Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ACGME and

- Slides: 69

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education “ACGME, and the Responsibilities of America’s Medical Educators” Thomas J. Nasca MD MACP Chief Executive Officer Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Professor of Medicine (vol. ) Jefferson Medical College

Disclosure • No conflicts of interest to report • The ACGME receives no funds from any corporate entity other than accreditation fees related to ACGME accreditation services • The Journal of Graduate Medical Education permits no commercial advertizing • The ACGME Annual Educational Conference is entirely self sufficient • ACGME International is a Not-for-Profit entity

What are the most important philosophical or core stresses on this phase of the continuum? • The “Fraying” of the Social Contract between the Profession and the Public • The absence of a formal interface between the Profession and the Public • The Evolution (devolution) of the Educational Environment for Graduate Medical Education • Managing the Transition from Circumstantial Practice to Intentional Practice in Graduate Medical Education

I. Fraying of the Social Contract between the Profession and Society

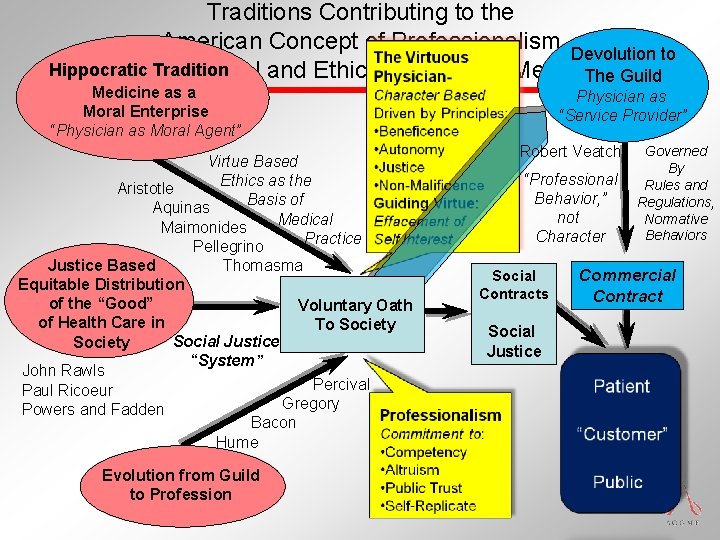

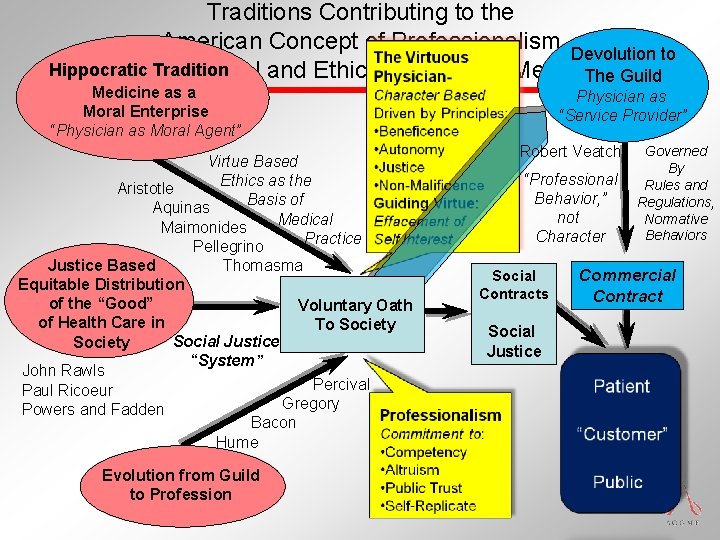

Traditions Contributing to the American Concept of Professionalism Devolution to Hippocratic and. Tradition the Moral and Ethical Practice of Medicine The Guild Medicine as a Moral Enterprise “Physician as Moral Agent” Virtue Based Ethics as the Aristotle Basis of Aquinas Medical Maimonides Practice Pellegrino Justice Based Thomasma Equitable Distribution of the “Good” Voluntary Oath of Health Care in To Society Social Justice Society “System” John Rawls Percival Paul Ricoeur Gregory Powers and Fadden Bacon Hume Evolution from Guild to Profession Physician as “Service Provider” Robert Veatch “Professional Behavior, ” not Character Social Contracts Social Justice Governed By Rules and Regulations, Normative Behaviors Commercial Contract

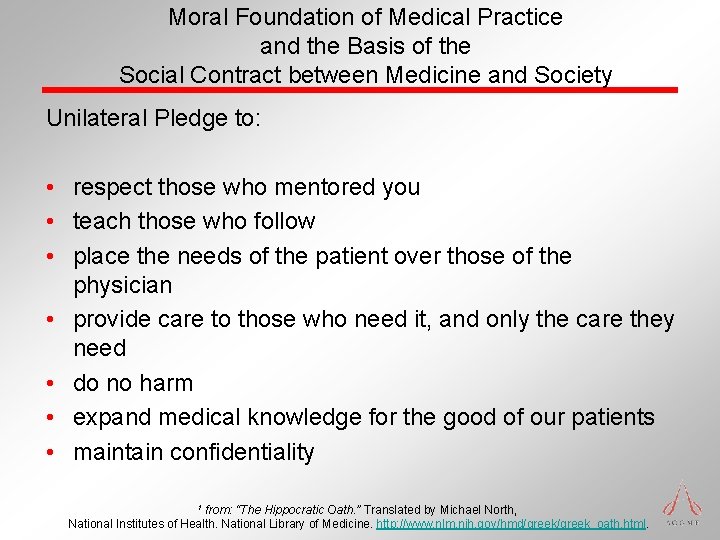

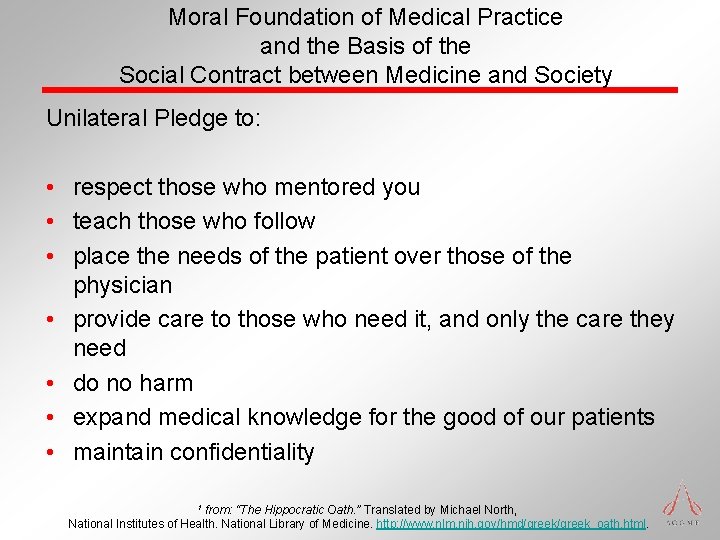

Moral Foundation of Medical Practice and the Basis of the Social Contract between Medicine and Society Unilateral Pledge to: • respect those who mentored you • teach those who follow • place the needs of the patient over those of the physician • provide care to those who need it, and only the care they need • do no harm • expand medical knowledge for the good of our patients • maintain confidentiality from: “The Hippocratic Oath. ” Translated by Michael North, National Institutes of Health. National Library of Medicine. http: //www. nlm. nih. gov/hmd/greek_oath. html. 1

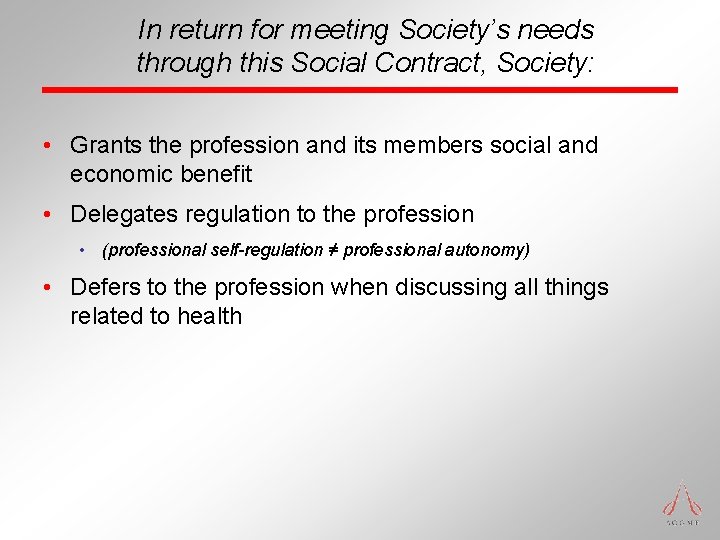

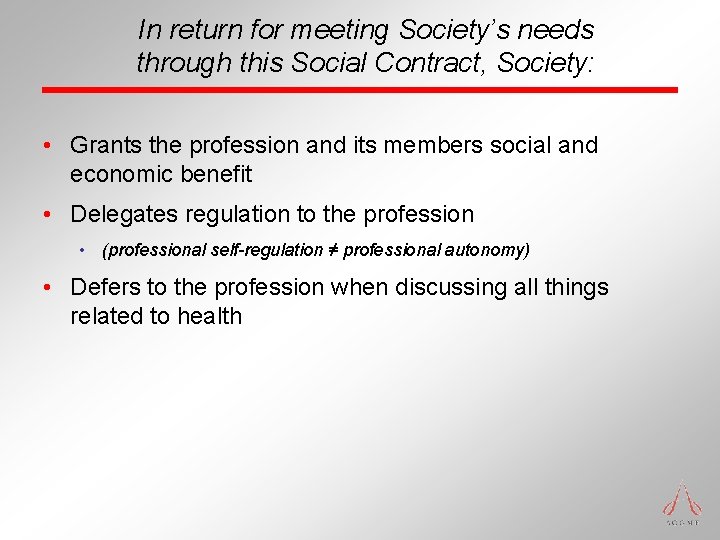

In return for meeting Society’s needs through this Social Contract, Society: • Grants the profession and its members social and economic benefit • Delegates regulation to the profession • (professional self-regulation ≠ professional autonomy) • Defers to the profession when discussing all things related to health

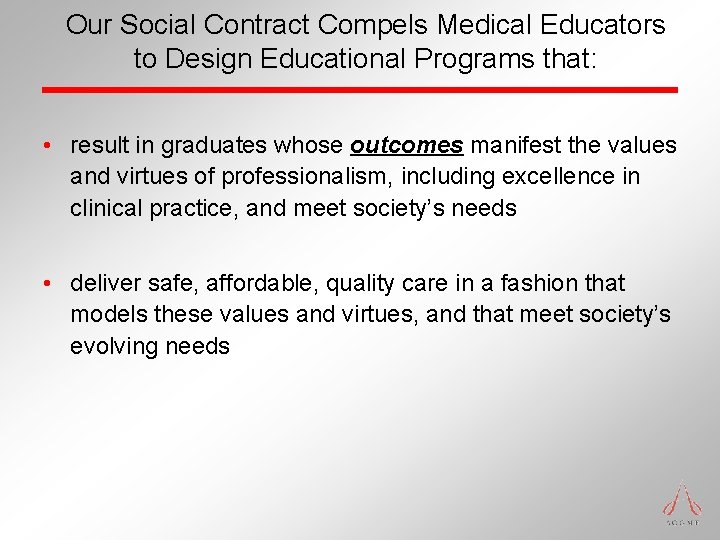

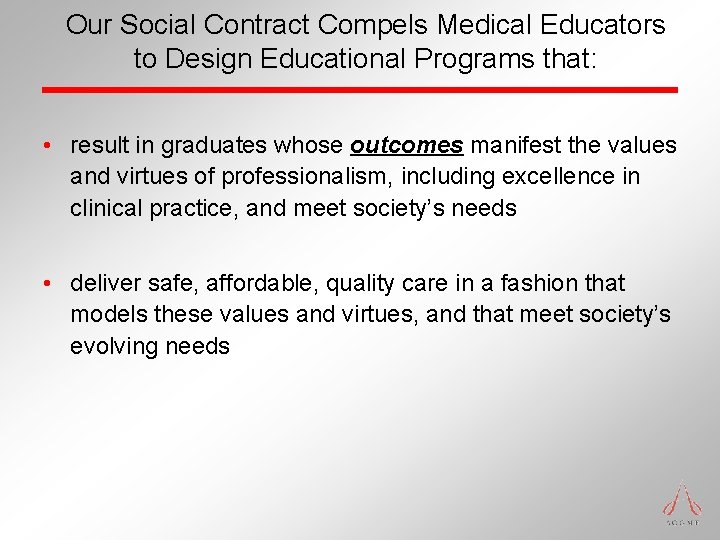

Our Social Contract Compels Medical Educators to Design Educational Programs that: • result in graduates whose outcomes manifest the values and virtues of professionalism, including excellence in clinical practice, and meet society’s needs • deliver safe, affordable, quality care in a fashion that models these values and virtues, and that meet society’s evolving needs

This Framework Compels us as Medical Educators: • To model these values and virtues in our own everyday activities (the informal curriculum) • To have the courage to advocate for the needs of all our patients • To have the courage to advocate for the needs of our residents

