An Introduction to the Human Rights Protection System

- Slides: 152

An Introduction to the Human Rights Protection System Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

The intertwined protection of the fundamental rights’ protection at national and international level The Spanish Constitution 1978 The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights 2000 The European Convention on Human Rights 1950 (ratified by Spain in 1977)

The human rights protection as a yardstick for democracy Fundamental rights regulate the rights, but also the duties, of every individual. When they are envisaged by the Constitution and by national laws, we are referring to national human rights law. When they are envisaged by international treaties, we refer to international human rights law. Indeed, since individuals are human beings, they (we) are all equal in every country of the world, so the different degree of how and to what extent fundamental rights are guaranteed in a single State can tell more about, for instance, the degree of democracy and the respect of the rule of law which has been reached in that specific country.

The three generations of human rights From a legal perspective, some of the most influential legal scholars have significantly contributed to the development of the current international framework of human rights protection. Prof. Karel Vasak proposed a categorization of rights distinguishing three generations of human rights, which is today considered internationally valid: ► First-generation civil and political rights (right to life and political participation); ► Second-generation economic, social and cultural rights (right to subsistence); ► Third-generation solidarity rights (right to peace, right to clean environment).

Criticism of the current international human rights regime The current international human rights regime is not appreciated by all. For instance, Prof. David Kennedy argues that the current international human rights regime reflects only a partial vision of the international community which is merely based on Western values. In the same vein, Prof. Makau Mutua goes much further calling the current international human rights framework an attempt of cultural imperialism imposed by the most powerful countries (the Western countries) on the weakest ones (the ex Third World countries) and he stress that this regime is not taking into account all the different values which are not ensrhined in Western cultural traditions.

Modern Constitutionalism ► The protection of fundamental rights found its place in modern constitutionalism which was born in the late XIX century – beginning of the XX century. ► Constitutionalism is based on two pillars: 1. The respect of the rule of law; 2. The protection of fundamental rights. Indeed, constitutionalism can be described as a complex of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law (Fehrenbacher) or as historical experience, where the exercise of governmental powers is limited to a higher law (Fellman).

How fundamental rights are legally protected in national legal orders? Constitution EU and International law Legislative acts

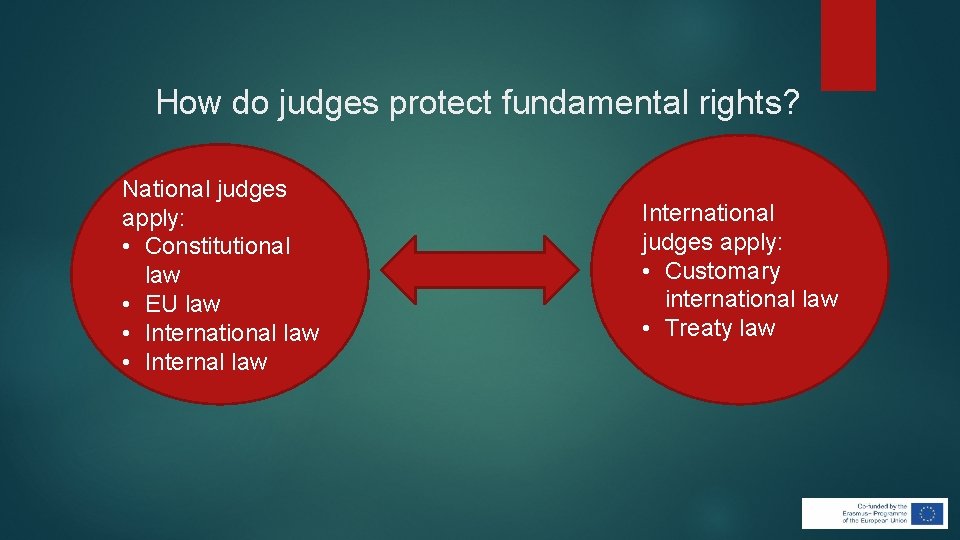

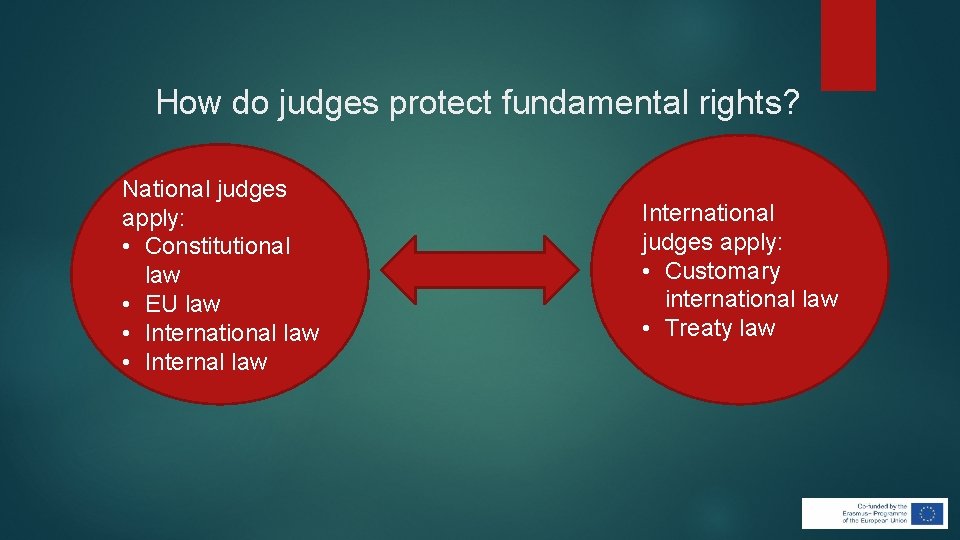

How do judges protect fundamental rights? National judges apply: • Constitutional law • EU law • International law • Internal law International judges apply: • Customary international law • Treaty law

The political human rights movements The legal protection of human rights has been boosted by the human rights movements during the course of the XX century and especially after the end of the World War II The Feminist movements: advocates for women's human rights criticized the early human rights movement for focusing on male concerns and artificially excluding women's issues from the public sphere. The internet based human rights movements: internet has expanded the power of the human rights movement by improving communication between activists in different physical locations. The human rights movements against corporations: HR movements have historically focused on abuses by states, and some have argued that it has not attended closely enough to the actions of corporations.

Some tentative conclusions The protection of fundamental rights in ancient times was sporadic and only indirect, grounded on the protection of other (statual) interests. The emergence of constitutionalism significally changed the picture and put fundamental rights at the centre of modern legal systems. Different degrees of protection still exist and will always exist, as they are due to cultural diversity and different legal and social traditions. In the field of the fundamental rights protection, States are only one of the actors who participate in their evolution. Since these rights have strong political and cultural dimensions, other actors such as NGOs, human rights movements and, above all, international organizations are substantially shaping the scope and the content of fundamental rights towards a more comprehensive, although not always more effective, international legal protection.

The multivel system of protection of fundamental rights Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -PP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

fundamental rights in the European framework ► The international system of human rights protection ► The Council of Europe and the European Convention on Human Rights. ► The European Union and the Charter of Fundamental Rights. ► International human rights law and the Spanish system: Article 10. 2 of the Spanish Constitution and the jurisprudence of the Spanish Constitutional Court.

The international system of human rights protection Since the birth of what is called the contemporary international community, many international treaties concerning human rights has been signed and ratified by states. Some of those treaties also establish international tribunals in charge of guaranteeing a judicial protection of those rights, some others only establish quasi-judicial committees that can deliver non binding political declarations of human rights violations. Therefore not all the human rights protection systems have the same effectiveness.

The international system of human rights protection A very important distinction can be drawn between universal human rights protection systems and regional human rights protection systems. Regarding the universal system, the only one that concerns all the areas of the globe is the united nation human rights protection system. Concerning regional human rights protection systems, they vary from a continent to another. Currently, Europe, America and Africa have a proper international human rights protection system, while Asia and Oceania have not yet developed one specific regional system.

The UN system of human rights’ protection The United Nations (UN) plays a key role in the development and promotion of the international human rights protection system. Constituted under the United Nations Charter (1945) the UN aims to “promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion”. the human rights stipulations laid down in the UN Charter are the foundations on which the UN human rights regime is built and on which it continues to develop.

The Council of Europe (Co. E) is the core institution when it comes to enhancing human rights protection in Europe. The Co. E was founded by ten states in 1949 and has developed one of the most advanced systems for the protection of human rights anywhere in the world. it is an international organisation with currently 47 Member States and is based in Strasbourg, France. it aims at fostering co-operation in Europe and enhancing the protection and promotion of human rights and also social cohesion, cultural diversity and democratic citizenship.

European Convention on Human Rights The ECHR is the most important European human rights instrument. it is important within the context of international human rights law for several reasons: ► It is the first comprehensive treaty in the world in this field; ► It established the first international complaints procedure and the first international court for the determination of human rights matters; ► It remains the most judicially developed of all the human rights systems, ► It has generated a more extensive jurisprudence than any other parts of the international system; ► It now applies to some 30% of the nations in the world. The ECHR was adopted in 1950 and was developed in the wake of the experiences of the atrocities of the Third Reich and the Second World War.

The EU system for fundamental rights’ protection Human rights played only a minor role in the history of the European Communities (EC), the predecessor of the EU. the EC primarily aimed at economic integration and attempts to insert human rights provisions initially failed. The founding Treaties therefore did not take into consideration human rights provisions, as they were not considered as being of high priority within this economyorientated context.

The normative evolution of the EU human rights provisions It was not until the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992, which established the EU, that human rights were considered in Art. 6 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). Art. 6 “[t]he Union shall respect fundamental rights, as guaranteed by the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms signed in Rome on 4 November 1950 and as they result from the constitutional traditions common to the Member States, as general principles of Community law. ”

The Lisbon Treaty and the current EU normative framework on human rights Today three are the main provisions of the EU treaties that envisage human rights’ protection. ART. 2 TEU ART. 6 TEU ART. 21 TEU

The EU charter of fundamental rights The EU charter enshrines civil, political, social and economic rights for EU citizens and residents into EU law. Its overall protection is broader than that of the ECHR. Under the Charter, the EU must act and legislate consistently with the Charter and the EU's courts will strike down legislation adopted by the EU's institutions that contravenes it. The Charter applies to the Institutions of the EU and its member states when implementing EU law. Following the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 the Charter has the same legal value as the European Union treaties (primary source of EU law). The Charter contains 54 articles divided into 7 titles. The first six titles deal with substantive rights: dignity, freedoms, equality, solidarity, citizens' rights and justice, while the last title deals with the interpretation and application of the Charter. Much of Charter is based on the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), European Social Charter, the case-law of the European Court of Justice and pre-existing provisions of European Union law.

