Advanced Graphics Lecture One 3 D Graphics and

- Slides: 30

Advanced Graphics – Lecture One 3 D Graphics and Computational Geometry Alex Benton, University of Cambridge – A. Benton@damtp. cam. ac. uk Supported in part by Google UK, Ltd

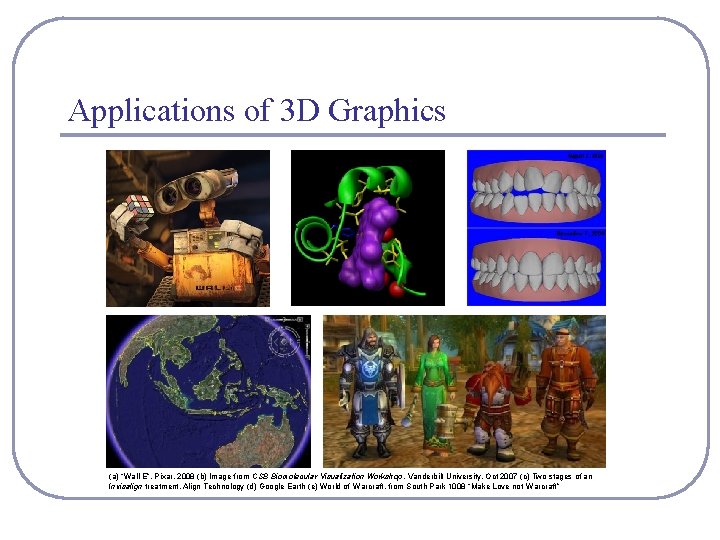

Applications of 3 D Graphics (a) “Wall-E”, Pixar, 2008 (b) Image from CSB Biomolecular Visualization Workshop, Vanderbilt University, Oct 2007 (c) Two stages of an Invisalign treatment, Align Technology (d) Google Earth (e) World of Warcraft, from South Park 1008 “Make Love not Warcraft”

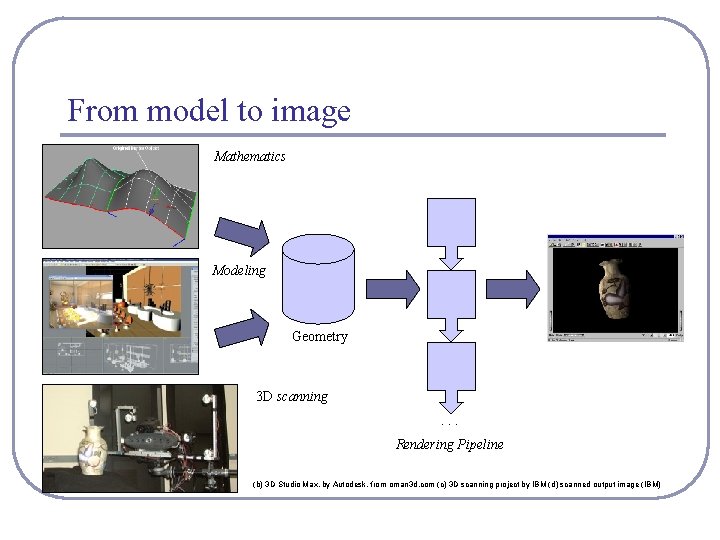

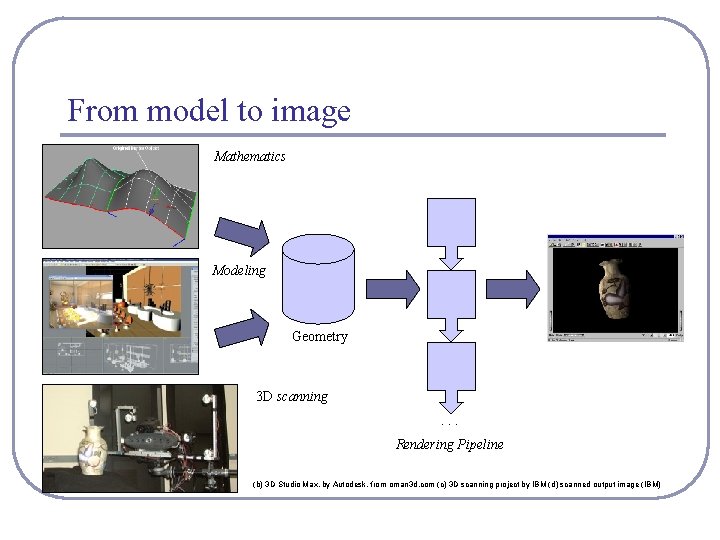

From model to image Mathematics Modeling Geometry 3 D scanning. . . Rendering Pipeline (b) 3 D Studio Max, by Autodesk, from oman 3 d. com (c) 3 D scanning project by IBM (d) scanned output image (IBM)

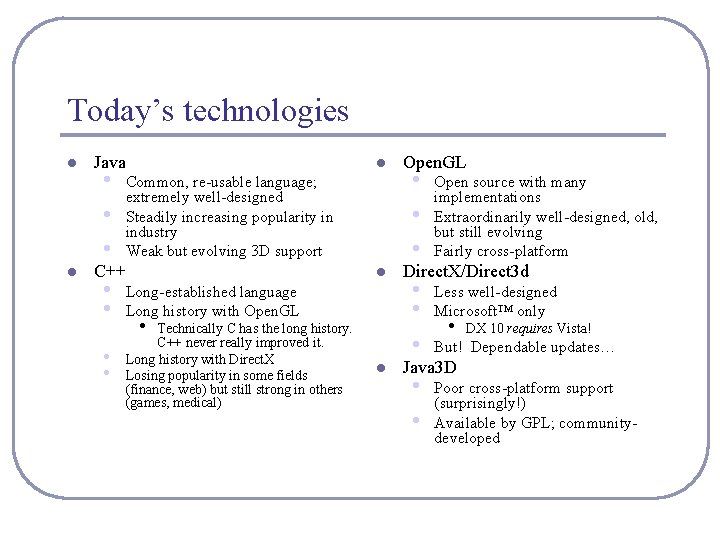

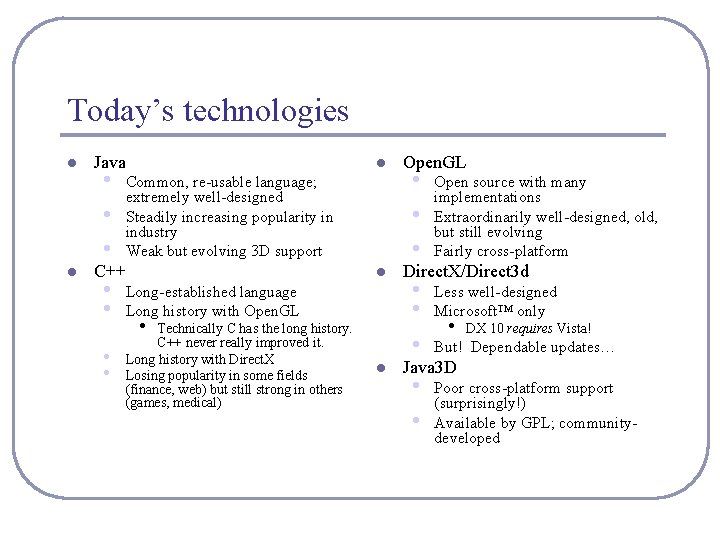

Today’s technologies l l Java • • • l Common, re-usable language; extremely well-designed Steadily increasing popularity in industry Weak but evolving 3 D support C++ • • l Long-established language Long history with Open. GL • Technically C has the long history. C++ never really improved it. Long history with Direct. X Losing popularity in some fields (finance, web) but still strong in others (games, medical) l Open. GL • • • Open source with many implementations Extraordinarily well-designed, old, but still evolving Fairly cross-platform • • • Less well-designed Microsoft™ only • • Poor cross-platform support (surprisingly!) Available by GPL; communitydeveloped Direct. X/Direct 3 d • DX 10 requires Vista! But! Dependable updates… Java 3 D

Open. GL l Open. GL is… l Open. GL is a state-based renderer • hardware-independent • operating system independent • vendor neutral • set up the state, then pass in data: data is modified • by existing state very different from the OOP model, where data would carry its own state

Open. GL l Open. GL is platform-independent, but implementations are platform-specific and often rely on the presence of native libraries • • l Great support for Windows, Mac, linux, etc Support for mobile devices with Open. GL-ES • Including Google Android! Accelerates common 3 D graphics operations • • Clipping (for primitives) Hidden-surface removal (Z-buffering) Texturing, alpha blending (transparency) NURBS and other advanced primitives (GLUT)

