe and are not comforted by interaction with the attachment figure. This behaviour results from an inconsistent level of response to their needs from the primary caregiver.

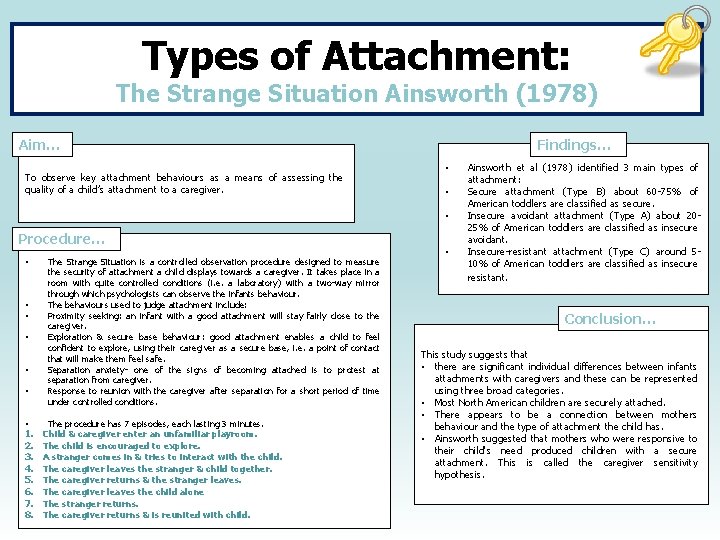

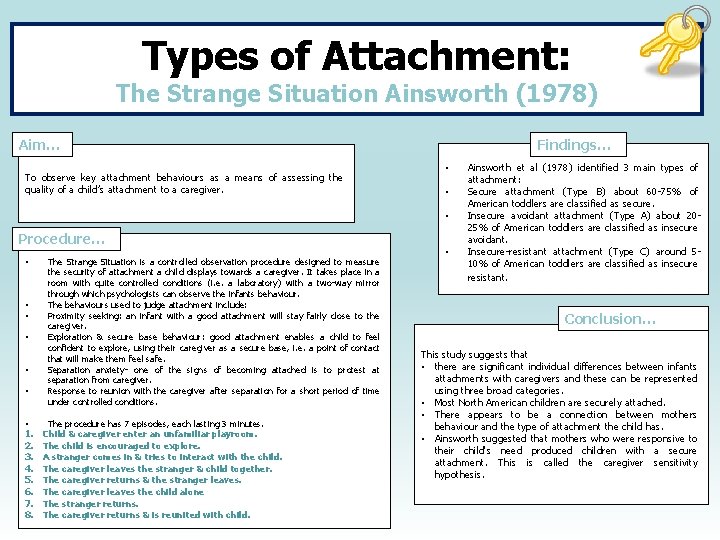

Types of Attachment: The Strange Situation Ainsworth (1978) Aim… To observe key attachment behaviours as a means of assessing the quality of a child’s attachment to a caregiver. Findings… • • • Procedure… • • 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. The Strange Situation is a controlled observation procedure designed to measure the security of attachment a child displays towards a caregiver. It takes place in a room with quite controlled conditions (i. e. a laboratory) with a two-way mirror through which psychologists can observe the infants behaviour. The behaviours used to judge attachment include: Proximity seeking: an infant with a good attachment will stay fairly close to the caregiver. Exploration & secure base behaviour: good attachment enables a child to feel confident to explore, using their caregiver as a secure base, i. e. a point of contact that will make them feel safe. Separation anxiety- one of the signs of becoming attached is to protest at separation from caregiver. Response to reunion with the caregiver after separation for a short period of time under controlled conditions. The procedure has 7 episodes, each lasting 3 minutes. Child & caregiver enter an unfamiliar playroom. The child is encouraged to explore. A stranger comes in & tries to interact with the child. The caregiver leaves the stranger & child together. The caregiver returns & the stranger leaves. The caregiver leaves the child alone The stranger returns. The caregiver returns & is reunited with child. • Ainsworth et al (1978) identified 3 main types of attachment: Secure attachment (Type B) about 60 -75% of American toddlers are classified as secure. Insecure avoidant attachment (Type A) about 2025% of American toddlers are classified as insecure avoidant. Insecure-resistant attachment (Type C) around 510% of American toddlers are classified as insecure resistant. Conclusion… This study suggests that • there are significant individual differences between infants attachments with caregivers and these can be represented using three broad categories. • Most North American children are securely attached. • There appears to be a connection between mothers behaviour and the type of attachment the child has. • Ainsworth suggested that mothers who were responsive to their child's need produced children with a secure attachment. This is called the caregiver sensitivity hypothesis.

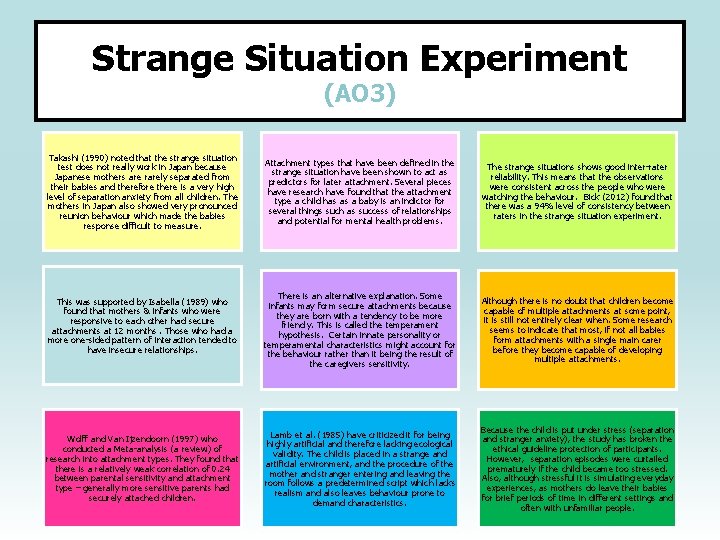

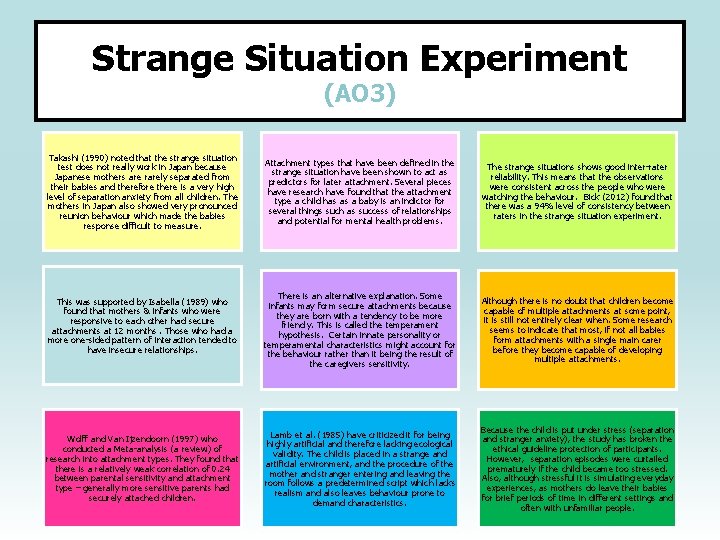

Strange Situation Experiment (AO 3) Takashi (1990) noted that the strange situation test does not really work in Japan because Japanese mothers are rarely separated from their babies and therefore there is a very high level of separation anxiety from all children. The mothers in Japan also showed very pronounced reunion behaviour which made the babies response difficult to measure. Attachment types that have been defined in the strange situation have been shown to act as predictors for later attachment. Several pieces have research have found that the attachment type a child has as a baby is an indictor for several things such as success of relationships and potential for mental health problems. The strange situations shows good inter-rater reliability. This means that the observations were consistent across the people who were watching the behaviour. Bick (2012) found that there was a 94% level of consistency between raters in the strange situation experiment. This was supported by Isabella (1989) who found that mothers & infants who were responsive to each other had secure attachments at 12 months. Those who had a more one-sided pattern of interaction tended to have insecure relationships. There is an alternative explanation. Some infants may form secure attachments because they are born with a tendency to be more friendly. This is called the temperament hypothesis. Certain innate personality or temperamental characteristics might account for the behaviour rather than it being the result of the caregivers sensitivity. Although there is no doubt that children become capable of multiple attachments at some point, it is still not entirely clear when. Some research seems to indicate that most, if not all babies form attachments with a single main carer before they become capable of developing multiple attachments. Wolff and Van Ijzendoorn (1997) who conducted a Meta-analysis (a review) of research into attachment types. They found that there is a relatively weak correlation of 0. 24 between parental sensitivity and attachment type – generally more sensitive parents had securely attached children. Lamb et al. (1985) have criticized it for being highly artificial and therefore lacking ecological validity. The child is placed in a strange and artificial environment, and the procedure of the mother and stranger entering and leaving the room follows a predetermined script which lacks realism and also leaves behaviour prone to demand characteristics. Because the child is put under stress (separation and stranger anxiety), the study has broken the ethical guideline protection of participants. However, separation episodes were curtailed prematurely if the child became too stressed. Also, although stressful it is simulating everyday experiences, as mothers do leave their babies for brief periods of time in different settings and often with unfamiliar people.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • Cultural variations in attachment including Van Ijzendoorn.

