ANATOMY OF THE SMALL intestines The small intestine

- Slides: 10

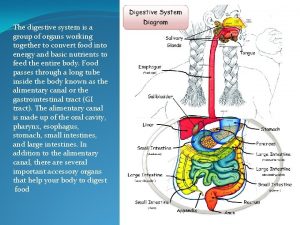

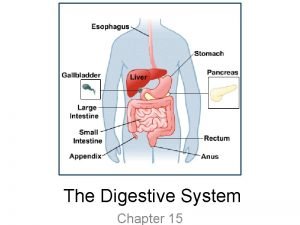

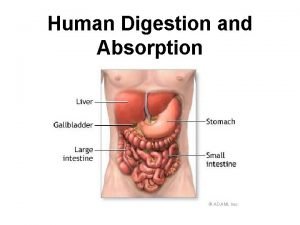

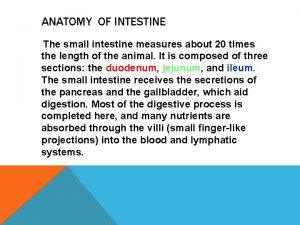

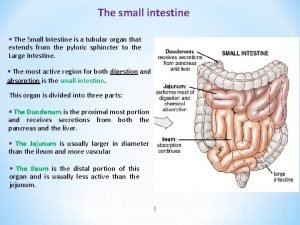

ANATOMY OF THE SMALL intestines The small intestine starts at the pylorus and extends to the ileocaecal valve. It is approximately 7 m in length and is divided into the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Its main function is in the breakdown and absorption of food products. The small bowel is present in the central and lower portion of the abdominal cavity. Its relations consist of the greater omentum and abdominal wall anteriorly. Posteriorly, it is fixed to the vertebral column by way of its mesentery. The duodenum is present proximally and is about 25 cm in length. It has no mesentery and, therefore, is the most fixed part of the small bowel. It merges into the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure. The remainder of the small bowel is made up of the jejunum and ileum. The jejunum makes up the proximal twofifths and is wider, thicker and more vascular than the ileum. It also consists of circular folds of mucous membrane (valvulae conniventes) that can be used to distinguish it from the ileum. The ileum contains larger lymph node aggregates (Peyer’s patches), and these can sometimes be lead points in cases of intussusception in the young. The arterial supply of the duodenum consists of the right gastric, the superior pancreaticoduodenal branch of the hepatic artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal branch of the superior mesenteric artery. The veins drain into the leinal and superior mesenteric. The nerves are supplied from the coeliac plexus. The jejunum and ileum are vascularised by the superior mesenteric artery through a rich plexus of vessels. The veins run a similar course. The nerve supply to the small intestines arises from sympathetic nerves around the superior mesenteric artery. Pathology such as obstruction causes visceral pain, which is felt in the periumbilical region. DIVERTICULAR DISEASE Types Diverticula can occur in a wide number of positions in the gut, from the oesophagus to the rectosigmoid. There are two varieties: 1 Congenital. All three coats of the bowel are present in the wall of the diverticulum, e. g. Meckel’s diverticulum. 2 Acquired. The wall of the diverticulum lacks a proper muscular coat. Most alimentary diverticula are thought to be acquired. Small intestine Most of these diverticula arise from the mesenteric side of the bowel, probably as the result of mucosal herniation through the point of entry of blood vessels. Duodenal diverticula There are two types: 1 Primary. Mostly occurring in older patients on the inner wall of the second and third parts , these diverticula are found incidentally on barium meal and are usually asymptomatic. They can cause problems locating the ampulla during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). 2 Secondary. Diverticula of the duodenal cap result from longstanding duodenal ulceration

