A Gendered Landscape Exploring the experiences of female

- Slides: 27

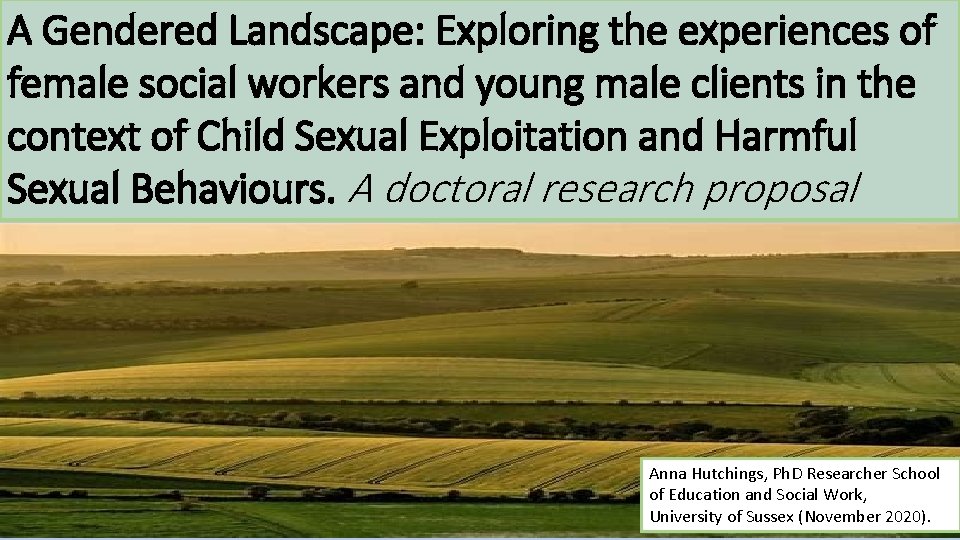

A Gendered Landscape: Exploring the experiences of female social workers and young male clients in the context of Child Sexual Exploitation and Harmful Sexual Behaviours. A doctoral research proposal Anna Hutchings, Ph. D Researcher School of Education and Social Work, University of Sussex (November 2020).

Definitions: Child Sexual Abuse CHILD SEXUAL EXPLOITATION (CSE): HARMFUL SEXUAL BEHAVIOURS (HSB): “sexual behaviours expressed by children and young people under the age of 18 years old that are developmentally inappropriate, may be harmful towards self or others, or be abusive towards another child, young person or adult. ” (Hacket et al 2019, p. 13). “Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology. ” (HM Government 2018, p. 103).

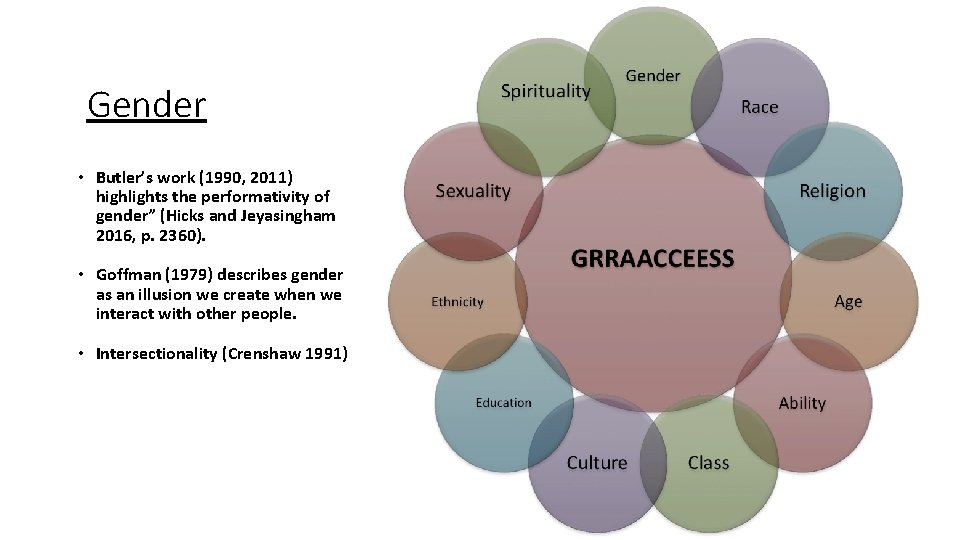

Gender • Butler’s work (1990, 2011) highlights the performativity of gender” (Hicks and Jeyasingham 2016, p. 2360). • Goffman (1979) describes gender as an illusion we create when we interact with other people. • Intersectionality (Crenshaw 1991)

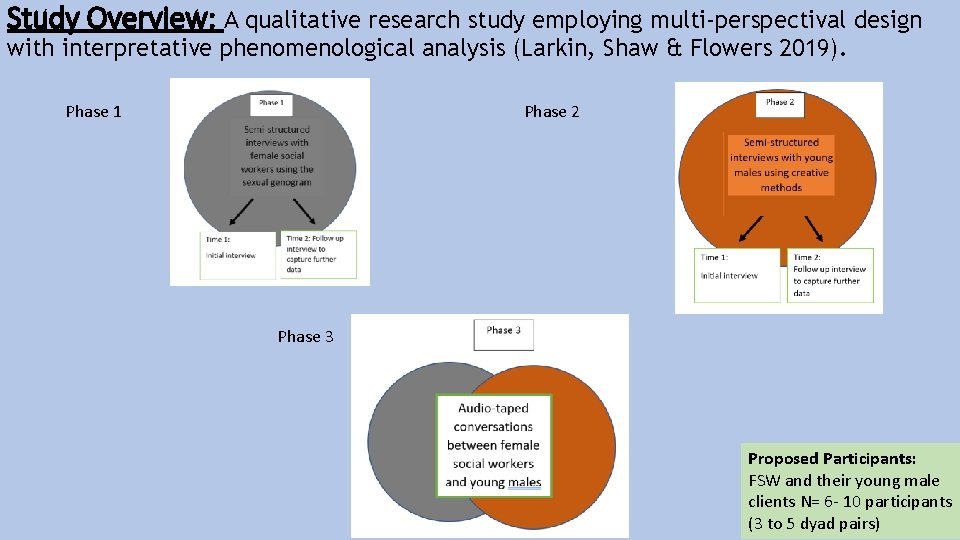

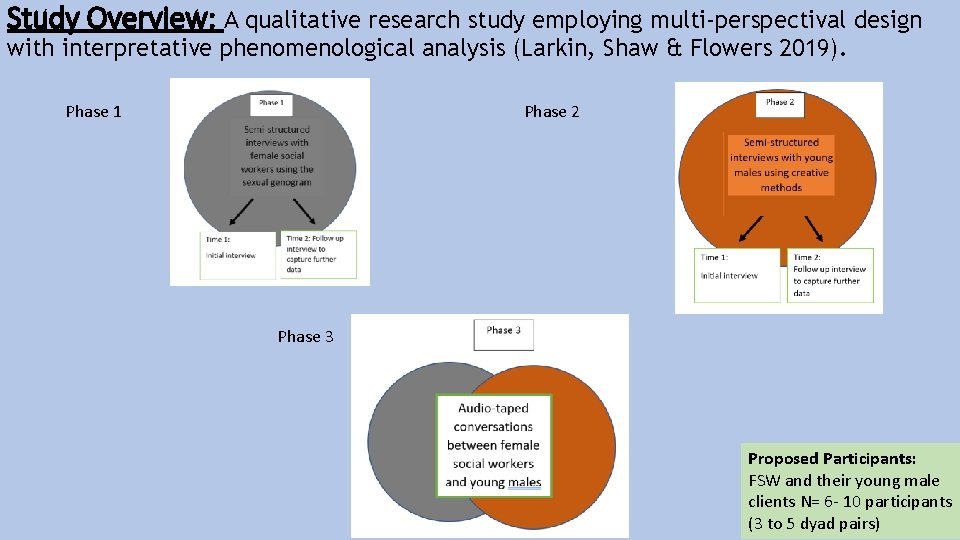

Study Overview: A qualitative research study employing multi-perspectival design with interpretative phenomenological analysis (Larkin, Shaw & Flowers 2019). Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Proposed Participants: FSW and their young male clients N= 6 - 10 participants (3 to 5 dyad pairs)

