Analysis of Elastic Strains Ref L D Landau

![Waves in the [100] direction → Longitudinal Transverse, degenerate Waves in the [100] direction → Longitudinal Transverse, degenerate](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/660768df84d58c570409fd8f6c31315c/image-10.jpg)

![Waves in the [110] direction → Lonitudinal Transverse Waves in the [110] direction → Lonitudinal Transverse](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/660768df84d58c570409fd8f6c31315c/image-11.jpg)

![Anisotropic Materials where [C] is the 6 x 6 stiffness matrix where [S] = Anisotropic Materials where [C] is the 6 x 6 stiffness matrix where [S] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/660768df84d58c570409fd8f6c31315c/image-34.jpg)

- Slides: 69

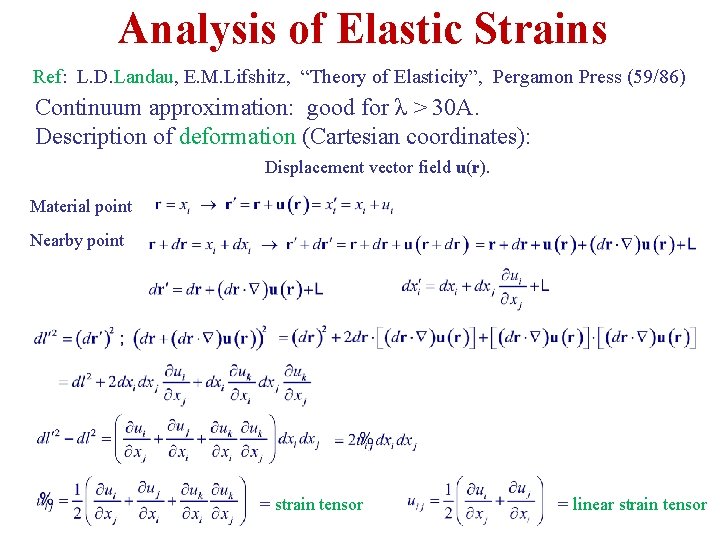

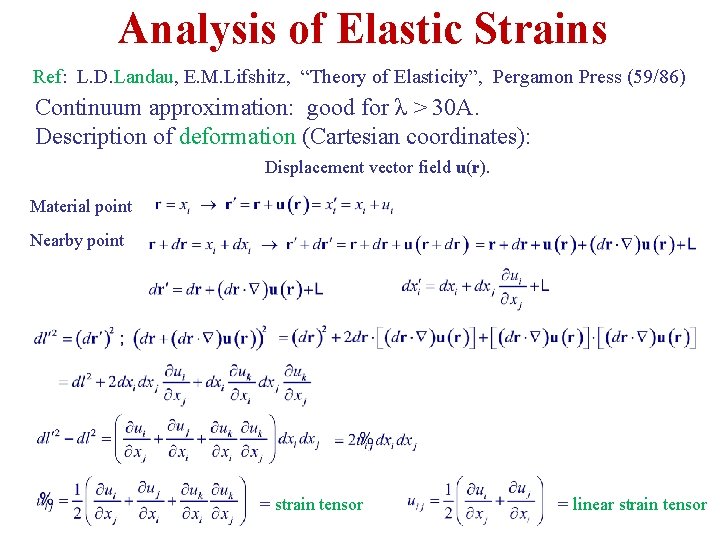

Analysis of Elastic Strains Ref: L. D. Landau, E. M. Lifshitz, “Theory of Elasticity”, Pergamon Press (59/86) Continuum approximation: good for λ > 30 A. Description of deformation (Cartesian coordinates): Displacement vector field u(r). Material point Nearby point = strain tensor = linear strain tensor

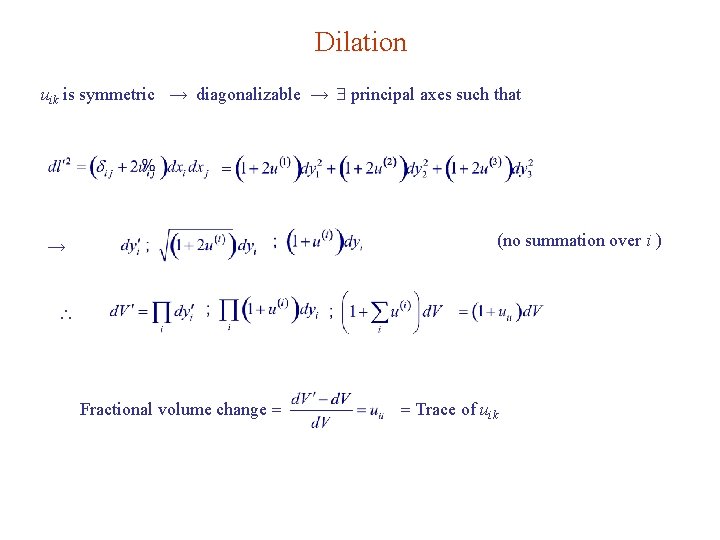

Dilation uik is symmetric → diagonalizable → principal axes such that (no summation over i ) → Fractional volume change Trace of uik

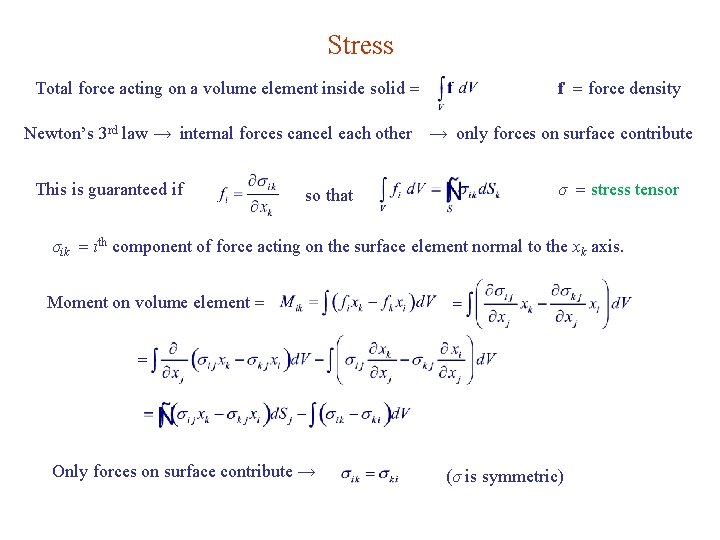

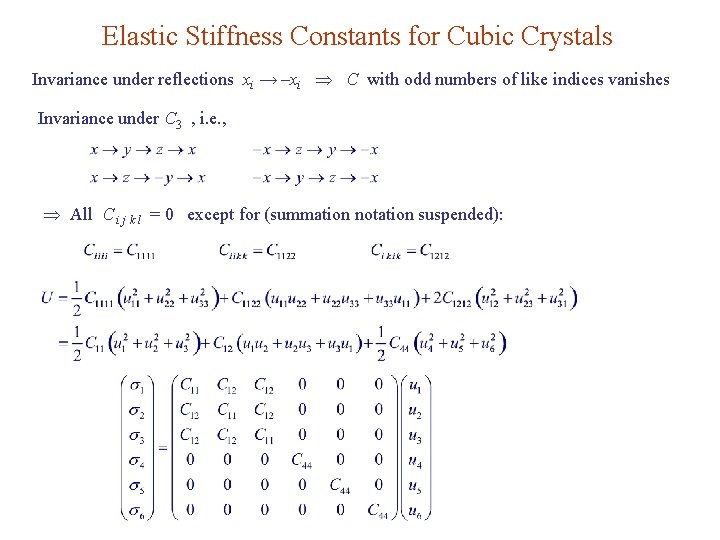

Stress Total force acting on a volume element inside solid f force density Newton’s 3 rd law → internal forces cancel each other → only forces on surface contribute This is guaranteed if so that σ stress tensor σik ith component of force acting on the surface element normal to the xk axis. Moment on volume element Only forces on surface contribute → (σ is symmetric)

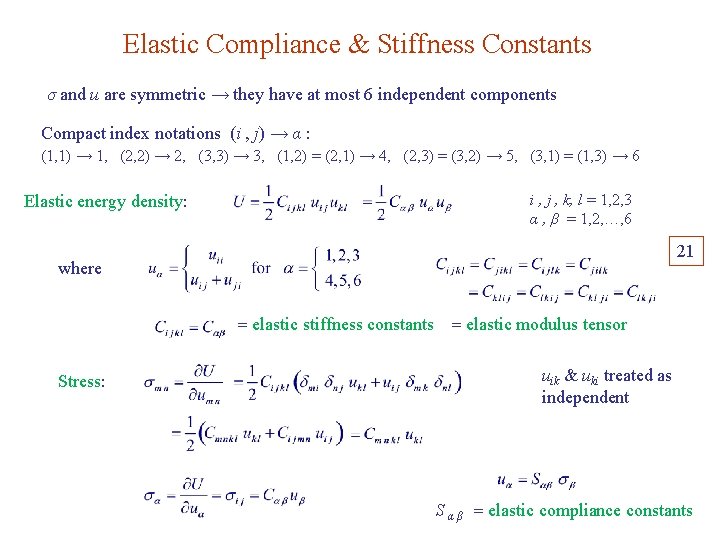

Elastic Compliance & Stiffness Constants σ and u are symmetric → they have at most 6 independent components Compact index notations (i , j) → α : (1, 1) → 1, (2, 2) → 2, (3, 3) → 3, (1, 2) = (2, 1) → 4, (2, 3) = (3, 2) → 5, (3, 1) = (1, 3) → 6 Elastic energy density: i , j , k, l = 1, 2, 3 α , β = 1, 2, …, 6 21 where elastic stiffness constants elastic modulus tensor Stress: uik & uki treated as independent S α β elastic compliance constants

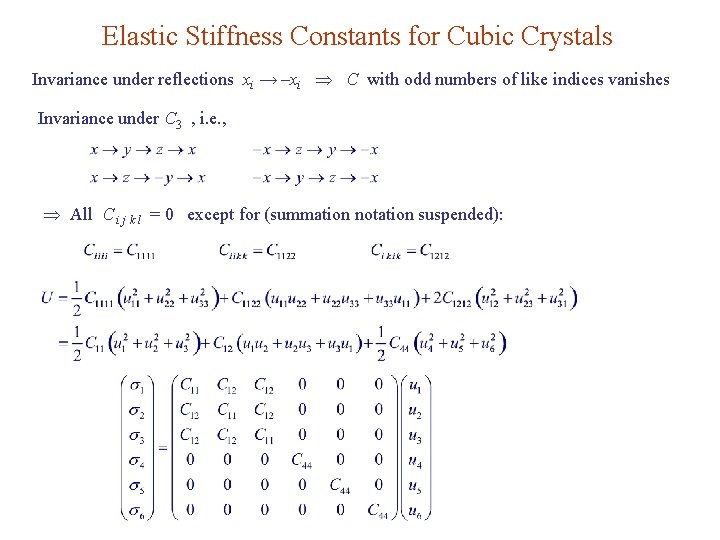

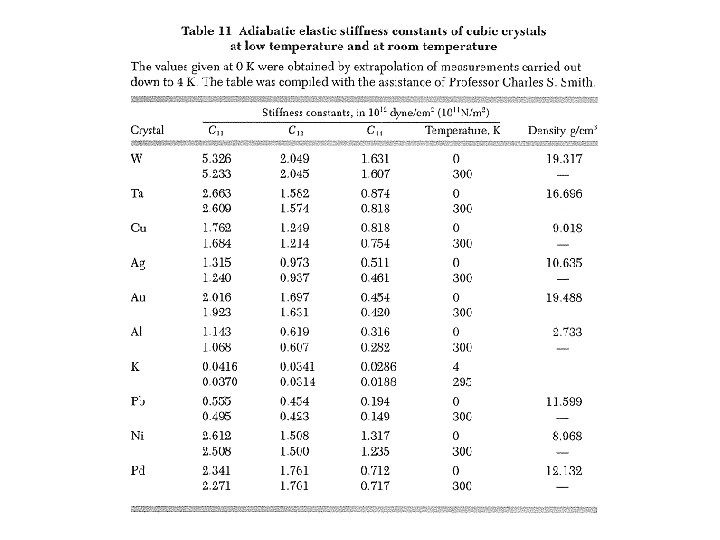

Elastic Stiffness Constants for Cubic Crystals Invariance under reflections xi → –xi C with odd numbers of like indices vanishes Invariance under C 3 , i. e. , All C i j k l = 0 except for (summation notation suspended):

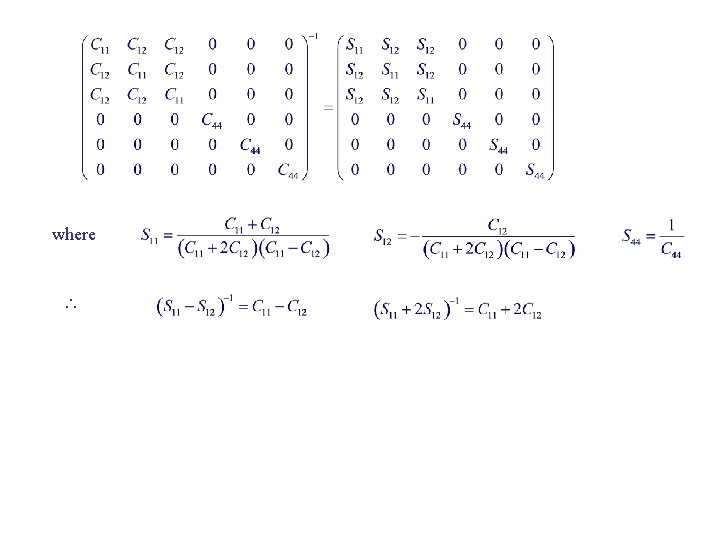

where

Bulk Modulus & Compressibility Uniform dilation: δ = Tr uik = fractional volume change B = Bulk modulus = 1/κ See table 3 for values of B & κ. κ = compressibility

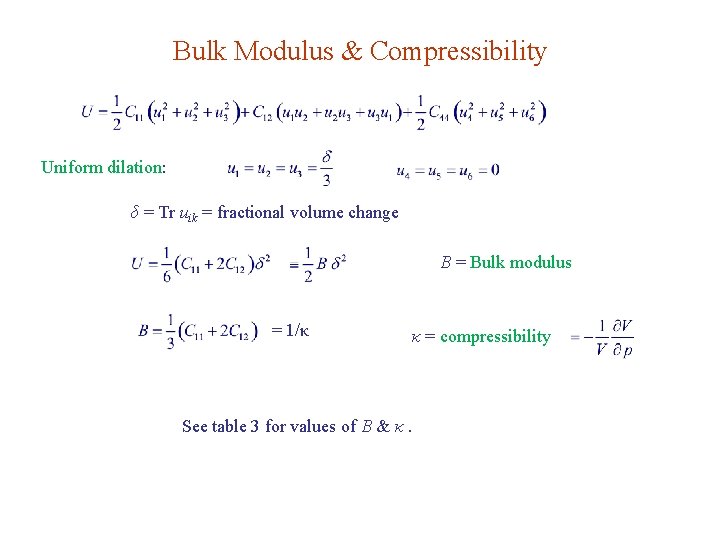

Elastic Waves in Cubic Crystals Newton’s 2 nd law: don’t confuse ui with uα → Similarly

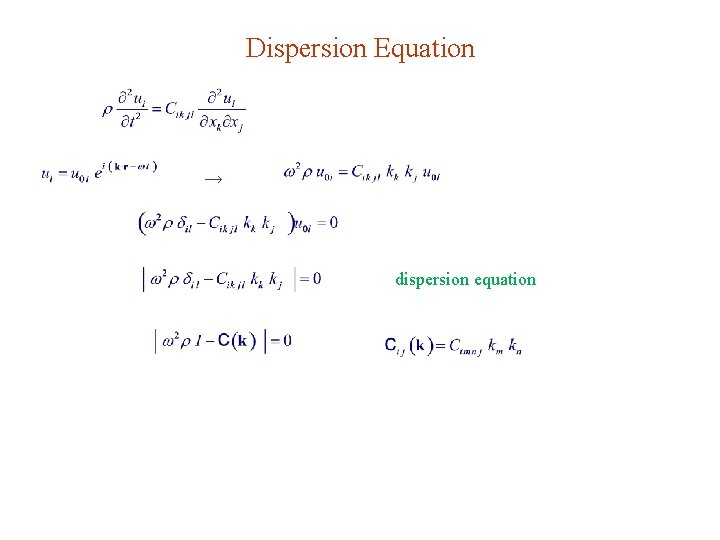

Dispersion Equation → dispersion equation

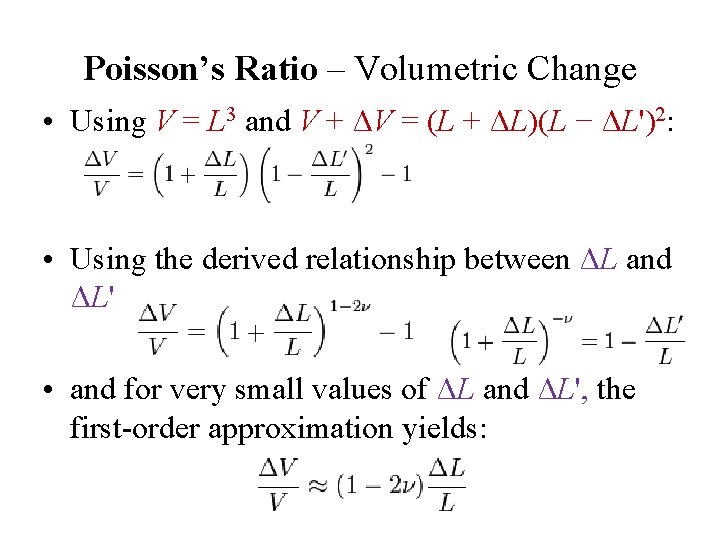

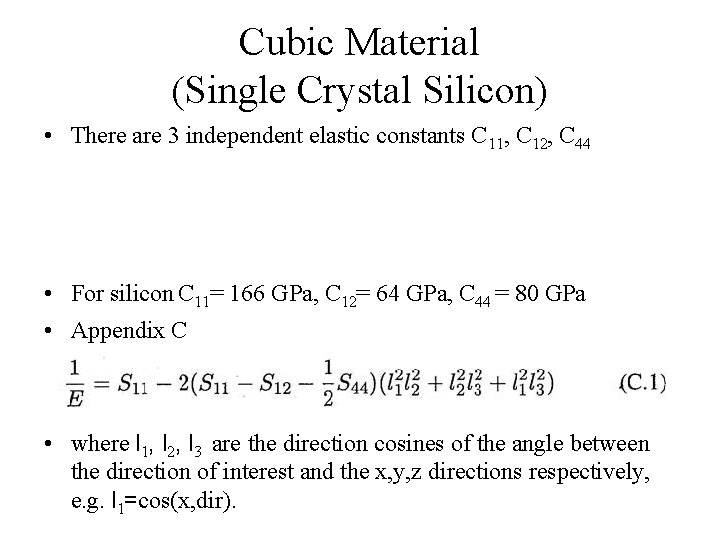

![Waves in the 100 direction Longitudinal Transverse degenerate Waves in the [100] direction → Longitudinal Transverse, degenerate](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/660768df84d58c570409fd8f6c31315c/image-10.jpg)

