Approaches used in the study of resilience Gopal

- Slides: 12

Approaches used in the study of resilience Gopal Netuveli International Centre for Life Course Studies in Society and Health Department of Primary Care and Social Medicine Imperial College London

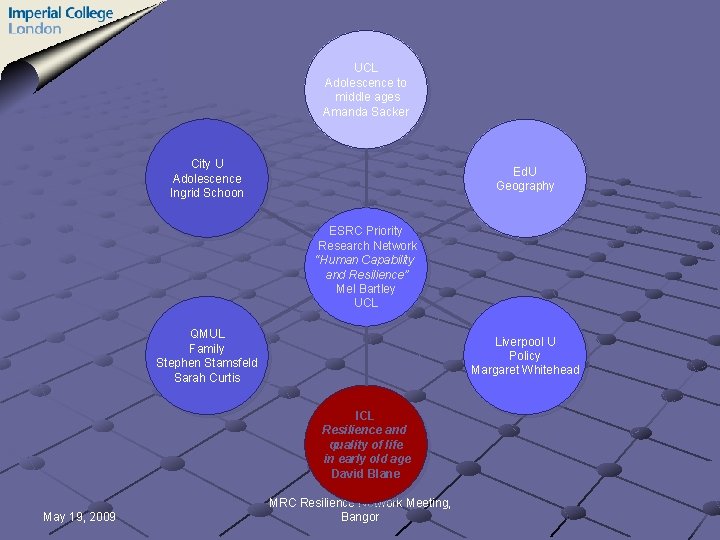

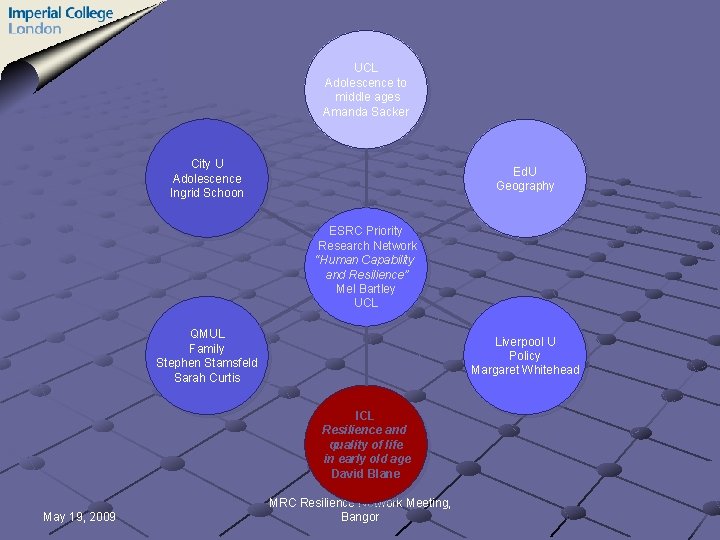

UCL Adolescence to middle ages Amanda Sacker City U Adolescence Ingrid Schoon Ed. U Geography ESRC Priority Research Network “Human Capability and Resilience” Mel Bartley UCL QMUL Family Stephen Stamsfeld Sarah Curtis Liverpool U Policy Margaret Whitehead ICL Resilience and quality of life in early old age David Blane May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

Resilience From Latin resilerre, “to jump back” or “to rebound” First discussed in detail by Holling (1973) n n the ability to return to the original state after perturbation and the ability to persist in the face of perturbation. Similarly defined in the study of children: n n n rebounding from adversity (Gramerzy 1993); preserving competence in the face of adversity (Werner 1994); good outcomes despite adversity and risk (Masten 2001). May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

