Access Control Models From the realworld to trusted

- Slides: 35

Access Control Models: From the real-world to trusted computing

Lecture Motivation l We have looked at protocols for distributing and establishing keys used for authentication and confidentiality l But who should you give these keys to? Who should you trust? What are the rules governing when to and not to give out security credentials l In this lecture, we will look at the broad area of secure and trusted systems – We will focus on access control models – These methods are often used to abstract the requirements for a computer system – But, they hold for general systems where security is a concern (e. g. networks, computers, companies…)

Lecture Outline l Some generic discussion about security l Objects that require protection l Insights from the real-world l Access control to memory and generic objects – Discretionary Methods: Directory Lists, Access Control Lists, and the Access Control Matrix, Take-Grant Model – Failures of DACs: Trojan Horses – Dominance and information flow, Multilevel security and lattices – Bell-La. Padula and Biba’s Model l What is a trusted system? Trusted Computing Base

System-security vs. Message-security l In the cryptographic formulation of security, we were concerned with the confidentiality, authenticity, integrity, and nonrepudiation of messages being exchanged – This is a message-level view of security l A system-level view of security has slightly different issues that need to be considered – Confidentiality: Concealment of information or resources from those without the right or privilege to observe this information – Integrity: Trustworthiness of data (has an object been changed in an unauthorized manner? ) – Availability: Is the system and its resources available for usage?

Confidentiality in Systems l l Many of the motivations behind confidentiality comes from the military’s notion of restricting access to information based on clearance levels and need-to-know Cryptography supports confidentiality: The scrambling of data makes it incomprehensible. – Cryptographic keys control access to the data, but the keys themselves become an object that must be protected l System-dependent mechanisms can prevent processes from illicitly accessing information – Example: Owner, group, and public concepts in Unix’s r/w/x definition of access control l Resource-hiding: – Often revealing what the configuration of a system is (e. g. use of a Windows web server), is a desirable form of confidentiality

Integrity in Systems l Integrity includes: – Data integrity (is the content unmodified? ) – Origin integrity (is the source of the data really what is claimed, aka. Authentication) l Two classes of integrity mechanisms: Prevention and Detection l Prevention: Seek to block unauthorized attempts to change the data, or attempts to change data in unauthorized ways – A user should not be able to change data he is not authorized to change – A user with privileges to work with or alter the data should not be allowed to change data in ways not authorized by the system – The first type is addressed through authentication and access control – The second type is much harder and requires policies l Detection: Seek to report that data’s integrity has been violated – Achieved by analyzing the system’s events (system logs), or analyze data to see if required constraints are violated

Availability of Systems l Availability is concerned with system reliability – The security side of the issue: An adversary may try to make a resource or service unavailable – Implications often take the form: Eve compromises a secondary system and then denies service to the primary system… as a result all requests of the first system get redirected to second system – Hence, when used in concert with other methods, the effects can be very devastating l Denial of service attacks are an example: – Preventing the server from having the resources needed to perform its function – Prevent the destination from receiving messages – Denial of service is not necessary deliberate

Threats l There are several threats that may seek to undermine confidentiality, integrity, and availability: – Disclosure Threats: Causing unauthorized access to information – Deception Threats: Causing acceptance of false data – Disruption Threats: Prevention of correct operation of a service – Usurpation Threats: Unauthorized control of some service l Examples: – Snooping: Unauthorized interception of information (passive Disclosure) – Modification/Alteration: Unauthorized change of information (active Deception, Disruption, Usurpation) – Masquerading/Spoofing: Impersonation of one entity by another (Deception and Disruption) – Repudiation of Origin: False denial that an entity sent or created data (Deception) – Denial of Receipt: A false denial that an entity received some information or message (Deception) – Delay: A temporary delay in the delivery of a service (Usurpation) – Denial of Service: A long-term inhibition of service (Usurpation)

Overview Security Policies l Definition: A security policy is a statement of what is allowed and what is not allowed to occur between entities in a system l Definition: A security mechanism is a method for enforcing a security policy l Policies may be expressed mathematically – Allowed and disallowed states may be specified – Rules may be formulated for which entity is allowed to do which action l These policies may seek to accomplish: – Prevention – Detection – Recovery l This lecture will focus primarily on formal statements of security policies – Specifically, we will focus on policies associated with access control and information flow

Objects that Need Protection l Modern operating systems follow a multiprogramming model: – Resources on a single computer system (extend this to a generic system) could be shared and accessed by multiple users – Key technologies: Scheduling, sharing, parallelism – Monitors oversee each process/program’s execution l Challenge of the multiprogramming environment: Now there are more entities to deal with… hard to keep every process/user happy when sharing resources… Even harder if one user is malicious Several objects that need protection: – Memory – File or data on an auxiliary storage device – Executing program in memory – Directory of files – Hardware Devices – Data structures and Tables in operating systems – Passwords and user authentication mechanisms – Protection mechanisms l