How does the Public Self-Identify its Needs and make them Known to the Profession? • No formal mechanism in the United States • “Payment Policy” has been used to “mold” physician behaviors • Essential that Medicine’s formal “Professional Accountability Organizations 1” develop formal interchange with the public • Within the organization – governance • Between the organization and the public – forum • With the formal leaders of the public – government 1 Professional Accountability Organizations = Testing, Accrediting, Certifying entities. Testing: AAMC, NBME. Accrediting: LCME, ACGME, ACCME. Certifying: ECFMG, ABMS Boards

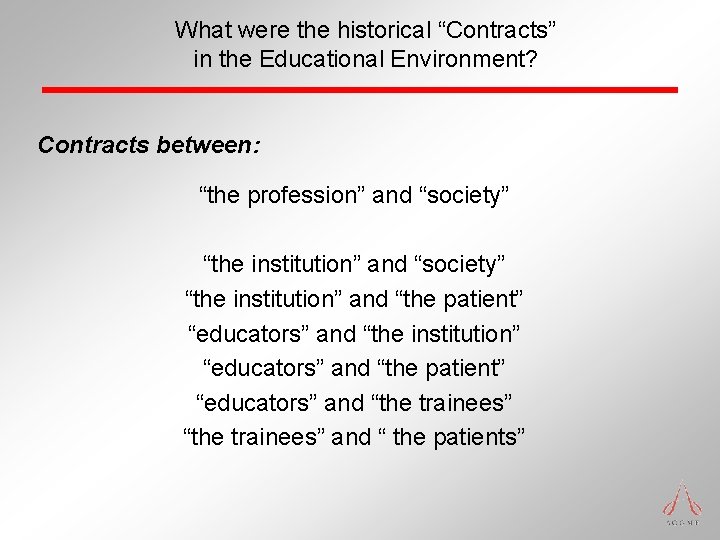

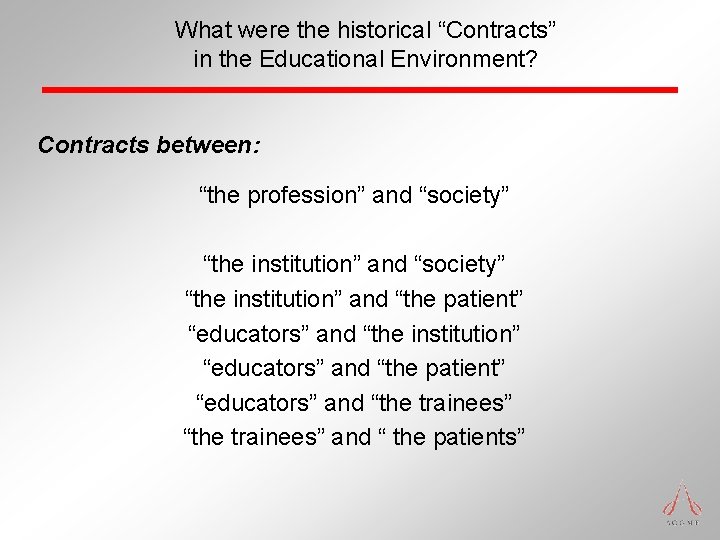

The Derivative Social Contracts

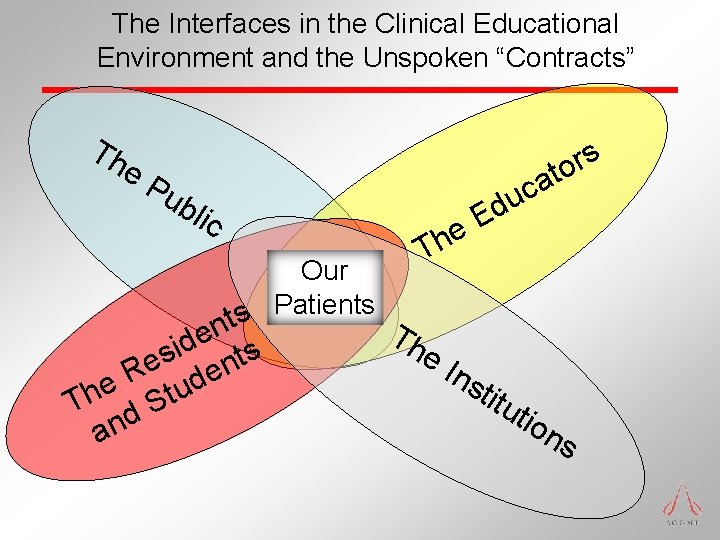

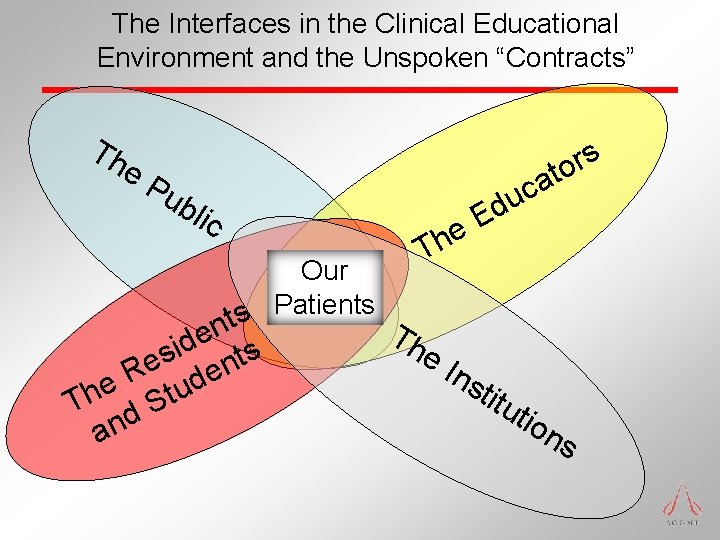

The Interfaces in the Clinical Educational Environment and the Unspoken “Contracts” Th e. P ub lic e h T Our Patients s t n T e he d i s s t e n R de e Th d Stu an c u Ed Ins titu s r o at tio ns

What were the historical “Contracts” in the Educational Environment? Contracts between: “the profession” and “society” “the institution” and “the patient” “educators” and “the institution” “educators” and “the patient” “educators” and “the trainees” and “ the patients”

II. The Evolution (Devolution) of the Traditional Model of our Graduate Medical Education Environment

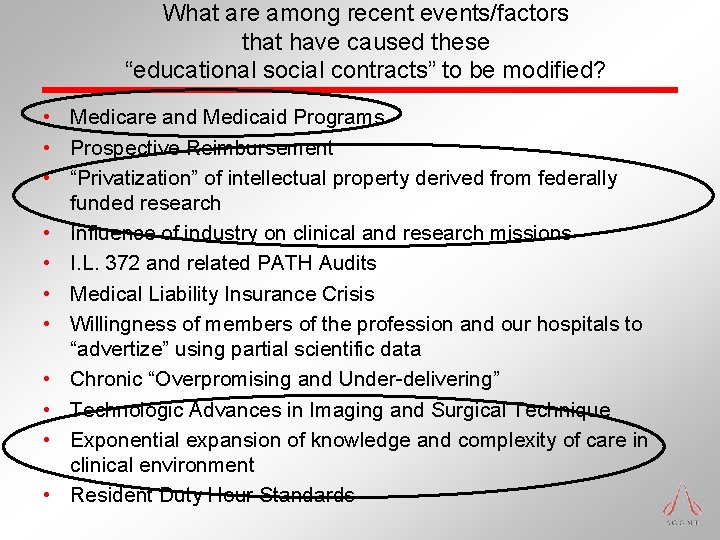

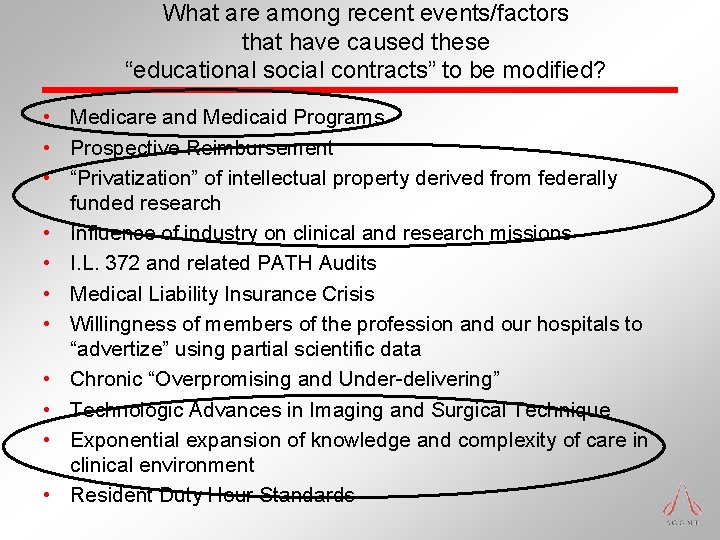

What are among recent events/factors that have caused these “educational social contracts” to be modified? • Medicare and Medicaid Programs • Prospective Reimbursement • “Privatization” of intellectual property derived from federally funded research • Influence of industry on clinical and research missions • I. L. 372 and related PATH Audits • Medical Liability Insurance Crisis • Willingness of members of the profession and our hospitals to “advertize” using partial scientific data • Chronic “Overpromising and Under-delivering” • Technologic Advances in Imaging and Surgical Technique • Exponential expansion of knowledge and complexity of care in clinical environment • Resident Duty Hour Standards

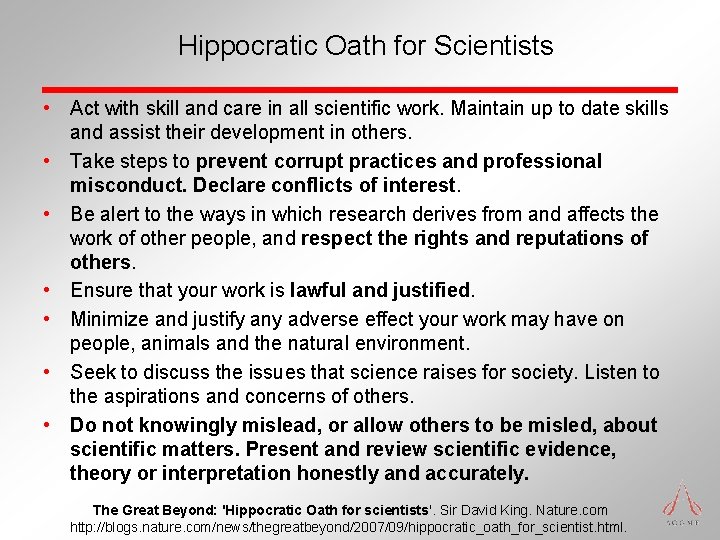

Hippocratic Oath for Scientists • Act with skill and care in all scientific work. Maintain up to date skills and assist their development in others. • Take steps to prevent corrupt practices and professional misconduct. Declare conflicts of interest. • Be alert to the ways in which research derives from and affects the work of other people, and respect the rights and reputations of others. • Ensure that your work is lawful and justified. • Minimize and justify any adverse effect your work may have on people, animals and the natural environment. • Seek to discuss the issues that science raises for society. Listen to the aspirations and concerns of others. • Do not knowingly mislead, or allow others to be misled, about scientific matters. Present and review scientific evidence, theory or interpretation honestly and accurately. The Great Beyond: 'Hippocratic Oath for scientists'. Sir David King. Nature. com http: //blogs. nature. com/news/thegreatbeyond/2007/09/hippocratic_oath_for_scientist. html.

What are among recent events/factors that have caused these “educational social contracts” to be modified? Changing expectations of the American Public: • • • Expectations of translation of scientific advances Impact/influence of “To Err is Human” Zero tolerance for error Work Hours of Physicians Movement towards a consumer – vendor relationship with “providers” for “medicalized” services (the Guild) • Devaluation of “value” of “Primary Care” • Erosion of trust in “trusted agents”

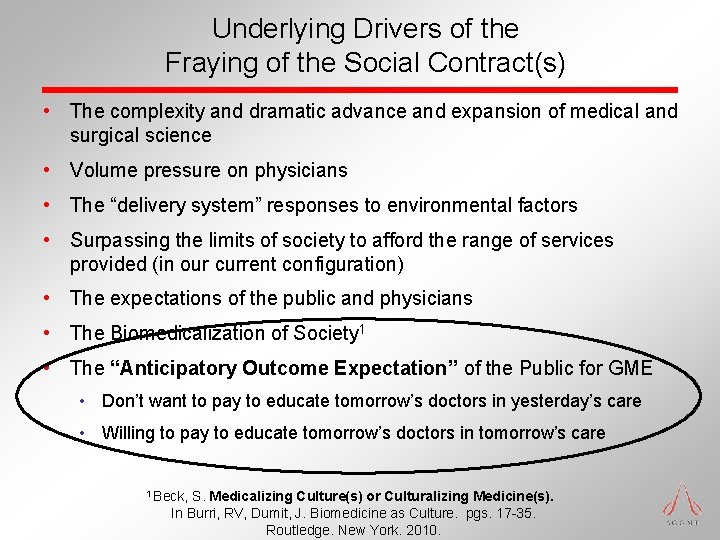

Underlying Drivers of the Fraying of the Social Contract(s) • The complexity and dramatic advance and expansion of medical and surgical science • Volume pressure on physicians • The “delivery system” responses to environmental factors • Surpassing the limits of society to afford the range of services provided (in our current configuration) • The expectations of the public and physicians • The Biomedicalization of Society 1 • The “Anticipatory Outcome Expectation” of the Public for GME • Don’t want to pay to educate tomorrow’s doctors in yesterday’s care • Willing to pay to educate tomorrow’s doctors in tomorrow’s care 1 Beck, S. Medicalizing Culture(s) or Culturalizing Medicine(s). In Burri, RV, Dumit, J. Biomedicine as Culture. pgs. 17 -35. Routledge. New York. 2010.

