ABC An IndustrialStrength Academic Synthesis and Verification Tool

ABC: An Industrial-Strength Academic Synthesis and Verification Tool (based on a tutorial given at CAV 2010) Berkeley Verification and Synthesis Research Center UC Berkeley Robert Brayton, Niklas Een, Alan Mishchenko Jiang Long, Sayak Ray, Baruch Sterin Thanks to: NSA, SRC, and industrial sponsors, Actel, Altera, Atrenta, IBM, Intel, Jasper, Magma, Oasys, Real Intent, Synopsys, Tabula, and Verific

Overview What is ABC? l Synthesis/verification synergy l Introduction to AIGs l Representative transformations l Integrated verification flow l Verification example l Future work l 2

A Plethora of ABCs http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Abc l ABC (American Broadcasting Company) l l ABC (Active Body Control) l l In C++, these are generic classes at the base of the inheritance tree; objects of such abstract classes cannot be created… Atanasoff-Berry Computer l l ABC is designed to minimize body roll in corner, accelerating, and braking. The system uses 13 sensors which monitor body movement to supply the computer with information every 10 ms… ABC (Abstract Base Class) l l A television network… The Atanasoff–Berry Computer (ABC) was the first electronic digital computing device. Conceived in 1937, the machine was not programmable, being designed only to solve systems of linear equations. It was successfully tested in 1942. ABC (supposed to mean “as simple as ABC”) l A system for sequential synthesis and verification at Berkeley 3

ABC l l l Started 6 years ago as a replacement for SIS Academic public-domain tool “Industrial-strength” l l l Focuses on efficient implementation Has been employed in commercial offerings of several CAD companies Exploits the synergy between synthesis and verification 4

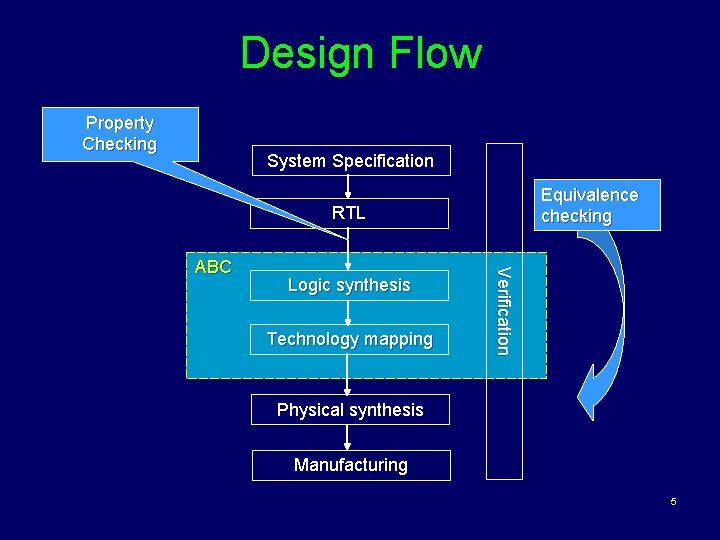

Design Flow Property Checking System Specification Equivalence checking RTL Logic synthesis Technology mapping Verification ABC Physical synthesis Manufacturing 5

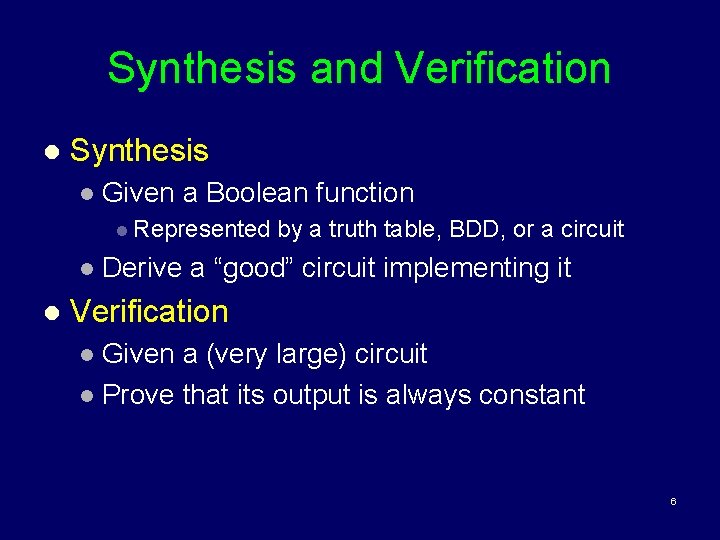

Synthesis and Verification l Synthesis l Given a Boolean function l Represented l Derive l by a truth table, BDD, or a circuit a “good” circuit implementing it Verification l Given a (very large) circuit l Prove that its output is always constant 6

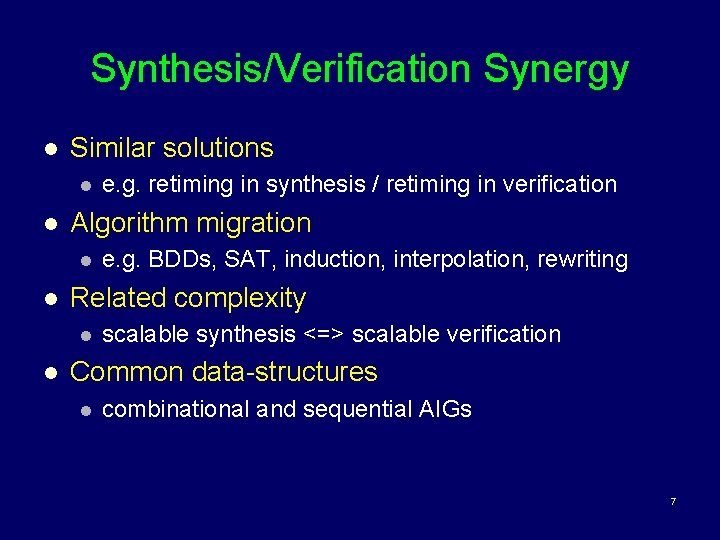

Synthesis/Verification Synergy l Similar solutions l l Algorithm migration l l e. g. BDDs, SAT, induction, interpolation, rewriting Related complexity l l e. g. retiming in synthesis / retiming in verification scalable synthesis <=> scalable verification Common data-structures l combinational and sequential AIGs 7