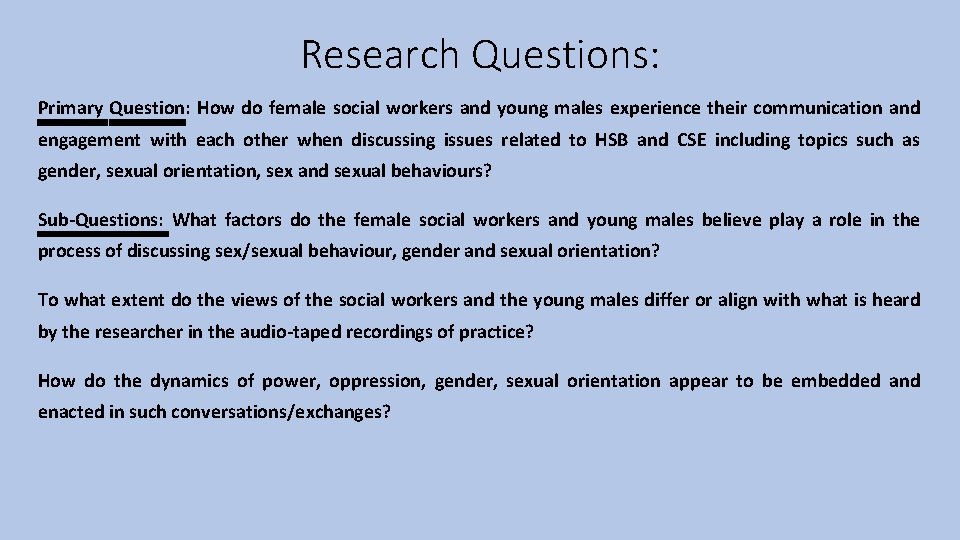

Research Questions: Primary Question: How do female social workers and young males experience their communication and engagement with each other when discussing issues related to HSB and CSE including topics such as gender, sexual orientation, sex and sexual behaviours? Sub-Questions: What factors do the female social workers and young males believe play a role in the process of discussing sex/sexual behaviour, gender and sexual orientation? To what extent do the views of the social workers and the young males differ or align with what is heard by the researcher in the audio-taped recordings of practice? How do the dynamics of power, oppression, gender, sexual orientation appear to be embedded and enacted in such conversations/exchanges?

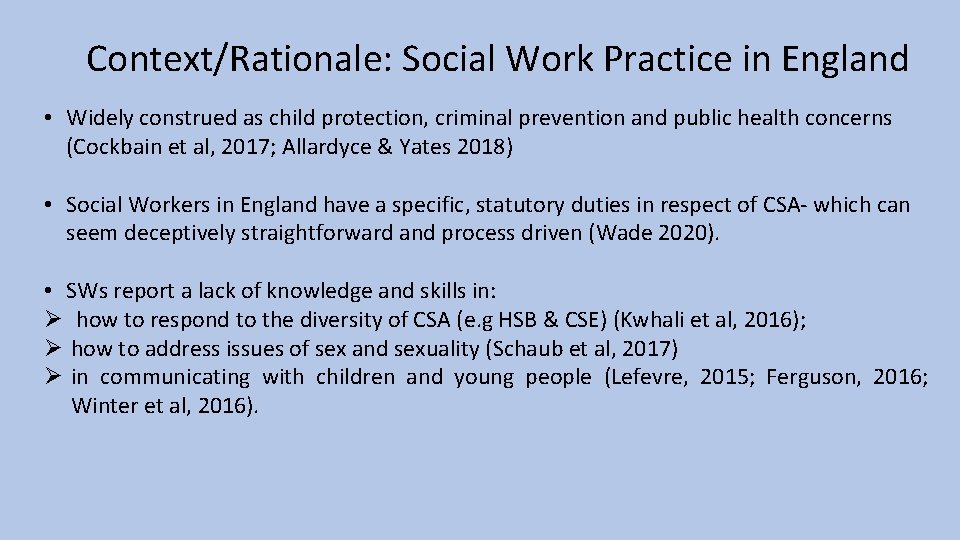

Context/Rationale: Social Work Practice in England • Widely construed as child protection, criminal prevention and public health concerns (Cockbain et al, 2017; Allardyce & Yates 2018) • Social Workers in England have a specific, statutory duties in respect of CSA- which can seem deceptively straightforward and process driven (Wade 2020). • SWs report a lack of knowledge and skills in: Ø how to respond to the diversity of CSA (e. g HSB & CSE) (Kwhali et al, 2016); Ø how to address issues of sex and sexuality (Schaub et al, 2017) Ø in communicating with children and young people (Lefevre, 2015; Ferguson, 2016; Winter et al, 2016).

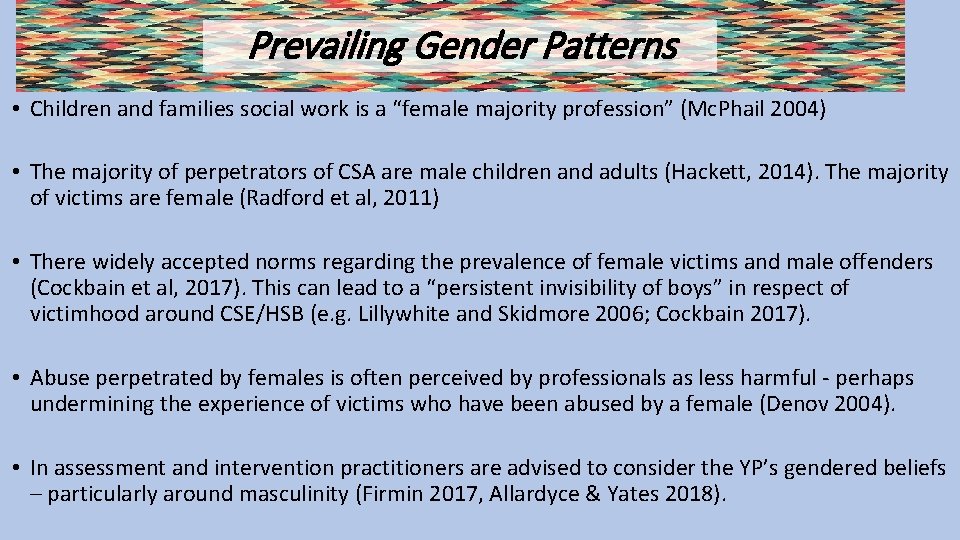

Prevailing Gender Patterns • Children and families social work is a “female majority profession” (Mc. Phail 2004) • The majority of perpetrators of CSA are male children and adults (Hackett, 2014). The majority of victims are female (Radford et al, 2011) • There widely accepted norms regarding the prevalence of female victims and male offenders (Cockbain et al, 2017). This can lead to a “persistent invisibility of boys” in respect of victimhood around CSE/HSB (e. g. Lillywhite and Skidmore 2006; Cockbain 2017). • Abuse perpetrated by females is often perceived by professionals as less harmful - perhaps undermining the experience of victims who have been abused by a female (Denov 2004). • In assessment and intervention practitioners are advised to consider the YP’s gendered beliefs – particularly around masculinity (Firmin 2017, Allardyce & Yates 2018).

