Application of Fortran 90 to ocean model codes

- Slides: 20

Application of Fortran 90 to ocean model codes Mark Hadfield National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research New Zealand

It’s not about me but… • I have used ocean models: – ROMS – POL 3 D – MOMA • I program in – Fortran – IDL – Python, Matlab, C++, … • I run models and analysis software on – PC, Win 2000, Compaq Fortran or Cygwin g 77 – Cray T 3 E – Compaq Alpha machines with 1 or 2 CPUs Slide 2 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Outline of this talk • Fortran 90/95 new features • Some Fortran 90/95 features in more detail • Application in ROMS • Tales from the front line • ROMS 1 and ROMS 2 performance • Conclusions Slide 3 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Fortran 90/95 new features (1) • Dynamic data objects – Allocatable arrays – Pointers – Automatic data objects • Array processing – Whole-array operations – Array subset syntax – New intrinsic functions – Pointers • Free-format source Slide 4 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Fortran 90/95 new features (2) • Modules – Replace COMMON for packaging global data – Hide information – Bundle operations with data • INCLUDE statement! • Procedure enhancements – Explicit interfaces (MODULE procedures & INTERFACE statement) – Optional & named arguments – Generic procedures Slide 5 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Fortran 90/95 new features (3) • Data structures • User-defined types and operators • New control structures • Portable ways to specify numeric precision • I/O enhancements – Name lists Slide 6 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Fortran 90 Pros & Cons (1) • Pros – Data organisation can match the problem better – Enables more readable, maintainable code – Stricter argument checking – Libraries can present a cleaner interface – Supported by all (? ) commercial compilers Slide 7 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Fortran 90 Pros & Cons (2) • Cons – Greater feature load can reduce readability & maintainability – Potential reduction in performance – No satisfactory open-source compiler – Modules complicate building a program with multiple source files – Commercial compilers still have performance problems and bugs Slide 8 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

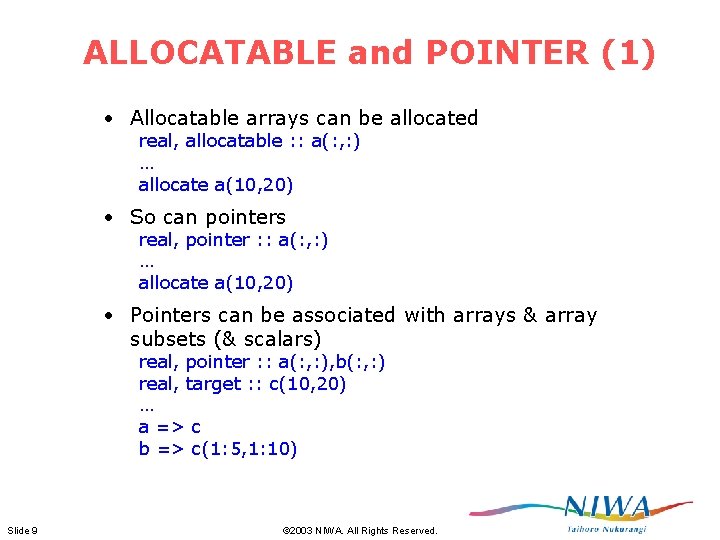

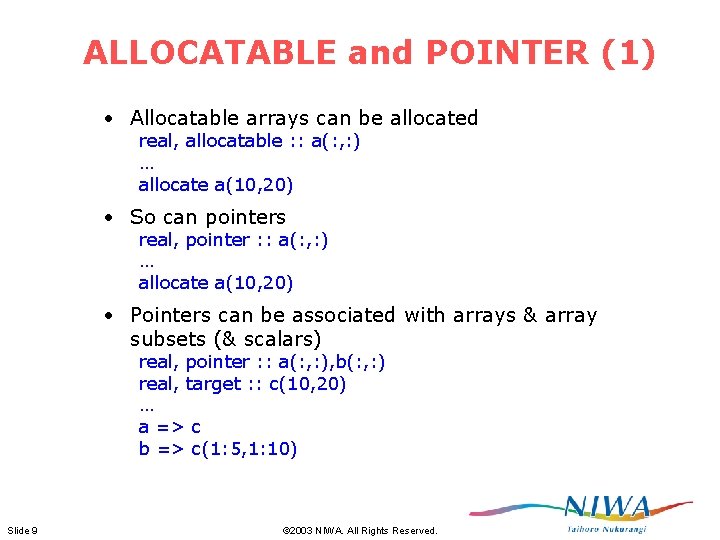

ALLOCATABLE and POINTER (1) • Allocatable arrays can be allocated real, allocatable : : a(: , : ) … allocate a(10, 20) • So can pointers real, pointer : : a(: , : ) … allocate a(10, 20) • Pointers can be associated with arrays & array subsets (& scalars) real, pointer : : a(: , : ), b(: , : ) real, target : : c(10, 20) … a => c b => c(1: 5, 1: 10) Slide 9 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