III. What are key trends/factors in our environment?

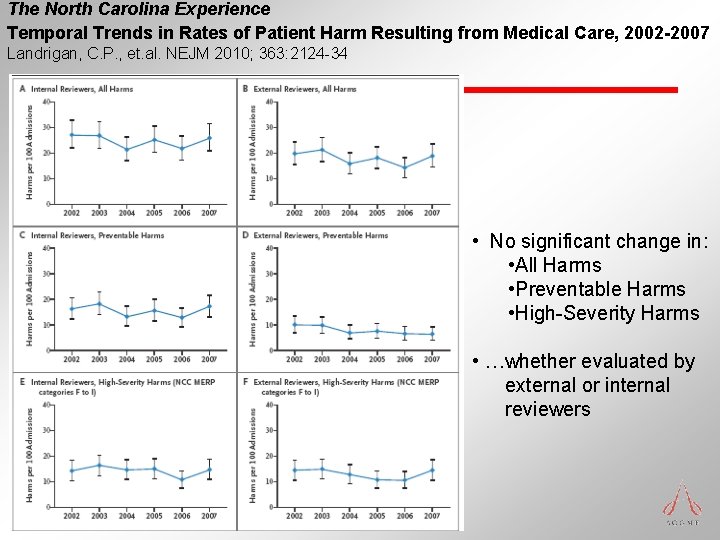

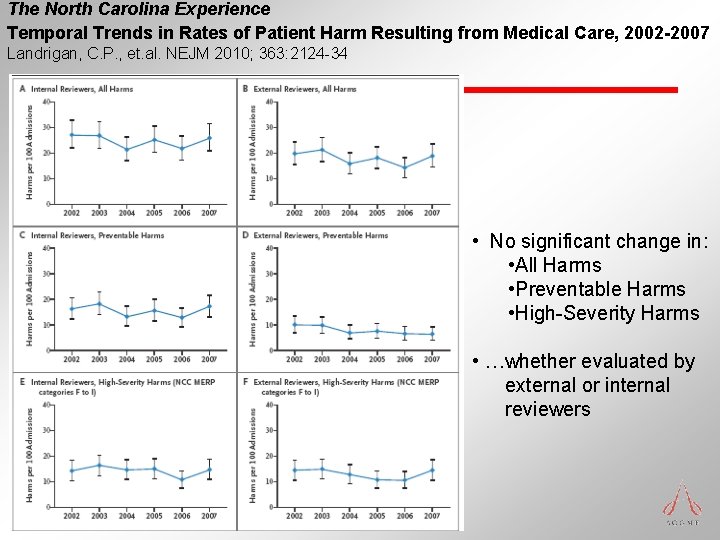

The North Carolina Experience Temporal Trends in Rates of Patient Harm Resulting from Medical Care, 2002 -2007 Landrigan, C. P. , et. al. NEJM 2010; 363: 2124 -34 • No significant change in: • All Harms • Preventable Harms • High-Severity Harms • …whether evaluated by external or internal reviewers

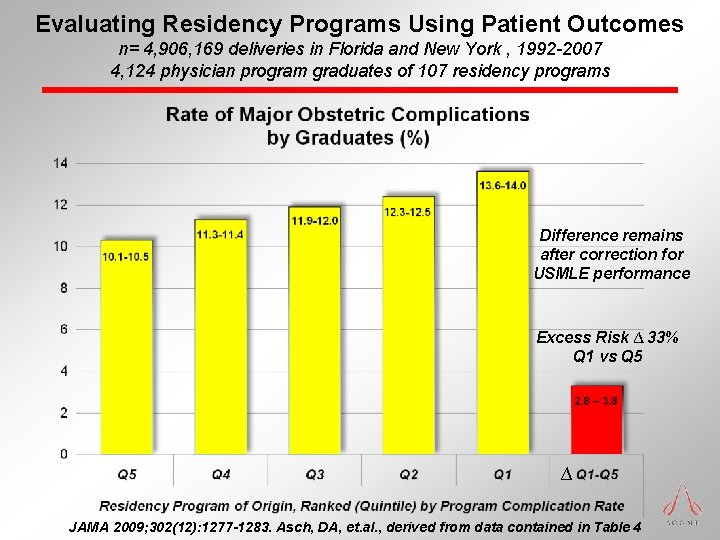

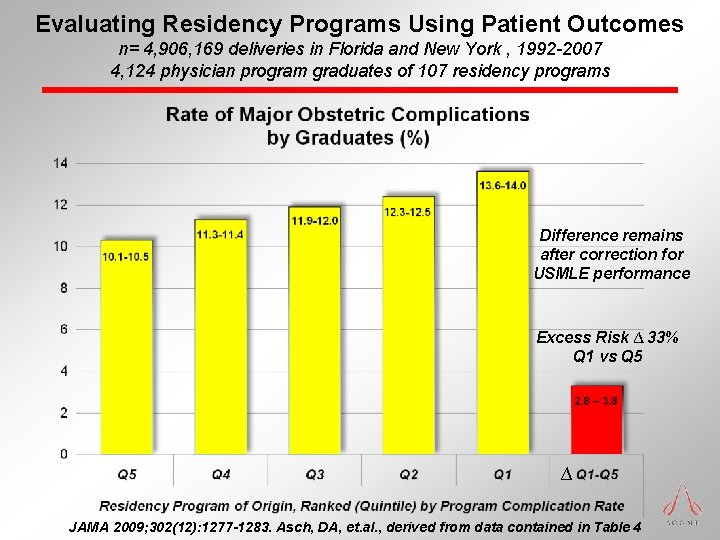

Evaluating Residency Programs Using Patient Outcomes n= 4, 906, 169 deliveries in Florida and New York , 1992 -2007 4, 124 physician program graduates of 107 residency programs Difference remains after correction for USMLE performance Excess Risk ∆ 33% Q 1 vs Q 5 ∆ JAMA 2009; 302(12): 1277 -1283. Asch, DA, et. al. , derived from data contained in Table 4

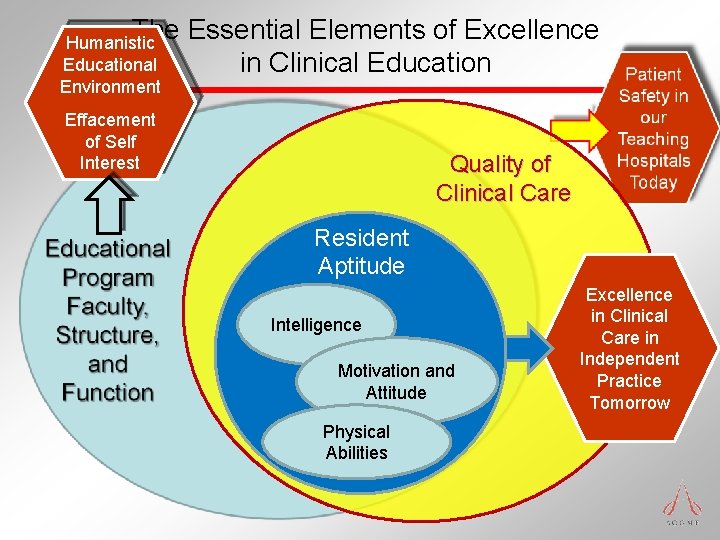

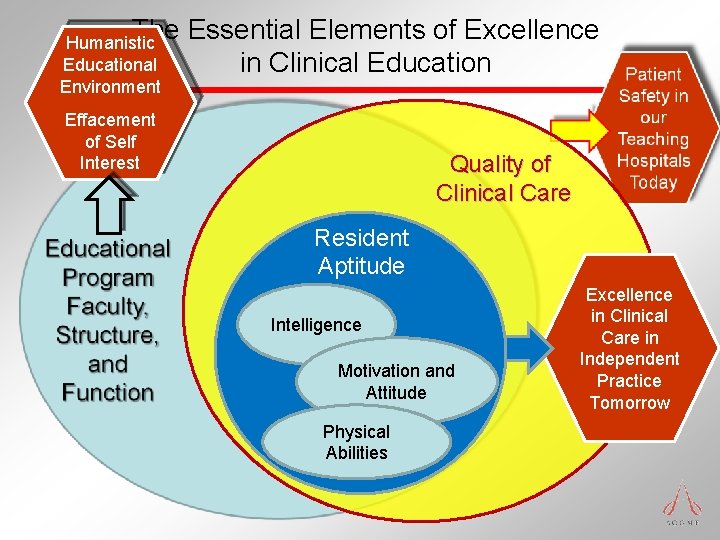

The Essential Elements of Excellence in Clinical Education Humanistic Educational Environment Effacement of Self Interest Quality of Clinical Care Resident Aptitude Intelligence Motivation and Attitude Physical Abilities Excellence in Clinical Care in Independent Practice Tomorrow

IV. Managing the Transition from Circumstantial Practice to Intentional Practice in Graduate Medical Education

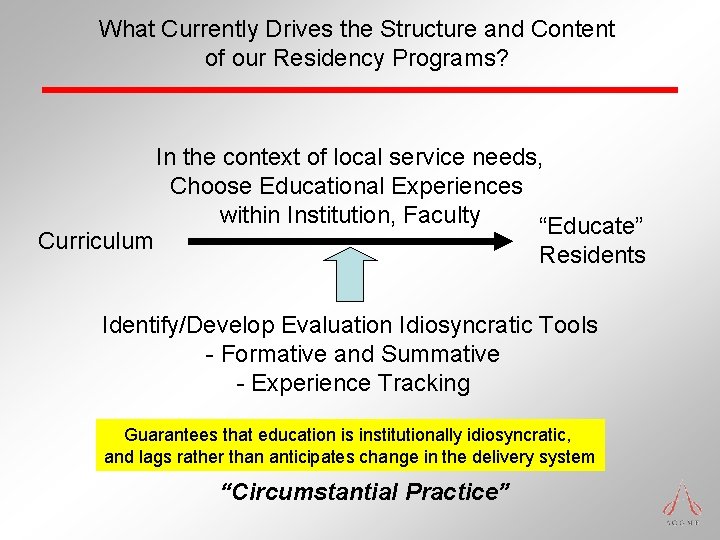

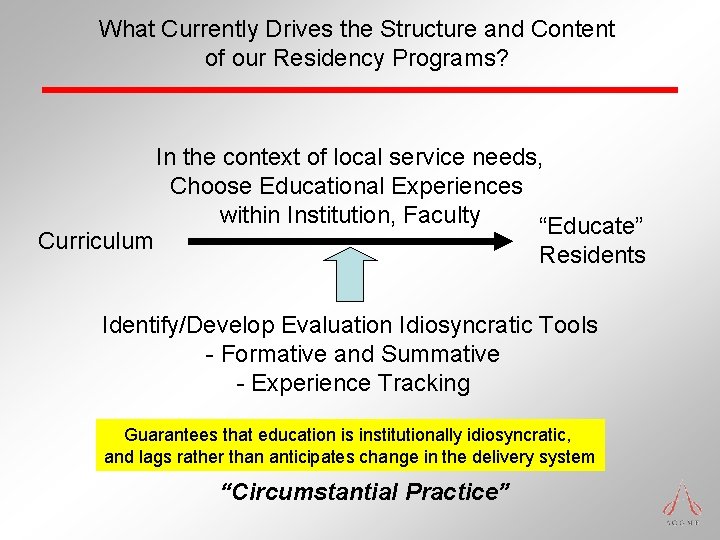

What Currently Drives the Structure and Content of our Residency Programs? Curriculum In the context of local service needs, Choose Educational Experiences within Institution, Faculty “Educate” Residents Identify/Develop Evaluation Idiosyncratic Tools - Formative and Summative - Experience Tracking Guarantees that education is institutionally idiosyncratic, and lags rather than anticipates change in the delivery system “Circumstantial Practice”

