A critical examination of classical niche partitioning foraging

- Slides: 34

A critical examination of classical niche partitioning: foraging behavior, available prey, and diet Cody M. Kent Tulane University

Fun fact

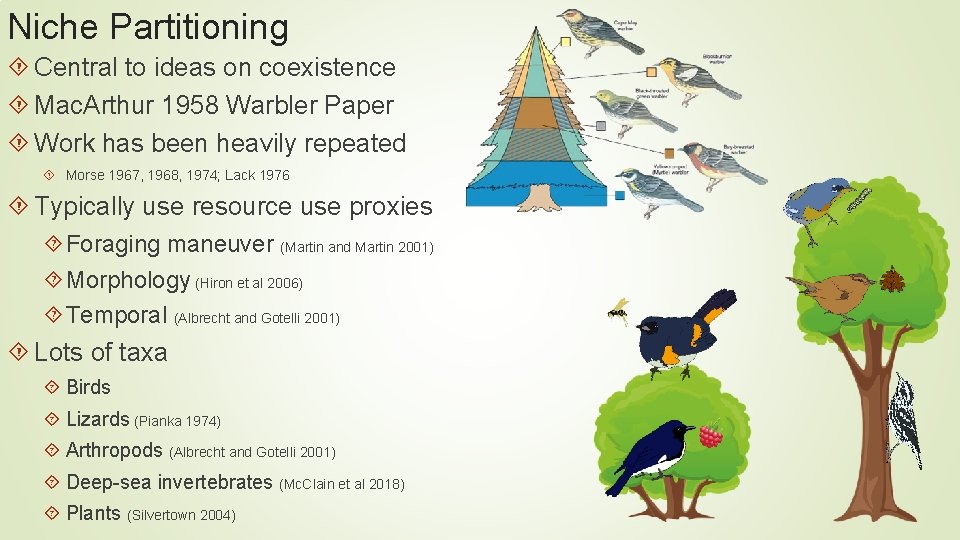

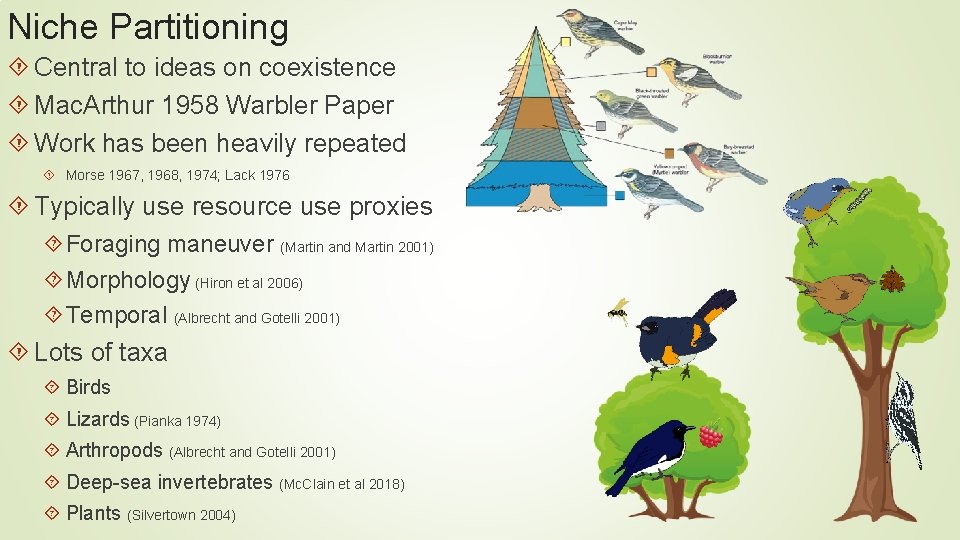

Niche Partitioning Central to ideas on coexistence Mac. Arthur 1958 Warbler Paper Work has been heavily repeated Morse 1967, 1968, 1974; Lack 1976 Typically use resource use proxies Foraging maneuver (Martin and Martin 2001) Morphology (Hiron et al 2006) Temporal (Albrecht and Gotelli 2001) Lots of taxa Birds Lizards (Pianka 1974) Arthropods (Albrecht and Gotelli 2001) Deep-sea invertebrates (Mc. Clain et al 2018) Plants (Silvertown 2004)