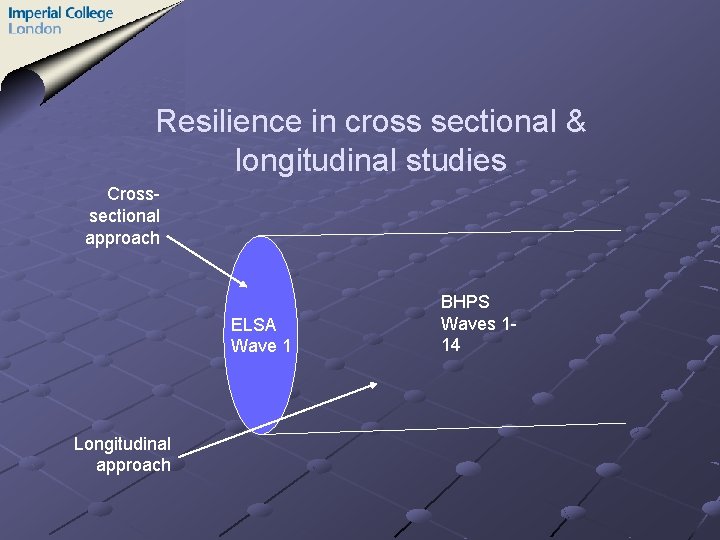

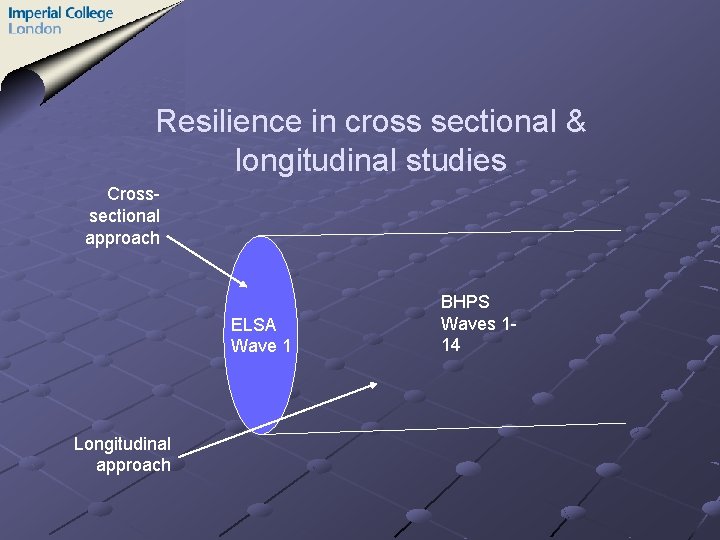

Resilience in cross sectional & longitudinal studies Crosssectional approach ELSA Wave 1 Longitudinal approach BHPS Waves 114

Definitions used Cross sectional analysis: “Flourishing despite adversity” Longitudinal analysis “Bouncing back after adversity” May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

Identifying resilience crosssectionally May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

