Analyzing and Transforming Binary Code for Fun Profit

Analyzing and Transforming Binary Code (for Fun & Profit) Gopal Gupta R. Venkitaraman, R. Reghuramalingam The University of Texas at Dallas 11/15/2004

The Components Marketplace • COTS Component based software engg has been touted as a pathway to improving productivity (now called web-services) • However: many obstacles to be surmounted: • Discovering that the needed component exists • Checking that the component is compliant • Checking that the component is secure

Software Reuse & System Integration Companies Cost of Project But, the Integrated System does not work

![Our work • Design of a Universal Service-Semantics Description Language (USDL) [ECOWS’ 05] • Our work • Design of a Universal Service-Semantics Description Language (USDL) [ECOWS’ 05] •](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/ff09bc9e72210fa85f5762b1e402a566/image-4.jpg)

Our work • Design of a Universal Service-Semantics Description Language (USDL) [ECOWS’ 05] • Construction of automatic service discovery and service composition engines • Once a service/component has been downloaded, ensuring that it is compliant & safe

Analyzing & Transforming Binaries • Most of the time when a component/service is • • obtained, only the binary code is available (source code is properietary). Compliance and safety checks have to be done on the binary code. Our thesis: this is quite feasible Illustrate compliance check with an example from DSP industry. Illustrate code securing by transforming binary for protecting from buffer overflow attacks.

Analyzing DSP codes: Motivation • Facilitate software reuse in the DSP industry • DSP h/w manufacturers are interested in developing DSP software COTS components so that time to market is small • DSP components generally available only in binary form (no source code) • DSP software uses low-level optimizations for efficiency • Need to ensure that these optimizations do not interfere with reusability

Our Framework • We develop necessary and sufficient conditions that ensure that a software binary is reusable • We relate these conditions to TI’s XDAIS standard • We show static analysis can be used to check if these conditions hold • We illustrate this through analysis for detecting hard coded pointers

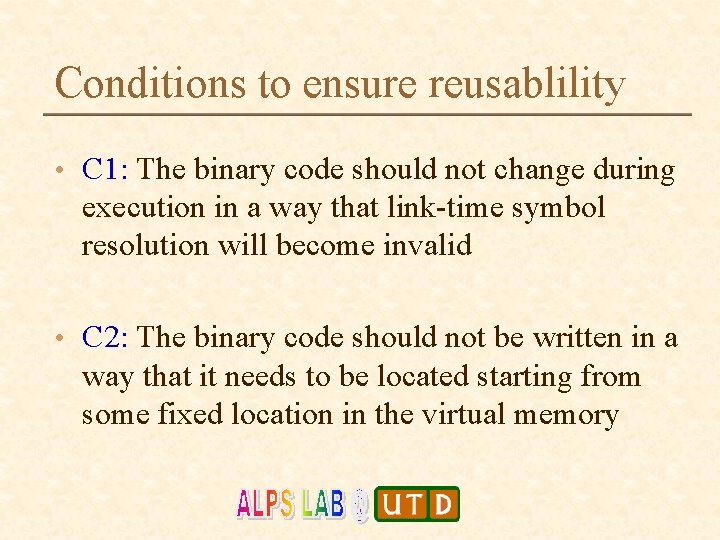

Conditions to ensure reusablility • C 1: The binary code should not change during execution in a way that link-time symbol resolution will become invalid • C 2: The binary code should not be written in a way that it needs to be located starting from some fixed location in the virtual memory

Broadening the Conditions • C 1 and C 2 are hard to characterize and even harder to detect • So, broaden the conditions C 1 and C 2 to get conditions C 3 and C 4

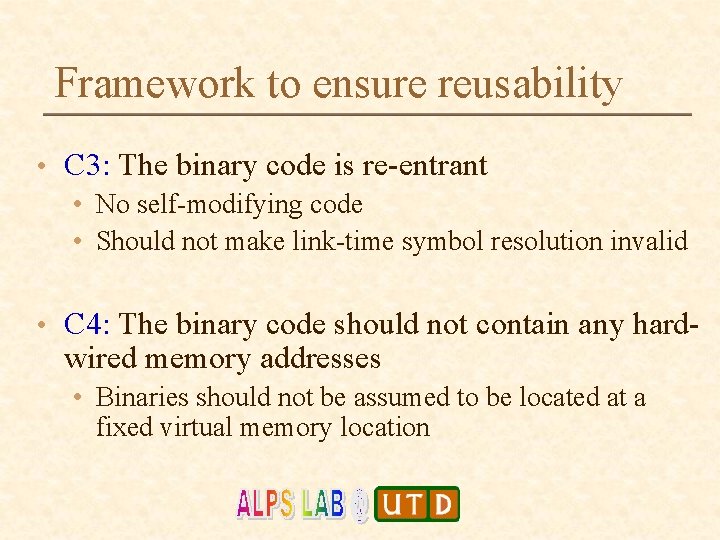

Framework to ensure reusability • C 3: The binary code is re-entrant • No self-modifying code • Should not make link-time symbol resolution invalid • C 4: The binary code should not contain any hard- wired memory addresses • Binaries should not be assumed to be located at a fixed virtual memory location

