A Theological Reflection on Language Shift and Identity

- Slides: 26

A Theological Reflection on Language Shift and Identity Dr Maik Gibson SIL International & School of Language & Scripture, Moorlands College

How are Language and Identity Linked? “If someone doesn’t speak Kikuyu, can they be considered a Kikuyu? ”

An important question for those working with minority communities Does language shift endanger identity? If so, what to do about it? Rather than starting with current positions, let’s look at Biblical material that is relevant

A Biblical Overview (of Language Shift) 1) The Patriarchs 2) Post-exilic Period – with a focus on Nehemiah 13 3) New Testament Times

The Patriarchs: A New Identity – and a New Language? WARNING – this section includes (hopefully informed) speculation Genesis 31: 47 “Laban called it Jegar Sahadutha, but Jacob called it Galeed”

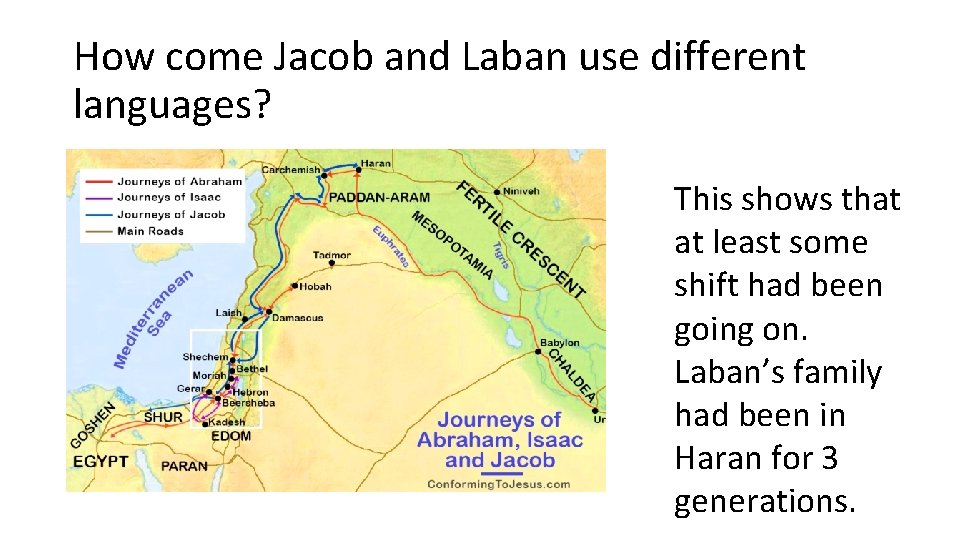

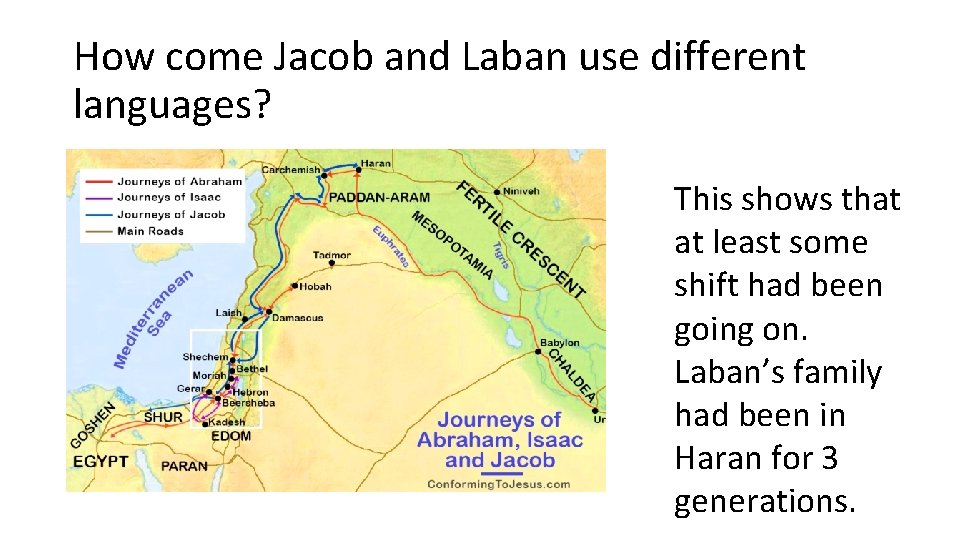

How come Jacob and Laban use different languages? This shows that at least some shift had been going on. Laban’s family had been in Haran for 3 generations.

So it seems that Abram and his ancestors were not Hebrew speakers Hebrew is closely related to other languages of Canaan, not of ‘Chaldea’ Abram’s forebears did not have clearly Hebrew names The languages of Mesopotamia are Eastern Semitic, those of Canaan North-West Semitic.

So was the shift to Hebrew part of the formation of Hebrew/Israelite identity?

Maintaining Identity: Resisting Language Shift “Moreover, in those days I saw men of Judah who had married women from Ashdod, Ammon and Moab. Half of their children spoke the language of Ashdod or the language of one of the other peoples, and did not know how to speak the language of Judah [Yehudit]. ” Nehemiah 13: 23, 24 (NIVUK)

Maintaining Identity: Resisting Language Shift “Moreover, in those days I saw men of Judah who had married women from Ashdod, Ammon and Moab. Half of their children spoke the language of Ashdod or the language of one of the other peoples, and did not know how to speak the language of Judah [Yehudit]. ” Nehemiah 13: 23, 24 (NIVUK) - The first Biblical account of an EGIDS assessment: Hebrew at 6 b

Nehemiah’s Primary Concern was not Language • Cultural revitalization (Tollefson & Williamson 1992) • Motivated by a resistance to idolatry (Venter 2018) • Language was a sign of the problem, not the primary problem itself • The story does show that Hebrew was being lost by some as a vernacular in 5 th century BC – this loss may have been impeded before it was too late. • What languages did the children play in? Could they understand each other? Did they live separate lives?