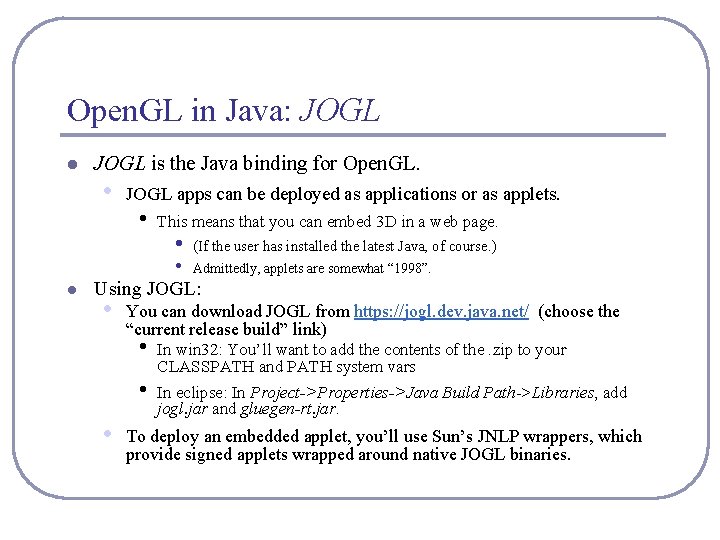

Open. GL in Java: JOGL l JOGL is the Java binding for Open. GL. • JOGL apps can be deployed as applications or as applets. • This means that you can embed 3 D in a web page. • • l (If the user has installed the latest Java, of course. ) Admittedly, applets are somewhat “ 1998”. Using JOGL: • You can download JOGL from https: //jogl. dev. java. net/ (choose the “current release build” link) • • • In win 32: You’ll want to add the contents of the. zip to your CLASSPATH and PATH system vars In eclipse: In Project->Properties->Java Build Path->Libraries, add jogl. jar and gluegen-rt. jar. To deploy an embedded applet, you’ll use Sun’s JNLP wrappers, which provide signed applets wrapped around native JOGL binaries.

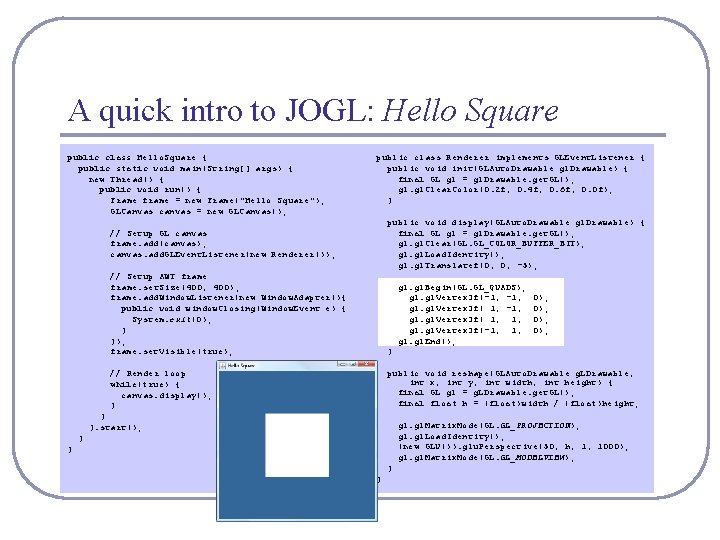

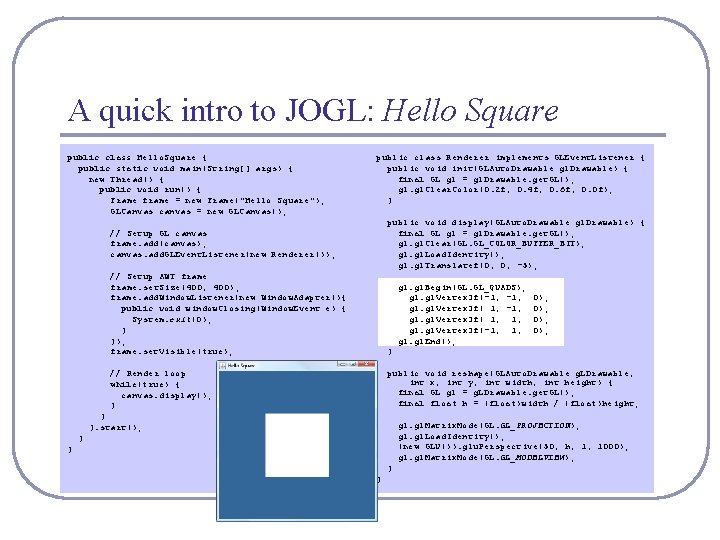

A quick intro to JOGL: Hello Square public class Hello. Square { public static void main(String[] args) { new Thread() { public void run() { Frame frame = new Frame("Hello Square"); GLCanvas canvas = new GLCanvas(); public class Renderer implements GLEvent. Listener { public void init(GLAuto. Drawable gl. Drawable) { final GL gl = gl. Drawable. get. GL(); gl. Clear. Color(0. 2 f, 0. 4 f, 0. 6 f, 0. 0 f); } public void display(GLAuto. Drawable gl. Drawable) { final GL gl = gl. Drawable. get. GL(); gl. Clear(GL. GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT); gl. Load. Identity(); gl. Translatef(0, 0, -5); // Setup GL canvas frame. add(canvas); canvas. add. GLEvent. Listener(new Renderer()); // Setup AWT frame. set. Size(400, 400); frame. add. Window. Listener(new Window. Adapter(){ public void window. Closing(Window. Event e) { System. exit(0); } }); frame. set. Visible(true); } // Render loop while(true) { canvas. display(); } public void reshape(GLAuto. Drawable g. LDrawable, int x, int y, int width, int height) { final GL gl = g. LDrawable. get. GL(); final float h = (float)width / (float)height; gl. Begin(GL. GL_QUADS); gl. Vertex 3 f(-1, gl. Vertex 3 f( 1, 1, gl. Vertex 3 f(-1, 1, gl. End(); } }. start(); 0); 0); gl. Matrix. Mode(GL. GL_PROJECTION); gl. Load. Identity(); (new GLU()). glu. Perspective(50, h, 1, 1000); gl. Matrix. Mode(GL. GL_MODELVIEW); } }

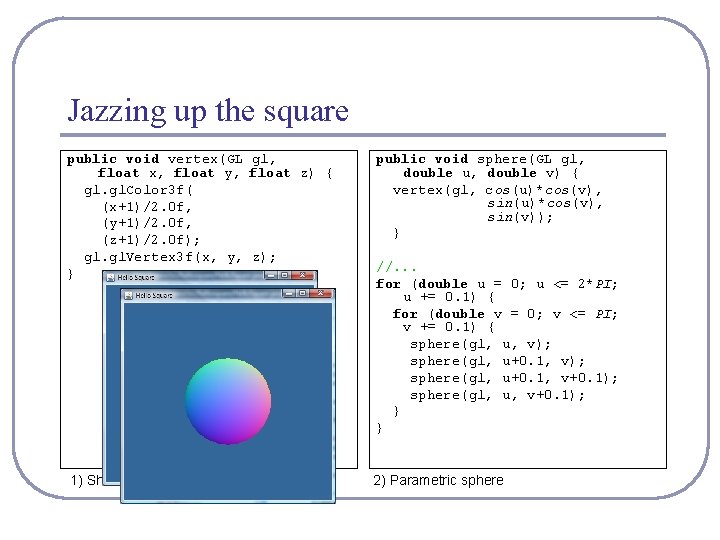

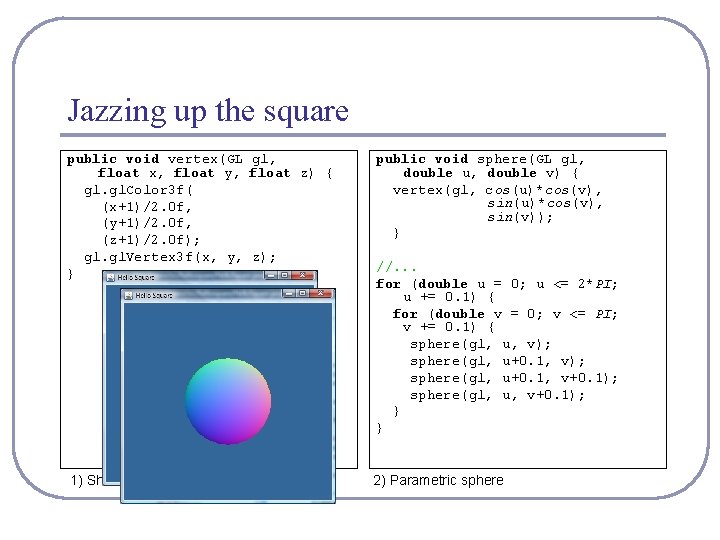

Jazzing up the square public void vertex(GL gl, float x, float y, float z) { gl. Color 3 f( (x+1)/2. 0 f, (y+1)/2. 0 f, (z+1)/2. 0 f); gl. Vertex 3 f(x, y, z); } public void sphere(GL gl, double u, double v) { vertex(gl, cos(u)*cos(v), sin(v)); } 1) Shaded square 2) Parametric sphere //. . . for (double u = 0; u <= 2*PI; u += 0. 1) { for (double v = 0; v <= PI; v += 0. 1) { sphere(gl, u, v); sphere(gl, u+0. 1, v+0. 1); sphere(gl, u, v+0. 1); } }