Basic Strategies for Protection l There a few basic mechanisms at work in the operating system that provide protection: – Physical separation: processes use different physical objects (different printers for different levels of users) – Temporal separation: Processes having different security requirements are executed at different time – Logical separation: Operating system constrains a program’s accesses so that it can’t access objects outside its permitted domain – Cryptographic separation: Processes conceal their data in such a way that they are unintelligible to outside processes – Share via access limitation: Operating system determines whether a user can have access to an object – Limit types of use of an object: Operating system determines what operations a user might perform on an object l When thinking of access to an object, we should consider its granularity: – Larger objects are easier to control, but sometimes pieces of large objects don’t need protection. – Maybe break objects into smaller objects (see Landwehr)

Access Control to Memory l Memory access protection is one of the most basic functionalities of a multiprogramming OS l Memory protection is fairly simple because memory access must go through certain points in the hardware – Fence registers, Base/Bound registers – Tagged architectures: Every word of machine memory has one or more extra bits to identify access rights to that word (these bits are set only by privileged OS operations) – Segmentation: Programs and data are broken into segments. The OS maintains a table of segment names and their true addresses. The OS may check each request for memory access when it conducts table lookup. l More general objects may be accessed from a broader variety of entry points and there may be many levels of privileges: – No central authority!

Insight from Real-world Security Models l Not all information is equally sensitive– some data will have more drastic consequences if leaked than other. – Military sensitivity levels: unclassified, confidential, secret, top secret l Generally, fewer people knowing a secret makes it easier to control dissemination of that information – Military notion of need-to-know: Classified information should not be entrusted to an individual unless he has both the clearance level and the need to know that information – Compartments: Breaking information into specific topical areas (compartments) and using that as a component in deciding access – Security levels consist of sensitivity levels and the corresponding compartments – If information is designated to belong to multiple compartments, then the individual must be cleared for all compartments before he can access the information.

Real-world Security Models, pg. 2 l Documents may be viewed as a collection of sub-objects, some of which are more sensitive than others. – Hence, objects may be multilevel in their security context. – Level of classification of an object or document is usually the classification of its most sensitive information it contains. l Aggregation Problem: Often times the combination of two pieces of data creates a new object that is more sensitive than either of the pieces separately l Sanitization Problem: Documents may have sensitive information removed in an effort to sanitize the document. It is a challenge to determine when enough information has been removed to densensitize a document.

Multilevel Security Models l We want models that represent a range of sensitivities and that separate subjects from the objects they should not have access to. l The military has developed various models for securing information l We will look at several models for multilevel security – Object-by-Object Methods: Directory lists, Access control matrix, Take-Grant Model – Lattice model: A generalized model – Bell-La. Padula Model – Biba Model

Access Control to Objects l Some terminology: – Protection system: The component of the system architecture whose task is to protect and enforce security policies – Object: An object is an entity that is to be protected (e. g. a file, or a process) – Subject: Set of active objects (such as processes and users) that have interaction with other – Rights: The rules and relationships allowed to exist between subjects and objects l l Directory-based Access Control (aka. Capability List): A list for each subject which specifies which objects that subject can access (and what rights) Access Control List: A list for each object that specifies which subjects can access it (and how).

