A Closer Look at All Pairs Testing Paul

- Slides: 30

A Closer Look at All Pairs Testing Paul C. Jorgensen, Ph. D. Professor, School of Computing and Information Systems Grand Valley State University Allendale, MI 49401 USA jorgensp@gvsu. edu

The Popular Understanding of All Pairs • • • based on Orthogonal Arrays drastically reduces number of test cases a combination of worst case and equivalence class testing strong recommendation from Dorothy Wallace (NIST) well-received in the agile methods community (greatest thing since socks on chickens)

Testimonials “ 98% of the reported software defects in recalled medical devices could have been detected by testing all pairs of parameter settings. ” D. R. Wallace, D. R. Kuhn, “Failure Modes in Medical Device Software: An Analysis of 15 Years of Recall Data, ” Intl. Journal of Reliability, Quality, and Safety Engineering, vol. 8, no. 4. “Pairwise testing is a wildly popular topic…subject of over 40 conference and journal papers” James Bach and Patrick Schroeder in “Pairwise Testing: A Best Practice That Isn’t” STAR (see also Greg Daich in Crosstalk, August 2003)

Summary of the Popular Story (per Bach and Schroeder) • • • “Pairwise testing protects against pairwise bugs “while dramatically reducing the number of tests to perform “which is especially cool because pairwise bugs represent the majority of combinatoric bugs “and such bugs are a lot more likely to happen than the ones that only happen with more variables. “Plus, the availability of tools means you no longer need to create these tests by hand. ”

Preferred Story (per Bach and Schroeder) • • • “Pairwise testing might find some pairwise bugs “while dramatically reducing the number of tests to perform, compared to testing all combinations, but not necessarily compared to testing just the combinations that matter, “which is especially cool because pairwise bugs represent the majority of combinatoric bugs, or might not, depending on the actual dependencies among the variables in the product, “and such bugs are more likely to happen than ones that only happen with more variables, or less likely to happen, because user inputs are not randomly distributed. “Plus, the availability of tools means you no longer need to create these tests by hand, except for the work of analyzing the product, selecting variables and values, actually configuring and performing the test, and analyzing the results. ”

Useful Questions • • Intended level (unit, integration, system)? Assumptions? When does it work? When does it not work?

What Does All Pairs Do? • Input is a set of equivalence classes for each variable. • Sometimes the equivalence classes are those used in Boundary Value testing (min, min+, nominal, max-, max) • Output is a set of (partial) test cases that approximate an orthogonal array, plus some pairing information. • Why partial? No expected outputs are provided. natural enough, but a tester still needs to do this step.

All Pairs Assumptions • Variables have clear equivalence classes. • Variables are independent. • Failures are the result of the interaction of a pair of variable values.

Jorgensen’s First Law of Software Engineering When you multiply a big number by a big number, you get a really big number. Corollary (for probability theory): When you multiply a small number (< 1) by a small number, you get a really small number.