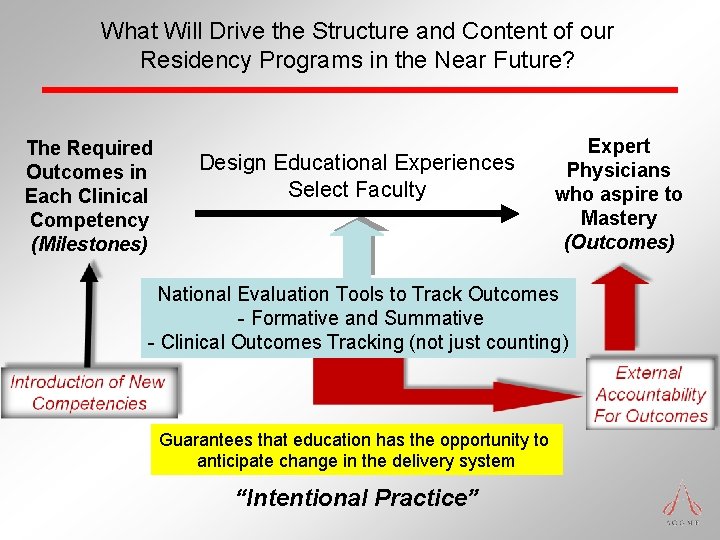

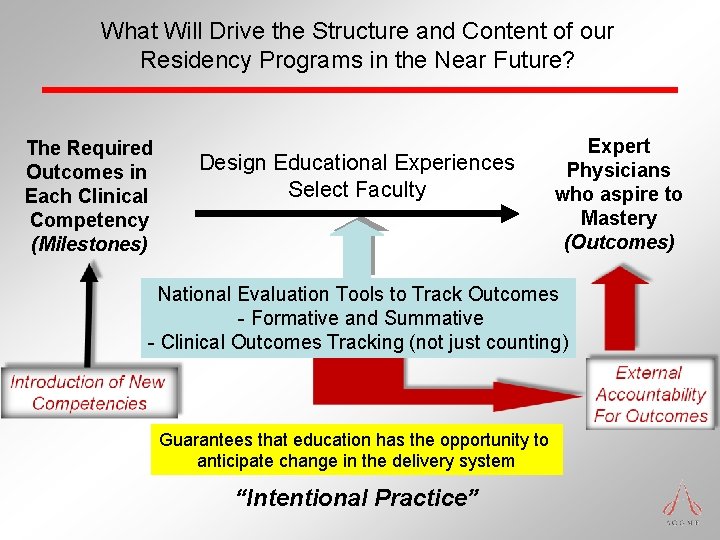

What Will Drive the Structure and Content of our Residency Programs in the Near Future? The Required Outcomes in Each Clinical Competency (Milestones) Design Educational Experiences Select Faculty Expert Physicians who aspire to Mastery (Outcomes) National Evaluation Tools to Track Outcomes - Formative and Summative - Clinical Outcomes Tracking (not just counting) Guarantees that education has the opportunity to anticipate change in the delivery system “Intentional Practice”

IV. Integration, and the Role of the ACGME

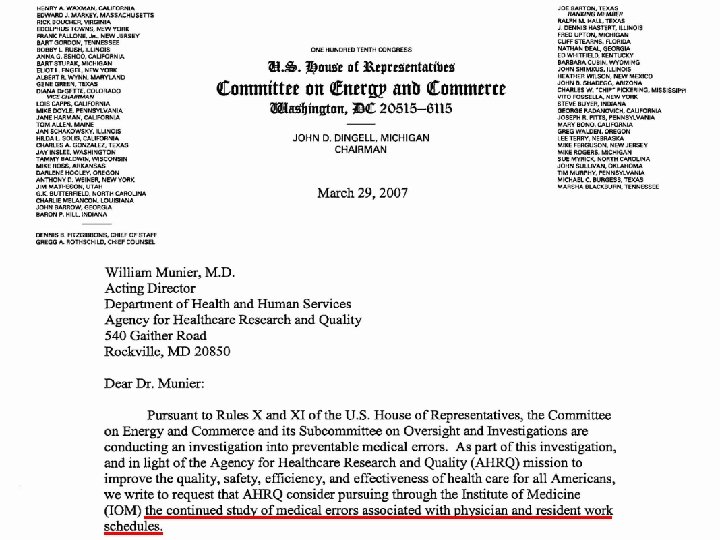

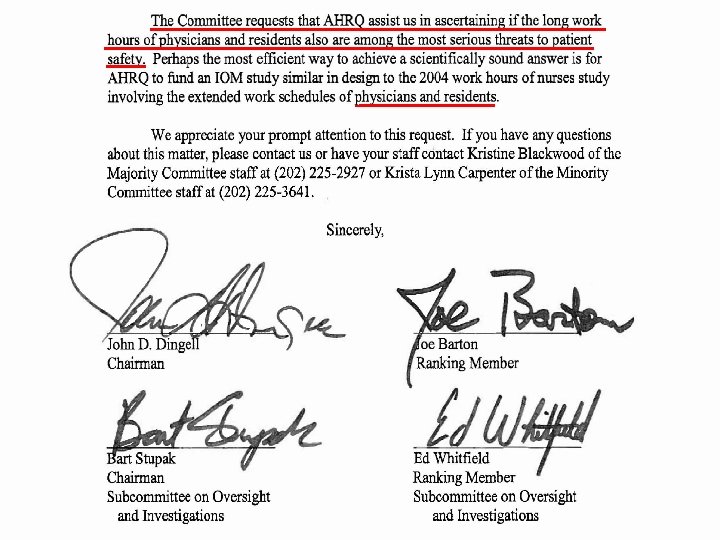

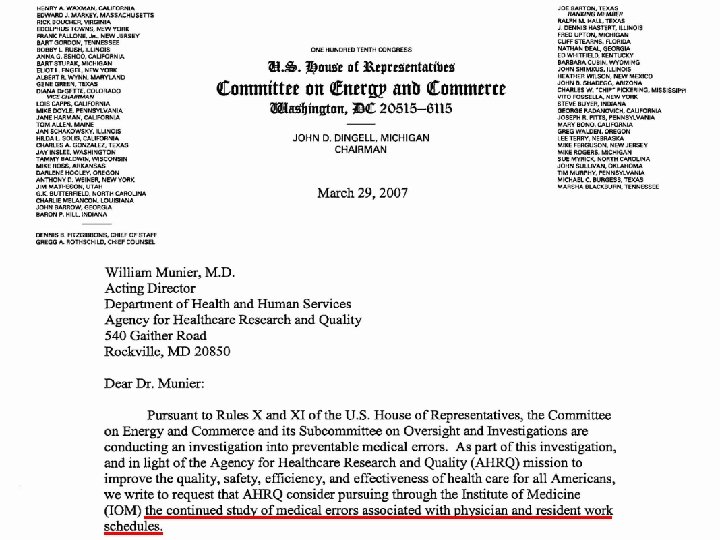

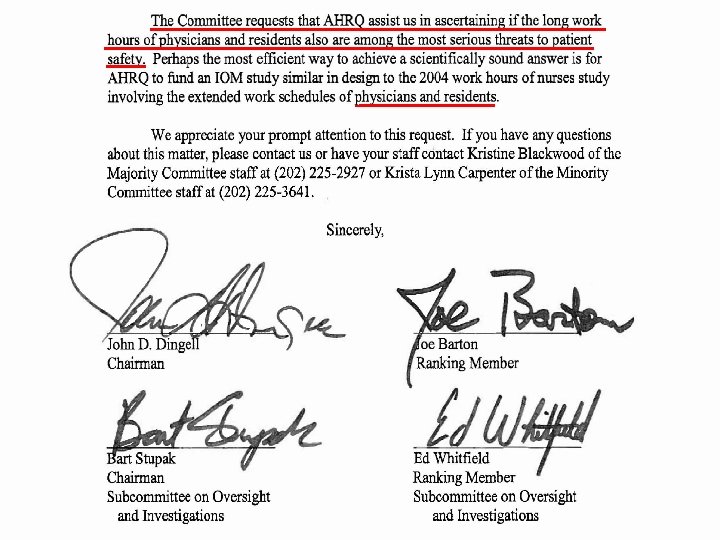

The “Public’s” Call for “ACGME Action” The Short List… • • • • Institute of Medicine –To Err is Human, 1999 Institute of Medicine – Crossing the Quality Chasm, 2001 Congressional introduction of resident duty hour regulation legislation, 2003 Institute of Medicine – Resident Duty Hours, 2008, precipitated by Letter from Congress 2007 Congress, House of Representatives Codification of Physician Competencies in Law (Health Care Reform, Section 1505) 2009 Institute of Medicine – Conflicts of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice, 2009 Public Citizen OSHA Petition, 2010 OSHA remarks by Dr. Michaels related to Public Citizen Petition, 2010, 2011 Med. PAC Report, June 2010 Council on Graduate Medical Education (numerous reports, Twentieth Report, Advancing Primary Care, 2010) National Patient Safety Forum, 2010 Carnegie Foundation Report – “Flexner 2”, 2010 Macy Foundation – Draft Report, January 2011 National Coordinator for Health Information Technology – February 2011 Numerous New England Journal Articles Numerous Lay Press Articles

The Public’s Call for ACGME Action Why us? • You don’t make practicing physicians in medical school • Residents care for real patients • The tools learned in residency influence future care • Nearly $9. 4 billion per year to America’s Teaching Hospitals • Trusted agent, required for: • Licensure • Board Certification • Institutional payment for GME • Worldwide reputation for quality, high standards, innovation in accreditation • Has been the focal point for change leading to positive action

V. What Needs to be Done? “Half Empty” “Half Full”

Call to Affirmative Action In order to meet society’s needs for quality care, patient safety, and physicians prepared to provide care in “ 2020 and beyond, ” the academic community must: • Reconfigure care to meet society’s needs – NOW! • Educate faculty and tomorrows physicians to disseminate that new model – NOW! • Continuously earn the right to self regulate the profession

How will the ACGME help accomplish this mission? • Milestones • The Next Accreditation System • Develop effective relationships with “the Public” to ascertain their needs

“Faced with the choice between changing one's mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everybody gets busy on the proof. ” John Kenneth Galbraith American Economist

“Somebody has to do something, and it’s just incredibly pathetic that it has to be us. ” Jerry Garcia The Grateful Dead

Optimism “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny matters compared to what lies within us. ” Oliver Wendell Holmes

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Thank You

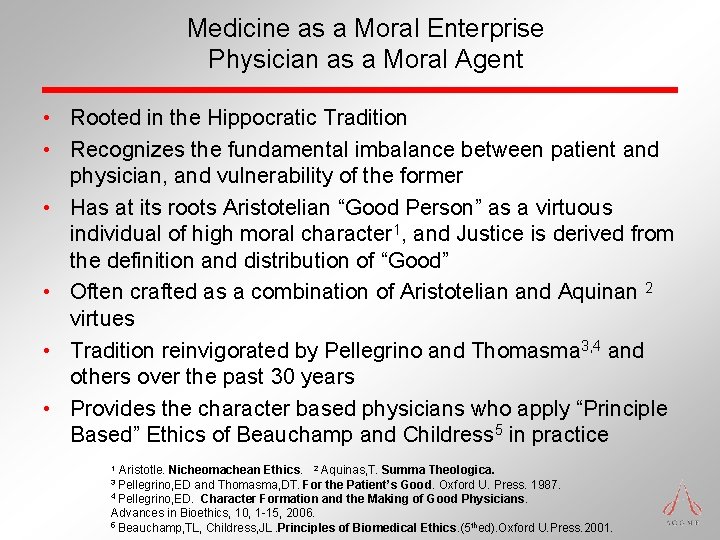

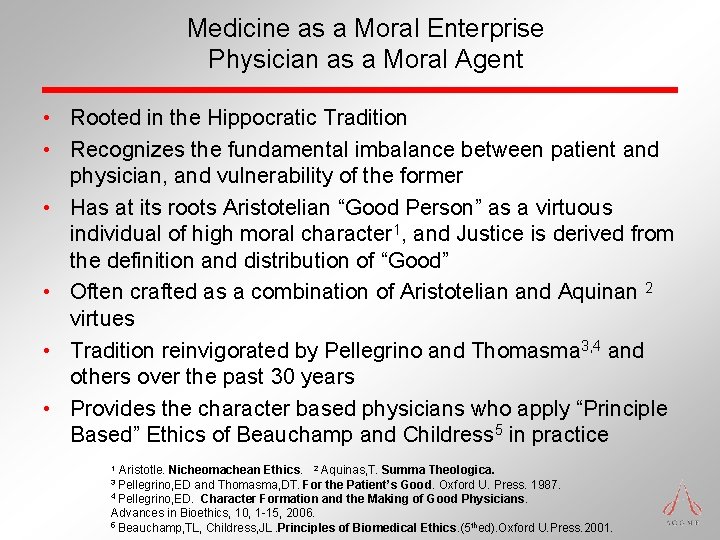

Medicine as a Moral Enterprise Physician as a Moral Agent • Rooted in the Hippocratic Tradition • Recognizes the fundamental imbalance between patient and physician, and vulnerability of the former • Has at its roots Aristotelian “Good Person” as a virtuous individual of high moral character 1, and Justice is derived from the definition and distribution of “Good” • Often crafted as a combination of Aristotelian and Aquinan 2 virtues • Tradition reinvigorated by Pellegrino and Thomasma 3, 4 and others over the past 30 years • Provides the character based physicians who apply “Principle Based” Ethics of Beauchamp and Childress 5 in practice Aristotle. Nicheomachean Ethics. 2 Aquinas, T. Summa Theologica. 3 Pellegrino, ED and Thomasma, DT. For the Patient’s Good. Oxford U. Press. 1987. 4 Pellegrino, ED. Character Formation and the Making of Good Physicians. Advances in Bioethics, 10, 1 -15, 2006. 5 Beauchamp, TL, Childress, JL. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. (5 thed). Oxford U. Press. 2001. 1

