An Dementia and Best Interest principles Liz Champion

An Dementia and Best Interest principles. Liz Champion Lead Nurse for Dementia Care Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust Liz. champion@nhs. net 01892 633738 dy ou rs

Aims of the session • • • Clarify who is a decision-maker. Identify the principles to consider. Clarify documentation of best interests meetings. Discuss conflicting concerns and settling disputes Explain Lasting Power of Attorney. Best Interest meeting’s

Any act done for, of any decision made on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made , in that person’s best interests. • Always assume capacity to make a decision or act, unless proven otherwise. • This concept was developed by the courts in relation to people who lacked capacity to make decisions for themselves, mainly concerned with the provision of medical treatment or social care. • The principle is the same whether the person that is making the decision or acting for the person is a family carer, paid care worker, attorney, court-appointed deputy or a healthcare professional. • It is also the same whether the decision is a minor issue or a major issue. • The only exceptions are where a person has made an advance decision to refuse treatment and, in specific circumstances, the involvement of the person in research.

The Decision-maker • The person making the decision is referred to as the ‘decision-maker’, and it is their responsibility to work out what is in the person’s best interests. Examples of decision-makers are: • The carer most directly involved with the person for day to day actions or decisions. • The doctor or healthcare staff where the decision involves the provision of medical treatment – the person responsible for carrying out the particular treatment is the decision maker. • The nurse or paid carer where the decision is about nursing or paid care. • The Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) when decisions are within the scope of their authority. • As when assessing someone’s capacity, many different people may be required to make decisions or act on behalf of someone who lacks capacity.

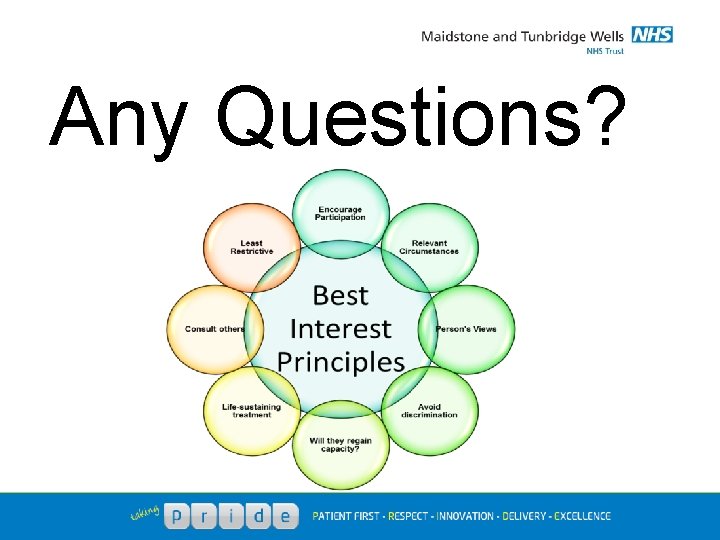

Best Interest Principles

Common factors to consider when making a best interests decision. • Encourage Participation Do whatever is possible to encourage the person to take part in making the decision. Remember – the person may not have the capacity to make the decision, but they may still have the ability to understand what is being said, and wish to contribute to the discussions. • Identify all relevant circumstances Try to identify all the things the person would take into account that are most relevant to that particular decision. Remember – relevant circumstances will vary from case to case and person to person.

• Find out the person’s views. What are their past and present wishes and feelings, any beliefs and values (religious, cultural, moral or political) that would be likely to influence their decision. Remember – these will not necessarily be the deciding factor, the assessment must consider them but the final decision must be based entirely on what is in the person’s best interests. Other factors might include the effect of the decision on other people and what the person would have considered in these circumstances. Also remember that the person’s actions in relation to particular things may have changed since they had their diagnosis, and this may mean their views have changed.

• Avoid discrimination Assumptions should not be made simply on the basis of age, appearance, condition or behaviour. Remember – the person with dementia that lacks capacity did not always lack capacity and therefore should not be discriminated against due to their condition, behaviour or diminishing abilities. • Assess whether the person might regain capacity. If after medical treatment will the person regain capacity, if so, can the decision wait until after then. Remember – people with dementia also have medical problems that may affect their capacity e. g. delirium, therefore should still be treated for these problems if possible prior to the decision.

• If the decision concerns life- sustaining treatment. Assumptions should not be made about the person’s quality of life, nor be motivated by a desire to bring about the person’s death. Remember – ‘life- sustaining’ treatment depends not only on the type of treatment but also the particular circumstances in which it is prescribed e. g. in some situations giving antibiotics may be life-sustaining. Before deciding to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment, the decision-maker must consider the range of treatment options available and any statements that the person has previously made about their wishes and feelings. If a written statement has been made in advance this should be taken into account, if an advance decision has been made in advance this cannot be ignored if it meets the Act’s requirements and applies to the person’s circumstances.

