Analyzing a Performance Some tips on what to

- Slides: 77

Analyzing a Performance Some tips on what to do before, during, and after reading poetry in public. Daniel Nester, The College of Saint Rose, 2006 -2011

Disclaimer This is not a comprehensive introduction to the reading or performance of a poem, nor is it necessarily an objective one. There are many ways to perform a poem, but some of the basics of reading poems need to be established before we can move on.

Adapted from the following: “Elements of Poetry. ” New York: Bedford St. Martins. 1 February 2008 <http: //bcs. bedfordstmartins. com/virtualit/poetry/elements. html>. Gura, Timothy, and Charlotte Lee. Oral Interpretation. 11 th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. Smith, Mark Kelly, and Joe Kraynak. The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Slam Poetry. 1 st ed. New York: Alpha Books, 2004. Turco, Lewis. The Handbook of Forms: A Handbook of Poetics. Hanover, NH: University Press of New Engliand, 2000.

Before your reading Did you rehearse? Did you read the poem?

A poem doesn’t live in a vacuum. As valuable as it might seem to look at the poem as a stand-alone text or to consider a poem as entirely open to interpretation to the reader, it helps more often than not to find out aspects of the poem. • Who is the poet? • Where does this poem figure into the poet’s work? • What do critics say about this poem or the poet’s work as a whole?

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the language of a poem is unfamiliar to you. Poems do that some time. We’ll get around to interpretation later, but first things first: • Look up unfamiliar words in dictionary, for meaning and pronunciation. • Are there allusions in the poem that you need to look up? • Look at the poem on the page. Size it up. Look at the line length, the end of the lines, the way the stanzas look. • Is the poem in a form? Does it rhyme? Is it in free verse?

Before your reading Did you step outside, pause, take a breath? Did you warm up?

Before your reading Did you understand the poem?

Before your reading Did you understand the poem? Denotative and connotative meanings?

Before your reading Denotative meanings: it means what it means. For example: The man drank whiskey quietly.

Before your reading Denotative meanings: it means what it means. The man drank whiskey quietly. The denotative meaning is simple: a guy drank whiskey and didn’t make much noise.

Before your reading For the connotative meanings, think about the emotional impact, the sounds, the associations you have with the words: The man drank whiskey quietly.

Before your reading For the connotative meanings, think about the emotional impact, the sounds, the associations you have with the words: The man drank whiskey quietly. Drinking is fun, right? It’s at parties, usually.

Before your reading For the connotative meanings, think about the emotional impact, the sounds, the associations you have with the words: The man drank whiskey quietly. The word “quietly, ” with the idea of booze, makes you think the man is alone. True?

Before your reading For the connotative meanings, think about the emotional impact, the sounds, the associations you have with the words: The man drank whiskey quietly. This implied solitude intensifies the anonymity of “the man. ” Why not “Shawn”?

Before your reading For the connotative meanings, think about the emotional impact, the sounds, the associations you have with the words: The man drank whiskey quietly. And what about whiskey? What does it “connote”? That it’s not scotch, rum, Jello shots, Jägermeister?

Before your reading Can you pick up any alliteration?

Before your reading Alliteration: the initial sounds of a word, beginning either with a consonant or a vowel, are repeated in close succession.

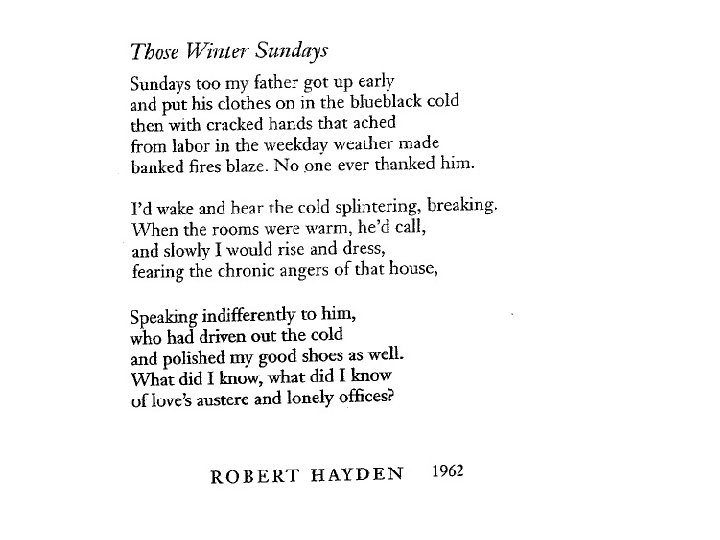

Before your reading Alliteration: the initial sounds of a word, beginning either with a consonant or a vowel, are repeated in close succession. Examples: banked fires blaze Nate never knows Peter Piper picked a peck of pickles

Before your reading Did you pick up any assonance?

Before your reading Assonance: the vowel sound(s) within a word that matches the same sound in a nearby word or words, but the surrounding consonant sounds are different.

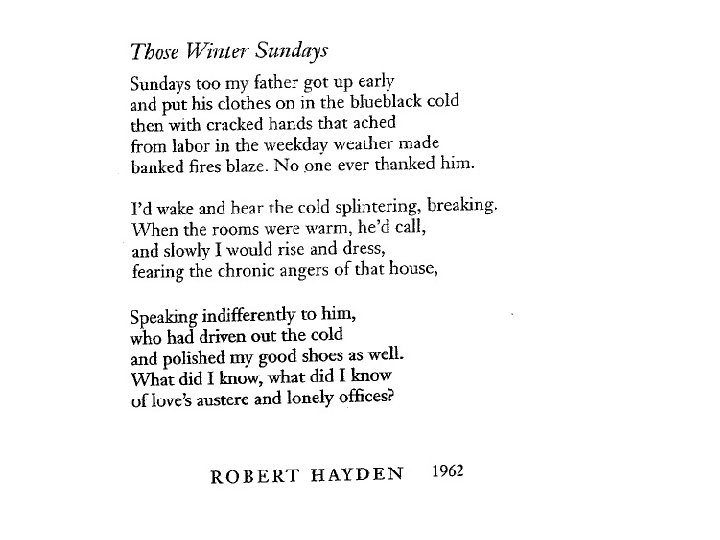

Before your reading Assonance: vowel sound within a word matches the same sound in a nearby word, but the surrounding consonant sounds are different. Examples: then with cracked hands that ached from labor in the weekday weather made banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

Before your reading Did you pick up any rhyme?