TI XDAIS Standard • Contains 35 rules and 15 guidelines • SIX General Programming Rules • No tool currently exists to check for compliance • We want to build a tool to ENFORCE software compliance for these rules

XDAIS – General Programming Rules 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) All programs should follow the runtime conventions of TI’s C programming language Programs must be re-entrant No hard coded data memory locations No hard coded program memory locations Algorithms must characterize their ROM-ability No peripheral device accessed directly

Advantages Of Compliant Code • Allows system integrators to easily migrate between TI DSP chips • Subsystems from multiple software vendors can be integrated into a single system • Programs are framework-agnostic: the same program can be efficiently used in virtually any application

XDAIS vs. Our Framework • Rule 1 is not really a programming rule, since it requires compliance with TI's definition of the C Language • Rules 2 through 5 are manifestations of conditions C 3 and C 4 above. • Rules 2 and 5 correspond to condition C 3 • Rules 3, 4, and 6 correspond to condition C 4

XDAIS – General Programming Rules 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) All programs should follow the runtime conventions of TI’s C programming language Programs must be re-entrant No hard coded data memory locations No hard coded program memory locations Algorithms must characterize their ROM-ability No peripheral device accessed directly

Problem and Solution • Problem: Detection of hard coded addresses in programs without accessing source code. • Solution: “Static Program Analysis of Assembly Code”

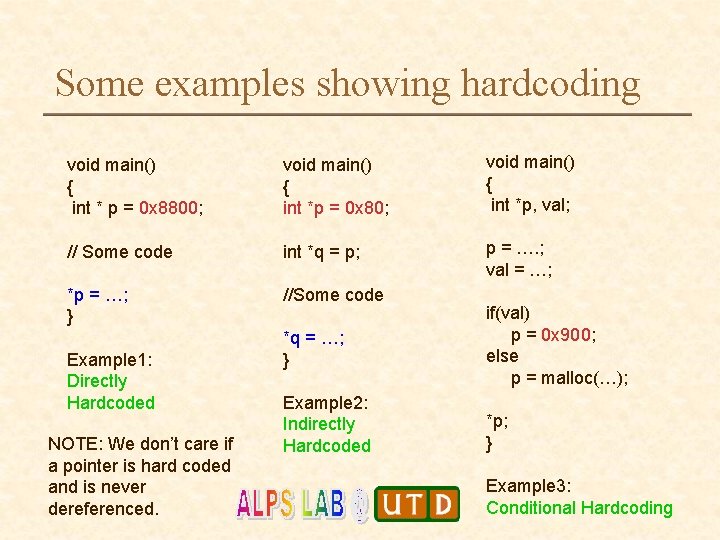

Some examples showing hardcoding void main() { int * p = 0 x 8800; void main() { int *p = 0 x 80; void main() { int *p, val; // Some code int *q = p; p = …. ; val = …; *p = …; } //Some code Example 1: Directly Hardcoded NOTE: We don’t care if a pointer is hard coded and is never dereferenced. *q = …; } if(val) p = 0 x 900; else p = malloc(…); Example 2: Indirectly Hardcoded *p; } Example 3: Conditional Hardcoding

Static Analysis • Un-decidability: Impossible to build a tool that will precisely detect hard coding • Static Analysis: defined as any analysis of a program carried out without completely executing the program

Interest in Static Analysis • “We actually went out and bought for 30 million dollars, a company that was in the business of building static analysis tools and now we want to focus on applying these tools to large-scale software systems” • Remarks by Bill Gates, 17 th Annual ACM Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages and Application, November 2002.

Hard Coded Addresses • Bad Programming Practice. • Results in non relocatable code. • Results in non reusable code.

