Advanced BioLinux Dan Swan Process and system management

Advanced Bio-Linux Dan Swan: Process and system management

Process Management • What is a process? • A process is a single instance of a program running on the system. • A process can be something spawned by the system such as 'syslogd' (a system “daemon” which handles system logging and message trapping from the kernel) or a user started process such as 'gedit' (a text editor). • When a UNIX process starts, it is given a unique number on the system called a 'Process ID' which is shortened to 'PID'. • If 3 users start the same program, 3 instances of the program are launched with different PIDs.

How to view processes • There are two main ways of viewing processes. • To get a 'snapshot' of currently running processes we use ps. • 'ps' on its own lists only the processes being run on the terminal you typed ps at. • Have a go! Type 'ps', then launch emacs with 'emacs &' and type 'ps' again. We will come back to the '&' later. • So how can you see all the processes you are running as a user? • Try 'ps x' – this lists all the processes associated with you as a a user. • How can you list all the processes running on a system? • Try 'ps ax'. Now try 'ps uax'. What do you get extra?

What does the output mean? • The fullest output you get is from ps aux, which lists all the processes on the system with information about user ownership etc. The columns at the top of the output tell you what each column is. • USER = this is the user the process belongs to. System processes that occur at startup are likely to belong to root. • PID = process ID, the individual number assigned to a process. • %CPU = Percentage of the CPU's time spent running this process. • %MEM = Percentage of total memory in use by this process. • VSZ = Total virtual memory size, in 1 K blocks.

Aside: What is virtual memory? • Unix, like other advanced operating systems, allows you to use all of the physical memory installed in your system as well as area(s) of the disk (called swap space) which have been designated for use by the kernel in case the physical memory is insufficient for the tasks at hand. • Virtual memory is simply the sum of the physical memory (RAM) and the total swap space assigned by the system administrator at the system installation time. Mathematically: • Virtual Memory (VM) = Physical RAM + Swap space

What does the output mean 2? • RSS = Real Set Size, the actual amount of physical memory allocated to this process. • TTY = Terminal associated with this process. A ? indicates the process is not connected to a terminal. • STAT = Process state codes. Common states are S - Sleeping, R - Runnable (on run queue), N - Low priority task, Z - Zombie process • START: When the process was started, in hours and minutes, or a day if the process has been running for a while. • TIME = CPU time used by process since it started. • COMMAND = The command name. This can be modified by processes as they run, so don't rely on it abolutely!

How to view processes 2 • If you want a dynamic, changing view of the processes on the system you can use 'top'. • Type 'top' at the command prompt and watch it for a while. • You should see that the processes sometimes 'move'. • 'top' displays a 'ps aux' like output but sorted by %CPU so that the most CPU intensive processes are listed first. • 'top' gives other information such as how long it has been since the last reboot, how many processes are actually running, how intensively the machine is used in different time periods (the load average), how much real and virtual memory is being used, and how much of the virtual memory is cached.

What does the output mean? • The process output is slightly different to ps aux. • • • You will not recognise: PRI = the priority of the process. NI = the 'nice' value of the process. Each process in UNIX has a priority. Long processes which require a lot of CPU can serious affect the performance of a workstation, which affects all users. It is therefore important that long, CPU intensive processes are run at a low priority. • Process priority can be modified with 'nice'.

Being nice to processes • Run 'top'. What priority and nice value is top running at? • Exit 'top' by pressing 'q'. • Run 'nice -n 10 top' – now what priority and nice value is top running at? • Nice values run from -20 (highest priority) to 19 (lowest priority). • What happens if you try to set a higher than default priority (eg with 'nice -n -10 top')? • Any idea why this happens? Or why it is a good thing? • 'top' is an interactive program, not just a display one, beware running it as root as it allows you to do process management.

How to view processes 3 • OK so there's more than 2 ways to view processes – this is a 3 rd, it's not widely used but is often useful. • type 'pstree' at the command line. • As you can see this displays a process tree. • The point is that processes can spawn other processes when running – so what you have is a parent process (so you often see references to PPIDs (parent process ID's), and a child process (which has a PID). • The child processes are the branches of the tree. • You can get a similar result from 'ps aux --forest'.

Process control • What can you do with a process? • Generally four things: – Start – Background – Foreground – Stop • Starting a process just means “run a command” • To stop a process we do one of two things: – If the process is active in the terminal use <CTRL><C> – If the process is not active in the terminal we use 'kill'

Killing things • Lets start a process. Type 'gedit &' in a terminal. • Now lets imagine gedit has crashed and no longer responds to the keyboard or mouse (ie we cannot close it). How do we get rid of the annoying window? • To use kill, we need the PID of the process. • Get the PID using ps (although we don't really need to do this. . ) • Kill the process with 'kill <PID>'. • The gedit window should disappear. • However for crashed code this will not always work, and we have to use some modifiers to the kill command. But first, we need an aside slide.

Aside: Signals • Signals are a basic form of interprocess communication. • There a number of different signals associated with various things. • They have names. . and numbers. People familiar with UNIX may know about “segmentation faults”. These are reported with a SIGSEGV (signal number 11). • Start 'gedit &', get the PID and 'kill -SEGV <PID>' and see what is reported. • Mostly with kill - we want to do one of two things. Kill a recalcitrant crashed process, or restart something. • Lets just remember SIGHUP (signal 1) and SIGKILL (signal 9) for now.