Art. 10 of the Spanish Constitution If one were to sum up the Spanish Constitution in one article, it would be art. 10. The human dignity, the inviolable and inherent rights, the free development of the personality, the respect for the law and for the rights of others are the foundation of political order and social peace. The principles relating to the fundamental rights and liberties recognized by the Constitution shall be interpreted in conformity with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the international treaties and agreements ratified by Spain.

The Constitutional Court’s interpretation of Art. 10 (2) The importance of art. 10 (2) has always been stressed by the Spanish constitutional court, which has deeply contributed to its current interpretation and application. However, The court clarified that this provision does not add any other fundamental rights to those already recognized by the Constitution. The catalogue of fundamental rights is rigid, and claimants cannot invoke further rights before the constitutional court on the basis of art. 10 (2). This interpretation has practical consequences on the possibility to file an amparo appeal.

Fundamental Rights and the Spanish Constitutional System ALEJANDRO SAIZ ARNAIZ MARCO BOCCHI DEPARTMENT OF LAW POMPEU FABRA UNIVERSITY 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

Fundamental rights in the Spanish Constitution ► A brief outline of the constitutional features of the Spanish legal system ► The structure of Title I of the Spanish Constitution. ► Fundamental rights, principles governing economic and social policy, constitutional duties and institutional guarantees. ► Autonomous Communities and constitutional rights and duties.

Constitutional features of the Spanish legal system THE SPANISH CONSTITUTION OF 1978 IS THE DEMOCRATIC LAW THAT IS SUPREME IN SPAIN. IT WAS APPROVED IN PLENARY SESSIONS OF THE CONGRESS OF DEPUTIES AND THE SENATE HELD ON 31 OCTOBER 1978, AND RATIFIED BY A SPANISH PEOPLE'S REFERENDUM OF 6 DECEMBER 1978. ON PASSING THE CONSTITUTION, THE CITIZENS EXPRESSED THE DESIRE TO ESTABLISH JUSTICE, LIBERTY AND SECURITY AND TO PROMOTE THE WELL-BEING OF ALL BY SEEKING TO GUARANTEE DEMOCRATIC COEXISTENCE WITHIN THE CONSTITUTION AND THE LAWS IN ACCORDANCE WITH A FAIR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL ORDER (IN OTHER WORDS, UNDER THE RULE OF LAW). THEREFORE, THE CONSTITUTION IS NOT ONLY THE PRIMARY SOURCE OF LAW IN SPAIN, BUT ALSO THE HIGHER EXPRESSION OF PUBLIC DEMOCRACY THAT CHARACTERIZE THE ESSENCE OF THE SPANISH STATE.

The idea of Constitutionalism in Spain DESPITE THE MAJOR INNOVATIONS OF THE 1978 CONSTITUTION, MANY OF ITS ELEMENTS WERE INSPIRED BY THE PREVIOUS CONSTITUTIONS THAT THROUGHOUT THE CENTURIES, HAVE REPRESENTED THE LEGAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE SPANISH STATE. IT IS NOT EXAGGERATED TO STRESS THAT THE HISTORY OF SPANISH CONSTITUTIONALISM IS SECOND, FOR COMPLEXITY AND BACKGROUND, ONLY TO THE FRENCH, WHICH HAVE ALSO INSPIRED IT. INDEED, THE IDEA OF A NATIONAL CONSTITUTION FOR SPAIN AROSE FROM THE DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MAN AND OF THE CITIZEN INITIATED AS A RESULT OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION. THE EARLIEST DOCUMENT RECOGNIZED AS SUCH WAS LA PEPA PASSED IN CADIZ IN 1812 AS A RESULT OF THE PENINSULAR WAR (1807– 1814), WHICH WAS A MILITARY CONFLICT BETWEEN THE FIRST FRENCH EMPIRE AND THE ALLIED POWERS OF THE SPANISH EMPIRE (THE UNITED KINGDOM AND PORTUGAL) FOR CONTROL OF THE IBERIAN PENINSULA DURING THE NAPOLEONIC WARS.

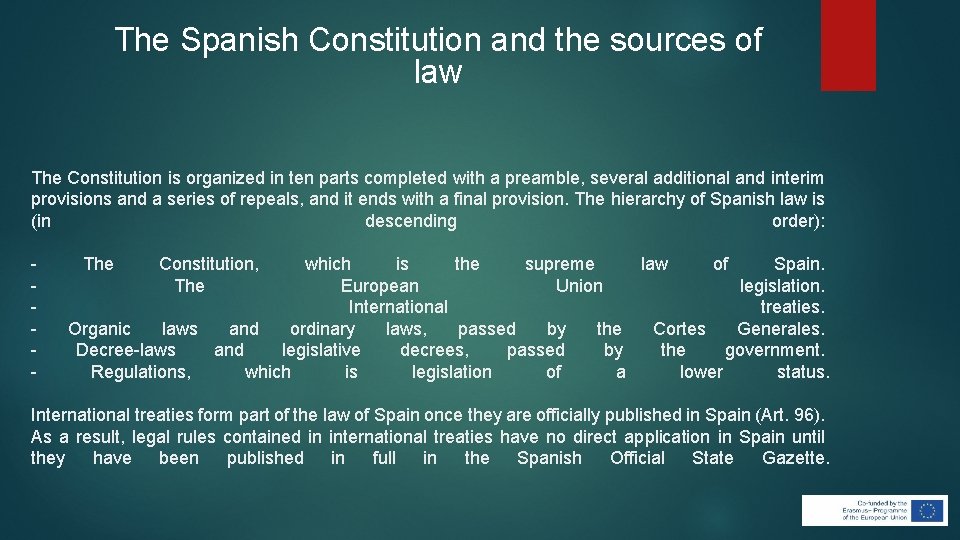

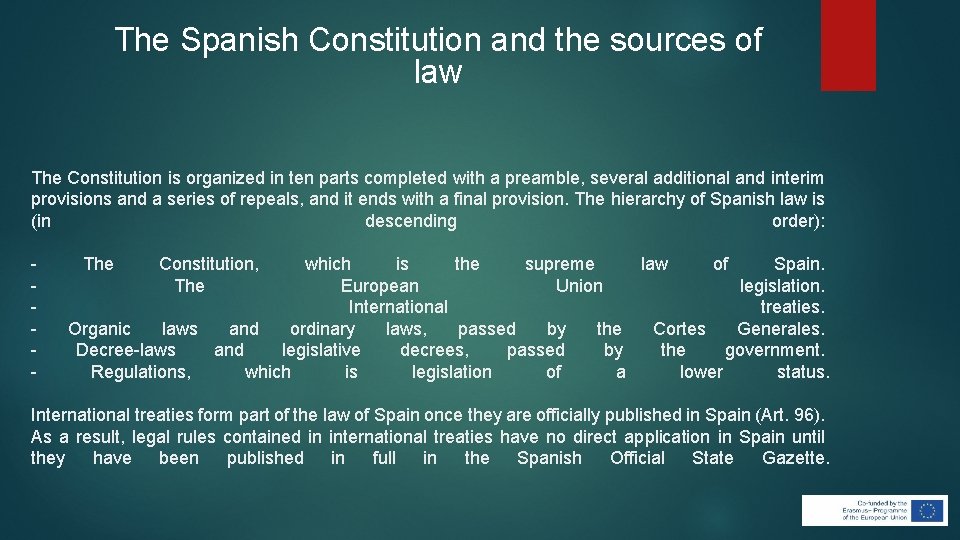

The Spanish Constitution and the sources of law The Constitution is organized in ten parts completed with a preamble, several additional and interim provisions and a series of repeals, and it ends with a final provision. The hierarchy of Spanish law is (in descending order): - - - The Constitution, The which is the supreme law of Spain. European Union legislation. International treaties. Organic laws and ordinary laws, passed by the Cortes Generales. Decree-laws and legislative decrees, passed by the government. Regulations, which is legislation of a lower status. International treaties form part of the law of Spain once they are officially published in Spain (Art. 96). As a result, legal rules contained in international treaties have no direct application in Spain until they have been published in full in the Spanish Official State Gazette.

