AngloSaxon Literature How Dark were the Dark Ages

![407 AD - Pope Zosimus: Historia Nova The barbarians from beyond the Rhine [were] 407 AD - Pope Zosimus: Historia Nova The barbarians from beyond the Rhine [were]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a7db3f5a87d62c589fcedb3e9e759c1d/image-10.jpg)

- Slides: 38

Anglo-Saxon Literature How Dark were the ‘Dark Ages’? Dr Jon Mackley University of Northampton

In this session • Technicalities of terminology and dates • Unfamiliar characters of the fuþorc (alphabet) • Overview of the ‘Dark Ages’ – The Anglo Saxon Chronicle – The Beginning of ‘England’ (‘The Ruin’) • Old English Runes – A section from the Rune poem (Feoh) • Old English charters • The corpus of Anglo-Saxon literature – Riddles (69, 25) – Charms (‘A charm after livestock has been stolen’)

Some technicalities • Technically, Early English Literature refers to the ‘Early Middle Ages’ or the Anglo-Saxon Period (c. 595 -1000) • High Middle Ages (1066 -1307) • Late Middle Ages (1307 -1485) • However, for shorthand, ‘Saxon’ refers to EMA, ‘Medieval’ refers to High and Late Middle Ages

The dates are arbitrary • It takes time for a new ideology to spread across the country. • The High Middle Ages didn’t simply spring into existence on 14 October 1066, and the Late Middle Ages didn’t start on 7 July 1307 and didn’t end on 22 August 1485.

