Accessing network hardware The Network Interface Controllers are

- Slides: 22

Accessing network hardware The Network Interface Controllers are part of a larger scheme used in modern PCs for device control

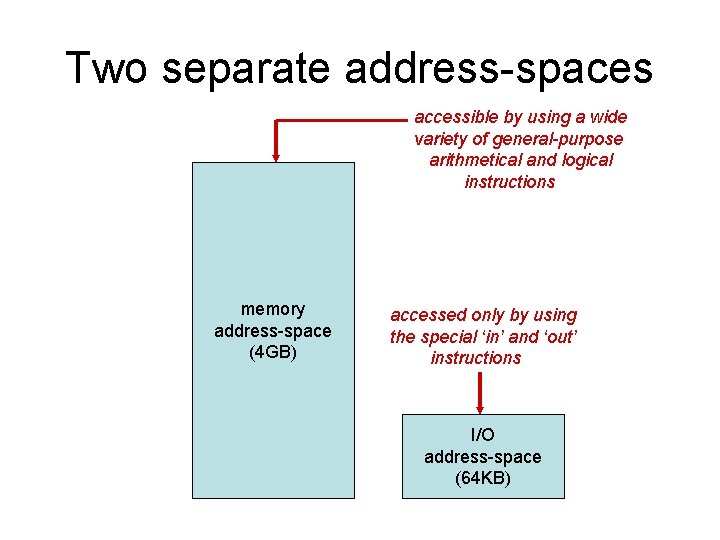

Memory-mapped I/O • Non-Intel processor architectures typically will dedicate a set of memory-addresses to performing communication with hardware devices which are installed in the system • Such architectures allow software to read device-status or write device-commands using ordinary CPU instruction-opcodes, such as ‘mov’, ‘test’, ‘add’, ‘xor’, et cetra

I/O ports • But Intel’s original x 86 architecture used a different approach in which a separate set of addresses and ‘special’ instructions are employed for accessing system devices • The device addresses are called I/O ports, and the opcodes are named ‘in’ and ‘out’: – The ‘in’ instruction reads a device’s ‘status’ – The ‘out’ instruction writes device ‘command’

Range of I/O ports • For devices integrated into a PC system’s motherboard, the port-numbers used were 8 -bit values and could be specified within an I/O instruction, as ‘immediate’ data • Example: in $0 x 64, %al # read port 0 x 64 • For optional devices plugged into ‘slots’ on the motherboard, a port-number could be a 16 -bit value, located in the DX register • Example: in %dx, %al # indirect address