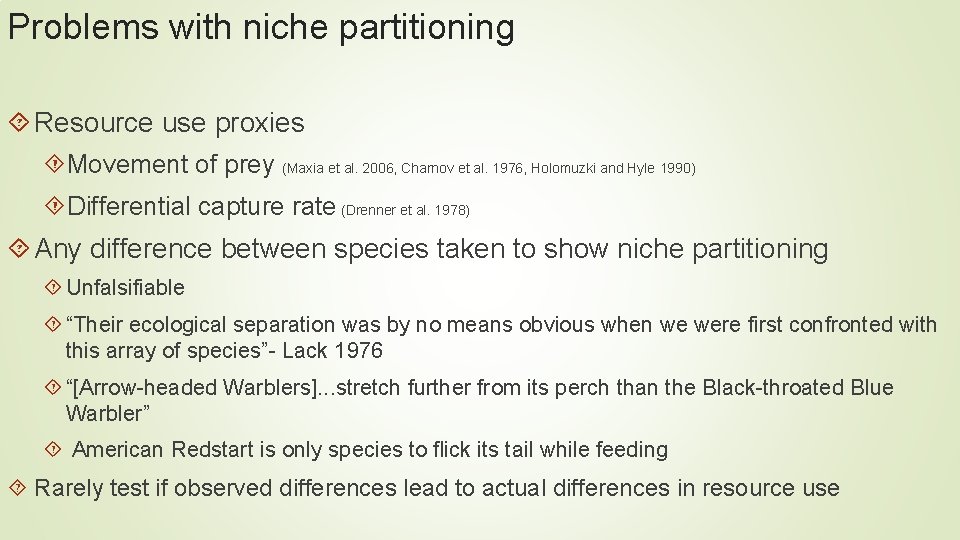

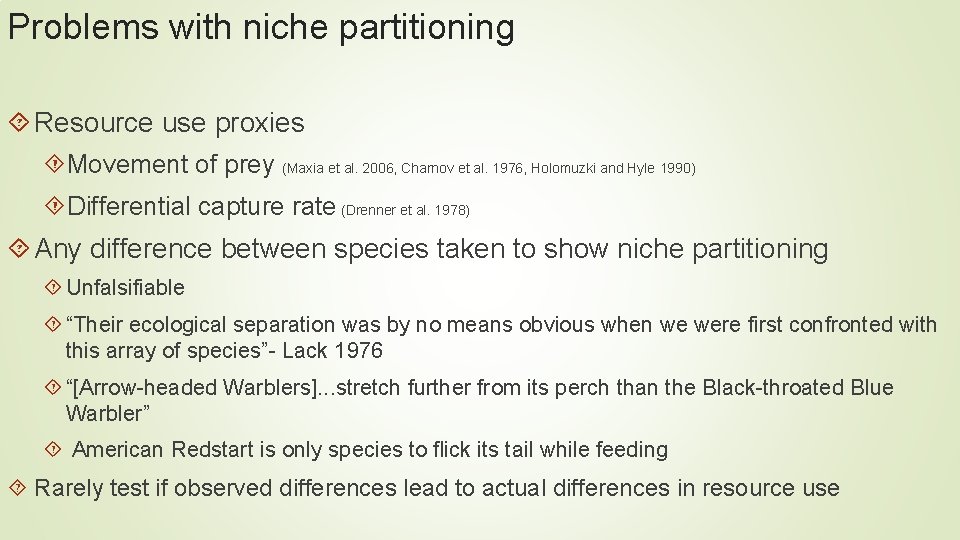

Problems with niche partitioning Resource use proxies Movement of prey (Maxia et al. 2006, Charnov et al. 1976, Holomuzki and Hyle 1990) Differential capture rate (Drenner et al. 1978) Any difference between species taken to show niche partitioning Unfalsifiable “Their ecological separation was by no means obvious when we were first confronted with this array of species”- Lack 1976 “[Arrow-headed Warblers]. . . stretch further from its perch than the Black-throated Blue Warbler” American Redstart is only species to flick its tail while feeding Rarely test if observed differences lead to actual differences in resource use

Research Questions Do differences in foraging behavior lead to differences in diet? How effective is behavior as a coexistence mechanism?

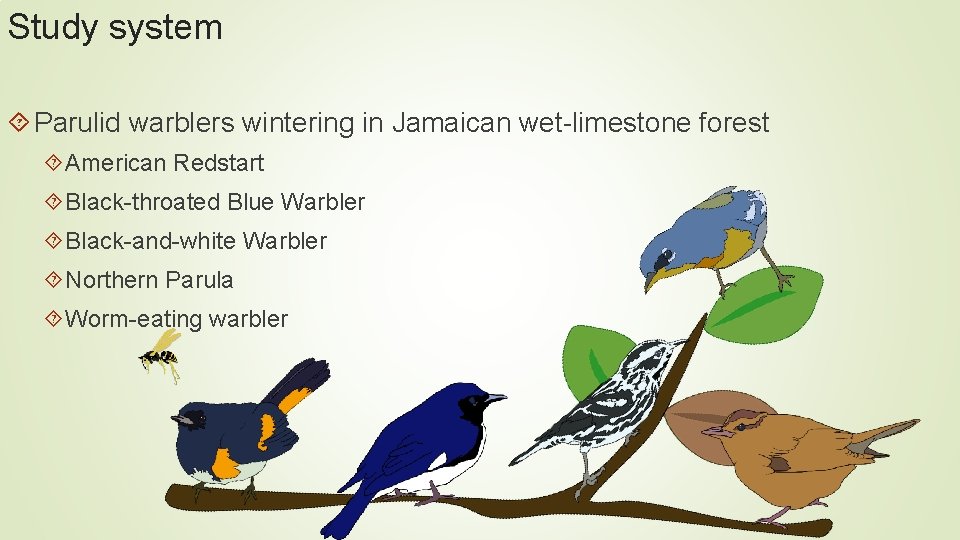

Study system Parulid warblers wintering in Jamaican wet-limestone forest American Redstart Black-throated Blue Warbler Black-and-white Warbler Northern Parula Worm-eating warbler

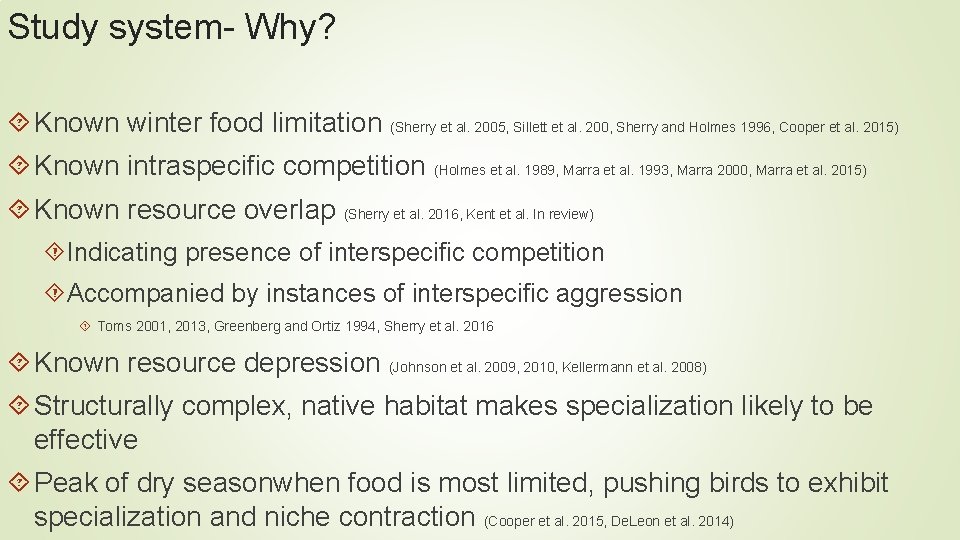

Study system- Why? Known winter food limitation (Sherry et al. 2005, Sillett et al. 200, Sherry and Holmes 1996, Cooper et al. 2015) Known intraspecific competition (Holmes et al. 1989, Marra et al. 1993, Marra 2000, Marra et al. 2015) Known resource overlap (Sherry et al. 2016, Kent et al. In review) Indicating presence of interspecific competition Accompanied by instances of interspecific aggression Toms 2001, 2013, Greenberg and Ortiz 1994, Sherry et al. 2016 Known resource depression (Johnson et al. 2009, 2010, Kellermann et al. 2008) Structurally complex, native habitat makes specialization likely to be effective Peak of dry seasonwhen food is most limited, pushing birds to exhibit specialization and niche contraction (Cooper et al. 2015, De. Leon et al. 2014)

Predictions Coexisting warbler species will differ in foraging behavior These warblers will also differ diet Observed differences in foraging behavior between species will explain differences in diet (Part 2)