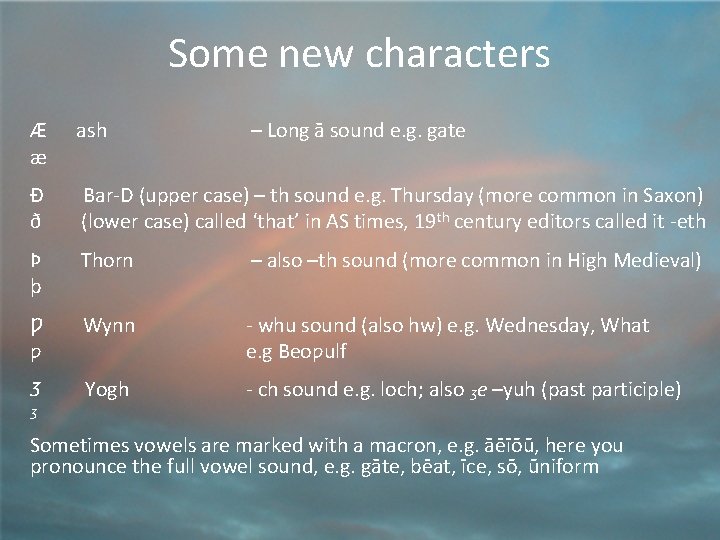

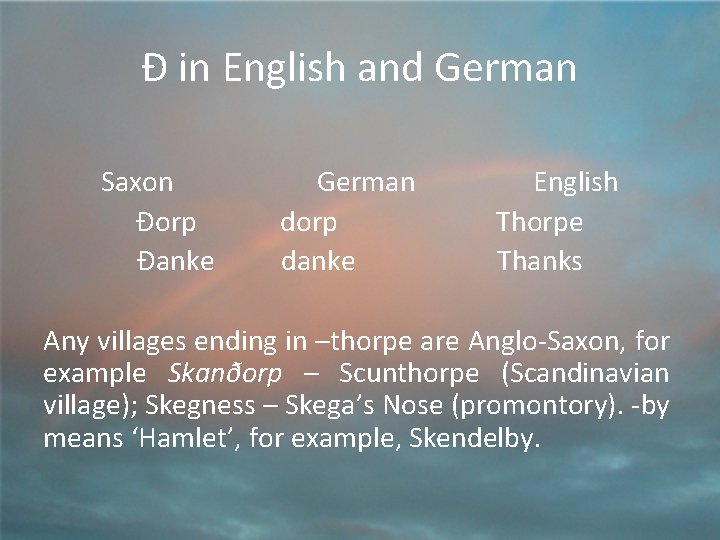

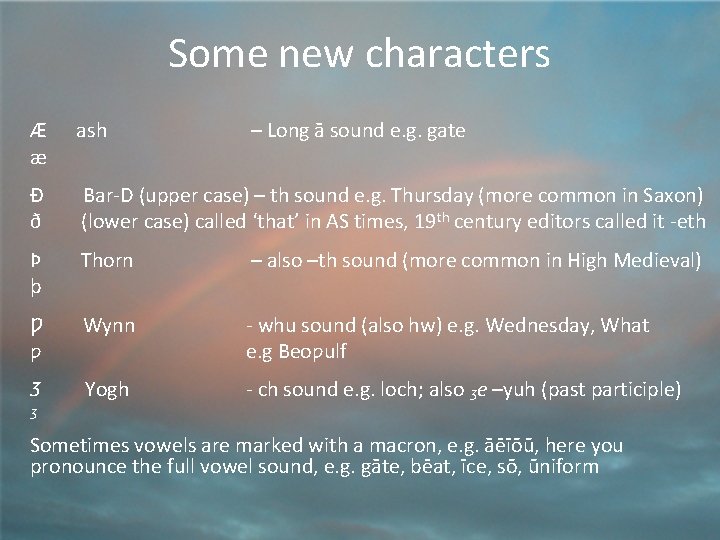

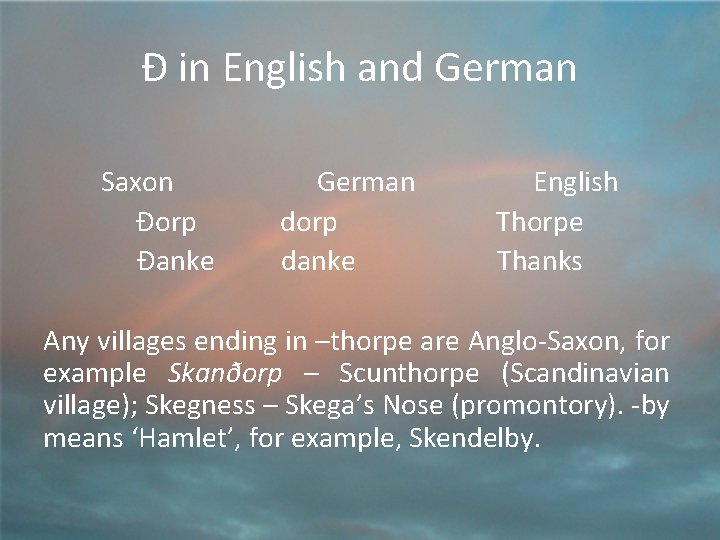

Some new characters Æ æ ash – Long ā sound e. g. gate Ð ð Bar-D (upper case) – th sound e. g. Thursday (more common in Saxon) (lower case) called ‘that’ in AS times, 19 th century editors called it -eth Þ þ Thorn – also –th sound (more common in High Medieval) Ƿ ƿ Wynn - whu sound (also hw) e. g. Wednesday, What e. g Beoƿulf Ȝ Yogh - ch sound e. g. loch; also ȝe –yuh (past participle) ȝ Sometimes vowels are marked with a macron, e. g. āēīōū, here you pronounce the full vowel sound, e. g. gāte, bēat, īce, sō, ūniform

Ð in English and German Saxon Ðorp Ðanke German dorp danke English Thorpe Thanks Any villages ending in –thorpe are Anglo-Saxon, for example Skanðorp – Scunthorpe (Scandinavian village); Skegness – Skega’s Nose (promontory). -by means ‘Hamlet’, for example, Skendelby.

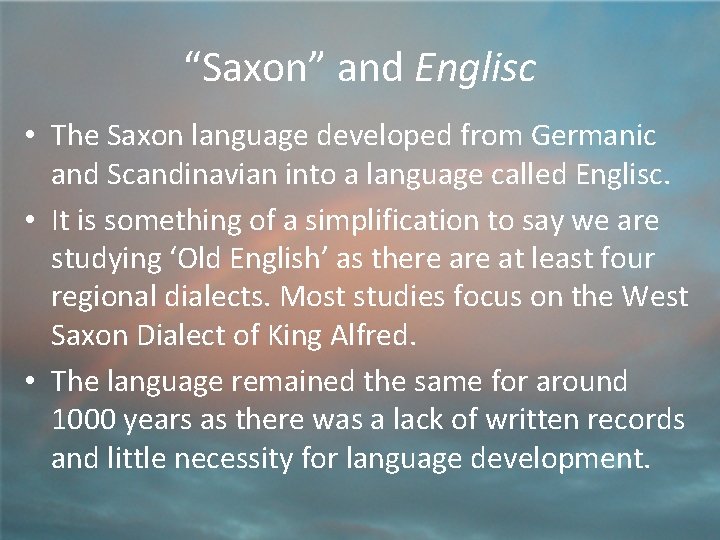

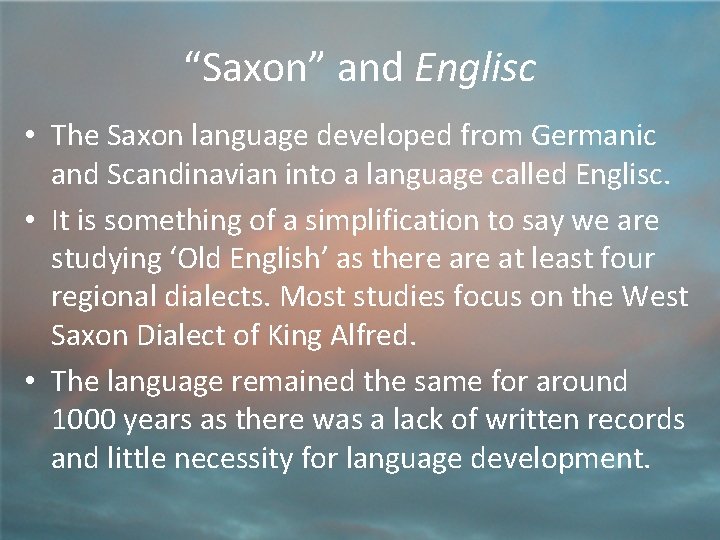

“Saxon” and Englisc • The Saxon language developed from Germanic and Scandinavian into a language called Englisc. • It is something of a simplification to say we are studying ‘Old English’ as there at least four regional dialects. Most studies focus on the West Saxon Dialect of King Alfred. • The language remained the same for around 1000 years as there was a lack of written records and little necessity for language development.

