Agglomeration economies Wage differences across cities F Candau

- Slides: 30

Agglomeration economies Wage differences across cities F. Candau

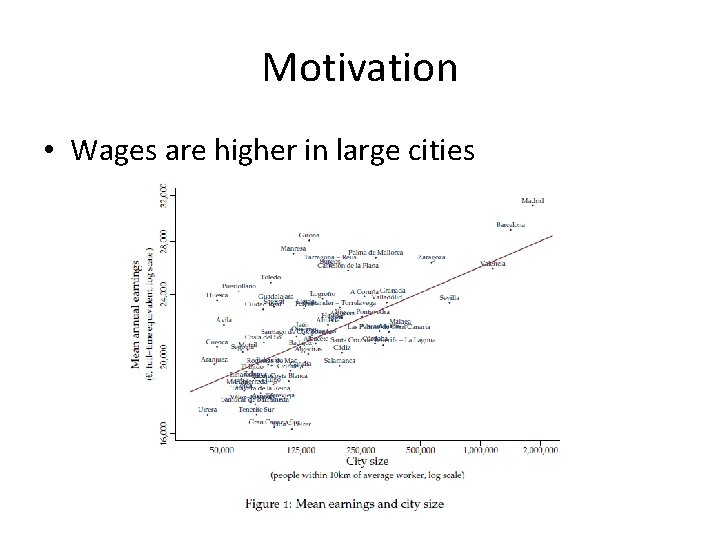

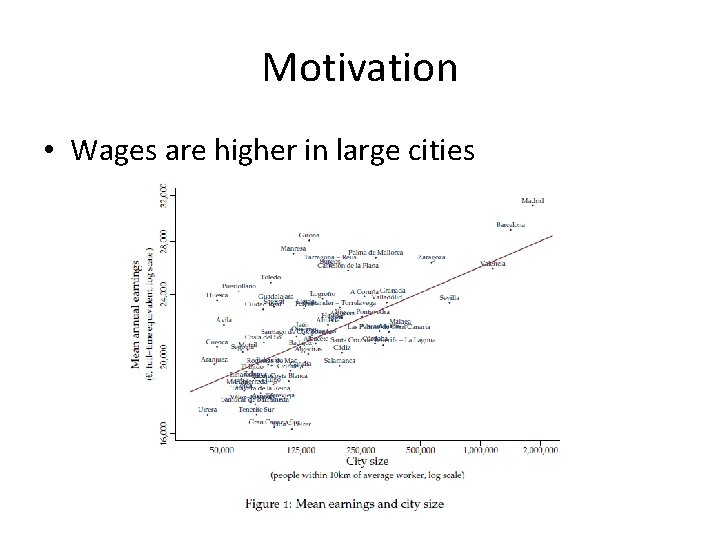

Motivation • Wages are higher in large cities

Wage differences across cities • There is notable geographic differences in earnings even for observationally equivalent workers. • For instance, a worker in Barcelona earns 39% more than a worker with the same observable characteristics in Lugo.

Question • Main question: How does city size improve productivities (and how much)? • Or…maybe it is just an artefact: • Higher wages compensate for higher costs (housing prices etc)… • It is not size by itself, but specialization. Small cities are specialized in declining sectors?

Wage differences across cities • 4 different sources of agglomeration economies: 1) Sharing inputs or facilities 2) Matching between workers and firms. 3) Learning: a key advantage of cities is that they facilitate experimentation, innovation and learning. 4) Sorting: workers who are inherently more productive may choose to locate in bigger cities.

Sharing • To share input and in particular for workers to share some kind of physical capital, such as specific equipments, machine and/or public goods (e. g. infrastructures), that are indivisible because requiring a minimum efficient scale is one significant historical source of agglomeration economies. • Large indivisibility generates increasing returns because extra unit of the goods is provided at a lower average cost.

Sharing • Firms also « share » consummers • Large market = Pecuniary externalities • Pecuniary externalities are all externalities channeled through the market, i. e. that affect prices and wages. • Virtuous circle (Krugman, 1991): the increase in wages attract new workers, which increases the size of the market, which allows the creation of new firms, and so on.

