AP Chem Chapter 6 Electronic Structure and the

- Slides: 55

AP Chem Chapter 6 Electronic Structure and the Periodic Table

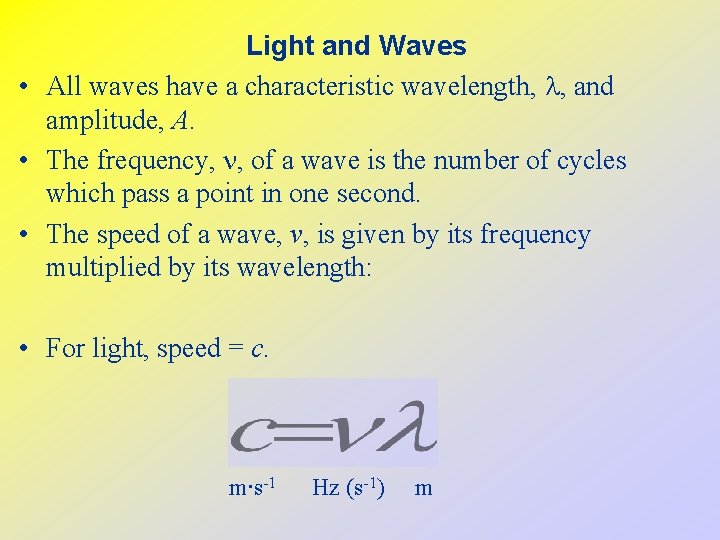

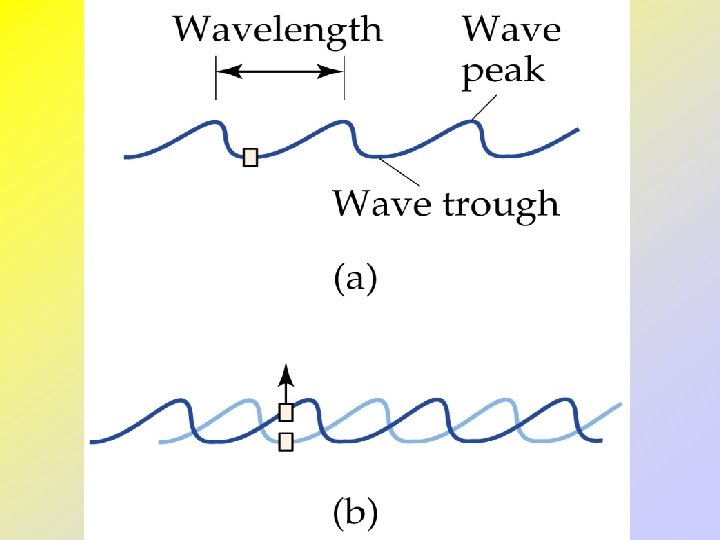

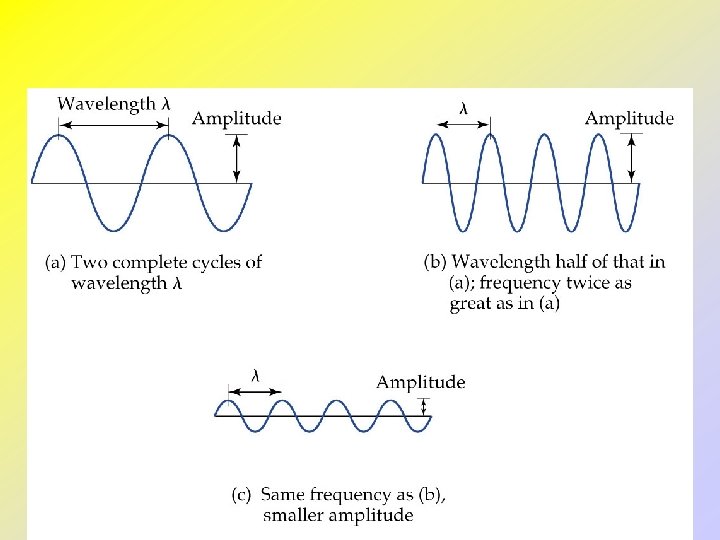

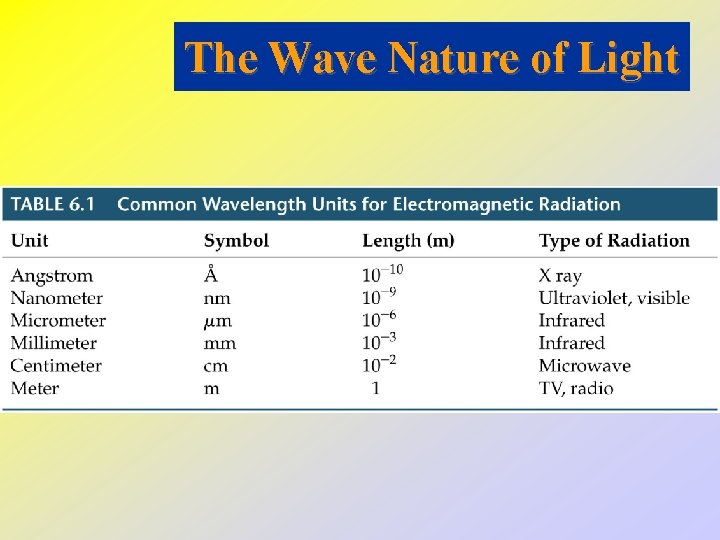

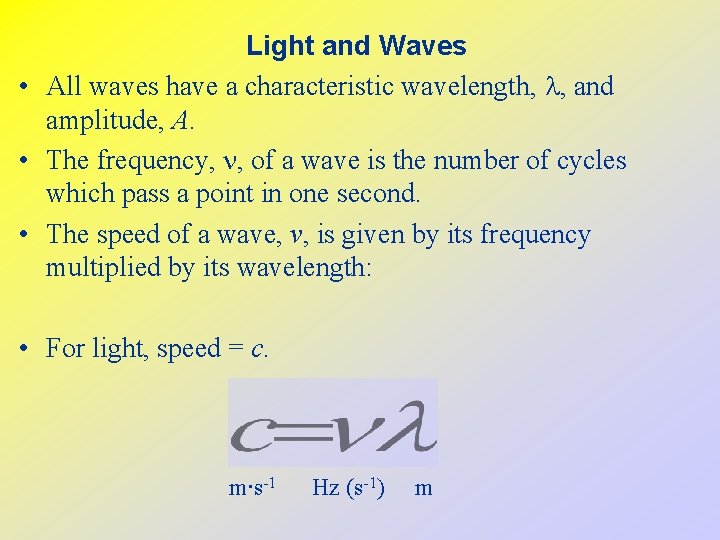

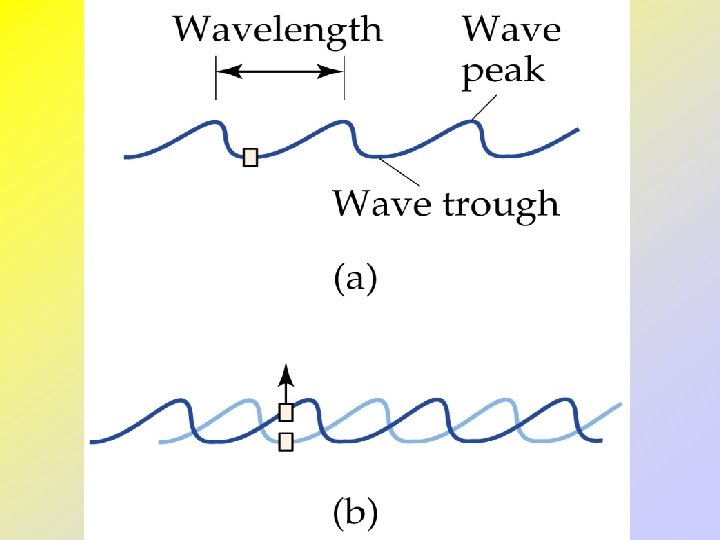

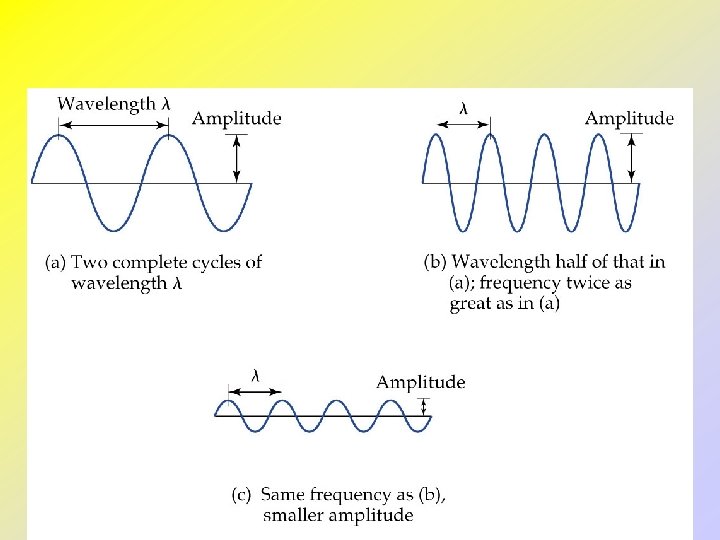

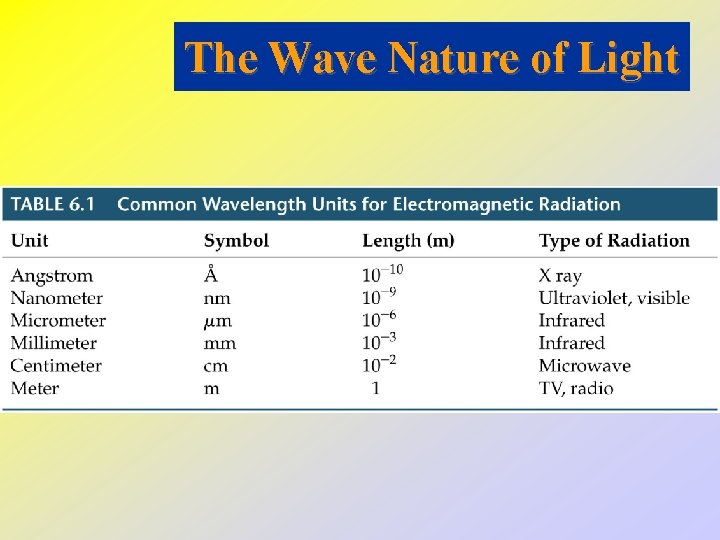

Light and Waves • All waves have a characteristic wavelength, , and amplitude, A. • The frequency, n, of a wave is the number of cycles which pass a point in one second. • The speed of a wave, v, is given by its frequency multiplied by its wavelength: • For light, speed = c. m∙s-1 Hz (s-1) m

• Modern atomic theory arose out of studies of the interaction of radiation (light) with matter. • Electromagnetic radiation moves through a vacuum with a speed of 2. 99792458 108 m/s. • Electromagnetic waves have characteristic wavelengths and frequencies. • Example: visible radiation has wavelengths between 400 nm (violet) and 750 nm (red).