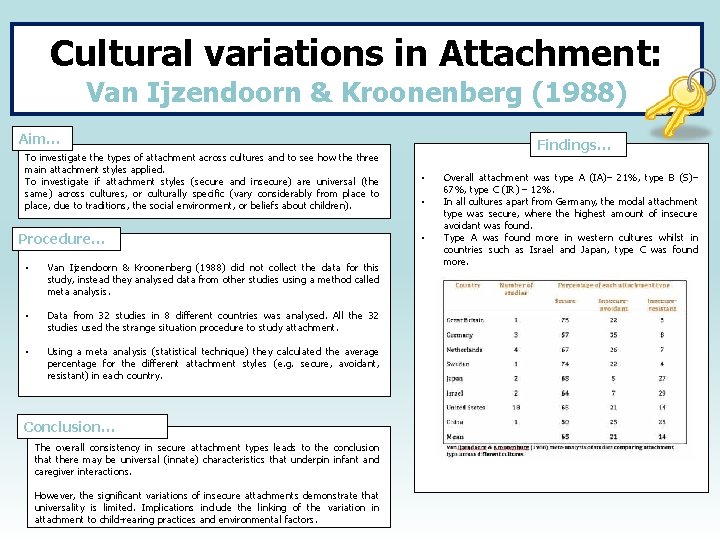

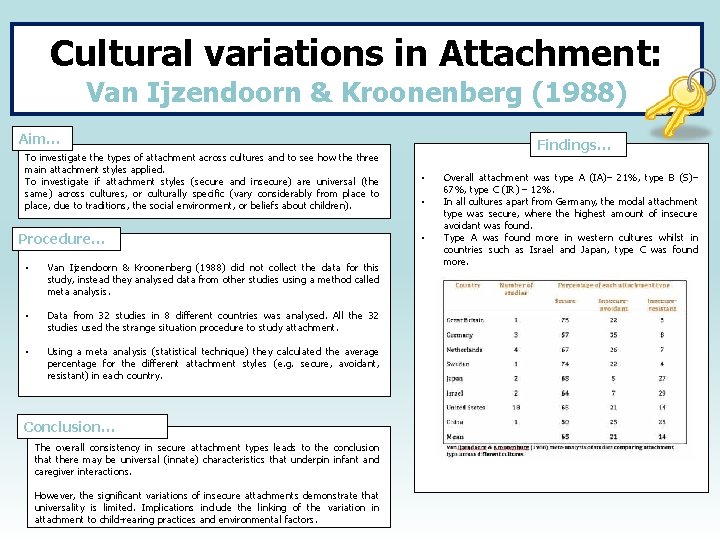

Cultural variations in Attachment: Van Ijzendoorn & Kroonenberg (1988) Aim… To investigate the types of attachment across cultures and to see how the three main attachment styles applied. To investigate if attachment styles (secure and insecure) are universal (the same) across cultures, or culturally specific (vary considerably from place to place, due to traditions, the social environment, or beliefs about children). Procedure… • Van Ijzendoorn & Kroonenberg (1988) did not collect the data for this study, instead they analysed data from other studies using a method called meta analysis. • Data from 32 studies in 8 different countries was analysed. All the 32 studies used the strange situation procedure to study attachment. • Using a meta analysis (statistical technique) they calculated the average percentage for the different attachment styles (e. g. secure, avoidant, resistant) in each country. Conclusion… The overall consistency in secure attachment types leads to the conclusion that there may be universal (innate) characteristics that underpin infant and caregiver interactions. However, the significant variations of insecure attachments demonstrate that universality is limited. Implications include the linking of the variation in attachment to child-rearing practices and environmental factors. Findings… • • • Overall attachment was type A (IA)– 21%, type B (S)– 67%, type C (IR) – 12%. In all cultures apart from Germany, the modal attachment type was secure, where the highest amount of insecure avoidant was found. Type A was found more in western cultures whilst in countries such as Israel and Japan, type C was found more.

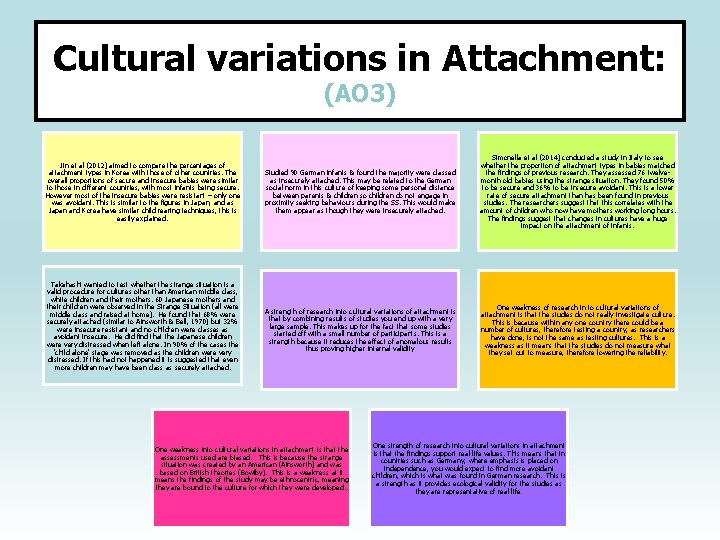

Cultural variations in Attachment: (AO 3) Jin et al (2012) aimed to compare the percentages of attachment types in Korea with those of other countries. The overall proportions of secure and insecure babies were similar to those in different countries, with most infants being secure. However most of the insecure babies were resistant – only one was avoidant. This is similar to the figures in Japan, and as Japan and Korea have similar child rearing techniques, this is easily explained. Takahashi wanted to test whether the strange situation is a valid procedure for cultures other than American middle class, white children and their mothers. 60 Japanese mothers and their children were observed in the Strange Situation (all were middle class and raised at home). He found that 68% were securely attached (similar to Ainsworth & Bell, 1970) but 32% were insecure resistant and no children were classes as avoidant insecure. He did find that the Japanese children were very distressed when left alone. In 90% of the cases the 'child alone' stage was removed as the children were very distressed. If this had not happened it is suggested that even more children may have been class as securely attached. Studied 90 German infants & found the majority were classed as insecurely attached. This may be related to the German social norm in this culture of keeping some personal distance between parents & children so children do not engage in proximity seeking behaviours during the SS. This would make them appear as though they were insecurely attached. Simonella et al (2014) conducted a study in Italy to see whether the proportion of attachment types in babies matched the findings of previous research. They assessed 76 twelvemonth old babies using the strange situation. They found 50% to be secure and 36% to be insecure avoidant. This is a lower rate of secure attachment than has been found in previous studies. The researchers suggest that this correlates with the amount of children who now have mothers working long hours. The findings suggest that changes in cultures have a huge impact on the attachment of infants. A strength of research into cultural variations of attachment is that by combining results of studies you end up with a very large sample. This makes up for the fact that some studies started off with a small number of participants. This is a strength because it reduces the effect of anomalous results thus proving higher internal validity One weakness of research in to cultural variations of attachment is that the studies do not really investigate culture. This is because within any one country there could be a number of cultures, therefore testing a country, as researchers have done, is not the same as testing cultures. This is a weakness as it means that the studies do not measure what they set out to measure, therefore lowering the reliability. One weakness into cultural variations in attachment is that the assessments used are biased. This is because the strange situation was created by an American (Ainsworth) and was based on British theories (Bowlby). This is a weakness at it means the findings of the study may be ethnocentric, meaning they are bound to the culture for which they were developed. . One strength of research into cultural variations in attachment is that the findings support real life values. This means that in countries such as Germany, where emphasis is placed on independence, you would expect to find more avoidant children; which is what was found in German research. This is a strength as it provides ecological validity for the studies as they are representative of real life.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • Caregiver-infant interactions in humans: reciprocity and interactional synchrony. • The role of the Father

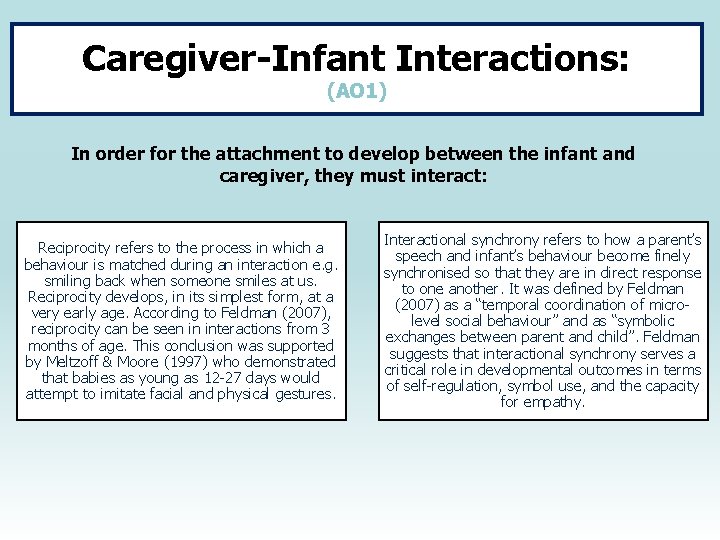

Caregiver-Infant Interactions: (AO 1) In order for the attachment to develop between the infant and caregiver, they must interact: Reciprocity refers to the process in which a behaviour is matched during an interaction e. g. smiling back when someone smiles at us. Reciprocity develops, in its simplest form, at a very early age. According to Feldman (2007), reciprocity can be seen in interactions from 3 months of age. This conclusion was supported by Meltzoff & Moore (1997) who demonstrated that babies as young as 12 -27 days would attempt to imitate facial and physical gestures. Interactional synchrony refers to how a parent’s speech and infant’s behaviour become finely synchronised so that they are in direct response to one another. It was defined by Feldman (2007) as a “temporal coordination of microlevel social behaviour” and as “symbolic exchanges between parent and child”. Feldman suggests that interactional synchrony serves a critical role in developmental outcomes in terms of self-regulation, symbol use, and the capacity for empathy.

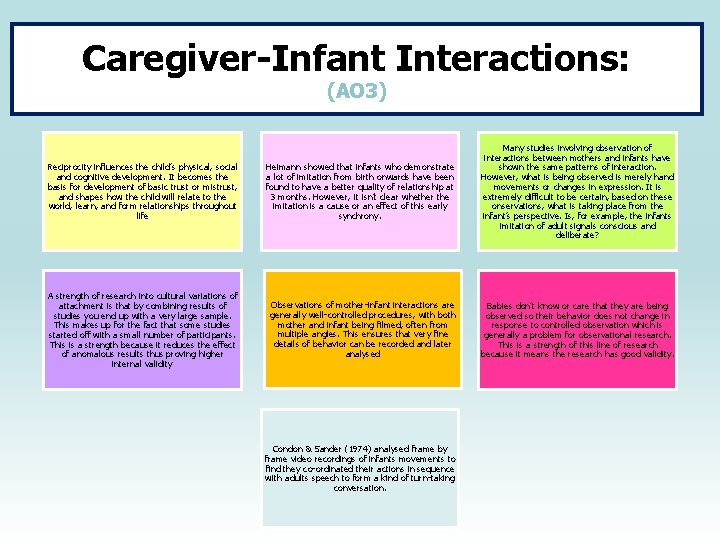

Caregiver-Infant Interactions: (AO 3) Reciprocity influences the child’s physical, social and cognitive development. It becomes the basis for development of basic trust or mistrust, and shapes how the child will relate to the world, learn, and form relationships throughout life Heimann showed that infants who demonstrate a lot of imitation from birth onwards have been found to have a better quality of relationship at 3 months. However, it isn’t clear whether the imitation is a cause or an effect of this early synchrony. Many studies involving observation of interactions between mothers and infants have shown the same patterns of interaction. However, what is being observed is merely hand movements or changes in expression. It is extremely difficult to be certain, based on these onservations, what is taking place from the infant’s perspective. Is, for example, the infants imitation of adult signals conscious and deliberate? A strength of research into cultural variations of attachment is that by combining results of studies you end up with a very large sample. This makes up for the fact that some studies started off with a small number of participants. This is a strength because it reduces the effect of anomalous results thus proving higher internal validity Observations of mother-infant interactions are generally well-controlled procedures, with both mother and infant being filmed, often from multiple angles. This ensures that very fine details of behavior can be recorded and later analysed Babies don’t know or care that they are being observed so their behavior does not change in response to controlled observation which is generally a problem for observational research. This is a strength of this line of research because it means the research has good validity. Condon & Sander (1974) analysed frame by frame video recordings of infants movements to find they co-ordinated their actions in sequence with adults speech to form a kind of turn-taking conversation.

The Role of the Father: (AO 1) • There is now an expectation in Western cultures that the father should play a greater role in bringing up children than was previously the case. • Also, the number of mothers working full time has increased in recent decades, and this has also led to fathers having a more active role. • Bowlby suggests that fathers can fill a role closely resembling that filled by a mother but points out that in most cultures this is uncommon. Bowlby argues that in most families with young children, the father's role tends to be different. • However, whereas mothers usually adopt a more caregiving and nurturing role compared to father, fathers adopt a more play-mate role than mothers. For example, fathers are more likely than mothers to encourage risk taking in their children by engaging them in physical games. • Most infants prefer contact with their father when in a positive emotional state and wanting to play. In contrast most infants prefer contact with their mother when they are distressed and need comforting. • According to Bowlby, a father is more likely to engage in physically active and novel play than the mother and tends to become his child's preferred play companion.