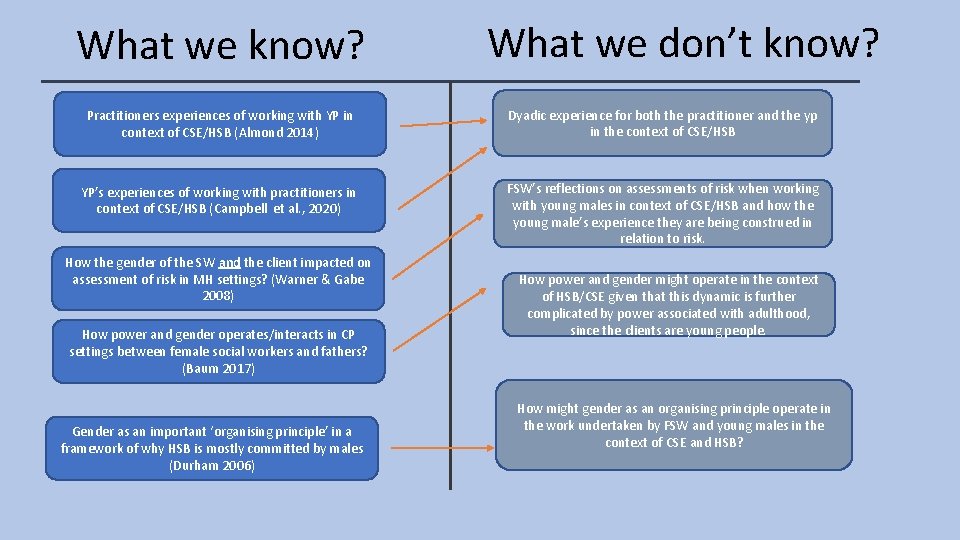

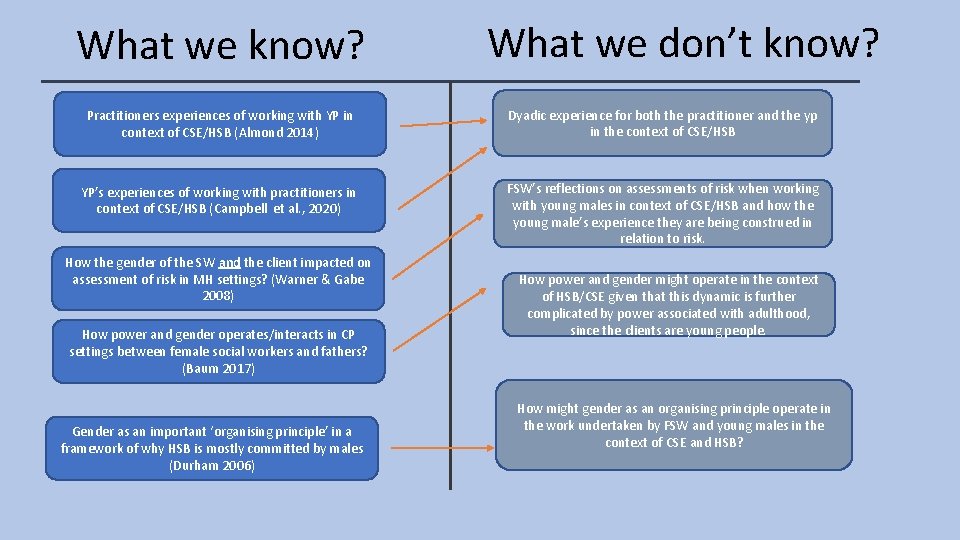

What we know? What we don’t know? Practitioners experiences of working with YP in context of CSE/HSB (Almond 2014) Dyadic experience for both the practitioner and the yp in the context of CSE/HSB YP’s experiences of working with practitioners in context of CSE/HSB (Campbell et al. , 2020) FSW’s reflections on assessments of risk when working with young males in context of CSE/HSB and how the young male’s experience they are being construed in relation to risk. How the gender of the SW and the client impacted on assessment of risk in MH settings? (Warner & Gabe 2008) How power and gender operates/interacts in CP settings between female social workers and fathers? (Baum 2017) Gender as an important ‘organising principle’ in a framework of why HSB is mostly committed by males (Durham 2006) How power and gender might operate in the context of HSB/CSE given that this dynamic is further complicated by power associated with adulthood, since the clients are young people. How might gender as an organising principle operate in the work undertaken by FSW and young males in the context of CSE and HSB?

Reflecting on ontology and epistemology Social Constructionist framework Critical Realism framework

