A Counterexample to Strong Parallel Repetition Raz Weizmann

![Parallel Repetition Theorem [R 95]: 8 G Val(G) < 1 ) 9 w < Parallel Repetition Theorem [R 95]: 8 G Val(G) < 1 ) 9 w <](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-7.jpg)

![Parallel Repetition Theorem: Val(G) = 1 , ( < ½) ) [R-95]: [Hol-06]: For Parallel Repetition Theorem: Val(G) = 1 , ( < ½) ) [R-95]: [Hol-06]: For](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-8.jpg)

![Applications of Parallel Repetition: 1) Communication Complexity: direct product results [PRW] 2) Geometry: understanding Applications of Parallel Repetition: 1) Communication Complexity: direct product results [PRW] 2) Geometry: understanding](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-10.jpg)

![PCP Theorem [BFL, FGLSS, ALMSS]: Given G (with constant answer size) It is NP PCP Theorem [BFL, FGLSS, ALMSS]: Given G (with constant answer size) It is NP](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-12.jpg)

![UGC and Max-Cut[KKMO]: UGC ) 8 > 0, given a graph G, It is UGC and Max-Cut[KKMO]: UGC ) 8 > 0, given a graph G, It is](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-14.jpg)

![Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m} Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m}](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-15.jpg)

![Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m} Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m}](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-16.jpg)

![Our Results: (match an upper bound of [FKO]) For n ¼ m 2, For Our Results: (match an upper bound of [FKO]) For n ¼ m 2, For](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-19.jpg)

![Holenstein’s Lemma [B, KT]: A has f: W ! R, B hasg: W ! Holenstein’s Lemma [B, KT]: A has f: W ! R, B hasg: W !](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-22.jpg)

![Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 2 / m Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 2 / m](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-23.jpg)

![Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 1) P(0) =£(1/m) Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 1) P(0) =£(1/m)](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-24.jpg)

![Follow Up Works: 1) Generalizations to unique games [BHHRRS] : Protocols for parallel repetition Follow Up Works: 1) Generalizations to unique games [BHHRRS] : Protocols for parallel repetition](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-30.jpg)

- Slides: 31

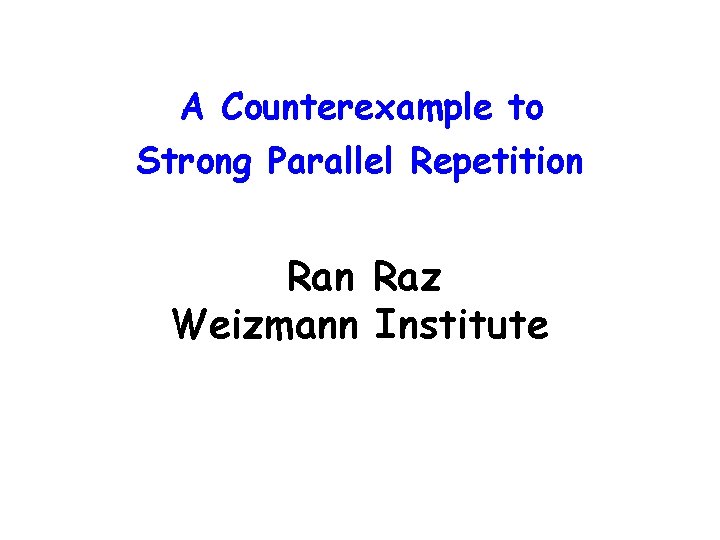

A Counterexample to Strong Parallel Repetition Raz Weizmann Institute

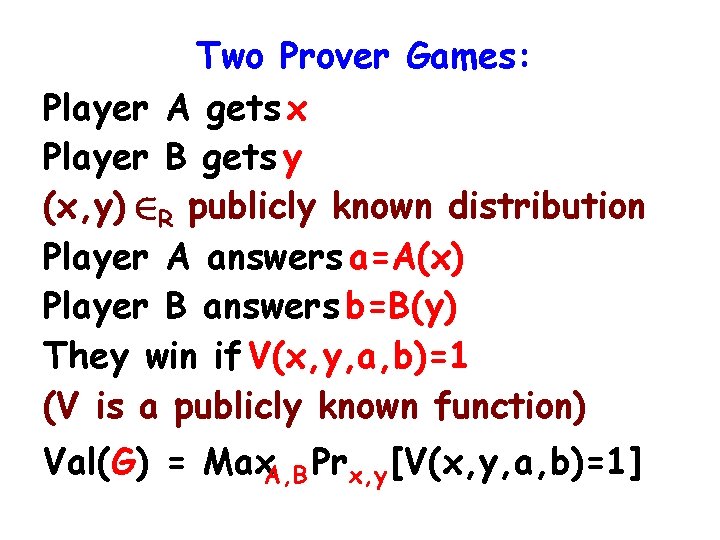

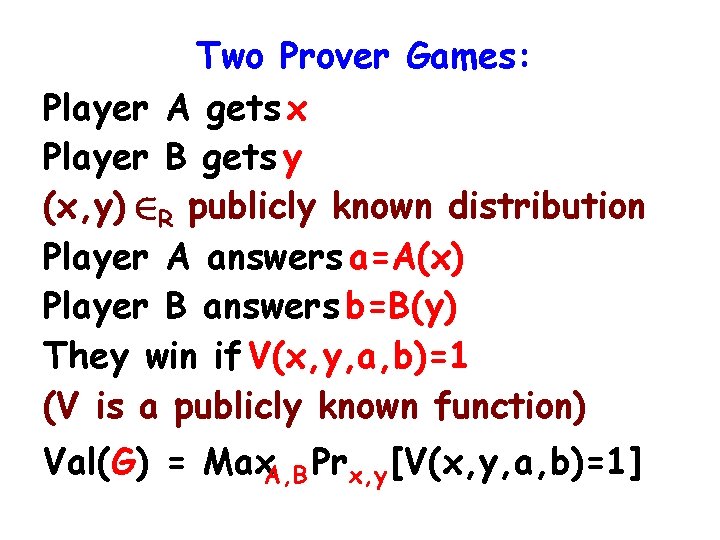

Two Prover Games: Player A gets x Player B gets y (x, y) 2 R publicly known distribution Player A answers a=A(x) Player B answers b=B(y) They win if V(x, y, a, b)=1 (V is a publicly known function) Val(G) = Max. A, B Prx, y [V(x, y, a, b)=1]