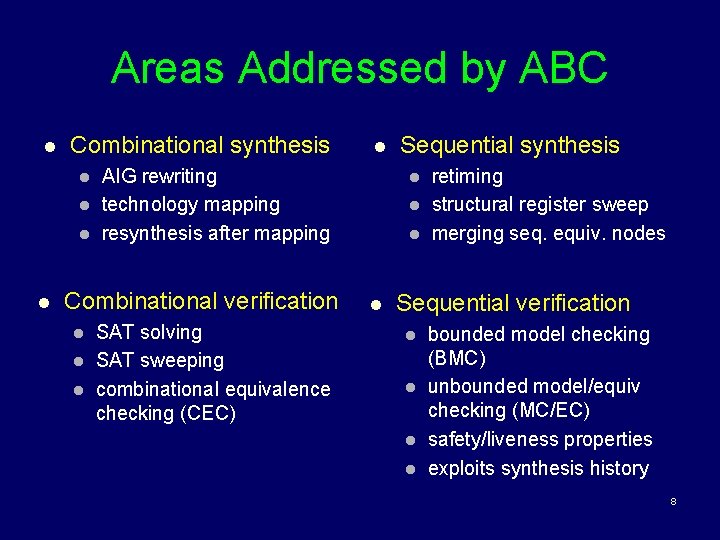

Areas Addressed by ABC l Combinational synthesis l l AIG rewriting technology mapping resynthesis after mapping Combinational verification l l SAT solving SAT sweeping combinational equivalence checking (CEC) Sequential synthesis l l retiming structural register sweep merging seq. equiv. nodes Sequential verification l l bounded model checking (BMC) unbounded model/equiv checking (MC/EC) safety/liveness properties exploits synthesis history 8

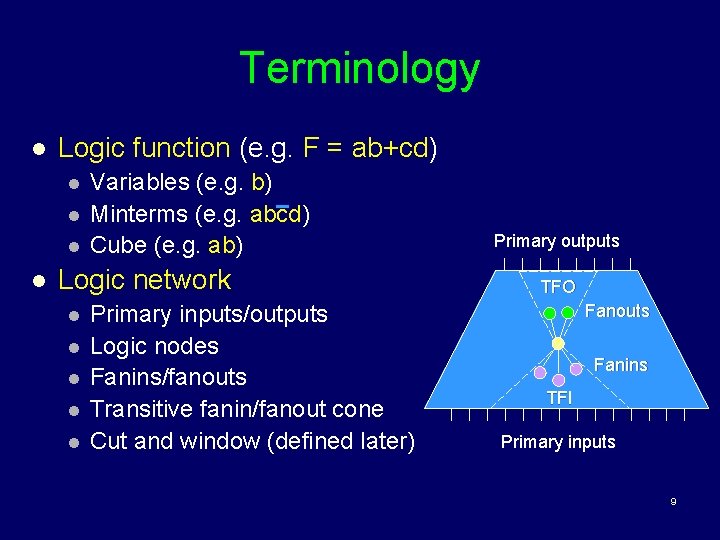

Terminology l Logic function (e. g. F = ab+cd) l l Variables (e. g. b) Minterms (e. g. abcd) Cube (e. g. ab) Logic network l l l Primary inputs/outputs Logic nodes Fanins/fanouts Transitive fanin/fanout cone Cut and window (defined later) Primary outputs TFO Fanouts Fanins TFI Primary inputs 9

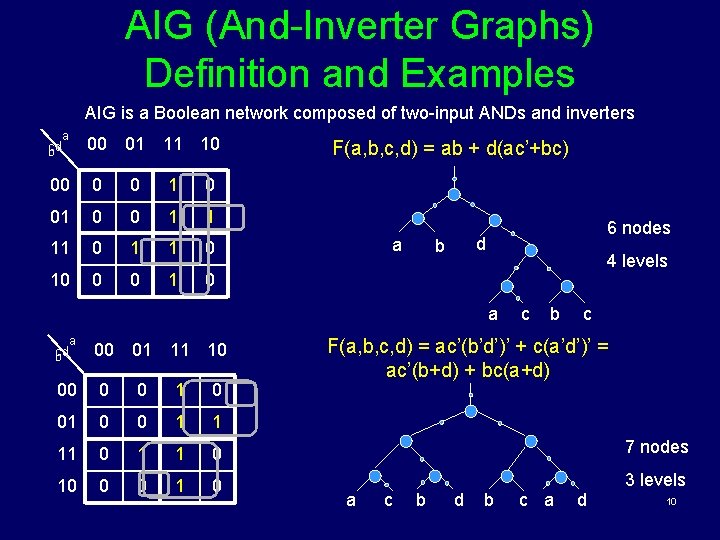

AIG (And-Inverter Graphs) Definition and Examples AIG is a Boolean network composed of two-input ANDs and inverters a cd b 00 01 11 10 00 0 0 1 1 11 0 10 0 0 1 0 F(a, b, c, d) = ab + d(ac’+bc) a 6 nodes d b 4 levels a a cd b 00 01 11 10 c b c F(a, b, c, d) = ac’(b’d’)’ + c(a’d’)’ = ac’(b+d) + bc(a+d) 00 0 0 1 1 11 0 1 1 0 7 nodes 10 0 0 1 0 3 levels a c b d b c a d 10