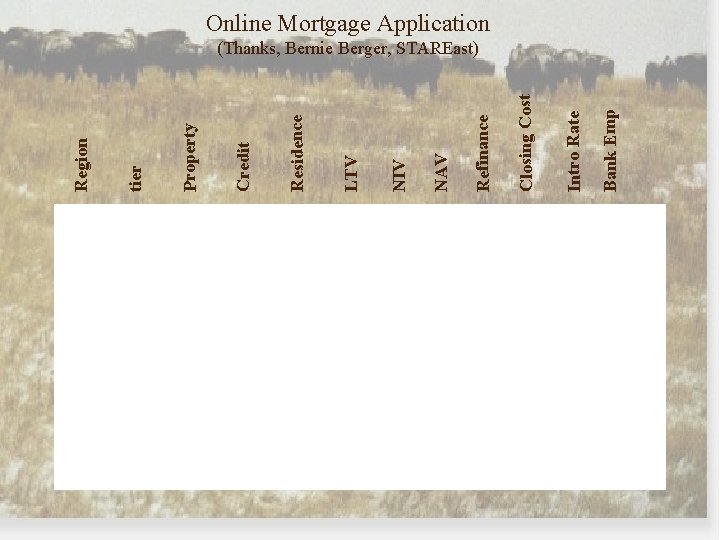

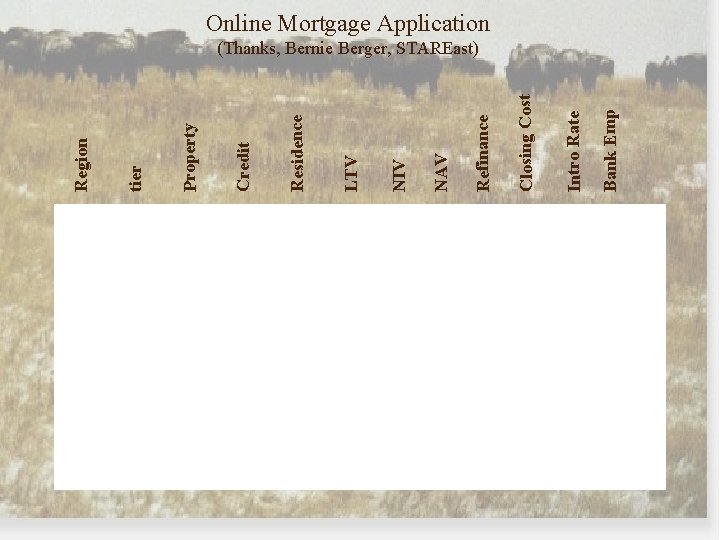

Bank Emp Intro Rate Closing Cost Refinance NAV NIV LTV Residence Credit Property tier Region Online Mortgage Application (Thanks, Bernie Berger, STAREast)

Jorgensen’s Law Applied. . . Twelve variables, with varying numbers of values, have 7 x 6 x 5 x 3 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 725, 760 combinations of values. “All Pairs does it in 50. ” (Bernie Berger, STAREast 2003)

