Ambulatory Near Miss Event Reporting Remediation and Disclosure

Ambulatory Near Miss Event Reporting, Remediation, and Disclosure: An opportunity to improve quality and safety Steven Crane, MD Natascha Lautenschlager, MD

Goals: • Engage seminar participants in a robust discussion of using near-miss reporting to improve safety in residency practices, develop new models of performance improvement, and expand curricula to improve residents’ skills about having frank discussions with their patients about lapses in safety.

Objectives • Understand where and how safety lapses occur in ambulatory practice. • Share ideas about how to adapt performance improvement programs to quickly remediate errors that pose a significant safety risk. • Discuss the implications of error disclosure for professionalism curricula in residency programs.

Outline • Review background of near-miss reporting and disclosure • Describe methods of our intervention • Present results • Discuss implications and limitations • Conclusions and next steps

Background—Errors in Medicine • Errors are a common cause of adverse events in medicine • 70% of medical encounters take place in ambulatory settings • Little is known about the frequency, cause, or seriousness of these errors.

Background—Near-miss events • Near-miss event: A deviation from a planned or expected process of care that COULD have resulted in harm to the patient, but was averted before ANY harm was done. • An opportunity to study errors before they cause patient harm • Practically easier to study than actual adverse events

Background--Disclosure • Disclosing errors and apologizing to patients is an important task for physicians. – Fulfilling ethical responsibility to patients – Activating patients to be involved in preventing errors – Reducing malpractice claims • Most physicians have little training in having these difficult discussions

Methods—Near Miss Reporting • Recruited 7 practices in Western NC to participate. • Agree to report at least 10 near-miss events per month for 6 month and initiate one practice improvement project based on reports • $14000 per practice if met minimum requirements

Methods—Near-miss coding • Used previously published taxonomy of ambulatory errors. • Trained 6 physician coders • Coded 630 near-miss events • 10% sample blindly coded by second coder

Methods--Disclosure • Designed parallel scenarios – Potential for serious harm – One patient knows the error occurred; the second patient doesn’t know – Open/closed questions concerning feelings/attitudes • Administered to 100 patients, and 60 physicians

Results—Near Miss Reports • 770 near-miss errors recorded in 12 months • The first 632 events coded by trained external coder – 10% coded by second coder – 70% coder agreement to 3 levels of detail – 87% to 2 levels of detail

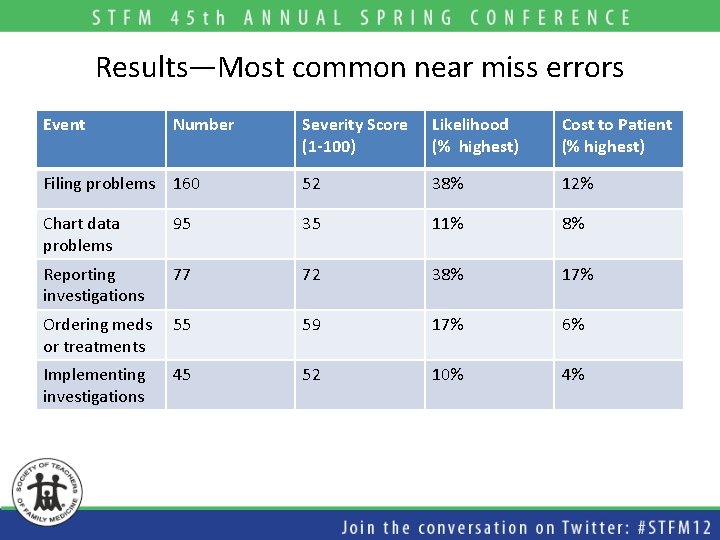

Results—Most common near miss errors Event Number Severity Score (1 -100) Likelihood (% highest) Cost to Patient (% highest) Filing problems 160 52 38% 12% Chart data problems 95 35 11% 8% Reporting investigations 77 72 38% 17% Ordering meds or treatments 55 59 17% 6% Implementing investigations 45 52 10% 4%

Results—EMR related errors • 14% of reported errors thought to be caused by the EMR – 21% of filing errors – 40% of ordering medication errors • Third highest severity score

Practice leaders focus group results: General Themes • Practices invested in quality • Anonymity empowered staff to report errors • Reports generated a lot of information— difficulty in handling the volume • Reminders probably more important than incentives in getting staff to report errors.