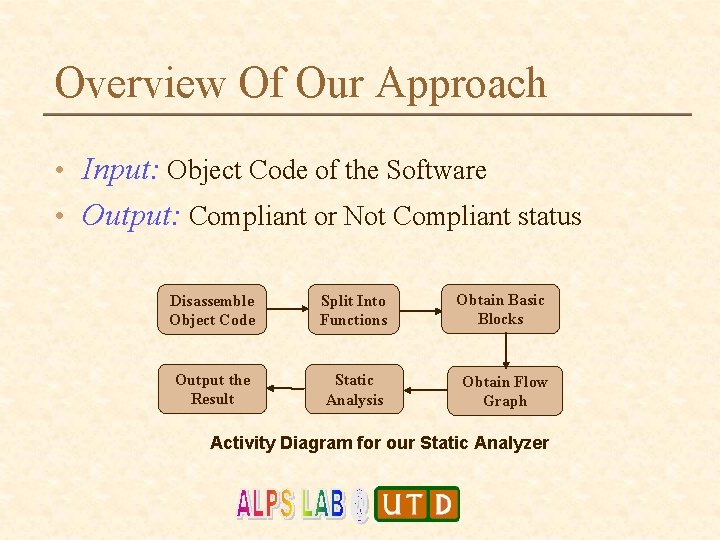

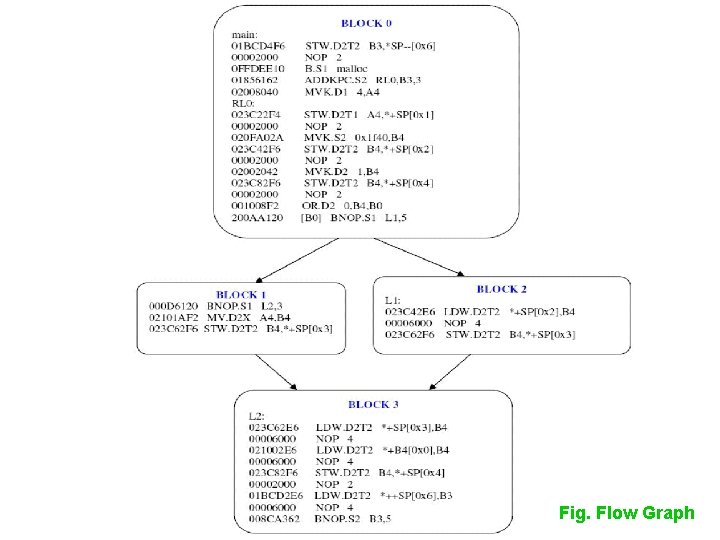

Overview Of Our Approach • Input: Object Code of the Software • Output: Compliant or Not Compliant status Disassemble Object Code Split Into Functions Obtain Basic Blocks Output the Result Static Analysis Obtain Flow Graph Activity Diagram for our Static Analyzer

Basic Aim Of Analysis • Find a path to trace pointer origin. • Problem: Exponential Complexity • Static Analysis approximation makes it linear

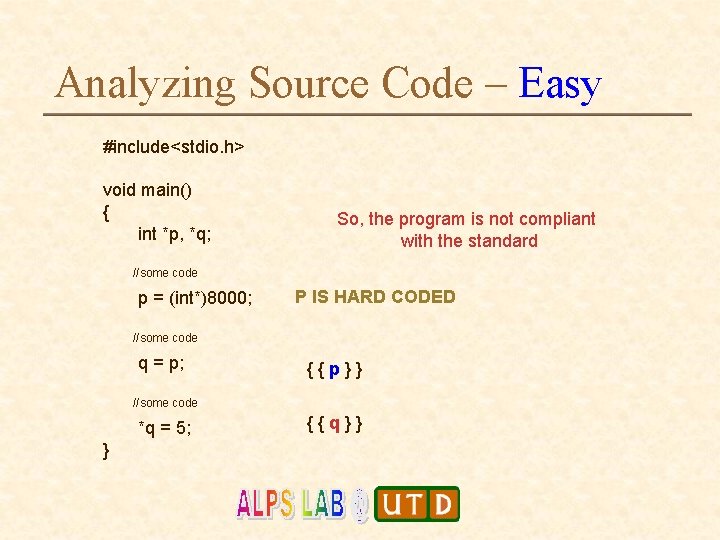

Analyzing Source Code – Easy #include<stdio. h> void main() { int *p, *q; So, the program is not compliant with the standard //some code p = (int*)8000; P IS HARD CODED //some code q = p; {{p}} //some code *q = 5; } {{q}}

Analyzing Assembly Code is Hard • Problem • No type information is available • Instruction level pipeline and parallelism • Solution • Backward analysis • Use Abstract Interpretation

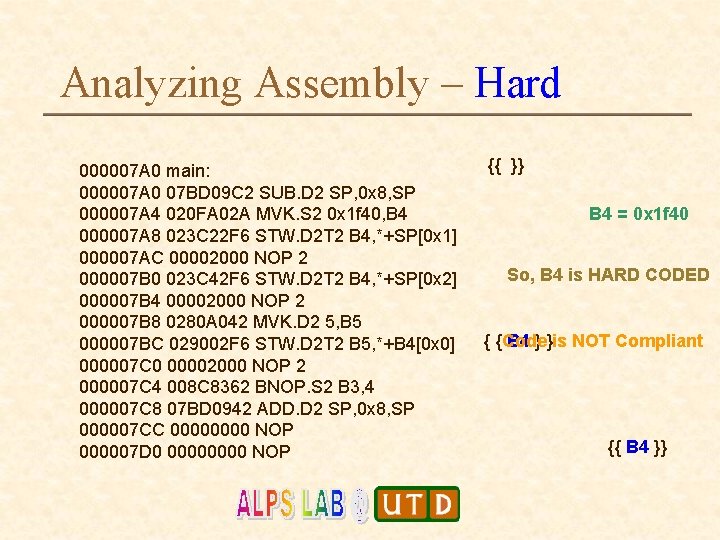

Analyzing Assembly – Hard 000007 A 0 main: 000007 A 0 07 BD 09 C 2 SUB. D 2 SP, 0 x 8, SP 000007 A 4 020 FA 02 A MVK. S 2 0 x 1 f 40, B 4 000007 A 8 023 C 22 F 6 STW. D 2 T 2 B 4, *+SP[0 x 1] 000007 AC 00002000 NOP 2 000007 B 0 023 C 42 F 6 STW. D 2 T 2 B 4, *+SP[0 x 2] 000007 B 4 00002000 NOP 2 000007 B 8 0280 A 042 MVK. D 2 5, B 5 000007 BC 029002 F 6 STW. D 2 T 2 B 5, *+B 4[0 x 0] 000007 C 0 00002000 NOP 2 000007 C 4 008 C 8362 BNOP. S 2 B 3, 4 000007 C 8 07 BD 0942 ADD. D 2 SP, 0 x 8, SP 000007 CC 0000 NOP 000007 D 0 0000 NOP {{ }} B 4 = 0 x 1 f 40 So, B 4 is HARD CODED { {Code B 4 } }is NOT Compliant {{ B 4 }}