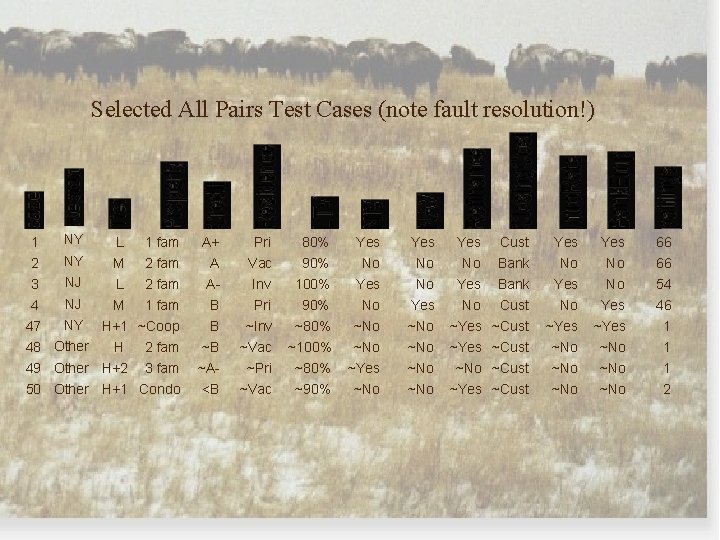

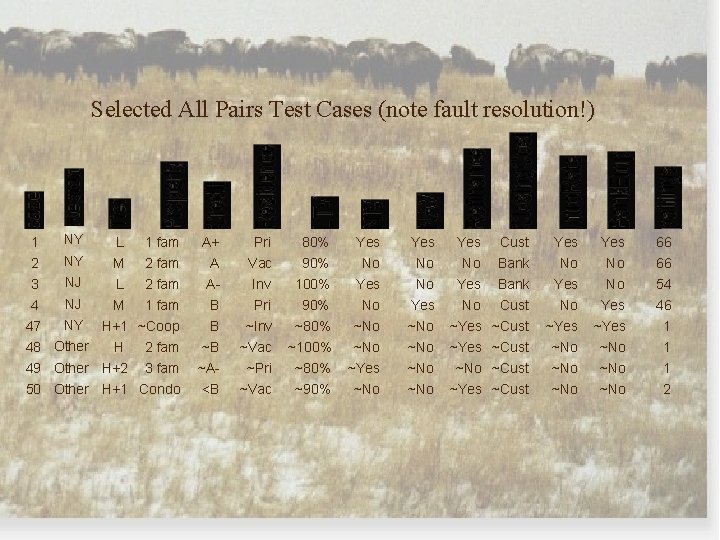

Selected All Pairs Test Cases (note fault resolution!) 1 2 3 NY L 1 fam NY M 2 fam NJ L 2 fam NJ 4 M 1 fam NY H+1 ~Coop 47 48 Other H 2 fam 49 Other H+2 3 fam 50 Other H+1 Condo A+ A AB B ~B ~A<B Pri Vac Inv Pri ~Inv ~Vac 80% 90% 100% Yes No Yes 90% ~80% ~100% No ~No ~Pri ~Vac ~80% ~90% ~Yes ~No Yes No No Yes ~No ~No Yes No ~Yes ~No ~Yes Cust Bank Cust ~Cust Yes No ~Yes ~No ~No Yes No No Yes ~No ~No 66 66 54 46 1 1 1 2

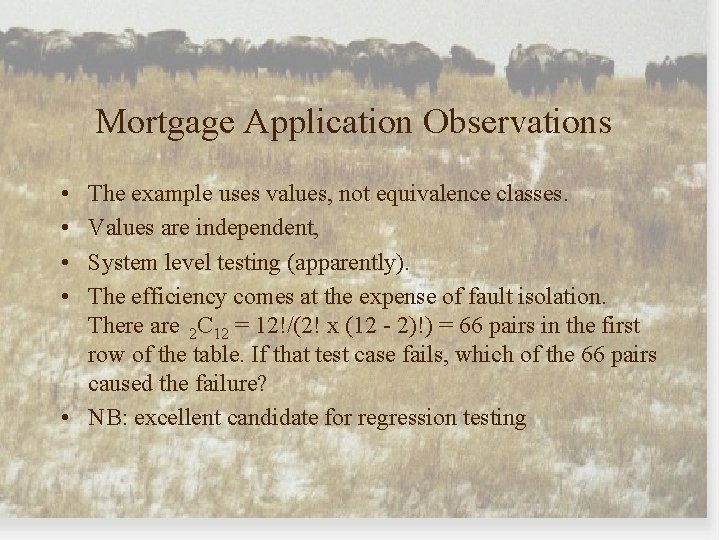

Mortgage Application Observations • • The example uses values, not equivalence classes. Values are independent, System level testing (apparently). The efficiency comes at the expense of fault isolation. There are 2 C 12 = 12!/(2! x (12 - 2)!) = 66 pairs in the first row of the table. If that test case fails, which of the 66 pairs caused the failure? • NB: excellent candidate for regression testing

