Application of Common Cause Failure Methodology to Aviation

- Slides: 24

Application of Common Cause Failure Methodology to Aviation Safety Assessment Model June 22, 2016 Seungwon Noh Dr. John Shortle 7 th International Conference on Research in Air Transportation

Contents § Introduction § Literature Review § Methodologies • Common Cause Failure Model • Fault Tree Quantification Method § Results § Conclusions

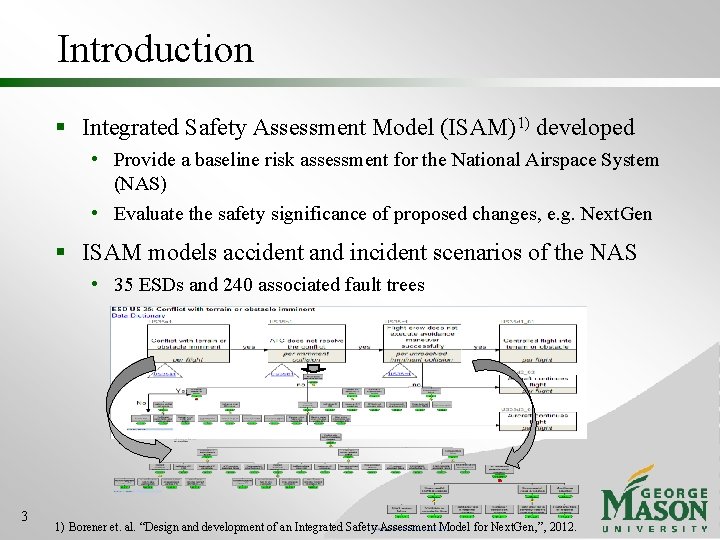

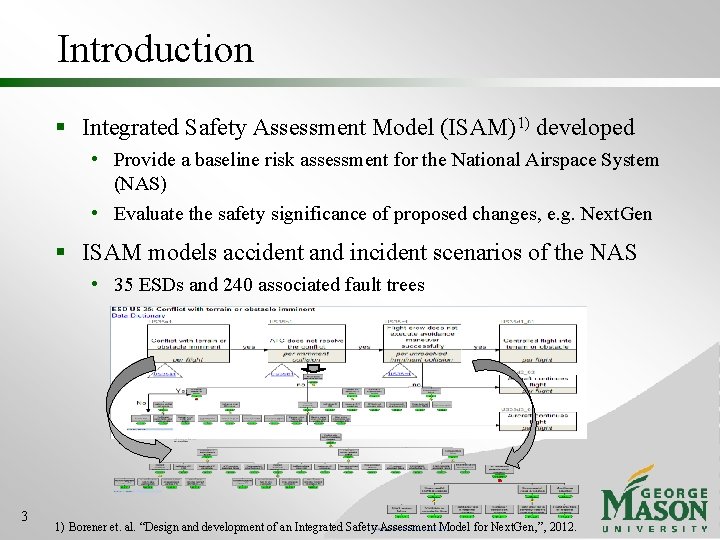

Introduction § Integrated Safety Assessment Model (ISAM)1) developed • Provide a baseline risk assessment for the National Airspace System (NAS) • Evaluate the safety significance of proposed changes, e. g. Next. Gen § ISAM models accident and incident scenarios of the NAS • 35 ESDs and 240 associated fault trees 3 1) Borener et. al. “Design and development of an Integrated Safety Assessment Model for Next. Gen, ”, 2012.

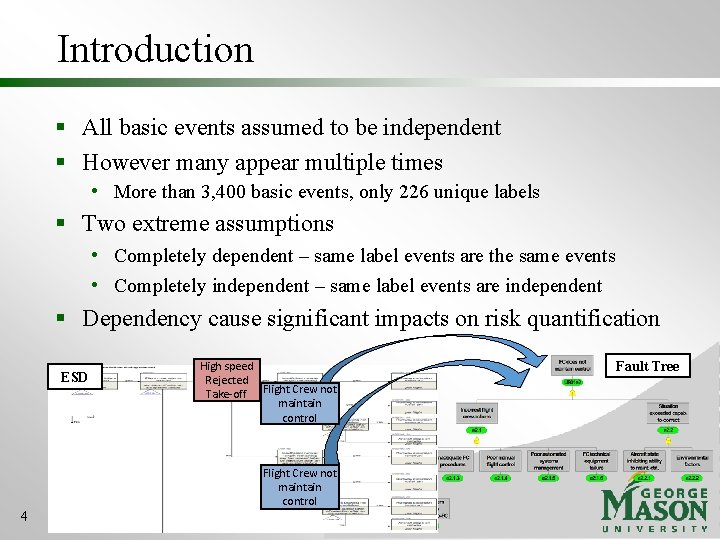

Introduction § All basic events assumed to be independent § However many appear multiple times • More than 3, 400 basic events, only 226 unique labels § Two extreme assumptions • Completely dependent – same label events are the same events • Completely independent – same label events are independent § Dependency cause significant impacts on risk quantification ESD High speed Rejected Take-off Flight Crew not maintain control 4 Fault Tree

Objective § Apply a Common Cause Failure (CCF) methodology to ISAM • to see impacts of dependency between basic events having a same label, and • to see sensitivity of CCFs by assuming different levels of dependency between basic events 5