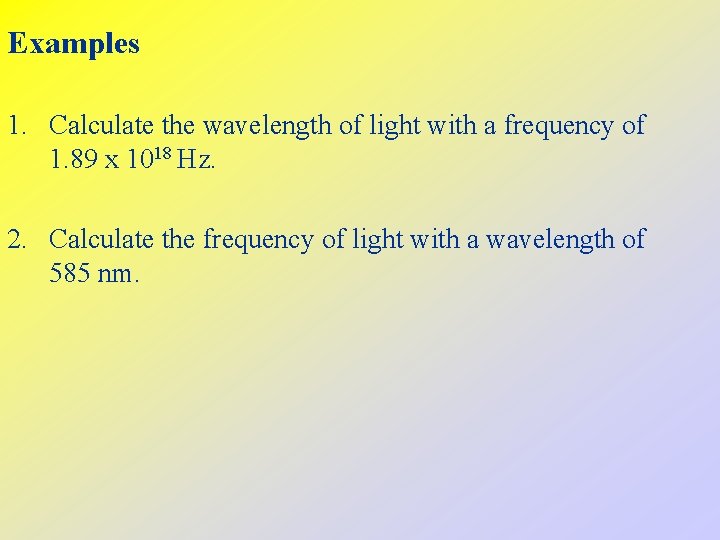

Examples 1. Calculate the wavelength of light with a frequency of 1. 89 x 1018 Hz. 2. Calculate the frequency of light with a wavelength of 585 nm.

The Wave Nature of Light

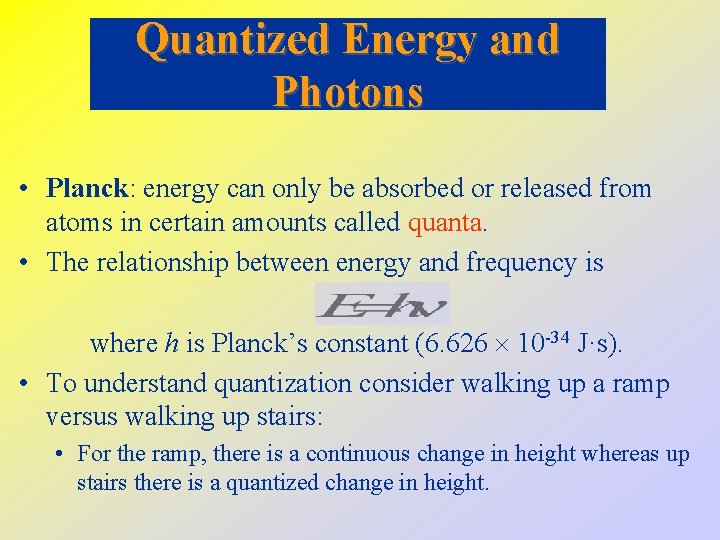

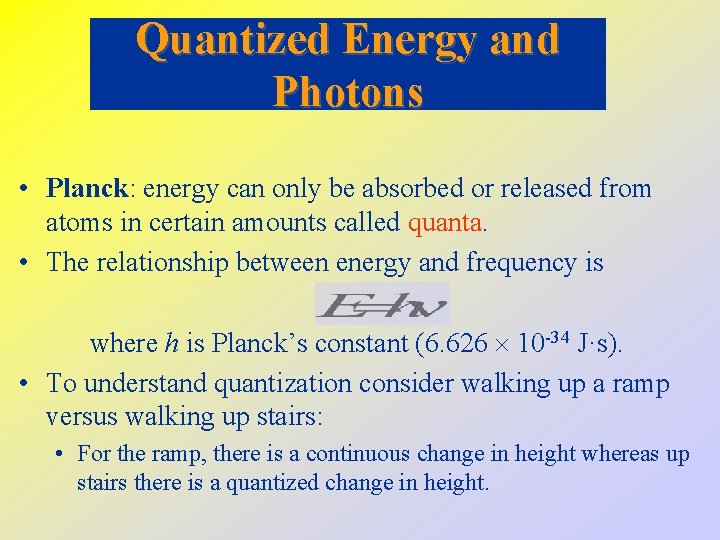

Quantized Energy and Photons • Planck: energy can only be absorbed or released from atoms in certain amounts called quanta. • The relationship between energy and frequency is where h is Planck’s constant (6. 626 10 -34 J·s). • To understand quantization consider walking up a ramp versus walking up stairs: • For the ramp, there is a continuous change in height whereas up stairs there is a quantized change in height.

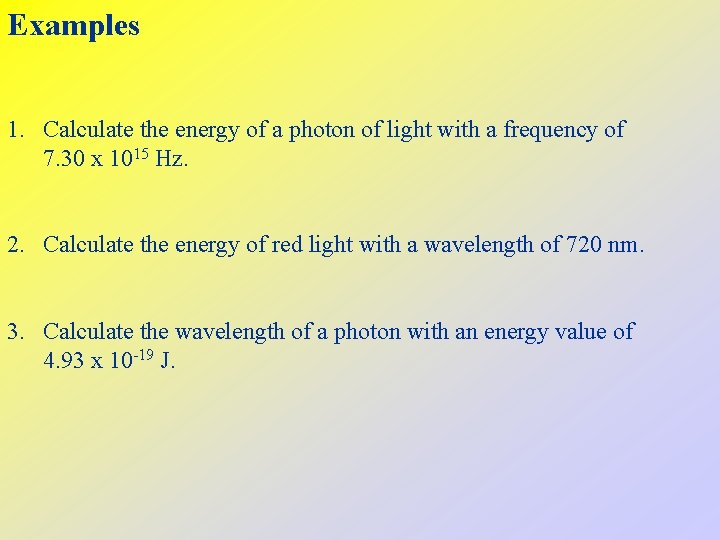

Examples 1. Calculate the energy of a photon of light with a frequency of 7. 30 x 1015 Hz. 2. Calculate the energy of red light with a wavelength of 720 nm. 3. Calculate the wavelength of a photon with an energy value of 4. 93 x 10 -19 J.

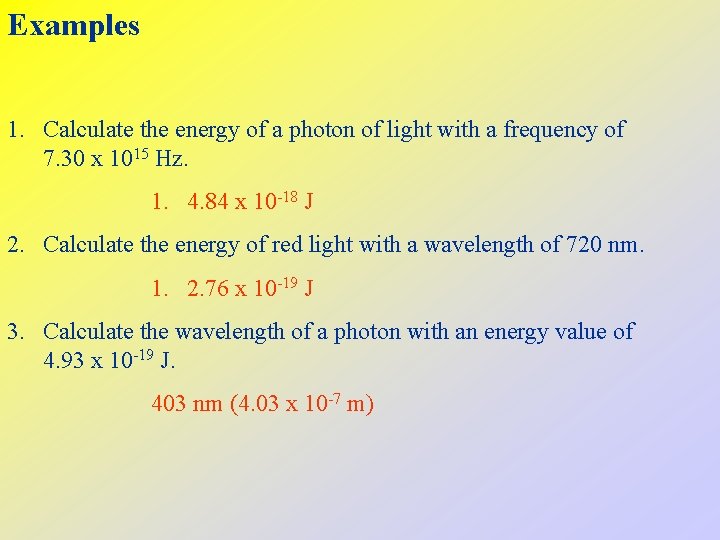

Examples 1. Calculate the energy of a photon of light with a frequency of 7. 30 x 1015 Hz. 1. 4. 84 x 10 -18 J 2. Calculate the energy of red light with a wavelength of 720 nm. 1. 2. 76 x 10 -19 J 3. Calculate the wavelength of a photon with an energy value of 4. 93 x 10 -19 J. 403 nm (4. 03 x 10 -7 m)

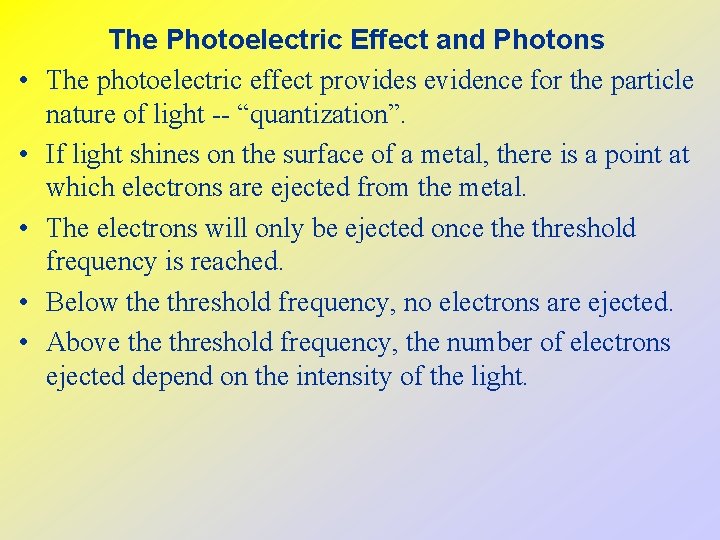

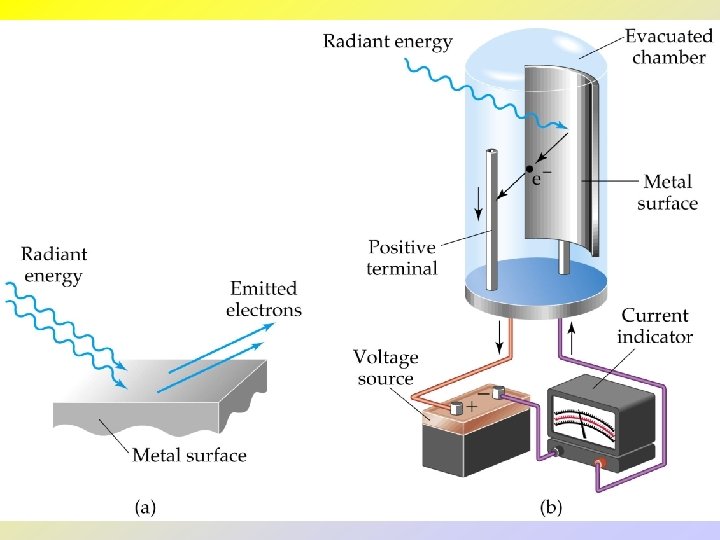

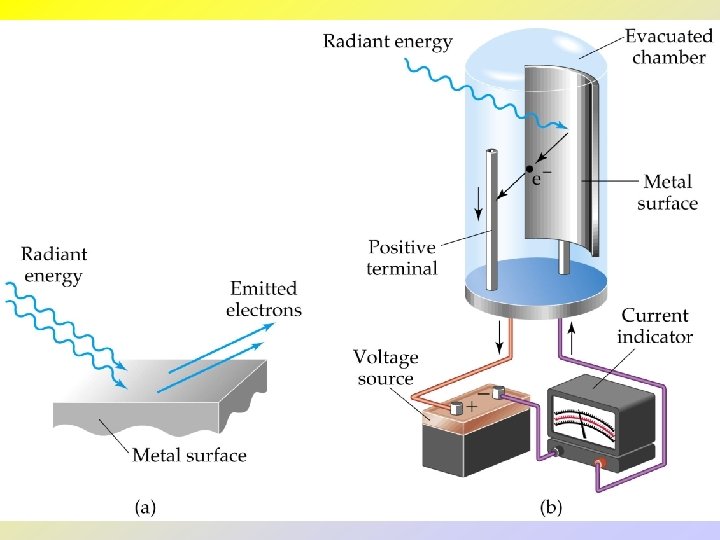

• • • The Photoelectric Effect and Photons The photoelectric effect provides evidence for the particle nature of light -- “quantization”. If light shines on the surface of a metal, there is a point at which electrons are ejected from the metal. The electrons will only be ejected once threshold frequency is reached. Below the threshold frequency, no electrons are ejected. Above threshold frequency, the number of electrons ejected depend on the intensity of the light.