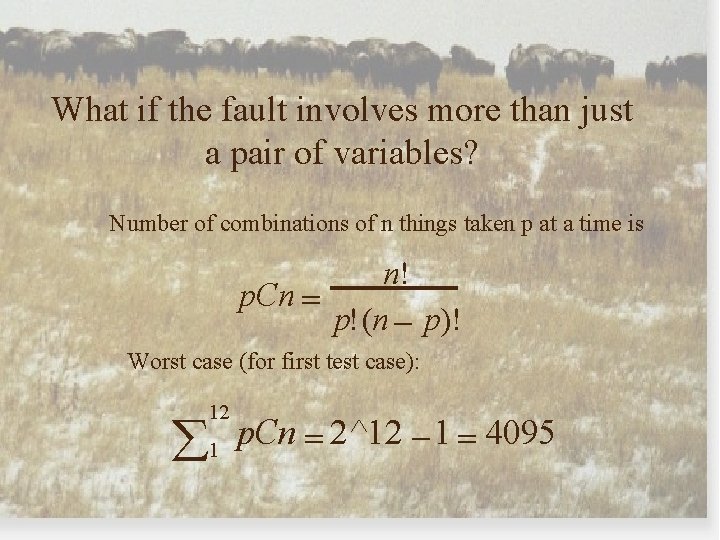

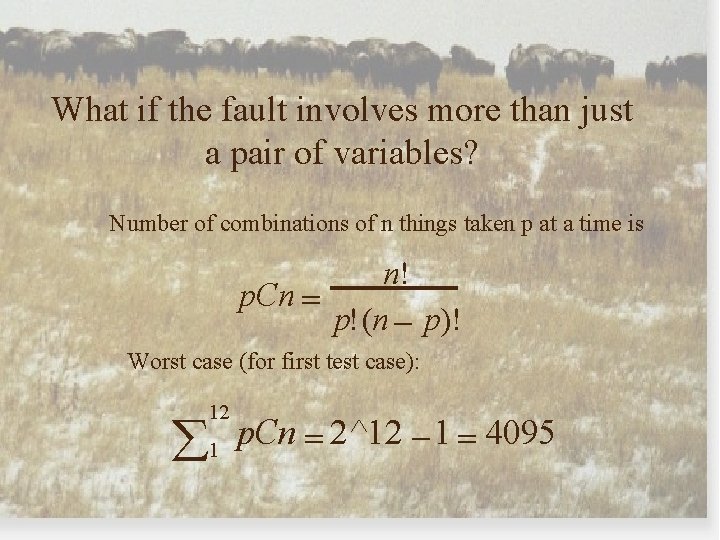

What if the fault involves more than just a pair of variables? Number of combinations of n things taken p at a time is n! p. Cn = p!(n - p)! Worst case (for first test case): 12 å 1 p. Cn = 2^12 - 1 = 4095