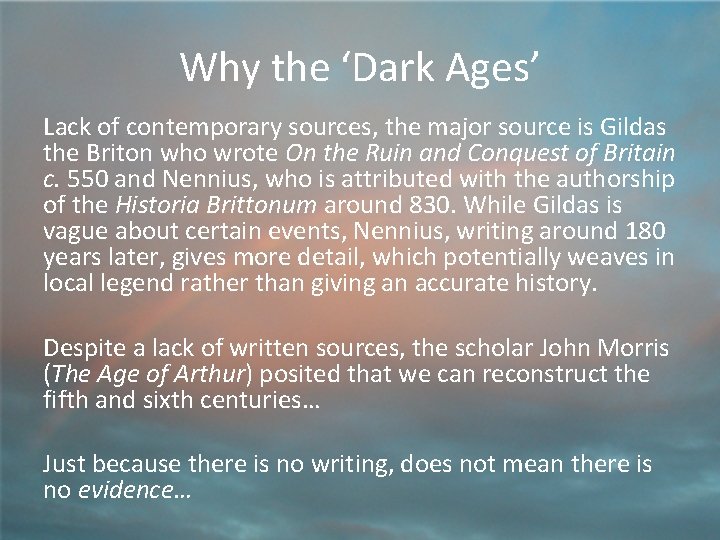

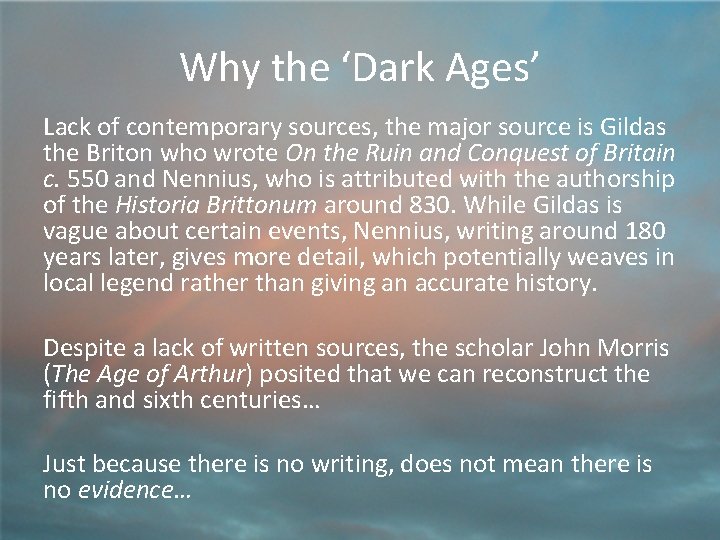

Why the ‘Dark Ages’ Lack of contemporary sources, the major source is Gildas the Briton who wrote On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain c. 550 and Nennius, who is attributed with the authorship of the Historia Brittonum around 830. While Gildas is vague about certain events, Nennius, writing around 180 years later, gives more detail, which potentially weaves in local legend rather than giving an accurate history. Despite a lack of written sources, the scholar John Morris (The Age of Arthur) posited that we can reconstruct the fifth and sixth centuries… Just because there is no writing, does not mean there is no evidence…

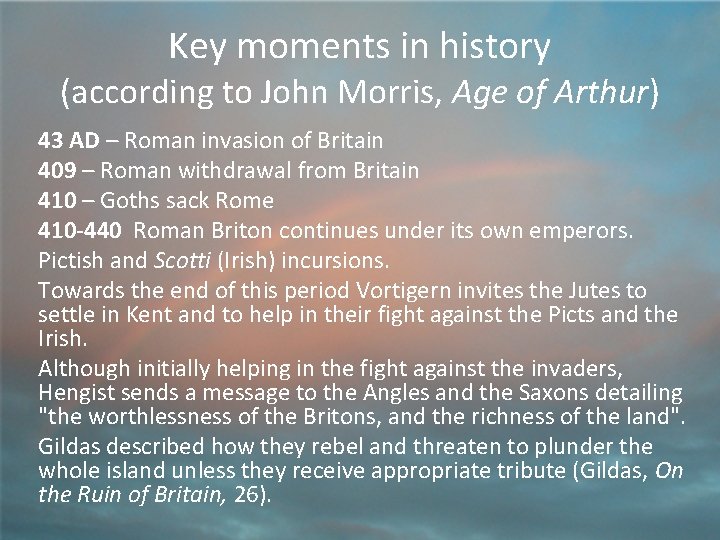

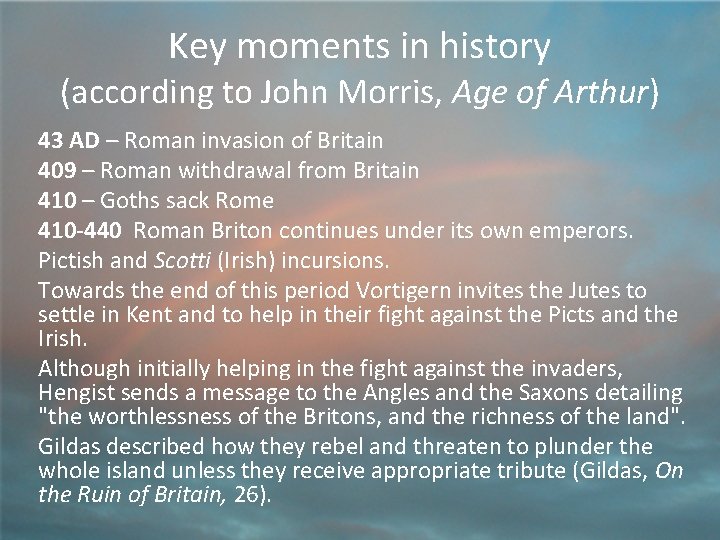

Key moments in history (according to John Morris, Age of Arthur) 43 AD – Roman invasion of Britain 409 – Roman withdrawal from Britain 410 – Goths sack Rome 410 -440 Roman Briton continues under its own emperors. Pictish and Scotti (Irish) incursions. Towards the end of this period Vortigern invites the Jutes to settle in Kent and to help in their fight against the Picts and the Irish. Although initially helping in the fight against the invaders, Hengist sends a message to the Angles and the Saxons detailing "the worthlessness of the Britons, and the richness of the land". Gildas described how they rebel and threaten to plunder the whole island unless they receive appropriate tribute (Gildas, On the Ruin of Britain, 26).