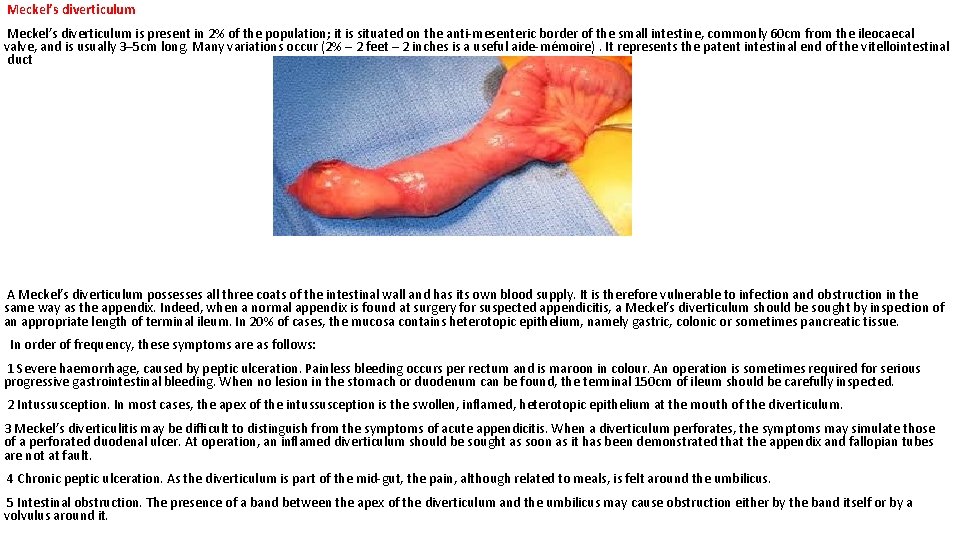

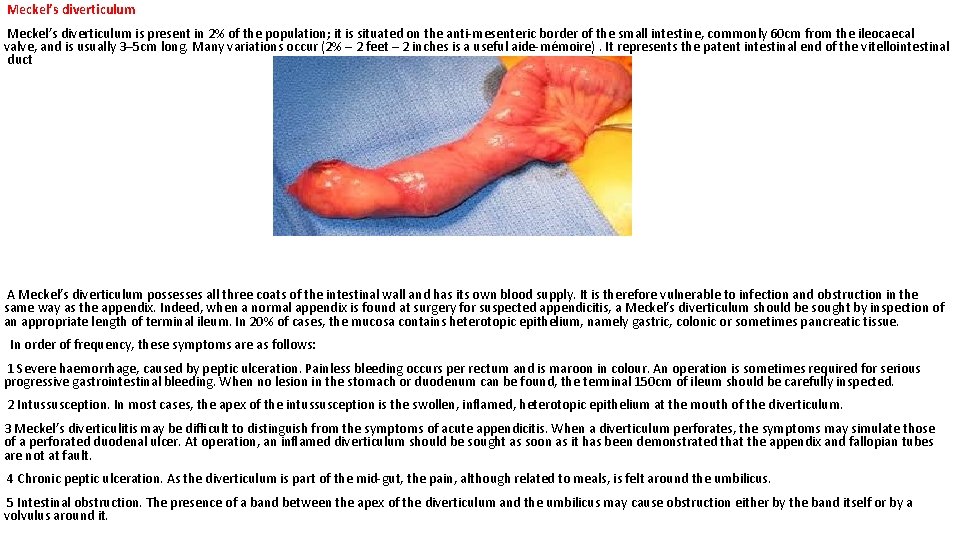

Meckel’s diverticulum is present in 2% of the population; it is situated on the anti-mesenteric border of the small intestine, commonly 60 cm from the ileocaecal valve, and is usually 3– 5 cm long. Many variations occur (2% – 2 feet – 2 inches is a useful aide-mémoire). It represents the patent intestinal end of the vitellointestinal duct A Meckel’s diverticulum possesses all three coats of the intestinal wall and has its own blood supply. It is therefore vulnerable to infection and obstruction in the same way as the appendix. Indeed, when a normal appendix is found at surgery for suspected appendicitis, a Meckel’s diverticulum should be sought by inspection of an appropriate length of terminal ileum. In 20% of cases, the mucosa contains heterotopic epithelium, namely gastric, colonic or sometimes pancreatic tissue. In order of frequency, these symptoms are as follows: 1 Severe haemorrhage, caused by peptic ulceration. Painless bleeding occurs per rectum and is maroon in colour. An operation is sometimes required for serious progressive gastrointestinal bleeding. When no lesion in the stomach or duodenum can be found, the terminal 150 cm of ileum should be carefully inspected. 2 Intussusception. In most cases, the apex of the intussusception is the swollen, inflamed, heterotopic epithelium at the mouth of the diverticulum. 3 Meckel’s diverticulitis may be difficult to distinguish from the symptoms of acute appendicitis. When a diverticulum perforates, the symptoms may simulate those of a perforated duodenal ulcer. At operation, an inflamed diverticulum should be sought as soon as it has been demonstrated that the appendix and fallopian tubes are not at fault. 4 Chronic peptic ulceration. As the diverticulum is part of the mid-gut, the pain, although related to meals, is felt around the umbilicus. 5 Intestinal obstruction. The presence of a band between the apex of the diverticulum and the umbilicus may cause obstruction either by the band itself or by a volvulus around it.