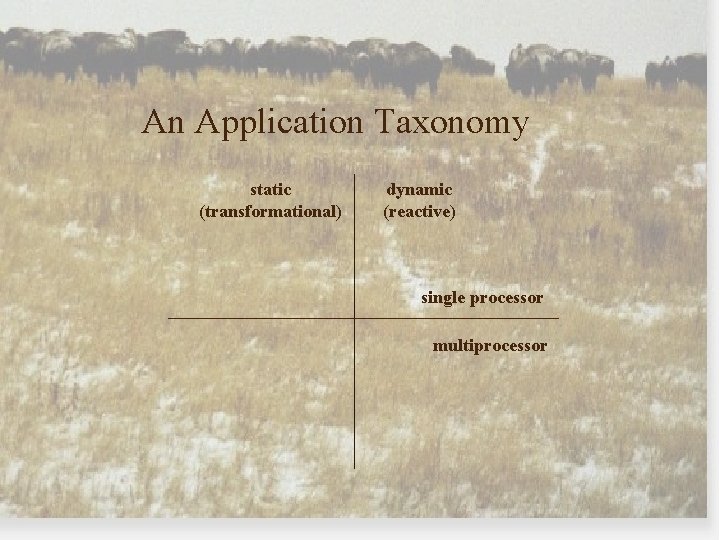

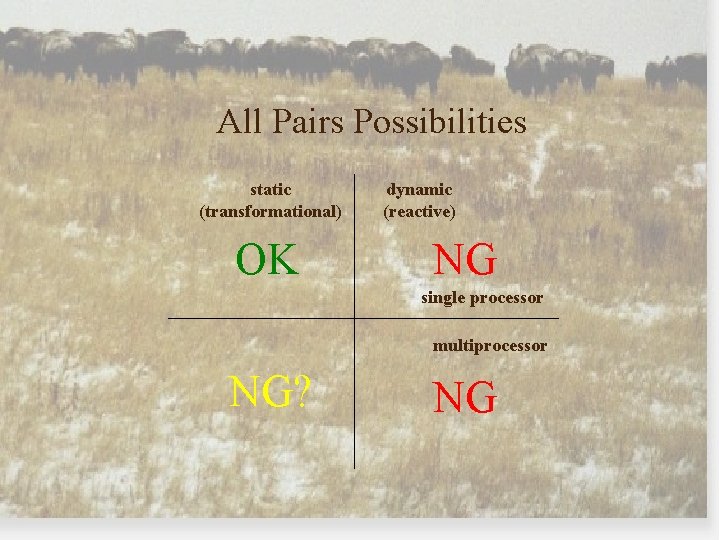

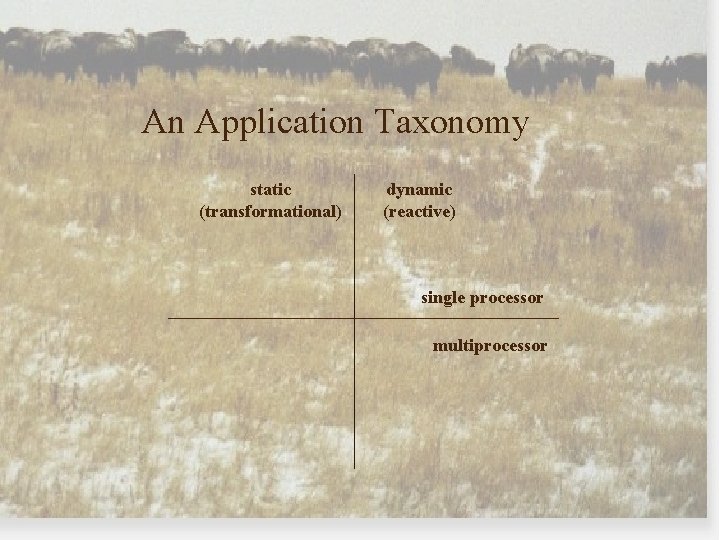

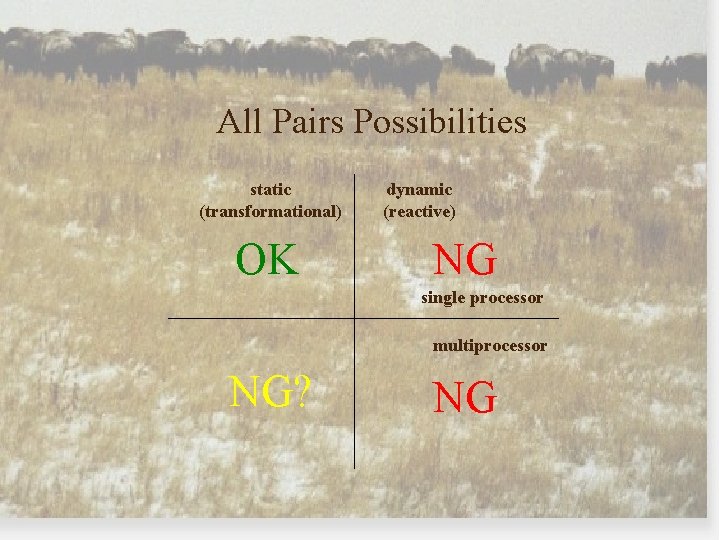

An Application Taxonomy static (transformational) dynamic (reactive) single processor multiprocessor

Static, Single Processor Applications • “Classic COBOL”: Inputs, Processing, Outputs. • David Harel’s “transformational” programs. • All inputs that determine eventual execution track (through code) are available at the onset of the program execution. • Example: a GUI with several inputs and a “Do It” button. • Most published All Pairs examples are in this quadrant.

Dynamic, Single Processor Applications • Event-driven applications, possibly real-time. • David Harel’s “reactive” programs. • Not all inputs that determine eventual execution track (through code) are available at the onset of the program execution. • Context-sensitive input events are common. • Examples: An ATM system, an industrial control system. • All Pairs CANNOT work in this quadrant.

Static, Multi-Processor Applications • Multi-processing used for parallel computation. • All inputs that determine eventual execution track (through code) are available at the onset of the program execution. • Examples: Meteorology applications, partial differential equations, other computationally intensive problems. • Conjecture: All Pairs will probably not work in this quadrant.

Dynamic, Multi-Processor Applications • • Asynchronous, parallel, event-driven applications. David Harel’s “reactive” programs. (nicely modeled with communicating finite state machines). Not all inputs that determine eventual execution track (through code) are available at the onset of the program execution. • Examples: a telephone call. • All Pairs CANNOT work in this quadrant.

