ANALYSIS AND DESIGN OF ALGORITHMS UNITI CHAPTER 2

- Slides: 42

ANALYSIS AND DESIGN OF ALGORITHMS UNIT-I CHAPTER 2: FUNDAMENTALS OF THE ANALYSIS OF ALGORITHM EFFICIENCY

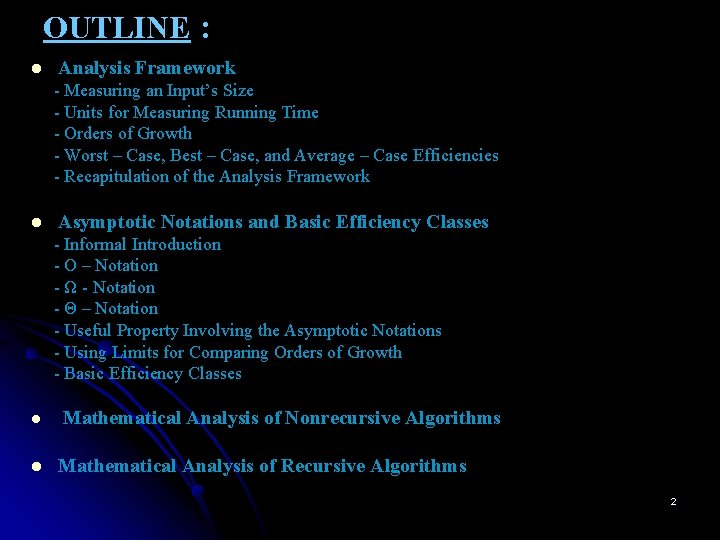

OUTLINE : l Analysis Framework - Measuring an Input’s Size - Units for Measuring Running Time - Orders of Growth - Worst – Case, Best – Case, and Average – Case Efficiencies - Recapitulation of the Analysis Framework l Asymptotic Notations and Basic Efficiency Classes - Informal Introduction - O – Notation - Ω - Notation - Θ – Notation - Useful Property Involving the Asymptotic Notations - Using Limits for Comparing Orders of Growth - Basic Efficiency Classes l l Mathematical Analysis of Nonrecursive Algorithms Mathematical Analysis of Recursive Algorithms 2

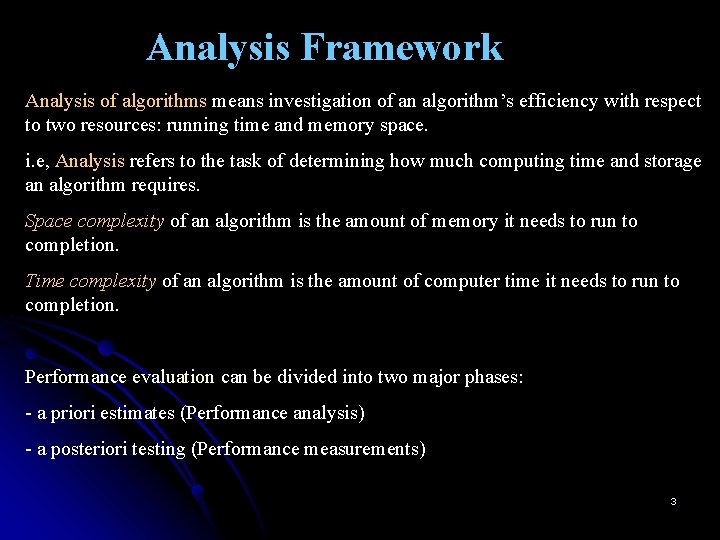

Analysis Framework Analysis of algorithms means investigation of an algorithm’s efficiency with respect to two resources: running time and memory space. i. e, Analysis refers to the task of determining how much computing time and storage an algorithm requires. Space complexity of an algorithm is the amount of memory it needs to run to completion. Time complexity of an algorithm is the amount of computer time it needs to run to completion. Performance evaluation can be divided into two major phases: - a priori estimates (Performance analysis) - a posteriori testing (Performance measurements) 3

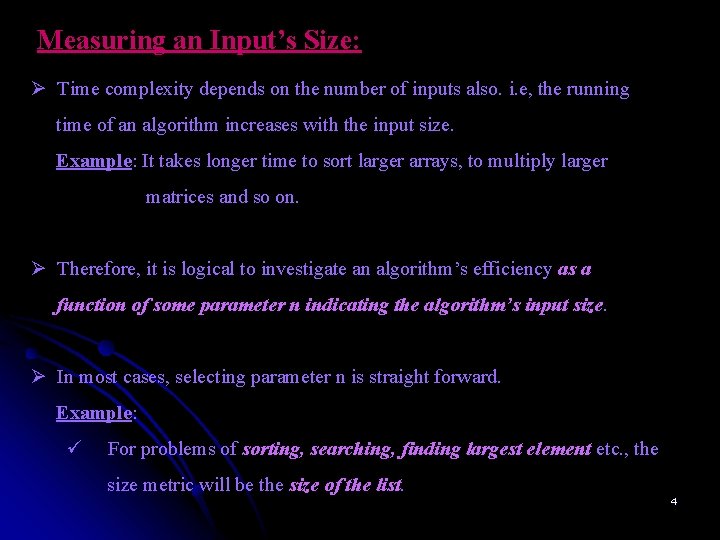

Measuring an Input’s Size: Ø Time complexity depends on the number of inputs also. i. e, the running time of an algorithm increases with the input size. Example: It takes longer time to sort larger arrays, to multiply larger matrices and so on. Ø Therefore, it is logical to investigate an algorithm’s efficiency as a function of some parameter n indicating the algorithm’s input size. Ø In most cases, selecting parameter n is straight forward. Example: ü For problems of sorting, searching, finding largest element etc. , the size metric will be the size of the list. 4

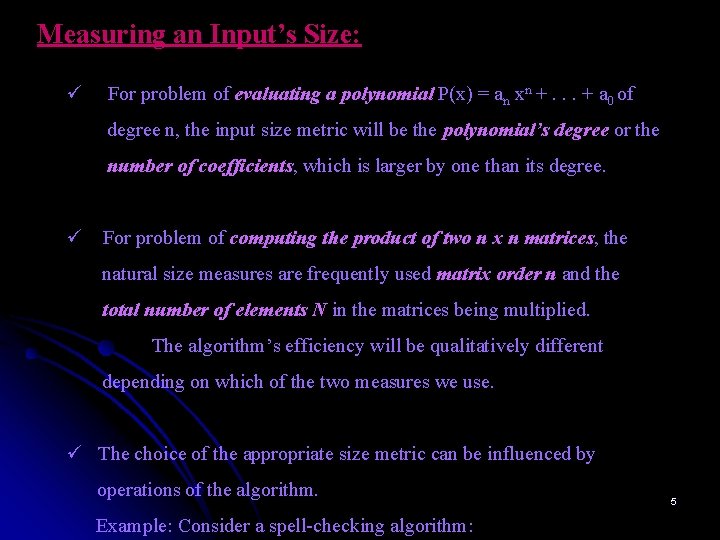

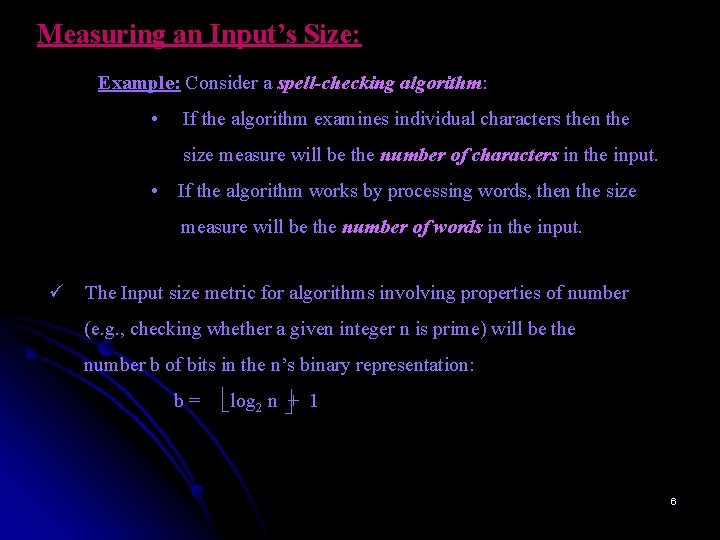

Measuring an Input’s Size: ü For problem of evaluating a polynomial P(x) = an xn +. . . + a 0 of degree n, the input size metric will be the polynomial’s degree or the number of coefficients, which is larger by one than its degree. ü For problem of computing the product of two n x n matrices, the natural size measures are frequently used matrix order n and the total number of elements N in the matrices being multiplied. The algorithm’s efficiency will be qualitatively different depending on which of the two measures we use. ü The choice of the appropriate size metric can be influenced by operations of the algorithm. Example: Consider a spell-checking algorithm: 5

Measuring an Input’s Size: Example: Consider a spell-checking algorithm: • If the algorithm examines individual characters then the size measure will be the number of characters in the input. • If the algorithm works by processing words, then the size measure will be the number of words in the input. ü The Input size metric for algorithms involving properties of number (e. g. , checking whether a given integer n is prime) will be the number b of bits in the n’s binary representation: b= log 2 n + 1 6

Units for Measuring Running Time: Ø Some standard unit of time measurements – a second, a millisecond, and so on can be used to measure the running time of a program implementing the algorithm. Ø The obvious drawbacks to above approach are: • dependence on the speed of a particular computer, • dependence on the quality of a program implementing the algorithm, • compiler used in generating the machine code, • difficulty of clocking the actual running time of the program. Ø For measuring the algorithm’s efficiency, we need to have a metric that does not depend on these hardware and software factors. 7

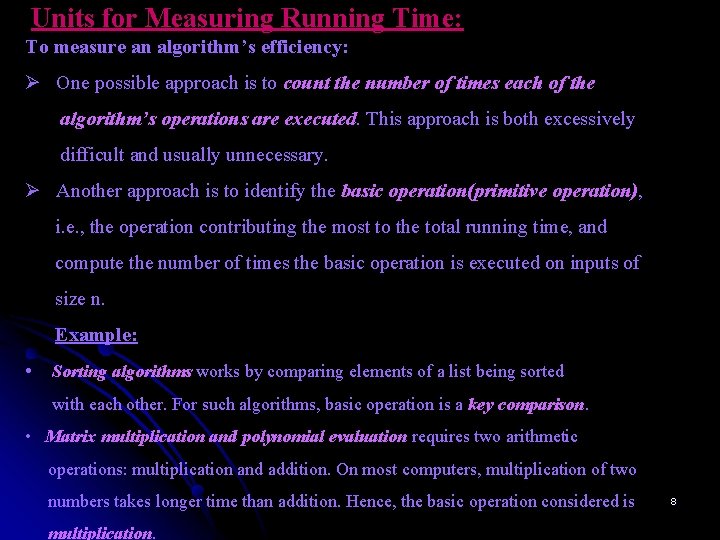

Units for Measuring Running Time: To measure an algorithm’s efficiency: Ø One possible approach is to count the number of times each of the algorithm’s operations are executed. This approach is both excessively difficult and usually unnecessary. Ø Another approach is to identify the basic operation(primitive operation), i. e. , the operation contributing the most to the total running time, and compute the number of times the basic operation is executed on inputs of size n. Example: • Sorting algorithms works by comparing elements of a list being sorted with each other. For such algorithms, basic operation is a key comparison. • Matrix multiplication and polynomial evaluation requires two arithmetic operations: multiplication and addition. On most computers, multiplication of two numbers takes longer time than addition. Hence, the basic operation considered is multiplication. 8