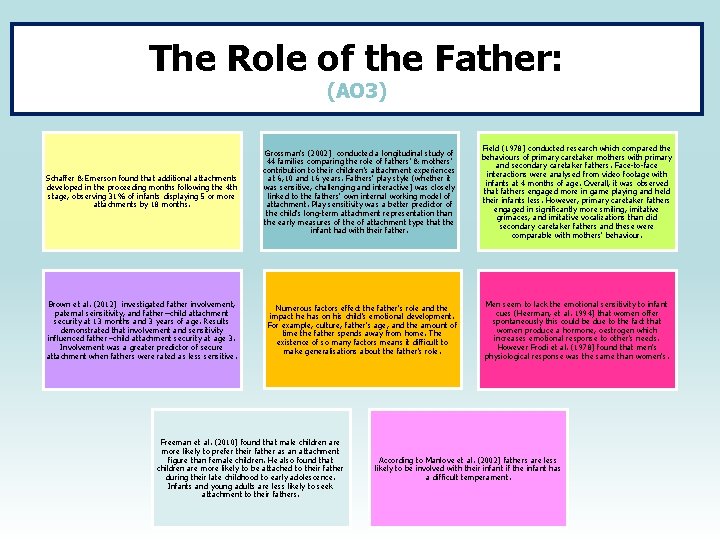

The Role of the Father: (AO 3) Schaffer & Emerson found that additional attachments developed in the proceeding months following the 4 th stage, observing 31% of infants displaying 5 or more attachments by 18 months. Grossman’s (2002) conducted a longitudinal study of 44 families comparing the role of fathers’ & mothers’ contribution to their children's attachment experiences at 6, 10 and 16 years. Fathers’ play style (whether it was sensitive, challenging and interactive) was closely linked to the fathers’ own internal working model of attachment. Play sensitivity was a better predictor of the child's long-term attachment representation than the early measures of the of attachment type that the infant had with their father. Brown et al. (2012) investigated father involvement, paternal seinsitivity, and father−child attachment security at 13 months and 3 years of age. Results demonstrated that involvement and sensitivity influenced father−child attachment security at age 3. Involvement was a greater predictor of secure attachment when fathers were rated as less sensitive. Numerous factors effect the father's role and the impact he has on his child's emotional development. For example, culture, father's age, and the amount of time the father spends away from home. The existence of so many factors means it difficult to make generalisations about the father's role. Freeman et al. (2010) found that male children are more likely to prefer their father as an attachment figure than female children. He also found that children are more likely to be attached to their father during their late childhood to early adolescence. Infants and young adults are less likely to seek attachment to their fathers. Field (1978) conducted research which compared the behaviours of primary caretaker mothers with primary and secondary caretaker fathers. Face-to-face interactions were analysed from video footage with infants at 4 months of age. Overall, it was observed that fathers engaged more in game playing and held their infants less. However, primary caretaker fathers engaged in significantly more smiling, imitative grimaces, and imitative vocalizations than did secondary caretaker fathers and these were comparable with mothers’ behaviour. Men seem to lack the emotional sensitivity to infant cues (Heerman, et al. 1994) that women offer spontaneously this could be due to the fact that women produce a hormone, oestrogen which increases emotional response to other’s needs. However Frodi et al. (1978) found that men’s physiological response was the same than women’s. According to Manlove et al. (2002) fathers are less likely to be involved with their infant if the infant has a difficult temperament.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… Explanations of attachment: • Bowlby’s Monotropic Theory. • The concepts of a critical period an internal working model. • Learning Theory • Animal Studies

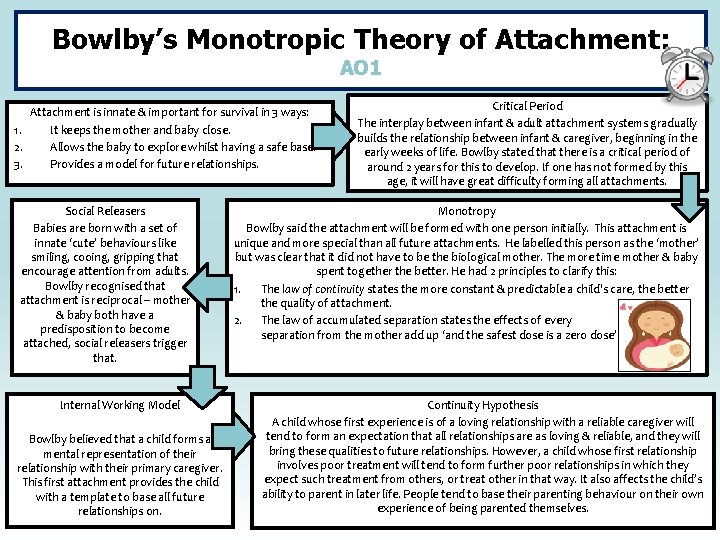

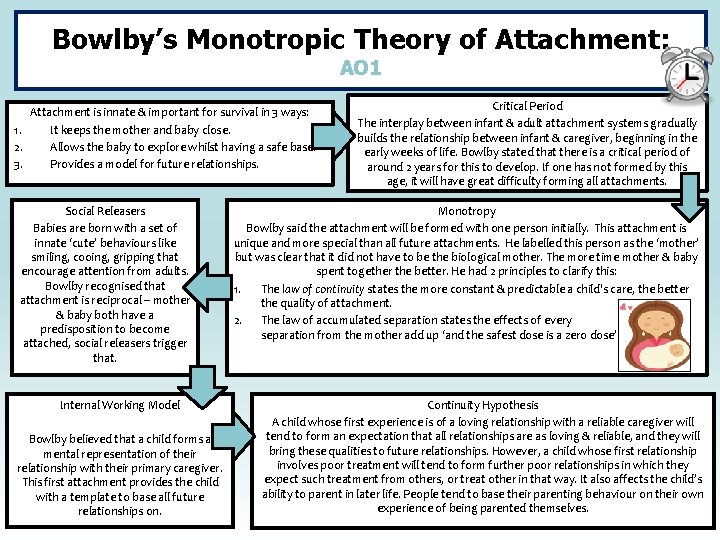

Bowlby’s Monotropic Theory of Attachment: AO 1 Attachment is innate & important for survival in 3 ways: 1. It keeps the mother and baby close. 2. Allows the baby to explore whilst having a safe base. 3. Provides a model for future relationships. Social Releasers Babies are born with a set of innate ‘cute’ behaviours like smiling, cooing, gripping that encourage attention from adults. Bowlby recognised that attachment is reciprocal – mother & baby both have a predisposition to become attached, social releasers trigger that. Internal Working Model Bowlby believed that a child forms a mental representation of their relationship with their primary caregiver. This first attachment provides the child with a template to base all future relationships on. Critical Period The interplay between infant & adult attachment systems gradually builds the relationship between infant & caregiver, beginning in the early weeks of life. Bowlby stated that there is a critical period of around 2 years for this to develop. If one has not formed by this age, it will have great difficulty forming all attachments. Monotropy Bowlby said the attachment will be formed with one person initially. This attachment is unique and more special than all future attachments. He labelled this person as the ‘mother’ but was clear that it did not have to be the biological mother. The more time mother & baby spent together the better. He had 2 principles to clarify this: 1. The law of continuity states the more constant & predictable a child's care, the better the quality of attachment. 2. The law of accumulated separation states the effects of every separation from the mother add up ‘and the safest dose is a zero dose’. Continuity Hypothesis A child whose first experience is of a loving relationship with a reliable caregiver will tend to form an expectation that all relationships are as loving & reliable, and they will bring these qualities to future relationships. However, a child whose first relationship involves poor treatment will tend to form further poor relationships in which they expect such treatment from others, or treat other in that way. It also affects the child’s ability to parent in later life. People tend to base their parenting behaviour on their own experience of being parented themselves.

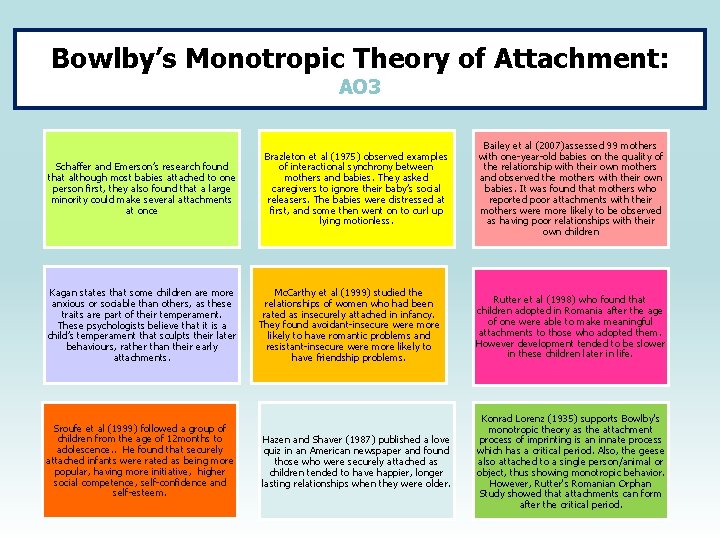

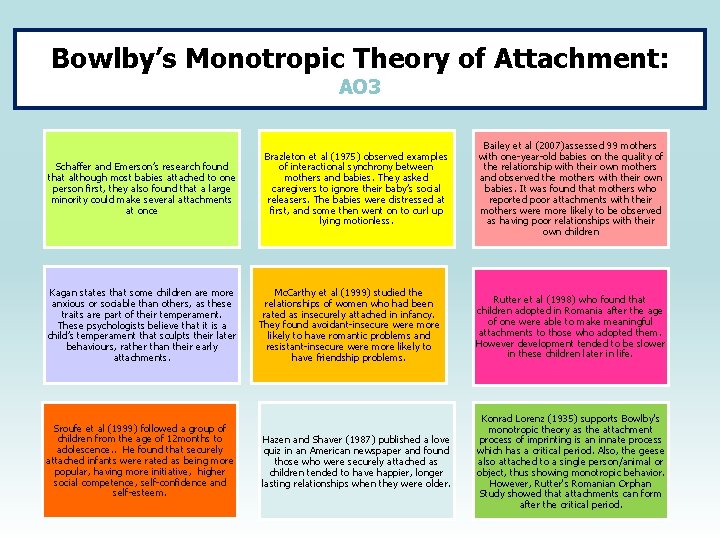

Bowlby’s Monotropic Theory of Attachment: AO 3 Schaffer and Emerson’s research found that although most babies attached to one person first, they also found that a large minority could make several attachments at once Kagan states that some children are more anxious or sociable than others, as these traits are part of their temperament. These psychologists believe that it is a child’s temperament that sculpts their later behaviours, rather than their early attachments. Sroufe et al (1999) followed a group of children from the age of 12 months to adolescence. . He found that securely attached infants were rated as being more popular, having more initiative, higher social competence, self-confidence and self-esteem. Brazleton et al (1975) observed examples of interactional synchrony between mothers and babies. They asked caregivers to ignore their baby’s social releasers. The babies were distressed at first, and some then went on to curl up lying motionless. Mc. Carthy et al (1999) studied the relationships of women who had been rated as insecurely attached in infancy. They found avoidant-insecure were more likely to have romantic problems and resistant-insecure were more likely to have friendship problems. Hazen and Shaver (1987) published a love quiz in an American newspaper and found those who were securely attached as children tended to have happier, longer lasting relationships when they were older. Bailey et al (2007)assessed 99 mothers with one-year-old babies on the quality of the relationship with their own mothers and observed the mothers with their own babies. It was found that mothers who reported poor attachments with their mothers were more likely to be observed as having poor relationships with their own children Rutter et al (1998) who found that children adopted in Romania after the age of one were able to make meaningful attachments to those who adopted them. However development tended to be slower in these children later in life. Konrad Lorenz (1935) supports Bowlby's monotropic theory as the attachment process of imprinting is an innate process which has a critical period. Also, the geese also attached to a single person/animal or object, thus showing monotropic behavior. However, Rutter's Romanian Orphan Study showed that attachments can form after the critical period.