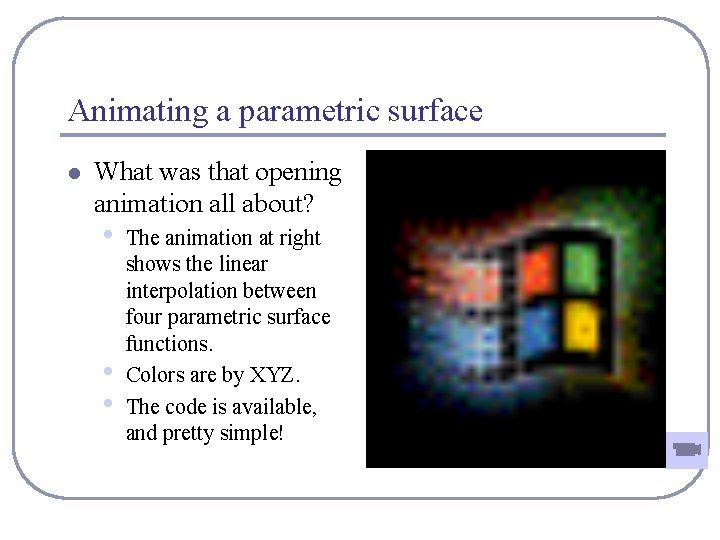

Animating a parametric surface l What was that opening animation all about? • • • The animation at right shows the linear interpolation between four parametric surface functions. Colors are by XYZ. The code is available, and pretty simple!

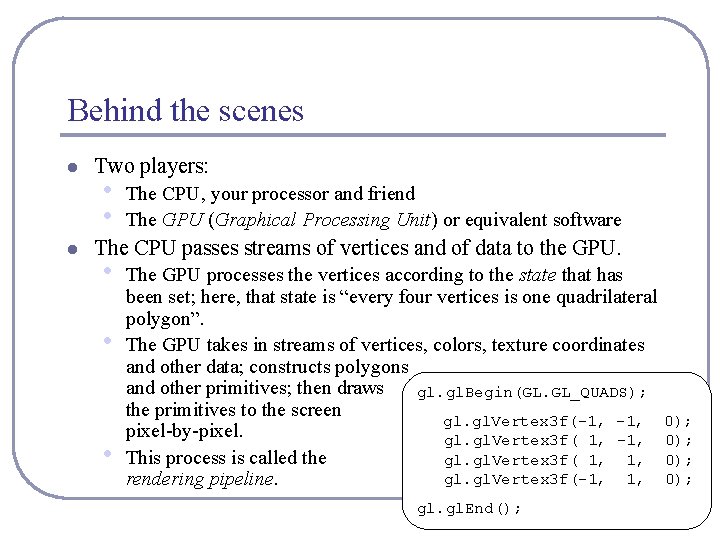

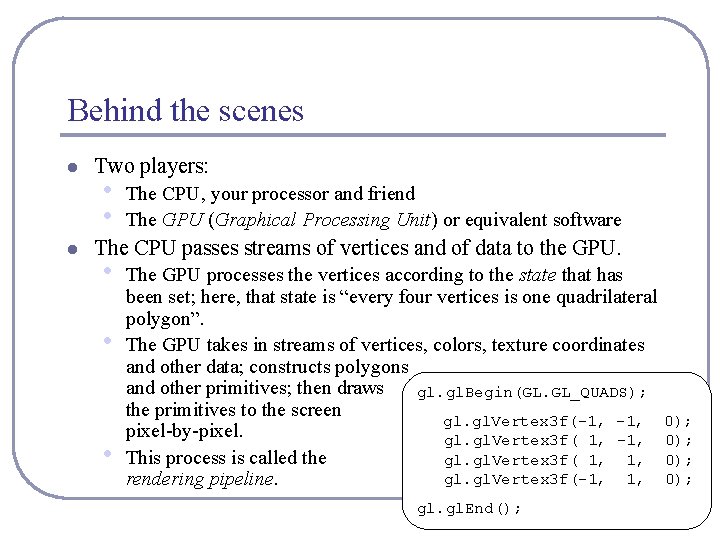

Behind the scenes l l Two players: • • The CPU, your processor and friend The GPU (Graphical Processing Unit) or equivalent software The CPU passes streams of vertices and of data to the GPU. • • • The GPU processes the vertices according to the state that has been set; here, that state is “every four vertices is one quadrilateral polygon”. The GPU takes in streams of vertices, colors, texture coordinates and other data; constructs polygons and other primitives; then draws gl. Begin(GL. GL_QUADS); the primitives to the screen gl. Vertex 3 f(-1, pixel-by-pixel. gl. Vertex 3 f( 1, -1, This process is called the gl. Vertex 3 f( 1, 1, gl. Vertex 3 f(-1, 1, rendering pipeline. gl. End(); 0); 0);

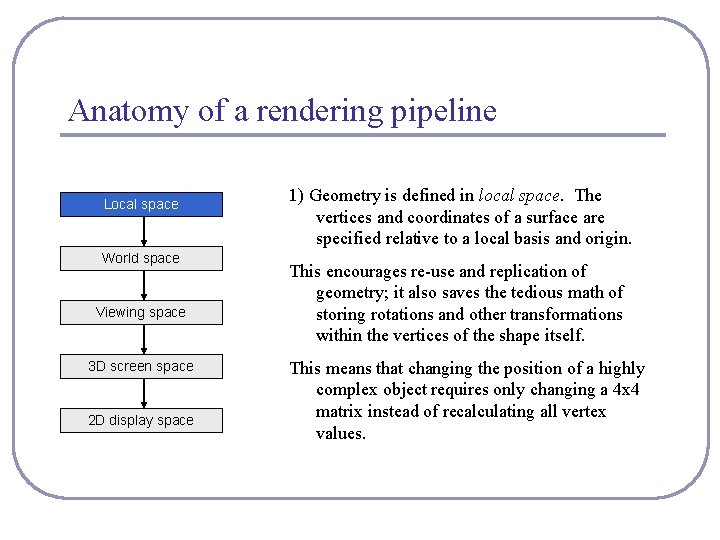

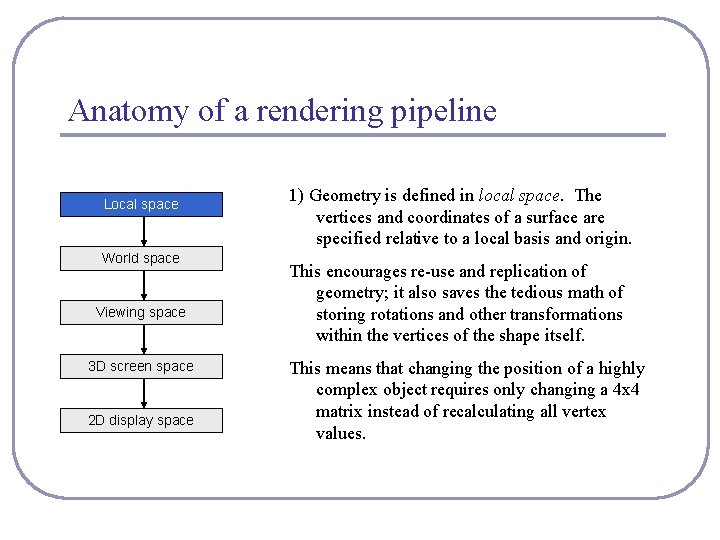

Anatomy of a rendering pipeline Local space World space Viewing space 3 D screen space 2 D display space 1) Geometry is defined in local space. The vertices and coordinates of a surface are specified relative to a local basis and origin. This encourages re-use and replication of geometry; it also saves the tedious math of storing rotations and other transformations within the vertices of the shape itself. This means that changing the position of a highly complex object requires only changing a 4 x 4 matrix instead of recalculating all vertex values.

