A Time to Dance by Padma Venkatraman Summary

A Time to Dance by Padma Venkatraman

Summary of A Time to Dance Padma Venkatraman’s inspiring story of a young girl’s struggle to regain her passion and find a new peace is told lyrically through verse that captures the beauty and mystery of India and the ancient bharatanatyam dance form. This is a stunning novel about spiritual awakening, the power of art, and above all, the courage and resilience of the human spirit. Veda, a classical dance prodigy in India, lives and breathes dance—so when an accident leaves her a below-knee amputee, her dreams are shattered. For a girl who’s grown used to receiving applause for her dance prowess and flexibility, adjusting to a prosthetic leg is painful and humbling. But Veda refuses to let her disability rob her of her dreams, and she starts all over again, taking beginner classes with the youngest dancers. Then Veda meets Govinda, a young man who approaches dance as a spiritual pursuit. As their relationship deepens, Veda reconnects with the world around her, and begins to discover who she is and what dance truly means to her.

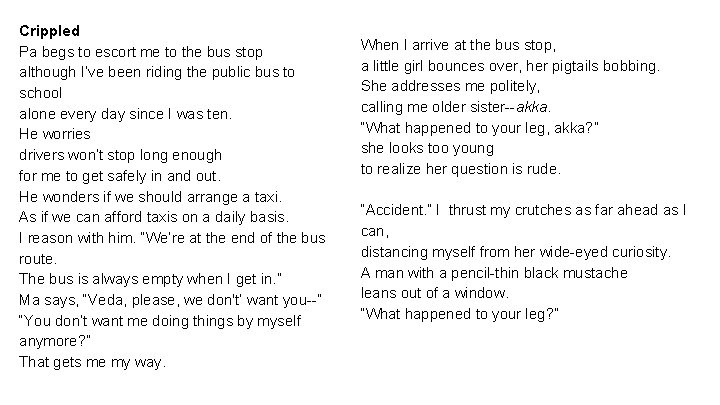

Crippled Pa begs to escort me to the bus stop although I’ve been riding the public bus to school alone every day since I was ten. He worries drivers won’t stop long enough for me to get safely in and out. He wonders if we should arrange a taxi. As if we can afford taxis on a daily basis. I reason with him. “We’re at the end of the bus route. The bus is always empty when I get in. ” Ma says, “Veda, please, we don't’ want you--” “You don’t want me doing things by myself anymore? ” That gets me my way. When I arrive at the bus stop, a little girl bounces over, her pigtails bobbing. She addresses me politely, calling me older sister--akka. “What happened to your leg, akka? ” she looks too young to realize her question is rude. “Accident. ” I thrust my crutches as far ahead as I can, distancing myself from her wide-eyed curiosity. A man with a pencil-thin black mustache leans out of a window. “What happened to your leg? ”

My throat hurts as if a thorn’s stuck in it and I ignore him. The bus’s steps look steeper than I remember. I hesitate on the ground, trying to picture Jim standing next to me, his cheerful voice teaching me how to climb on crutches. And old woman greets me from her usual place in front, “Girl? How did you lose your leg? An accident? Or a disease? ” “She’s not telling, ” the man says. “So rude she is being. In our day we always answered our elders. ” The woman sighs. “Very true. ” As fast as I can, I get away from them, to the back of the bus. Stare out the window, sensing innumerable eyes staring at me. Someone taps me on the shoulder. The khaki-clad bus conductor. He’s seen me in his bus nearly every school day. I wait for him to ask the question. He only says, “Good to have you back. ” Hands me my ticket and moves on. I want to hug him. The bus jerks onto the road.

A temple elephant lumbering along in a procession obstructs traffic. I’m thankful it slows the bus down at least for a short while. Soon the bus is hurtling madly through crowded streets. I press back into my seat, clutching my schoolbag. Sweat plasters my skirt to my thighs. My stop feels light-years away. By the time we arrive, the bus is packed. “Let the lame girl through, ” a lady shouts as I struggle to push through the crowd. She sounds as though she’s trying to be helpful. My face flushes hot with shame as I navigate carefully down the steep steps and out of the bus.

Looks Clunking along the bleak school corridors, I must look as asymmetric as a heron balancing on one leg. I wish it wouldn’t take Jim so long to make my prosthesis. I hate announcing my arrival on crutches --stomp, clomp, stomp, clomp-loud enough to make every head turn in my direction. When lessons are over everyone pours out onto the sports field. “You could coach us, Veda. Please? Come? ” Chandra pleads. So I go. The other girls from the cricket team gather around me. A few mumble that they’re sorry, their nervous eyes politely stuck to my face, wary of accidentally straying too low and catching a glimpse of the space beneath my right knee. Some welcome me back in extra-bright voices, saying it’s nice I’m back though they hardly know me. Silent, shy, following Chandra, at school, I was her shadow. Only at dance did I shine in my own light.

Listlessly I listen to girls whack the red cork ball with willow bats. Mekha, a vicious girl, who plays so well Candra’s forced to keep her on the team, walks past me. “Hey, Veda, I was pretty lame today. Wasn’t I? ” She giggles. Her twin, Meghna, peals with laughter. As they walk away, I hear Mehka say, “Veda’s so sensitive! Are we supposed to stop using certain words because she’s handicapped? Should we give cricket stumps a new name now that she has a stump? ” The girls fall on each other, laughing some more, and their taunts echo loudly in my head long after I leave the field. (Page 81 -85)

Extension What is the effect of first person narration in these poems? How would you characterize the narrator? Compare and contrast the different responses Veda gets from the people she interacts with. Why do you think the author included these interactions? Describe the setting. Find an example of onomatopoeia and simile. “Silent, shy, following Chandra, / at school, I was her shadow. / Only at dance did I shine in my own light. ” What do you think this reveals about what might happen later in the novel?

- Slides: 9