Sharing • Same mechanism along the supply chain. Firms producing intermediate goods are attracted to cities where producers of final goods are numerous since the agglomeration of final demand represent significant sales. This agglomeration allows suppliers of intermediate goods to lower prices which is directly beneficial to producers of final goods (Krugman and Venables, 1995)

Learning • Technological externalities • “Ideas are in the air”, Marshall (1890) • Innovations are sometimes not codified and knowledge can be tacit.

Learning • Two types of externalities are particularly significant in the process of knowledge creation and diffusion: – localization externalities (Marshall, 1890) , which operate mainly within a specific industry and – urbanization externalities (while Jacob, 1969)) which work across sectors.

Learning • Jacob (1969) considers diversity as a significant determinant for fruitful innovations, because “the greater the sheer number of and variety of division of labour, the greater the economy’s inherent capacity for adding still more kinds of goods and services” (Jacobs, 1969, p. 59).

Learning • Intra-industry and inter-industry externalities are present for high-tech companies while only the Marshall externalities are observed for more mature industries (Henderson et al. , 1995). • Innovative firms grow in location where diversity is high, while the oldest firms (in term of technology) tend to relocate their activities in smaller cities that are more specialized (Duranton and Puga, 2001).

Learning • Trade by expanding market allows efficiency gains by a better specialization of labor. • No specialization with small markets: • "In the lone houses and very small villages which are scattered about in so desert a country as the Highlands of Scotland, every farmer must be a butcher, baker, and brewer for his own family. " Smith (1776, p. 122)

Matching • Large market = new job: a worker with a specialized skill will find more easily a job in a big city than in a small one. • "There are some sorts of industry, even of the lowest kind, which can be carried on nowhere but in a great town. A porter, for example, can find employment and subsistence in no other place. " A Smith

Matching • Large market = new skills • The larger the local market, the more likely an employee can find a worker with the adequate skill. The reverse is also true, Thick labour markets lead to better matching between employers and employees (Helsley and Strange, 1990). • The attractiveness of big cities is thus selfsustaining.

Sorting • Sorting: big cities attracts the best students, workers, firms for various reasons linked to infrastructures (grandes écoles in France, airport etc) and urban amenities.

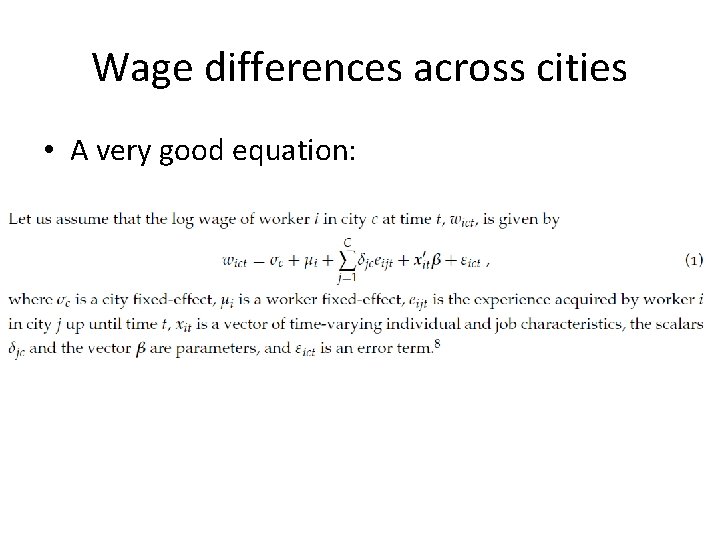

Wage differences across cities • A very good equation:

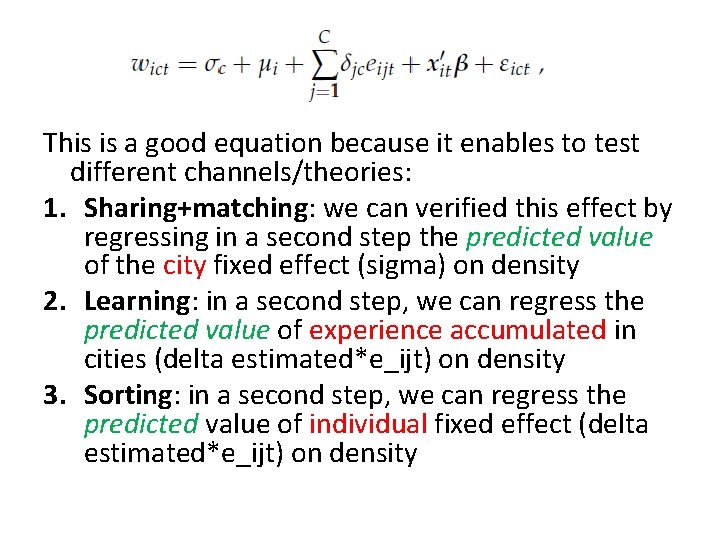

This is a good equation because it enables to test different channels/theories: 1. Sharing+matching: we can verified this effect by regressing in a second step the predicted value of the city fixed effect (sigma) on density 2. Learning: in a second step, we can regress the predicted value of experience accumulated in cities (delta estimated*e_ijt) on density 3. Sorting: in a second step, we can regress the predicted value of individual fixed effect (delta estimated*e_ijt) on density

It’s the density, stupid! • Why density? • Because it fits well different theories: easier to match, to share, to learn in environment with high density. Maybe workers sort into large cities because density there provides more cultural amenities. • However, there is not a theory on « density » , which is just a proxy, it might be interesting to test/think to other variables in this equation

So good to be naïve • Before to analyze the nice previous equation, let’s imagine you are naïve and you simply run a pooled ols:

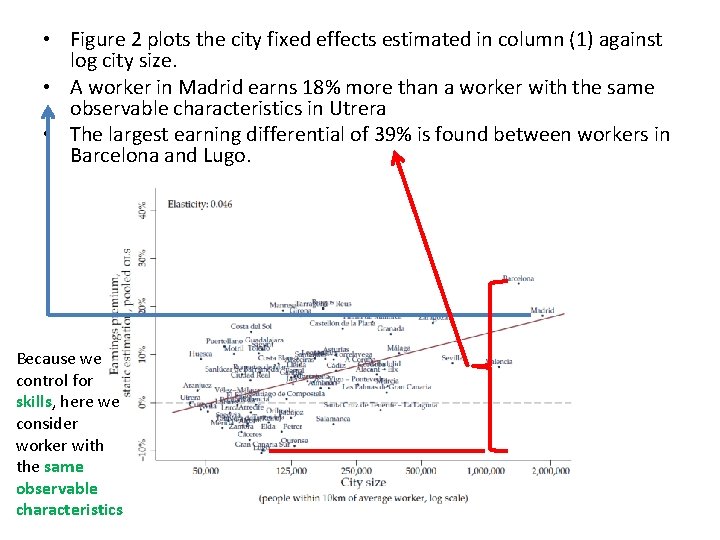

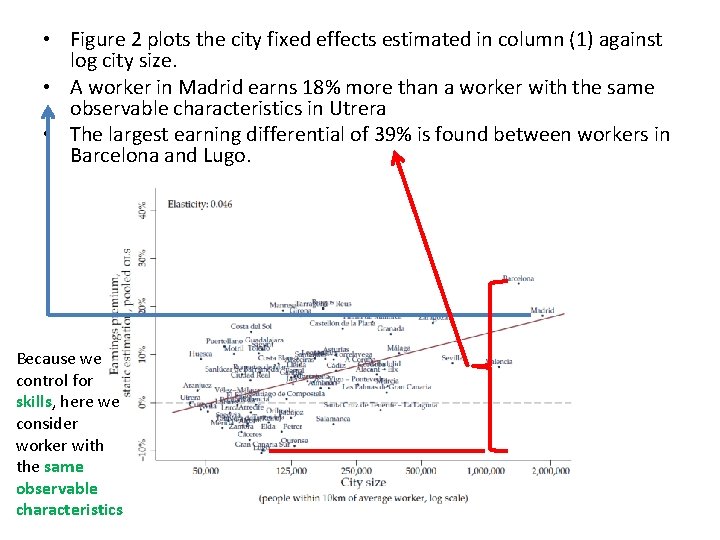

• Figure 2 plots the city fixed effects estimated in column (1) against log city size. • A worker in Madrid earns 18% more than a worker with the same observable characteristics in Utrera • The largest earning differential of 39% is found between workers in Barcelona and Lugo. Because we control for skills, here we consider worker with the same observable characteristics