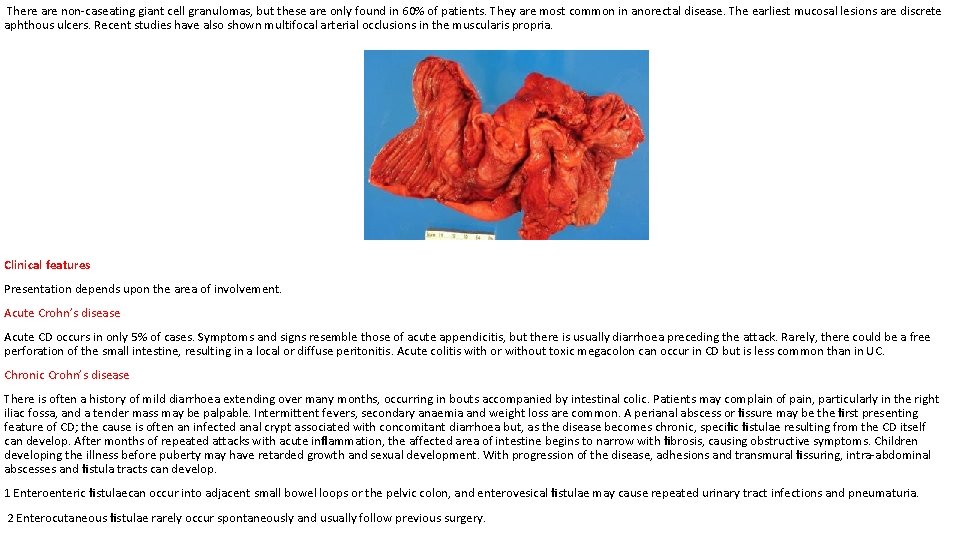

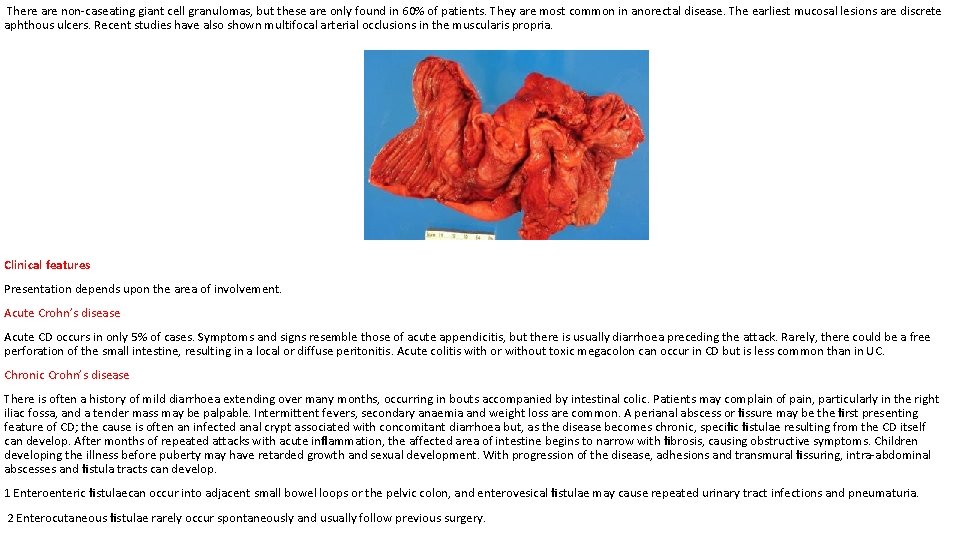

Meckel’s diverticulum can be very difficult to demonstrate by contrast radiology; small bowel enema would be the most accurate investigation. Technetium-99 m scanning may be useful in identifying Meckel’s diverticulum as a source of gastrointestinal bleeding. ‘Silent’ Meckel’s diverticulum : A Meckel’s diverticulum usually remains symptomless throughout life and is found only at necropsy. When a silent Meckel’s diverticulum is encountered in the course of an abdominal operation, it can be left provided it is wide mouthed and the wall of the diverticulum does not feel thickened. Where there is doubt and it can be removed without appreciable additional risk, it should be resected. Exceptionally, a Meckel’s diverticulum is found in an inguinal or a femoral hernia sac – Littre’s hernia. The surgical treatment is Meckel’s diverticulectomy. CROHN’S DISEASE (REGIONAL ENTERITIS) CD became widely recognised following the report in 1932 by Crohn, Ginzburg and Oppenheimer describing young adults with a chronic inflammatory disease of the ileum. It can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the lips to the anal margin, but ileocolonic disease is the most common presentation. Epidemiology It is most common in North America and northern Europe with an incidence of 5 per 100000. This has increased over the last 30 years but is now thought to be levelling off. Prevalence rates as high as 56 per 100000 have been reported in the UK. Over the last four decades, there seems to have been a rise in the incidence, which cannot be accounted for by increased diagnosis. It is slightly more common in women than in men, but is most commonly diagnosed in young patients between the ages of 25 and 40 years. There does, however, seem to be a second peak of incidence around the age of 70 years. Migration seems to increase the risk of developing CD as seen from the increased risk in migrant communities compared with their native countries. Pathogenesis there is thought to be an increased permeability of the mucous membrane. This leads to increased passage of antigens, which are thought to induce a cell-mediated inflammatory response. This results in the release of cytokines, such as interleukin-2 and tumour necrosis factor, which coordinate local and systemic responses. In CD, there is thought to be a defect in suppressor T cells, which usually act to prevent escalation of the inflammatory process. Pathology Ileal disease is the most common, accounting for 60% of cases; 30% of cases are limited to the large intestine, and the remainder are in patients with ileal disease alone or more proximal small bowel involvement. Anal lesions are common. CD of the