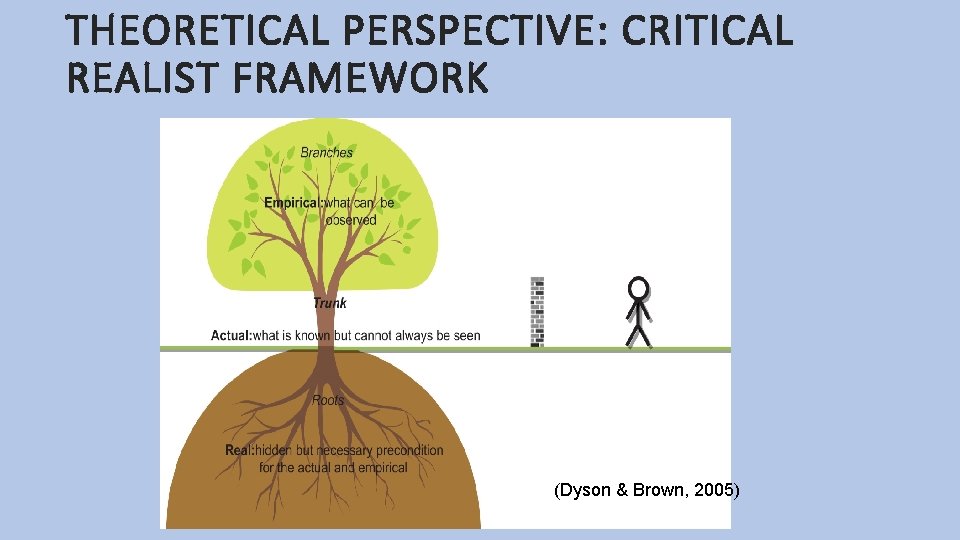

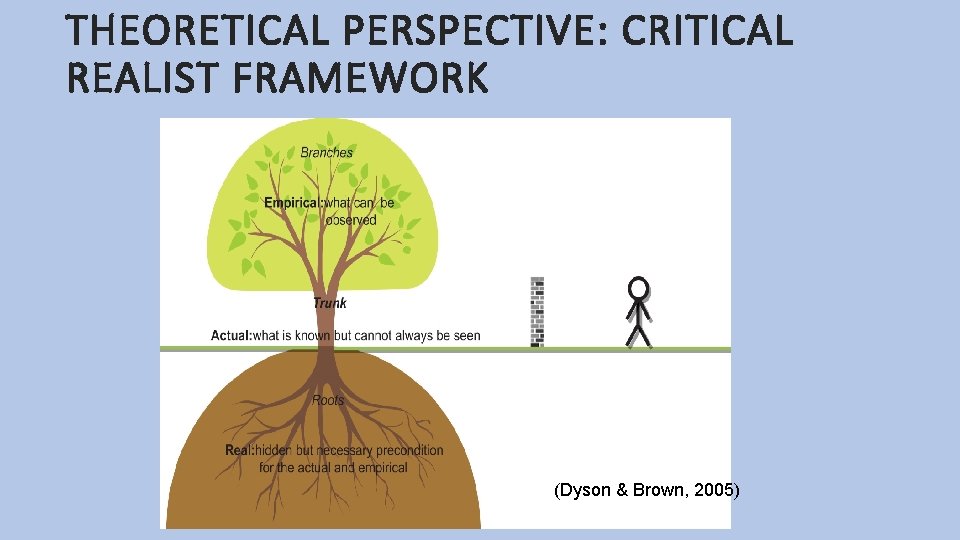

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE: CRITICAL REALIST FRAMEWORK (Dyson & Brown, 2005)

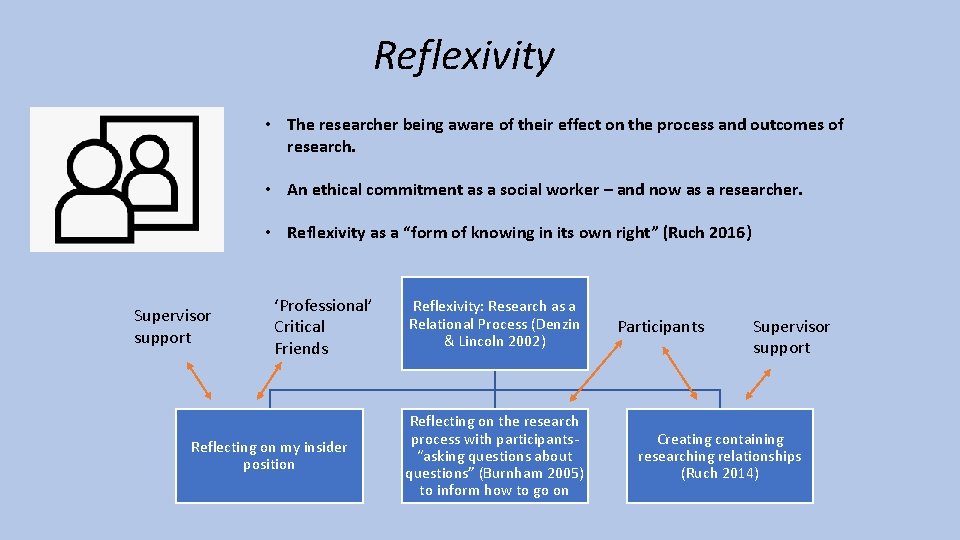

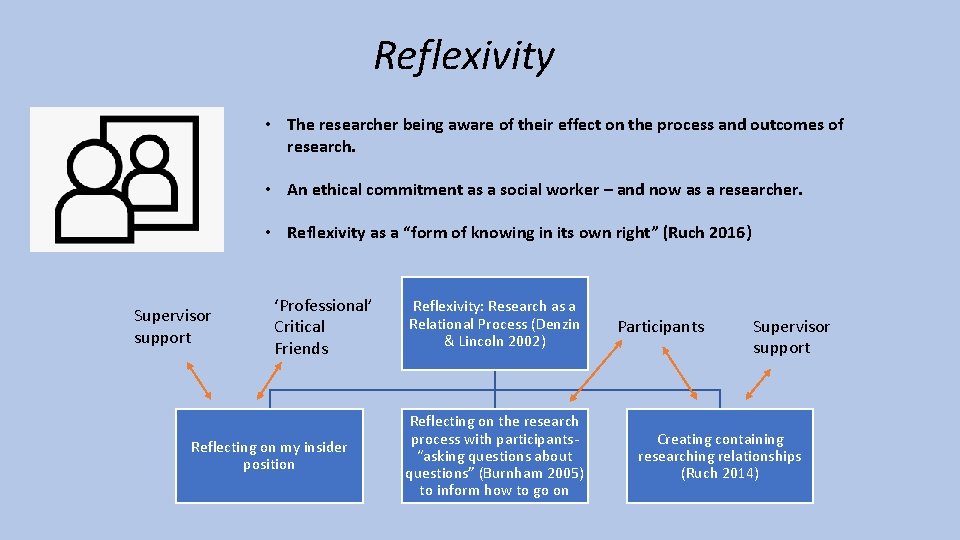

Reflexivity • The researcher being aware of their effect on the process and outcomes of research. • An ethical commitment as a social worker – and now as a researcher. • Reflexivity as a “form of knowing in its own right” (Ruch 2016) Supervisor support ‘Professional’ Critical Friends Reflecting on my insider position Reflexivity: Research as a Relational Process (Denzin & Lincoln 2002) Reflecting on the research process with participants“asking questions about questions” (Burnham 2005) to inform how to go on Participants Supervisor support Creating containing researching relationships (Ruch 2014)

Methodology: IPA assumptions • People are “intrinsically…self reflexive, sense making agent(s) who are interpreting their engagement with the world” (Smith 2019, p. 167). • Entails a double act of interpretation – ‘double hermeneutic’ whereby “researchers are people trying to make sense of their own experiences” (Hood 2016, p. 165). • It emphasizes the researcher’s preconceptions and the impossibility of ‘bracketing’ these away completely • It is partial and tentative in its understanding of participant’s experiences. • IPA resonates with a critical realist framework as “what is real is not dependent on us, but the exact meaning and nature of reality is. ” (Larkin et al. , 2006, p. 107).