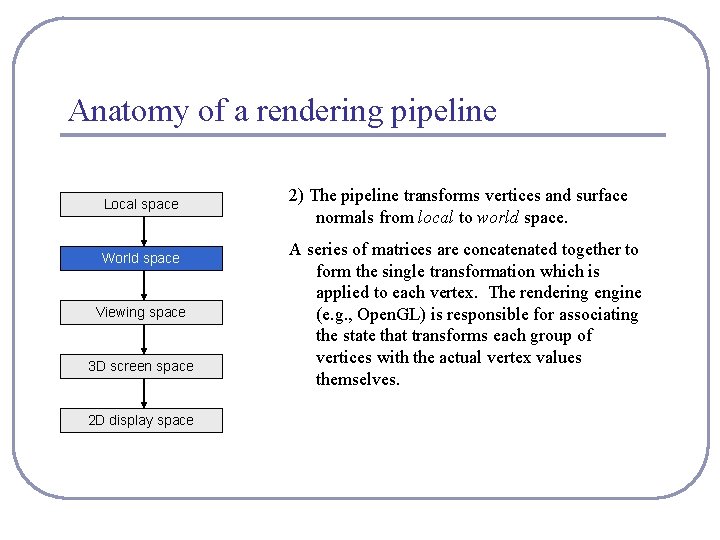

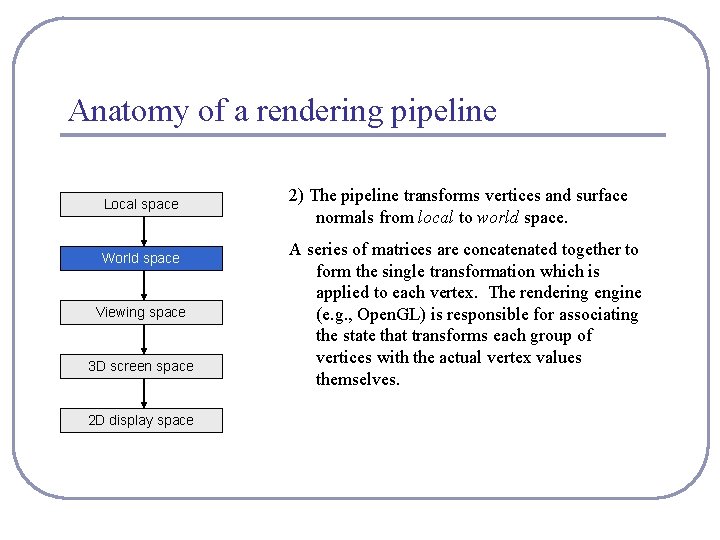

Anatomy of a rendering pipeline Local space World space Viewing space 3 D screen space 2 D display space 2) The pipeline transforms vertices and surface normals from local to world space. A series of matrices are concatenated together to form the single transformation which is applied to each vertex. The rendering engine (e. g. , Open. GL) is responsible for associating the state that transforms each group of vertices with the actual vertex values themselves.

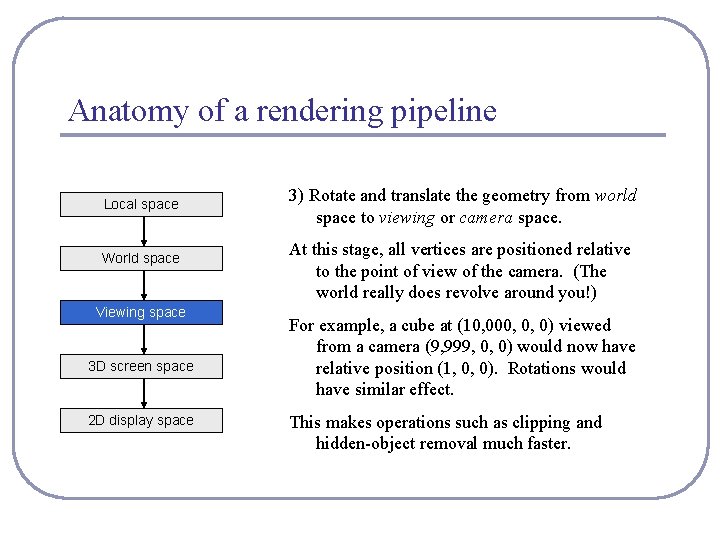

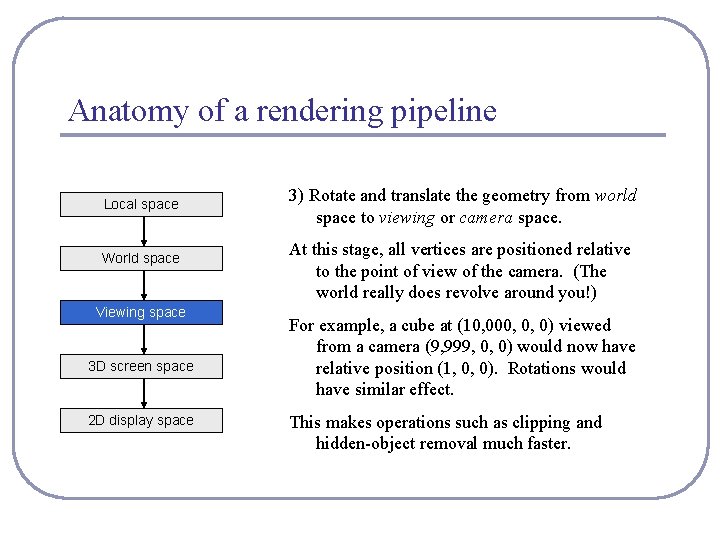

Anatomy of a rendering pipeline Local space World space Viewing space 3 D screen space 2 D display space 3) Rotate and translate the geometry from world space to viewing or camera space. At this stage, all vertices are positioned relative to the point of view of the camera. (The world really does revolve around you!) For example, a cube at (10, 000, 0, 0) viewed from a camera (9, 999, 0, 0) would now have relative position (1, 0, 0). Rotations would have similar effect. This makes operations such as clipping and hidden-object removal much faster.

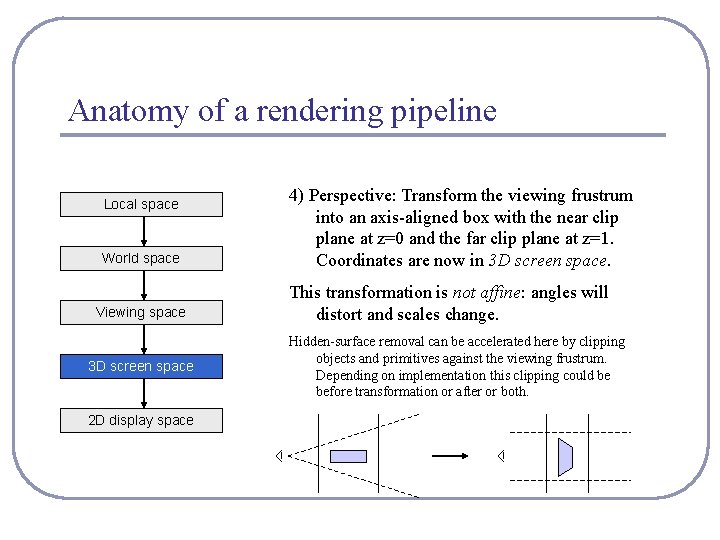

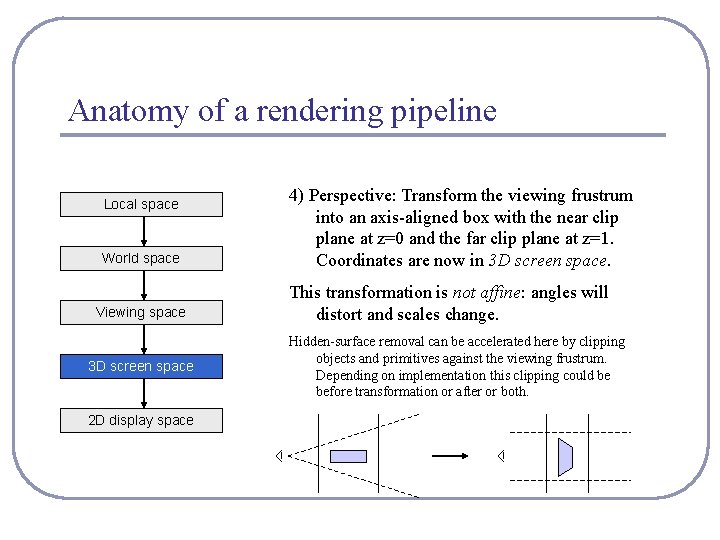

Anatomy of a rendering pipeline Local space World space Viewing space 3 D screen space 2 D display space 4) Perspective: Transform the viewing frustrum into an axis-aligned box with the near clip plane at z=0 and the far clip plane at z=1. Coordinates are now in 3 D screen space. This transformation is not affine: angles will distort and scales change. Hidden-surface removal can be accelerated here by clipping objects and primitives against the viewing frustrum. Depending on implementation this clipping could be before transformation or after or both.