• Einstein assumed that light traveled in energy packets called photons. • The energy of one photon:

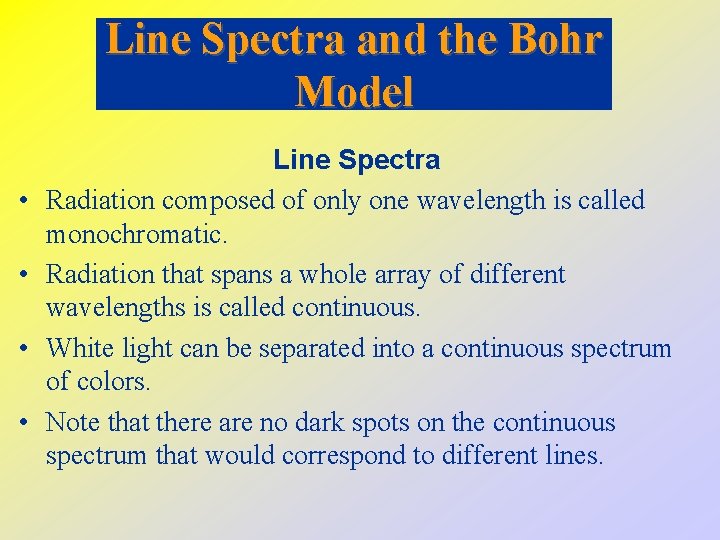

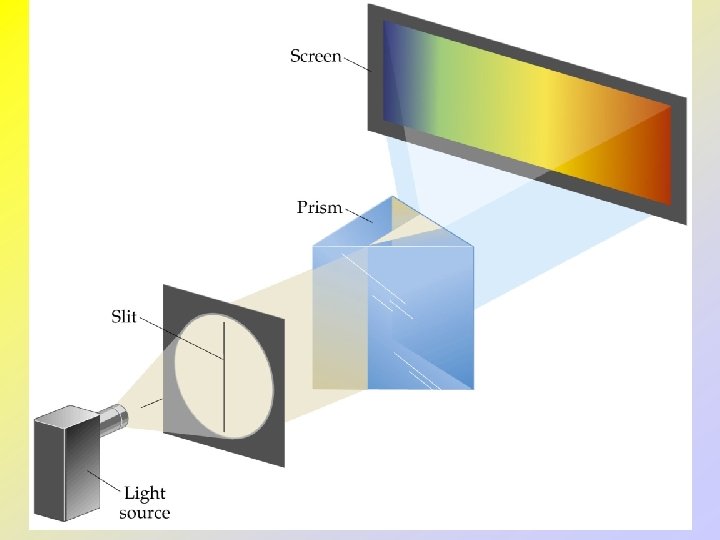

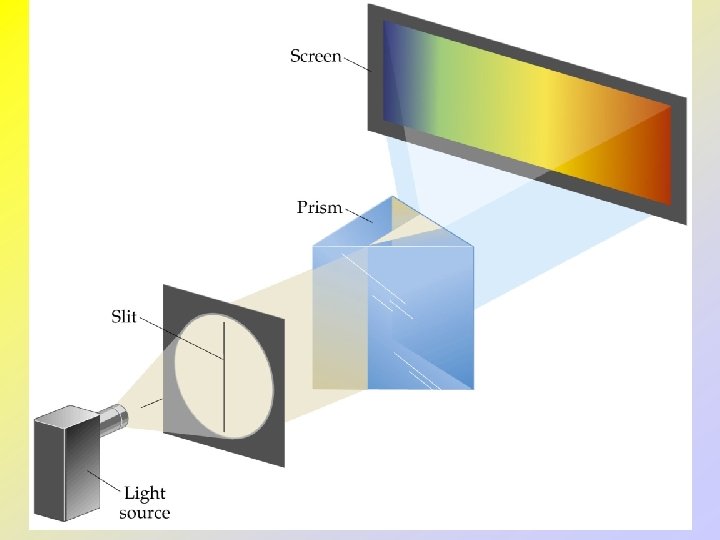

Line Spectra and the Bohr Model • • Line Spectra Radiation composed of only one wavelength is called monochromatic. Radiation that spans a whole array of different wavelengths is called continuous. White light can be separated into a continuous spectrum of colors. Note that there are no dark spots on the continuous spectrum that would correspond to different lines.

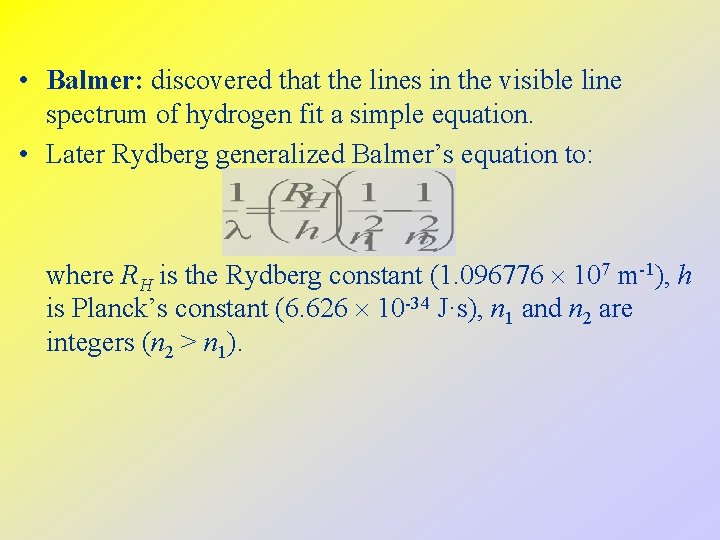

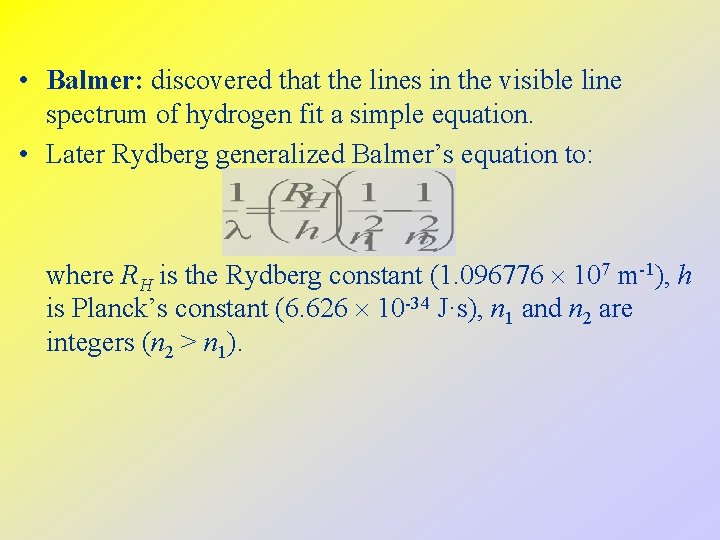

• Balmer: discovered that the lines in the visible line spectrum of hydrogen fit a simple equation. • Later Rydberg generalized Balmer’s equation to: where RH is the Rydberg constant (1. 096776 107 m-1), h is Planck’s constant (6. 626 10 -34 J·s), n 1 and n 2 are integers (n 2 > n 1).

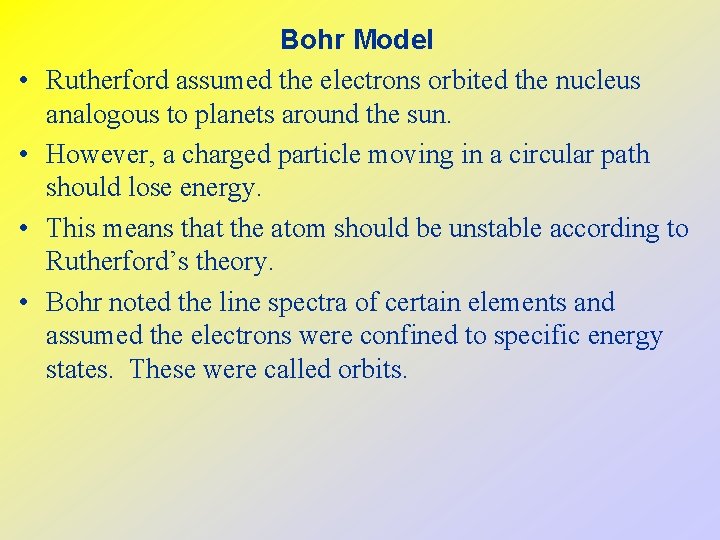

• • Bohr Model Rutherford assumed the electrons orbited the nucleus analogous to planets around the sun. However, a charged particle moving in a circular path should lose energy. This means that the atom should be unstable according to Rutherford’s theory. Bohr noted the line spectra of certain elements and assumed the electrons were confined to specific energy states. These were called orbits.

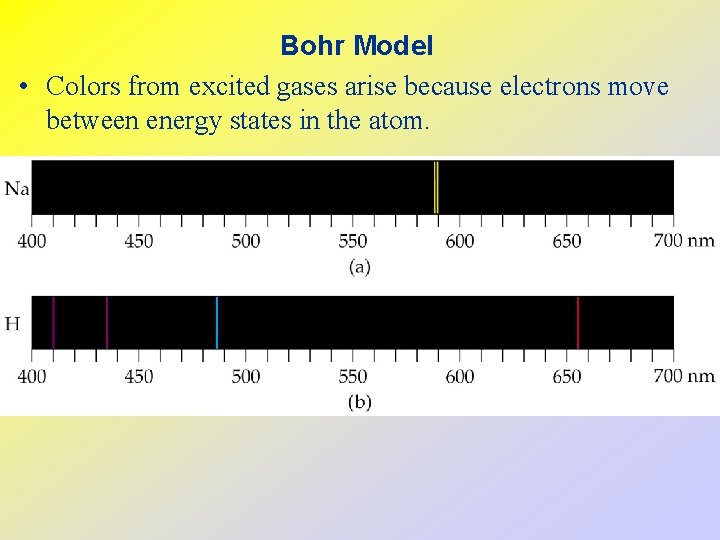

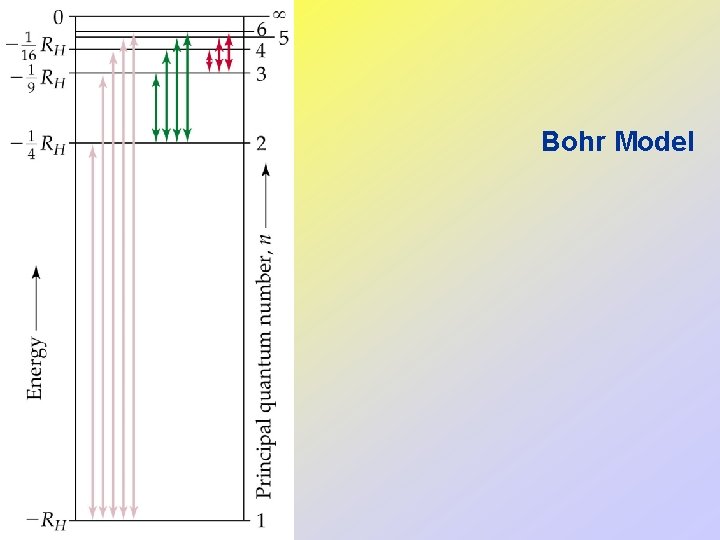

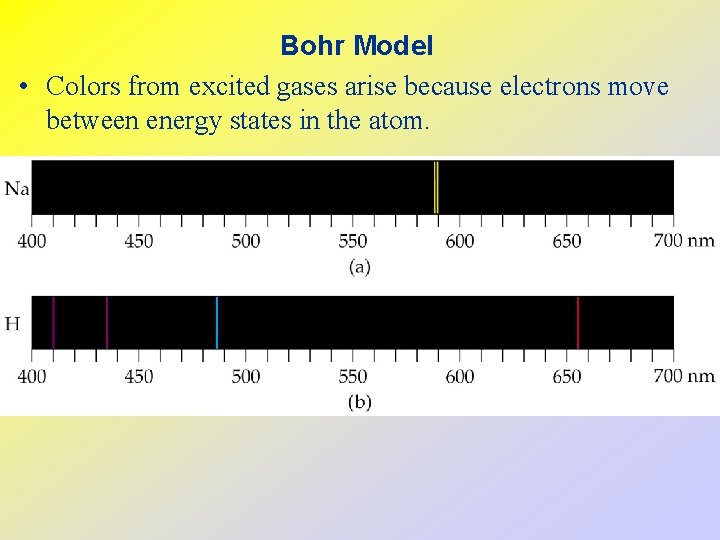

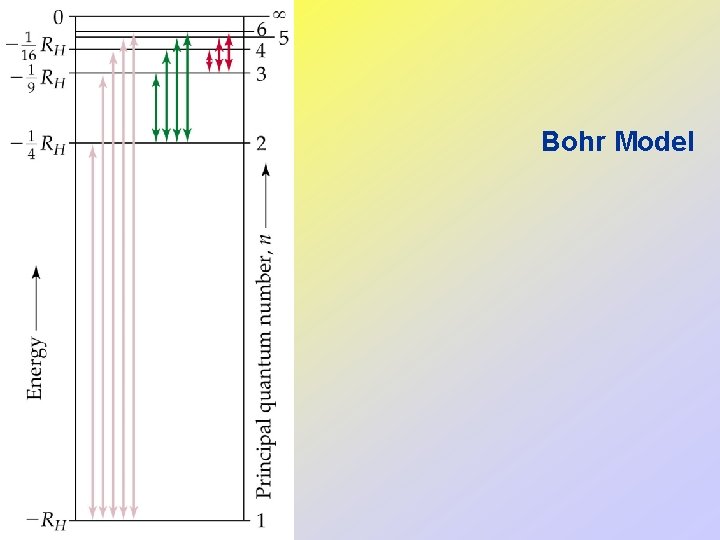

Bohr Model • Colors from excited gases arise because electrons move between energy states in the atom.