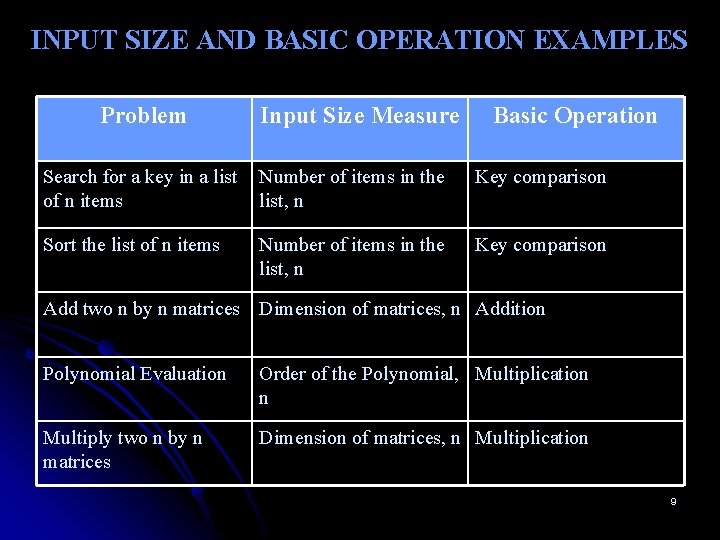

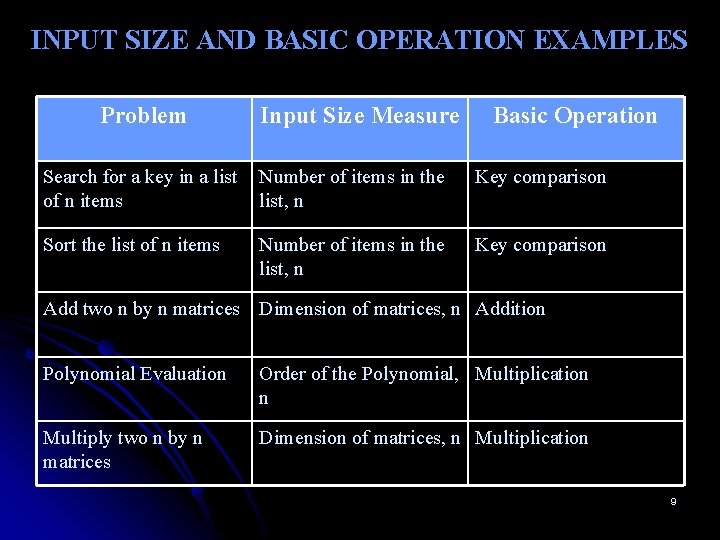

INPUT SIZE AND BASIC OPERATION EXAMPLES Problem Input Size Measure Basic Operation Search for a key in a list of n items Number of items in the list, n Key comparison Sort the list of n items Number of items in the list, n Key comparison Add two n by n matrices Dimension of matrices, n Addition Polynomial Evaluation Order of the Polynomial, Multiplication n Multiply two n by n matrices Dimension of matrices, n Multiplication 9

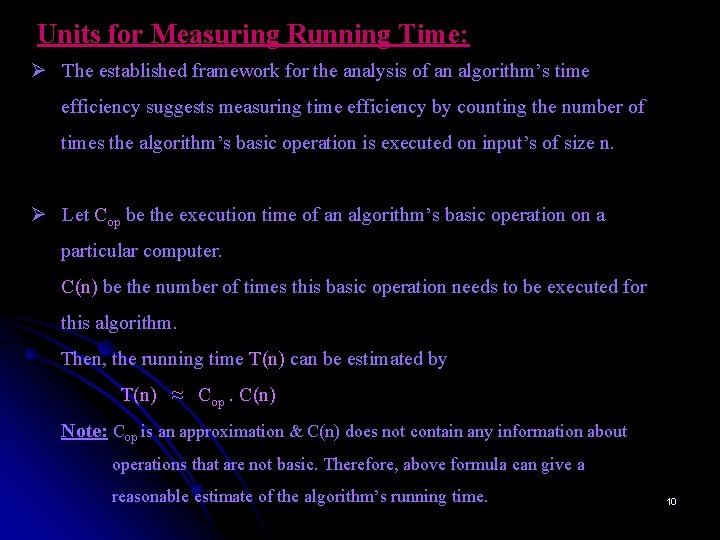

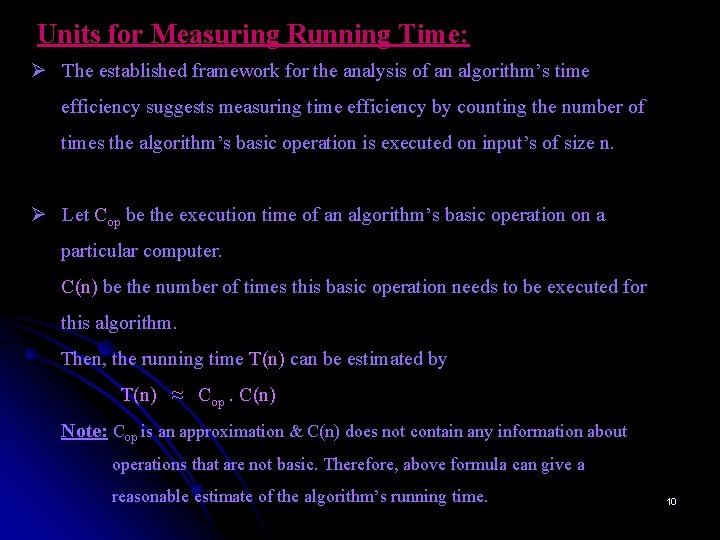

Units for Measuring Running Time: Ø The established framework for the analysis of an algorithm’s time efficiency suggests measuring time efficiency by counting the number of times the algorithm’s basic operation is executed on input’s of size n. Ø Let Cop be the execution time of an algorithm’s basic operation on a particular computer. C(n) be the number of times this basic operation needs to be executed for this algorithm. Then, the running time T(n) can be estimated by T(n) ≈ Cop. C(n) Note: Cop is an approximation & C(n) does not contain any information about operations that are not basic. Therefore, above formula can give a reasonable estimate of the algorithm’s running time. 10

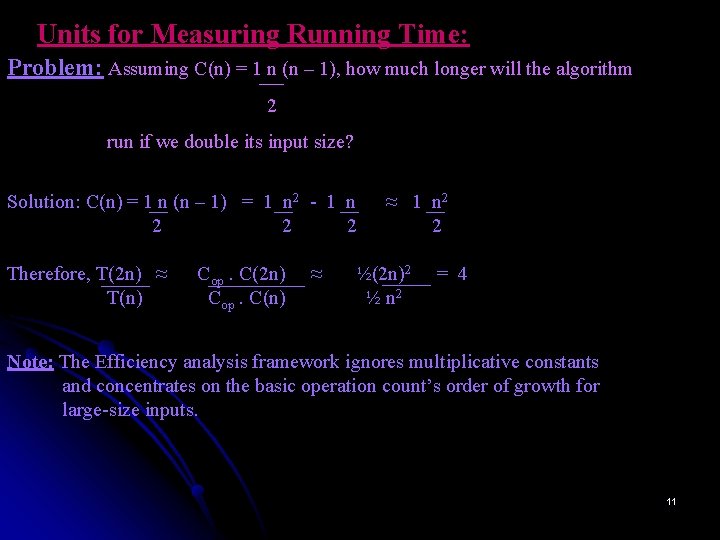

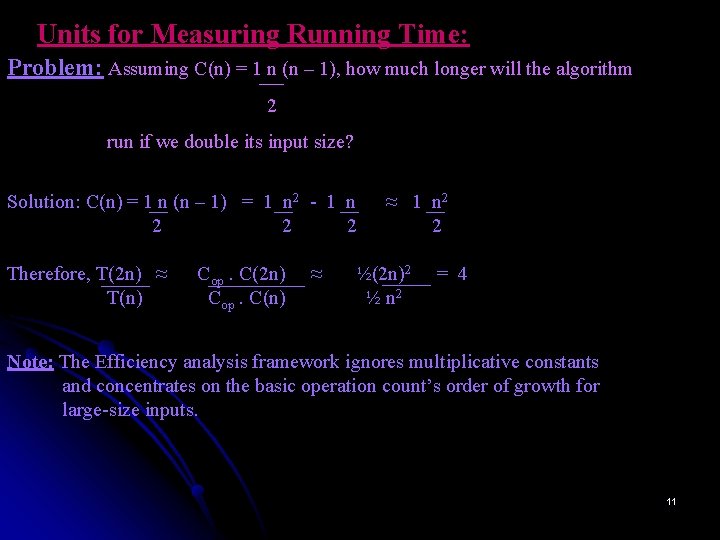

Units for Measuring Running Time: Problem: Assuming C(n) = 1 n (n – 1), how much longer will the algorithm 2 run if we double its input size? Solution: C(n) = 1 n (n – 1) = 1 n 2 - 1 n 2 2 2 Therefore, T(2 n) ≈ T(n) Cop. C(2 n) Cop. C(n) ≈ ≈ 1 n 2 2 ½(2 n)2 ½ n 2 = 4 Note: The Efficiency analysis framework ignores multiplicative constants and concentrates on the basic operation count’s order of growth for large-size inputs. 11

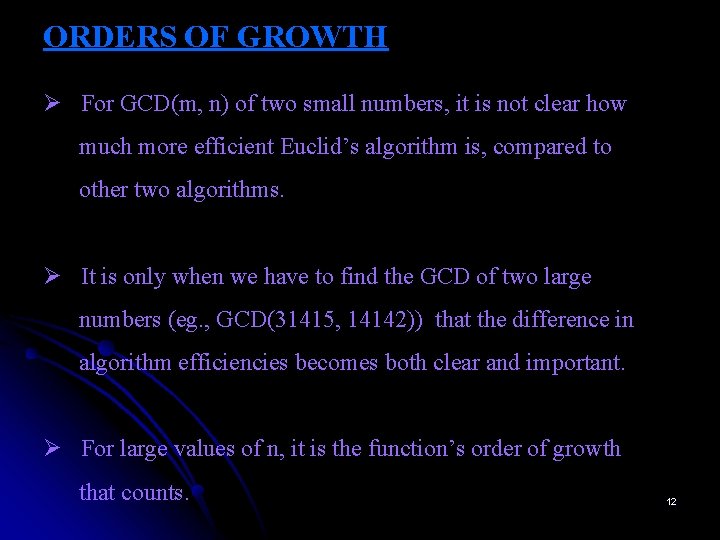

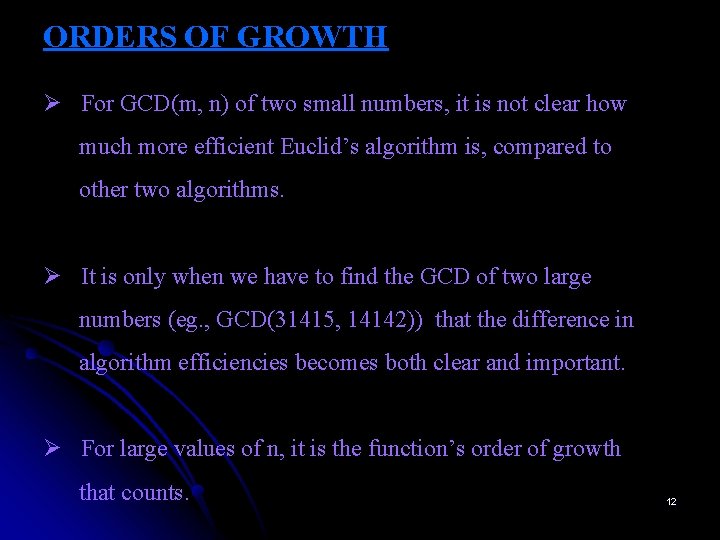

ORDERS OF GROWTH Ø For GCD(m, n) of two small numbers, it is not clear how much more efficient Euclid’s algorithm is, compared to other two algorithms. Ø It is only when we have to find the GCD of two large numbers (eg. , GCD(31415, 14142)) that the difference in algorithm efficiencies becomes both clear and important. Ø For large values of n, it is the function’s order of growth that counts. 12