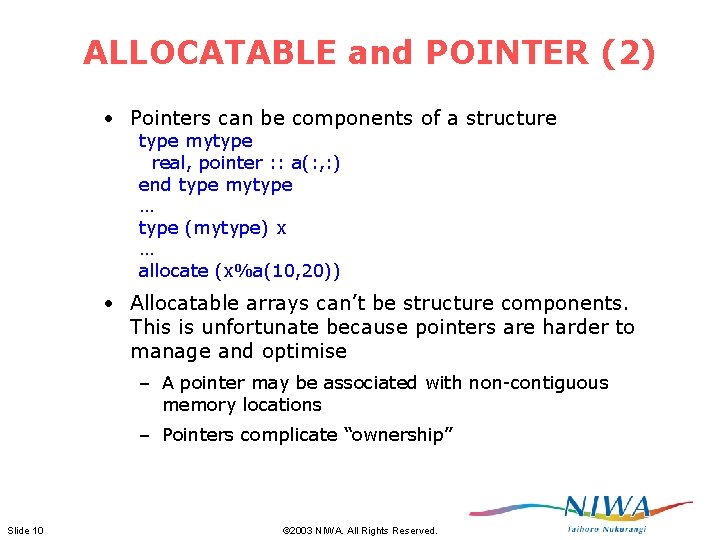

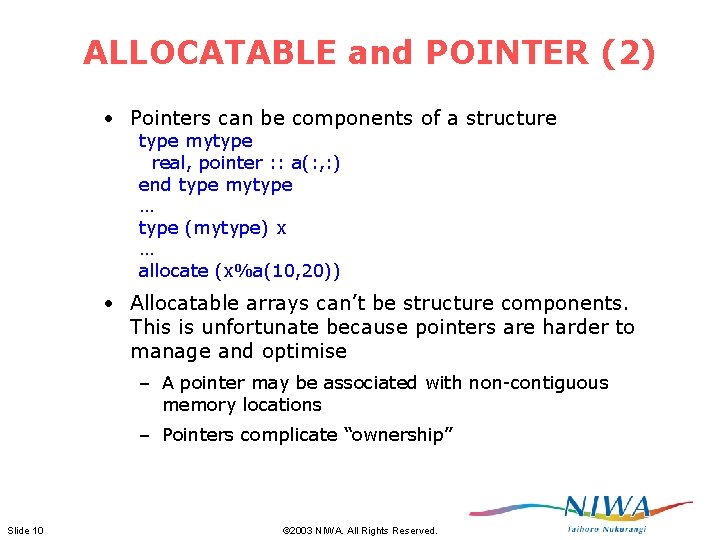

ALLOCATABLE and POINTER (2) • Pointers can be components of a structure type mytype real, pointer : : a(: , : ) end type mytype … type (mytype) x … allocate (x%a(10, 20)) • Allocatable arrays can’t be structure components. This is unfortunate because pointers are harder to manage and optimise – A pointer may be associated with non-contiguous memory locations – Pointers complicate “ownership” Slide 10 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

