Analyzing a Poem The Magical Art of Squeezing

- Slides: 20

Analyzing a Poem: The Magical Art of Squeezing Blood from a Stone

For some students, reading and interpreting poetry is an unwelcome challenge; for others, it is an incomparable pleasure. Because poetry is intense thought compactly expressed—a distillation of language, if you will—it can be difficult to comprehend. In this sense, poetry is not unlike a puzzle—it is a matter of piecing together the poet’s vision. Much of the pleasure lies in solving the puzzle. Before attempting the analysis of a poem, it is important to read it through at least three or four times—this point cannot be overemphasized. Often, the title—which may or may not be ambiguous—is a major clue to the meaning of a poem. After reading a poem—particularly when it seems obscure—consider the title thoughtfully. It may be revealing.

An initial analysis of a poem begins with an examination of its form. • Is it divided into stanzas or verses (the equivalent of paragraphs in prose)? • If so, are these divisions in any way significant? • Divisions of three, six, seven, nine, or twelve may be significant, since these are sacred or mystic numbers connected with Judaeo-Christian Tradition, Greek or Roman Mythology, Astrology, or the Pagan Calendar: o 3 – Trinity, Godhead, That Which Is Sacred o 6 – Number of Imperfection or Incompletion o 7 – Days of Creation, Number of Days in a Week o 9 – Number of Perfection, the Triple Trinity o 12 – Number of Nations in Ancient Israel, Number of Apostles, Number of Olympians, Number of Months in a Year.

• Does the poem rhyme? (i. e. , Is there an observable repetition of sounds, either at the ends of each line, or within the lines? ) • Does it have meter? (i. e. , Is it divided into an observable syllabic pattern? ) o Twelve Syllables (Iambic Hexameter, also called the Alexandrine) – a sultry, dream-like cadence. o Ten syllables (Iambic Pentameter) – the cadence of human speech (in English) or of the beating heart. o Eight syllables – stately, solemn cadence. o Six syllables – a light-hearted and silly cadence. o A mixture of eight and six syllables – combines stately with silly and creates a cadence at odds with itself, hence it sounds utterly ridiculous.

You may also wish to ask whether the poem is in blank verse or free verse. • Blank verse does not rhyme, but it has meter. • Free verse has neither rhyme nor meter. Last of all, you may wish to ask why the poet has chosen the particular sounds he (or she) has: • Is there evidence of consonance, assonance, etc. ? • In what way do the sounds enhance the poem? • F and S and other soft sounds may represent wind blowing, or water rushing. • P, B, and G sounds may give a harsher feel to a poem or create a staccato effect, as of gunfire. • Hard C, K, and G sounds may mimic noise. Psssshht. . .

Ask yourself, every step of the way, why the poet has made the choices he (or she) has: • Why rhymed meter? • Why blank verse? • Why free verse? • Why this many verses? • Why this many syllables? • Why this many stanzas? • Why these numbers? • Why these sounds? • Why these combinations of sound? • etc. Why?

It is of course useful to know whether the form of the poem is of a recognizable genre: • A ballad (a poem originally intended to be sung) • An epic poem (a long, story-like poem of indeterminate length) • A sonnet (fourteen lines of rhymed iambic pentameter) • A villanelle (a nineteen-line poem built on two rhymes) • A limerick (a nonsense poem) • Haiku (a form of Japanese poetry) • etc.

It is also useful to identify whether a poem is of the narrative or lyric variety. • A narrative poem tells a story and is meant to entertain. • A lyric poem is more meditative or reflective in nature and is meant to provoke thought. These poems are not always readily understood.