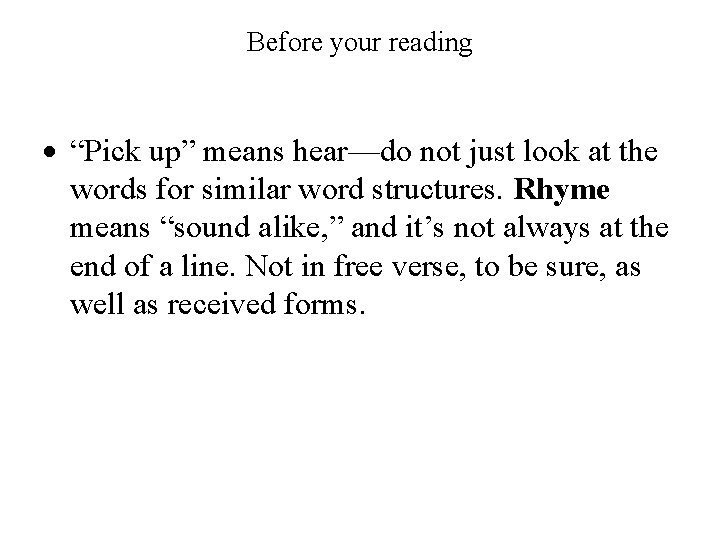

Before your reading “Pick up” means hear—do not just look at the words for similar word structures. Rhyme means “sound alike, ” and it’s not always at the end of a line. Not in free verse, to be sure, as well as received forms.

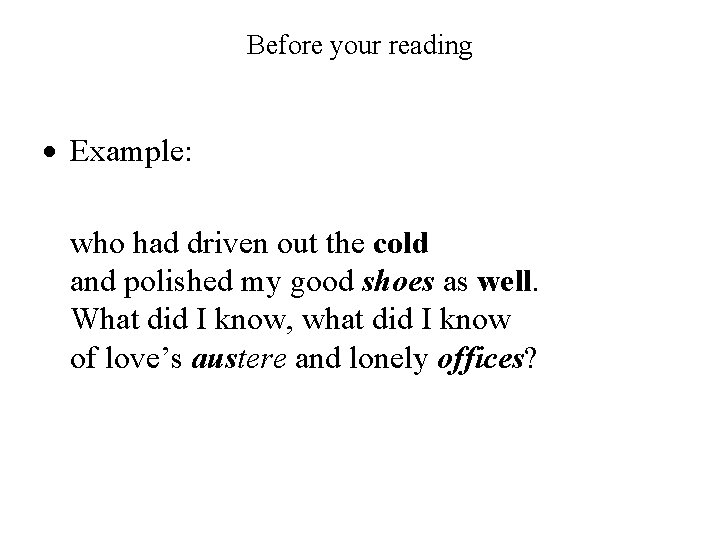

Before your reading Example: who had driven out the cold and polished my good shoes as well. What did I know, what did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices?

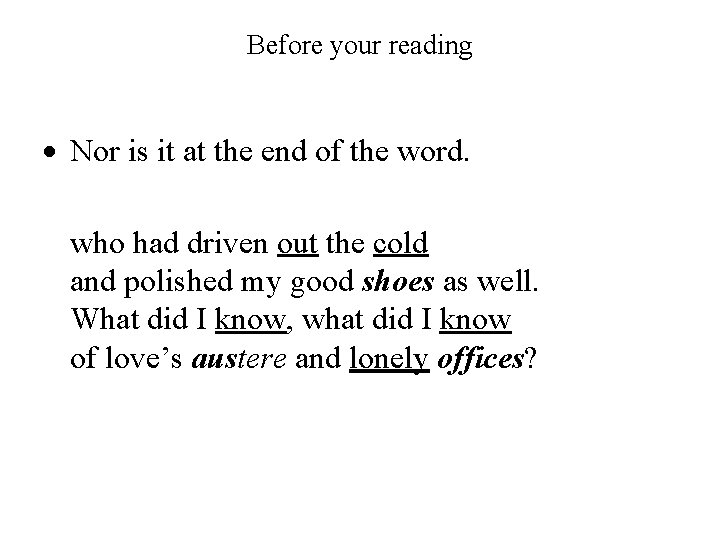

Before your reading Nor is it at the end of the word. who had driven out the cold and polished my good shoes as well. What did I know, what did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices?

Before your reading No sounds are random sounds in a poem.

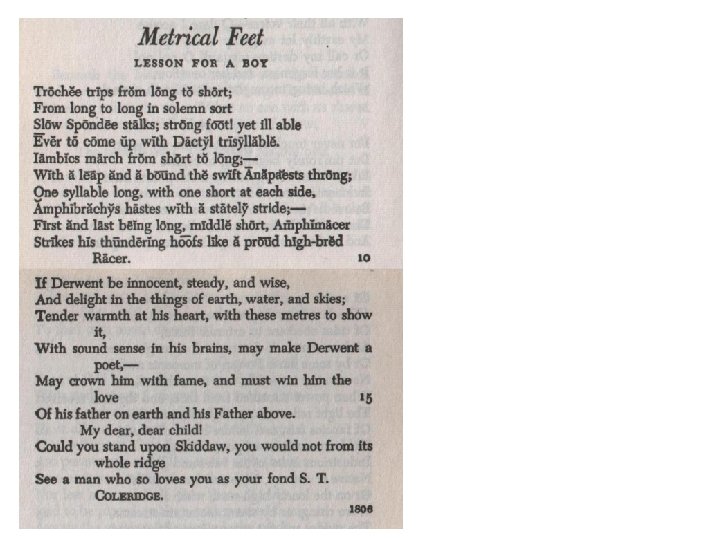

There are whole schools of thought that hold that no sound, rhythm, accent, syllable, or place on the page is random or is not thought-out or otherwise predestined in a poem.

This is what is called prosody, which is theories of the organizing principles of the composition and reading of poetry.

Prepare to be taken into the realm of prosody.