ORDERS OF GROWTH n 10 102 103 104 105 106 log 2 n 3. 3 n n log 2 n n 2 n 3 2 n 101 3. 3 x 101 102 103 6. 6 102 6. 6 x 102 104 106 1. 3 x 1030 10 13 17 20 9. 3 x 10157 103 104 105 106 1. 0 x 104 1. 3 x 105 1. 7 x 106 2. 0 x 107 106 108 1010 1012 109 1012 1015 1018 n! 3. 6 x 106 Table: Values (some approximate) of several functions important for analysis of algorithms. 13

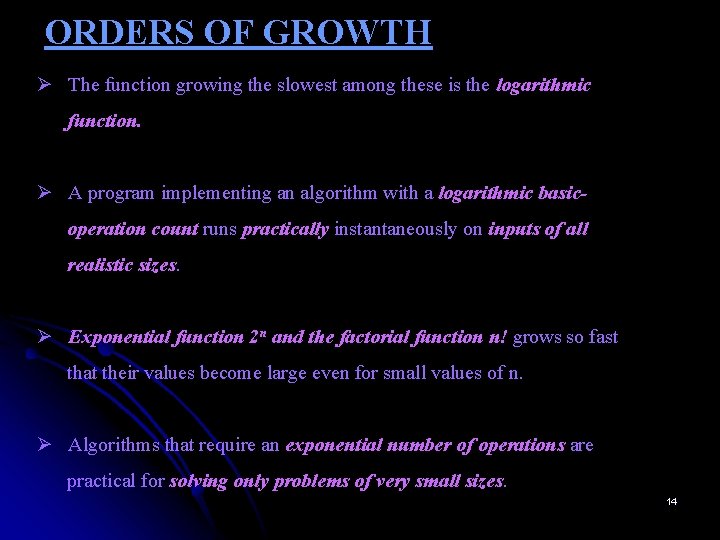

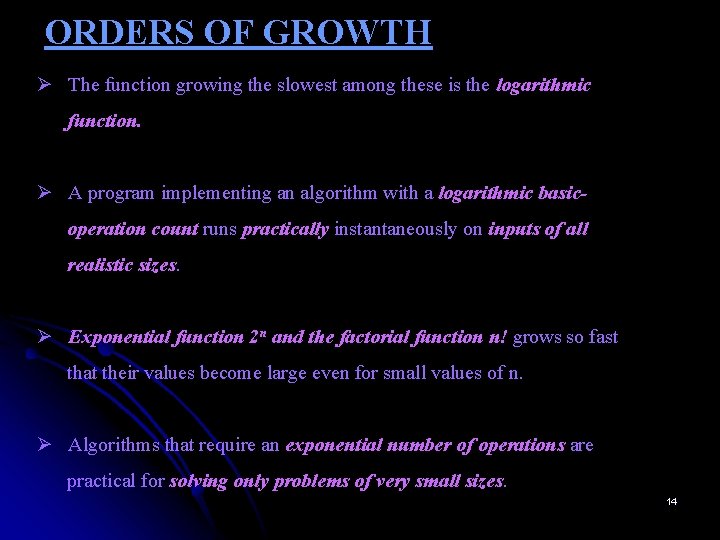

ORDERS OF GROWTH Ø The function growing the slowest among these is the logarithmic function. Ø A program implementing an algorithm with a logarithmic basicoperation count runs practically instantaneously on inputs of all realistic sizes. Ø Exponential function 2 n and the factorial function n! grows so fast that their values become large even for small values of n. Ø Algorithms that require an exponential number of operations are practical for solving only problems of very small sizes. 14

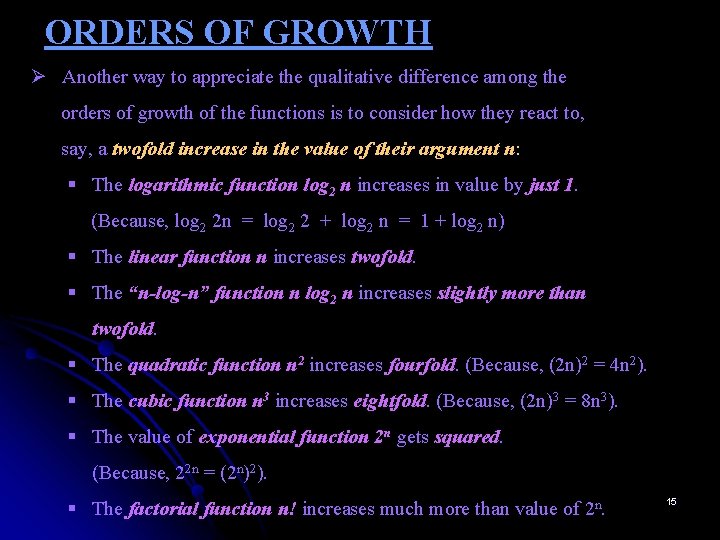

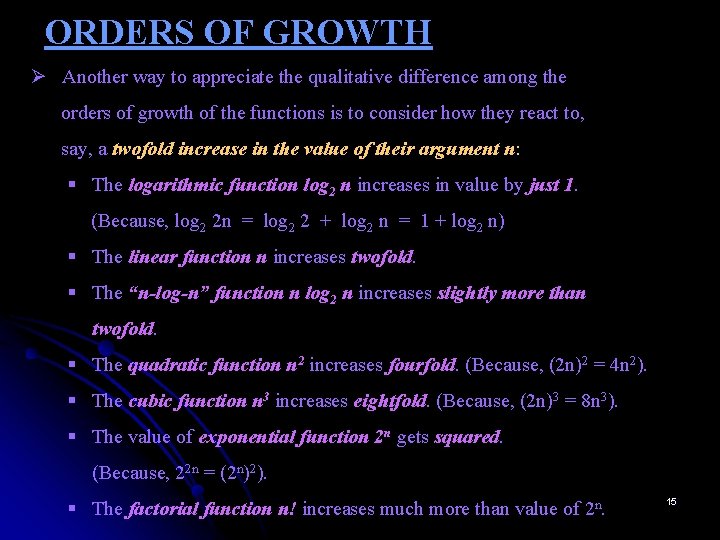

ORDERS OF GROWTH Ø Another way to appreciate the qualitative difference among the orders of growth of the functions is to consider how they react to, say, a twofold increase in the value of their argument n: § The logarithmic function log 2 n increases in value by just 1. (Because, log 2 2 n = log 2 2 + log 2 n = 1 + log 2 n) § The linear function n increases twofold. § The “n-log-n” function n log 2 n increases slightly more than twofold. § The quadratic function n 2 increases fourfold. (Because, (2 n)2 = 4 n 2). § The cubic function n 3 increases eightfold. (Because, (2 n)3 = 8 n 3). § The value of exponential function 2 n gets squared. (Because, 22 n = (2 n)2). § The factorial function n! increases much more than value of 2 n. 15

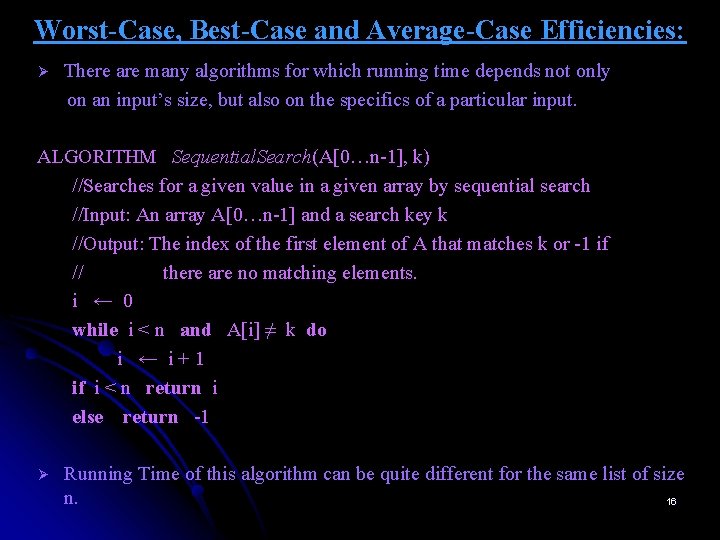

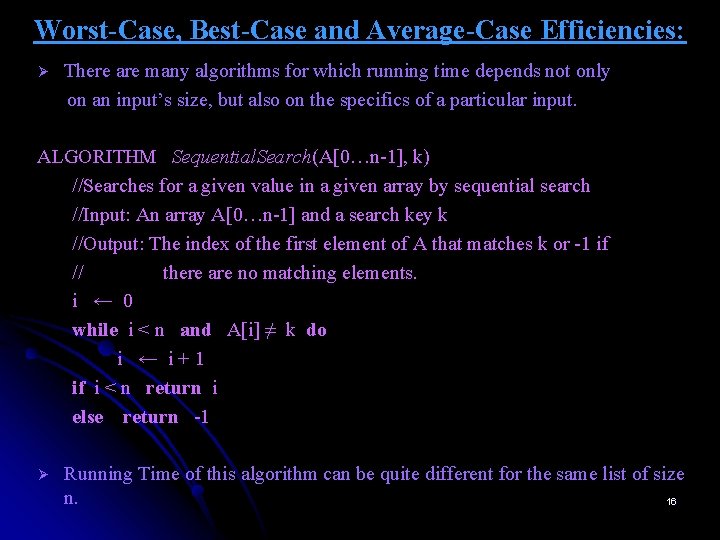

Worst-Case, Best-Case and Average-Case Efficiencies: Ø There are many algorithms for which running time depends not only on an input’s size, but also on the specifics of a particular input. ALGORITHM Sequential. Search(A[0…n-1], k) //Searches for a given value in a given array by sequential search //Input: An array A[0…n-1] and a search key k //Output: The index of the first element of A that matches k or -1 if // there are no matching elements. i ← 0 while i < n and A[i] ≠ k do i ← i+1 if i < n return i else return -1 Ø Running Time of this algorithm can be quite different for the same list of size n. 16