![407 AD Pope Zosimus Historia Nova The barbarians from beyond the Rhine were 407 AD - Pope Zosimus: Historia Nova The barbarians from beyond the Rhine [were]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a7db3f5a87d62c589fcedb3e9e759c1d/image-10.jpg)

407 AD - Pope Zosimus: Historia Nova The barbarians from beyond the Rhine [were] ravaging everything at their pleasure, [and] put both the Britons and some of the Gauls to the necessity of making defection from the Roman Empire, and of setting up for themselves, no longer obeying Roman laws. The Britons therefore took up arms, and engaged in many dangerous enterprises for their own protection, until they had freed their cities from the barbarians who besieged them.

The Romans leave Britain • There was a gradual withdrawal from Britain: in 408 AD the Visigoths laid siege to Rome and Roman forces were needed to deal with this situation. The western Roman emperor Honorius had written to the Romano-Britons telling them that they had to look to their own defence and military withdrawal was completed around 409, with Rome leaving general to act as Governors for the country. • In 410, the Goths sacked Rome and it became clear that Rome was not coming back to defend its province. At the same time there were sustained raid on Britain by gangs of Picts, the Scotti (Irish) and Saxon invaders. Yet, for thirty years (410 -440, the first of Morris’s periods) Roman Britain continued under its own emperors. However, it is believed that, towards the end of this period that the leading warlord among the Britons, Vortigern, invited the Saxons to settle in Kent to help their fight against the Picts and the Irish. This is seen as the beginning of a long period of British Saxon Wars (John Morris’s second reconstructed period).

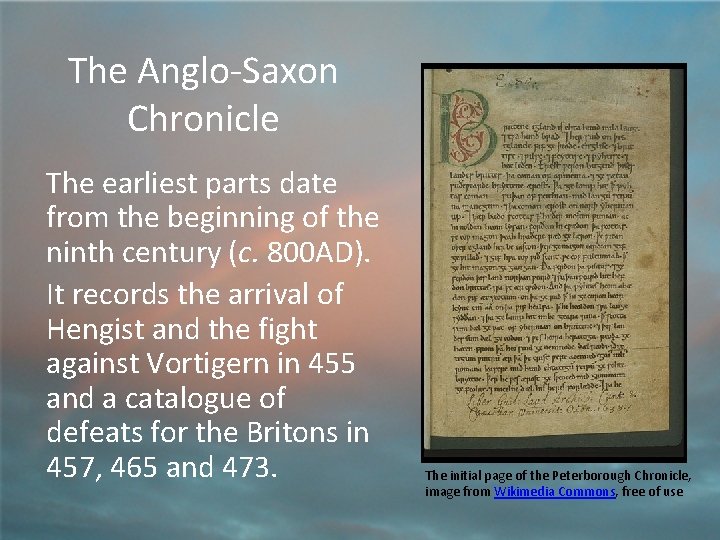

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle The earliest parts date from the beginning of the ninth century (c. 800 AD). It records the arrival of Hengist and the fight against Vortigern in 455 and a catalogue of defeats for the Britons in 457, 465 and 473. The initial page of the Peterborough Chronicle, image from Wikimedia Commons, free of use

Anglo Saxon Chronicle 455 Her Hengest 7 Horsa fuhton wiþ Wyrtgeorne þam cyninge, in þaere stowe þe is gecueden Agælesþrep, 7 his broþer Horsan man ofslog. 7 æfter þam Hengest feng [to] rice 7 Æsc his sunu. In this year Hengest and Horsa fought against King Vortigern at a place which is called Agælesþrep [Aylesford], and his brother Horsa was slain. And after that Hengest succeeded to the kingdom and Æsc, his son.

Invaders • The Jutes went to Kent, the Isle of Wight and Hampshire • The Angles went to Anglia (north folk and south folk) and Northumbria • The Saxons went to Sussex, Essex, Wessex and Middlesex. • The Saxons called the Celts who went to the West wealas (foreigners). • Those who went to the south west, to the horn (cornu-) of England, were called cornu-wealas. Click here to see a map of Britain in 597.

The beginnings of “England” The Angles came from the Schleswig-Holstein area of Germany, called northern Angeln, just beneath the Jutish peninsula. Tacitus, writing in the Germania at the end of the first century, refers to the Angli as “goddess-worshippers; they looked on the earth as their mother. ” From the sixth century, people from our nation had been called Angles: Gregory the Great described boys in a slave market as non angli, sed angeli. Although the language of Old English texts is called Englisc, references to Englaland do not appear until c. 1000. Click here to see a map of the beginnings of England.

After the Romans left, the Settlers used the stone from Roman buildings for their own structures Click here to view the remains of the Roman city of Canterbury by the sixth century.

The Ruin Beorht wæron burgræced, burnsele monige, heah horngestreon, heresweg micel, meodoheall monig mondreama full, oþþæt onwende wyrd seo swiþe. Crungon walo wide, cwoman woldagas, swylt eall fornom secgrofra wera; wurdon hyra wigsteal westen staþolas, brosnade burgsteall. Betend crungon hergas to hrusan. Bright were the castle buildings, many the bathing-halls, high the abundance of gables, great the noise of the multitude, many a meadhall full of festivity, until Fate the mighty changed that. Far and wide the slain perished, days of pestilence came, death took all the brave men away; their places of war became deserted places, the city decayed. The rebuilders perished, the armies to earth.