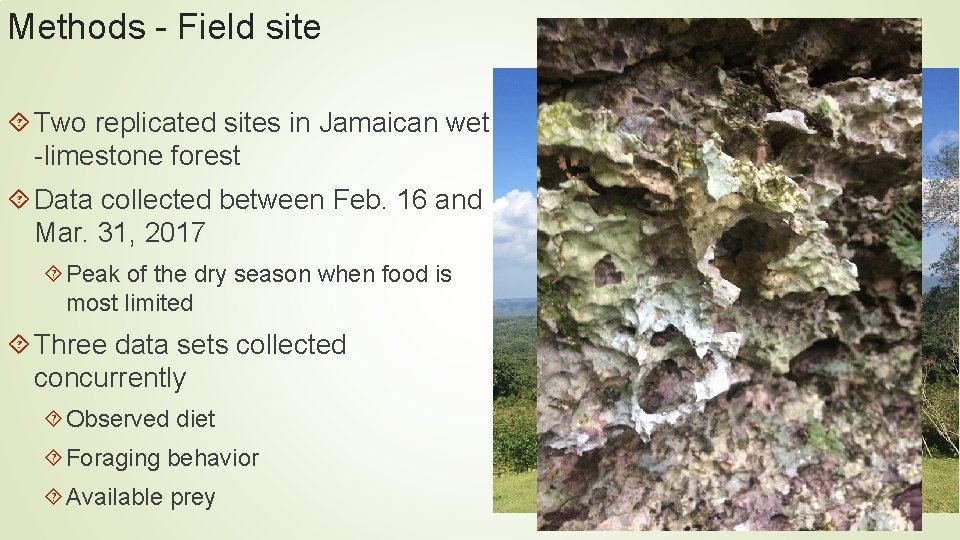

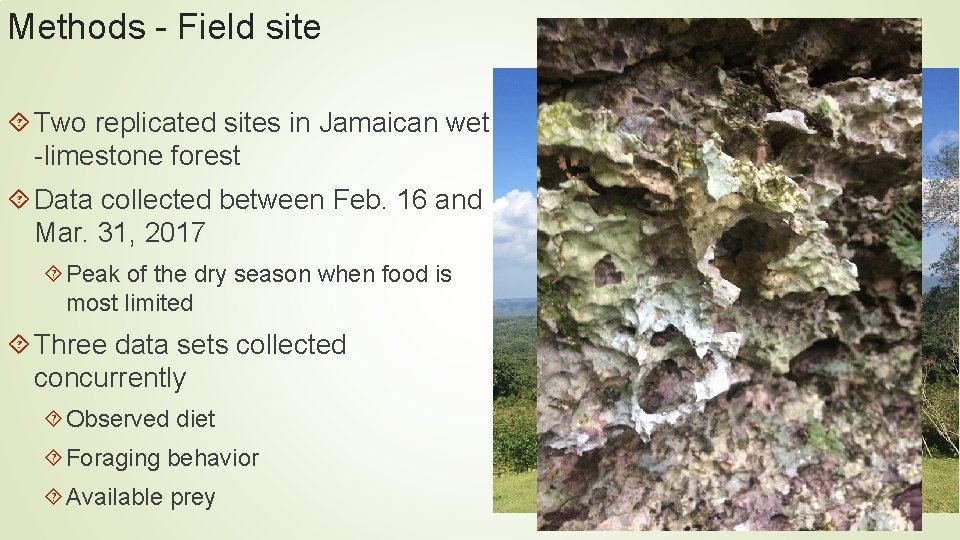

Methods - Field site Two replicated sites in Jamaican wet -limestone forest Data collected between Feb. 16 and Mar. 31, 2017 Peak of the dry season when food is most limited Three data sets collected concurrently Observed diet Foraging behavior Available prey

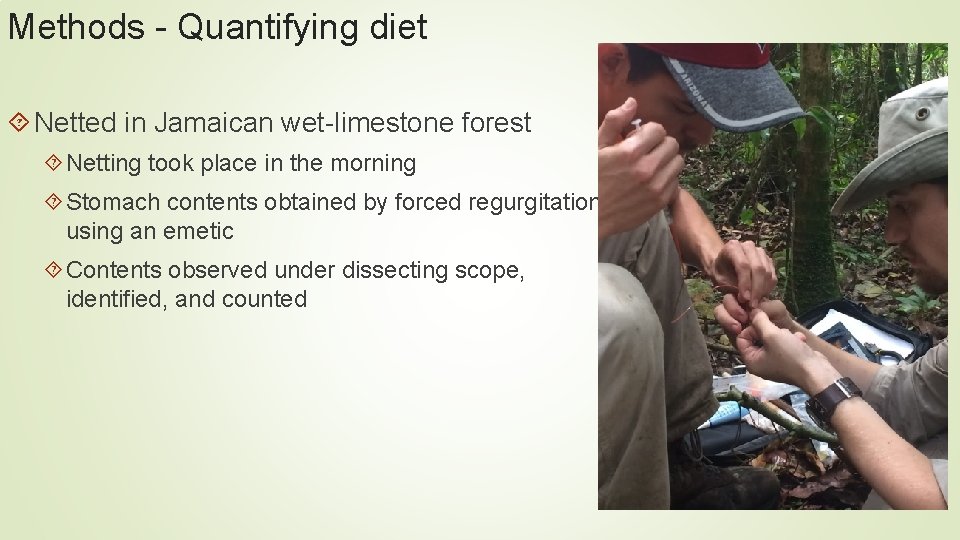

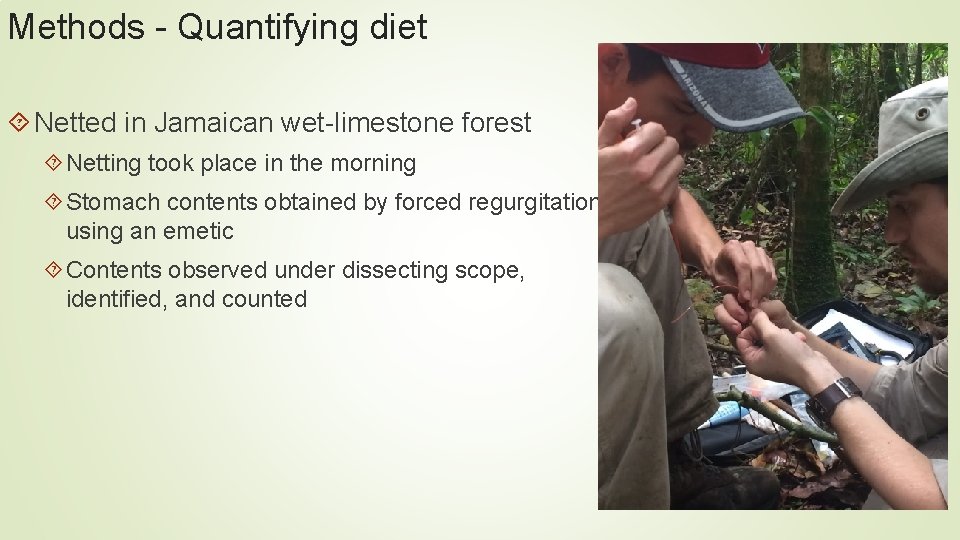

Methods - Quantifying diet Netted in Jamaican wet-limestone forest Netting took place in the morning Stomach contents obtained by forced regurgitation using an emetic Contents observed under dissecting scope, identified, and counted