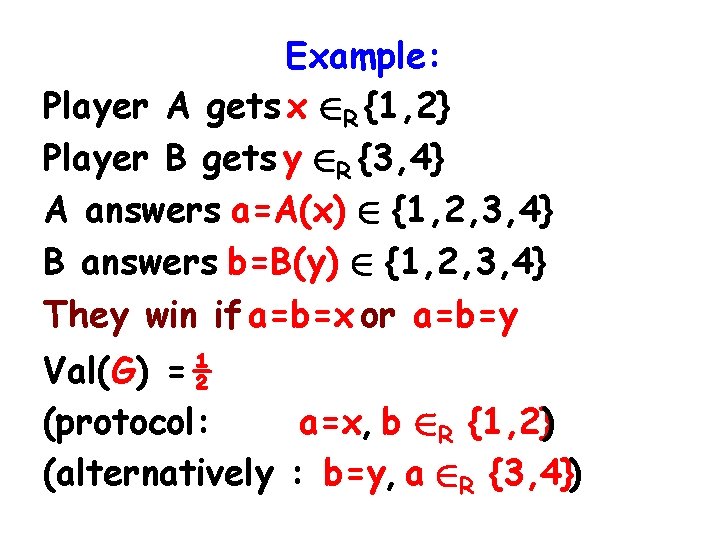

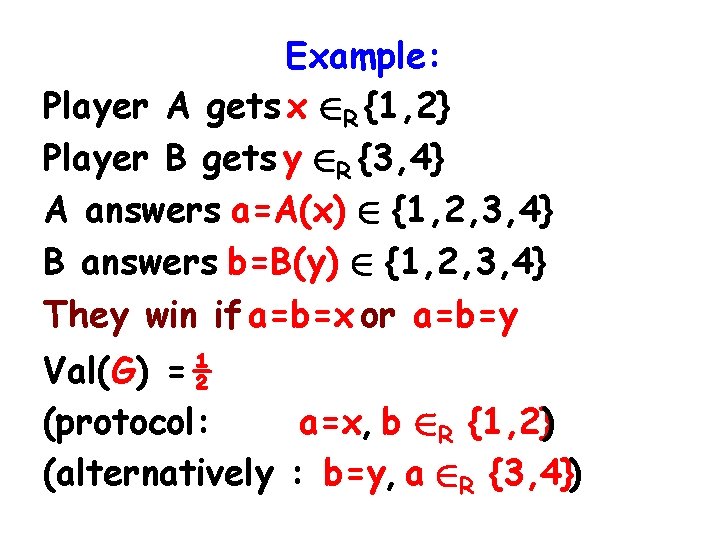

Example: Player A gets x 2 R {1, 2} Player B gets y 2 R {3, 4} A answers a=A(x) 2 {1, 2, 3, 4} B answers b=B(y) 2 {1, 2, 3, 4} They win if a=b=x or a=b=y Val(G) = ½ (protocol: a=x, b 2 R {1, 2}) (alternatively : b=y, a 2 R {3, 4})

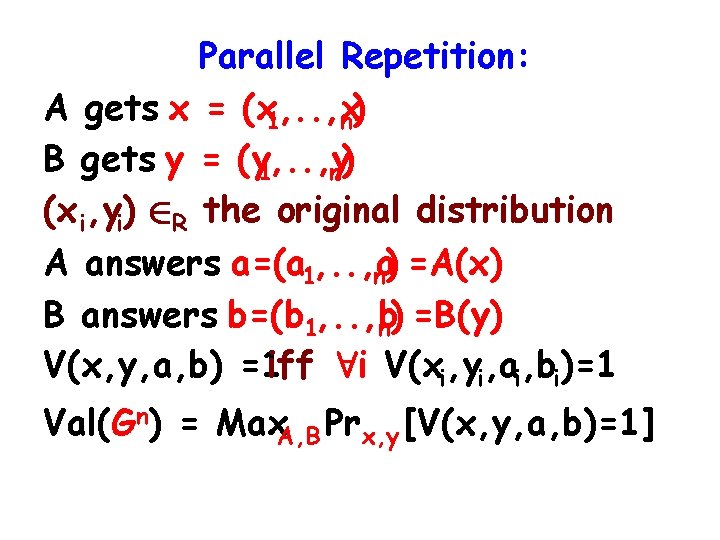

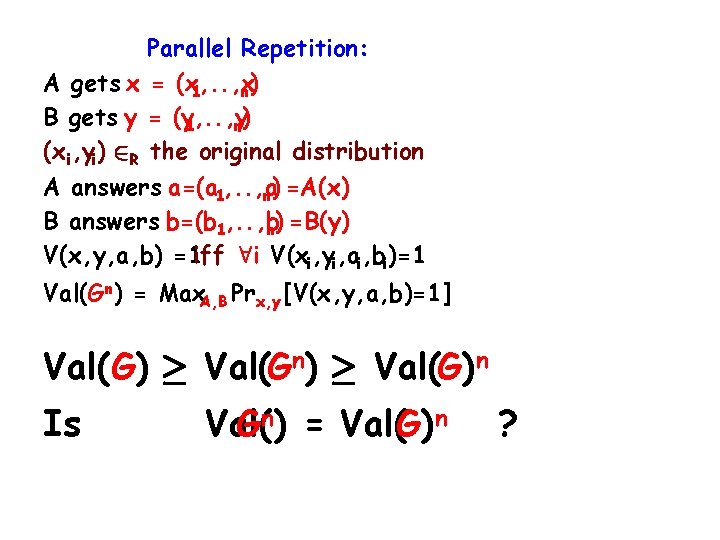

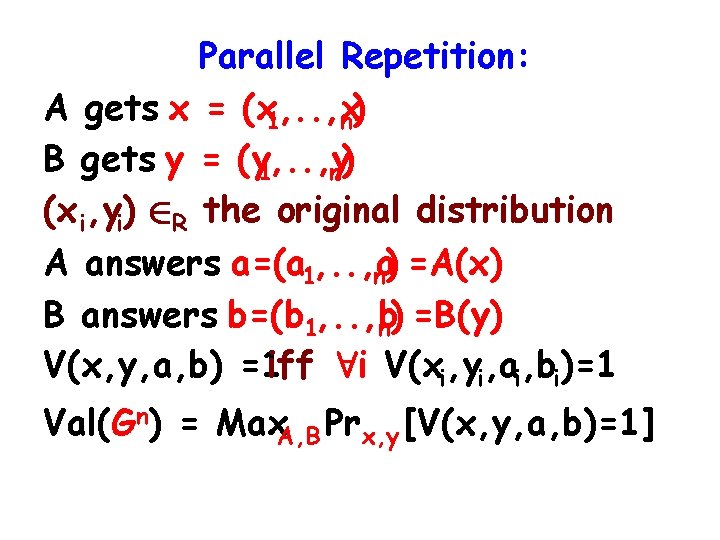

Parallel Repetition: A gets x = (x 1, . . , x n) B gets y = (y 1, . . , y n) (x i, yi) 2 R the original distribution A answers a=(a 1, . . , a n) =A(x) B answers b=(b 1, . . , b n) =B(y) V(x, y, a, b) =1 iff 8 i V(xi, yi, ai, bi)=1 Val(Gn) = Max. A, B Prx, y [V(x, y, a, b)=1]

Parallel Repetition: A gets x = (x 1, . . , x n) B gets y = (y 1, . . , y n) (x i, yi) 2 R the original distribution A answers a=(a 1, . . , a n) =A(x) B answers b=(b 1, . . , b n) =B(y) V(x, y, a, b) =1 iff 8 i V(xi, yi, ai, bi)=1 Val(Gn) = Max. A, B Prx, y [V(x, y, a, b)=1] Val(G) ¸ Val(Gn) ¸ Val(G)n Is Val( Gn) = Val(G)n ?