All Pairs Possibilities static (transformational) OK dynamic (reactive) NG single processor multiprocessor NG? NG

Next. Date with All Pairs • • Next. Date is a function of three variables (day, month, year) Next. Date(3, 2, 2006) = (4, 2, 2006) A Static, Single-Processor application Illustrates several difficulties with All Pairs

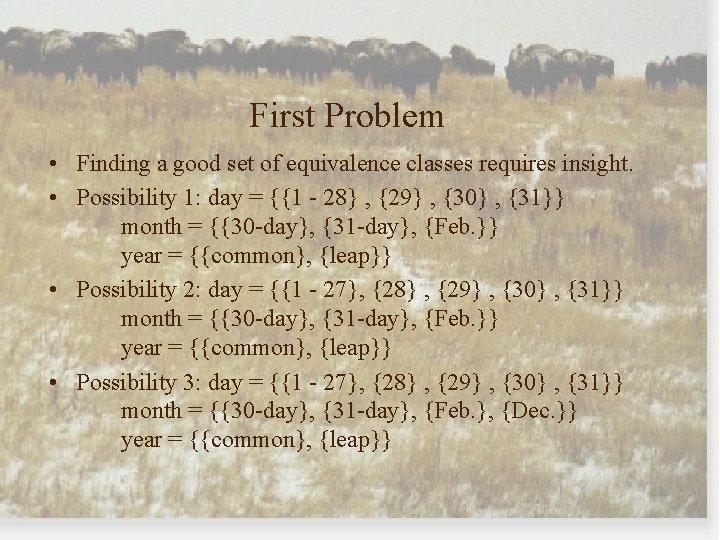

First Problem • Finding a good set of equivalence classes requires insight. • Possibility 1: day = {{1 - 28} , {29} , {30} , {31}} month = {{30 -day}, {31 -day}, {Feb. }} year = {{common}, {leap}} • Possibility 2: day = {{1 - 27}, {28} , {29} , {30} , {31}} month = {{30 -day}, {31 -day}, {Feb. }} year = {{common}, {leap}} • Possibility 3: day = {{1 - 27}, {28} , {29} , {30} , {31}} month = {{30 -day}, {31 -day}, {Feb. }, {Dec. }} year = {{common}, {leap}}

First Problem (continued) Possibility 3 is the best, BUT the equivalence classes are not independent. As a rule, all “multiplicative operations”, e. g. Cartesian products and probability conjunctions, presume independence. When the assumption is not justified, the result is almost always an impossible situation.

Second Problem • All Pairs cannot deal with dependent input variables (values or equivalence classes). • Dependencies result in impossible dates. • Easy to recognize in Next. Date, because we are EXPERTS. • Much harder to recognize in less-well understood problems.

