Applied Ethics An Introduction Applied Ethics 2 There

![Moral reasoning 45 § Consider the following: § § § [P 1] All children Moral reasoning 45 § Consider the following: § § § [P 1] All children](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b2811f1d793b783d7317cd9c5b0a3ff2/image-45.jpg)

- Slides: 75

Applied Ethics: An Introduction

Applied Ethics 2 § There are 12 lectures and 4 tutorials in a semester: § One lecture every week § One tutorial every 2 weeks § Please note that tutorial attendance is compulsory.

Applied Ethics 3 § The course requirements as well as the topics covered can be found in the Course Outline. § A wealth of useful resources can be found on the course website: applied-ethics. weebly. com

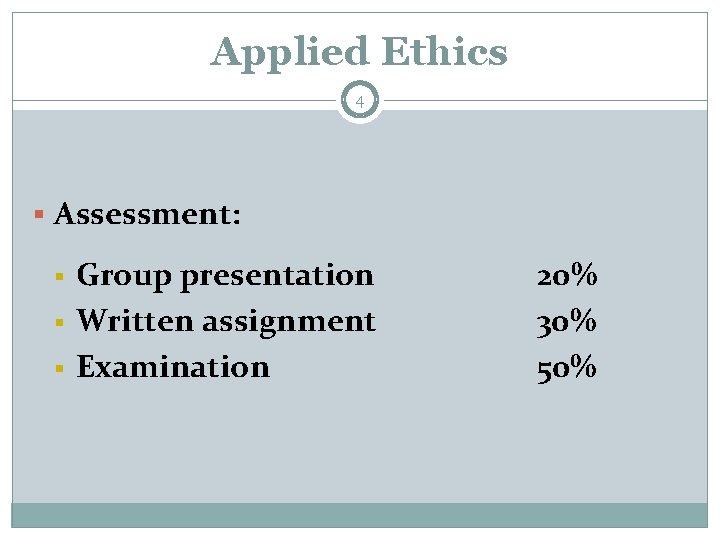

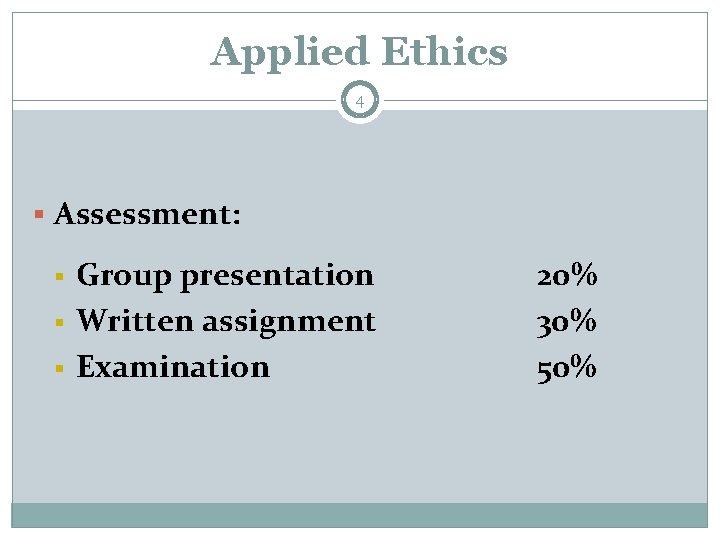

Applied Ethics 4 § Assessment: § § § Group presentation Written assignment Examination 20% 30% 50%

In this lecture… 5 § What is ethics? § Right and wrong § Moral reasoning § Fallacies § Principles and Theories

What is ethics? 6 § Ethics is the philosophical study of morality, a rational examination of people’s moral beliefs, judgments and behavior. § Applied ethics is a branch of moral philosophy that attempts to apply ethical principles, theories and concepts to reallife moral issues.

What is ethics? 7 § In the study of ethics, we evaluate people’s actions (i. e. to judge or decide whether these actions are right or wrong), we study people’s moral beliefs, and we examine the justifications (reasons) given for moral judgments and decisions.

What is ethics? 8 § In modern times, the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’ often have the same meaning. But what is morality and why do we need it? Morality can be understood as a system of widely accepted values and principles that helps people distinguish right from wrong, acceptable from unacceptable.

What is ethics? 9 § Every society has rules of conduct telling people what they should do and should not do in various situations. § We need morality (i. e. rules of behavior that people can agree on) because it tells us what we would expect others to do and what others would expect us to do.

Right and wrong 10 § Unlike the study of science, there is no unified method or approach in the study of ethics which can be used to examine moral judgments and decisions across different situations. § Moral beliefs, judgments and decisions, therefore, are much less ‘certain’ than scientific facts.