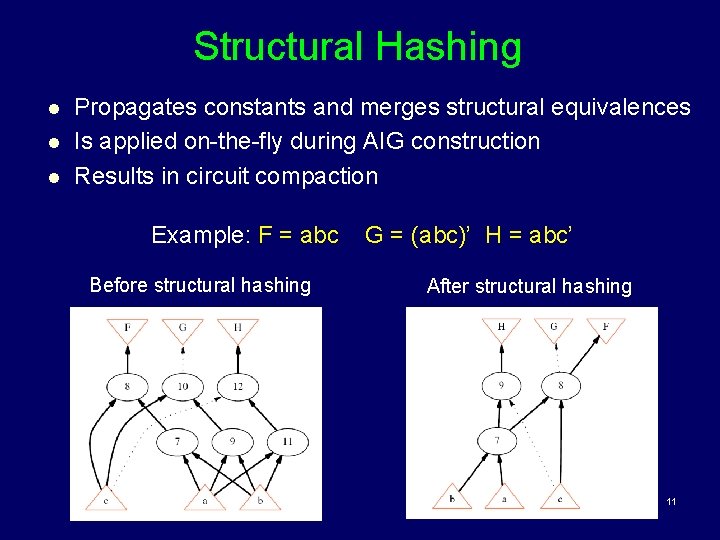

Structural Hashing l l l Propagates constants and merges structural equivalences Is applied on-the-fly during AIG construction Results in circuit compaction Example: F = abc Before structural hashing G = (abc)’ H = abc’ After structural hashing 11

Why AIGs? Same reasons hold for both synthesis and verification l Easy to construct, relatively compact, robust l l Can be efficiently stored on disk l l 1 M AIG ~ 12 Mb RAM 3 -4 bytes / AIG node (1 M AIG ~ 4 Mb file) Unifying representation Used by all the different verification engines l Easy to pass around, duplicate, save l l Compatible with SAT solvers Efficient AIG-to-CNF conversion available l Circuit-based SAT solvers work directly on AIG l “AIGs + simulation + SAT” works well in many cases l 12

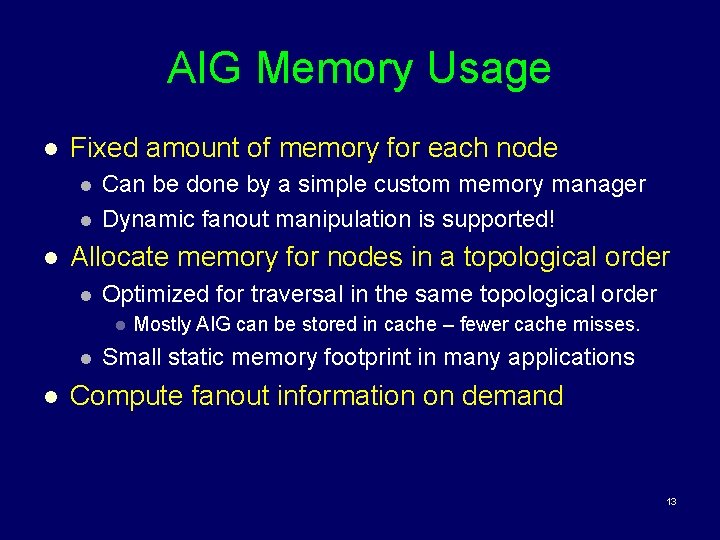

AIG Memory Usage l Fixed amount of memory for each node l l l Can be done by a simple custom memory manager Dynamic fanout manipulation is supported! Allocate memory for nodes in a topological order l Optimized for traversal in the same topological order l l l Mostly AIG can be stored in cache – fewer cache misses. Small static memory footprint in many applications Compute fanout information on demand 13

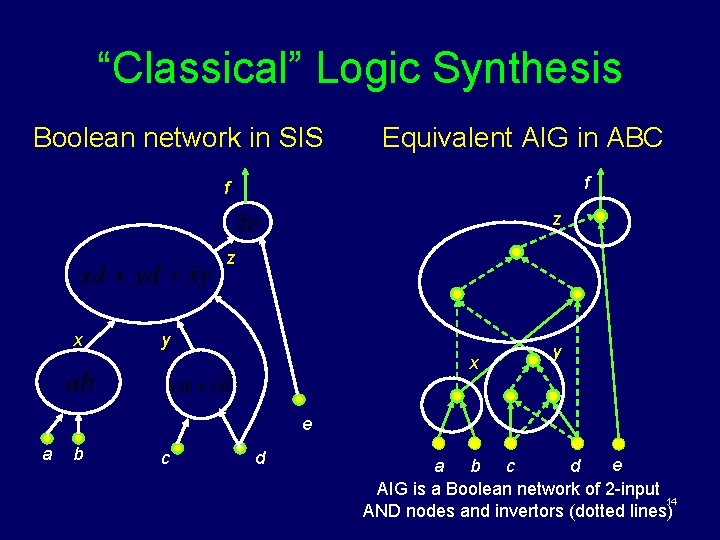

“Classical” Logic Synthesis Boolean network in SIS Equivalent AIG in ABC f f z z x y e a b c d AIG is a Boolean network of 2 -input 14 AND nodes and invertors (dotted lines)

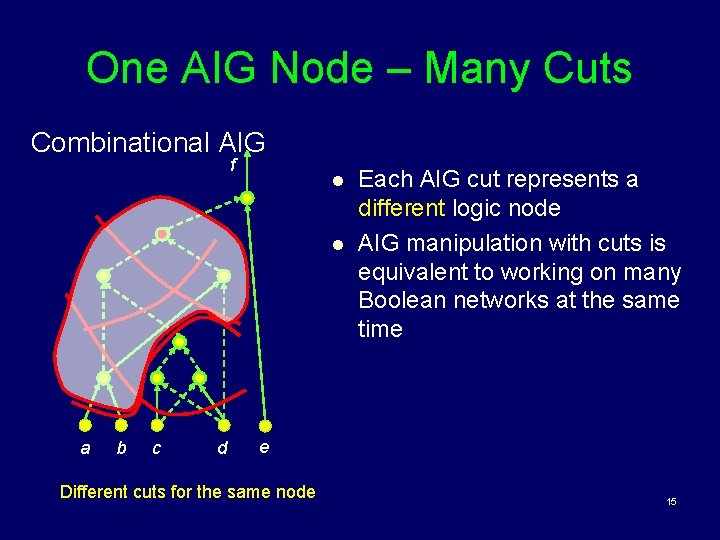

One AIG Node – Many Cuts Combinational AIG f l l a b c d Each AIG cut represents a different logic node AIG manipulation with cuts is equivalent to working on many Boolean networks at the same time e Different cuts for the same node 15