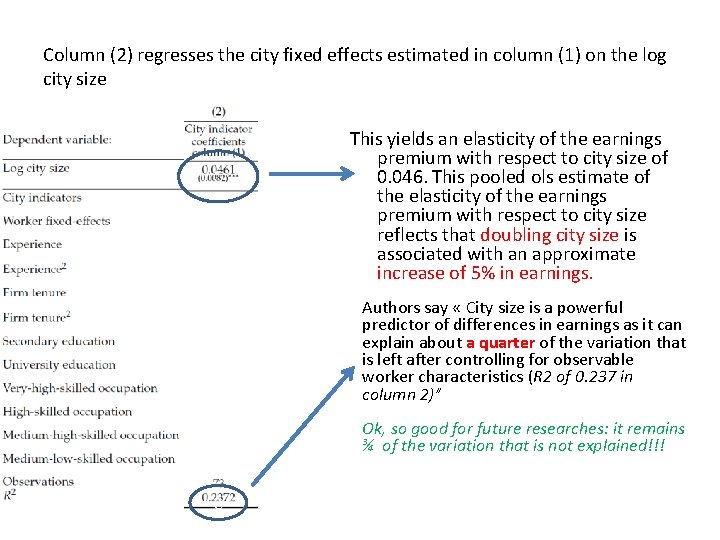

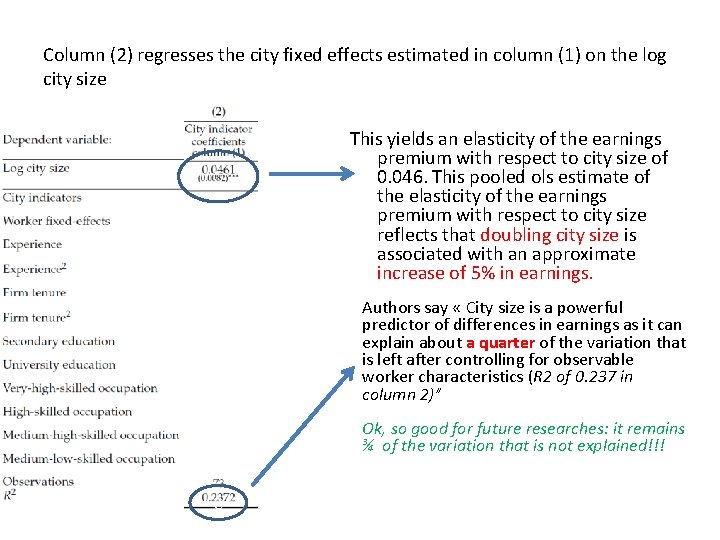

Column (2) regresses the city fixed effects estimated in column (1) on the log city size C This yields an elasticity of the earnings premium with respect to city size of 0. 046. This pooled ols estimate of the elasticity of the earnings premium with respect to city size reflects that doubling city size is associated with an approximate increase of 5% in earnings. Authors say « City size is a powerful predictor of differences in earnings as it can explain about a quarter of the variation that is left after controlling for observable worker characteristics (R 2 of 0. 237 in column 2)” Ok, so good for future researches: it remains ¾ of the variation that is not explained!!! C

