A new agenda for cocreating public services Overview

A new agenda for co-creating public services

Overview Co. SIE Pilots Conceptualising co-creation • Co-production and co-creation • Strengths and capabilities Implementing co-creation • New roles for front-line workers • Re-thinking risk • Re-designing organisations and systems • Technology Beyond piloting co-creation • Evaluating • Scaling-up Poland: Co-housing of seniors Estonia: People with disabilities in remote areas Spain: Entrepreneurial skills for people long-term unemployed Hungary: Household economy in rural areas The Netherlands: No time to waste The Netherlands: Redesigning social services Italy: Reducing childhood obesity UK: Services for people with convictions Sweden: Social services for people with disabilities Finland: Youth co-empowerment Greece: City allotments

Conceptualising co-creation

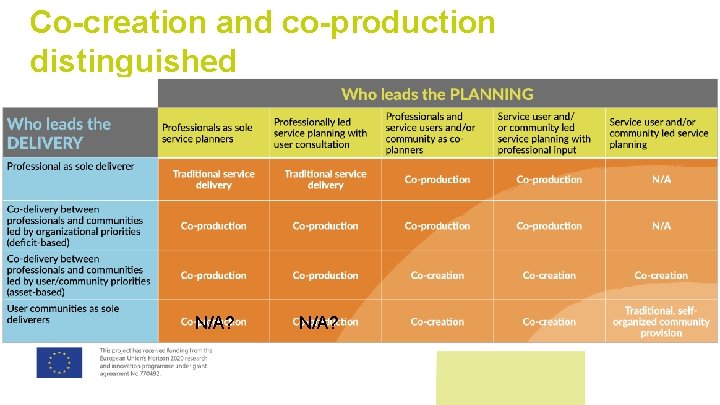

What is co-creation? • • • To tackle the major challenges of our time such as healthy ageing, climate change, youth unemployment and new forms of crime we need social innovation: using social means to achieve social ends. Studies of social innovation highlight importance of co-creation Together, co-creation and social innovation have become widely recognised as a reform strategy for public services What do we mean by cocreation? • Where people with lived experience work with professionals to design and deliver services. • Involvement in planning services distinguishes cocreation from co-production • Co-creation: “an interactive and dynamic relationship where value is created at the nexus of interaction” (Osborne 2018)

Co-creation and co-production distinguished N/A?

Assets and capabilities • Private sector generally assumes that service users have agency and capabilities sufficient to engage in cocreation. • Starting point in the public sector is often to try to fix things for people in the shortterm or encourage them to take action that fits the service’s priorities, not their own (Wilson et al. 2018). • This is deficit-based thinking – ‘bad help’ Bad help “[L]eaves people without clarity about the changes they want to make or the knowledge, confidence or support to get there. It often only addresses a single (and often most visible) aspect of people’s lives, without taking account of what else is going on. ” (Wilson et al. 2018: 5)

Strengths-based approaches • Strengths-based approaches start from the position that people have assets or ‘strengths’. • These include both their current intangible resources (perhaps skills, experience or networks) and their potential to develop new community and personal assets. • Draws together concepts of participation and citizenship with social capital. • Good help The current welfare state has become an elaborate attempt to manage our needs. In contrast, twentyfirst-century forms of help will support us to grow our capabilities. (Cottam 2018)

• Lessons from Co. SIE Strengths-based working is usually possible in the delivery of public services, even when participation in the service is mandated or there is little prior history of co-creation. Stengths-based working is time and resource intensive. Engaging people unused to having their voices heard demanded hard work, sensitivity to their needs, and sometimes extra resources. Sustaining co-creation is harder than animating it. Real, visible results are essential because without them there is a danger of disillusionment, cynicism and disengagement.

Implementing co -creation

Co-creation means new roles for staff • • New relational skills Understanding and working with resistance to change • • • From inward look to outward look Valuing experiential expertise and professional expertise Recognising the complex motivations of front-line staff Space for reflective practice New roles that incorporate lived experience The complex motivations of front -line staff or ‘street level bureaucrats’ Teachers, social workers, police officers, nurses, etc. Their work is often “highly scripted to achieve policy objectives” (Lipsky. xii) but also requires them to use discretion to meet the particular needs of individual clients. “the decisions of street-level bureaucrats, the routines they establish, and the devices they invent to cope with uncertainties and work pressures, effectively become the public policies they carry out” (Lipskey 2010: xiii)

Co-creation means rethinking risk • Public services often struggle to develop meaningful relationships with people because they are constrained by rigid thinking about ‘risk’, ‘safeguarding’ and ‘resource allocation’. • Strengths-based, co-created services re -think risk: – – – More positive, strengths-based language Think about risk holistically Draw on people’s wider assets (positive relationships, communities, etc. )

Implementing co-creation means rethinking organisations and systems • Different forms of organisation: – Getting people back into work, solving crimes, fixing broken bones; these all benefitted from hierarchy and stability, not only to solve the problem but to do so effectively and efficiently. Yet the social challenges these bureaucracies are now required to address are increasingly complex; this complexity highlights the ineffectiveness of traditional, hierarchical approaches. (Hannan 2019) • • ’Flatter’ organisations with more porous boundaries Interventions situated within ‘systems’ not organisations Continuous learning Boundary spanners: energetic and committed facilitators to navigate between organisations and different interests.