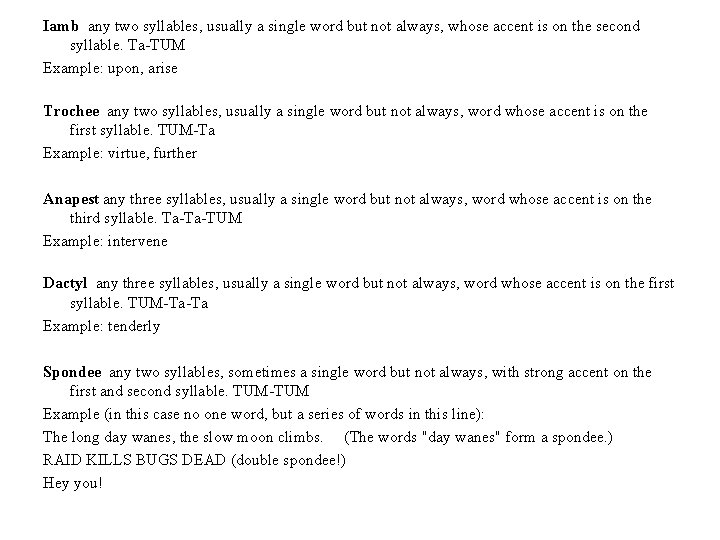

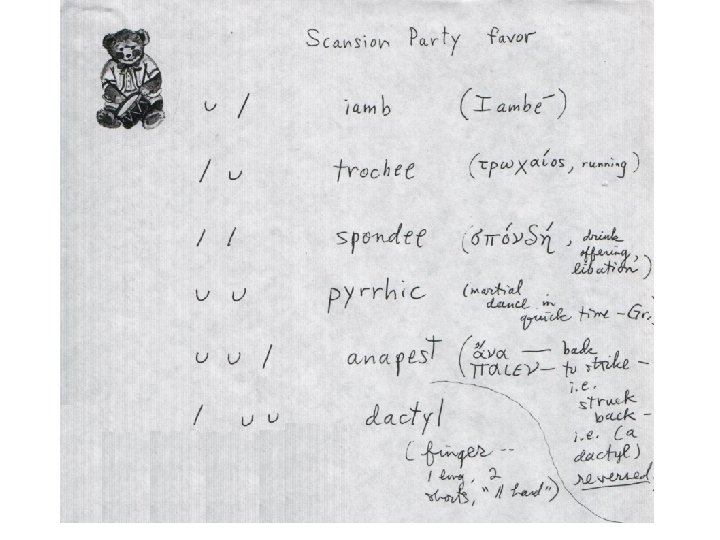

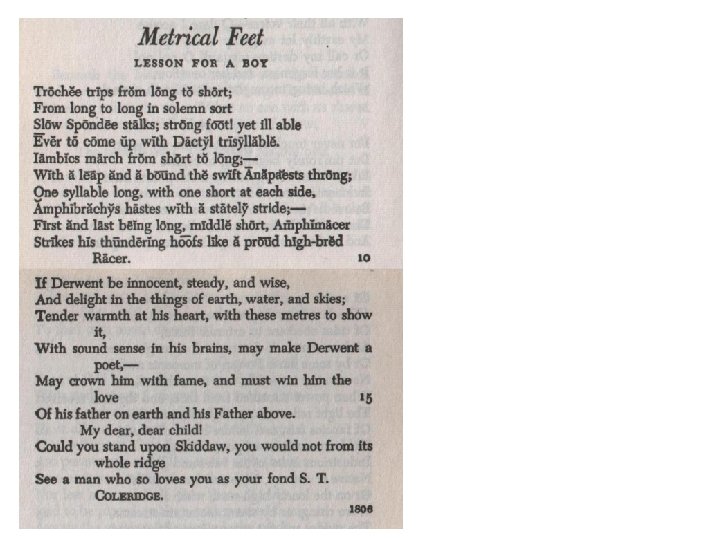

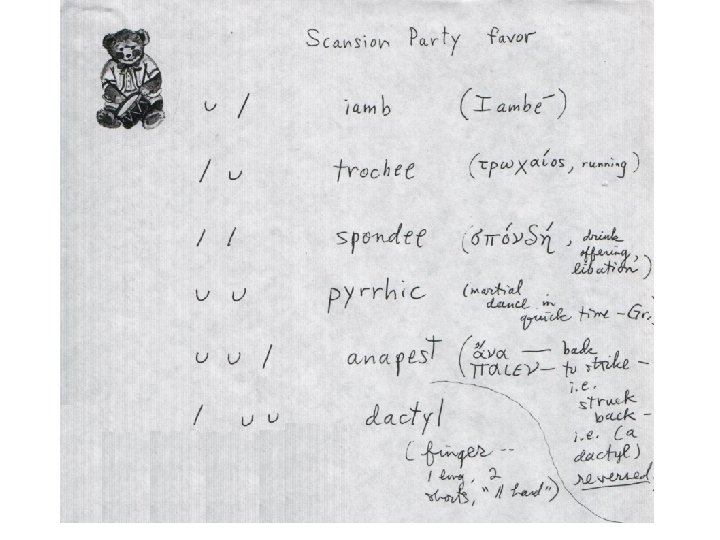

Iamb any two syllables, usually a single word but not always, whose accent is on the second syllable. Ta-TUM Example: upon, arise Trochee any two syllables, usually a single word but not always, word whose accent is on the first syllable. TUM-Ta Example: virtue, further Anapest any three syllables, usually a single word but not always, word whose accent is on the third syllable. Ta-Ta-TUM Example: intervene Dactyl any three syllables, usually a single word but not always, word whose accent is on the first syllable. TUM-Ta-Ta Example: tenderly Spondee any two syllables, sometimes a single word but not always, with strong accent on the first and second syllable. TUM-TUM Example (in this case no one word, but a series of words in this line): The long day wanes, the slow moon climbs. (The words "day wanes" form a spondee. ) RAID KILLS BUGS DEAD (double spondee!) Hey you!

To name the kind of foot, use the adjective form of these words. A line of iambs = iambic A line of trochees = trochaic A line of anapests = anapestic a line of dactyls = dactylic a line of spondees = spondaic

To name the kind of foot, use the adjective form of these words. A line of iambs = iambic A line of trochees = trochaic A line of anapests = anapestic a line of dactyls = dactylic a line of spondees = spondaic