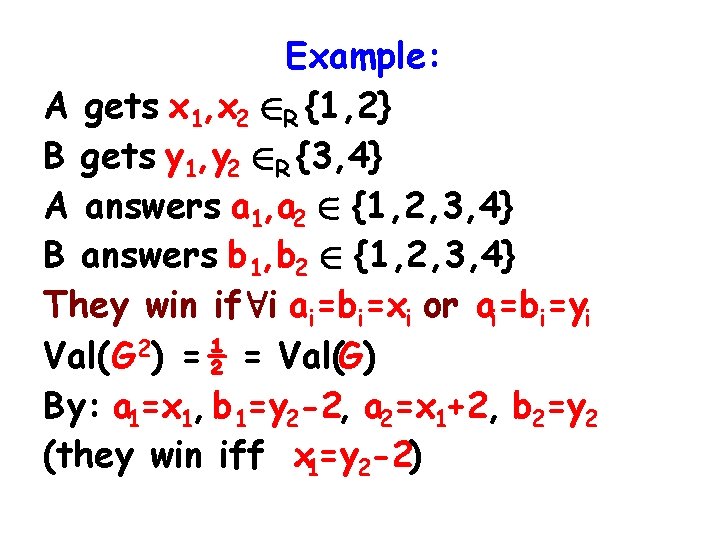

Example: A gets x 1, x 2 2 R {1, 2} B gets y 1, y 2 2 R {3, 4} A answers a 1, a 2 2 {1, 2, 3, 4} B answers b 1, b 2 2 {1, 2, 3, 4} They win if 8 i ai=bi=xi or ai=bi=yi Val(G 2) = ½ = Val(G) By: a 1=x 1, b 1=y 2 -2, a 2=x 1+2, b 2=y 2 (they win iff x 1=y 2 -2)

![Parallel Repetition Theorem R 95 8 G ValG 1 9 w Parallel Repetition Theorem [R 95]: 8 G Val(G) < 1 ) 9 w <](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-7.jpg)

Parallel Repetition Theorem [R 95]: 8 G Val(G) < 1 ) 9 w < 1 (s = length of answers in G) Assume that Val(G) = 1 What can we say aboutw ?

![Parallel Repetition Theorem ValG 1 ½ R95 Hol06 For Parallel Repetition Theorem: Val(G) = 1 , ( < ½) ) [R-95]: [Hol-06]: For](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-8.jpg)

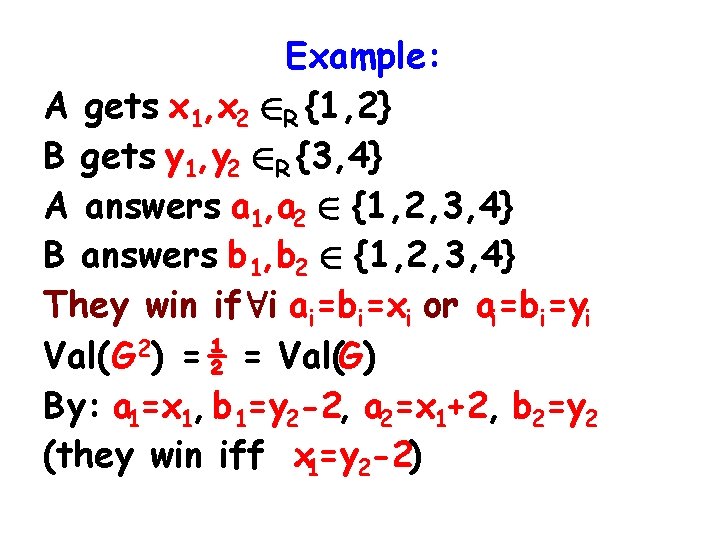

Parallel Repetition Theorem: Val(G) = 1 , ( < ½) ) [R-95]: [Hol-06]: For unique and projection games: [Rao-07]: (s = length of answers in G)

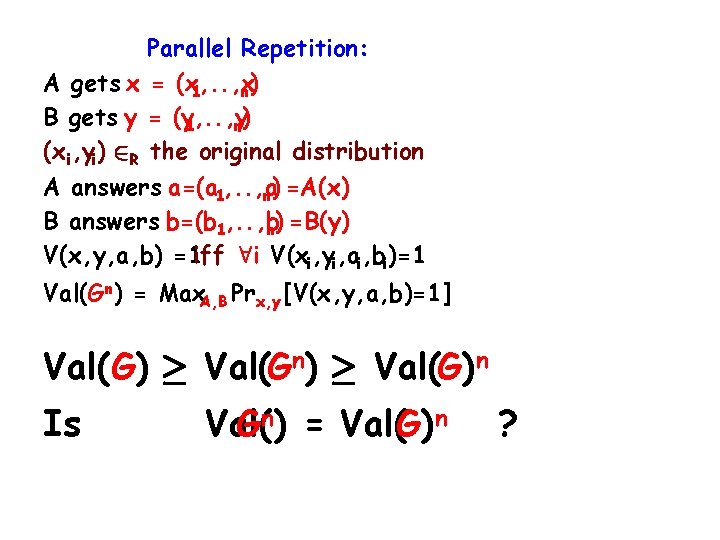

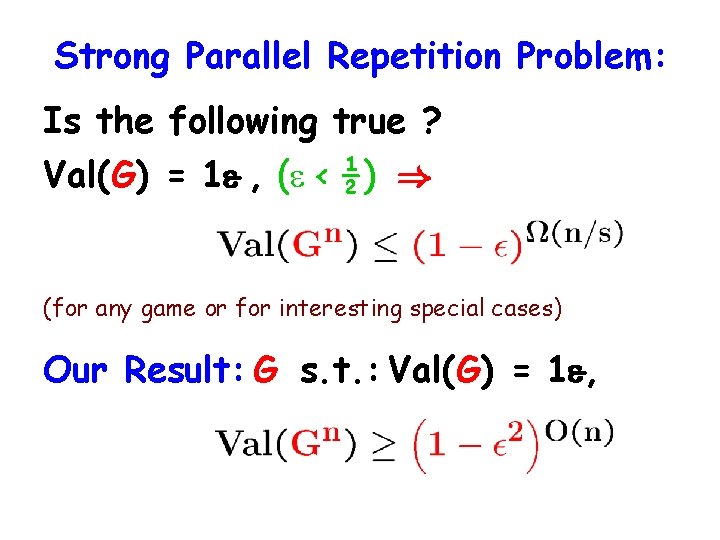

Strong Parallel Repetition Problem: Is the following true ? Val(G) = 1 , ( < ½) ) (for any game or for interesting special cases) Our Result: G s. t. : Val(G) = 1 ,

![Applications of Parallel Repetition 1 Communication Complexity direct product results PRW 2 Geometry understanding Applications of Parallel Repetition: 1) Communication Complexity: direct product results [PRW] 2) Geometry: understanding](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-10.jpg)

Applications of Parallel Repetition: 1) Communication Complexity: direct product results [PRW] 2) Geometry: understanding foams, tiling the space Rn [FKO] 3) Quantum Computation: strong EPR paradoxes [CHTW] 4) Hardness of Approximation: [BGS], [Has], [Fei], [Kho], . . .