Methods - Quantifying diet

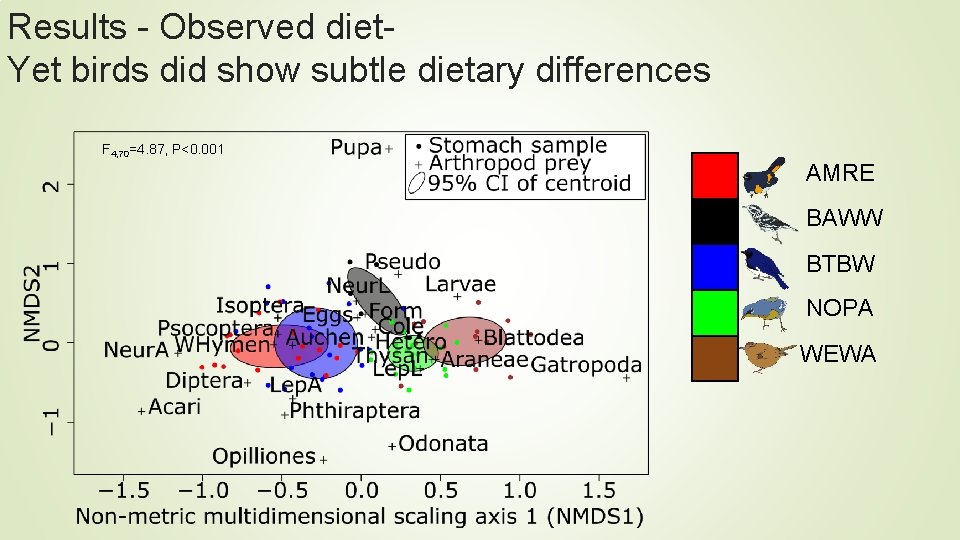

Methods - Quantifying diet Statistical Analysis Dietary overlap using Pianka’s index Differences in diet between species tested with PERMANOVA Visualized with NMDS

Methods - Foraging behavior of birds observed concurrently with diet sampling Observed actively foraging target species Recorded the height, maneuver, and substrate for all foraging attempts Differences in foraging behavior tested using a Bayesian categorical mixed model with the random effect of individual

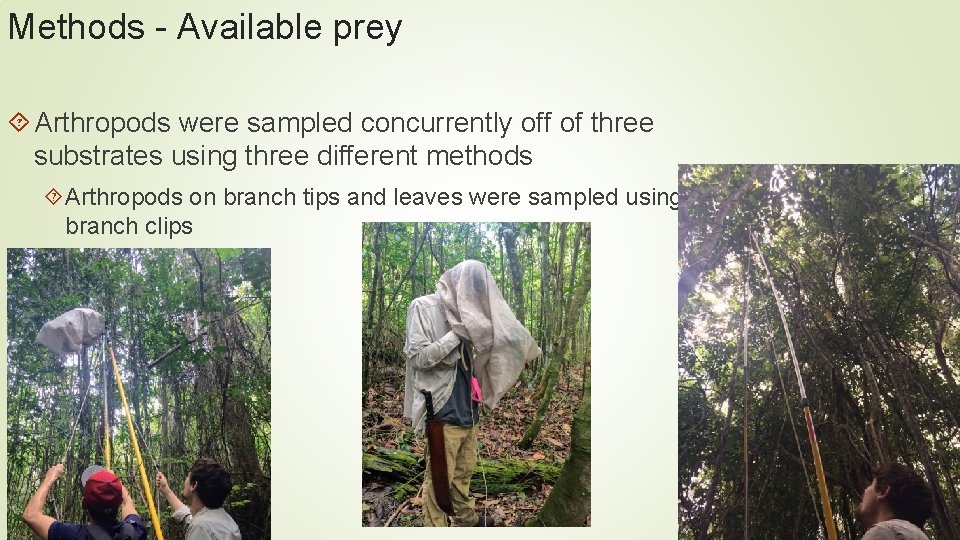

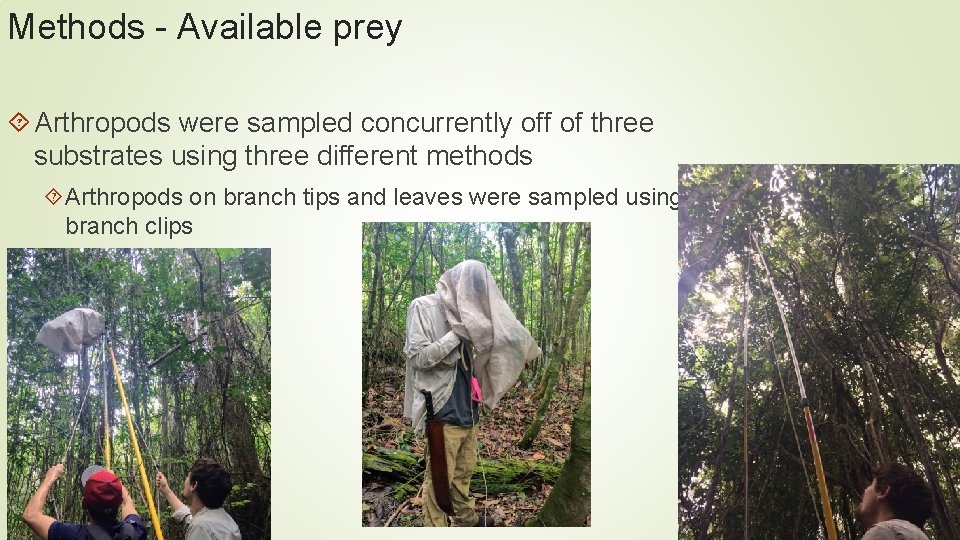

Methods - Available prey Arthropods were sampled concurrently off of three substrates using three different methods Arthropods on branch tips and leaves were sampled using branch clips

Methods - Available prey Arthropods were sampled concurrently off of three substrates using three different methods Arthropods on bark were sampled using sticky traps wrapped around trunks

Methods - Available prey Arthropods were sampled concurrently off of three substrates using three different methods Arthropods in the airspace sample using sticky trap suspended from branches