Right and wrong 11 § Susan believes that light travels faster than sound, while Dave believes that sound travels faster than light. § Anyone who has good scientific knowledge will agree that Susan’s belief is true whereas Dave’s belief is false. Why? Because Susan’s belief is based on scientific fact, but Dave’s is not.

Right and wrong 12 § The statement ‘Water boils at 100°c’ denotes an objective fact that can be examined scientifically to see whether it is true or false. § The same cannot be said of the statement ‘Homosexuality is immoral’, which is just someone’s subjective moral judgment.

Right and wrong 13 § Some people believe that science deals with ‘fact’ (objective facts), whereas ethics deals with ‘value’ (subjective value judgments). § According to this view, moral judgments are value judgments, and all value judgments are highly subjective.

Right and wrong 14 § If your friend has committed a crime (e. g. stealing from a supermarket), should you report the crime to the police?

Right and wrong 15 § Different people may have different opinions. They may not agree on what is the right thing to do. § Some may say that you should report the crime because ‘justice’ is more important than ‘friendship’. Others may choose not to report the crime because they value ‘friendship’ above ‘justice’.

Right and wrong 16 § Different people may have different responses because they have different moral values and beliefs. They may not agree on what is the right thing to do in a situation like this.

Right and wrong 17 § Does it imply that moral judgments (i. e. judgments about what is right and what is wrong) are simply subjective expressions of personal feelings and attitudes?

Right and wrong 18 § No, not necessarily. People’s moral beliefs and judgments can be either ‘subjective’ or ‘objective’. § Subjective moral judgments are based on personal feelings and attitudes, whereas objective moral judgments are based on reason and evidence (i. e. knowledge of actions, events, situations, etc. ).

Right and wrong 19 § In dealing with ethical issues, there are always objective and rational considerations that we should focus on when we make moral judgments and decisions. § In the previous example, we may ask ourselves the following questions:

Right and wrong 20 § How serious is the crime committed? How does it affect other people? § Are we really helping our friends if we cover up their crimes for them? § What would happen if everyone covered up the crimes committed by their friends?

Right and wrong 21 § Moral judgments, therefore, are not simply subjective expressions of personal feelings and attitudes. § Rational people are able to make moral judgments and decisions on the basis of objective knowledge of actions, events and situations, good moral reasoning, and shared moral values.

Moral reasoning 22 § Do you think babies can make moral judgments? Do they know the difference between right and wrong? § Let’s watch this video to find out!

Moral reasoning 23 § As we can see, babies as young as 3 months old prefer nice behavior to mean (bad) behavior. They also have an ‘innate sense of justice’. For example, they feel that bad behavior should be punished.

Moral reasoning 24 § However, babies’ moral judgments are not based on reason. As shown in the video, they favor those who are similar to them, and yet they want those who are different from them to be treated badly.

Moral reasoning 25 § Babies’ moral judgments are often irrational and unreasonable. They cannot explain, justify, or give reasons for their judgments. § In the study of ethics, we need to think about the reasons or justifications of our moral judgments, i. e. what makes an action right or wrong.

Moral reasoning 26 § Consider the following question: Is it acceptable for adult siblings (brothers and sisters) to have consensual sex with each other if they use contraception and no one is harmed?

Moral reasoning 27 § A survey found that about 80% of college students answered ‘No’ to the question, but most of them were unable to provide reasons or justifications for their opinion. § This shows that people’s moral judgments are often based on how they ‘feel’ about an issue rather than good moral reasoning.

Moral reasoning 28 § As we have seen, ethical choice is not simply a matter of personal preference. § Good moral judgment and decision- making should be based on evidence, i. e. objective knowledge of actions, events and situations. In addition, it also requires the use of ‘reason’.

Moral reasoning 29 § ‘Reason’ is the ability to think logically. Persons, objects, actions, events and situations are all represented in the human mind as ideas or concepts. § We use reason to make sense of the world by figuring out the relationship between ideas or concepts inside our minds. That is how we form our beliefs and judgments.

Moral reasoning 30 § We can use reason to decide what are the right or wrong things to do in various situations. Our moral judgments and decisions, in any circumstances, should be based on good moral reasoning.

Moral reasoning 31 § What should we do when people disagree on an ethical issue? § When people have different views about an issue, we can examine the evidence and the reasoning (supporting arguments) behind their beliefs and judgments to determine whose view is more reasonable.

Moral reasoning 32 § In the study of ethics, we can deal with disagreements through open-minded discussions of alternative viewpoints. § Because ethics is based on reason, we should be able to explain or justify our own moral judgments with reasoned arguments, and thereby persuade others to accept our point of view.