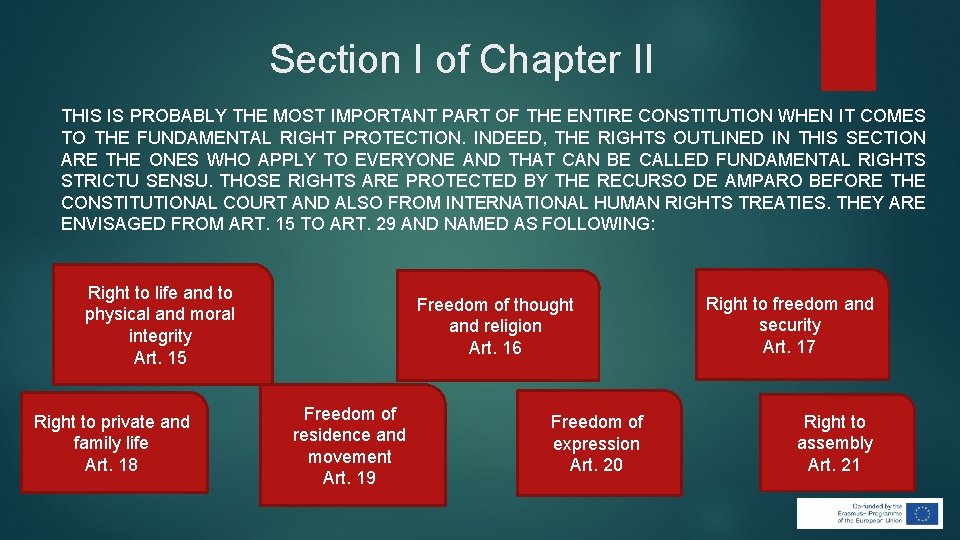

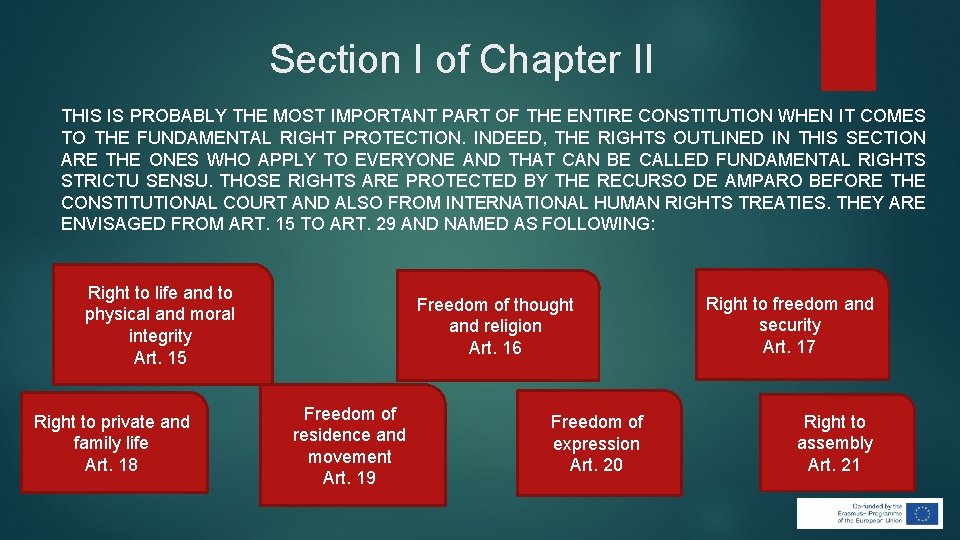

Section I of Chapter II THIS IS PROBABLY THE MOST IMPORTANT PART OF THE ENTIRE CONSTITUTION WHEN IT COMES TO THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT PROTECTION. INDEED, THE RIGHTS OUTLINED IN THIS SECTION ARE THE ONES WHO APPLY TO EVERYONE AND THAT CAN BE CALLED FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS STRICTU SENSU. THOSE RIGHTS ARE PROTECTED BY THE RECURSO DE AMPARO BEFORE THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT AND ALSO FROM INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS TREATIES. THEY ARE ENVISAGED FROM ART. 15 TO ART. 29 AND NAMED AS FOLLOWING: Right to life and to physical and moral integrity Art. 15 Right to private and family life Art. 18 Freedom of thought and religion Art. 16 Freedom of residence and movement Art. 19 Freedom of expression Art. 20 Right to freedom and security Art. 17 Right to assembly Art. 21

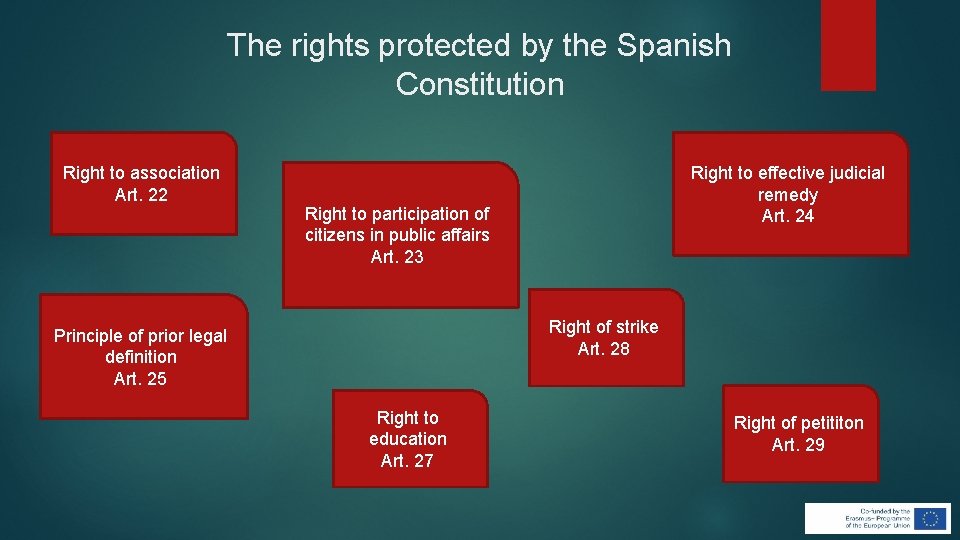

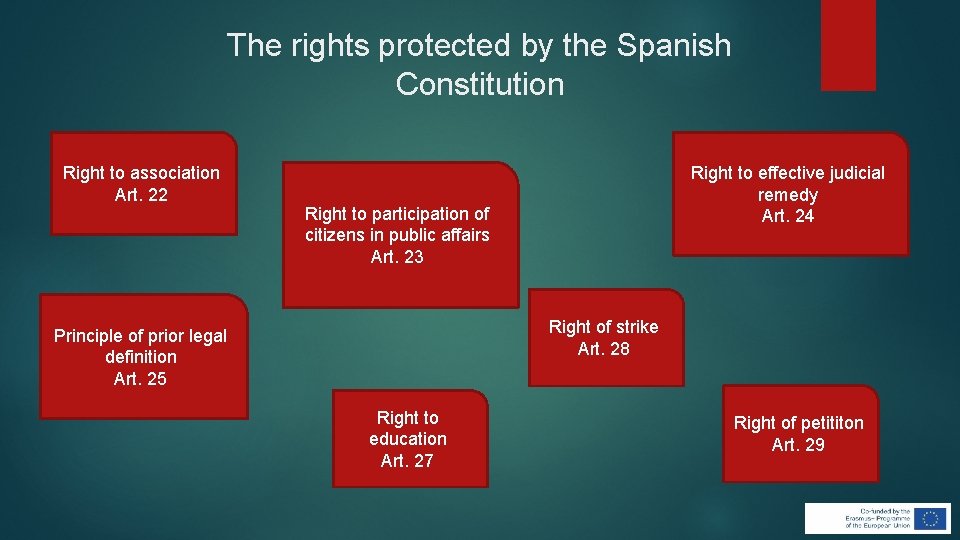

The rights protected by the Spanish Constitution Right to association Art. 22 Right to effective judicial remedy Art. 24 Right to participation of citizens in public affairs Art. 23 Right of strike Art. 28 Principle of prior legal definition Art. 25 Right to education Art. 27 Right of petititon Art. 29

The fundamental rights’ field of application FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS ARE UNIVERSAL, INCOMPATIBLE WITH THE SUPERIORITY OF ANY INDIVIDUAL, PEOPLE, GROUP OR SOCIAL CLASS. THE RECOGNITION THEREOF DOES NOT DEPEND ON FACTORS SUCH AS RACE, GENDER, RELIGION, OPINION, NATIONALITY OR ANY OTHER PERSONAL OR SOCIAL CONDITION OR CIRCUMSTANCE. AS INHERENT TO THE INDIVIDUAL, THEY ARE IRREVOCABLE, NON-NEGOTIABLE (CANNOT BE “SOLD”) AND UNRELINQUISHABLE. THESE RIGHTS ARE RECOGNIZED NOT ONLY UNDER PART I OF THE CONSTITUTION, BUT ALSO UNDER INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND UNDER THE CONSTITUTIONS OF THE OTHER STATES.

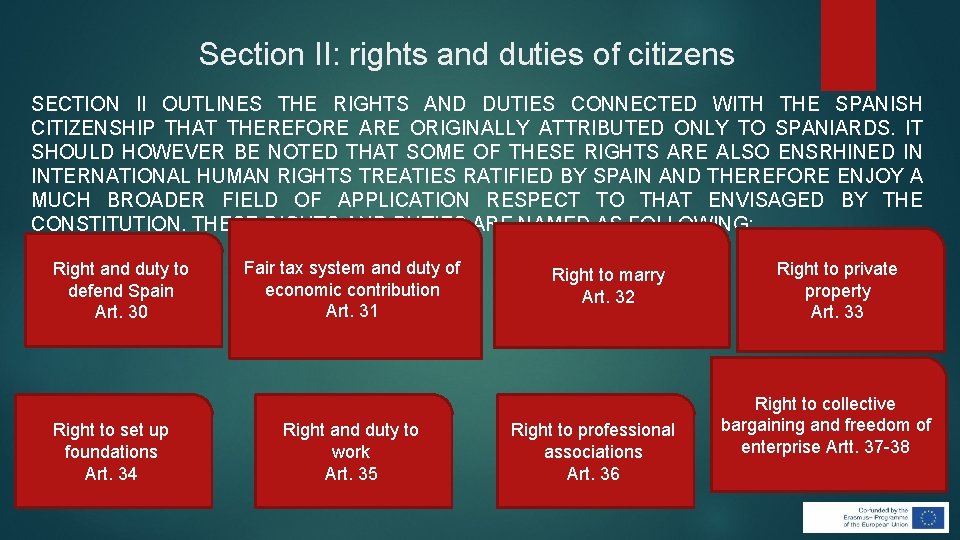

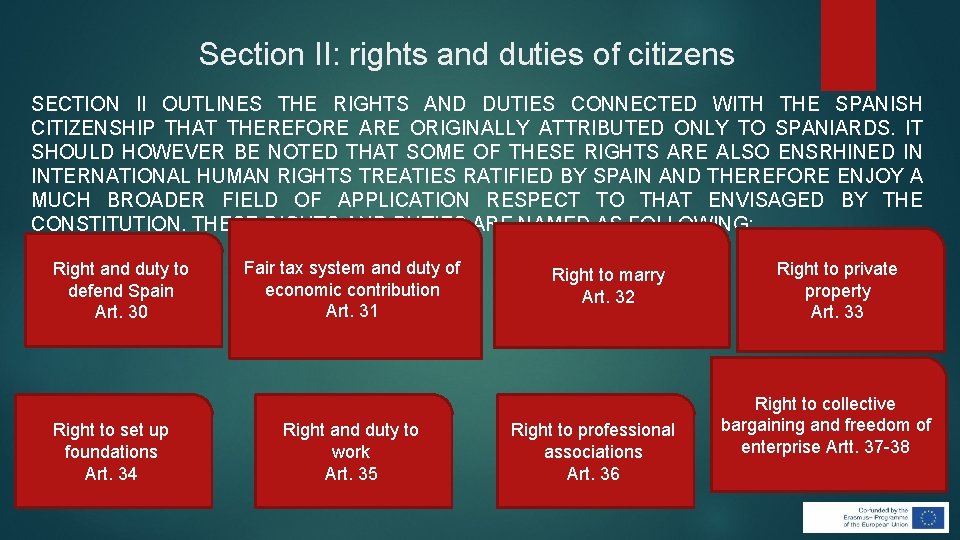

Section II: rights and duties of citizens SECTION II OUTLINES THE RIGHTS AND DUTIES CONNECTED WITH THE SPANISH CITIZENSHIP THAT THEREFORE ARE ORIGINALLY ATTRIBUTED ONLY TO SPANIARDS. IT SHOULD HOWEVER BE NOTED THAT SOME OF THESE RIGHTS ARE ALSO ENSRHINED IN INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS TREATIES RATIFIED BY SPAIN AND THEREFORE ENJOY A MUCH BROADER FIELD OF APPLICATION RESPECT TO THAT ENVISAGED BY THE CONSTITUTION. THESE RIGHTS AND DUTIES ARE NAMED AS FOLLOWING: Right and duty to defend Spain Art. 30 Right to set up foundations Art. 34 Fair tax system and duty of economic contribution Art. 31 Right and duty to work Art. 35 Right to marry Art. 32 Right to professional associations Art. 36 Right to private property Art. 33 Right to collective bargaining and freedom of enterprise Artt. 37 -38

Principles governing economic and social policy CHAPTER 3 OF PART I OF THE SPANISH CONSTITUTION IS THE CLEAREST EXAMPLE OF THE INFLUENCE THAT THE DOCTRINE OF THE SOCIAL STATE EXERTED ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL FATHERS OF 1978. IT REPRESENTS, INDEED, A PECULIAR PART OF THE CONSTITUTION WHICH, FOR INSTANCE, DISTINGUISH IT QUITE NEATLY FROM OTHER CONTINENTAL CONSTITUTIONS SUCH AS THE FRENCH, THE GERMAN AND THE ITALIAN CONSTITUTIONS WHICH DO NOT INCLUDE IN THEIR CATALOGUES OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS A SIMILAR CHAPTER.