mouth, oesophagus, stomach and duodenum is uncommon. Resection specimens show a fibrotic thickening of the intestinal wall with a narrow lumen. There is usually dilated gut just proximal to the stricture and, in the strictured area, there are deep mucosal ulcerations with linear or snake-like patterns. Oedema in the mucosa between the ulcers gives rise to a cobblestone appearance. The transmural inflammation leads to adhesions, inflammatory masses with mesenteric abscesses and fistulae into adjacent organs. The serosa is usually opaque, there is thickening in the mesentery, and mesenteric lymph nodes are enlarged. The condition is discontinuous, with inflamed areas separated from normal intestine, so called skip lesions. Under the microscope, there are focal areas of chronic inflammation involving all layers of the intestinal wall.

There are non-caseating giant cell granulomas, but these are only found in 60% of patients. They are most common in anorectal disease. The earliest mucosal lesions are discrete aphthous ulcers. Recent studies have also shown multifocal arterial occlusions in the muscularis propria. Clinical features Presentation depends upon the area of involvement. Acute Crohn’s disease Acute CD occurs in only 5% of cases. Symptoms and signs resemble those of acute appendicitis, but there is usually diarrhoea preceding the attack. Rarely, there could be a free perforation of the small intestine, resulting in a local or diffuse peritonitis. Acute colitis with or without toxic megacolon can occur in CD but is less common than in UC. Chronic Crohn’s disease There is often a history of mild diarrhoea extending over many months, occurring in bouts accompanied by intestinal colic. Patients may complain of pain, particularly in the right iliac fossa, and a tender mass may be palpable. Intermittent fevers, secondary anaemia and weight loss are common. A perianal abscess or fissure may be the first presenting feature of CD; the cause is often an infected anal crypt associated with concomitant diarrhoea but, as the disease becomes chronic, specific fistulae resulting from the CD itself can develop. After months of repeated attacks with acute inflammation, the affected area of intestine begins to narrow with fibrosis, causing obstructive symptoms. Children developing the illness before puberty may have retarded growth and sexual development. With progression of the disease, adhesions and transmural fissuring, intra-abdominal abscesses and fistula tracts can develop. 1 Enteroenteric fistulaecan occur into adjacent small bowel loops or the pelvic colon, and enterovesical fistulae may cause repeated urinary tract infections and pneumaturia. 2 Enterocutaneous fistulae rarely occur spontaneously and usually follow previous surgery.