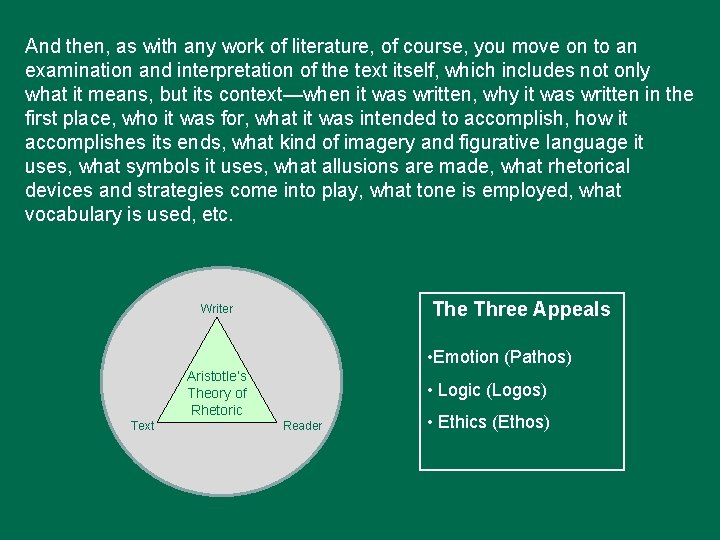

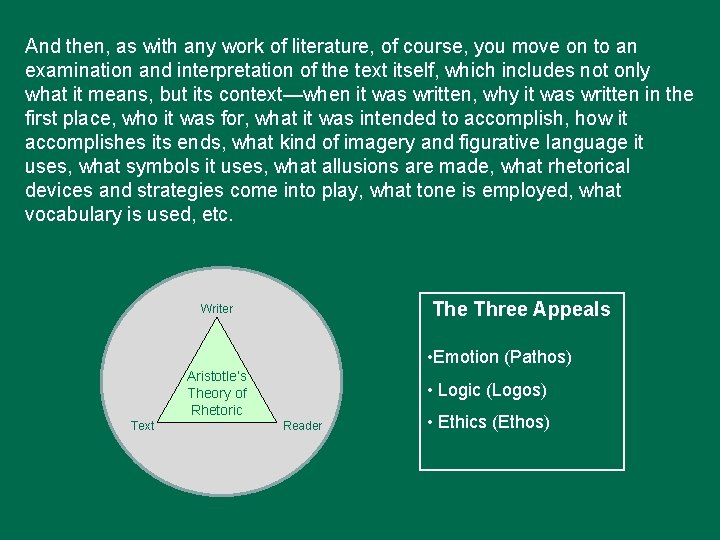

And then, as with any work of literature, of course, you move on to an examination and interpretation of the text itself, which includes not only what it means, but its context—when it was written, why it was written in the first place, who it was for, what it was intended to accomplish, how it accomplishes its ends, what kind of imagery and figurative language it uses, what symbols it uses, what allusions are made, what rhetorical devices and strategies come into play, what tone is employed, what vocabulary is used, etc. The Three Appeals Writer • Emotion (Pathos) Aristotle’s Theory of Rhetoric Text • Logic (Logos) Reader • Ethics (Ethos)