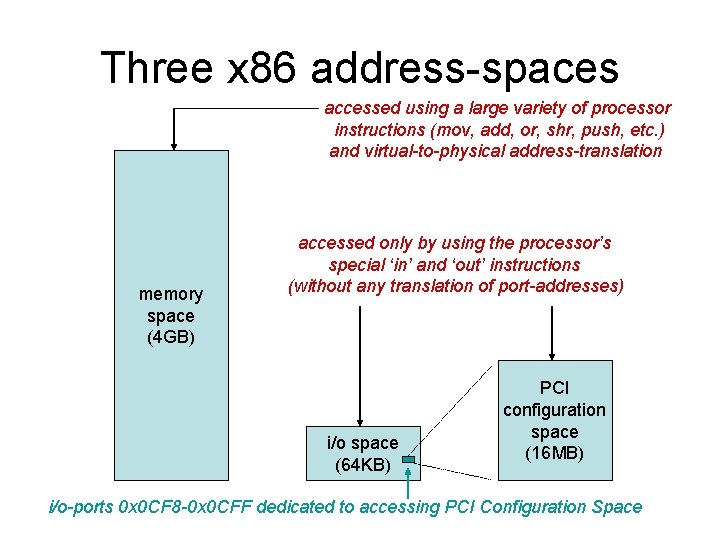

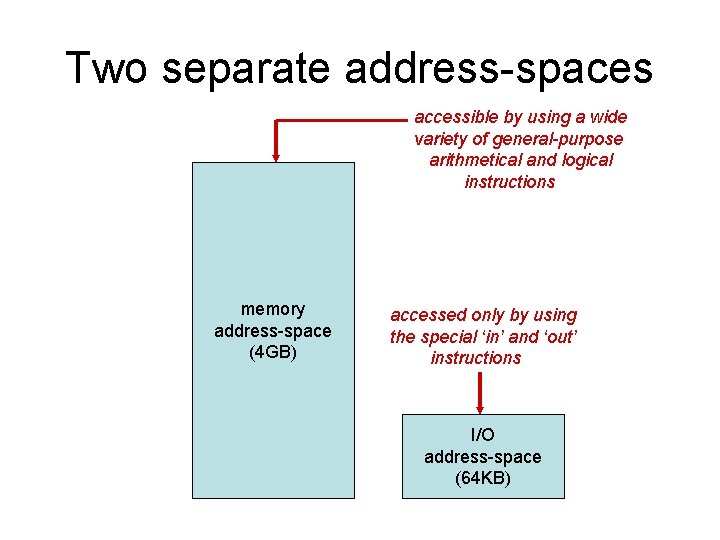

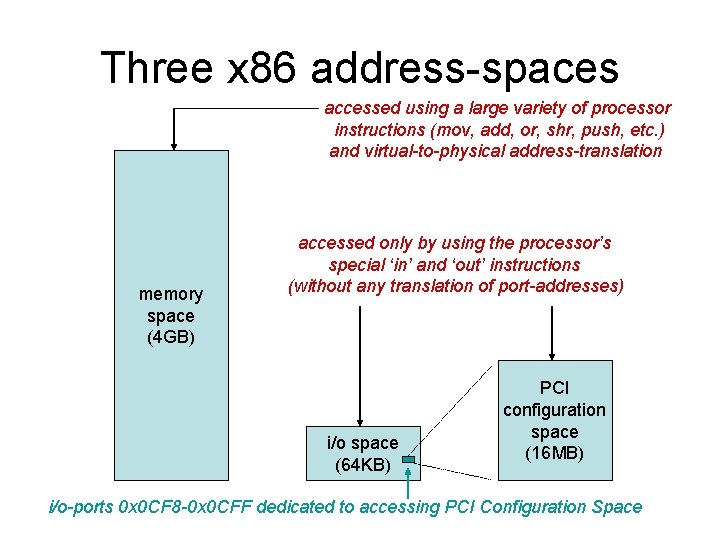

Two separate address-spaces accessible by using a wide variety of general-purpose arithmetical and logical instructions memory address-space (4 GB) accessed only by using the special ‘in’ and ‘out’ instructions I/O address-space (64 KB)

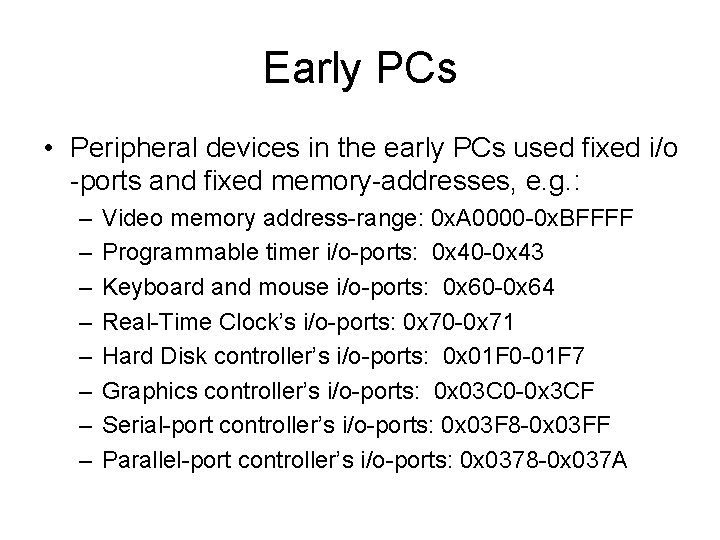

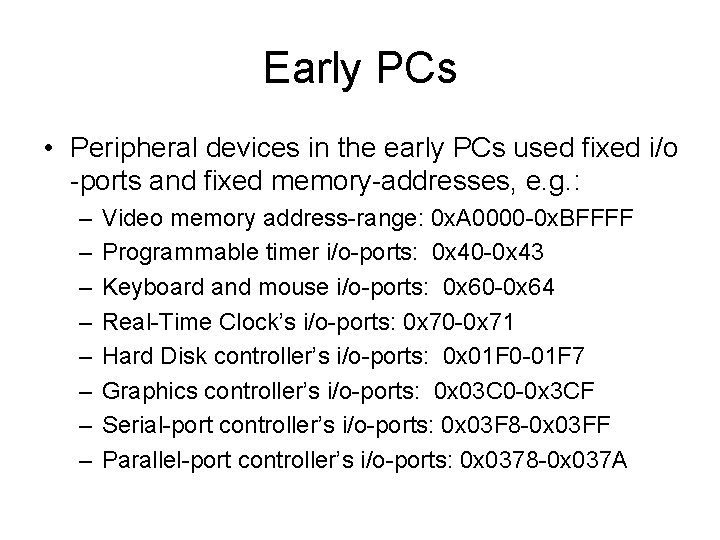

Early PCs • Peripheral devices in the early PCs used fixed i/o -ports and fixed memory-addresses, e. g. : – – – – Video memory address-range: 0 x. A 0000 -0 x. BFFFF Programmable timer i/o-ports: 0 x 40 -0 x 43 Keyboard and mouse i/o-ports: 0 x 60 -0 x 64 Real-Time Clock’s i/o-ports: 0 x 70 -0 x 71 Hard Disk controller’s i/o-ports: 0 x 01 F 0 -01 F 7 Graphics controller’s i/o-ports: 0 x 03 C 0 -0 x 3 CF Serial-port controller’s i/o-ports: 0 x 03 F 8 -0 x 03 FF Parallel-port controller’s i/o-ports: 0 x 0378 -0 x 037 A