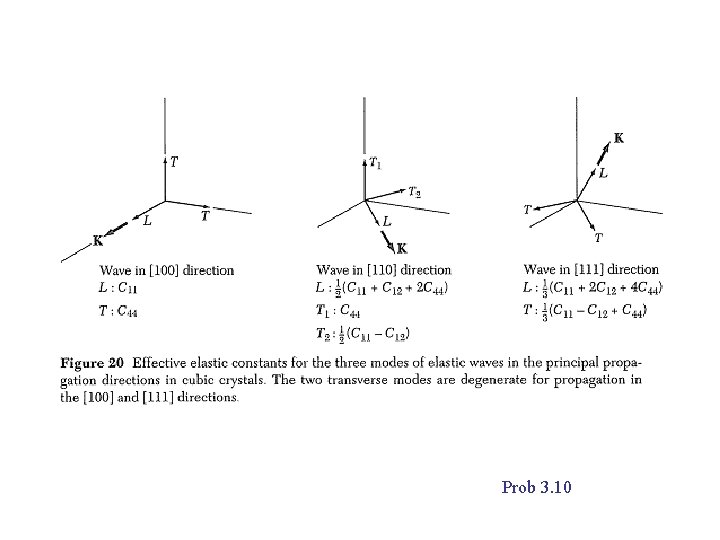

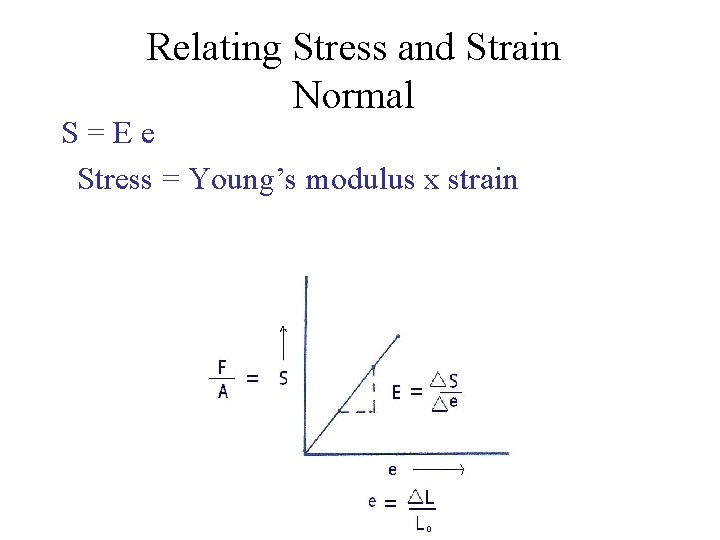

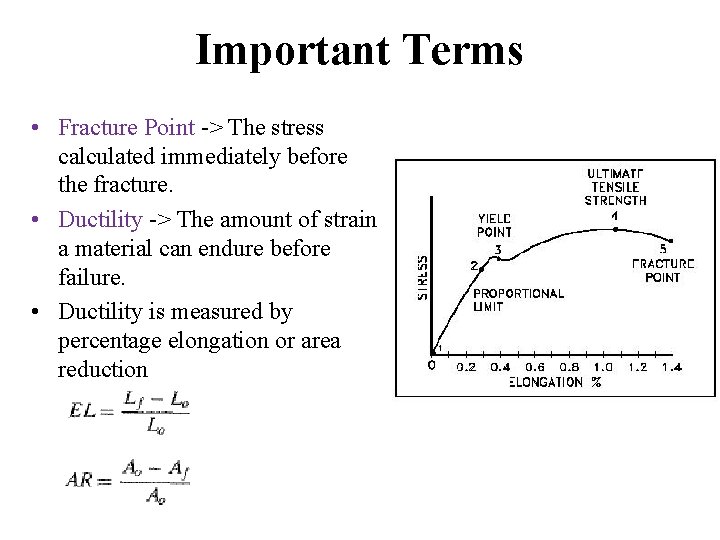

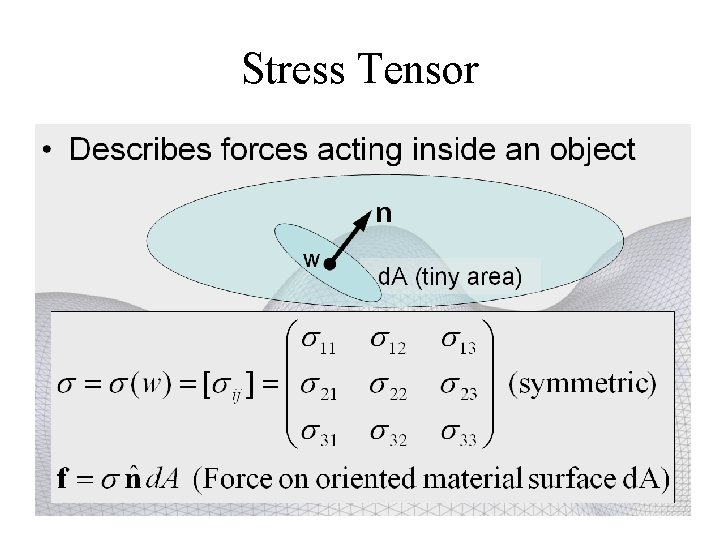

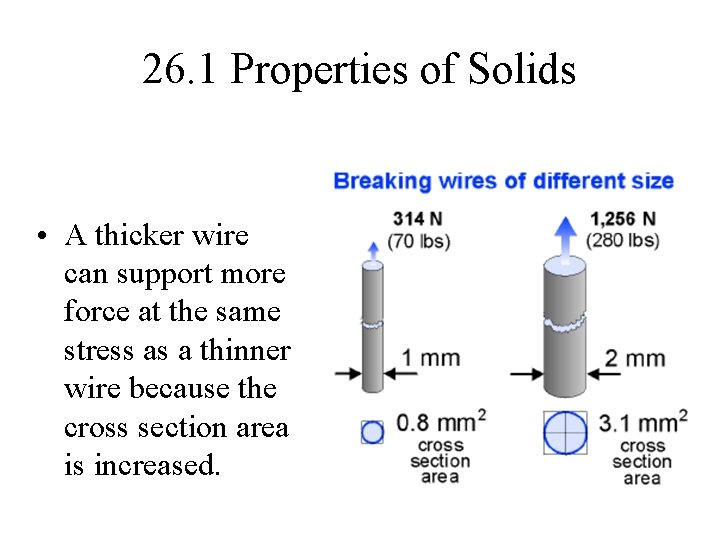

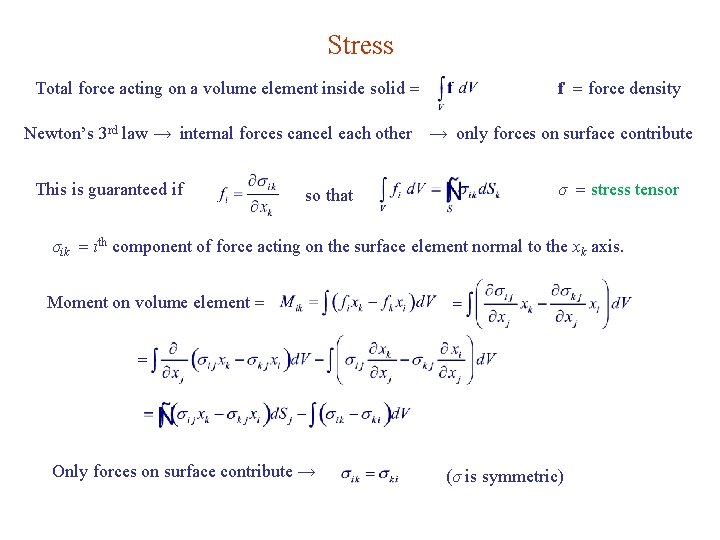

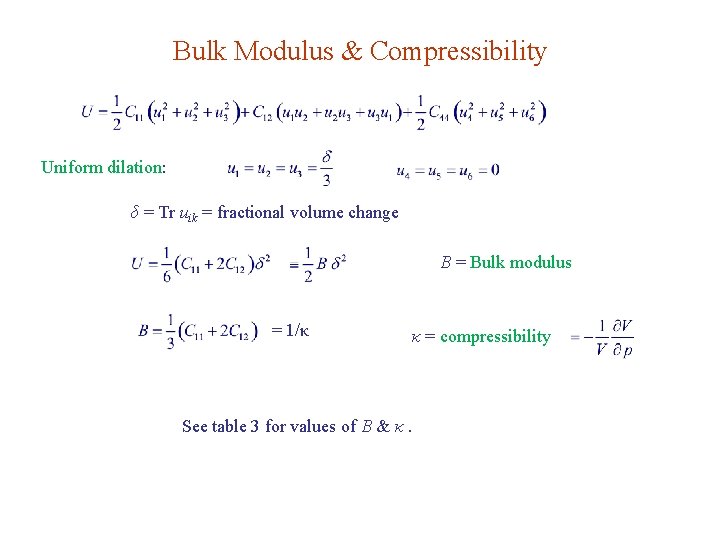

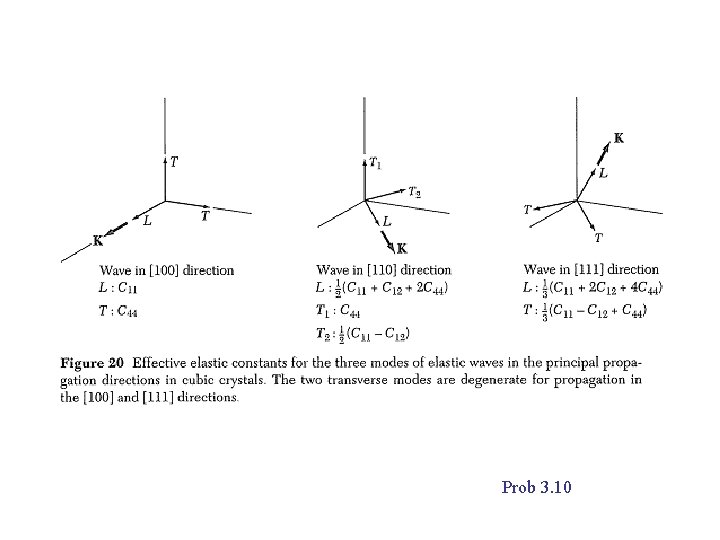

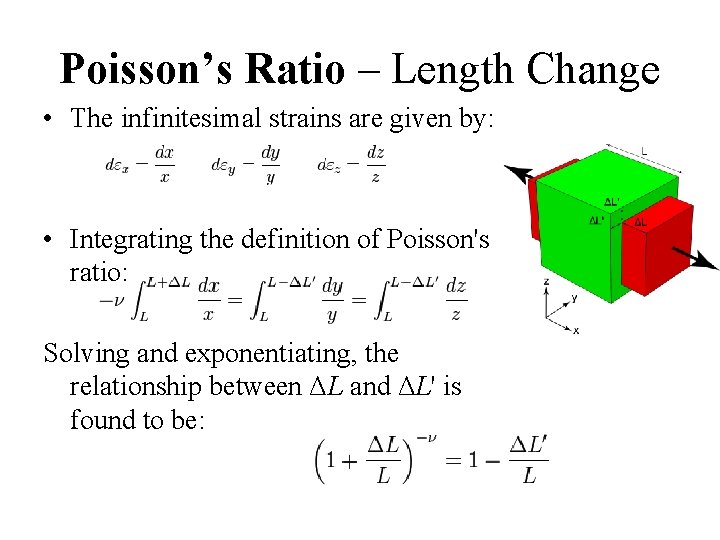

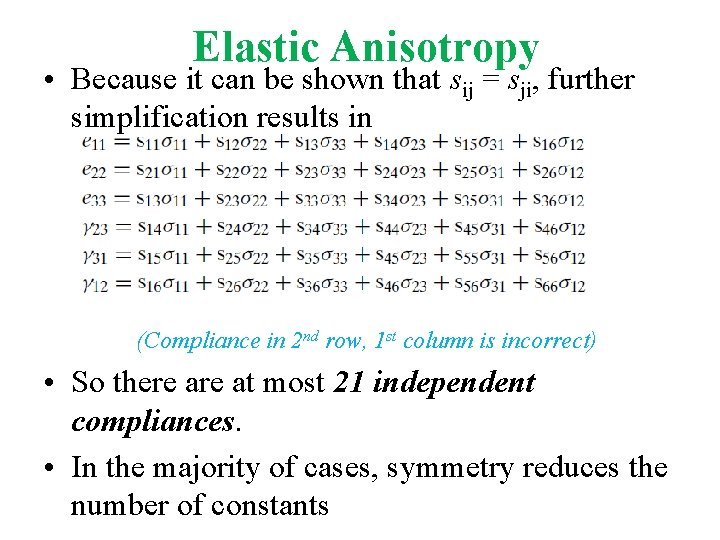

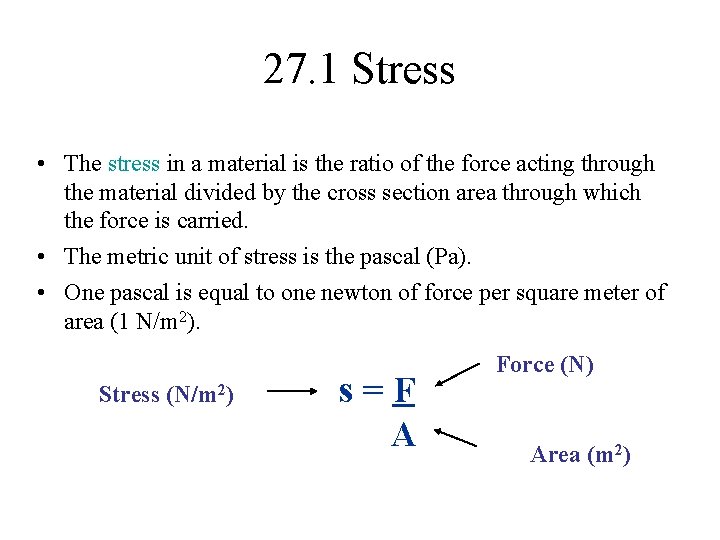

Waves in the [100] direction → Longitudinal Transverse, degenerate

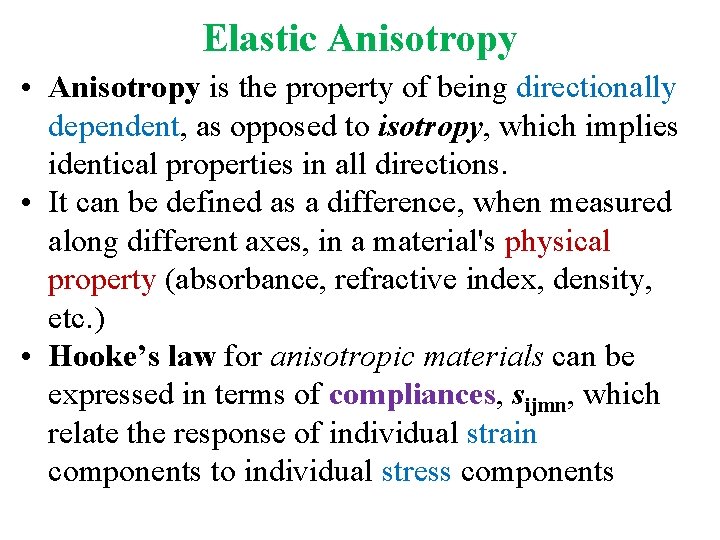

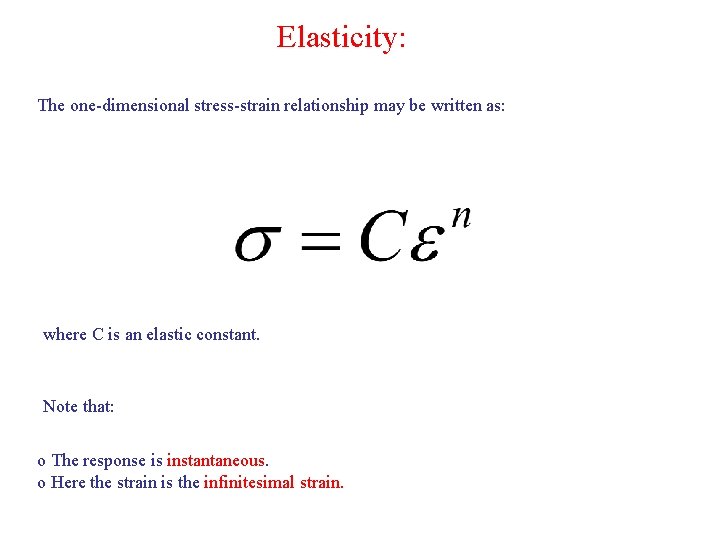

![Waves in the 110 direction Lonitudinal Transverse Waves in the [110] direction → Lonitudinal Transverse](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/660768df84d58c570409fd8f6c31315c/image-11.jpg)

