A brief Introduction to Automated Theorem Proving Theoretical

A brief Introduction to Automated Theorem Proving Theoretical Foundations, History and the Resolution Calculus for classical First-order Logic Uwe Keller based on material by B. Beckert, R. Hähnle, A. Voronkov, A. Leitsch and T. Tammet

Content o o o Intoduction n Motivation & History n Theorem Proving, ATP and Calculi Foundations n FOL, Normalforms & Preprocessing, Metaresults Resolution n Basic calculus, Unification n Refinements, Redundancy n Decision procedures Chain Resolution n A Variant of Resolution for the Semantic Web Demo

Part I: Introduction n n Motivation & History Theorem Proving, ATP and Calculi

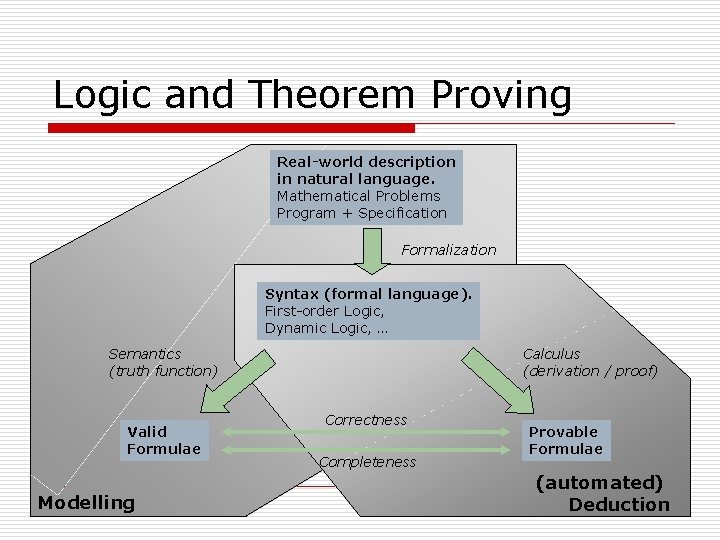

Logic and Theorem Proving Real-world description in natural language. Mathematical Problems Program + Specification Formalization Syntax (formal language). First-order Logic, Dynamic Logic, … Semantics (truth function) Valid Formulae Modelling Calculus (derivation / proof) Correctness Completeness Provable Formulae (automated) Deduction

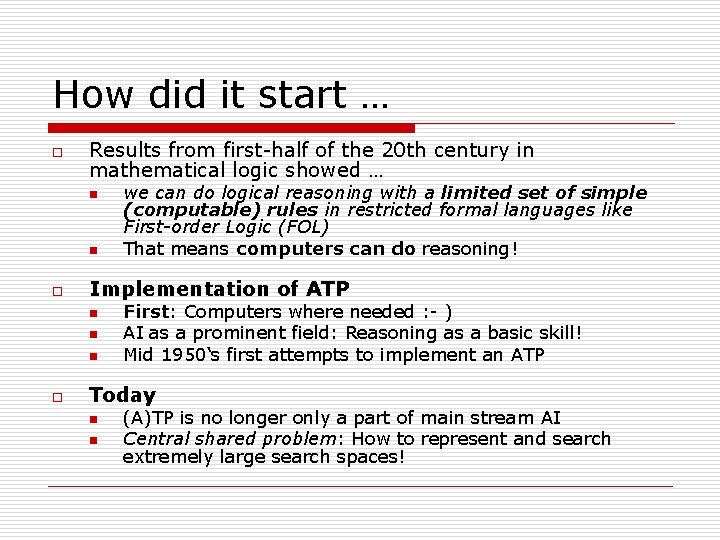

How did it start … o Results from first-half of the 20 th century in mathematical logic showed … n n o Implementation of ATP n n n o we can do logical reasoning with a limited set of simple (computable) rules in restricted formal languages like First-order Logic (FOL) That means computers can do reasoning! First: Computers where needed : - ) AI as a prominent field: Reasoning as a basic skill! Mid 1950‘s first attempts to implement an ATP Today n n (A)TP is no longer only a part of main stream AI Central shared problem: How to represent and search extremely large search spaces!

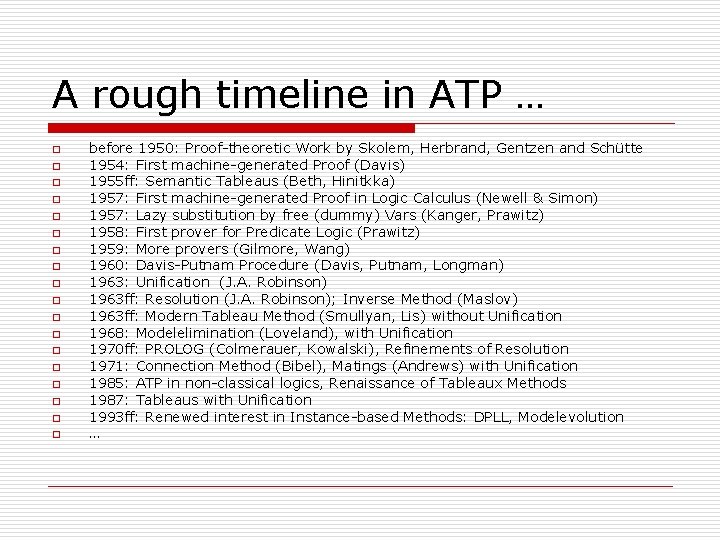

A rough timeline in ATP … o o o o o before 1950: Proof-theoretic Work by Skolem, Herbrand, Gentzen and Schütte 1954: First machine-generated Proof (Davis) 1955 ff: Semantic Tableaus (Beth, Hinitkka) 1957: First machine-generated Proof in Logic Calculus (Newell & Simon) 1957: Lazy substitution by free (dummy) Vars (Kanger, Prawitz) 1958: First prover for Predicate Logic (Prawitz) 1959: More provers (Gilmore, Wang) 1960: Davis-Putnam Procedure (Davis, Putnam, Longman) 1963: Unification (J. A. Robinson) 1963 ff: Resolution (J. A. Robinson); Inverse Method (Maslov) 1963 ff: Modern Tableau Method (Smullyan, Lis) without Unification 1968: Modelelimination (Loveland), with Unification 1970 ff: PROLOG (Colmerauer, Kowalski), Refinements of Resolution 1971: Connection Method (Bibel), Matings (Andrews) with Unification 1985: ATP in non-classical logics, Renaissance of Tableaux Methods 1987: Tableaus with Unification 1993 ff: Renewed interest in Instance-based Methods: DPLL, Modelevolution …

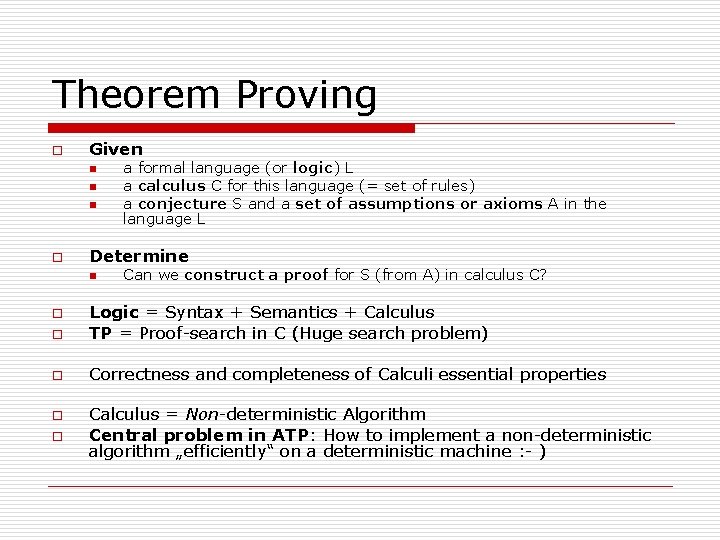

Theorem Proving o Given n o a formal language (or logic) L a calculus C for this language (= set of rules) a conjecture S and a set of assumptions or axioms A in the language L Determine n Can we construct a proof for S (from A) in calculus C? o Logic = Syntax + Semantics + Calculus TP = Proof-search in C (Huge search problem) o Correctness and completeness of Calculi essential properties o o o Calculus = Non-deterministic Algorithm Central problem in ATP: How to implement a non-deterministic algorithm „efficiently“ on a deterministic machine : - )