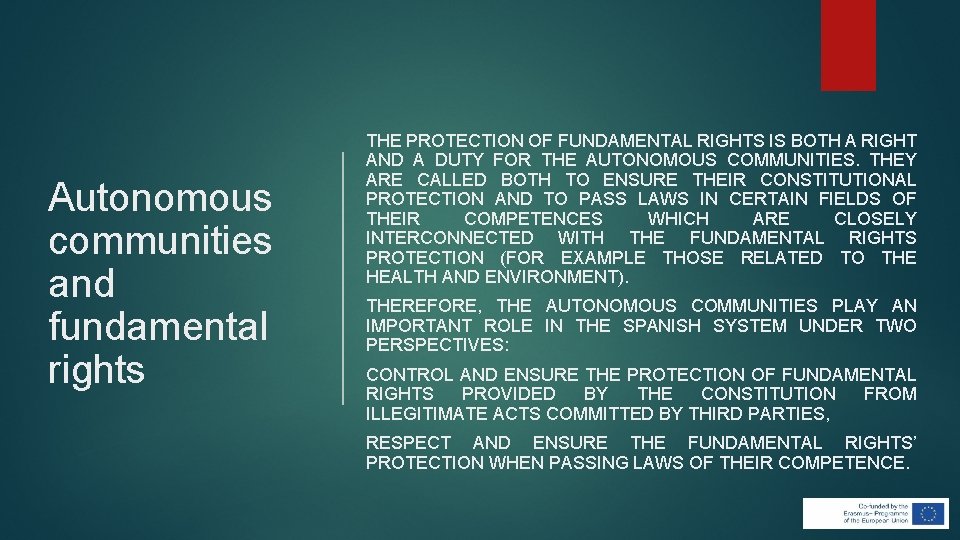

Autonomous communities and fundamental rights THE PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IS BOTH A RIGHT AND A DUTY FOR THE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES. THEY ARE CALLED BOTH TO ENSURE THEIR CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTION AND TO PASS LAWS IN CERTAIN FIELDS OF THEIR COMPETENCES WHICH ARE CLOSELY INTERCONNECTED WITH THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS PROTECTION (FOR EXAMPLE THOSE RELATED TO THE HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENT). THEREFORE, THE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN THE SPANISH SYSTEM UNDER TWO PERSPECTIVES: CONTROL AND ENSURE THE PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS PROVIDED BY THE CONSTITUTION FROM ILLEGITIMATE ACTS COMMITTED BY THIRD PARTIES, RESPECT AND ENSURE THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS’ PROTECTION WHEN PASSING LAWS OF THEIR COMPETENCE.

Autonomous communities and fundamental rights THE HIGHLY DECENTRALIZED SPANISH LEGAL SYSTEM ATTRIBUTES INDIRECT COMPETENCES TO THE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES FOR THE PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS. EVEN THOUGH THIS MATTER IS ONE OF THE PILLAR OF THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM, AND THEREFORE, CANNOT BE DIFFERENTLY REGULATED BY THE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES, IN THE CONCRETE EXERCISE OF THEIR COMPETENCES, THE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES MIGHT HAVE TO DEAL WITH SOME ASPECTS CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND, IN THESE CASES, THEY ARE BOUND BY THE SAME PUBLIC POWERS OBLIGATIONS THAT APPLY TO THE ORGANS OF THE CENTRAL STATE. FOR EXAMPLE, AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES HAVE TO GUARANTEE THE MINIMUM HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARDS FIXED BY THE SPANISH LAW WHEN THEY REGULATE CERTAIN AREAS OF THEIR COMPETENCE, SUCH AS ENVIRONMENT, EDUCATION, EQUALITY AND EMPLOYMENT.

The limits attributed to the autonomous communities THE NATIONAL AUTHORITIES AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT HAVE HOWEVER DEMONSTRATED IN DIFFERENT CIRCUMSTANCES TO DISAPPROVE ANY ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE AUTONOMOUS COMMUNITIES TO IMPLEMENT THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS PROTECTION, WHEN THIS IS NOT STRICTLY NECESSARY FOR THE EXECUTION OF THEIR COMPETENCES. THE CENTRAL STATE IS INDEED VERY CAREFUL IN MAINTAINING A FULL CONTROL OF THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS PROTECTION THROUGH THE PRINCIPAL MECHANISMS WHO ARE ENVISAGED BY THE CONSTITUTION: THE RECURSO DE AMPARO; THE OMBUDSMAN (DEFENSOR DEL PUEBLO); THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS CONTRACTED BY STATES IN THE CONTEXT OF THE INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTION.

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND HOLDERS Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

HOLDER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND THEIR EXERCISE ►The institutional status of foreigners. ►Fundamental rights of legal entities and minors. ►The vertical and horizontal effectiveness of fundamental rights.

SPANIARDS AND ALIENS Chapter 1 of the Constitution contain the regulation of the status of citizens and aliens. Those norms are aimed at highlighting the constitutional basis of the difference between those who have the Spanish citizenships and the foreigners, who have the citizenship of another country. In the full respect of the principle of non discrimination, every Constitution provides different legal mechanisms for citizens and foreigners in order to guarantee to both of them the enjoyment of rights and the subjection to duties. Citizens and foreigners can be seen as the two sides of the same coin, meaning that the protection of their constitutional rights is guarantee but it is practically reached through different means.

THE INSTITUTION AL STATUS OF FOREIGNERS THE INSTITUTIONAL STATUS OF FOREIGNERS IS A COMPLEX TOPIC BECAUSE IT IS SUBJECTED BOTH TO INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL LAWS. NOWADAYS NATIONAL LEGISLATORS CANNOT REGULATE THIS MATTER WITHOUT OBSERVING THE RELEVANT APPLICABLE NORMS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW. SINCE MANY DECADES, A SET OF INTERNATIONAL NORMS CONCERNING THE STATUS OF FOREIGNERS BECAME PART OF CUSTOMARY LAW AND THEREFORE BINDING FOR ALL STATES. WE THEREFORE NEED TO HIGHLIGHT BOTH THE INTERNATIONAL AND THE NATIONAL DIMENSION OF THIS TOPIC.

How a foreigner can become a Spanish citizen and who are the Spanish citizens? “Spanish nationality shall be acquired, retained and lost in accordance with the provisions of the law” Art. 11 Cost.

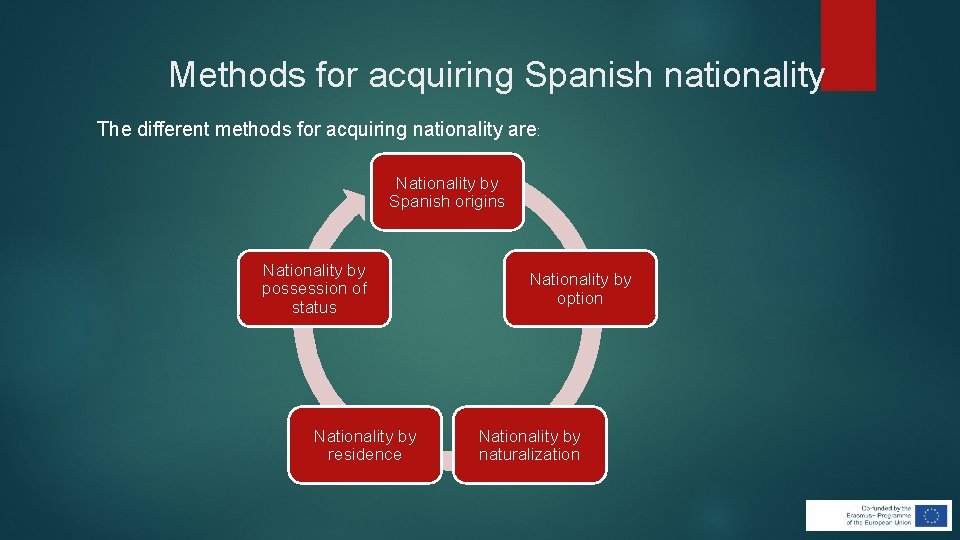

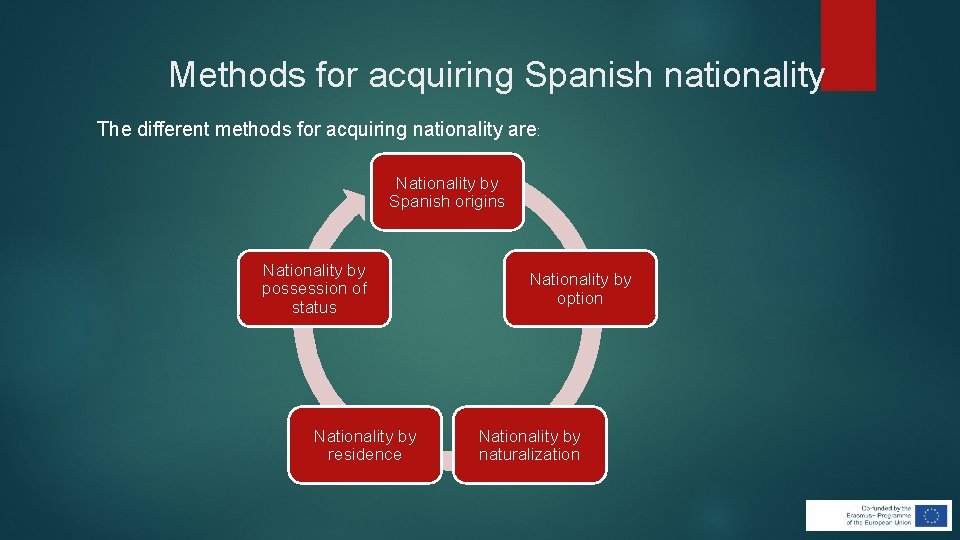

Methods for acquiring Spanish nationality The different methods for acquiring nationality are: Nationality by Spanish origins Nationality by possession of status Nationality by residence Nationality by option Nationality by naturalization

How can Spanish nationality be lost? Situations are different if the Spanish nationality has been acquired by origins or by other means

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF LEGAL ENTITIES Legal entities are also called juridical persons and the term “person” is indeed significant because they are treated in law as if they were natural persons (fictio juris). While human beings acquire legal personhood when they are born (or even before in some jurisdictions), juridical persons do so when they are incorporated in accordance with law. Legal personhood is a prerequisite to legal capacity, the ability of any legal person to amend rights and obligations.