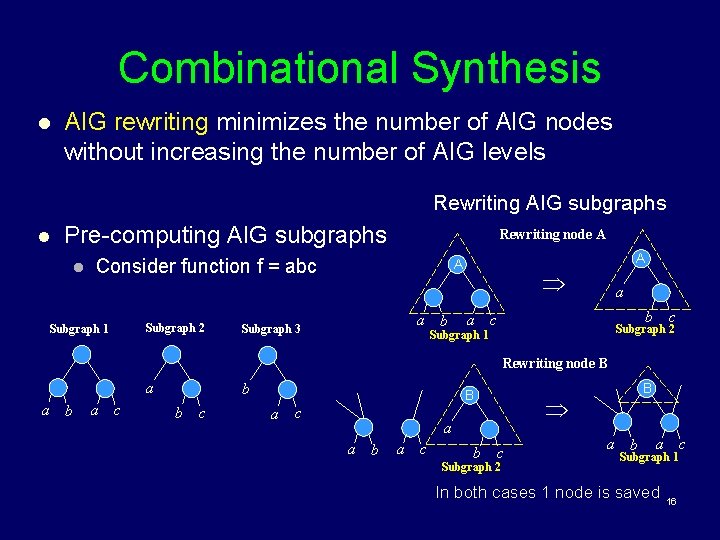

Combinational Synthesis l AIG rewriting minimizes the number of AIG nodes without increasing the number of AIG levels Rewriting AIG subgraphs l Pre-computing AIG subgraphs l Rewriting node A Consider function f = abc Subgraph 1 Subgraph 2 A A a b Subgraph 3 a b a c c Subgraph 2 Subgraph 1 Rewriting node B a a b a c b b c B a c a a b a c b B c Subgraph 2 a b a c Subgraph 1 In both cases 1 node is saved 16

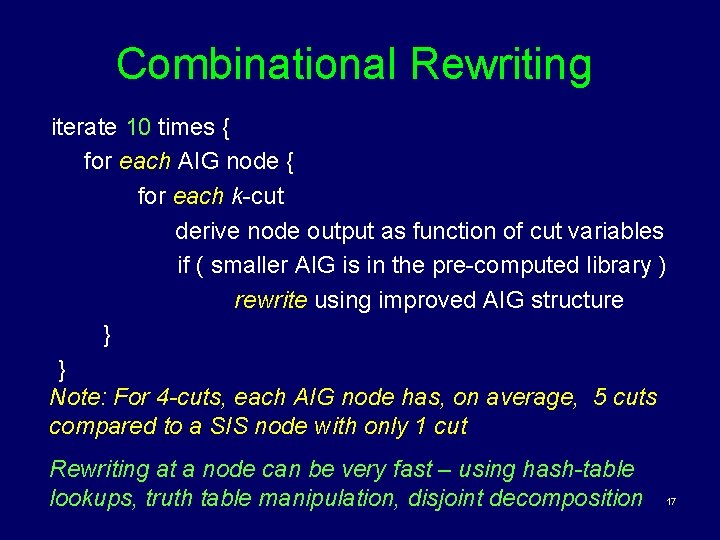

Combinational Rewriting iterate 10 times { for each AIG node { for each k-cut derive node output as function of cut variables if ( smaller AIG is in the pre-computed library ) rewrite using improved AIG structure } } Note: For 4 -cuts, each AIG node has, on average, 5 cuts compared to a SIS node with only 1 cut Rewriting at a node can be very fast – using hash-table lookups, truth table manipulation, disjoint decomposition 17

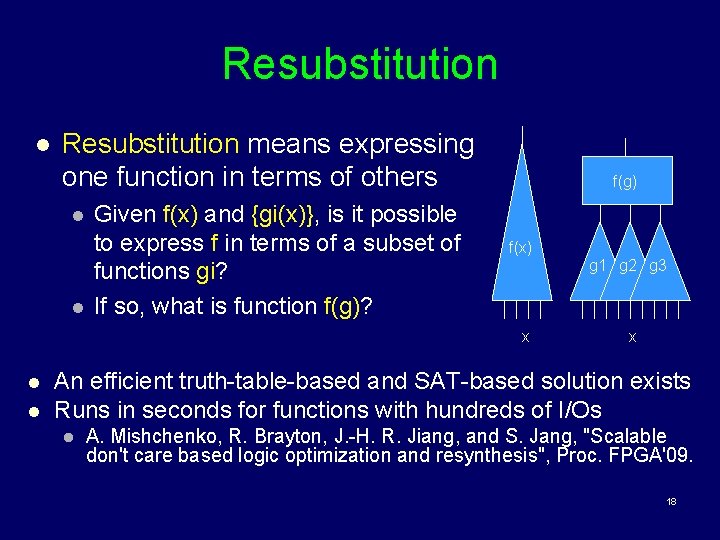

Resubstitution l Resubstitution means expressing one function in terms of others l l Given f(x) and {gi(x)}, is it possible to express f in terms of a subset of functions gi? If so, what is function f(g)? f(g) f(x) g 1 g 2 g 3 x l l x An efficient truth-table-based and SAT-based solution exists Runs in seconds for functions with hundreds of I/Os l A. Mishchenko, R. Brayton, J. -H. R. Jiang, and S. Jang, "Scalable don't care based logic optimization and resynthesis", Proc. FPGA'09. 18