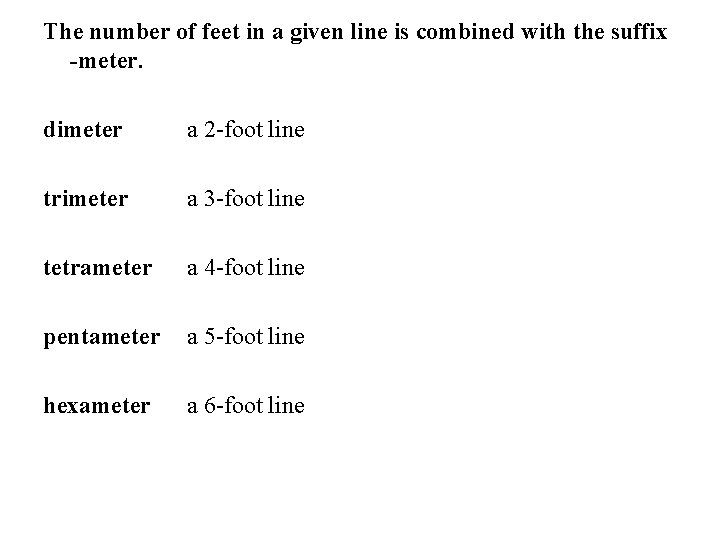

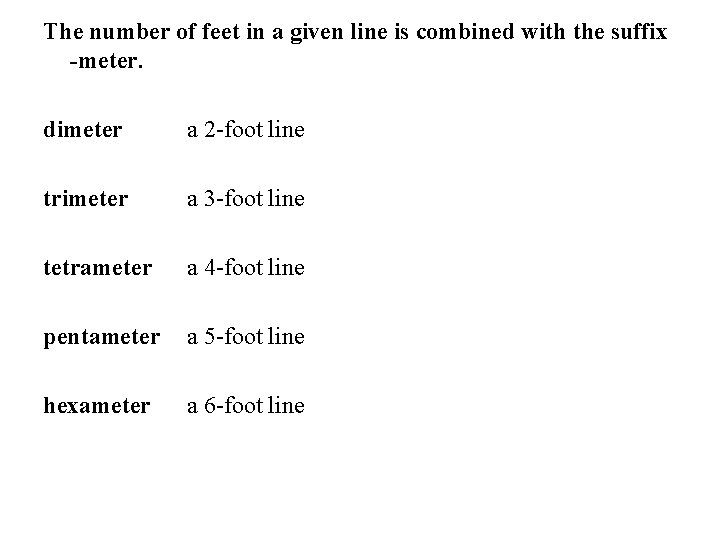

The number of feet in a given line is combined with the suffix -meter. dimeter a 2 -foot line trimeter a 3 -foot line tetrameter a 4 -foot line pentameter a 5 -foot line hexameter a 6 -foot line

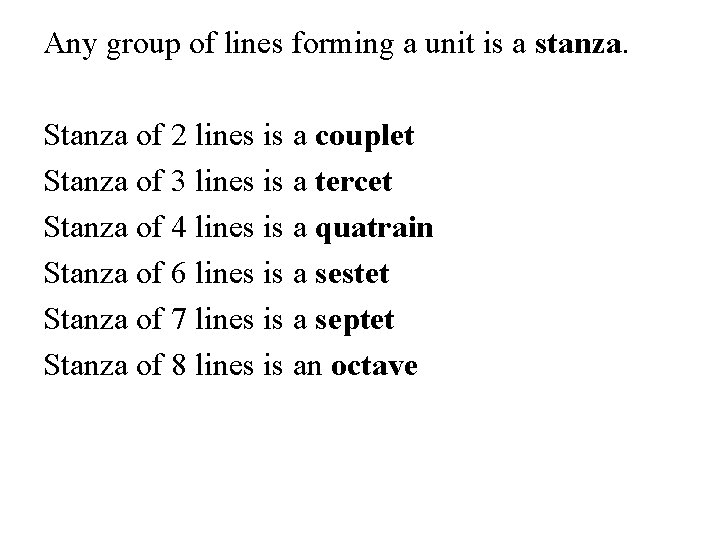

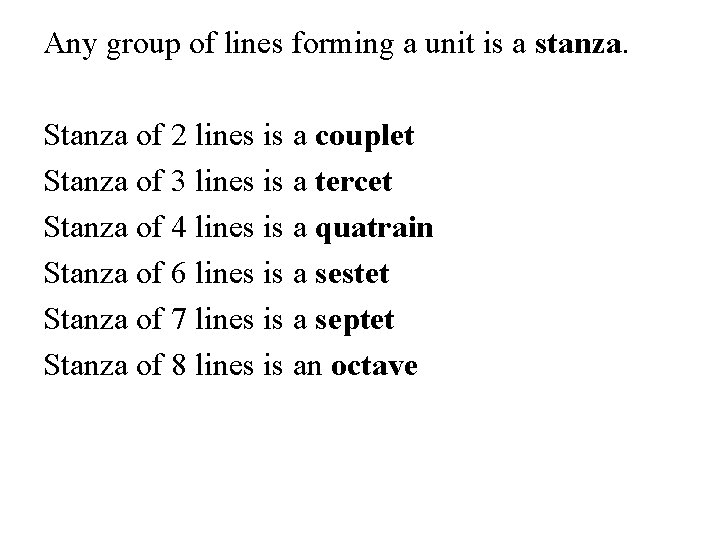

Any group of lines forming a unit is a stanza. Stanza of 2 lines is a couplet Stanza of 3 lines is a tercet Stanza of 4 lines is a quatrain Stanza of 6 lines is a sestet Stanza of 7 lines is a septet Stanza of 8 lines is an octave