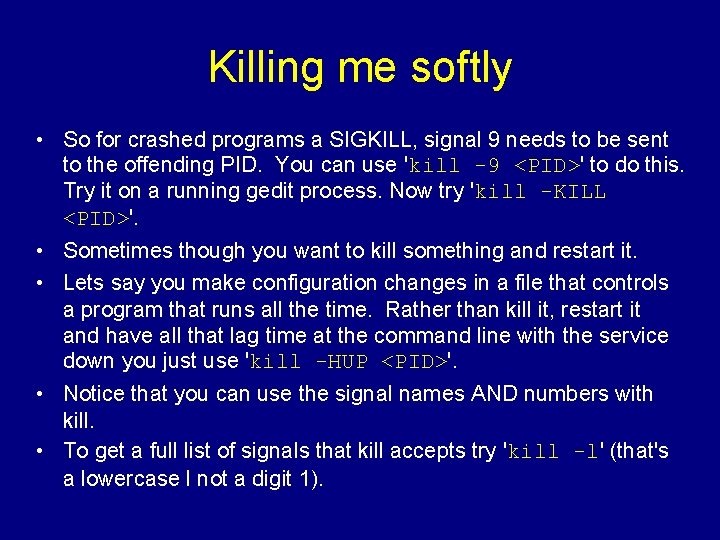

Killing me softly • So for crashed programs a SIGKILL, signal 9 needs to be sent to the offending PID. You can use 'kill -9 <PID>' to do this. Try it on a running gedit process. Now try 'kill -KILL <PID>'. • Sometimes though you want to kill something and restart it. • Lets say you make configuration changes in a file that controls a program that runs all the time. Rather than kill it, restart it and have all that lag time at the command line with the service down you just use 'kill -HUP <PID>'. • Notice that you can use the signal names AND numbers with kill. • To get a full list of signals that kill accepts try 'kill -l' (that's a lowercase l not a digit 1).

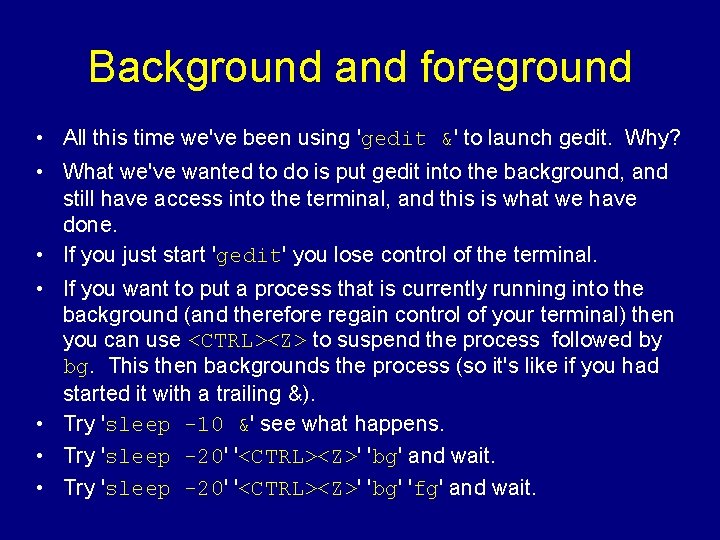

Background and foreground • All this time we've been using 'gedit &' to launch gedit. Why? • What we've wanted to do is put gedit into the background, and still have access into the terminal, and this is what we have done. • If you just start 'gedit' you lose control of the terminal. • If you want to put a process that is currently running into the background (and therefore regain control of your terminal) then you can use <CTRL><Z> to suspend the process followed by bg. This then backgrounds the process (so it's like if you had started it with a trailing &). • Try 'sleep -10 &' see what happens. • Try 'sleep -20' '<CTRL><Z>' 'bg' and wait. • Try 'sleep -20' '<CTRL><Z>' 'bg' 'fg' and wait.

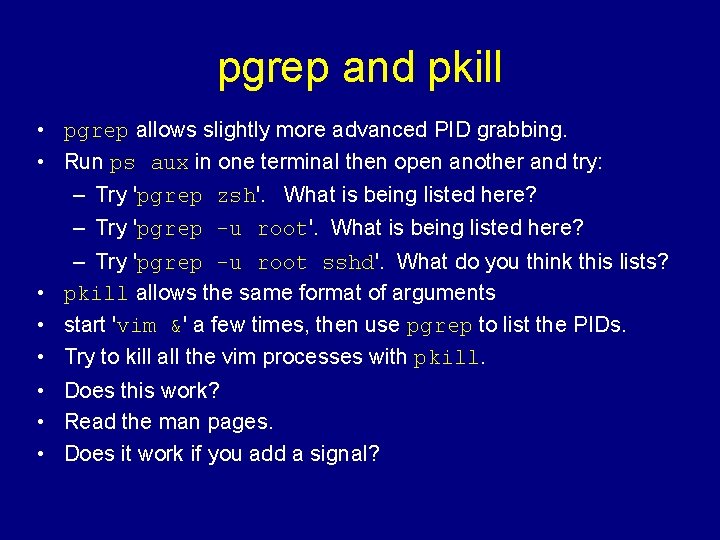

pgrep and pkill • pgrep allows slightly more advanced PID grabbing. • Run ps aux in one terminal then open another and try: – Try 'pgrep zsh'. What is being listed here? – Try 'pgrep -u root sshd'. What do you think this lists? • pkill allows the same format of arguments • start 'vim &' a few times, then use pgrep to list the PIDs. • Try to kill all the vim processes with pkill. • Does this work? • Read the man pages. • Does it work if you add a signal?

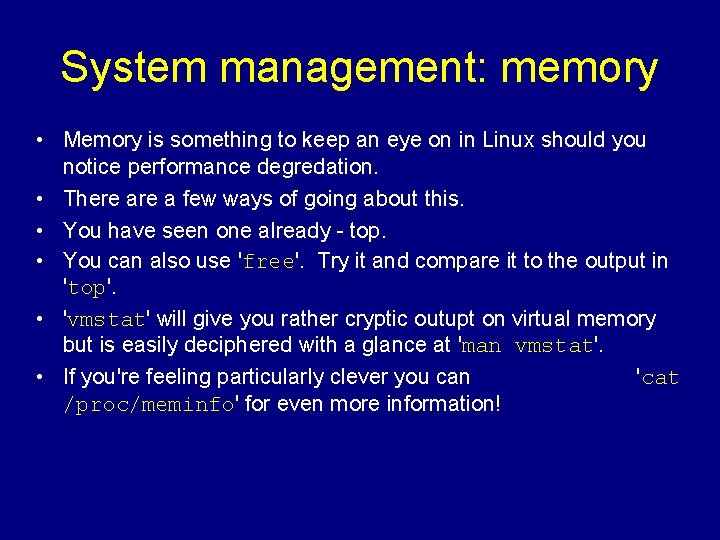

System management: memory • Memory is something to keep an eye on in Linux should you notice performance degredation. • There a few ways of going about this. • You have seen one already - top. • You can also use 'free'. Try it and compare it to the output in 'top'. • 'vmstat' will give you rather cryptic outupt on virtual memory but is easily deciphered with a glance at 'man vmstat'. • If you're feeling particularly clever you can 'cat /proc/meminfo' for even more information!