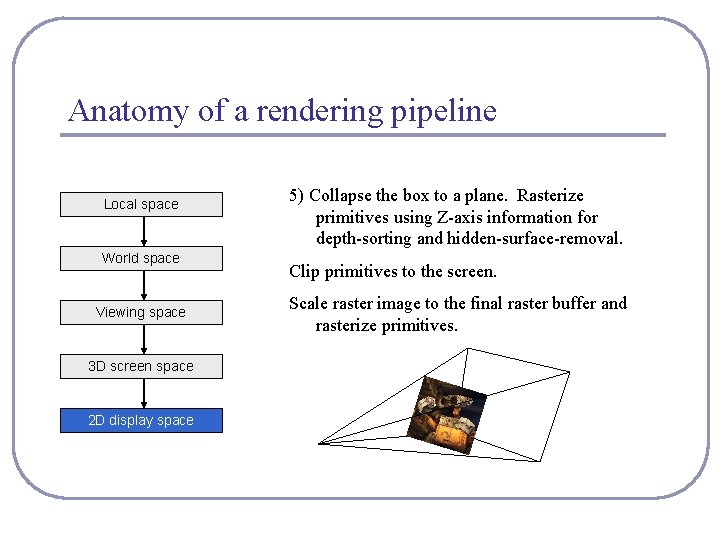

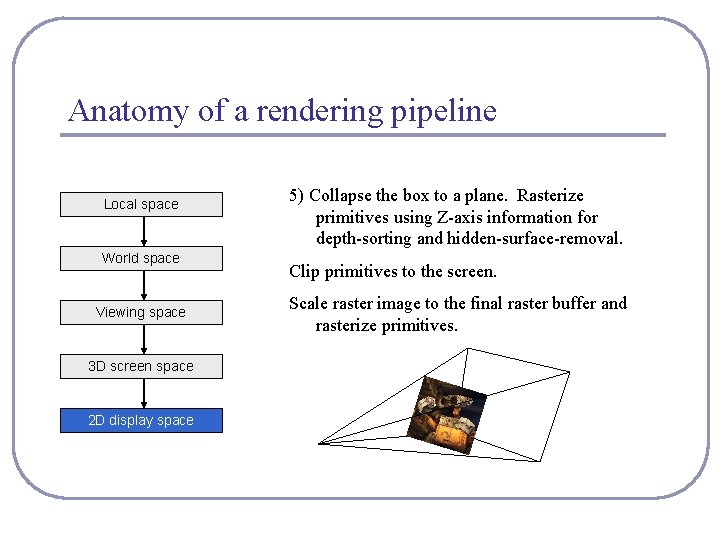

Anatomy of a rendering pipeline Local space World space Viewing space 3 D screen space 2 D display space 5) Collapse the box to a plane. Rasterize primitives using Z-axis information for depth-sorting and hidden-surface-removal. Clip primitives to the screen. Scale raster image to the final raster buffer and rasterize primitives.

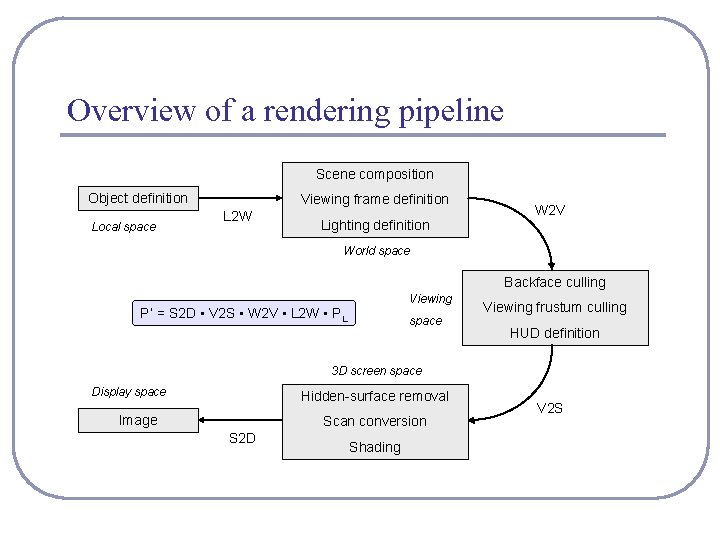

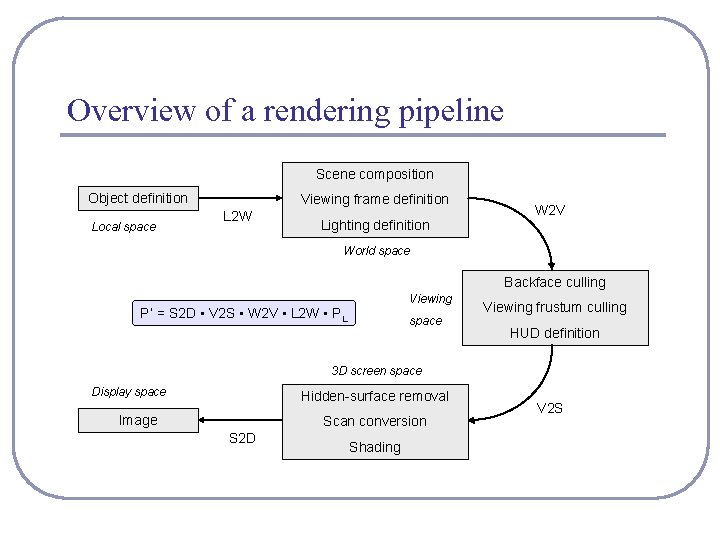

Overview of a rendering pipeline Scene composition Object definition Local space Viewing frame definition L 2 W Lighting definition W 2 V World space Backface culling Viewing P’ = S 2 D • V 2 S • W 2 V • L 2 W • PL space Viewing frustum culling HUD definition 3 D screen space Display space Hidden-surface removal Image Scan conversion S 2 D Shading V 2 S

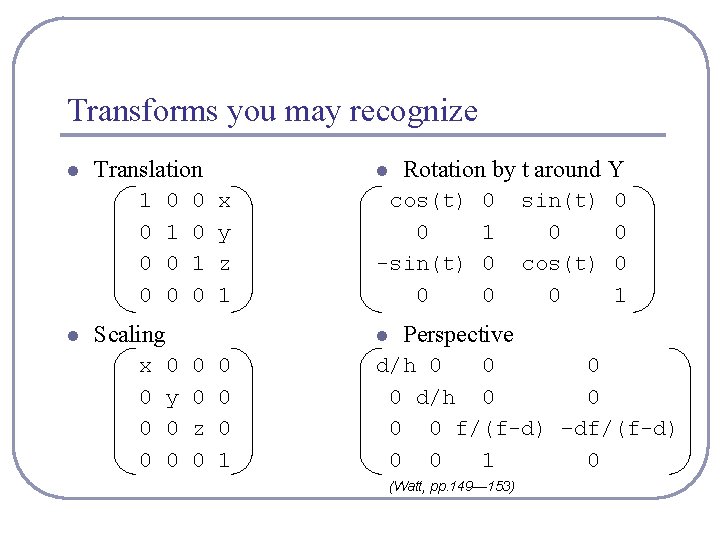

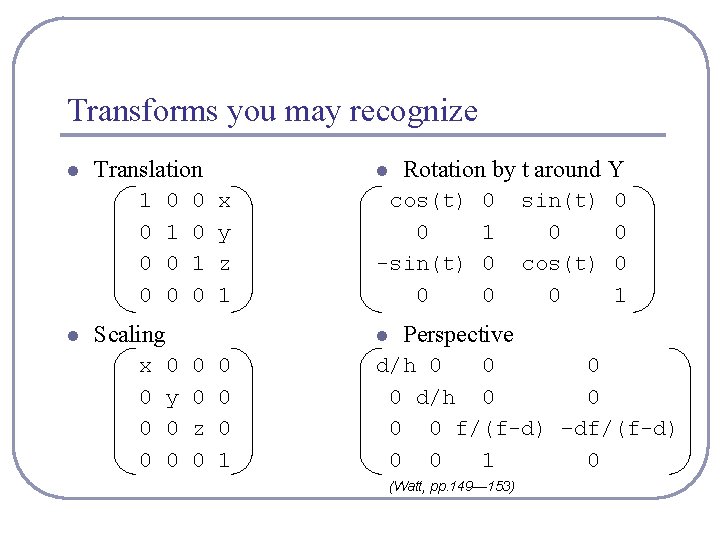

Transforms you may recognize l Translation 1 0 0 0 l 0 1 0 l x y z 1 Scaling x 0 0 y 0 0 cos(t) 0 -sin(t) 0 l 0 0 z 0 0 1 Rotation by t around Y 0 1 0 0 sin(t) 0 cos(t) 0 0 1 Perspective d/h 0 0 0 0 f/(f-d) –df/(f-d) 0 0 1 0 (Watt, pp. 149— 153)