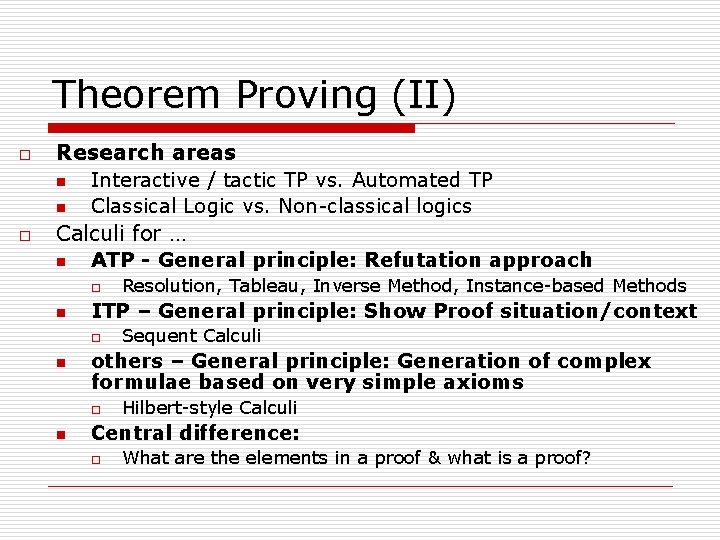

Theorem Proving (II) o o Research areas n Interactive / tactic TP vs. Automated TP n Classical Logic vs. Non-classical logics Calculi for … n ATP - General principle: Refutation approach o n ITP – General principle: Show Proof situation/context o n Sequent Calculi others – General principle: Generation of complex formulae based on very simple axioms o n Resolution, Tableau, Inverse Method, Instance-based Methods Hilbert-style Calculi Central difference: o What are the elements in a proof & what is a proof?

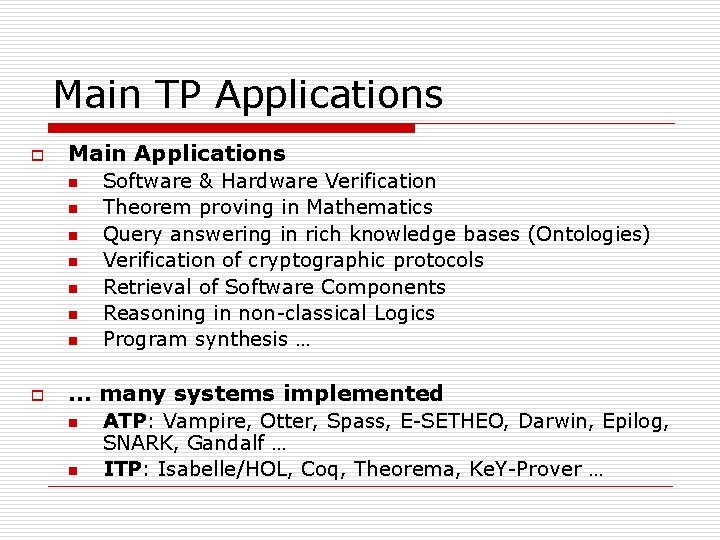

Main TP Applications o Main Applications n n n n o Software & Hardware Verification Theorem proving in Mathematics Query answering in rich knowledge bases (Ontologies) Verification of cryptographic protocols Retrieval of Software Components Reasoning in non-classical Logics Program synthesis … … many systems implemented n n ATP: Vampire, Otter, Spass, E-SETHEO, Darwin, Epilog, SNARK, Gandalf … ITP: Isabelle/HOL, Coq, Theorema, Ke. Y-Prover …

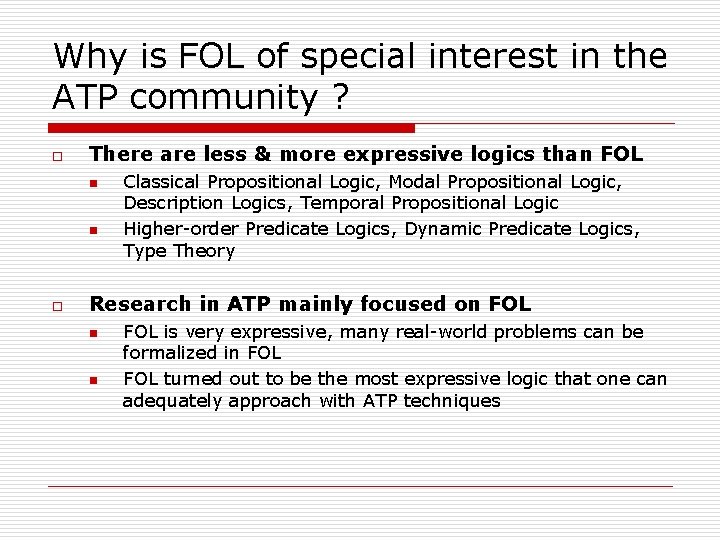

Why is FOL of special interest in the ATP community ? o There are less & more expressive logics than FOL n n o Classical Propositional Logic, Modal Propositional Logic, Description Logics, Temporal Propositional Logic Higher-order Predicate Logics, Dynamic Predicate Logics, Type Theory Research in ATP mainly focused on FOL n n FOL is very expressive, many real-world problems can be formalized in FOL turned out to be the most expressive logic that one can adequately approach with ATP techniques

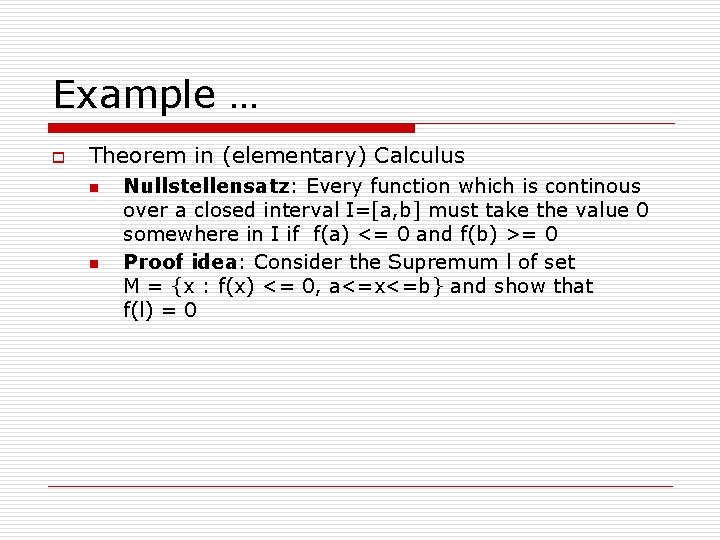

Example … o Theorem in (elementary) Calculus n n Nullstellensatz: Every function which is continous over a closed interval I=[a, b] must take the value 0 somewhere in I if f(a) <= 0 and f(b) >= 0 Proof idea: Consider the Supremum l of set M = {x : f(x) <= 0, a<=x<=b} and show that f(l) = 0

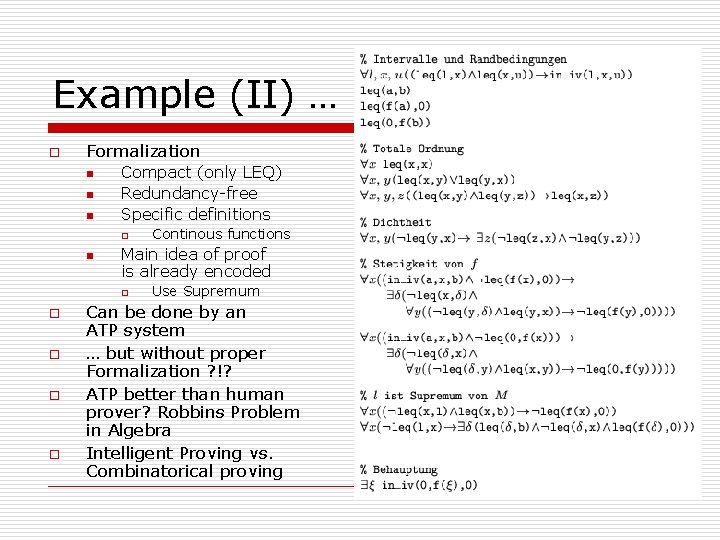

Example (II) … o Formalization n Compact (only LEQ) Redundancy-free Specific definitions o n Main idea of proof is already encoded o o o Continous functions Use Supremum Can be done by an ATP system … but without proper Formalization ? !? ATP better than human prover? Robbins Problem in Algebra Intelligent Proving vs. Combinatorical proving

