Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death

- Slides: 36

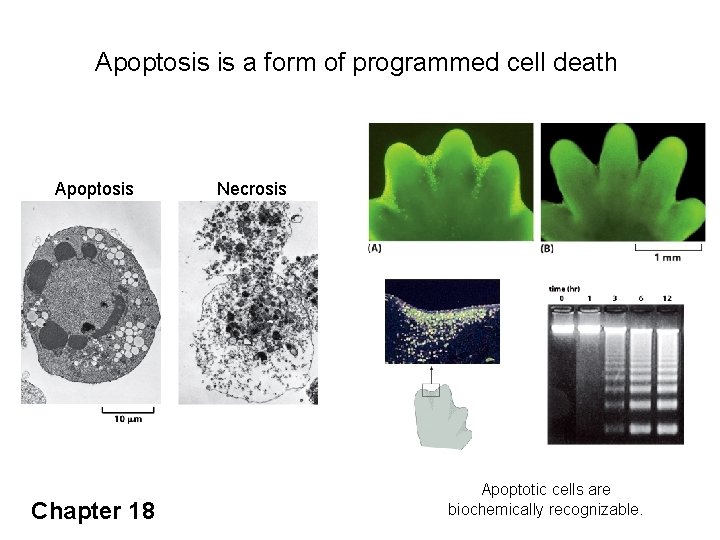

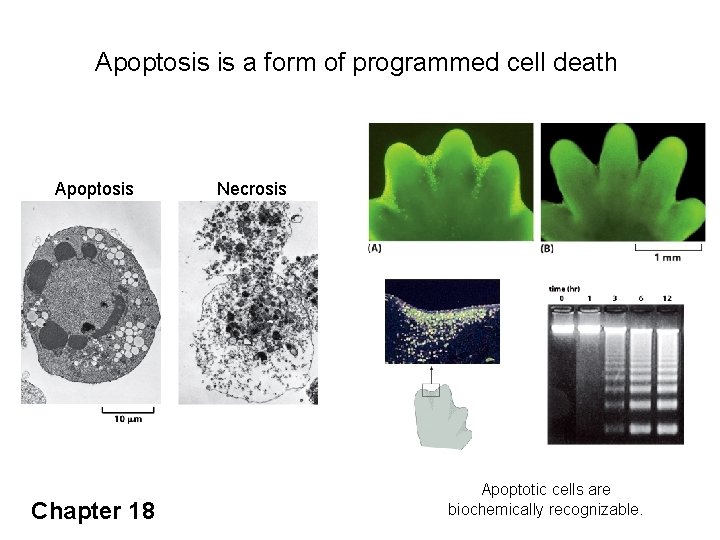

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death Apoptosis Necrosis Apoptosis is responsible for the formation of digits in the developing mouse paw. Chapter 18 Apoptotic cells are biochemically recognizable.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death * Programmed cell death removes unwanted cells during development. * Apoptotic cells are biochemically recognizable. * In apoptotic cells, phosphatidylserine flips from the inner leaflet to the outer and serves as an “eat me” signal to phagocytic cells. * Apoptosis depends upon an intracellular proteolytic cascade that is mediated by caspases. * The two best understood signaling pathways that can activate a caspase cascade are known as the extrinsic pathway and the intrinsic pathway. * The intrinsic pathway is regulated by a set of pro- and antiapoptotic proteins that are related to Bcl 2. * Either excessive or insufficient apoptosis can contribute to disease.