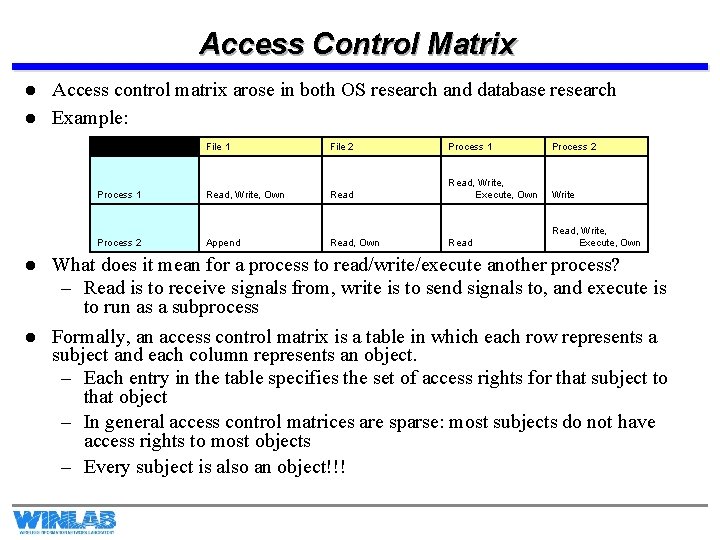

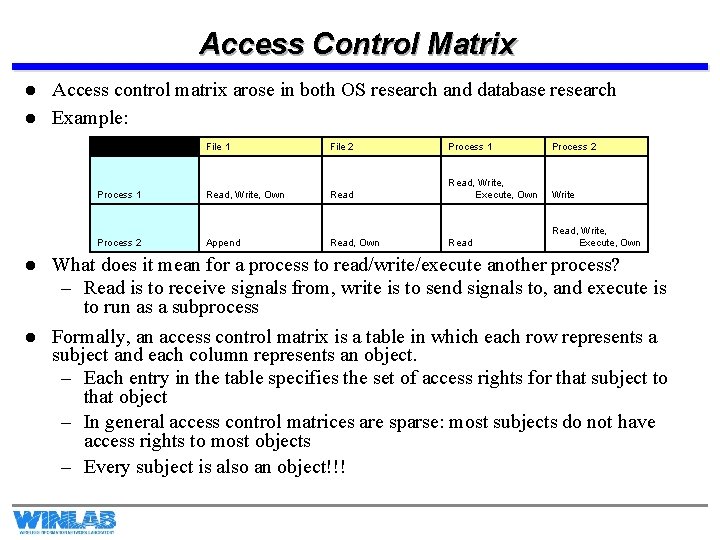

Access Control Matrix l l Access control matrix arose in both OS research and database research Example: File 1 File 2 Process 1 Process 2 Process 1 Read, Write, Own Read, Write, Execute, Own Write Process 2 Append Read, Own Read, Write, Execute, Own l What does it mean for a process to read/write/execute another process? – Read is to receive signals from, write is to send signals to, and execute is to run as a subprocess l Formally, an access control matrix is a table in which each row represents a subject and each column represents an object. – Each entry in the table specifies the set of access rights for that subject to that object – In general access control matrices are sparse: most subjects do not have access rights to most objects – Every subject is also an object!!!

Access Control Matrix, pg. 2 l All accesses to objects by subjects are mediated by an enforcement mechanism that uses the access matrix – This enforcement mechanism is the reference monitor. – Some operations allow for modification of the matrix (e. g. owner might be allowed to grant permission to another user to read a file) – Owner has complete discretion to change the access rules of an object it owns (discretionary access control) l The access control matrix is a generic way of specifying rules, and is not beholden to any specific access rules – It is therefore very flexible and suitable to a broad variety of scenarios – However, it is difficult to prove assertions about the protection provided by systems following an access control matrix without looking at the specific meanings of subjects, objects, and rules – Not suitable for specialized requirements, like the military access control model.

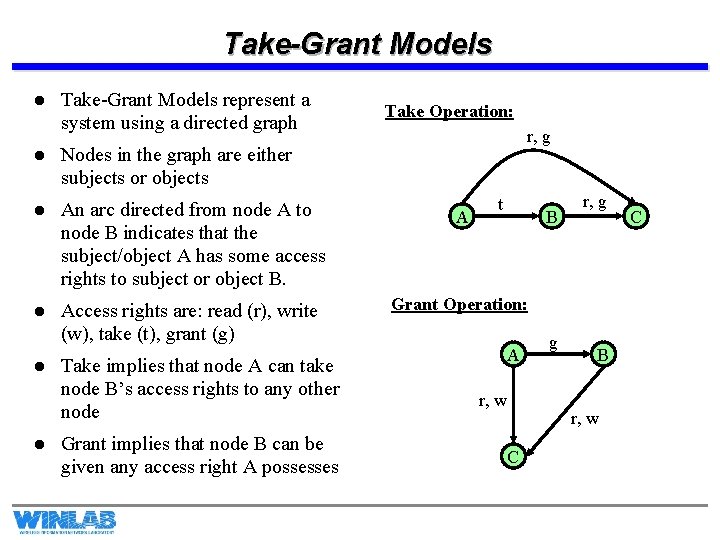

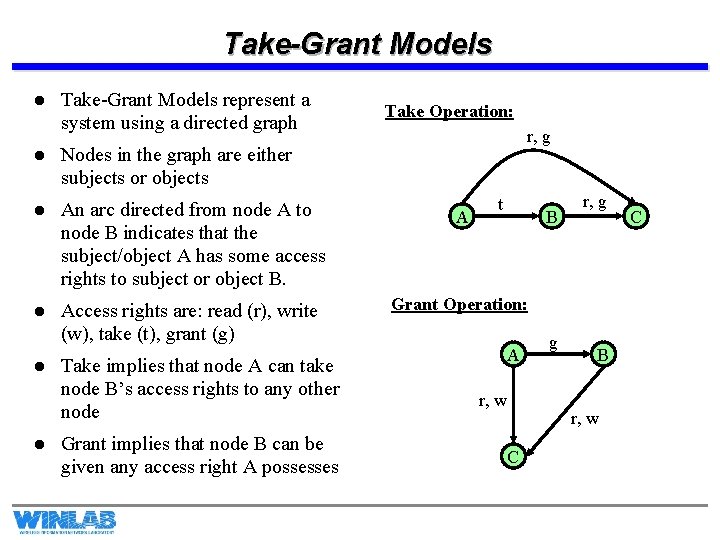

Take-Grant Models l Take-Grant Models represent a system using a directed graph Take Operation: r, g l Nodes in the graph are either subjects or objects l An arc directed from node A to node B indicates that the subject/object A has some access rights to subject or object B. A l Access rights are: read (r), write (w), take (t), grant (g) Grant Operation: l l Take implies that node A can take node B’s access rights to any other node Grant implies that node B can be given any access right A possesses t B A r, w g r, g B r, w C C