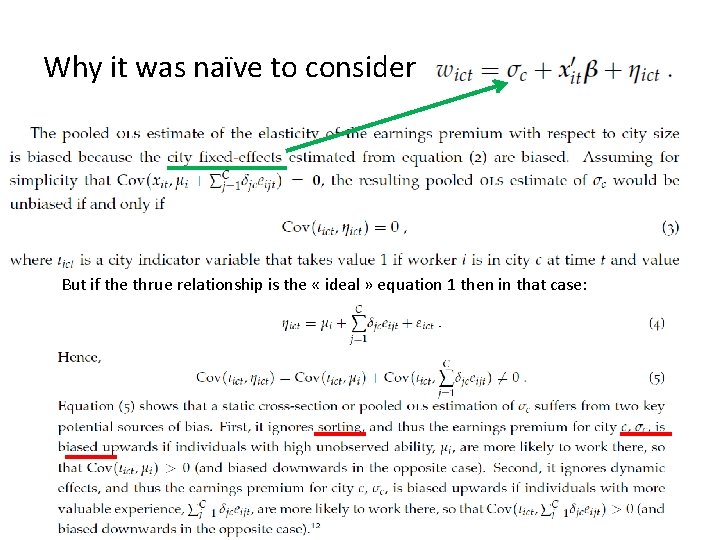

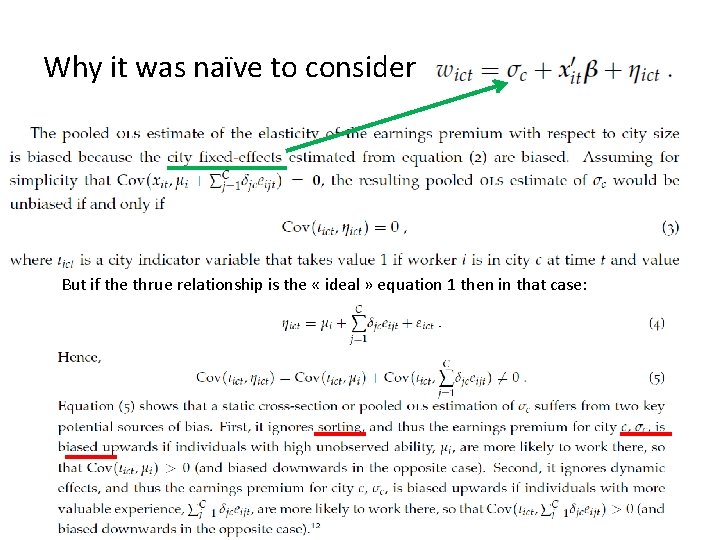

Why it was naïve to consider But if the thrue relationship is the « ideal » equation 1 then in that case:

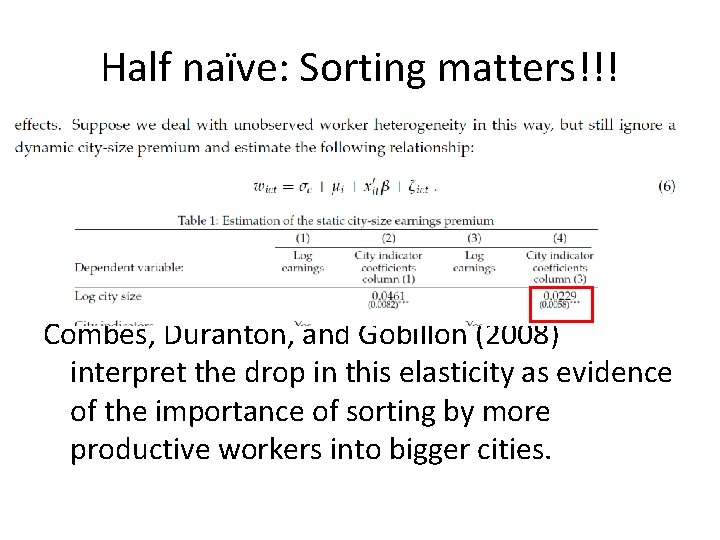

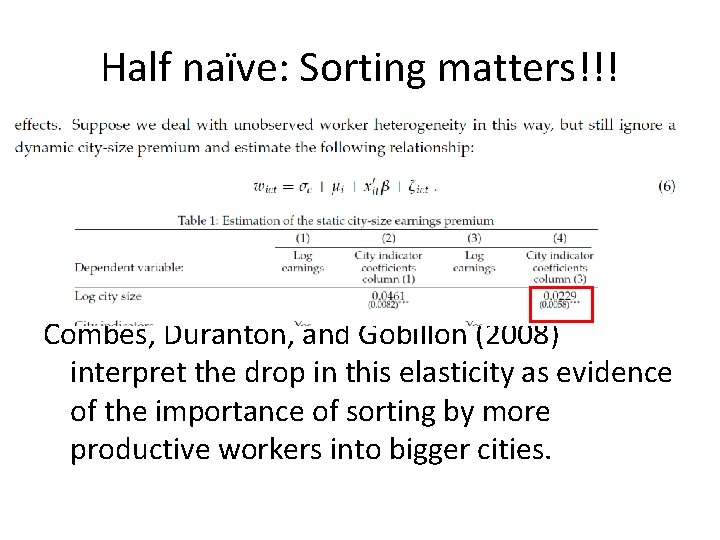

Half naïve: Sorting matters!!! Combes, Duranton, and Gobillon (2008) interpret the drop in this elasticity as evidence of the importance of sorting by more productive workers into bigger cities.

• However, this lower static could reflect either the importance of sorting by workers across cities, or the importance of learning by working in bigger cities, or a combination of both.

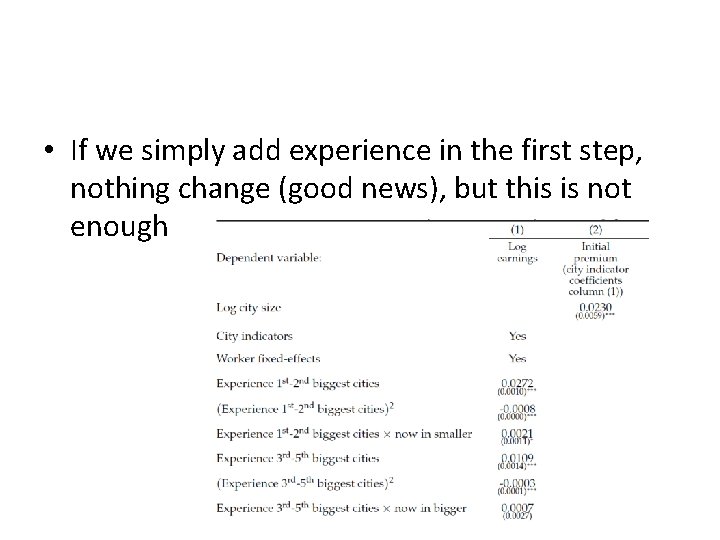

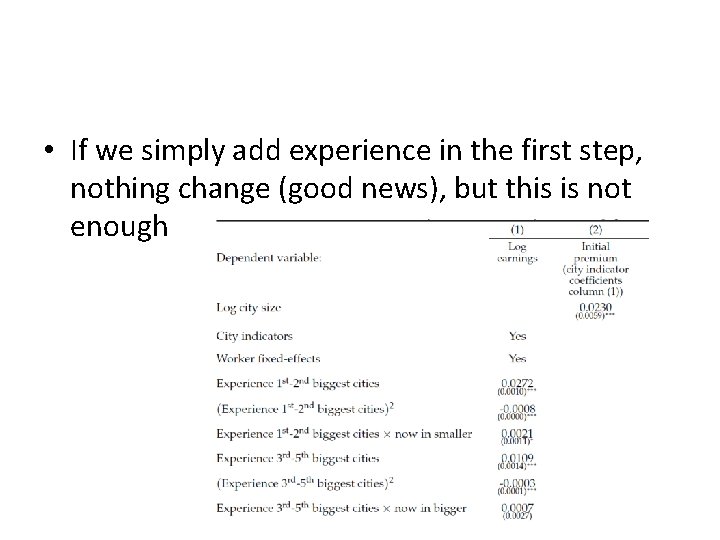

• If we simply add experience in the first step, nothing change (good news), but this is not enough