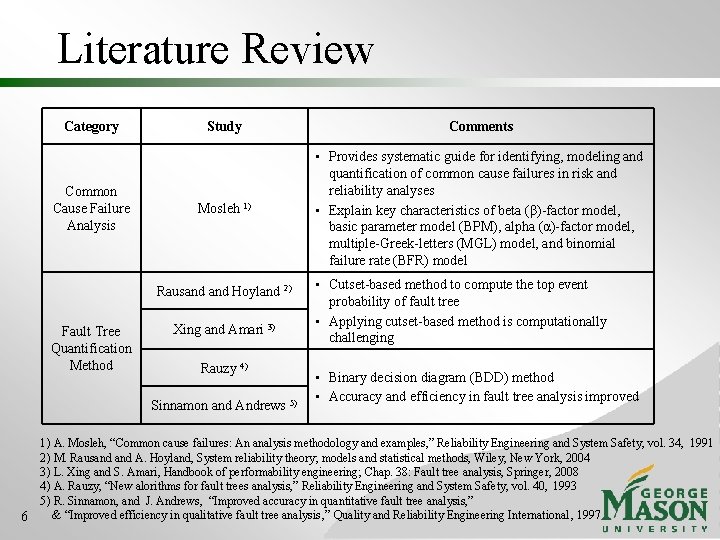

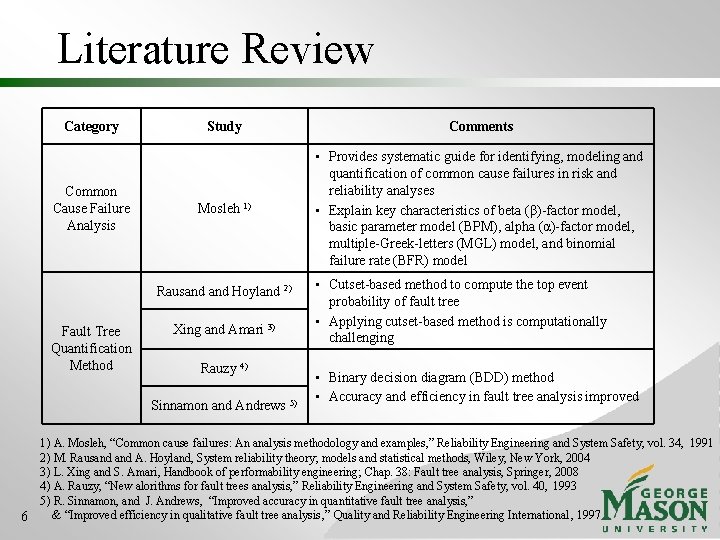

Literature Review Category Common Cause Failure Analysis Study Comments Mosleh 1) • Provides systematic guide for identifying, modeling and quantification of common cause failures in risk and reliability analyses • Explain key characteristics of beta (β)-factor model, basic parameter model (BPM), alpha (α)-factor model, multiple-Greek-letters (MGL) model, and binomial failure rate (BFR) model Rausand Hoyland 2) Fault Tree Quantification Method Xing and Amari 3) Rauzy 4) Sinnamon and Andrews 5) • Cutset-based method to compute the top event probability of fault tree • Applying cutset-based method is computationally challenging • Binary decision diagram (BDD) method • Accuracy and efficiency in fault tree analysis improved 1) A. Mosleh, “Common cause failures: An analysis methodology and examples, ” Reliability Engineering and System Safety, vol. 34, 1991 2) M. Rausand A. Hoyland, System reliability theory; models and statistical methods, Wiley, New York, 2004 3) L. Xing and S. Amari, Handbook of performability engineering; Chap. 38: Fault tree analysis, Springer, 2008 4) A. Rauzy, “New alorithms for fault trees analysis, ” Reliability Engineering and System Safety, vol. 40, 1993 5) R. Sinnamon, and J. Andrews, “Improved accuracy in quantitative fault tree analysis, ” & “Improved efficiency in qualitative fault tree analysis , ” Quality and Reliability Engineering International, 1997 6

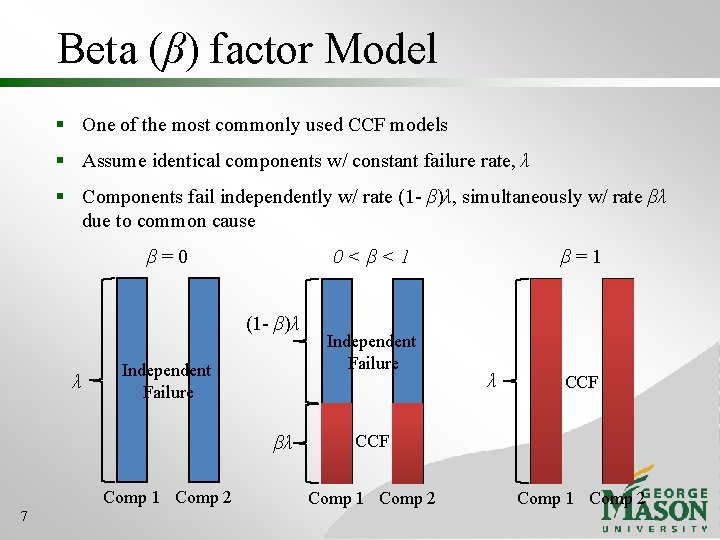

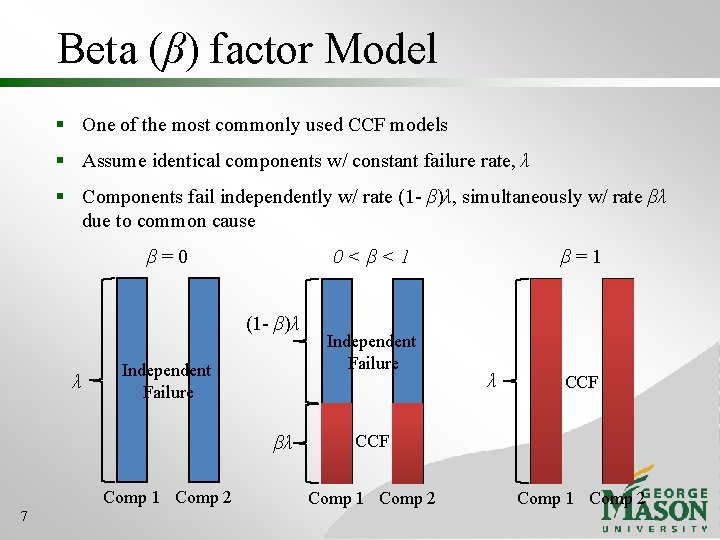

Beta (β) factor Model § One of the most commonly used CCF models § Assume identical components w/ constant failure rate, λ § Components fail independently w/ rate (1 - β)λ, simultaneously w/ rate βλ due to common cause β=0 0<β<1 (1 - β)λ λ Independent Failure βλ Comp 1 Comp 2 7 Independent Failure β=1 λ CCF Comp 1 Comp 2

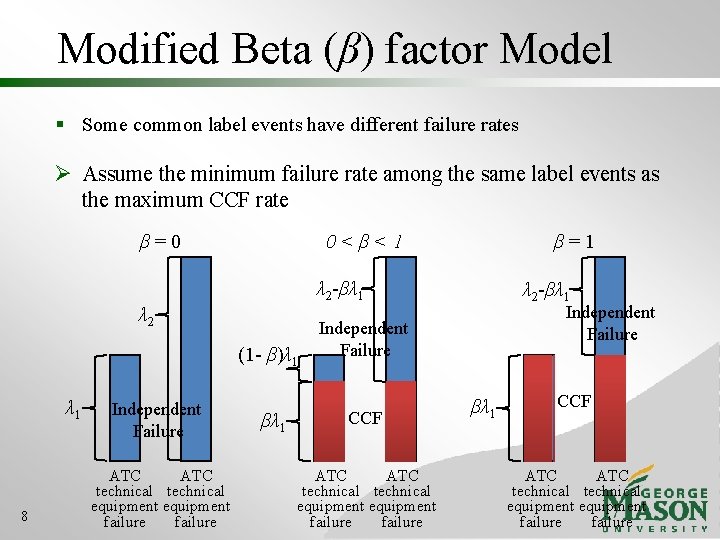

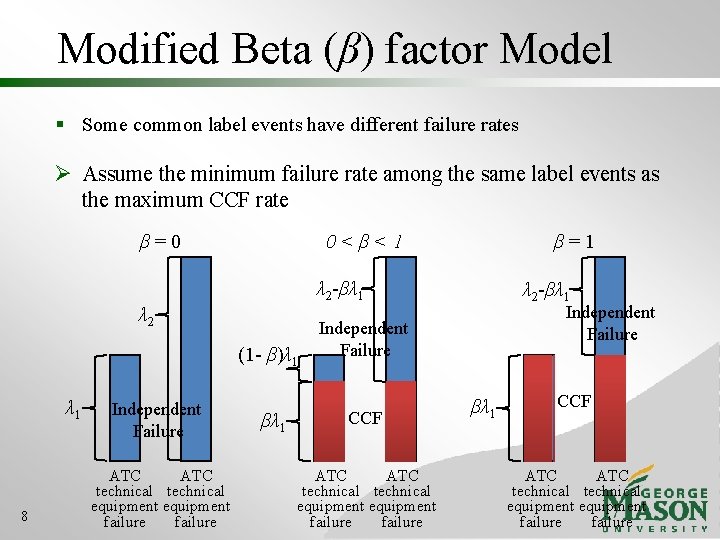

Modified Beta (β) factor Model § Some common label events have different failure rates Ø Assume the minimum failure rate among the same label events as the maximum CCF rate β=0 0<β<1 β=1 λ 2 -βλ 1 λ 2 (1 - β)λ 1 8 Independent Failure ATC technical equipment failure βλ 1 λ 2 -βλ 1 Independent Failure CCF ATC technical equipment failure βλ 1 CCF ATC technical equipment failure