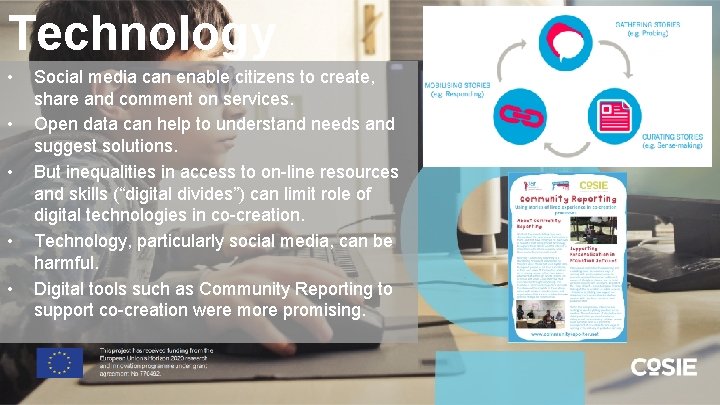

Technology • • • Social media can enable citizens to create, share and comment on services. Open data can help to understand needs and suggest solutions. But inequalities in access to on-line resources and skills (“digital divides”) can limit role of digital technologies in co-creation. Technology, particularly social media, can be harmful. Digital tools such as Community Reporting to support co-creation were more promising.

Beyond piloting co-creation

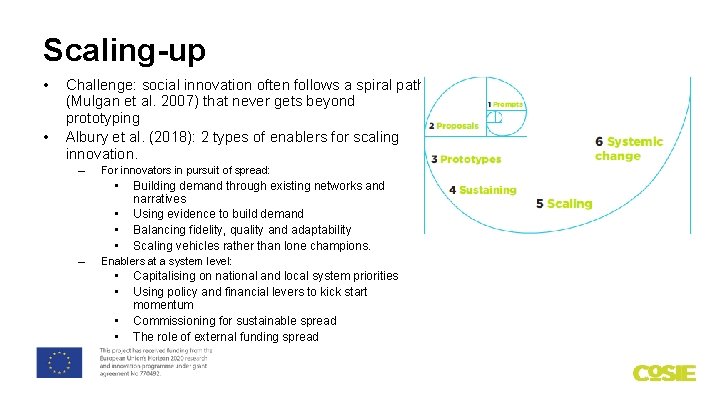

Scaling-up • • Challenge: social innovation often follows a spiral path (Mulgan et al. 2007) that never gets beyond prototyping Albury et al. (2018): 2 types of enablers for scaling innovation. – For innovators in pursuit of spread: • • – Building demand through existing networks and narratives Using evidence to build demand Balancing fidelity, quality and adaptability Scaling vehicles rather than lone champions. Enablers at a system level: • • Capitalising on national and local system priorities Using policy and financial levers to kick start momentum Commissioning for sustainable spread The role of external funding spread

![Evaluation • A big review of evidence on co-creation concluded: – • [G]iven the Evaluation • A big review of evidence on co-creation concluded: – • [G]iven the](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7f1263a03f3a93c840db525c82856a0e/image-16.jpg)

Evaluation • A big review of evidence on co-creation concluded: – • [G]iven the limited number records that reported on the outcomes of cocreation/co-production, we cannot definitely conclude whether cocreation/co-production can be considered as beneficial. (Voorberg et al. 2014) Evaluation should be: – Theory-led – Include methods and approaches the capture experience and allow people to co-produce research – Iterative with smaller pilots leading to larger evaluations that prioritise causal inference (eg counter-factual evaluations) Human Learning Systems • An iterative, experimental approach to working with people. • Funding and commissioning for learning, not Services • Funding organizations’ capacity to learn. • Using data to learn monitoring data for reflection, rather than monitoring targets • Creating a learning culture - a ‘positive error culture’ that encourages discussion about mistakes and uncertainties in practice. (Lowe et al. 2020)

Finding out more https: //cosie. turkuamk. fi/publications/

- Slides: 17