Part II: Foundations FOL, Normalforms & Preprocessing, Metaresults n

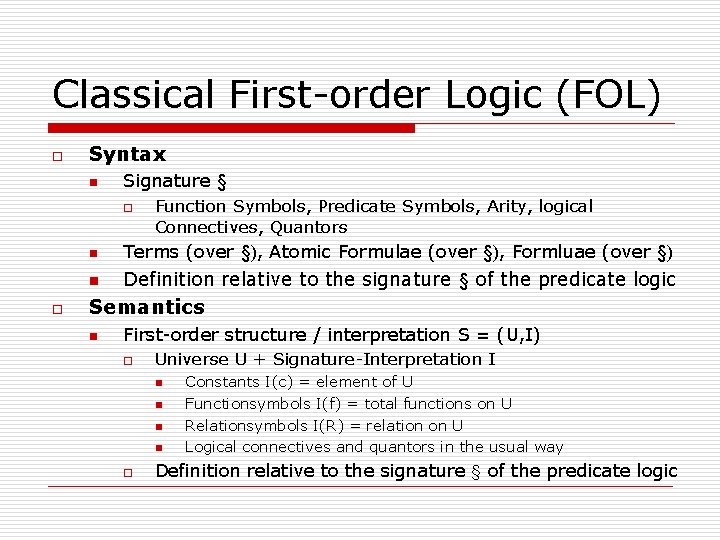

Classical First-order Logic (FOL) o Syntax n Signature § o o Function Symbols, Predicate Symbols, Arity, logical Connectives, Quantors n Terms (over §), Atomic Formulae (over §), Formluae (over §) n Definition relative to the signature § of the predicate logic Semantics n First-order structure / interpretation S = (U, I) o Universe U + Signature-Interpretation I n n o Constants I(c) = element of U Functionsymbols I(f) = total functions on U Relationsymbols I(R) = relation on U Logical connectives and quantors in the usual way Definition relative to the signature § of the predicate logic

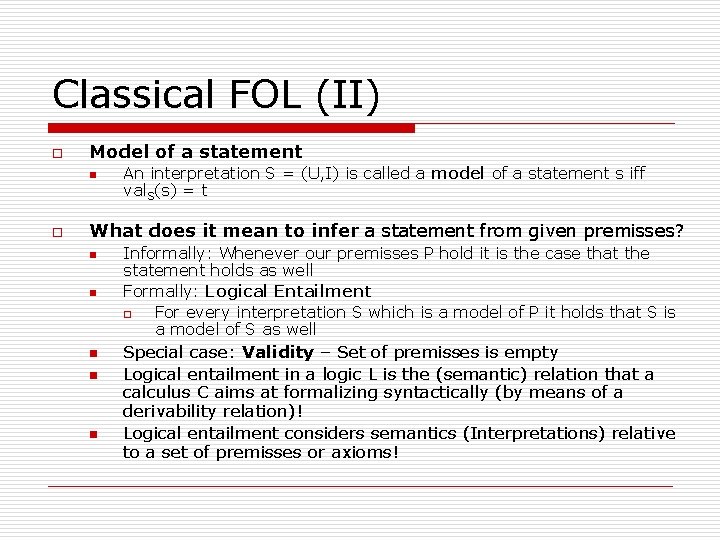

Classical FOL (II) o Model of a statement n o An interpretation S = (U, I) is called a model of a statement s iff val. S(s) = t What does it mean to infer a statement from given premisses? n n n Informally: Whenever our premisses P hold it is the case that the statement holds as well Formally: Logical Entailment o For every interpretation S which is a model of P it holds that S is a model of S as well Special case: Validity – Set of premisses is empty Logical entailment in a logic L is the (semantic) relation that a calculus C aims at formalizing syntactically (by means of a derivability relation)! Logical entailment considers semantics (Interpretations) relative to a set of premisses or axioms!

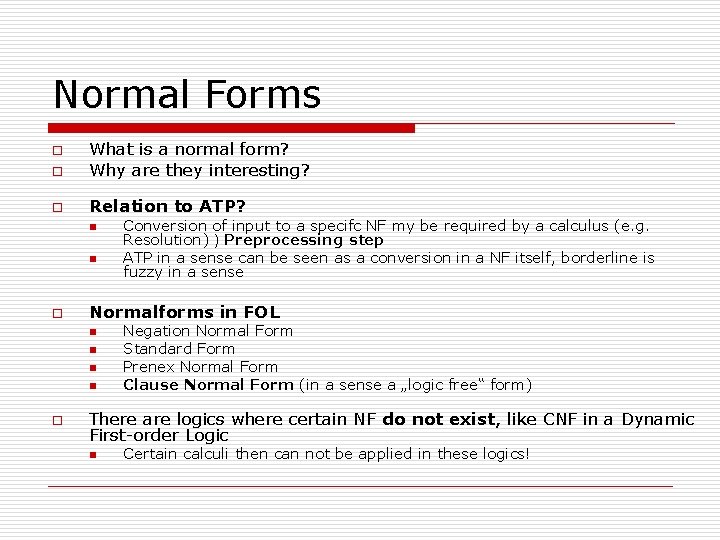

Normal Forms o What is a normal form? Why are they interesting? o Relation to ATP? o n n o Normalforms in FOL n n o Conversion of input to a specifc NF my be required by a calculus (e. g. Resolution) ) Preprocessing step ATP in a sense can be seen as a conversion in a NF itself, borderline is fuzzy in a sense Negation Normal Form Standard Form Prenex Normal Form Clause Normal Form (in a sense a „logic free“ form) There are logics where certain NF do not exist, like CNF in a Dynamic First-order Logic n Certain calculi then can not be applied in these logics!

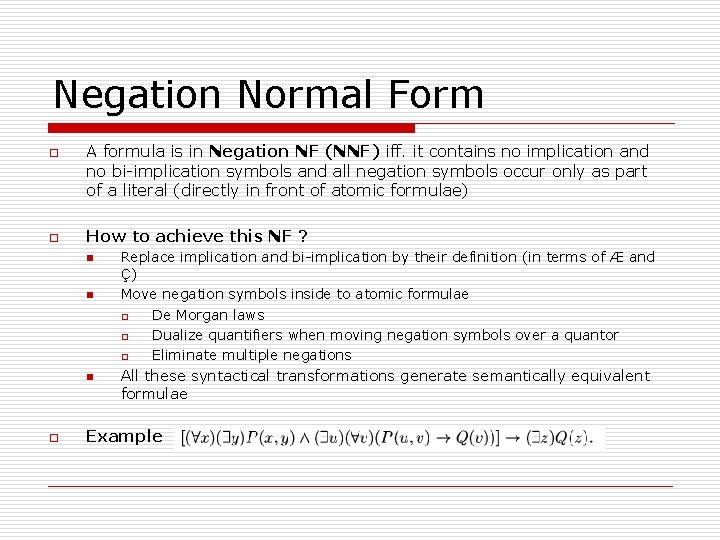

Negation Normal Form o o A formula is in Negation NF (NNF) iff. it contains no implication and no bi-implication symbols and all negation symbols occur only as part of a literal (directly in front of atomic formulae) How to achieve this NF ? n n n o Replace implication and bi-implication by their definition (in terms of Æ and Ç) Move negation symbols inside to atomic formulae o De Morgan laws o Dualize quantifiers when moving negation symbols over a quantor o Eliminate multiple negations All these syntactical transformations generate semantically equivalent formulae Example

Standard Form o o A formula A is in Standard Form if no variable x in A occurs both bound and free and no bound variable is used as a quantor variable for multiple subformulae How to generate this NF? n n o Bounded renaming of quantor variables and the respective occurrences Transformed formulae is semantically equivalent to original one Example (8 x P(x) Æ Q(z)) ! (9 x R(x) Ç 9 z (P(z) Æ Q(z)))

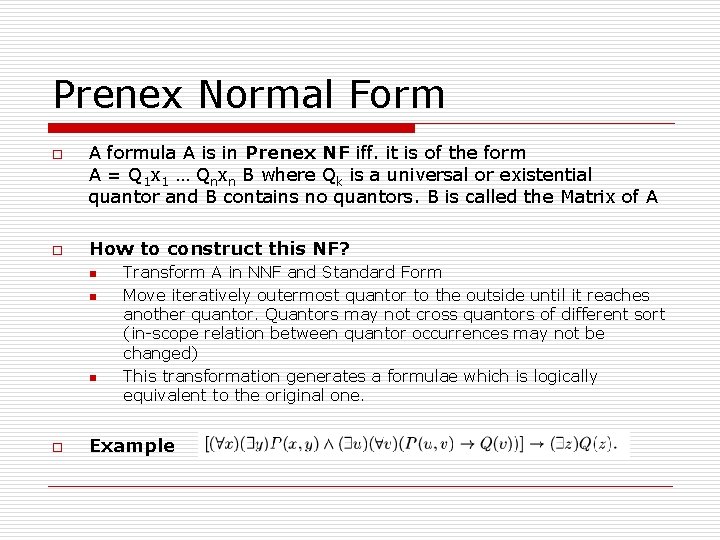

Prenex Normal Form o o A formula A is in Prenex NF iff. it is of the form A = Q 1 x 1 … Qnxn B where Qk is a universal or existential quantor and B contains no quantors. B is called the Matrix of A How to construct this NF? n n n o Transform A in NNF and Standard Form Move iteratively outermost quantor to the outside until it reaches another quantor. Quantors may not cross quantors of different sort (in-scope relation between quantor occurrences may not be changed) This transformation generates a formulae which is logically equivalent to the original one. Example