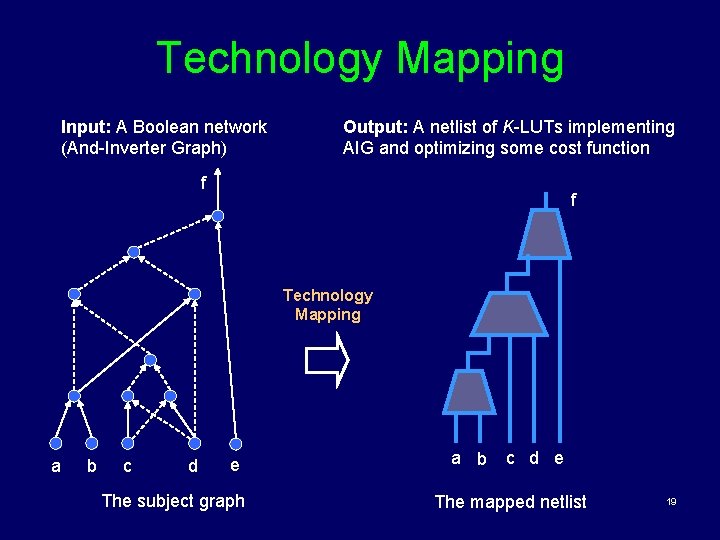

Technology Mapping Input: A Boolean network (And-Inverter Graph) Output: A netlist of K-LUTs implementing AIG and optimizing some cost function f f Technology Mapping a b c d e The subject graph a b c d e The mapped netlist 19

Library Formats for Tech Mapping l GENLIB format l l Simple format used in academic tools For each gate, lists its name, Boolean function, pin names and order, area, pin-to-pin delays, etc http: //www. eecs. berkeley. edu/~alanmi/publications/other/SIS_paper_genlib. pdf l LIBERTY format l l Elaborate format used in industrial tools For each gate, represents all information needed for synthesis, mapping, delay/power computation, etc http: //www. opensourceliberty. org/ l ABC reads both formats but uses only a subset of available information 20

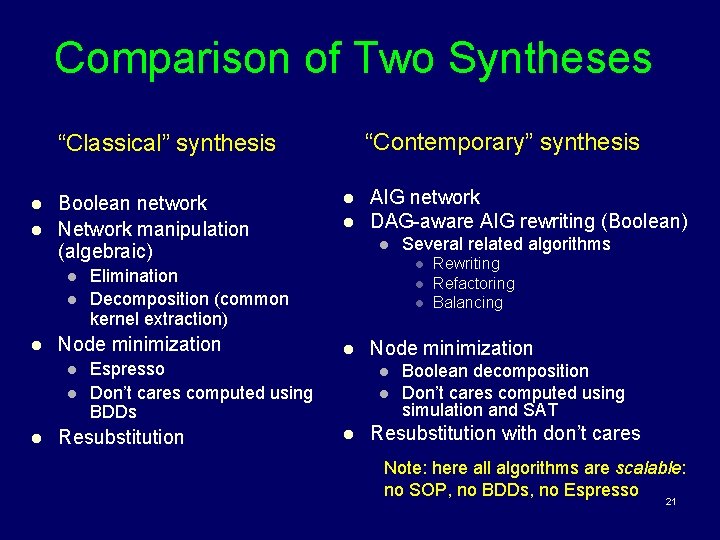

Comparison of Two Syntheses “Contemporary” synthesis “Classical” synthesis l l Boolean network Network manipulation (algebraic) l l l AIG network DAG-aware AIG rewriting (Boolean) l Espresso Don’t cares computed using BDDs Resubstitution Several related algorithms l l Elimination Decomposition (common kernel extraction) Node minimization l l l Rewriting Refactoring Balancing Boolean decomposition Don’t cares computed using simulation and SAT Resubstitution with don’t cares Note: here all algorithms are scalable: no SOP, no BDDs, no Espresso 21

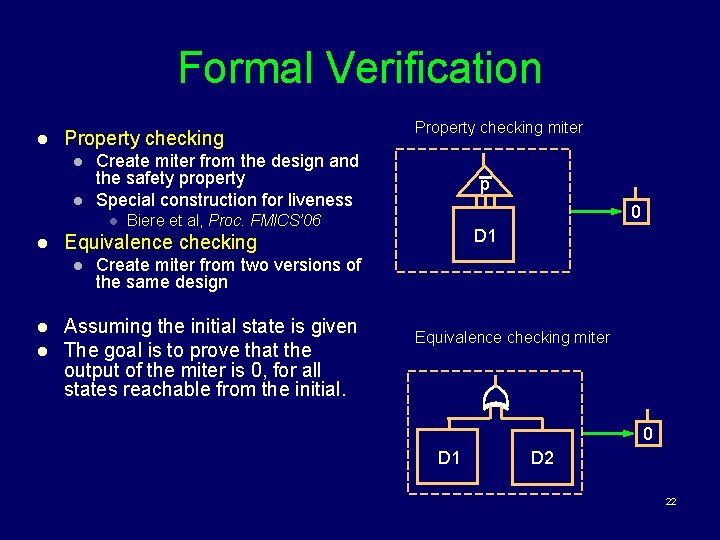

Formal Verification l Property checking l l Create miter from the design and the safety property Special construction for liveness l l l p 0 Biere et al, Proc. FMICS’ 06 D 1 Equivalence checking l l Property checking miter Create miter from two versions of the same design Assuming the initial state is given The goal is to prove that the output of the miter is 0, for all states reachable from the initial. Equivalence checking miter 0 D 1 D 2 22

Outcomes of Verification l Success l l Failure l l The property holds in all reachable states A finite-length counter-example (CEX) is found Undecided l A limit on resources (such as runtime) is reached 23