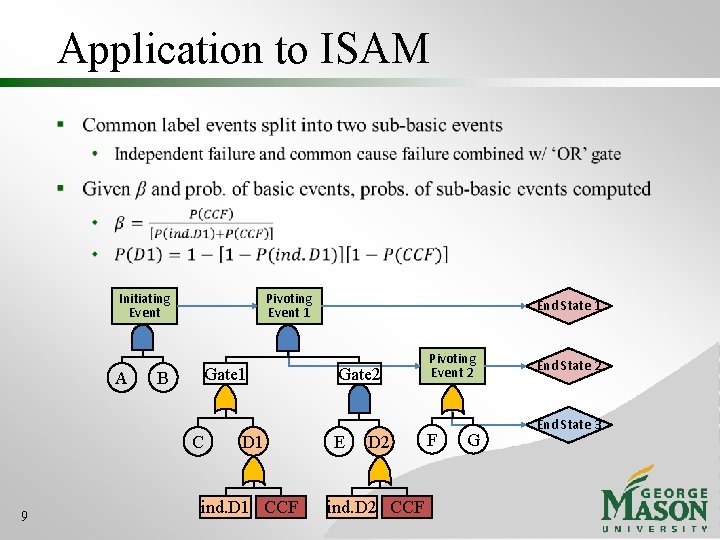

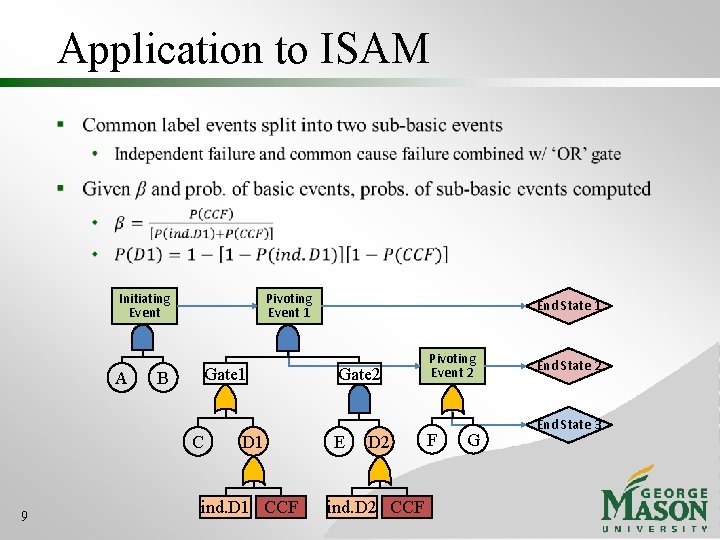

Application to ISAM Initiating Event A Pivoting Event 1 Gate 1 B C 9 D 1 ind. D 1 CCF End State 1 Gate 2 E D 2 ind. D 2 CCF Pivoting Event 2 F G End State 2 End State 3

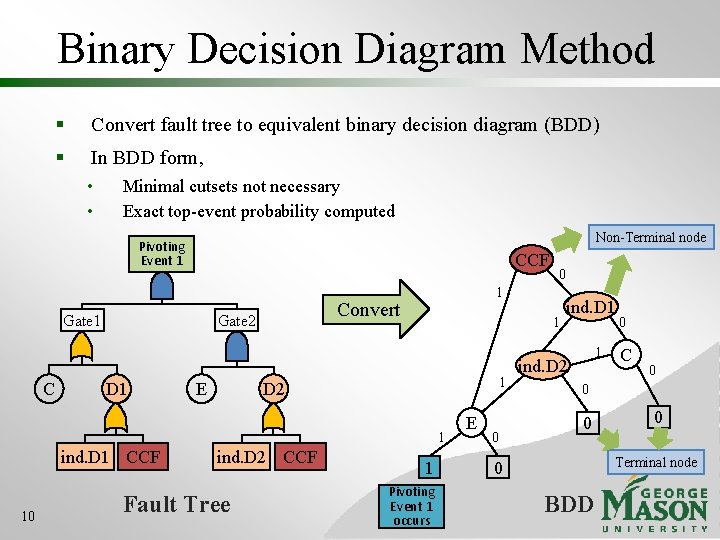

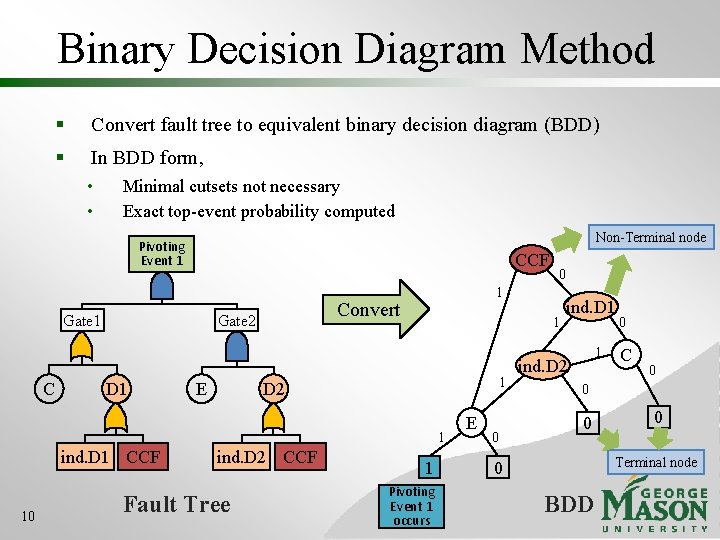

Binary Decision Diagram Method § Convert fault tree to equivalent binary decision diagram (BDD) § In BDD form, • • Minimal cutsets not necessary Exact top-event probability computed Non-Terminal node Pivoting Event 1 CCF Gate 1 C D 1 E 1 Convert Gate 2 1 1 D 2 1 ind. D 1 CCF 10 ind. D 2 CCF Fault Tree 0 1 Pivoting Event 1 occurs E 0 ind. D 1 1 ind. D 2 0 C 0 0 Terminal node 0 BDD