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF MINORS The fundamental rights of minors are the human rights of children with particular attention to the rights of special protection and care afforded to minors. The 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child defines a child as "any human being below the age of eighteen years, unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier. " There are no definitions of other terms used to describe young people such as "adolescents", "teenagers", or "youth" in international law. The field of children's rights spans the fields of law, politics, religion, and morality.

RIGHTS OF MINORS IN SPAIN The Art. 12 of the Spanish Constitution states that in the Spanish system a minor is considered a person under the legal age of 18 years. The Spanish legal system provides a quite wide range of rights recognized to children, implementing the higher international legal standards in this field. In particular, Spanish laws protect the children's rights to association with both parents (in case they are separated), the right to develop their human identity as well as the basic needs for physical protection, food, Statepaid education, health care, and criminal laws appropriate for the age and development of the child.

RIGHTS OF MINORS IN SPAIN In Spain, many laws have also been implemented in order to guarantee an equal protection of the child's civil rights, and freedom from discrimination on the basis of the child's race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, religion, disability, color, ethnicity, or other characteristics. Interpretations of children's rights from Spanish judges range from allowing children the capacity for autonomous action to the enforcement of children being physically, mentally and emotionally free from abuse, though what constitutes "abuse" is a matter of debate.

THE VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL EFFECTIVENESS OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS What vertical and horizontal effects means? The distinction between these two effects is quite simple: when the private part sues a public body claiming a violation of one of his/her fundamental rights it is called vertical effect. Indeed, the legal system has a pyramidal structure and impose to the subjects which are in a superior position to respect the rights of those who are placed in a lower level.

VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL EFFECTS IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW ►The scope of application of individual rights and, in particular, their capacity to reach the private sphere is among the most fundamental issues in constitutional law. ►The issue of vertical and horizontal effects in constitutional law refer to whether constitutional rights regulate only the conduct of governmental actors in their dealings with private individuals (vertical) or also relations between private individuals (horizontal).

THE VERTICAL/HORIZONTAL EFFECTS ISSUE IN EU LAW An important exception is represented by the EU Law system. Here, the CJEU has clearly stated that EU norms regulating fundamental rights have both vertical and horizontal effects. In the Court’s case-law this position has been firstly expressed in the Walrave case (1974) , where it has been declared that Art. 7, which prohibits discrimination on the grounds of nationality, applies also to the defendant private organization. Subsequently, the Court handled down the Defrenne case (1976) judgment where it held that the principle of equal pay for male and female workers for equal work (contained in Art. 119 TFEU) applies also to private employers.

Fundamental Rights and their Guarantees Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

Guarantees of fundamental rights ► Judicial protection of rights. ► Special procedures. ► The individual complaint (recurso de amparo) before the Constitutional Court. ► The Ombudsman and similar institutions of the Autonomous Communities.

The fundamental rights protection in courts Fundamental rights enjoy a multilevel protection in the Spanish legal system. When the alleged violation concern the constitutional norm, the individuals should make a complain before the Constitutional Court (through a recurso de amparo). When the violation concerns a practical application of the right through an organic, ordinary or local law as well as through an administrative act, then the private person should make a complain before the tribunal that have competences in that specific field of law (criminal, civil or administrative).

The exercise of judicial power in Spain In accordance with the principle of jurisdictional unity, judicial power is assigned to the ordinary jurisdiction. However, special courts have been created in relation to different subject matters. These include courts dealing with violence against women, commercial courts and courts with special duties regarding criminal sentencing, as well as juvenile courts. In addition, the Spanish Constitution provides for certain courts which enjoy full independence and impartiality and are fully subject to the rule of law. These are the Constitutional Court, jury courts, the Court of Audit, the Military Court and the Court of Customary Law.

The constitutional protection of fundamental rights As regards the protection of fundamental rights, the Constitution provides for a specific and ultimate system to safeguard these rights: appeals brought on grounds of violation of Constitutional rights and freedoms, can only be heard by the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court is the supreme interpreter of the Constitution. Thus, it is a higher court which protects constitutional guarantees and is the ultimate guarantor of the fundamental rights and freedoms enshrined in the Constitution.

Recurso de Amparo is one of the main powers conferred by the Constitution to the Constitutional Court. The object of this process is the protection against breaches of the rights and freedoms enshrined in Arts. 14 to 30 of the Constitution originated by provisions, legal acts, omissions or simple actions of the government of the State, the Autonomous Communities and other public bodies of territorial, corporate or institutional nature, as well as their staff. The only claim that can be enforced through the amparo is the restoration or preservation of the rights or freedoms for which the appeal is lodged.

Persons entitled to fill an Amparo recourse Any natural or legal person claiming a legitimate interest, as well as the Ombudsman and the public prosecutor are entitled to lodge an appeal. Those persons favored by the challenged decision may also appear in the proceedings with the character of the defendant. Moreover, those people which show having a legitimate interest in the proceedings, may also appear. The prosecutor is involved in all amparo actions in defense of legality, the rights of citizens and public interest protected by law.

The relevance test It is unamendable and common to all forms of amparo that the applicant must justify the special constitutional relevance of the appeal lodged. This is a requirement that can not be confused with the very foundation of constitutional violation reported, so that the burden of justifying the special constitutional relevance of the appeal is somewhat different from arguing about the existence of a violation of a fundamental right the act or contested decision.

The judgment on the merit The judgment delivered on the substance of the appeal may grant or deny the requested protection (Amparo). Should be the protection be granted, the judgement will contain any of the following statements: Declaration of invalidity of the decision, act or contested resolution; Public recognition of the right or freedom violated; Restoration of the appellant in the integrity of his right or freedom by adopting appropriate measures, and where appropriate, for its conservation.

Quasi-jurisdictional authorities In addition to the possibility of filling a recurso de amparo before the Constitutional Court and claiming a violation before ordinary courts, the Spanish Constitution also envisages some quasi-jurisdictional authorities, such as: ► The Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo); ► The Public Prosecutor; ► The Attorney General.

The Ombudsman (Defensor del pueblo) The Ombudsman is the High Commissioner of the Parliament responsible for defending the fundamental rights and civil liberties of citizens by monitoring the activity of the administration and public authorities. Any citizen can request the intervention of the Ombudsman, free of charge, to investigate any alleged misconduct by public authorities and/or their agents. The office of the Ombudsman can also intervene ex officio in cases that come to its attention without any complaint having been filed.

Function and competences of the Ombudsman The Ombudsman can file appeal of unconstitutionality or appeal for legal protection of constitutional rights before the Constitutional Court. It monitors any violation of rights and can act on its own, opening actions or queries without waiting someone complains. The Ombudsman, during investigations, can make recommendations and suggestions to authorities and officials in the Public Administration regarding the adoption of new measures and reminds them of their legal duties. It prepares an annual report for the Parliament and publishes case reports on matters which require special attention. The Spanish Parliament attributed the functions of the National Preventive Mechanism against Torture (NPM) to the Defensor del Pueblo in 2009.

The Public Prosecutor is part of the judicial branch but has functional autonomy. Its purpose is to: ► Promote and defend the public interest; ► Ensure the legality and impartiality of the operation of justice; ► Protect the rights of specific groups, such as minors, people with disabilities and so on.

The Attorney General of the State (Fiscal General del Estado) heads the Public Prosecutor Office for the entire country. The Attorney General of the State acts in accordance with the principles of unified action, hierarchy and impartiality. The Attorney General of the State is appointed on a proposal by the government.

Fundamental Rights and their Limits Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

Limits and restrictions on fundamental rights & the principle of proportionality The configuration of fundamental rights: the legal reserve (reserve de ley). ► The proportionality principle and the essential content of rights as a guarantee. ► Limits and restrictions on fundamental rights. ► Suspension of fundamental rights. ►

The legal reserve (reserva de ley) In the Spanish legal system, the reserve de ley provides that the discipline of a given subject is regulated only by primary law and not by secondary sources. The reserve de ley has a guarantee function because it aims to ensure that in particularly delicate matters, as in the case of the fundamental rights, the decisions are taken by the most representative body of sovereign power: the parliament.

The legal reserve and fundamental rights The Spanish Constitution envisages different types of the reserve de ley, but for what concerns the fundamental rights protection, the reserve de ley is absolute: that is to say that any modification or limitation of these rights must be expressly envisaged by a constitutional or an organic law and not by other legal instruments such as for example, regulations, directives or even regional laws.

The Proportionality Principle Definition: Proportionality is a general principle in law which is used as a criterion of fairness and justice in constitutional law and it serves as a logical method intended to assist in discerning the correct balance between the restriction imposed by a corrective measure and the severity of the nature of the prohibited act.

The Proportionality Principle in the Spanish legal system In the Spanish Constitution, the principle of proportionality it is not expressly envisaged as a general principle of law, but it is often used by the Spanish constitutional court in order to decide cases when the protection of two different rights it is at stake. It therefore constitutes a judicial mechanism which is often used to solve disputes.

The Proportionality Principle in EU law To understand better what concretely is the proportionality principle, and which are the elements that compose it, we therefore must use European Union law, where this principle is expressly envisaged as one of the general principles regulating the application of EU law and its relationship with national EU member states’ laws. The principle of proportionality is laid down in Art. 5 of the Treaty on European Union (together with the principles of subsidiarity and attribution). The criteria for applying it are set out in the Protocol (No 2) on the application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality annexed to the Treaties.