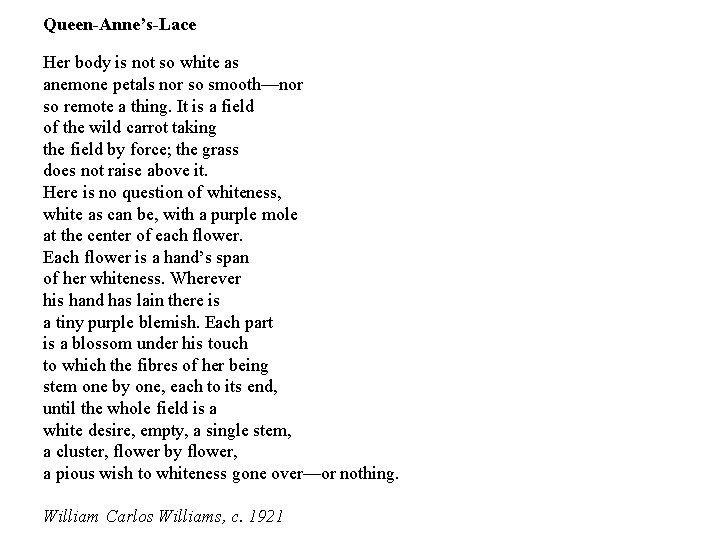

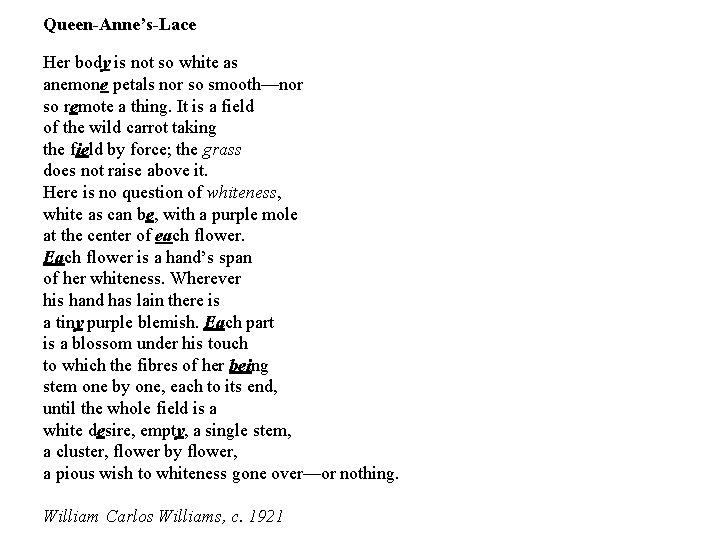

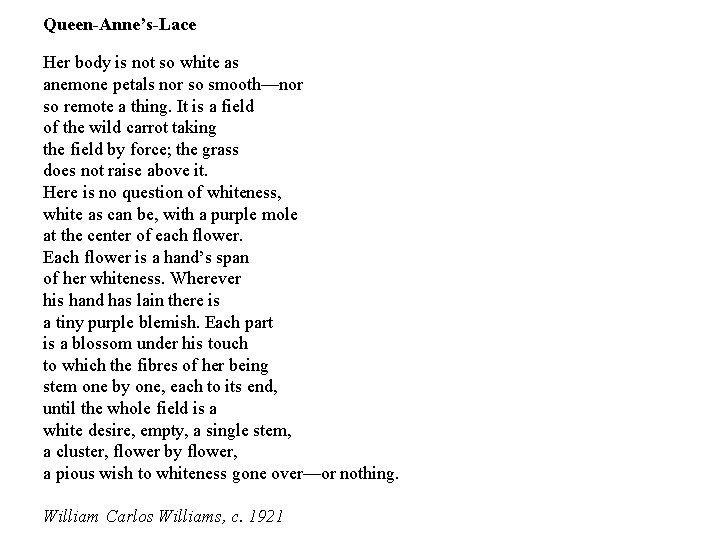

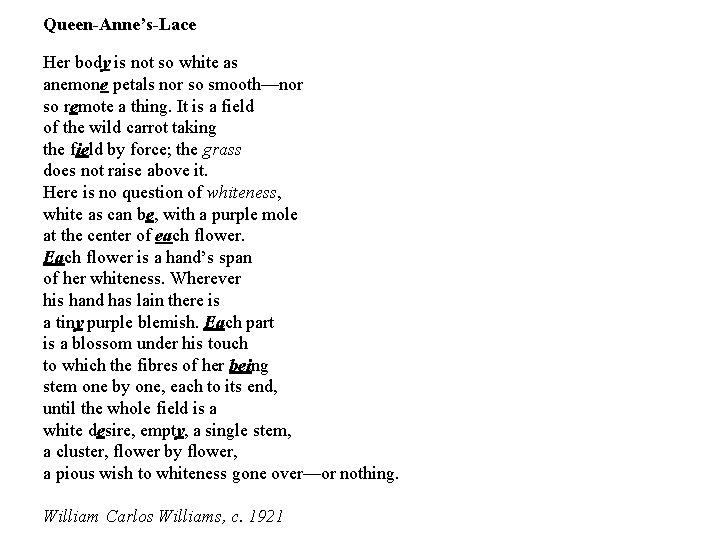

Queen-Anne’s-Lace Her body is not so white as anemone petals nor so smooth—nor so remote a thing. It is a field of the wild carrot taking the field by force; the grass does not raise above it. Here is no question of whiteness, white as can be, with a purple mole at the center of each flower. Each flower is a hand’s span of her whiteness. Wherever his hand has lain there is a tiny purple blemish. Each part is a blossom under his touch to which the fibres of her being stem one by one, each to its end, until the whole field is a white desire, empty, a single stem, a cluster, flower by flower, a pious wish to whiteness gone over—or nothing. William Carlos Williams, c. 1921

Queen-Anne’s-Lace Her body is not so white as anemone petals nor so smooth—nor so remote a thing. It is a field of the wild carrot taking the field by force; the grass does not raise above it. Here is no question of whiteness, white as can be, with a purple mole at the center of each flower. Each flower is a hand’s span of her whiteness. Wherever his hand has lain there is a tiny purple blemish. Each part is a blossom under his touch to which the fibres of her being stem one by one, each to its end, until the whole field is a white desire, empty, a single stem, a cluster, flower by flower, a pious wish to whiteness gone over—or nothing. William Carlos Williams, c. 1921

Before your reading No rhythm is random in a poem. Not even a random rhythm.