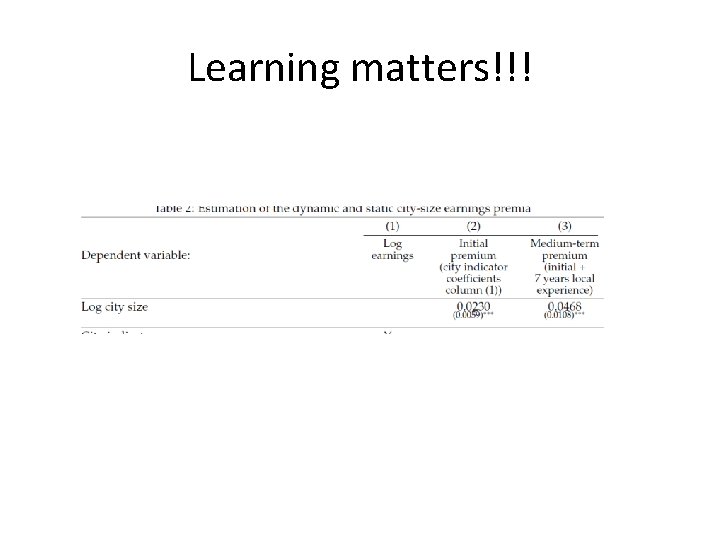

• We have to add to each city fixed effect the estimated value of experience accumulated in that same city • Et là surprise…

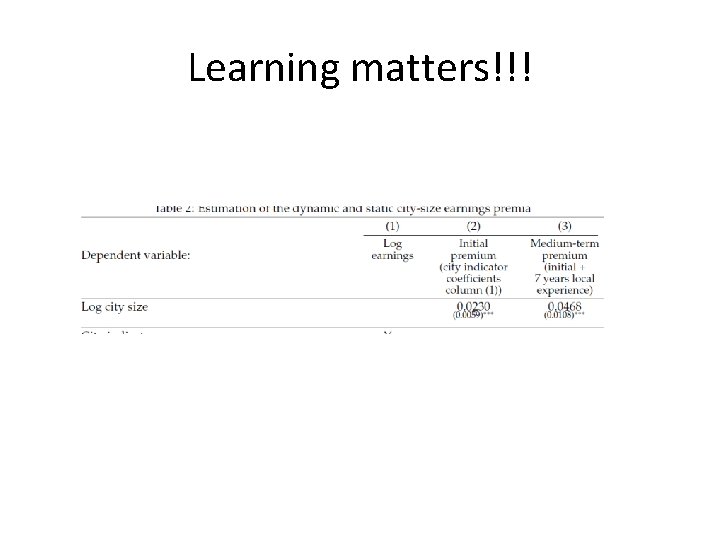

Learning matters!!!

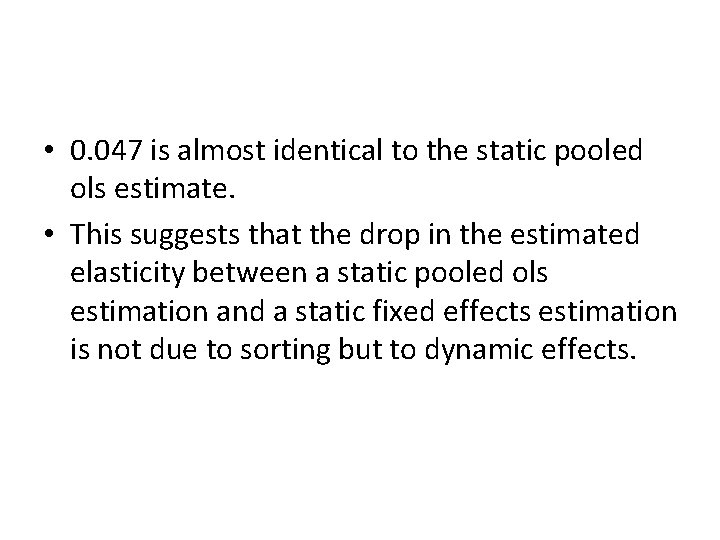

• 0. 047 is almost identical to the static pooled ols estimate. • This suggests that the drop in the estimated elasticity between a static pooled ols estimation and a static fixed effects estimation is not due to sorting but to dynamic effects.