Results

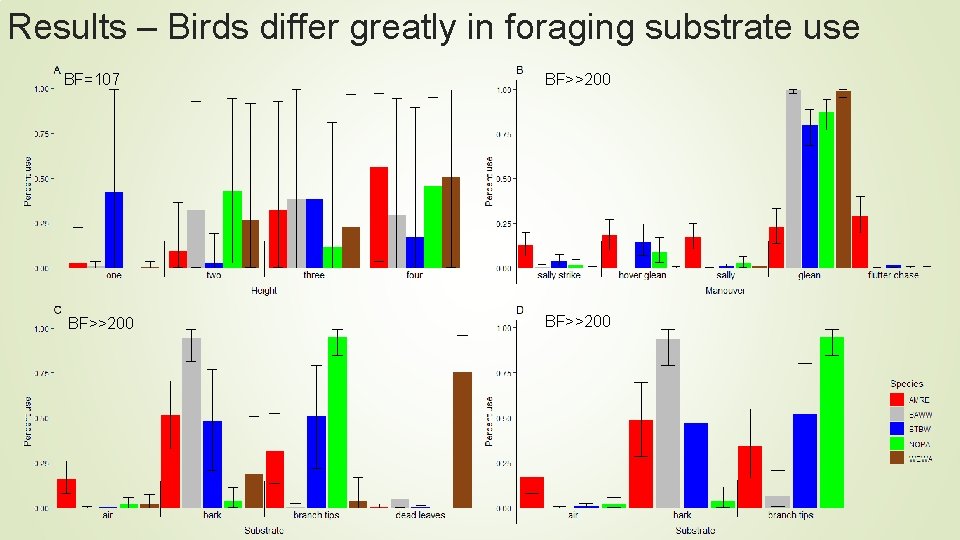

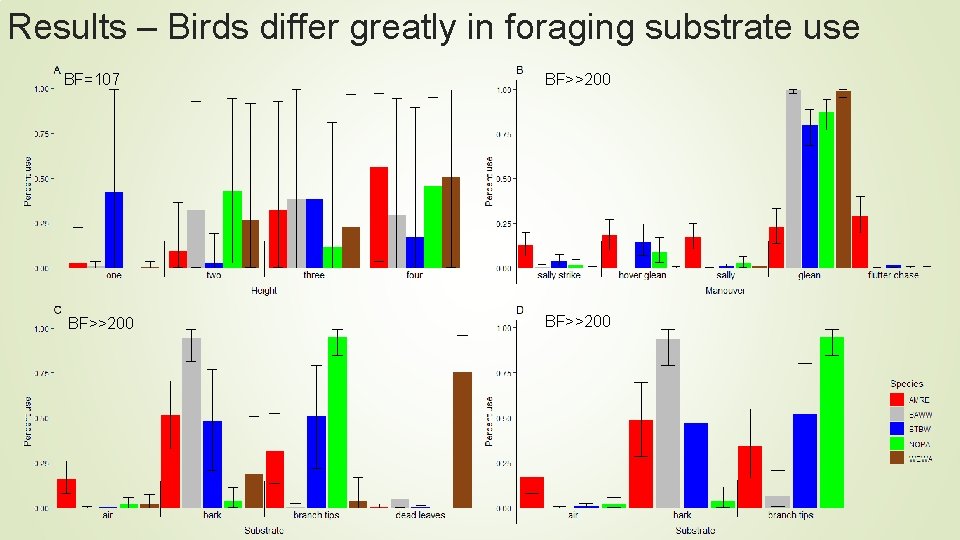

Results – Birds differ greatly in foraging substrate use BF=107 BF>>200

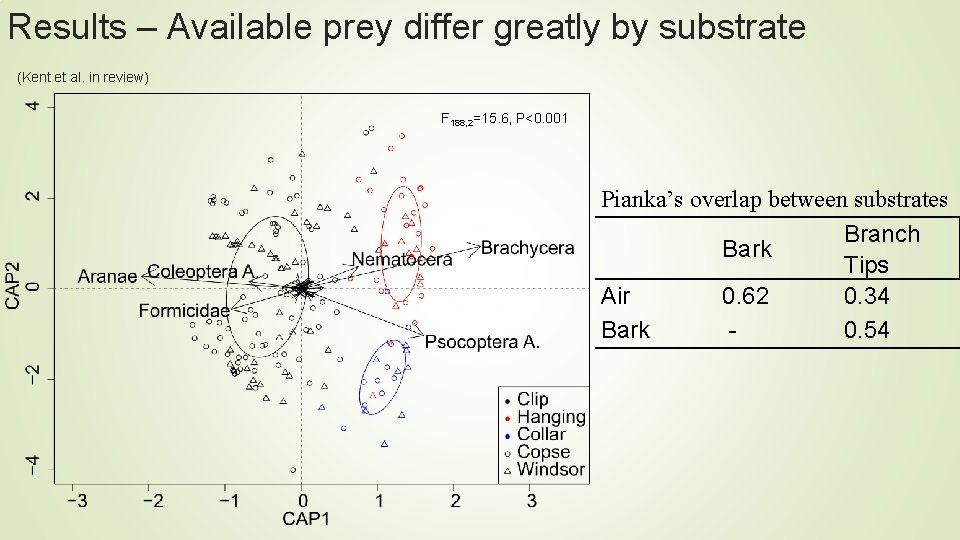

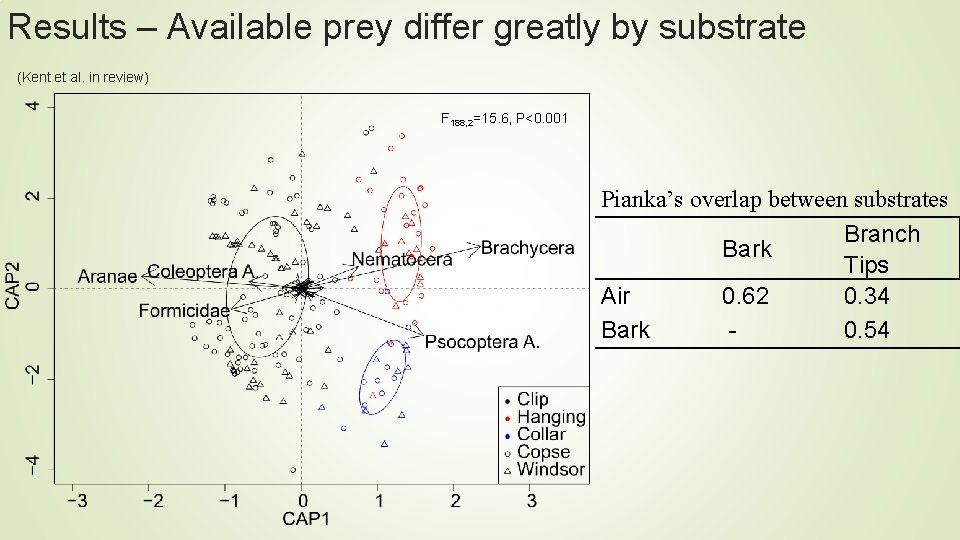

Results – Available prey differ greatly by substrate (Kent et al. in review) F 188, 2=15. 6, P<0. 001 Pianka’s overlap between substrates Branch Bark Tips Air 0. 62 0. 34 Bark 0. 54