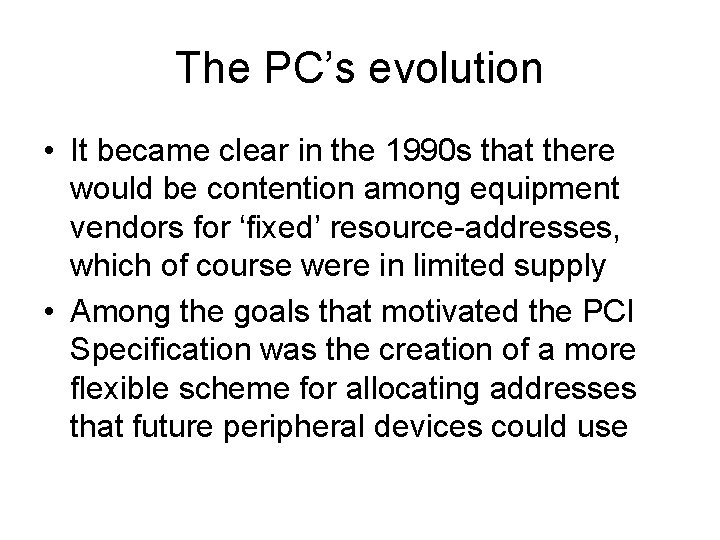

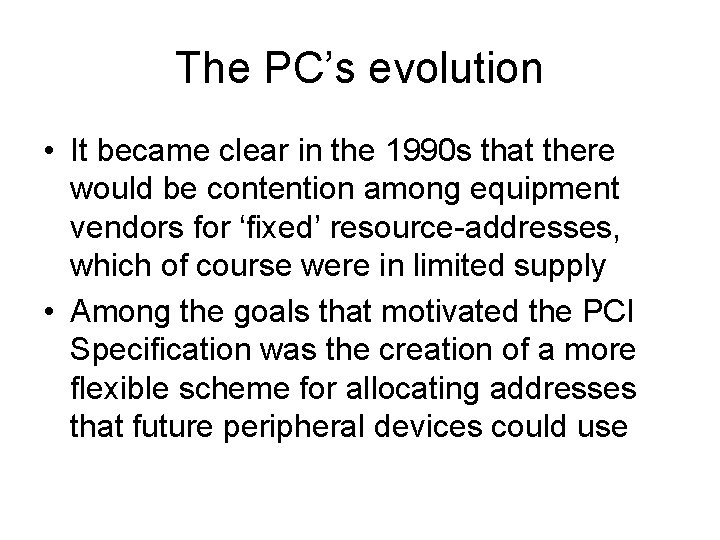

The PC’s evolution • It became clear in the 1990 s that there would be contention among equipment vendors for ‘fixed’ resource-addresses, which of course were in limited supply • Among the goals that motivated the PCI Specification was the creation of a more flexible scheme for allocating addresses that future peripheral devices could use