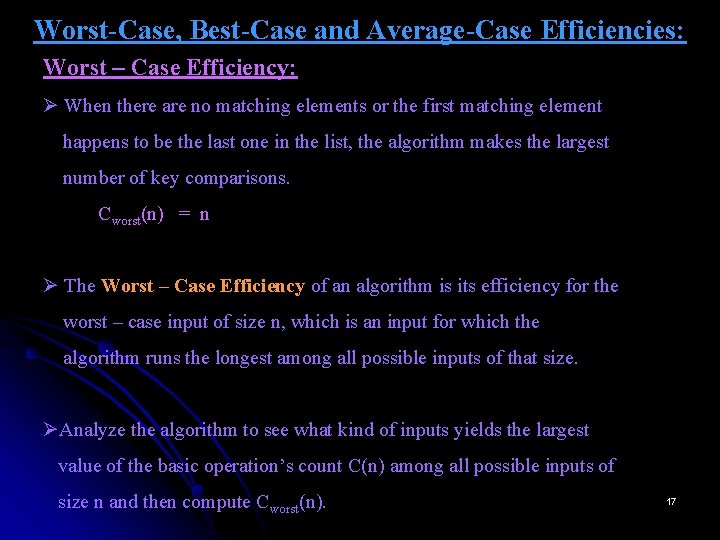

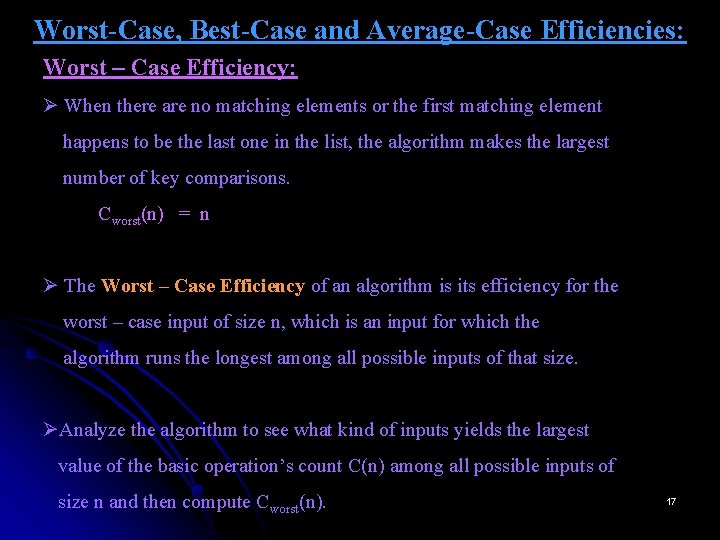

Worst-Case, Best-Case and Average-Case Efficiencies: Worst – Case Efficiency: Ø When there are no matching elements or the first matching element happens to be the last one in the list, the algorithm makes the largest number of key comparisons. Cworst(n) = n Ø The Worst – Case Efficiency of an algorithm is its efficiency for the worst – case input of size n, which is an input for which the algorithm runs the longest among all possible inputs of that size. ØAnalyze the algorithm to see what kind of inputs yields the largest value of the basic operation’s count C(n) among all possible inputs of size n and then compute Cworst(n). 17

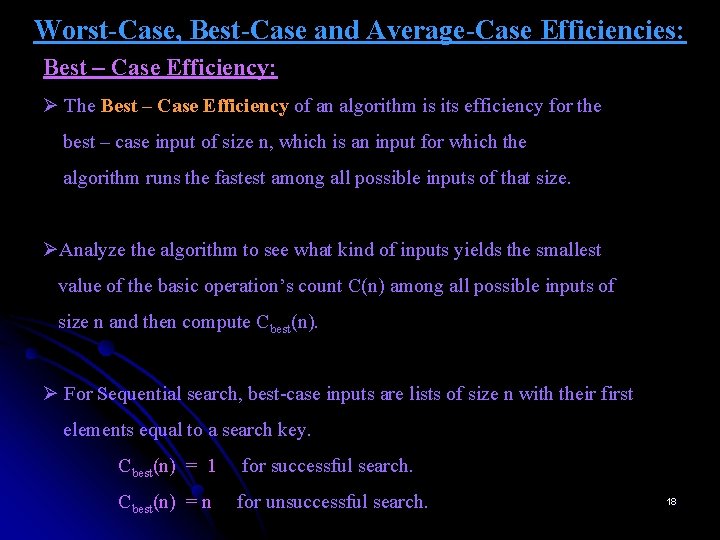

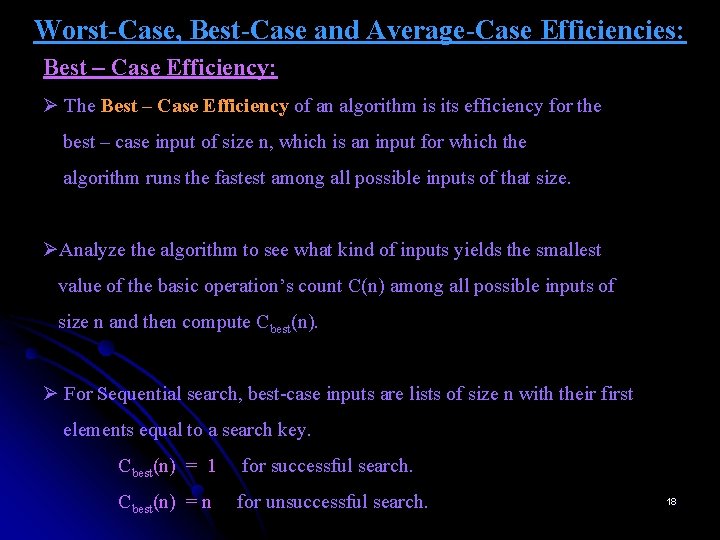

Worst-Case, Best-Case and Average-Case Efficiencies: Best – Case Efficiency: Ø The Best – Case Efficiency of an algorithm is its efficiency for the best – case input of size n, which is an input for which the algorithm runs the fastest among all possible inputs of that size. ØAnalyze the algorithm to see what kind of inputs yields the smallest value of the basic operation’s count C(n) among all possible inputs of size n and then compute Cbest(n). Ø For Sequential search, best-case inputs are lists of size n with their first elements equal to a search key. Cbest(n) = 1 for successful search. Cbest(n) = n for unsuccessful search. 18

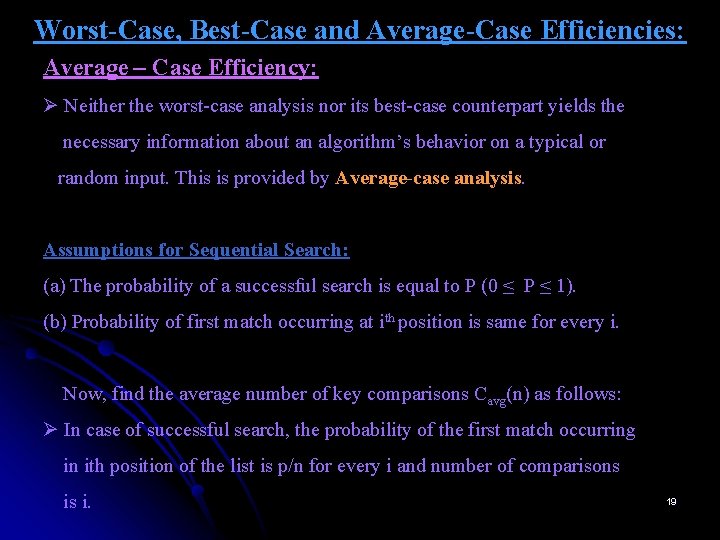

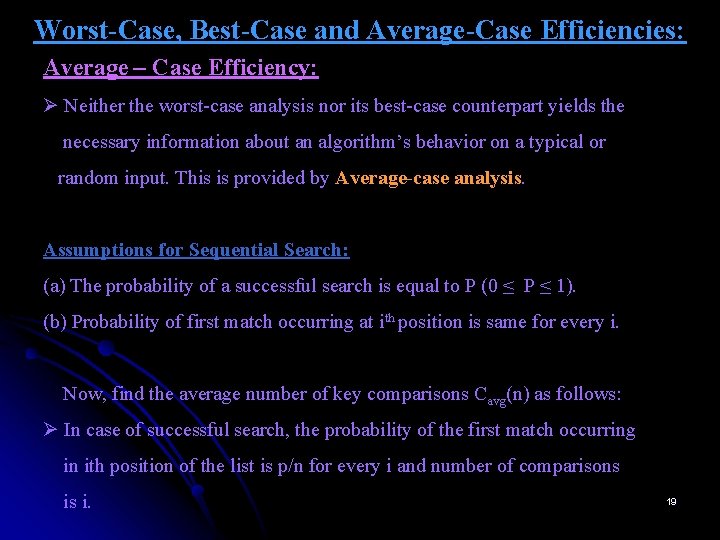

Worst-Case, Best-Case and Average-Case Efficiencies: Average – Case Efficiency: Ø Neither the worst-case analysis nor its best-case counterpart yields the necessary information about an algorithm’s behavior on a typical or random input. This is provided by Average-case analysis. Assumptions for Sequential Search: (a) The probability of a successful search is equal to P (0 ≤ P ≤ 1). (b) Probability of first match occurring at ith position is same for every i. Now, find the average number of key comparisons Cavg(n) as follows: Ø In case of successful search, the probability of the first match occurring in ith position of the list is p/n for every i and number of comparisons is i. 19

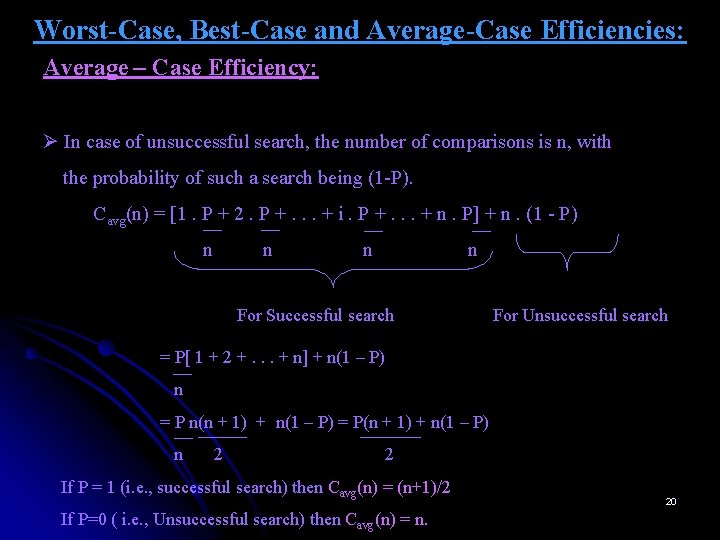

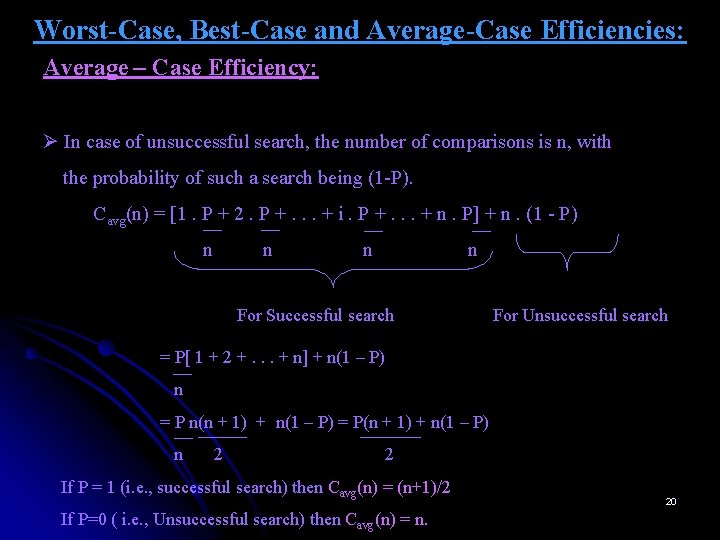

Worst-Case, Best-Case and Average-Case Efficiencies: Average – Case Efficiency: Ø In case of unsuccessful search, the number of comparisons is n, with the probability of such a search being (1 -P). Cavg(n) = [1. P + 2. P +. . . + i. P +. . . + n. P] + n. (1 - P) n n For Successful search For Unsuccessful search = P[ 1 + 2 +. . . + n] + n(1 – P) n = P n(n + 1) + n(1 – P) = P(n + 1) + n(1 – P) n 2 2 If P = 1 (i. e. , successful search) then Cavg(n) = (n+1)/2 If P=0 ( i. e. , Unsuccessful search) then Cavg(n) = n. 20