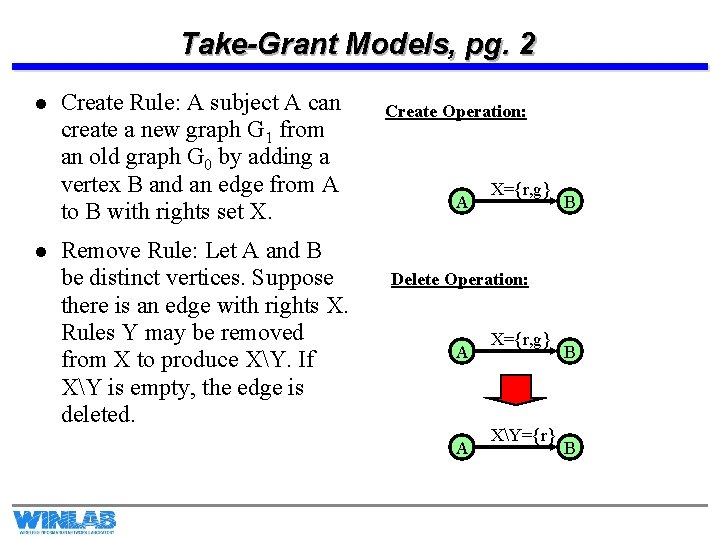

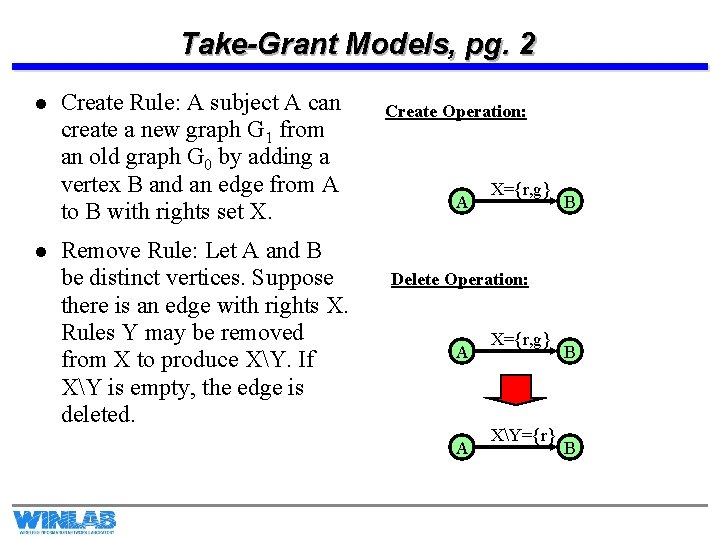

Take-Grant Models, pg. 2 l l Create Rule: A subject A can create a new graph G 1 from an old graph G 0 by adding a vertex B and an edge from A to B with rights set X. Remove Rule: Let A and B be distinct vertices. Suppose there is an edge with rights X. Rules Y may be removed from X to produce XY. If XY is empty, the edge is deleted. Create Operation: A X={r, g} B Delete Operation: A A X={r, g} XY={r} B B