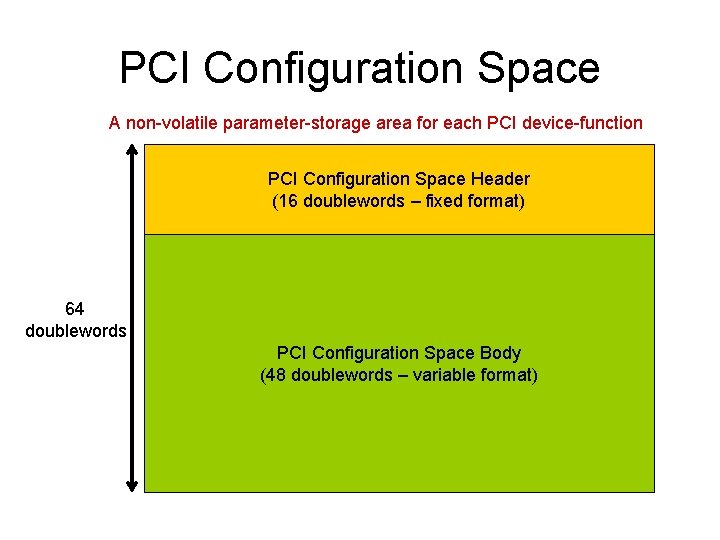

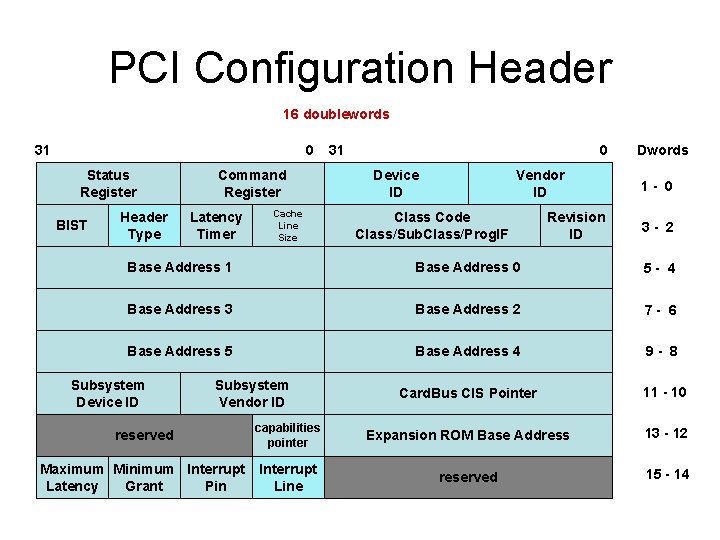

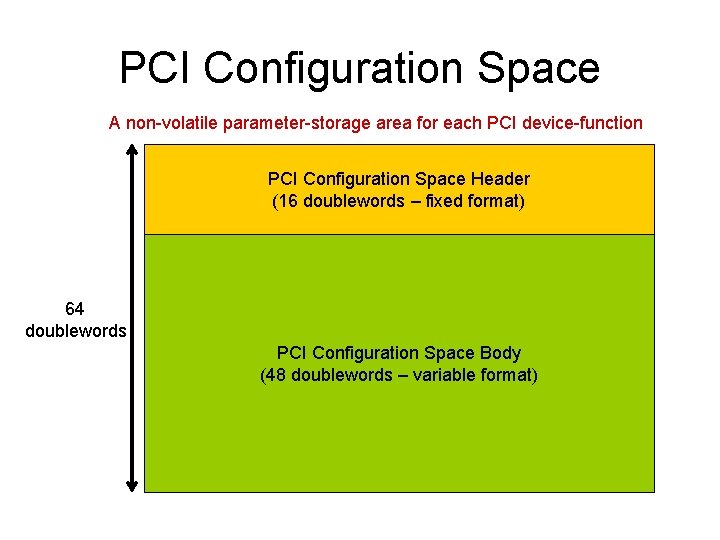

PCI Configuration Space A non-volatile parameter-storage area for each PCI device-function PCI Configuration Space Header (16 doublewords – fixed format) 64 doublewords PCI Configuration Space Body (48 doublewords – variable format)

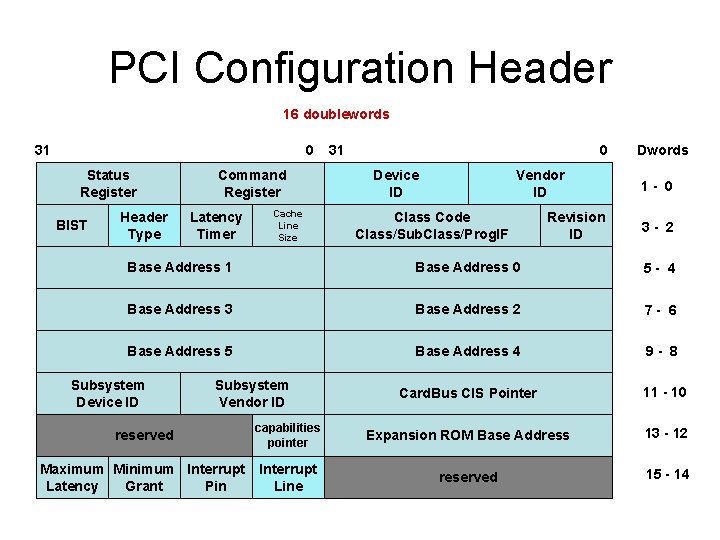

PCI Configuration Header 16 doublewords 31 0 Status Register BIST Header Type Command Register Latency Timer Cache Line Size 31 0 Device ID Vendor ID Class Code Class/Sub. Class/Prog. IF Revision ID Dwords 1 - 0 3 - 2 Base Address 1 Base Address 0 5 - 4 Base Address 3 Base Address 2 7 - 6 Base Address 5 Base Address 4 9 - 8 Card. Bus CIS Pointer 11 - 10 Subsystem Device ID Subsystem Vendor ID reserved capabilities pointer Expansion ROM Base Address 13 - 12 Maximum Minimum Interrupt Latency Grant Pin Interrupt Line reserved 15 - 14

Three x 86 address-spaces accessed using a large variety of processor instructions (mov, add, or, shr, push, etc. ) and virtual-to-physical address-translation memory space (4 GB) accessed only by using the processor’s special ‘in’ and ‘out’ instructions (without any translation of port-addresses) i/o space (64 KB) PCI configuration space (16 MB) i/o-ports 0 x 0 CF 8 -0 x 0 CFF dedicated to accessing PCI Configuration Space