RECAPITULATION OF THE ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK v Both time and space efficiencies are measured as functions of the algorithm’s input size. v Time efficiency is measured by counting the number of times the algorithm’s basic operation is executed. v The efficiencies of some algorithms may differ significantly for inputs of the same size. For such algorithms, we need to distinguish between the worstcase, average-case, and best-case efficiencies. v The framework’s primary interest lies in the order of growth of the algorithm’s running time as its input size goes to infinity. 21

ASYMPTOTIC NOTATIONS Ø The Efficiency analysis framework concentrates on the order of growth of an algorithm’s basic operation count as the principal indicator of the algorithm’s efficiency. Ø To Compare and rank the order of growth of algorithm’s basic operation count, computer scientists use three notations: O( Big oh), Ω( Big omega), and Θ(Big theta). Ø In the following discussion, t(n) and g(n) can be any two nonnegative functions defined on the set of natural numbers. Ø t(n) will be an algorithm’s running time (usually indicated by its basic operation count C(n)), and g(n) will be some simple function to compare the count with. 22

INFORMAL INTRODUCTION TO ASYMPTOTIC NOTATIONS Ø Informally, O(g(n)) is the set of all functions with a smaller or same order of growth as g(n) (to within a constant multiple, as n goes to infinity). Examples: v n Є O(n 2) , 100 n + 5 Є O(n 2) The above two functions are linear and hence have a smaller order of growth than g(n) = n 2. v 1 n(n – 1) Є O(n 2) 2 The above function is quadratic and hence has the same order of growth as g(n) = n 2. Note: n 3 Є O(n 2), 0. 00001 n 3 Є O(n 2), n 4 + n + 1 Є O(n 2). Functions n 3 and 0. 00001 n 3 are both cubic and hence have a higher order of growth than n 2. Fourth-degree polynomial n 4 + n + 1 also has higher order of growth than n 2. 23

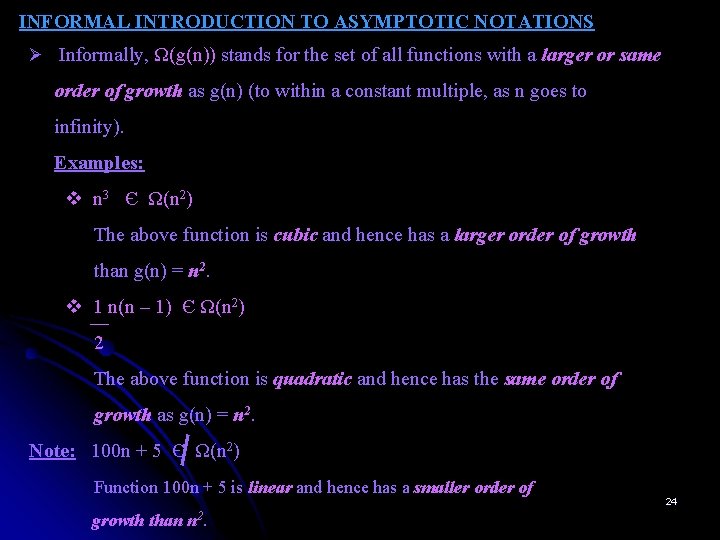

INFORMAL INTRODUCTION TO ASYMPTOTIC NOTATIONS Ø Informally, Ω(g(n)) stands for the set of all functions with a larger or same order of growth as g(n) (to within a constant multiple, as n goes to infinity). Examples: v n 3 Є Ω(n 2) The above function is cubic and hence has a larger order of growth than g(n) = n 2. v 1 n(n – 1) Є Ω(n 2) 2 The above function is quadratic and hence has the same order of growth as g(n) = n 2. Note: 100 n + 5 Є Ω(n 2) Function 100 n + 5 is linear and hence has a smaller order of growth than n 2. 24

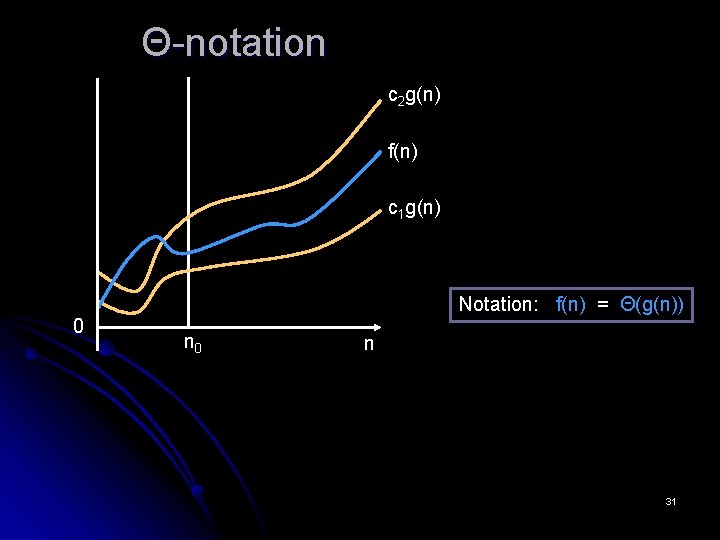

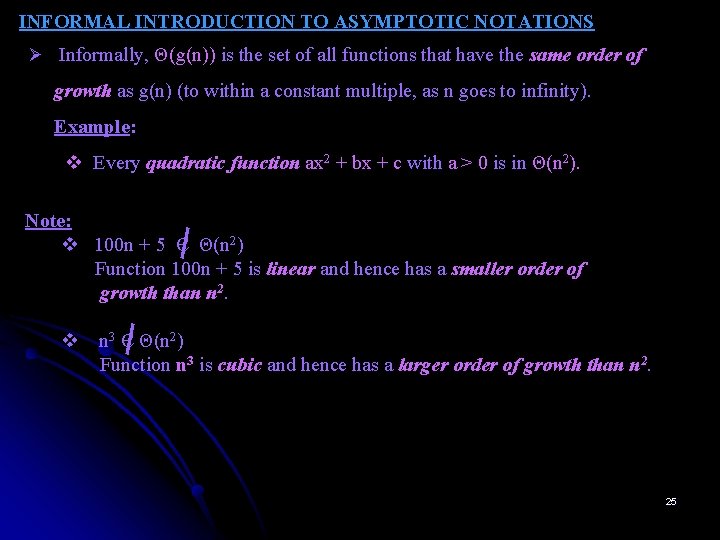

INFORMAL INTRODUCTION TO ASYMPTOTIC NOTATIONS Ø Informally, Θ(g(n)) is the set of all functions that have the same order of growth as g(n) (to within a constant multiple, as n goes to infinity). Example: v Every quadratic function ax 2 + bx + c with a > 0 is in Θ(n 2). Note: v 100 n + 5 Є Θ(n 2) Function 100 n + 5 is linear and hence has a smaller order of growth than n 2. v n 3 Є Θ(n 2) Function n 3 is cubic and hence has a larger order of growth than n 2. 25

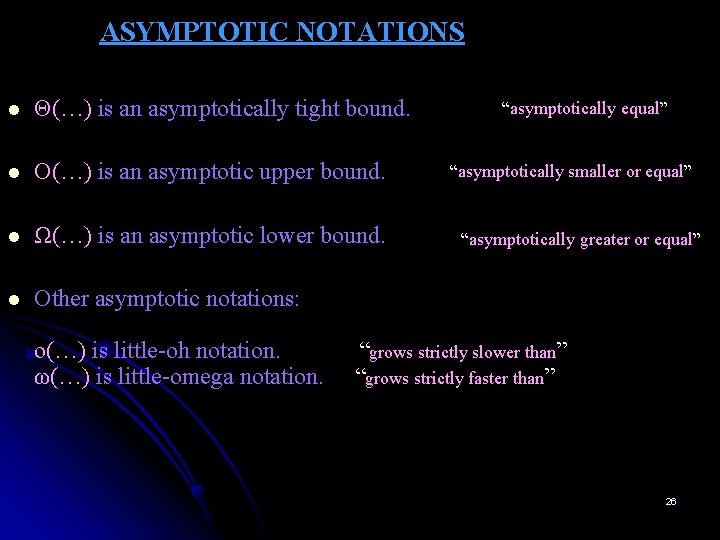

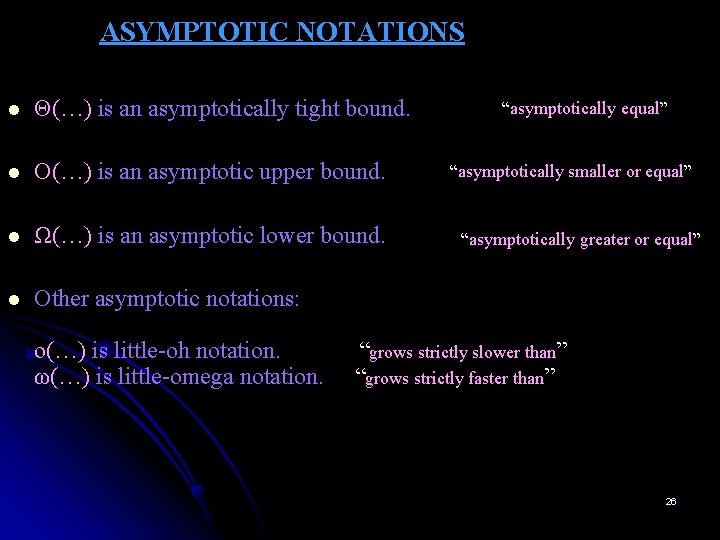

ASYMPTOTIC NOTATIONS l Θ(…) is an asymptotically tight bound. l O(…) is an asymptotic upper bound. l Ω(…) is an asymptotic lower bound. l Other asymptotic notations: o(…) is little-oh notation. ω(…) is little-omega notation. “asymptotically equal” “asymptotically smaller or equal” “asymptotically greater or equal” “grows strictly slower than” “grows strictly faster than” 26