Practice change related to near-miss events • Problems were typically divided into those that could be changed, and those that couldn’t. • Practices tended to focus on the “quick-fixes” • CQI didn’t lend itself well to fixing these problems. • Most practices plan to continue using the system after the study ended.

Disclosure Surveys--results • 132 patients asked to participate; 103 started survey; 99 completed. 21 patients required some assistance to complete the survey. • 45 clinicians of the 75 clinicians in the study participated (60%); another 8 of 39 community primary care physicians completed surveys.

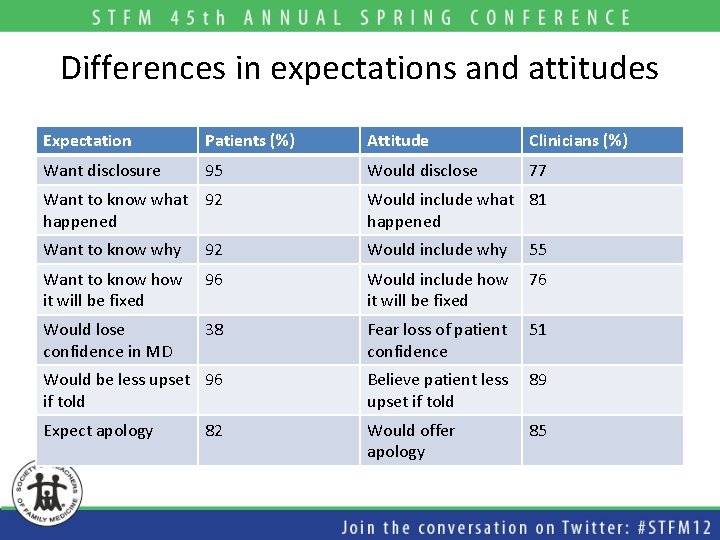

Differences in expectations and attitudes Expectation Patients (%) Attitude Clinicians (%) Want disclosure 95 Would disclose 77 Want to know what 92 happened Would include what 81 happened Want to know why 92 Would include why 55 Want to know how it will be fixed 96 Would include how it will be fixed 76 Would lose confidence in MD 38 Fear loss of patient confidence 51 Would be less upset 96 if told Believe patient less upset if told 89 Expect apology Would offer apology 85 82

Discussion—Implementing near-miss reporting systems • A near-miss report system can be fairly easily incorporated into busy ambulatory practices. • The information is helpful in helping practices indentify and remediate potentially costly errors

Discussion-The utility of larger near-miss error databases • Could be used to identify less common, but potentially serious errors. • Could be used to develop best-practices • Could help EMR and other software vendors to develop products less prone to error.

Discussion—Disclosure expectations and attitudes • It is possible to do a point-of-care survey of patient attitudes with minimal resources or disruption of care. • There appears to be a gap between patient expectations and clinician attitudes toward disclosure conversations.

Limitations—Near Miss Reporting • Only one year • Relatively small sample of practices-not randomized. • Observed how practices used information-little attempt to guide practices. • Unclear how project changed practice safety culture. • Estimates of seriousness subjective • Anonymous, self-reports preclude determining true frequency of errors-probably greatly under-reported

Limitations—Disclosure Surveys • Relatively small numbers patients, clinicians • Single region, single practice (two locations), Caucasion.

Next Steps • Wider dissemination, larger data base • Focus on highest risk areas—Reporting results, dispensing/ordering meds, and EMR erros. • Survey larger more diverse population of patients and clinicians about expectations and attitudes for disclosure. • Test whether intervention can increase frequency and improve quality of these discussions.

Additional Information • The full AHRQ report posted on our Website: – http: //www. mahec. net/resident/fhch. aspx • Or contact us at: – Steve. Crane@pardeehospital. org – Natascha. lautenschlaeger@pardeehospital. org

- Slides: 24