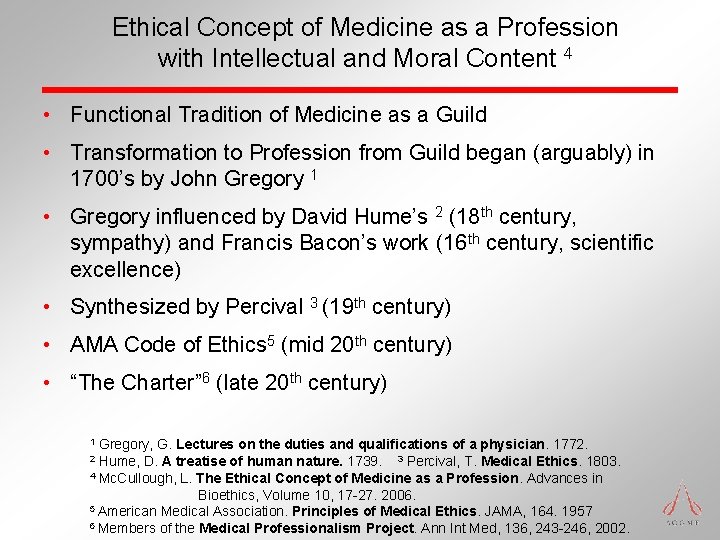

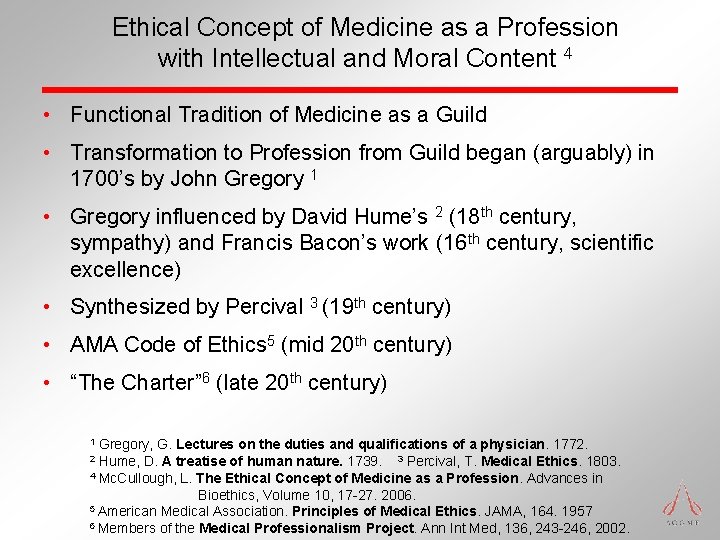

Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession with Intellectual and Moral Content 4 • Functional Tradition of Medicine as a Guild • Transformation to Profession from Guild began (arguably) in 1700’s by John Gregory 1 • Gregory influenced by David Hume’s 2 (18 th century, sympathy) and Francis Bacon’s work (16 th century, scientific excellence) • Synthesized by Percival 3 (19 th century) • AMA Code of Ethics 5 (mid 20 th century) • “The Charter” 6 (late 20 th century) Gregory, G. Lectures on the duties and qualifications of a physician. 1772. Hume, D. A treatise of human nature. 1739. 3 Percival, T. Medical Ethics. 1803. 4 Mc. Cullough, L. The Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession. Advances in Bioethics, Volume 10, 17 -27. 2006. 5 American Medical Association. Principles of Medical Ethics. JAMA, 164. 1957 6 Members of the Medical Professionalism Project. Ann Int Med, 136, 243 -246, 2002. 1 2

• Veatch, R. M. Character Formation in Professional Education: A Word of Caution. In Lost Virtue: Professional Character in Medical Education. Advances in Bioethics, Vol. 10, 29 -45. 2006. Elsevier, Ltd. Oxford, England.

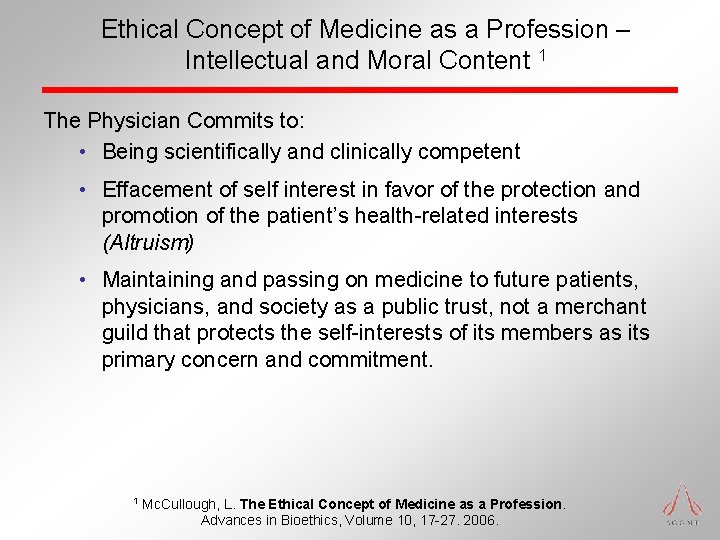

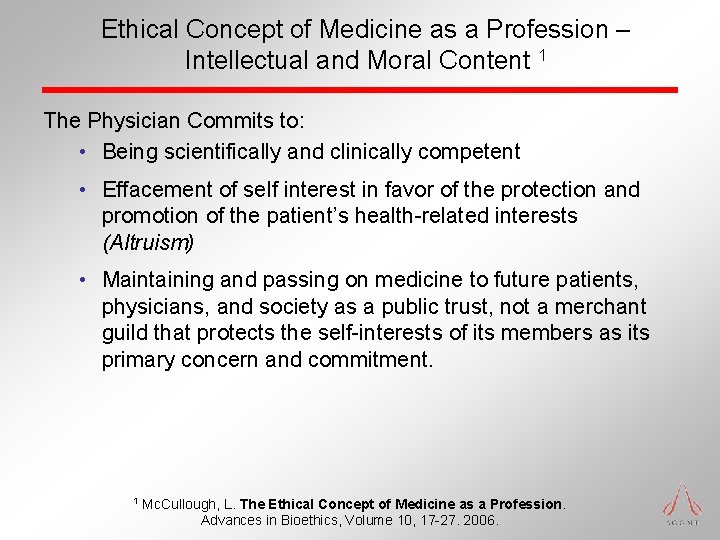

Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession – Intellectual and Moral Content 1 The Physician Commits to: • Being scientifically and clinically competent • Effacement of self interest in favor of the protection and promotion of the patient’s health-related interests (Altruism) • Maintaining and passing on medicine to future patients, physicians, and society as a public trust, not a merchant guild that protects the self-interests of its members as its primary concern and commitment. 1 Mc. Cullough, L. The Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession. Advances in Bioethics, Volume 10, 17 -27. 2006.

The Legacy of Graduate Medical Education Oversight in the United States • The ACGME has evolved over nearly 60 years from: • independent individual specialty review committees (1940’s) • through a Council housed within the AMA (1980) • to an independent, 501, (c), (3) corporation (2000) • Public, At Large, Resident VA and HHS members added (20002009) • Mission is the advancement of health through enhancement in GME • The authority of the RC’s is delegated by the ACGME Board • The ACGME Board is responsible to the public for the work of each of its committees

What is common or underlying these calls? • “They” alternately recognize the ACGME as: • the agent of change/improvement, or • the blocker of change/improvement • “They” Expect: • the “GME Community” to respond to the needs of the Public • much more from the ACGME than traditional educational accreditors • more rapid change and improvement • the ACGME to drive change, yet simultaneously promote innovation • the “ACGME” to be accountable for the outcomes of GME • the “ACGME” to act in a coordinated fashion • expect the RC’s to implement the directions that the “ACGME” sets

The ACGME must fulfill the social contract, and must cause sponsors and programs to maintain an educational environment that assures: • the safety and quality of care of the patients under the care of residents today • the safety and quality of care of the patients under the care of our graduates in their future practice • the provision of a humanistic educational environment where residents are taught to manifest professionalism and effacement of self interest to meet the needs of their patients

We can Achieve the Desired Future State! • The graduates of GME programs: • demonstrate excellence in all dimensions of the six domains of clinical competency • demonstrate the elements identified by the IOM as well as the core skill sets in leadership, teamwork, information use, and other areas required to meet society’s needs • The teaching hospitals and health systems are viewed as: • highly effective in educating and producing the desired outcomes in the next generation of caregivers • leaders in patient safety, quality improvement, and cost efficiency • responsive to the evolving educational and clinical needs as articulated by society

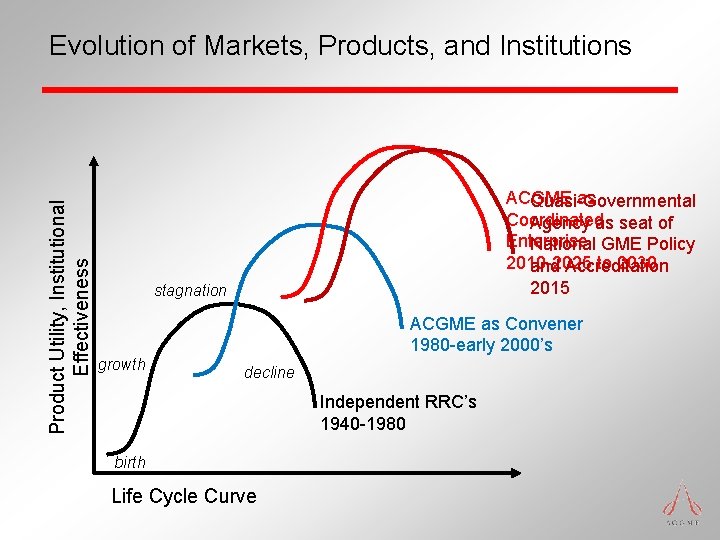

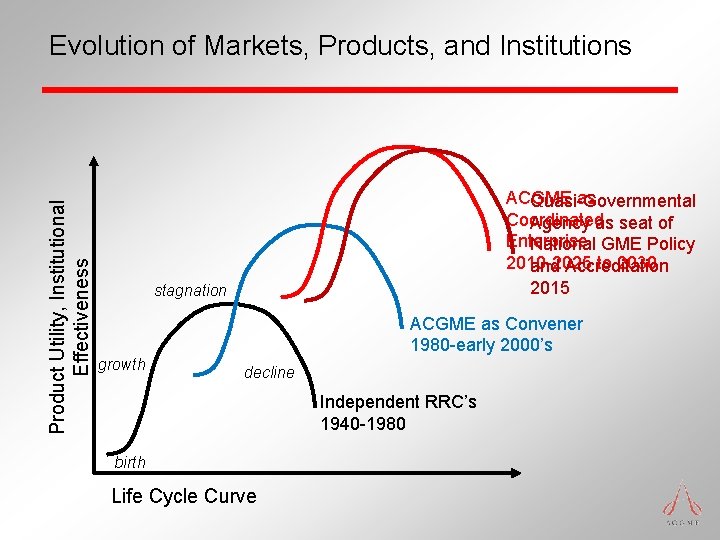

Product Utility, Institutional Effectiveness Evolution of Markets, Products, and Institutions ACGME as Quasi-Governmental Coordinated Agency as seat of Enterprise National GME Policy 2010 -2025 to 2030 and Accreditation 2015 stagnation ACGME as Convener 1980 -early 2000’s growth decline Independent RRC’s 1940 -1980 birth Life Cycle Curve

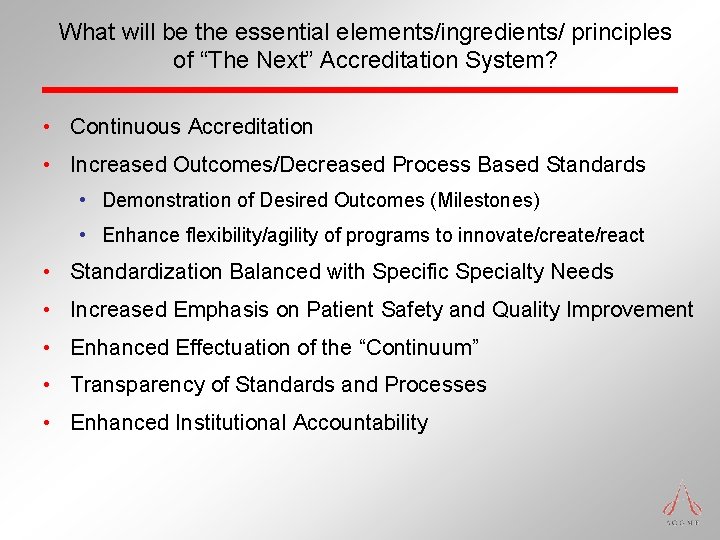

What will be the essential elements/ingredients/ principles of “The Next” Accreditation System? • Continuous Accreditation • Increased Outcomes/Decreased Process Based Standards • Demonstration of Desired Outcomes (Milestones) • Enhance flexibility/agility of programs to innovate/create/react • Standardization Balanced with Specific Specialty Needs • Increased Emphasis on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement • Enhanced Effectuation of the “Continuum” • Transparency of Standards and Processes • Enhanced Institutional Accountability