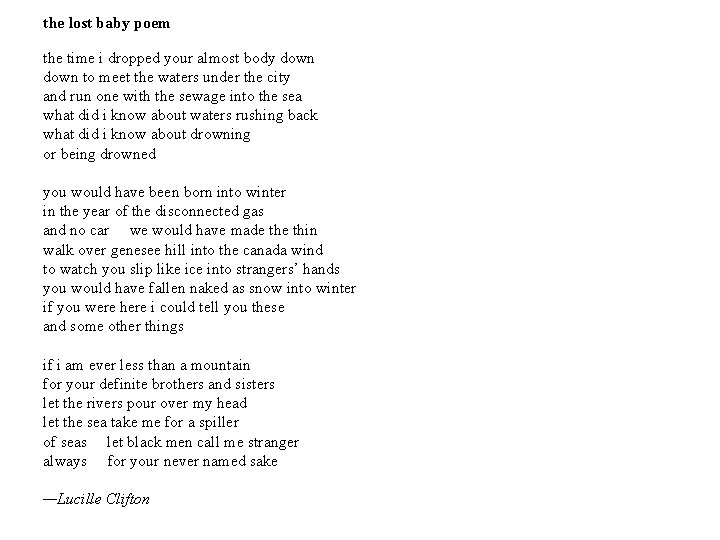

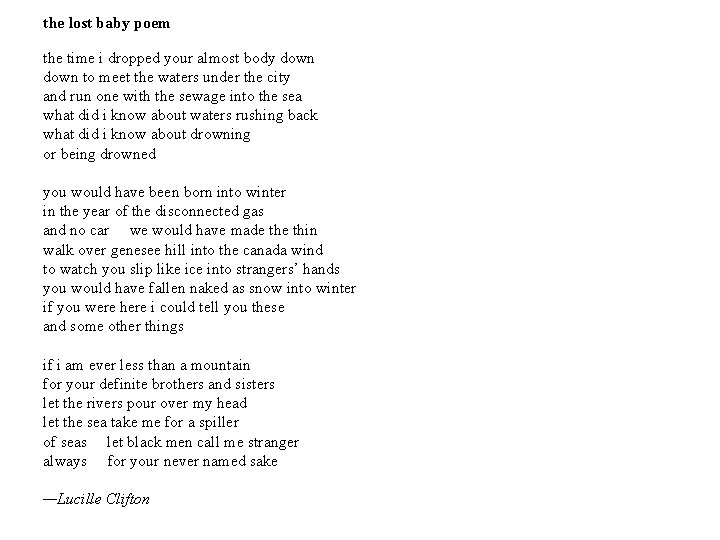

the lost baby poem the time i dropped your almost body down to meet the waters under the city and run one with the sewage into the sea what did i know about waters rushing back what did i know about drowning or being drowned you would have been born into winter in the year of the disconnected gas and no car we would have made thin walk over genesee hill into the canada wind to watch you slip like ice into strangers’ hands you would have fallen naked as snow into winter if you were here i could tell you these and some other things if i am ever less than a mountain for your definite brothers and sisters let the rivers pour over my head let the sea take me for a spiller of seas let black men call me stranger always for your never named sake —Lucille Clifton

A beautiful, sad poem, one that is not a received form (sonnet, terza rima, ballade, etc. ). But there are several things working inside this poem that affect how one reads it silently, and how one might perform it.

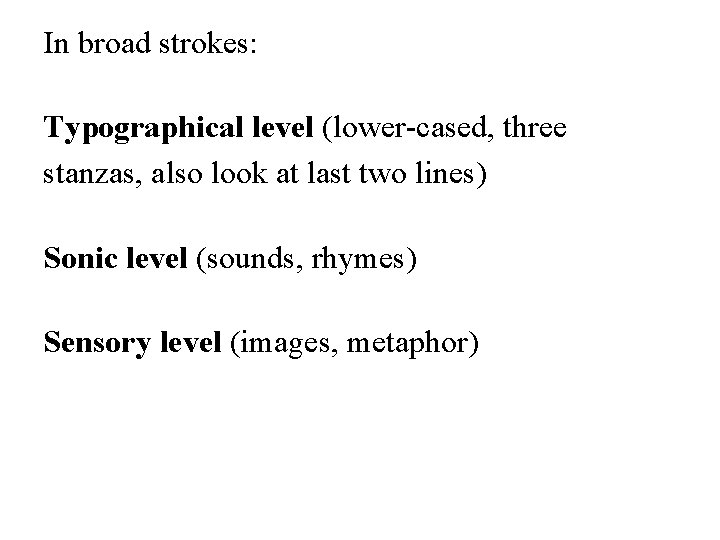

In broad strokes: Typographical level (lower-cased, three stanzas, also look at last two lines) Sonic level (sounds, rhymes) Sensory level (images, metaphor)

Typographical level In the Clifton poem, it’s lower-cased, three Stanzas. Also, look at last two lines and the third line in the second stanza. Those white spaces are meant to make the reader pause, however tentatively. This is just one example of a poet’s use of the “Field of composition, ” or “composition by field” (Duncan, Olson).