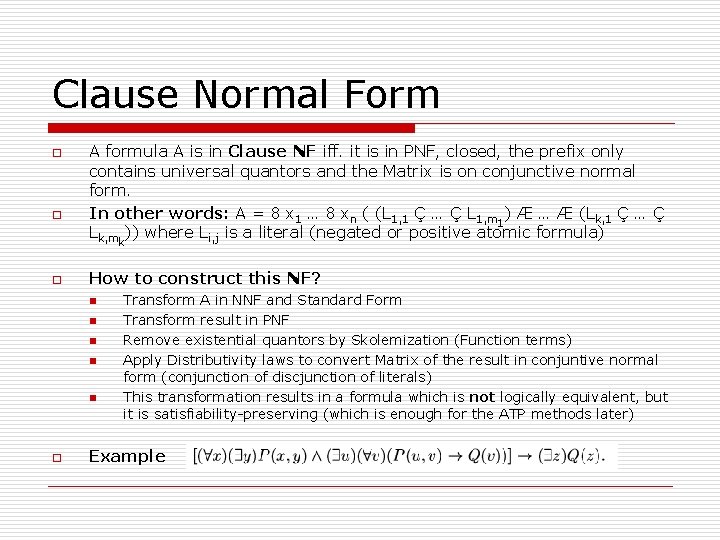

Clause Normal Form o o o A formula A is in Clause NF iff. it is in PNF, closed, the prefix only contains universal quantors and the Matrix is on conjunctive normal form. In other words: A = 8 x 1 … 8 xn ( (L 1, 1 Ç … Ç L 1, m 1) Æ … Æ (Lk, 1 Ç … Ç Lk, mk)) where Li, j is a literal (negated or positive atomic formula) How to construct this NF? n n n o Transform A in NNF and Standard Form Transform result in PNF Remove existential quantors by Skolemization (Function terms) Apply Distributivity laws to convert Matrix of the result in conjuntive normal form (conjunction of discjunction of literals) This transformation results in a formula which is not logically equivalent, but it is satisfiability-preserving (which is enough for the ATP methods later) Example

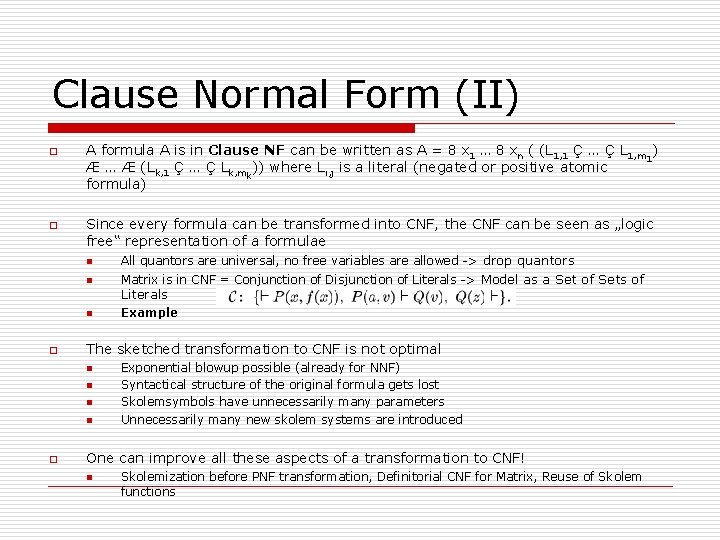

Clause Normal Form (II) o o A formula A is in Clause NF can be written as A = 8 x 1 … 8 xn ( (L 1, 1 Ç … Ç L 1, m ) 1 Æ … Æ (Lk, 1 Ç … Ç Lk, mk)) where Li, j is a literal (negated or positive atomic formula) Since every formula can be transformed into CNF, the CNF can be seen as „logic free“ representation of a formulae n All quantors are universal, no free variables are allowed -> drop quantors n Matrix is in CNF = Conjunction of Disjunction of Literals -> Model as a Set of Sets of Literals n o The sketched transformation to CNF is not optimal n n o Example Exponential blowup possible (already for NNF) Syntactical structure of the original formula gets lost Skolemsymbols have unnecessarily many parameters Unnecessarily many new skolem systems are introduced One can improve all these aspects of a transformation to CNF! n Skolemization before PNF transformation, Definitorial CNF for Matrix, Reuse of Skolem functions

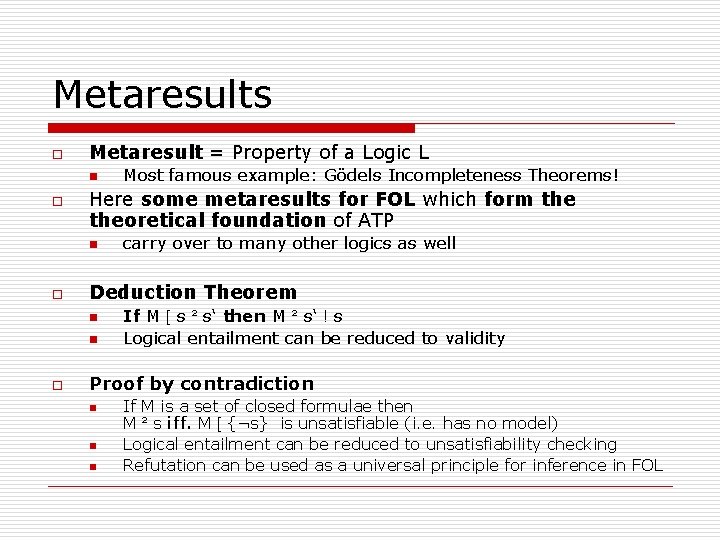

Metaresults o Metaresult = Property of a Logic L n o Here some metaresults for FOL which form theoretical foundation of ATP n o carry over to many other logics as well Deduction Theorem n n o Most famous example: Gödels Incompleteness Theorems! If M [ s ² s‘ then M ² s‘ ! s Logical entailment can be reduced to validity Proof by contradiction n If M is a set of closed formulae then M ² s iff. M [ {¬s} is unsatisfiable (i. e. has no model) Logical entailment can be reduced to unsatisfiability checking Refutation can be used as a universal principle for inference in FOL

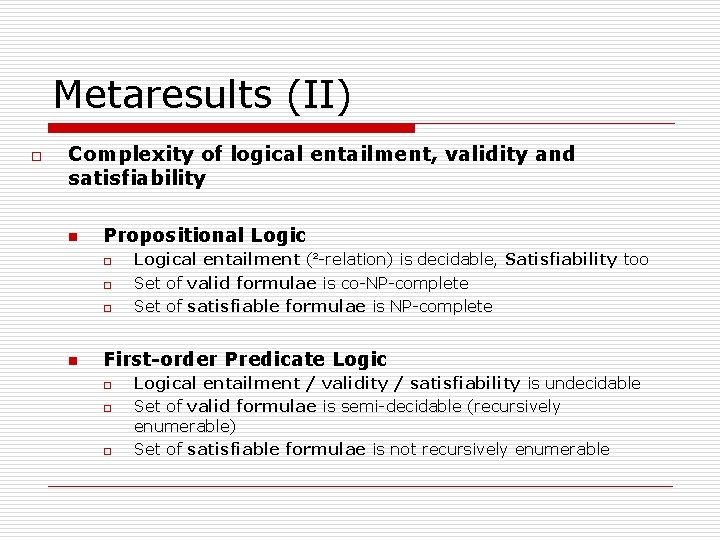

Metaresults (II) o Complexity of logical entailment, validity and satisfiability n Propositional Logic o o o n Logical entailment (²-relation) is decidable, Satisfiability too Set of valid formulae is co-NP-complete Set of satisfiable formulae is NP-complete First-order Predicate Logic o o o Logical entailment / validity / satisfiability is undecidable Set of valid formulae is semi-decidable (recursively enumerable) Set of satisfiable formulae is not recursively enumerable

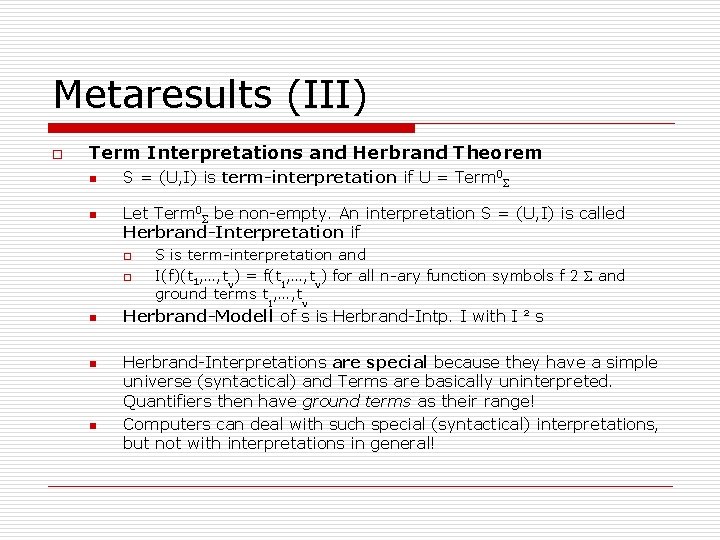

Metaresults (III) o Term Interpretations and Herbrand Theorem n n S = (U, I) is term-interpretation if U = Term 0 Let Term 0 be non-empty. An interpretation S = (U, I) is called Herbrand-Interpretation if o o n n n S is term-interpretation and I(f)(t 1, …, tn) = f(t 1, …, tn) for all n-ary function symbols f 2 and ground terms t 1, …, tn Herbrand-Modell of s is Herbrand-Intp. I with I ² s Herbrand-Interpretations are special because they have a simple universe (syntactical) and Terms are basically uninterpreted. Quantifiers then have ground terms as their range! Computers can deal with such special (syntactical) interpretations, but not with interpretations in general!