When will this happen? • ACGME Board of Directors charged administration to present in June, 2011: • Proposal for development and implementation of “The Next Accreditation System” • Process for development – Engagement of RC’s, Member Organizations, Medical Organizations, PD’s, Public – Team to develop – Time course for development, approval, implementation • Business plan for development and implementation

Medicine as a Moral Enterprise Physician as a Moral Agent • Rooted in the Hippocratic Tradition • Recognizes the fundamental imbalance between patient and physician, and vulnerability of the former • Has at its roots Aristotelian “Good Person” as a virtuous individual of high moral character 1, and Justice is derived from the definition and distribution of “Good” • Often crafted as a combination of Aristotelian and Aquinan 2 virtues • Tradition reinvigorated by Pellegrino and Thomasma 3, 4 and others over the past 30 years • Provides the character based physicians who apply “Principle Based” Ethics of Beauchamp and Childress 5 in practice Aristotle. Nicheomachean Ethics. 2 Aquinas, T. Summa Theologica. 3 Pellegrino, ED and Thomasma, DT. For the Patient’s Good. Oxford U. Press. 1987. 4 Pellegrino, ED. Character Formation and the Making of Good Physicians. Advances in Bioethics, 10, 1 -15, 2006. 5 Beauchamp, TL, Childress, JL. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. (5 thed). Oxford U. Press. 2001. 1

Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession with Intellectual and Moral Content 4 • Functional Tradition of Medicine as a Guild • Transformation to Profession from Guild began (arguably) in 1700’s by John Gregory 1 • Gregory influenced by David Hume’s 2 (18 th century, sympathy) and Francis Bacon’s work (16 th century, scientific excellence) • Synthesized by Percival 3 (19 th century) • AMA Code of Ethics 5 (mid 20 th century) • “The Charter” 6 (late 20 th century) Gregory, G. Lectures on the duties and qualifications of a physician. 1772. Hume, D. A treatise of human nature. 1739. 3 Percival, T. Medical Ethics. 1803. 4 Mc. Cullough, L. The Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession. Advances in Bioethics, Volume 10, 17 -27. 2006. 5 American Medical Association. Principles of Medical Ethics. JAMA, 164. 1957 6 Members of the Medical Professionalism Project. Ann Int Med, 136, 243 -246, 2002. 1 2

Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession – Intellectual and Moral Content 1 The Physician Commits to: • Being scientifically and clinically competent • Effacement of self interest in favor of the protection and promotion of the patient’s health-related interests (Altruism) • Maintaining and passing on medicine to future patients, physicians, and society as a public trust, not a merchant guild that protects the self-interests of its members as its primary concern and commitment. 1 Mc. Cullough, L. The Ethical Concept of Medicine as a Profession. Advances in Bioethics, Volume 10, 17 -27. 2006.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Resident Duty Hours

But they are not all pointing in the same direction on any one issue! IOM Sleep Researchers Some Advocacy Groups Unions Some Students, Residents The needs of the Public Lay Press ACGME ACTION Most in the Profession Most of the Educators Most Residents Hospital Administrators The needs of the Public

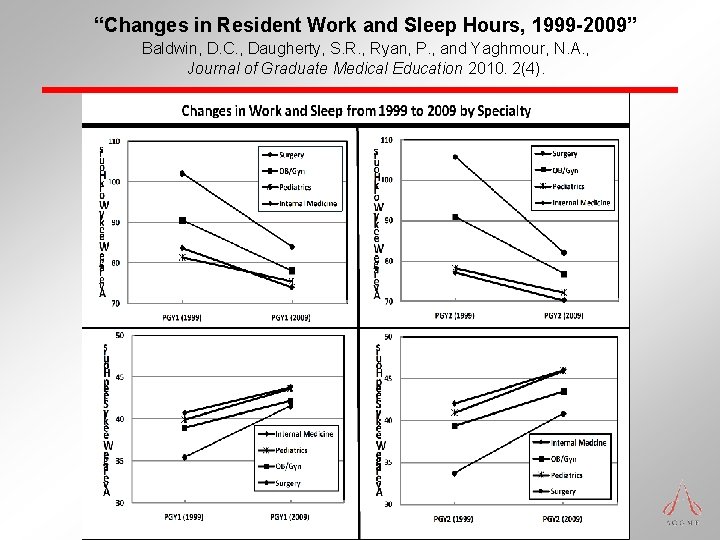

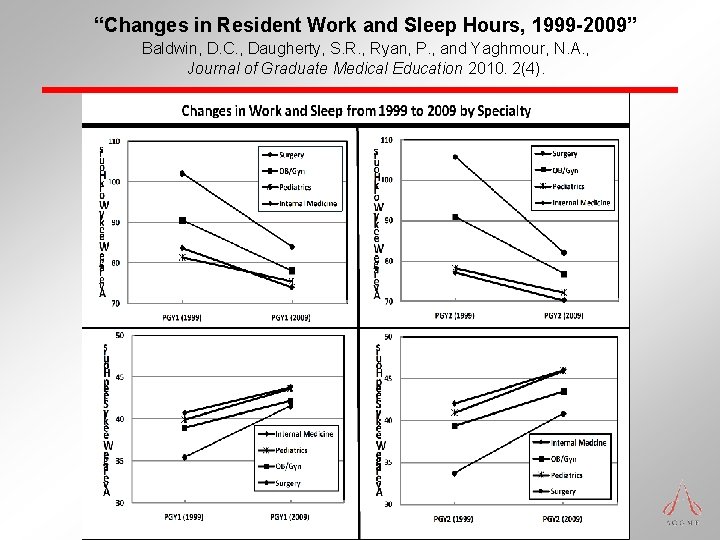

“Changes in Resident Work and Sleep Hours, 1999 -2009” Baldwin, D. C. , Daugherty, S. R. , Ryan, P. , and Yaghmour, N. A. , Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2010. 2(4).

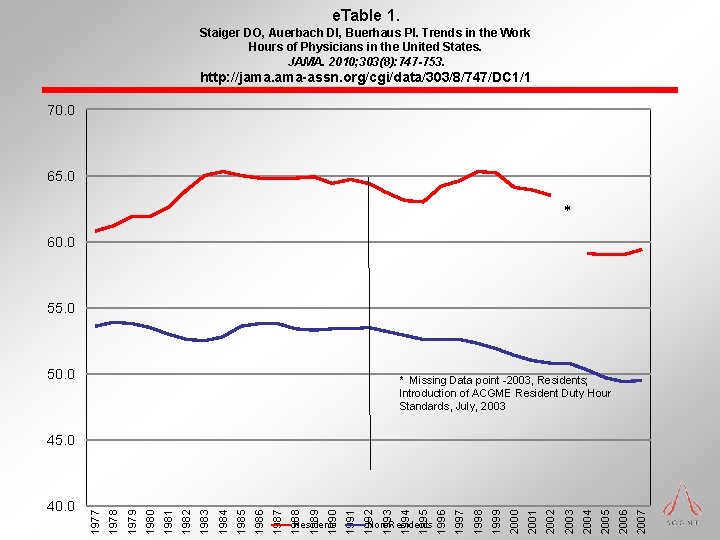

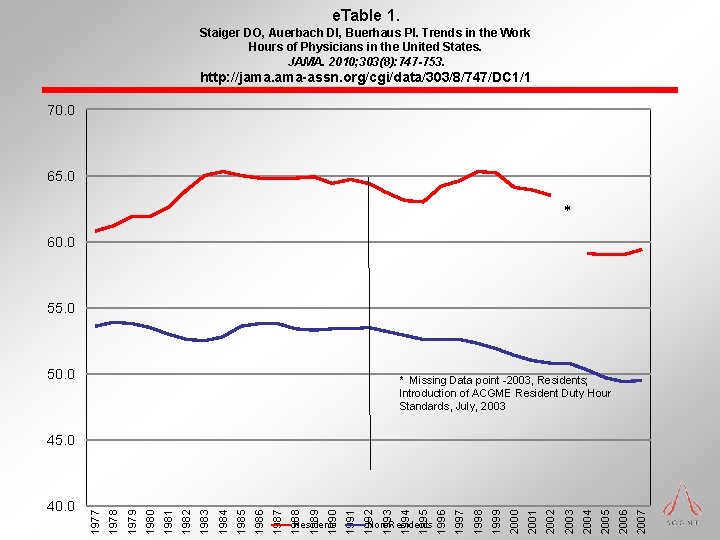

e. Table 1. Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Trends in the Work Hours of Physicians in the United States. JAMA. 2010; 303(8): 747 -753. http: //jama. ama-assn. org/cgi/data/303/8/747/DC 1/1 70. 0 65. 0 * 60. 0 55. 0 50. 0 * Missing Data point -2003, Residents; Introduction of ACGME Resident Duty Hour Standards, July, 2003 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 Non-Residents 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 Residents 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 1986 1985 1984 1983 1982 1981 1980 1979 1978 40. 0 1977 45. 0

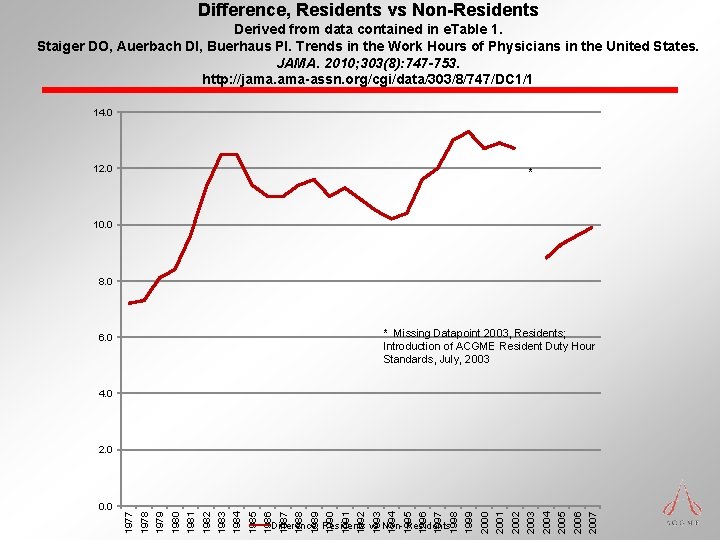

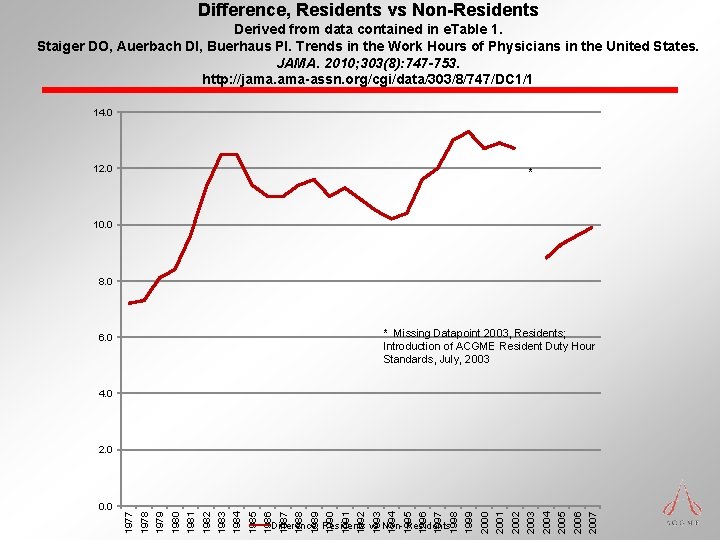

Difference, Residents vs Non-Residents Derived from data contained in e. Table 1. Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Trends in the Work Hours of Physicians in the United States. JAMA. 2010; 303(8): 747 -753. http: //jama. ama-assn. org/cgi/data/303/8/747/DC 1/1 14. 0 12. 0 * 10. 0 8. 0 * Missing Datapoint 2003, Residents; Introduction of ACGME Resident Duty Hour Standards, July, 2003 6. 0 4. 0 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 Difference, Residents vs Non- Residents 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 1986 1985 1984 1983 1982 1981 1980 1979 1978 0. 0 1977 2. 0