The first Saxon revolt of 440 -457 There followed a series of battles, including a semi-apocryphal story that is included in the Historia Britoniaum of Nennius, where the Saxons and the Britons met at Salisbury Plain for a negotiation of peace: whereupon the Saxons slaughtered the unarmed Britons and held Vortigern hostage until he conceded the kingdoms which would be known as Est Saxum, Sut saxum and Middelseaxan. This first Saxon was successful in subjugating Britain, was, according to the Gallic chronicler, around 441.

Gildas: 442 AD All the great towns fell to the Saxon battering rams. Bishops, priests and people were all chopped down together while swords flashed and flames crackled. It was horrible to see the stones of towers thrown down to mix with pieces of human bodies. Broken altars were covered with a purple crust of clotted blood. There was no burial except under ruins and bodies were eaten by the birds and beasts.

The brutality of the Saxons knew no limits: Gildas describes how ‘A fire heaped up and nurtured by the hand of impious easterners spread from sea to sea. It devastated town and country round about, and, once it was alight, it did not die down until it had burned almost the whole surface of the island was licking the western ocean with its fierce red tongue’ Gildas, On the Ruin of Britain, 27

Hengest’s betrayal Around 456 Hengest sued for peace. Vortigern, married to Hengest’s daughter agreed to bring his top warriors and clergymen to discuss terms; however, he insisted that no one brought any weapons. Except his own people… most of Vortigern’s principal advisors were slaughtered.

British Resistance From 460 -495/500 there were also a series of successful campaigns of British resistance. This culminated the Battle of Mount Badon Hill which, as Gildas describes was ‘the last great slaughter’ of the Saxon invaders by the Britons. Nennius, writing in the ninth century, places Arthur at Badon Hill, although he is described as dux bellorum (war leader), rather than king.

Plague and Revolt In the 570 s, a plague is said to have broken out and weakened the Britons, which led to a second Saxon revolt, which led to the Saxons overrunning much of the south of England. The events described here are contemporary with Gildas.

The Coming of Outline of ‘Dark Age’ Britain Christianity 595 Gregory Great 409 Pope Romans leave the Britain initiated mission 410 Sackaof Rome to bring Christianity to England. 410 -440 Britain ruled by Roman Governors Initially we see a co-existence c. 440 British Warlord Vortigernof invites Saxons Hengist and Saxon Christian cultures; Horsaand to settle in Kent to assist in fight against the Picts however, Christianity 440 -457 Saxon Revolt. becomes “Britain burns from coast to coast”. the dominant force and attempts Britain subjugated to suppress Saxon custom and 460 -495 Britons revolt against Saxons tradition. c. 495 Battle of Mons Badon – Saxons routed More writings survive, although 500 -560 Briton rule the best accounts of the 570 Plaguemission weakens Britons; Gregorian arethe found in Saxons invade and conquer 597 writing Beginning of Augustine’s the of Bede, writing atmission, bringing Christianity to Kent the start of the eighth century.

The where Comingwe ofmight find examples Places Christianity of language 595 Pope Gregory the Great Runes: a. Found initiated missionon toswords, bring carved into monuments and on intricate boxes (e. g. the Ruthwell Cross and Christianity to England. the Franks Initially we see. Casket) a co-existence of Saxon and Christian cultures; Saxon: Charters, would describe the however, Christianitywhich becomes boundaries owned a particular person or the dominant force andby attempts toestablishment suppress Saxon custom and tradition. Anglo-Saxon manuscripts: More writings survive, although. Four major manuscripts which the best contain accountspoems, of the elegies, maxims and Riddles Gregorian mission are found in the writing spoken of Bede, aloud writingtoatheal the sick, ward off evil Charms: the of theaeighth orstart discover thief century.

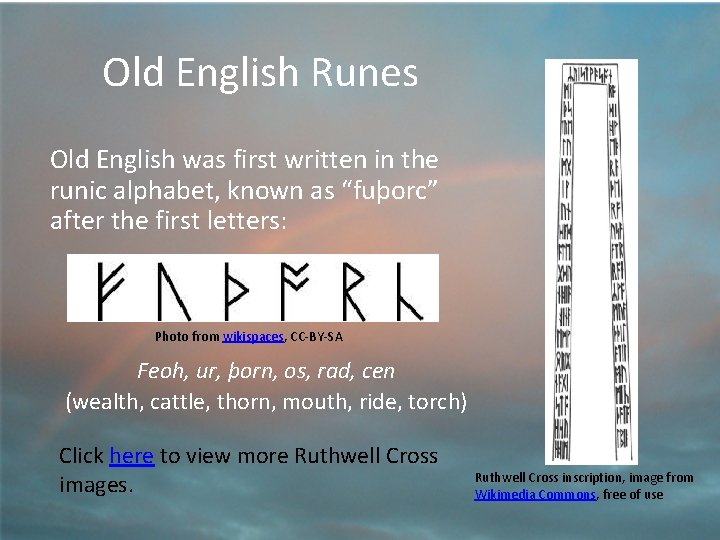

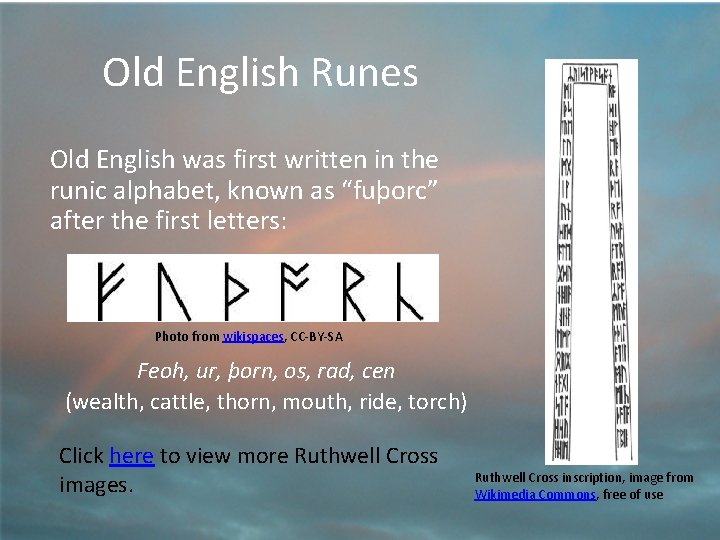

Old English Runes Old English was first written in the runic alphabet, known as “fuþorc” after the first letters: Photo from wikispaces, CC-BY-SA Feoh, ur, þorn, os, rad, cen (wealth, cattle, thorn, mouth, ride, torch) Click here to view more Ruthwell Cross images. Ruthwell Cross inscription, image from Wikimedia Commons, free of use