Disk space • There are two commonly required tasks with disk space. – Checking the amount of disk space left. – Calculating the size of a directory on the disk. • To view the amount of diskspace on your machine use 'df -m'. • The important thing to keep an eye on is the Use% column. When things get close to 100% on a partition, things will stop working. Then it's time to hunt down offending large files, for which you will need to assess the size of a directory. • To get the size of a directory use 'du -m <directory>' to get the size in megabytes (do 'du -k <directory>' to get the size in kilobytes).

All in one stop! • In order to centralise much of the preceeding information, you can use a graphical resource monitoring tool to keep you updated on the status of the system. • Bio-Linux comes with such a tool - 'gtop' (or 'gnome-systemmonitor' in more recent GNOME releases). • This allows you to view process lists, send processes signals (SIGKILL/SIGHUP etc), get memory maps of processes (so you can see which files a process is using), check CPU load, uptime, memory usage and file system information. • It's best to know where all this information comes from, a real sysadmin does not rely on graphical tools to assess the state of a system. One day you might be on a server without a GUI. . .

Controlling process timing • Let's say you have written a program that checks a database for new data deposited. You manually run this everyday to check for new data and download it every day so that you are always up to date. You then go on holiday for a week, but you don't want the data to get out of date. How can you schedule your program to run daily? • UNIX systems have a utility (daemon) which runs all the time and allows you to schedule jobs to run hourly, daily, weekly, monthly etc. • This daemon is called cron.

Controlling cron • Cron is reasonably easy to interface with. • Cron examines something called a 'crontab' file (/etc/crontab) to determine which jobs should be run, and when. • 'less /etc/crontab/' • The * * * fields are populated with numbers and these numbers control the time at which the job is run: • [0 -59] | [0 -23] | [1 -31] | [1 -12] | [0 -6] • mins | hours | days | months | day of week • Sunday = 0! • Can you work out exactly when the specified entries will run?

The other bits of cron • Let's say that you are happy to let cron run its hourly and daily tasks at the times specified in the crontab file. • One of the things Bio-Linux does on a daily basis is to backup the data on the partitions to the second hard drive (/dev/hdb). • The script that controls the backups runs daily because it is in /etc/cron-daily/. • 'less /etc/cron-daily/backup. sh'. • You can see it is just a standard shell script. • If I wanted to run something hourly I would put a shell script in /etc/cron-hourly/. • The crontab files runs everything in the cron-daily directory daily etc.

Advanced Bio-Linux Dan Swan: Further Linux command line II

The flexible command line • At every stage in a sytems administrators life the command line stops being continual use of 'ls, pwd, tar, gzip, locate' and increasingly complex tasks are performed as familiarity with the shell interface. • One of the nice features of the command line is pattern matching with regular expressions (which will be familiar to those who attended our recent Perl course). • There are two commands that reply a lot on pattern matching. • sed the 'stream editor' • grep, which allows you to search for patterns in files.

she sed what? • Sed is a stream editor. A stream editor is used to perform basic text transformations on an input stream (a file or input from a pipeline). • What can sed do? • Create a text file (sed. txt) with the following text: – I like dogs, but I hate cats, and as for mice - yuk! • 'sed -e 's/dogs/rats/g' sed. txt'. • 'sed -e 's/dogs/rats/g' -e 's/cats/moles/g' sed. txt' • sed reads the standard input into the pattern space, performs a sequence of editing commands on the pattern space, then writes the pattern space to STDOUT.

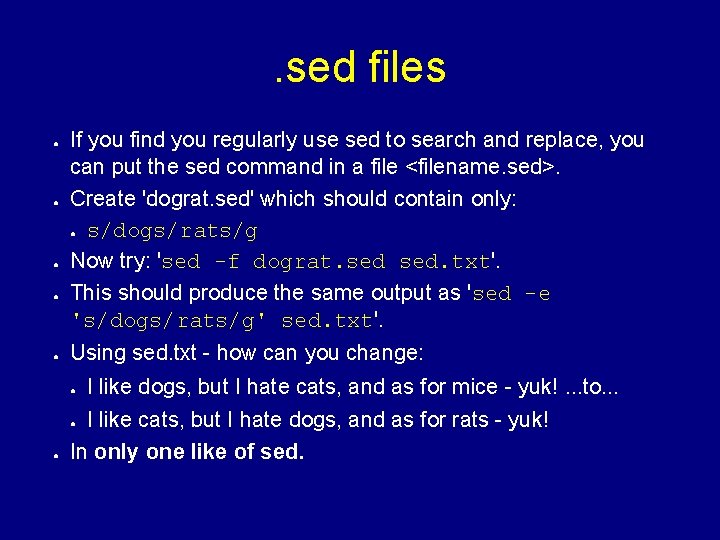

. sed files ● ● ● If you find you regularly use sed to search and replace, you can put the sed command in a file <filename. sed>. Create 'dograt. sed' which should contain only: ● s/dogs/rats/g Now try: 'sed -f dograt. sed. txt'. This should produce the same output as 'sed -e 's/dogs/rats/g' sed. txt'. Using sed. txt - how can you change: ● I like cats, but I hate dogs, and as for rats - yuk! In only one like of sed. ● ● I like dogs, but I hate cats, and as for mice - yuk!. . . to. . .

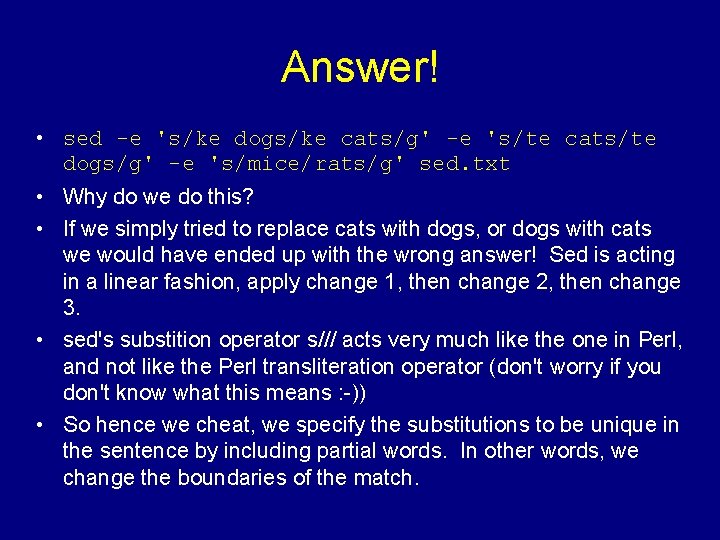

Answer! • sed -e 's/ke dogs/ke cats/g' -e 's/te cats/te dogs/g' -e 's/mice/rats/g' sed. txt • Why do we do this? • If we simply tried to replace cats with dogs, or dogs with cats we would have ended up with the wrong answer! Sed is acting in a linear fashion, apply change 1, then change 2, then change 3. • sed's substition operator s/// acts very much like the one in Perl, and not like the Perl transliteration operator (don't worry if you don't know what this means : -)) • So hence we cheat, we specify the substitutions to be unique in the sentence by including partial words. In other words, we change the boundaries of the match.