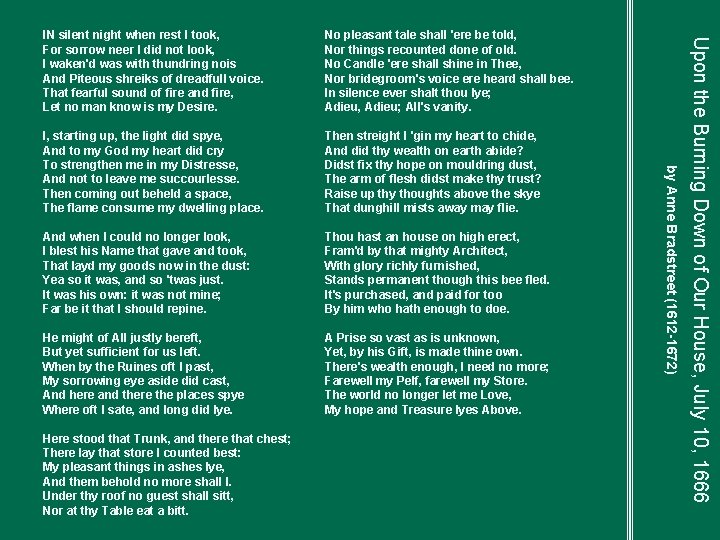

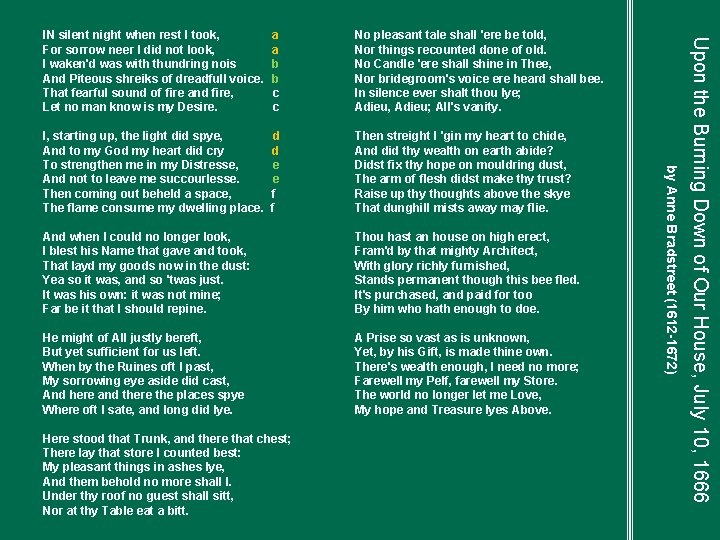

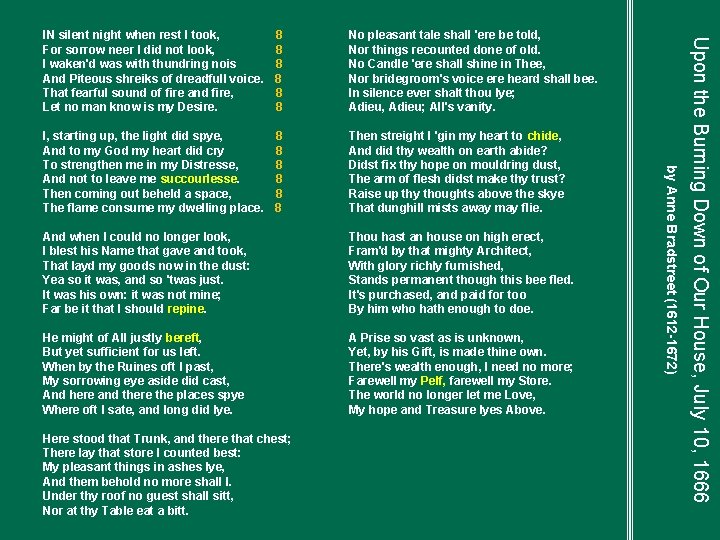

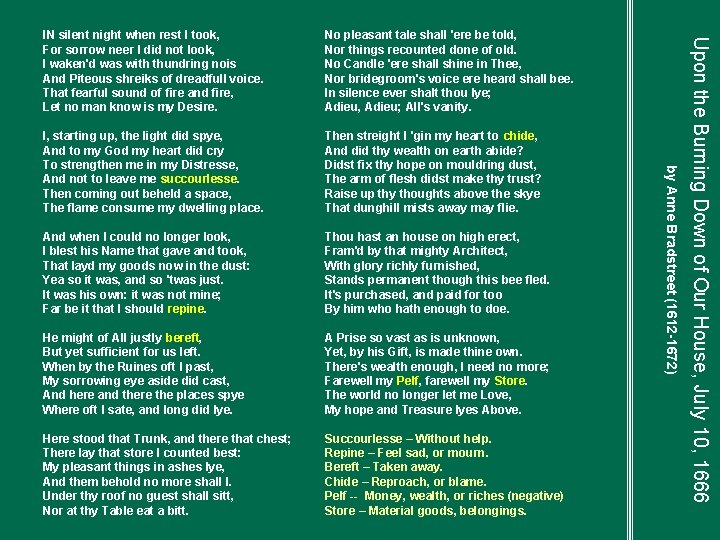

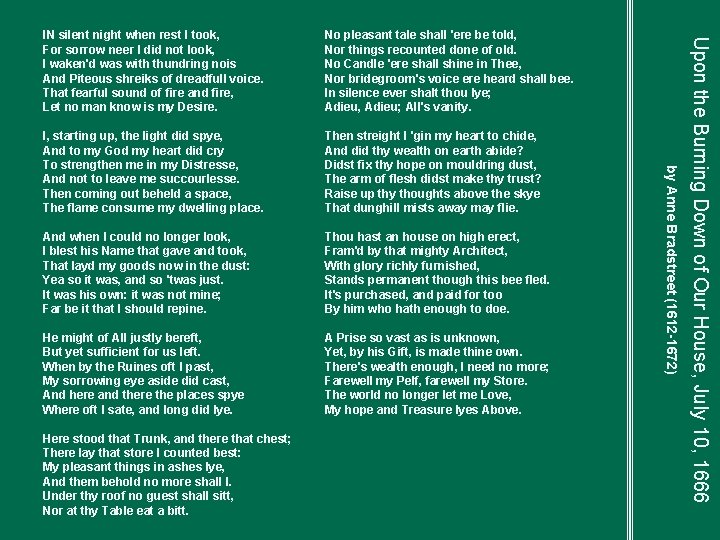

Then streight I 'gin my heart to chide, And did thy wealth on earth abide? Didst fix thy hope on mouldring dust, The arm of flesh didst make thy trust? Raise up thy thoughts above the skye That dunghill mists away may flie. Thou hast an house on high erect, Fram'd by that mighty Architect, With glory richly furnished, Stands permanent though this bee fled. It's purchased, and paid for too By him who hath enough to doe. A Prise so vast as is unknown, Yet, by his Gift, is made thine own. There's wealth enough, I need no more; Farewell my Pelf, farewell my Store. The world no longer let me Love, My hope and Treasure lyes Above. Upon the Burning Down of Our House, July 10, 1666 No pleasant tale shall 'ere be told, Nor things recounted done of old. No Candle 'ere shall shine in Thee, Nor bridegroom's voice ere heard shall bee. In silence ever shalt thou lye; Adieu, Adieu; All's vanity. by Anne Bradstreet (1612 -1672) IN silent night when rest I took, For sorrow neer I did not look, I waken'd was with thundring nois And Piteous shreiks of dreadfull voice. That fearful sound of fire and fire, Let no man know is my Desire. I, starting up, the light did spye, And to my God my heart did cry To strengthen me in my Distresse, And not to leave me succourlesse. Then coming out beheld a space, The flame consume my dwelling place. And when I could no longer look, I blest his Name that gave and took, That layd my goods now in the dust: Yea so it was, and so 'twas just. It was his own: it was not mine; Far be it that I should repine. He might of All justly bereft, But yet sufficient for us left. When by the Ruines oft I past, My sorrowing eye aside did cast, And here and there the places spye Where oft I sate, and long did lye. Here stood that Trunk, and there that chest; There lay that store I counted best: My pleasant things in ashes lye, And them behold no more shall I. Under thy roof no guest shall sitt, Nor at thy Table eat a bitt.