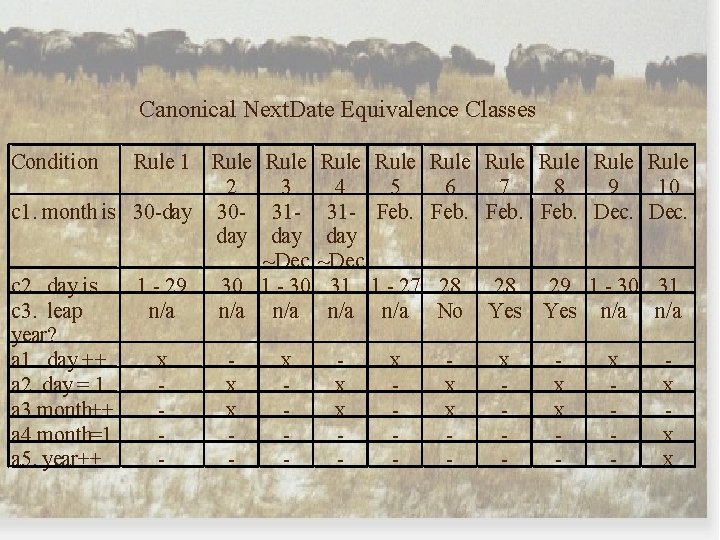

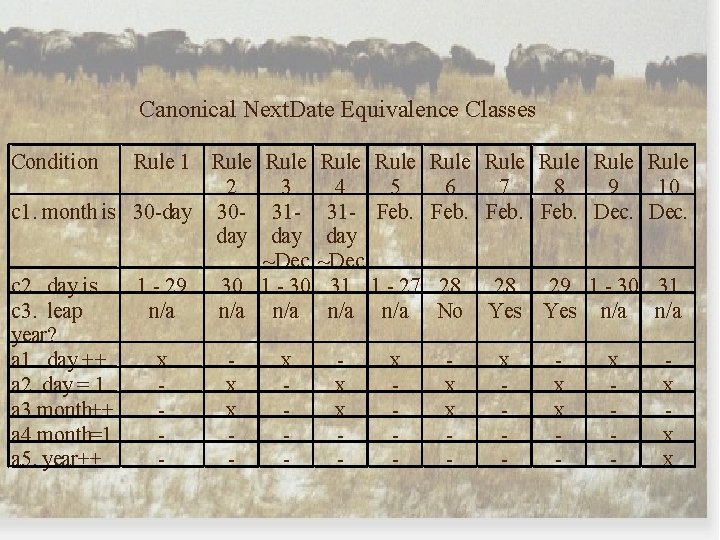

Canonical Next. Date Equivalence Classes Condition Rule 1 Rule 2 3 4 5 c 1. month is 30 -day 30 - 31 - Feb. day day ~Dec c 2. day is 1 - 29 30 1 - 30 31 1 - 27 c 3. leap n/a n/a n/a year? a 1. day ++ x x x a 2. day = 1 x x a 3. month++ x x a 4. month=1 a 5. year++ - Rule Rule 6 7 8 9 10 Feb. Dec. 28 No x x - 28 29 1 - 30 31 Yes n/a x - x - x x x