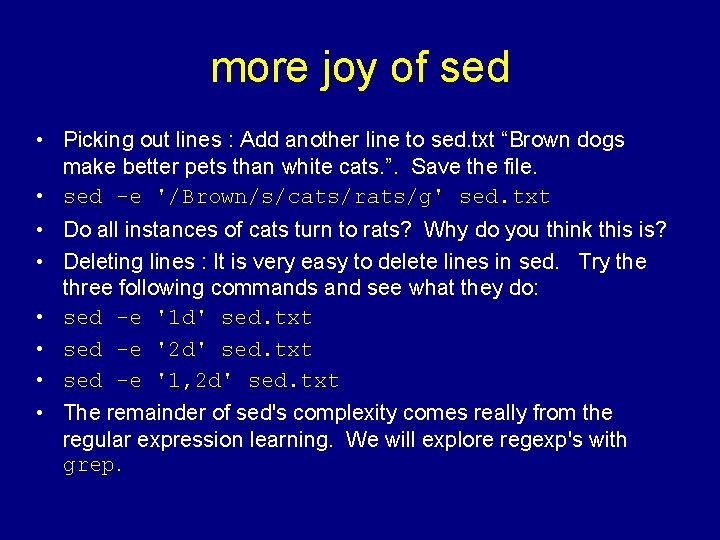

more joy of sed • Picking out lines : Add another line to sed. txt “Brown dogs make better pets than white cats. ”. Save the file. • sed -e '/Brown/s/cats/rats/g' sed. txt • Do all instances of cats turn to rats? Why do you think this is? • Deleting lines : It is very easy to delete lines in sed. Try the three following commands and see what they do: • sed -e '1 d' sed. txt • sed -e '2 d' sed. txt • sed -e '1, 2 d' sed. txt • The remainder of sed's complexity comes really from the regular expression learning. We will explore regexp's with grep.

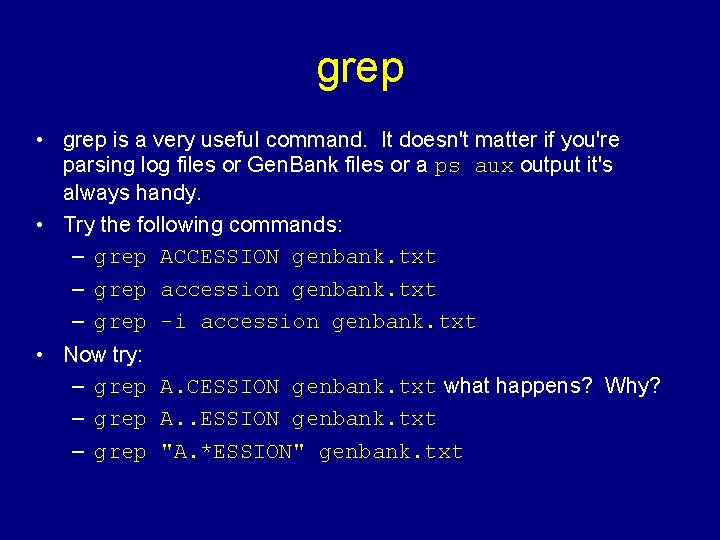

grep • grep is a very useful command. It doesn't matter if you're parsing log files or Gen. Bank files or a ps aux output it's always handy. • Try the following commands: – grep ACCESSION genbank. txt – grep accession genbank. txt – grep -i accession genbank. txt • Now try: – grep A. CESSION genbank. txt what happens? Why? – grep A. . ESSION genbank. txt – grep "A. *ESSION" genbank. txt

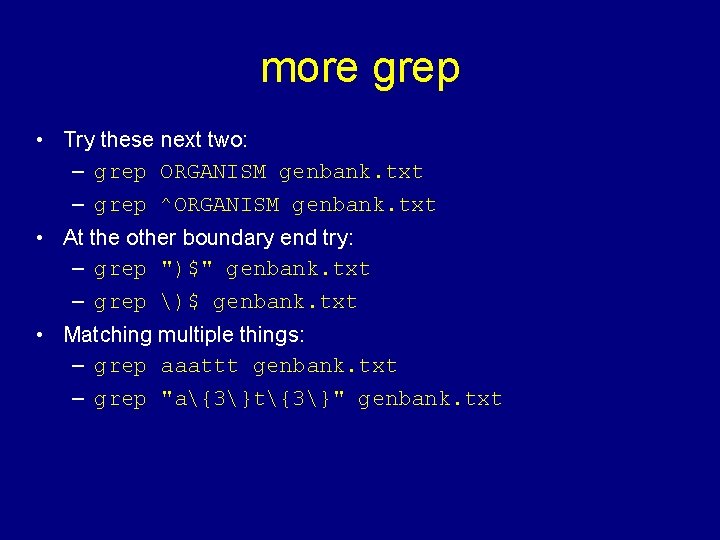

more grep • Try these next two: – grep ORGANISM genbank. txt – grep ^ORGANISM genbank. txt • At the other boundary end try: – grep ")$" genbank. txt – grep )$ genbank. txt • Matching multiple things: – grep aaattt genbank. txt – grep "a{3}t{3}" genbank. txt