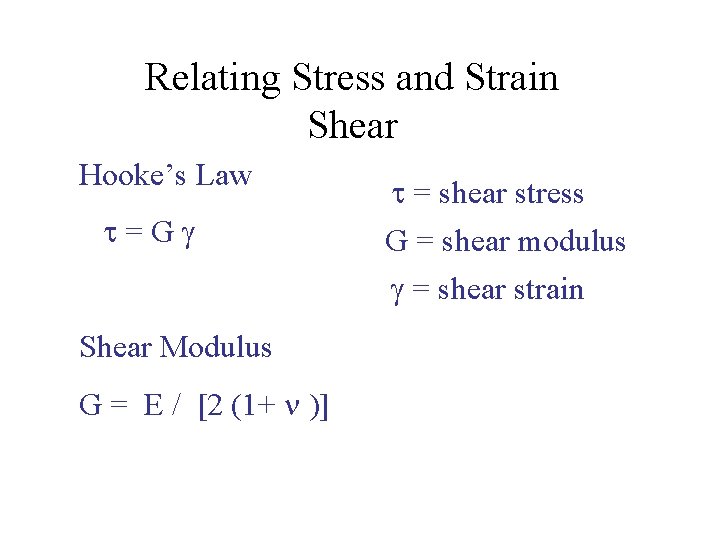

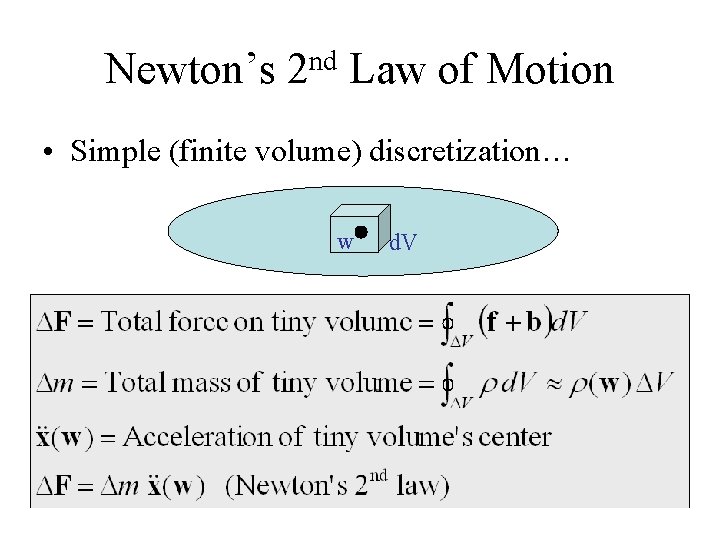

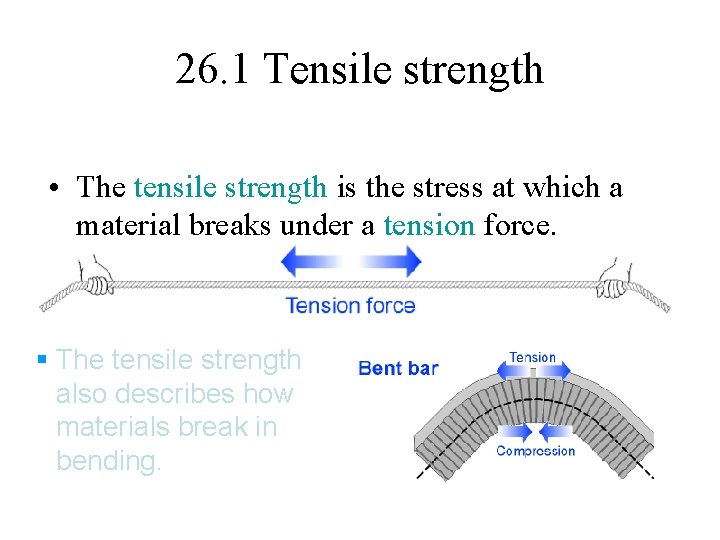

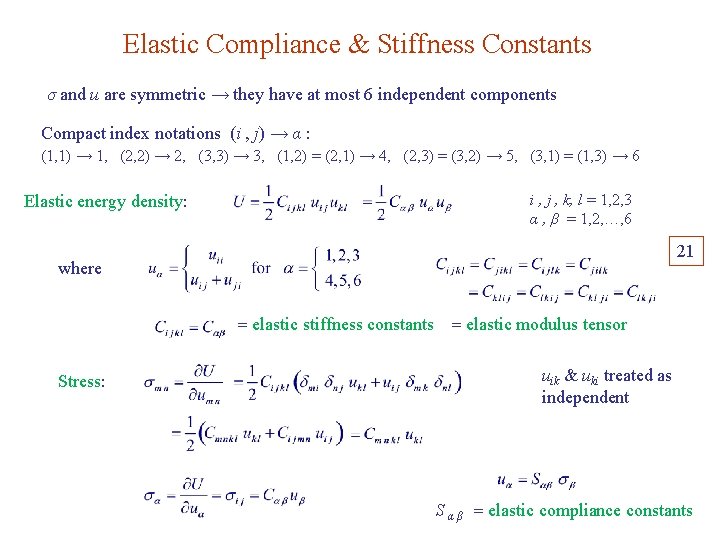

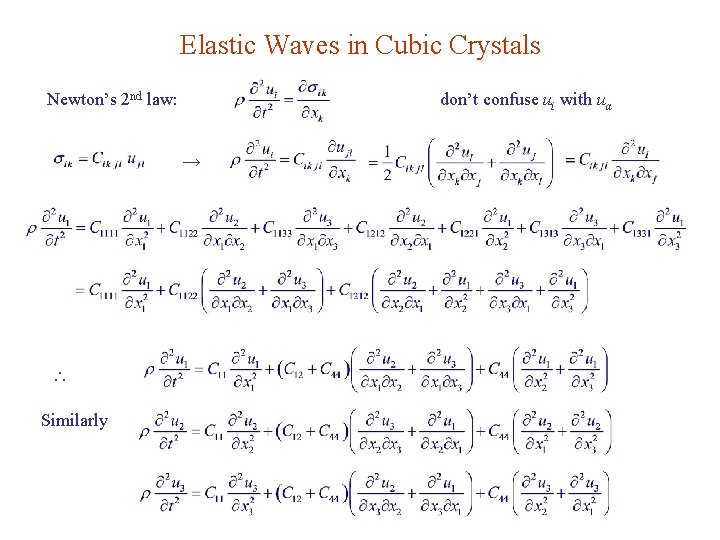

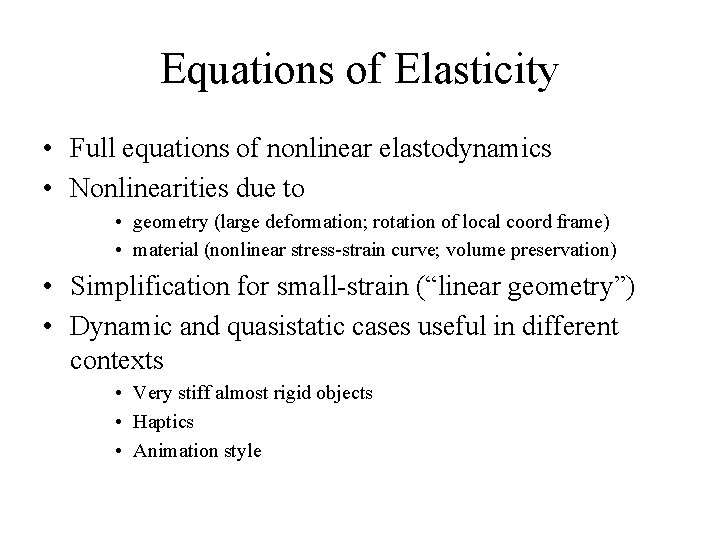

Waves in the [110] direction → Lonitudinal Transverse

Prob 3. 10

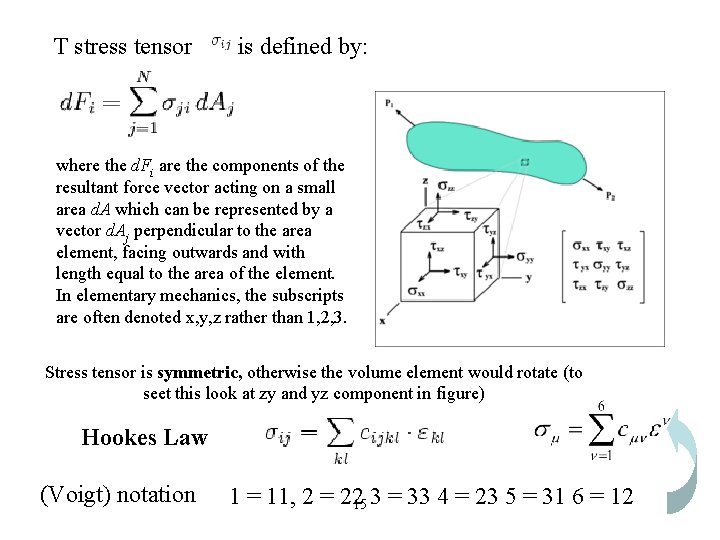

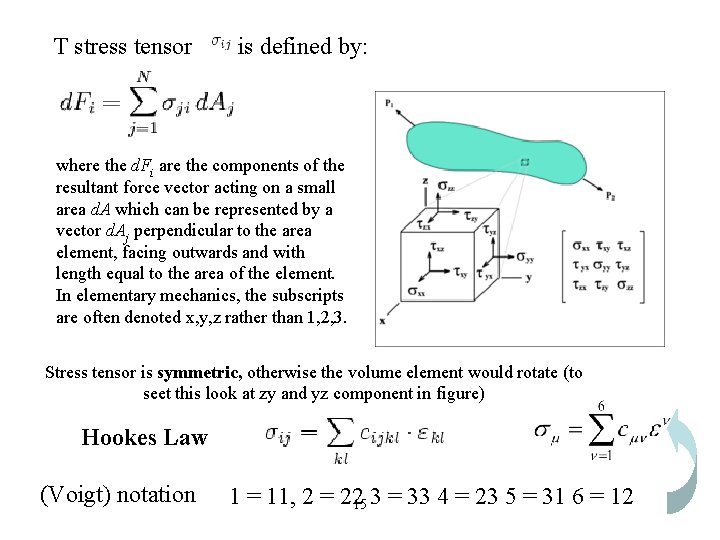

T stress tensor is defined by: where the d. Fi are the components of the resultant force vector acting on a small area d. A which can be represented by a vector d. Aj perpendicular to the area element, facing outwards and with length equal to the area of the element. In elementary mechanics, the subscripts are often denoted x, y, z rather than 1, 2, 3. Stress tensor is symmetric, otherwise the volume element would rotate (to seet this look at zy and yz component in figure) Hookes Law (Voigt) notation 1 = 11, 2 = 2215 3 = 33 4 = 23 5 = 31 6 = 12

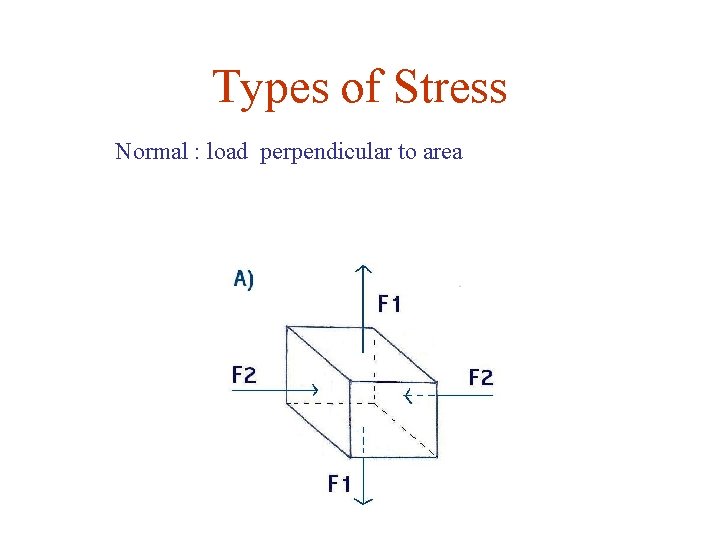

Types of Stress Normal : load perpendicular to area

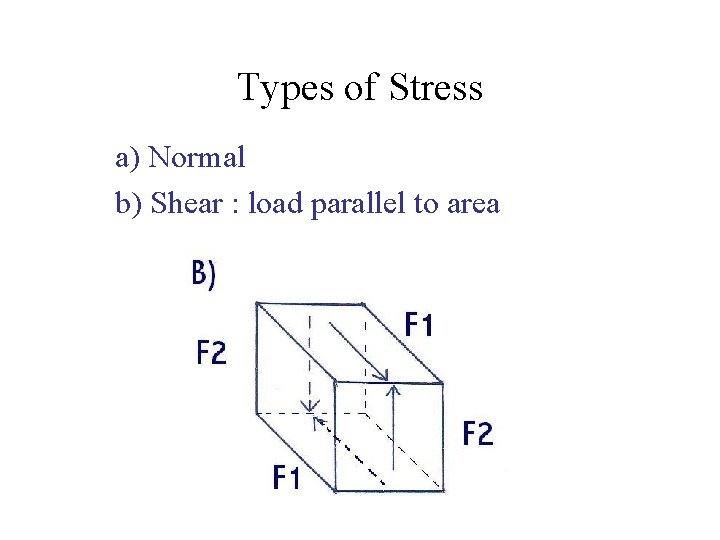

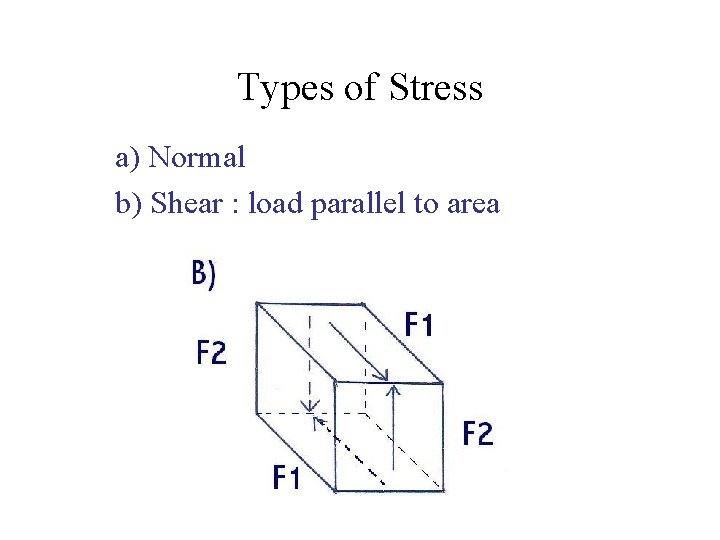

Types of Stress a) Normal b) Shear : load parallel to area

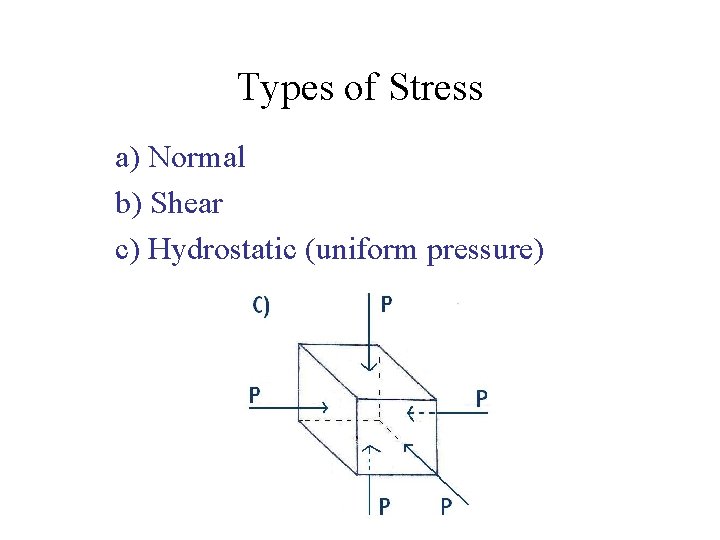

Types of Stress a) Normal b) Shear c) Hydrostatic (uniform pressure)

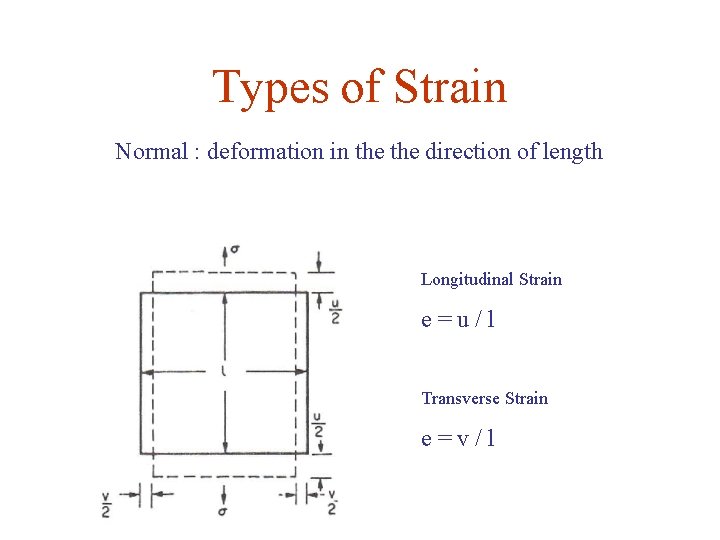

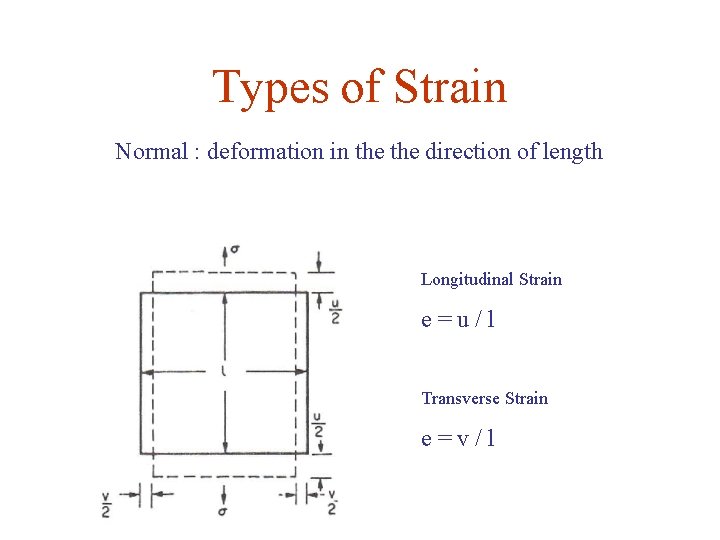

Types of Strain Normal : deformation in the direction of length Longitudinal Strain e=u/l Transverse Strain e=v/l

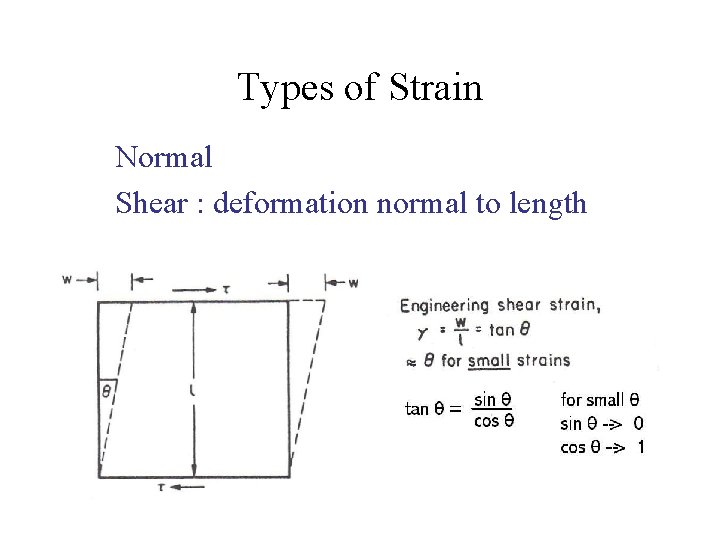

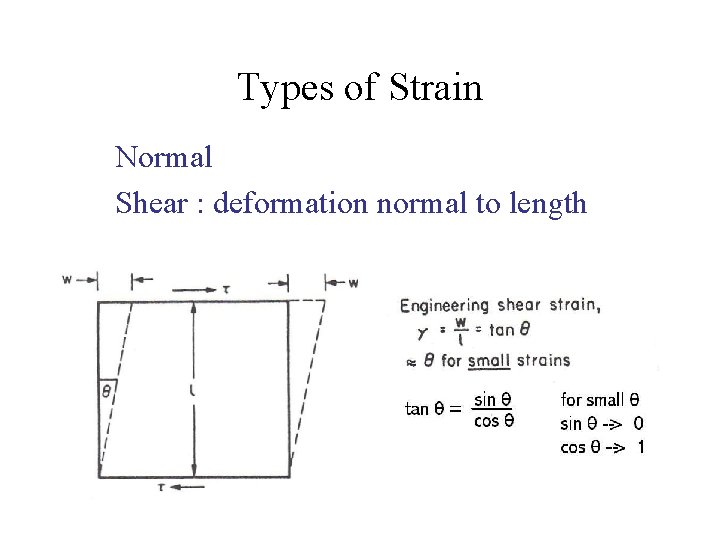

Types of Strain Normal Shear : deformation normal to length

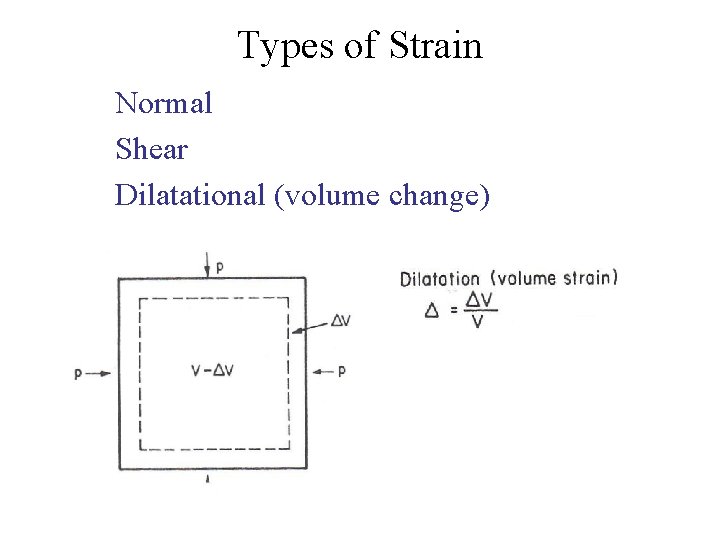

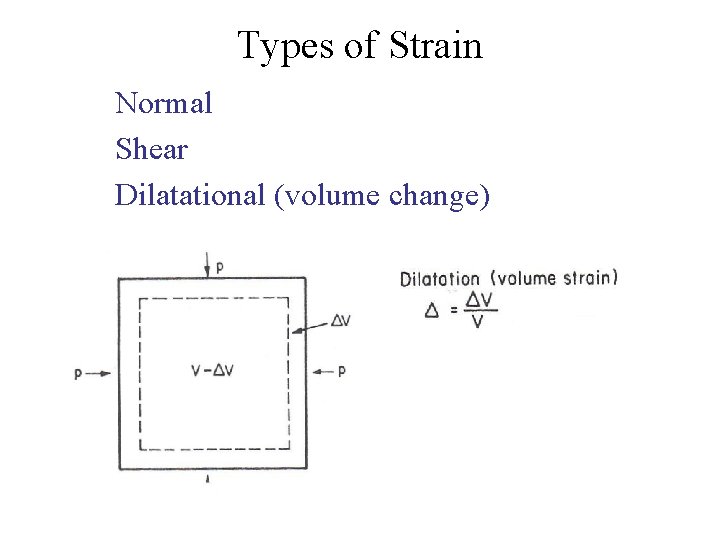

Types of Strain Normal Shear Dilatational (volume change)