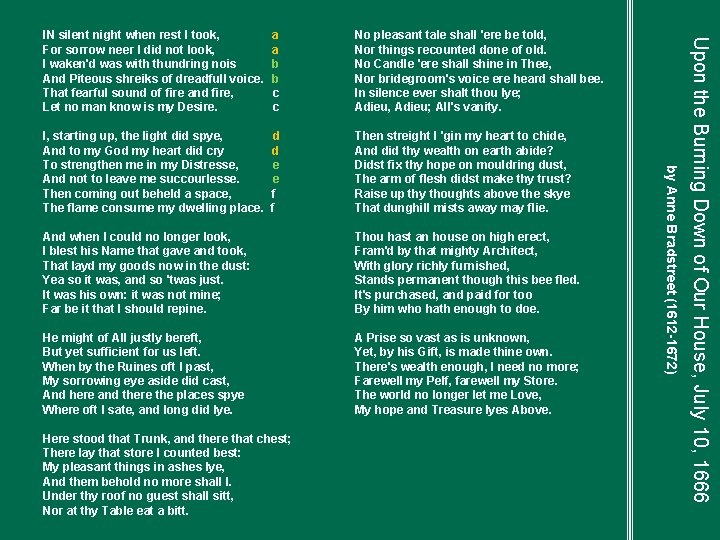

Then streight I 'gin my heart to chide, And did thy wealth on earth abide? Didst fix thy hope on mouldring dust, The arm of flesh didst make thy trust? Raise up thy thoughts above the skye That dunghill mists away may flie. Thou hast an house on high erect, Fram'd by that mighty Architect, With glory richly furnished, Stands permanent though this bee fled. It's purchased, and paid for too By him who hath enough to doe. A Prise so vast as is unknown, Yet, by his Gift, is made thine own. There's wealth enough, I need no more; Farewell my Pelf, farewell my Store. The world no longer let me Love, My hope and Treasure lyes Above. Upon the Burning Down of Our House, July 10, 1666 No pleasant tale shall 'ere be told, Nor things recounted done of old. No Candle 'ere shall shine in Thee, Nor bridegroom's voice ere heard shall bee. In silence ever shalt thou lye; Adieu, Adieu; All's vanity. by Anne Bradstreet (1612 -1672) IN silent night when rest I took, a For sorrow neer I did not look, a I waken'd was with thundring nois b And Piteous shreiks of dreadfull voice. b That fearful sound of fire and fire, c Let no man know is my Desire. c I, starting up, the light did spye, d And to my God my heart did cry d To strengthen me in my Distresse, e And not to leave me succourlesse. e Then coming out beheld a space, f The flame consume my dwelling place. f And when I could no longer look, I blest his Name that gave and took, That layd my goods now in the dust: Yea so it was, and so 'twas just. It was his own: it was not mine; Far be it that I should repine. He might of All justly bereft, But yet sufficient for us left. When by the Ruines oft I past, My sorrowing eye aside did cast, And here and there the places spye Where oft I sate, and long did lye. Here stood that Trunk, and there that chest; There lay that store I counted best: My pleasant things in ashes lye, And them behold no more shall I. Under thy roof no guest shall sitt, Nor at thy Table eat a bitt.