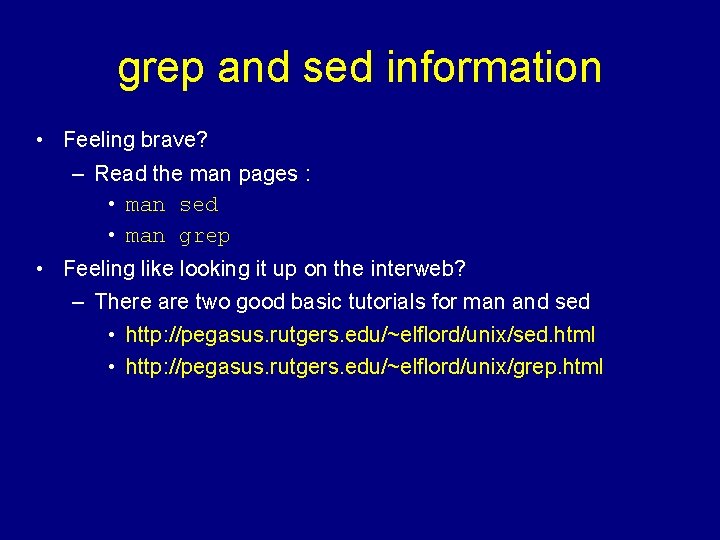

grep and sed information • Feeling brave? – Read the man pages : • man sed • man grep • Feeling like looking it up on the interweb? – There are two good basic tutorials for man and sed • http: //pegasus. rutgers. edu/~elflord/unix/sed. html • http: //pegasus. rutgers. edu/~elflord/unix/grep. html

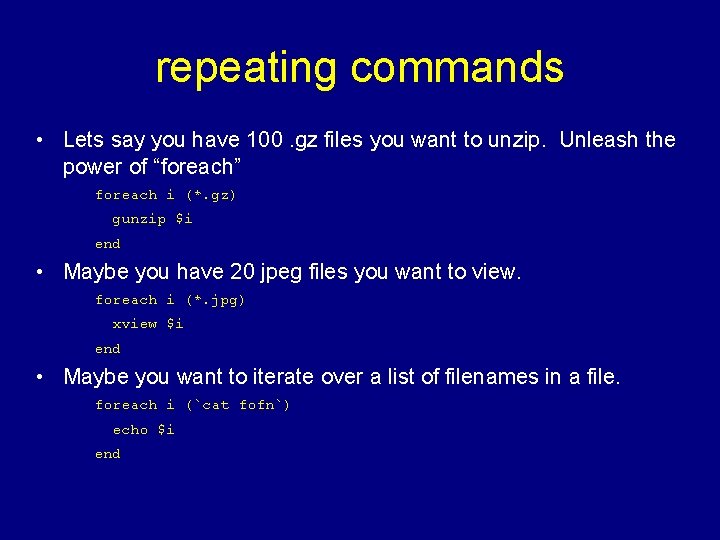

repeating commands • Lets say you have 100. gz files you want to unzip. Unleash the power of “foreach” – foreach i (*. gz) – gunzip $i – end • Maybe you have 20 jpeg files you want to view. – foreach i (*. jpg) – xview $i – end • Maybe you want to iterate over a list of filenames in a file. – foreach i (`cat fofn`) – echo $i – end

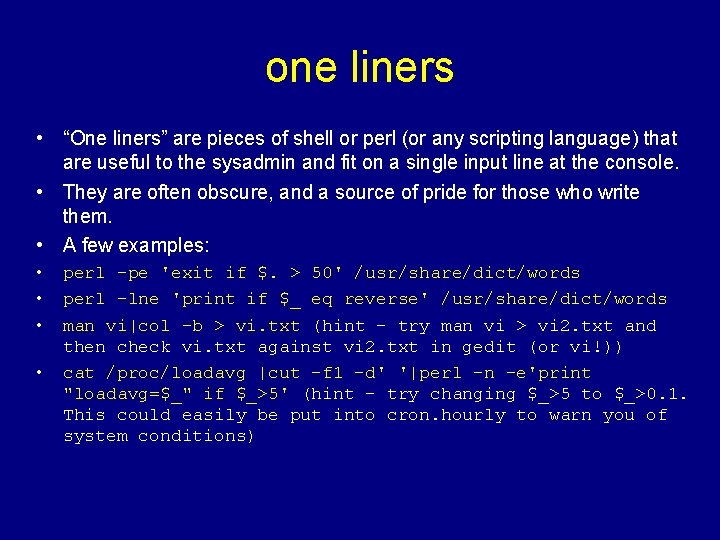

one liners • “One liners” are pieces of shell or perl (or any scripting language) that are useful to the sysadmin and fit on a single input line at the console. • They are often obscure, and a source of pride for those who write them. • A few examples: • • perl -pe 'exit if $. > 50' /usr/share/dict/words perl -lne 'print if $_ eq reverse' /usr/share/dict/words man vi|col -b > vi. txt (hint - try man vi > vi 2. txt and then check vi. txt against vi 2. txt in gedit (or vi!)) cat /proc/loadavg |cut -f 1 -d' '|perl -n -e'print "loadavg=$_" if $_>5' (hint - try changing $_>5 to $_>0. 1. This could easily be put into cron. hourly to warn you of system conditions)

Advanced Bio-Linux Dan Swan: Essential Systems Administration

Software installation • There are two main ways of getting software onto your Bio. Linux machine. • The first is to use RPM's. • rpm is the Red. Hat package manager and allows the installation, removal, upgrading and listing of packages installed on the system. It is reasonably flexible, and is used to install the Red. Carpet package updates etc. on your system. The software is pre-compiled for your architechture. • The second is to compile from source. • This means you get the source code, and make the package on your local machine using a compiler. This is not hard.

rpm basics • rpm -qa : list all rpm's installed on the system. • Beware naming! In all likelyhood you will download something called : super_new_package-1. 51. ix 86. rpm • When this is installed it will just be listed as super_new_package-1. 51 in an rpm -qa output. The ix 86. rpm bit is lost. • To install an rpm you use rpm -i <rpm_name>. rpm • This will warn you of failed dependencies if there any. • This can be a major headache, quite often you will find yourself looking for 3 or more dependencies in order to get a piece of software working. • There is also the possibility of “circular dependencies” by which package 1 relies on package 2 relies on package 3 relies on package 1. This is uncommon, but possible.