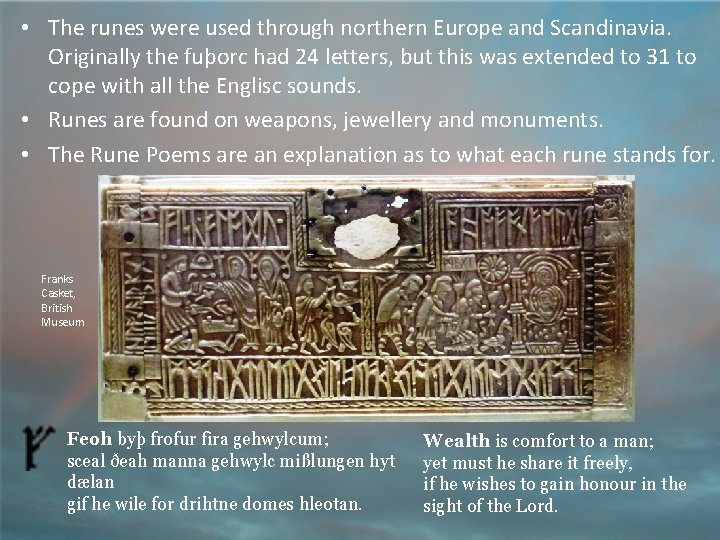

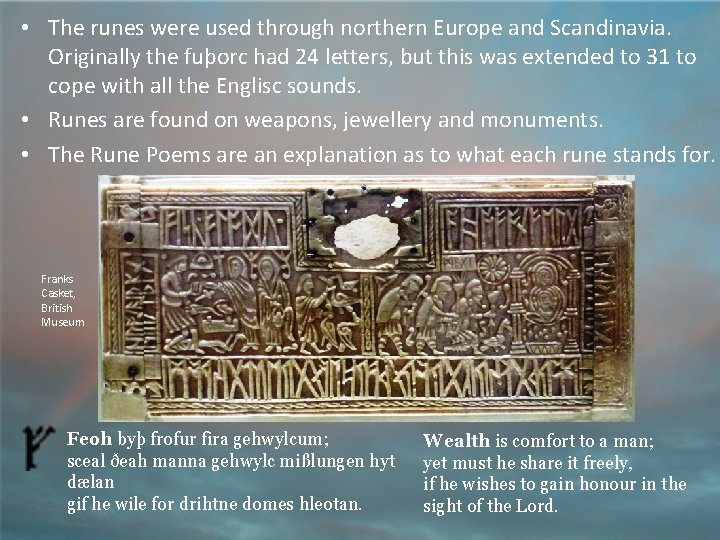

• The runes were used through northern Europe and Scandinavia. Originally the fuþorc had 24 letters, but this was extended to 31 to cope with all the Englisc sounds. • Runes are found on weapons, jewellery and monuments. • The Rune Poems are an explanation as to what each rune stands for. Franks Casket, British Museum Feoh byþ frofur fira gehwylcum; sceal ðeah manna gehwylc mißlungen hyt dælan gif he wile for drihtne domes hleotan. Wealth is comfort to a man; yet must he share it freely, if he wishes to gain honour in the sight of the Lord.

Charter S 367 A. D. 903. King Edward, with Æthelred and Æthelflæd of Mercia, at the request of Æthelfrith, dux, renews the charter of a grant by Athulf to Æthelgyth, his daughter, of 30 hides (cassati) at Monks Risborough, Bucks. Latin with English bounds. Regnante Aðulf dedit eastren Risberge. Eðelgiðe filie sue. . latine. + Ðis synt þa land gemæro. Ærest of þam garan innan þa blacan hegcean. of þære hegcean nyþer innan þone fulan broc of ðam fulan broce wiþ westan randes æsc þanon on þæne ealdan dic wið westan þa herde wic. of þære dic þæt innan wealdan hrigc on eadrices gemære. 7 lang eadrices gemære þæt innan cynebellinga gemære 7 lang gemære þæt on icenhylte. 7 lang icenhylte oþ þone hæðenan byrgels. þanon on cynges stræt. up 7 lang stræte on welandes stocc. of þam stocce nyþer 7 lang rah heges ðæt on heg leage of ðære leage nyþer ðæt eft on ðæne garan. + Eadweard rex. + Eaðelred. + Æðelflæd.

Bounds of Monks Risborough. First from the gore into the black hedge. From the hedge down into the foul brook. From the foul brook to the west of randes ash-tree. Then to the old ditch [or ‘dyke’] to the west of the dwellings for the herdsman. From the ditch then onto Waldridge to Eadric’s boundary. Along Eadric’s boundary then on to the Kimble people’s boundary. Along the boundary to the Icknield Way, along the Icknield way to the heathen burial. From there onto king’s street, up along the street to Weyland’s stump. From the stump down along roe-deer hedge. Then to hay clearing, from the clearing downwards, then back to the gore.