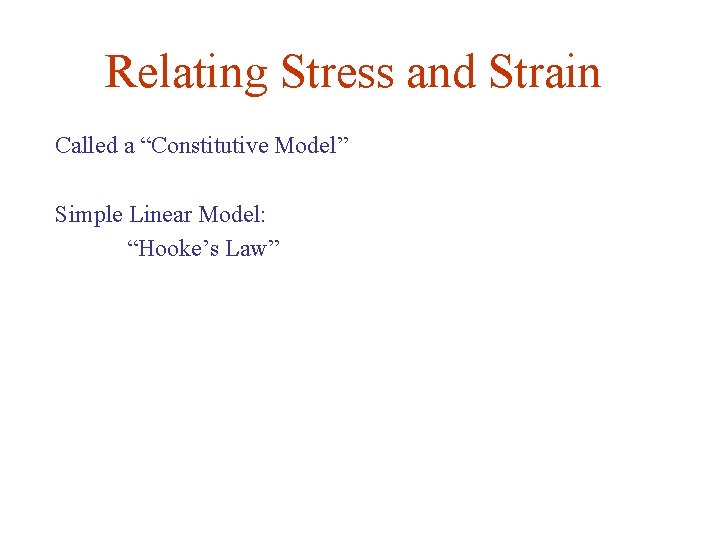

Relating Stress and Strain Called a “Constitutive Model” Simple Linear Model: “Hooke’s Law”

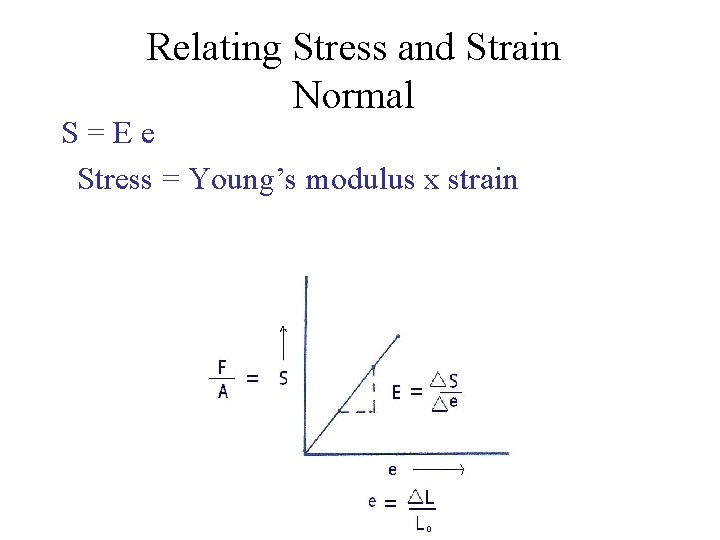

Relating Stress and Strain Normal S=Ee Stress = Young’s modulus x strain

Relating Stress and Strain Shear Hooke’s Law =G Shear Modulus G = E / [2 (1+ )] = shear stress G = shear modulus = shear strain

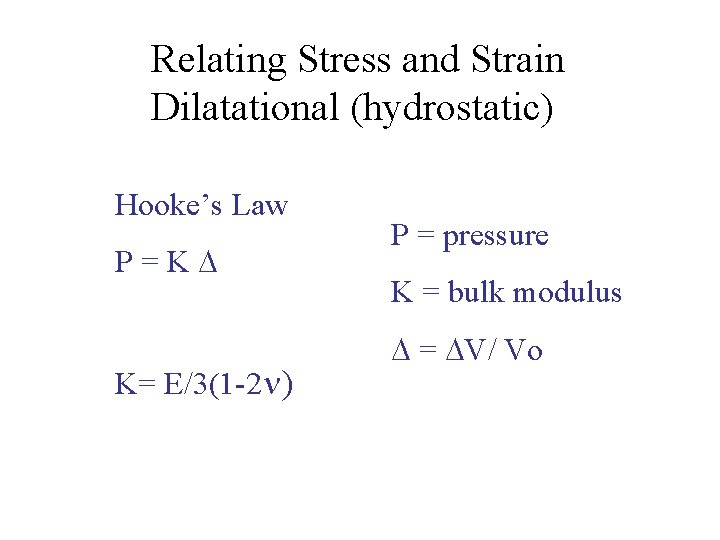

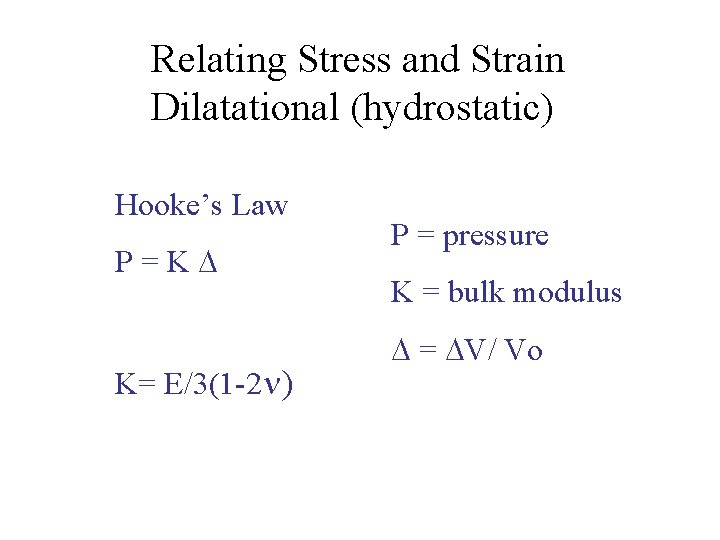

Relating Stress and Strain Dilatational (hydrostatic) Hooke’s Law P=K K= E/3(1 -2 ) P = pressure K = bulk modulus = V/ Vo

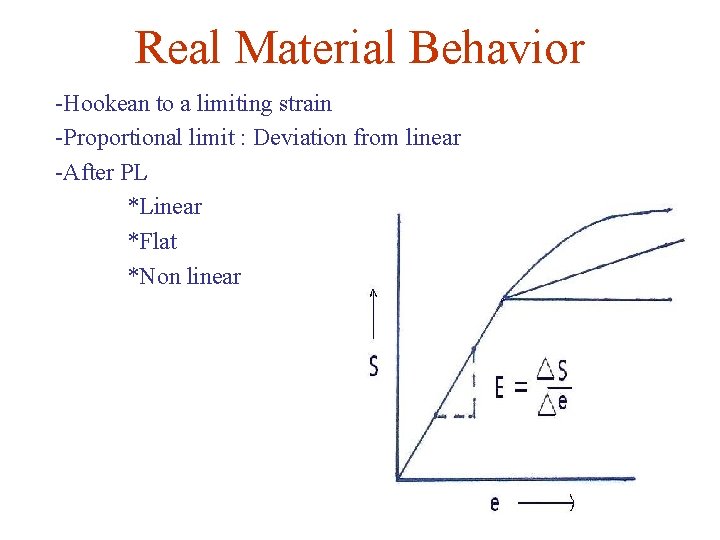

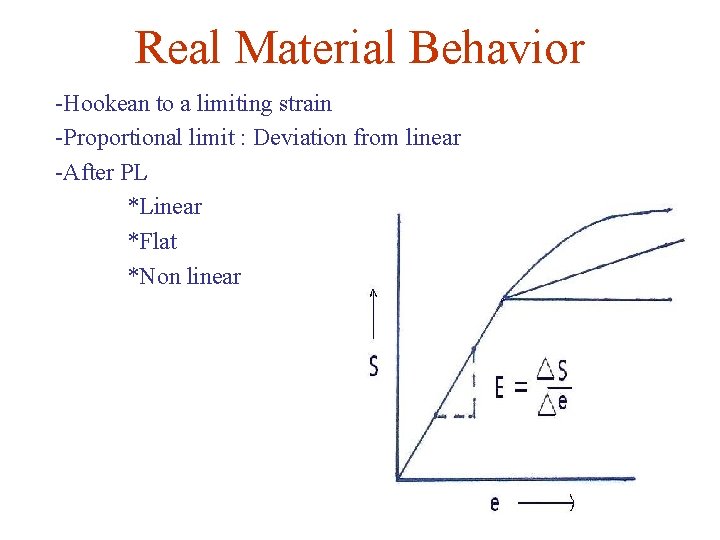

Real Material Behavior -Hookean to a limiting strain -Proportional limit : Deviation from linear -After PL *Linear *Flat *Non linear

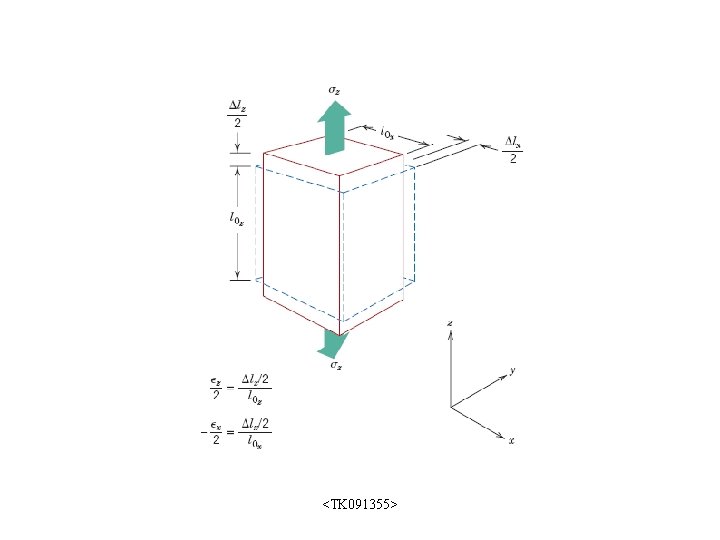

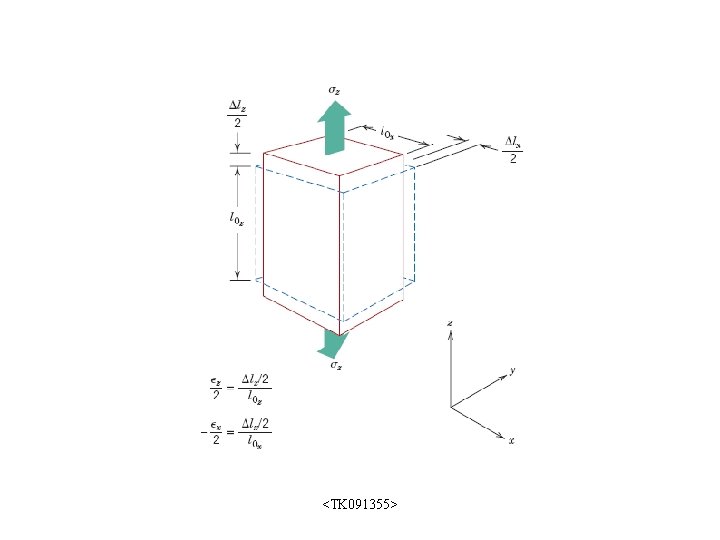

ELASTIC PROPERTIES OF MATERIALS • When a tensile stress is imposed on a metal specimen, an elastic elongation and accompanying strain result in the direction of the applied stress (z). – As a result: • constrictions in the lateral (x and y) directions perpendicular to the tension stress • compressive strains <TK 091355>

<TK 091355>

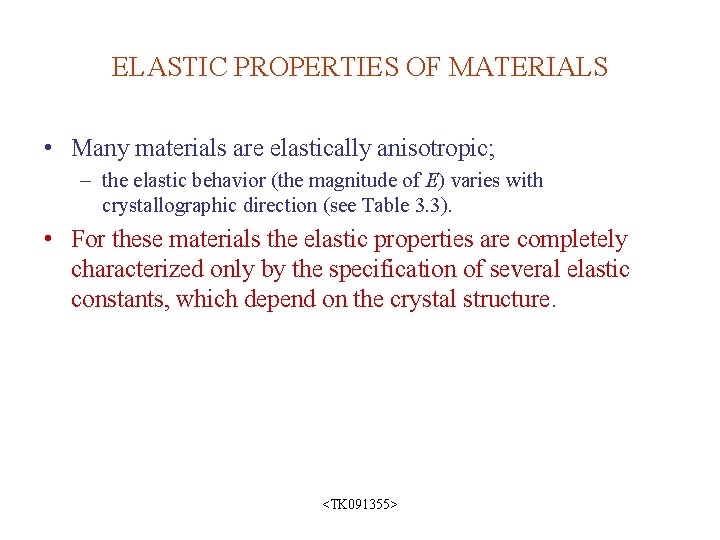

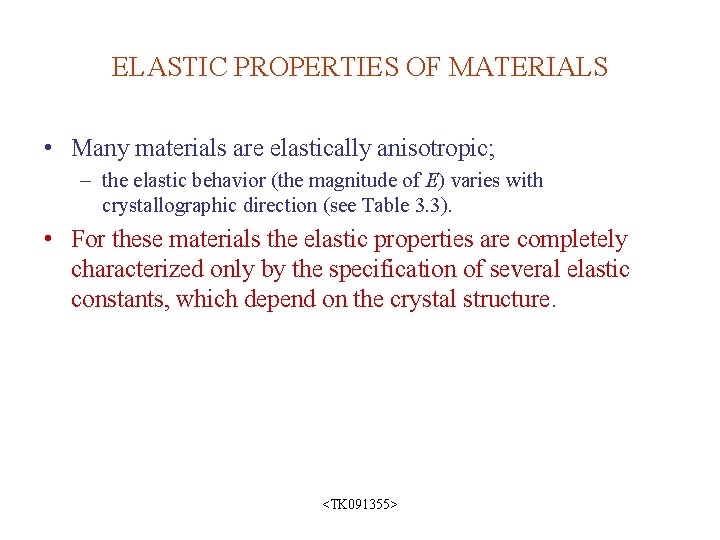

ELASTIC PROPERTIES OF MATERIALS • Many materials are elastically anisotropic; – the elastic behavior (the magnitude of E) varies with crystallographic direction (see Table 3. 3). • For these materials the elastic properties are completely characterized only by the specification of several elastic constants, which depend on the crystal structure. <TK 091355>

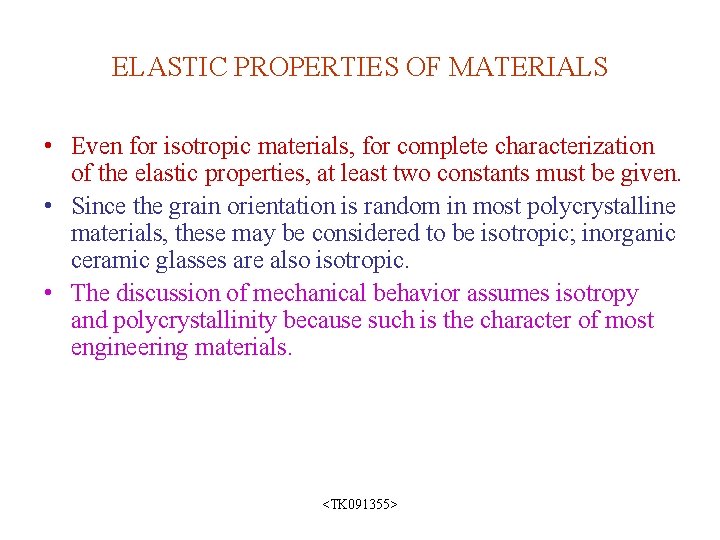

ELASTIC PROPERTIES OF MATERIALS • Even for isotropic materials, for complete characterization of the elastic properties, at least two constants must be given. • Since the grain orientation is random in most polycrystalline materials, these may be considered to be isotropic; inorganic ceramic glasses are also isotropic. • The discussion of mechanical behavior assumes isotropy and polycrystallinity because such is the character of most engineering materials. <TK 091355>

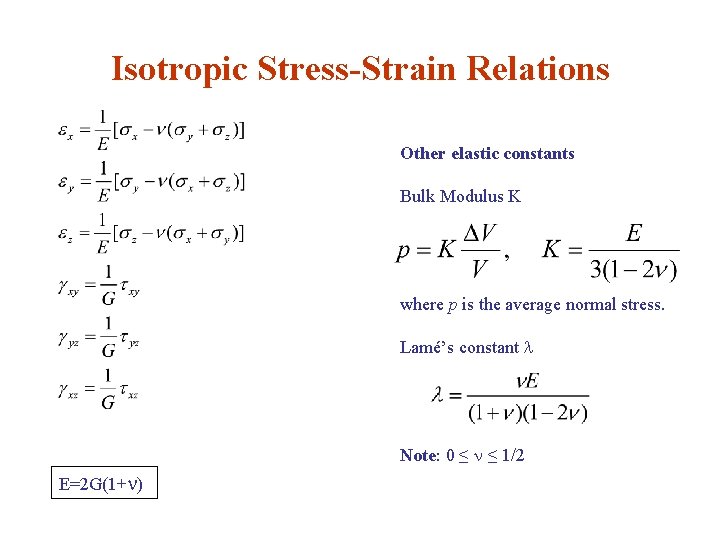

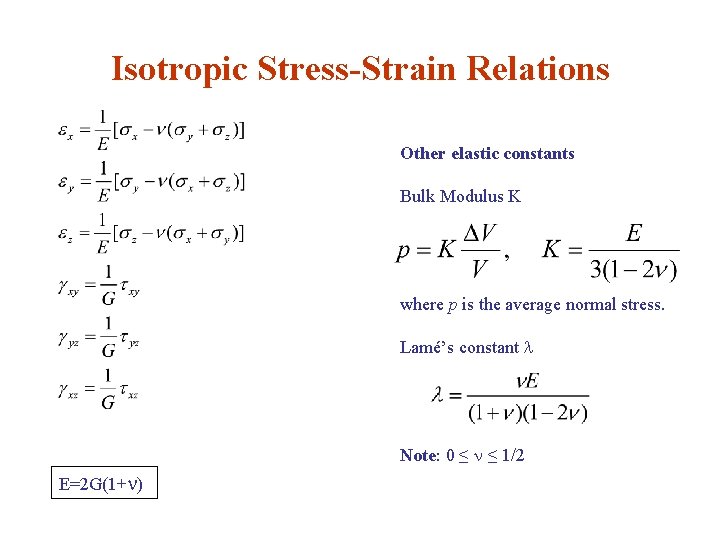

Isotropic Stress-Strain Relations Other elastic constants Bulk Modulus K where p is the average normal stress. Lamé’s constant Note: 0 ≤ ≤ 1/2 E=2 G(1+ )

Relations Among the Elastic Constants R. Reismann and P. S. Pawlik, Elasticity: Theory and Practice, Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company , 1991

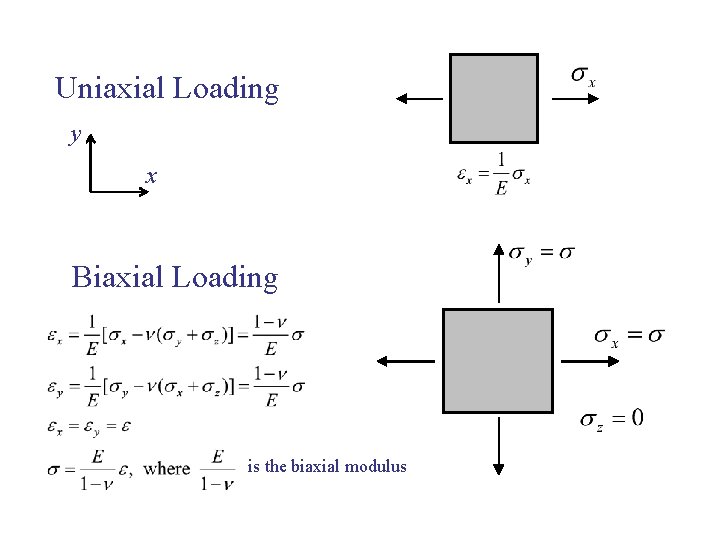

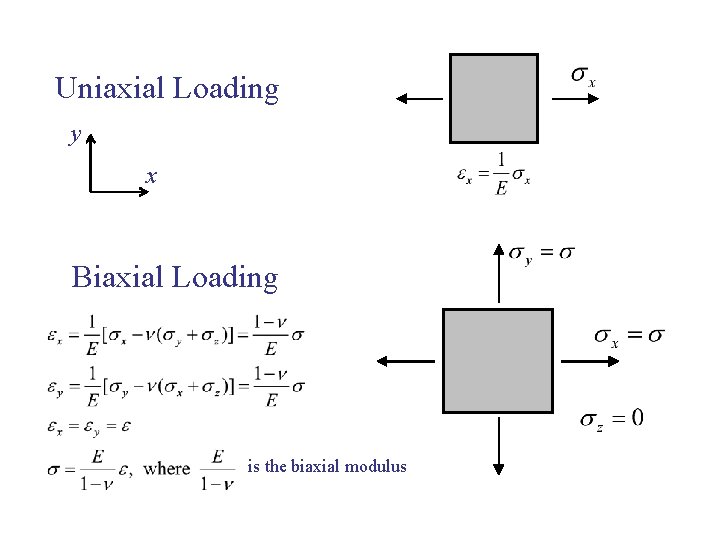

Uniaxial Loading y x Biaxial Loading is the biaxial modulus

![Anisotropic Materials where C is the 6 x 6 stiffness matrix where S Anisotropic Materials where [C] is the 6 x 6 stiffness matrix where [S] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/660768df84d58c570409fd8f6c31315c/image-34.jpg)