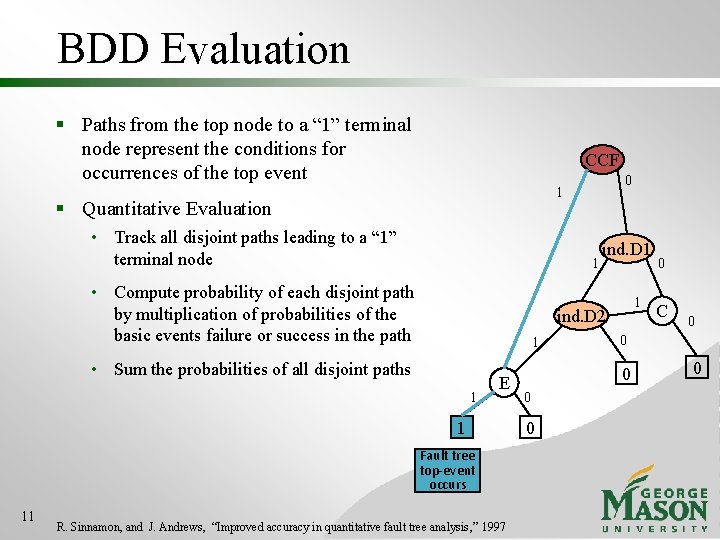

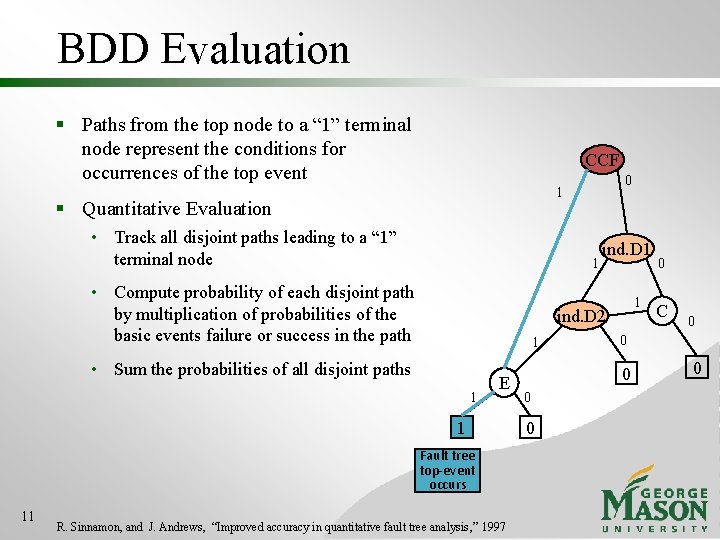

BDD Evaluation § Paths from the top node to a “ 1” terminal node represent the conditions for occurrences of the top event CCF § Quantitative Evaluation • Track all disjoint paths leading to a “ 1” terminal node 1 • Compute probability of each disjoint path by multiplication of probabilities of the basic events failure or success in the path ind. D 1 1 ind. D 2 1 • Sum the probabilities of all disjoint paths 1 E 1 Fault tree top-event occurs 11 0 1 R. Sinnamon, and J. Andrews, “Improved accuracy in quantitative fault tree analysis , ” 1997 0 C 0 0 0

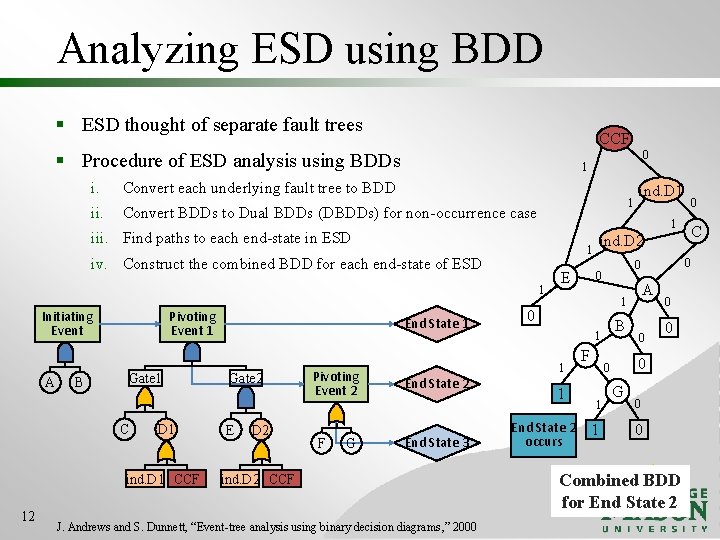

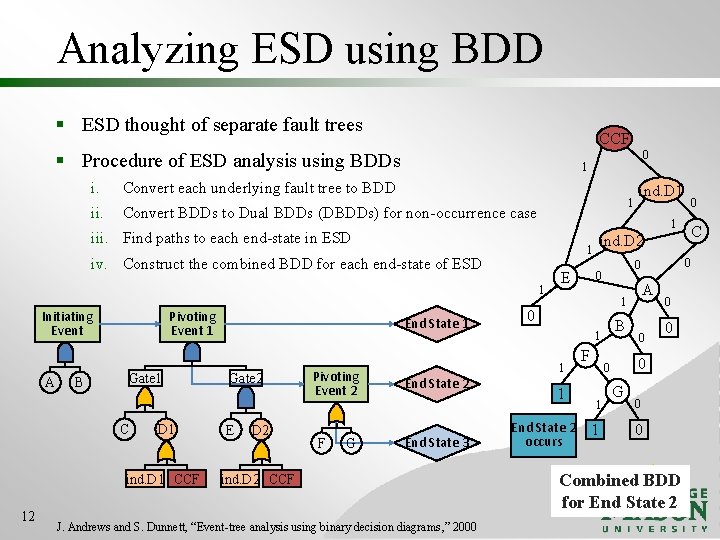

Analyzing ESD using BDD § ESD thought of separate fault trees CCF § Procedure of ESD analysis using BDDs i. Convert each underlying fault tree to BDD ii. Convert BDDs to Dual BDDs (DBDDs) for non-occurrence case 1 1 A B Gate 1 C D 1 ind. D 1 CCF 12 End State 1 Gate 2 E D 2 Pivoting Event 2 F G End State 2 End State 3 ind. D 2 CCF J. Andrews and S. Dunnett, “Event-tree analysis using binary decision diagrams, ” 2000 ind. D 2 1 iv. Construct the combined BDD for each end-state of ESD Pivoting Event 1 ind. D 1 1 iii. Find paths to each end-state in ESD Initiating Event 0 1 E A 1 0 B 1 1 1 End State 2 occurs F 1 1 0 0 0 G C 0 0 0 Combined BDD for End State 2