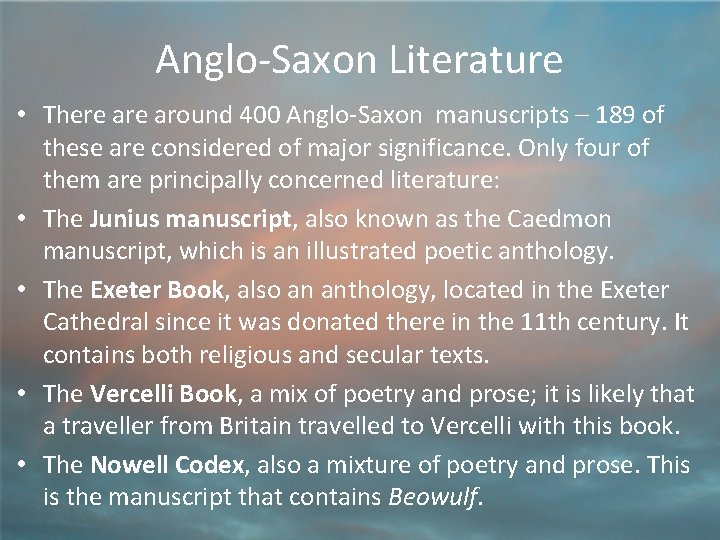

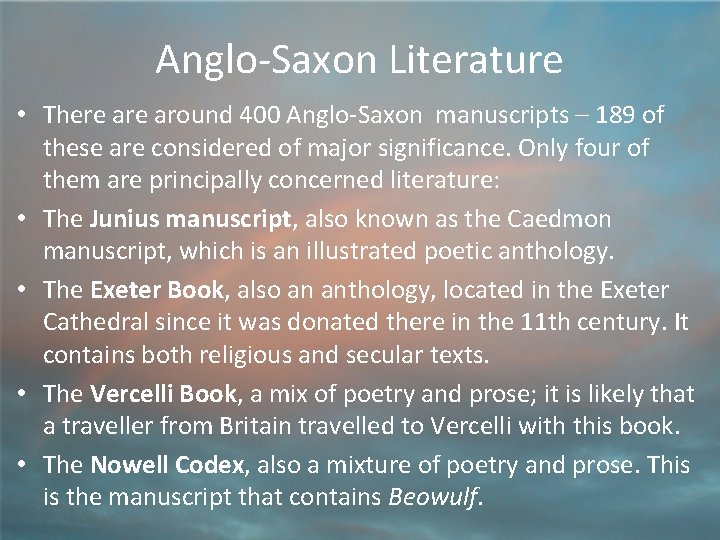

Anglo-Saxon Literature • There around 400 Anglo-Saxon manuscripts – 189 of these are considered of major significance. Only four of them are principally concerned literature: • The Junius manuscript, also known as the Caedmon manuscript, which is an illustrated poetic anthology. • The Exeter Book, also an anthology, located in the Exeter Cathedral since it was donated there in the 11 th century. It contains both religious and secular texts. • The Vercelli Book, a mix of poetry and prose; it is likely that a traveller from Britain travelled to Vercelli with this book. • The Nowell Codex, also a mixture of poetry and prose. This is the manuscript that contains Beowulf.

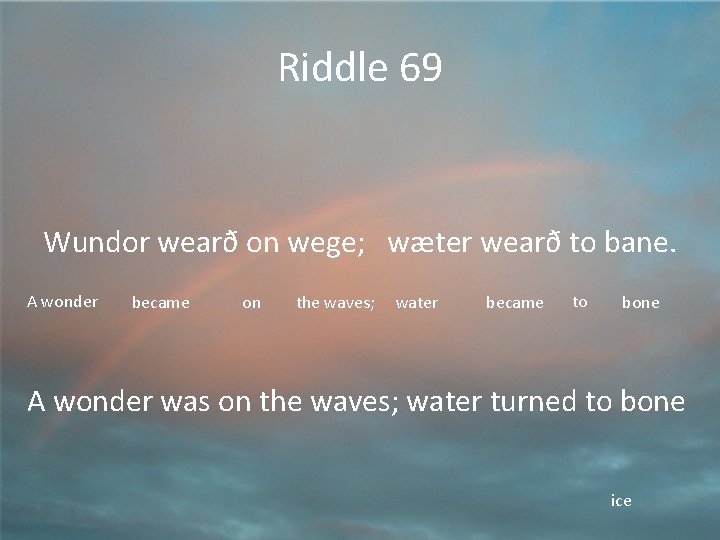

Riddles in the Dark (Ages) Much of Anglo-Saxon day to day culture was about survival, but we get glimpses of other parts of their lives. The Exeter Book (Codex Exoniensis), the largest corpus of Anglo-Saxon literature. Amongst others types of literature, this gives us over 90 riddles (but no answers). Some of these are concerned with serious matters like depression, war and death; there are Biblical stories (one concerning Lot and his incestuous daughters); descriptions of weapons; and double entendres.