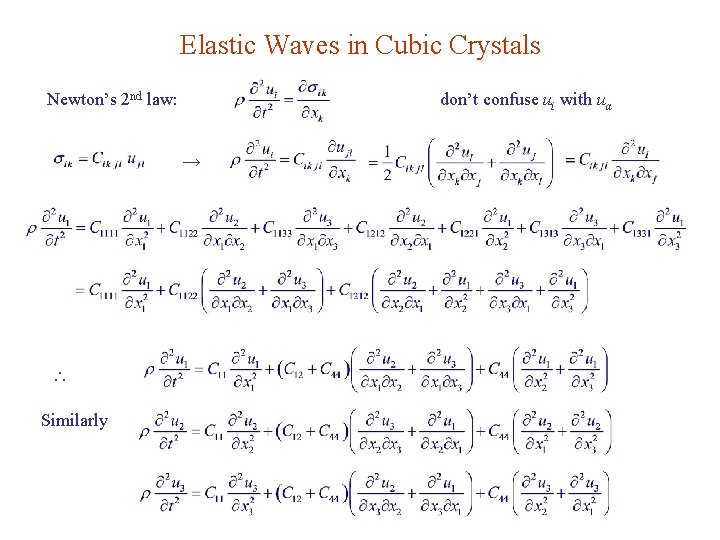

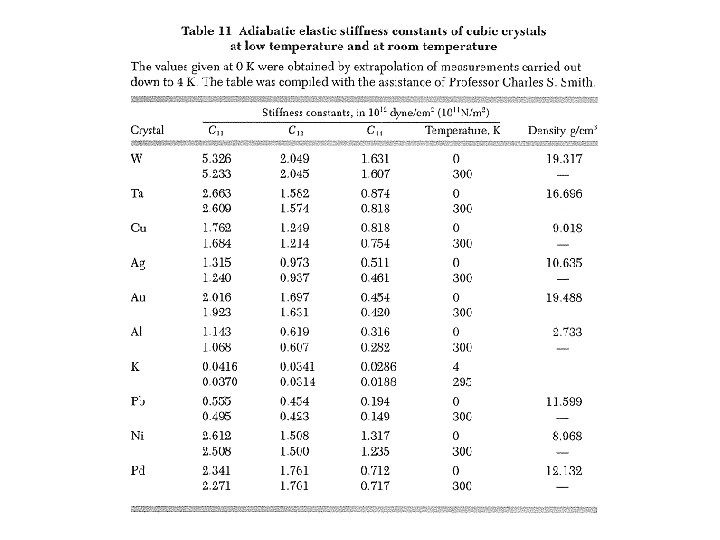

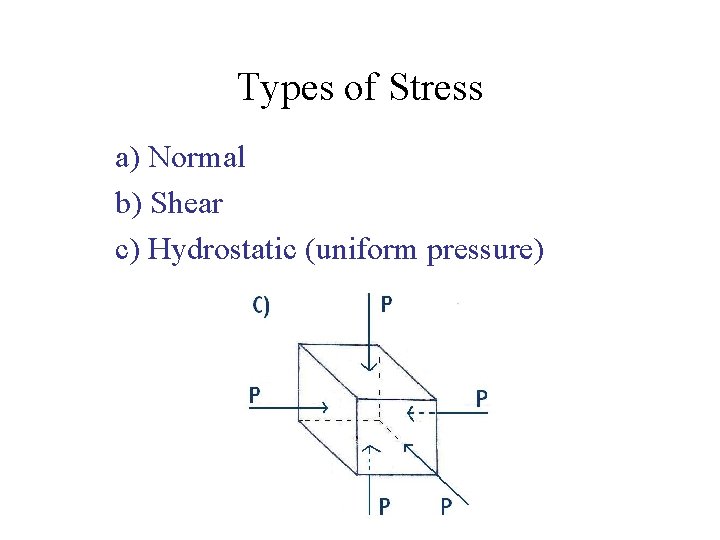

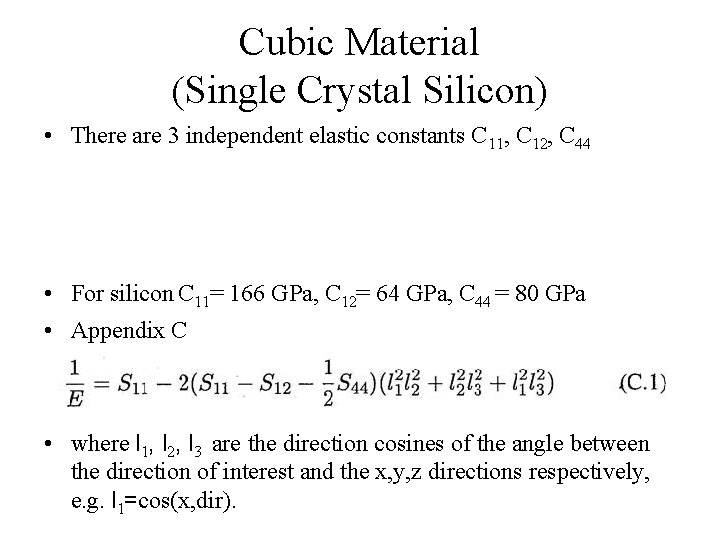

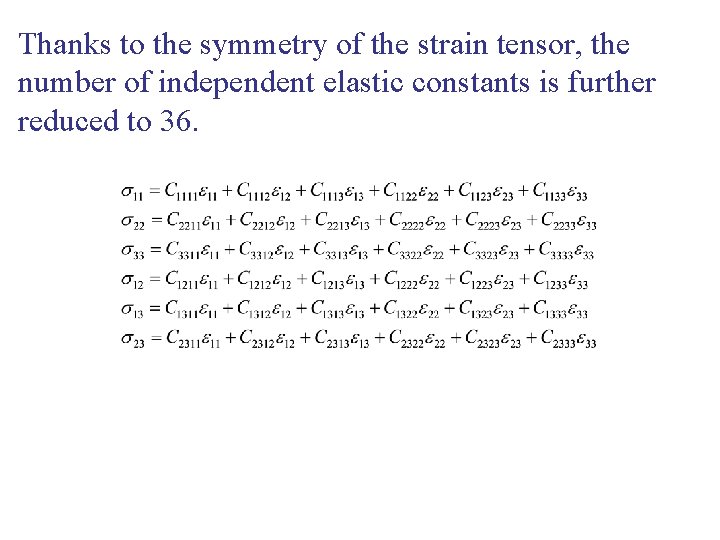

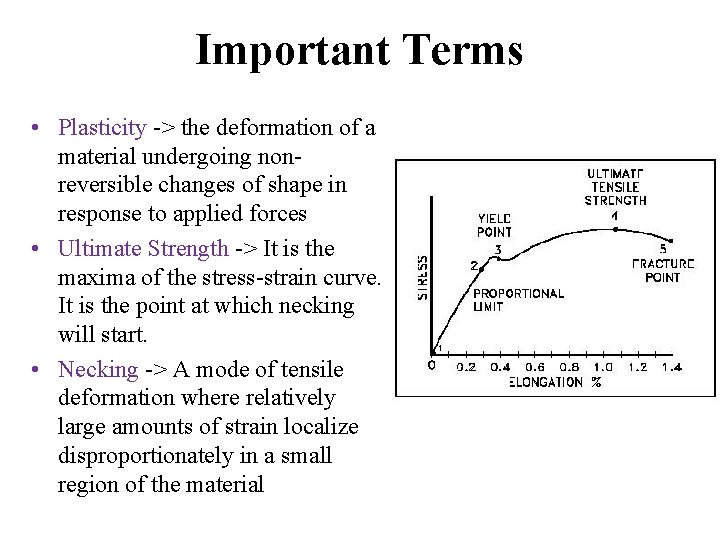

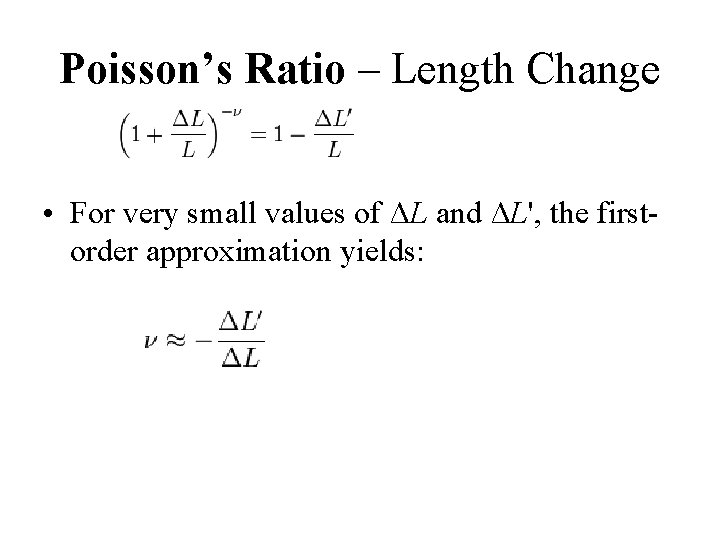

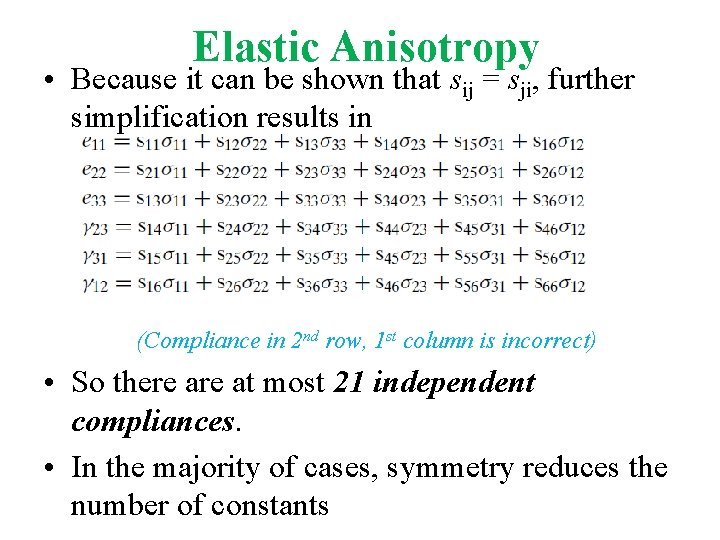

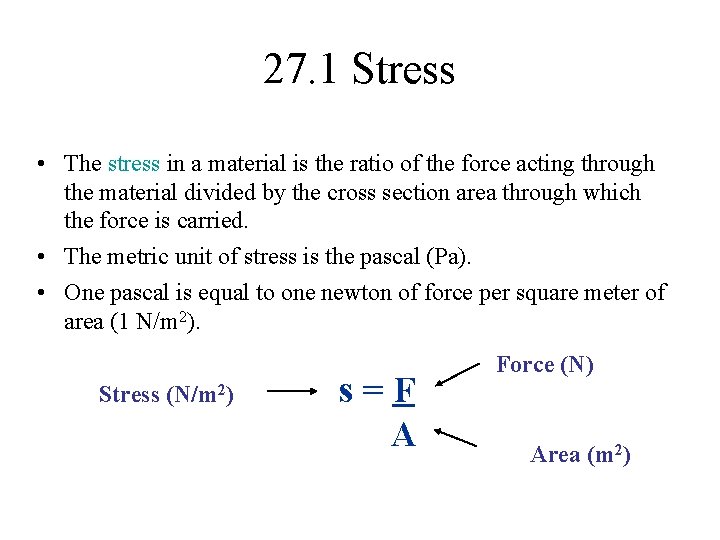

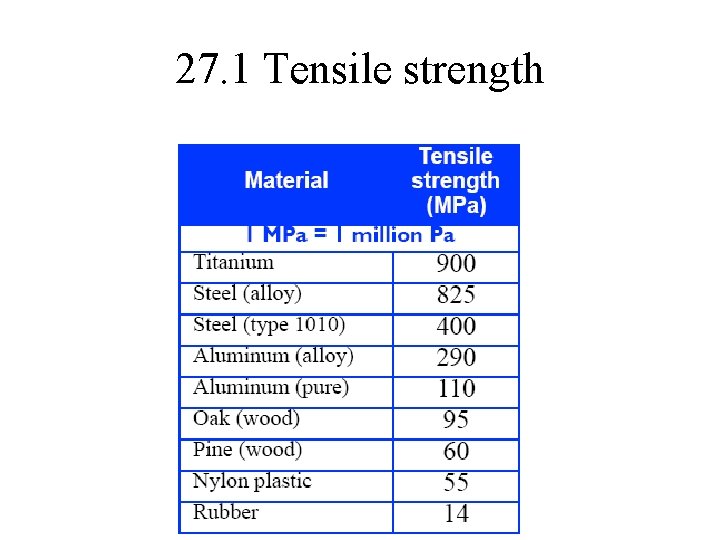

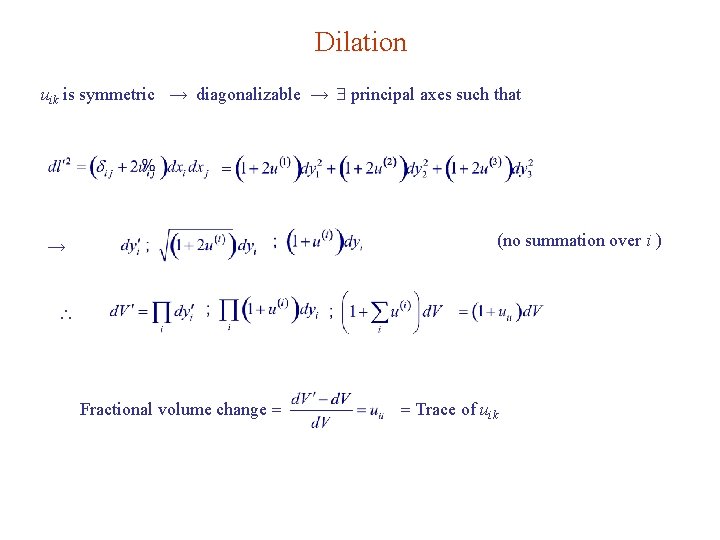

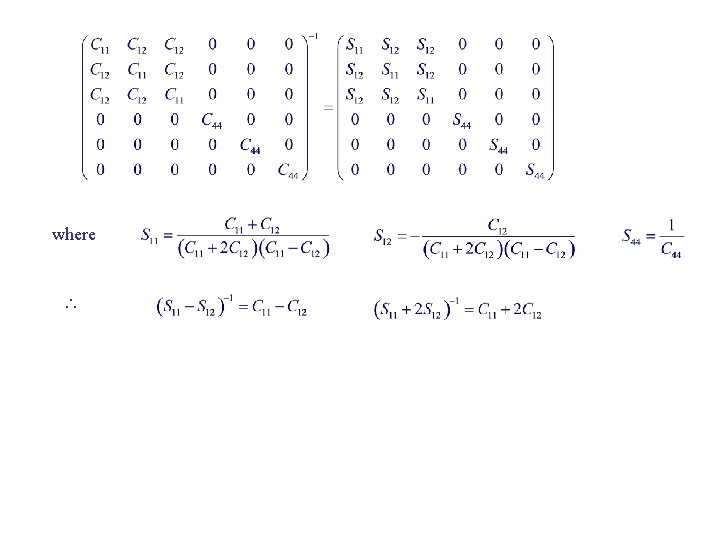

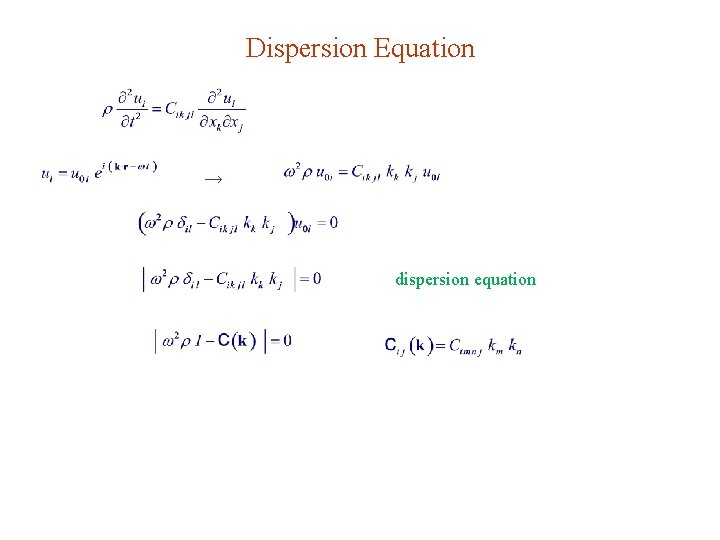

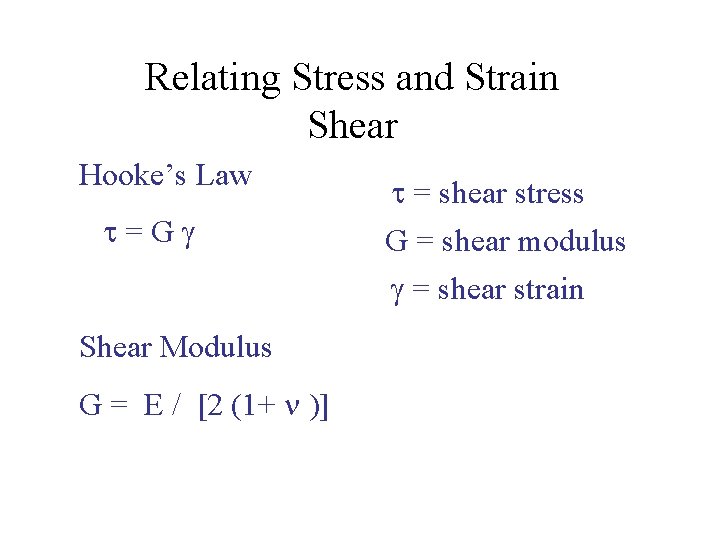

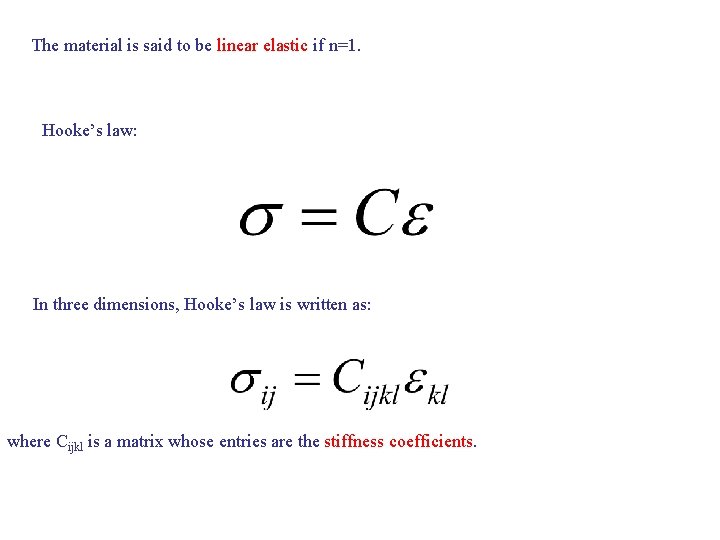

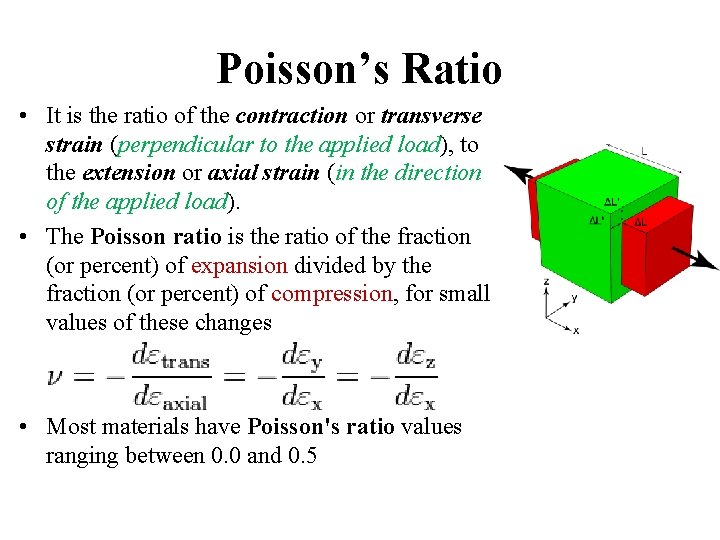

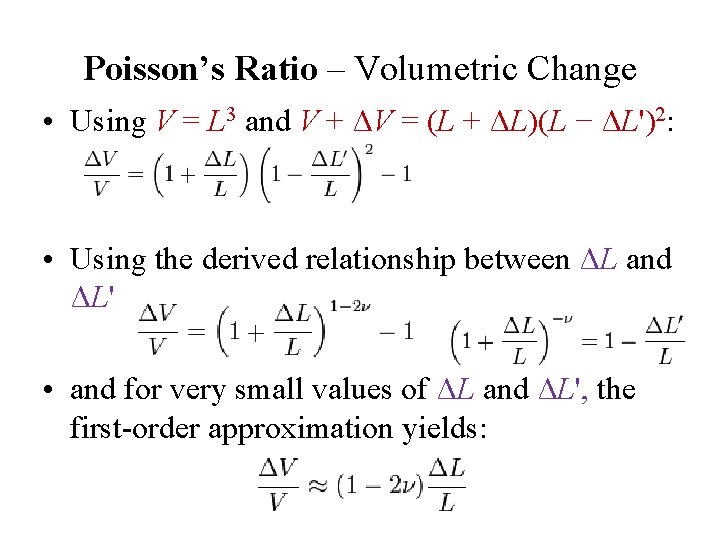

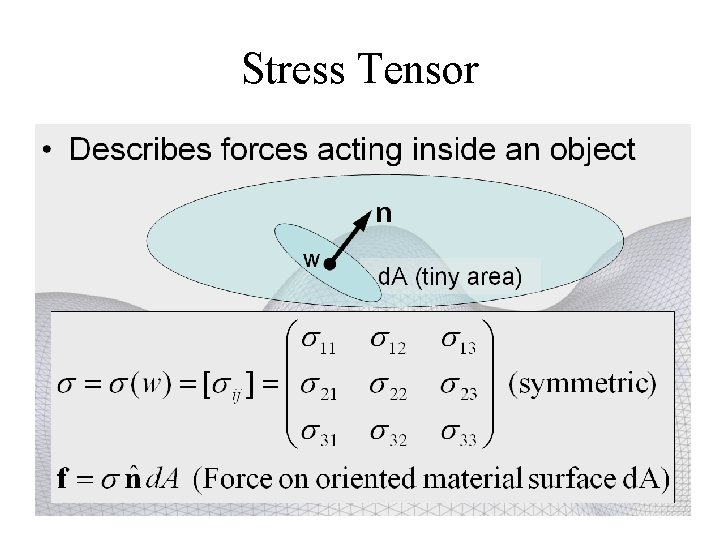

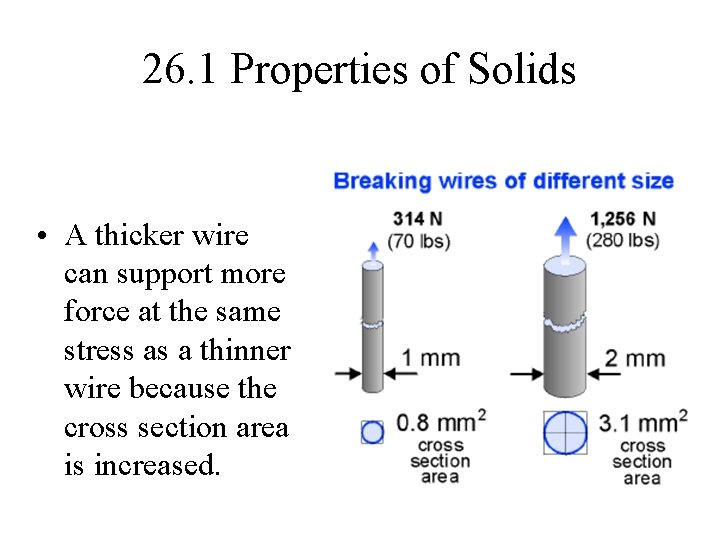

Anisotropic Materials where [C] is the 6 x 6 stiffness matrix where [S] = [C]-1 is the 6 x 6 compliance matrix

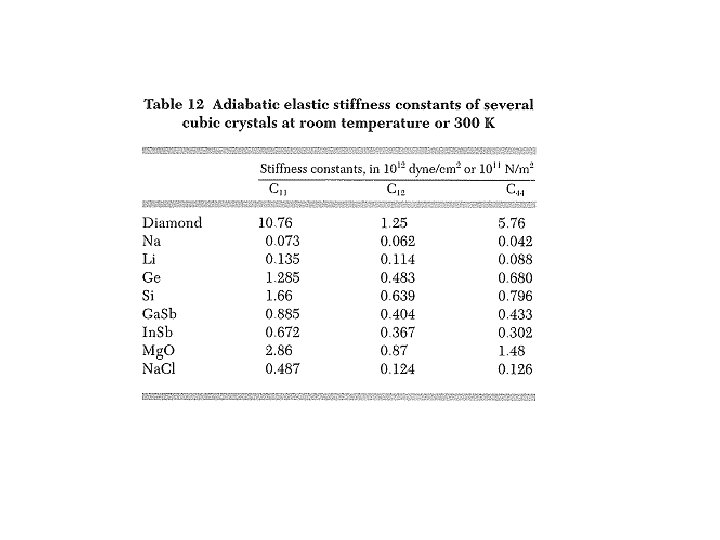

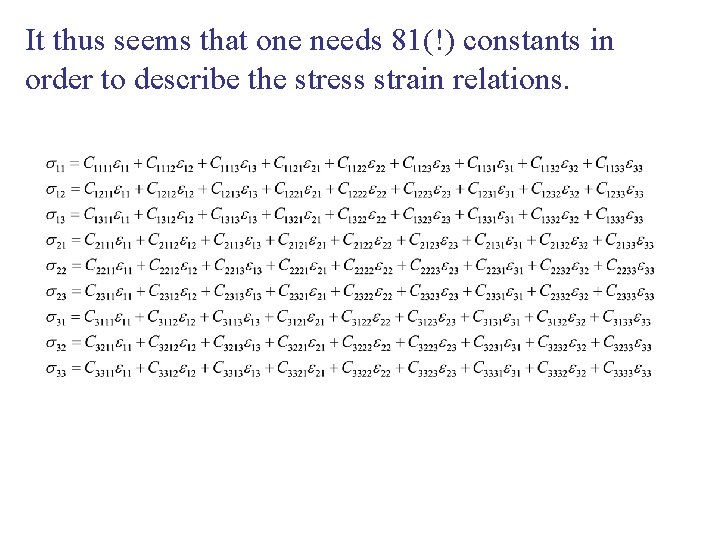

Cubic Material (Single Crystal Silicon) • There are 3 independent elastic constants C 11, C 12, C 44 • For silicon C 11= 166 GPa, C 12= 64 GPa, C 44 = 80 GPa • Appendix C • where l 1, l 2, l 3 are the direction cosines of the angle between the direction of interest and the x, y, z directions respectively, e. g. l 1=cos(x, dir).