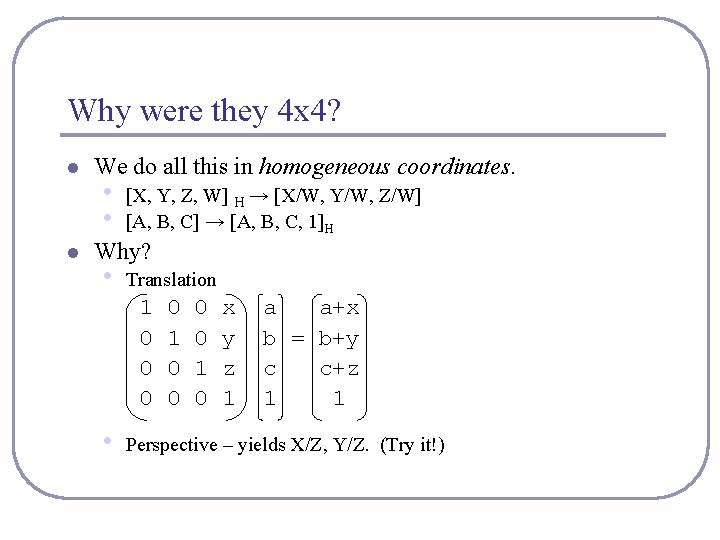

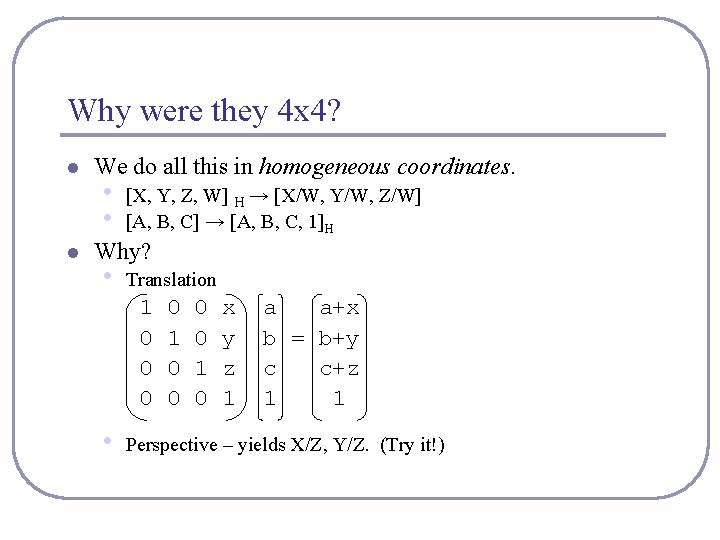

Why were they 4 x 4? l l We do all this in homogeneous coordinates. • • [X, Y, Z, W] H → [X/W, Y/W, Z/W] [A, B, C] → [A, B, C, 1]H Why? • Translation 1 0 0 0 • 0 1 0 x y z 1 a a+x b = b+y c c+z 1 1 Perspective – yields X/Z, Y/Z. (Try it!)

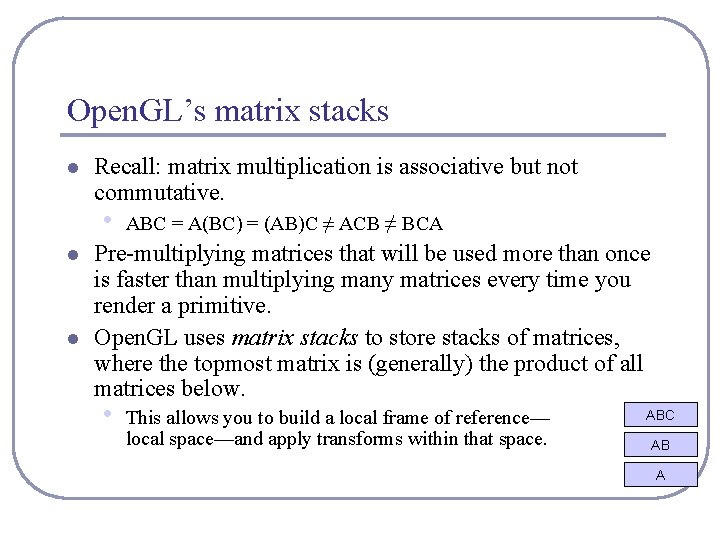

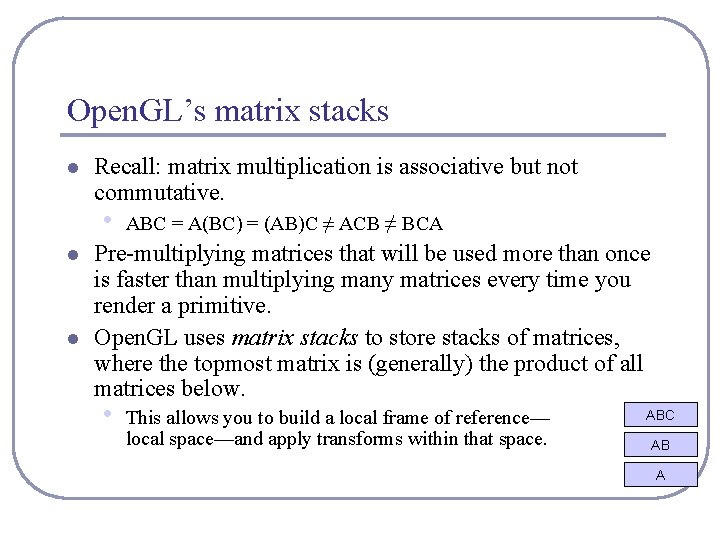

Open. GL’s matrix stacks l Recall: matrix multiplication is associative but not commutative. • l l ABC = A(BC) = (AB)C ≠ ACB ≠ BCA Pre-multiplying matrices that will be used more than once is faster than multiplying many matrices every time you render a primitive. Open. GL uses matrix stacks to store stacks of matrices, where the topmost matrix is (generally) the product of all matrices below. • This allows you to build a local frame of reference— local space—and apply transforms within that space. ABC AB A

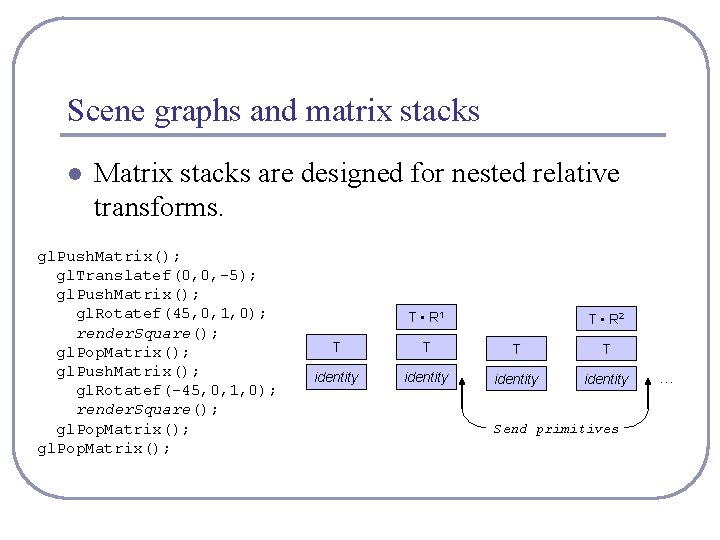

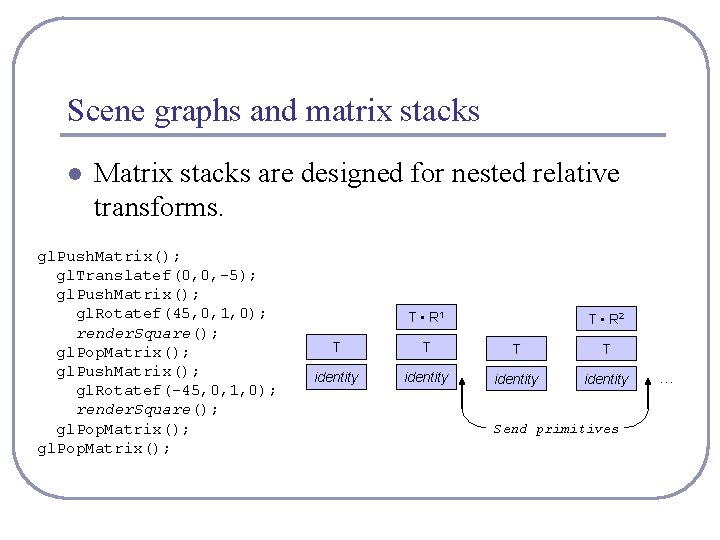

Scene graphs and matrix stacks l Matrix stacks are designed for nested relative transforms. gl. Push. Matrix(); gl. Translatef(0, 0, -5); gl. Push. Matrix(); gl. Rotatef(45, 0, 1, 0); render. Square(); gl. Pop. Matrix(); gl. Push. Matrix(); gl. Rotatef(-45, 0, 1, 0); render. Square(); gl. Pop. Matrix(); T • R 1 T • R 2 T T identity Send primitives …