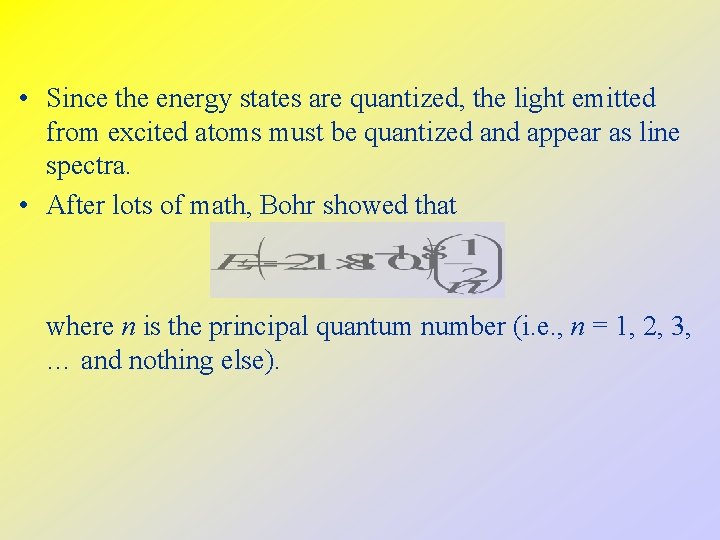

• Since the energy states are quantized, the light emitted from excited atoms must be quantized and appear as line spectra. • After lots of math, Bohr showed that where n is the principal quantum number (i. e. , n = 1, 2, 3, … and nothing else).

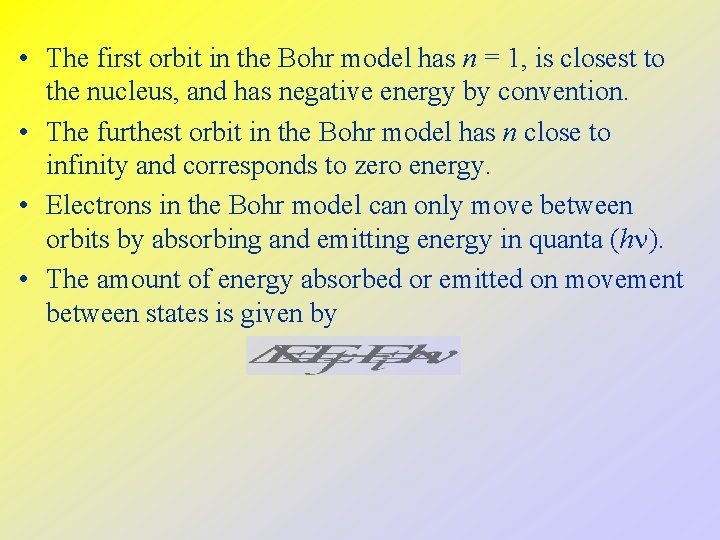

• The first orbit in the Bohr model has n = 1, is closest to the nucleus, and has negative energy by convention. • The furthest orbit in the Bohr model has n close to infinity and corresponds to zero energy. • Electrons in the Bohr model can only move between orbits by absorbing and emitting energy in quanta (hn). • The amount of energy absorbed or emitted on movement between states is given by

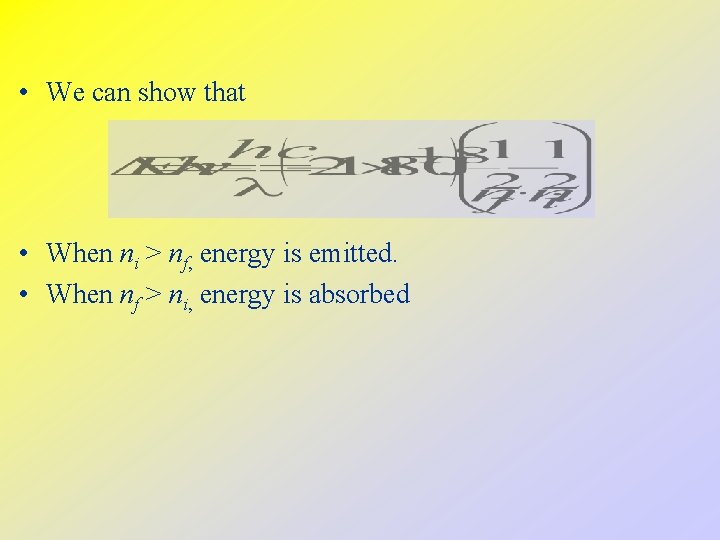

• We can show that • When ni > nf, energy is emitted. • When nf > ni, energy is absorbed

Bohr Model

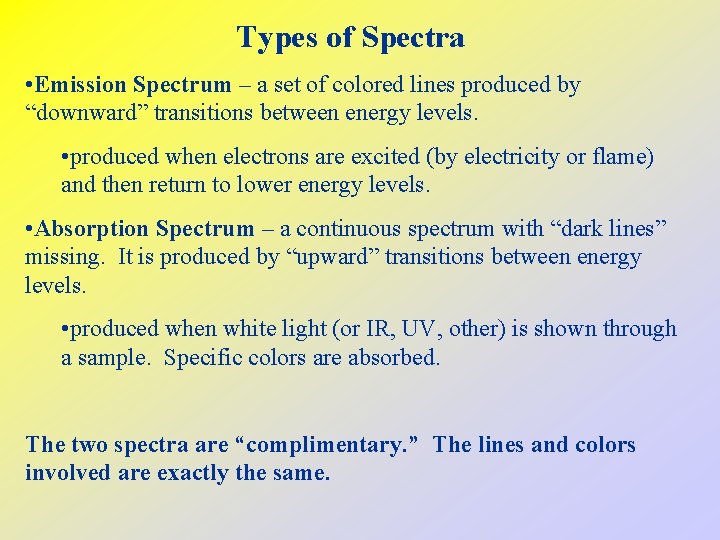

Types of Spectra • Emission Spectrum – a set of colored lines produced by “downward” transitions between energy levels. • produced when electrons are excited (by electricity or flame) and then return to lower energy levels. • Absorption Spectrum – a continuous spectrum with “dark lines” missing. It is produced by “upward” transitions between energy levels. • produced when white light (or IR, UV, other) is shown through a sample. Specific colors are absorbed. The two spectra are “complimentary. ” The lines and colors involved are exactly the same.

Limitations of the Bohr Model • Can only explain the line spectrum of hydrogen adequately. • Electrons are not completely described as small particles.

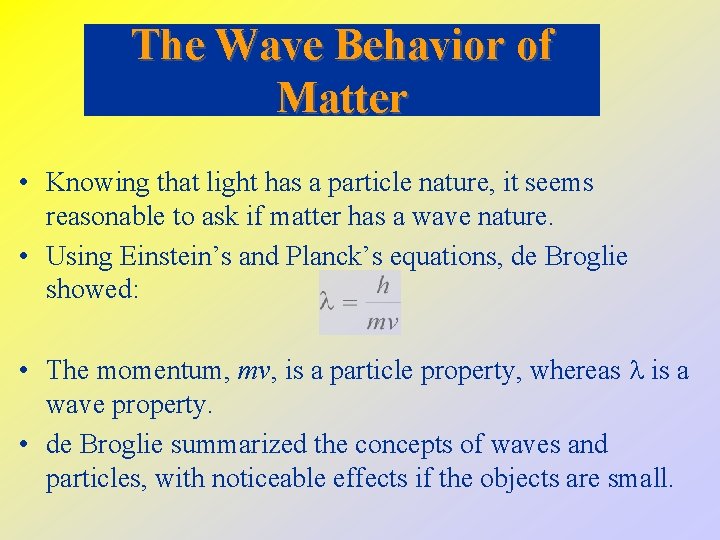

The Wave Behavior of Matter • Knowing that light has a particle nature, it seems reasonable to ask if matter has a wave nature. • Using Einstein’s and Planck’s equations, de Broglie showed: • The momentum, mv, is a particle property, whereas is a wave property. • de Broglie summarized the concepts of waves and particles, with noticeable effects if the objects are small.

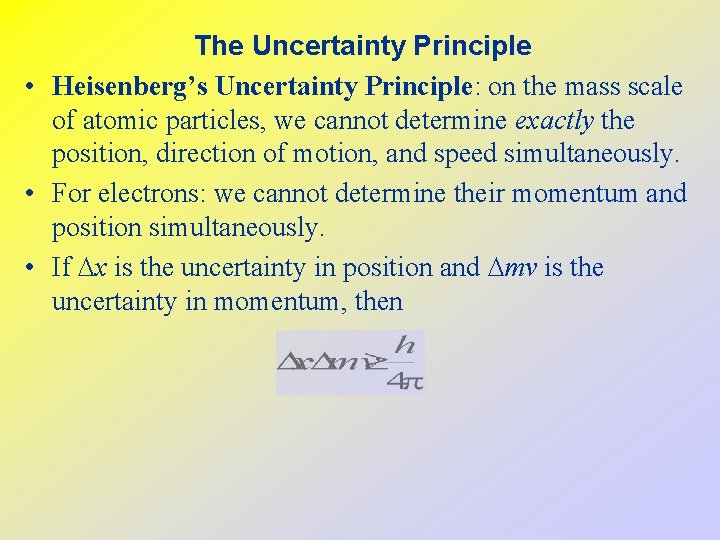

The Uncertainty Principle • Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle: on the mass scale of atomic particles, we cannot determine exactly the position, direction of motion, and speed simultaneously. • For electrons: we cannot determine their momentum and position simultaneously. • If Dx is the uncertainty in position and Dmv is the uncertainty in momentum, then