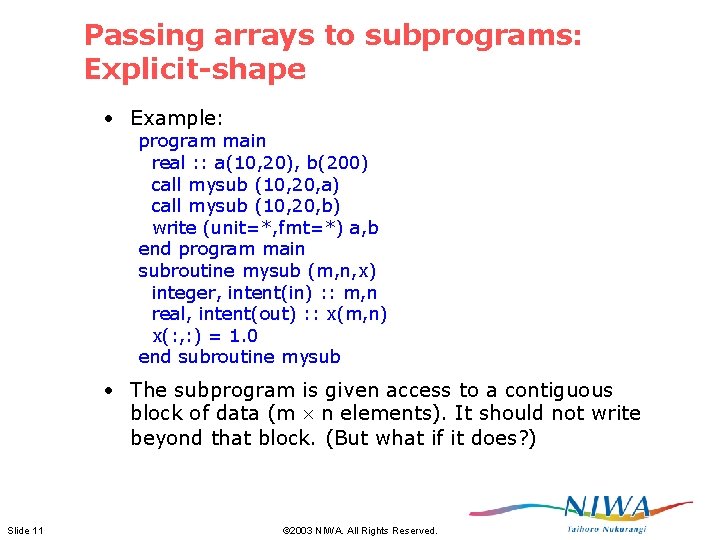

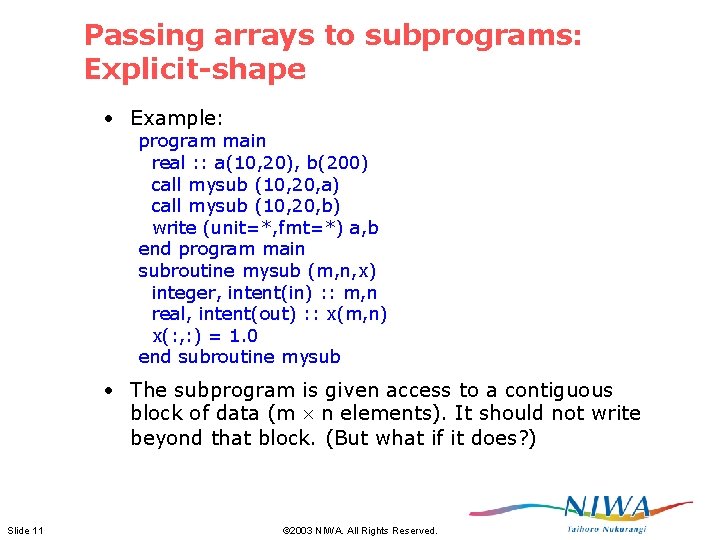

Passing arrays to subprograms: Explicit-shape • Example: program main real : : a(10, 20), b(200) call mysub (10, 20, a) call mysub (10, 20, b) write (unit=*, fmt=*) a, b end program main subroutine mysub (m, n, x) integer, intent(in) : : m, n real, intent(out) : : x(m, n) x(: , : ) = 1. 0 end subroutine mysub • The subprogram is given access to a contiguous block of data (m n elements). It should not write beyond that block. (But what if it does? ) Slide 11 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