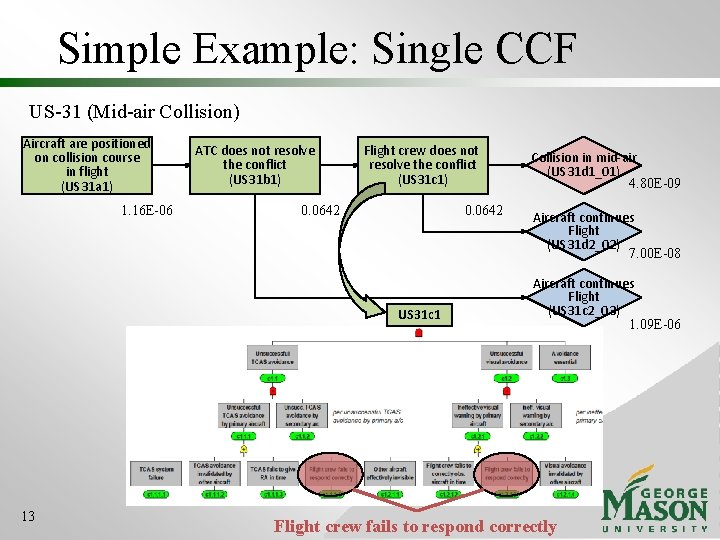

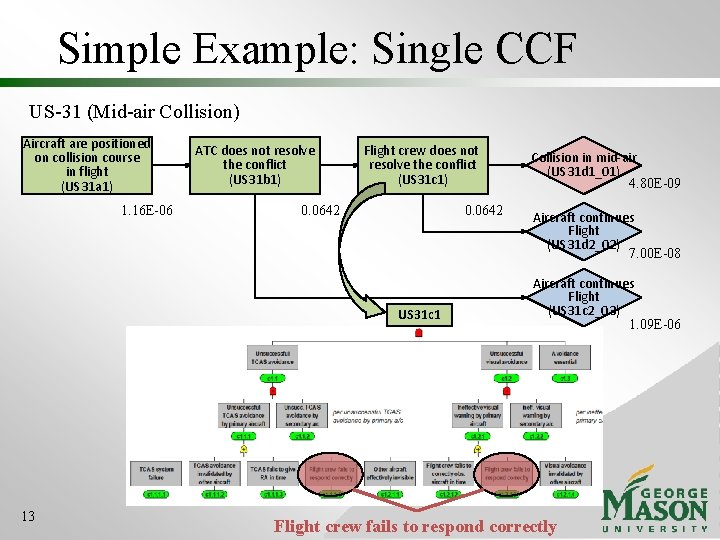

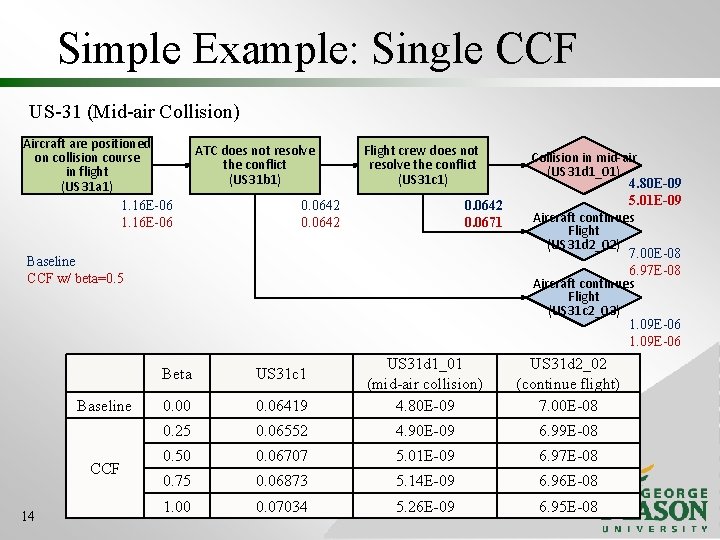

Simple Example: Single CCF US-31 (Mid-air Collision) Aircraft are positioned on collision course in flight (US 31 a 1) 1. 16 E-06 ATC does not resolve the conflict (US 31 b 1) Flight crew does not resolve the conflict (US 31 c 1) 0. 0642 US 31 c 1 13 Collision in mid-air (US 31 d 1_01) 4. 80 E-09 Aircraft continues Flight (US 31 d 2_02) 7. 00 E-08 Aircraft continues Flight (US 31 c 2_03) 1. 09 E-06 Flight crew fails to respond correctly

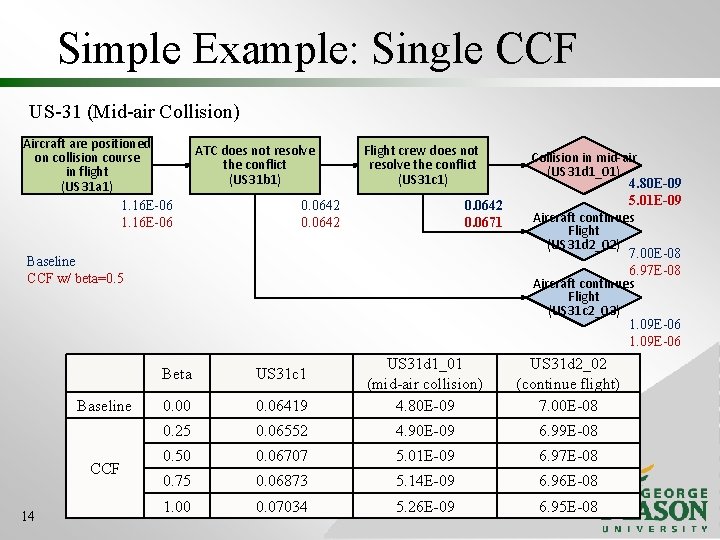

Simple Example: Single CCF US-31 (Mid-air Collision) Aircraft are positioned on collision course in flight (US 31 a 1) 1. 16 E-06 ATC does not resolve the conflict (US 31 b 1) Flight crew does not resolve the conflict (US 31 c 1) 0. 0642 0. 0671 Baseline CCF w/ beta=0. 5 Baseline CCF 14 Collision in mid-air (US 31 d 1_01) 4. 80 E-09 5. 01 E-09 Aircraft continues Flight (US 31 d 2_02) 7. 00 E-08 6. 97 E-08 Aircraft continues Flight (US 31 c 2_03) 1. 09 E-06 0. 06419 US 31 d 1_01 (mid-air collision) 4. 80 E-09 US 31 d 2_02 (continue flight) 7. 00 E-08 0. 25 0. 06552 4. 90 E-09 6. 99 E-08 0. 50 0. 06707 5. 01 E-09 6. 97 E-08 0. 75 0. 06873 5. 14 E-09 6. 96 E-08 1. 00 0. 07034 5. 26 E-09 6. 95 E-08 Beta US 31 c 1 0. 00

