A Confutation of Convergent Realism Larry Laudan Epistemological

- Slides: 19

A Confutation of Convergent Realism Larry Laudan

Epistemological realism: knowledge about an object is mindindependent. Problem: It is often suggested that epistemological realism is an empirical hypothesis: its grounding lies in its ability to explain the workings of science. It is empirically testable: it can be tested, essentially, by its success. Naturally, allowing epistemological claims to be testable means that preferred claims about epistemology might not stand up. Laudan’s claim is that this is precisely what has happened to epistemological realists of a certain type.

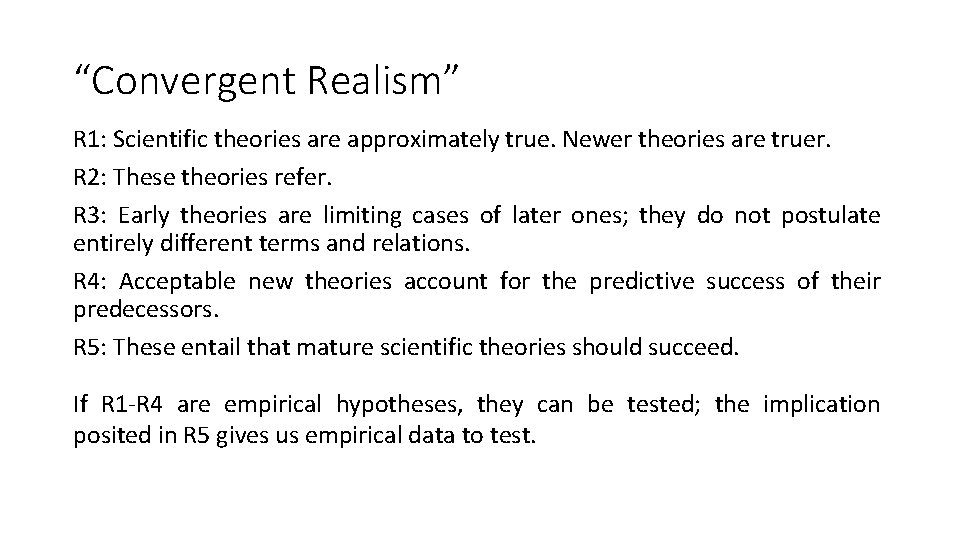

“Convergent Realism” R 1: Scientific theories are approximately true. Newer theories are truer. R 2: These theories refer. R 3: Early theories are limiting cases of later ones; they do not postulate entirely different terms and relations. R 4: Acceptable new theories account for the predictive success of their predecessors. R 5: These entail that mature scientific theories should succeed. If R 1 -R 4 are empirical hypotheses, they can be tested; the implication posited in R 5 gives us empirical data to test.