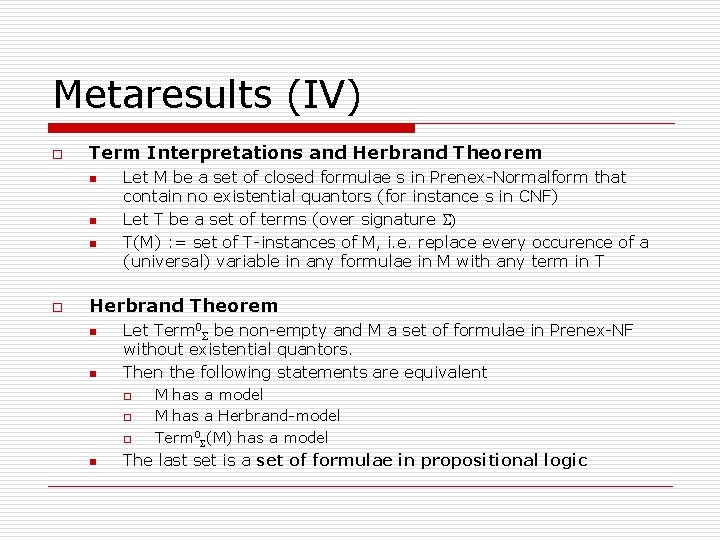

Metaresults (IV) o Term Interpretations and Herbrand Theorem n n n o Let M be a set of closed formulae s in Prenex-Normalform that contain no existential quantors (for instance s in CNF) Let T be a set of terms (over signature ) T(M) : = set of T-instances of M, i. e. replace every occurence of a (universal) variable in any formulae in M with any term in T Herbrand Theorem n n Let Term 0 be non-empty and M a set of formulae in Prenex-NF without existential quantors. Then the following statements are equivalent o o o n M has a model M has a Herbrand-model Term 0 (M) has a model The last set is a set of formulae in propositional logic

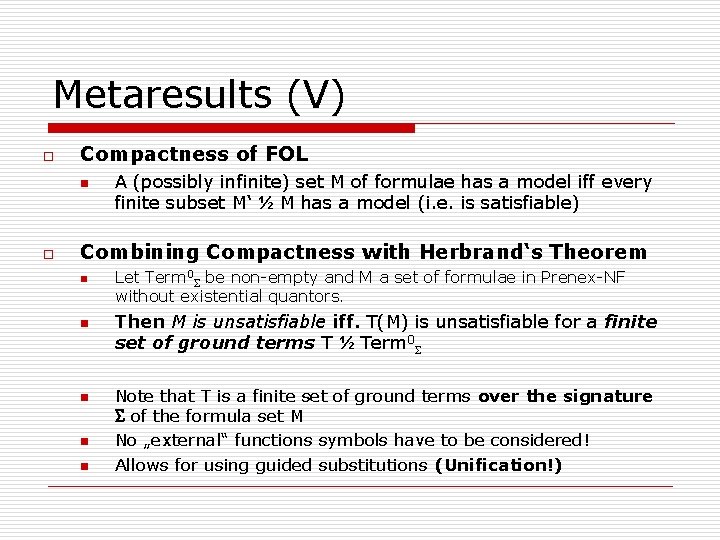

Metaresults (V) o Compactness of FOL n o A (possibly infinite) set M of formulae has a model iff every finite subset M‘ ½ M has a model (i. e. is satisfiable) Combining Compactness with Herbrand‘s Theorem n n n Let Term 0 be non-empty and M a set of formulae in Prenex-NF without existential quantors. Then M is unsatisfiable iff. T(M) is unsatisfiable for a finite set of ground terms T ½ Term 0 Note that T is a finite set of ground terms over the signature of the formula set M No „external“ functions symbols have to be considered! Allows for using guided substitutions (Unification!)

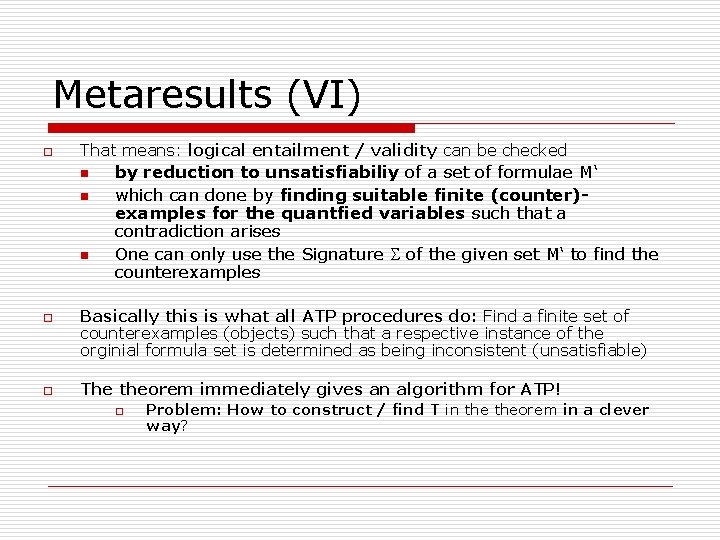

Metaresults (VI) o That means: logical entailment / validity can be checked n n n o o by reduction to unsatisfiabiliy of a set of formulae M‘ which can done by finding suitable finite (counter)examples for the quantfied variables such that a contradiction arises One can only use the Signature of the given set M‘ to find the counterexamples Basically this is what all ATP procedures do: Find a finite set of counterexamples (objects) such that a respective instance of the orginial formula set is determined as being inconsistent (unsatisfiable) The theorem immediately gives an algorithm for ATP! o Problem: How to construct / find T in theorem in a clever way?

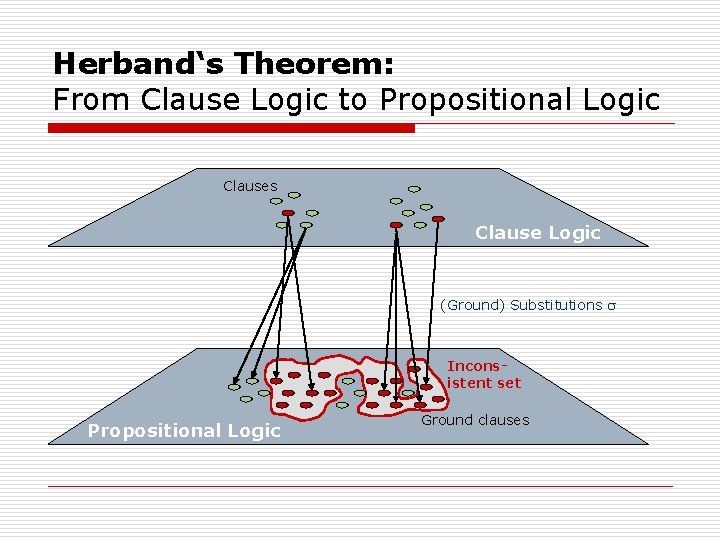

Herband‘s Theorem: From Clause Logic to Propositional Logic Clauses Clause Logic (Ground) Substitutions Inconsistent set Propositional Logic Ground clauses

Part III: The Resolution Calculus n Pre-resolution phase: o n n n Gilmore‘s Methods, Davis-Putnam Procedure Unification Basic Resolution Calculus Refinements, Redundancy

