Achieving Byzantine Agreement and Broadcast against Rational Adversaries

Achieving Byzantine Agreement and Broadcast against Rational Adversaries Adam Groce Aishwarya Thiruvengadam Ateeq Sharfuddin CMSC 858 F: Algorithmic Game Theory University of Maryland, College Park

Overview o Byzantine agreement and broadcast are central primitives in distributed computing and cryptography. o The original paper proves (LPS 1982) that successful protocols can only be achieved if the number of adversaries is 1/3 rd the number of players.

Our Work o We take a game-theoretic approach to this problem o We analyze rational adversaries with preferences on outputs of the honest players. o We define utilities rational adversaries might have. o We then show that with these utilities, Byzantine agreement is possible with less than half the players being adversaries o We also show that broadcast is possible for any number of adversaries with these utilities.

The Byzantine Generals Problem o Introduced in 1980/1982 by Leslie Lamport, Robert Shostak, and Marshall Pease. o Originally used to describe distributed computation among fallible processors in an abstract manner. o Has been applied to fields requiring fault tolerance or with adversaries.

General Idea o The n generals of the Byzantine empire have encircled an enemy city. o The generals are far away from each other necessitating messengers to be used for communication. o The generals must agree upon a common plan (to attack or to retreat).

General Idea (cont. ) o Up to t generals may be traitors. o If all good generals agree upon the same plan, the plan will succeed. o The traitors may mislead the generals into disagreement. o The generals do not know who the traitors are.

General Idea (cont. ) o A protocol is a Byzantine Agreement (BA) protocol tolerating t traitors if the following conditions hold for any adversary controlling at most t traitors: A. All loyal generals act upon the same plan of action. B. If all loyal generals favor the same plan, that plan is adopted.

General Idea (broadcast) o Assume general i acting as the commanding general, and sending his order to the remaining n-1 lieutenant generals. o A protocol is a broadcast protocol tolerating t traitors if these two conditions hold: 1. All loyal lieutenants obey the same order. 2. If the commanding general is loyal, then every loyal lieutenant general obeys the order he sends.

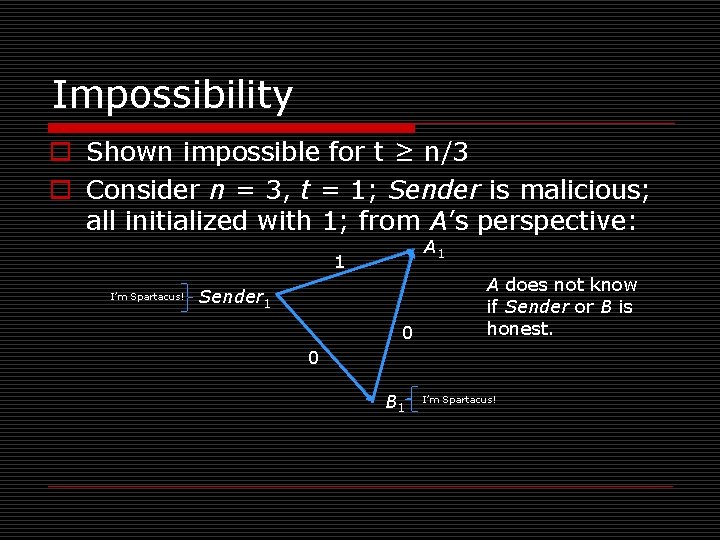

Impossibility o Shown impossible for t ≥ n/3 o Consider n = 3, t = 1; Sender is malicious; all initialized with 1; from A’s perspective: A 1 1 I’m Spartacus! Sender 1 0 A does not know if Sender or B is honest. 0 B 1 I’m Spartacus!

Equivalence of BA and Broadcast o Given a protocol for broadcast, we can construct a protocol for Byzantine agreement. 1. All players use the broadcast protocol to send their input to every other player. 2. All players output the value they receive from a majority of the other players.

Equivalence of BA and Broadcast o Given a protocol for Byzantine agreement, we can construct a protocol for broadcast. 1. The sender sends his message to all other players. 2. All players use the message they received in step 1 as input in a Byzantine agreement protocol. 3. Players output whatever output is given by the Byzantine agreement protocol.

Previous Works o It was shown in PSL 1980 that algorithms can be devised to guarantee broadcast/Byzantine agreement if and only if n ≥ 3 t+1. o If traitors cannot falsely report messages (for example, if a digital signature scheme exists), it can be achieved for n ≥ t ≥ 0. o PSL 1980 and LSP 1982 demonstrated an exponential communication algorithm for reaching BA in t+1 rounds for t < n/3.

Previous Works o Dolev, et al. presented a 2 t+3 round BA with polynomially bounded communication for any t < n/3. o Probabilistic BA protocols tolerating t < n/3 have been shown running in expected time O (t / log n); though running time is high in worst case. o Faster algorithms tolerating (n - 1)/3 faults have been shown if both cryptography and trusted parties are used to initialize the network.