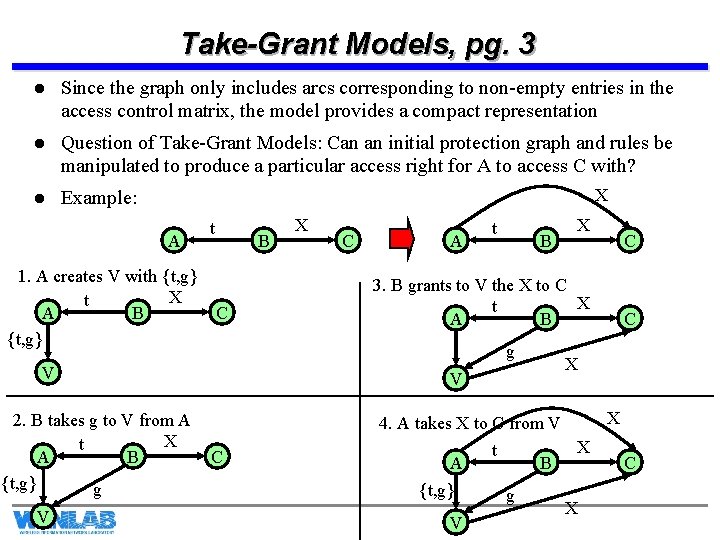

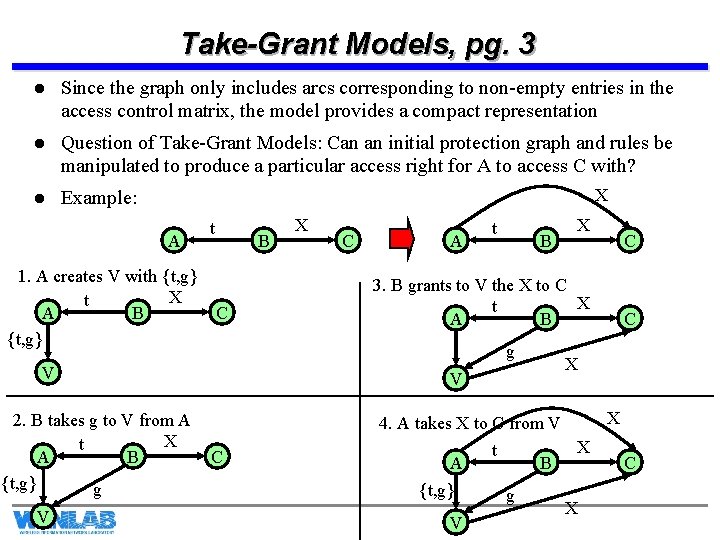

Take-Grant Models, pg. 3 l Since the graph only includes arcs corresponding to non-empty entries in the access control matrix, the model provides a compact representation l Question of Take-Grant Models: Can an initial protection graph and rules be manipulated to produce a particular access right for A to access C with? l Example: X A 1. A creates V with {t, g} X t A B {t, g} t B C V C A t B V C X 3. B grants to V the X to C X t A B g V 2. B takes g to V from A X t A B {t, g} g X C C X X 4. A takes X to C from V X t A B C {t, g} V g X

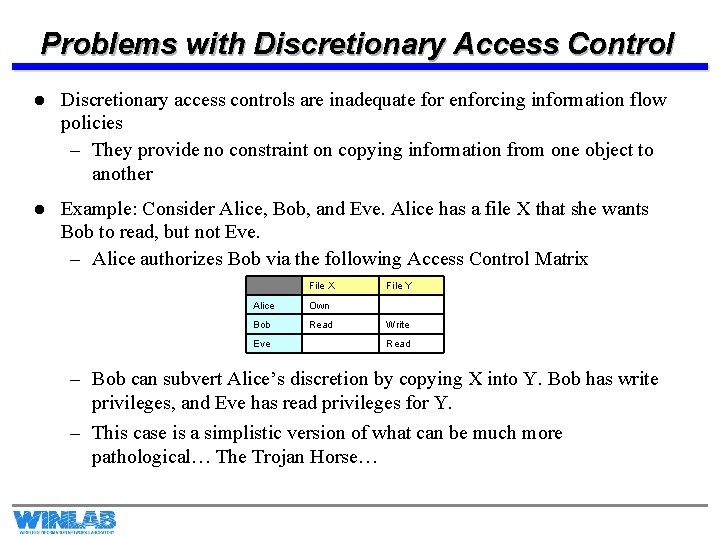

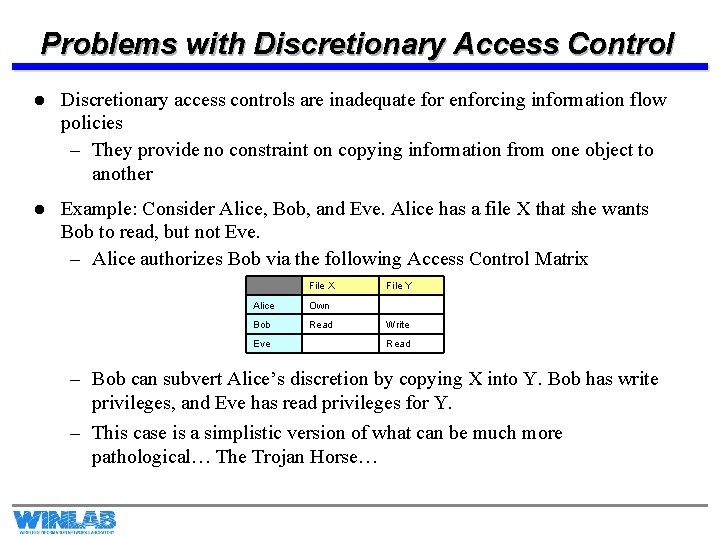

Problems with Discretionary Access Control l Discretionary access controls are inadequate for enforcing information flow policies – They provide no constraint on copying information from one object to another l Example: Consider Alice, Bob, and Eve. Alice has a file X that she wants Bob to read, but not Eve. – Alice authorizes Bob via the following Access Control Matrix File X File Y Alice Own Bob Read Write Eve Read – Bob can subvert Alice’s discretion by copying X into Y. Bob has write privileges, and Eve has read privileges for Y. – This case is a simplistic version of what can be much more pathological… The Trojan Horse…