Anal disease In the presence of active disease, the perianal skin appears bluish. Superficial ulcers with undermined edges are relatively painless and can heal with bridging of epithelium. Deep cavitating ulcers are usually found in the upper anal canal; they can be painful and cause perianal abscesses and fistulae, discharging around the anus and sometimes forwards into the genitalia. The most distressing feature of anal disease is sepsis from secondary abscesses and perianal fistulae. Remarkably, the rectal mucosa is often spared and may feel normal on rectal examination. If it is involved, however, it will feel thickened, nodular and irregular. Investigation Laboratory A full blood count needs to be performed to exclude anaemia. There is usually a fall in albumin, magnesium, zinc and selenium, especially in active disease. Protein levels that correspond to disease activity include C-reactive protein and orosomucoid. Endoscopy Sigmoidoscopic examination may be normal or show minimal involvement. However, ulceration in the anal canal will be readily seen. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms may have to be investigated by way of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which may reveal deep longitudinal ulcers and cobblestone mucosa. Capsule endoscopy may also have a useful role in those with chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Imaging Barium enema will show similar features to those of colonoscopy in the colon. The best investigation of the small intestine is small bowel enema. This will show up areas of delay and dilatation. The involved areas tend to be narrowed, irregular and, sometimes, when a length of terminal ileum is involved, there may be the string sign of Kantor. Sinograms are useful in patients with enterocutaneous fistulae. CT scans are used in patients with fistulae and those with intra-abdominal abscesses and complex involvement. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to be useful in assessing perianal disease. Treatment Medical therapy Steroids are the mainstay of treatment. These are effective in inducing remission in moderate to severe disease in 70– 80% of cases. Steroids can also be used as topical agents in the rectum with reduced systemic bioavailability, but long-term use causes adrenal suppression. They are better at inducing remission than mesalamine but has no role in maintenance. Antibiotics Those who have symptoms and signs of a mass or an abscess are also treated with antibiotics. Metronidazole is used, especially in perianal disease. Its mechanism is unknown and is thought to play a role in suppressing cell-mediated immunity. In a randomised controlled trial, it reduced disease activity in ileocolonic and colonic disease, but not small bowel disease.

Immunomodulatory agents Azathioprine is used for its additive and steroid-sparing effect and is now standard maintenance therapy. Monoclonal antibody Infliximab, the murine chimeric monoclonal antibody directed towards tumour necrosis factor alpha, targets patients with severe, active disease who are refractory to ‘conventional’ treatments and who are at high risk of surgical interventions. Nutritional support is essential. Severely malnourished people may require intravenous feeding or nasoenteric feeding regimens. Anaemia, hypoproteinaemia and electrolyte, vitamin and metabolic bone problems must all be addressed. It has been shown that parenteral nutrition can induce remission in up to 80% of patients, which is comparable to steroids, but there is no synergism or additive effect. However, relapse is high after a short duration. . Indications for surgery Surgical resection will not cure CD. Surgery is therefore focused on the complications of the disease. As many of these indications for surgery may be relative, joint management by an aggressive physician and a conservative surgeon is thought to be ideal. These complications include: • recurrent intestinal obstruction; • bleeding; • perforation; • failure of medical therapy; • intestinal fistula; • fulminant colitis; • malignant change; • perianal disease. Surgery In patients with active CD, prompt surgery is important when medical treatment fails. The main surgical principle is to preserve functional gut length and maintain gut function. Resection is kept to a minimum so as to deal with the local problem. 1 Ileocaecal resection is the usual procedure for ileocaecal disease with a primary anastomosis between the ileum and the ascending or transverse colon depending on the extent of the disease.

2 Segmental resection. Short segments of small or large bowel involvement can be treated by segmental resection. The usual indication is stricture. 3 Colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis. In patients with widespread colonic disease with rectal sparing and a normal anus. this can be a useful option. 4 Emergency colectomy. This accounts for 8% of operations for acute colonic disease. The indications are similar to those for UC. If medical treatment induces remission, then delayed surgery is sensible because of the high risk of recurrent active disease. 5 Laparoscopic surgery. Resections and diversion are safe in uncomplicated CD. This is coupled with extracorporeal anastomosis and results in small peri-umbilical incisions. The advantages include better cosmesis and early discharge. 6 Temporary loop ileostomy. This can be used either in patients with acute distal CD, allowing remission and later restoration of continuity, or in patients with severe perianal or rectal disease. 7 Proctocolectomy. Patients with colonic and anal disease failing to respond to medical treatment or defunction will eventually require a permanent ileostomy. 8 Strictureplasty. Multiple strictured areas of CD can be treated by a local widening procedure, strictureplasty, to avoid excessive small bowel resection. 9 Anal disease is usually treated conservatively by simple drainage of abscesses, placing setons around any fistulae and, occasionally in patients with inactive disease, primary repair of a rectovaginal or high fistula-in-ano could be attempted. _____________________ GOOD LUCK