• Consult others If it is practicable and appropriate to do so to see if they have any particular information. In particular try and consult anyone previously named by the person as someone to be consulted; anyone engaged in caring for the person; any Lasting Power of Attorney; any deputy appointed by the court of protection. For decisions about major medical treatment or where a person should live and where there is no-one to consult an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) must be consulted. Remember – when consulting any of the above, the person who lacks capacity still has the right to keep their affairs private.

• Avoid restricting the person’s rights. See if other options may be less restrictive of the persons rights. Remember – it is the person’s rights we are looking at, and what may be less restrictive for them, not what others may feel is the best option – this is particularly pertinent when looking at where the person should live. Take all of this into account. Weigh up all these factors in order to work out a person’s best interests. This is not a simple process and you should ensure that you have included where appropriate all of these factors before reaching a decision. What is in a person’s best interests may change over time; this means that even if similar actions need to be taken repeatedly in connection with the person’s care or treatment, the person’s best interests should be regularly reviewed.

Documentation • This will be specific to your organisation. • Ensure a record is kept of the process of working out best interests for each relevant decision. • It should include: o Capacity assessment o What the decision to be made is, and what steps have been taken to assist the person to make this decision themselves. o How the decision was reached. o What the reasons for reaching the decision were. o Who was consulted to help work out best interests. o What factors were taken into account. o What options were considered, risks and benefits related to these options, and outcomes for each option.

Conflicting Concerns. • • Family members, partners and carers may disagree between themselves, or they might have different memories about views expressed by the person in the past. Carers and family might disagree with a professionals view about the person’s care or needs. The decision-maker will need to find a way of balancing these concerns or deciding between them. An agreement may be reached at a meeting to air everyone’s concerns, but this may or may not be in the person’s best interests. Ultimate responsibility falls to the decision-maker. People with conflicting interests should not be cut of the process. The decision-maker needs to ensure the interests of those consulted do not overly influence the process of working out the best interests of the person who lacks capacity.

Settling Disputes • There are several options to challenge a decisionmakers conclusion. o Involve an advocate to act on behalf of the person. o Get a second opinion. o Hold a case conference. o Pursue a complaint through the organisations formal procedures. If all the above fail, an application to the Court of Protection will need to be made.

Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) • • Where the health and welfare attorney has the appropriate powers (including, in the context of decisions about life-sustaining treatment, the power to consent to or refuse treatment) and the LPA has been registered with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG), the attorney is the lawful decision-maker. They must, however, follow the principles of the MCA – including fulfilling the duty to consult with others – and can only act in the person’s best interests. Ask to see the original LPA (embossed with ‘validated – OPG’ at the bottom of each page) and check that it does indeed confer the appropriate powers required for the decision. Identify if a joint LPA if it is held jointly or severally for decisions. Being named as ‘next of kin’ on medical records does not grant any legal right of decision making, and those close to the person cannot give consent to or refuse treatment on that person’s behalf, unless formally appointed as a health and welfare attorney or court-appointed deputy. If there is doubt that the attorney is acting in the best interests of the person, this should be resolved as soon as possible. Contact the OPG. If this continues then the Court of protection should be involved. Attorneys cannot be compelled to make a decision. In this situation they exempt themselves from the decision making process and responsibility will fall to the relevant clinician.

Best Interest Meetings • • o o o o o These are not actually required by the MCA, but are a good way of making important healthcare decisions and advocated by NICE. The meeting should: Involve the person themselves, unless it is contrary to their best interests. Consult carers, family, friends, advocates and any attorney or deputy about the meeting in advance, giving them time to ask questions and give their opinions. Careful planning, preparation and gathering of information maximise effectiveness of best interest meetings, including where and when meetings are held and who is involved and identifying the issue to be discussed. Members of the healthcare team and those close to the person should be equally involved in the meeting. Allow sufficient time for everyone to contribute to the meeting. Clarify the role of each person attending. Provide all information in an accessible format. Circulate a detailed note of the meeting to all those attending to check accuracy before it is finalised. Decision-makers should specify a timely review of the implementation of the actions resulting from the best interests decision.

Conclusion • • Applying best interests principles may not be a quick process. The person lacking capacity should be placed at the heart of the decision. The aim is to determine what the person would have done, said or felt, if they still had the capacity to express these views. The process in not ultimately about anyone else or what they believe; it is about the person who lacks capacity. Decisions should always be made so that the least restrictive option is considered first and where possible actioned. If the least restrictive option is not possible it will help ascertain which of the remaining options is closest but safe at the same time. The MCA protects the rights of people with dementia to make decisions for themselves, with support if necessary, even if others don’t agree with the decision or think it unwise. Best Interests decisions – and the procedures for making them – are critical if the MCA and its code of practice are to be well implemented.

Any Questions?

- Slides: 18