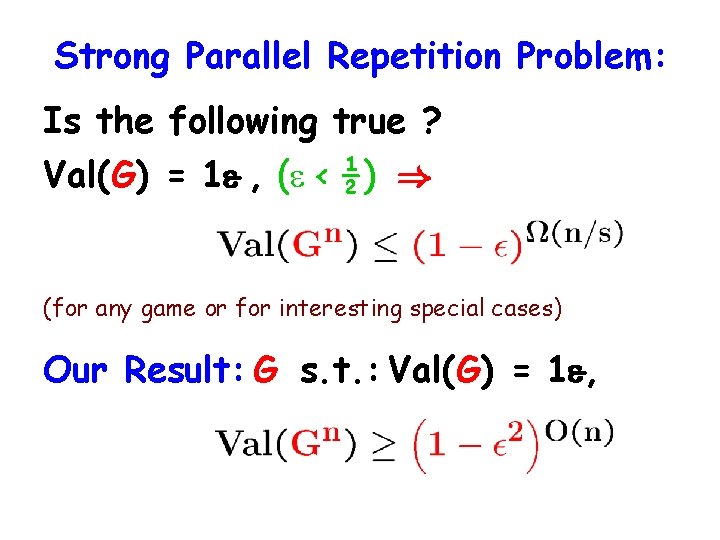

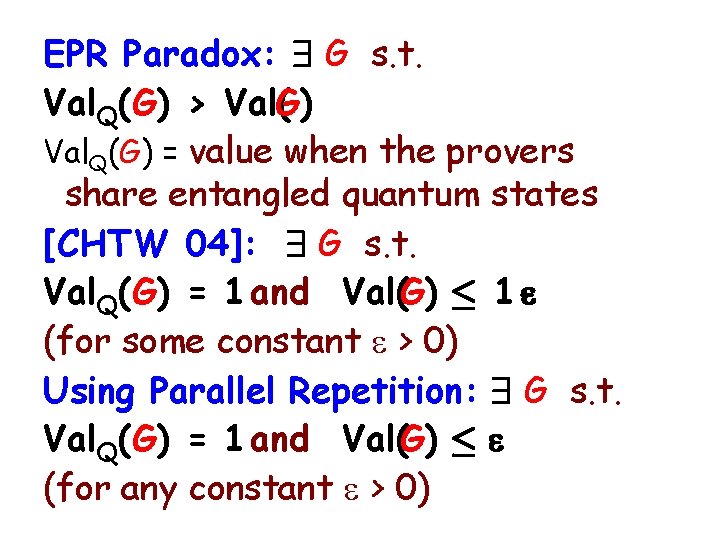

EPR Paradox: 9 G s. t. Val. Q(G) > Val(G) Val. Q(G) = value when the provers share entangled quantum states [CHTW 04]: 9 G s. t. Val. Q(G) = 1 and Val(G) · 1 - (for some constant > 0) Using Parallel Repetition: 9 G s. t. Val. Q(G) = 1 and Val(G) · (for any constant > 0)

![PCP Theorem BFL FGLSS ALMSS Given G with constant answer size It is NP PCP Theorem [BFL, FGLSS, ALMSS]: Given G (with constant answer size) It is NP](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-12.jpg)

PCP Theorem [BFL, FGLSS, ALMSS]: Given G (with constant answer size) It is NP hard to distinguish between : Val(G) = 1 and Val(G) · 1 - (for some constant > 0) Using Parallel Repetition : It is NP hard to distinguish between : Val(G) = 1 and Val(G) · (for any constant > 0)

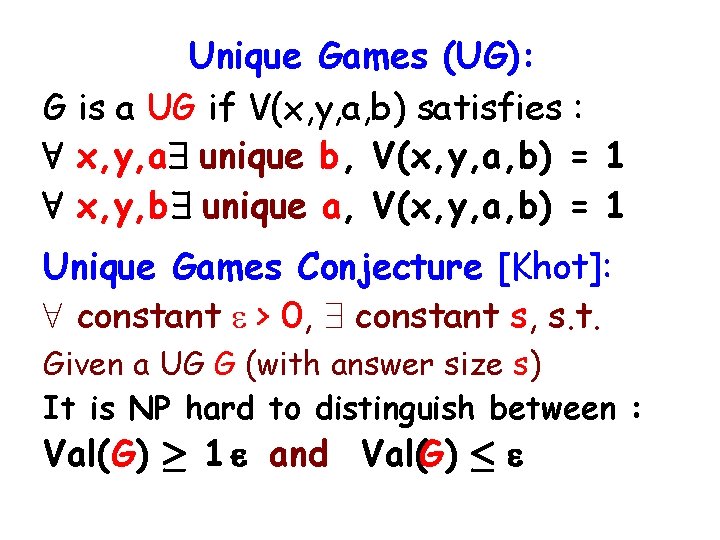

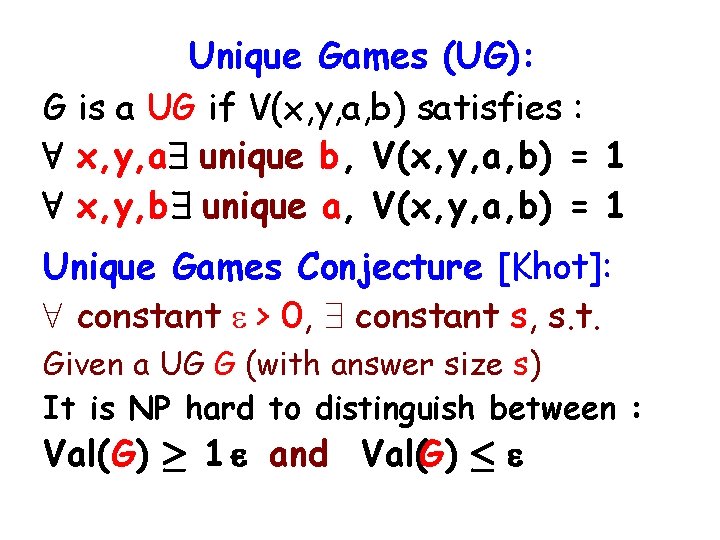

Unique Games (UG): G is a UG if V(x, y, a, b) satisfies : 8 x, y, a 9 unique b, V(x, y, a, b) = 1 8 x, y, b 9 unique a, V(x, y, a, b) = 1 Unique Games Conjecture [Khot]: 8 constant > 0, 9 constant s, s. t. Given a UG G (with answer size s) It is NP hard to distinguish between : Val(G) ¸ 1 - and Val(G) ·

![UGC and MaxCutKKMO UGC 8 0 given a graph G It is UGC and Max-Cut[KKMO]: UGC ) 8 > 0, given a graph G, It is](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-14.jpg)

UGC and Max-Cut[KKMO]: UGC ) 8 > 0, given a graph G, It is NP hard to distinguish between : Max-Cut(G) ¸ 1 - 2 and Max-Cut(G) · 1 -2 /p Using Strong Parallel Repetition : UGC , 8 > 0, given a graph G, It is NP hard to distinguish between : Max-Cut(G) ¸ 1 - 2 and Max-Cut(G) · 1 -2 /p

![Odd Cycle GameCHTW FKO A gets x 2 R 1 m Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m}](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-15.jpg)