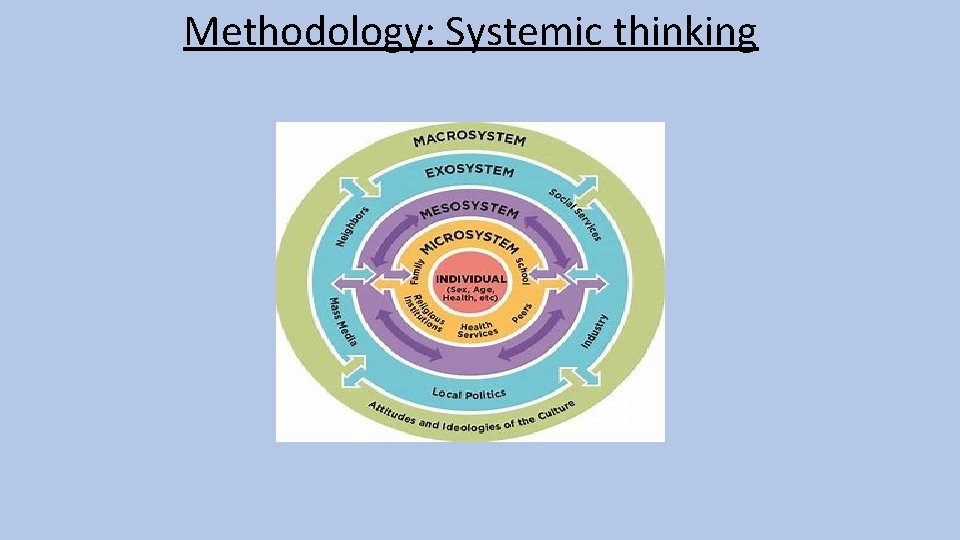

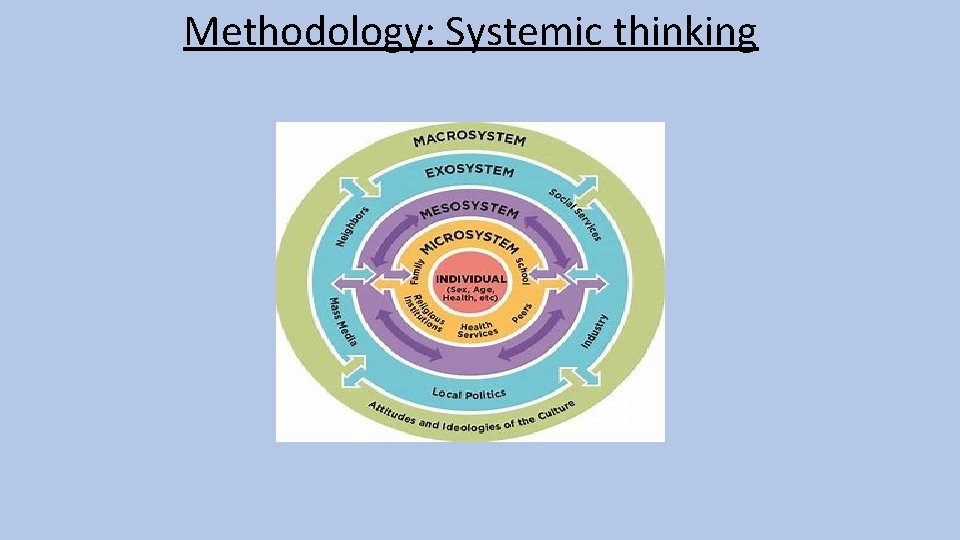

Methodology: Systemic thinking

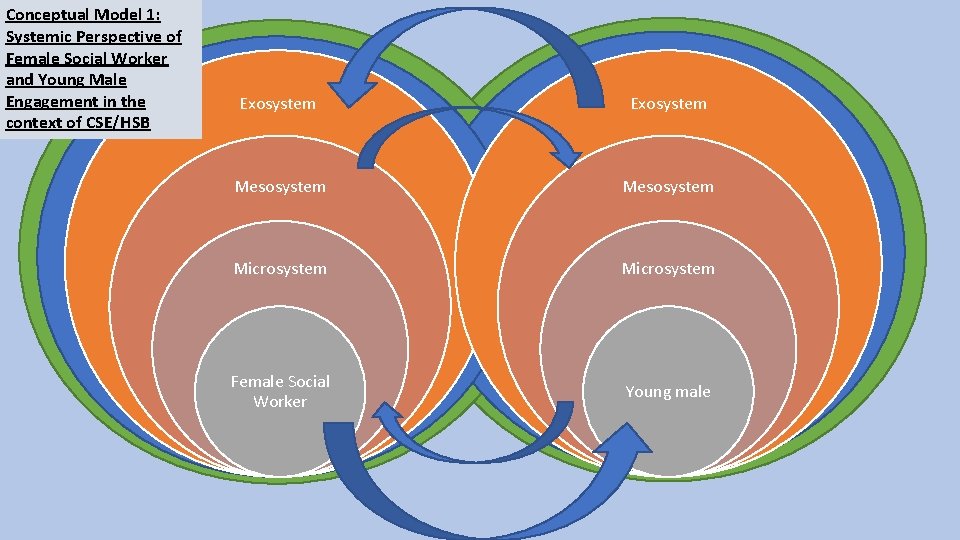

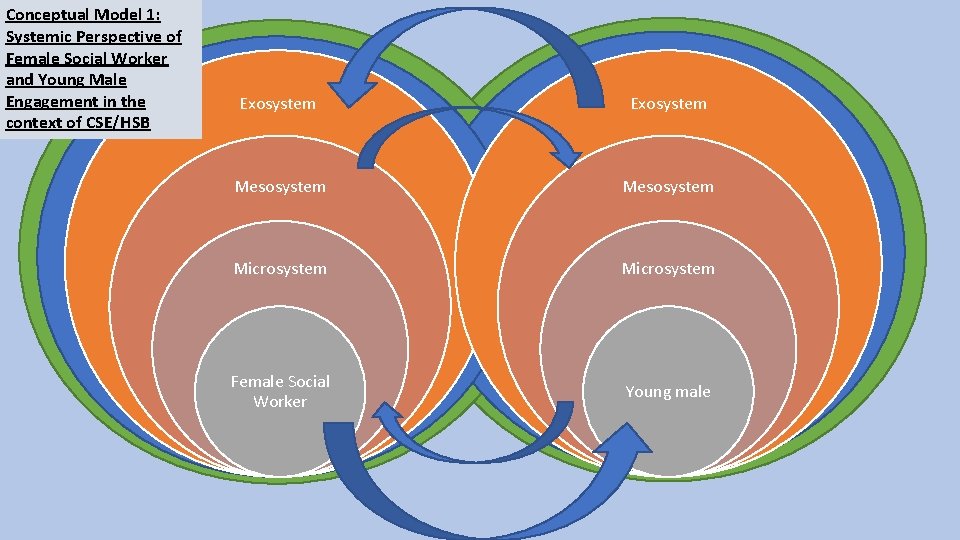

Conceptual Model 1: Systemic Perspective of Female Social Worker and Young Male Engagement in the context of CSE/HSB Exosystem Mesosystem Microsystem Female Social Worker Young male