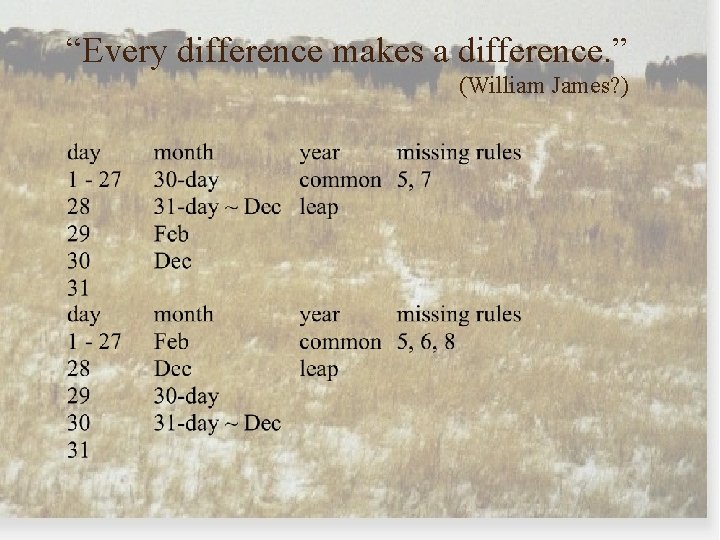

All Pairs Test Cases for Next. Date

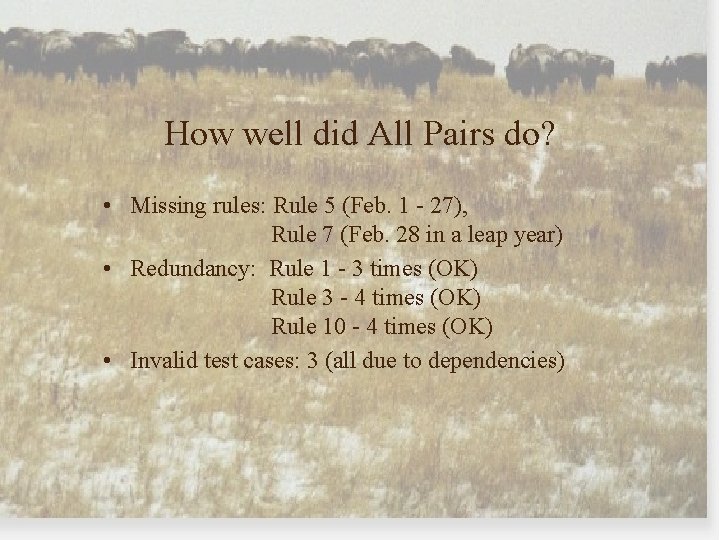

How well did All Pairs do? • Missing rules: Rule 5 (Feb. 1 - 27), Rule 7 (Feb. 28 in a leap year) • Redundancy: Rule 1 - 3 times (OK) Rule 3 - 4 times (OK) Rule 10 - 4 times (OK) • Invalid test cases: 3 (all due to dependencies)

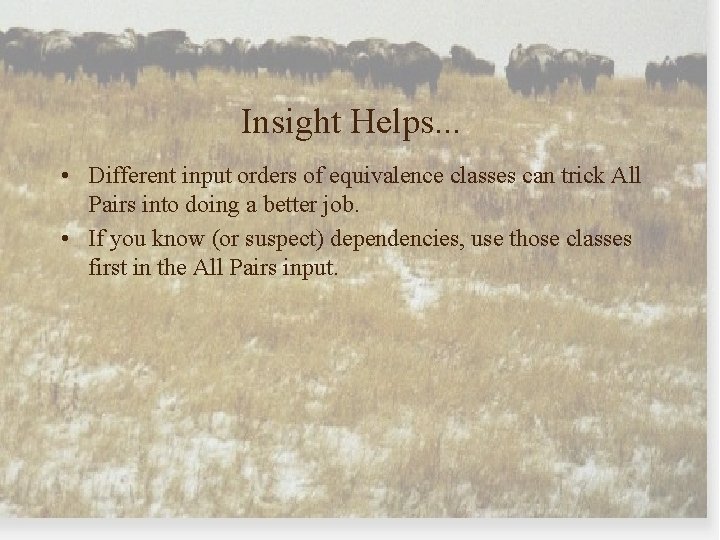

Insight Helps. . . • Different input orders of equivalence classes can trick All Pairs into doing a better job. • If you know (or suspect) dependencies, use those classes first in the All Pairs input.

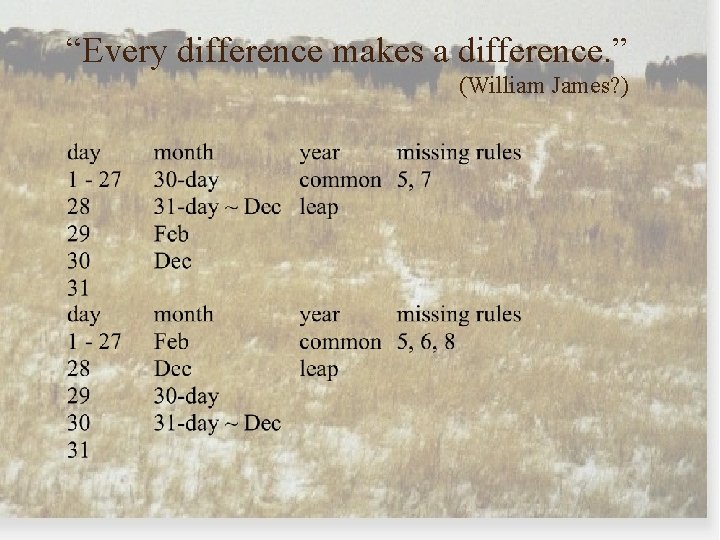

“Every difference makes a difference. ” (William James? )

My Conclusions (so far). . . • As with so many things in life (and software testing), you only get out of it what you put into it. • The hype outweighs the substance. • All Pairs is just another shortcut. • Must recognize the assumptions. • Only works for simple (i. e. static sequential) applications. • Could be used for integration or system testing. • Best use? Regression testing.