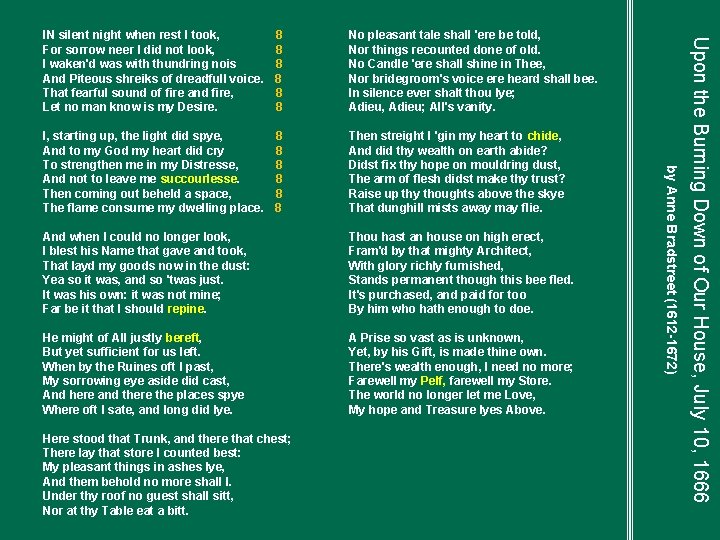

Then streight I 'gin my heart to chide, And did thy wealth on earth abide? Didst fix thy hope on mouldring dust, The arm of flesh didst make thy trust? Raise up thy thoughts above the skye That dunghill mists away may flie. Thou hast an house on high erect, Fram'd by that mighty Architect, With glory richly furnished, Stands permanent though this bee fled. It's purchased, and paid for too By him who hath enough to doe. A Prise so vast as is unknown, Yet, by his Gift, is made thine own. There's wealth enough, I need no more; Farewell my Pelf, farewell my Store. The world no longer let me Love, My hope and Treasure lyes Above. Upon the Burning Down of Our House, July 10, 1666 No pleasant tale shall 'ere be told, Nor things recounted done of old. No Candle 'ere shall shine in Thee, Nor bridegroom's voice ere heard shall bee. In silence ever shalt thou lye; Adieu, Adieu; All's vanity. by Anne Bradstreet (1612 -1672) IN silent night when rest I took, 8 For sorrow neer I did not look, 8 I waken'd was with thundring nois 8 And Piteous shreiks of dreadfull voice. 8 That fearful sound of fire and fire, 8 Let no man know is my Desire. 8 I, starting up, the light did spye, 8 And to my God my heart did cry 8 To strengthen me in my Distresse, 8 And not to leave me succourlesse. 8 Then coming out beheld a space, 8 The flame consume my dwelling place. 8 And when I could no longer look, I blest his Name that gave and took, That layd my goods now in the dust: Yea so it was, and so 'twas just. It was his own: it was not mine; Far be it that I should repine. He might of All justly bereft, But yet sufficient for us left. When by the Ruines oft I past, My sorrowing eye aside did cast, And here and there the places spye Where oft I sate, and long did lye. Here stood that Trunk, and there that chest; There lay that store I counted best: My pleasant things in ashes lye, And them behold no more shall I. Under thy roof no guest shall sitt, Nor at thy Table eat a bitt.