The CJEU’s interpretation of the proportionality principle However, what is more relevant in our case is the application of the proportionality principle not to EU law matters but to fundamental rights, so we must rely on the interpretation provided by the Court of Justice of the EU to understand how this principle should be concretely applied in human rights cases. It is important to underline that the CJEU’s interpretation of the proportionality principle is also accepted and shared by the Spanish Constitutional Court and most of the constitutional courts of the EU member states.

LIMITS AND RESTRICTIONS ON FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS Are limits and restrictions on fundamental rights possible in a democratic legal order? The answer is certainly yes. Even though fundamental rights represent a pillar of democratic constitutions and an essential value for legal systems built on those constitutions, it would be unrealistic to not envisage any limitation and restriction on them. As it stems frome the previous conclusions that we made about the application of the proportionality principle, when it comes to fundamental rights, their protection should consider fully guaranteed if the essential content of the right at stake is saufeguarded.

Limitations and restrictions of fundamental rights in Spain The Spanish Constitution defines the first the level of legislation about the fundamental rights. The Constitutional Court (SCC) interprets the relation between constitutional norms and both the legislation on statutory level (organic and ordinary laws, decree-laws, legislative decrees and possibly administrative regulations) and the legislation on local level (Autonomous communities acts). In spite of the lack of a specific allegation, the SCC seems to adopt the same approach of the ECt. HR about the classification of fundamental rights. That is to say that some of these rights can be waived while others cannot.

Limitations and restrictions of fundamental rights in Spain As it is also established bt the ECt. HR, some fundamental rights, such as the prohibition of torture, the right to freedom, the right to a fair trial and the principle of nulla poena sine lege cannot be waived under any circumstances because such restrictions would turn a democratic legal order into an arbitrary one which is against the principles and the laws who allow member States to be part of the Council of Europe and, therefore, being subjected to the jurisdiction of the ECt. HR.

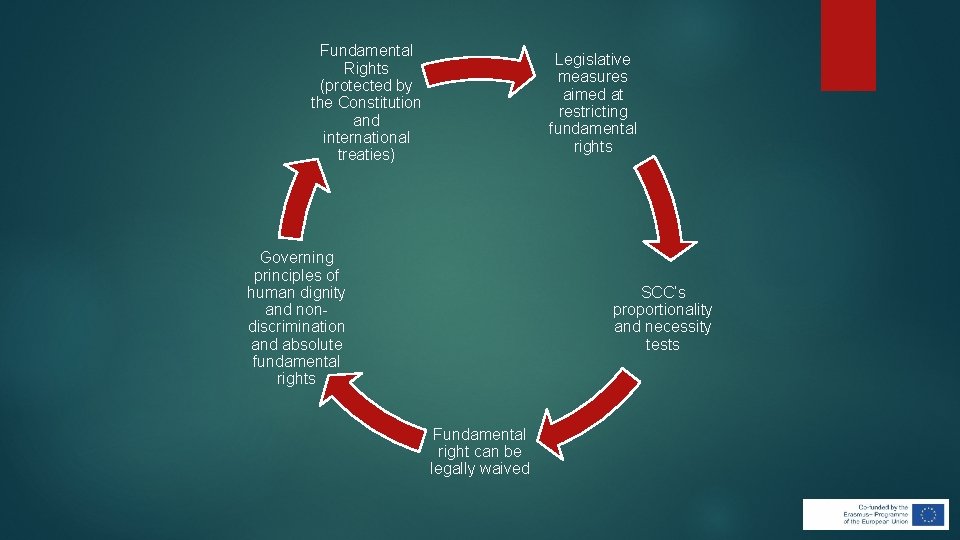

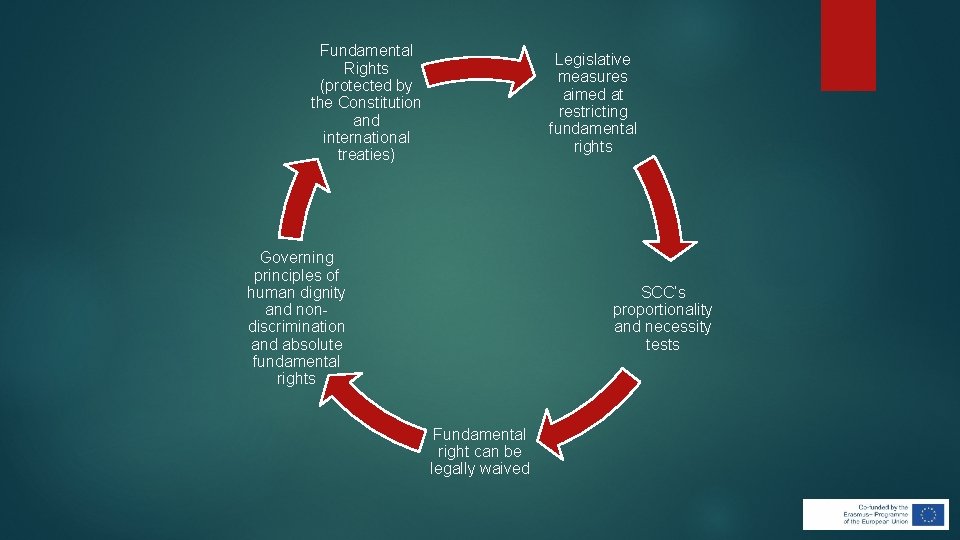

Fundamental Rights (protected by the Constitution and international treaties) Legislative measures aimed at restricting fundamental rights Governing principles of human dignity and nondiscrimination and absolute fundamental rights SCC’s proportionality and necessity tests Fundamental right can be legally waived

Suspension of fundamental rights The suspension of rights and freedoms is expressly envisaged in the Chapter 5 of the Spanish Constitution. Clearly enough, this is a quite extreme hypothesis that can happen only under specific circumstances. Fundamental rights and freedoms can be suspended only under those particular cases envisaged by the Constitution. Any other source of law, such as organic or ordinary laws, cannot add new conditions for the suspension of fundamental rights but should regulate those already provided by the Constitution.

What do limitations and suspension of fundamental rights have in common? Both limitations and suspension of fundamental rights can apply only to some fundamental rights with the exclusion of those of absolute nature. The SSC is entitled to verify the legitimacy of legislative measures that both limit or suspend fundamental rights. The concrete result produced by a valid act that limit or suspend a fundamental right is the same: that is to say its restriction in the scope and the content. Therefore, those persons or groups who will be disadvantaged by those measures will be compensate by other persons or groups that will be protected by them. The right to complain against a restrictive measure is always guaranteed to disadvantaged people. However, in case of measures suspending fundamental rights, the burden of proof for the claimant is much more demanding.

The Rights of the Individual and Private Sphere Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

The rights of the individual and private sphere ► The right to life and to physical and moral integrity. ► Freedom of ideology and religion. ► The right to a private life: privacy, honor, own image, home, secret of communications. ► Personal liberty and habeas corpus. ► Freedom of movement and residence. ► The right to marriage.

Freedoms of expression and information ► Freedoms of expression and information. ► Conflicts with the right to honor, privacy and own image. ► The rights of journalists. ► The right of artistic and scientific creation.

The right to life and… The right to life is a moral principle based on the belief that a human being has the right to live and, in particular, should not be killed by another human being. In human history, life has not been considered as an innate right to all the human beings for a very long time. Only the progressive evolution of the human rights doctrine has guaranteed the recognition of the right to life as an absolute and mandatory right which is currently central both in international law and national constitutional systems.

…the right to physical and moral integrity The right to physical and moral integrity is often linked to the right to life in national law but in international law they are regulated separately. For example, the ECHR expressly protect the right to life in Art. 2 and the right to physical and moral integrity under Art. 3 (prohibition of torture, inhuman and degrading treatments).

The right to life and to physical and moral integrity in the Spanish Constitution In Spain, the right to life and to physical and moral integrity are protected by the same constitutional provision which is Article 15. The article reads as follow: «Everyone has the right to life and to physical and moral integrity, and under no circumstances may be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading punishment or treatment. Death penalty is hereby abolished, except as provided for by military criminal law in times of war» . In line with the European Court of Human Rights’ approach, the Spanish Constitutional Court consider the right to life and to physical and moral integrity an absolute right which is not subjected to any restriction, not even those stemming from reasons of public order or national security.

Freedom of ideology can be described as the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints. Its philosophical roots go back to the age of Enlightenment (XVIII century) and it has a central position in Western moral traditions. Freedom of ideology is the precursor and progenitor of other liberties, including freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and freedom of expression. Though freedom of ideology is axiomatic for many other freedoms, they are in no way required for it to operate and exist. The conception of a freedom or a right does not guarantee its inclusion or protection via a philosophical caveat. Therefore, freedom of ideology is regarded as a main liberty from which other more specific rights and liberties find their roots.

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance, both in public and in private. It also includes the freedom to change one's religion or beliefs. In Western countries, freedom of religion is considered a fundamental human right, while in countries with a state religion (such as Islamic states) freedom of religion is generally considered to mean that the government permits religious practices of other sects besides the state religion and does not persecute believers in other faiths. In this case, however, freedom of religion is not considered as a fundamental right but religion is considered a practice tolerated by the law.

Art. 16: a symbol of the Spanish transition to democracy In Spain, the transition to democracy established a new Constitution in 1978 that has disestablished Catholicism as the state religion. Since then, Spain is no longer officially a Catholic country, as it was for many centuries, a few years aside. Therefore, Article 16 represents one of the most emblematic provision which shows the transition from autocracy to democracy in Spain: on the one hand it gives back to citizens the absolute right to hold their personal thoughts (freedom of ideology) and, on the other hand, it recognize the secular nature of the State, protecting at the same time, the right of any person to profess their faith (freedom of religion).

The right to a private life In Spain the right to a private life is also composed by various elements which are enumerated in the words of Article 18 which represent the constitutional provision that protect the right to a private life. Art. 18: «The right to honour, to personal and family privacy and to the own image is guaranteed. The home is inviolable. No entry or search may be made without the consent of the householder or a legal warrant, except in cases of flagrante delicto. Secrecy of communications is guaranteed, particularly regarding postal, telegraphic and telephonic communications, except in the event of a court order. The law shall restrict the use of data processing in order to guarantee the honour and personal and family privacy of citizens and the full exercise of their rights» .

Privacy, honor, own image, home, secrecy of communications It stems from Article 18 that the constitutional protection of the right to a private life in Spain includes: • • • Personal and family privacy; Honor; Own image; Home; Secrecy of correspondance.