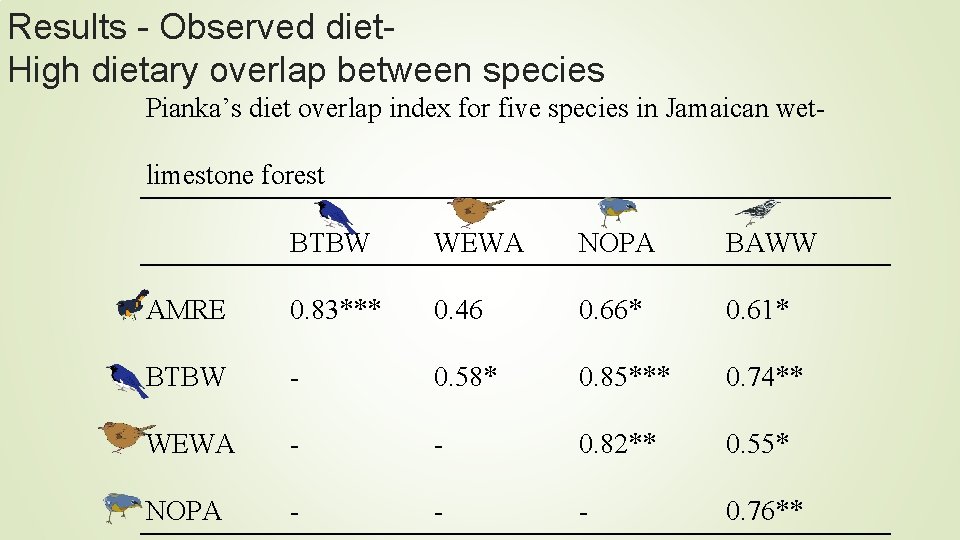

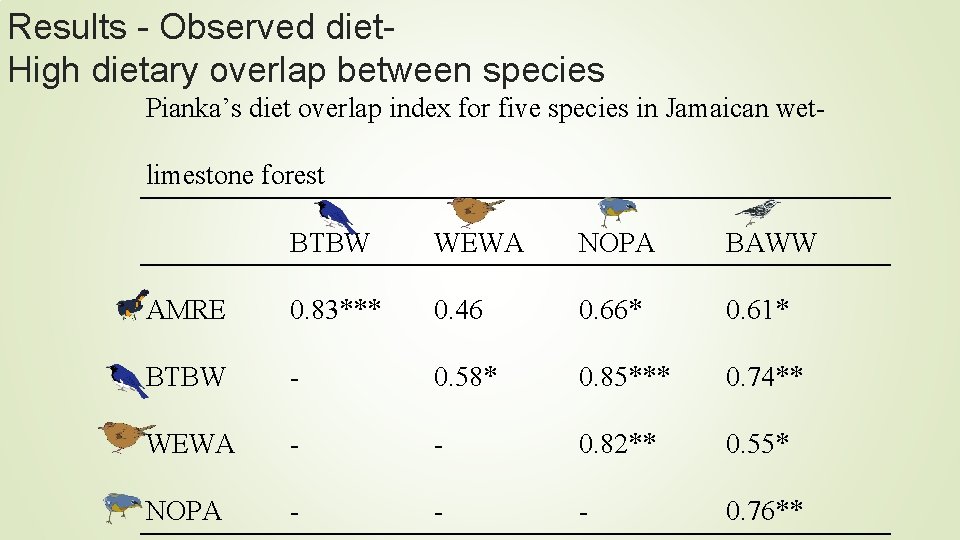

Results - Observed diet. High dietary overlap between species Pianka’s diet overlap index for five species in Jamaican wetlimestone forest BTBW WEWA NOPA BAWW AMRE 0. 83*** 0. 46 0. 66* 0. 61* BTBW - 0. 58* 0. 85*** 0. 74** WEWA - - 0. 82** 0. 55* NOPA - - - 0. 76**

Results - Observed diet. Overlap driven by ants

Results - Observed diet. Ants do not differ between species F 4, 49=0. 67, P=0. 61

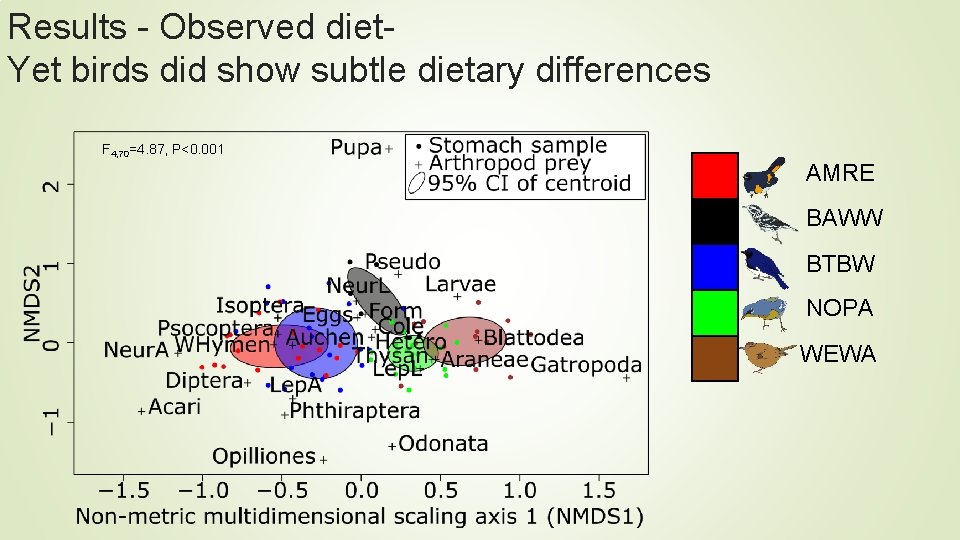

Results - Observed diet. Yet birds did show subtle dietary differences F 4, 70=4. 87, P<0. 001 AMRE BAWW BTBW NOPA WEWA

Part 2: are the small differences we see explained by behavior?