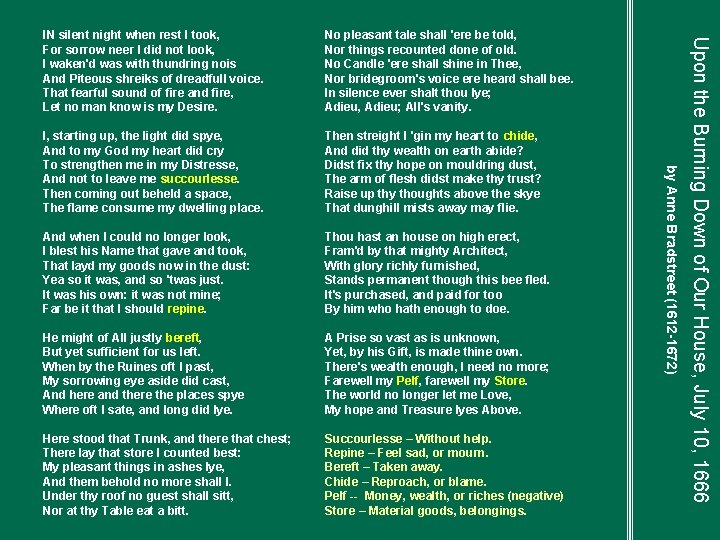

Then streight I 'gin my heart to chide, And did thy wealth on earth abide? Didst fix thy hope on mouldring dust, The arm of flesh didst make thy trust? Raise up thy thoughts above the skye That dunghill mists away may flie. Thou hast an house on high erect, Fram'd by that mighty Architect, With glory richly furnished, Stands permanent though this bee fled. It's purchased, and paid for too By him who hath enough to doe. A Prise so vast as is unknown, Yet, by his Gift, is made thine own. There's wealth enough, I need no more; Farewell my Pelf, farewell my Store. The world no longer let me Love, My hope and Treasure lyes Above. Succourlesse – Without help. Repine – Feel sad, or mourn. Bereft – Taken away. Chide – Reproach, or blame. Pelf -- Money, wealth, or riches (negative) Store – Material goods, belongings. Upon the Burning Down of Our House, July 10, 1666 No pleasant tale shall 'ere be told, Nor things recounted done of old. No Candle 'ere shall shine in Thee, Nor bridegroom's voice ere heard shall bee. In silence ever shalt thou lye; Adieu, Adieu; All's vanity. by Anne Bradstreet (1612 -1672) IN silent night when rest I took, For sorrow neer I did not look, I waken'd was with thundring nois And Piteous shreiks of dreadfull voice. That fearful sound of fire and fire, Let no man know is my Desire. I, starting up, the light did spye, And to my God my heart did cry To strengthen me in my Distresse, And not to leave me succourlesse. Then coming out beheld a space, The flame consume my dwelling place. And when I could no longer look, I blest his Name that gave and took, That layd my goods now in the dust: Yea so it was, and so 'twas just. It was his own: it was not mine; Far be it that I should repine. He might of All justly bereft, But yet sufficient for us left. When by the Ruines oft I past, My sorrowing eye aside did cast, And here and there the places spye Where oft I sate, and long did lye. Here stood that Trunk, and there that chest; There lay that store I counted best: My pleasant things in ashes lye, And them behold no more shall I. Under thy roof no guest shall sitt, Nor at thy Table eat a bitt.

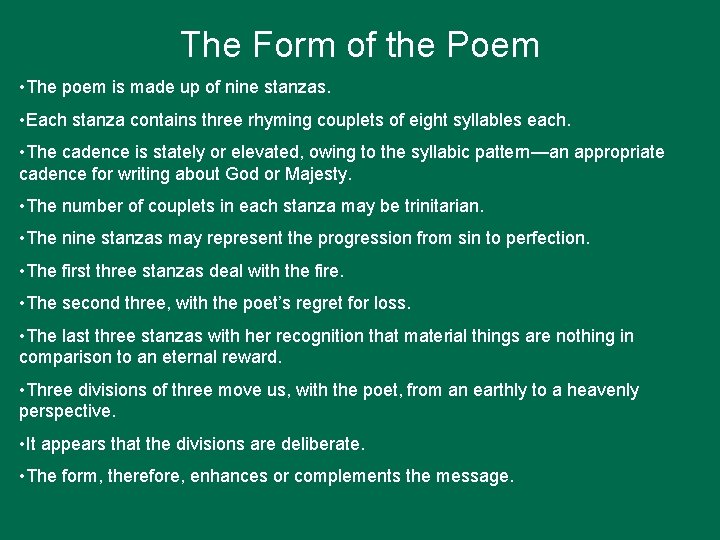

The Form of the Poem • The poem is made up of nine stanzas. • Each stanza contains three rhyming couplets of eight syllables each. • The cadence is stately or elevated, owing to the syllabic pattern—an appropriate cadence for writing about God or Majesty. • The number of couplets in each stanza may be trinitarian. • The nine stanzas may represent the progression from sin to perfection. • The first three stanzas deal with the fire. • The second three, with the poet’s regret for loss. • The last three stanzas with her recognition that material things are nothing in comparison to an eternal reward. • Three divisions of three move us, with the poet, from an earthly to a heavenly perspective. • It appears that the divisions are deliberate. • The form, therefore, enhances or complements the message.