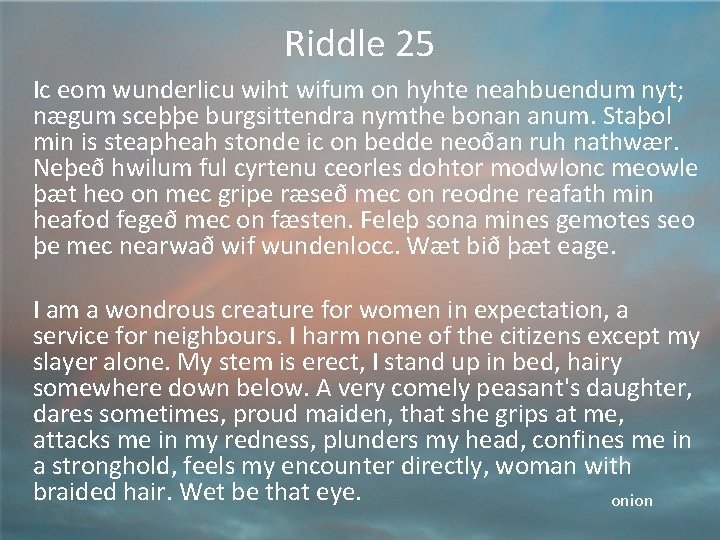

Riddle 69 Wundor wearð on wege; wæter wearð to bane. A wonder became on the waves; water became to bone A wonder was on the waves; water turned to bone ice

Riddle 25 Ic eom wunderlicu wiht wifum on hyhte neahbuendum nyt; nægum sceþþe burgsittendra nymthe bonan anum. Staþol min is steapheah stonde ic on bedde neoðan ruh nathwær. Neþeð hwilum ful cyrtenu ceorles dohtor modwlonc meowle þæt heo on mec gripe ræseð mec on reodne reafath min heafod fegeð mec on fæsten. Feleþ sona mines gemotes seo þe mec nearwað wif wundenlocc. Wæt bið þæt eage. I am a wondrous creature for women in expectation, a service for neighbours. I harm none of the citizens except my slayer alone. My stem is erect, I stand up in bed, hairy somewhere down below. A very comely peasant's daughter, dares sometimes, proud maiden, that she grips at me, attacks me in my redness, plunders my head, confines me in a stronghold, feels my encounter directly, woman with braided hair. Wet be that eye. onion

Charms cover such elements as medical concerns, such as eye pain, toothache, cysts, insomnia [against the dwarf that brings insomnia], treatment of poison an infection [the nine herbs charm], stabbing pain (possibly rheumatism [Wið færstice]) and childbirth. There also charms for troubles and concerns such as bees swarming, theft of property or for healthy crops [Æcerbot], or before going on a journey. The assumption underlying charms is that the incantations (whether words or symbols or phonetic patterns) of a charm can effect a change in the state of the person or persons or inanimate object (a salve, for example, or a field for crops). From a broader perspective, charms can be viewed as ritual acts because they incorporate conventional beliefs and actions of the society as well as the words of the incantation. It is the ritual aspect of charms that manifests the cosmological beliefs and the traditional practices of the society. Rebecca Fisher, Writing Charms: The Transmission and Performance of Charms in Anglo-Saxon England. Ph. D Diss. University of Sheffield

Performing a charm The charm is an oral performance to accomplish a purpose by means of performative speech in a ritual context. These are typically represented in the formal structure of the written texts, which consists of the following parts: (a) A heading naming the purpose of the charm: in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, the heading is often in the form “against something” (e. g. , Wið færstic, or “Against a Sudden Stitch”), although a charm may begin with a statement such as “A man should say this when someone tells him his cattle have been stolen. ” (b) Directions for performance (“say, ” “sing three times, ” “first take barley bread and write”). The directions for the acts associated with a verbal formula may constitute the longest part of the charm and entail ritual as well as practical acts. (c) The words of an incantation or chant. The content varies from pagan or apocryphal narrative to magical words or letters to saints’ or evangelists’ names, and so on. (d) A concluding formula that may vary from a statement such as “he will soon be well” to more directions for application, such as “Say this three times and three pater nosters and three aves. ”

A Charm after livestock has been stolen Gyf feoh sy underfangen. Gyf hit sy hors sing on his feteran oððe on his bridele. Gyf hit sy oðer feoh sing on þæt fotspor and ontend. iii. candela and dryp on þæt hofrec þæt wex þriwa. Ne mæg hit þe nan man forhelan. Gif hit sy innorf Sing þonne on feower healfe þæs huses and æne on middan: Crux christi reducat Crux christi per furtum periit inuenta est abraham tibi semitas uias montes concludat iob et flumina ad iudici[um] ligatum perducat. Judeas Crist ahengan þæt heom com to wite swa strangan gedydan heom dæda þa wyrrestan hy þæt drofe on guldon hælan hit heom to hearme micclum for þam hi hyt forhelan ne mihtan.

If livestock is stolen. If it is a horse, sing over his fetters or his bridle. If it is other animals, sing over the tracks and light three candles and drip the wax on the hoof tracks three times. No one will be able to hide it. If it is household property, sing then on the four sides of the house and once in the middle: “may the cross of Christ bring it back. ” The cross of Christ was lost through a thief and was found. May Abraham close off to you the paths, roads, and mountains. May Job also close the rivers, bring you bound to judgment. The Jews hanged Christ. That deed brought them a harsh punishment. They did to him the worst of deeds. They paid severely for that. They hid it to their own great harm, because they could not hide it completely.

Further Reading David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of English Language (Cambridge, 1995) Bill Griffiths, Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Magic (Anglo-Saxon Books, 2003) Patrick J Murphy, Unriddling the Exeter Riddles (Pennsylvania, 2011) John Morris, The Age of Arthur (Phoenix, 2001) John Morris (ed), Arthurian Period Sources: Nennius (Phillimore & Co, 1979) John Morris (ed), Arthurian Period Sources: Gildas – On the Ruin of Britain (Phillimore & Co, 1979) Stephen Pollington, Rudiments of Runelore (Anglo Saxon Books, 2008) Anne Savage (trans. ) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (Colour Library Direct, 1996) Michael Wood, In Search of the Dark Ages (BBC Books, 2006)