Abstract Interpretation Based Analysis • Domains from which variables draw their values are approximated by abstract domains • The original domains are called concrete domains

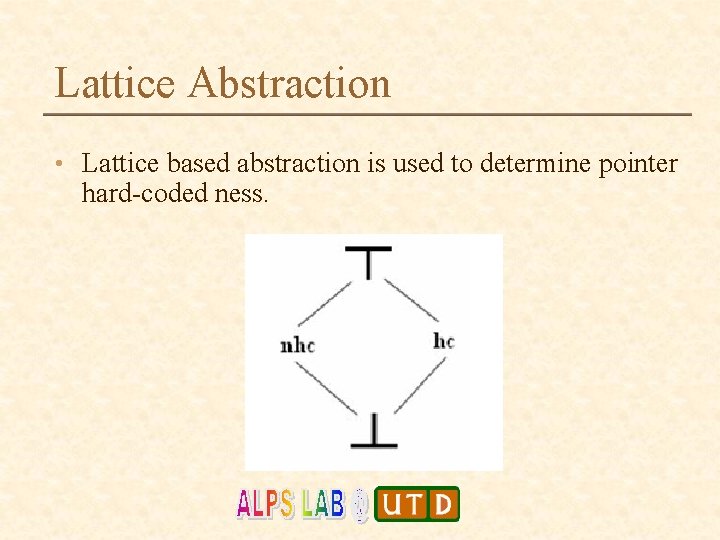

Lattice Abstraction • Lattice based abstraction is used to determine pointer hard-coded ness.

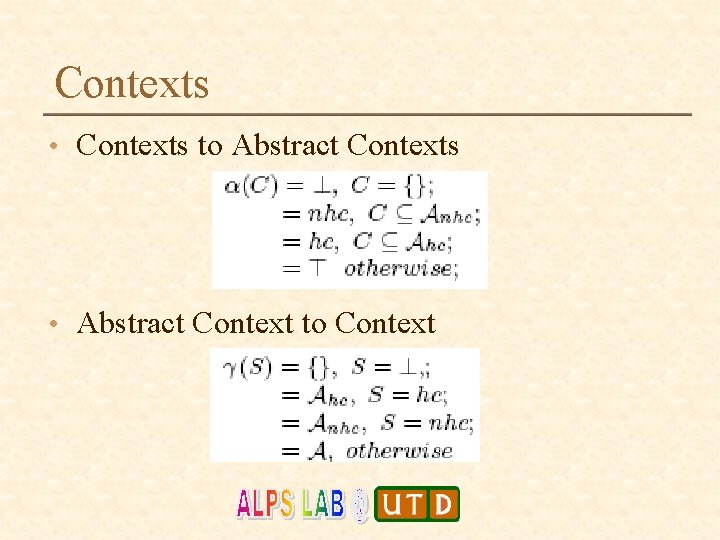

Contexts • Contexts to Abstract Contexts • Abstract Context to Context

Phases In Analysis • Phase 1: Find the set of dereferenced pointers • Phase 2: Check the safety of dereferenced pointers

Building Unsafe Sets (Phase 1) • The first element is added to the unsafe set during pointer dereferencing. • E. g. If “*Reg” in the disassembled code, the unsafe set is initialized to {Reg}. • ‘N’ Pointers Dereferenced ‘N’ Unsafe sets • Maintained as SOUS (Set Of Unsafe Sets)

Populating Unsafe Sets (Phase 2) • For e. g. , if • Reg = reg 1 + reg 2, the element “Reg” is deleted from the unsafe set, and the elements “reg 1”, “reg 2”, are inserted into the unsafe set. • Contents of the unsafe set will now become {reg 1, reg 2}.

