A pie that cant be cut fairly Walter

A pie that can’t be cut fairly Walter Stromquist Swarthmore College mail@walterstromquist. com Fair Division Seminar Dagstuhl, Deutschland June 26, 2007 (last slide added 8/21/07)

Cake cutting as a metaphor A cake is cut by n-1 cuts for n players. Players’ preferences are represented by nonatomic measures. Early results: 1980: There is always an envy-free division. (Best current proof: Follow Francis Su’s argument based on Sperner’s Lemma, 1999) 1993 (Gale): Every envy-free division is undominated ( = efficient = Pareto optimal maximal ) So: In this model, there is always a division that is both envy free and undominated.

Cake-cutting with measurable pieces Pieces need not be intervals; they can be any measurable sets. Julius Barbanel told us about Weller’s Theorem: There is always a division that is both envy free and undominated. ( Where have we seen Kakutani’s fixed point theorem before ? )

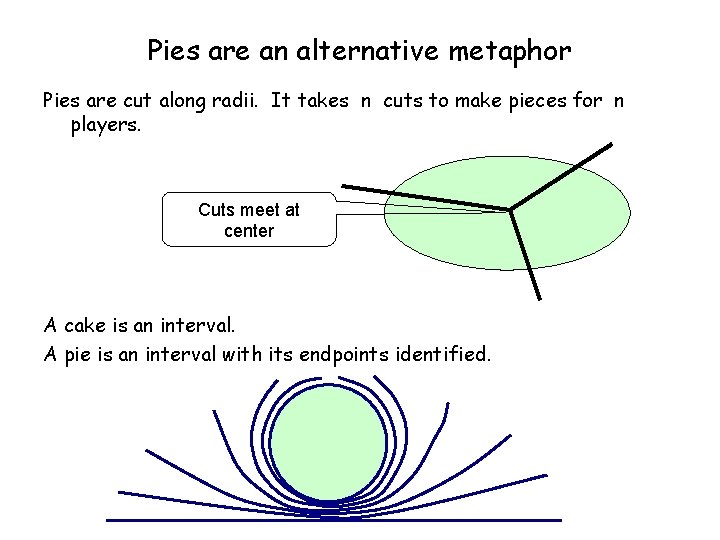

Pies are an alternative metaphor Pies are cut along radii. It takes n cuts to make pieces for n players. Cuts meet at center A cake is an interval. A pie is an interval with its endpoints identified.

Can pies be cut fairly? Are there envy-free divisions? YES. Many of them. Cut the pie anywhere, and then treat it as a cake. Are envy-free divisions necessarily undominated (like for cakes) ? NO. Must there be even ONE division that is both envy-free and undominated? (Gale, 1993) Today’s answer: NO.

Examples emerge from failed proofs Failed proof that there IS an envy-free, undominated allocation: Call the players A, B, C. Call their measures v A, v. B, v. C. Given a division PA, PB, PC, define: The values vector is ( v. A(PA), v. B(PB), v. C(PC) ). (The possible values vectors are the IPS. ) The sum is v. A(PA) + v. B(PB) + v. C(PC). The proportions vector is ( v. A(PA)/sum, v. B(PB)/sum, v. C(PC)/sum). The possible proportions vectors form a simplex.

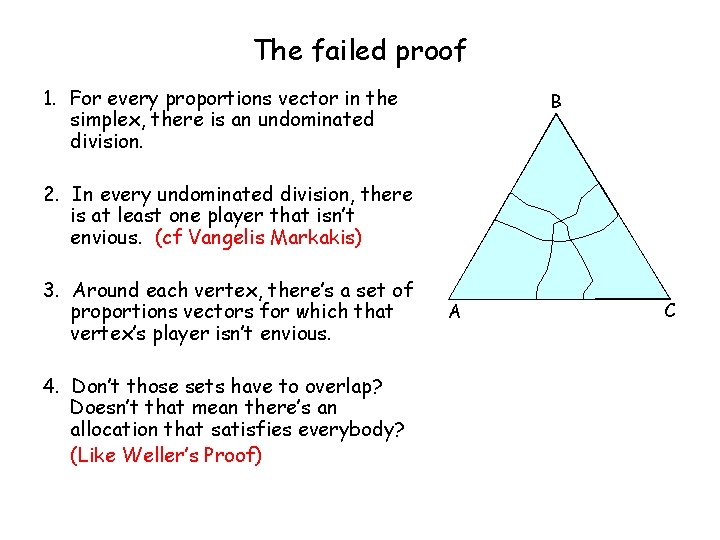

The failed proof 1. For every proportions vector in the simplex, there is an undominated division. B 2. In every undominated division, there is at least one player that isn’t envious. (cf Vangelis Markakis) 3. Around each vertex, there’s a set of proportions vectors for which that vertex’s player isn’t envious. 4. Don’t those sets have to overlap? Doesn’t that mean there’s an allocation that satisfies everybody? (Like Weller’s Proof) A C

The failed proof NO! The sets can be made to overlap. But for that proportions vector, there may be TWO undominated allocations, each satisfying different sets of players. Lesson for a counterexample: There must be at least one instance of a proportions vector with two or more (tied) undominated allocations.

![The example We’ll represent the pie as the interval [ 0, 18 ] with The example We’ll represent the pie as the interval [ 0, 18 ] with](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/dbf0795b4f40d0070f3bccbc9e4a8111/image-9.jpg)

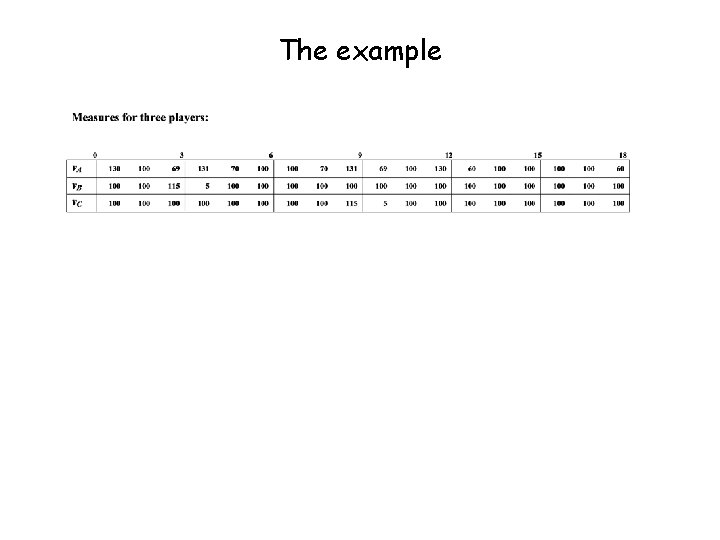

The example We’ll represent the pie as the interval [ 0, 18 ] with the endpoints identified. By the sectors we mean the intervals [0, 1], [1, 2], …, [17, 18]. The players are still A, B, C. We’ll specify the value of each sector to each player. Each player’s measure is uniform over each sector.

The example

- Slides: 10