Actual Gender Differences There are documented gender differences

- Slides: 36

Actual Gender Differences • There are documented gender differences – Exs: aggression, activity level, compliance, emotional expressivity

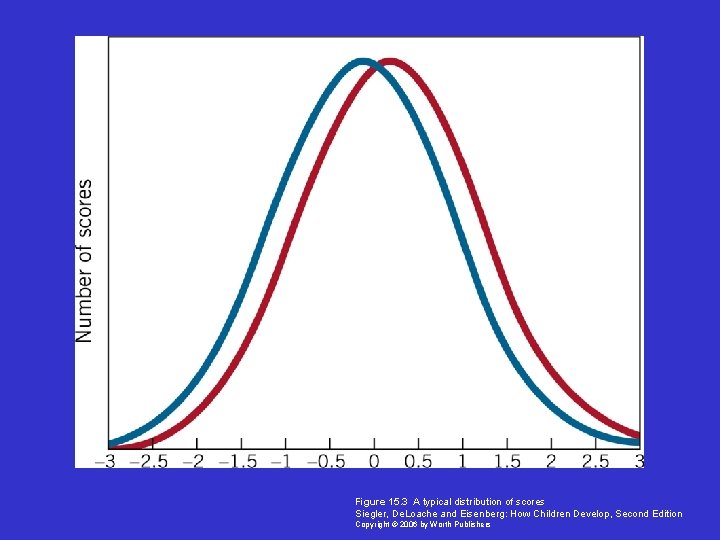

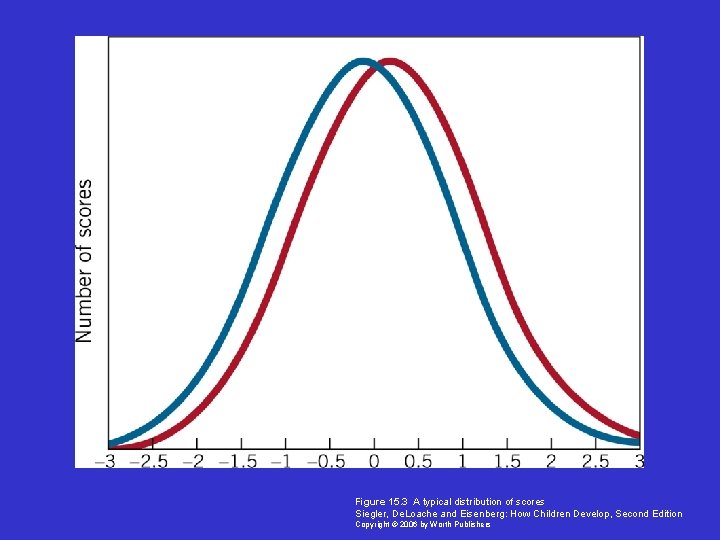

But: • Relatively few documented differences – Gender stereotypes suggest more differences than are actually documented by research • Even documented differences are relatively small in size – Average performance of males and females is not extremely different

Figure 15. 3 A typical distribution of scores Siegler, De. Loache and Eisenberg: How Children Develop, Second Edition Copyright © 2006 by Worth Publishers

Gender Typing • Process by which a child: – Becomes aware of his or her gender and that of other people – Acquires information about the characteristics and behavior viewed as appropriate for males or females (gender stereotypes) – Acquires the characteristics and behaviors viewed as appropriate for either males or females (gender roles)

Development of Gender Awareness • By 2. 5 to 3 years, children label their own sex and that of other people • Do not yet understand that sex is a permanent characteristic

Development of Gender Stereotypes • By 2. 5 years, children have some knowledge of gender stereotypes • Over the preschool/early school years, learn more about toys, activities, and achievement domains considered appropriate for boys versus girls – Ex (achievement): boys are good at math; girls are good at English

• Preschoolers’ gender stereotypes tend to be rigid – Don’t usually realize that characteristics associated with sex (e. g. , activities, clothing) don’t determine whether one is male or female • May be one reason they treat gender stereotypes as “rules” rather than as beliefs

• By elementary school, children’s gender stereotypes are more flexible – Understand that stereotypes are beliefs, not “rules” – However, older children do not necessarily approve of “cross-gender” behavior

Development of Gender Role Behavior • Between approximately 14 -22 months, children begin to show sex-typed toy preferences • Sex-typed toy play increases through the preschool years • Children begin to avoid peers who violate gender roles

• Gender segregation develops by ages 2 to 3 years – Tendency to associate with same-sex playmates • Typically lasts until around the onset of puberty

Biological Influences on Gender Typing (Hormonal Influences) • Experimental animal studies indicate that exposure to androgens (male sex hormones): – Increases active play in male and female mammals – Promotes male-typical sexual behavior and aggression and suppresses maternal caregiving behavior in a wide variety of species

Humans: • Cannot do experimental research for ethical reasons – Correlational research