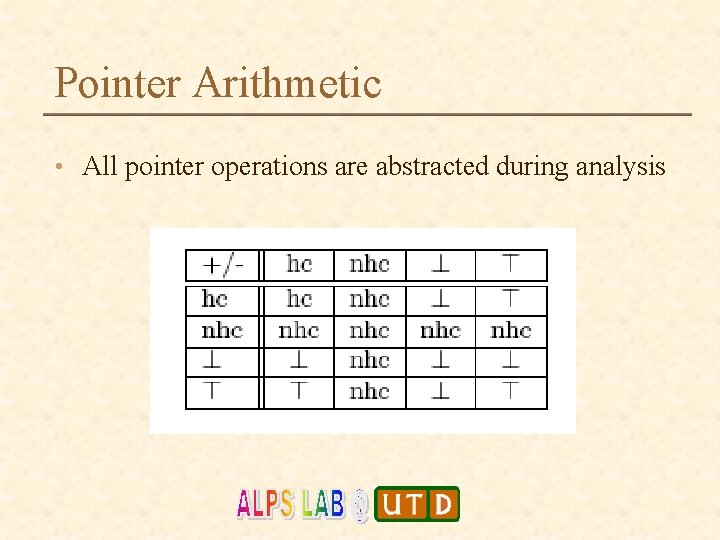

Pointer Arithmetic • All pointer operations are abstracted during analysis

Handling Loops • Complex: # iterations of loop may not be known until runtime. • Cycle the loop until the unsafe set reaches a “fixed point”. • No new information is added to the unsafe set during successive iterations.

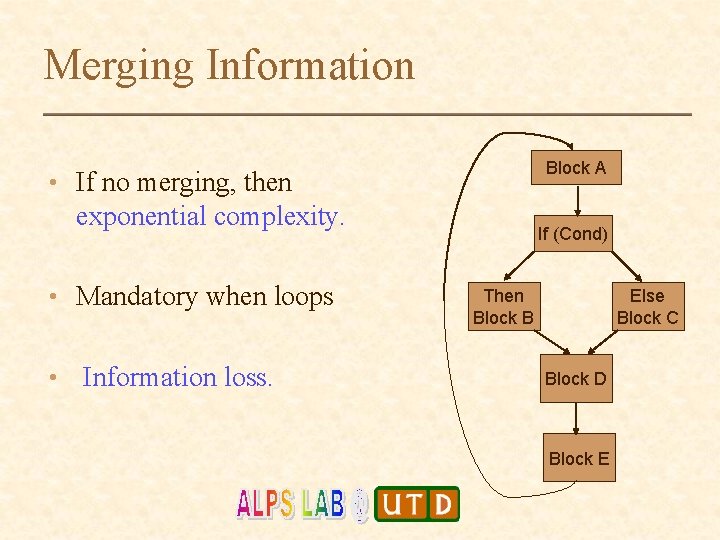

Merging Information Block A • If no merging, then exponential complexity. • Mandatory when loops • Information loss. If (Cond) Then Block B Else Block C Block D Block E

Extensive Compliance Checking • Handle all cases that occur in programs • Single pointer, double pointer, triple pointer… • Global pointer variables • Static and Dynamic arrays

Extensive Compliance Checking • Loops – all forms (e. g. for, while…) • Function calls • Pipelining and Parallelism • Merging information from multiple paths

Proof – Analysis is Sound • Consistency of α and γ functions is established by showing the existence of Galois Connection. That is, • x = α(γ(x)) • y belongs to γ(α(y))

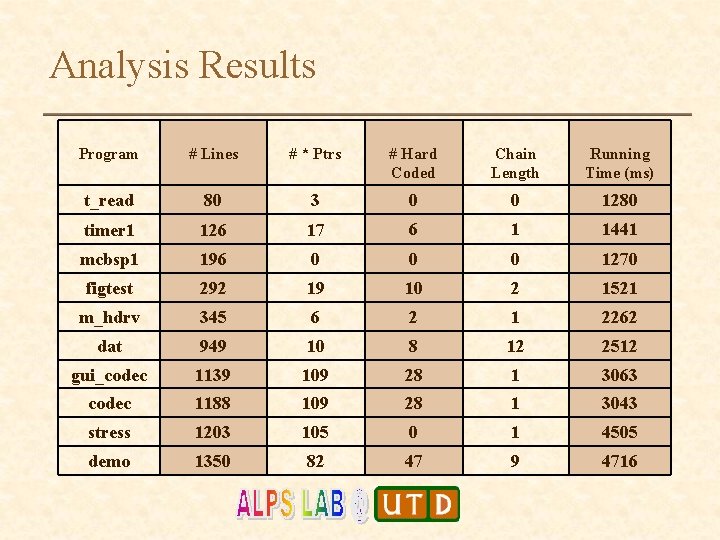

Analysis Results Program # Lines # * Ptrs # Hard Coded Chain Length Running Time (ms) t_read 80 3 0 0 1280 timer 1 126 17 6 1 1441 mcbsp 1 196 0 0 0 1270 figtest 292 19 10 2 1521 m_hdrv 345 6 2 1 2262 dat 949 10 8 12 2512 gui_codec 1139 109 28 1 3063 codec 1188 109 28 1 3043 stress 1203 105 0 1 4505 demo 1350 82 47 9 4716