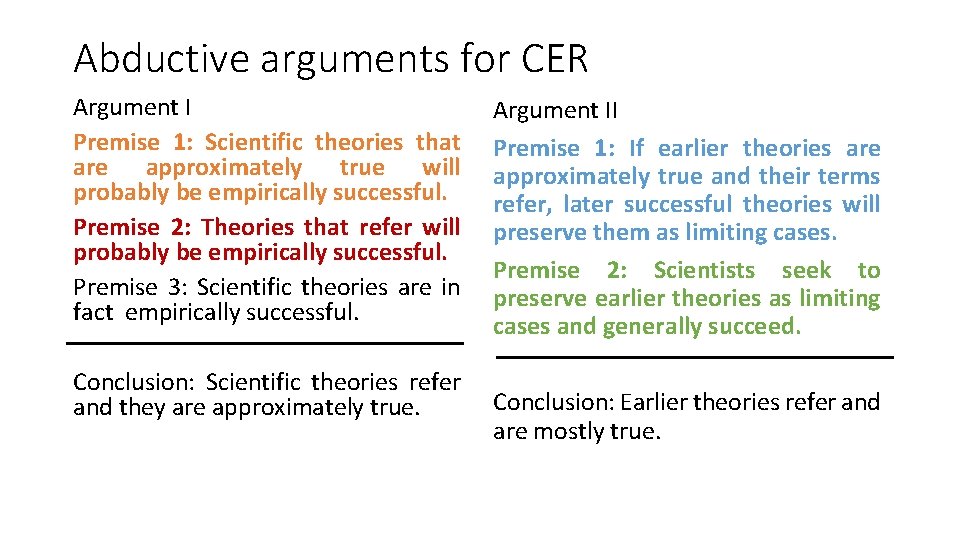

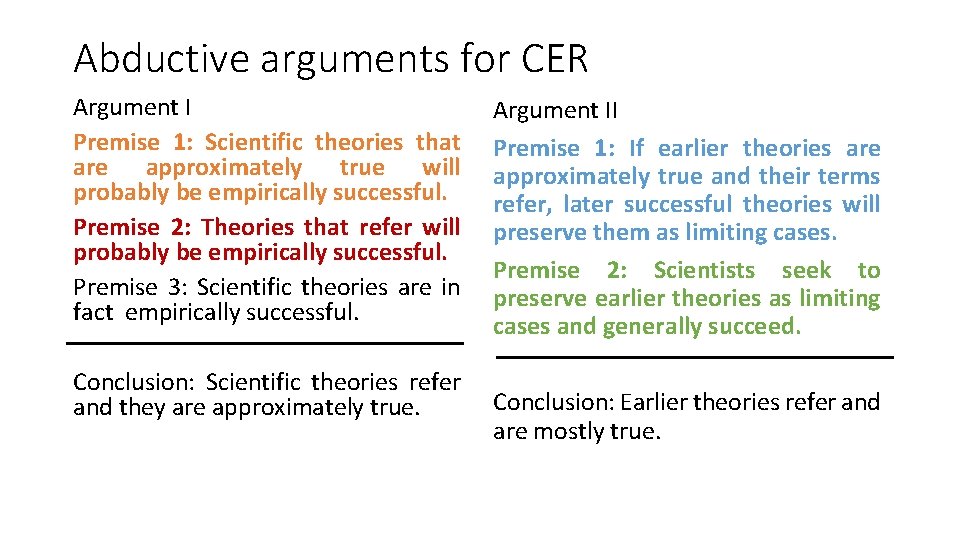

Abductive arguments for CER Argument I Premise 1: Scientific theories that are approximately true will probably be empirically successful. Premise 2: Theories that refer will probably be empirically successful. Premise 3: Scientific theories are in fact empirically successful. Conclusion: Scientific theories refer and they are approximately true. Argument II Premise 1: If earlier theories are approximately true and their terms refer, later successful theories will preserve them as limiting cases. Premise 2: Scientists seek to preserve earlier theories as limiting cases and generally succeed. Conclusion: Earlier theories refer and are mostly true.

“No miracles” argument If CER is true, we can rest easy about scientific success now and in the future. If CER is false, • Success of our theories is not guaranteed • Assuming success does occur, it is an unexplained, miraculous happening

Laudan’s approach • It is credible, or at least not a weak point, to say that scientific theories do succeed. • The claim that reference causes or explains success (I. 2) is false. • The notion of “approximate truth” is unclear; I. 1 is ambiguous. • As later theories do not (and in fact logically often cannot) preserve earlier theories as limiting cases, II. 1 is false. • As scientists do not and should not attempt to preserve them, II. 2 is false.

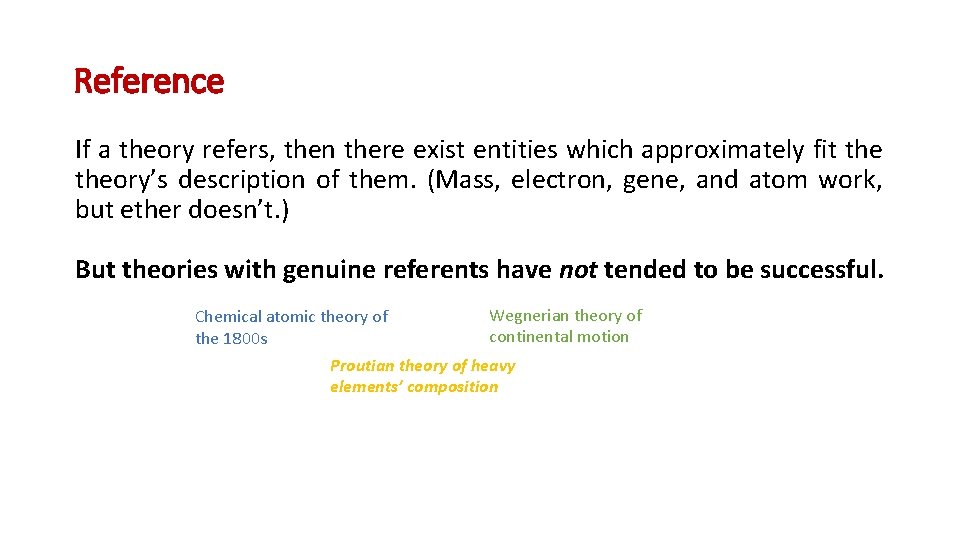

Reference If a theory refers, then there exist entities which approximately fit theory’s description of them. (Mass, electron, gene, and atom work, but ether doesn’t. ) But theories with genuine referents have not tended to be successful. Wegnerian theory of Chemical atomic theory of continental motion the 1800 s Proutian theory of heavy elements’ composition