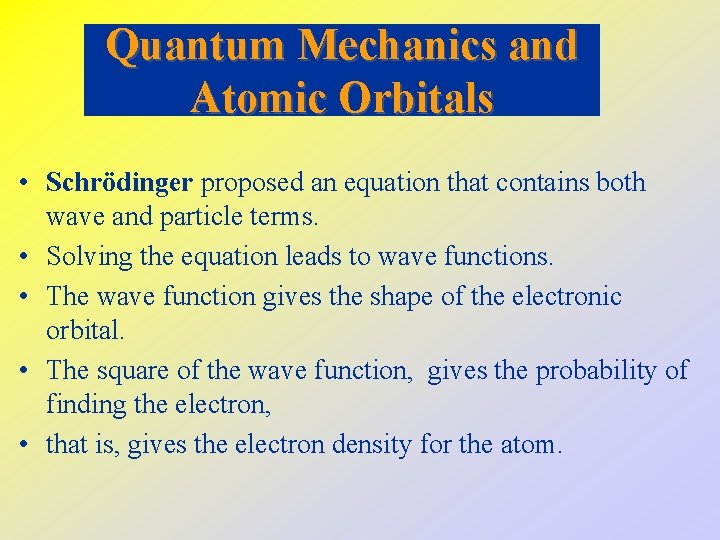

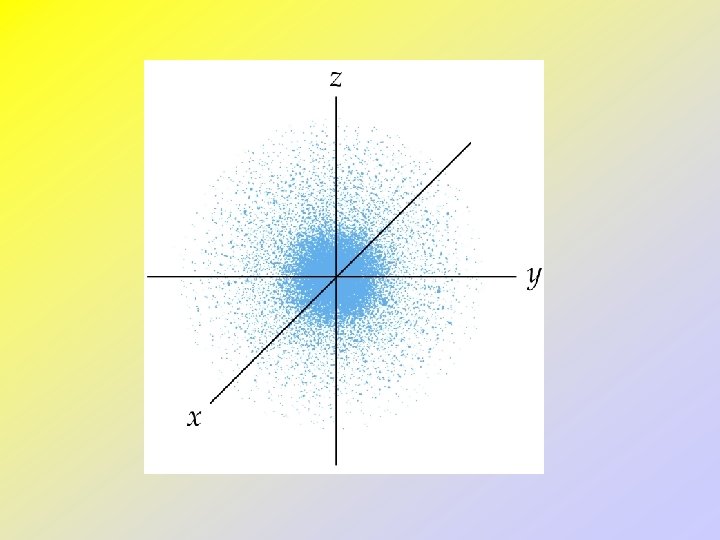

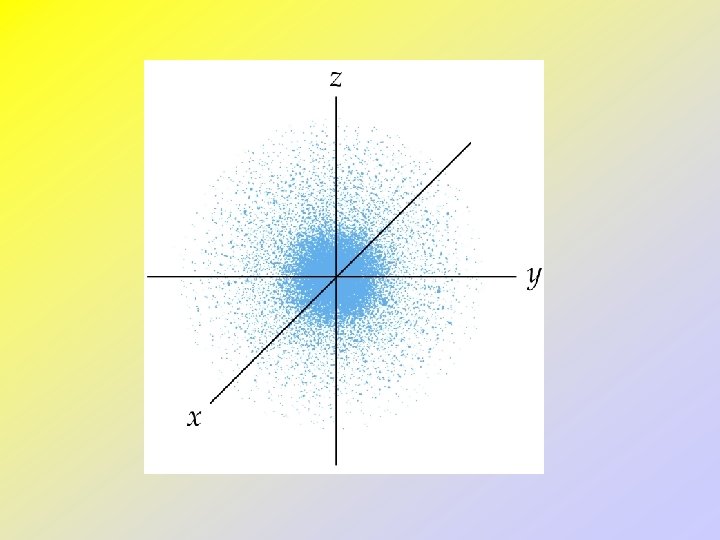

Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Orbitals • Schrödinger proposed an equation that contains both wave and particle terms. • Solving the equation leads to wave functions. • The wave function gives the shape of the electronic orbital. • The square of the wave function, gives the probability of finding the electron, • that is, gives the electron density for the atom.

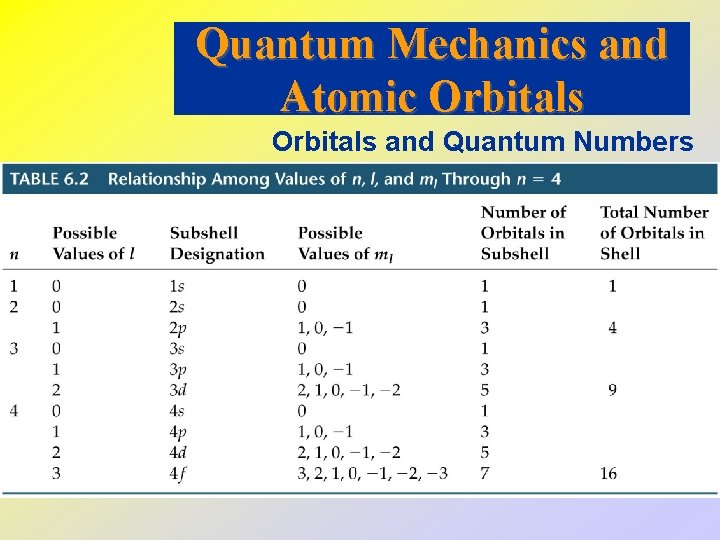

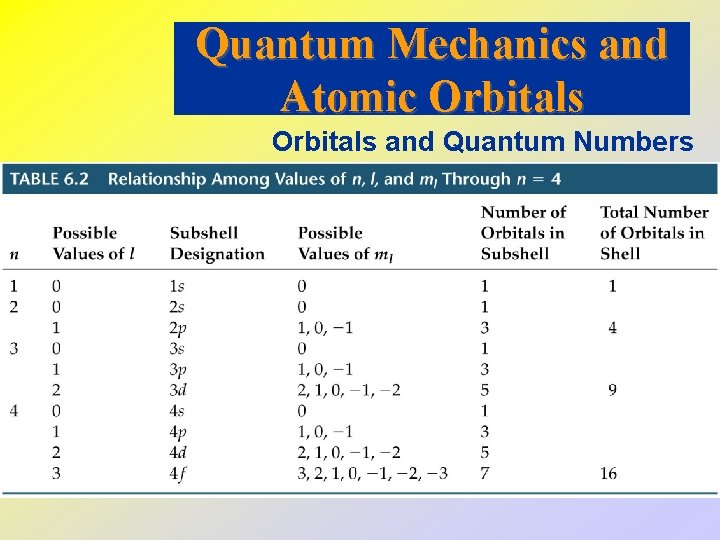

Orbitals and Quantum Numbers • If we solve the Schrödinger equation, we get wave functions and energies for the wave functions. • We call wave functions orbitals. • Schrödinger’s equation requires 3 quantum numbers: 1. Principal Quantum Number, n. This is the same as Bohr’s n. As n becomes larger, the atom becomes larger and the electron is further from the nucleus.

2. Azimuthal Quantum Number, l. This quantum number depends on the value of n. The values of l begin at 0 and increase to (n - 1). We usually use letters for l (s, p, d and f for l = 0, 1, 2, and 3). Usually we refer to the s, p, d and f-orbitals. 3. Magnetic Quantum Number, ml. This quantum number depends on l. The magnetic quantum number has integral values between -l and +l. Magnetic quantum numbers give the 3 D orientation of each orbital. 4. Spin Quantum Number, ms. This quantum number represents the “spin” or rotation of the electron. The possible values are +½ or -½.

Quantum Mechanics and Atomic Orbitals and Quantum Numbers

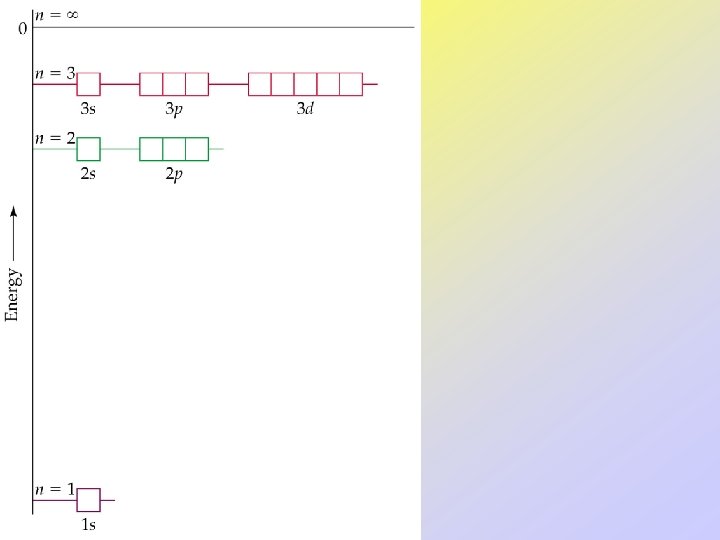

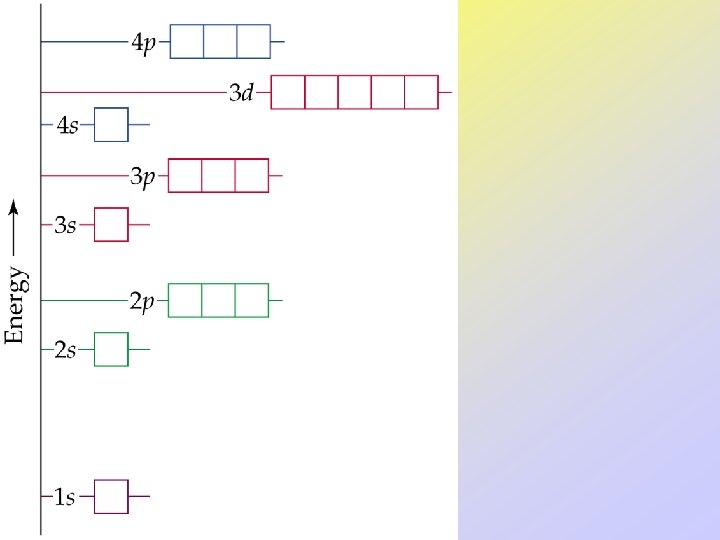

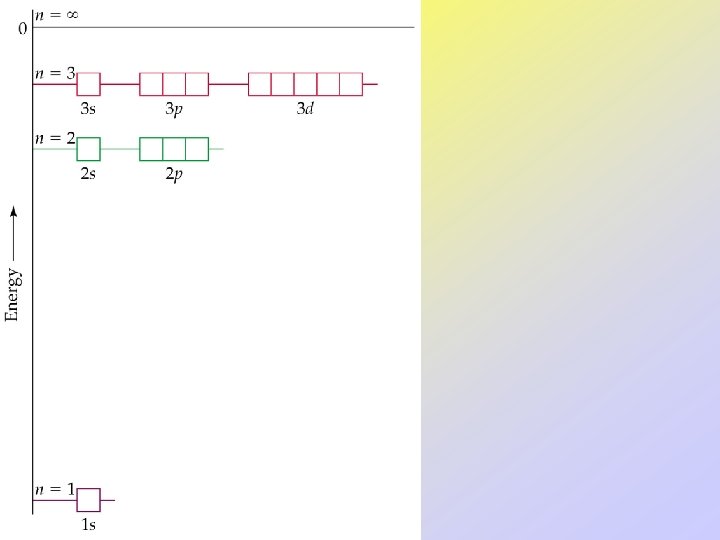

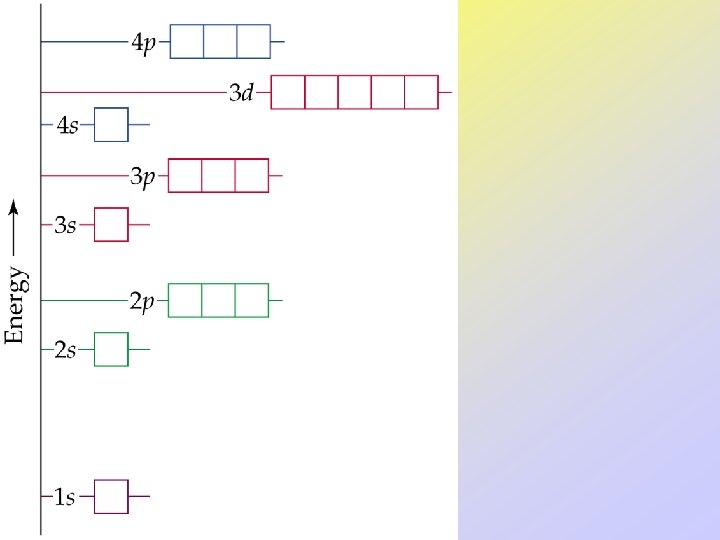

• Orbitals can be ranked in terms of energy to yield an Aufbau diagram. • Note that the following Aufbau diagram is for a single electron system. • As n increases, note that the spacing between energy levels becomes smaller.