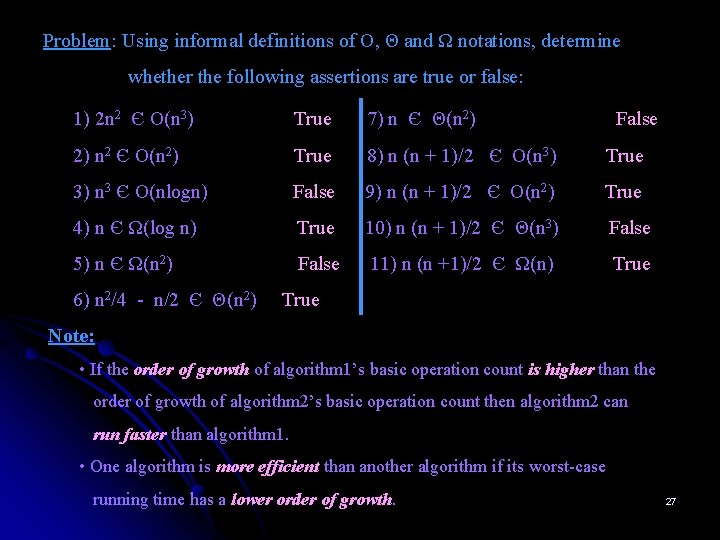

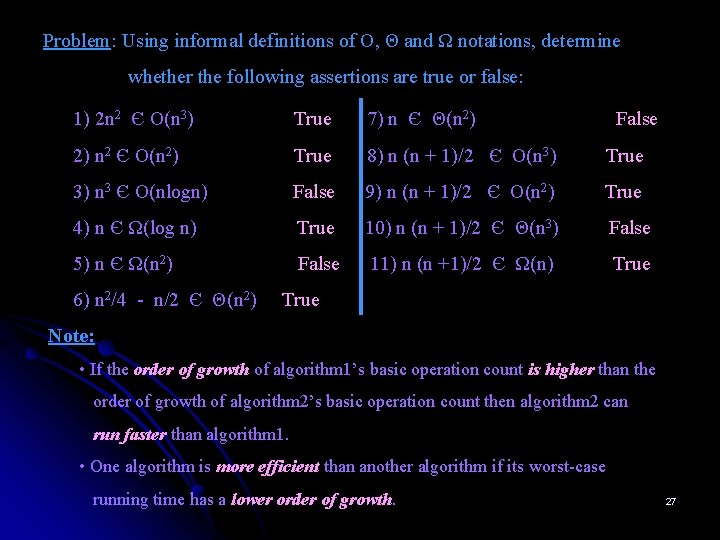

Problem: Using informal definitions of O, Θ and Ω notations, determine whether the following assertions are true or false: 1) 2 n 2 Є O(n 3) True 7) n Є Θ(n 2) 2) n 2 Є O(n 2) True 8) n (n + 1)/2 Є O(n 3) True 3) n 3 Є O(nlogn) False 9) n (n + 1)/2 Є O(n 2) True 4) n Є Ω(log n) True 10) n (n + 1)/2 Є Θ(n 3) False 5) n Є Ω(n 2) False 11) n (n +1)/2 Є Ω(n) True 6) n 2/4 - n/2 Є Θ(n 2) False True Note: • If the order of growth of algorithm 1’s basic operation count is higher than the order of growth of algorithm 2’s basic operation count then algorithm 2 can run faster than algorithm 1. • One algorithm is more efficient than another algorithm if its worst-case running time has a lower order of growth. 27

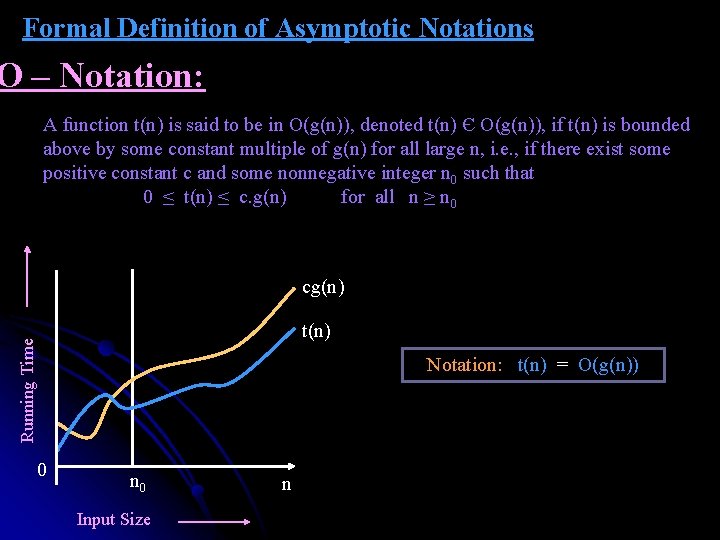

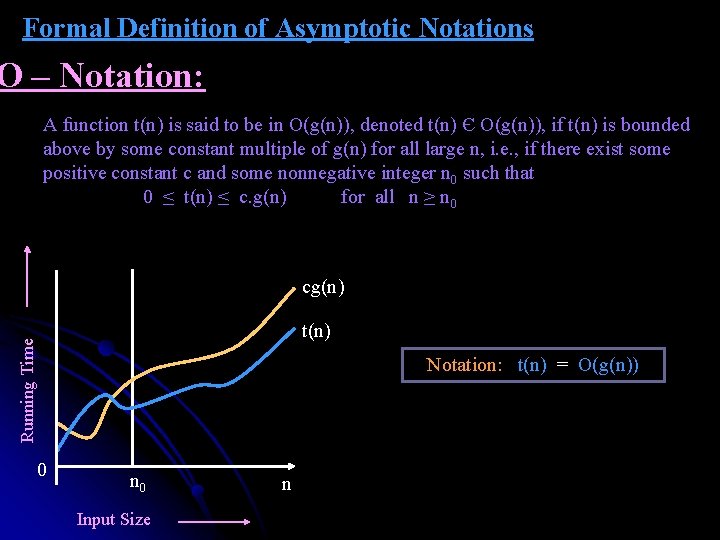

Formal Definition of Asymptotic Notations O – Notation: A function t(n) is said to be in O(g(n)), denoted t(n) Є O(g(n)), if t(n) is bounded above by some constant multiple of g(n) for all large n, i. e. , if there exist some positive constant c and some nonnegative integer n 0 such that 0 ≤ t(n) ≤ c. g(n) for all n ≥ n 0 cg(n) Running Time t(n) Notation: t(n) = O(g(n)) 0 n 0 Input Size n

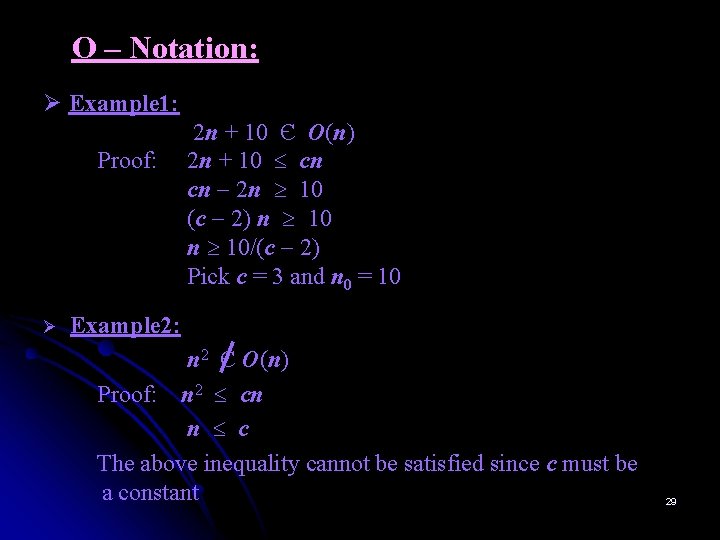

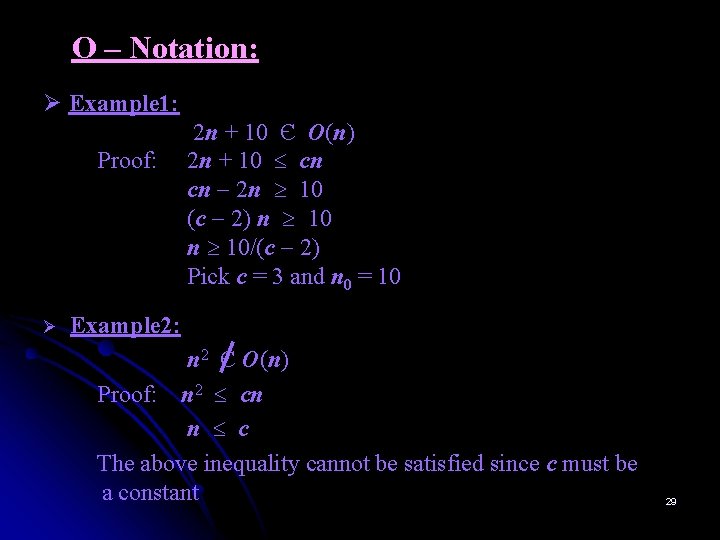

O – Notation: Ø Example 1: Proof: Ø 2 n + 10 Є O(n) 2 n + 10 cn cn 2 n 10 (c 2) n 10/(c 2) Pick c = 3 and n 0 = 10 Example 2: n 2 Є O(n) Proof: n 2 cn n c The above inequality cannot be satisfied since c must be a constant 29

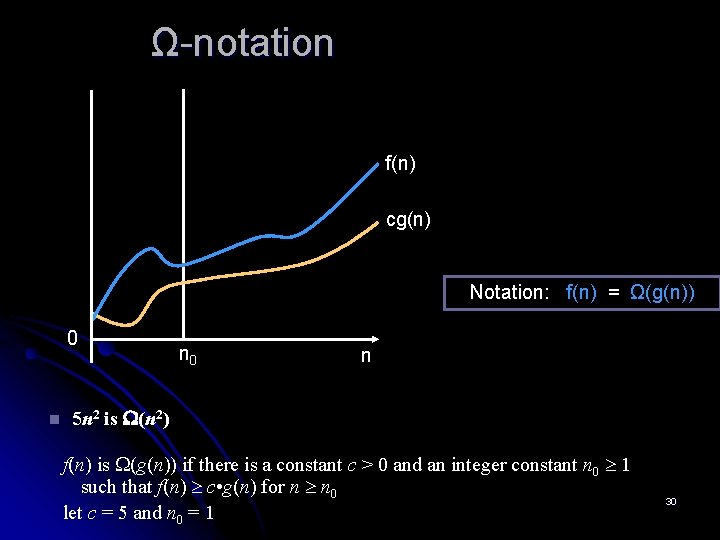

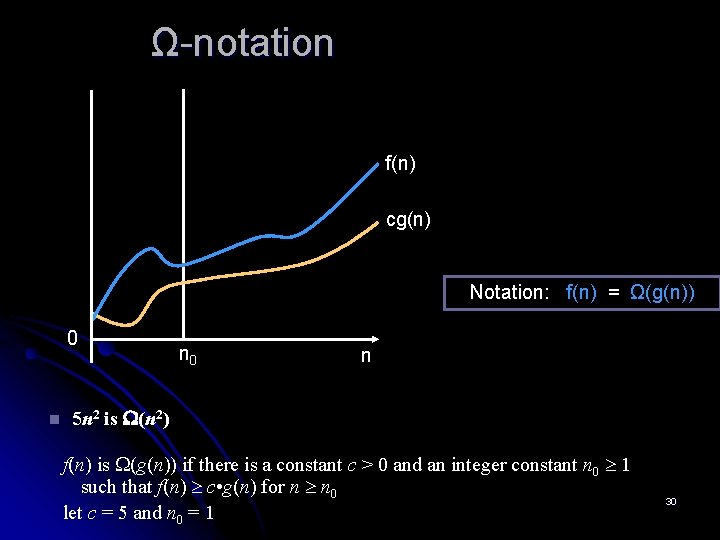

Ω-notation f(n) cg(n) Notation: f(n) = Ω(g(n)) 0 n n 0 n 5 n 2 is (n 2) f(n) is (g(n)) if there is a constant c > 0 and an integer constant n 0 1 such that f(n) c • g(n) for n n 0 let c = 5 and n 0 = 1 30