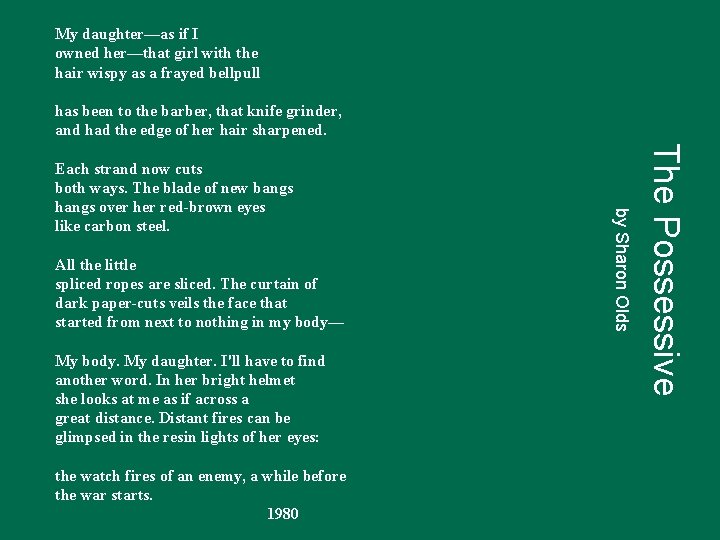

The Possessive by Sharon Olds My daughter—as if I owned her—that girl with the hair wispy as a frayed bellpull has been to the barber, that knife grinder, and had the edge of her hair sharpened. Each strand now cuts both ways. The blade of new bangs hangs over her red-brown eyes like carbon steel. All the little spliced ropes are sliced. The curtain of dark paper-cuts veils the face that started from next to nothing in my body— My body. My daughter. I'll have to find another word. In her bright helmet she looks at me as if across a great distance. Distant fires can be glimpsed in the resin lights of her eyes: the watch fires of an enemy, a while before the war starts. 1980

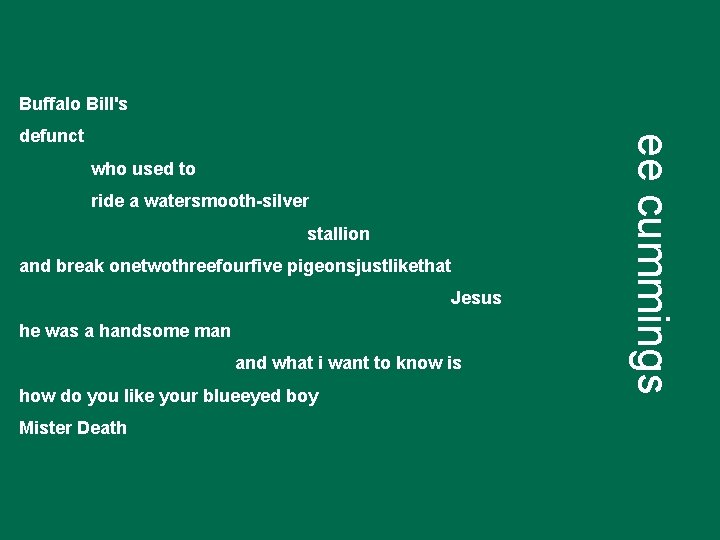

Buffalo Bill's who used to ride a watersmooth-silver stallion ee cummings defunct and break onetwothreefourfive pigeonsjustlikethat Jesus he was a handsome man and what i want to know is how do you like your blueeyed boy Mister Death

Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments; love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove. O no, it is an ever-fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wand'ring bark, Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle's compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

The whiskey on your breath Could make a small boy dizzy; But I hung on like death: Such waltzing was not easy. We romped until the pans Slid from the kitchen shelf; My mother's countenance Could not unfrown itself. The hand that held my wrist Was battered on one knuckle; At every step you missed My right ear scraped a buckle. You beat time on my head With a palm caked hard by dirt, Then waltzed me off to bed Still clinging to your shirt. Theodore Roethke (1942) My Papa's Waltz

Freethinking Mystic by Paul David Bond. Power. Point Presentation by Mark A. Spalding, BA, MEd, MA (2004). The End