Elasticity: The one-dimensional stress-strain relationship may be written as: where C is an elastic constant. Note that: o The response is instantaneous. o Here the strain is the infinitesimal strain.

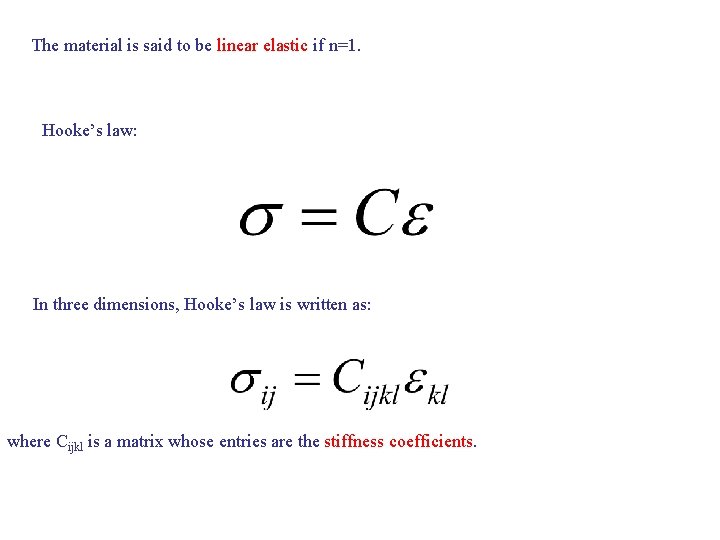

The material is said to be linear elastic if n=1. Hooke’s law: In three dimensions, Hooke’s law is written as: where Cijkl is a matrix whose entries are the stiffness coefficients.

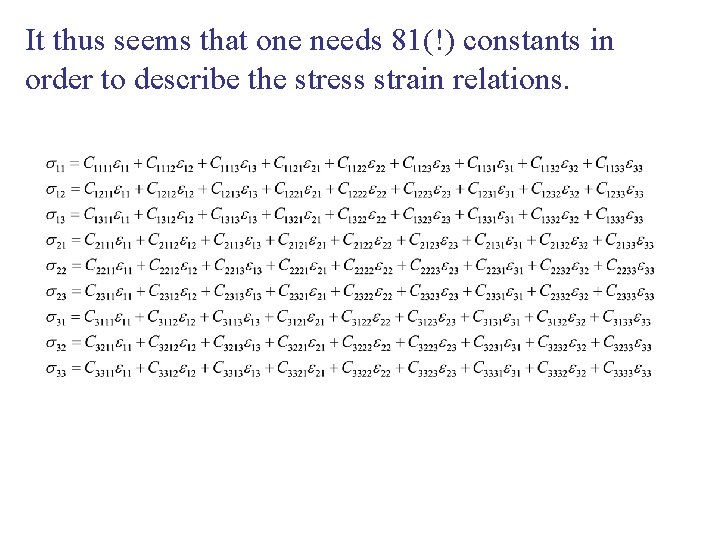

It thus seems that one needs 81(!) constants in order to describe the stress strain relations.

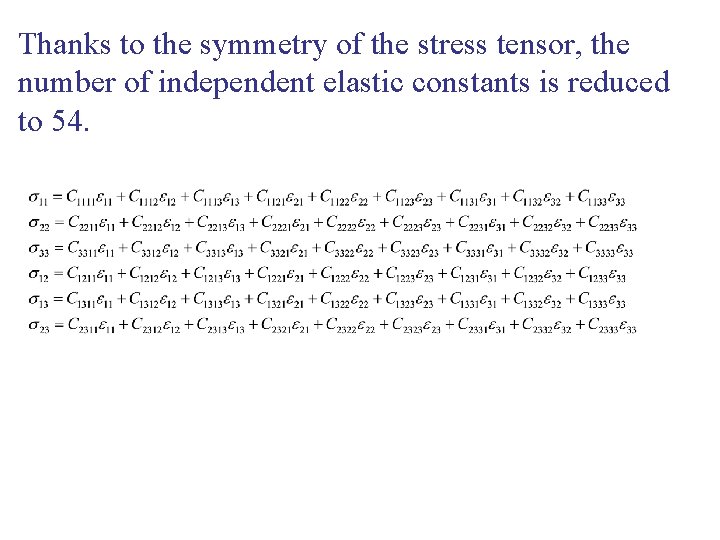

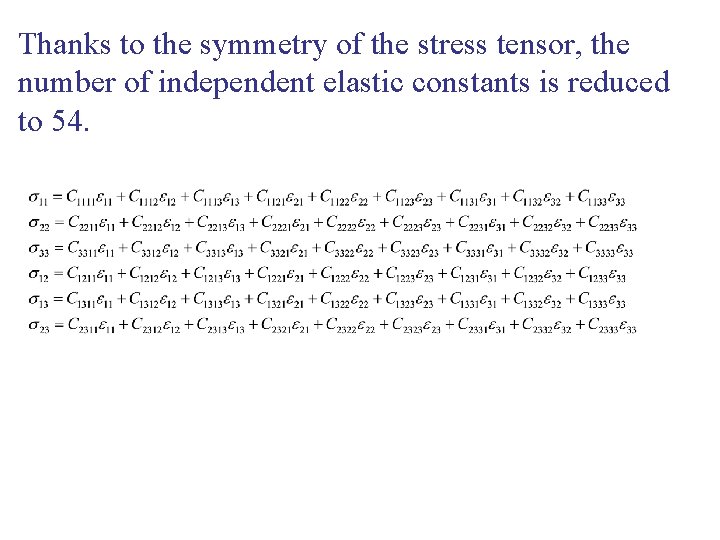

Thanks to the symmetry of the stress tensor, the number of independent elastic constants is reduced to 54.

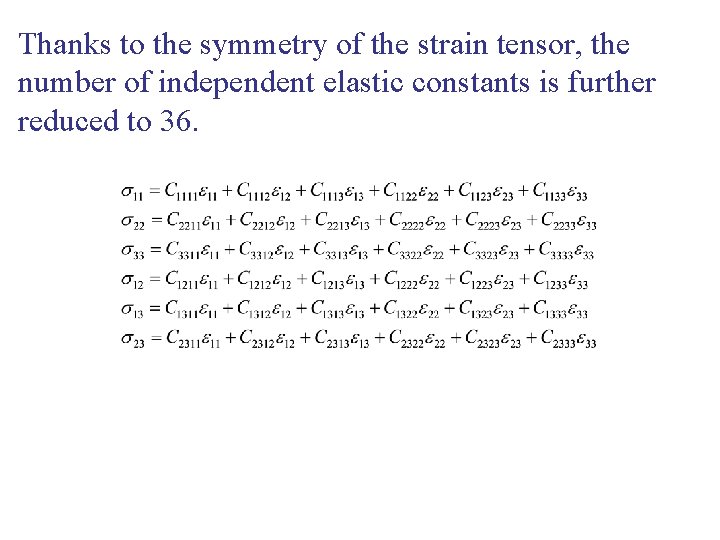

Thanks to the symmetry of the strain tensor, the number of independent elastic constants is further reduced to 36.

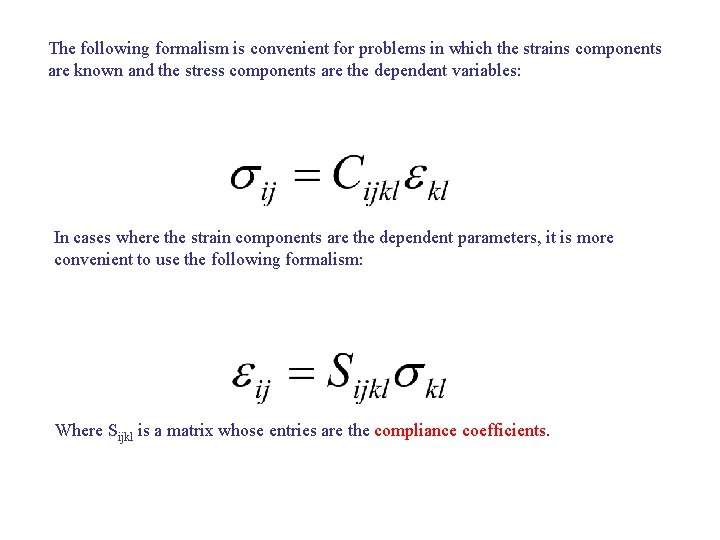

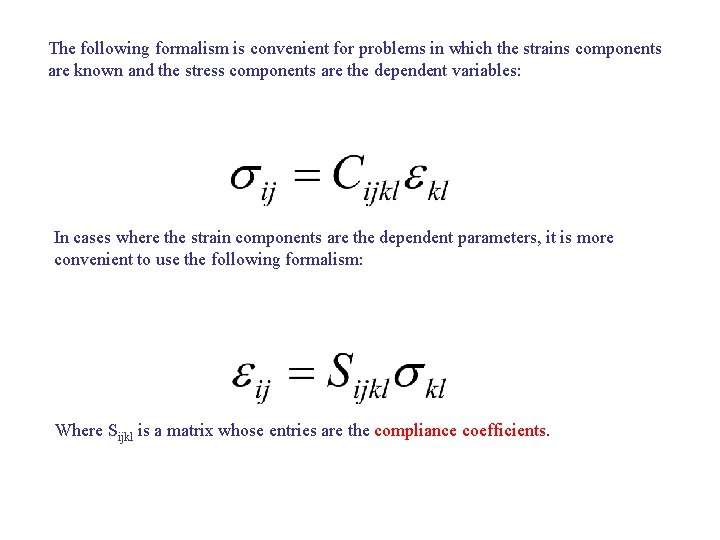

The following formalism is convenient for problems in which the strains components are known and the stress components are the dependent variables: In cases where the strain components are the dependent parameters, it is more convenient to use the following formalism: Where Sijkl is a matrix whose entries are the compliance coefficients.