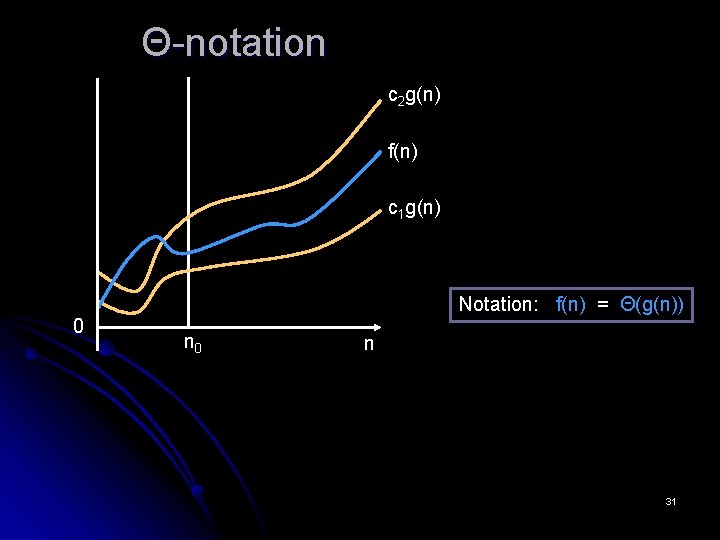

Θ-notation c 2 g(n) f(n) c 1 g(n) 0 Notation: f(n) = Θ(g(n)) n 0 n 31

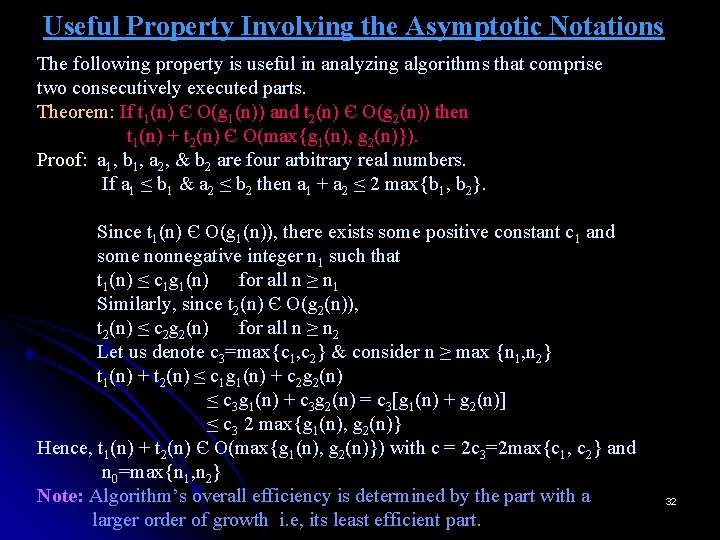

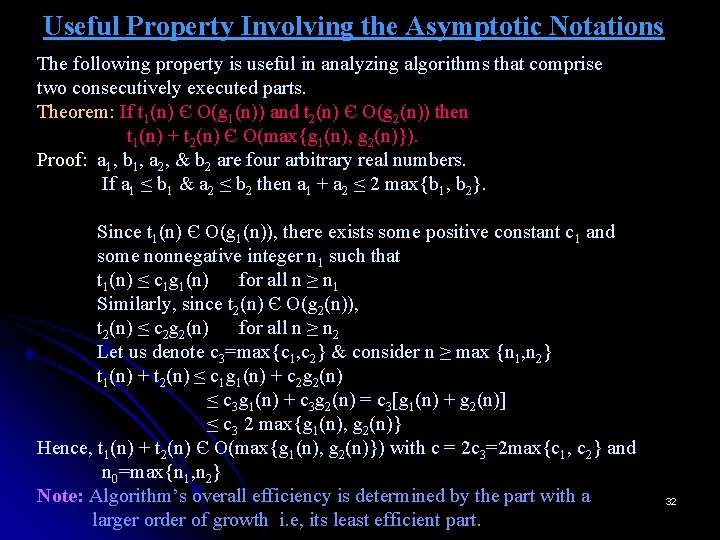

Useful Property Involving the Asymptotic Notations The following property is useful in analyzing algorithms that comprise two consecutively executed parts. Theorem: If t 1(n) Є O(g 1(n)) and t 2(n) Є O(g 2(n)) then t 1(n) + t 2(n) Є O(max{g 1(n), g 2(n)}). Proof: a 1, b 1, a 2, & b 2 are four arbitrary real numbers. If a 1 ≤ b 1 & a 2 ≤ b 2 then a 1 + a 2 ≤ 2 max{b 1, b 2}. Since t 1(n) Є O(g 1(n)), there exists some positive constant c 1 and some nonnegative integer n 1 such that t 1(n) ≤ c 1 g 1(n) for all n ≥ n 1 Similarly, since t 2(n) Є O(g 2(n)), t 2(n) ≤ c 2 g 2(n) for all n ≥ n 2 Let us denote c 3=max{c 1, c 2} & consider n ≥ max {n 1, n 2} t 1(n) + t 2(n) ≤ c 1 g 1(n) + c 2 g 2(n) ≤ c 3 g 1(n) + c 3 g 2(n) = c 3[g 1(n) + g 2(n)] ≤ c 3 2 max{g 1(n), g 2(n)} Hence, t 1(n) + t 2(n) Є O(max{g 1(n), g 2(n)}) with c = 2 c 3=2 max{c 1, c 2} and n 0=max{n 1, n 2} Note: Algorithm’s overall efficiency is determined by the part with a larger order of growth i. e, its least efficient part. 32

Using Limits for Comparing Orders of Growth 33

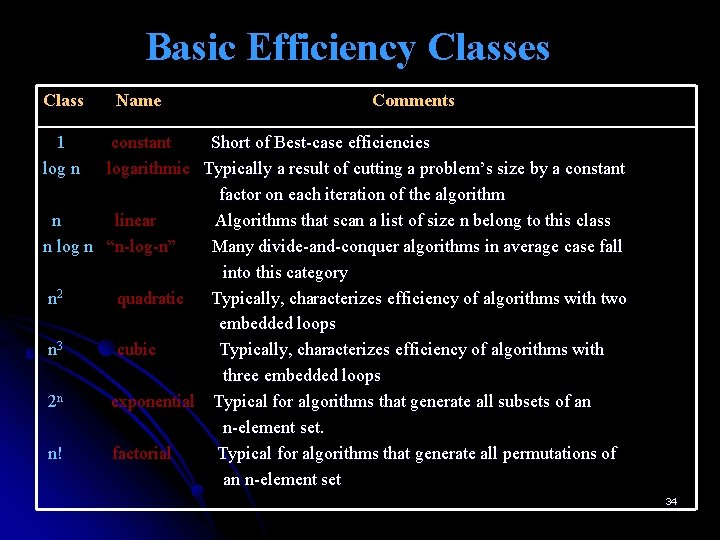

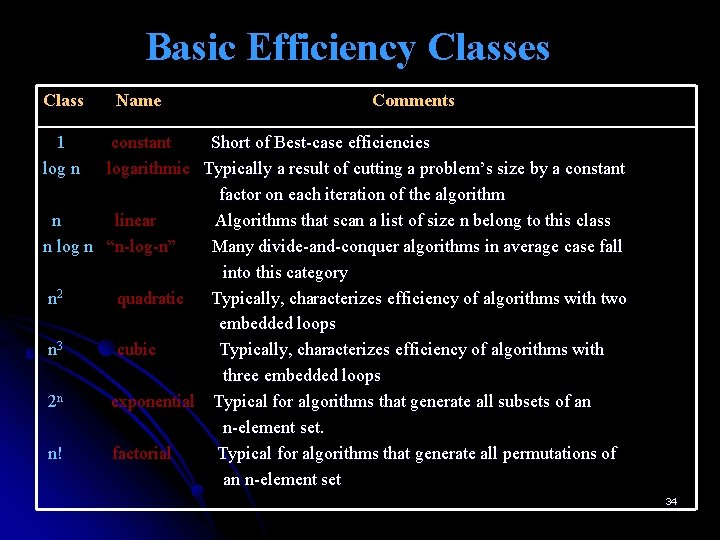

Basic Efficiency Classes Class Name Comments 1 log n constant Short of Best-case efficiencies logarithmic Typically a result of cutting a problem’s size by a constant factor on each iteration of the algorithm n linear Algorithms that scan a list of size n belong to this class n log n “n-log-n” Many divide-and-conquer algorithms in average case fall into this category n 2 quadratic Typically, characterizes efficiency of algorithms with two embedded loops n 3 cubic Typically, characterizes efficiency of algorithms with three embedded loops 2 n exponential Typical for algorithms that generate all subsets of an n-element set. n! factorial Typical for algorithms that generate all permutations of an n-element set 34

Running Time n Input Size 35

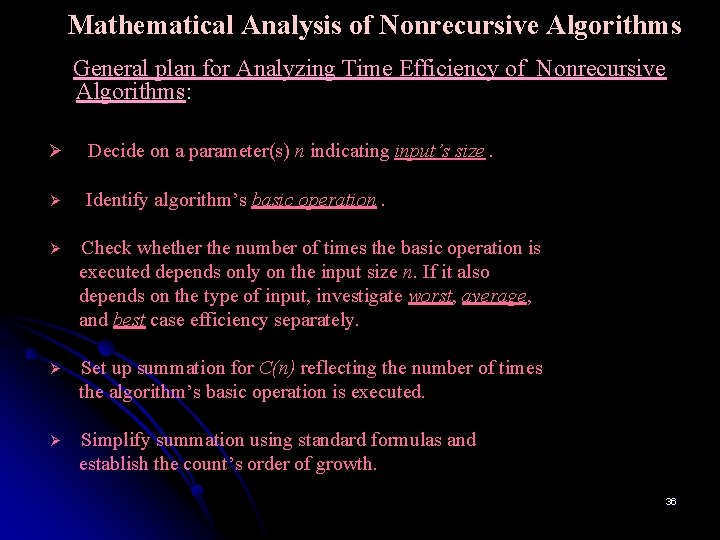

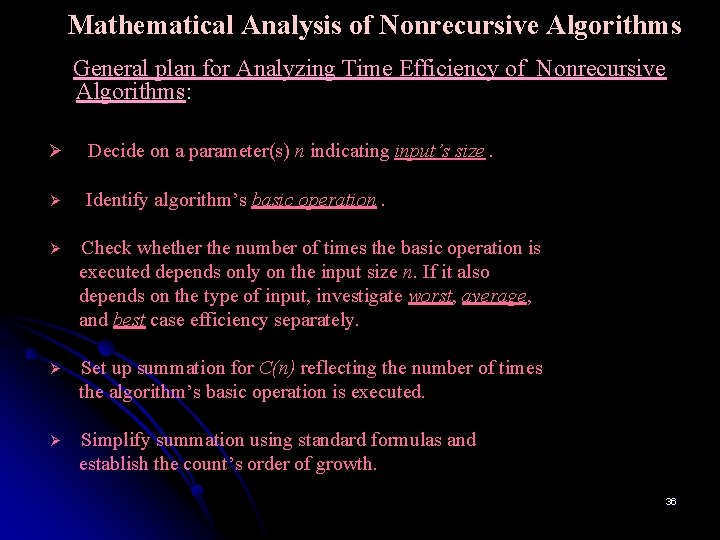

Mathematical Analysis of Nonrecursive Algorithms General plan for Analyzing Time Efficiency of Nonrecursive Algorithms: Ø Decide on a parameter(s) n indicating input’s size. Ø Identify algorithm’s basic operation. Ø Check whether the number of times the basic operation is executed depends only on the input size n. If it also depends on the type of input, investigate worst, average, and best case efficiency separately. Ø Set up summation for C(n) reflecting the number of times the algorithm’s basic operation is executed. Ø Simplify summation using standard formulas and establish the count’s order of growth. 36