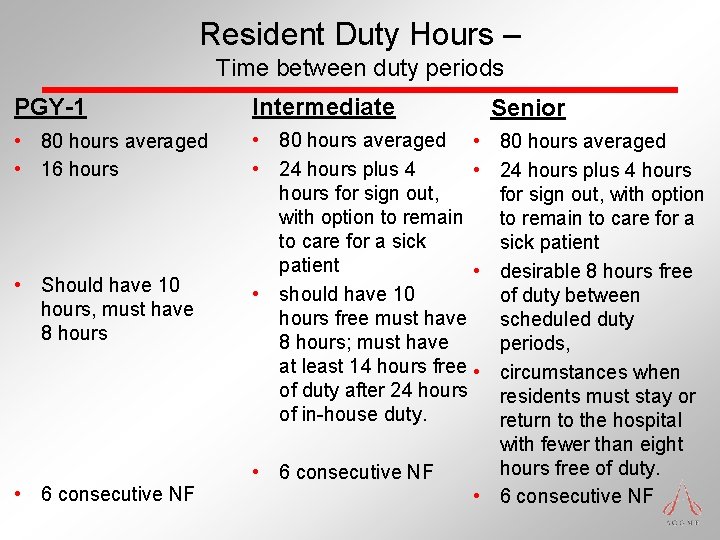

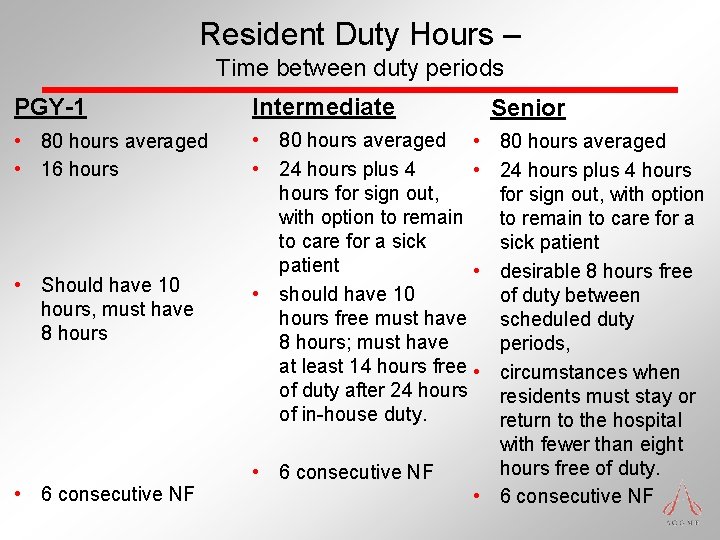

Resident Duty Hours – Time between duty periods PGY-1 Intermediate • 80 hours averaged • 16 hours • 80 hours averaged • • 24 hours plus 4 • hours for sign out, with option to remain to care for a sick patient • • should have 10 hours free must have 8 hours; must have at least 14 hours free • of duty after 24 hours of in-house duty. • Should have 10 hours, must have 8 hours • 6 consecutive NF Senior 80 hours averaged 24 hours plus 4 hours for sign out, with option to remain to care for a sick patient desirable 8 hours free of duty between scheduled duty periods, circumstances when residents must stay or return to the hospital with fewer than eight hours free of duty. • 6 consecutive NF

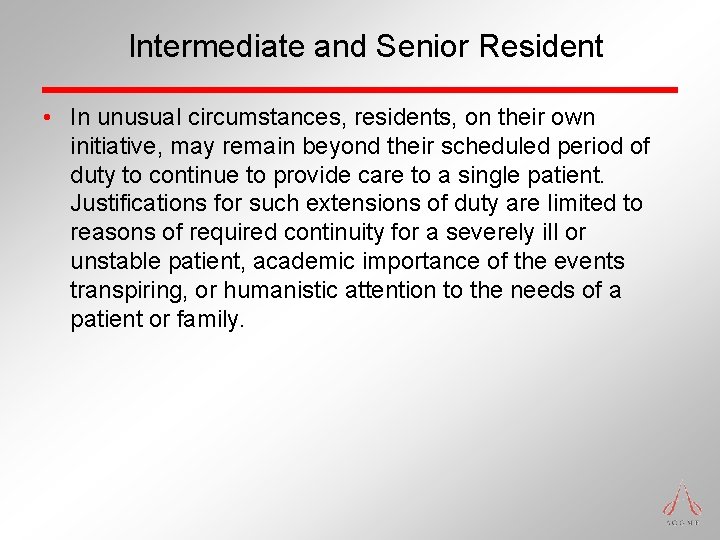

Intermediate and Senior Resident • In unusual circumstances, residents, on their own initiative, may remain beyond their scheduled period of duty to continue to provide care to a single patient. Justifications for such extensions of duty are limited to reasons of required continuity for a severely ill or unstable patient, academic importance of the events transpiring, or humanistic attention to the needs of a patient or family.

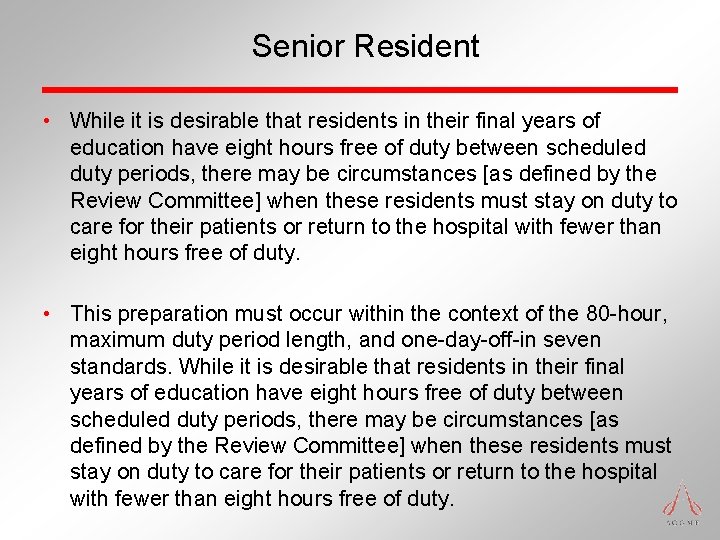

Senior Resident • While it is desirable that residents in their final years of education have eight hours free of duty between scheduled duty periods, there may be circumstances [as defined by the Review Committee] when these residents must stay on duty to care for their patients or return to the hospital with fewer than eight hours free of duty. • This preparation must occur within the context of the 80 -hour, maximum duty period length, and one-day-off-in seven standards. While it is desirable that residents in their final years of education have eight hours free of duty between scheduled duty periods, there may be circumstances [as defined by the Review Committee] when these residents must stay on duty to care for their patients or return to the hospital with fewer than eight hours free of duty.

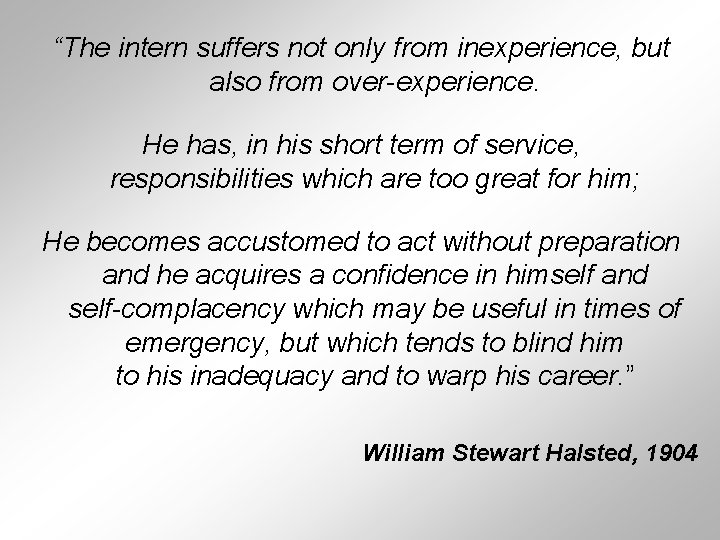

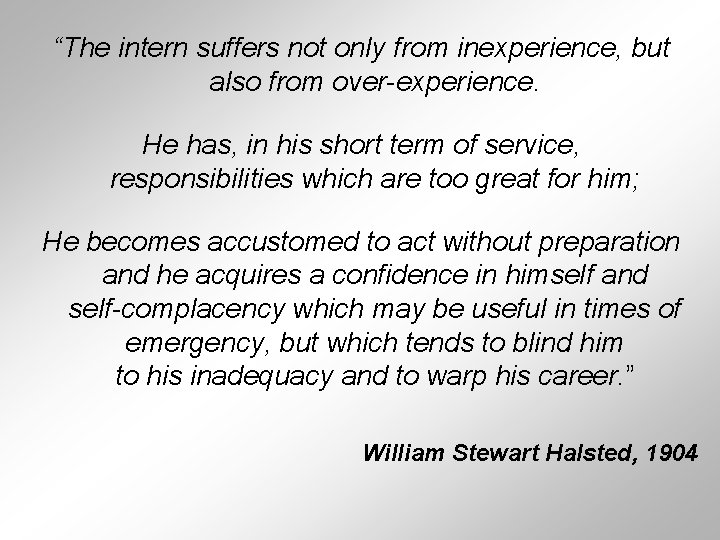

“The intern suffers not only from inexperience, but also from over-experience. He has, in his short term of service, responsibilities which are too great for him; He becomes accustomed to act without preparation and he acquires a confidence in himself and self-complacency which may be useful in times of emergency, but which tends to blind him to his inadequacy and to warp his career. ” William Stewart Halsted, 1904

J M Rodriguez-Paz, M Kennedy, E Salas, A W Wu, J B Sexton, E A Hunt, P J Pronovost. Beyond “see one, do one, teach one”: toward a different training paradigm. Postgrad Med J 2009; 85: 244 -249

ACGME Stifles Innovation? VII. Experimentation and Innovation Requests for experimentation or innovative projects that may deviate from the institutional, common and/or specialty specific program requirements must be approved in advance by the Review Committee. In preparing requests, the program director must follow Procedures for Approving Proposals for Experimentation or Innovative Projects located in the ACGME Manual on Policies and Procedures. Once a Review Committee approves a project, the sponsoring institution and program are jointly responsible for the quality of education offered to residents for the duration of such a project.