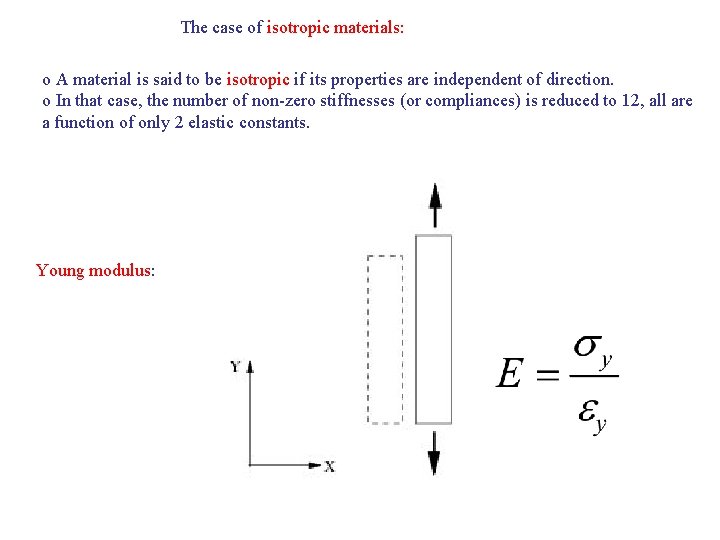

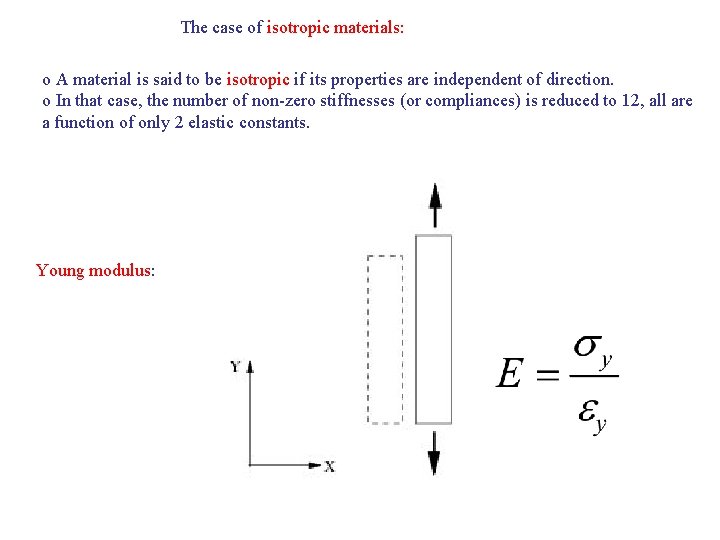

The case of isotropic materials: o A material is said to be isotropic if its properties are independent of direction. o In that case, the number of non-zero stiffnesses (or compliances) is reduced to 12, all are a function of only 2 elastic constants. Young modulus:

Shear modulus (rigidity): Bulk modulus (compressibility):

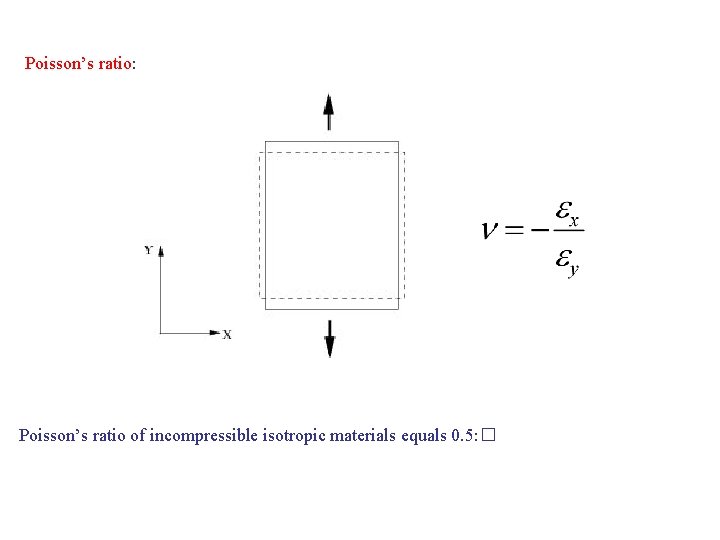

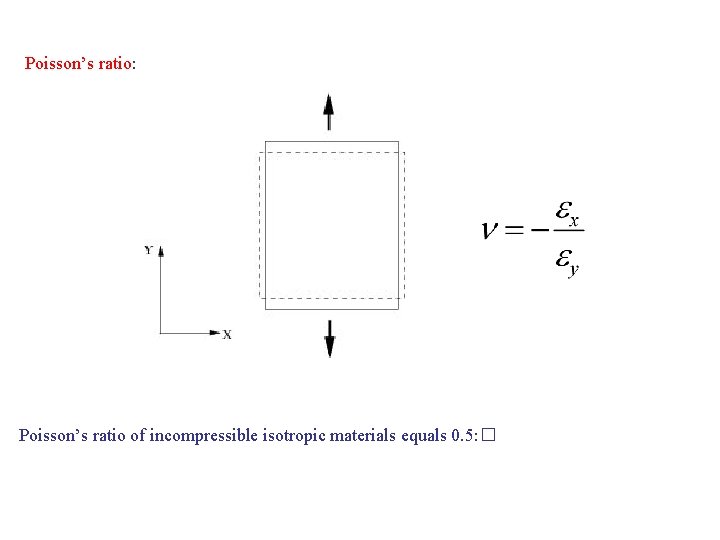

Poisson’s ratio: Poisson’s ratio of incompressible isotropic materials equals 0. 5: �

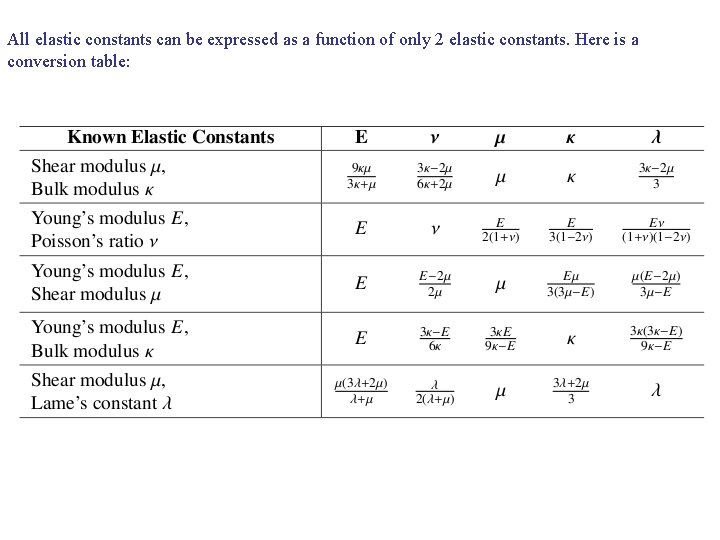

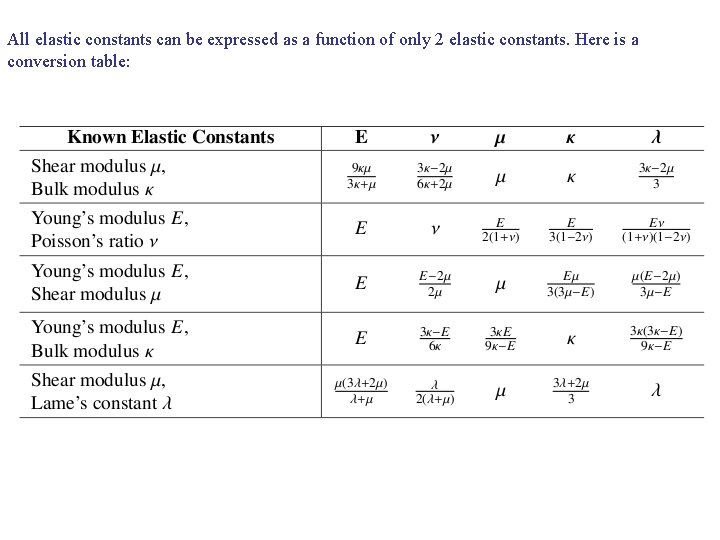

All elastic constants can be expressed as a function of only 2 elastic constants. Here is a conversion table:

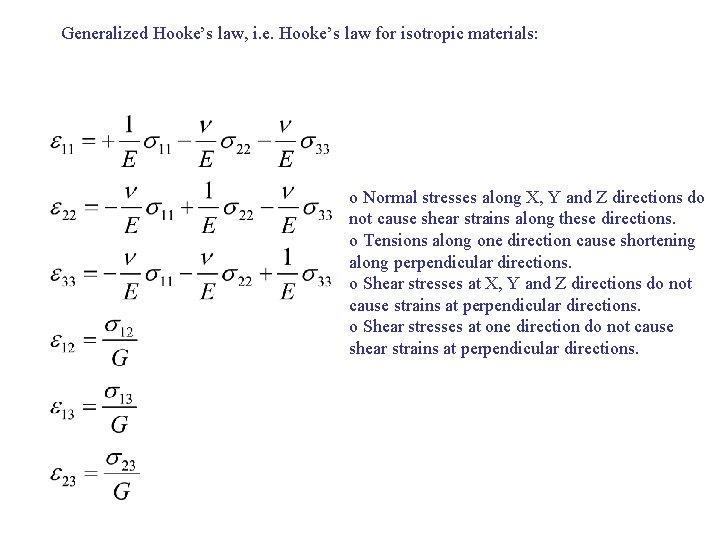

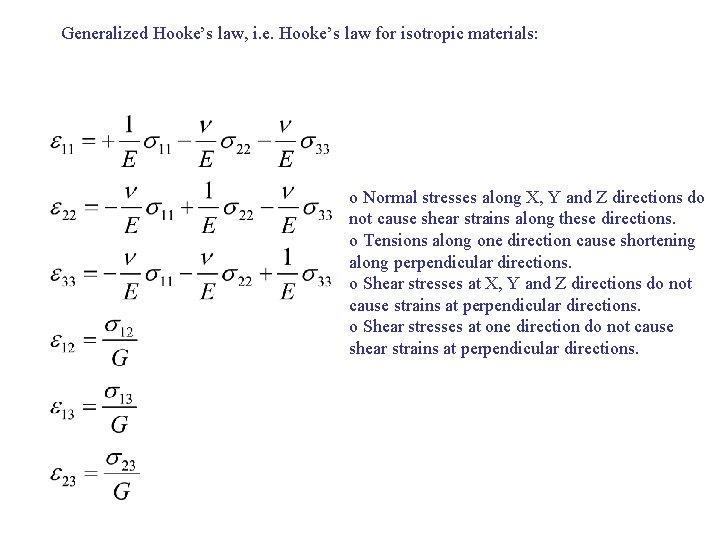

Generalized Hooke’s law, i. e. Hooke’s law for isotropic materials: o Normal stresses along X, Y and Z directions do not cause shear strains along these directions. o Tensions along one direction cause shortening along perpendicular directions. o Shear stresses at X, Y and Z directions do not cause strains at perpendicular directions. o Shear stresses at one direction do not cause shear strains at perpendicular directions.

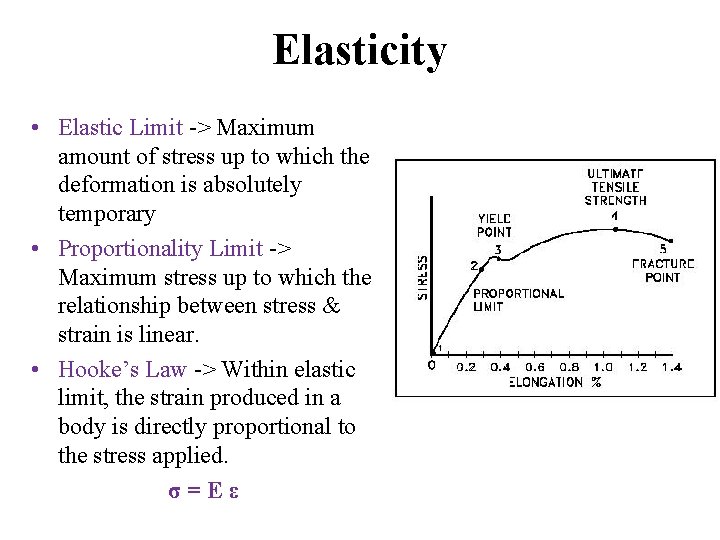

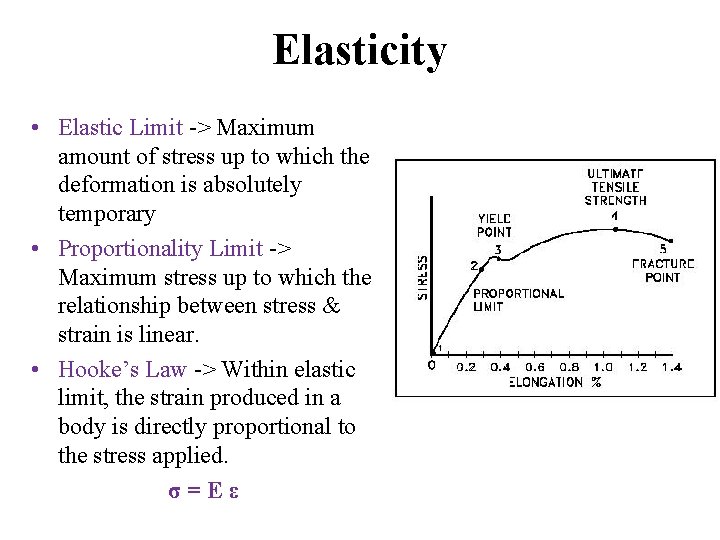

Elasticity • Elastic Limit -> Maximum amount of stress up to which the deformation is absolutely temporary • Proportionality Limit -> Maximum stress up to which the relationship between stress & strain is linear. • Hooke’s Law -> Within elastic limit, the strain produced in a body is directly proportional to the stress applied. σ=Eε

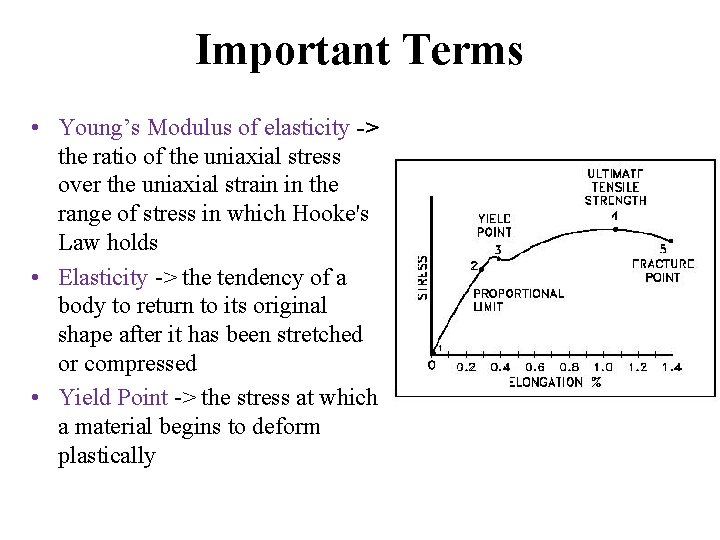

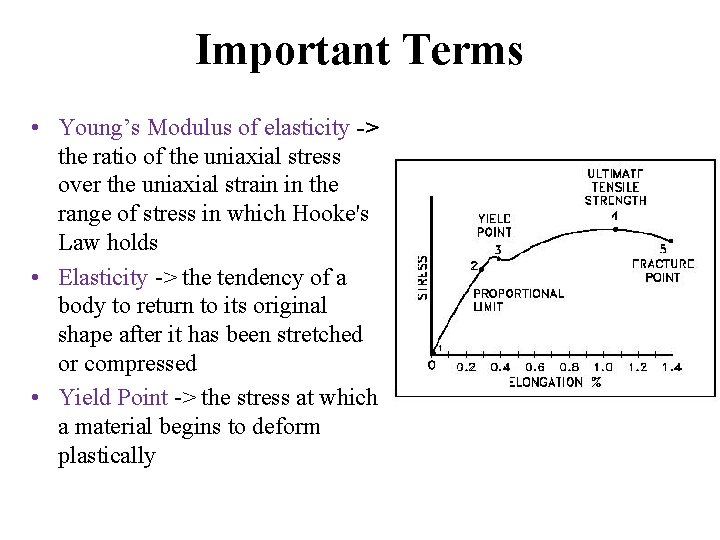

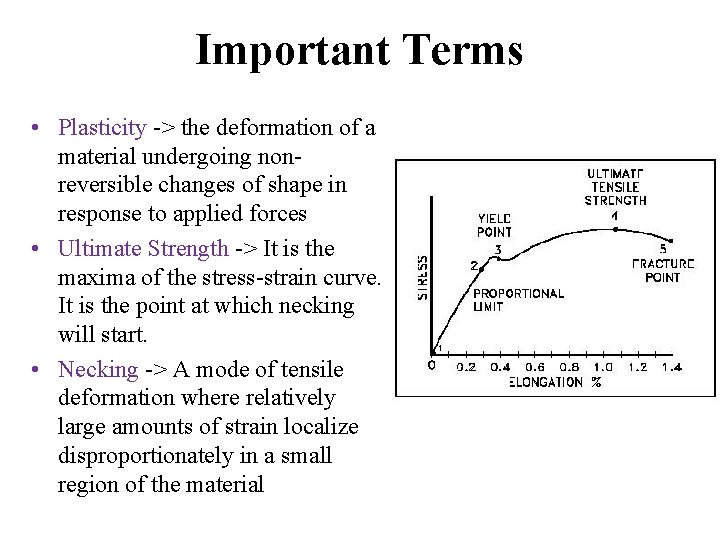

Important Terms • Young’s Modulus of elasticity -> the ratio of the uniaxial stress over the uniaxial strain in the range of stress in which Hooke's Law holds • Elasticity -> the tendency of a body to return to its original shape after it has been stretched or compressed • Yield Point -> the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically

Important Terms • Plasticity -> the deformation of a material undergoing nonreversible changes of shape in response to applied forces • Ultimate Strength -> It is the maxima of the stress-strain curve. It is the point at which necking will start. • Necking -> A mode of tensile deformation where relatively large amounts of strain localize disproportionately in a small region of the material

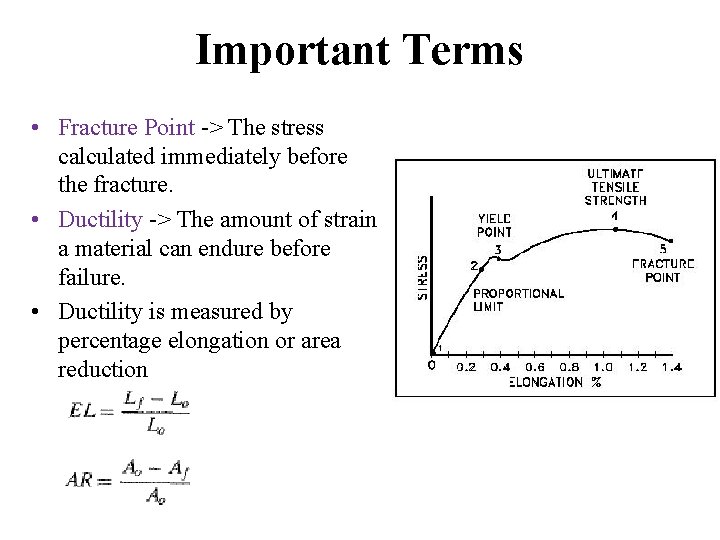

Important Terms • Fracture Point -> The stress calculated immediately before the fracture. • Ductility -> The amount of strain a material can endure before failure. • Ductility is measured by percentage elongation or area reduction

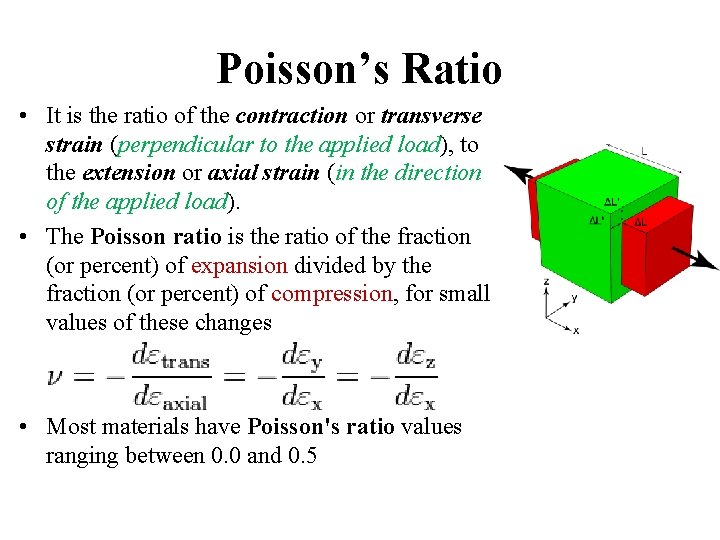

Poisson’s Ratio • It is the ratio of the contraction or transverse strain (perpendicular to the applied load), to the extension or axial strain (in the direction of the applied load). • The Poisson ratio is the ratio of the fraction (or percent) of expansion divided by the fraction (or percent) of compression, for small values of these changes • Most materials have Poisson's ratio values ranging between 0. 0 and 0. 5

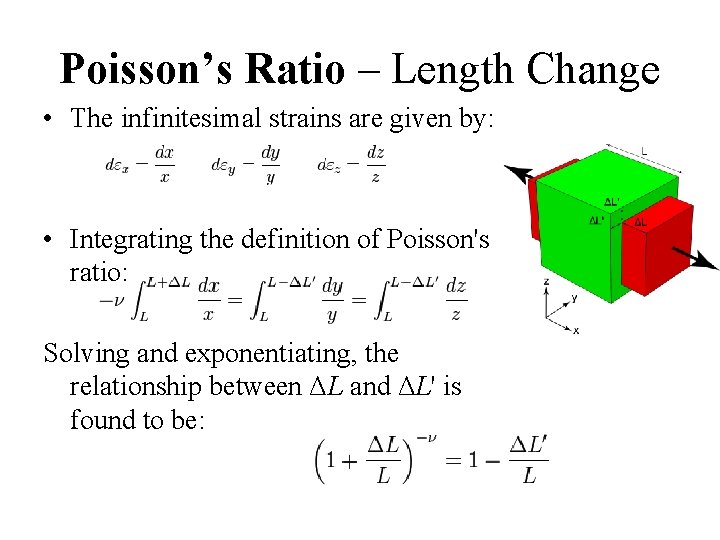

Poisson’s Ratio – Length Change • The infinitesimal strains are given by: • Integrating the definition of Poisson's ratio: Solving and exponentiating, the relationship between ΔL and ΔL' is found to be:

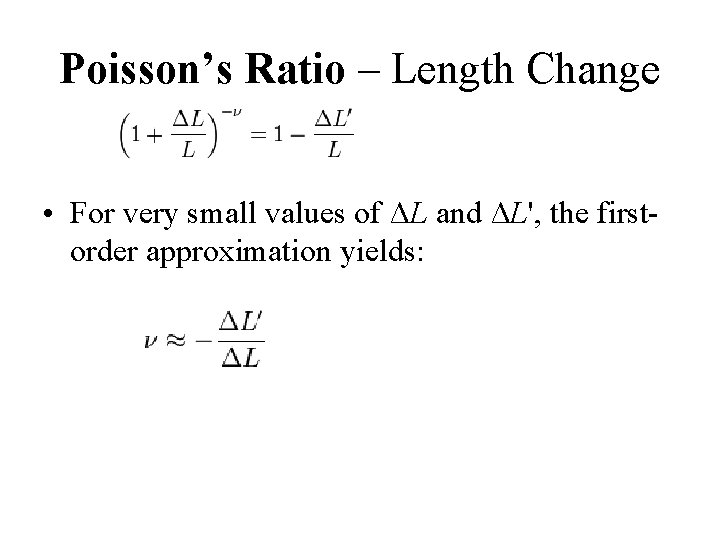

Poisson’s Ratio – Length Change • For very small values of ΔL and ΔL', the firstorder approximation yields:

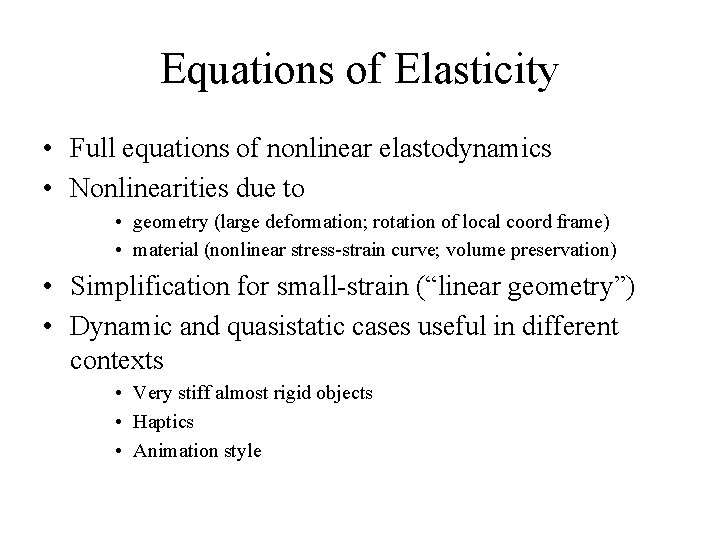

Poisson’s Ratio – Volumetric Change • Using V = L 3 and V + ΔV = (L + ΔL)(L − ΔL')2: • Using the derived relationship between ΔL and ΔL' • and for very small values of ΔL and ΔL', the first-order approximation yields:

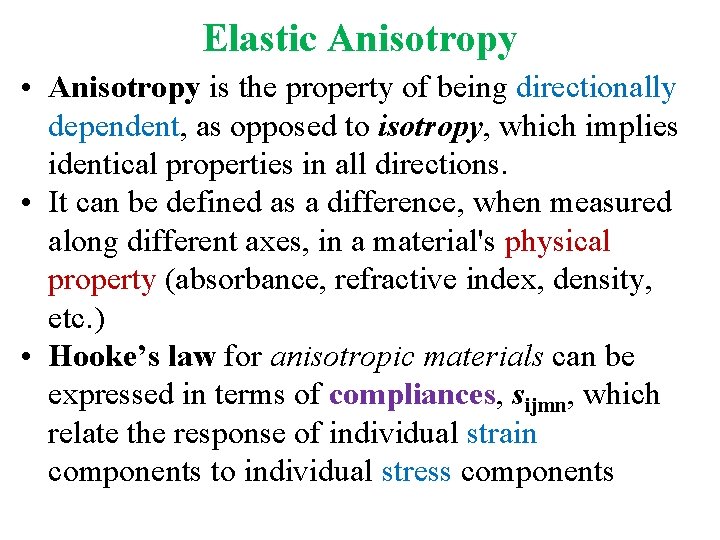

Elastic Anisotropy • Anisotropy is the property of being directionally dependent, as opposed to isotropy, which implies identical properties in all directions. • It can be defined as a difference, when measured along different axes, in a material's physical property (absorbance, refractive index, density, etc. ) • Hooke’s law for anisotropic materials can be expressed in terms of compliances, sijmn, which relate the response of individual strain components to individual stress components

Elastic Anisotropy • Every strain component depends linearly on the stress components eij = sijmnσmn • The compliances, sijmn, form a fourth-order tensor • Simplification of the Hooke’s Law relations -> σmn = σnm and γij = γji = 2 emn = 2 enm, • Hooke’s law becomes:

Elastic Anisotropy • Because it can be shown that sij = sji, further simplification results in (Compliance in 2 nd row, 1 st column is incorrect) • So there at most 21 independent compliances. • In the majority of cases, symmetry reduces the number of constants

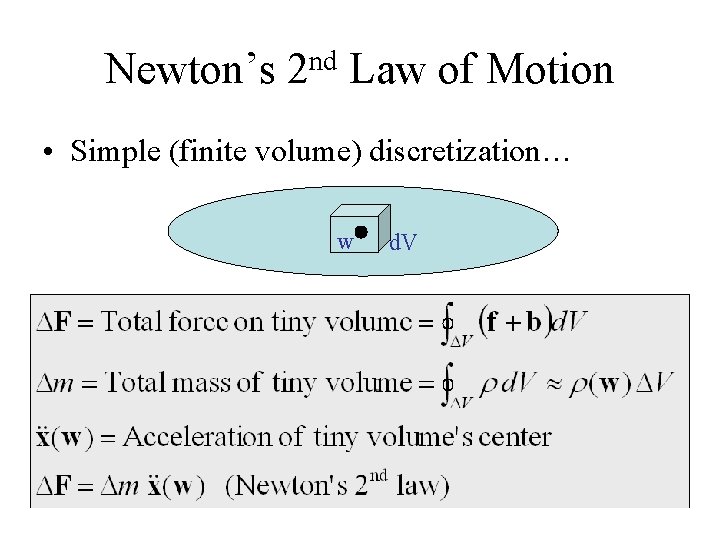

Equations of Elasticity • Full equations of nonlinear elastodynamics • Nonlinearities due to • geometry (large deformation; rotation of local coord frame) • material (nonlinear stress-strain curve; volume preservation) • Simplification for small-strain (“linear geometry”) • Dynamic and quasistatic cases useful in different contexts • Very stiff almost rigid objects • Haptics • Animation style

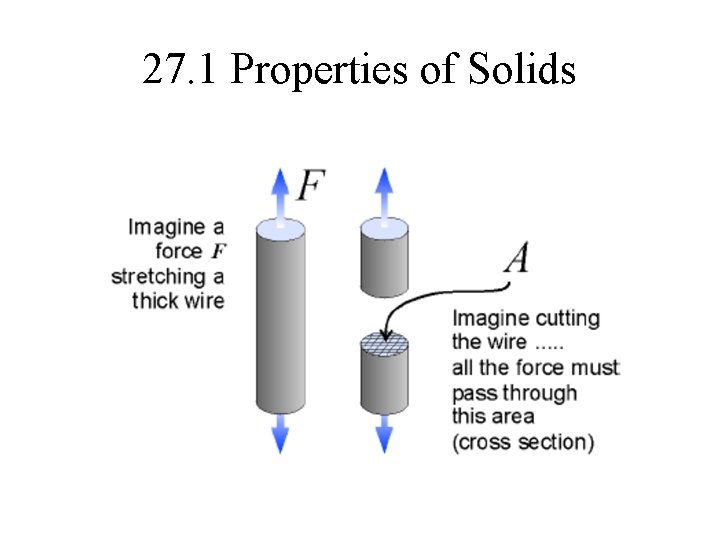

Stress Tensor • Describes forces acting inside an object n w d. A (tiny area)

Newton’s 2 nd Law of Motion • Simple (finite volume) discretization… w d. V

27. 1 Stress • The stress in a material is the ratio of the force acting through the material divided by the cross section area through which the force is carried. • The metric unit of stress is the pascal (Pa). • One pascal is equal to one newton of force per square meter of area (1 N/m 2). Stress (N/m 2) s=F A Force (N) Area (m 2)

27. 1 Properties of Solids

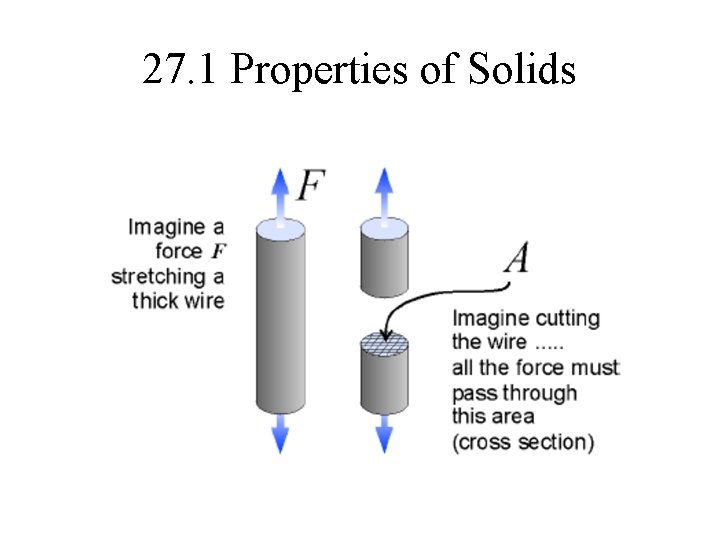

26. 1 Properties of Solids • A thicker wire can support more force at the same stress as a thinner wire because the cross section area is increased.

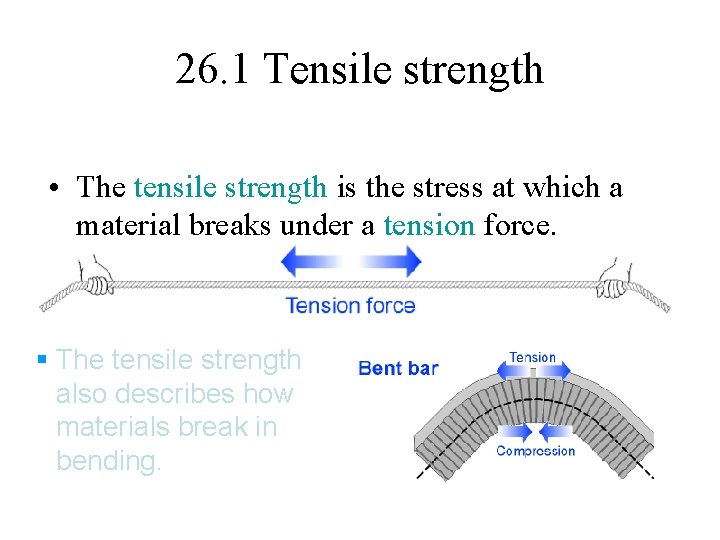

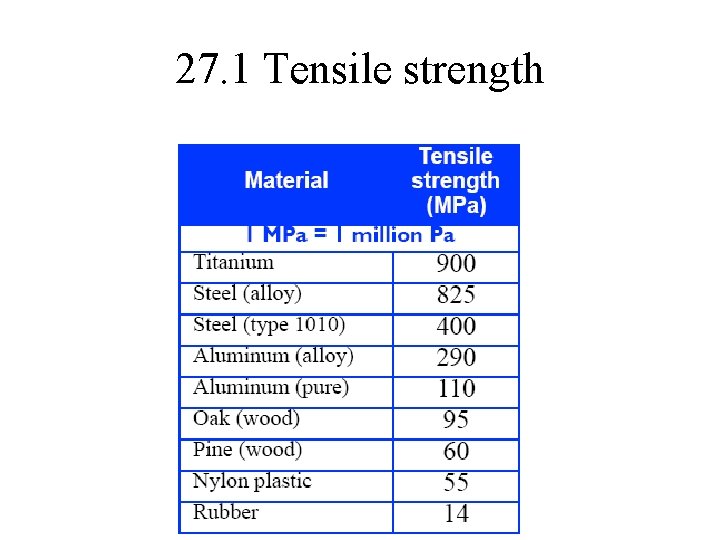

26. 1 Tensile strength • The tensile strength is the stress at which a material breaks under a tension force. § The tensile strength also describes how materials break in bending.

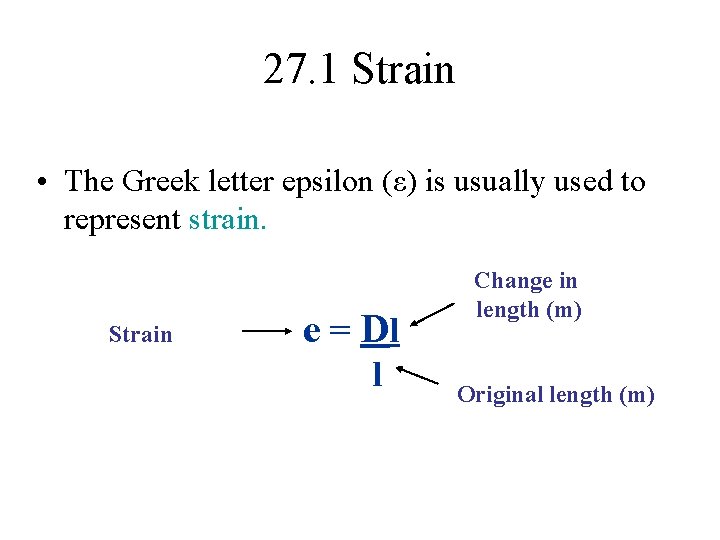

27. 1 Tensile strength

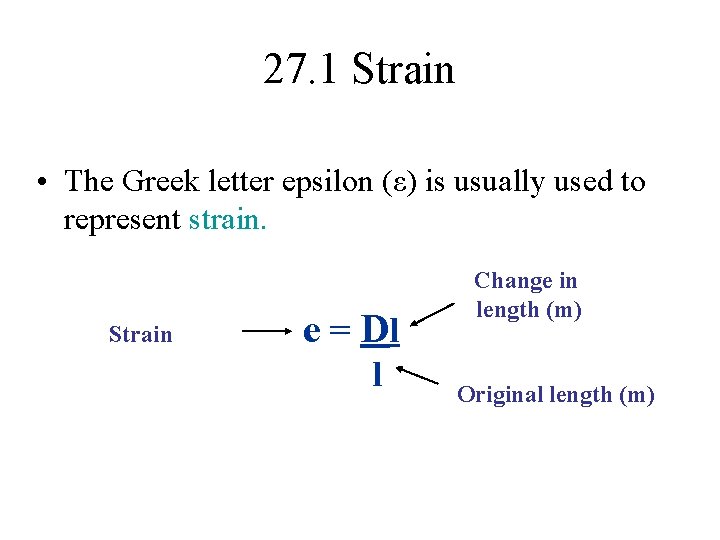

27. 1 Strain • The Greek letter epsilon (ε) is usually used to represent strain. Strain e = Dl l Change in length (m) Original length (m)

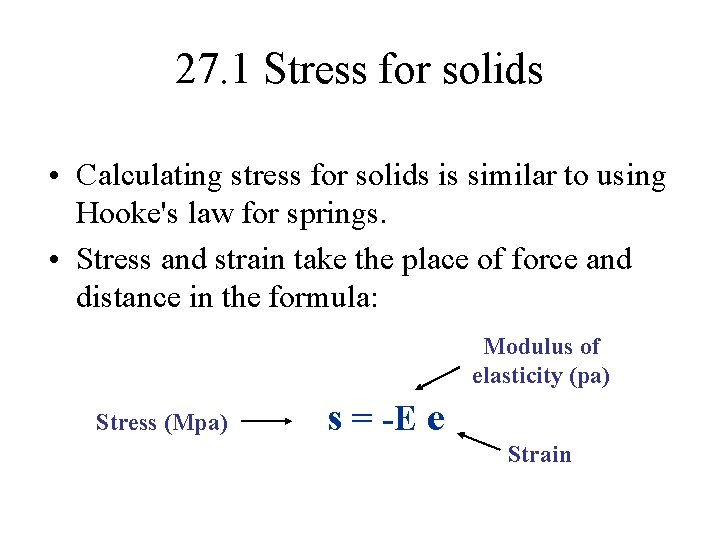

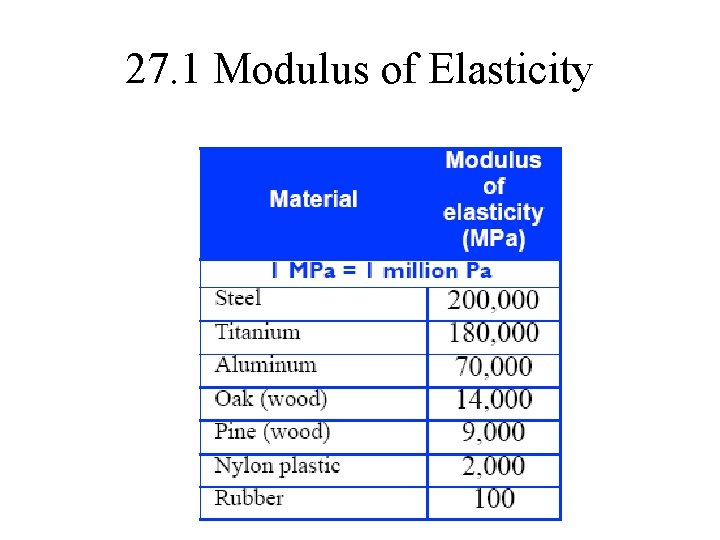

27. 1 Properties of solids • The modulus of elasticity plays the role of the spring constant for solids. • A material is elastic when it can take a large amount of strain before breaking. • A brittle material

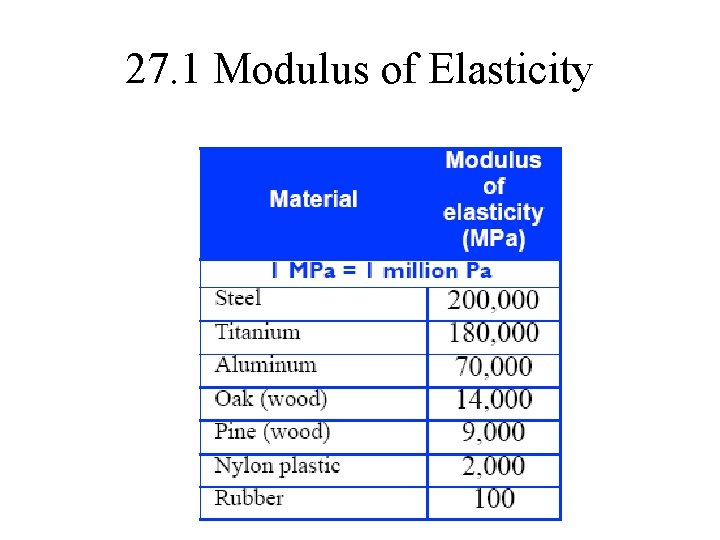

27. 1 Modulus of Elasticity

27. 1 Stress for solids • Calculating stress for solids is similar to using Hooke's law for springs. • Stress and strain take the place of force and distance in the formula: Modulus of elasticity (pa) Stress (Mpa) s = -E e Strain