Two Basic Rules of Sum Manipulation : u u ∑ cai = c ∑ ai i=l (R 1) i=l u u u ∑ (ai ± bi) = ∑ ai ± ∑ bi i=l (R 2) i=l Two Summation Formulas : u ∑ 1 = u – l + 1 where l ≤ u are some lower and upper integer limits i=l n (S 1) n ∑ i = 1 + 2 + … + n = n(n + 1) ≈ 1 n 2 Є Θ(n 2) i=0 i=1 2 2 (S 2) 37

Example 1: To find the largest element in a list of n numbers. ALGORITHM Max. Element(A[0…n-1]) //Determines the value of the largest element in a given array //Input: An array A[0…n-1] of real numbers //Output: The value of the largest element in A maxval ← A[0] for i ← 1 to n-1 do if A[i] > maxval ← A[i] return maxval 38

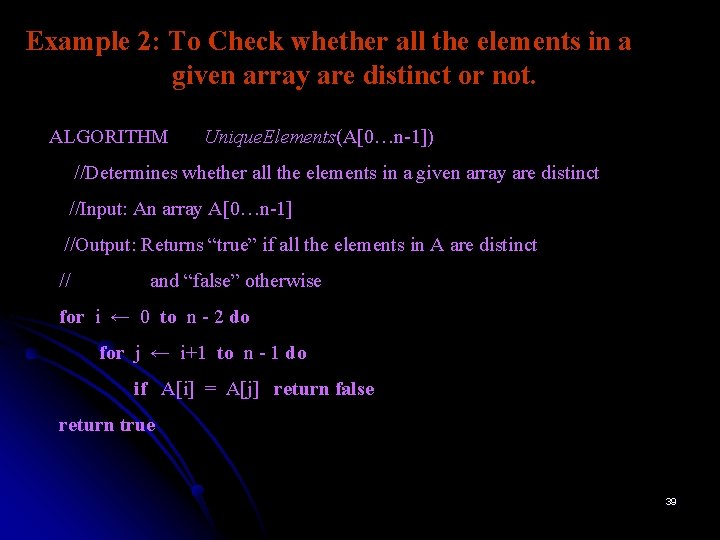

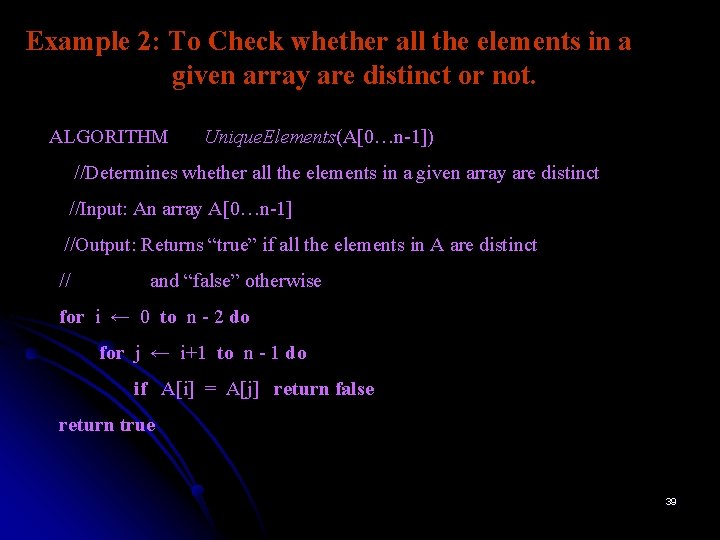

Example 2: To Check whether all the elements in a given array are distinct or not. ALGORITHM Unique. Elements(A[0…n-1]) //Determines whether all the elements in a given array are distinct //Input: An array A[0…n-1] //Output: Returns “true” if all the elements in A are distinct // and “false” otherwise for i ← 0 to n - 2 do for j ← i+1 to n - 1 do if A[i] = A[j] return false return true 39

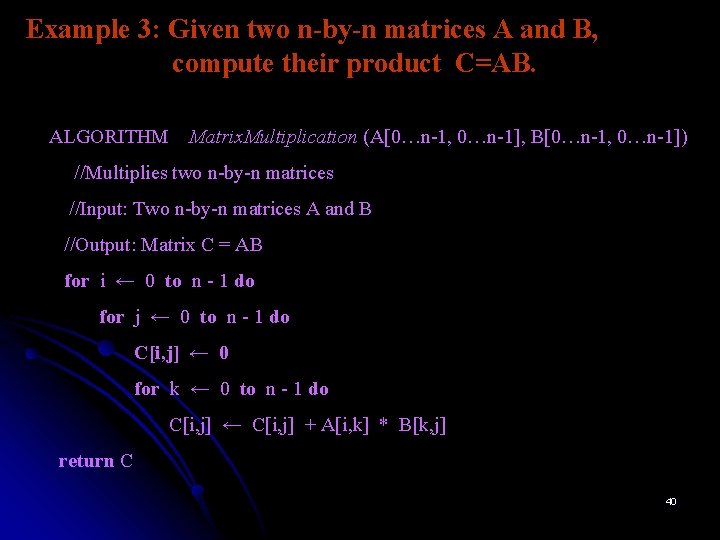

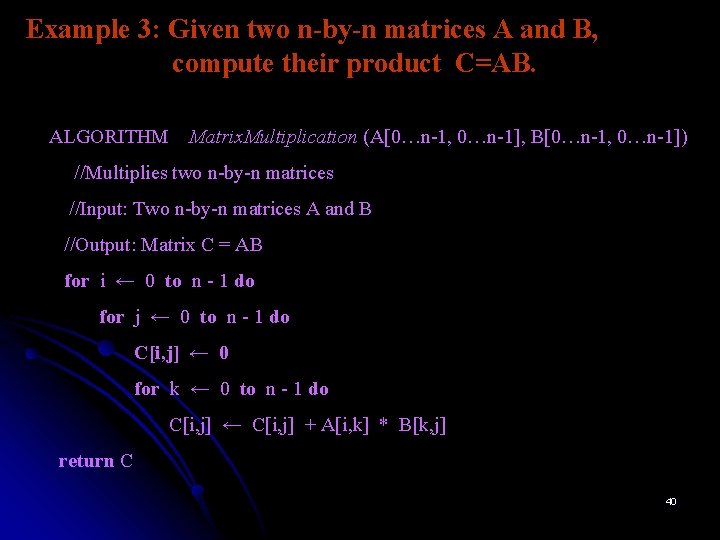

Example 3: Given two n-by-n matrices A and B, compute their product C=AB. ALGORITHM Matrix. Multiplication (A[0…n-1, 0…n-1], B[0…n-1, 0…n-1]) //Multiplies two n-by-n matrices //Input: Two n-by-n matrices A and B //Output: Matrix C = AB for i ← 0 to n - 1 do for j ← 0 to n - 1 do C[i, j] ← 0 for k ← 0 to n - 1 do C[i, j] ← C[i, j] + A[i, k] * B[k, j] return C 40

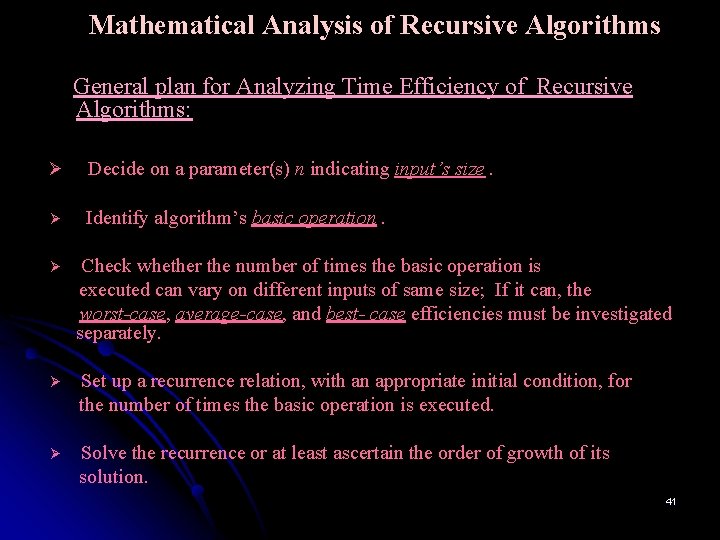

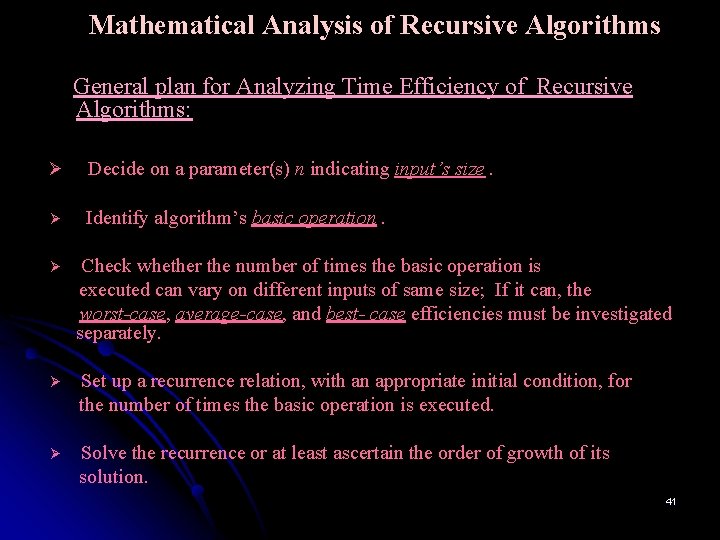

Mathematical Analysis of Recursive Algorithms General plan for Analyzing Time Efficiency of Recursive Algorithms: Ø Decide on a parameter(s) n indicating input’s size. Ø Identify algorithm’s basic operation. Ø Check whether the number of times the basic operation is executed can vary on different inputs of same size; If it can, the worst-case, average-case, and best- case efficiencies must be investigated separately. Ø Set up a recurrence relation, with an appropriate initial condition, for the number of times the basic operation is executed. Ø Solve the recurrence or at least ascertain the order of growth of its solution. 41

End of Chapter 2 42