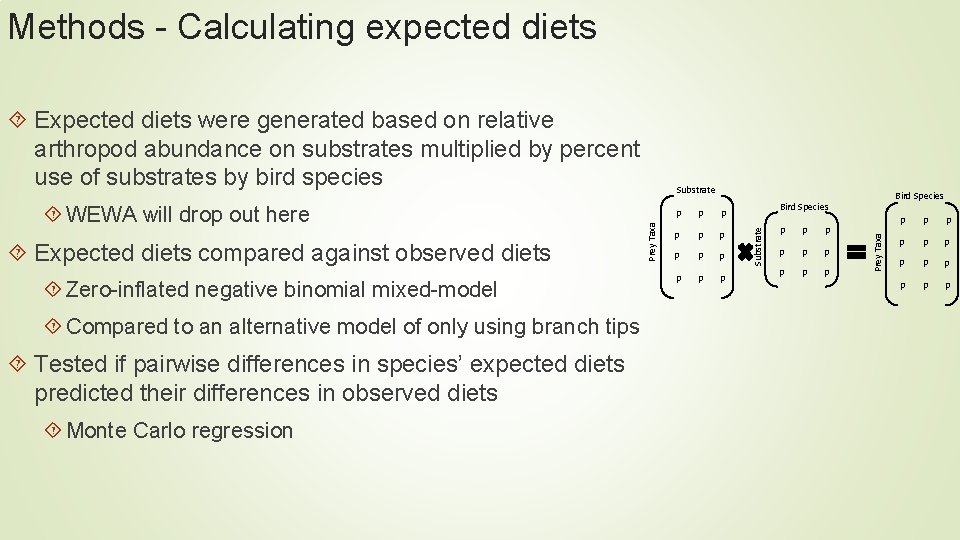

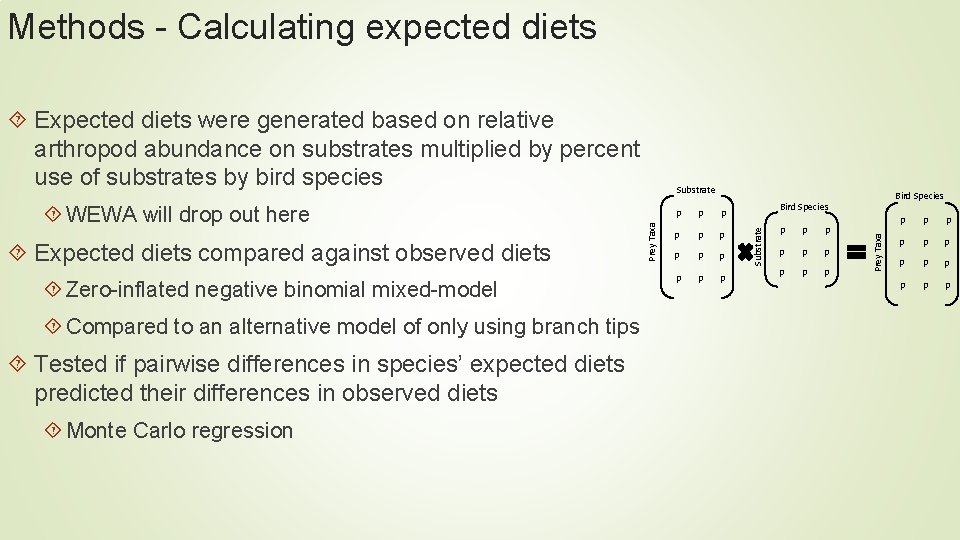

Methods - Calculating expected diets Expected diets were generated based on relative arthropod abundance on substrates multiplied by percent use of substrates by bird species Zero-inflated negative binomial mixed-model Compared to an alternative model of only using branch tips Tested if pairwise differences in species’ expected diets predicted their differences in observed diets Monte Carlo regression p p p p p Prey Taxa p Bird Species Substrate Expected diets compared against observed diets p Prey Taxa WEWA will drop out here Substrate p p p