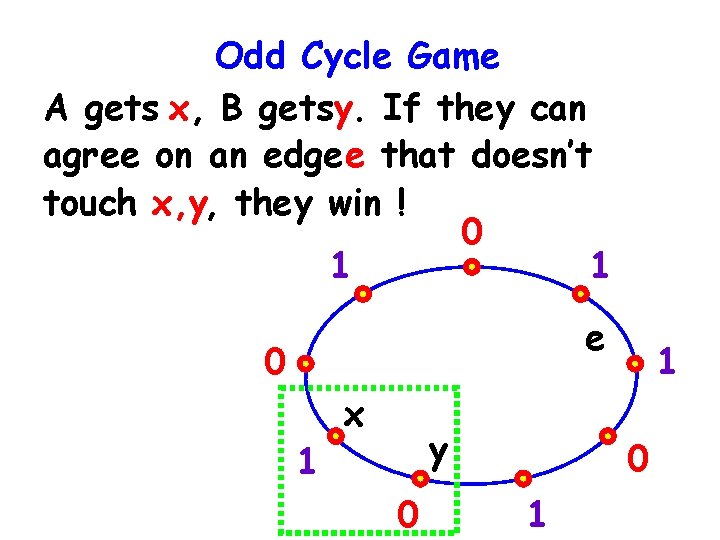

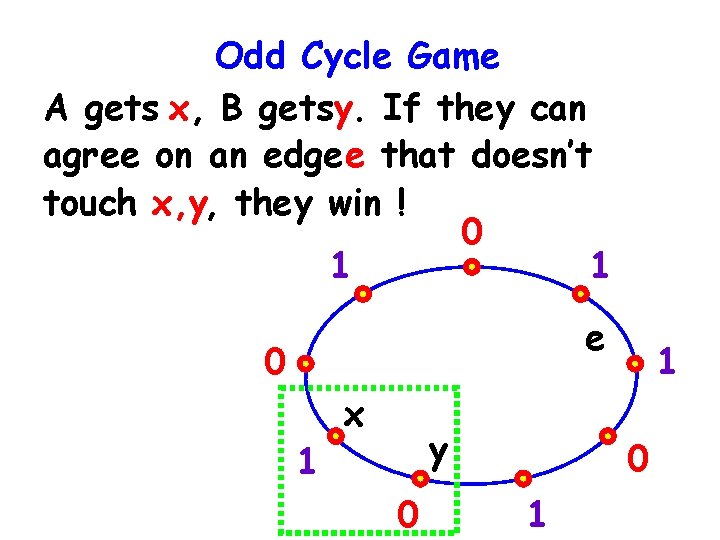

Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m} (m is odd) B gets y 2 R {x, x-1, x+1}(mod m) A answers a=A(x) 2 {0, 1} B answers b=B(y) 2 {0, 1} They win if x=y , a=b

![Odd Cycle GameCHTW FKO A gets x 2 R 1 m Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m}](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-16.jpg)

Odd Cycle Game[CHTW, FKO]: A gets x 2 R {1, . . , m} (m is odd) B gets y 2 R {x, x-1, x+1}(mod m) A answers a=A(x) 2 {0, 1} B answers b=B(y) 2 {0, 1} They win if x=y , a=b 1 0 0 1 1