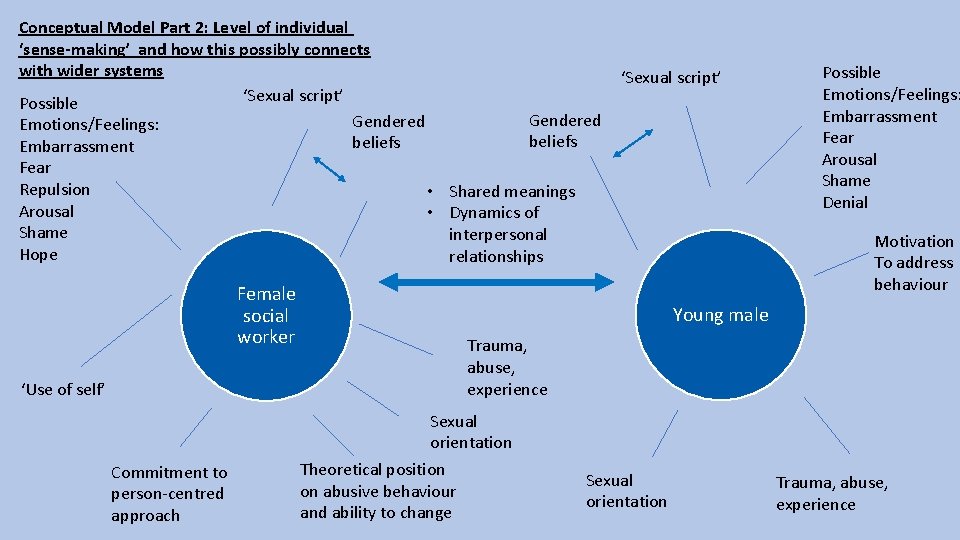

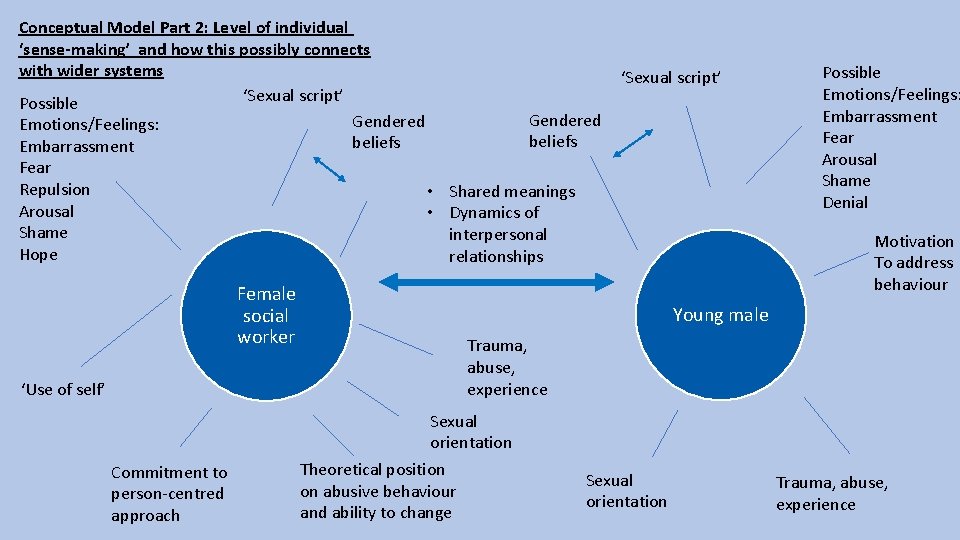

Conceptual Model Part 2: Level of individual ‘sense-making’ and how this possibly connects with wider systems ‘Sexual script’ Possible Gendered Emotions/Feelings: beliefs Embarrassment Fear Repulsion • Arousal • Shame Hope Female social worker ‘Use of self’ Commitment to person-centred approach ‘Sexual script’ Gendered beliefs Shared meanings Dynamics of interpersonal relationships Possible Emotions/Feelings: Embarrassment Fear Arousal Shame Denial Motivation To address behaviour Young male Trauma, abuse, experience Sexual orientation Theoretical position on abusive behaviour and ability to change Sexual orientation Trauma, abuse, experience

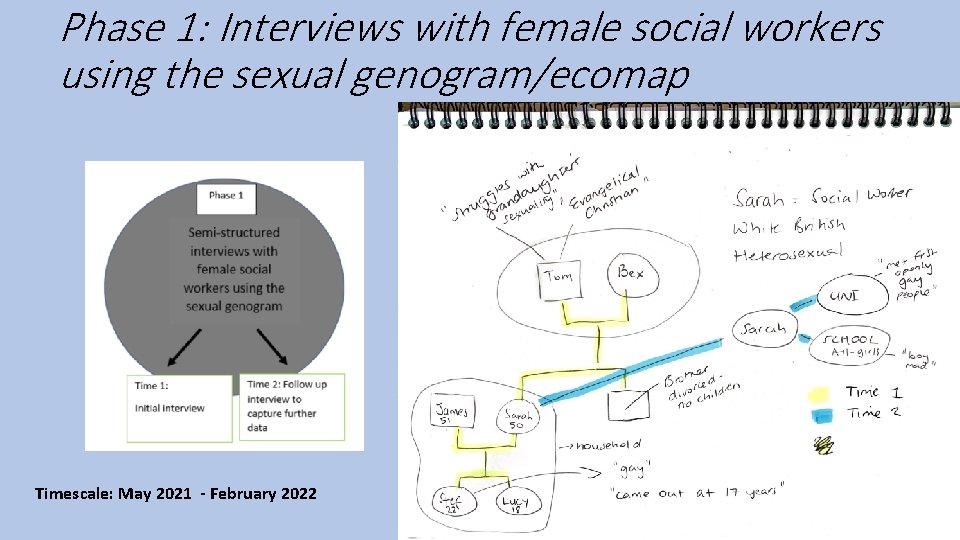

Phase 1: Interviews with female social workers using the sexual genogram/ecomap Timescale: May 2021 - February 2022