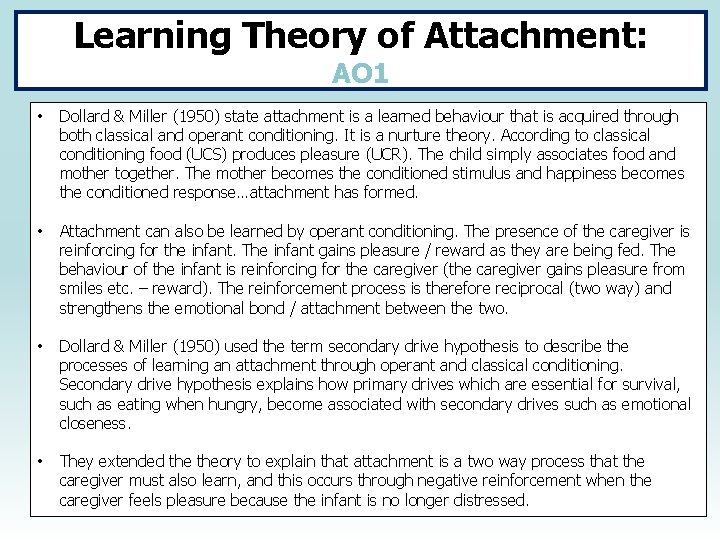

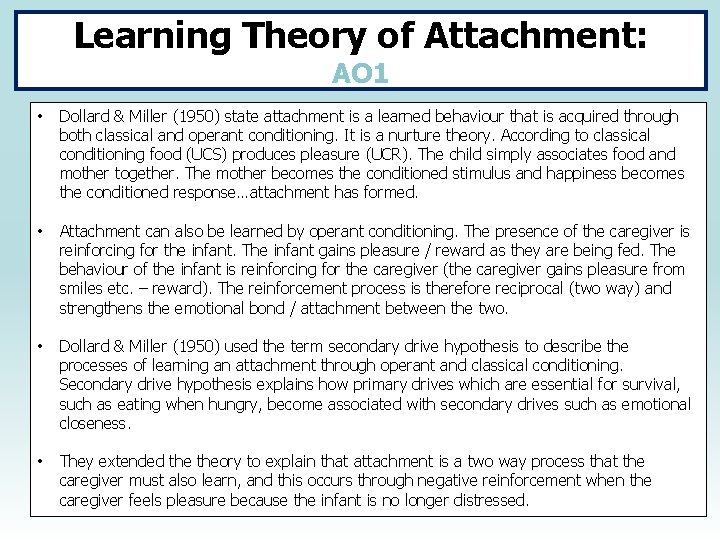

Learning Theory of Attachment: AO 1 • Dollard & Miller (1950) state attachment is a learned behaviour that is acquired through both classical and operant conditioning. It is a nurture theory. According to classical conditioning food (UCS) produces pleasure (UCR). The child simply associates food and mother together. The mother becomes the conditioned stimulus and happiness becomes the conditioned response…attachment has formed. • Attachment can also be learned by operant conditioning. The presence of the caregiver is reinforcing for the infant. The infant gains pleasure / reward as they are being fed. The behaviour of the infant is reinforcing for the caregiver (the caregiver gains pleasure from smiles etc. – reward). The reinforcement process is therefore reciprocal (two way) and strengthens the emotional bond / attachment between the two. • Dollard & Miller (1950) used the term secondary drive hypothesis to describe the processes of learning an attachment through operant and classical conditioning. Secondary drive hypothesis explains how primary drives which are essential for survival, such as eating when hungry, become associated with secondary drives such as emotional closeness. • They extended theory to explain that attachment is a two way process that the caregiver must also learn, and this occurs through negative reinforcement when the caregiver feels pleasure because the infant is no longer distressed.

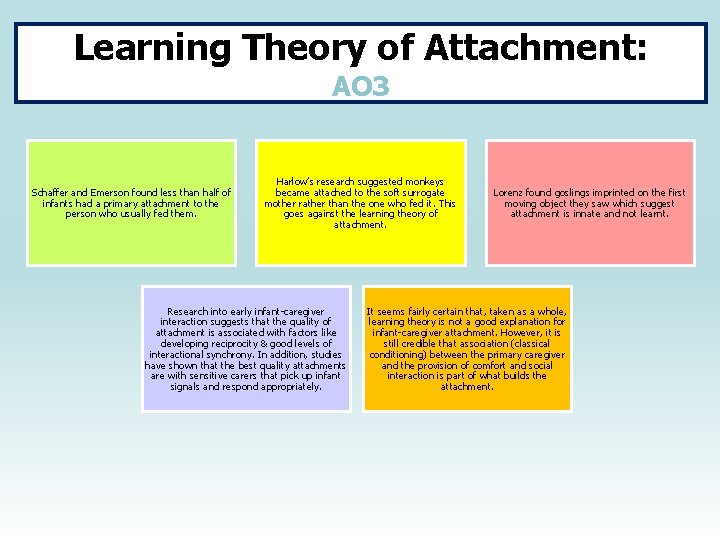

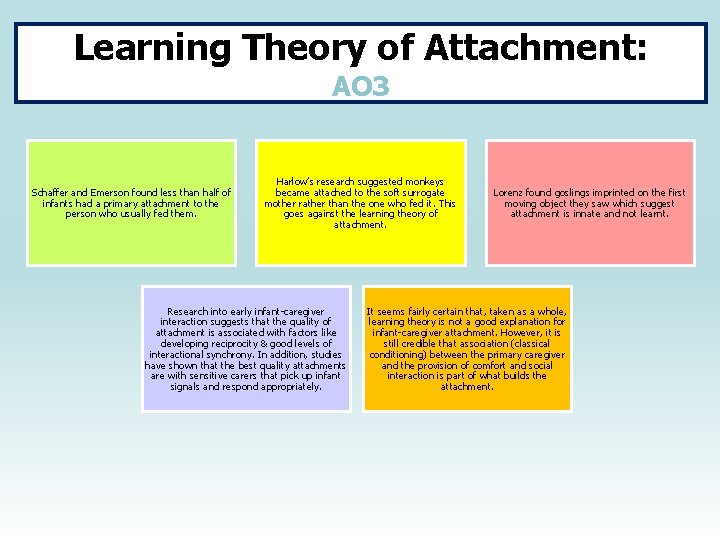

Learning Theory of Attachment: AO 3 Schaffer and Emerson found less than half of infants had a primary attachment to the person who usually fed them. Harlow’s research suggested monkeys became attached to the soft surrogate mother rather than the one who fed it. This goes against the learning theory of attachment. Research into early infant-caregiver interaction suggests that the quality of attachment is associated with factors like developing reciprocity & good levels of interactional synchrony. In addition, studies have shown that the best quality attachments are with sensitive carers that pick up infant signals and respond appropriately. Lorenz found goslings imprinted on the first moving object they saw which suggest attachment is innate and not learnt. It seems fairly certain that, taken as a whole, learning theory is not a good explanation for infant-caregiver attachment. However, it is still credible that association (classical conditioning) between the primary caregiver and the provision of comfort and social interaction is part of what builds the attachment.

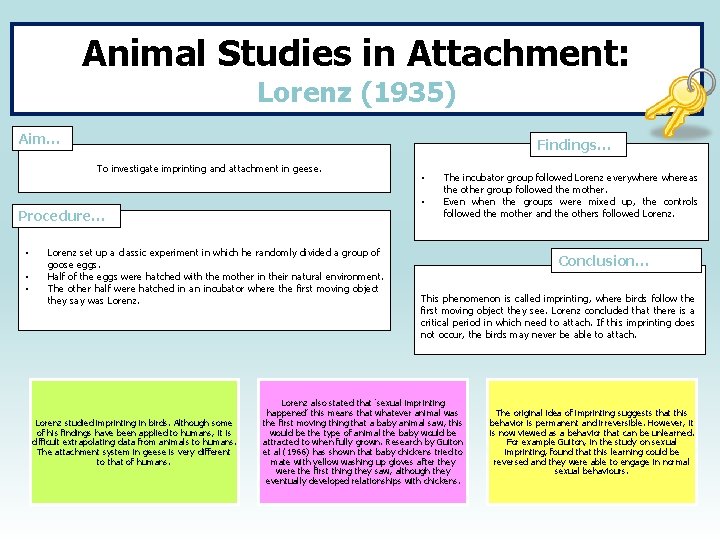

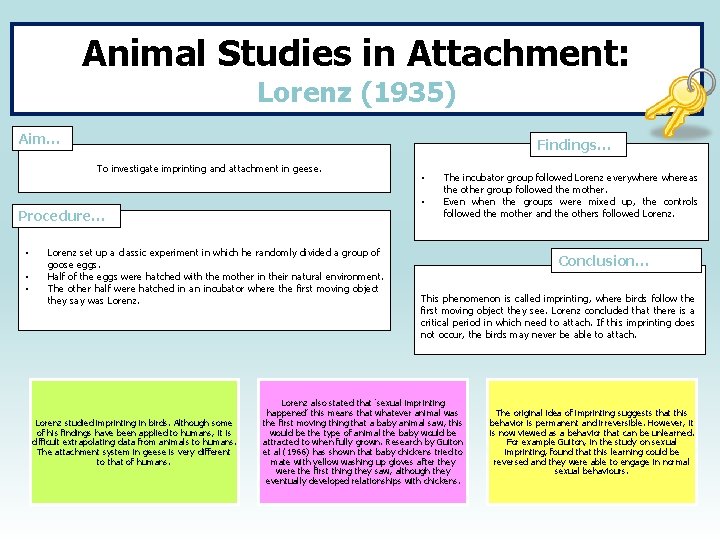

Animal Studies in Attachment: Lorenz (1935) Aim… Findings… To investigate imprinting and attachment in geese. • • Procedure… • • • Lorenz set up a classic experiment in which he randomly divided a group of goose eggs. Half of the eggs were hatched with the mother in their natural environment. The other half were hatched in an incubator where the first moving object they say was Lorenz studied imprinting in birds. Although some of his findings have been applied to humans, it is difficult extrapolating data from animals to humans. The attachment system in geese is very different to that of humans. The incubator group followed Lorenz everywhereas the other group followed the mother. Even when the groups were mixed up, the controls followed the mother and the others followed Lorenz. Conclusion… This phenomenon is called imprinting, where birds follow the first moving object they see. Lorenz concluded that there is a critical period in which need to attach. If this imprinting does not occur, the birds may never be able to attach. Lorenz also stated that ‘sexual imprinting happened’ this means that whatever animal was the first moving that a baby animal saw, this would be the type of animal the baby would be attracted to when fully grown. Research by Guiton et al (1966) has shown that baby chickens tried to mate with yellow washing up gloves after they were the first thing they saw, although they eventually developed relationships with chickens. The original idea of imprinting suggests that this behavior is permanent and irreversible. However, it is now viewed as a behavior that can be unlearned. For example Guiton, in the study on sexual imprinting, found that this learning could be reversed and they were able to engage in normal sexual behaviours.