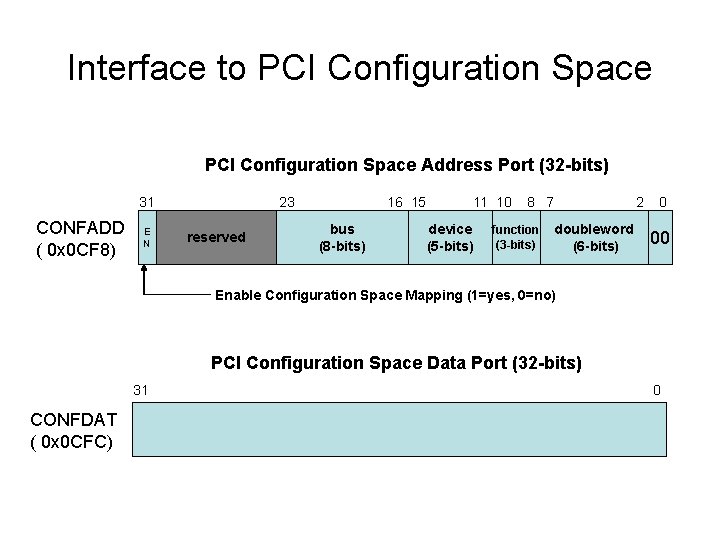

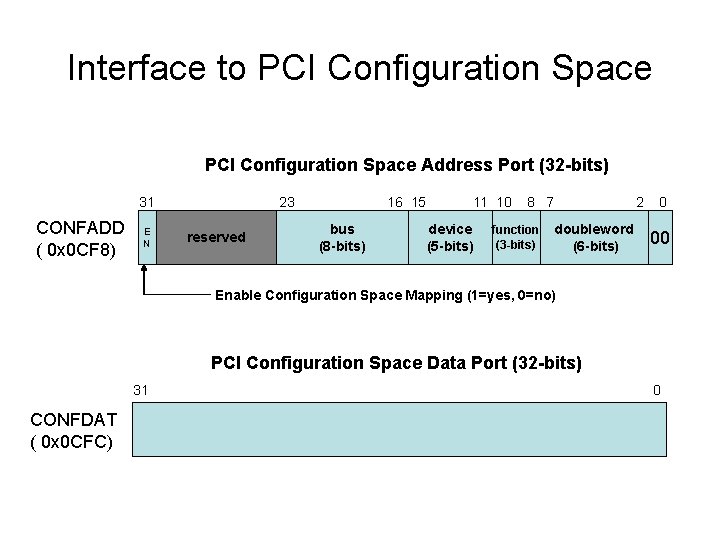

Interface to PCI Configuration Space Address Port (32 -bits) 31 CONFADD ( 0 x 0 CF 8) E N 23 reserved 16 15 bus (8 -bits) 11 10 device (5 -bits) 8 7 function (3 -bits) doubleword (6 -bits) 2 0 00 Enable Configuration Space Mapping (1=yes, 0=no) PCI Configuration Space Data Port (32 -bits) 31 CONFDAT ( 0 x 0 CFC) 0

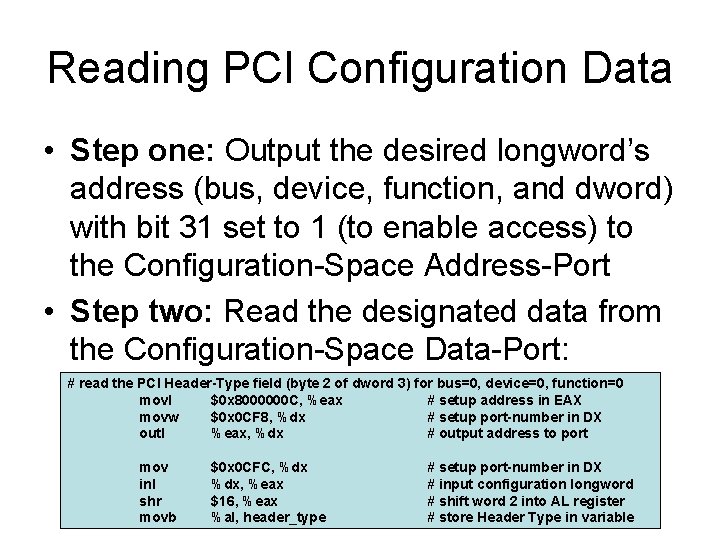

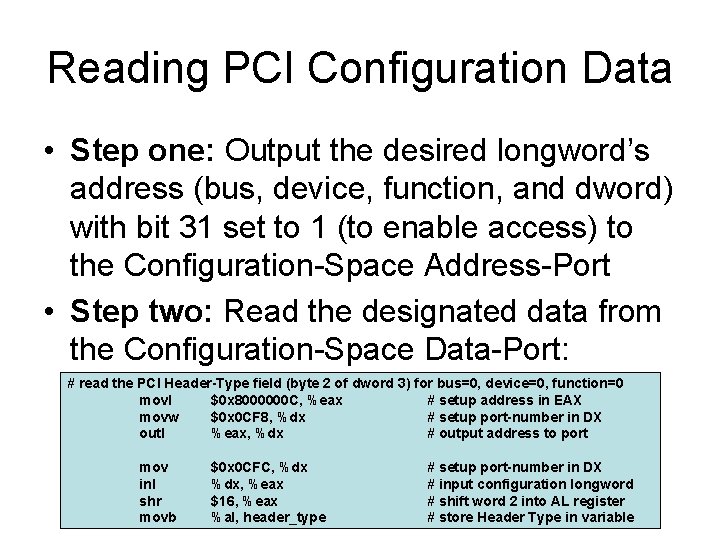

Reading PCI Configuration Data • Step one: Output the desired longword’s address (bus, device, function, and dword) with bit 31 set to 1 (to enable access) to the Configuration-Space Address-Port • Step two: Read the designated data from the Configuration-Space Data-Port: # read the PCI Header-Type field (byte 2 of dword 3) for bus=0, device=0, function=0 movl $0 x 8000000 C, %eax # setup address in EAX movw $0 x 0 CF 8, %dx # setup port-number in DX outl %eax, %dx # output address to port mov inl shr movb $0 x 0 CFC, %dx, %eax $16, %eax %al, header_type # setup port-number in DX # input configuration longword # shift word 2 into AL register # store Header Type in variable