Rational adversaries o All results stated so far assume general, malicious adversaries. o Several cryptographic problems have been studied with rational adversaries n Have known preferences on protocol output n Will only break the protocol if it benefits them o In MPC and secret sharing, rational adversaries allow stronger results o We apply rational adversaries to Byzantine agreement and broadcast

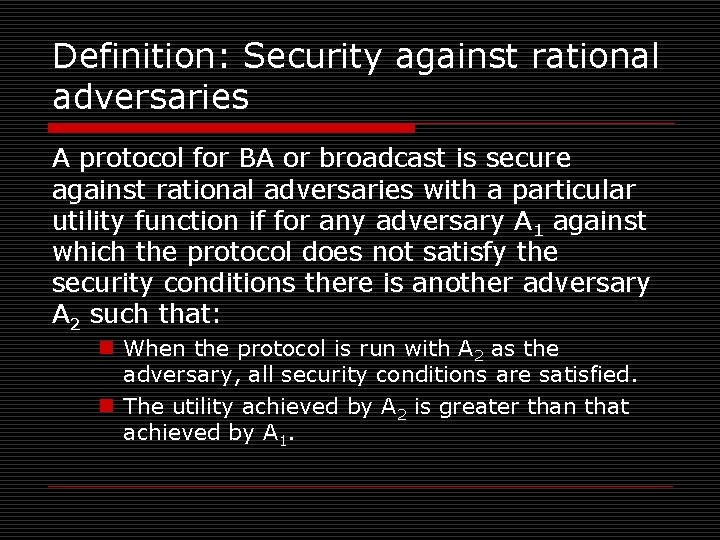

Definition: Security against rational adversaries A protocol for BA or broadcast is secure against rational adversaries with a particular utility function if for any adversary A 1 against which the protocol does not satisfy the security conditions there is another adversary A 2 such that: n When the protocol is run with A 2 as the adversary, all security conditions are satisfied. n The utility achieved by A 2 is greater than that achieved by A 1.

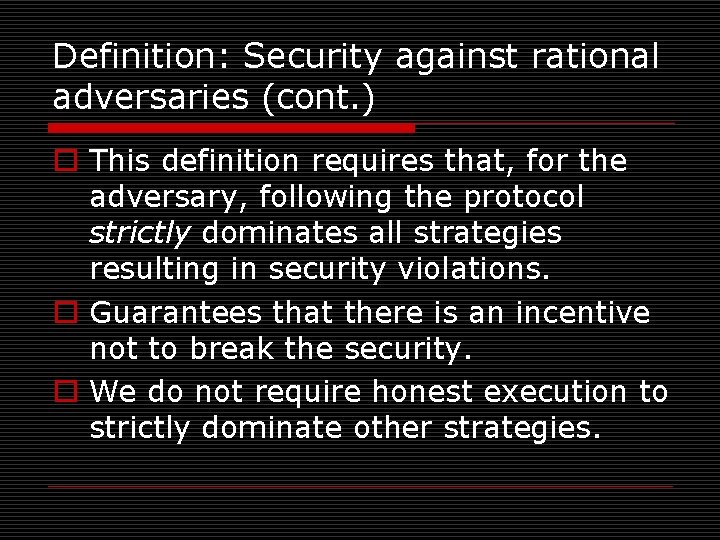

Definition: Security against rational adversaries (cont. ) o This definition requires that, for the adversary, following the protocol strictly dominates all strategies resulting in security violations. o Guarantees that there is an incentive not to break the security. o We do not require honest execution to strictly dominate other strategies.

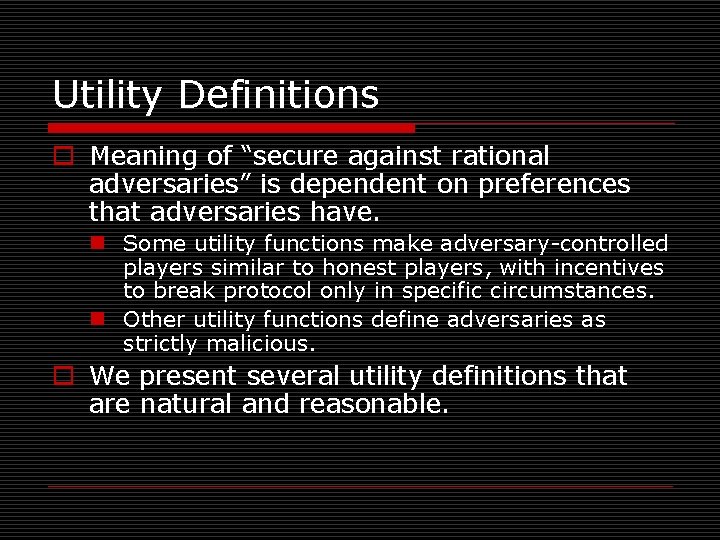

Utility Definitions o Meaning of “secure against rational adversaries” is dependent on preferences that adversaries have. n Some utility functions make adversary-controlled players similar to honest players, with incentives to break protocol only in specific circumstances. n Other utility functions define adversaries as strictly malicious. o We present several utility definitions that are natural and reasonable.