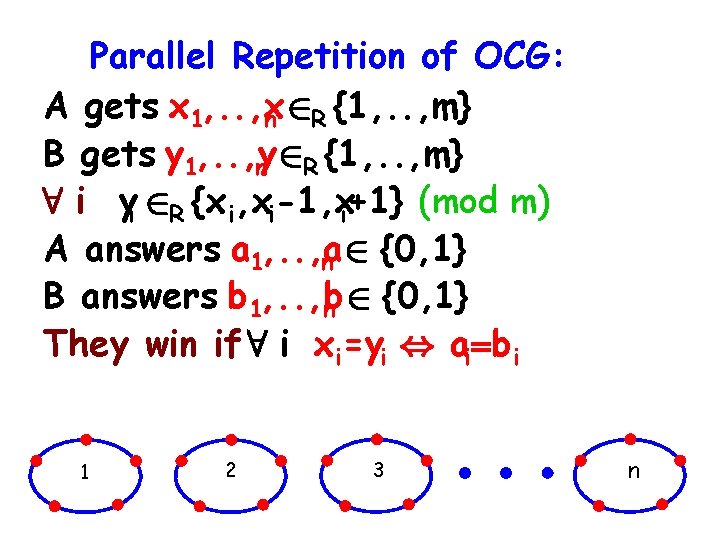

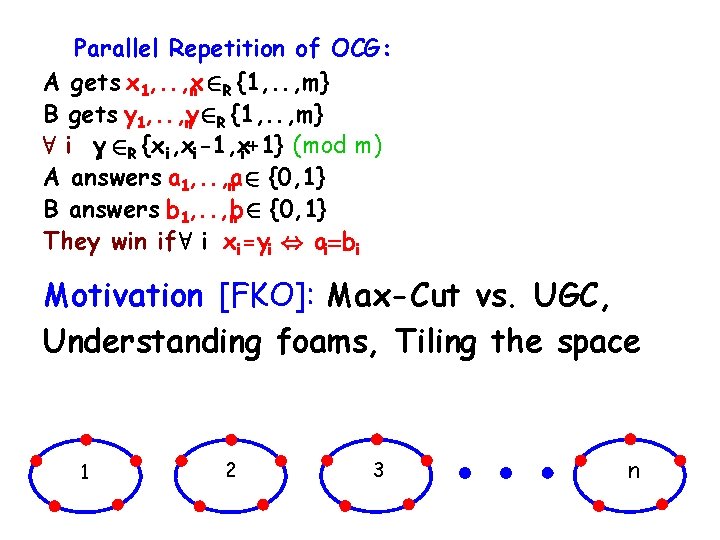

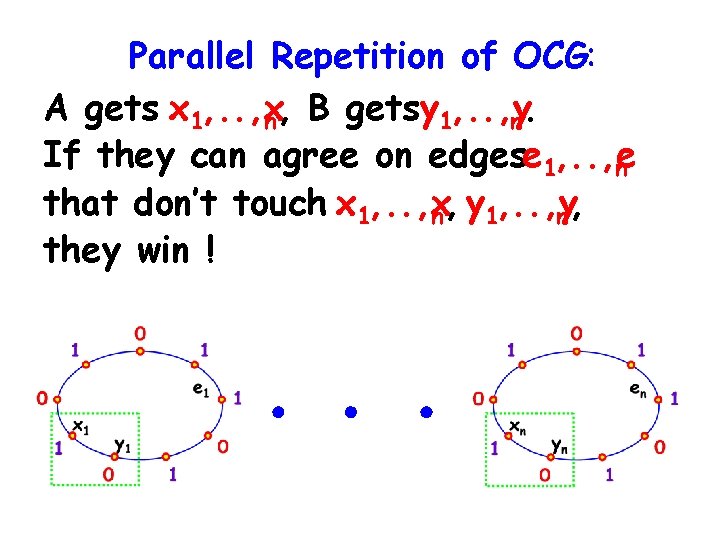

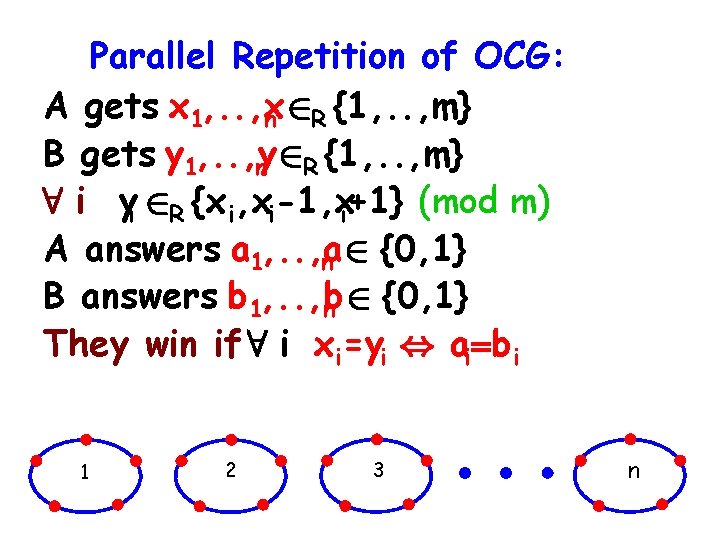

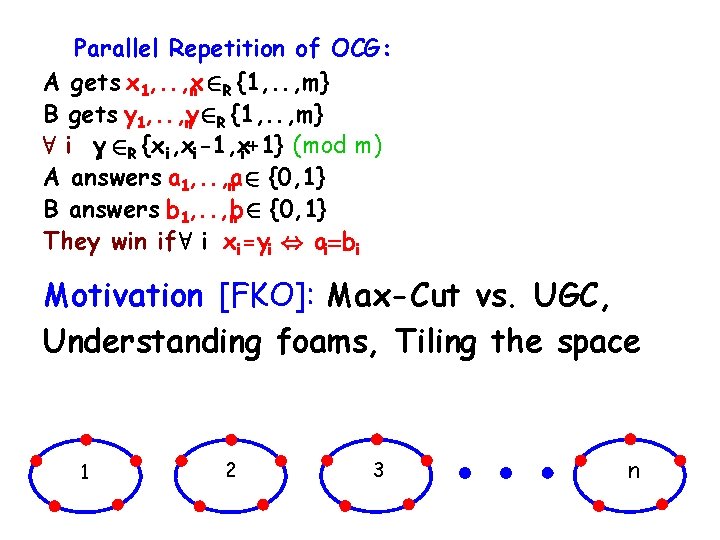

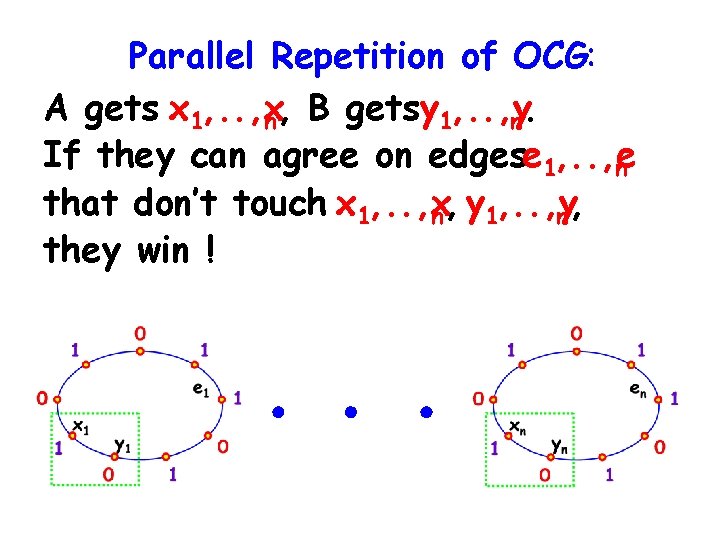

Parallel Repetition of OCG: A gets x 1, . . , x n 2 R {1, . . , m} B gets y 1, . . , y n 2 R {1, . . , m} 8 i yi 2 R {x i, xi-1, xi+1} (mod m) A answers a 1, . . , a n 2 {0, 1} B answers b 1, . . , b n 2 {0, 1} They win if 8 i xi=yi , ai=bi 1 2 3 n

Parallel Repetition of OCG: A gets x 1, . . , x n 2 R {1, . . , m} B gets y 1, . . , y n 2 R {1, . . , m} 8 i yi 2 R {x i, xi-1, xi+1} (mod m) A answers a 1, . . , a n 2 {0, 1} B answers b 1, . . , b n 2 {0, 1} They win if 8 i xi=yi , ai=bi Motivation [FKO]: Max-Cut vs. UGC, Understanding foams, Tiling the space 1 2 3 n

![Our Results match an upper bound of FKO For n ¼ m 2 For Our Results: (match an upper bound of [FKO]) For n ¼ m 2, For](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-19.jpg)

Our Results: (match an upper bound of [FKO]) For n ¼ m 2, For n ¸ (m 2), 1 2 3 n

Odd Cycle Game : A gets x, B getsy. If they can agree on an edgee that doesn’t touch x, y, they win ! 0 1 1 e 0 1 x y 0 1

Parallel Repetition of OCG: A gets x 1, . . , x n, B getsy 1, . . , y n. If they can agree on edgese 1, . . , e n that don’t touch x 1, . . , x n, y 1, . . , y n, they win !

![Holensteins Lemma B KT A has f W R B hasg W Holenstein’s Lemma [B, KT]: A has f: W ! R, B hasg: W !](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-22.jpg)

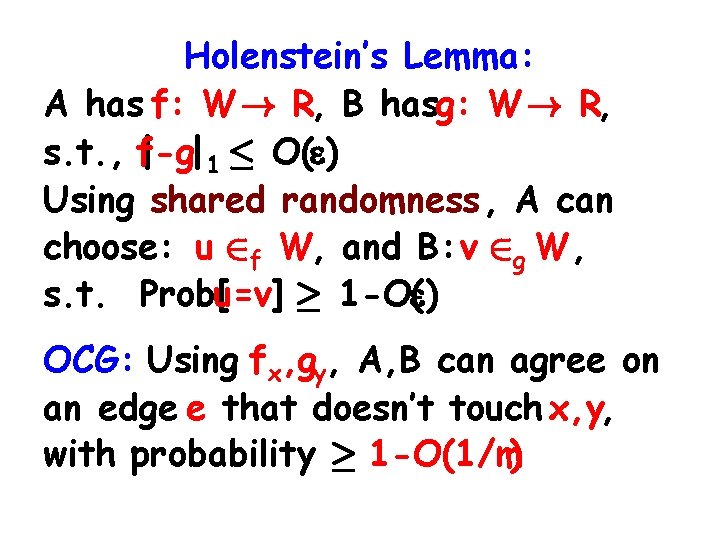

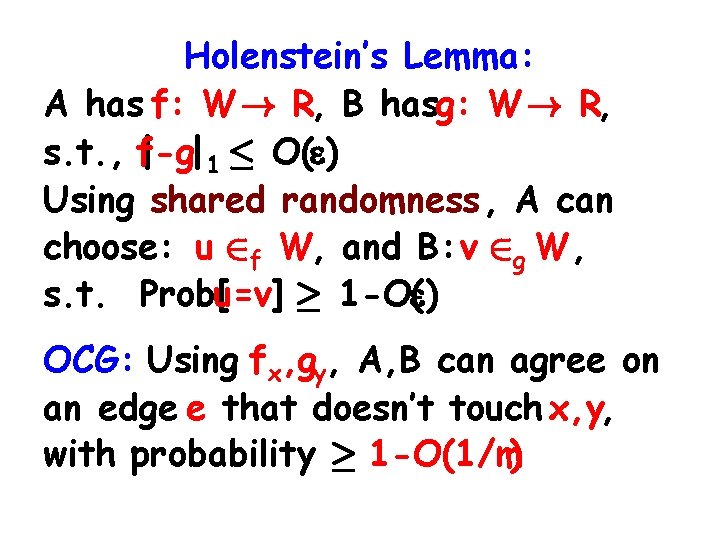

Holenstein’s Lemma [B, KT]: A has f: W ! R, B hasg: W ! R, s. t. , f-g| | 1 · O( ) Using shared randomness, A can choose: u 2 f W, and B: v 2 g W, s. t. Prob[u=v] ¸ 1 -O( )