Some time later, the Jews shift their vernacular • When is a bone of much contention, largely irrelevant to our purposes here. • Occurs in the background, and apart from the story of Nehemiah, there is no direct comment on the shift. Jesus is recorded using Aramaic with little comment on the language.

In Jesus’ time • Jesus is recorded speaking Aramaic – consensus is that this was the language of the Jewish community in Galilee • Hebrew Bible had been translated into Greek (Septuagint) and Aramaic (Targum) at this point – enabling the practice of the law for those not fluent in Hebrew. • Jewish identity more related to practice than language. • The language shift had not led to idolatry, nor loss of identity.

At Pentecost The Jews from the diaspora heard the disciples: “each in our own language in which we were born” (Acts 2: 8, KJV) Strong implication that their home language had shifted to Persian, Aramaic, Greek or Arabic, and probably others.

A Summary of Language Shift in the Bible • The period of the patriarchs, which involves a shift of the language from what was spoken in Ur to what we now call the Hebrew language. It could be argued that this shift (very much in the background of the narrative) was consistent with a new identity as those devoted to the God of Israel. • The initial post-exilic period, specifically the period of Nehemiah, where we see the one instance of resistance to incipient language shift, at a time of cultural renewal, when Jewish identity was at risk, and was being reinforced. The shift is seen as a consequence of a dilution of identity, rather than as its cause. Note that this was before any translation of the Scriptures, so those who knew no Hebrew would not have the direct information to know who to keep the law. • By New Testament times, the vernacular of Galilee at least had shifted to Aramaic, and the vernacular of many diasporic Jewish communities had also shifted to one of the languages spoken in the region. This is not seen in any way as diminishing their Jewish identity – it would seem that the close link between vernacular language and identity that existed at the time of Nehemiah had been weakened.

Two Opposite Views on Language Shift 1) Ethically Neutral Language shift is a personal decision, motivated by the perceived benefits of each available language. So a community’s move to another language reflects an aggregate of personal rational choices – we should not be concerned (at least, on the social level). 2) A Sign of Power Imbalances Language shift goes in directions which reflect power imbalances between peoples, and as such, any account which does not see this as the fundamental factor, influencing the choices of marginalised peoples, is deficient. It should be resisted as a matter of justice.

Language Shift and Trauma Hallet et al. (2007) show that in some indigenous communities in Canada, completed communal shift to English correlates more highly with suicide rates (around six times higher) than any other factor. Similar findings in Australia with reference to drug and alcohol problems. Language loss associated with trauma in these cases. Lack of evidence for other places - these are particular cases where English is not seen a satisfactory at the identity level. African urban elites are more likely to have shifted than their rural cousins - not an example of marginalization in this case?

Is either view compatible with the Bible? The Bible does not seem to support a strong version of either view – language shift can matter, and be a reason for communal action (Nehemiah), especially where there is a perceived threat to identity. But in other circumstances (perhaps when the identity is secured through other means than language? ) a shift of vernacular need not undermine the cherished identity.

This makes things more complicated! We do not then have a one-size-fits-all model of what to do about language shift – neither turning a blind eye, nor trying to ‘rescue’ a language at all costs. The Sustainable Use Model (SUM) (Lewis and Simons 2016) discusses realistic options for a community, and measures to achieve these ends.

SUM: Options for a community 1) Maintain the language at its current level (obviously not realistic where the language is currently shifting) 2) Move it to a more secure future by first ensuring continued oral transmission, and then developing literacy – activities that those of us in SIL are happiest helping with 3) More uncomfortably for us, helping prepare the community for a ‘soft landing’ (Lewis and Simons 2016: 213, 243), where the language shift is allowed to take its course, but the community will still be able to use some level of knowledge of the language in a way symbolic of their identity.

And if a Community’s Language is Shifting? • A (Biblical? ) view where we neither see language shift as of no consequence, nor as the sole expression of identity opens up the door to genuine conversation. • It seems that the Sustainable Use Model is in tune with this position, meaning that tools such as the Guide for Planning the Use of Our Language and The Language and Identity Journey are useful ways forward of engaging with communities whose languages may be shifting.

To Conclude Language is one of the most important components of identity, but not always an essential one. It is by recognising this that we can respect the uniqueness of each community without prescribing what should be done, and enter into genuine conversations with the communities with whom we seek to partner.

References cited in the presentation Hallett, Darcy, Michael J. Chandler and Christopher E. Lalonde. (2007). “Aboriginal language knowledge and youth suicide”. Cognitive Development , 22 : 3, July- September 2007, 392 -399. Hanawalt, C, B. Varenkamp, C. Lahn, and D. Eberhard. (2016). A guide for planning the future of our language. Dallas, TX: SIL International. https: //www. sil. org/guide-planning-future-our-language. The Language & Identity Journey (2020) https: //sites. google. com/sil. org/thelanguageidentityjourney/the-journey Lewis, M. Paul, and Gary F. Simons. (2016). Sustaining language use: Perspectives on community-based language development. SIL International Publications in Ethnography 42. Dallas, TX https: //leanpub. com/sustaininglanguageuse Tollefson, K. D. & Williamson, H. G. M. , (1992). ‘Nehemiah as cultural revitalization: An anthropological perspective’, in J. C. Exum (ed. ), The historical books. A Sheffield reader , pp. 322– 348, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield Venter, P. M. , (2018) ‘The dissolving of marriages in Ezra 9– 10 and Nehemiah 13 revisited’, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74(4), a 4854. https: //doi. org/10. 4102/hts. v 74 i 4. 4854