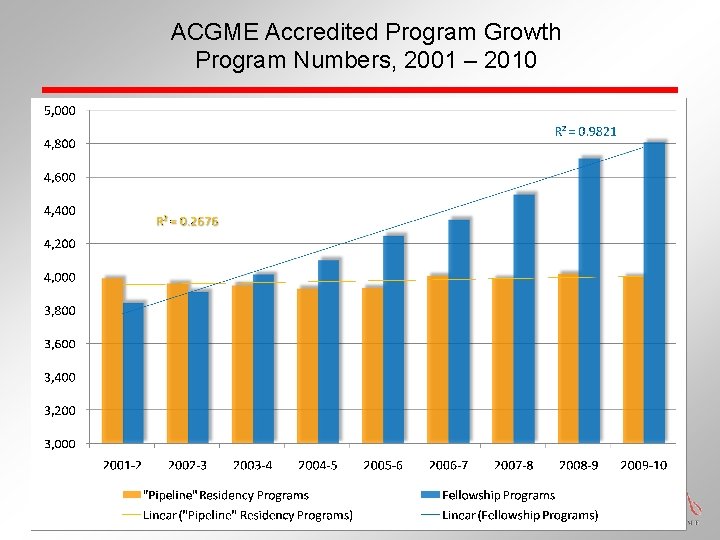

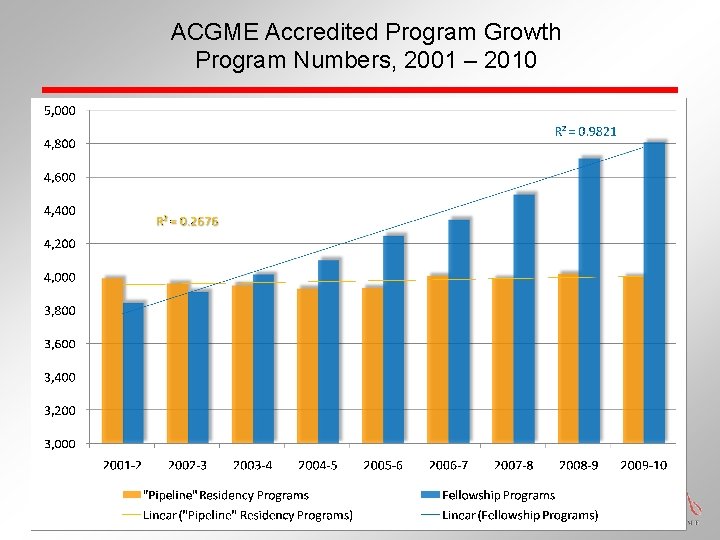

ACGME Accredited Program Growth Program Numbers, 2001 – 2010

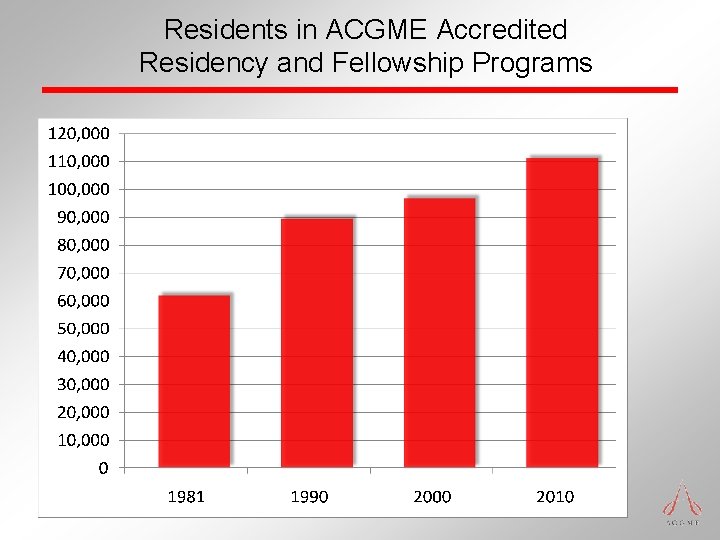

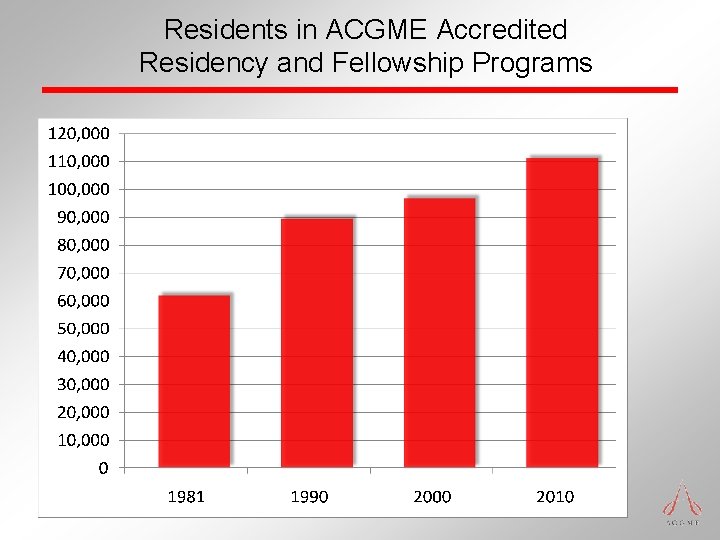

Residents in ACGME Accredited Residency and Fellowship Programs

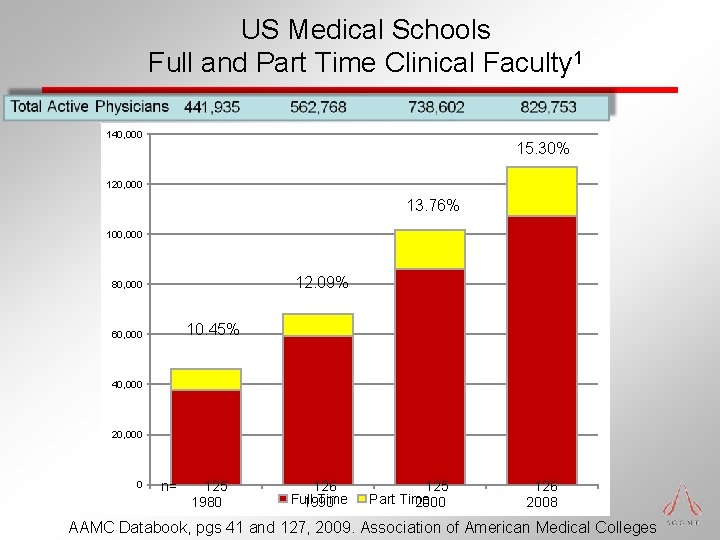

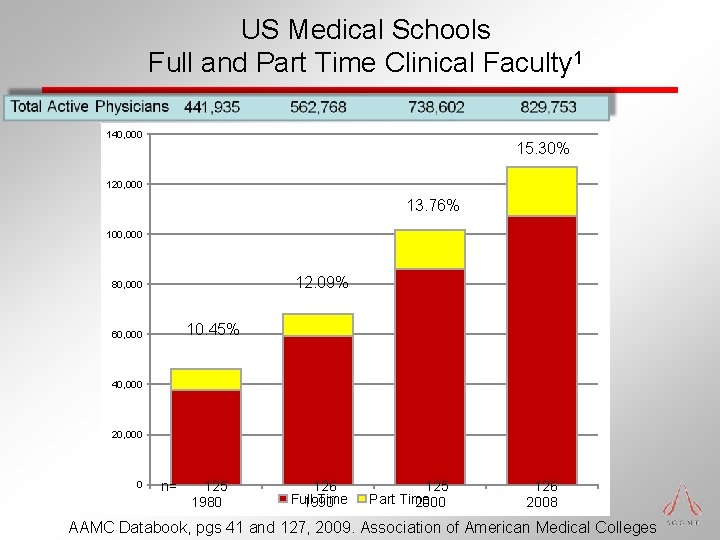

US Medical Schools Full and Part Time Clinical Faculty 1 140, 000 15. 30% 120, 000 13. 76% 100, 000 12. 09% 80, 000 10. 45% 60, 000 40, 000 20, 000 0 n= 125 1980 126 Full Time 1990 125 Part Time 2000 126 2008 AAMC Databook, pgs 41 and 127, 2009. Association of American Medical Colleges

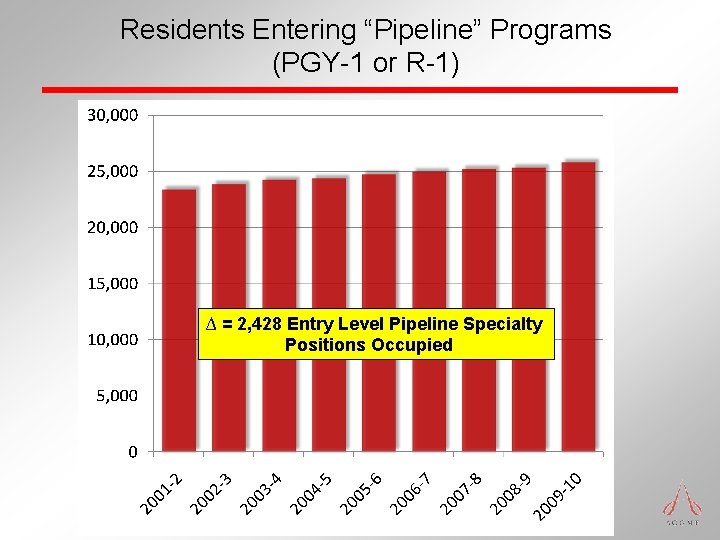

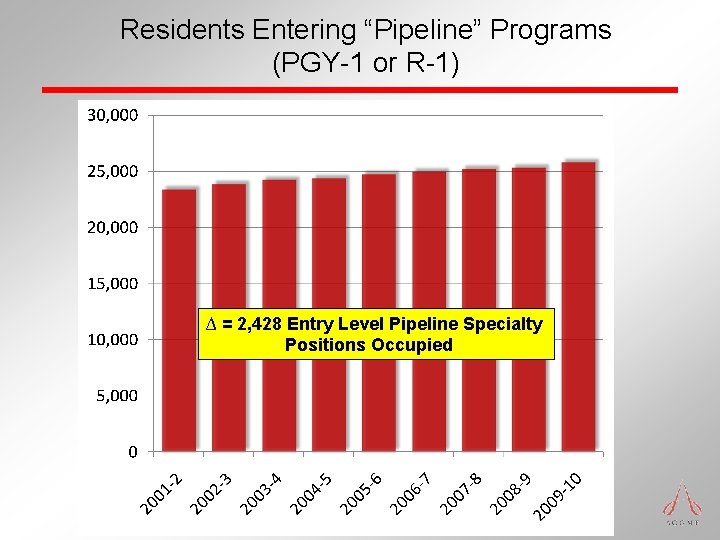

Residents Entering “Pipeline” Programs (PGY-1 or R-1) ∆ = 2, 428 Entry Level Pipeline Specialty Positions Occupied

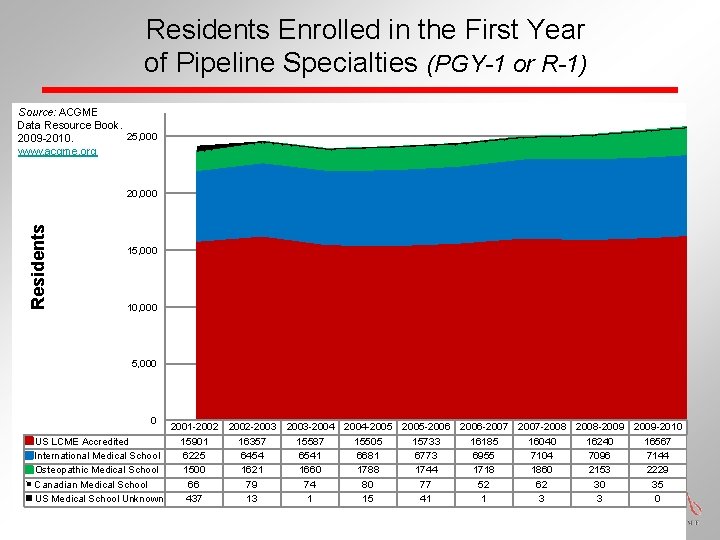

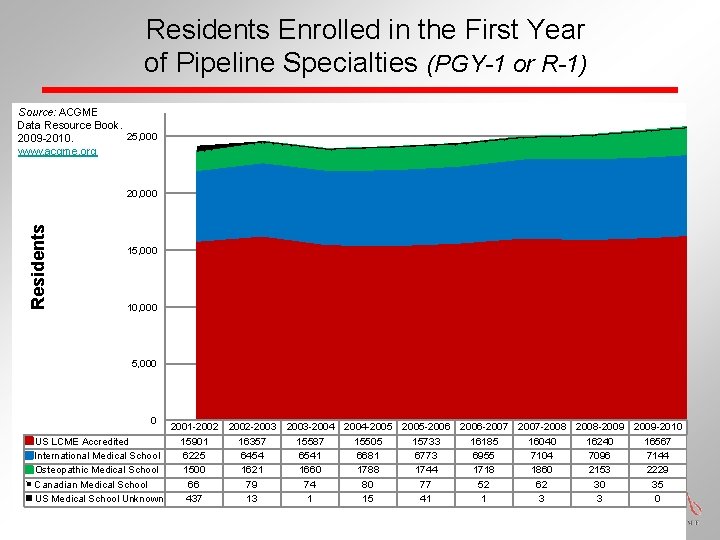

Residents Enrolled in the First Year of Pipeline Specialties (PGY-1 or R-1) Source: ACGME Data Resource Book. 25, 000 2009 -2010. www. acgme. org Residents 20, 000 15, 000 10, 000 5, 000 0 2001 -2002 US LCME Accredited 15901 International Medical School 6225 Osteopathic Medical School 1500 Canadian Medical School 66 US Medical School Unknown 437 2002 -2003 16357 6454 1621 79 13 2003 -2004 15587 6541 1660 74 1 2004 -2005 15505 6681 1788 80 15 2005 -2006 15733 6773 1744 77 41 2006 -2007 16185 6955 1718 52 1 2007 -2008 16040 7104 1860 62 3 2008 -2009 16240 7096 2153 30 3 2009 -2010 16567 7144 2229 35 0

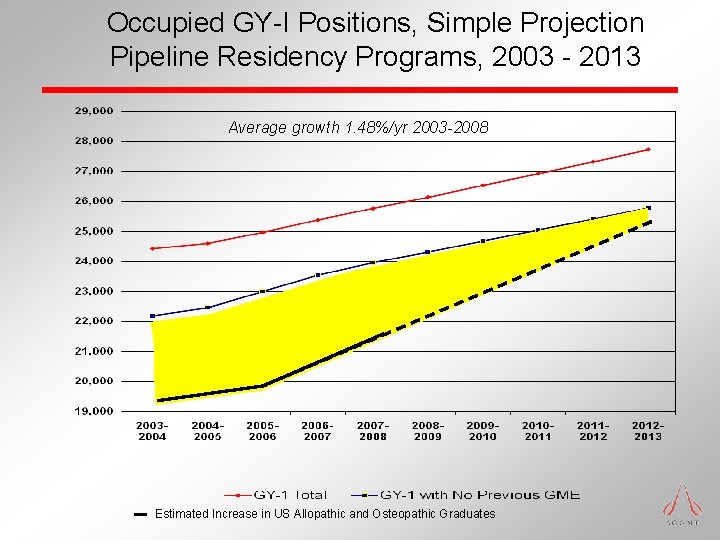

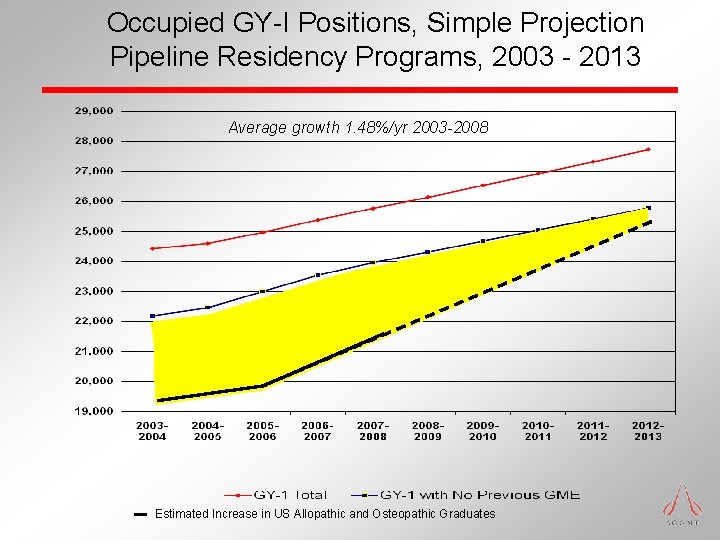

Occupied GY-I Positions, Simple Projection Pipeline Residency Programs, 2003 - 2013 Average growth 1. 48%/yr 2003 -2008 Estimated Increase in US Allopathic and Osteopathic Graduates