Moral reasoning 33 § To deal with ethical issues, it is necessary to think critically, i. e. to develop skills of reasoning and argumentation. § Not only should we familiarize ourselves with a variety of perspectives, we should also be able to explain why we agree or disagree with other people’s views and opinions.

Moral reasoning 34 § To think critically and reason well about an issue, we should: § understand the background or situation § think open-mindedly and raise relevant questions § gather and evaluate information

Moral reasoning 35 § examine various viewpoints and perspectives and their supporting arguments § come to a conclusion, i. e. a standpoint or position of our own § construct reasoned arguments to support our own position

Moral reasoning 36 § Philosophy in general and ethics in particular often have to deal with questions and issues that do not have model answers. § Although there are usually no model answers to controversial moral issues, some arguments are clearly better than others.

Moral reasoning 37 § There are good arguments as well as bad ones, and much of the skill of moral reasoning consists in discerning the difference. § Good arguments (reasoned arguments) are relevant, valid (logical), and well supported by evidence (facts, observations, statistics and examples).

Moral reasoning 38 § An argument is composed of a premise (or several premises) supporting a particular conclusion. § Premises are reasons or evidence offered to support a belief or judgment, and the conclusion is the belief, judgment or decision that the premises are intended to support.

Moral reasoning 39 § Reasoning is the act of drawing or deriving a conclusion from a premise or a set of premises. § Consider the following example: § § [P] Second-hand smoke can cause cancer. [C] Therefore, smoking in public areas should be banned.

Moral reasoning 40 § In this example, the premise ‘second- hand smoke can cause cancer’ is a fact that lends support to (i. e. provides the reason or justification for) the conclusion that ‘smoking in public areas should be banned’.

Moral reasoning 41 § Generally speaking, arguments are either ‘valid’ (logical) or ‘invalid’ (illogical). § A valid argument is one in which the support is as strong as can be: the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion.

Moral reasoning 42 § A sound or good argument is one that is valid (logical) and whose premises are true (and so its conclusion is true too). § An unsound or bad argument is one that is either invalid (illogical) or that has at least one false premise.

Moral reasoning 43 § A distinction can be made between ‘deductive arguments’ and ‘inductive arguments’.

Moral reasoning 44 § A ‘deductive argument’ is valid or logical if the conclusion follows logically or necessarily from the premises: § § § [P 1] All lizards are reptiles. [P 2] All reptiles are animals. [C] Therefore, all lizards are animals.

![Moral reasoning 45 Consider the following P 1 All children Moral reasoning 45 § Consider the following: § § § [P 1] All children](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b2811f1d793b783d7317cd9c5b0a3ff2/image-45.jpg)

Moral reasoning 45 § Consider the following: § § § [P 1] All children are afraid of the dark. [P 2] Dorothy is afraid of the dark. [C] Therefore, Dorothy is a child. § Is this a valid deductive argument? Why or why not?

Moral reasoning 46 § An inductive argument is one whose premises make the conclusion seem probable yet still not necessarily true. § The strength of an inductive argument usually depends on the quantity as well as the quality (i. e. relevance and strength) of the evidence provided.

Moral reasoning 47 § Consider the following: § ‘My little brother has many of the symptoms of pneumonia, such as fever, cough, headaches and shortness of breath. So it is likely that he has the disease. ’

Moral reasoning 48 § The argument can be broken down into a series of premises that build to a conclusion: § § § [P 1] My brother has a fever. [P 2] My brother is coughing. [P 3] My brother has a headache. [P 4] My brother has shortness of breath. [C] My brother has pneumonia.

Moral reasoning 49 § In this example, it can be said that even if all the premises (P 1, P 2, P 3, and P 4) are true, we still cannot be completely certain about the truth of the conclusion (C). § The conclusion (C), in other words, is highly probable but not definite.

Moral reasoning 50 § When we evaluate our own or other people’s arguments, we should consider the following questions: § § Is the evidence relevant? Are the facts correct? Is the reasoning logical? Are there any counterarguments?

Moral reasoning 51 § To sum up, what we need to do in the study of ethics is to think critically about ethical issues. § It is necessary to [1] consider various perspectives; [2] analyze and evaluate arguments; and [3] construct reasoned arguments to support our own views.

Fallacies 52 § Reasoning, as we have seen, is the act of deriving a conclusion from a premise or a set of premises. § A ‘fallacy’ is an error in reasoning. An argument is fallacious if the premise or premises do not support the conclusion.