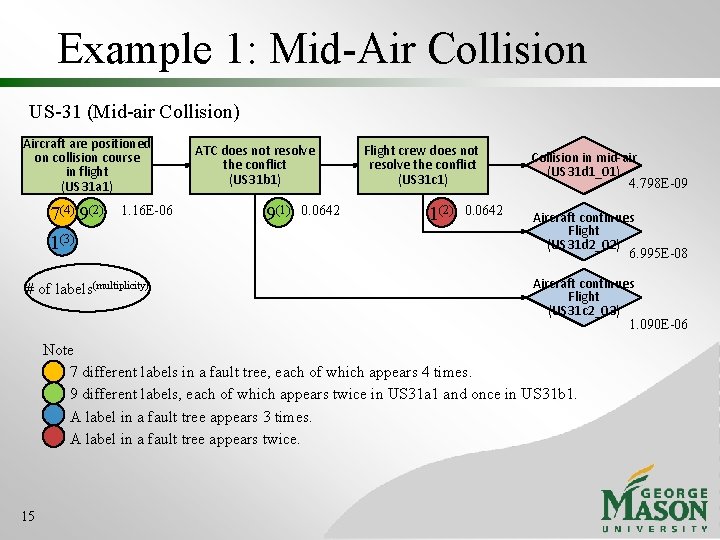

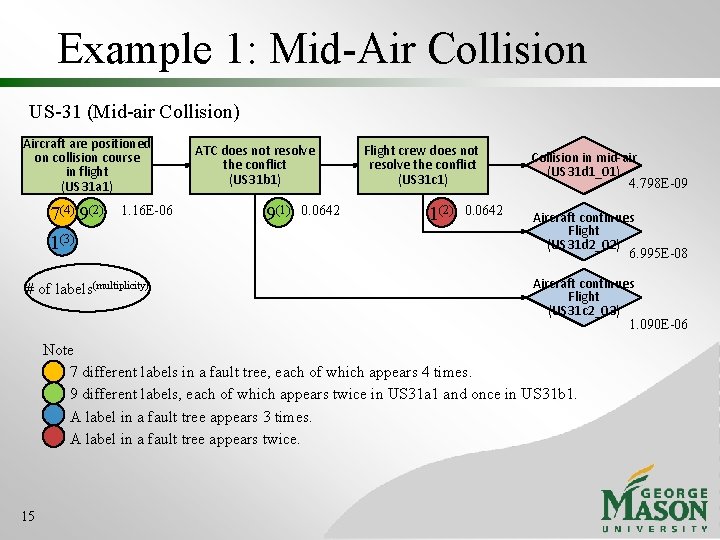

Example 1: Mid-Air Collision US-31 (Mid-air Collision) Aircraft are positioned on collision course in flight (US 31 a 1) 7(4) 9(2) 1(3) 1. 16 E-06 # of labels(multiplicity) ATC does not resolve the conflict (US 31 b 1) 9(1) 0. 0642 Flight crew does not resolve the conflict (US 31 c 1) 1(2) 0. 0642 Collision in mid-air (US 31 d 1_01) 4. 798 E-09 Aircraft continues Flight (US 31 d 2_02) 6. 995 E-08 Aircraft continues Flight (US 31 c 2_03) 1. 090 E-06 Note 7 different labels in a fault tree, each of which appears 4 times. 9 different labels, each of which appears twice in US 31 a 1 and once in US 31 b 1. A label in a fault tree appears 3 times. A label in a fault tree appears twice. 15

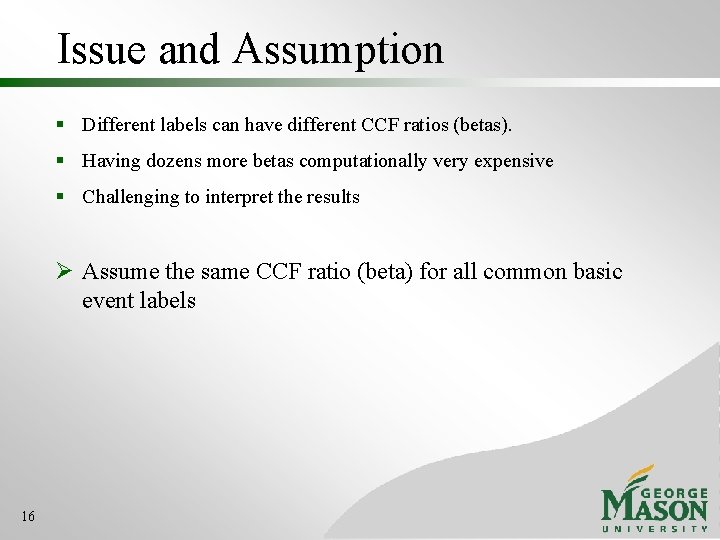

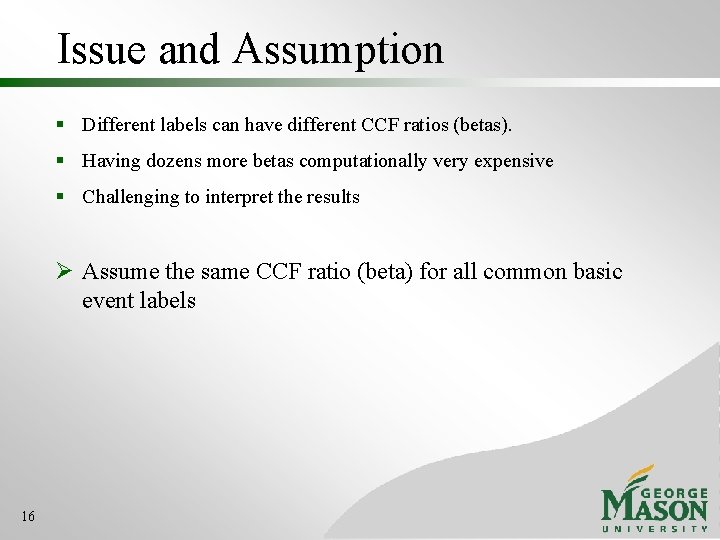

Issue and Assumption § Different labels can have different CCF ratios (betas). § Having dozens more betas computationally very expensive § Challenging to interpret the results Ø Assume the same CCF ratio (beta) for all common basic event labels 16

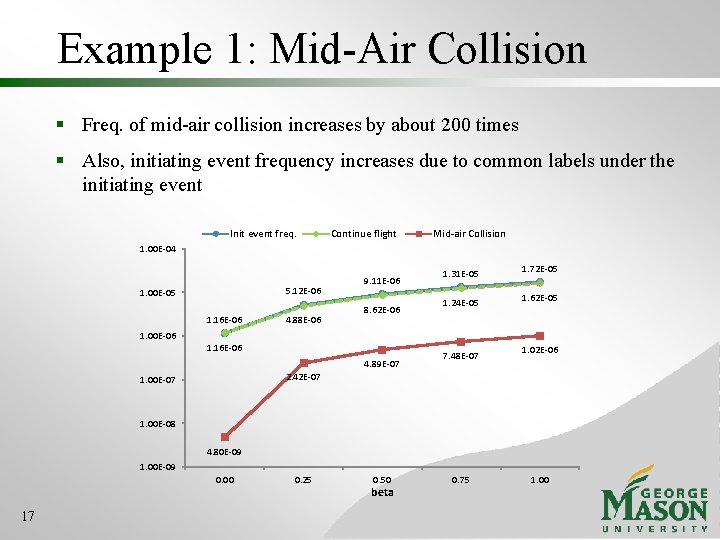

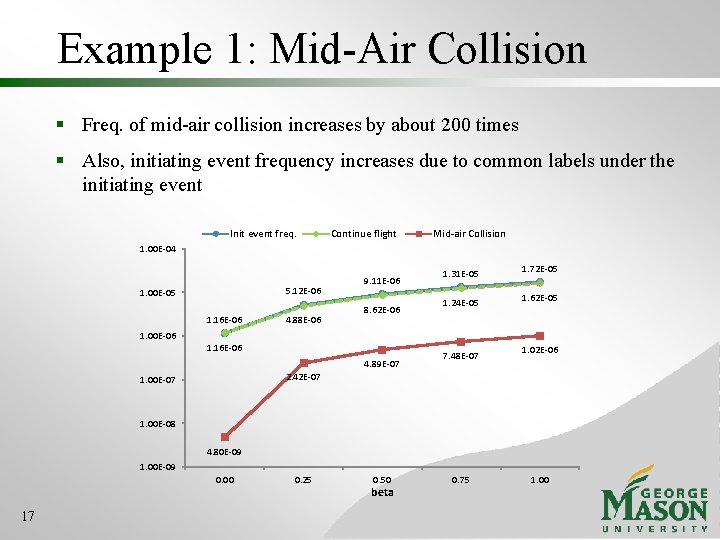

Example 1: Mid-Air Collision § Freq. of mid-air collision increases by about 200 times § Also, initiating event frequency increases due to common labels under the initiating event Init event freq. Continue flight Mid-air Collision 1. 00 E-04 5. 12 E-06 1. 00 E-05 1. 16 E-06 1. 00 E-06 4. 88 E-06 9. 11 E-06 8. 62 E-06 1. 16 E-06 4. 89 E-07 1. 31 E-05 1. 24 E-05 7. 48 E-07 1. 72 E-05 1. 62 E-05 1. 02 E-06 2. 42 E-07 1. 00 E-08 4. 80 E-09 1. 00 E-09 0. 00 17 0. 25 0. 50 beta 0. 75 1. 00