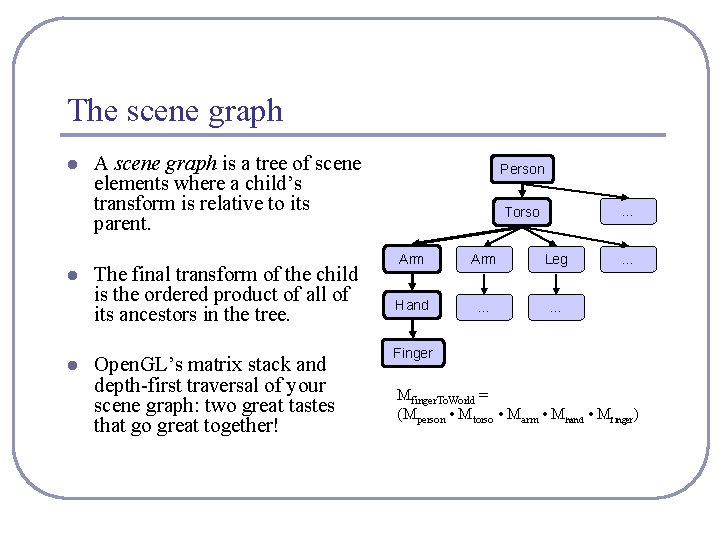

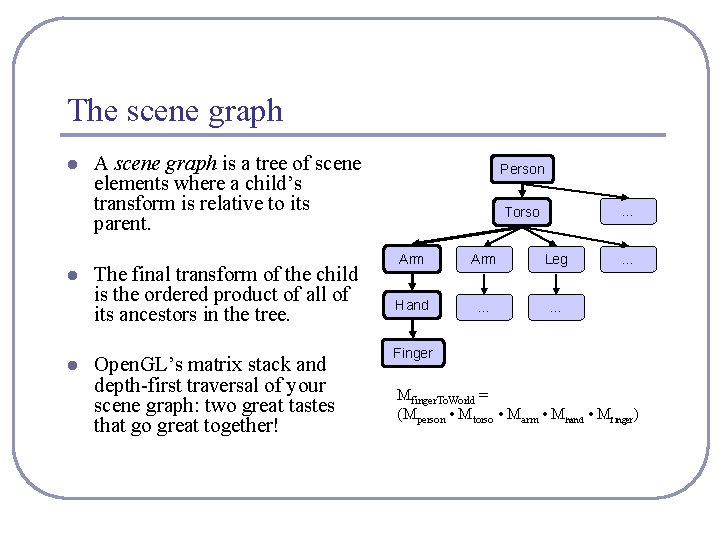

The scene graph l l l A scene graph is a tree of scene elements where a child’s transform is relative to its parent. The final transform of the child is the ordered product of all of its ancestors in the tree. Open. GL’s matrix stack and depth-first traversal of your scene graph: two great tastes that go great together! Person … Torso Arm Leg Hand … … … Finger Mfinger. To. World = (Mperson • Mtorso • Marm • Mhand • Mfinger)

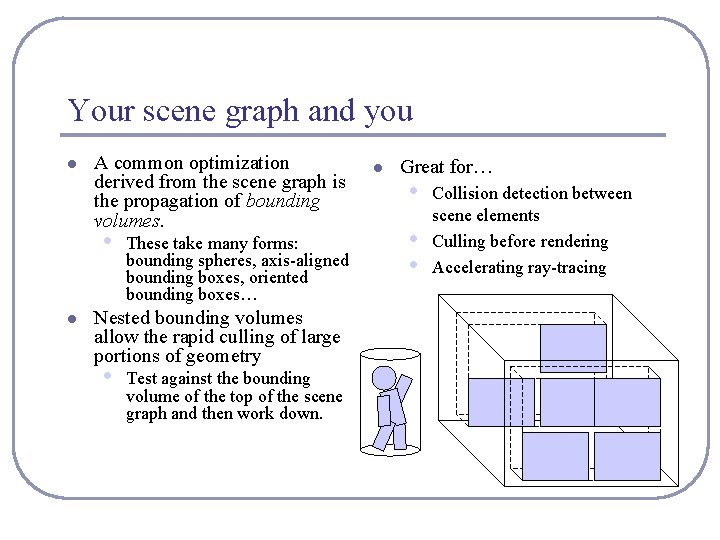

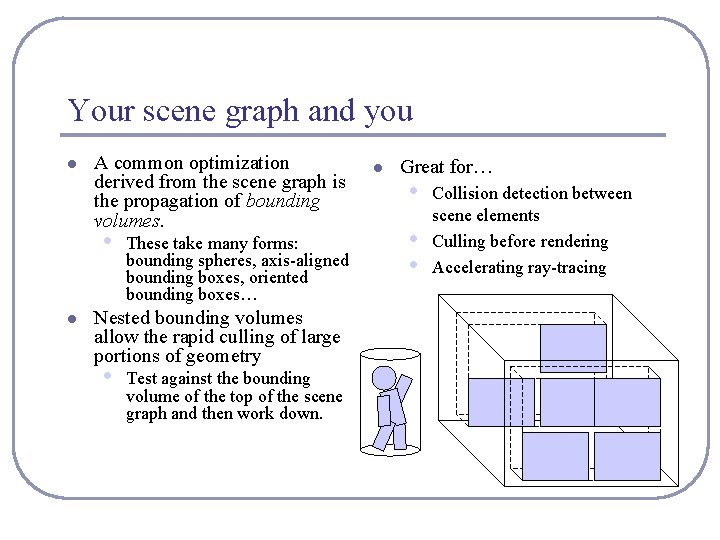

Your scene graph and you l A common optimization derived from the scene graph is the propagation of bounding volumes. • l These take many forms: bounding spheres, axis-aligned bounding boxes, oriented bounding boxes… Nested bounding volumes allow the rapid culling of large portions of geometry • Test against the bounding volume of the top of the scene graph and then work down. l Great for… • • • Collision detection between scene elements Culling before rendering Accelerating ray-tracing

Your scene graph and you l Many 2 D GUIs today favor an event model in which events ‘bubble up’ from child windows to parents. This is sometimes mirrored in a scene graph. • • l Ex: a child changes size, which changes the size of the parent’s bounding box Ex: the user drags a movable control in the scene, triggering an update event If you do choose this approach, consider using the model/ view/ controller design pattern. 3 D geometry objects are good for displaying data but they are not the proper place for control logic. • • For example, the class that stores the geometry of the rocket should not be the same class that stores the logic that moves the rocket. Always separate logic from representation.