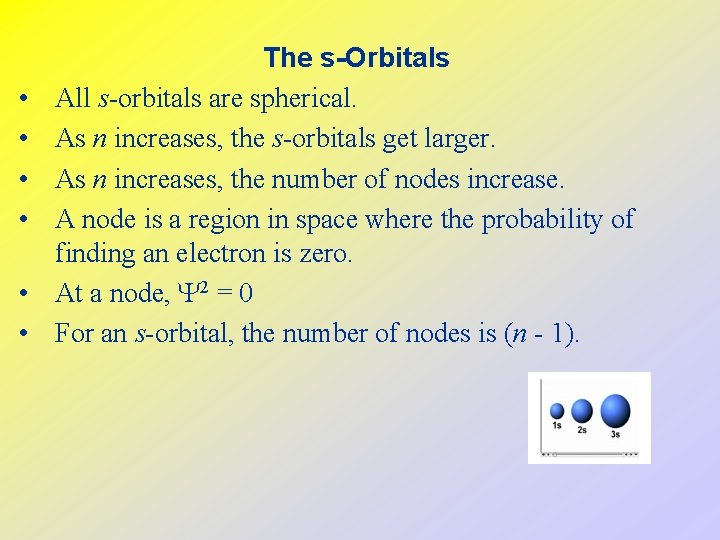

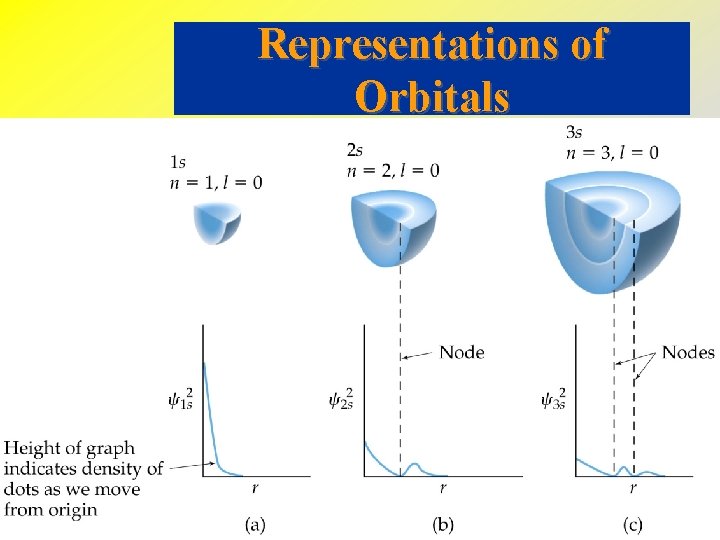

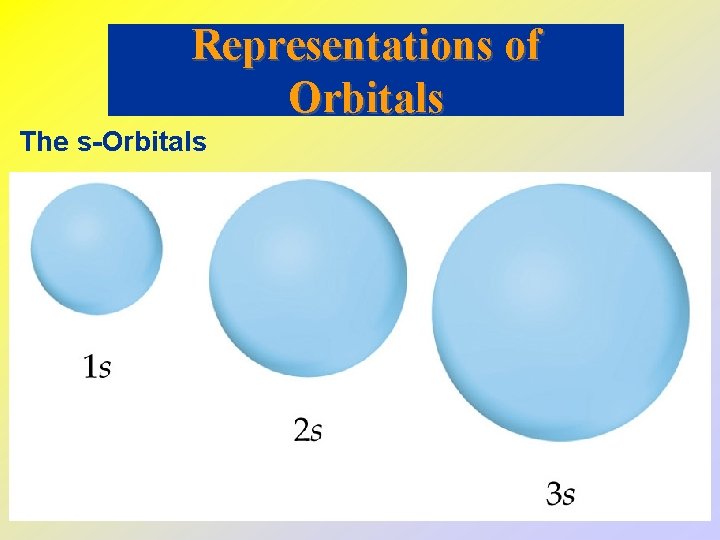

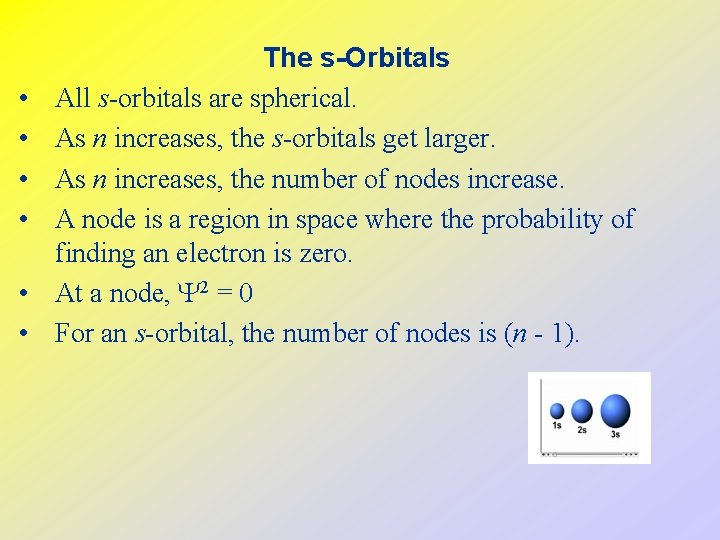

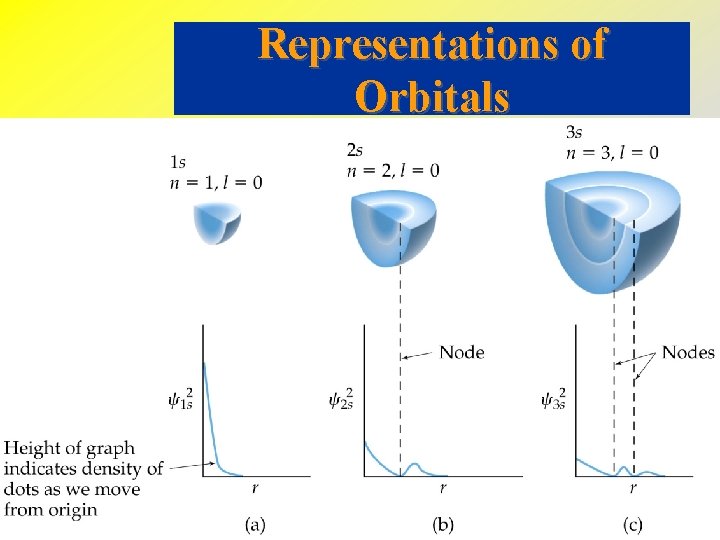

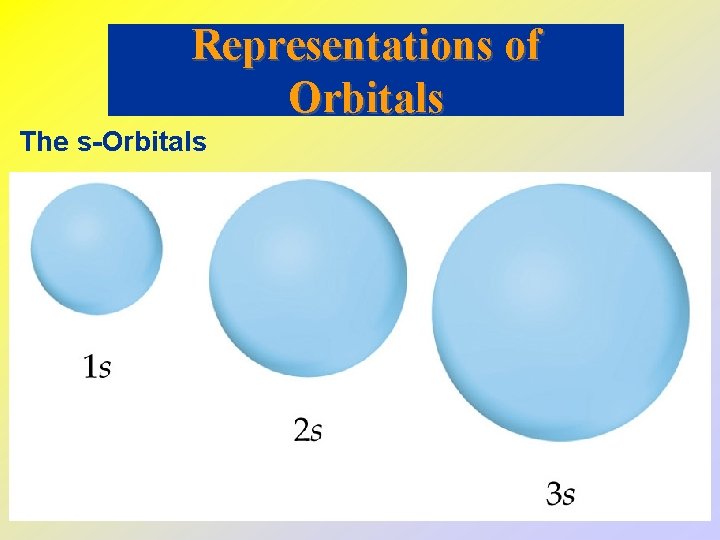

• • • The s-Orbitals All s-orbitals are spherical. As n increases, the s-orbitals get larger. As n increases, the number of nodes increase. A node is a region in space where the probability of finding an electron is zero. At a node, 2 = 0 For an s-orbital, the number of nodes is (n - 1).