Demo Program • We created a short Linux utility that searches for and reports all of your system’s PCI devices • It’s named “pciprobe. cpp” on our class website • It uses some C++ macros that expand to Intel input/output instructions -- which normally are ‘privileged’ instructions that a Linux applicationprogram is not allowed to execute (segfault!) • But using ‘sudo’ you can escalate the privilegelevel at which this utility-program will be run: $ sudo. /pciprobe

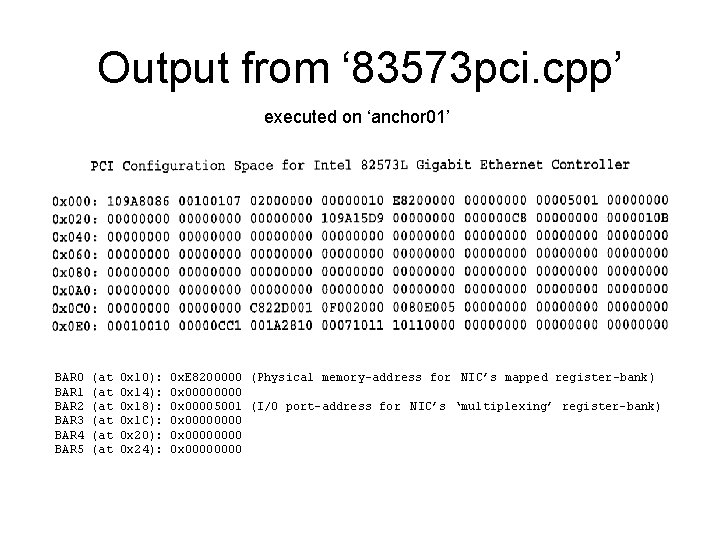

Example: network interface • We can identify the network interface controllers in our classroom’s PC’s by class-code 0 x 02 • Then the subclass-code 0 x 00 is for ‘Ethernet’ • We can identify the NIC from its VENDOR and DEVICE identification-numbers: • VENDOR_ID = 0 x 8086 • DEVICE_ID = 0 x 109 A // for Intel Corporation // for 82573 L controller • Our second demo-program (i. e, ‘ 82573 pci. cpp’) shows this nic’s full PCI Configuration Space

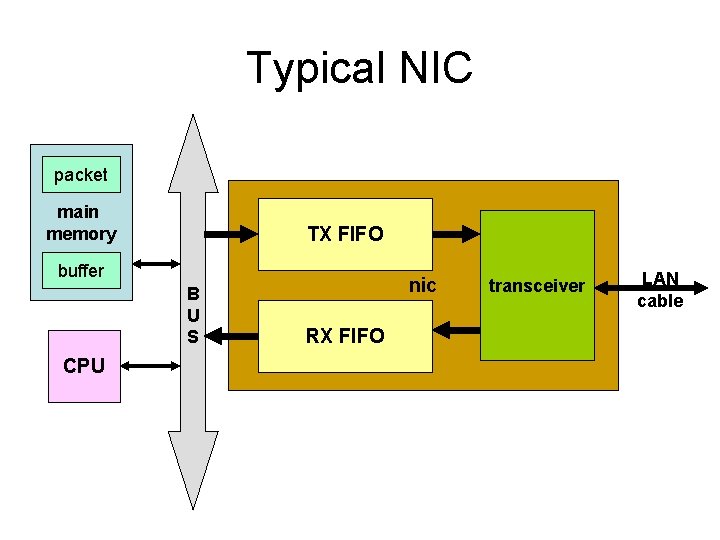

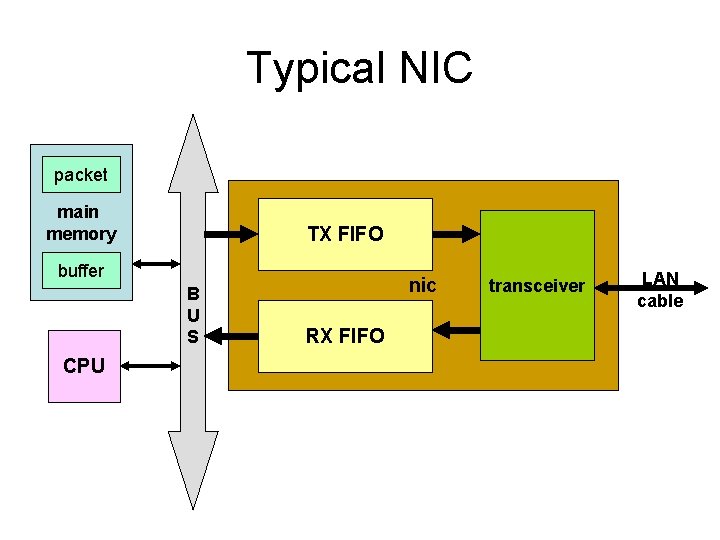

Typical NIC packet main memory TX FIFO buffer B U S CPU nic RX FIFO transceiver LAN cable