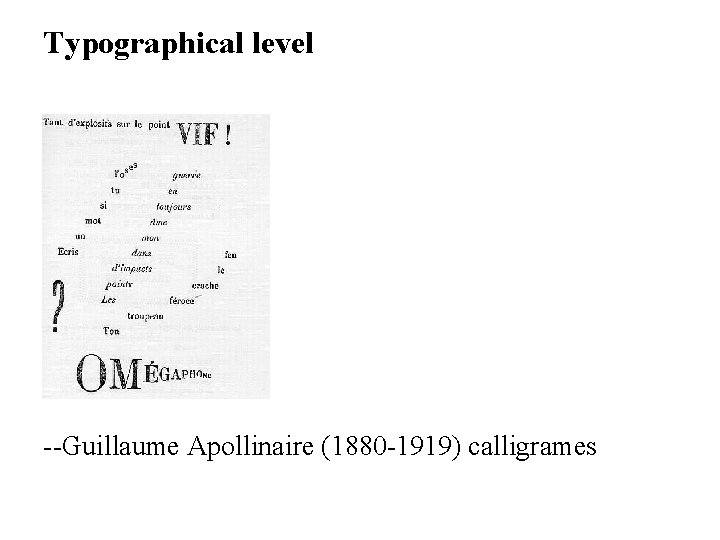

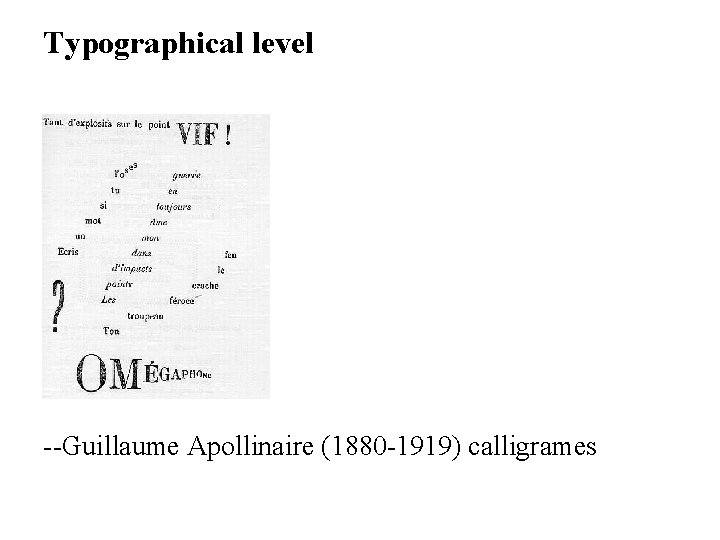

Typographical level M --Guillaume Apollinaire (1880 -1919) calligrames

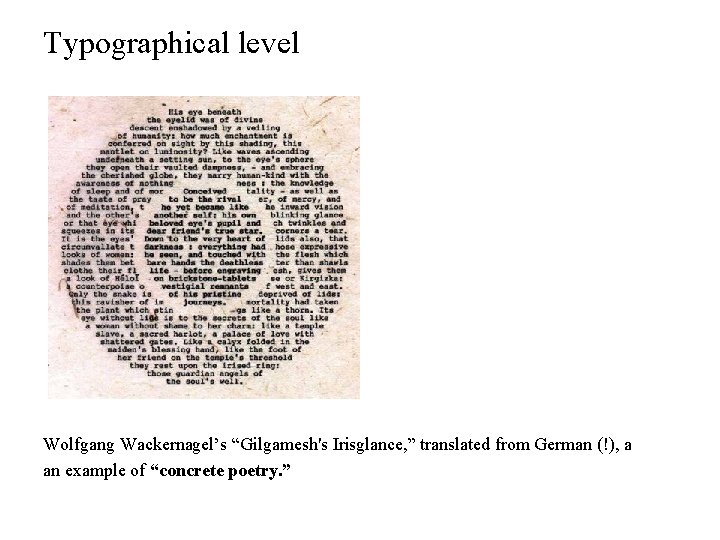

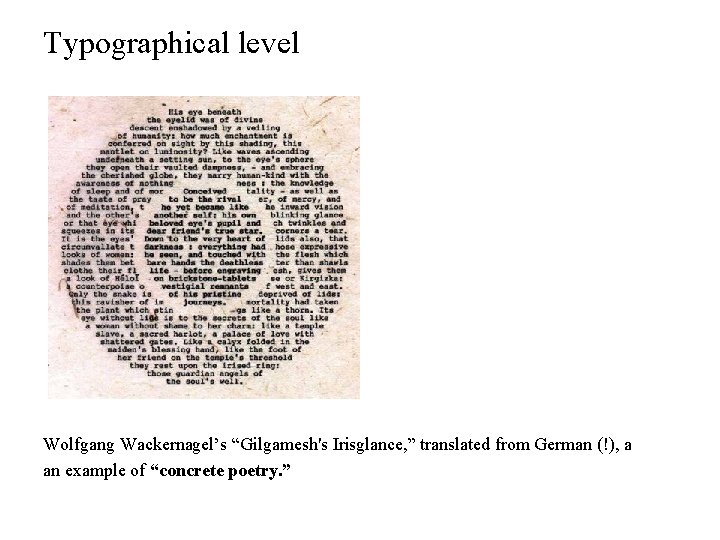

Typographical level Wolfgang Wackernagel’s “Gilgamesh's Irisglance, ” translated from German (!), a an example of “concrete poetry. ”

One of the major differences between poetry in prose is the breaking of the line, or line breaks. One of the major hurtles for the reader of poetry, especially free verse, is reading poems that make use of enjambment, which is the breaking of syntactic units (phrase, sentence) from line to line. Not all lines will terminate, or appear endstopped, with the end of a syntactic unit.

Sonic level (sounds, rhymes, we went over that).

Sense level. Image x, the cross-lined letter Metaphor x is y Simile x is like y Motif x 1, x 2, x 3 Allegory x = y(x) Theme a+b+c = x Puns x = ecks, ex. Allusions x = the unknown variable Ambiguity x ≈ y

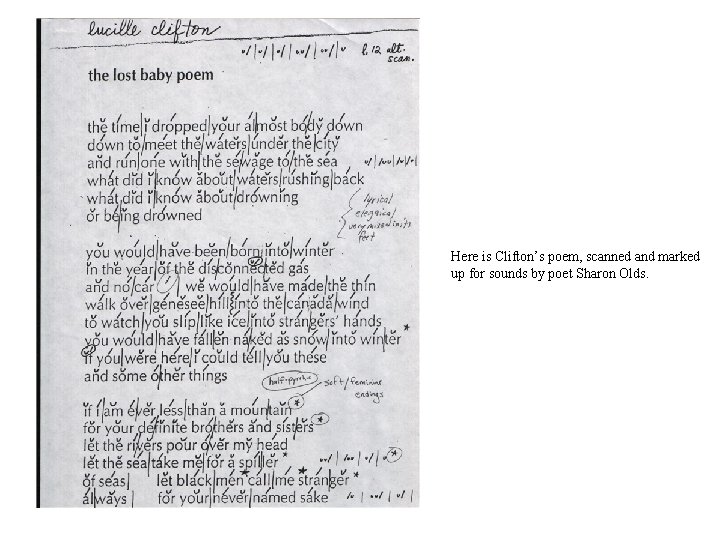

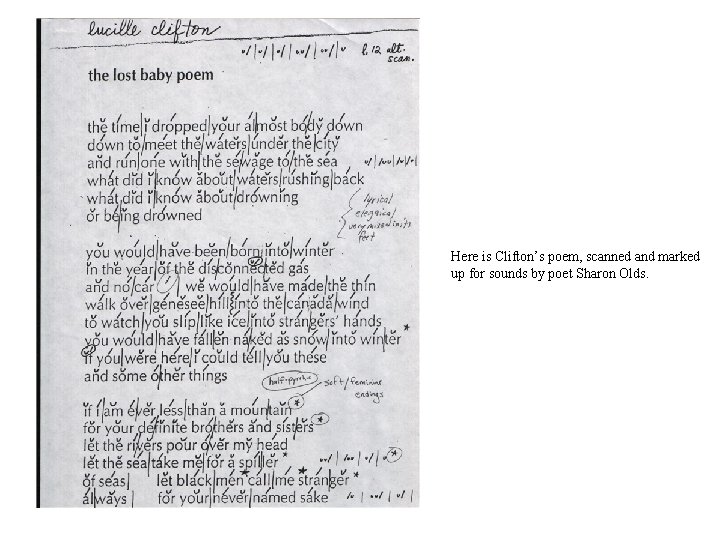

Here is Clifton’s poem, scanned and marked up for sounds by poet Sharon Olds.

Before your reading Can you envision the persona of the speaker?

Before your reading What’s the tone of the poem?

Before your reading Who is the speaker?

Before your reading Where are you reading? Are people listening? How loud can you or should you be?

Before your reading Microphone check one-two: Did you check to see how loud it was?

Before your reading Did you have an introduction prepared?

Before your reading Did you have an introduction prepared? Did you set up the reading (e. g. , if the work is excerpted, is from another language, uses old or antiquated language)? If so, did it set up the reading well? Was it too long? Short?

During the reading

During Were you completely present, or in the moment, as you read and performed the poem?

During Did you maintain your persona’s presence? In acting, we might call not maintaining this presence “breaking character. ” This might be caused by anything from laughing at a line that is funny, being distracted by oneself or the audience, anything besides there is a call for a deliberate for the reader/performer to break the fourth wall.

During Did you keep your concentration?

During Did you look up from the page? In a class such as this, this is sort of the firstlevel of moving from reading at an audience to reading to, or for, an audience. There are several schools of thought in the “looking up” debate. I would say you should be familiar enough with your material that you should be able to look up and at your audience. Or at least move your eyes!

During Did you make eye contact with people?

During Did your concentration break? Where and when did it happen?

During Did you stumble over a word or words? Which words? How was your diction? Did it keep up with the poem’s sounds?