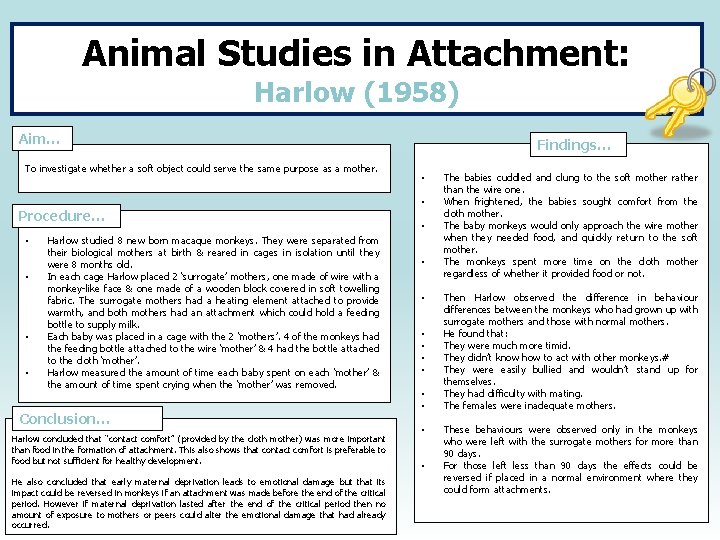

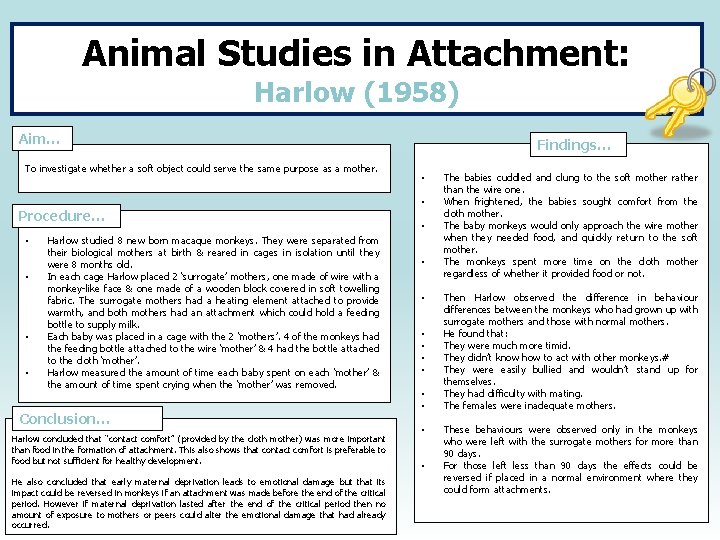

Animal Studies in Attachment: Harlow (1958) Aim… To investigate whether a soft object could serve the same purpose as a mother. Findings… • • Procedure… • • Harlow studied 8 new born macaque monkeys. They were separated from their biological mothers at birth & reared in cages in isolation until they were 8 months old. In each cage Harlow placed 2 ‘surrogate’ mothers, one made of wire with a monkey-like face & one made of a wooden block covered in soft towelling fabric. The surrogate mothers had a heating element attached to provide warmth, and both mothers had an attachment which could hold a feeding bottle to supply milk. Each baby was placed in a cage with the 2 ‘mothers’. 4 of the monkeys had the feeding bottle attached to the wire ‘mother’ & 4 had the bottle attached to the cloth ‘mother’. Harlow measured the amount of time each baby spent on each ‘mother’ & the amount of time spent crying when the ‘mother’ was removed. Conclusion… Harlow concluded that “contact comfort” (provided by the cloth mother) was more important than food in the formation of attachment. This also shows that contact comfort is preferable to food but not sufficient for healthy development. He also concluded that early maternal deprivation leads to emotional damage but that its impact could be reversed in monkeys if an attachment was made before the end of the critical period. However if maternal deprivation lasted after the end of the critical period then no amount of exposure to mothers or peers could alter the emotional damage that had already occurred. • • • The babies cuddled and clung to the soft mother rather than the wire one. When frightened, the babies sought comfort from the cloth mother. The baby monkeys would only approach the wire mother when they needed food, and quickly return to the soft mother. The monkeys spent more time on the cloth mother regardless of whether it provided food or not. Then Harlow observed the difference in behaviour differences between the monkeys who had grown up with surrogate mothers and those with normal mothers. He found that: They were much more timid. They didn’t know how to act with other monkeys. # They were easily bullied and wouldn’t stand up for themselves. They had difficulty with mating. The females were inadequate mothers. These behaviours were observed only in the monkeys who were left with the surrogate mothers for more than 90 days. For those left less than 90 days the effects could be reversed if placed in a normal environment where they could form attachments.

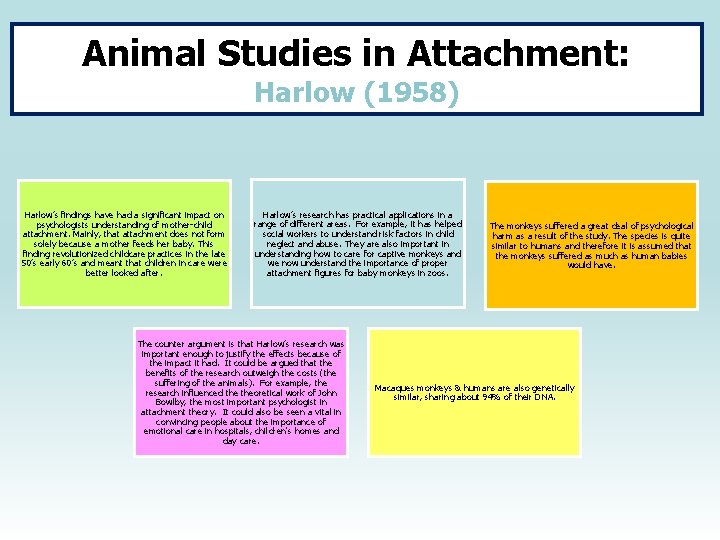

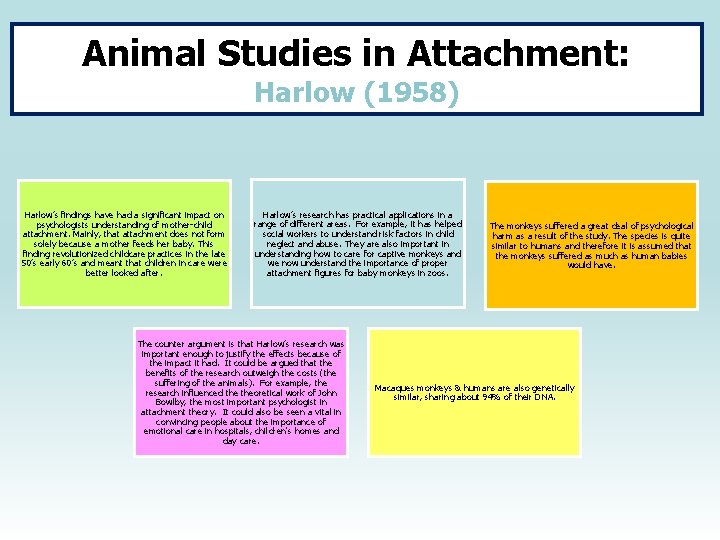

Animal Studies in Attachment: Harlow (1958) Harlow’s findings have had a significant impact on psychologists understanding of mother-child attachment. Mainly, that attachment does not form solely because a mother feeds her baby. This finding revolutionized childcare practices in the late 50’s early 60’s and meant that children in care were better looked after. Harlow’s research has practical applications in a range of different areas. For example, it has helped social workers to understand risk factors in child neglect and abuse. They are also important in understanding how to care for captive monkeys and we now understand the importance of proper attachment figures for baby monkeys in zoos. The counter argument is that Harlow’s research was important enough to justify the effects because of the impact it had. It could be argued that the benefits of the research outweigh the costs (the suffering of the animals). For example, the research influenced theoretical work of John Bowlby, the most important psychologist in attachment theory. It could also be seen a vital in convincing people about the importance of emotional care in hospitals, children's homes and day care. The monkeys suffered a great deal of psychological harm as a result of the study. The species is quite similar to humans and therefore it is assumed that the monkeys suffered as much as human babies would have. Macaques monkeys & humans are also genetically similar, sharing about 94% of their DNA.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… Bowlby’s theory of maternal deprivation.