![Distribution P m2 k1 P k k R symmetric 2 m Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 2 / m](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-23.jpg)

Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 2 / m 3 1) P(i) ¼ (k+1 -|i|) 2) P(0) = £(1/m) 3) P(k) = £(1/m 3) (negligible) -k k 1/m 3 1/m 0

![Distribution P m2 k1 P k k R symmetric 1 P0 1m Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 1) P(0) =£(1/m)](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-24.jpg)

Distribution P: m=2 k+1, P: [-k, k] ! R (symmetric) : 1) P(0) =£(1/m) 2) P(k) = P(-k) =£(1/m 3) (negligible) 3) -k k 1/m 3 1/m 0

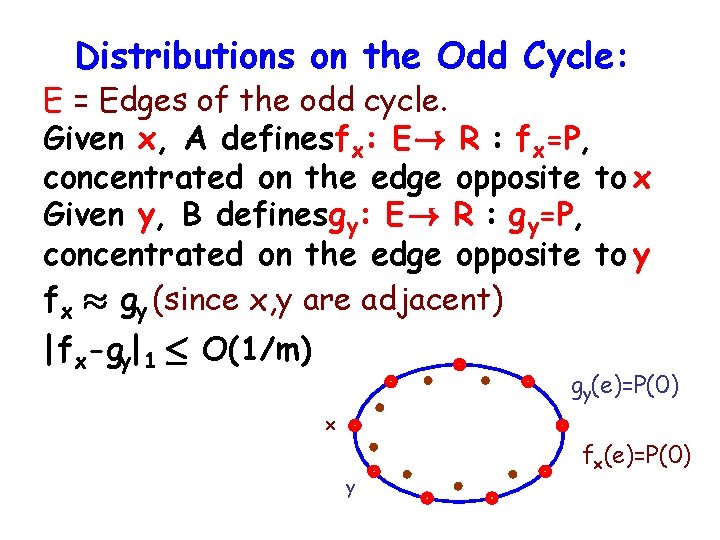

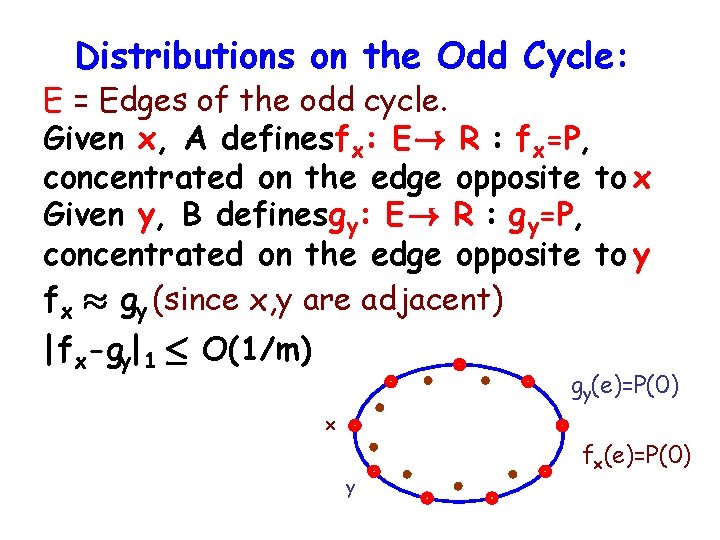

Distributions on the Odd Cycle: E = Edges of the odd cycle. Given x, A defines fx: E ! R : fx=P, concentrated on the edge opposite to x Given y, B defines gy: E ! R : gy=P, concentrated on the edge opposite to y fx ¼ gy (since x, y are adjacent) |f x-gy|1 · O(1/m) gy(e)=P(0) x fx(e)=P(0) y

Holenstein’s Lemma: A has f: W ! R, B hasg: W ! R, s. t. , f-g| | 1 · O( ) Using shared randomness, A can choose: u 2 f W, and B: v 2 g W, s. t. Prob[u=v] ¸ 1 -O( ) OCG: Using fx, gy, A, B can agree on an edge e that doesn’t touch x, y, with probability ¸ 1 -O(1/m)

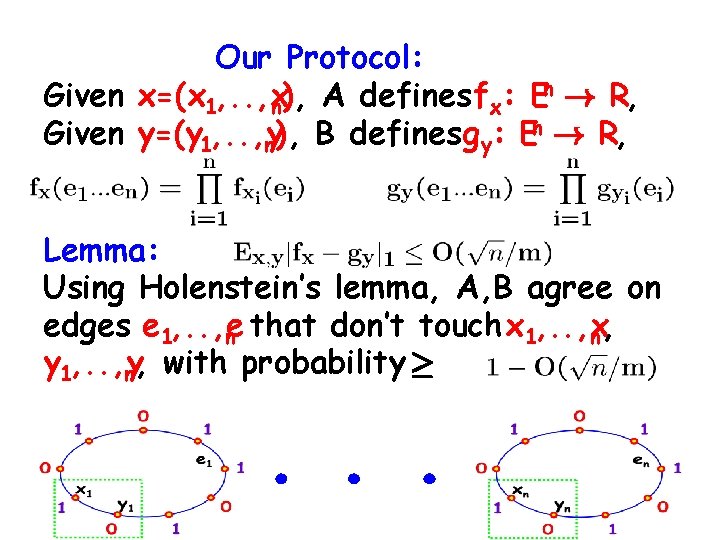

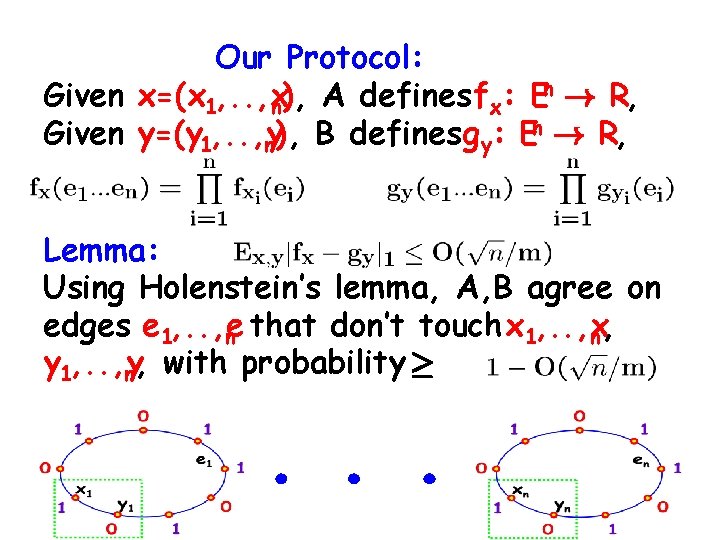

Our Protocol: n ! R, Given x=(x 1, . . , x ), A defines f : E n x n ! R, Given y=(y 1, . . , y ), B defines g : E n y Lemma: Using Holenstein’s lemma, A, B agree on edges e 1, . . , e n that don’t touch x 1, . . , x n, y 1, . . , y n, with probability ¸