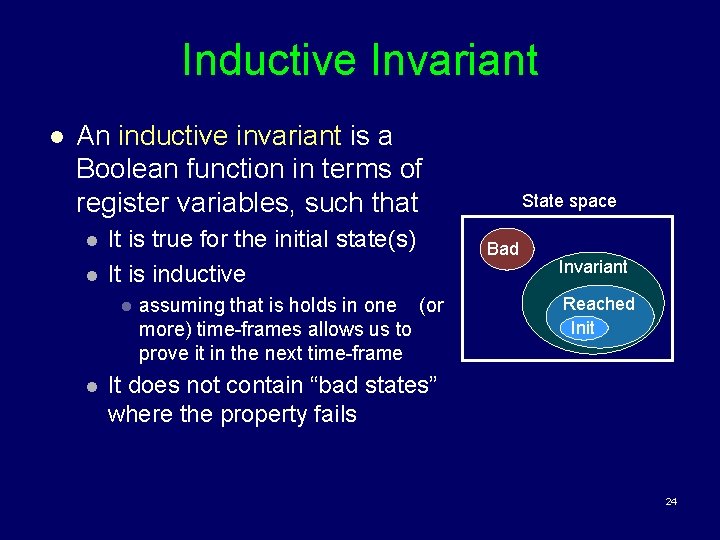

Inductive Invariant l An inductive invariant is a Boolean function in terms of register variables, such that l l It is true for the initial state(s) It is inductive l l assuming that is holds in one (or more) time-frames allows us to prove it in the next time-frame State space Bad Invariant Reached Init It does not contain “bad states” where the property fails 24

Inductive Invariant (cont. ) l l It does not matter how inductive invariant is derived! If it is available in any form (as a circuit, BDD or CNF), it can be checked for correctness using a third-party tool l This way, verification proof can be certified Comment 1: If the property is true, the set of all reachable states is an inductive invariant Comment 2: In practice, computing the set of all reachable states is often impossible. In such cases, an inductive invariant is an overapproximation of reachable states. 25

Verification Engines l Bug-hunters l l Provers l l l random simulation bounded model checking (BMC) hybrids of the above two (“semi-formal”) K-step induction, with or without uniqueness constraints BDDs (exact reachability) Interpolation (over-approximate reachability) Property directed reachability (over-approximate reachability) Transformers l l l Combinational synthesis Reparameterization Retiming 26

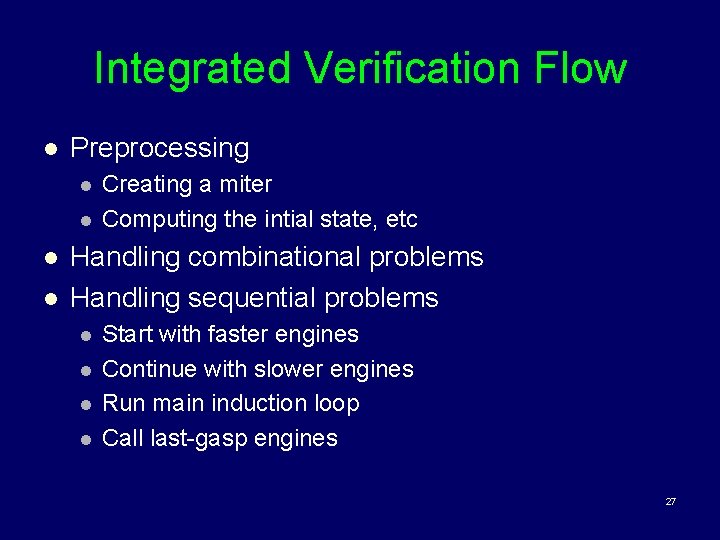

Integrated Verification Flow l Preprocessing l l Creating a miter Computing the intial state, etc Handling combinational problems Handling sequential problems l l Start with faster engines Continue with slower engines Run main induction loop Call last-gasp engines 27

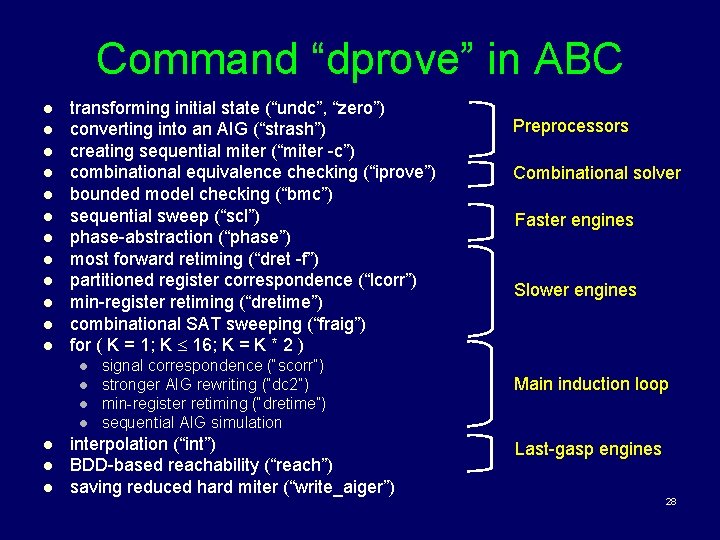

Command “dprove” in ABC l l l transforming initial state (“undc”, “zero”) converting into an AIG (“strash”) creating sequential miter (“miter -c”) combinational equivalence checking (“iprove”) bounded model checking (“bmc”) sequential sweep (“scl”) phase-abstraction (“phase”) most forward retiming (“dret -f”) partitioned register correspondence (“lcorr”) min-register retiming (“dretime”) combinational SAT sweeping (“fraig”) for ( K = 1; K 16; K = K * 2 ) l l l l signal correspondence (“scorr”) stronger AIG rewriting (“dc 2”) min-register retiming (“dretime”) sequential AIG simulation interpolation (“int”) BDD-based reachability (“reach”) saving reduced hard miter (“write_aiger”) Preprocessors Combinational solver Faster engines Slower engines Main induction loop Last-gasp engines 28