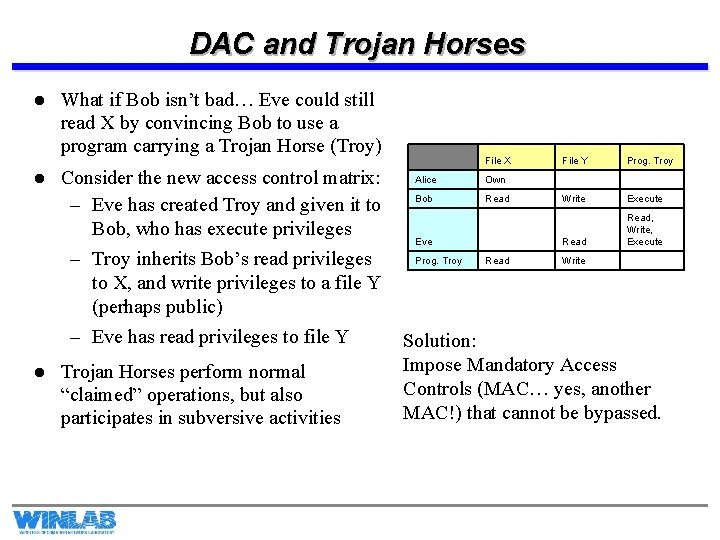

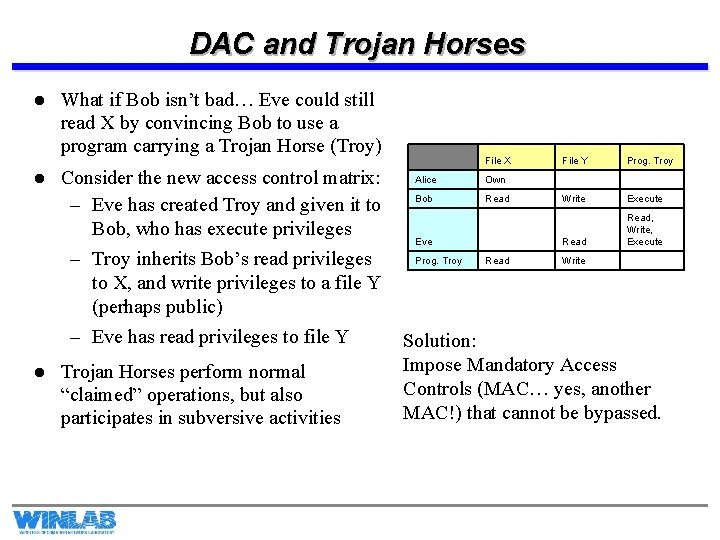

DAC and Trojan Horses l l l What if Bob isn’t bad… Eve could still read X by convincing Bob to use a program carrying a Trojan Horse (Troy) Consider the new access control matrix: – Eve has created Troy and given it to Bob, who has execute privileges – Troy inherits Bob’s read privileges to X, and write privileges to a file Y (perhaps public) – Eve has read privileges to file Y Trojan Horses perform normal “claimed” operations, but also participates in subversive activities File X File Y Prog. Troy Alice Own Bob Read Write Execute Eve Read, Write, Execute Prog. Troy Read Write Solution: Impose Mandatory Access Controls (MAC… yes, another MAC!) that cannot be bypassed.

Dominance and Information Flow l l l There are two basic ways to look at the notion of security privileges: Dominance an For all essential purposes, they are the same, and its just a matter of semantics. Let’s start with dominance: – Each piece of information is ranked at a particular sensitivity level (e. g. unclass – The ranks form a hierarchy, information at one level is less sensitive than infor – Hence, higher level information dominates lower level information l Formally, we define a dominance relation on the set of objects and subjects if: l We say that o dominates s (or s is dominated by o) if .

Dominance and Information Flow, pg. 2 l Now let us look at information flow: – Every object is given a security class (or a security label): Informa – We define a can-flow relationship to specify that infor – We also define a class-combining operator to sp – Implicitly, there is the notion of cannot-flow

Lattice Model of Access Security l The dominance or can-flow relationship defines a partial ordering rel l First, the dominance relationship is transitive and antisymmetric – Transitive: If and , then – Antisymmetric: If and then. l A lattice is a set of elements organized by a partial ordering that satis Supremum: Every pair of elements possesses a least upper bound Infimum: Every pair of elements possesses a greatest lower bound In addition to supremum and infimum between two objects, we need l l l