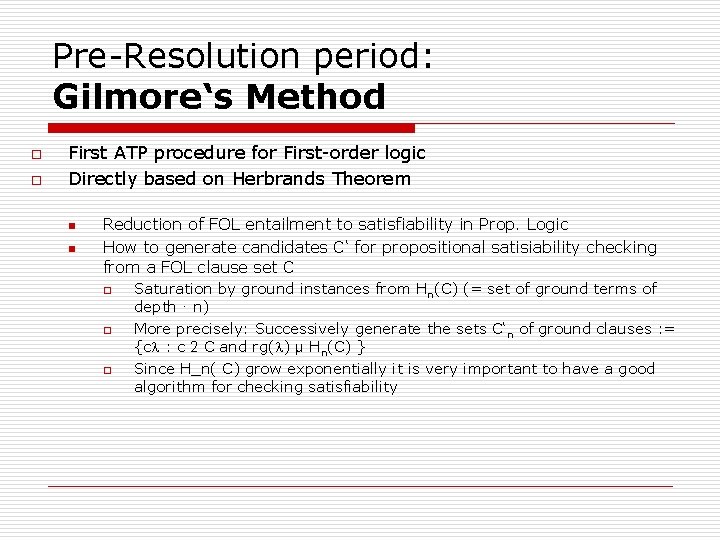

Pre-Resolution period: Gilmore‘s Method o o First ATP procedure for First-order logic Directly based on Herbrands Theorem n n Reduction of FOL entailment to satisfiability in Prop. Logic How to generate candidates C‘ for propositional satisiability checking from a FOL clause set C o o o Saturation by ground instances from Hn(C) (= set of ground terms of depth · n) More precisely: Successively generate the sets C‘ n of ground clauses : = {c : c 2 C and rg( ) µ Hn(C) } Since H_n( C) grow exponentially it is very important to have a good algorithm for checking satisfiability

Pre-Resolution period: Gilmore‘s Method o „Easy“ test of satisfiability of the generated C‘ set of ground clauses: n n o Transform C‘ into Disjunctive Normal Form D = DNF(C‘) is unsatisfiable iff every consitutent of D contains a contradiction L Æ ¬L for some literal L Can be done in deterministic time O(n log(n)) Problem: Convertion from CNF into DNF (almost always) exponential (inherently complex, since otherwise P = NP), (not known at that time!) Pseudocode begin contr : = false while not contr do D‘ : = DNF(C‘_n) contr : = all constitutents of D‘ contain complementary literals n: =n+1 end while end

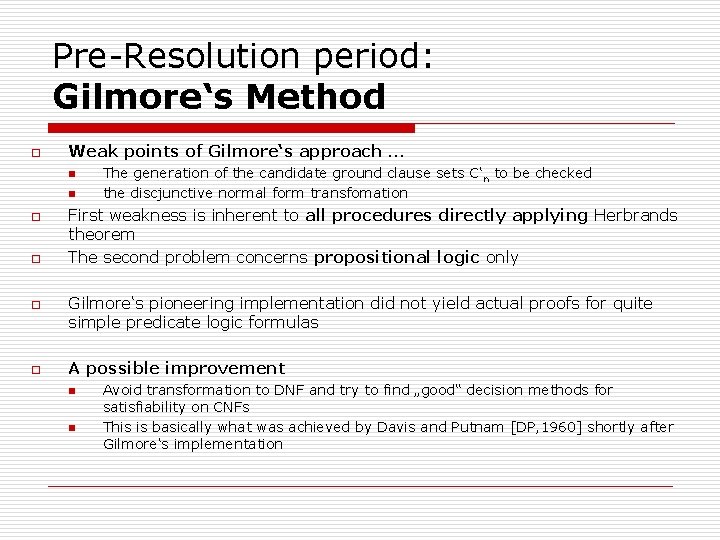

Pre-Resolution period: Gilmore‘s Method o Weak points of Gilmore‘s approach … n n o o The generation of the candidate ground clause sets C‘ n to be checked the discjunctive normal form transfomation First weakness is inherent to all procedures directly applying Herbrands theorem The second problem concerns propositional logic only Gilmore‘s pioneering implementation did not yield actual proofs for quite simple predicate logic formulas A possible improvement n n Avoid transformation to DNF and try to find „good“ decision methods for satisfiability on CNFs This is basically what was achieved by Davis and Putnam [DP, 1960] shortly after Gilmore‘s implementation

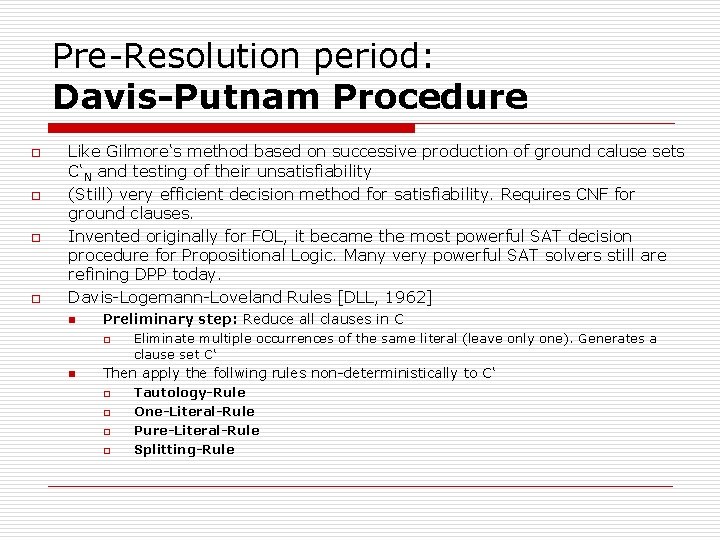

Pre-Resolution period: Davis-Putnam Procedure o o Like Gilmore‘s method based on successive production of ground caluse sets C‘N and testing of their unsatisfiability (Still) very efficient decision method for satisfiability. Requires CNF for ground clauses. Invented originally for FOL, it became the most powerful SAT decision procedure for Propositional Logic. Many very powerful SAT solvers still are refining DPP today. Davis-Logemann-Loveland Rules [DLL, 1962] n Preliminary step: Reduce all clauses in C o n Eliminate multiple occurrences of the same literal (leave only one). Generates a clause set C‘ Then apply the follwing rules non-deterministically to C‘ o o Tautology-Rule One-Literal-Rule Pure-Literal-Rule Splitting-Rule

![Pre-Resolution period: Davis-Putnam Procedure o Davis-Logemann-Loveland Rules [DLL, 1962] n n o Tautology-Rule: Delete Pre-Resolution period: Davis-Putnam Procedure o Davis-Logemann-Loveland Rules [DLL, 1962] n n o Tautology-Rule: Delete](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/d80d1a8816679a33eb61bc6a921d6931/image-34.jpg)

Pre-Resolution period: Davis-Putnam Procedure o Davis-Logemann-Loveland Rules [DLL, 1962] n n o Tautology-Rule: Delete all clauses in C‘ containing complementary literals One-Literal-Rule: If there is a clauses c = {l} with only one literal l, remove all clauses d from C‘ which contain l, and remove the dual literal l d from all other clauses Pure-Literal-Rule: Let D‘ µ C‘ with the following property: There exists a literal l appearing in all clauses of D‘, but ld does not appear in C‘. Then delete D‘ from C‘ Splitting-Rule: Let C‘ = {A 1, …, An, B 1, …, Bm} [ R such that R contains l nor ld, all Ai contain l but not ld and all Bj contain ld but not l. Let A‘i = Ai after deletion of l and let B‘j = Bj after deletion of ld. Then split C‘ into C‘ 1 = {A‘ 1, …, A‘n} [ R and C‘ 2={B‘ 1, …, B‘m} [ R Properties of the DLL procedure n n n The rules are essentially reductive (atoms are in each step deleted) The rules are correct (rules preserve satisfiability; in case of split only for one of the new introduced clauses sets The procedure generates sets that contain the empty clause for all cases (of the applied splits) iff C‘ is unsatisfiable (decision criteria: correctness and completeness, termination) Example: C = {P Ç Q, R Ç S, ¬R Ç S, R Ç ¬S, ¬R Ç ¬S, P Ç ¬Q Ç ¬P}