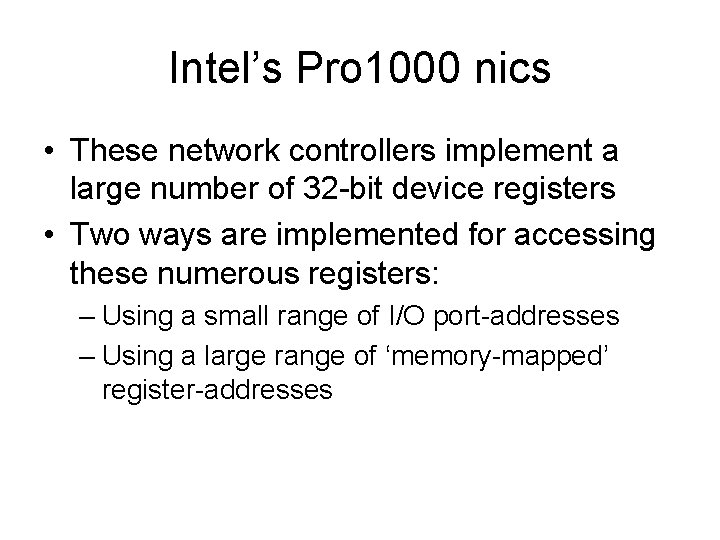

Intel’s Pro 1000 nics • These network controllers implement a large number of 32 -bit device registers • Two ways are implemented for accessing these numerous registers: – Using a small range of I/O port-addresses – Using a large range of ‘memory-mapped’ register-addresses

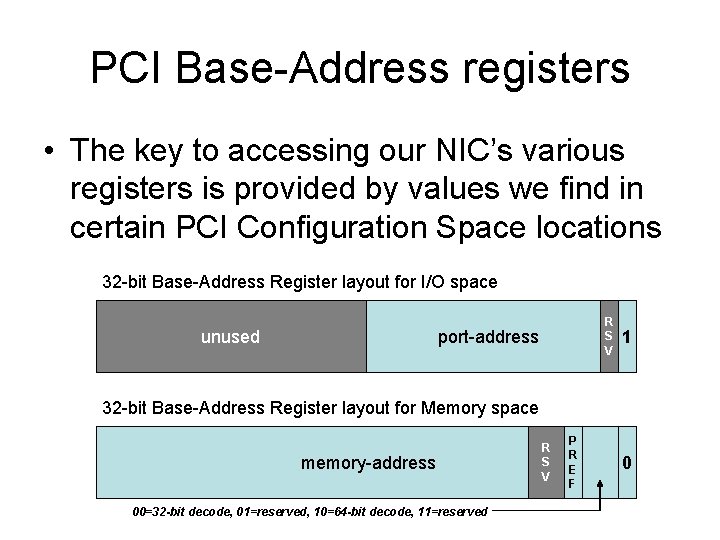

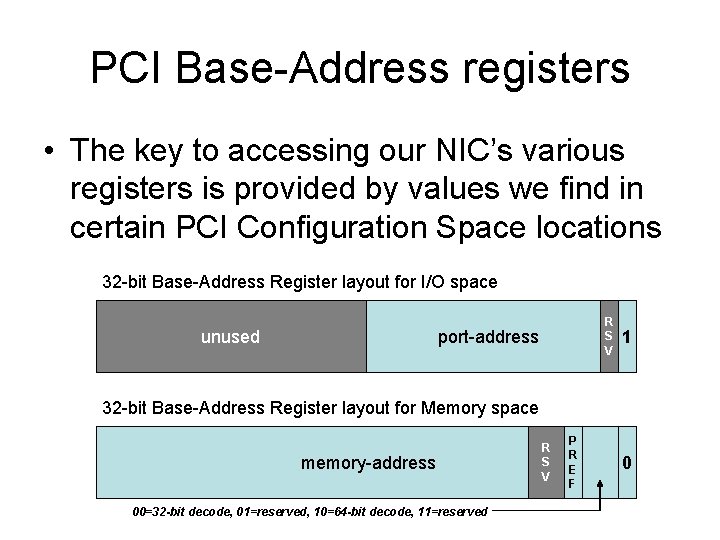

PCI Base-Address registers • The key to accessing our NIC’s various registers is provided by values we find in certain PCI Configuration Space locations 32 -bit Base-Address Register layout for I/O space unused R S V port-address 1 32 -bit Base-Address Register layout for Memory space memory-address 00=32 -bit decode, 01=reserved, 10=64 -bit decode, 11=reserved R S V P R E F 0