rpm basics 2 • One frequent rpm task is to upgrade an existing rpm on the system. • If you attempt to install the same, or a previous version of an rpm, rpm will warn you that you cannot do this. • To cleanly upgrade an rpm on the system use the following syntax: • rpm -Uvh <rpm_name. rpm> • U = upgrade • v = verbose • h = hash printing (pretty ##### display as it upgrades)

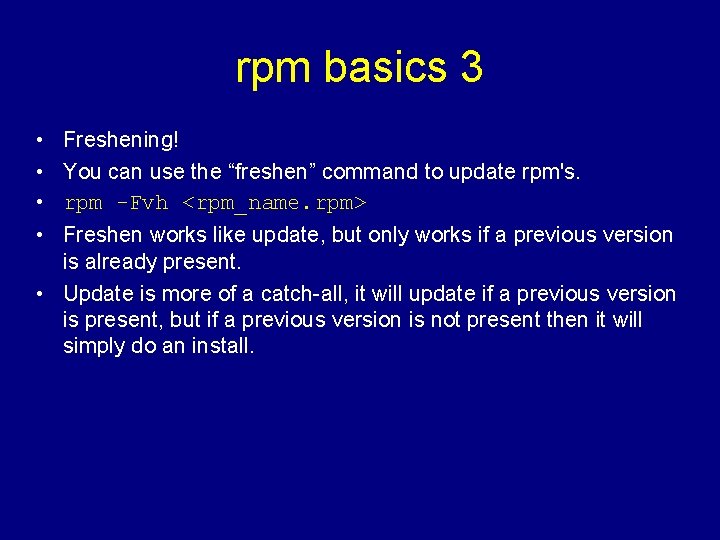

rpm basics 3 • • Freshening! You can use the “freshen” command to update rpm's. rpm -Fvh <rpm_name. rpm> Freshen works like update, but only works if a previous version is already present. • Update is more of a catch-all, it will update if a previous version is present, but if a previous version is not present then it will simply do an install.

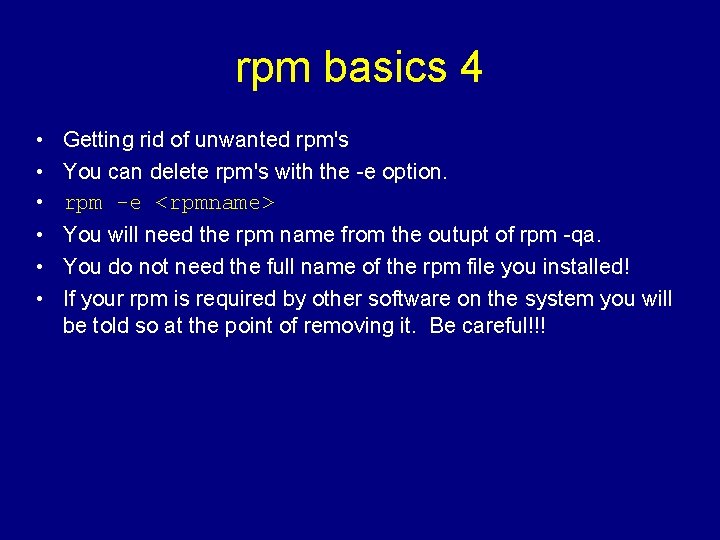

rpm basics 4 • • • Getting rid of unwanted rpm's You can delete rpm's with the -e option. rpm -e <rpmname> You will need the rpm name from the outupt of rpm -qa. You do not need the full name of the rpm file you installed! If your rpm is required by other software on the system you will be told so at the point of removing it. Be careful!!!

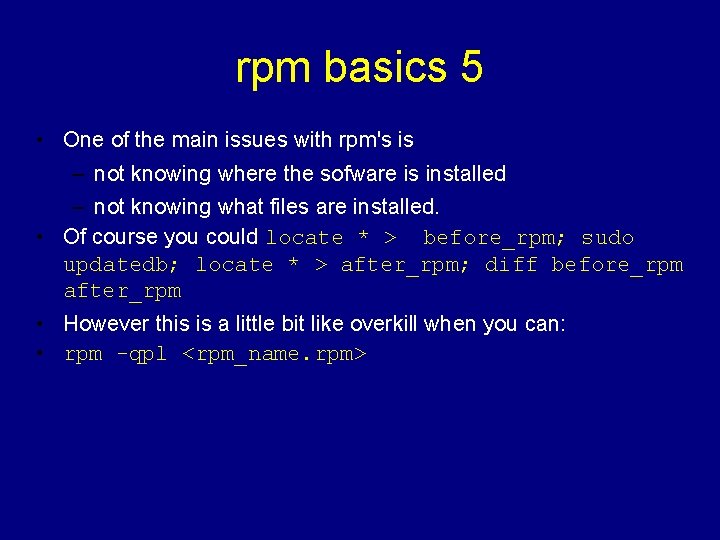

rpm basics 5 • One of the main issues with rpm's is – not knowing where the sofware is installed – not knowing what files are installed. • Of course you could locate * > before_rpm; sudo updatedb; locate * > after_rpm; diff before_rpm after_rpm • However this is a little bit like overkill when you can: • rpm -qpl <rpm_name. rpm>

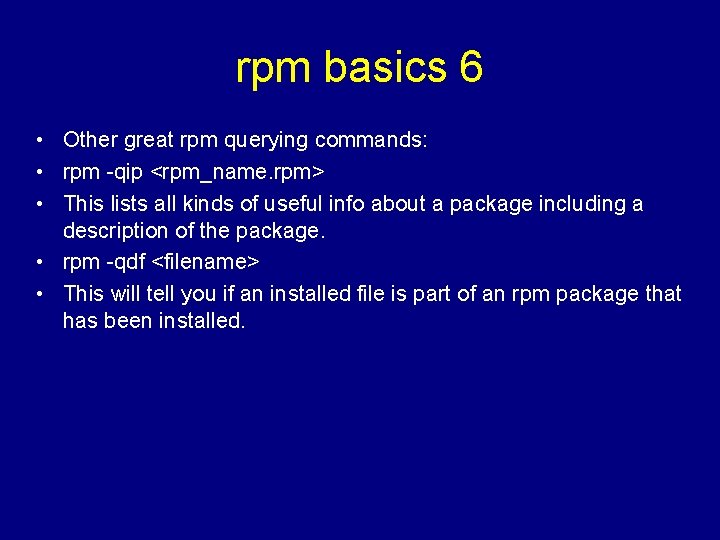

rpm basics 6 • Other great rpm querying commands: • rpm -qip <rpm_name. rpm> • This lists all kinds of useful info about a package including a description of the package. • rpm -qdf <filename> • This will tell you if an installed file is part of an rpm package that has been installed.