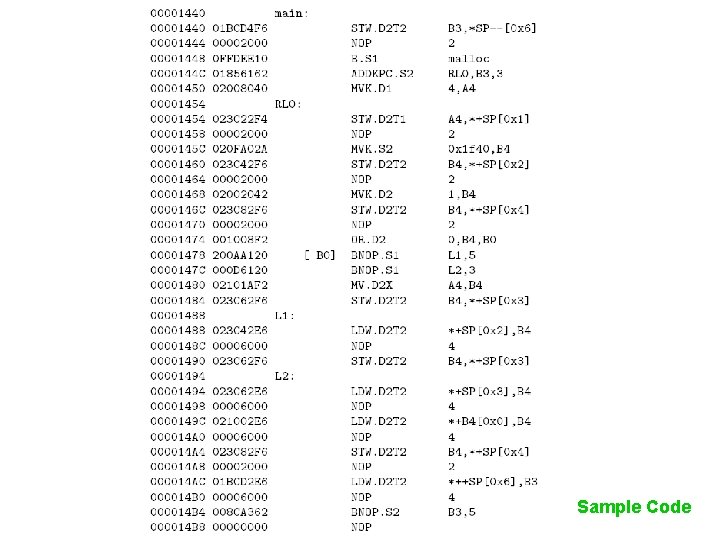

Sample Code

Fig. Flow Graph

Related Work • UNO Project – Bell Labs • Analyze at source level • TI XDAIS Standard • Contains 35 rules and 15 guidelines. • SIX General Programming Rules. • No tool currently exists to check for compliance.

Current Status and Future Work • Prototype Implementation done • But, context insensitive, intra-procedural • Extend to context sensitive, inter-procedural. • Extend compliance check for other rules.

So… • Software reuse is an important issue in the industry, particularly the DSP industry • Checking compatibility of code w/ reusability standards at assembly level is possible • A Static Analysis based technique is useful and practical

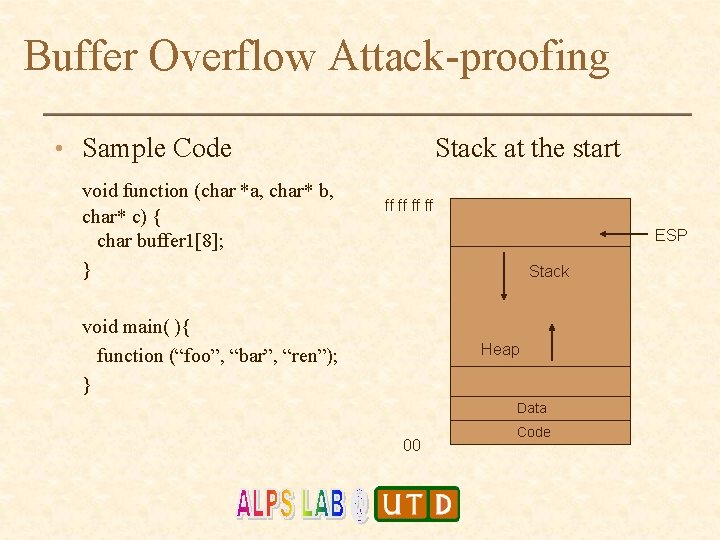

Buffer Overflow Attack-proofing • Sample Code void function (char *a, char* b, char* c) { char buffer 1[8]; } Stack at the start ff ff ESP Stack void main( ){ function (“foo”, “bar”, “ren”); } Heap Data 00 Code

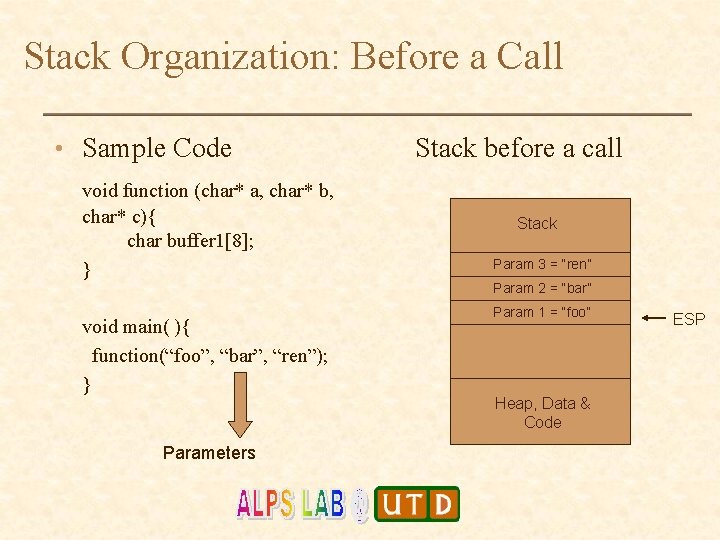

Stack Organization: Before a Call • Sample Code void function (char* a, char* b, char* c){ char buffer 1[8]; } Stack before a call Stack Param 3 = “ren” Param 2 = “bar” void main( ){ function(“foo”, “bar”, “ren”); } Parameters Param 1 = “foo” Heap, Data & Code ESP