The right to personal liberty The right to liberty and security of the person entails two distinct rights: The right to liberty of the person; The right to personal security.

Freedom of movement and residence Freedom of movement is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country, and to leave the country and return to it. The right includes not only visiting places but changing the place where the individual resides or works. Such a right is provided in the constitutions of numerous states as well as in international law norms. Freedom of residence is closely connected with the freedom of movement and consists in the free choice of an individual to establish his/her residence within the territory and the jurisdiction of the selected country. Like the freedom of movement, also freedom of residence is normally subjected to some restrictions which can be required by administrative and public laws in order to mantain and guarantee the respect of the public order.

Eu regulation of the freedom of movement and residence In all the EU member states the internal regulation of freedom of movement and residence has been substantially influenced by the development of the EU law. Freedom of movement and residence represents, indeed, a specific aspect of the general freedom of movement guaranteed to all individuals between the EU borders. The original treaty that abolish controls on the borders and therefore guarantee freedom of movements for all individuals was the Schengen treaty (1985) that has been inserted into EU with the Amsterdam treaty (1997). The Schengen treaty originally included some non EU member states such as Switzerland Norway and do not include some other countries which have joined the EU afterwards, such as Bulgaria, Cyprus and Romania (which are however obliged to participate in the Schengen agreement since they are now part of the EU)

The right to marriage protects the right of men and women of marriageable age to marry and to start a family. The right to marry is subject to national laws on marriage, including those that make marriage illegal between certain types of people (for example, close relatives). The difficulty in guarantee a fair application of the right to marriage are mainly due to the fact that in some countries the right to marriage has not been secularized but read in connection with some religious interpretations or rules (for example, concerning the prohibition of same-sex marriages). Although any State is able to restrict the right to marry, any restrictions must not be arbitrary and not interfere with the essential principle of the right. This include any type of discrimination, also those based on sexual orientation (therefore the prohibition of same-sex marriages is a clear and direct discrimination based on sexual orientation)

Freedom of expression In Spain, freedom of expression is protected under Art. 20 CE. The right is also enshrined in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, Article 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights and Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. Freedom of expression is understood as a multi-faceted right that includes not only the right to express, or disseminate, information and ideas, but three further distinct aspects: ► the right to seek information and ideas; ► the right to receive information and ideas; ► the right to impart information and ideas International, regional and national standards also recognize that freedom of expression, includes any medium, whether it be orally, in written, in print, through the Internet or through art forms.

Conflicts with the right to honor, privacy and own image The most important relations of freedom of expression with other rights are those regarding the potential conflict with some aspects of the right to private life. As we have seen before, the right to private life is composed by multiple elements, such as the right to honor, privacy and own image. In some cases, those rights might oppose to the freedom of expression. Therefore, since both freedom of expression and right to privacy are constitutionally protected rights, it is important for the constitutional judges to evaluate which one of the competing rights should take precedence in the concrete case.

Freedom of information is an extension of freedom of expression in any medium, be it orally, in writing, print, through the Internet or through art forms. This means that the protection of freedom of expression as a right includes not only the content, but also the means of expression. Freedom of information also refers to the right to privacy in the content of the Internet and information technology. As with the right to freedom of expression, the right to privacy is a recognised human right and freedom of information acts as an extension to this right.

Freedom of information and internet censorship Is Internet censorship compatible with freedom of information? The answer is not easy and mostly depends on the degree of freedom of information guaranteed in that State. Freedom of information is universally deemed to be a fundamental right but allow for limitations so it does not have absolute nature. Internet censorship is therefore a limitation of freedom of information and might be legitimate under certain circumstances. However, if it is applied systematically, it might cancel the content and the scope of freedom of information and therefore be not compatible with it.

The rights of journalists ► The main rights of journalists that have a constitutional basis are three: ► Journalists claim free access to all information sources, and the right to freely inquire on all events conditioning public life. Therefore, secret of public or private affairs may be opposed only to journalists in exceptional cases and for clearly expressed motives. ► The journalist has the right to refuse subordination to anything contrary to the general policy of the information organ to which he collaborates. ► A journalist cannot be compelled to perform a professional act or to express an opinion contrary to his convictions or his conscience.

The duties of journalists The essential duties of the journalists are: ► To respect truth whatever be the consequence to himself, because of the right of the public to know the truth; ► To defend freedom of information, comment and criticism; ► To report only on facts of which he knows the origin; ► Not to use unfair methods to obtain news, photographs or documents; ► To restrict himself to the respect of privacy; ► To observe professional secrecy and not to divulge the source of information obtained in confidence; ► To resist every pressure and to accept editorial orders only from the responsible persons of the editorial staff.

Freedom of artistic expression can be defined as "the freedom to imagine, create and distribute diverse cultural expressions free of governmental censorship, political interference or the pressures of non-state actors. “ Generally, artistic freedom describes the extent of independence artists obtain to create art freely. Moreover, artistic freedom concerns "the rights of citizens to access artistic expressions and take part in cultural life and thus represents one of the key issues for democracy. “

The Right to Equality Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

The principle of equality Equality in law and equality in the application of the law. The right not to be discriminated because of specific causes. Equality and affirmative actions.

Equality before the law: a general perspective Equality before the law is a general principle of law that is composed by two elements: The first element ensure that any individual must be treated equally by the law (principle of isonomy) The second element ensure that any individual is subject to the same laws of justice (due process). Equality before the law is one of the basic principles of modern constitutionalism and it arose from various important and complex questions concerning equality, fairness and justice.

Substantial and procedural equality The principle of equality covers both substantial and procedural aspects of law. From the perspective of substantial law, the principle of equality is incompatible and ceases to exist with legal systems that still recognize discriminatory practices, from the relatively older cases of slavery, servitude and colonialism to the most recent ones concerning discrimination against minorities on a ethnical or religious grounds. From the perspective of procedural law, the principle of equality forbid any restriction to the possibility of enjoying a fair trial or an effective legal protection. The rights to a fair trial and to an effective legal protection enjoy absolute nature and cannot be derogated towards any individual.

Guarantees of equality The general guarantee of equality is provided by most of the world's national constitutions, but specific implementations of this guarantee vary. For example, while many constitutions guarantee equality regardless of race, only a few mention the right to equality regardless of nationality. However, while the international practice recognizes that different treatments between citizens and foreigners can be justified under specific grounds, this is not allowed when, for example, equality is not guaranteed on a gender or a religious basis.

The principle of equality before the law in the Spanish Constitution In the Spanish Constitution, the principle of equality before the law enjoys a central position. It is effectively placed just before the beginning of Chapter II, Title 1 of the Constitution, which contains the nucleos of the constitutionally protected fundamental rights and it suggests for a very broad application to all the subsequent provisions (until Art. 30). In connection with some allegedly violated material rights, it can be subject to amparo recourse. The Constitutional Court gave a meaningful interpretation of Art. 14 in the judgment 49/1982 (Metasa case) where it recognized that equality before the law is not only a general principle of law but it establish an effective substantial right for citizens to obtain an equal treatment both in theoretical and practical terms.

Forms of discriminations Discriminations can have various forms and all of those should be prohibited by the law. There is no a generally valid classification of the various forms of discriminations but in the EU context the harmonization directives have strongly contributed to equalize the different member States legislations which nowadays are pretty much similar. Following the classification provided for EU law, we can distinguish four different types of discriminations. - Direct discrimination; - Indirect discrimination; - Harrasment; - Instructions to discriminate.

The international and EU legal framework against discrimination The principles of equality and non-discrimination are part of the foundations of the rule of law. The international human rights legal framework contains international instruments to combat specific forms of discrimination, including discrimination against indigenous peoples, migrants, minorities, people with disabilities, discrimination against women, racial and religious discrimination, or discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Some International instruments concerning anti-discrimination Charter of the United Nations, 1945 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, 1965 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979 Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989

European Convention on Human Rights, 1950 The European Convention on Human Rights differs from the other general human rights treaties in that it does not contain an independent prohibition on discrimination but only a prohibition that is linked to the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Convention and its Protocols. This means that allegations of discrimination that are not connected to the exercise of these rights and freedoms fall outside the competence of the European Court of Human Rights. Article 14 reads: “The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status. ”

Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, 1994 The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities is a unique instrument in that it is “the first ever legally binding multilateral instrument devoted to the protection of national minorities in general”. Article 1 of this Convention also makes it clear that “the protection of national minorities and of the rights and freedoms of persons belonging to those minorities forms an integral part of the international protection of human rights, and as such falls within the scope of international co-operation. ” Moreover, as pointed out in the sixth preambular paragraph to the Convention, “a pluralist and genuinely democratic society should not only respect the ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity of each person belonging to a national minority, but also create appropriate conditions enabling them to express, preserve and develop this identity. ”

The right to equality and prohibition of discrimination in EU law In the EU context, the aim of non-discrimination law is to allow all individuals a fair prospect to access opportunities available in a society. This principle essentially means that individuals who are in similar situations should receive similar treatment and not be treated less favourably simply because of a particular ‘protected’ characteristic that they possess. The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits discrimination on grounds of nationality. It also enables the Council to take appropriate action to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation.

The right to equality and prohibition of discrimination in EU law In 2009, the Lisbon Treaty introduced a horizontal clause with a view to integrating the fight against discrimination into all EU policies and actions (Article 10 TFEU). In this area of the fight against discrimination, a special legislative procedure is to be used: The Council must act unanimously and after obtaining the European Parliament’s consent. EU citizens may exercise their right to judicial recourse in cases of direct or indirect discrimination, specifically in cases where they are being treated differently in comparable situations or when a disadvantage cannot be justified by a legitimate and proportional objective.

The Right to a Fair Trial Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

Due process & Principle of criminal legality The right to a fair trial and to an effective judicial protection without defenselessness The guarantees of the process The fundamental right to an impartial judge The principle of legality in criminal matters

Due process is the legal requirement according to which the state must respect all the legal rights that are owed to a person. Due process balances the power of law of the land (territorial law) and protects the individual persons from it. When a government harms a person without following the exact course of the law, this constitutes a due process violation, which, in turn, offends the rule of law. Due process is generally deemed to be an absolute right and it finds its roots in national constitutions and under customary international law. Before the raising of international human rights law, due process was limited to guarantee a basic minimum level of justice and fairness and it was regulated by the doctrine of national treatment.

The right to a fair trial and to an effective judicial protection Due process can be seized into two particularly relevant sub-rights: The right to a fair trial The right to an effective judicial protection

The right to a fair trial When a person is charged with a crime, or involved in some other legal disputes, he/she has the right to a fair trial. Fair trial is a complex notion and entails the guarantee of a fair and public hearing to be concluded within a reasonable time and carried on by an independent and impartial court. Various rights associated with a fair trial are explicitly proclaimed in international treaties and national constitutions. There is no binding international law that defines specifically what is a fair trial and the definition varies from one legal system to another.