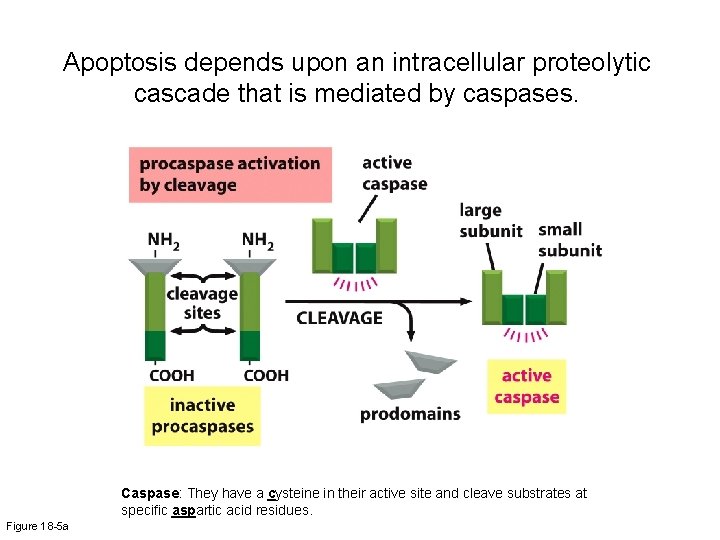

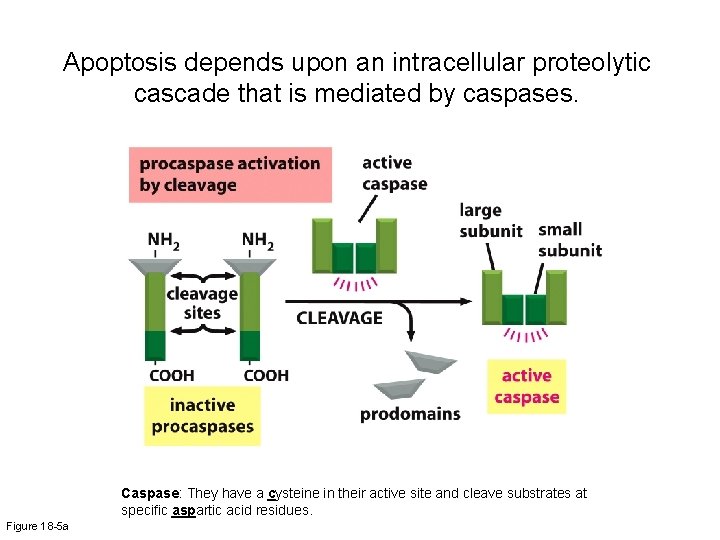

Apoptosis depends upon an intracellular proteolytic cascade that is mediated by caspases. Caspase: They have a cysteine in their active site and cleave substrates at specific aspartic acid residues. Figure 18 -5 a

Apoptosis depends upon an intracellular proteolytic cascade that is mediated by caspases. Initiator Executioner Targets Figure 18 -5 b

The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis Figure 18 -8

Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria during apoptosis Figure 18 -7

The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis Figure 18 -8

Pro-apoptotic Bcl 2 proteins stimulate the release of mitochondrial intermembrane proteins Figure 18 -9, 10