Representations of Orbitals

Representations of Orbitals The s-Orbitals

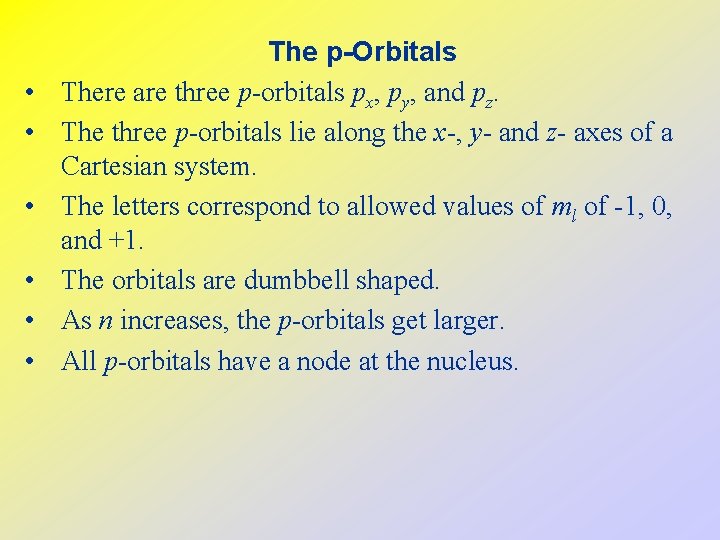

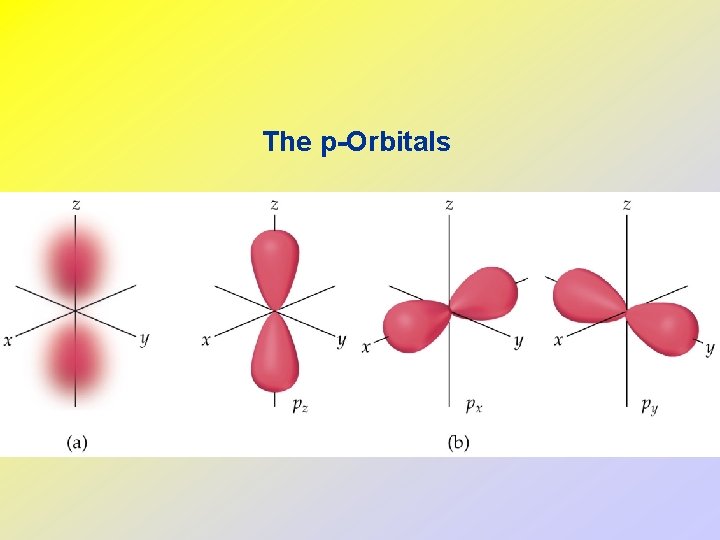

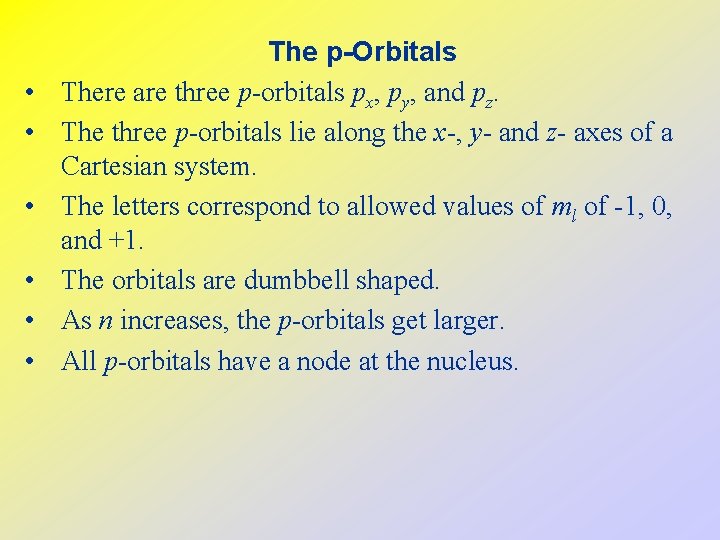

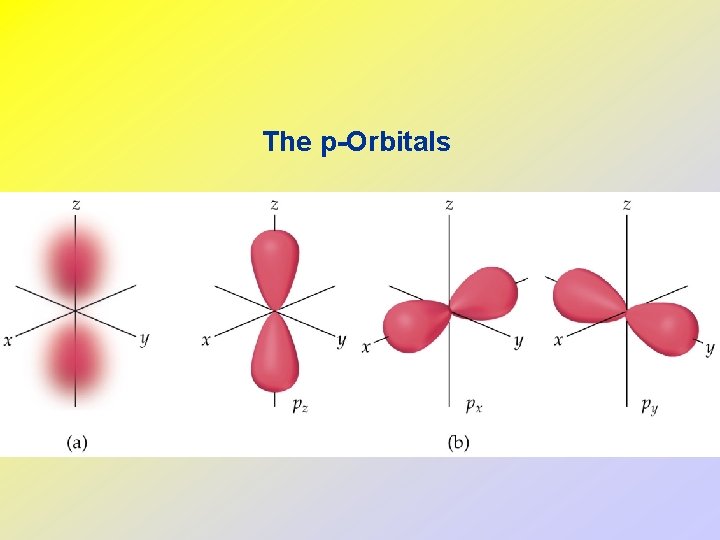

• • • The p-Orbitals There are three p-orbitals px, py, and pz. The three p-orbitals lie along the x-, y- and z- axes of a Cartesian system. The letters correspond to allowed values of ml of -1, 0, and +1. The orbitals are dumbbell shaped. As n increases, the p-orbitals get larger. All p-orbitals have a node at the nucleus.

The p-Orbitals

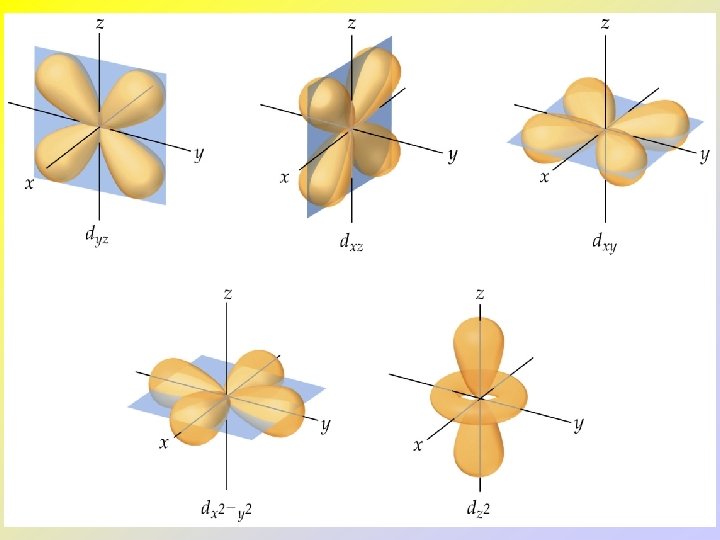

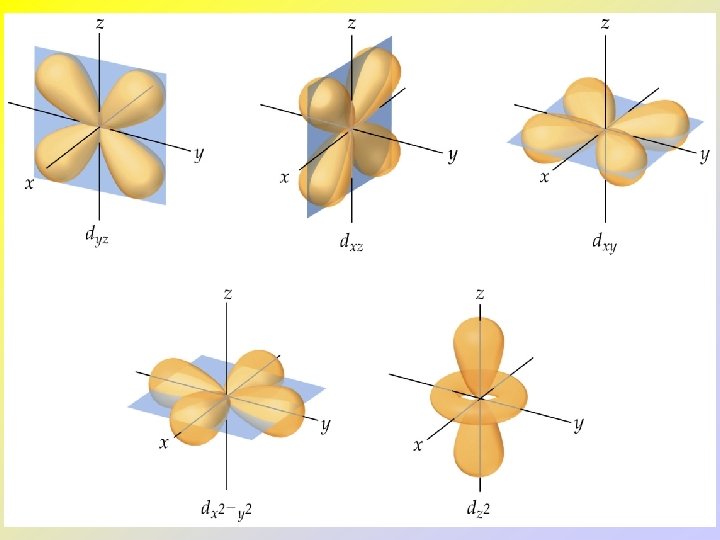

• • • The d and f-Orbitals There are five d and seven f-orbitals. Three of the d-orbitals lie in a plane bisecting the x-, yand z-axes. Two of the d-orbitals lie in a plane aligned along the x-, y- and z-axes. Four of the d-orbitals have four lobes each. One d-orbital has two lobes and a collar.

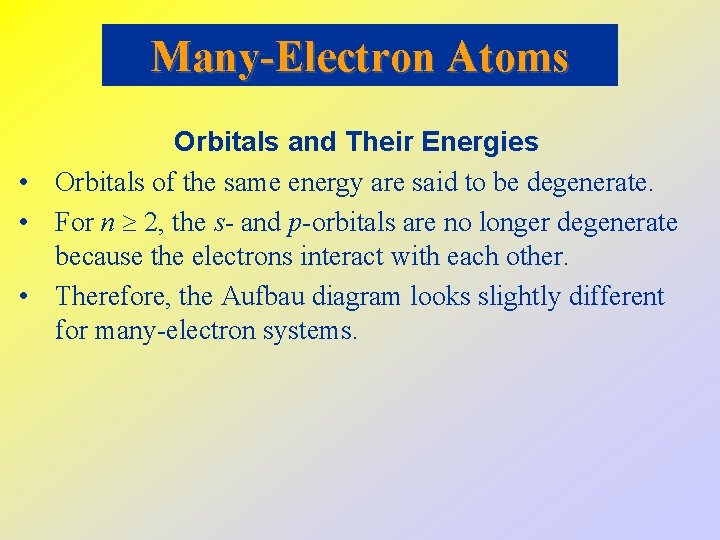

Many-Electron Atoms Orbitals and Their Energies • Orbitals of the same energy are said to be degenerate. • For n 2, the s- and p-orbitals are no longer degenerate because the electrons interact with each other. • Therefore, the Aufbau diagram looks slightly different for many-electron systems.

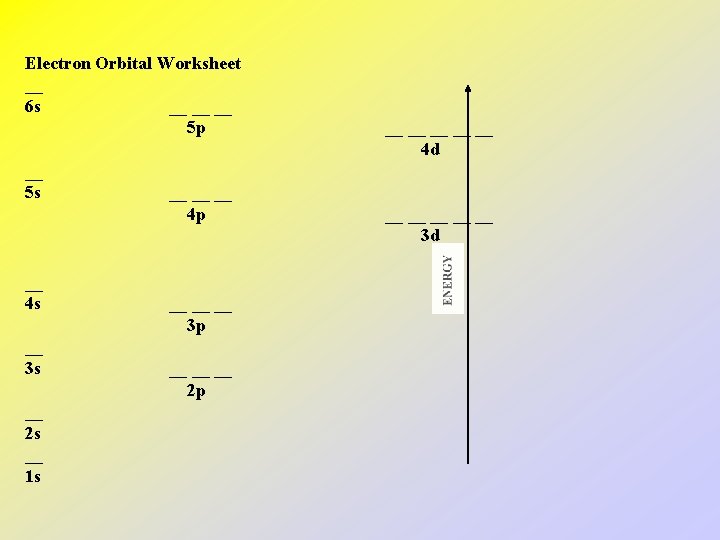

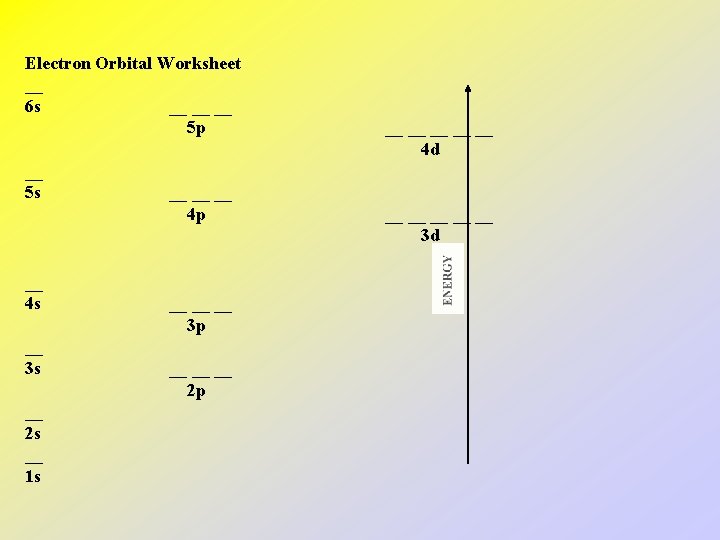

Electron Orbital Worksheet __ 6 s __ __ __ 5 p __ 5 s __ 4 s __ 3 s __ 2 s __ 1 s __ __ __ 4 p __ __ __ 3 p __ __ __ 2 p __ __ __ 4 d __ __ __ 3 d