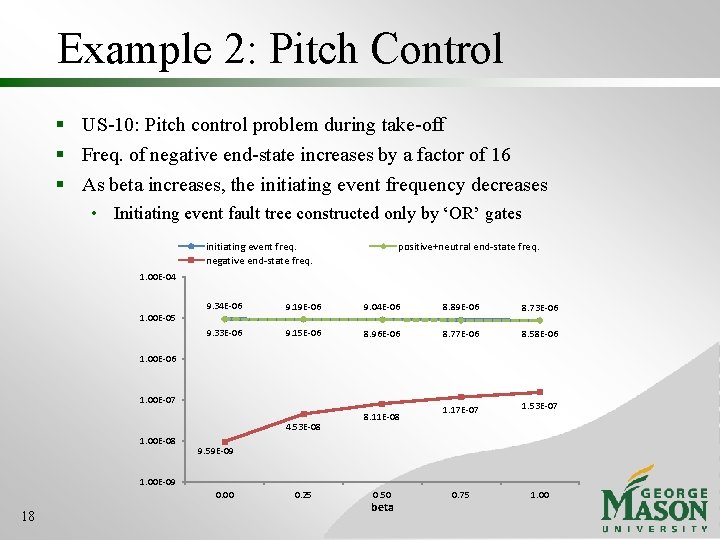

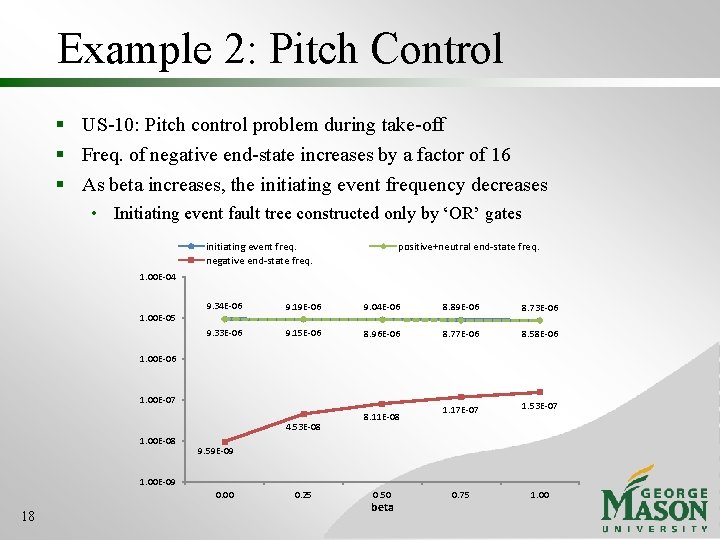

Example 2: Pitch Control § US-10: Pitch control problem during take-off § Freq. of negative end-state increases by a factor of 16 § As beta increases, the initiating event frequency decreases • Initiating event fault tree constructed only by ‘OR’ gates initiating event freq. negative end-state freq. positive+neutral end-state freq. 1. 00 E-04 1. 00 E-05 9. 34 E-06 9. 19 E-06 9. 04 E-06 8. 89 E-06 8. 73 E-06 9. 33 E-06 9. 15 E-06 8. 96 E-06 8. 77 E-06 8. 58 E-06 1. 17 E-07 1. 53 E-07 0. 75 1. 00 E-06 1. 00 E-07 4. 53 E-08 1. 00 E-08 8. 11 E-08 9. 59 E-09 1. 00 E-09 0. 00 18 0. 25 0. 50 beta

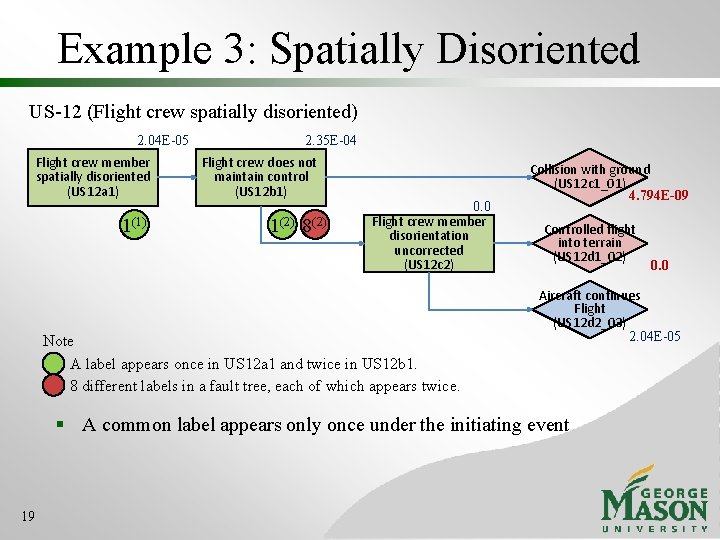

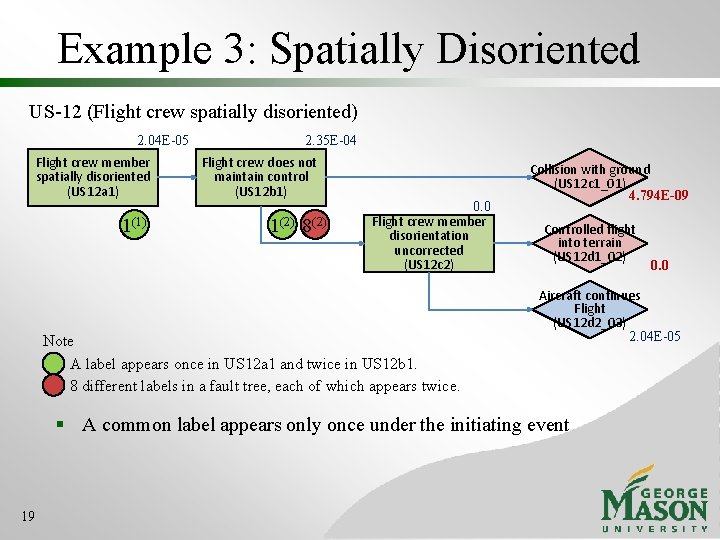

Example 3: Spatially Disoriented US-12 (Flight crew spatially disoriented) 2. 04 E-05 Flight crew member spatially disoriented (US 12 a 1) 1(1) 2. 35 E-04 Flight crew does not maintain control (US 12 b 1) 1(2) 8(2) 0. 0 Flight crew member disorientation uncorrected (US 12 c 2) Note A label appears once in US 12 a 1 and twice in US 12 b 1. 8 different labels in a fault tree, each of which appears twice. Collision with ground (US 12 c 1_01) 4. 794 E-09 Controlled flight into terrain (US 12 d 1_02) Aircraft continues Flight (US 12 d 2_03) 2. 04 E-05 § A common label appears only once under the initiating event 19 0. 0