Utility Definitions (cont. ) o We limit to protocols that attempt to broadcast or agree in a single bit. o The output can be one of the following: n All honest players output 1. n All honest players output 0. n Honest players disagree on output.

Utility Definitions (cont. ) o We assume that the adversary knows the inputs of the honest players. o Therefore, the adversary can choose a strategy to maximize utility for that particular input set.

Utility Definitions (cont. ) o Both protocol and adversary can act probabilistically. o So, an adversary’s choice of strategy results not in a single outcome but in a probability distribution over possible outcomes. o We establish a preference ordering on probability distributions.

Strict Preferences o An adversary with “strict preferences” is one that will maximize the likelihood of its first-choice outcome. n For a particular strategy, let a 1 be the probability of the adversary achieving its first-choice outcome and a 2 be the probability of achieving the second choice outcome. n Let b 1 and b 2 be the same probabilities for a second potential strategy. n We say that the first strategy is preferred if and only if a 1 > b 1 or a 1=b 1 and a 2 > b 2.

Strict Preferences (cont. ) o Not a “utility” function in the classic sense o Provides a good model for a very single-minded adversary.

Strict Preferences (cont. ) o We will use shorthand to refer to the ordering of outcomes: n For example: 0 s > disagreement > 1 s. n Denotes an adversary who prefers that all honest players output 0, whose second choice is disagreement, and last choice is all honest players output 1.

Linear Utility o An adversary with “linear utilities” has its utilities defined by: Utility = u 1 Pr[players output 0] + u 2 Pr[players output 1] + u 3 Pr [players disagree] Where u 1 + u 2 + u 3 = 1.

Definition (0 -preferring) o A 0 -preferring adversary is one for which Utility = E[number of honest players outputting 0]. n Not a refinement of the strict ordering adversary with a preference list of 0 s > disagree > 1.

Other possible utility definitions o The utility definitions do not cover all preference orderings. o With n players, there is 2 n output combinations. o There an infinite number of probability distributions on those outcomes. o Any well-ordering on these probability distributions is a valid set of preferences against which security could be guaranteed.

Other possible utility definitions o Our utility definitions preserve symmetry of players, but this is not necessary. o It is also possible that the adversary’s output preferences are a function of the input. o The adversary could be risk-averse o Adversarial players might not all be centrally controlled. n Could have conflicting preferences

Equivalence of Broadcast to BA, revisited o Reductions with malicious adversaries don’t always apply n Building BA from broadcast fails n Building broadcast from BA succeeds

Strict preferences case o Assume a preference ordering of 0 > 1 > disagree. o t < n/2 o Protocol: n Each player sends his input to everyone. n Each player outputs the majority of all inputs he has received. If there is no strict majority, output 0.

Strict preferences case (cont. ) o Proof: n If all honest players held the same input, the protocol terminates with the honest players agreeing despite what the adversary says. n If the honest players do not form a majority, it is in adversarial interest to send 0’s.

Generalizing the proof o Same protocol: n Each player sends his input to everyone. n Each player outputs the majority of all inputs he has received. If there is no strict majority, output 0. o Assume any preference set with allzero output as first choice. o Proof works as before.

A General Solution o Task: To define another protocol that will work for strict preferences with disagree > 0 s > 1 s. o We have not found a simple efficient solution for this case. o Instead, we define a protocol based on Fitzi et al. ’s work on detectable broadcast. n Solves for a wide variety of preferences

Definition: Detectable Broadcast o A protocol for detectable broadcast must satisfy the following three conditions: n Correctness: All honest players either abort or accept and output 0 or 1. If any honest player aborts, so does every other honest player. If no honest players abort then the output satisfies the security conditions of broadcast. n Completeness: If all players are honest, all players accept (and therefore, achieve broadcast without error). n Fairness: If any honest player aborts then the adversary receives no information about the sender’s bit (not relevant to us).

Detectable broadcast (cont. ) o Fitzi’s protocol requires t + 5 rounds and O(n 8 (log n + k)3 ) total bits of communication, where k is a security parameter. o Assumes computationally bounded adversary. o This compares to one round and n 2 bits for the previous protocol. o Using detectable broadcast is much less efficient. o However, this is not as bad when compared to protocals that achieve broadcast against malicious adversaries.

General protocol 1. Run the detectable broadcast protocol 2. - If an abort occurs, output adversary’s least-preferred outcome - Otherwise, output the result of the detectable broadcast protocol 3. Works any time the adversary has a known least-favorite outcome 4. Works for t<n

Conclusion o Rational adversaries do allow improved results on BA/broadcast. o For many adversary preferences, we have matching possibility and impossibility results. o More complicated adversary preferences remain to be analyzed.

- Slides: 36