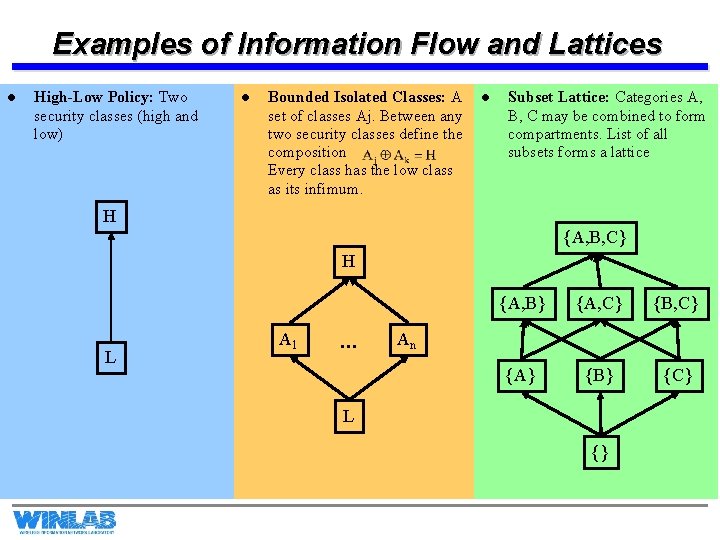

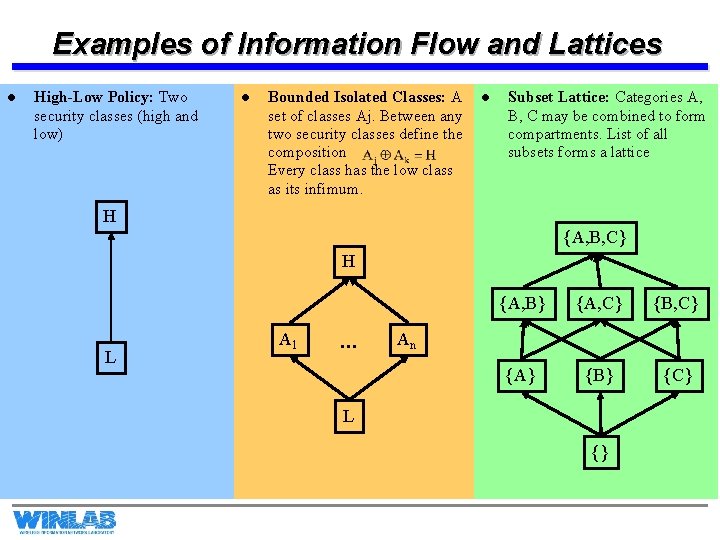

Examples of Information Flow and Lattices l High-Low Policy: Two security classes (high and low) l Bounded Isolated Classes: A set of classes Aj. Between any two security classes define the composition. Every class has the low class as its infimum. l Subset Lattice: Categories A, B, C may be combined to form compartments. List of all subsets forms a lattice H {A, B, C} H L A 1 … {A, B} {A, C} {B, C} {A} {B} {C} An L {}

Mandatory Access Control (MAC) Models l Mandatory Access Control (MAC): When a system mechanism controls access to an object and an individual user cannot alter that access, the control is mandatory access control. l In MAC, typically requires a central authority – E. g. the operating system enforces the control by checking information associated with both the subject and the object to determine whether the subject should access the object l MAC is suitable for military scenarios: – An individual data owner does not decide who has top-secret clearance. – The data owner cannot change the classification of an object from top secret to a lower level. – On military systems, the reference monitor must enforce that objects from one security level cannot be copied into objects of another level, or into a different compartment! l Example MAC model: Bell-La. Padula

Bell-La. Padula Model l The Bell-La. Padula model describes the allowable flows of information in a secure system, and is a formalization of the military security policy. One motivation: Allow for concurrent computation on data at two different security levels – One machine should be able to be used for top-secret and confidential data at the same time – Programs processing top-secret data would be prevented from leaking top -secret data to confidential data, and confidential users would be prevented from accessing top-secret data. The key idea in BLP is to augment DAC with MAC to enforce information flow policies – In addition to an access control matrix, BLP also includes the military security levels – Each subject has a clearance, and each object has a classification – Authorization in the DAC is not sufficient, a subject must also be authorized in the MAC

Bell-La. Padula Model, pg. 2 l Formally, BLP involves a set of subjects S and a set of objects O. – Each subject s and object o have fixed security classes l(s) and l( – Tranquility Principle: Subjects and objects cannot change their sec l There are two principles that characterize the secure flow of informati 1. Simple-Security Property: A subject s may have read access to an obj 2. *-Property: A subject s can write to object o iff l Read access implies a flow from object to subject l Write access implies a flow from subject to object