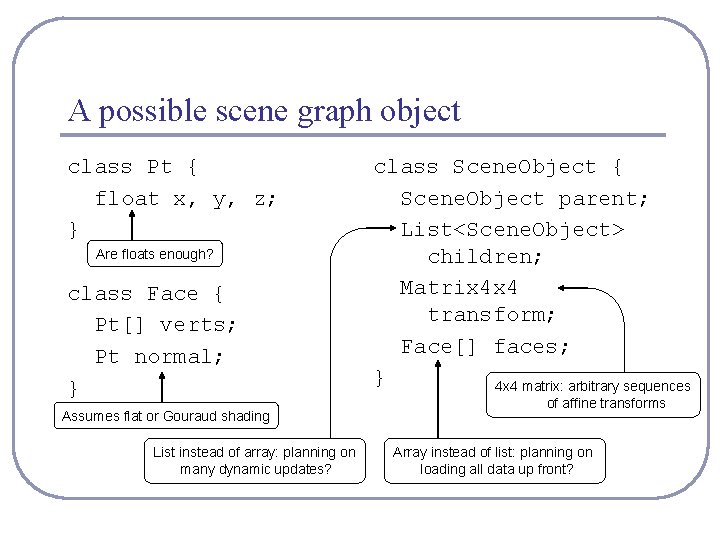

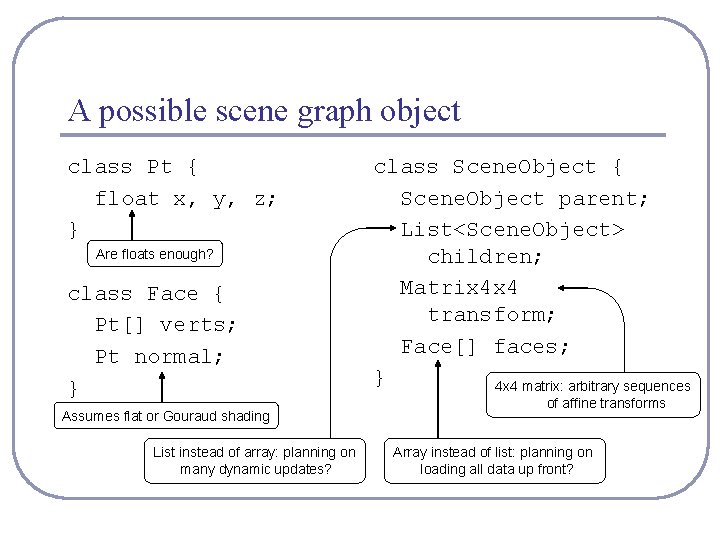

A possible scene graph object class Pt { float x, y, z; } Are floats enough? class Face { Pt[] verts; Pt normal; } Assumes flat or Gouraud shading List instead of array: planning on many dynamic updates? class Scene. Object { Scene. Object parent; List<Scene. Object> children; Matrix 4 x 4 transform; Face[] faces; } 4 x 4 matrix: arbitrary sequences of affine transforms Array instead of list: planning on loading all data up front?

Polygon data structures l When designing your data structures, consider interactions and interrogations. • • If you’re going to move vertices, you’ll need to update faces. If you’re going to render with crease angles, you’ll need to track edges. If you want to be able to calculate vertex normals or curvature, your vertices will have to know about surrounding faces. Is memory a factor? What about the processing overhead of dereferencing a pointer or array?

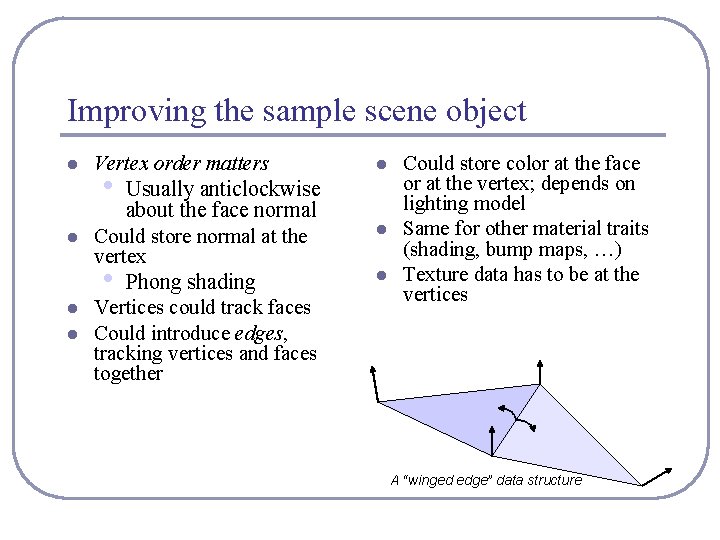

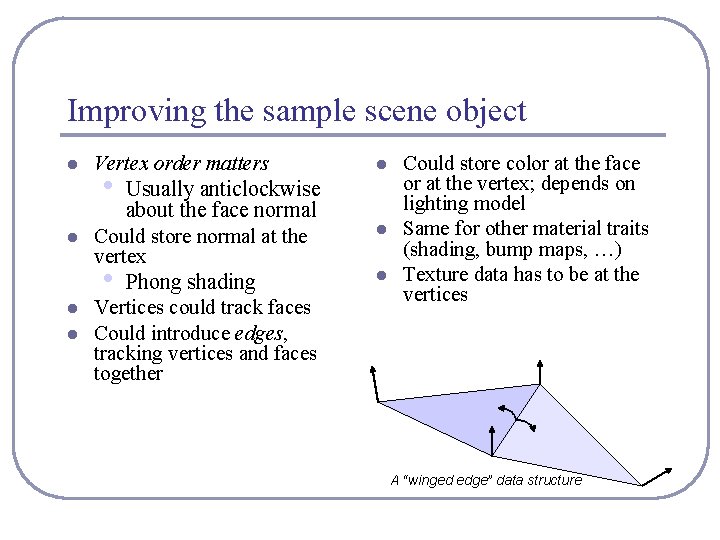

Improving the sample scene object l l Vertex order matters • Usually anticlockwise about the face normal Could store normal at the vertex • Phong shading Vertices could track faces Could introduce edges, tracking vertices and faces together l l l Could store color at the face or at the vertex; depends on lighting model Same for other material traits (shading, bump maps, …) Texture data has to be at the vertices A “winged edge” data structure

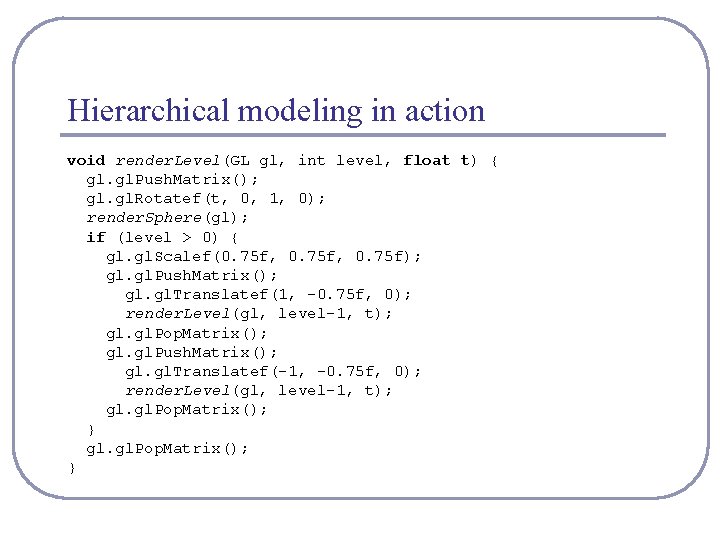

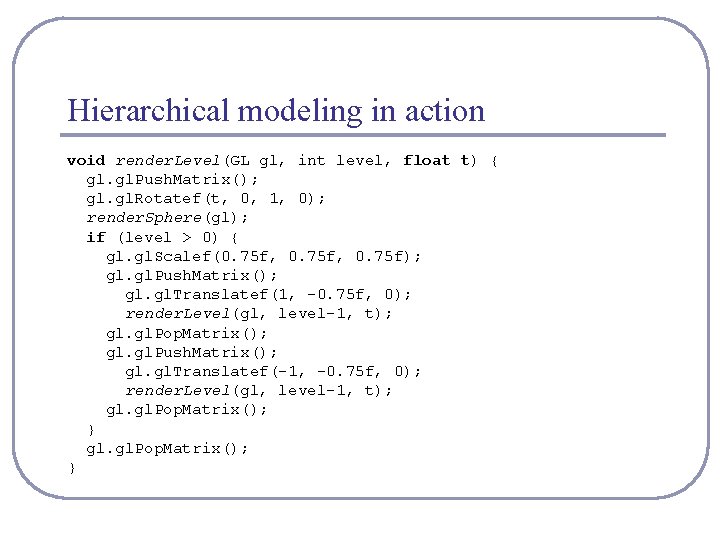

Hierarchical modeling in action void render. Level(GL gl, int level, float t) { gl. Push. Matrix(); gl. Rotatef(t, 0, 1, 0); render. Sphere(gl); if (level > 0) { gl. Scalef(0. 75 f, 0. 75 f); gl. Push. Matrix(); gl. Translatef(1, -0. 75 f, 0); render. Level(gl, level-1, t); gl. Pop. Matrix(); gl. Push. Matrix(); gl. Translatef(-1, -0. 75 f, 0); render. Level(gl, level-1, t); gl. gl. Pop. Matrix(); }

Hierarchical modeling in action

Recommended reading l The Open. GL Programming Guide • Some folks also favor The Open. GL Superbible for • code samples and demos There’s also an Open. GL-ES reference, same series l The Graphics Gems series by Glassner et al l The Neon. Helium online Open. GL tutorials • All the maths you’ve already forgotten • http: //nehe. gamedev. net/