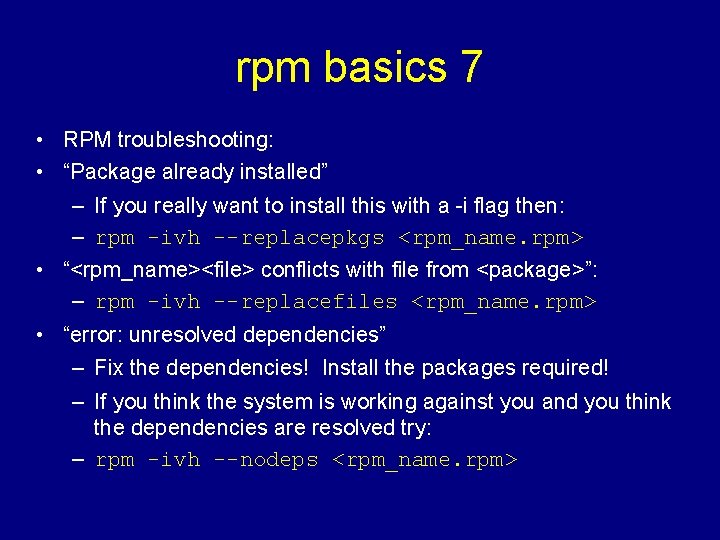

rpm basics 7 • RPM troubleshooting: • “Package already installed” – If you really want to install this with a -i flag then: – rpm -ivh --replacepkgs <rpm_name. rpm> • “<rpm_name><file> conflicts with file from <package>”: – rpm -ivh --replacefiles <rpm_name. rpm> • “error: unresolved dependencies” – Fix the dependencies! Install the packages required! – If you think the system is working against you and you think the dependencies are resolved try: – rpm -ivh --nodeps <rpm_name. rpm>

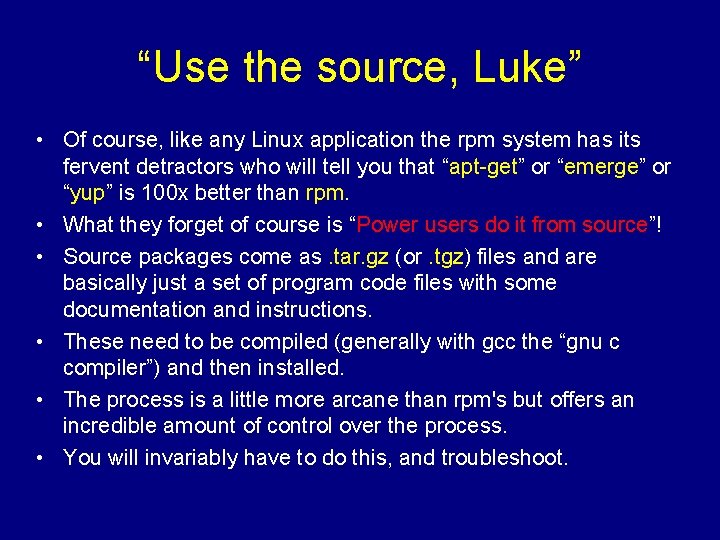

“Use the source, Luke” • Of course, like any Linux application the rpm system has its fervent detractors who will tell you that “apt-get” or “emerge” or “yup” is 100 x better than rpm. • What they forget of course is “Power users do it from source”! • Source packages come as. tar. gz (or. tgz) files and are basically just a set of program code files with some documentation and instructions. • These need to be compiled (generally with gcc the “gnu c compiler”) and then installed. • The process is a little more arcane than rpm's but offers an incredible amount of control over the process. • You will invariably have to do this, and troubleshoot.

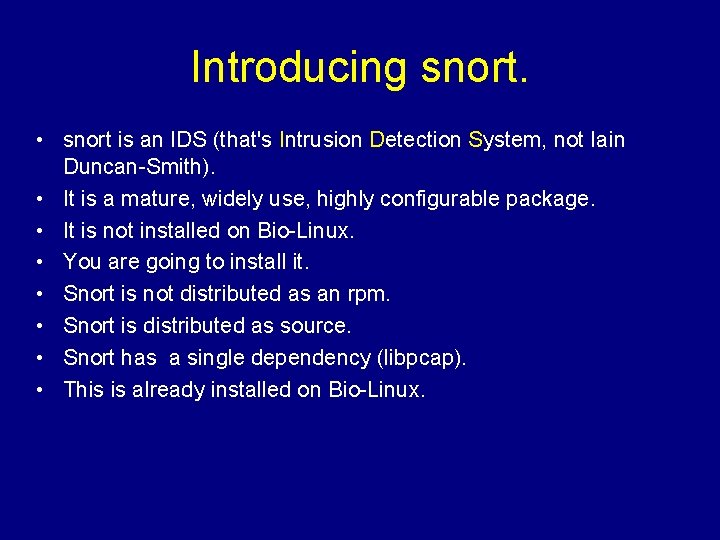

Introducing snort. • snort is an IDS (that's Intrusion Detection System, not Iain Duncan-Smith). • It is a mature, widely use, highly configurable package. • It is not installed on Bio-Linux. • You are going to install it. • Snort is not distributed as an rpm. • Snort is distributed as source. • Snort has a single dependency (libpcap). • This is already installed on Bio-Linux.