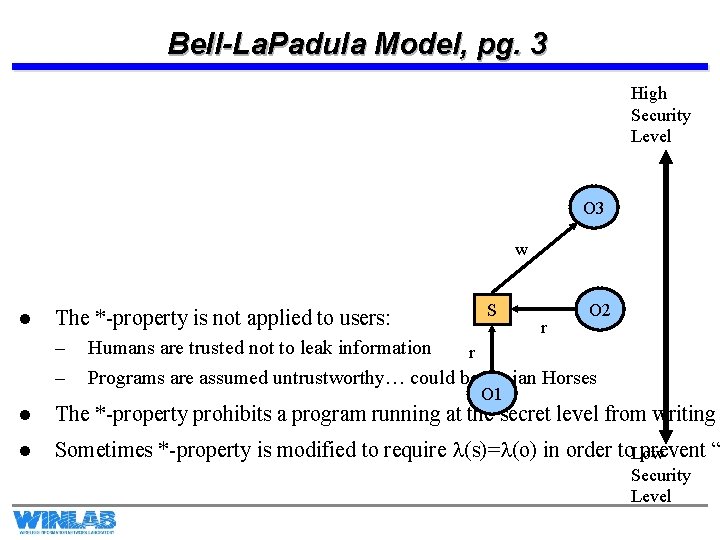

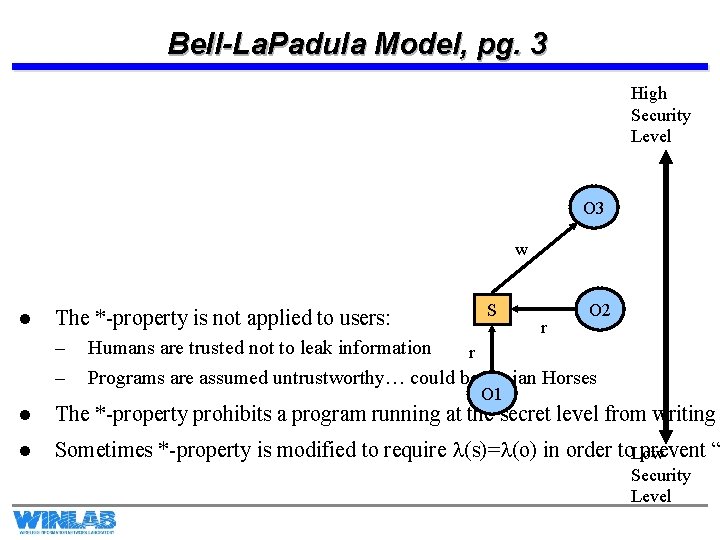

Bell-La. Padula Model, pg. 3 High Security Level O 3 w l The *-property is not applied to users: – – S r O 2 Humans are trusted not to leak information r Programs are assumed untrustworthy… could be Trojan Horses O 1 l The *-property prohibits a program running at the secret level from writing l Sometimes *-property is modified to require l(s)=l(o) in order to. Low prevent “ Security Level

BLP and Trojan Horses l Return to the Trojan Horse problem: – Alice and Bob are secret level users, Eve is an unclassified user – Alice and Bob can have both secret and unclassified subjects (programs) – Eve can only have unclassified subjects – Alice creates secret file X – Simple security prevents Eve from reading X directly – Bob can either have a secret (S-Troy) or an unclassified (U-Troy) Trojan. Horse carrying program – S-Troy: Bob running S-Troy will create Y, which will be a secret file. Eve’s unclassified subjects will not be able to read Y. – U-Troy: Bob running U-Troy won’t be able to read X, and so won’t be able to copy it into Y. l Thus BLP prevents flow between security classes l One problem remains: Covert Channels… but that’s for another lecture…

From BLP to Biba l BLP was concerned with confidentiality– keeping data inaccessible to those withou l The Biba model is the integrity counterpart to BLP – Low-integrity information should not be allowed to flow to high-integrity objec – High-integrity is placed at the top of the lattice and low integrity at the bottom. l Biba’s model principles 1. Simple-Integrity Property: Subject s can read object o iff 2. Integrity *-Property: Subject s can write object o only if l In this sense, Biba is the dual of BLP and there is very little difference between Bib – Both are concerned with information flow in a lattice of security classes

Trusted (Operating) System Design l Operating systems control the interaction between subjects and objects, and mechanisms to enforce this control should be planned for at the design phase of the system l Some design principles: – Least Privilege: Each user and program should operate with the fewest privileges possible (minimizes damage from inadvertent or malicious misuse) – Open Design: The protection mechanisms should be publicly known so as to provide public scrutiny – Multiple Levels of Protection: Access to objects should depend on more than one condition (e. g. password and token) – Minimize Shared Resources: Shared resources provide (covert) means for information flow.

Trusted (Operating) System Design, pg. 2 l Unlike a typical OS, a Trusted OS involves each object being protected by an access control mechanism – Users must pass through an access control layer to use the OS – Another access control layer separates the OS from using program libraries l A trusted OS includes: – User identification and authentication – MAC and DAC – Object reuse protection: When subjects finish using objects, the resources may be released for use by other subjects. Must be careful! Sanitize the object! – Audit mechanisms: Maintain a log of events that have transpired. Efficient use of audit resources is a major problem! – Intrusion detection: Detection mechanisms that allow for the identification of security violations or infiltrations l Trusted Computing Base (TCB): everything in the trusted operating system that enforces a security policy