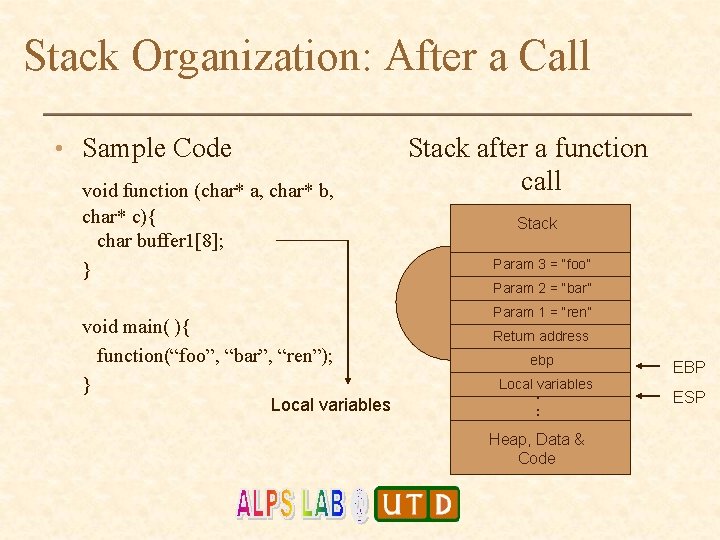

Stack Organization: After a Call • Sample Code void function (char* a, char* b, char* c){ char buffer 1[8]; } Stack after a function call Stack Param 3 = “foo” Param 2 = “bar” void main( ){ function(“foo”, “bar”, “ren”); } Local variables Param 1 = “ren” Return address ebp Local variables . . . Heap, Data & Code EBP ESP

![Buffer Overflow • Sample Code • void function (char *str){ char buffer 1[8]; strcpy Buffer Overflow • Sample Code • void function (char *str){ char buffer 1[8]; strcpy](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/ff09bc9e72210fa85f5762b1e402a566/image-47.jpg)

Buffer Overflow • Sample Code • void function (char *str){ char buffer 1[8]; strcpy (buffer 1, str); } Strcpy writes void main( ){ char large_str[256] ; for (int i=0; i<255; i++) large_str[i] = ‘A’; function(large_str); Label: } New return address =4141 Stack showing buffer overflow Stack 41 41 41 Large_str (Size = 64) Label: 41 41 Return address 41 41 Pointer 41 41 Garbage ebp Buffer 1 (Size = 2)

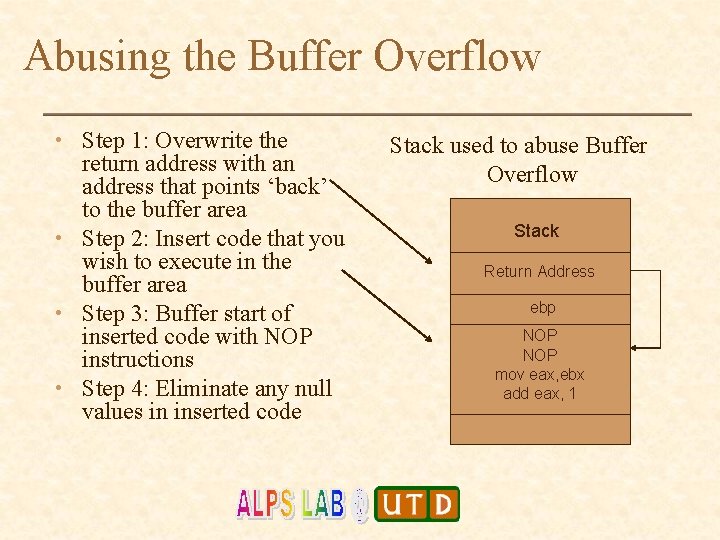

Abusing the Buffer Overflow • Step 1: Overwrite the return address with an address that points ‘back’ to the buffer area • Step 2: Insert code that you wish to execute in the buffer area • Step 3: Buffer start of inserted code with NOP instructions • Step 4: Eliminate any null values in inserted code Stack used to abuse Buffer Overflow Stack Return Address ebp NOP mov eax, ebx add eax, 1

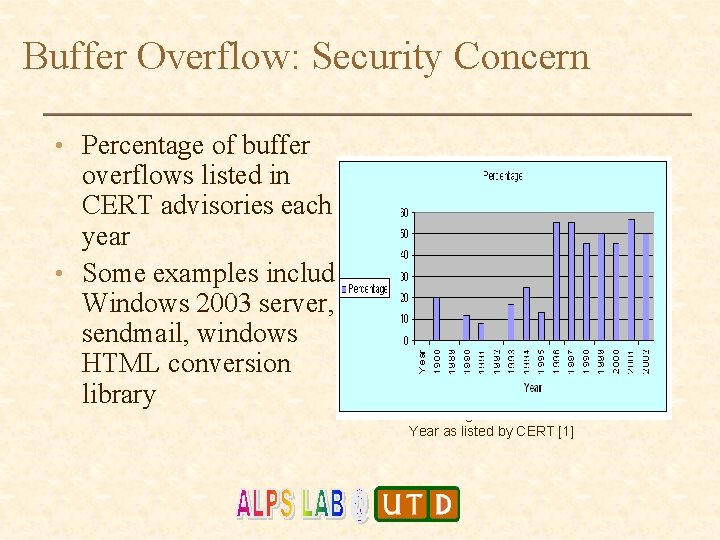

Buffer Overflow: Security Concern • Percentage of buffer overflows listed in CERT advisories each year • Some examples include Windows 2003 server, sendmail, windows HTML conversion library Percentage of Buffer Overflows Per Year as listed by CERT [1]