Nor must they “probably” or “usually” be successful—simply throw a few negation symbols into a correct theory and you can produce an extremely unsuccessful theory that posits the same ontology. It is not enough for theories to make accurate claims about what entities exist. It must also be right about how these entities behave and interact—otherwise it will not enjoy predictive success.

• Even worse, we are now confident many successful past theories did not refer. Ether theories are the primary example of this. Question: instead of weakening the claim of “always” to usually, ” why not weaken “all the central terms refer” to “some of the central terms refer”? A. Testing a theory verifies all or none of it—otherwise, the relationship between success and truth upon which CER’s whole case hinges is false. B. If only some central terms refer, the retentiveness of earlier theories’ terms by later theories doesn’t hold either.

Laudan’s approach • It is credible, or at least not a weak point, to say that scientific theories do succeed. • The claim that reference causes or explains success (I. 2) is false. • The notion of “approximate truth” is unclear; I. 1 is ambiguous. • As later theories do not (and in fact logically often cannot) preserve earlier theories as limiting cases, II. 1 is false. • As scientists do not and should not attempt to preserve them, II. 2 is false.

“Approximate Truth” T is approximately true T is successful at explanation. Whatever “approximately true” means, it cannot include theories that do not refer. (This is Putnam’s “out” from problems with reference. ) But in the history of science, plenty of predictive theories did not refer. What if we apply “successful approximately true” only to theories in the mature sciences?

Laudan’s approach • It is credible, or at least not a weak point, to say that scientific theories do succeed. • The claim that reference causes or explains success (I. 2) is false. • The notion of “approximate truth” is unclear; I. 1 is ambiguous. • As later theories do not (and in fact logically often cannot) preserve earlier theories as limiting cases, II. 1 is false. • As scientists do not and should not attempt to preserve them, II. 2 is false.

“The Retentive Thesis” • C 1: If earlier theories are successful (and approximately true), scientists should only accept later theories which retain appropriate portions of these predecessors. This essentially entails that the earlier theory behaves as a limiting, extremal case of the later one. • C 2: This is in fact what scientists do. • C 3: The effectiveness of this process supports the retentive thesis.

But neither history nor the widely prevailing understanding of theory-language permits these to be true. • No one criticized Lyell or Darwin for failing to incorporate relevant parts of earlier theories. • Diagonal zinger: “One could take a leaf from [C 2] and claim that the success of the strategy of assuming that earlier theories do not generally refer shows that it is true that [they don’t]!” (38).

Earlier theories that do not account for all the successor theory’s referents cannot formally be understood as limiting cases. Such would require: • All the variables assigned a value in T 1 are assigned a value in T 2 • The values assigned to every variable in T 1 are close to those assigned in T 2, assuming certain constants are specified. This is impossible—if there is a change in ontology, T 1 can never be a limiting case of T 2 because of overdetermination.

Earlier theories that do account for all the successor theory’s referents cannot formally be understood as limiting cases either. If T 1, T 2 disagree, each will have true, determinate consequences that are unique. What about the weaker claim that successor theories should explain an earlier theory’s successes? It is pragmatically unnecessary and epistemically unfounded.

Now Laudan has shown that the reference and approximate truth premises from CER I, and both the empirical and theoretical premises from CER II, fail. • The final nail in the coffin for the epistemological realist: even the structure of the two abductive arguments is a priori uncompelling to a non-realist.

Gems • Laudan is extremely comfortable with historiography, and brilliantly weaves together history of science with philosophy of science. • Laudan uses the realist’s own arguments against him, in thoughtprovoking and surprising ways. [C 2, Petitio Principii] • Laudan makes use of high-level technical content—logical relations, theory-language—without getting mired in the formal.

Discussion • Does the onus fall on the realist to defend that non-realists cannot explain scientific success? Or does the “no miracles” argument stand? • Is there an intuitive concept behind the notion of “limiting cases” that Laudan or the epistemological realists are misstating? • What conclusions can we draw from the widespread past success of non-verisimilar, non-referring theories?