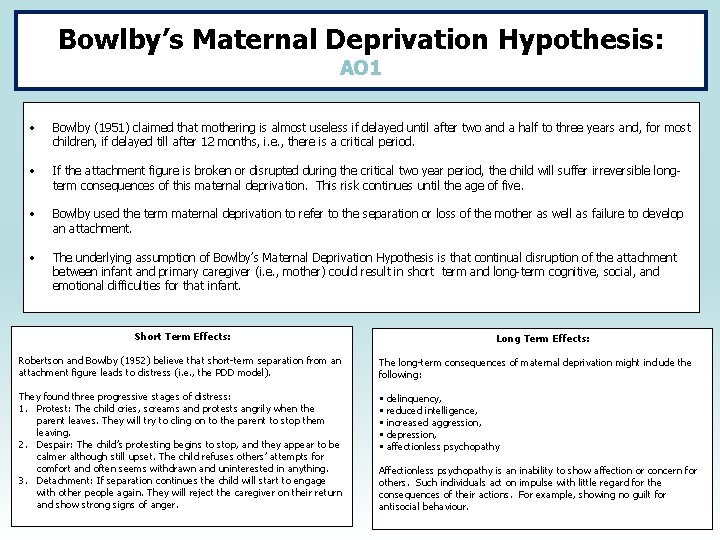

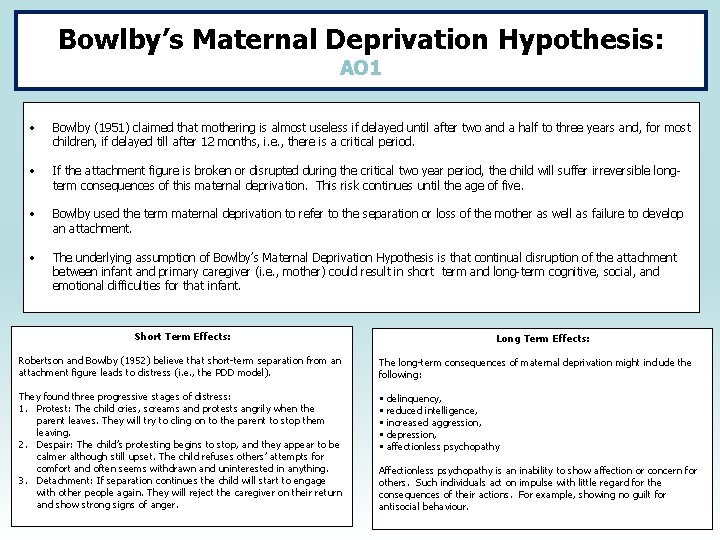

Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis: AO 1 • Bowlby (1951) claimed that mothering is almost useless if delayed until after two and a half to three years and, for most children, if delayed till after 12 months, i. e. , there is a critical period. • If the attachment figure is broken or disrupted during the critical two year period, the child will suffer irreversible longterm consequences of this maternal deprivation. This risk continues until the age of five. • Bowlby used the term maternal deprivation to refer to the separation or loss of the mother as well as failure to develop an attachment. • The underlying assumption of Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis is that continual disruption of the attachment between infant and primary caregiver (i. e. , mother) could result in short term and long-term cognitive, social, and emotional difficulties for that infant. Short Term Effects: Long Term Effects: Robertson and Bowlby (1952) believe that short-term separation from an attachment figure leads to distress (i. e. , the PDD model). The long-term consequences of maternal deprivation might include the following: They found three progressive stages of distress: 1. Protest: The child cries, screams and protests angrily when the parent leaves. They will try to cling on to the parent to stop them leaving. 2. Despair: The child’s protesting begins to stop, and they appear to be calmer although still upset. The child refuses others’ attempts for comfort and often seems withdrawn and uninterested in anything. 3. Detachment: If separation continues the child will start to engage with other people again. They will reject the caregiver on their return and show strong signs of anger. • • • delinquency, reduced intelligence, increased aggression, depression, affectionless psychopathy Affectionless psychopathy is an inability to show affection or concern for others. Such individuals act on impulse with little regard for the consequences of their actions. For example, showing no guilt for antisocial behaviour.

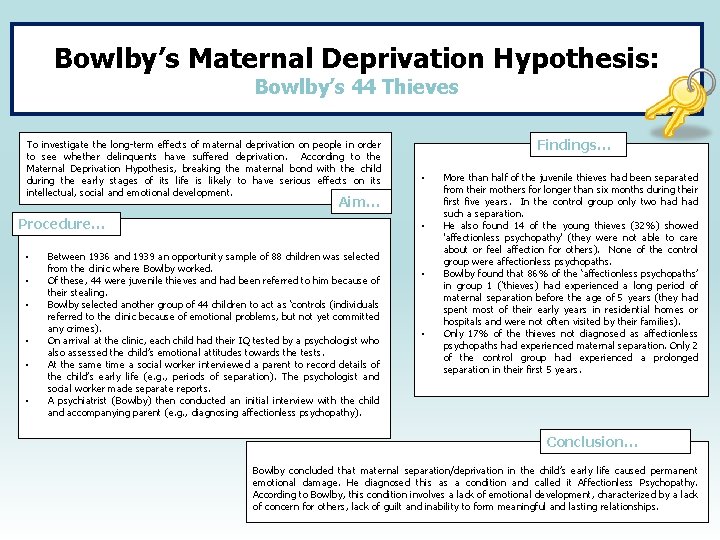

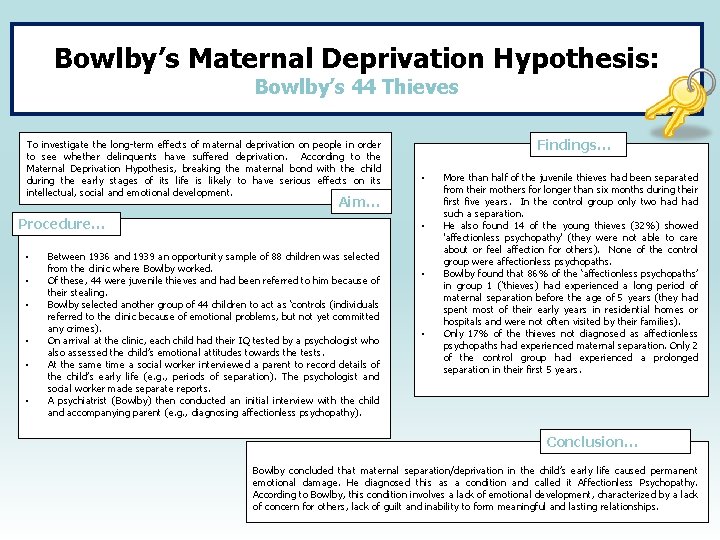

Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis: Bowlby’s 44 Thieves To investigate the long-term effects of maternal deprivation on people in order to see whether delinquents have suffered deprivation. According to the Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis, breaking the maternal bond with the child during the early stages of its life is likely to have serious effects on its intellectual, social and emotional development. Findings… • Aim… Procedure… • • Between 1936 and 1939 an opportunity sample of 88 children was selected from the clinic where Bowlby worked. Of these, 44 were juvenile thieves and had been referred to him because of their stealing. Bowlby selected another group of 44 children to act as ‘controls (individuals referred to the clinic because of emotional problems, but not yet committed any crimes). On arrival at the clinic, each child had their IQ tested by a psychologist who also assessed the child’s emotional attitudes towards the tests. At the same time a social worker interviewed a parent to record details of the child’s early life (e. g. , periods of separation). The psychologist and social worker made separate reports. A psychiatrist (Bowlby) then conducted an initial interview with the child and accompanying parent (e. g. , diagnosing affectionless psychopathy). • • More than half of the juvenile thieves had been separated from their mothers for longer than six months during their first five years. In the control group only two had such a separation. He also found 14 of the young thieves (32%) showed 'affectionless psychopathy' (they were not able to care about or feel affection for others). None of the control group were affectionless psychopaths. Bowlby found that 86% of the ‘affectionless psychopaths’ in group 1 (‘thieves) had experienced a long period of maternal separation before the age of 5 years (they had spent most of their early years in residential homes or hospitals and were not often visited by their families). Only 17% of the thieves not diagnosed as affectionless psychopaths had experienced maternal separation. Only 2 of the control group had experienced a prolonged separation in their first 5 years. Conclusion… Bowlby concluded that maternal separation/deprivation in the child’s early life caused permanent emotional damage. He diagnosed this as a condition and called it Affectionless Psychopathy. According to Bowlby, this condition involves a lack of emotional development, characterized by a lack of concern for others, lack of guilt and inability to form meaningful and lasting relationships.

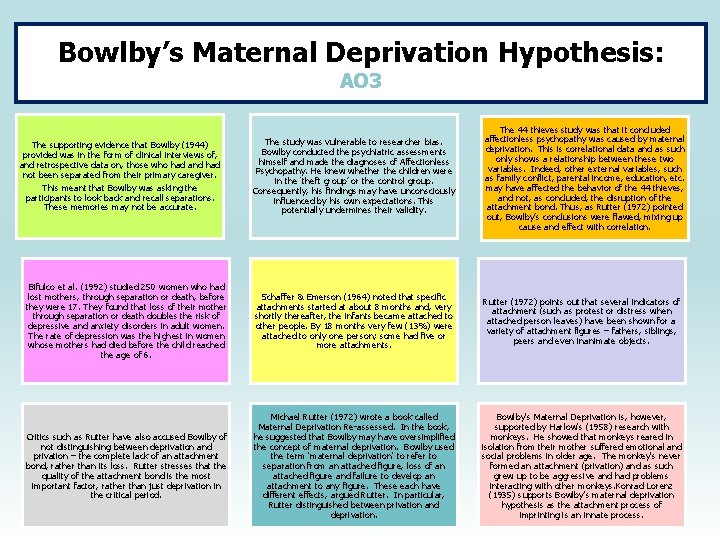

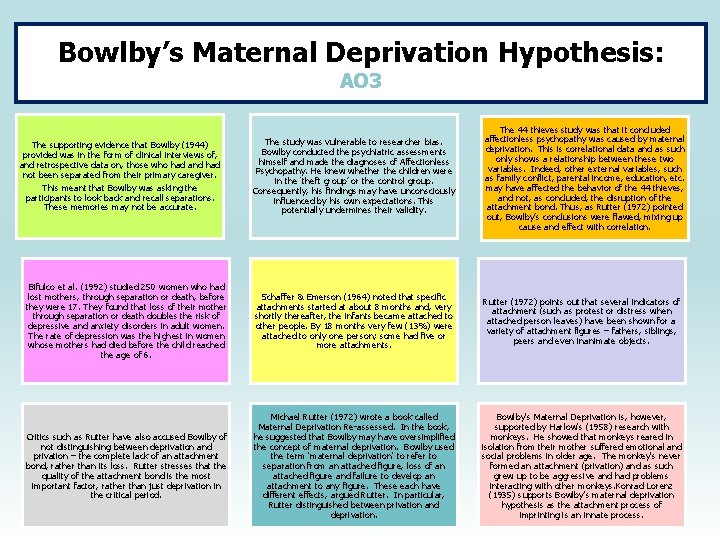

Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis: AO 3 The study was vulnerable to researcher bias. Bowlby conducted the psychiatric assessments himself and made the diagnoses of Affectionless Psychopathy. He knew whether the children were in the ‘theft group’ or the control group. Consequently, his findings may have unconsciously influenced by his own expectations. This potentially undermines their validity. The 44 thieves study was that it concluded affectionless psychopathy was caused by maternal deprivation. This is correlational data and as such only shows a relationship between these two variables. Indeed, other external variables, such as family conflict, parental income, education, etc. may have affected the behavior of the 44 thieves, and not, as concluded, the disruption of the attachment bond. Thus, as Rutter (1972) pointed out, Bowlby’s conclusions were flawed, mixing up cause and effect with correlation. Bifulco et al. (1992) studied 250 women who had lost mothers, through separation or death, before they were 17. They found that loss of their mother through separation or death doubles the risk of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult women. The rate of depression was the highest in women whose mothers had died before the child reached the age of 6. Schaffer & Emerson (1964) noted that specific attachments started at about 8 months and, very shortly thereafter, the infants became attached to other people. By 18 months very few (13%) were attached to only one person; some had five or more attachments. Rutter (1972) points out that several indicators of attachment (such as protest or distress when attached person leaves) have been shown for a variety of attachment figures – fathers, siblings, peers and even inanimate objects. Critics such as Rutter have also accused Bowlby of not distinguishing between deprivation and privation – the complete lack of an attachment bond, rather than its loss. Rutter stresses that the quality of the attachment bond is the most important factor, rather than just deprivation in the critical period. Michael Rutter (1972) wrote a book called Maternal Deprivation Re-assessed. In the book, he suggested that Bowlby may have oversimplified the concept of maternal deprivation. Bowlby used the term 'maternal deprivation' to refer to separation from an attached figure, loss of an attached figure and failure to develop an attachment to any figure. These each have different effects, argued Rutter. In particular, Rutter distinguished between privation and deprivation. Bowlby's Maternal Deprivation is, however, supported by Harlow's (1958) research with monkeys. He showed that monkeys reared in isolation from their mother suffered emotional and social problems in older age. The monkey's never formed an attachment (privation) and as such grew up to be aggressive and had problems interacting with other monkeys. Konrad Lorenz (1935) supports Bowlby's maternal deprivation hypothesis as the attachment process of imprinting is an innate process. The supporting evidence that Bowlby (1944) provided was in the form of clinical interviews of, and retrospective data on, those who had and had not been separated from their primary caregiver. This meant that Bowlby was asking the participants to look back and recall separations. These memories may not be accurate.