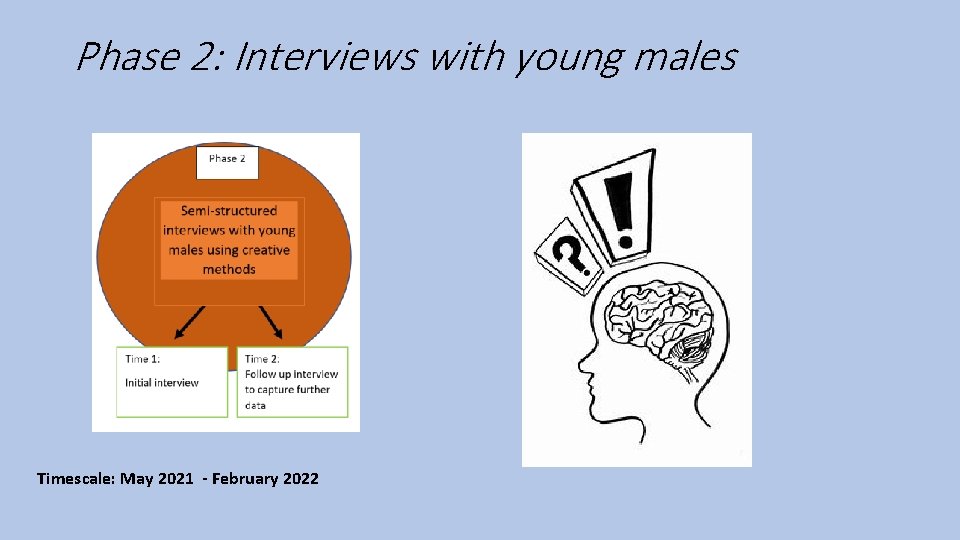

Phase 2: Interviews with young males Timescale: May 2021 - February 2022

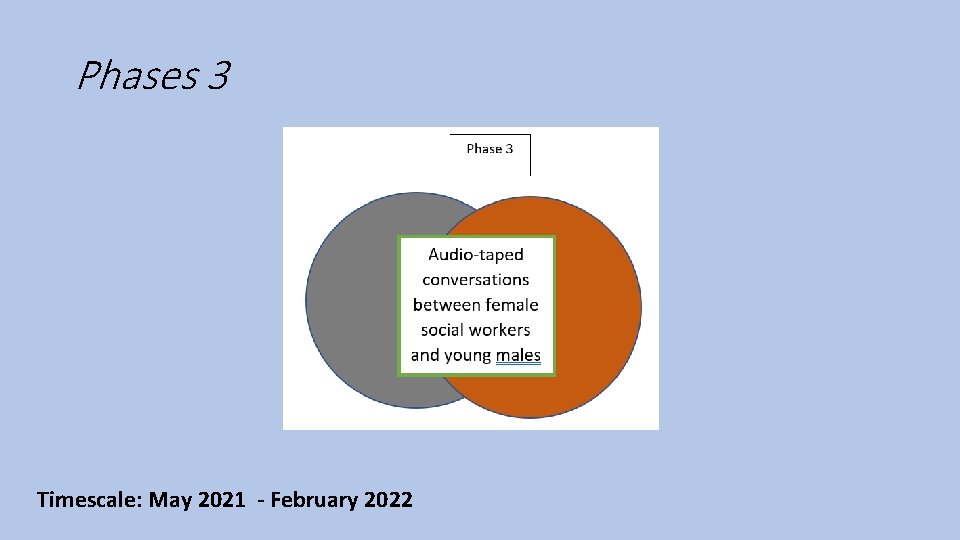

Phases 3 Timescale: May 2021 - February 2022

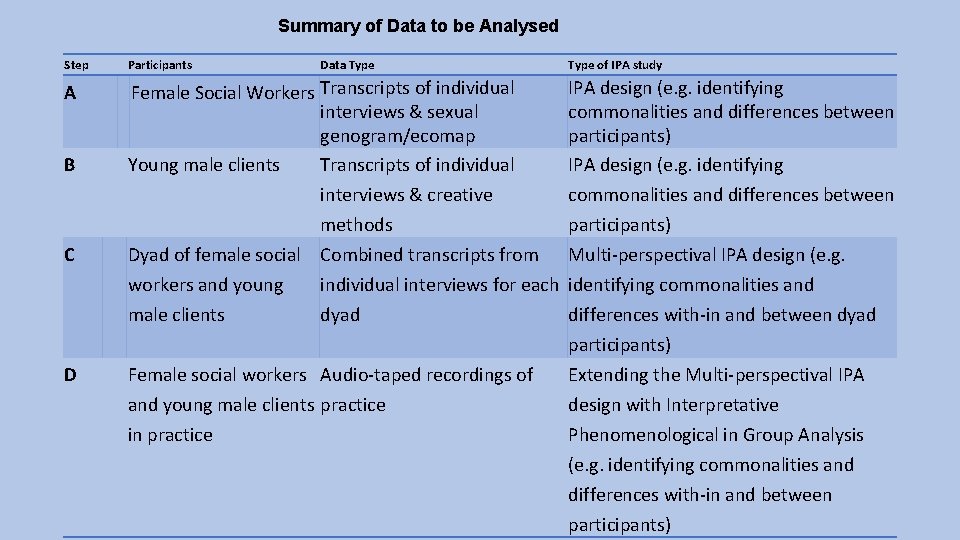

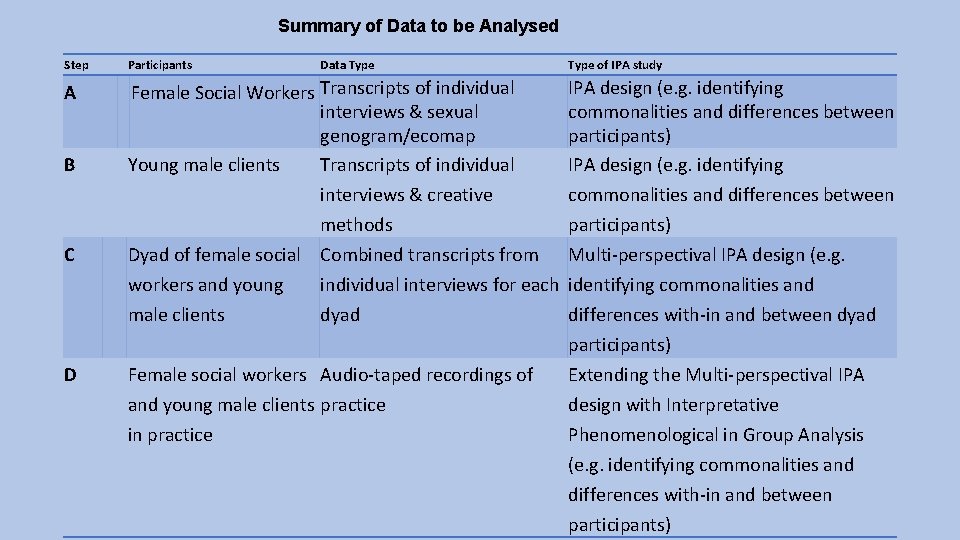

Summary of Data to be Analysed Step Participants Data Type of IPA study A B Female Social Workers Transcripts of individual interviews & sexual genogram/ecomap Young male clients Transcripts of individual IPA design (e. g. identifying commonalities and differences between participants) IPA design (e. g. identifying C interviews & creative methods Dyad of female social Combined transcripts from commonalities and differences between participants) Multi-perspectival IPA design (e. g. workers and young male clients D individual interviews for each identifying commonalities and dyad differences with-in and between dyad participants) Female social workers Audio-taped recordings of Extending the Multi-perspectival IPA and young male clients practice in practice design with Interpretative Phenomenological in Group Analysis (e. g. identifying commonalities and differences with-in and between participants)