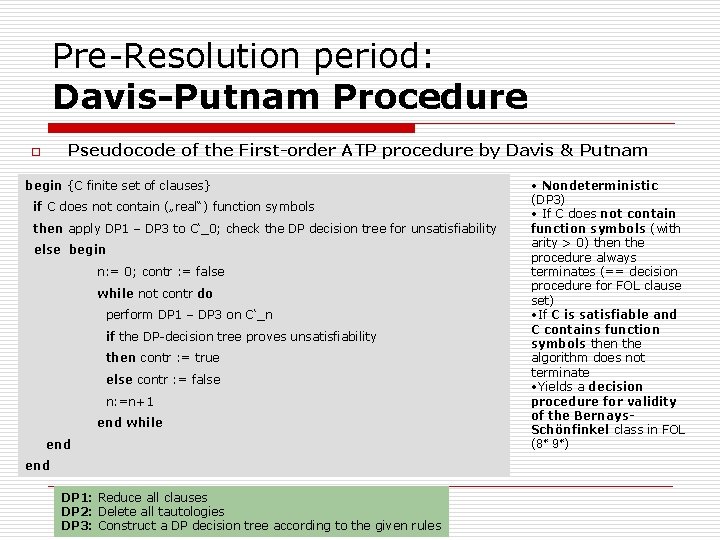

Pre-Resolution period: Davis-Putnam Procedure Pseudocode of the First-order ATP procedure by Davis & Putnam o begin {C finite set of clauses} if C does not contain („real“) function symbols then apply DP 1 – DP 3 to C‘_0; check the DP decision tree for unsatisfiability else begin n: = 0; contr : = false while not contr do perform DP 1 – DP 3 on C‘_n if the DP-decision tree proves unsatisfiability then contr : = true else contr : = false n: =n+1 end while end DP 1: Reduce all clauses DP 2: Delete all tautologies DP 3: Construct a DP decision tree according to the given rules • Nondeterministic (DP 3) • If C does not contain function symbols (with arity > 0) then the procedure always terminates (== decision procedure for FOL clause set) • If C is satisfiable and C contains function symbols then the algorithm does not terminate • Yields a decision procedure for validity of the Bernays. Schönfinkel class in FOL (8* 9*)

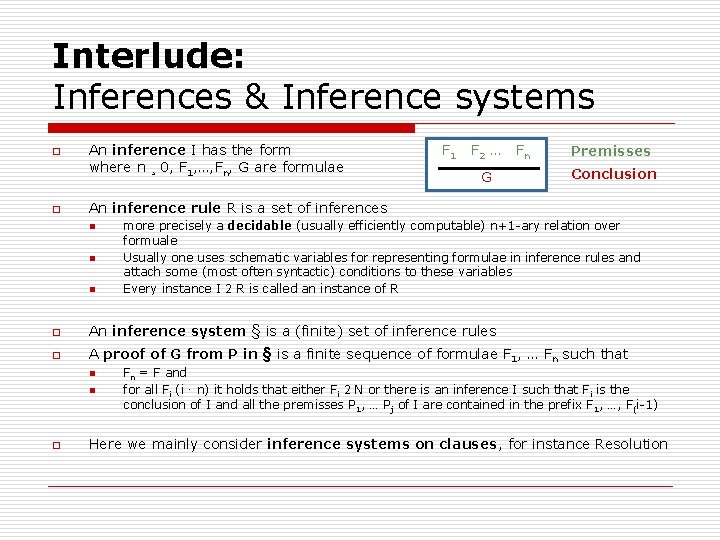

Interlude: Inferences & Inference systems o o An inference I has the form where n ¸ 0, F 1, …, Fn, G are formulae F 1 F 2 … G Fn Premisses Conclusion An inference rule R is a set of inferences n n n more precisely a decidable (usually efficiently computable) n+1 -ary relation over formuale Usually one uses schematic variables for representing formulae in inference rules and attach some (most often syntactic) conditions to these variables Every instance I 2 R is called an instance of R o An inference system § is a (finite) set of inference rules o A proof of G from P in § is a finite sequence of formulae F 1, … Fn such that n n o Fn = F and for all Fi (i · n) it holds that either F i 2 N or there is an inference I such that F i is the conclusion of I and all the premisses P 1, … Pj of I are contained in the prefix F 1, …, F(i-1) Here we mainly consider inference systems on clauses, for instance Resolution

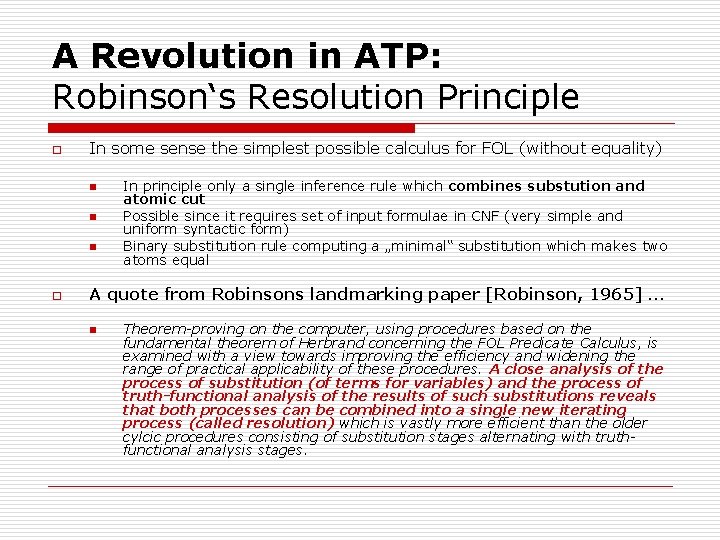

A Revolution in ATP: Robinson‘s Resolution Principle o In some sense the simplest possible calculus for FOL (without equality) n n n o In principle only a single inference rule which combines substution and atomic cut Possible since it requires set of input formulae in CNF (very simple and uniform syntactic form) Binary substitution rule computing a „minimal“ substitution which makes two atoms equal A quote from Robinsons landmarking paper [Robinson, 1965] … n Theorem-proving on the computer, using procedures based on the fundamental theorem of Herbrand concerning the FOL Predicate Calculus, is examined with a view towards improving the efficiency and widening the range of practical applicability of these procedures. A close analysis of the process of substitution (of terms for variables) and the process of truth-functional analysis of the results of such substitutions reveals that both processes can be combined into a single new iterating process (called resolution) which is vastly more efficient than the older cylcic procedures consisting of substitution stages alternating with truthfunctional analysis stages.

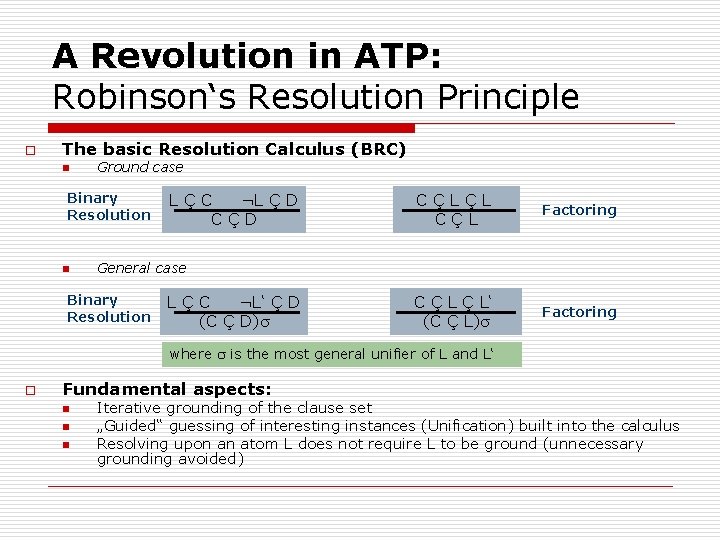

A Revolution in ATP: Robinson‘s Resolution Principle o The basic Resolution Calculus (BRC) n Ground case Binary Resolution n LÇC ¬L Ç D CÇLÇL CÇL Factoring C Ç L‘ (C Ç L) Factoring General case Binary Resolution LÇC ¬L‘ Ç D (C Ç D) where is the most general unifier of L and L‘ o Fundamental aspects: n n n Iterative grounding of the clause set „Guided“ guessing of interesting instances (Unification) built into the calculus Resolving upon an atom L does not require L to be ground (unnecessary grounding avoided)

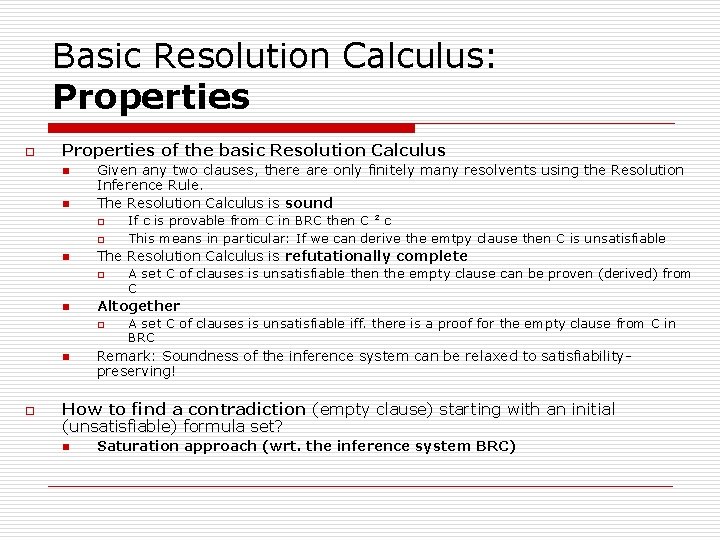

Basic Resolution Calculus: Properties of the basic Resolution Calculus n n Given any two clauses, there are only finitely many resolvents using the Resolution Inference Rule. The Resolution Calculus is sound o o n The Resolution Calculus is refutationally complete o n o A set C of clauses is unsatisfiable then the empty clause can be proven (derived) from C Altogether o n If c is provable from C in BRC then C ² c This means in particular: If we can derive the emtpy clause then C is unsatisfiable A set C of clauses is unsatisfiable iff. there is a proof for the empty clause from C in BRC Remark: Soundness of the inference system can be relaxed to satisfiabilitypreserving! How to find a contradiction (empty clause) starting with an initial (unsatisfiable) formula set? n Saturation approach (wrt. the inference system BRC)