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • Romanian Orphan Studies • Institutionalisation

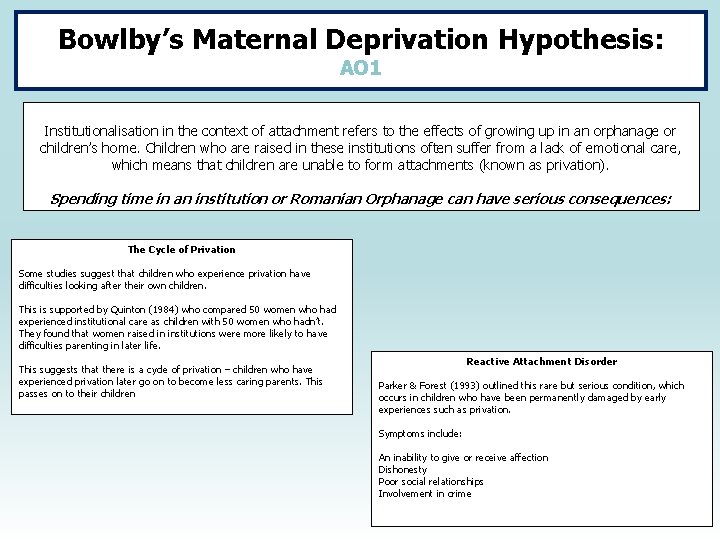

Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis: AO 1 Institutionalisation in the context of attachment refers to the effects of growing up in an orphanage or children’s home. Children who are raised in these institutions often suffer from a lack of emotional care, which means that children are unable to form attachments (known as privation). Spending time in an institution or Romanian Orphanage can have serious consequences: The Cycle of Privation Some studies suggest that children who experience privation have difficulties looking after their own children. This is supported by Quinton (1984) who compared 50 women who had experienced institutional care as children with 50 women who hadn’t. They found that women raised in institutions were more likely to have difficulties parenting in later life. This suggests that there is a cycle of privation – children who have experienced privation later go on to become less caring parents. This passes on to their children Reactive Attachment Disorder Parker & Forest (1993) outlined this rare but serious condition, which occurs in children who have been permanently damaged by early experiences such as privation. Symptoms include: An inability to give or receive affection Dishonesty Poor social relationships Involvement in crime

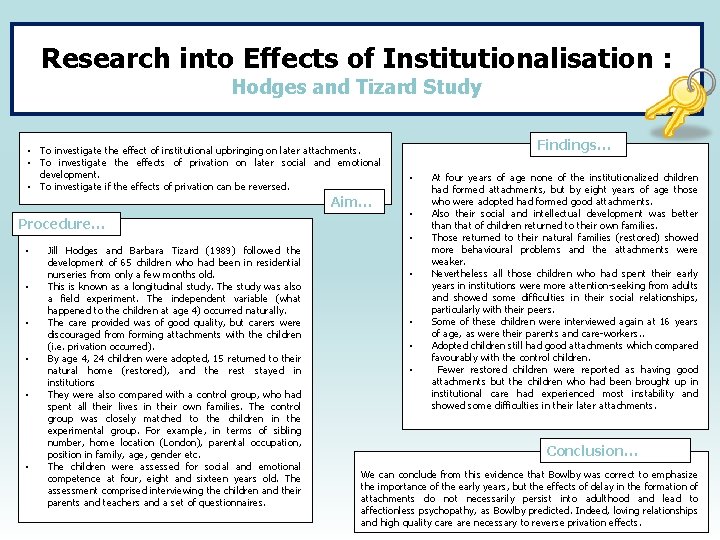

Research into Effects of Institutionalisation : Hodges and Tizard Study • To investigate the effect of institutional upbringing on later attachments. • To investigate the effects of privation on later social and emotional development. • To investigate if the effects of privation can be reversed. Aim… Procedure… • • • Jill Hodges and Barbara Tizard (1989) followed the development of 65 children who had been in residential nurseries from only a few months old. This is known as a longitudinal study. The study was also a field experiment. The independent variable (what happened to the children at age 4) occurred naturally. The care provided was of good quality, but carers were discouraged from forming attachments with the children (i. e. privation occurred). By age 4, 24 children were adopted, 15 returned to their natural home (restored), and the rest stayed in institutions They were also compared with a control group, who had spent all their lives in their own families. The control group was closely matched to the children in the experimental group. For example, in terms of sibling number, home location (London), parental occupation, position in family, age, gender etc. The children were assessed for social and emotional competence at four, eight and sixteen years old. The assessment comprised interviewing the children and their parents and teachers and a set of questionnaires. Findings… • • At four years of age none of the institutionalized children had formed attachments, but by eight years of age those who were adopted had formed good attachments. Also their social and intellectual development was better than that of children returned to their own families. Those returned to their natural families (restored) showed more behavioural problems and the attachments were weaker. Nevertheless all those children who had spent their early years in institutions were more attention-seeking from adults and showed some difficulties in their social relationships, particularly with their peers. Some of these children were interviewed again at 16 years of age, as were their parents and care-workers. . Adopted children still had good attachments which compared favourably with the control children. Fewer restored children were reported as having good attachments but the children who had been brought up in institutional care had experienced most instability and showed some difficulties in their later attachments. Conclusion… We can conclude from this evidence that Bowlby was correct to emphasize the importance of the early years, but the effects of delay in the formation of attachments do not necessarily persist into adulthood and lead to affectionless psychopathy, as Bowlby predicted. Indeed, loving relationships and high quality care necessary to reverse privation effects.

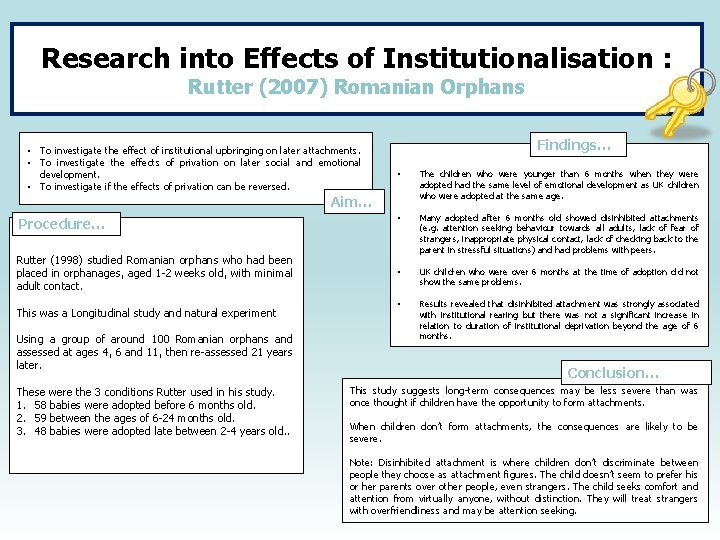

Research into Effects of Institutionalisation : Rutter (2007) Romanian Orphans • To investigate the effect of institutional upbringing on later attachments. • To investigate the effects of privation on later social and emotional development. • To investigate if the effects of privation can be reversed. Findings… • The children who were younger than 6 months when they were adopted had the same level of emotional development as UK children who were adopted at the same age. • Many adopted after 6 months old showed disinhibited attachments (e. g. attention seeking behaviour towards all adults, lack of fear of strangers, inappropriate physical contact, lack of checking back to the parent in stressful situations) and had problems with peers. • UK children who were over 6 months at the time of adoption did not show the same problems. • Results revealed that disinhibited attachment was strongly associated with institutional rearing but there was not a significant increase in relation to duration of institutional deprivation beyond the age of 6 months. Aim… Procedure… Rutter (1998) studied Romanian orphans who had been placed in orphanages, aged 1 -2 weeks old, with minimal adult contact. This was a Longitudinal study and natural experiment Using a group of around 100 Romanian orphans and assessed at ages 4, 6 and 11, then re-assessed 21 years later. These were the 3 conditions Rutter used in his study. 1. 58 babies were adopted before 6 months old. 2. 59 between the ages of 6 -24 months old. 3. 48 babies were adopted late between 2 -4 years old. . Conclusion… This study suggests long-term consequences may be less severe than was once thought if children have the opportunity to form attachments. When children don’t form attachments, the consequences are likely to be severe. Note: Disinhibited attachment is where children don’t discriminate between people they choose as attachment figures. The child doesn’t seem to prefer his or her parents over other people, even strangers. The child seeks comfort and attention from virtually anyone, without distinction. They will treat strangers with overfriendliness and may be attention seeking.