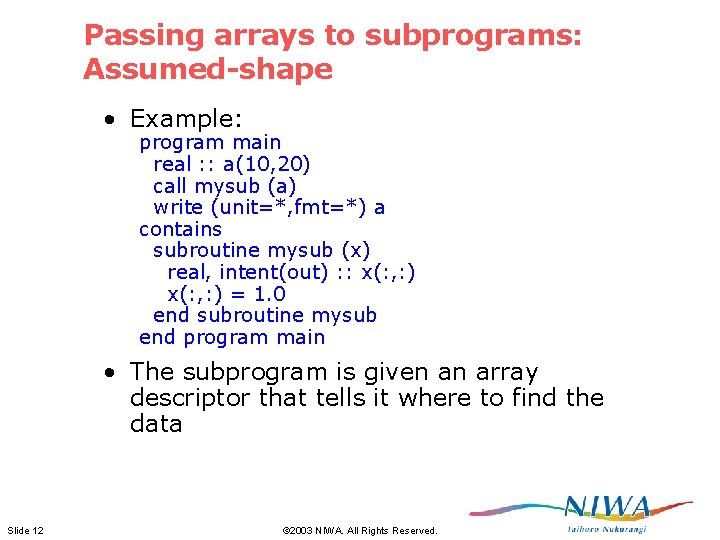

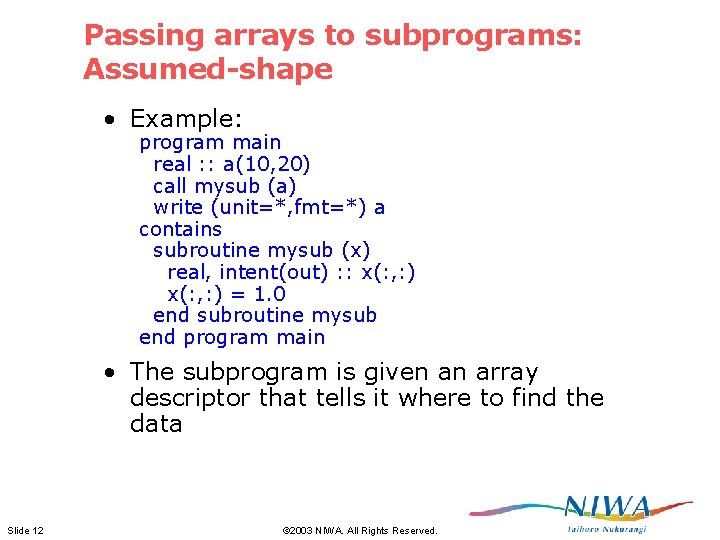

Passing arrays to subprograms: Assumed-shape • Example: program main real : : a(10, 20) call mysub (a) write (unit=*, fmt=*) a contains subroutine mysub (x) real, intent(out) : : x(: , : ) = 1. 0 end subroutine mysub end program main • The subprogram is given an array descriptor that tells it where to find the data Slide 12 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

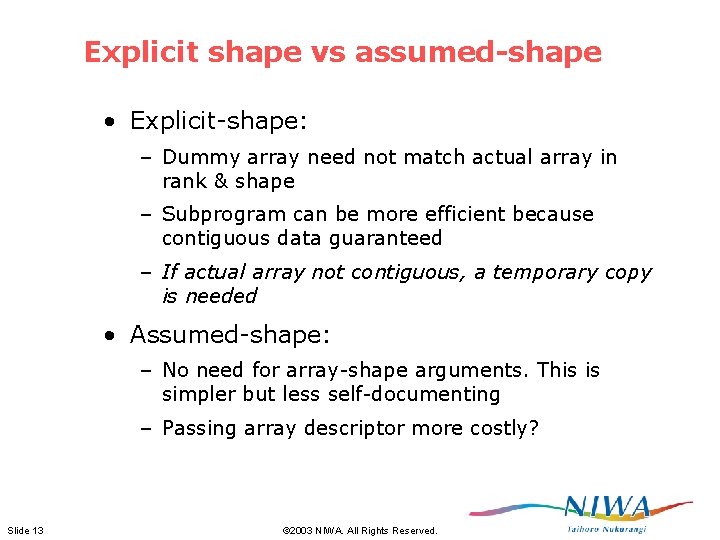

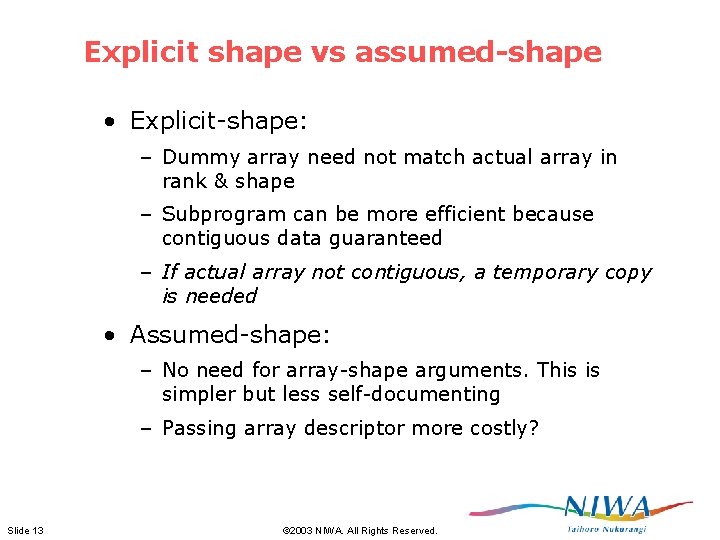

Explicit shape vs assumed-shape • Explicit-shape: – Dummy array need not match actual array in rank & shape – Subprogram can be more efficient because contiguous data guaranteed – If actual array not contiguous, a temporary copy is needed • Assumed-shape: – No need for array-shape arguments. This is simpler but less self-documenting – Passing array descriptor more costly? Slide 13 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