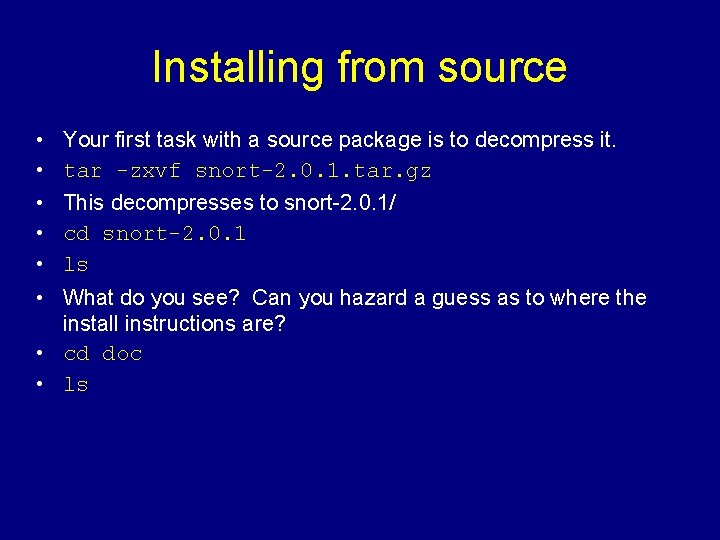

Installing from source • • • Your first task with a source package is to decompress it. tar -zxvf snort-2. 0. 1. tar. gz This decompresses to snort-2. 0. 1/ cd snort-2. 0. 1 ls What do you see? Can you hazard a guess as to where the install instructions are? • cd doc • ls

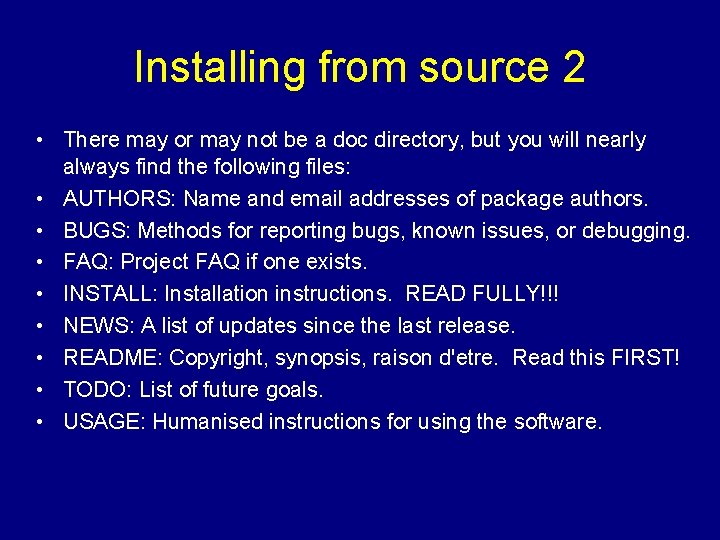

Installing from source 2 • There may or may not be a doc directory, but you will nearly always find the following files: • AUTHORS: Name and email addresses of package authors. • BUGS: Methods for reporting bugs, known issues, or debugging. • FAQ: Project FAQ if one exists. • INSTALL: Installation instructions. READ FULLY!!! • NEWS: A list of updates since the last release. • README: Copyright, synopsis, raison d'etre. Read this FIRST! • TODO: List of future goals. • USAGE: Humanised instructions for using the software.

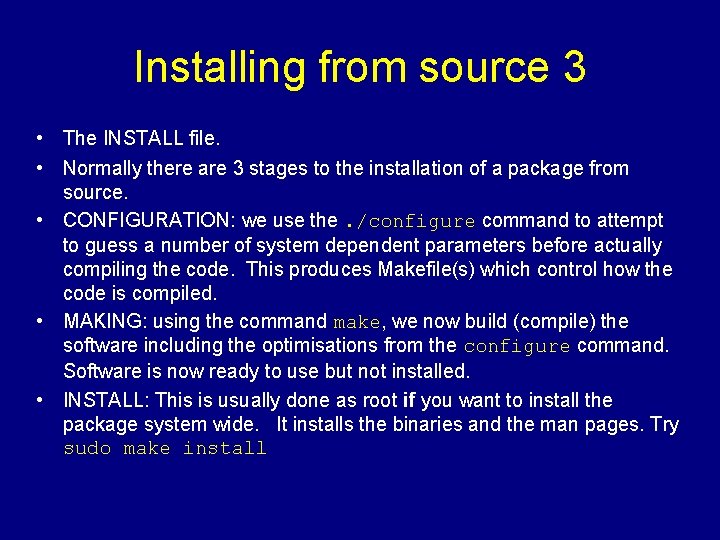

Installing from source 3 • The INSTALL file. • Normally there are 3 stages to the installation of a package from source. • CONFIGURATION: we use the. /configure command to attempt to guess a number of system dependent parameters before actually compiling the code. This produces Makefile(s) which control how the code is compiled. • MAKING: using the command make, we now build (compile) the software including the optimisations from the configure command. Software is now ready to use but not installed. • INSTALL: This is usually done as root if you want to install the package system wide. It installs the binaries and the man pages. Try sudo make install

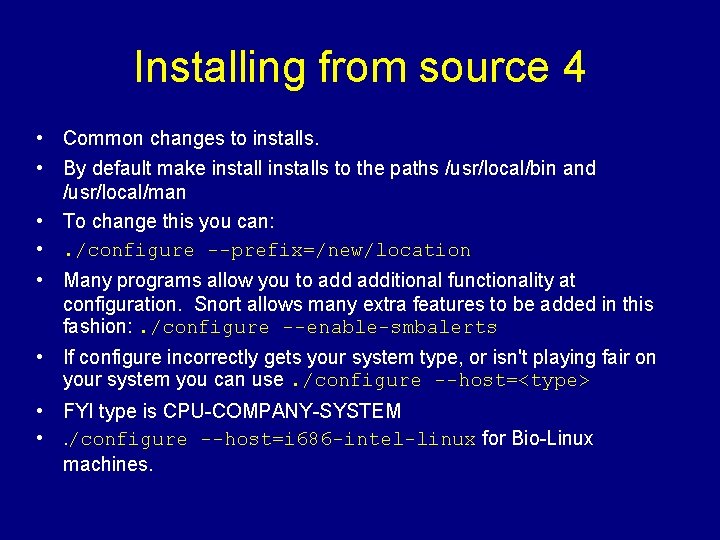

Installing from source 4 • Common changes to installs. • By default make installs to the paths /usr/local/bin and /usr/local/man • To change this you can: • . /configure --prefix=/new/location • Many programs allow you to additional functionality at configuration. Snort allows many extra features to be added in this fashion: . /configure --enable-smbalerts • If configure incorrectly gets your system type, or isn't playing fair on your system you can use. /configure --host=<type> • FYI type is CPU-COMPANY-SYSTEM • . /configure --host=i 686 -intel-linux for Bio-Linux machines.

- Slides: 48