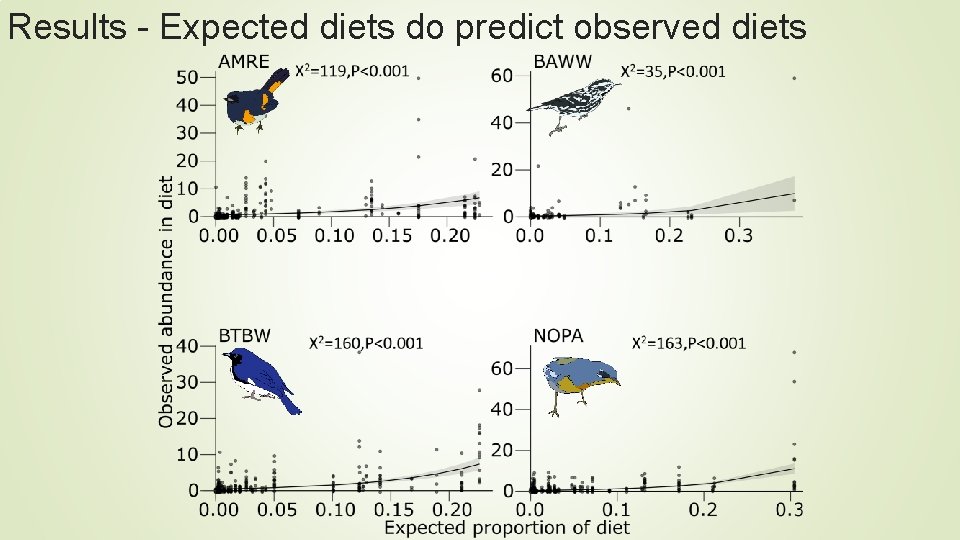

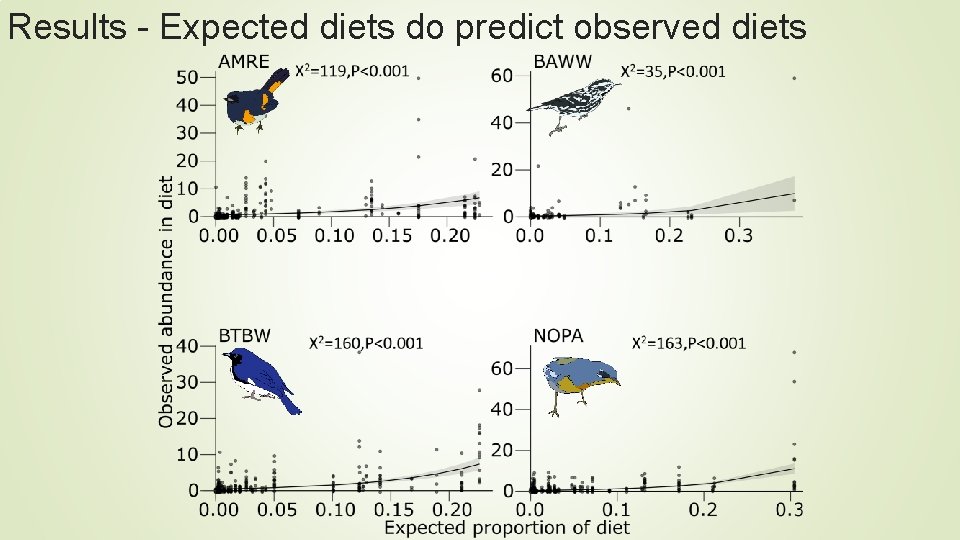

Results - Expected diets do predict observed diets

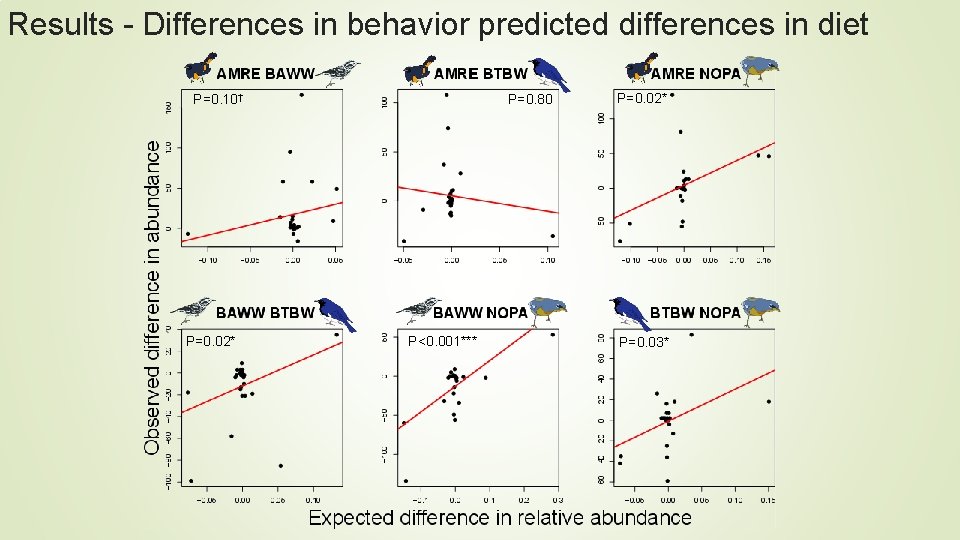

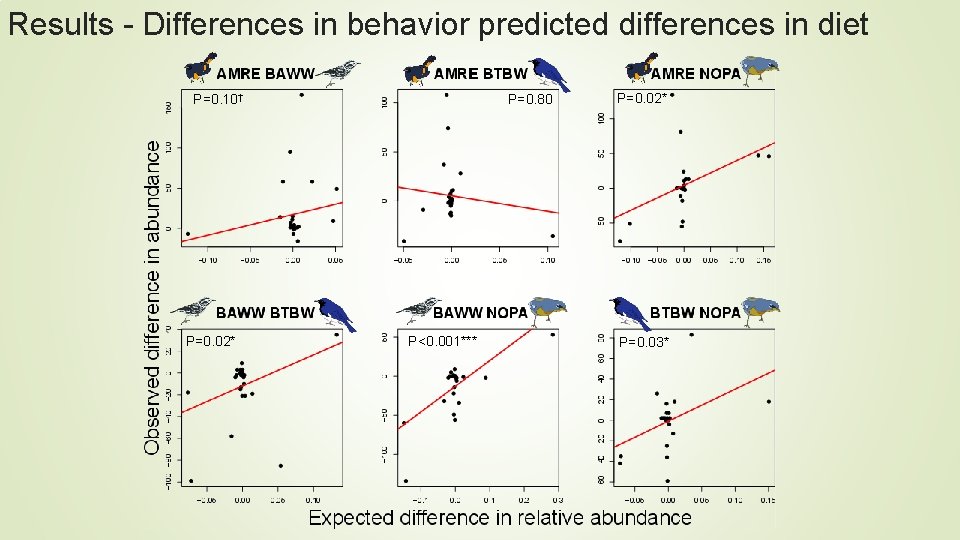

Results - Differences in behavior predicted differences in diet P=0. 10† P=0. 02* P=0. 80 P<0. 001*** P=0. 02* P=0. 03*

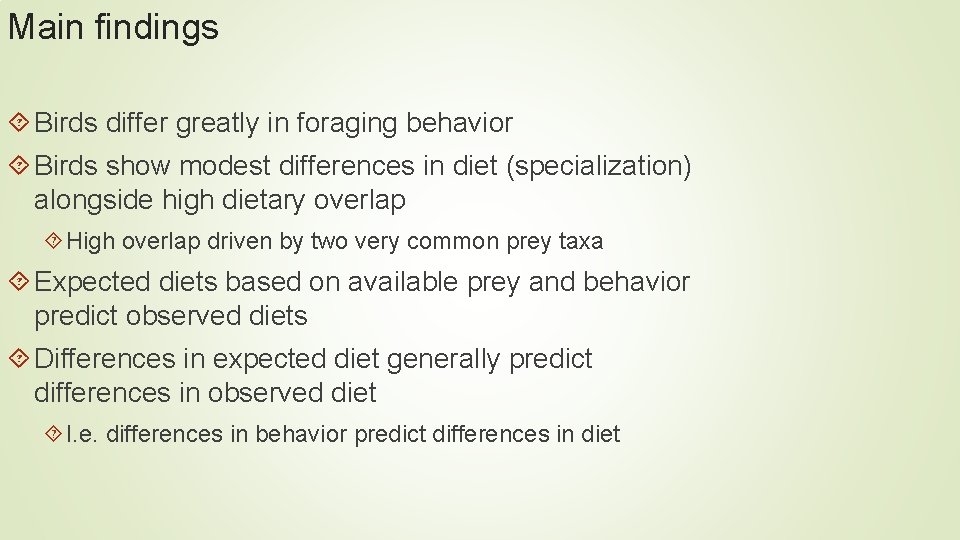

Main findings Birds differ greatly in foraging behavior Birds show modest differences in diet (specialization) alongside high dietary overlap High overlap driven by two very common prey taxa Expected diets based on available prey and behavior predict observed diets Differences in expected diet generally predict differences in observed diet I. e. differences in behavior predict differences in diet

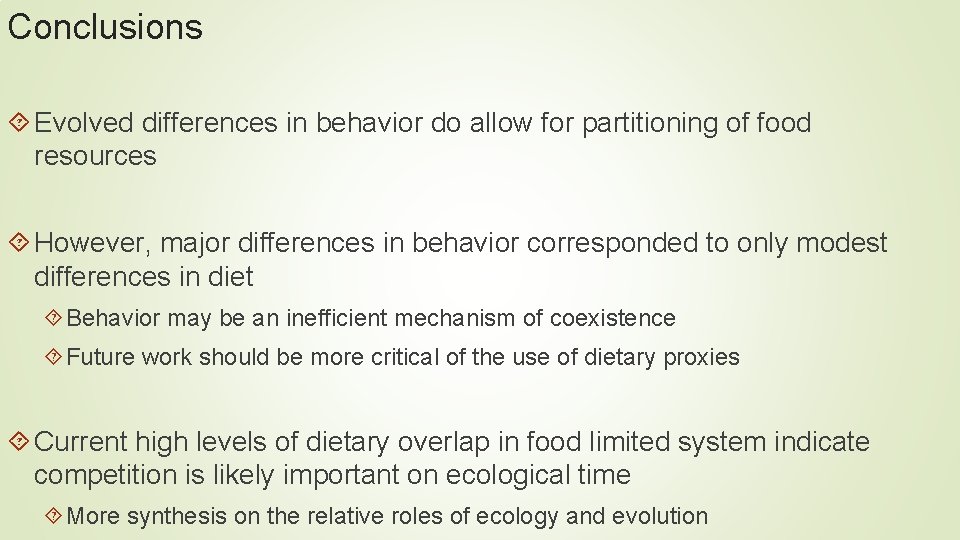

Conclusions Evolved differences in behavior do allow for partitioning of food resources However, major differences in behavior corresponded to only modest differences in diet Behavior may be an inefficient mechanism of coexistence Future work should be more critical of the use of dietary proxies Current high levels of dietary overlap in food limited system indicate competition is likely important on ecological time More synthesis on the relative roles of ecology and evolution

Acknowledgements Field Assistants Allan Moss Jayson Brunner Lab Assistants Molly Fava Kristen Rosamond Julie Nguyen Bird art by Kelli Mc. Kee Funding NSF Tulane Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Questions?