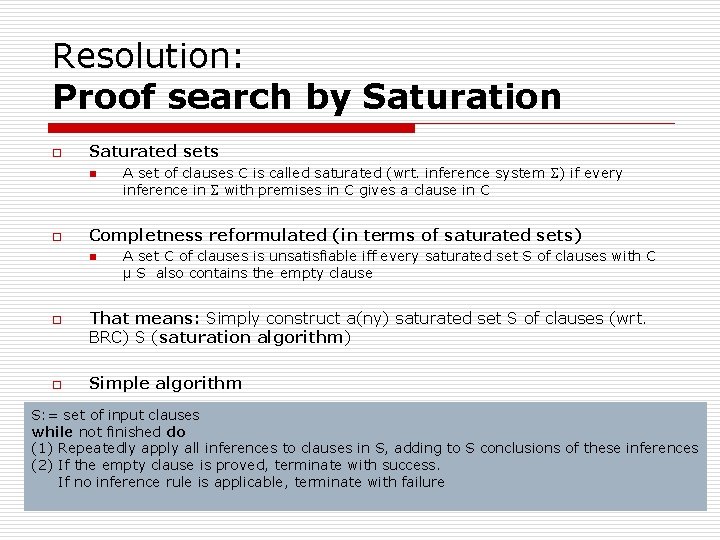

Resolution: Proof search by Saturation o Saturated sets n o Completness reformulated (in terms of saturated sets) n o o A set of clauses C is called saturated (wrt. inference system ) if every inference in with premises in C gives a clause in C A set C of clauses is unsatisfiable iff every saturated set S of clauses with C µ S also contains the empty clause That means: Simply construct a(ny) saturated set S of clauses (wrt. BRC) S (saturation algorithm) Simple algorithm S: = set of input clauses while not finished do (1) Repeatedly apply all inferences to clauses in S, adding to S conclusions of these inferences (2) If the empty clause is proved, terminate with success. If no inference rule is applicable, terminate with failure

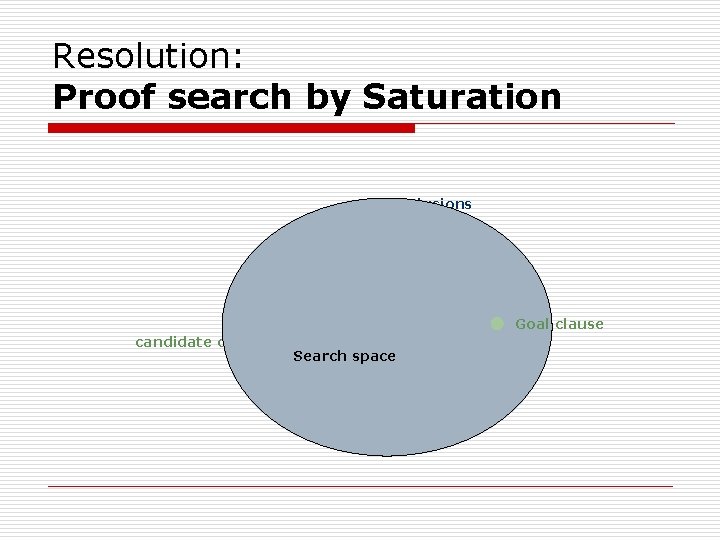

Resolution: Proof search by Saturation Conclusions candidate clause given clause Search space Goal clause

Resolution: Proof search by Saturation o Most likely scenario …. Search space

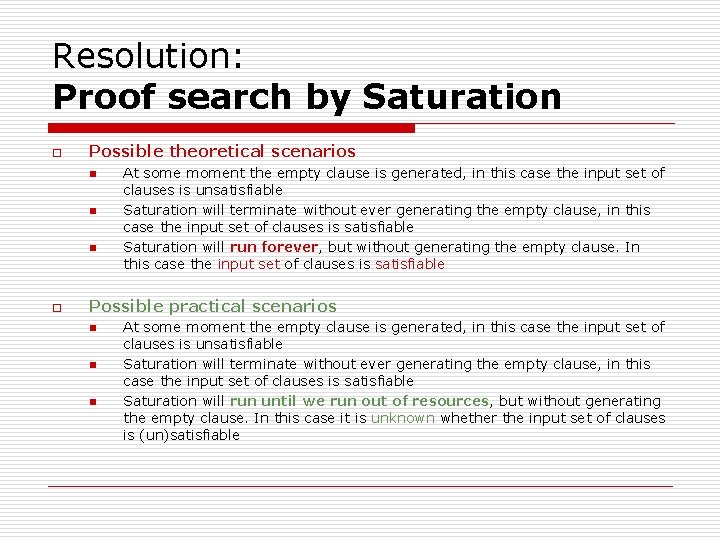

Resolution: Proof search by Saturation o Possible theoretical scenarios n n n o At some moment the empty clause is generated, in this case the input set of clauses is unsatisfiable Saturation will terminate without ever generating the empty clause, in this case the input set of clauses is satisfiable Saturation will run forever, but without generating the empty clause. In this case the input set of clauses is satisfiable Possible practical scenarios n n n At some moment the empty clause is generated, in this case the input set of clauses is unsatisfiable Saturation will terminate without ever generating the empty clause, in this case the input set of clauses is satisfiable Saturation will run until we run out of resources, but without generating the empty clause. In this case it is unknown whether the input set of clauses is (un)satisfiable

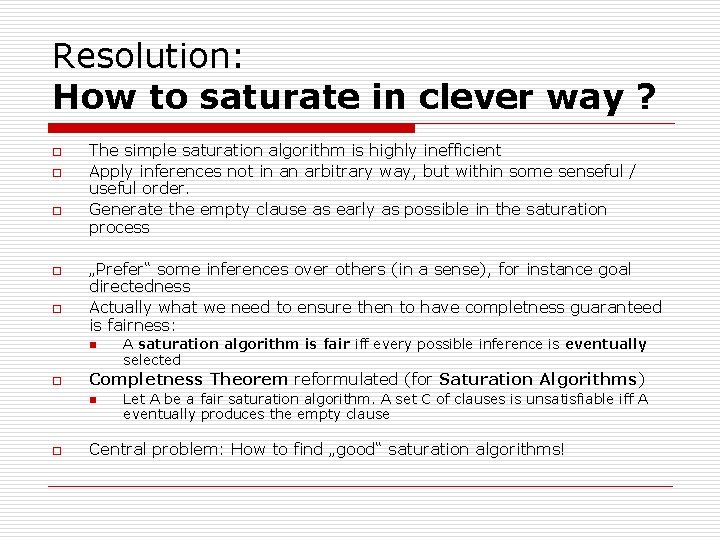

Resolution: How to saturate in clever way ? o o o The simple saturation algorithm is highly inefficient Apply inferences not in an arbitrary way, but within some senseful / useful order. Generate the empty clause as early as possible in the saturation process „Prefer“ some inferences over others (in a sense), for instance goal directedness Actually what we need to ensure then to have completness guaranteed is fairness: n o Completness Theorem reformulated (for Saturation Algorithms) n o A saturation algorithm is fair iff every possible inference is eventually selected Let A be a fair saturation algorithm. A set C of clauses is unsatisfiable iff A eventually produces the empty clause Central problem: How to find „good“ saturation algorithms!

How to guess suitable instances? Unification

Example: Basic Resolution Calculus

Enhancing Efficiency: Refinements of Resolution

Resolution Refinements: Hyperresolution

Resolution Refinements: Ordered Resolution

Enhancing Efficiency: Redundancy Criteria in Resolution

Part IV: Chain Resolution A Variant of Resolution for the Semantic Web n

Part IV: Demo assisted by a Resolution-based ATP System: VAMPIRE n

And there is a lot we have not talked about yet … o Different Calculi n o o o Decision Procedures Theory Reasoning, in particular equality ATP in other logics n n n o Tableaux Methods, Instance-based Methods, Inverse Method Modal, temporal logics, description logics Logics for non-monotonic reasoning Paraconsistent logics Reasoning tasks other than logical entailment / unsatisfiability n Query answering

References & further Reading …

- Slides: 54