Fallacies 53 § Because there are hundreds of ways an argument can go wrong, there are hundreds of different types of fallacies. § As examples, we will focus on four types of fallacies; namely, ‘false analogy’, ‘begging the question’, ‘the straw man’ and ‘the slippery slope’.

Fallacies 54 § Two things may have superficial similarities, but they are not exactly the same. § ‘False analogy’ is the mistake of overlooking the dissimilarities between things.

Fallacies 55 § For example, you may think that a person is lazy just because you have seen that the person’s brother is lazy. § This is likely to be a case of ‘false analogy’ because having the same biological parents may have little or nothing to do with the character trait of ‘laziness’.

Fallacies 56 § Another common fallacy or error in reasoning is called begging the question or arguing in a circle. Consider the following statement: § Abortion should be permitted because women should be allowed to make choices.

Fallacies 57 § Since ‘to permit’ has exactly the same meaning as ‘to allow to choose’, the above statement simply repeats itself without giving any real reason or explanation. § Further argument or information would have to be given to explain why women should be allowed to choose abortion.

Fallacies 58 § The straw man fallacy is an error in reasoning that we commit when we attribute a poorly reasoned argument to someone who never actually made that argument.

Fallacies 59 § Here is an example: § The Buddha thinks that desire is the root cause of suffering. The best way to extinguish one’s desire is to commit suicide. Therefore, the Buddha encourages people to commit suicide.

Fallacies 60 § When someone criticizes Buddhism for encouraging people to commit suicide, they are attacking a straw man because the Buddha never says anything to that effect. The Buddha does not think that committing suicide is the best or only way to extinguish desire.

Fallacies 61 § Slippery slope arguments are often put forward to criticize certain proposals or initiatives on the grounds that putting them into practice would lead to terrible outcomes in the long run.

Fallacies 62 § It usually involves a prediction that serious, avoidable harm will follow if some new policy is introduced or some legal, social or political reform is carried out. § Once the Pandora’s box is open, there is no way of preventing the dreadful consequences.

Fallacies 63 § A slippery slope argument typically states that a relatively small first step will cause a chain of related events and eventually result in a disaster of some sort. § It usually involves making a claim that A leads to B, B leads to C, and so on. And things only get worse and worse.

Fallacies 64 § Here is an example: § If we legalize soccer betting, more people will be addicted to gambling. As the number of pathological gamblers increases, there will be more crimes and other social problems. We must think twice before allowing this to happen.

Fallacies 65 § Whether a ‘slippery slope argument’ is sound or not depends to a large extent on the availability of evidence. § If there is insufficient evidence for the slippery slope effect, then it can be regarded as a ‘fallacy’.

Principles and theories 66 § Moral principles are general rules or standards for evaluating conduct. § Examples of moral principles include the Golden Rule (‘Treat others as one would wish to be treated oneself. ’) and the principle of equality (‘Like cases should be treated alike. ’)

Principles and theories 67 § Many ethical arguments consist of principles being applied to the facts of particular cases, for example: § § § [P 1] All humans should be treated equally. [P 2] African Americans are humans. [C] Therefore, it is wrong to discriminate against African Americans.

Principles and theories 68 § A theory can be seen as a framework of principles and related concepts that can be employed to make sense of people, things, actions, events, and situations. § Theories can be employed to analyze, explain and deal with various types of problems.

Principles and theories 69 § Not only do moral theories provide justifications for our actions, judgments and decisions, we can also make use of them to evaluate the actions, judgments and decisions of others.

Principles and theories 70 § In forthcoming lectures, we will focus specifically on two contemporary moral theories, namely, ‘utilitarianism’ and ‘Kantian ethics’.

Principles and theories 71 § Utilitarianism proposes that we should judge whether an action is better than its alternatives by considering its actual or expected effectiveness in promoting general happiness.

Principles and theories 72 § Kantian ethics, on the other hand, emphasizes our duty to act on moral principles that conform to requirements of rationality and human dignity.

Principles and theories 73 § Moral theories and principles should not be seen as ready-made solutions that can be applied mechanically to deal with moral problems. § In fact, when two or more ethical principles or theories come into conflict in a particular situation, we may find ourselves caught in a moral dilemma.

Principles and theories 74 § A ‘dilemma’ is a situation in which we have to make a difficult choice between two (or more) alternatives. § A moral dilemma occurs when we must decide between two (or more) conflicting actions. We have good reasons to perform each action, but the actions cannot both be performed.

Principles and theories 75 § Here is an example: § A child is crying in the street. No one is helping her. You need to go to your best friend’s wedding because you promised to be the cameraman for him. If you help the child, you will not be able to arrive on time, and your friend will be sad angry. What should you do?