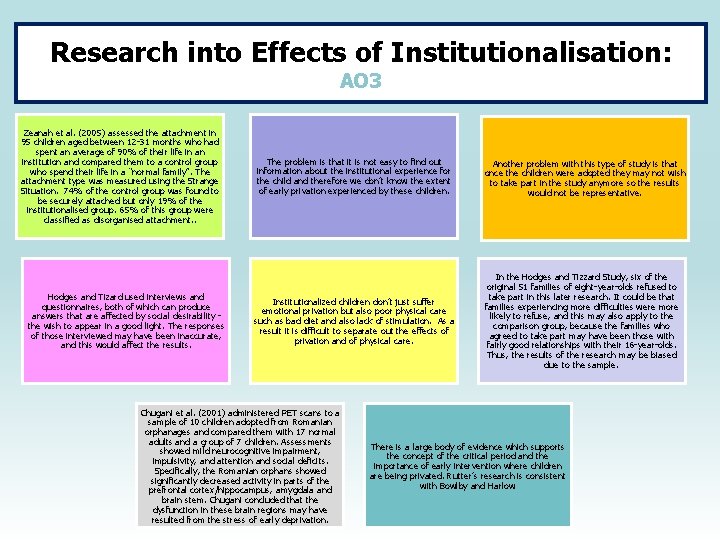

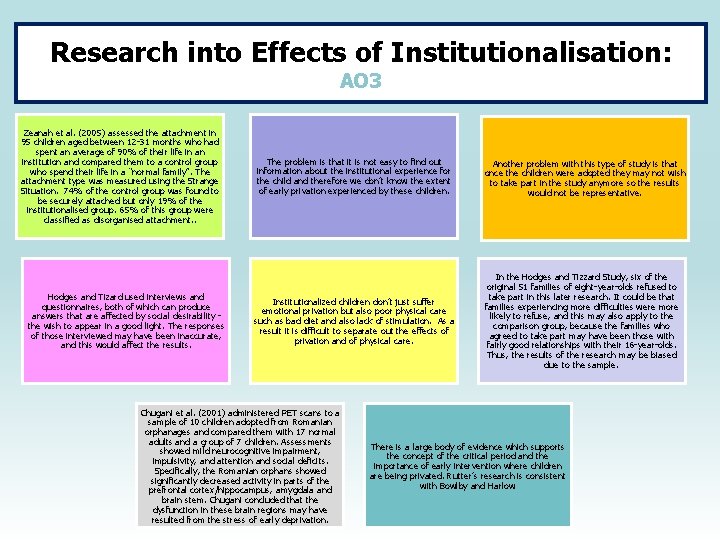

Research into Effects of Institutionalisation: AO 3 Zeanah et al. (2005) assessed the attachment in 95 children aged between 12 -31 months who had spent an average of 90% of their life in an institution and compared them to a control group who spend their life in a “normal family”. The attachment type was measured using the Strange Situation. 74% of the control group was found to be securely attached but only 19% of the institutionalised group. 65% of this group were classified as disorganised attachment. . Hodges and Tizard used interviews and questionnaires, both of which can produce answers that are affected by social desirability the wish to appear in a good light. The responses of those interviewed may have been inaccurate, and this would affect the results. The problem is that it is not easy to find out information about the institutional experience for the child and therefore we don’t know the extent of early privation experienced by these children. Institutionalized children don’t just suffer emotional privation but also poor physical care such as bad diet and also lack of stimulation. As a result it is difficult to separate out the effects of privation and of physical care. Chugani et al. (2001) administered PET scans to a sample of 10 children adopted from Romanian orphanages and compared them with 17 normal adults and a group of 7 children. Assessments showed mild neurocognitive impairment, impulsivity, and attention and social deficits. Specifically, the Romanian orphans showed significantly decreased activity in parts of the prefrontal cortex/hippocampus, amygdala and brain stem. Chugani concluded that the dysfunction in these brain regions may have resulted from the stress of early deprivation. Another problem with this type of study is that once the children were adopted they may not wish to take part in the study anymore so the results would not be representative. In the Hodges and Tizzard Study, six of the original 51 families of eight-year-olds refused to take part in this later research. It could be that families experiencing more difficulties were more likely to refuse, and this may also apply to the comparison group, because the families who agreed to take part may have been those with fairly good relationships with their 16 -year-olds. Thus, the results of the research may be biased due to the sample. There is a large body of evidence which supports the concept of the critical period and the importance of early intervention where children are being privated. Rutter’s research is consistent with Bowlby and Harlow

Specification Content; What the AQA say you should know… • The influence of early attachment on childhood and adult relationships. • Including the role of the internal working model.

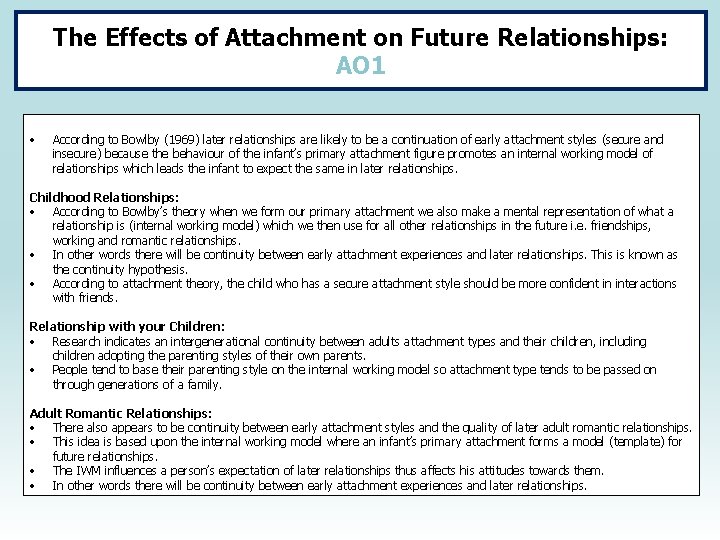

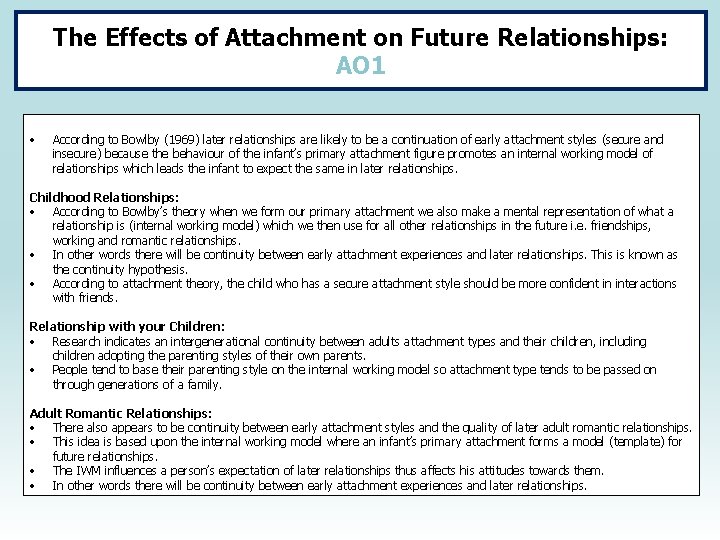

The Effects of Attachment on Future Relationships: AO 1 • According to Bowlby (1969) later relationships are likely to be a continuation of early attachment styles (secure and insecure) because the behaviour of the infant’s primary attachment figure promotes an internal working model of relationships which leads the infant to expect the same in later relationships. Childhood Relationships: • According to Bowlby’s theory when we form our primary attachment we also make a mental representation of what a relationship is (internal working model) which we then use for all other relationships in the future i. e. friendships, working and romantic relationships. • In other words there will be continuity between early attachment experiences and later relationships. This is known as the continuity hypothesis. • According to attachment theory, the child who has a secure attachment style should be more confident in interactions with friends. Relationship with your Children: • Research indicates an intergenerational continuity between adults attachment types and their children, including children adopting the parenting styles of their own parents. • People tend to base their parenting style on the internal working model so attachment type tends to be passed on through generations of a family. Adult Romantic Relationships: • There also appears to be continuity between early attachment styles and the quality of later adult romantic relationships. • This idea is based upon the internal working model where an infant’s primary attachment forms a model (template) for future relationships. • The IWM influences a person’s expectation of later relationships thus affects his attitudes towards them. • In other words there will be continuity between early attachment experiences and later relationships.

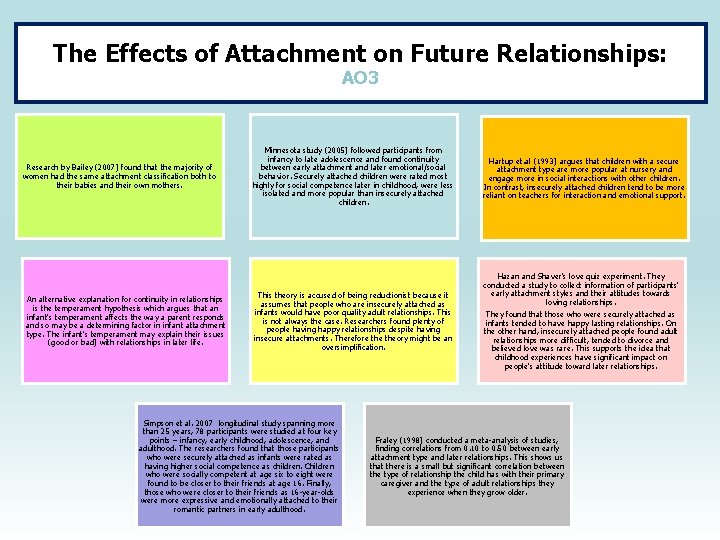

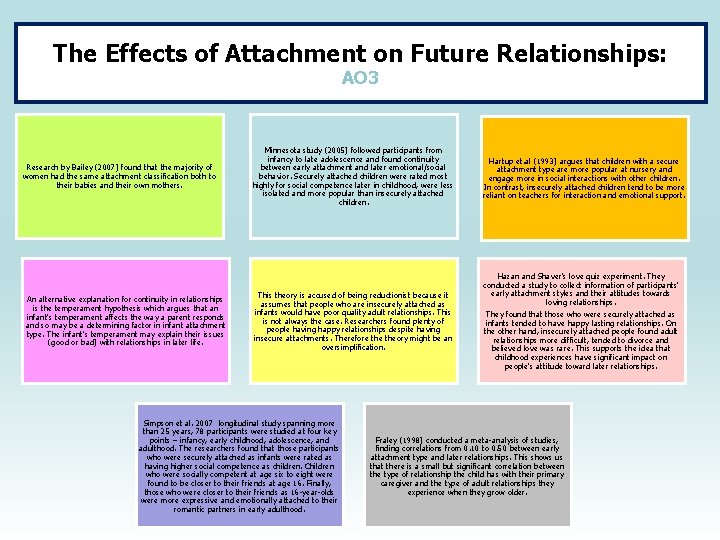

The Effects of Attachment on Future Relationships: AO 3 Research by Bailey (2007) found that the majority of women had the same attachment classification both to their babies and their own mothers. An alternative explanation for continuity in relationships is the temperament hypothesis which argues that an infant’s temperament affects the way a parent responds and so may be a determining factor in infant attachment type. The infant’s temperament may explain their issues (good or bad) with relationships in later life. Minnesota study (2005) followed participants from infancy to late adolescence and found continuity between early attachment and later emotional/social behavior. Securely attached children were rated most highly for social competence later in childhood, were less isolated and more popular than insecurely attached children. Hartup et. al (1993) argues that children with a secure attachment type are more popular at nursery and engage more in social interactions with other children. In contrast, insecurely attached children tend to be more reliant on teachers for interaction and emotional support. This theory is accused of being reductionist because it assumes that people who are insecurely attached as infants would have poor quality adult relationships. This is not always the case. Researchers found plenty of people having happy relationships despite having insecure attachments. Therefore theory might be an oversimplification. Hazan and Shaver’s love quiz experiment. They conducted a study to collect information of participants’ early attachment styles and their attitudes towards loving relationships. They found that those who were securely attached as infants tended to have happy lasting relationships. On the other hand, insecurely attached people found adult relationships more difficult, tended to divorce and believed love was rare. This supports the idea that childhood experiences have significant impact on people’s attitude toward later relationships. Simpson et al. 2007 longitudinal study spanning more than 25 years, 78 participants were studied at four key points – infancy, early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The researchers found that those participants who were securely attached as infants were rated as having higher social competence as children. Children who were socially competent at age six to eight were found to be closer to their friends at age 16. Finally, those who were closer to their friends as 16 -year-olds were more expressive and emotionally attached to their romantic partners in early adulthood. Fraley (1998) conducted a meta-analysis of studies, finding correlations from 0. 10 to 0. 50 between early attachment type and later relationships. This shows us that there is a small but significant correlation between the type of relationship the child has with their primary caregiver and the type of adult relationships they experience when they grow older.