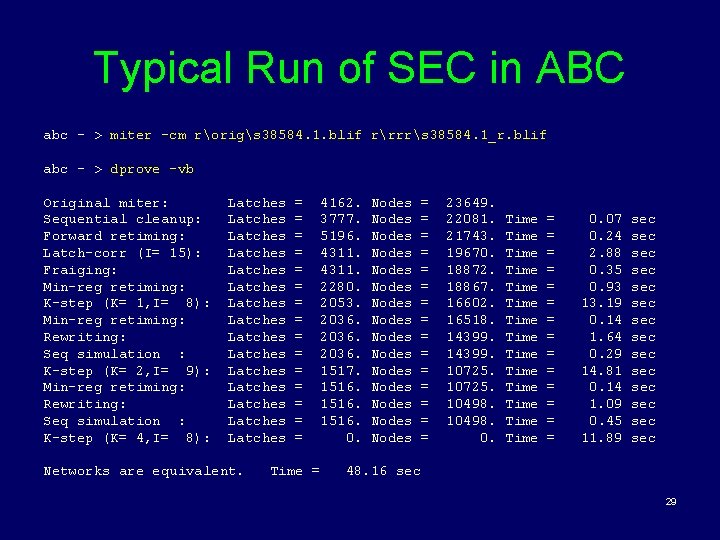

Typical Run of SEC in ABC abc - > miter –cm rorigs 38584. 1. blif rrrrs 38584. 1_r. blif abc - > dprove –vb Original miter: Sequential cleanup: Forward retiming: Latch-corr (I= 15): Fraiging: Min-reg retiming: K-step (K= 1, I= 8): Min-reg retiming: Rewriting: Seq simulation : K-step (K= 2, I= 9): Min-reg retiming: Rewriting: Seq simulation : K-step (K= 4, I= 8): Latches Latches Latches Latches Networks are equivalent. = = = = 4162. 3777. 5196. 4311. 2280. 2053. 2036. 1517. 1516. 0. Time = Nodes Nodes Nodes Nodes = = = = 23649. 22081. 21743. 19670. 18872. 18867. 16602. 16518. 14399. 10725. 10498. 0. Time Time Time Time = = = = 0. 07 0. 24 2. 88 0. 35 0. 93 13. 19 0. 14 1. 64 0. 29 14. 81 0. 14 1. 09 0. 45 11. 89 sec sec sec sec 48. 16 sec 29

Combinational Equivalence Checking (command ‘cec’) Naïve approach • Build output miter – call SAT l works well for many easy problems D 1 D 2 ? SAT-2 D ? C SAT-1 A B Proving internal equivalences in a topological order Better approach - SAT sweeping • based on incremental SAT solving • detect possibly equivalent nodes using simulation • candidate constant nodes • candidate equivalent nodes • run SAT on the intermediate miters in a topological order 30 • refine candidates using counterexamples

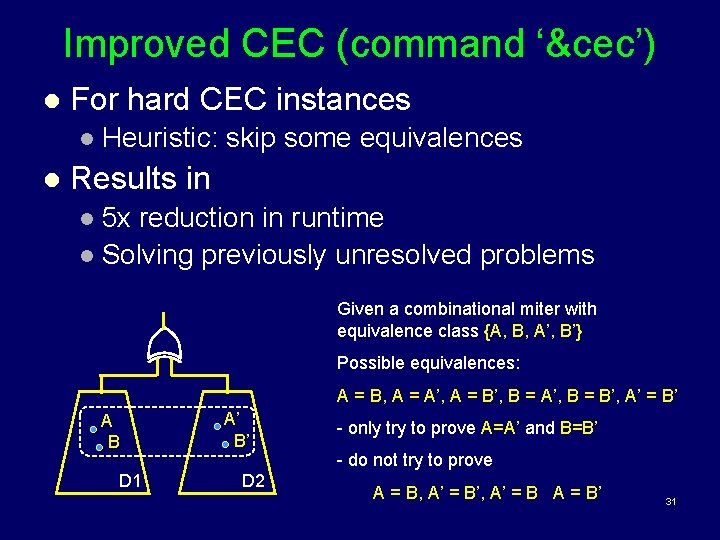

Improved CEC (command ‘&cec’) l For hard CEC instances l Heuristic: l skip some equivalences Results in l 5 x reduction in runtime l Solving previously unresolved problems Given a combinational miter with equivalence class {A, B, A’, B’} Possible equivalences: A = B, A = A’, A = B’, B = A’, B = B’, A’ = B’ A B D 1 A’ B’ D 2 - only try to prove A=A’ and B=B’ - do not try to prove A = B, A’ = B’, A’ = B A = B’ 31

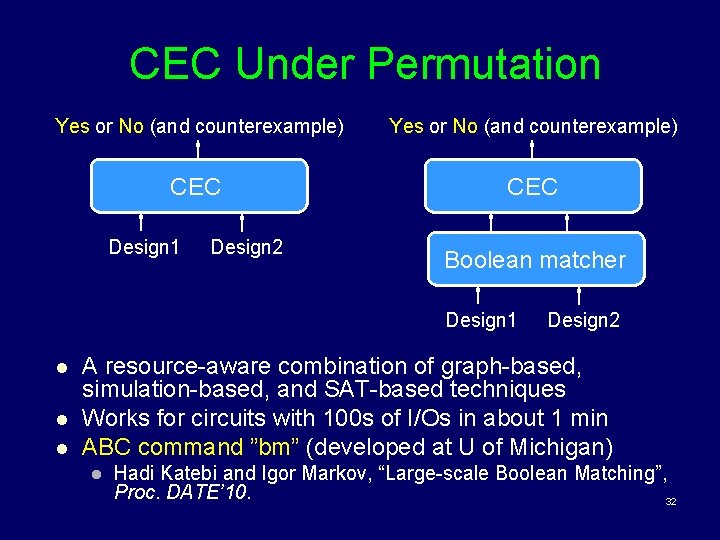

CEC Under Permutation Yes or No (and counterexample) CEC Design 1 Design 2 Boolean matcher Design 1 l l l Design 2 A resource-aware combination of graph-based, simulation-based, and SAT-based techniques Works for circuits with 100 s of I/Os in about 1 min ABC command ”bm” (developed at U of Michigan) l Hadi Katebi and Igor Markov, “Large-scale Boolean Matching”, Proc. DATE’ 10. 32