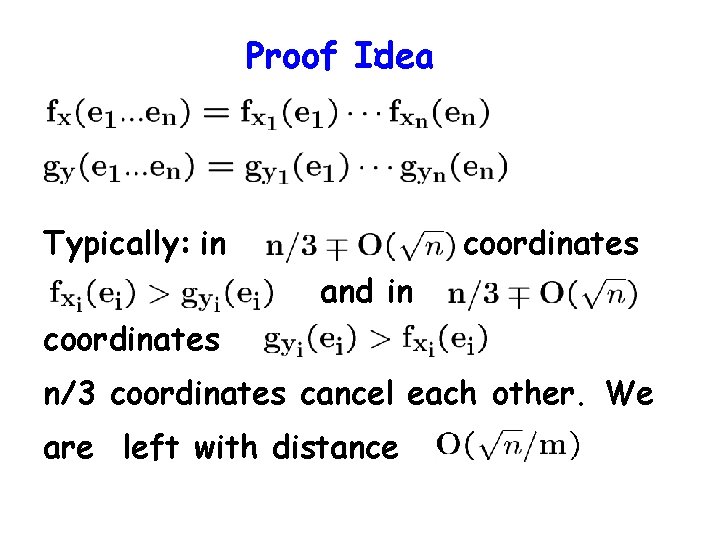

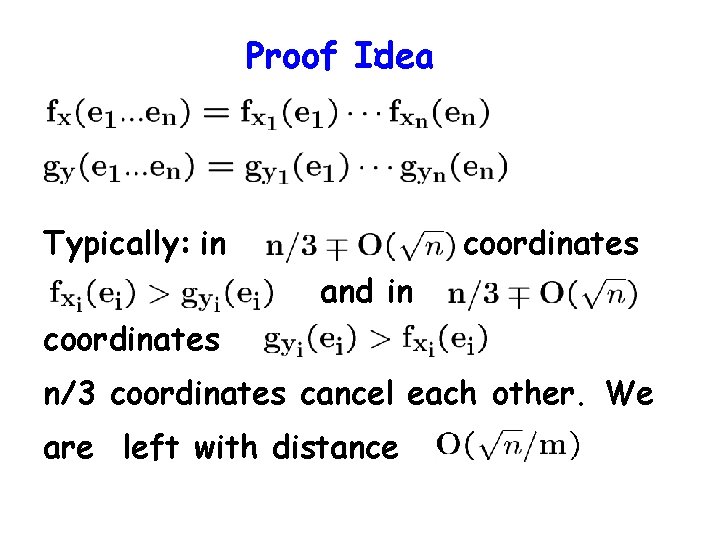

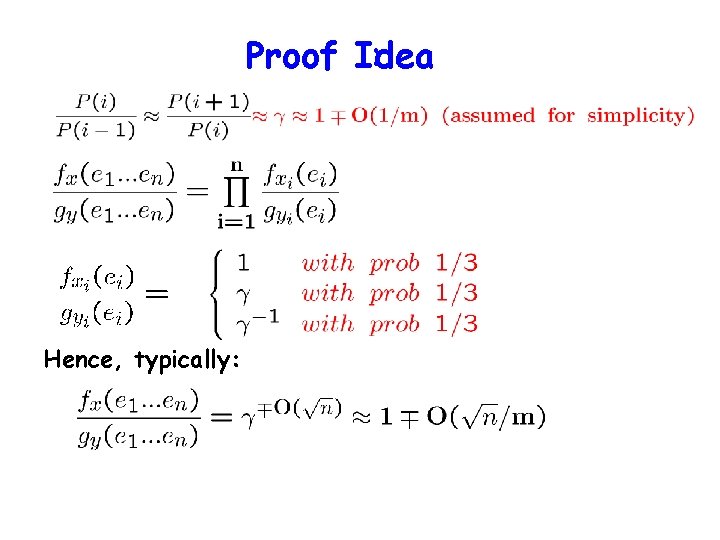

Proof Idea : Typically: in coordinates and in coordinates n/3 coordinates cancel each other. We are left with distance

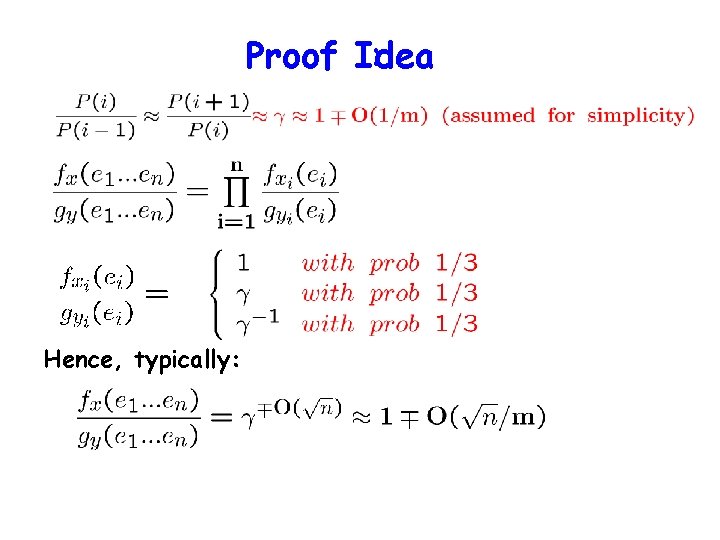

Proof Idea : Hence, typically:

![Follow Up Works 1 Generalizations to unique games BHHRRS Protocols for parallel repetition Follow Up Works: 1) Generalizations to unique games [BHHRRS] : Protocols for parallel repetition](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/41f693cb861542b8f25e3545a9789612/image-30.jpg)

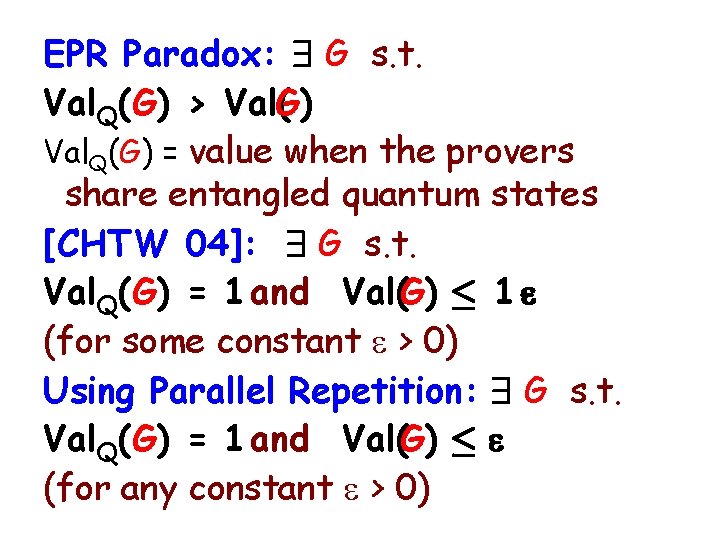

Follow Up Works: 1) Generalizations to unique games [BHHRRS] : Protocols for parallel repetition of any unique game 2) Tiling the space Rn [KORW, AK] : Rn can be tiled (with translations in Zn), by objects with surface area similar to the one of the sphere (with volume 1)

The End