• In boys, naturally occurring variations in androgen levels are positively correlated with – Amount of rough-and-tumble play – Levels of physical aggression

• Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH) – Disorder in which child is exposed to high levels of androgens from the prenatal period onward – Compared to girls without CAH, girls with CAH show • Higher activity levels • Greater interest in “male-typical” toys, activities, and occupations • Better spatial/mathematical abilities

Environmental Influences on Gender Typing • Social Learning Theory – Gender typing results from • Observational learning – By watching male and female “models”, children learn “appropriate” appearance, activities/occupations, and behavior for each sex • Rewards and punishments associated with gendertyped behavior – Rewards for conforming to appropriate gender role and lack of rewards and/or punishment for failure to conform

Parental Behavior • On average, data suggest that differences in parental treatment of boys and girls are not large • Does not mean that parental behavior is unimportant because: – Younger children receive more direct “training” from parents about gender roles than do older children – Parents vary in the extent to which they practice differential treatment

Evidence for Differential Treatment • Some data indicate that parents – Provide gender-stereotyped toys (e. g. , vehicles, dolls) – Are more responsive when children engage in “gender-appropriate” play • But data are not always consistent across studies – Parents also provide gender-neutral toys for children

• Gender-stereotyped toys may encourage different behaviors, characteristics, or abilities in males and females – Parents give toys that encourage action and competition to boys (e. g. , toy weapons, toy vehicles, construction toys and tools, sports equipment) – Parents give toys that encourage nurturance, cooperation, and physical attractiveness to girls (e. g. , dolls/stuffed animals, toy dishes, jewelry, jump ropes)

• Other evidence indicates that parents encourage different behaviors in boys and girls – More likely to encourage independence in boys • Respond more positively when boys demand attention, are highly active, or try to take toys from others • Also more likely to – Refuse or ignore a son’s request for help – Challenge boys in teaching situations (e. g. , offer scientific explanations, ask high-level questions)

– More likely to encourage closeness and dependence in girls • More likely to: – Direct play activities – Provide help – Engage in conversations – Talk about emotions

• Differential treatment of boys and girls may be relatively subtle – Data indicate gender differences in parentchild communication • Parents more likely to offer scientific explanations to sons than to daughters (at a museum) – Ex: “When you turn that fast, it makes more electricity” versus “Turn that handle”

Pasterski et al. (2005) • Comparison of toy choices in girls and boys with CAH and their siblings (without CAH) – Girls with CAH played with “boys’ toys” more and “girls’ toys” less than their unaffected sisters – No differences between boys with CAH and their unaffected brothers

• Parental Behavior – Parents gave more negative responses to their unaffected sons than to their unaffected daughters for play with “girls’ toys” – Parents gave more positive responses to daughters with CAH than to unaffected daughters for play with “girls’ toys”

• Parental Behavior and Children’s Toy Choices – For unaffected children, parents’ positive and negative responses to children’s toy choices were related to children’s play behavior • Positive responses to children’s play with certain toys related to more play with those toys (and vice versa for negative responses) – For children with CAH, parental behavior was not related to children’s toy choices

Peer Behavior • By age 3, children reinforce each other for “gender-appropriate” play (e. g. , by praising, imitating, or joining in) • Criticize children who engage in “crossgender” activities – Boys are especially critical of other boys

• Male and female peer groups may promote different styles of interaction – Boys more often rely on commands, threats, and physical force – Girls use polite requests, persuasion— works with girls but not with boys

• Cognitive theories emphasize children’s active role in the process of gender typing (self-socialization)

Cognitive Developmental Theory (Kohlberg) • Three Stages: – Basic Gender Identity: • Recognition that one is a boy or a girl – Emerges between 2. 5 and 3 years

– Gender Stability • Understanding that gender is stable over time – Emerges between 3 and 5 years

– Gender Constancy/Consistency • Understanding that gender is constant/consistent across situations regardless of appearance or activities – Emerges between 5 and 7 years

• Kohlberg: Gender constancy leads to adoption of gender roles – Why is this incorrect?

Gender Schema Theory: • Children construct gender schemas – Organized mental representations incorporating information about gender • Include children’s own experiences and information conveyed by others, including gender stereotypes • Schemas are dynamic—change as children acquire additional information

• Once children achieve basic gender identity, they are motivated to conform to gender roles • Motivated to prefer, pay attention to, and remember more about others of their own sex • Children use gender schemas to process information and guide their behavior

Gender Schema Theory: Evidence Martin et al. (1995) Study 3: – Children used gender labels given to toys to guide their behavior • Ex: If a toy was labeled as a “boy” toy, girls reported that they were less interested in it and that other girls would also be less interested in it than if the toy was labeled as a “girl” toy (and vice versa for boys) – True even if the toy was very attractive

• Children also show biases in their memory for information about gender – More likely to accurately remember information that is consistent with gender stereotypes – More likely to forget or distort information that is inconsistent with gender stereotypes