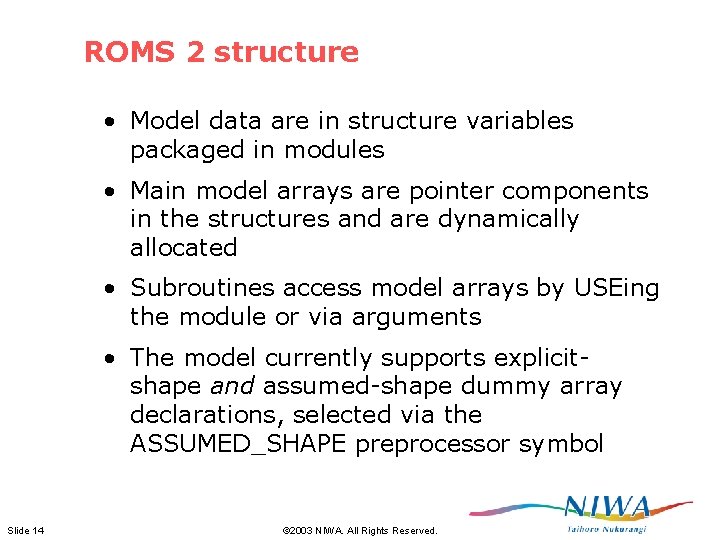

ROMS 2 structure • Model data are in structure variables packaged in modules • Main model arrays are pointer components in the structures and are dynamically allocated • Subroutines access model arrays by USEing the module or via arguments • The model currently supports explicitshape and assumed-shape dummy array declarations, selected via the ASSUMED_SHAPE preprocessor symbol Slide 14 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Why explicit- and assumed-shape? • Assumed-shape required because – With some older compilers, there is a drastic (5 ) performance drop with explicit-shape declarations • Recall that pointers can be associated with noncontiguous data, in which case a temporary, contiguous copy must be made. • Newer compilers apparently detect that pointers in ROMS are associated with contiguous data and avodi the copy. Older ones do not. – Some (Compaq) compilers have trouble with the form of the explicit-shape declarations in ROMS real(r 8) : : tke(LBi: UBi, LBj: UBj, 0: N(ng), 3) • Explicit-shape retained because – On some platforms, the model runs faster with this option (6% faster on Cray T 3 E) – Weaker checking allows some subroutines to accept 2 D or 3 D data, avoiding duplication of code Slide 15 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Another tale from the front line • MOM 4 is a substantially revised version of the GFDL MOM model, written in Fortran 90, supporting STATIC and DYNAMIC memory options • Early tests showed a substantial (40%) drop in performance with the DYNAMIC option. This was traced to a performance bug in the SGI test compiler, triggered by the combination of array syntax operations on dynamically allocated arrays within derived types (from message on MOM 4 mailing list by Christopher Kerr). Slide 16 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

ROMS 2 performance (1) • Tested on two platforms – PC, Pentium 4 2. 67 GHz, Windows 2000, Compaq Visual Fortran 6. 6 – NIWA’s Cray T 3 E (Kupe), 140 PE, Alpha EV 5 600 MHz • The CPU on the PC is 6– 8 times as fast as one PE on Kupe. We need to get 20 PEs on the job to make Kupe worthwhile; the maximum reasonable number is usually 60. Slide 17 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

ROMS 2 performance (2) • On the PC – For a small problem (UPWELLING) execution time in ROMS 2 is 40% less than in ROMS 1. – This advantage does not hold for medium-size problems (BENCHMARK 1). For these, ROMS 2 speed is similar to ROMS 1. – ROMS 2 supports multiple tiles in serial mode. For medium-size problems using a modest number of tiles (20– 60) reduces execution time by 25%. – Explicit-shape code doesn’t work due to compiler bugs, but if we work around these bugs explicitand assumed-shape speeds are similar. Slide 18 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

ROMS 2 performance (3) • On Kupe – Serial runs show same speedup of ROMS 2 relative to ROMS 1 for small problems, same lack of speedup for large problems – No advantage using multiple tiles in serial mode – Explicit-shape code 6% faster than assumedshape – MPI runs on n processors show an n speedup as long as tile size is 25 or more – PE performance, scaling & memory size make Kupe an effective tool for model runs up to (say) 400 30 Slide 19 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.

Conclusions • ROMS 2 (Fortran 90) is not significantly slower than ROMS 1 (Fortran 77) • For small problems ROMS 2 is significantly faster than ROMS 1 • There are performance pitfalls in Fortran 90, mostly related to inefficient treatment of pointers • Widespread use of array operations is probably not a good idea • Compiler bugs remain a problem • A community model needs to be tested on a variety of platforms to uncover problems Slide 20 © 2003 NIWA. All Rights Reserved.