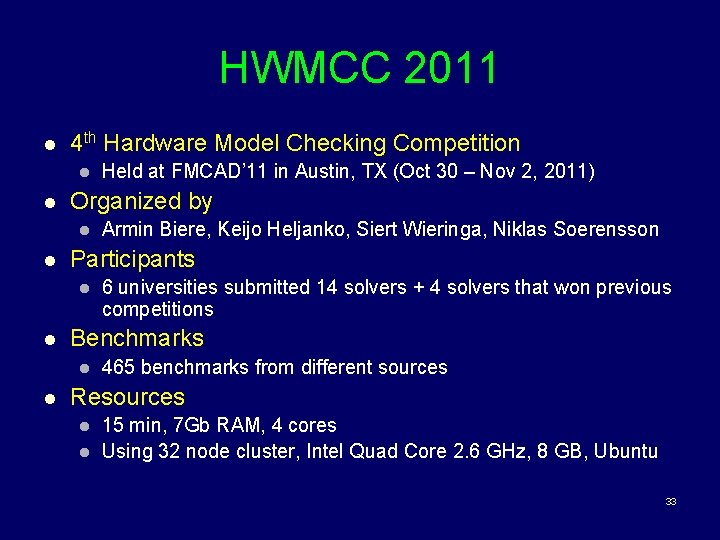

HWMCC 2011 l 4 th Hardware Model Checking Competition l l Organized by l l 6 universities submitted 14 solvers + 4 solvers that won previous competitions Benchmarks l l Armin Biere, Keijo Heljanko, Siert Wieringa, Niklas Soerensson Participants l l Held at FMCAD’ 11 in Austin, TX (Oct 30 – Nov 2, 2011) 465 benchmarks from different sources Resources l l 15 min, 7 Gb RAM, 4 cores Using 32 node cluster, Intel Quad Core 2. 6 GHz, 8 GB, Ubuntu 33

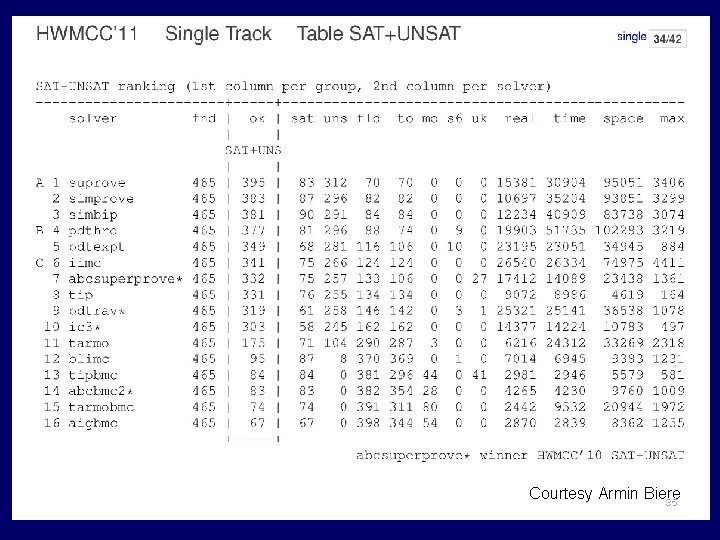

Courtesy Armin Biere 34

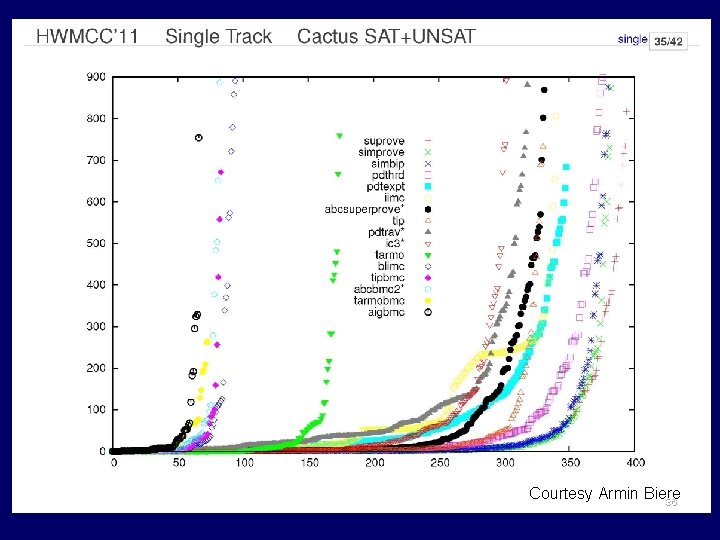

Courtesy Armin Biere 35

Courtesy Armin Biere 36

Future Work l Exploring new directions l l Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) Software verification Using concurrency, etc Improving bit-level engines l l l Application-specific SAT solvers A modern BDD package Improved sequential logic simulators l l l combining random, guided and symbolic simulation Improved abstraction refinement … and may be a new engine or two 37

To Learn More Visit BVSRC webpage www. bvsrc. org l Read recent papers l http: //www. eecs. berkeley. edu/~alanmi/publications l Send email l l alanmi@eecs. berkeley. edu brayton@eecs. berkeley. edu 38

39

- Slides: 39