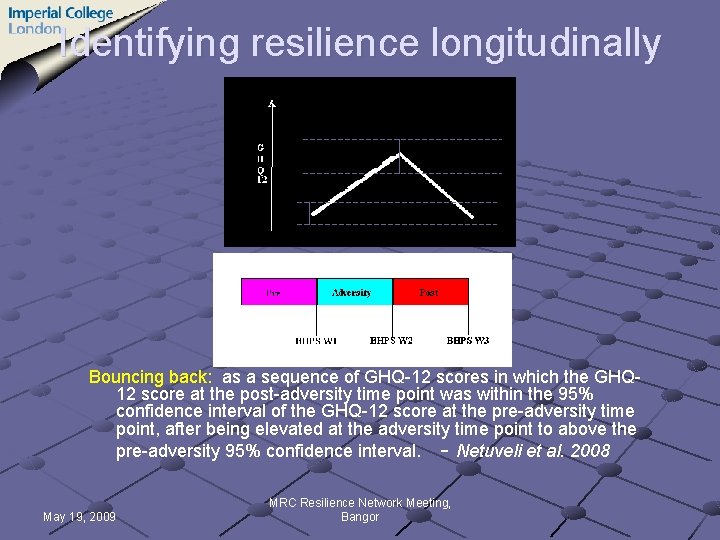

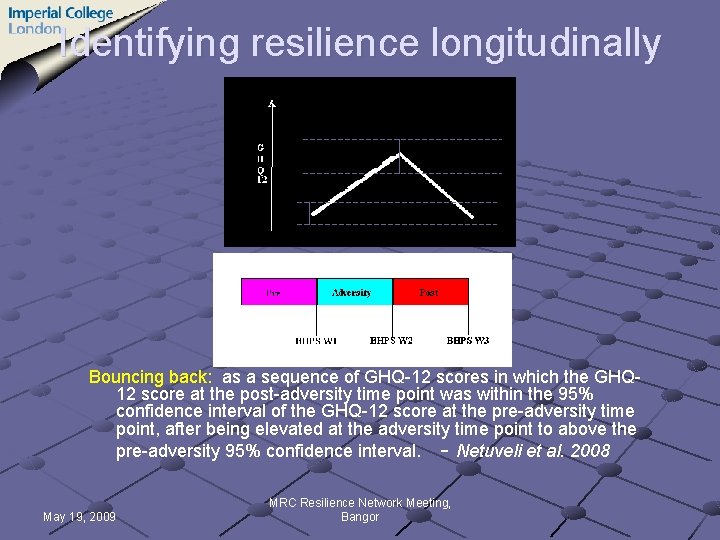

Identifying resilience longitudinally Bouncing back: as a sequence of GHQ-12 scores in which the GHQ 12 score at the post-adversity time point was within the 95% confidence interval of the GHQ-12 score at the pre-adversity time point, after being elevated at the adversity time point to above the pre-adversity 95% confidence interval. - Netuveli et al. 2008 May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

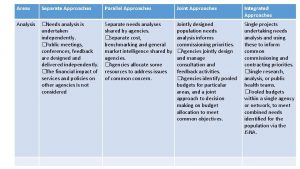

Differences between approaches Treatment of Adversity: CS: Same as risk LS: Using CS approach there are four possibilities: 1)Negative change in outcome after exposure persisting for a long period after exposure: ‘True adversity’; No resilience; 2) No change: Not an adversity? lack of vulnerability, or hardiness? 3) Positive change: Not an adversity? flourishing? 4) Negative change in outcome after exposure and recovery later: True adversity; Resilience as bouncing back or flourishing. Using LA only 1 and 4 are relevant May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

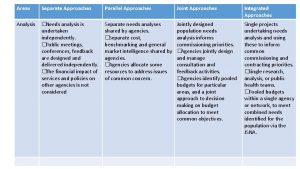

Differences between approaches Treatment of multiple adversities: CSA: Each adversity is treated as identical and independent. Additive model. LA: Dependency between adversities can be studied. Multiplicative model. May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

Differences in the methods used ELSA: Classification scheme Interaction to test resilience factors BHPS: Analytical strategy: Three time points: pre-event (t 0), event (t 1), postevent (t 2) May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

Discussion points from our studies Resilience is scarce in older ages. Prevalence of 15%. Not the ‘ordinary magic’ described in children. Different from successful ageing: resilience increased with age. ‘Gender paradox’: probability of exposure to adversity and resilience are both higher for women. Adversity and resilience are influenced differently by the same factors (e. g. tenure in BHPS) Social support before and during the adversity time point was the only significant predictor. Resilience was not adaptation May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

Our conclusions Resilience is a social process that converts social goods into good outcomes. It is to be found in the warp and woof of family and society. Policy implication: n Resilience can be nurtured through social policies that foster social support at the population level. However to be useful policy makers should adopt a preventative approach implementing policies before adversity has been experienced. May 19, 2009 MRC Resilience Network Meeting, Bangor

Gopal kakivaya

Gopal kakivaya Gopal kutwaroo

Gopal kutwaroo Vinodh gopal

Vinodh gopal Shuba gopal

Shuba gopal Gopal vijayaraghavan

Gopal vijayaraghavan Approaches to study public administration

Approaches to study public administration Political comparative and superlative

Political comparative and superlative What is linguistic

What is linguistic Types of resilience

Types of resilience Nc resilience and learning project

Nc resilience and learning project Boing boing resilience

Boing boing resilience Sears rating scale

Sears rating scale National risk and resilience unit scotland

National risk and resilience unit scotland