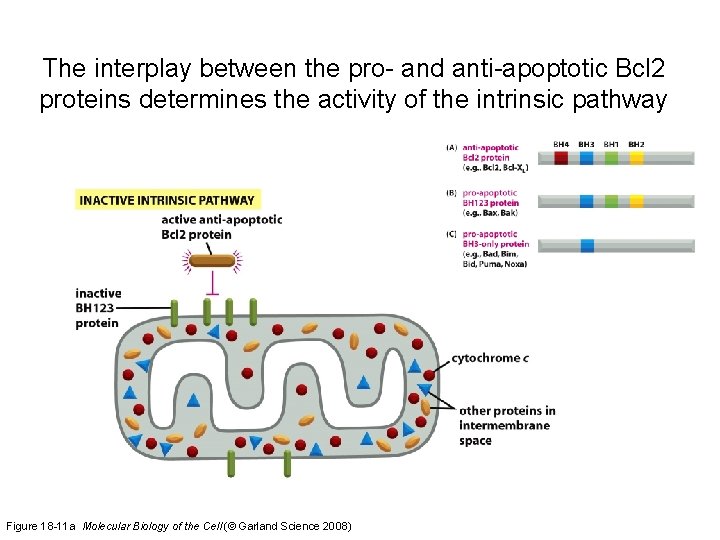

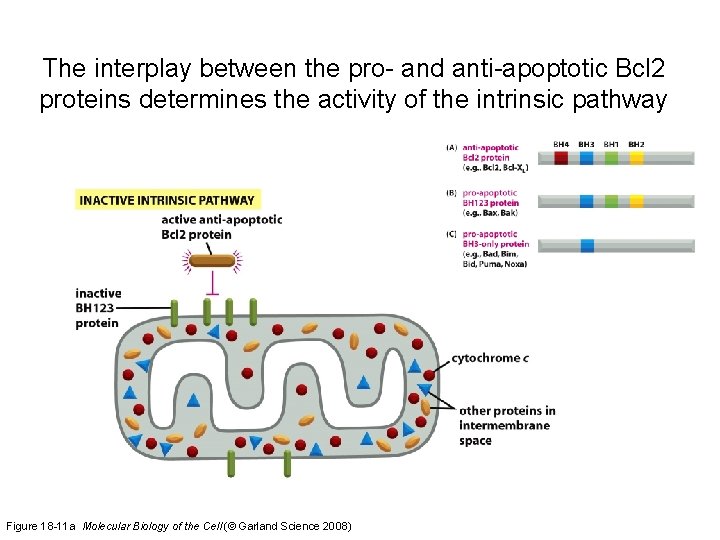

The interplay between the pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl 2 proteins determines the activity of the intrinsic pathway Figure 18 -11 a Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

The interplay between the pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl 2 proteins determines the activity of the intrinsic pathway Figure 18 -11 b Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Decreased apoptosis can contribute to tumorigenesis Figure 20 -14

CANCER * Cancers are monoclonal in origin and multiple mutations are generally required for their progression. * Tumor progression involves successive rounds of random inherited change followed by natural selection. * A small population of cancer stem cells can be responsible for the maintenance of tumors. * Tumor metastasis is a complex, multi-step process. * Cancer-critical genes fall into two major classes: oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. * Cancer progression typically involves changes in both of these types of genes * The Rb and p 53 proteins are two of the most important tumor suppressor gene products for human cancer.

Cancers are generally monoclonal in origin Evidence from X-inactivation mosaics that demonstrates the monoclonal origin of cancers. Figure 20 -6 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Cancer incidence increases with age Figure 20 -7 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Tumor progression involves successive rounds of random inherited change followed by natural selection Figure 20 -11 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Oncogene collaboration in mice: Further evidence for the requirement for multiple mutations during tumor formation Figure 20 -36

Cancers may arise from cancer stem cells Figure 20 -16 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Tumor metastasis is a complex multi-step process Fig 20 -17

An assay used to detect the presence of an oncogene: the loss of contact inhibition in culture Figure 20 -29 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Some of the major pathway relevant to cancer in human cells Figure 20 -37 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Distinct pathways may mediate the disregulation of cell-cycle progression and the disregulation of cell growth in cancer cells Figure 20 -39 a Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Dominant & recessive mutations that contribute to cancer Figure 20 -27

The types of events that can make a proto-oncogene overactive and convert it into an oncogene. Figure 20 -33 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) & the Philadelphia chromosome Figure 20 -5 (Hyperactive Abl) Figure 20 -51

Targeted therapy: the success of Gleevec Specifically targeting the Abl enzyme Binds to Abl in active site & “locks” the enzyme into an inactive state Figure 20 -52 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Targeted therapy: the success of Gleevec Specifically targeting the Abl enzyme Figure 20 -52 c Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Multidrug Therapy: Combating Resistance Figure 20 -53 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

The genetic mechanisms that cause retinoblastoma Figure 20 -30 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Figure 20 -31 Examples of the ways in which the one good copy of a tumor suppressor locus might be lost through change in DNA sequence,

The loss of tumor suppression gene function can involve both genetic and epigenetic changes Figure 20 -32

A simplified view of the Rb pathway Figure 20 -38 a

The Rb protein inhibits entry into the cell cycle Figure 20 -38 b, c Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Mechanisms controlling cell-cycle entry and S-phase initiation in animal cells A central role for the Rb protein Figure 17 -62 Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Figure 17 -62 (part 1 of 3) Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

Figure 17 -62 (part 2 of 3) Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)

The inactivation of the Rb protein is needed for the entry into S-phase Figure 17 -62 (part 3 of 3) Molecular Biology of the Cell (© Garland Science 2008)