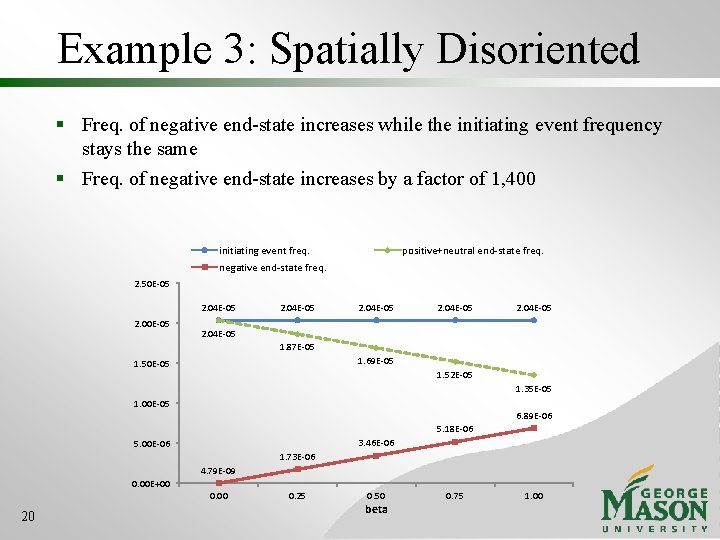

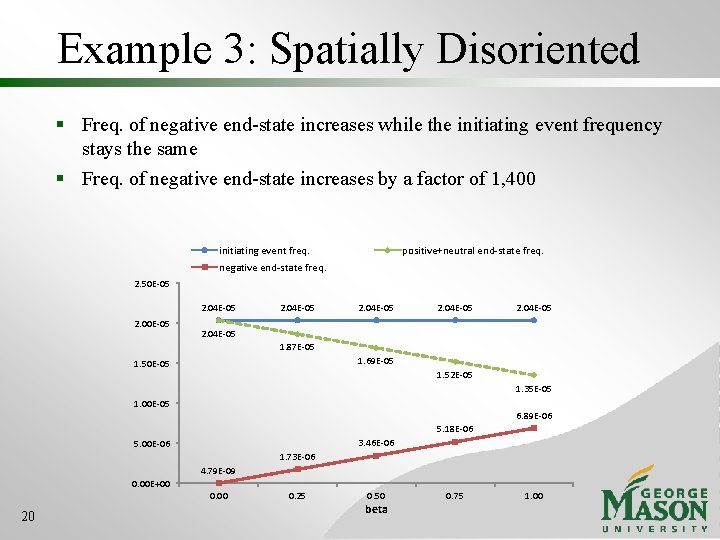

Example 3: Spatially Disoriented § Freq. of negative end-state increases while the initiating event frequency stays the same § Freq. of negative end-state increases by a factor of 1, 400 initiating event freq. positive+neutral end-state freq. negative end-state freq. 2. 50 E-05 2. 04 E-05 2. 04 E-05 1. 87 E-05 1. 69 E-05 1. 50 E-05 1. 52 E-05 1. 35 E-05 1. 00 E-05 6. 89 E-06 5. 18 E-06 3. 46 E-06 5. 00 E-06 1. 73 E-06 4. 79 E-09 0. 00 E+00 0. 00 20 0. 25 0. 50 beta 0. 75 1. 00

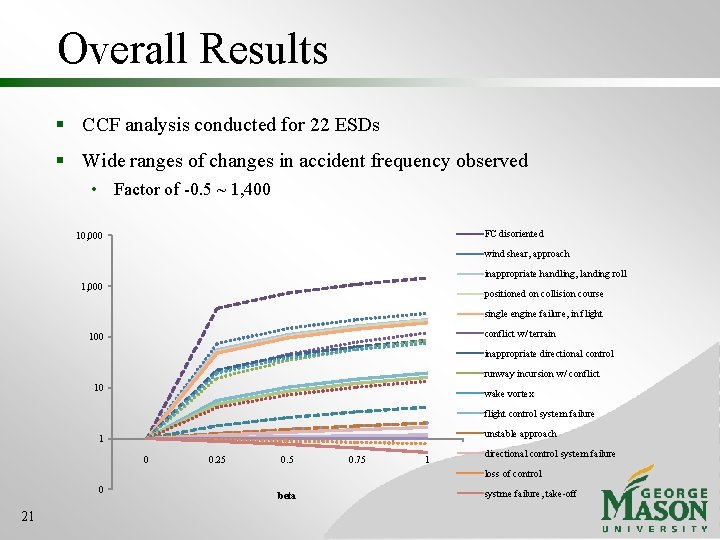

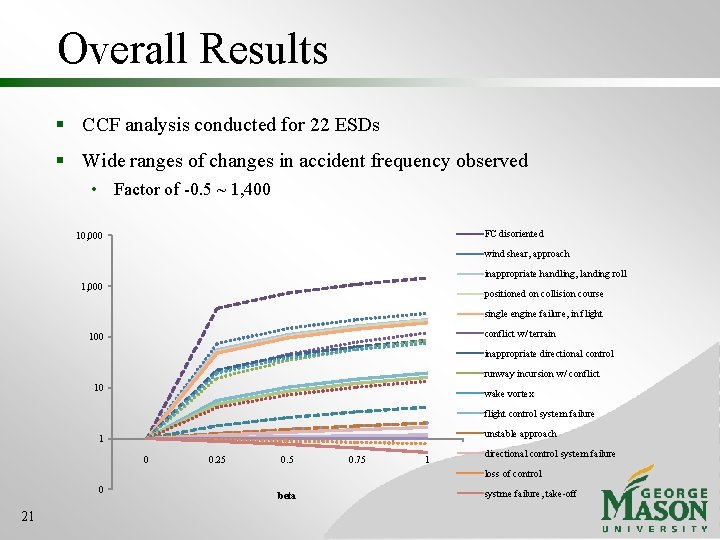

Overall Results § CCF analysis conducted for 22 ESDs § Wide ranges of changes in accident frequency observed • Factor of -0. 5 ~ 1, 400 FC disoriented 10, 000 wind shear, approach inappropriate handling, landing roll 1, 000 positioned on collision course single engine failure, in flight conflict w/ terrain 100 inappropriate directional control runway incursion w/ conflict 10 wake vortex flight control system failure unstable approach 1 0 0. 25 0. 75 1 directional control system failure loss of control 0 21 beta systme failure, take-off

Observations § Considering CCFs • Changes end-state frequencies possibly by a large amount, and • Changes initiating event frequency if common labels exist under the initiating event § Changes can decrease accident freq. due to fault tree structure • Constructed only by ‘OR’ gates § End-state frequencies approximately linear on β • Mathematically, not exactly linear • Very small probabilities make end-state frequencies close to linear § Computation time for each ESD varies 22 • Fraction of second ~ dozen hours • Depending on size of BDD (# of basic events, # of common labels, fault tree structure)

Conclusions & Future work § Modified beta (β) factor model with BDD method applied to analyze impacts of dependency in ISAM § Assuming dependency certainly impacts accident frequency quantification result in ISAM § Need detailed common cause failure study • Which events really occur simultaneously • How dependent between common label events § Allow CCFs across ESDs § Considering CCFs in modeling phase 23

Thank you! Question?