Relationship with other rights The right to equality before the law is sometimes regarded as part of the right to a fair trial. It is typically guaranteed under a separate article in international human rights instruments (i. e. art. 6 and 14 of the echr). This right entitles individuals to be recognised as subject, not as object, of the law. International human rights law permits no derogation or exceptions to this human right. Closely related to the right to a fair trial is the principle of legality and its corollary of prohibition of retroactive law (nulla poena sine lege).

The right to an effective remedy What is the right to an effective remedy? It is the right that gives to individuals the possibility of filling an official complaint to the competent body in order to report the alleged violation of a certain right. Normally it refers to judicial remedies but also administrative and other kind of public remedies should be included into the notion of the right to an effective remedy. Human rights law imposes an obligation on countries to provide remedies and reparation for the victims of human rights violations.

The right to a fair trial and to an effective remedy in the Spanish Constitution The Spanish constitution encompasses the protection of the right to an effective remedy under the same provision of the right to a fair trial: art. 24. Instead, human rights conventions include various measures aimed at ensuring effective remedies for persons whose human rights have been violated. The remedies have partly been included in the provision on fair trial, partly in separate provision. For instance, the European Convention stipulates the right to access to court in Article 6, the right to an effective remedy in Article 13 and actual reparations in Article 41.

The legal aid Art. 24 of the Spanish Constitution provides that every person has the right to be assisted and defended by a lawyer in order to avoid that anyone can go undefended. Therefore, we can say that the free legal aid provided in the Constitution is a consequence of the need of protection of that fundamental right. The free legal aid does not include just free lawyer assistance but also other benefits like representation by a Procurator if necessary, advisement, legal assistance to detainees, free legal publications, exemption from the payment of court fees as well as free expert assistance inter alia.

The guarantees of the process are both substantial and procedural. Procedural guarantees provide the process that a case will go through (whether it goes to trial or not). The procedural guarantees determine how a proceeding concerning the enforcement of substantive law will occur. Substantive guarantees defines how the facts in the case will be handled, as well as how the crime is to be charged.

The fundamental right to an impartial judge The right to an impartial judge could be defined as the right that guarantee to the parties that the actions and decisions of the judge will be free of bias, prejudice and of any personal interest. All people, regardless of race, religion, sex, national origin, or economic status, have the right to a trial by a fair and impartial judge. The right to an impartial judge do not only consist in the right to be judged by an impartial judge but also entails a number of other guarantees such as those of: ensuring that the sanction has been previously ascertained by the law, the accused person has been informed of the nature, cause of the accusation and confronted with the witnesses against him.

The principle of legality in criminal matters Art. 25 provides for a comprehensive application of the principle of legality in criminal and administrative matters. In particular, the application of the principle of legality in criminal matters is closely related to the fundamental rights protection system. In criminal matters, the implementation of the principle of legality through organic and ordinary laws has played a central role in ensuring the effectiveness and the equality of the legal system. Art. 25 is a fundamental pillar of the current Spanish system of criminal justice in which the examining magistrate is the head of the investigation of a specific crime and any other matters that may relate to that particular offence.

Political Rights Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

POLITICAL RIGHTS The rights of assembly and demonstration. Political parties and the right of association. The right to participate in public affairs and access to public offices. The right to vote. The right to petition.

The right of assembly is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ideas. Somehow it is referred as freedom of assembly as, in this case, there is no substantial difference between the terms “right” and “freedom”. Basically the right to assembly ensures people can gather and meet, both publicly and privately.

The scope of the right The right to peacefully assemble belongs to all individuals, including persons espousing minority or dissenting views or working on sensitive issues, such as human rights defenders, trade unionists, and migrants. States have a responsibility to ensure that the right to freedom of assembly is protected, especially when those who assemble protest against public policies and challenge the State. The right to peacefully assemble comprises the right to freely choose the location and the timing of the assembly, including public streets, roads and squares. The right to assemble online must also be fully guaranteed.

The right to demonstration The right to assembly is closely connected to the right of demonstration. While no human rights instrument or national constitution grants the absolute right to protest, such a right to protest may be a manifestation of the right to freedom of assembly, the right to freedom of association, and the right to freedom of speech. Many international treaties contain clear articulations of the right to protest which is enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights, (Articles 9 to 11); and in the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Articles 18 to 22).

The right of association The right (or freedom) of association is composed by three elements: The individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily; The right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members; The right of an association to accept or decline membership based on certain criteria.

The right of association Freedom of association is mainly manifested through the right to join a trade union, to engage in free speech or to participate in debating societies, political parties, or any other club or association (including religious denominations and organizations, fraternities, and sport clubs). It is closely linked with freedom of assembly as this latter is typically associated with political contexts.

The right to participate in public affairs and access public offices The right to participate in public affairs is also composed by different sub-rights that include the possibility for citizens to participate: ► Directly by voting in referenda, by being elected, or by participating in other means of direct democracy. ► Through freely chosen representatives that are elected according to the election laws; ► Through consultative processes; ► Through debate and dialogue; ► Individually and with others; ► By establishing and joining organizations, including civil society organizations, unions and political parties; and through equal access to public service positions, including employment in public positions.

The right to participate in public affairs and the national citizenship The right to participate in public affairs is unusual in that it is limited to citizens. Therefore, democratic States should carefully regulate the required conditions to possess the citizenship, especially for those that are not national born. The legal requirements and provisions for obtaining citizenship should not be overly restrictive nor discriminatory. Citizenship is at the very basis of the enjoyment of political rights, especially for what concerns the possibility to vote, participate in public affairs and access to public offices.

The right to vote (also called suffrage in English) is often conceived in terms of elections for representatives. However, the right to vote applies equally to referenda and initiatives. The right to vote describes not only the legal right to vote, but also the practical question of whether a question will be put to a vote. The right to vote is granted to qualifying citizens once they have reached the voting age. What constitutes a qualifying citizen depends on the government's decision. Resident non-citizens can vote in some countries, which may be restricted to citizens of closely linked countries (e. g. , Commonwealth citizens and European Union citizens).

The right to vote in the Spanish Constitution is outlined in Art. 23, par. 1 for Spanish citizens and also recalled in art. 13, par. 2 (as modified by the first constitutional reform in 1992) under the principle of reciprocity foreigners. Art. 23: Citizens have the right to participate in public affairs, directly or through representatives freely elected in periodic elections by universal suffrage.

The right to vote in EU law The most important EU law sources that regulate the right to vote are the Council Regulations 975/99 and 976/99 (1999) These regulations provide a legal basis for EU operations that “contribute to the general objective of developing and consolidating democracy and the rule of law and to that of respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms”. They state that the EU shall provide technical and financial aid for operations aimed at supporting the process of democratization, in particular in support for electoral processes.

The right to petition is the right to make a complaint to, or seek the assistance of, one's government, without fear of punishment or reprisals. In Spain this right is outlined in Article 29 of the Constitution. As the other political rights, also the right to petition is closely linked with citizenship so that is why the constitutional provision is expressly addressed to Spaniards. However, the concept of citizenship has been largely extended during the past twenty years, especially thanks to the development of EU law and the jurisprudence of the CJEU.

The right to petition in EU law Since the entry into force of the Treaty of Maastricht, every EU citizen has had the right to submit a petition to the European Parliament, in the form of a complaint or a request, on an issue that falls within the European Union’s fields of activity. Petitions are examined by Parliament’s Committee on Petitions, which takes a decision on their admissibility and is responsible for dealing with them. Legal basis ► Articles 20, 24 and 227 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) ► Article 44 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU. Objectives ► The right to petition aims to provide EU citizens and residents with a simple means of contacting the European institutions with complaints or requests for action.

Economic and Social Rights Alejandro Saiz Arnaiz Marco Bocchi Department of Law Pompeu Fabra University 575046 -EPP-1 -2016 -1 -ES-EPPJMO-CHAIR

Economic and social rights in the Spanish Constitution Right to education and academic freedom. Right to work. Right to freely join trade unions and the right to strike. The right to private property. Freedom of enterprise.

Right to education The right to education is an important feature of democratic states. Differently from the past, when education was a privilege, now it is considered a human right in most of the national constitutions. Education as a human right means: ► The right to education is legally guaranteed for all without any discrimination; ► States have the obligation to protect, respect, and fulfil the right to education; ► There are ways to hold states accountable for violations or deprivations of the right to education.

The right to education in the Spanish Constitution The right to education is protected in Art. 27 of the Constitution. This article provides a comprehensive protection of the right to education and encompasses both entitlements and freedoms, including the: ► Right to free and compulsory primary education ► Right to available and accessible secondary education ► Right to equal access to higher education on the basis of capacity made progressively free ► Right to fundamental education for those who have not received or completed primary education ► Right to quality education both in public and private schools ► Freedom of parents to choose schools for their children which are in conformity with their religious and moral convictions ► Freedom of individuals and bodies to establish and direct education institutions in conformity with minimum standards established by the state ► Academic freedom of teachers and students

Right to work The right to work is the concept that people have a human right to work, or engage in productive employment, and may not be prevented from doing so. The right to work is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and recognized in international human rights law through its inclusion in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, where the right to work emphasizes economic, social and cultural development.

Labour rights The expression labor rights indicates a group of legal and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers, codified in national laws for implementing the constitutional protection of the right to work. In general, these rights influence working conditions in relations of employment. One of the most central is the right to freedom of association, otherwise known as the right to organize. Workers organized in trade unions exercise the right to collective bargaining to improve working conditions. In Spain most (but not all) the labour rights are envisaged by the Workers’ Statute.

The right to freely join trade unions A trade union is an association of workers forming a legal entity which acts as bargaining agent and legal representative for a unit of employees in all matters of law or right arising from or in the administration of a collective agreement. Trade unions typically fund the formal organisation, head office, and legal team functions of the trade union through regular fees or union dues. The delegate staff of the work union representation in the workforce are made up of workplace volunteers who are appointed by members in democratic elections

The trade union representation system in Spain follows the ‘audience' model (based on electoral representativeness rather than on membership) as it combines limited active participation and low commitment in membership terms with high participation in trade union elections, thus transferring the responsibility for defending workers’ interests to trade union representatives. During the crisis period (2007– 2012), the number of workers and companies decreased, and so did participation levels. After the 2012 and the economic recovery, the participation levels increased again.