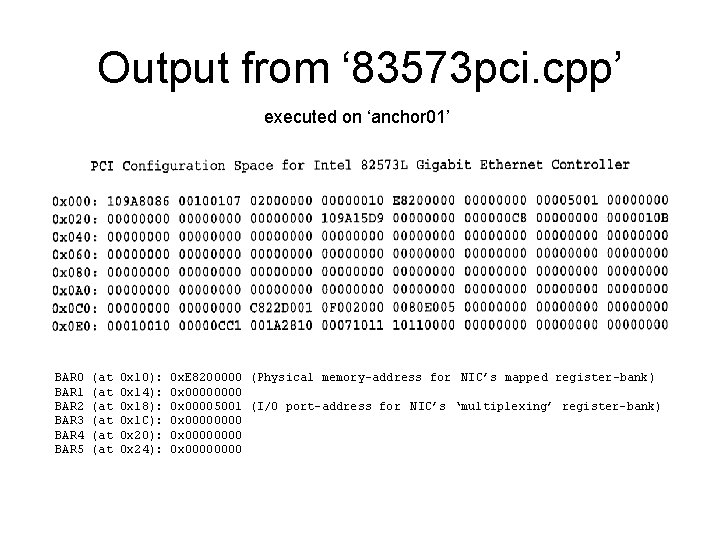

Output from ‘ 83573 pci. cpp’ executed on ‘anchor 01’ BAR 0 BAR 1 BAR 2 BAR 3 BAR 4 BAR 5 (at (at (at 0 x 10): 0 x 14): 0 x 18): 0 x 1 C): 0 x 20): 0 x 24): 0 x. E 8200000 (Physical memory-address for NIC’s mapped register-bank) 0 x 00005001 (I/O port-address for NIC’s ‘multiplexing’ register-bank) 0 x 00000000 0 x 0000

‘mapped’ advantage • For high-performance (and ‘thread-safe’) access to the NIC’s bank of registers, the memory-mapped option offers very clear advantages over multiplexed I/O access: – Access is faster to memory than to I/O ports – Access to memory is ‘atomic’, whereas the multiplexed access via I/O ports is a 2 -step operation, giving rise to ‘race conditions’

I/O advantage • But during the system’s ‘startup’ process (before the Operating System is loaded), there’s no alternative but to use the I/O access-method, because the memorymapped registers are at high addresses which the processor cannot yet reach • For example, in cases where an OS needs to be loaded via a BOOTP network-server

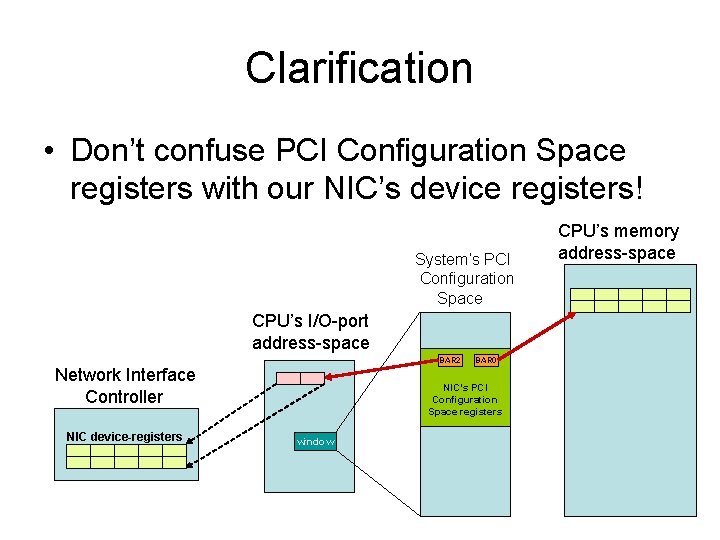

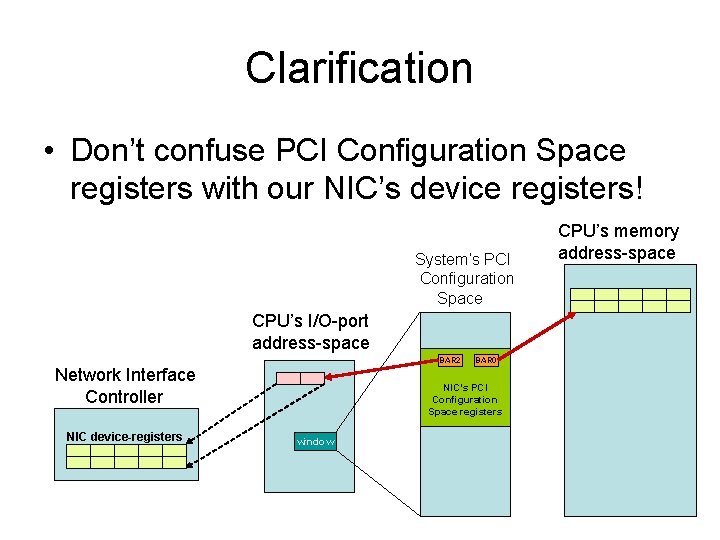

Clarification • Don’t confuse PCI Configuration Space registers with our NIC’s device registers! System’s PCI Configuration Space CPU’s I/O-port address-space BAR 2 Network Interface Controller NIC device-registers BAR 0 NIC’s PCI Configuration Space registers window CPU’s memory address-space

In-class exercise • Copy our ‘ 82573 pci. cpp’ source-module to your own directory, then rename it as ‘audio. cpp’ • Your assignment is to modify it so that it will display the PCI Configuration Space registers in our classroom workstation’s sound-card (a ‘multimedia’ class device)