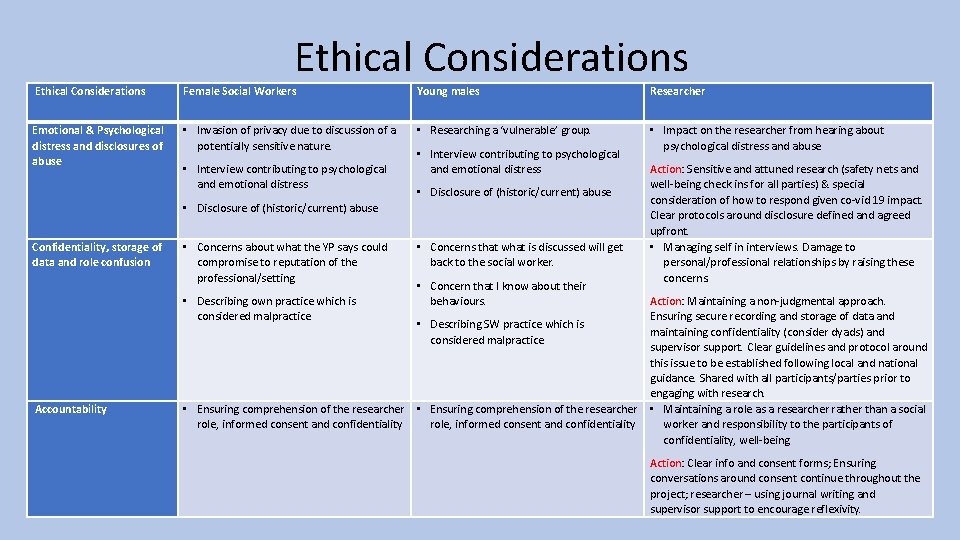

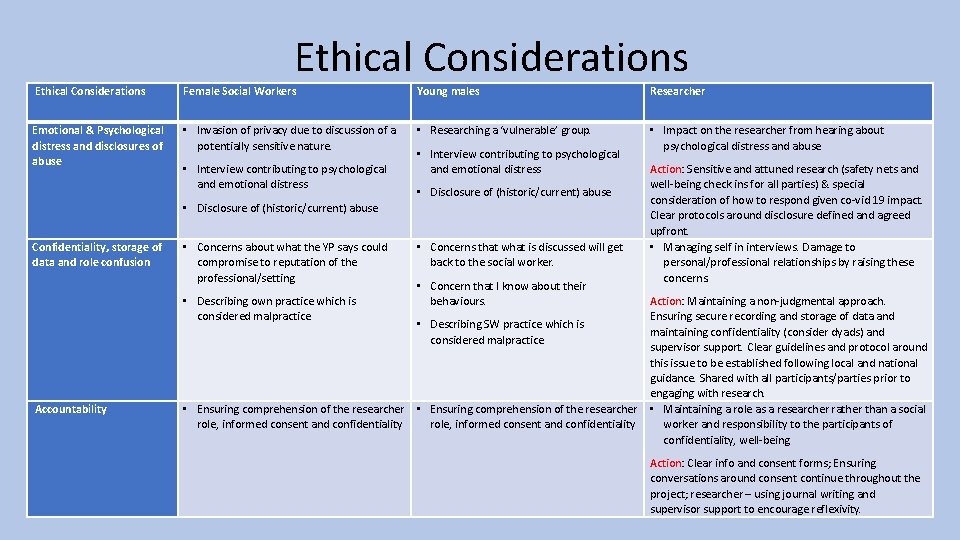

Ethical Considerations Female Social Workers Young males Researcher Emotional & Psychological distress and disclosures of abuse • Invasion of privacy due to discussion of a potentially sensitive nature. • Researching a ‘vulnerable’ group. • Impact on the researcher from hearing about psychological distress and abuse • Interview contributing to psychological and emotional distress • Disclosure of (historic/current) abuse Confidentiality, storage of data and role confusion • Concerns about what the YP says could compromise to reputation of the professional/setting • Describing own practice which is considered malpractice Accountability • Concerns that what is discussed will get back to the social worker. • Concern that I know about their behaviours. • Describing SW practice which is considered malpractice • Ensuring comprehension of the researcher role, informed consent and confidentiality Action: Sensitive and attuned research (safety nets and well-being check ins for all parties) & special consideration of how to respond given co-vid 19 impact. Clear protocols around disclosure defined and agreed upfront. • Managing self in interviews. Damage to personal/professional relationships by raising these concerns. Action: Maintaining a non-judgmental approach. Ensuring secure recording and storage of data and maintaining confidentiality (consider dyads) and supervisor support. Clear guidelines and protocol around this issue to be established following local and national guidance. Shared with all participants/parties prior to engaging with research. • Maintaining a role as a researcher rather than a social worker and responsibility to the participants of confidentiality, well-being Action: Clear info and consent forms; Ensuring conversations around consent continue throughout the project; researcher – using journal writing and supervisor support to encourage reflexivity.

Limitations/Risks • Covid-19 • Attrition –in relation to young male participants and ‘dyads’ • Access sources of data on practice experience, e. g. audio tapes of practice. • The sensitivity of the topic and selection mechanisms skewing who is likely to become a possible participant.

References: • Allardyce, S. and Yates, P. (2018) Working with children and young people who have displayed harmful sexual behaviour, Edinburgh, Dunedin • Almond, T. J. (2014) Working with children and young people with harmful sexual behaviours: exploring impact on practitioners and sources of support, Journal of Sexual Aggression, 20: 3, pp. 333 353 • Baum, N. (2017) Gender sensitive intervention to improve work with fathers in child welfare services. Child and Family Social Work. 22. pp. 419 427 • Burnham, J. (2005). Relational Reflexivity: A tool for socially constructing therapeutic relationships in “The Space Between” Flaskas, C. , Mason, B. , Perlerz, A. Karnac Pubs: UK • Butler, J. (1990) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, New York, Routledge. • Campbell, F. , Booth, A. , Hackett, S. & Sutton, A (2020) Young people who display harmful sexual behaviours and their families: A qualitative systematic review of their experiences of professional interventions. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 21: 3. pp. 456 469. • Cockbain, E. , Ashby, M. , & Brayley, H. (2017). Immaterial Boys? A Large Scale Exploration of Gender Based Differences in Child Sexual Exploitation Service Users. Sexual Abuse, 29(7), pp. 658– 684.

References: • Denov, M. (2003) To a safer place? Victims of sexual abuse by females and their disclosures to professionals. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(1): pp. 47– 61 • Denzin, N. K. , & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds. ). (2002). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3 rd ed. ). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. • Durham, A. (2006) Young men who have sexually abused: A case study. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. • Dyson, S. , Brown, B. , 2005. Social Theory and Applied Health Research. Open University Press, Buckingham. • Ferguson, H. (2016) ‘Researching social work practice close up: Using ethnographic and mobile methods to understand encounters between social workers, children and families’, British Journal of Social Work, 46(1), pp. 153– 68. • Firmin, C (2017) ‘Contextual risk, individualised responses: An assessment of safeguarding responses to nine cases of peer on peer abuse’. Child Abuse Review • Goffman, E. (1979) ‘Gender display’, in Gender Advertisements. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

References: • Hackett, S, Branigan, P and Holmes, D (2019). Harmful sexual behaviour framework: an evidence-informed operational framework for children and young people displaying harmful sexual behaviours, second edition, London, NSPCC. • HM Government (2018) Working Together to Safeguard Children: A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. London: Department for Education. • Hood, R. (2016) Combining phenomenological and critical methodologies in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work. Vol. 15(2): pp. 160 174 • Kwhali, J. , Martin, L. , Brady, G. and Brown, S. J (2016) Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: Knowledge, Confidence and Training within a Contemporary UK Social Work Practice and Policy Context. British Journal of Social Work. 46, pp. 2208 2226 • Larkin, M. , Watts, S. , & Clifton, E. (2006). Giving voice and making sense in interpretative phenomenologi cal analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, pp. 102– 120. • Larkin, M. , Shaw, R. & Flowers, . P. (2019) Multi perspectival designs and processes in interpretative phenomenological analysis research, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16: 2, pp. 182 198,

References: • Lefevre, M. (2015) Becoming effective communicators with children: developing practitioner capability through social work education, British Journal of Social Work, 45 (1): pp. 204 224. • Lillywhite, R. , & Skidmore, P. (2006). Boys are not sexually exploited? A challenge to practitioners. Child Abuse Review. 15, pp. 351 361. • Mc. Phail, B. A. (2004) Setting the record straight: Social work is not a female dominated profession. Social Work 49(2): pp. 323– 326. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishes • Radford, L. , Corral, S. , Bradley, C. , Fisher, H. , Bassett, C. , Howat, N. and Collishaw, S. (2011) Child abuse and neglect in the UK today. London: NSPCC • Ruch, G. and Julkunen, I. , (2016) Relationship-Based Research In Social Work. • Schaub, J. , Willis, P. B. , & Dunk West, P. (2017). Accounting for Self, Sex and Sexuality in UK Social Workers’ Knowledge Base: Findings from an Exploratory Study. British Journal of Social Work, 47(2), pp. 427 446.

References: • Smith, J. A. (2019) Participants and researchers searching for meaning: Conceptual developments for interpretative phenomenological analysis, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16: 2, pp. 166 181 • Wade, G. , (2020) Child Sexual Abuse: A critical analysis of social workers’ role in recognising and responding to it. British Journal of Child Health. Vol. 1, No. 1. pp. 26 33 • Warner, J & Gabe, J. (2008) Risk, Mental Disorder and Social Work Practice: A Gendered Landscape, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 38, Issue 1, January 2008, pp. 117– 134 • Winter, K. , Cree, V. , Hallett, S. , Hadfield, M. , Ruch, G. , Morrison, F. and Holland, S. (2016). Exploring communication between social workers, children and young people. The British Journal of Social Work, 47 (5). pp. 1427 1444