During Did you bear in mind the rhythm of the piece; that is, its meter and use of line breaks or enjambment?

During Did you present or perform a poem with its climax or crescendo or resolution? Or how about a volta, or turn? Keep in mind all poems do not climax or reach a crescendo, or even turn, but many of them do. It’s best to have realized this before performing the poem; to be sure, it’s a good measure if one understands the poem fully. (More about “understanding” a poem later. )

After your reading

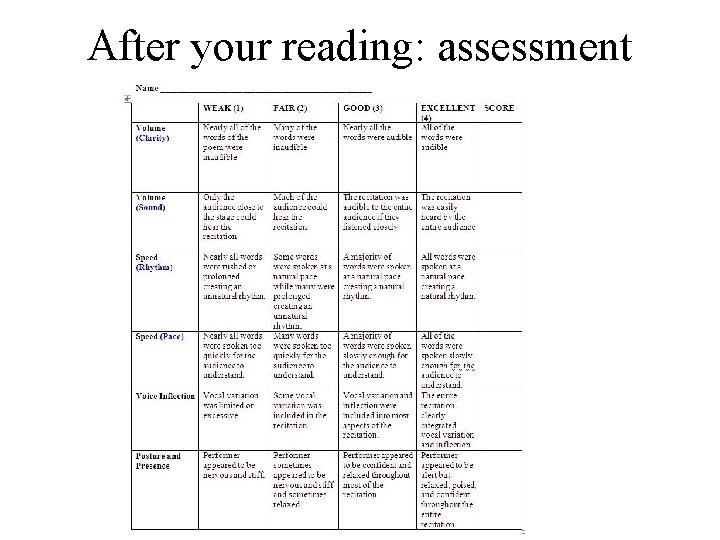

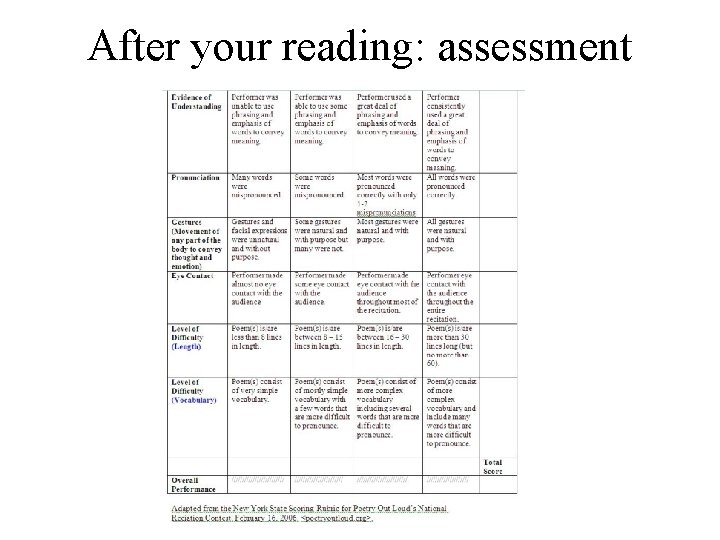

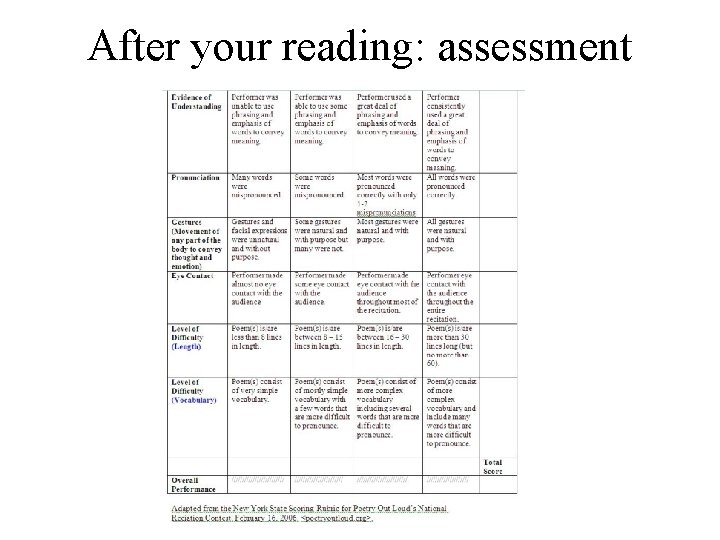

After your reading: assessment

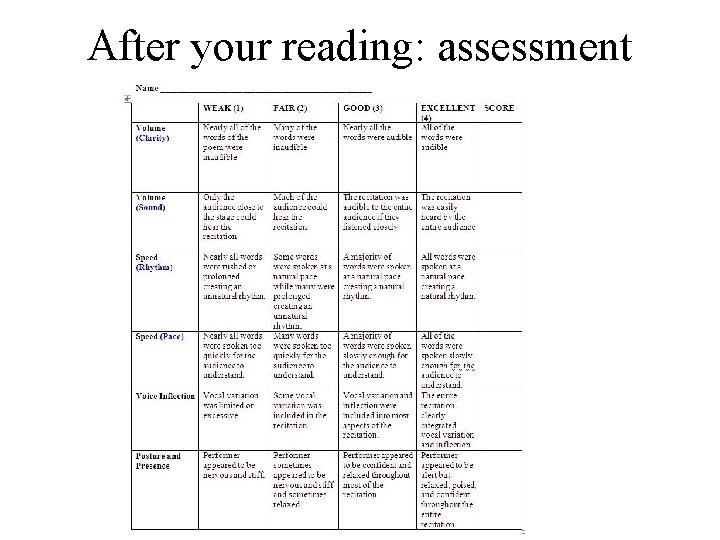

After your reading: assessment

After your reading: assessment

After your reading: assessment Did you present a climax or crescendo of the poem?

After your reading: assessment Did the audience respond to your reading?

After your reading: assessment Were you distracted by the audience’s reactions?

After your reading: assessment Intended effect? Stone-faced crowd? Did anyone laugh? If so, did you wait until you were done? How was your comic timing?

Adapted from the following: “Elements of Poetry. ” New York: Bedford St. Martins. 1 February 2008 <http: //bcs. bedfordstmartins. com/virtualit/poetry/elements. html>. Gura, Timothy, and Charlotte Lee. Oral Interpretation. 11 th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. Smith, Mark Kelly, and Joe Kraynak. The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Slam Poetry. 1 st ed. New York: Alpha Books, 2004. Turco, Lewis. The Handbook of Forms: A Handbook of Poetics. Hanover, NH: University Press of New Engliand, 2000.