Buffer Overflow Solutions • RAD: RAD stores the return address in RAR area • It is a gcc compiler patch. All code has to recompiled • Stackguard: Stackguard inserts a ‘canary’ word to protect return address • The ‘canary’ word can be compromised • Splint: Splint allows the user to write annotations in the code that define allocated and used sizes • User is required to write annotations • Wagner’s Prevention Method: Static analysis solution • Depends on source code availability

Binary. Secure: An Overview • Buffer Overflow is achieved by overwriting the return address • If return addresses are recorded in a separate area, away from the buffer overflow, then they cannot be overwritten • So modify the memory organization to add a new auxiliary return address stack, allocated in an area opposite to the direction of buffer write/overflow --When a function call returns, it uses the return address from this new stack • Transform the binary to make it consistent with this new memory organization.

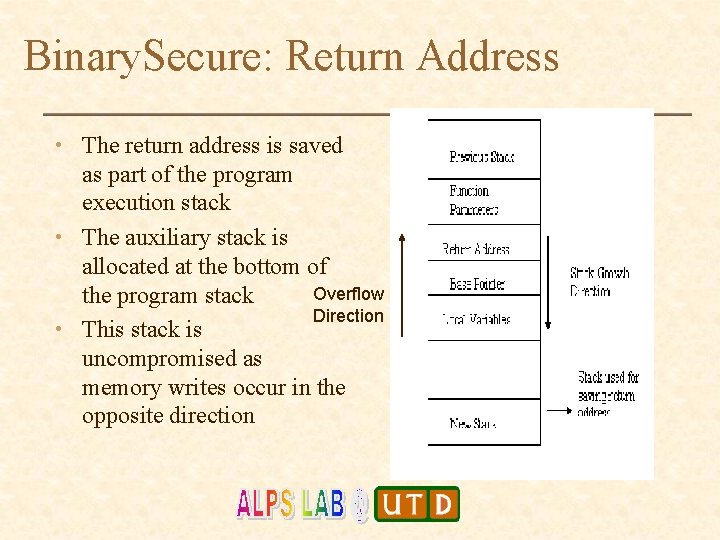

Binary. Secure: Return Address • The return address is saved as part of the program execution stack • The auxiliary stack is allocated at the bottom of Overflow the program stack Direction • This stack is uncompromised as memory writes occur in the opposite direction

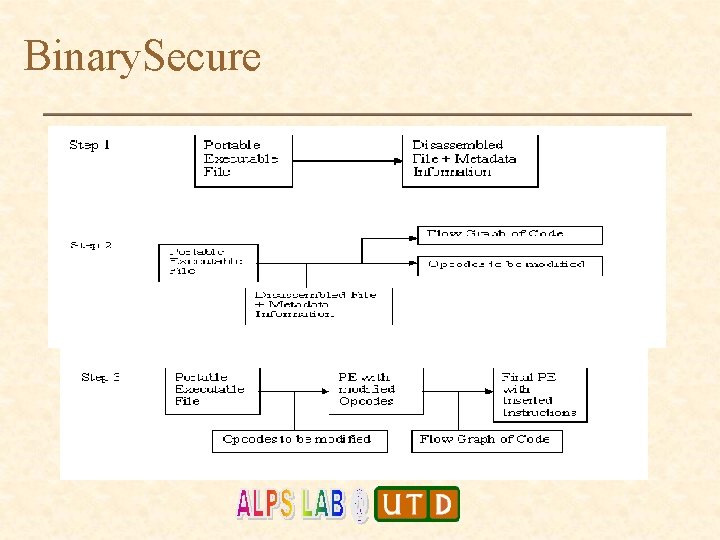

Binary. Secure

Binary Secure: Specifications • These are some of the conditions that must hold • • • Code must be re-entrant Code should not modify the stack pointer Processor: Intel x 386 Compiler: Dev C++ compiler 4. 9. 9. 1 Platform: Windows

Advantages • Binary code is analysed. This can be used on third-party software where one does not have access to source code. • Run-time checks require modification to the source code (Splint) • Compiler modifications are costly and performing changes to all available compilers is not possible. (RAD, Stackguard) • Return addresses are stored on the stack itself. Hence overhead incurred while accessing addresses in other areas is reduced.

Software Reuse & System Integration Select ONLY Compliant/Safe Software WOW!!!! It works…

More Information 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. R. Venkitaraman and G. Gupta, Static Program Analysis of Embedded Executable Assembly Code. ACM CASES, September 2004 R. Venkitaraman and G. Gupta, Framework for Safe Reuse of Software Binaries. ICDCIT, December 2004 Master’s Thesis– R. Venkitaraman, Framework for Safe Reuse Of Software Binaries, The University of Texas at Dallas; Dec 2004. Master’s Thesis – R. Reguramalingam, Binary. Secure: A Tool for Buffer Overflow Attack Proofing of Software Binaries; Dec. 2005 S. Kona, A. Bansal, L. Simon, A. Mallya, G. Gupta, T. Hite. Universal Service-Semantics Description Lang. ECOWS’ 05

Questions…

- Slides: 58