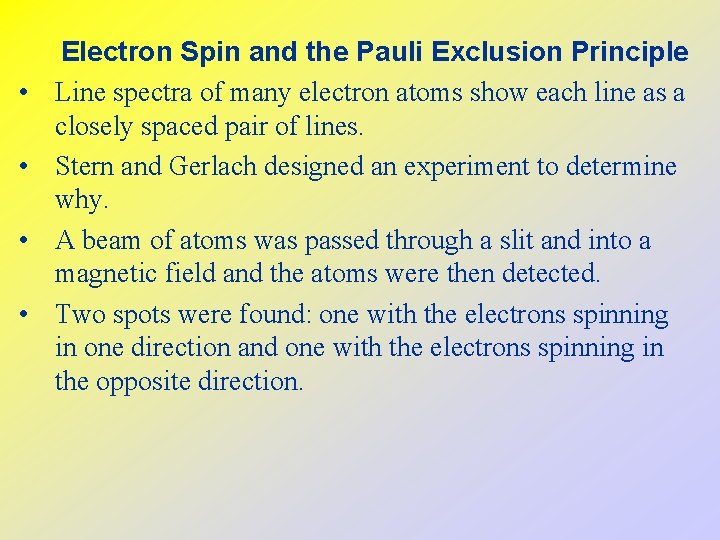

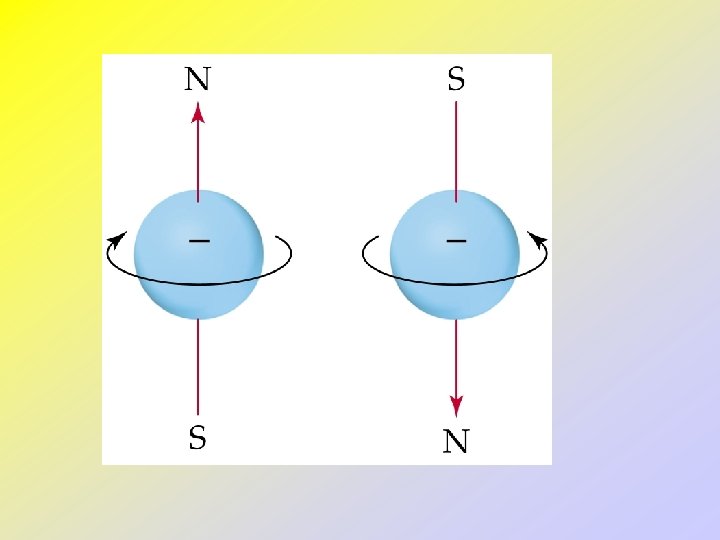

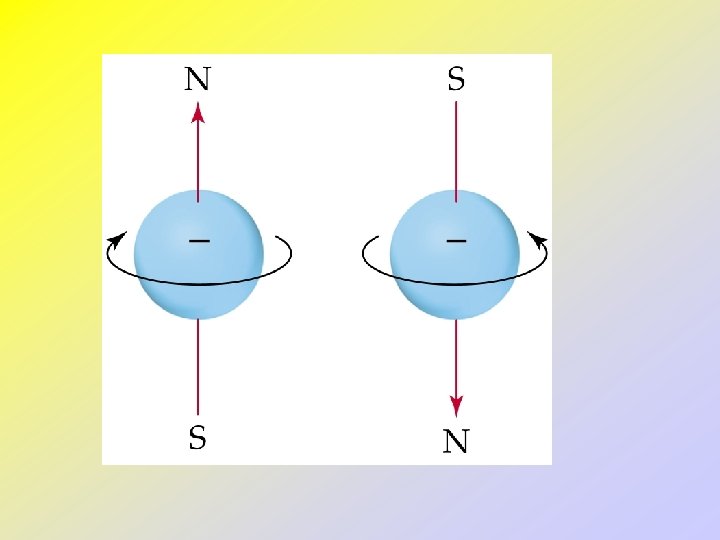

• • Electron Spin and the Pauli Exclusion Principle Line spectra of many electron atoms show each line as a closely spaced pair of lines. Stern and Gerlach designed an experiment to determine why. A beam of atoms was passed through a slit and into a magnetic field and the atoms were then detected. Two spots were found: one with the electrons spinning in one direction and one with the electrons spinning in the opposite direction.

• Since electron spin is quantized, we define ms = spin quantum number = ½. • Pauli’s Exclusion Principle: no two electrons can have the same set of 4 quantum numbers. • Therefore, two electrons in the same orbital must have opposite spins.

Hund’s Rule • Electron configurations tells us in which orbitals the electrons for an element are located. • Three rules: • • • electrons fill orbitals starting with lowest n and moving upwards; no two electrons can fill one orbital with the same spin (Pauli); for degenerate orbitals, electrons fill each orbital singly before any orbital gets a second electron (Hund’s rule).

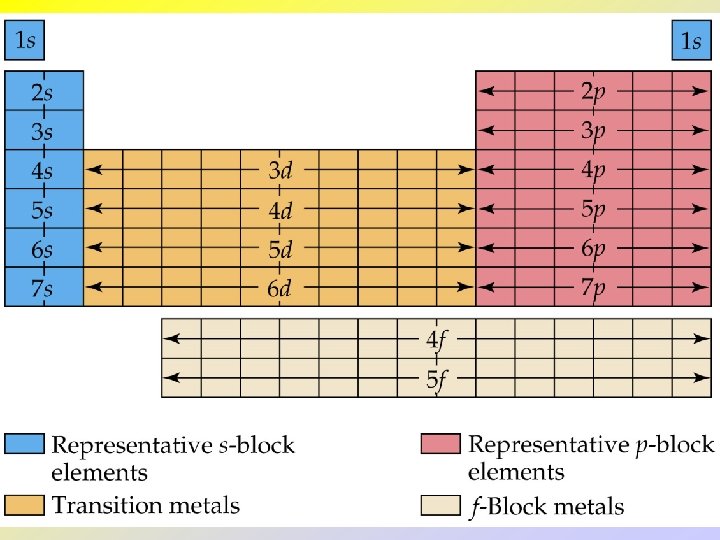

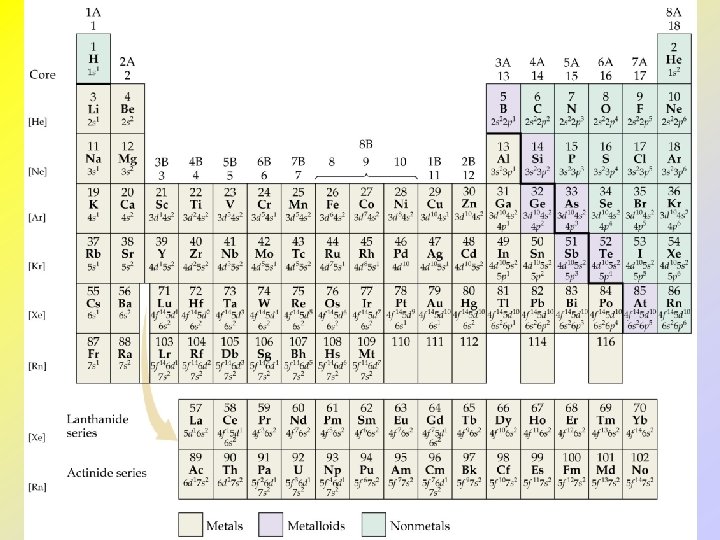

Electron Configurations Transition Metals • After Ar the d orbitals begin to fill. • After the 3 d orbitals are full, the 4 p orbitals being to fill. • Transition metals: elements in which the d electrons are the last electrons to fill.

Examples – Write electron configurations for the following: 1. Mg 2. N 3. Br 4. Cu 5. O

• • • Condensed Electron Configurations Neon completes the 2 p subshell. Sodium marks the beginning of a new row. So, we write the condensed electron configuration for sodium as Na: [Ne] 3 s 1 [Ne] represents the electron configuration of neon. Core electrons: electrons in [Noble Gas]. Valence electrons: electrons outside of [Noble Gas].

• • • Lanthanides and Actinides From Ce onwards the 4 f orbitals begin to fill. Note: La: [Xe]6 s 25 d 14 f 0 Elements Ce - Lu have the 4 f orbitals filled and are called lanthanides or rare earth elements. Elements Th - Lr have the 5 f orbitals filled and are called actinides. Most actinides are not found in nature.

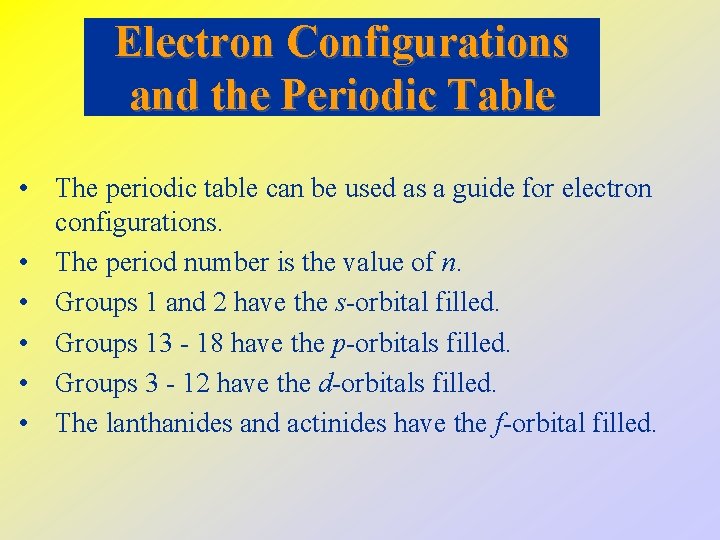

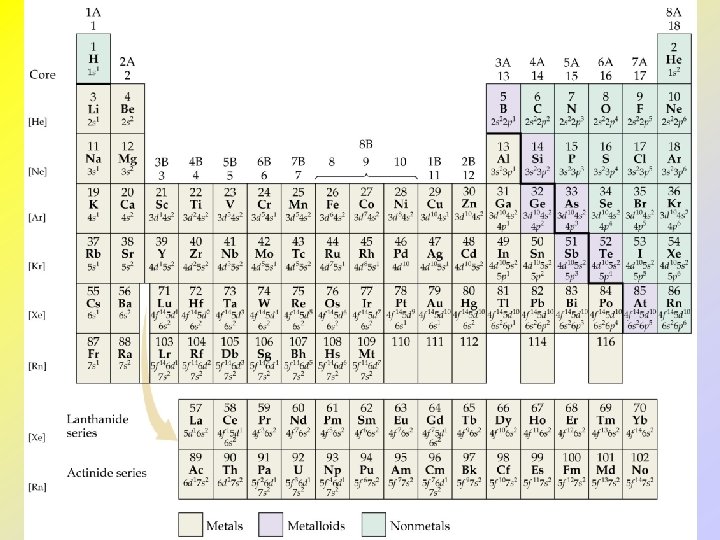

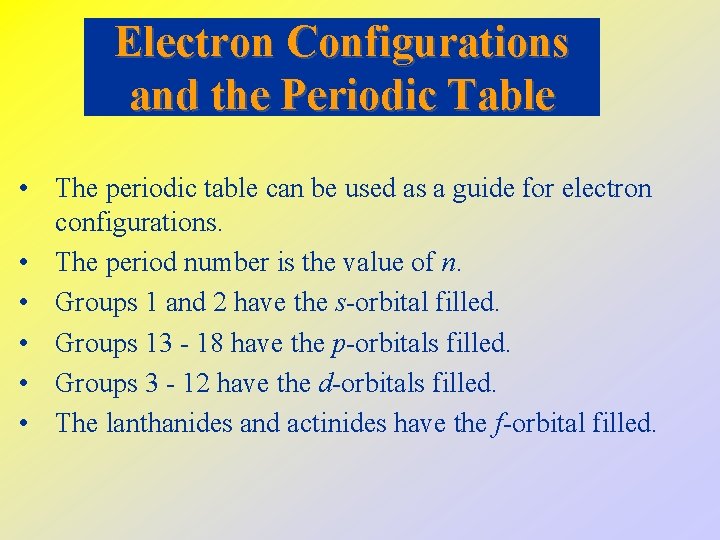

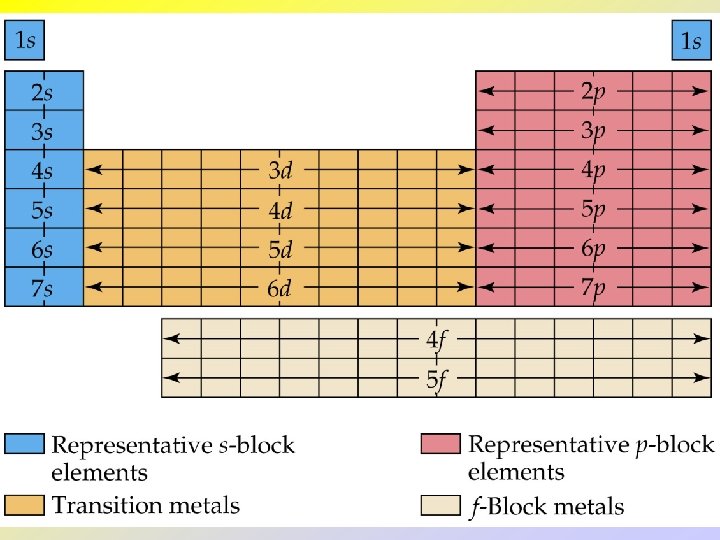

Electron Configurations and the Periodic Table • The periodic table can be used as a guide for electron configurations. • The period number is the value of n. • Groups 1 and 2 have the s-orbital filled. • Groups 13 - 18 have the p-orbitals filled. • Groups 3 - 12 have the d-orbitals filled. • The lanthanides and actinides have the f-orbital filled.

Examples – Write condensed electron configurations: 1. B 2. U 3. Tl 4. Es 5. W 6. Bi